Abstract

Purpose

A 2003 FDA advisory warned of increased hyperlipidemia and diabetes risk for patients taking second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). Following the advisory a professional society consensus statement provided treatment recommendations and stratified SGAs into high, intermediate, and low metabolic risk. We examine subsequent changes in incident and prevalent SGA use among individuals with severe mental illness.

Methods

Retrospective, observational study using Florida Medicaid’s claims from 2001–2006. We include non-Medicare eligible adults with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia who filled a SGA prescription. Among prevalent users we assess changes in overall and agent-specific use; discontinuations; interruptions; and therapeutic alternative use; among incident users, agent-specific use. Pre-advisory utilization was compared with utilization initially following the advisory and two subsequent periods.

Results

Among prevalent users, overall SGA use declined slightly and no increases in treatment interruptions or discontinuations were observed following the advisory and consensus statement publication. Compared with the pre-advisory period, in the months immediately following use of the highest metabolic-risk agent, olanzapine, decreased by 34% among prevalent users with bipolar disorder (adjusted risk ratio [aRR]=0.66; 95% confidence intervals [CI]=0.59–0.74) and 26% among prevalent users with schizophrenia (aRR=0.74, CI=0.72–0.76). A greater decline was estimated among incident users with bipolar disorder (aRR=0.37; CI=0.29–0.47) and schizophrenia (aRR=0.42; CI=0.35–0.51) during this period. During each subsequent post-advisory period, olanzapine use continued to decline while quetiapine, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole use increased.

Conclusions

The metabolic risk advisory and published consensus statement were associated with a selective reduction in olanzapine use without evidence of treatment disruptions among this population.

Keywords: Drug Utilization, FDA Advisory, Metabolic Risk, Second Generation Antipsychotics

INTRODUCTION

Second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are effective treatments for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, but have been associated with metabolic adverse effects that increase the risks for morbidity and mortality with long term use.1 In November 2003, after early safety problems emerged, the FDA issued a warning and requested that all SGA manufacturers notify health care providers of the increased risks for hyperlipidemia and diabetes among patients using SGAs.2 This advisory was followed by a February 2004 professional societies consensus statement3 recommending that prescribers screen patients for metabolic conditions, and consider metabolic risk when selecting an agent.

Clinicians may respond to the SGA safety advisory and consensus statement by more actively screening for metabolic changes in their patients, or changing their prescribing of SGAs by reducing overall rates of prescribing or substituting high metabolic risk agents (olanzapine and clozapine) with intermediate (risperidone and quetiapine) or lower (aripiprazole and ziprasidone) risk agents.3 Although prior studies suggests that metabolic screening rates have remained unchanged,4–10 one study8 identified shifts in new prescribing of some agents, notably decreases in new olanzapine use, and increases in aripiprazole use following the FDA advisory. However, assessing changes in new prescribing alone does not capture the advisory and consensus statement’s impact on clinical decision-making for patients with ongoing use.11

Clinicians may respond differently for new users than for existing users and we know little about how patterns of medication use have changed for patients with different medication histories. For example, clinicians’ treating current antipsychotic users may hesitate to switch patients who are stabilized on a higher metabolic risk drug; particularly patients with a history of poor response or non-compliance. In essence, the tradeoff between symptom reduction and weight gain may differ between new versus ongoing antipsychotic users.

Since continuous pharmacotherapy is critical for patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, and anecdotal evidence suggests that patients may be at increased risk for discontinuations or treatment interruptions following the release of drug risk communications,12 understanding changes in SGA utilization among prevalent users is important. We sought to identify patient-level changes in incident and prevalent SGA use among Medicaid enrollees with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. We focus on changes in overall SGA use, treatment discontinuations, interruptions, and use of therapeutic alternatives among prevalent SGA users. To determine how responses differ among incident and prevalent SGA users, we assess agent-specific utilization among each group following the FDA advisory and consensus statement publication.

METHODS

Data Source

This study received an exemption from Harvard Medical School’s Institutional Review Board. We used de-identified administrative claims from the Florida Medicaid program from July 2000–December 2006.

Study Time Periods

Although the primary focus is on comparing SGA use prior to the advisory with use immediately following the advisory, we measure SGA use during 6 distinct periods based on the timing of relevant publications, media reports, FDA regulatory activities, and Florida Medicaid policy changes (eTable 1). The pre-advisory period consisted of two segments. The first, January 2001–January 2003, was a period when metabolic risk information was largely unknown. The second, February 2003–November 2003, captured responses to early media reports and peer-reviewed publications identifying metabolic concerns for SGAs.13–15 The advisory period began in December 2003 following the FDA advisory, included the February 2004 professional societies’ consensus statement, and ended in August 2004 after all manufacturers sent FDA-requested “Dear Health Care Provider” letters.2, 16, 17 The post-advisory period consisted of three segments. The first was an initial post-advisory period (September 2004–March 2005) during which no additional changes occurred in the antipsychotic marketplace. The second period, from April 2005–September 2005, contained several events that might have impacted SGA use including a class-wide black-box warning (April, 2005),17 the publication of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) results (September, 2005)18 and the temporary implementation of a preferred drug list in Florida Medicaid that re-categorized olanzapine as a non-preferred agent and required that physicians switch patients from olanzapine to an alternative agent (July, 2005).19 Finally, the third post-advisory period from October 2005–December 2006 assessed SGA use following these events.

Cohort Identification

We included adults aged 18–64 who were not dually-enrolled in Medicare or a managed care plan during the 180 days prior to their first SGA fill. Enrollees were classified as having schizophrenia if they had at least two claims (inpatient or outpatient, on separate service dates) for schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 295.x) from July 2000–December 2006.20–22 Enrollees were classified as having bipolar disorder if they did not have schizophrenia and had at least two claims for a bipolar spectrum disorder (ICD-9-CM 296.0, 296.1, 296.4–296.8).23, 24

We required enrollees to have at least one SGA prescription fill between January 1,2001 and December 31,2006. The date of the first SGA fill during this period was considered the enrollee’s index prescription-fill date. SGAs included: olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole. Clozapine was excluded due to its infrequent use (<1% of SGA fills). To assess prior diagnoses we required enrollees to have continuous Medicaid enrollment for 6 months before their index SGA date. We treated the period between July 1,2000–December 31,2000 as a pre-screening window to allow all individuals to have at least 180 days of observable time before their index prescription date.

Prevalent Users

Since we were interested in estimating how SGA use changed among current users at the time of the advisory, we required that the index SGA prescription for prevalent users be filled prior to the FDA advisory period (December 2003). We defined enrollees with any SGA fill in the 180 days prior to their index fill date as prevalent users. We required prevalent users to have at least 6 months of continuous enrollment in Medicaid following their index prescription date.

Incident Users

We defined incident users as enrollees with no SGA fills during the 180 day period prior to their index prescription fill date.25 No follow-up was required for incident users as the focus was on initial medication selection.

Outcome Measures

Among prevalent medication users, we assessed the likelihood of receiving any SGA, alternative pharmacotherapy use, and the occurrence of SGA discontinuations or interruptions. We assessed monthly SGA use for each enrollee. Individuals with at least 15 days of available therapy were identified as SGA users for the month. Available therapy was calculated using the enrollees’ medication fill date and days of supply (adjusted for oversupply).26 Alternative pharmacotherapy was defined as first-generation antipsychotics for enrollees with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and use of lithium or mood stabilizing anticonvulsants that are either expert guideline approved27–30 or FDA indicated for bipolar disorder (lamotrigine, carbamazepine, or valproate). Among monthly SGA users we defined discontinuations as gaps of 6 months or more following the last month of available SGA therapy. We defined interruptions as gaps of one to five months between SGA fills.

Next, for prevalent and incident users, we assessed the likelihood of receiving a specific SGA among enrollees filling any antipsychotic prescription. For each model, a dichotomous variable was created where the drug of interest was compared with all other SGAs. Separate models were estimated for olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole. Because of aripiprazole’s late market entry (November, 2002), we estimated the probability of its use, but not relative changes from the pre-advisory period.

Olanzapine use was the primary focus given its identification as the highest metabolic risk SGA. Because of this, in secondary analyses we also assessed the likelihood of receiving each SGA among prior olanzapine users, and enrollees with prior metabolic conditions.

Covariates

Covariates, measured in the 6 months prior to the enrollee’s index prescription-fill date, included age, race, Medicaid eligibility category, inpatient mental health services use, and receipt of outpatient care from a psychiatrist. Additionally, we controlled for prior diagnoses of metabolic-related conditions31 since these conditions may influence prescribing decisions following the advisory. We also controlled for co-morbid mental health conditions that could impact SGA selection, complicate the treatment of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, or indicate a specific treatment32 (eTable 2).

Statistical Analysis

We estimated monthly changes in SGA use among prevalent users following the advisory using a modified Poisson regression model using the sandwich variance estimator to account for the repeated observations among enrollees over time..33–35 We present adjusted risks, risk ratios, and 95% confidence intervals. Separate models were estimated for enrollees with bipolar disorder and those with schizophrenia. Because we focus on assessing changes associated with the FDA’s metabolic risk advisory and the subsequent consensus statement recommendations, comparisons are between the pre-advisory and initial post-advisory periods unless otherwise noted.

Sensitivity Analyses

Because our results may be sensitive to the timeframes selected or changes in agent-specific use, four sensitivity analyses were conducted. The first used a previously specified pre-post-advisory period;7,8,10 the second excluded aripiprazole because its market entry might have biased estimates of changes in SGA use; the third explored whether increases in off-label low-dose quetiapine use (e.g., for insomnia or anxiety)36 influenced our results. Finally, we restricted our sample to enrollees who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid during the entire study period to determine whether our results were influenced by individuals exiting the Medicaid system over time.

RESULTS

There were 22,998 enrollees in our final sample, including 9,437 prevalent and 13,561 incident users. Among prevalent SGA users, 1,058 (11%) had bipolar disorder, and 8,379 (89%) schizophrenia (Table 1). Although the presence of metabolic-related conditions was similar between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia enrollees, there were considerable differences between these groups on most covariates. For example, as compared with prevalent users with schizophrenia, those with bipolar disorder were less likely to be male (30% versus 46%), black (7% versus 21%), or qualify for Medicaid through Supplemental Security Income (80% versus 92%). Incident SGA users were similar to prevalent users, although the proportion of incident SGA users with bipolar disorder was higher (31% versus 11%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Prevalent and Incident Second Generation Antipsychotic Users with Severe Mental Illness

| Prevalent Users N = 9,437 |

Incident Users N = 13,561 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bipolar Disorder | Schizophrenia | Bipolar Disorder | Schizophrenia | |||||

| N = 1,058 | N = 8,379 | N = 4,239 | N = 9,322 | |||||

| Sample Characteristics | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18 – 29 Years | 210 | 19.8 | 1,319 | 15.7 | 1,020 | 24.1 | 1,734 | 18.6 |

| 30 – 39 Years | 262 | 24.8 | 1,794 | 21.4 | 1,139 | 26.9 | 1,910 | 20.5 |

| 40 – 49 Years | 319 | 30.1 | 2,704 | 32.3 | 1,243 | 29.3 | 2,858 | 30.7 |

| 50 – 59 Years | 205 | 19.4 | 1,947 | 23.2 | 687 | 16.2 | 2,127 | 22.8 |

| 60 – 64 Years | 62 | 5.9 | 615 | 7.3 | 150 | 3.5 | 693 | 7.4 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 323 | 30.5 | 3,861 | 46.1 | 1,046 | 24.7 | 4,355 | 46.7 |

| Female | 735 | 69.5 | 4,518 | 53.9 | 3,193 | 75.3 | 4,967 | 53.3 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 682 | 64.5 | 3,736 | 44.6 | 2,941 | 69.4 | 3,532 | 37.9 |

| Black | 72 | 6.8 | 1,782 | 21.3 | 334 | 7.9 | 2,518 | 27.0 |

| Hispanic | 128 | 12.1 | 1,355 | 16.2 | 529 | 12.5 | 1,851 | 19.9 |

| Other | 176 | 16.6 | 1,506 | 18.0 | 435 | 10.3 | 1,421 | 15.2 |

| Medicaid Eligibility Category | ||||||||

| SSI | 851 | 80.4 | 7,750 | 92.5 | 2,733 | 64.5 | 8,038 | 86.2 |

| Other | 207 | 19.6 | 629 | 7.5 | 1,506 | 35.5 | 1,284 | 13.8 |

| Received Care from a Psychiatrist | ||||||||

| Yes | 782 | 73.9 | 6,924 | 82.6 | 2,431 | 57.3 | 6,397 | 68.6 |

| Disease Severity | ||||||||

| Any Inpatient Mental Health Visits | 173 | 16.3 | 1,930 | 23.0 | 1,068 | 25.2 | 2,717 | 29.1 |

| Prior Mental Health Diagnoses | ||||||||

| Alcohol and/or Substance Abuse | 77 | 7.3 | 588 | 7.0 | 586 | 13.8 | 996 | 10.7 |

| Diagnoses that Modify Treatment | ||||||||

| Epilepsy | 82 | 7.7 | 698 | 8.3 | 288 | 6.8 | 640 | 6.9 |

| Dementia | 16 | 1.5 | 122 | 1.5 | 47 | 1.1 | 157 | 1.7 |

| Complicating Conditions | 267 | 25.2 | 1,785 | 21.3 | 1,204 | 28.4 | 1,873 | 20.1 |

| Metabolic-Related Conditions | ||||||||

| Diabetes | 103 | 9.7 | 1,059 | 12.6 | 452 | 10.7 | 1,231 | 13.2 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 99 | 9.4 | 934 | 11.1 | 565 | 13.3 | 1,292 | 13.9 |

| Hypertension | 168 | 15.9 | 1,714 | 20.5 | 1,185 | 27.9 | 2,890 | 31.0 |

| Heart Disease | 67 | 6.3 | 648 | 7.7 | 245 | 5.8 | 706 | 7.6 |

| Obesity | 29 | 2.7 | 261 | 3.1 | 90 | 2.1 | 224 | 2.4 |

| Index Prescription Fill Period | ||||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01 – Jan 03) | 1,058 | 100 | 8,379 | 100 | 1,791 | 42.2 | 5,228 | 56.1 |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03 – Nov 03) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 833 | 19.7 | 1,718 | 18.4 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03 – Aug 04) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 613 | 14.5 | 1,069 | 11.5 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04 – Mar 05) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 437 | 10.3 | 621 | 6.7 |

| PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warninga (April 05 – Sept 05) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 349 | 8.2 | 411 | 4.4 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE / Dementia Warning (Oct 05 – Dec 06) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 216 | 5.1 | 275 | 2.9 |

PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning = Period including the Medicaid Preferred-Drug List policy change, publication of the CATIE trial results, and the FDA’s black box warning for the risk of mortality among elderly patients with dementia.

Changes in prevalent SGA use

Overall SGA use decreased slightly among all enrollees following the FDA advisory (Table 2, eTable 3). As compared with the pre-advisory period, in the initial post-advisory period there was a 7% decrease (RR=0.93, CI=0.89–0.97) in SGA use among enrollees with bipolar disorder and a 2% decrease (RR=0.98, CI=0.97–0.99) among enrollees with schizophrenia. Although there were decreases in SGA discontinuations and interruptions, these events were uncommon among both groups, ranging from 2–3% from the pre-advisory through the initial post-advisory period.

Table 2.

Impact of FDA Warning on Prevalent Second Generation Antipsychotic Users, by Diagnosis

| Bipolar Disorder | Schizophrenia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modeled Outcomea | Risk | Risk Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

Risk | Risk Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Second Generation Antipsychotic Use | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01 – Jan 03) | .66 | REF | REF | .70 | REF | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03 – Nov 03) | .64 | .96 | .93–.99 | .70 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03 – Aug 04) | .62 | .94 | .91–.98 | .69 | .99 | .99–1.00 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04 – Mar 05) | .61 | .93 | .89–.97 | .68 | .98 | .97–.99 |

| PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning (April 05 – Sept 05) | .61 | .92 | .88–.96 | .67 | .96 | .95–.97 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE / Dementia Warning (Oct 05 – Dec 06) | .52 | .78 | .74–.82 | .60 | .87 | .85–.88 |

| Alternative Medication Useb | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01 – Jan 03) | .22 | 1.00 | REF | .07 | 1.00 | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03 – Nov 03) | .31 | 1.38 | 1.31–1.45 | .07 | 1.02 | .99–1.06 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03 – Aug 04) | .31 | 1.38 | 1.29–1.47 | .07 | 1.02 | .98–1.07 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04 – Mar 05) | .32 | 1.44 | 1.33–1.55 | .07 | 1.00 | .95–1.05 |

| PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning (April 05 – Sept 05) | .31 | 1.39 | 1.28–1.51 | .07 | 1.00 | .95–1.06 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE / Dementia Warning (Oct 05 – Dec 06) | .30 | 1.33 | 1.22–1.46 | .07 | .96 | .91–1.02 |

| Second Generation Antipsychotic Discontinuationsc | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01 – Jan 03) | .03 | 1.00 | REF | .03 | 1.00 | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03 – Nov 03) | .02 | .75 | .60–.94 | .02 | .75 | .69–.82 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03 – Aug 04) | .02 | .74 | .58–.95 | .02 | .79 | .71–.87 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04 – Mar 05) | .02 | .73 | .55–.98 | .02 | .80 | .72–.90 |

| PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning (April 05 – Sept 05) | .02 | .88 | .66–1.18 | .03 | .96 | .86–1.08 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE / Dementia Warning (Oct 05 – Dec 06) | .04 | 1.37 | 1.11–1.68 | .04 | 1.46 | 1.35–1.58 |

| Second Generation Antipsychotic Interruptionsd | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01 – Jan 03) | .09 | 1.00 | REF | .08 | 1.00 | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03 – Nov 03) | .08 | .81 | .74–.90 | .07 | .82 | .80–.85 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03 – Aug 04) | .08 | .80 | .72–.89 | .07 | .82 | .79–.85 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04 – Mar 05) | .08 | .82 | .72–.93 | .07 | .82 | .78–.85 |

| PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning (April 05 – Sept 05) | .07 | .80 | .70–.91 | .08 | .90 | .86–.93 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE / Dementia Warning (Oct 05 – Dec 06) | .07 | .77 | .68–.86 | .07 | .82 | .80–.85 |

Generalized estimating equations were used to account for the repeated measures on each subject. We estimated each model using PROC GENMOD (SAS, 9.1) with a Poisson distribution, log link. The correlation structure was unspecified. Control variables included sex, age, race, Medicaid eligibility status, and the presence of the following during the 6 months prior to the index prescription date: receipt of care from a psychiatrist, inpatient mental health treatment, dementia, alcohol or substance abuse, epilepsy, complicating conditions, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, heart disease, or obesity. PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning = Period including the Medicaid Preferred-Drug List policy change, publication of the CATIE trial results, and the FDA’s black box warning for the risk of mortality among elderly patients with dementia.

Medication alternatives included first generation antipsychotics (for enrollees with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder), and lithium, lamotrigine, carbamazepine, or valproate (for enrollees with bipolar disorder).

Discontinuations were defined as 6 or more months of no second generation antipsychotic use following a month of second generation antipsychotic use.

Interruptions were defined as a gap in second generation antipsychotic fills of 1 to 5 months with second generationantipsychotic use before and after the gap.

Among enrollees with bipolar disorder, 22% received an alternative pharmacotherapy during the pre-advisory period, and that proportion increased by 44% during the initial post-advisory period (RR=1.44, CI=1.33–1.55).

Agent-specific use – prevalent users

Olanzapine was the most prevalently used SGA during the pre-advisory period, representing 41% of SGA fills among enrollees with bipolar disorder and 43% among enrollees with schizophrenia (Table 3). From the pre-advisory to the initial post-advisory period, olanzapine use decreased by 34% among enrollees with bipolar disorder (RR=0.66, CI=0.59–0.74) and 26% among enrollees with schizophrenia (RR=0.74, CI=0.72–0.76). By the most recent study period, olanzapine represented 16–17% of all SGA fills.

Table 3.

Impact of the FDA Warning on Agent-Specific Use among Prevalent Antipsychotic Users, by Diagnosis

| Bipolar Disorder | Schizophrenia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agent-Specific Utilizationa | Risk | Risk Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

Risk | Risk Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

| Olanzapine Useb | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01–Jan 03) | .41 | 1.00 | REF | .43 | 1.00 | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03–Nov 03) | .37 | .90 | .84–.95 | .42 | .96 | .95–.98 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03–Aug 04) | .33 | .80 | .74–.87 | .38 | .88 | .86–.90 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04–Mar 05) | .27 | .66 | .59–.74 | .32 | .74 | .72–.76 |

| PDL/CATIE/Dementia Warning (April 05–Sept 05) | .22 | .52 | .46–.60 | .23 | .54 | .52–.56 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE/Dementia Warning (Oct 05–Dec 06) | .17 | .41 | .34–.50 | .16 | .36 | .34–.38 |

| Quetiapine Use | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01–Jan 03) | .14 | 1.00 | REF | .16 | 1.00 | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03–Nov 03) | .17 | 1.15 | 1.06–1.26 | .20 | 1.20 | 1.16–1.25 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03–Aug 04) | .19 | 1.28 | 1.15–1.43 | .21 | 1.28 | 1.23–1.34 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04–Mar 05) | .21 | 1.47 | 1.30–1.66 | .23 | 1.41 | 1.34–1.47 |

| PDL/CATIE/Dementia Warning (April 05–Sept 05) | .24 | 1.63 | 1.44–1.87 | .27 | 1.65 | 1.58–1.73 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE/Dementia Warning (Oct 05–Dec 06) | .24 | 1.64 | 1.44–1.87 | .30 | 1.83 | 1.74–1.92 |

| Risperidone Use | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01–Jan 03) | .45 | 1.00 | REF | .42 | 1.00 | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03–Nov 03) | .44 | .98 | .92–1.04 | .38 | .91 | .89–.92 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03–Aug 04) | .41 | .90 | .82–.98 | .37 | .89 | .86–.91 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04–Mar 05) | .41 | .89 | .81–.99 | .39 | .92 | .89–.95 |

| PDL/CATIE/Dementia Warning (April 05–Sept 05) | .42 | .92 | .83–1.03 | .40 | .95 | .92–.98 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE/Dementia Warning (Oct 05–Dec 06) | .42 | .92 | .82–1.04 | .41 | .97 | .94–1.00 |

| Ziprasidone Use | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01–Jan 03) | .02 | 1.00 | REF | .05 | 1.00 | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03–Nov 03) | .04 | 1.65 | 1.31–2.08 | .10 | 1.85 | 1.71–1.99 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03–Aug 04) | .04 | 2.00 | 1.52–2.68 | .11 | 2.06 | 1.88–2.25 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04–Mar 05) | .05 | 2.31 | 1.73–3.26 | .13 | 2.46 | 2.24–2.71 |

| PDL/CATIE/Dementia Warning (April 05–Sept 05) | .06 | 2.67 | 2.03–3.71 | .15 | 2.76 | 2.51–3.04 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE/Dementia Warning (Oct 05–Dec 06) | .06 | 2.58 | 1.88–3.58 | .15 | 2.76 | 2.50–3.06 |

| Aripiprazole Usec | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01–Jan 03) | .00 | -- | -- | .00 | -- | -- |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03–Nov 03) | .03 | -- | -- | .08 | -- | -- |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03–Aug 04) | .05 | -- | -- | .12 | -- | -- |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04–Mar 05) | .07 | -- | -- | .15 | -- | -- |

| PDL/CATIE/Dementia Warning (April 05–Sept 05) | .09 | -- | -- | .17 | -- | -- |

| Post-PDL/CATIE/Dementia Warning (Oct 05–Dec 06) | .12 | -- | -- | .20 | -- | -- |

Models were estimated using PROC GENMOD (SAS, 9.1) with a Poisson distribution and log link. Control variables included sex, age, race, Medicaid eligibility status, and the presence of the following during the 6 months prior to the index prescription date: receipt of care from a psychiatrist, inpatient mental health treatment, dementia, alcohol or substance abuse, epilepsy, complicating conditions, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, heart disease, or obesity. PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning = Period including the Medicaid Preferred-Drug List policy change, publication of the CATIE trial results, and the FDA’s black box warning for the risk of mortality among elderly patients with dementia.

High metabolic risk agent = Olanzapine. All other agents classified as lower metabolic risk agents.

Risk ratios are not provided for aripiprazole since it was introduced late in the pre-advisory period.

From the pre-advisory to initial post-advisory period there was a small, but statistically significant decrease in risperidone use among prevalent users with bipolar disorder (RR=0.89, CI=0.81–0.99) and schizophrenia (RR=0.92, CI=0.89–0.95). During the same time period quetiapine use increased by 47% (RR=1.47, CI=1.30–1.66) among enrollees with bipolar disorder, and 41% (RR=1.41, CI=1.34–1.47) among enrollees with schizophrenia. Further, use of this agent continued to increase through the end of the study period.

Use among prior olanzapine users

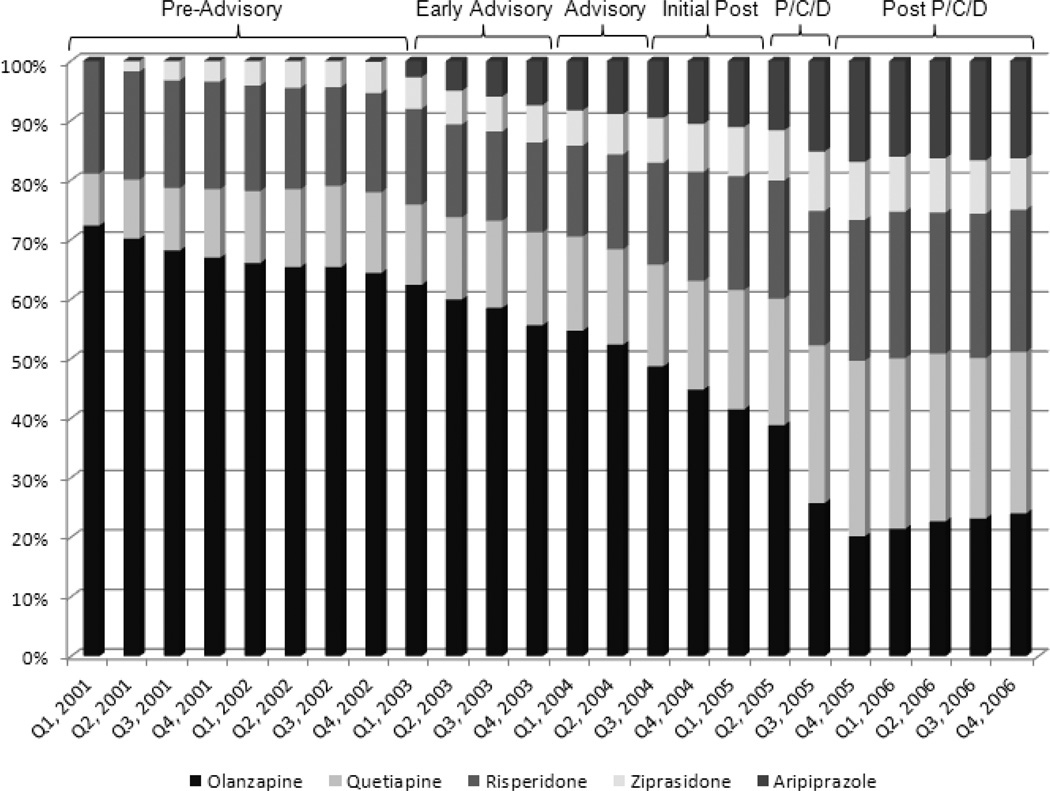

Among prior olanzapine users, subsequent olanzapine use declined by 29% from the pre-advisory to the initial post-advisory period (RR=0.71, CI=0.69–0.73). Over the study period use continued to decline, dropping from 74% in the pre-advisory period to 27% by the end of the study period (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Atypical Antipsychotic Market Share among Prior Olanzapine Users.

P/C/D = Period including the Medicaid Preferred-Drug List policy change, publication of the CATIE trial results, and the FDA’s black box warning for the risk of mortality among elderly patients with dementia.

Use among patients with prior metabolic conditions

By the initial post-advisory period, olanzapine use had decreased by 31% among enrollees with prior metabolic conditions (RR=0.69, CI=0.66–0.73), and by 24% among enrollees without these conditions (RR=.76, CI=.74–.79). By the most recent period the risk of olanzapine use was 13% among those with and 17% among those without prior metabolic conditions.

Agent-specific use – incident users

Incident SGA prescribing changed rapidly, with a steady decline in olanzapine use over the study period (Table 4). As compared with the pre-advisory period, by the end of the initial post-advisory period olanzapine use decreased by 63% among incident users with bipolar disorder and 58% among those with schizophrenia. Incident use patterns for each of the other SGAs largely mirrored use among the prevalent users, although quetiapine captured a larger share of incident prescriptions by the end of the study period (38% for bipolar disorder, 33% for schizophrenia).

Table 4.

Impact of the FDA Warning on Incident Second Generation Antipsychotic Drug Use, by Diagnosis

| Bipolar Disorder | Schizophrenia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agent-Specific Utilizationa | Risk | Risk Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

Risk | Risk Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

| Olanzapineb | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01–Jan 03) | .66 | 1.00 | REF | .48 | 1.00 | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03–Nov 03) | .59 | .88 | .78–1.00 | .41 | .87 | .79–.94 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03–Aug 04) | .44 | .66 | .56–.77 | .30 | .63 | .56–.71 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04–Mar 05) | .24 | .37 | .29–.47 | .20 | .42 | .35–.51 |

| PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning (April 05–Sept 05) | .12 | .17 | .12–.25 | .10 | .22 | .16–.30 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE / Dementia Warning (Oct 05–Dec 06) | .12 | .19 | .12–.29 | .08 | .17 | .11–.27 |

| Quetiapine | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01–Jan 03) | .18 | 1.00 | REF | .16 | 1.00 | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03–Nov 03) | .24 | 1.38 | 1.19–1.60 | .20 | 1.21 | 1.07–1.36 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03–Aug 04) | .26 | 1.49 | 1.27–1.75 | .23 | 1.37 | 1.19–1.57 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04–Mar 05) | .34 | 1.91 | 1.62–2.26 | .31 | 1.86 | 1.59–2.17 |

| PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning (April 05–Sept 05) | .37 | 2.11 | 1.77–2.52 | .31 | 1.86 | 1.55–2.23 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE / Dementia Warning (Oct 05–Dec 06) | .38 | 2.13 | 1.73–2.63 | .33 | 1.98 | 1.60–2.46 |

| Risperidone | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01–Jan 03) | .06 | 1.00 | REF | .33 | 1.00 | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03–Nov 03) | .04 | .72 | .60–.86 | .25 | .77 | .70–.85 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03–Aug 04) | .04 | .70 | .57–.86 | .27 | .83 | .74–.94 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04–Mar 05) | .04 | .70 | .55–.89 | .26 | .81 | .69–.94 |

| PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning (April 05–Sept 05) | .04 | .64 | .49–.85 | .31 | .94 | .79–1.11 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE / Dementia Warning (Oct 05–Dec 06) | .05 | .74 | .54–1.02 | .29 | .88 | .71–1.09 |

| Ziprasidone | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01–Jan 03) | .01 | 1.00 | REF | .08 | 1.00 | REF |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03–Nov 03) | .01 | .79 | .55–1.14 | .09 | 1.12 | .91–1.37 |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03–Aug 04) | .02 | 1.35 | .96–1.91 | .12 | 1.48 | 1.19–1.85 |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04–Mar 05) | .02 | 1.59 | 1.11–2.28 | .12 | 1.56 | 1.19–2.05 |

| PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning (April 05–Sept 05) | .03 | 1.98 | 1.36–2.89 | .14 | 1.80 | 1.33–2.44 |

| Post-PDL/CATIE / Dementia Warning (Oct 05–Dec 06) | .01 | .59 | .27–1.28 | .16 | 1.98 | 1.39–2.82 |

| Aripiprazolec | ||||||

| Pre-Advisory Period (Jan 01–Jan 03) | .00 | -- | -- | .00 | -- | -- |

| Early- Advisory (Feb 03–Nov 03) | .01 | -- | -- | .12 | -- | -- |

| Advisory Period (Dec 03–Aug 04) | .02 | -- | -- | .13 | -- | -- |

| Initial Post-Advisory (Sept 04–Mar 05) | .02 | -- | -- | .16 | -- | -- |

| PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning (April 05–Sept 05) | .02 | -- | -- | .16 | -- | -- |

| Post-PDL/CATIE / Dementia Warning (Oct 05–Dec 06) | .03 | -- | -- | .18 | -- | -- |

Models were estimated using PROC GENMOD (SAS, 9.1) with a Poisson distribution and log link. Control variables included sex, age, race, Medicaid eligibility status, and the presence of the following during the 6 months prior to the index prescription date: receipt of care from a psychiatrist, inpatient mental health treatment, dementia, alcohol or substance abuse, epilepsy, complicating conditions, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, heart disease, or obesity. PDL / CATIE / Dementia Warning = Period including the Medicaid Preferred-Drug List policy change, publication of the CATIE trial results, and the FDA’s black box warning for the risk of mortality among elderly patients with dementia.

High metabolic risk agent = Olanzapine. All other agents classified as lower metabolic risk agents.

Risk ratios are not provided for aripiprazole since it was introduced late in the pre-advisory period.

Sensitivity Analyses

We assessed an alternative definition of the advisory period using previously defined timeframes and found no meaningful differences in outcomes. Additionally, we estimated separate models in which we excluded aripiprazole and found no meaningful differences in outcomes between analyses.

We next assessed whether increases in quetiapine use could be explained by off-label low-dose use36 and found that low-dose quetiapine prescribing actually declined and average daily dose increased over the study period.

After restricting to those continuously-enrolled throughout the study period, approximately 67% of SGA users before the advisory were observable through the entire study period and 76% were observable through the initial post-advisory period. Results for olanzapine use were virtually identical, and although there were modest differences when examining secondary outcomes the substantive interpretation of our findings remained unchanged.

DISCUSSION

Among Florida Medicaid recipients, there were small decreases in overall SGA use after the FDA advisory and consensus statement publication. However, there were significant and sustained decreases in olanzapine use among both incident and prevalent SGA users. Our results are consistent with two prior evaluations assessing SGA prescribing, specifically regarding shifts in olanzapine use.8, 37 However, the current study expands upon prior efforts by evaluating the advisory and consensus statement’s impact on both specific agent selection and several important and potentially unintended outcomes including changes in overall SGA use, use of therapeutic substitutes, and treatment interruptions or discontinuations.

While anecdotal evidence suggests that patients may be at increased risk for discontinuations or treatment interruptions following the release of drug risk communications,12 we did not observe this in our sample. Instead, there were decreases in discontinuations and treatment interruptions through the initial post-advisory period. This is encouraging considering the importance of continuity of care among patients with severe mental illness.

Previous studies of the FDA advisory’s impact on metabolic risk have left the impression that the advisory was largely ineffective due to the low adoption of metabolic screening recommendations.16, 18, 19, 38 Coupled with our finding of little change in overall SGA use, one might conclude that the advisory had little effect on providers’ treatment decisions. However, there were substantial changes in drug utilization with major shifts away from olanzapine to drugs with lower known risk. Given the recent focus on preventing weight gain and metabolic syndrome in patients through selecting lower metabolic risk agents,39 these results are promising.

While the importance of screening and monitoring patients for metabolic adverse effects should not be minimized, neither should the importance of agent selection. Patients taking SGAs or other agents requiring laboratory monitoring or clinical follow-up may face important barriers to monitoring, including a fragmented medical system,40 provider discomfort or lack of knowledge about the patient’s general medical conditions (for mental health clinicians)41 or mental health conditions (for primary care providers),42 and problems resulting from the patient’s mental illness (e.g., amotivation, cognitive limitations, poverty).40 These barriers may have led physicians to adopt a general policy of avoidance of higher metabolic risk agents. In fact, significant declines in olanzapine use occurred among enrollees with and without prior metabolic conditions, suggesting that high-risk agent use decreased among all patients, rather than among higher-risk patients alone. This explanation is supported by a recent study suggesting that selection of a lower-risk SGA was not consistently associated with abnormal laboratory values.7

Although olanzapine use rapidly decreased following the FDA’s advisory, these decreases were offset by significant increases in quetiapine use. Recently there has been concern that quetiapine may be associated with a higher metabolic risk than originally proposed in the consensus statement.43, 44 Given the high proportion of incident quetiapine use in our sample, this relationship should be further clarified.

Following the initial post-advisory period, several important market impacts occurred for SGAs. For example, from April–September 2005 the CATIE trial results were published (reporting olanzapine’s efficacy and association with weight gain and metabolic problems), the FDA added a black-box warning to SGAs regarding an increased risk for elderly patients with dementia, and Florida Medicaid temporarily shifted olanzapine onto a non-preferred drug list. These factors were associated with additional decreases in olanzapine use. By the end of the study period olanzapine use had decreased by 59% among prevalent users with bipolar disorder, and 64% among prevalent users with schizophrenia, while incident olanzapine prescribing declined, 81% and 83%, respectively.

Limitations include using Medicaid claims from a single state, which may limit generalizability if SGA users systematically differ across states. In addition, one prior study showed a large effect of Florida’s 2005 policy change on olanzapine prescribing.45 Although our primary focus is on assessing changes prior to this policy change, estimates from later study periods may be lower than in Medicaid programs without similar policies. Next, while we observed changes in SGA selection following the FDA advisory and consensus statement, the effect cannot be separated from other policy and market impacts. Changes in pharmaceutical firms’ promotional strategies, Medicaid policies, and publication of new safety and effectiveness information all play a part in increasing or decreasing overall utilization of a pharmaceutical product. Although we control for known Medicaid policy changes and timing of major publications, press releases, and additional advisories, other unobserved factors may have influenced our results.

Overall, there were significant shifts in SGA use among Medicaid enrollees with severe mental illness following the FDA advisory and consensus statement publication. Although metabolic screening and monitoring recommendations have not been effective, sweeping changes in higher-risk metabolic agent use suggest that many clinicians and patients were aware of and responded to the metabolic risks associated with these medications.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

There were large shifts in olanzapine use following the FDA advisory and consensus statement publication.

Overall antipsychotic use declined only slightly among enrollees with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Treatment discontinuations did not increase among prevalent users following the advisory.

Decreases in olanzapine use suggest that many clinicians and patients were aware of and responded to the metabolic risk messages.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (RO1 HS0189960). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript for publication.

This manuscript is not under review, nor has it or any part of it been previously published in peer-reviewed media. All authors listed on this manuscript have met the outlined requirements for authorship. Funding information for this project, and potential author conflicts are noted below.

Footnotes

Author Funding / Potential Conflicts of Interest:

Stacie B. Dusetzina, PhD: Dr. Dusetzina currently receives funding through a Ruth L. Kirschstein-National Service Research Award Post-Doctoral Traineeship sponsored by NIMH and Harvard Medical School, Department of Health Care Policy, Grant No. T32MH019733-17. Dr. Dusetzina has no conflicts of interest.

Alisa B. Busch, MD, MPH: Dr. Busch received support from a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH071714). Dr. Busch has no conflicts of interest.

Rena M. Conti, PhD: No additional funding or disclosures. Dr. Conti has no conflicts of interest.

Julie M. Donohue, PhD: Dr. Donohue receives support from grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34 MH082682) and from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS017695). Dr. Donohue has no conflicts of interest.

G. Caleb Alexander, MD, MPH: Dr. Alexander is a consultant for IMS Health. Dr. Alexander has no conflicts of interest.

Haiden A. Huskamp, PhD: Dr. Huskamp receives support from a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Investigator Award in Health Policy Research. Dr. Huskamp has no conflicts of interest.

Presentation of Results:

A portion of this work was presented during the 27th International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management, Chicago IL August 14–17, 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amiel JM, Mangurian CV, Ganguli R, et al. Addressing cardiometabolic risk during treatment with antipsychotic medications. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:613–618. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328314b74b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodwin FK, Fireman B, Simon GE, et al. Suicide risk in bipolar disorder during treatment with lithium and divalproex. Jama. 2003;290:1467–1473. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.11.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:596–601. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrato EH, Nicol GE, Maahs D, et al. Metabolic screening in children receiving antipsychotic drug treatment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:344–351. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrato EH, Newcomer JW, Allen RR, et al. Prevalence of baseline serum glucose and lipid testing in users of second-generation antipsychotic drugs: a retrospective, population-based study of Medicaid claims data. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:316–322. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haupt DW, Rosenblatt LC, Kim E, et al. Prevalence and predictors of lipid and glucose monitoring in commercially insured patients treated with second-generation antipsychotic agents. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:345–353. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrato EH, Cuffel B, Newcomer JW, et al. Metabolic risk status and second-generation antipsychotic drug selection: a retrospective study of commercially insured patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:26–32. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31819294cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrato EH, Druss B, Hartung DM, et al. Metabolic testing rates in 3 state Medicaid programs after FDA warnings and ADA/APA recommendations for second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:17–24. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrato EH, Druss BG, Hartung DM, et al. Small area variation and geographic and patient-specific determinants of metabolic testing in antipsychotic users. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2011;20:66–75. doi: 10.1002/pds.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrato EH, Newcomer JW, Kamat S, et al. Metabolic screening after the American Diabetes Association's consensus statement on antipsychotic drugs and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1037–1042. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valluri S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, et al. Impact of the 2004 Food and Drug Administration pediatric suicidality warning on antidepressant and psychotherapy treatment for new-onset depression. Med Care. 2010;48:947–954. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ef9d2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan A. Consensus Panel Urges Monitoring for Metabolic Effects of Atypical Antipsychotics Psychiatric Times: UBM Medica. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koro CE, Fedder DO, L'Italien GJ, et al. An assessment of the independent effects of olanzapine and risperidone exposure on the risk of hyperlipidemia in schizophrenic patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1021–1026. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goode E. 3 Schizophrenia Drugs May Raise Diabetes Risk, Study Says The New York Times. New York: The New York Times; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anand G. NEW ANTIPSYCHOTICS POSE A QUANDARY FOR FDA, DOCTORS. WALL STREET JOURNAL. 2003:1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. MedWatch Safety Information: Geodon (ziprasidone) [Accessed 05/16/2011];2004 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm154977.htm. 2011.

- 17.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. MedWatch Safety Information: Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs. [Accessed 05/16/2011];2005 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm150688.htm.

- 18.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Florida Agency for Health Care Administration. Agency for Health Care Administration Announces NEW Medicaid Preferred Drug List. [Accessed 05/16/2011];2005 Available at: http://www.fdhc.state.flus/executive/communications/press_releases/archive/2005/07_06_2005.shtml.

- 20.Busch AB, Lehman AF, Goldman H, et al. Changes over time and disparities in schizophrenia treatment quality. Med Care. 2009;47:199–207. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818475b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busch AB, Frank RG, Lehman AF, et al. Schizophrenia, co-occurring substance use disorders and quality of care: the differential effect of a managed behavioral health care carve-out. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33:388–397. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Busch AB, Frank RG, Lehman AF. The effect of a managed behavioral health carve-out on quality of care for medicaid patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:442–448. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fullerton CA, Busch AB, Frank RG. The rise and fall of gabapentin for bipolar disorder: a case study on off-label pharmaceutical diffusion. Med Care. 2010;48:372–379. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ca404e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Neelon B, et al. Longitudinal racial/ethnic disparities in antimanic medication use in bipolar-I disorder. Med Care. 2009;47:1217–1228. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181adcc4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shrank WH, Choudhry NK, Fischer MA, et al. The epidemiology of prescriptions abandoned at the pharmacy. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:633–640. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-10-201011160-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberman JN, Berger JE, Lewis M. Prevalence of antihypertensive, antidiabetic, and dyslipidemic prescription medication use among children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:357–364. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1–36. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision) Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suppes T, Dennehy EB, Hirschfeld RM, et al. The Texas implementation of medication algorithms: update to the algorithms for treatment of bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:870–886. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sachs GS, Printz DJ, Kahn DA, et al. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder 2000. Postgrad Med. 2000;(Spec No):1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Standards of medical care in diabetes--2011. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(Suppl 1):S11–S61. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busch AB, Frank RG, Sachs G, et al. Bipolar-I patient characteristics associated with differences in antimanic medication prescribing. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2009;42:35–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou GY, Donner A. Extension of the modified Poisson regression model to prospective studies with correlated binary data. Statistical methods in medical research. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0962280211427759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Philip NS, Mello K, Carpenter LL, et al. Patterns of quetiapine use in psychiatric inpatients: an examination of off-label use. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20:15–20. doi: 10.1080/10401230701866870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Constantine R, Tandon R. Changing trends in pediatric antipsychotic use in Florida's Medicaid program. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1162–1168. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.10.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carpenter WT, Buchanan RW. Lessons to take home from CATIE. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:523–525. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faulkner G, Cohn T, Remington G. Interventions to reduce weight gain in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:654–656. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Compton MT, et al. A randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings: the Primary Care Access, Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:151–159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newcomer JW, Nasrallah HA, Loebel AD. The Atypical Antipsychotic Therapy and Metabolic Issues National Survey: practice patterns and knowledge of psychiatrists. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:S1–S6. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000142281.85207.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lester H, Tritter JQ, Sorohan H. Patients' and health professionals' views on primary care for people with serious mental illness: focus group study. Bmj. 2005;330:1122. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38440.418426.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Essock SM, Covell NH, Leckman-Westin E, et al. Identifying clinically questionable psychotropic prescribing practices for medicaid recipients in new york state. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1595–1602. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meyer JM, Davis VG, McEvoy JP, et al. Impact of antipsychotic treatment on nonfasting triglycerides in the CATIE Schizophrenia Trial phase 1. Schizophr Res. 2008;103:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Signorovitch J, Birnbaum H, Ben-Hamadi R, et al. Increased olanzapine discontinuation and health care resource utilization following a Medicaid policy change. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05868yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.