Abstract

There is growing recognition that policymakers can promote access to healthy, affordable foods within neighborhoods, schools, childcare centers, and workplaces. Despite the disproportionate risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes among American Indian children and adults, comparatively little attention has been focused on the opportunities tribal policymakers have to implement policies or resolutions to promote access to healthy, affordable foods. This paper presents an approach for integrating formative research into an action-oriented strategy of developing and disseminating tribally led environmental and policy strategies to promote access to and consumption of healthy, affordable foods. This paper explains how the American Indian Healthy Eating Project evolved through five phases and discusses each phase’s essential steps involved, outcomes derived, and lessons learned.

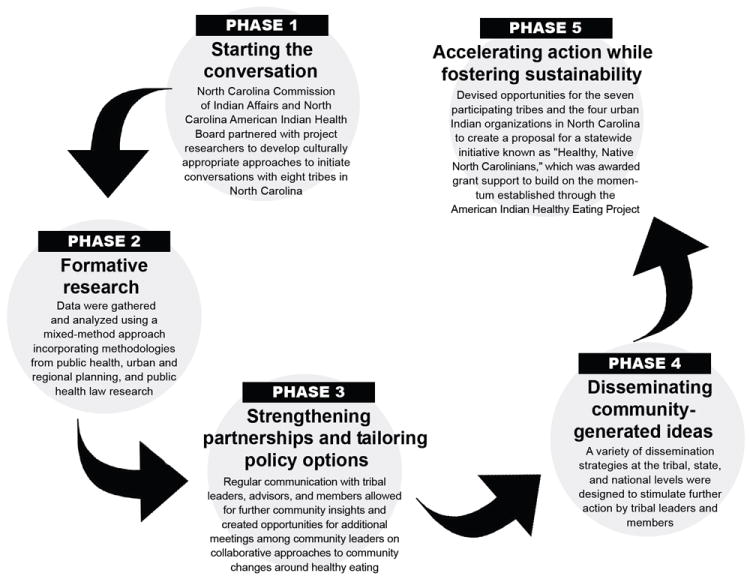

Using community-based participatory research and informed by the Social Cognitve Theory and ecologic frameworks, the American Indian Healthy Eating Project was started in fall 2008 and has evolved through five phases: (1) starting the conversation; (2) conducting multidisciplinary formative research; (3) strengthening partnerships and tailoring policy options; (4) disseminating community-generated ideas; and (5) accelerating action while fostering sustainability. Collectively, these phases helped develop and disseminate Tools for Healthy Tribes—a toolkit used to raise awareness among participating tribal policymakers of their opportunities to improve access to healthy, affordable foods. Formal and informal strategies can engage tribal leaders in the development of culturally appropriate and tribe-specific sustainable strategies to improve such access, as well as empower tribal leaders to leverage their authority toward raising a healthier generation of American Indian children.

Background

The rapid rise in obesity has forced researchers and policymakers to re-evaluate existing public health interventions, which have traditionally focused on improving an individual’s food and physical activity attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors.1 Expert reports have called attention to the social determinants of health and have specifically identified how the rapidly changing food and physical activity environments may be negatively contributing to an increase in energy intake, a decrease in physical activity, and the drastic rise in obesity and related chronic diseases.2-6 Promising approaches put forth are policy and programmatic changes that help make the healthy choice the easy choice.

Even though calls for government obesity prevention action have increased over the past 5 years, the role of tribal governance is often overlooked.2-6 The U.S. founding fathers acknowledged a special government-to-government relationship of the federal government with Indian tribes (Const., art. 1, §8). The Supreme Court determined in 1913 that the Constitution afforded federally recognized tribes certain inherent rights of self-government and entitlement to federal benefits, services, and protections.7 More than 16 states have granted tribes state recognition even though the tribes are not federally recognized.8

Overlooking tribal governance is problematic because tribal leaders may have untapped potential to address American Indians’ elevated risk for obesity through tribal resolutions and culturally appropriate community changes.9,10 American Indian preschoolers were found to have the highest prevalence of obesity among five major racial/ethnic groups in a recent cross-sectional study using a nationally representative sample of U.S. children, born in 2001 with height and weight measured in 2005: American Indian/Native Alaskan, 31.2%; Hispanic, 22.0%; non-Hispanic black, 20.8%; non-Hispanic white, 15.9%; and Asian, 12.8%.11

An 8-year obesity prevention program called Pathways was designed specifically to address the alarming rates of obesity among American Indian schoolchildren.12 The intervention focused on increasing physical activity and healthy-eating behaviors among schoolchildren in Grades 3 to 5, primarily through activities targeting the individual, family, and school. No changes in obesity prevalence rates were found. Pathway investigators recommended that future interventions employ more culture- and tribe-specific strategies, as well as integrate more sustainable environmental interventions and public policy approaches. Since the Pathway findings were published almost 10 years ago, little attention has been focused on how to engage tribal leaders in creating supportive environments to reduce obesity.

This paper presents an approach for integrating formative research into an action-oriented strategy of developing and disseminating tribally led environmental and policy strategies to promote access and consumption of healthy, affordable foods. This paper explains how the American Indian Healthy Eating Project evolved through five phases and discusses each phase’s essential steps, outcomes derived, and lessons learned. The project was created through partnerships between seven North Carolina American Indian tribes and a multidisciplinary research team at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (UNC). Through the support of a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant, the project aimed to build the partnerships and evidence base necessary to improve access to healthy, affordable foods within North Carolina American Indian communities. The focus of this project was improving access to healthy, affordable foods, with the hope that further work would be conducted to understand tribally led ways to promote active living.

Approach

The approach was based on Social Cognitve Theory13, ecologic frameworks,14-16 consumer behavior models, along with various theories and concepts trying to explain politicial decision-making and public policy participation. Figure 1 illustrates the project’s evolution and identifies essential steps and key outcomes of the following five phases of the American Indian Healthy Eating Project.

Figure 1.

Essential steps and key outcomes by phase of the American Indian Healthy Eating Project

Phase 1: Starting the Conversation

Using community-based participatory research,17,18 researchers at UNC established contacts in fall 2008 with members of the NC Commission of Indian Affairs (www.doa.state.nc.us/cia/). The commission is a division of the NC Department of Administration created by the state’s General Assembly to advocate and assist its American Indian citizens. The commission suggested using Talking Circles (i.e., facilitated discussions commonly used among American Indian communities) to initiate conversations with tribal leaders.19 The NC American Indian Health Board (ncaihb.org/) was also a part of these initial discussions and helped develop a research ethics review process for the current study.

The modified Talking Circle was designed to initiate conversations about research ethics, as well as tribally led approaches to improving access to healthy, affordable foods within tribal communities. The one federally recognized tribe in the state opted out of the project, citing existing obesity prevention programs. The following seven state-recognized tribes invited us to host a modified Talking Circle and through these discussions agreed to participate in the American Indian Healthy Eating Project: Coharie Indian Tribe, Haliwa-Saponi Indian Tribe, Lumbee Tribe of NC, Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation, Meherrin Indian Tribe, Sappony, and Waccamaw Siouan Tribe.

Phase 2: Conducting Multidisciplinary Formative Research

Formative research was conducted by combining methodologies from public health, regional and urban planning, and public health law.

Qualitative methodologies

The project used modified Talking Circles, as well as key informant one-on-one interviews to build relationships and garner insights from tribal leaders and key stakeholders because a variety of qualitative approaches was a recommended approach to building trust and gathering input from American Indians.12 Qualitative research is also a recommended approach to gathering input on the local food environment, particularly from a variety of perspectives.20 Two community liaisons, along with community advisors from participating tribes, assisted with the development of the modified Talking Circle protocol. One community liaison faciliated all seven modified Talking Circles. This liaison, in addition to two additional community liaisons, recruited and faciliated all key informant interviews.

Tribal leaders were recruited for the Talking Circles and were identified by each tribe. The categories of key informants were chosen by community advisors, and the individuals recruited were identified by community advisors, tribal leaders, or responded to seeing a recruitment flyer. Common themes arising during the modified Talking Circle discussions included concerns about obesity among tribal youth, facilitators and barriers to purchasing and preparing affordable, healthy meals, and the role of the family, church, and tribal community in moving forward healthy-eating initatives.

Additional community insights were garnered from 40 key informants through one-on-one interviews with community and spiritual leaders (n=13); health professionals (n=8); Indian educators (n=10); food-sector professionals (n=5); and parents (n=4). Key informants who were also parents were asked about their insights on these issues as parents too, totaling 13 parent participants. The key informants added invaluable perspectives on how to utilize Native traditions and empower tribal leaders to improve access to healthy eating within tribal communities.

Spatial analysis

Food-environment assessments were conducted to identify the types and locations of all food retail outlets within each of the seven participating tribal communities.21 Information was gathered from secondary data sources (i.e., health county food-registry lists and state agriculture registry lists, Dun & Bradstreet,® InfoUSA, and online Yellow Pages) and through a canvass by car of all primary roads within each of the communities. More than 1502 miles were canvassed; 711 food outlets were identified; evidence for validity of secondary food retail data sources was calculated; and inter-rater reliability of the methods was verified. The food landscapes of the tribal communities were characterized by country stores, gas stations with convenience stores, and fast-food restaurants.22 Two tribes had to travel more than 15 miles to reach the nearest full-service grocery store.

Public health law research

Informed by the qualitative and spatial preliminary findings, the American Indian Healthy Eating Project used methodologies from public health law research to identify the authority, as well as develop suggestions for feasible community changes that the participating tribes can implement to improve access to healthy, affordable foods within their tribal communities. Specifically, a systematic online collection and analysis of constitutions and websites of more than 500 tribes and urban Indian organizations in the U.S. was conducted. Three researchers coded with high agreement if and how constitutions, resolutions, and websites discussed food, nutrition, and health.

Preliminary findings indicate that tribal constitutions acknowledge the role of tribal government in health. For the more than 300 tribes with official websites, the health programs featured were the DHHS Indian Health Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations. Some examples of obesity policies or resolutions were identified through website reviews such as Cherokee Nation’s Healthy Nation initiative (healthynation.cherokee.org/). To develop appropriate guidance for participating tribes, expertise was sought from several participating tribal leaders, Indian health law scholars, and relevant agencies that promulgate regulations regarding Indian health, home preservation and canning, farmers’ markets, and Pow Wow concessions (i.e., food sold at a special form of gathering of North American Native Americans).

Phase 3: Strengthening Partnerships and Tailoring Policy Options

To avoid historical and contemporary research ethics-related injustices experienced by American Indians,12, 23-25 the research and community partners worked informally and formally to regularly meet and discuss the data and how they should be disseminated to the participating tribes. Tribal leaders expressed their appreciation of the project’s frequent in-person and written communications. The participating tribes were generally led by volunteers who often had a full agenda of items to discuss at their Tribal Council meetings, so the project regularly created short project updates in written or oral form.

Through intermittent review of preliminary findings and of the proposed toolkit table of contents, several suggestions were provided by tribal liaisons and leaders in person, over the phone, and via e-mail that assisted the success of the dissemination of policy options within the tribal communities. For example, a number of tribes requested that the toolkits be visual, integrating pictures of and artwork by tribal members. A website was also regularly requested as a way to make accessible, for multiple people, the study results and suggested policy strategies.

During conversations with tribal leaders, the name of the project itself emerged to emphasize American Indian and healthy eating versus the original name that focused more on food access. Further, the tribes felt it was important to continue discussions with relevant community partners, especially spiritual and church leaders. Although the project’s main focus was healthy eating, to respond to frequent requests about ideas for promoting physical activity, the toolkit and project website provided ideas on improving active living in general and, more specifically, about creating or renovating places to be physically active within tribal communities.

Overall, tribal leaders expressed that they felt their opinions were valued since they were regularly asked for their opinions. More importantly, they felt their insights and ideas were reflected in the project as it evolved. The frequent engagement encouraged further interest and action on this project, along with other health endeavors among community partners and members.

Phase 4: Disseminating Community-Generated Ideas

A toolkit and web-based resources known as “Tools for Healthy Tribes” (americanindianhealthyeating.unc.edu/tools-for-healthy-tribes/) was created. The kit’s format and content was largely based on community insights on the local food environment and ways to stimulate action by their tribal leaders and at the grass-roots level, because community members felt dissemination should be leveraged to stimulate action, not just hand out information. Tribal leaders and members grew increasingly interested in the project as opportunities to disseminate the project’s process and products developed.

Leaders and members also appreciated the “empowering tone” and how dissemination materials focused on what tribes can do, rather than just describing a problem “they are all well aware of.” Showing the food-assessment results using maps was helpful but often not as interesting to community members who expressed that they “know where they eat and why.” Many leaders expressed more interest in hearing about low-cost, immediate approaches they can take to address both economic development and health.

Phase 5: Accelerating Action While Fostering Sustainability

Building awareness about the project and its potential within the seven participating tribes helped accelerate action while fostering sustainability. State-recognized tribes are not recognized by the federal government and thereby not permitted to participate in the DHHS Indian Health Services or the U.S. Department of Agriculture Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations. Both of these programs increasingly provide opportunities, funding, and staff to focus on obesity prevention strategies. The support in data, technical assistance, as well as direct financial support of time, space, and staff, helped provide some critical funds to tribes to take action on healthy-eating strategies.

The Haliwa-Saponi Indian Tribe invested their grant support and additional grant funds awarded through another art project into their tribally owned and operated farmers’ market and started a community garden. These were great achievements considering state budget cuts at the time laid off the farmers’ market manager, who was instrumental in moving healthy-eating ideas forward. Finally, the American Indian Healthy Eating Project benefited from transitioning into Healthy, Native North Carolinians, a capacity-building project funded by Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust. This initiative directly supports the seven tribes, as well as the four urban Indian organizations in that state to develop, implement, and evaluate feasible and sustainable community changes regarding healthy eating and active living. This tribal government–state government–university collaborative project also provides support and technical assistance to strengthen capacity for meaningful, sustainable, and measurable changes.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Future Research and Practice

To our knowledge, this is one of the first projects that began working with multiple tribes in one state to explore the potential for tribally led efforts to maximize environmental and policy strategies to improve access to healthy, affordable foods. In addition, although toolkits and other forms of guidance on developing and implementing obesity prevention strategies have been increasingly created for policymakers, few of these guidance-oriented projects have shared the process by which they worked to engage policymakers—successfully or unsuccessfully—in developing evidence-based strategies to promote equitable access to healthy, affordable foods.26,27

Key lessons learned about initiating and sustaining partnerships with tribal communities to foster community changes regarding healthy eating were identified and translated into recommendations for future actions to address the alarming obesity and type 2 diabetes rates within Indian Country (Table 2). In addition, the project process and emerging products have been shared through in-person, phone, and e-mail consultations with other initiatives focusing on tribal or rural food access. That is, these findings have been discussed with more than 50 tribal leaders and stakeholders interested in responding to the call to action from Let’s Move! in Indian Country28 and maximizing funding opportunities such as the Association of American Indian Physicians’ Communities Putting Prevention to Work mini-grants.29

Table 2.

Translating lessons learned from the American Indian Healthy Eating Project into recommendations

| Lessons learned | Recommendations for future research and practice |

|---|---|

| Building awareness among tribal leaders about their authority and opportunity to create community changes for improving access to healthy, affordable foods can stimulate ideas and partnerships that can help address health disparities in Indian Country while addressing historical trauma | Use culturally appropriate strategies to initiate conversations with tribal leaders and develop guidance that is tailored to their unique authority and opportunity to develop policies and resolutions within their tribal communities that can improve access to healthy, affordable foods |

| Tailoring the partnership building process and approach to identifying particular community change strategies for an individual tribal community is necessary | Learn to recognize commonalities and differences among American Indian tribes from recognition status, governance structure, key sparkplugs and champions, community priorities and resources, and means of moving an idea forward |

| Changing political dynamics of a tribe’s leadership can alter the direction the tribe was currently pursuing regarding healthy-eating community changes | Create and re-create relationships with tribal policymakers as they are elected and re-elected |

| Connecting tribes to learn from and work together on community changes about healthy eating can maximize project potential | Stimulate discussions and partnerships within and among tribal communities while recognizing long-standing working relationships among particular tribes or historical or contemporary conflicts |

| Seeking approval for each step taken and dissemination strategy is not necessary if memorandums of understanding clearly identify when and how tribal approval is needed on a specific dissemination activity | Seek guidance from American Indian researchers and tribes with active research programs occurring within their communities on developing an operating memorandum of understanding that formally governs all aspects of the project including dissemination strategies and how the data can be used in further programs, presentations, papers, and grant proposals |

Conclusion

This innovative process has relevance to advancing the role of tribal-level obesity prevention strategies within participating communities and throughout Indian Country. Specifically, the steps taken to develop Tools for Healthy Tribes raised awareness at the tribal, state, and federal levels on the importance of engaging tribal leaders in obesity prevention and the need to “make it Native.” Future research is needed on how to engage tribal leaders and grass-roots movements to prevent obesity in Indian Country.

Table 1.

Community-generated ideas translated into American Indian Healthy Eating Project actions (themes and quotes are drawn from the seven modified Talking Circles (n=33) or key informant interviews (n=40))

Revitalizing Traditional Ways: “I want there to be resurgence and a reeducation of young Indian families to understand how we ate traditionally.”

|

Empowering Tribal Council and Community Sparkplugs: “The people don’t want to be beat down and beat down and beat down with what they need to do. The people need to be empowered on how they can do what they do with what they got.”

|

Using Intergenerational Approaches: “If we incorporate our elders and especially our women, then we’ll make change. But not only our elders because they’re dying out. We need to also incorporate the children. And a lot of times people focus on the elders and children and they leave out the middle generation so there needs to be something done with the ones who are being affected right now.”

|

Facilitating Economic Development: “Working with the youth, empowering the youth around healthy nutrition, empowering the youth around the health benefits from produce, empower the youth around economic opportunities with fresh produce.”

|

Addressing Historical Trauma: “So the problem is…how do you create real big catalyst for someone to really understand that getting sugar diabetes isn’t a fate of your whole entire family, that you actually can break that generational curse so to speak by just changing a mindset.”

|

Organizing the American Indian Community: “If you can bring these minds together, you’re gonna get more of a consensus. So…think about planning a general round table discussion about this issue with everybody that you interview and meet with.”

|

Acknowledgments

The authors’ tribal partners were essential to this project: Coharie Tribe, Haliwa-Saponi Indian Tribe, Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, Meherrin Indian Tribe, Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation, Sappony, and Waccamaw Siouan Tribe. The authors acknowledge the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs; specifically, Gregory Richardson and Missy Brayboy, and the NC American Indian Health Board; specifically Drs. Robin Cummings, Alice Ammerman, and Clara Sue Kidwell. Research assistance was provided by Leticia Brandon, Amanda Henley, Ingrid Ann Johnston, Ashley McPhail, and John Scott-Richardson. Joel Gittelsohn, Tony V. Locklear, and Edgar Villanueva provided invaluable feedback. The authors’ tribal liaisons were amazing: Tabatha Brewer, Sandra Bronner, Candice Collins, Dorothy Crowe, Karen Harley, Sharn Jeffries, Vivette Jeffries-Logan, Chief Thomas Lewis, Eric Locklear, Devonna Mountain, Julia Phipps, Al Richardson, Marty Richardson, and Dr. Aaron Winston.

This research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Healthy Eating Research Program (# 66958) and an NIH University of North Carolina Interdisciplinary Obesity Training Grant (T 32 MH75854-03).

This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent official views of the RWJF or NIH.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sallis JF, Story M, Lou D. Study designs and analytic strategies for environmental and policy research on obesity, physical activity, and diet: Recommendations from a meeting of experts. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(2 Suppl):S72–S77. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. Final Report whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241563703_eng.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.IOM of the National Academies Committee on Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention Food and Nutrition Board. Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation. Washington, DC: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity. Report to the President. Solving the Problem of Childhood Obesity within a Generation. 2010 May; doi: 10.1089/bfm.2010.9980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healthy Eating Active Living Convergence Partnership. Promising Strategies for Creating Healthy Eating and Active Living Environments. Prepared by Prevention Institute. San Francisco: Convergence Partnership; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC. Recommended Community Strategies and Measurements to Prevent Obesity in the U.S. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR-7):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U S v Sandoval, 231 US 28. 1913 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Indian Arts and Crafts Act, 25 USC §305e (d) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gittelsohn J, Rowan M. Preventing diabetes and obesity in American Indian communities: The potential of environmental interventions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(supp 1):1179S–1183S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.003509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schell L, Galloo M. Overweight and obesity among North American Indian infants, children, and youth. Am J Human Biology. 2012;24:302–313. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson S, Whitaker R. Prevalence of obesity among U.S. preschool children in different racial and ethnic groups. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(4):344–348. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gittelsohn J, Davis S, Steckler A, et al. Pathways: Lessons learned and future directions for school-based interventions among American Indians. Prev Med. 2003;27:S107–S112. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bandura A. Social Foundation of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davison K, Birch L. Childhood overweight: A contextual model and recommendations for future research. Obes Rev. 2001;2(3):159–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glanz K, Sallies J, Saelens B, Frank L. Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot. 2005;19(5):330–333. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Story M, Kaphingst K, Robinson-O’Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: Policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker E. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahota P NCAI Policy Research Center. Tribally-Driven Research. Community-Based Participatory Research in American Indian and Alaska Native Communities. 2010 Jun; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleischhacker S, Vu M, Ries A, McPhail A. Engaging tribal leaders in an American Indian Healthy Eating Project through Modified Talking Circles. Fam Community Health. 2011;34(3):202–210. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31821960bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Story M, G-C B, Yaroch A, Cummins S, Frank L, Huang T, Lewis B. Work Group IV: Future directions for measures of the food and physical activity environments. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4S):S182–S188. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleischhacker S, Rodriguez D, Evenson K, et al. Evidence for validity on five secondary data sources for enumerating retail food outlets in seven American Indian communities in North Carolina Under Review. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleischhacker S, Rodriguez D, Evenson K, et al. A mixed methods approach to understanding the food environment of seven American Indian tribes in North Carolina. 139th American Public Health Association Meeting; Washington, DC. October 31, 2011; ID#245193. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones D. The persistence of American Indian health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2122–2134. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stephens C, Porter J, Nettleton C, Willis R. Disappearing, displaced, and undervalued: A call to action for Indigenous health worldwide. Lancet. 2006;367:2019–2028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68892-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brugge D, Missaghian M. Protecting the Navajo People through tribal regulation of research. Sci Eng Ethics. 2006;12:491–507. doi: 10.1007/s11948-006-0047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jillcott Pitts S, Whetstone L, W JR, Smith T, Ammerman A. A community-driven approach to identifying “winnable” policies using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Common Community Measures for Obesity Prevention. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:110195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Izumi B, Schulz A, Israel B, et al. The one-pager: A practical policy advocacy tool for translating community-based participatory research into action. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2010;4(2):141–147. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Let’s Move! in Indian Country: Toolkit and Resource Guide. This toolkit was produced by the Let’s Move! in Indian Country interagency workgroup led by the White House, Domestic Policy Council, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Department of the Interior, DHHS, the U.S. Department of Education, and in collaboration with the Office of the First Lady’s Office, the CDC, the U.S. Department of Transportation, and the Corporation for National and Community Service.

- 29.Association of American Indian Physicians. Healthy, Active Native Communities $2,500 Awardees. www.aaip.org/?page=ARRASubcontractors.