Abstract

L-type voltage gated calcium channels (VGCCs) interact with a variety of proteins that modulate both their function and localization. A-Kinase Anchoring Proteins (AKAPs) facilitate L-type calcium channel phosphorylation through β adrenergic stimulation. Our previous work indicated a role of neuronal AKAP79/150 in the membrane targeting of CaV1.2 L-type calcium channels, which involved a proline rich domain (PRD) in the intracellular II-III loop of the channel.1 Here, we show that mutation of proline 857 to alanine (P857A) into the PRD does not disrupt the AKAP79-induced increase in Cav1.2 membrane expression. Furthermore, deletion of two other PRDs into the carboxy terminal domain of CaV1.2 did not alter the targeting role of AKAP79. In contrast, the distal carboxy terminus region of the channel directly interacts with AKAP79. This protein-protein interaction competes with a direct association of the channel II-III linker on the carboxy terminal tail and modulates membrane targeting of CaV1.2. Thus, our results suggest that the effects of AKAP79 occur through relief of an autoinhibitory mechanism mediated by intramolecular interactions of Cav1.2 intracellular regions.

Keywords: calcium channels, L-type, Cav1.2, AKAP79, AKAP18, Proline rich domain, Leucine Zipper motif

Introduction

Calcium influx through voltage gated calcium channels (VGCCs) mediates a range of key physiological functions, such as enzyme activation, muscle contraction, neurotransmitter release, and gene transcription.2-4 Several different calcium channel subtypes have been identified and classified by their distinct electrophysiological and pharmacological properties into T-, N-, L-, Q-, P-, and R-types. High-voltage activated calcium channels are transmembrane proteins with a pore-forming α1 subunit and auxiliary α2-δ, β and possibly γ subunits.5,6 Like many other membrane proteins, L-type calcium channels are subject to phosphorylation. The efficiency of second messenger regulation of voltage-gated calcium channels by cAMP/ PKA signaling is enhanced by different A-Kinase Anchoring Proteins (AKAPs) which act like scaffolding proteins generating microsignaling domains.7-14 By anchoring these enzymes close to the calcium channel substrate, they allow for tighter temporal and spatial control making them a very efficient regulatory signaling complex. The human brain isoform AKAP79 or its rodent ortholog AKAP150 is present in brain, skeletal and smooth muscle, and myocardium7-10 and is involved in a range of modulatory roles of ion channels, such as the GABAA receptor,15 glutamate receptor,16 inward rectifying potassium channels,17 and the M-current.18 AKAP79 is found in the postsynaptic density (PSD) and thought to be a central regulator of synaptic strength. The CaV1.2 L-type calcium channels are clustered at postsynaptic sites and are substrates for PKA, PP2A, calcineurin, and Calmodulin Kinase II (CamKII).14,19 The assembly of this signaling complex provides a mechanism for efficient modulation of dendritic excitability by β-adrenergic receptors, but in addition, it may also facilitate channel biogenesis.19,20 In cardiac myocytes, a similar regulation of L-type calcium channel by β-adrenergic receptor activation requires AKAP15/18 and involves a conserved leucine zipper motif in the C-terminal domain of the CaV1 calcium channel α1 subunit.8

We previously described an AKAP79-mediated targeting effect on CaV1.2 that was independent of PKA, and which involved a Proline Rich Domain (PRD) contained within the II-III linker of the channel.1 In this study we show that AKAP79 co-immunoprecipitates with CaV1.2. We identify the interacting motif of CaV1.2 that is involved in the AKAP79 mediated upregulation or stabilization of channel surface expression. We report that the C-terminal domain of CaV1.2 interacts with both AKAP79, as well as with the PRD of the II-III loop of the channel. AKAP79 binding to the C-terminal distal region competitively inhibits the association between the II-III loop and the carboxy terminus of CaV1.2, and thereby promotes channel targeting to the membrane. Furthermore, we show that the AKAP18 isoform, which interacts with a leucine zipper motif within the distal CaV1.2 C-terminal region, is unable to promote CaV1.2 membrane trafficking but antagonizes the AKAP79 effects. By mutating the leucine zipper motif we show that AKAP79 is still able to promote channel trafficking. Altogether these data suggest that the CaV1.2 C-terminal region integrates a crosstalk regulation by distinct AKAP isoforms.

Results

A single PRD into the II-III loop determines AKAP79-mediated increase in CaV1.2 current amplitude

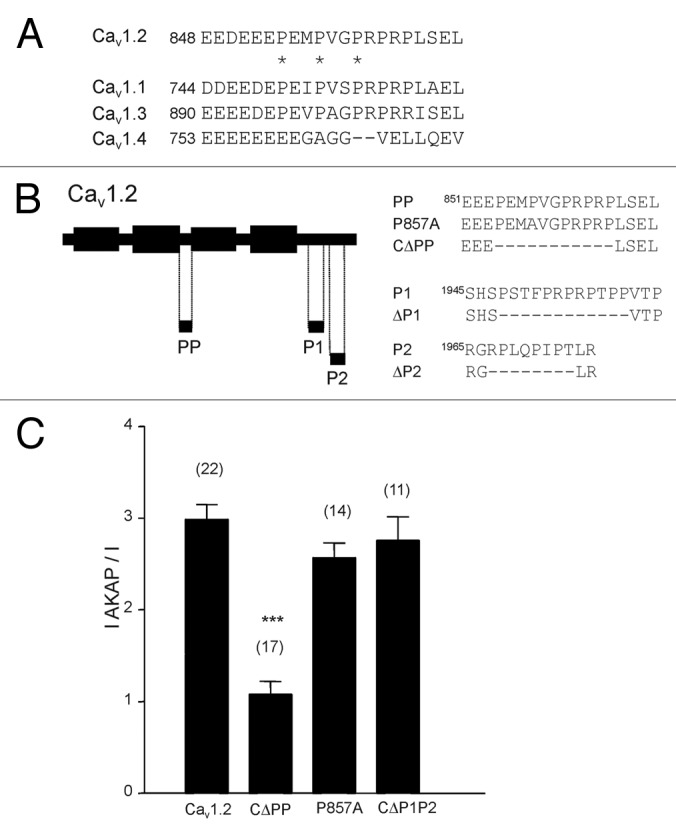

We previously reported the requirement of a Proline Rich Domain in the II-III loop of the CaV1.2 α1 subunit in AKAP79 mediated L-type channel targeting.1 This motif is conserved in CaV1.1 and CaV1.3 but not CaV1.4 (Fig. 1A). The C-terminal region of the channel contains two additional PRDs (see Figure 1B), which have not previously been investigated. To elucidate the role of these regions with respect to the action of AKAP79, we replaced Pro 857 in the II-III linker with alanine (Fig. 1B) in order to perturb two potential tandem SH3 binding domains (PxxPxxP) that are contained in the poly proline (PP) motif. In addition, we deleted the entire poly proline region in the II-III linker (CΔPP) plus the additional PRDs (P1 and P2) in the C-terminal domain of CaV1.2.

Figure 1. Substitution of Pro 857 by Ala in the Proline Rich Domain of the II-III loop and deletion of the two PRDs of the Cav2.1 C-terminus does not alter the AKAP79 modulation. (A) Conservation of the II-III-loop-PRD among the L type calcium channel family with the exception of CaV1.4 channels. (B) Schematic representation of the locations of PRDs along the Cav1.2 channel sequence, and amino acids sequence of the PRDs in the II-III linker and the C-terminus of CaV1.2. The top sequence is located in the domain II-III linker and starts at position 854. In the P875A mutant, Pro857 is replaced by Ala. The CΔPP mutant lacks the PEMPVGPRPRP stretch in the II-III linker. In the CΔP1P2 construct, the indicated proline rich regions at residues 1948 and 1967 are deleted. (C) Current amplitude ratio in the presence and absence of AKAP79 recorded for the different mutants. Current amplitude was taken at the peak of the I/V curve in each case and plotted as ratio between AKAP-injected and non-injected batches. Note that with the exception of the CΔPP mutant (without the poly-proline domain into the II-III loop), none of the other mutants are insensitive to AKAP79. Numbers in parenthesis indicate numbers of experiments.

Following co-expression of AKAP79 with wild type CaV1.2 in Xenopus oocytes, a robust enhancement of Cav1.2 current amplitude was observed with the wild type channel. Deletion of the PRD in the II-III loop made CaV1.2 surface expression insensitive to AKAP79 as described by us previously1(Fig. 1C). Neither the disruption of the putative SH3 domains in the II-III linker by the P857A point mutation, nor the removal of the PRDs in the C-terminus significantly antagonized the action of AKAP79 (CaV1.2, IAKAP / I = 2.98 ± 0.16, n = 22 ; CΔPP, IAKAP / I = 1.08 ± 0.14, n = 17 ; P857A, IAKAP / I = 2.56 ± 0.16, n = 14; CΔP1P2, IAKAP / I = 2.75 ± 0.25, n = 11). These results indicate that only the PP motif in the II-III loop is required for the AKAP79 effect. Moreover, although the presence of the PRD of the II-III loop is essential, altering the SH3 consensus motif did not abolish AKAP79 mediated upregulation.

CaV1.2 channels and AKAPs form a signaling complex

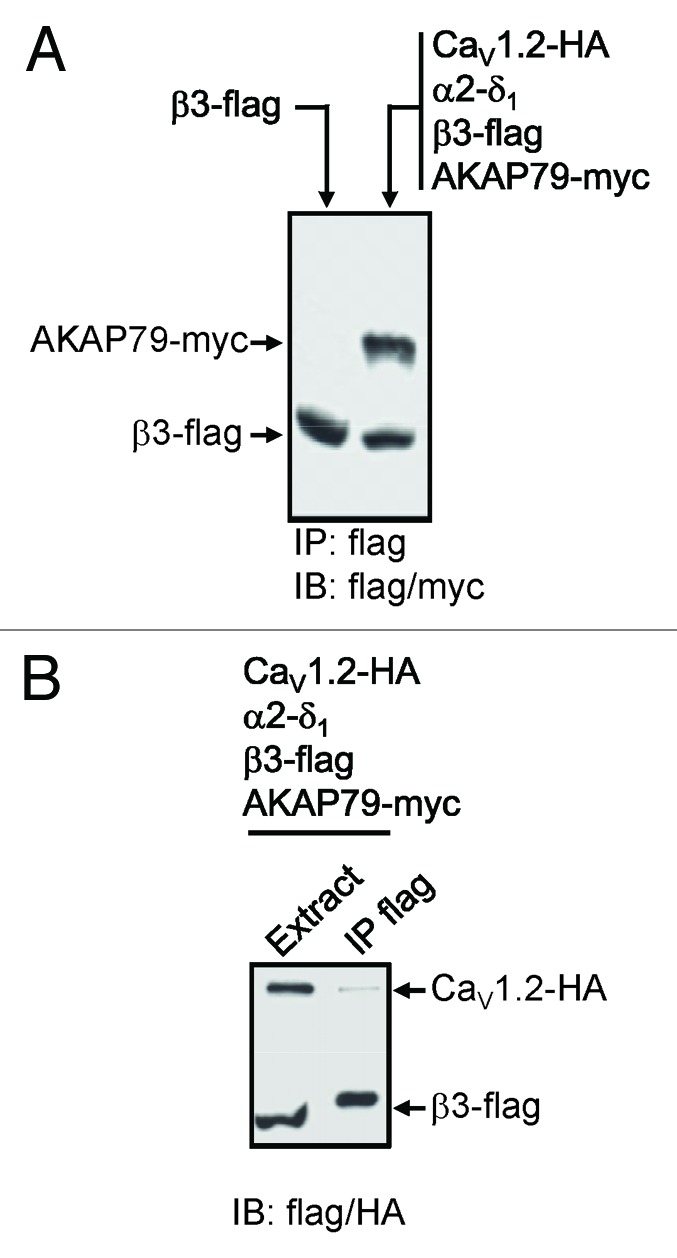

To demonstrate a physical interaction between AKAPs and the CaV1.2 channel as shown in native hippocampus between the AKAP79 mouse ortholog (AKAP150) and CaV1.2,12 we performed immunoprecipitation of the channel complex with myc-tagged AKAP79, HA-tagged CaV1.2 and β3-flag in tsA-201 cells using the anti-Flag Sepharose beads. Co-purification of the channel was assessed by western blot (Fig. 2). AKAP79-myc (Fig. 2A) and Cav1.2-HA (Fig. 2B) were found to co-immunoprecipitate with β3-flag subunit, thus corroborating the notion that L-type calcium channels and AKAP79 (or its ortholog) form a signaling complex.

Figure 2. Immunoprecipitation of CaV1.2 and AKAP79. (A) western blots of co-immunoprecipitations of CaV1.2-HA, calcium channel β3-flag, and AKAP79-myc in 1% CHAPS using FLAG sepharose beads. The anti-flag antibody identifies the β3-flag protein, while the AKAP79-myc protein is detected in the calcium channel complex indicating that AKAP79-myc binds to the calcium channel complex. (B) CaV1.2-HA is also immunoprecipitated by β3-flag protein as expected.

The distal C-terminal domain of CaV1.2 directly interacts with AKAP79

Considering the critical importance of the II-III-linker PRD in the functional effects of AKAP79, we wanted to determine by using a yeast two-hybrid system whether AKAP79 could physically interact with this region. However, as shown in Figure 3B, we could not detect an interaction between the domain II-III linker and AKAP79. As it has been shown that the coiled-coil domain of AKAP15/18 interacts with a leucine zipper in CaV1.1 calcium channels, we examined the CaV1.2 sequence for a similar motif, and indeed, as illustrated in Figure 3A, the C-terminus contains a leucine zipper like motif. Our initial findings showed that the AKAP79 trafficking effects do not rely on its coiled-coil domain.1 When we performed a yeast two-hybrid assay using a 106-amino acid long distal CaV1.2 region (aa 1997–2106) containing the leucine zipper, and the full length AKAP79, we detected a positive interaction between AKAP79 and the distal C-terminus of CaV1.2 using this assay (Fig. 3B). To confirm this interaction, we performed an in vitro binding assay between immobilized GST-AKAP79 and 6xHis fusion proteins of both the CaV1.2 full length C-terminus (residues 1526–2143), and of the distal C-terminus (residues 1997–2106). As shown in Figure 3C, both the CaV1.2 full length C-terminus and the shorter distal fragment bind to recombinant AKAP79 in vitro. Hence, the distal C-terminus and not the PRD in the II-III linker is the primary binding target of AKAP79.

Figure 3. AKAP79 directly binds to the leucine zipper motif in the C-terminus of the L-type calcium channel CaV1.2. (A) Amino acid sequence of the leucine zipper like motif in the C-terminal domain of CaV1.2. (B) Top: Schematic representation of the location of the II-III loop and the leucine zipper motif along the CaV1.2 channel sequence. Bottom: Yeast-two hybrid assay between AKAP79 and either the domain II-III linker, or the C-terminal leucine zipper motif of CaV1.2. pGAD was used as a negative control. Note the yeast growth in the leucine zipper/AKAP79 transformation. (C) In vitro binding of 6xHis CaV1.2 C-terminal and 6xHis Cav1.2 leucine zipper to immobilized AKAP79(GST). The western blot was probed using an anti-Xpress antibody (Invitrogen). Both the carboxy terminus and the Leucine Zipper motif bind to AKAP79.

AKAP79 antagonizes an intramolecular interaction between the CaV1.2 II-III linker and the C-terminus

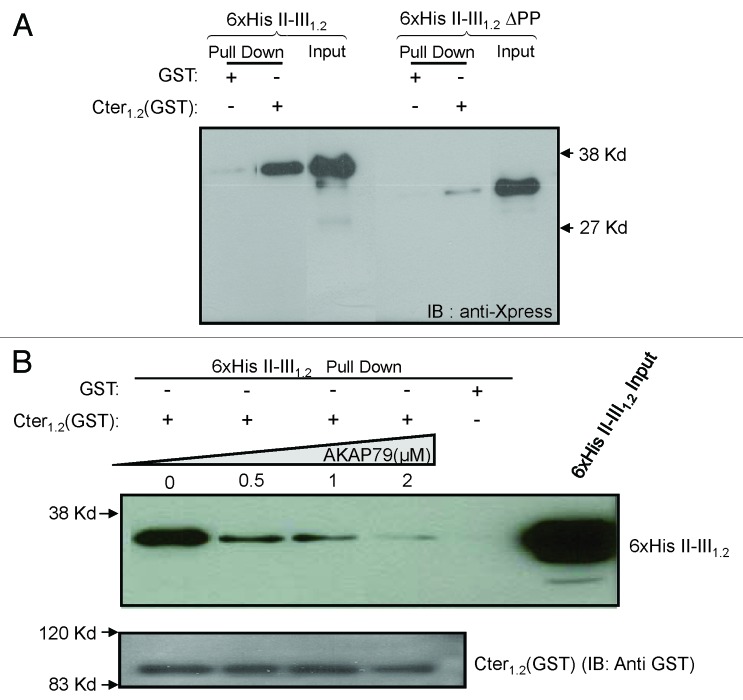

How can the functional role of the II-III PRD be reconciled with the lack of biochemical interaction with AKAP79? As we reported in our previous study,1 although deletion of the II-III linker PRD ablates the AKAP79 mediated upregulation, current densities were increased in the deletion mutant to the same levels as those observed with the wild type channel coexpressed with AKAP79, with no further effect of AKAP79. This might suggest the intact II-III linker is involved in an autoinhibition of channel expression that depends on a functionally intact PRD, which may perhaps be relieved in the presence of AKAP79. To observe this possibility, we examined whether AKAP79 might regulate the interaction of the II-III linker with another part off the channel, such as the C-terminus. As shown in Figure 4A, the II-III loop physically interacts with the C-terminus of the channel in vitro. Deletion of the PRD in the II-III linker virtually abolishes the interaction. However, no such interaction could be observed between the domain II-III linker and the leucine zipper region per se (not shown), indicating that a region distinct from the AKAP79 interaction site controls the intramolecular interaction between the C-terminus and the II-III loop. To determine whether AKAP79 could disrupt these intramolecular interactions within the channel protein, we incubated GST-fusion protein of the CaV1.2 C-terminus with increasing concentrations of recombinant AKAP79, and examined the consequences on 6xHis II-III linker binding. As shown in Figure 4B, AKAP79 competitively inhibited the II-III linker interactions with the C-terminus of the channel. These data therefore suggest that AKAP79 antagonizes an intrinsic interaction between the II-III linker and the C-terminus of the channel.

Figure 4. Interaction between the CaV1.2 C-terminal and II-III linker region. (A) In vitro binding of 6xHis II-III loop of CaV1.2 to immobilized CaV1.2 GST C-terminus. The western blot was probed using the anti-Xpress antibody. Grouping of images from different parts of the same gel have been made. (B) Binding between 6xHis II-III loop of CaV1.2 and CaV1.2 GST-C-terminal in the presence of increasing AKAP79 levels. Note that AKAP79 prevents the II-III linker C-terminus association. Bottom: Control blot to show that identical amounts of GST C-terminal fusion protein were used in the assay.

AKAP isoform dependence of the AKAP mediated effects on CaV1.2 membrane expression

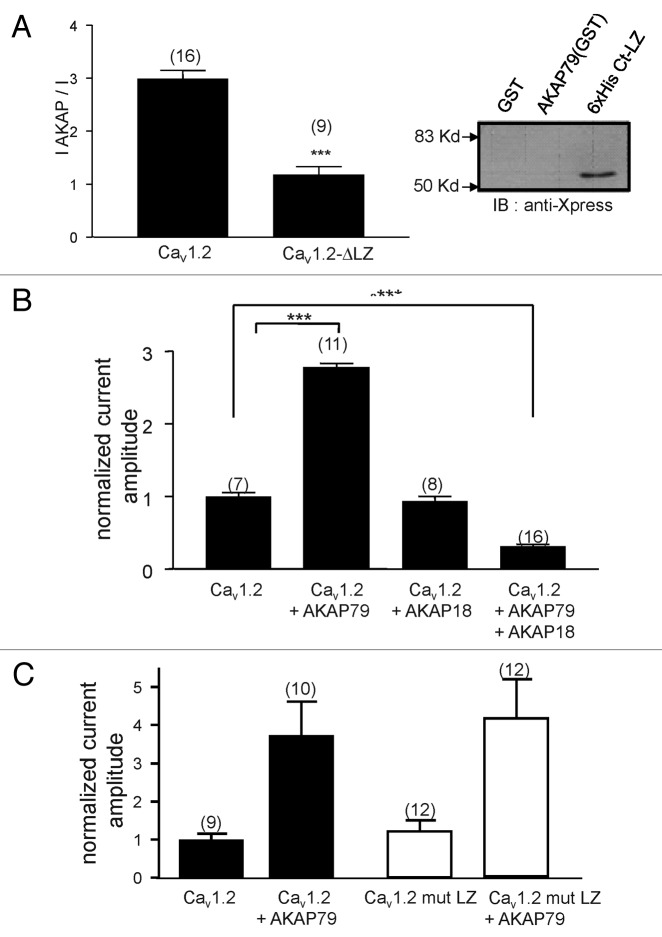

To confirm that the distal C terminus region containing the leucine zipper motif was indeed important for AKAP79 regulation, we deleted this region from CaV1.2 channel. As shown in Figure 5A, this resulted in ablation of in vitro binding of AKAP79 to the CaV1.2 C-terminus region, as well as the suppression of the functional effects of AKAP79 on L-type current amplitudes. AKAP15/18 also interacts directly with the C-termini of CaV1.1 and CaV1.2.8,21 To examine whether AKAP15/18 could mediate a similar functional effect as AKAP79, we determined whether AKAP15/18 coexpression could potentiate current amplitudes of wild type CaV1.2 channels. As shown in Figure 5B, AKAP15/18 failed to enhance CaV1.2 current amplitude. Interestingly, in the presence of AKAP15/18, the AKAP79 mediated enhancement of CaV1.2 expression was completely abolished (Fig. 5B, I(CaV1.2+AKAP79) = 2.72 ± 0.11, n = 11; I(CaV1.2+AKAP79+AKAP15/18) = 0.32 ± 0.08, n = 16), indicating that AKAP18 mediates a dominant negative effect on AKAP79 action but is unable to disrupt the auto-inhibitory interactions between the II-III linker and the C-terminus of the channel leading to membrane expression. To ascertain that AKAP79 and AKAP18 share overlapping binding site on the channel, three key residues of the leucine zipper were mutated to alanine. Figure 5C shows that (I2046A, F2053A, I2060A) mutations were without effect on basal current amplitude of Cav1.2 mut LZ. Furthermore, these mutations did not affect AKAP79-mediated current increase, suggesting that AKAP79 binding site(s) on distal CaV1.2 C terminus do not exclusively depends on the leucine zipper motif.

Figure 5. AKAP mediated effect is isoform dependent. (A) Mean AKAP79 effect on current amplitude recorded for CaV1.2 wt and a leucine zipper deletion mutant CaV1.2-LZ. Note that AKAP79 does not increase current amplitudes of CaV1.2 channels lacking the leucine zipper. Right panel: western blot of in vitro binding assay between AKAP79 and the C-terminal domain of CaV1.2 lacking the leucine zipper motif. Note that the CaV1.2-LZ C-terminus region cannot bind AKAP79 in vitro. (B) Effect of AKAP18 on the CaV1.2 current amplitude. AKAP18 does not mediate an increase in current amplitude, but acts as a dominant negative to suppress the AKAP79 mediated current enhancement.

Discussion

Our findings support the idea that AKAP79 enhances L-type Cav1.2 current density by disrupting an intramolecular inhibitory module acting on Cav1.2 channel. Here we show that this module requires intramolecular interaction within Cav1.2 intracellular linkers. This provides novel insights in to the molecular basis underlying the regulation of L-type calcium channels by the postsynaptic scaffolding protein AKAP79. As we showed previously,1 AKAP79 coexpression with CaV1.2 channels promotes surface expression of the channel. Whereas AKAP15 directly interacts with L-type channels via the Leucine Zipper motif21 our data suggest that AKAP79 directly binds to the CaV1.2 channel in the distal part of the C-terminus nearby the leucine zipper motif. Second, we present evidence that the II-III linker of the channel can interact with the C-terminus in vitro, and that this interaction is critically dependent on the presence of a proline rich domain in the II-III linker region, but does not involve the leucine zipper. Finally, we show that AKAP79 binding to the C-terminus competitively inhibits the II-III linker C-terminus interaction. Based on this collective evidence, and our previous work,1 we propose the following model. In the absence of AKAP79, the II-III linker region and the C-terminus of the channel are bound to each other. In this conformation, the channel has a reduced likelihood of being transported to the plasma membrane. Disruption of the II-III linker interaction with the C-terminus via deletion of the II-III linker PRD results in an increased efficiency of membrane expression.1 AKAP79, by associating nearby the leucine zipper motif in the C-terminus may sterically interfere with the II-III linker C-terminus interaction, thereby removing the autoinhibitory effect on membrane expression. These results are consistent with our previous observation that removal of the II-III linker PRD results in an upregulation of membrane expression with no additional effect of AKAP79. In contrast, AKAP18 did not mediate an increase in CaV1.2 current density despite being able to bind to the CaV1.2 C-terminus,8 but acted in as a dominant negative inhibitor of the AKAP79 effects. This suggests that AKAP79 and AKAP15/18 compete for a close region of the channel, but that only AKAP79, is capable of disrupting the interaction between the C-terminus and the II-III linker region of the channel. Whether AKAP79 interactions with Cav1.2 can regulate the ubiquitination state of the channel, as reported recently for ancillary Cavβ subunits, remains to be determined.22

AKAP proteins are key regulators of various types of ion channel proteins.14,23 Previous studies have established the interaction between mAKAP and ryanodine- sensitive calcium-release channels of the sarcoplasmic reticulum,24 Yotiao (another member of AKAP family) and the Iks channel subunit hKCNQ1.25 These interactions appear to also involve a leucine zipper like motif. Similar interactions between AKAP15/18 and CaV1.1 in skeletal muscle,21 CaV1.2 and AKAP15/18 or AKAP79 in cardiac myocytes and in neuronal tissues8,12,13,20,26 or CaV1.3 and AKAP15/18 in brain have been reported.13 Hence, there appear to be conserved motifs across multiple types of ion channels that regulate interactions with AKAPs and related proteins. In addition, AKAP79 interactions with cognate partners also involve non leucine zipper motifs as in TREK1 background potassium27or Kv4.2 channels.28 Additional interacting motifs were also found in the N-terminus and the I-II linker of Cav1.2 calcium channel,12,14 although in this latter case these sites seem to be secondary sites compared with the one located in the C-terminus.13,20

It is noteworthy that C-terminal fragments of CaV1.2 have been shown to be post-translationally cleaved,29 but nonetheless remains localized near the plasma membrane.30 These hydrophilic C-terminal fragments associate with and affect the PKA-mediated regulation of L-type Cav1.2 channels in particular in the heart.11,31 It is not clear whether AKAP79 interacts with these cleaved fragments, or whether a tethered C-terminus is required. Moreover, it remains to be established as to whether proteolytically cleaved C-terminal fragments associate with the II-III linker region in vivo. However, the observation that splice isoforms of CaV1.2 with shorter C-termini31 or artificially truncated CaV1.2 channels (Stotz and Zamponi, unpublished observations) produce drastically enhanced whole cell currents, is consistent with the removal of an autoinhibitory mechanism that is intrinsic to the CaV1.2 subunit and depends on the distal C-terminus domain.11 Finally these results have to be considered in the context of recent study showing that deletion of the Cav1.2 distal C-terminus in mice leads to reduced L-type channel functional activity in hippocampal and heart cells.13,26 Therefore, further experiments will be needed to find a consensus about the role of C-terminus proteolytic fragments on the AKAP79-mediated regulation of Cav1.2 in vivo.

A physical interaction among cytoplasmic regions of calcium channels is not without precedent. For example, the I-II loop of Cav2.1 is able to directly associate with the C-terminal, N-terminal and III-IV loop of the channel.32 The interaction between the domain I-II linker and the III-IV loop of that channel occurs only in the absence of the calcium channel β subunits. The proximal and distal C-terminal fragments of Cav1.2 interact with each other and their association/dissociation influence Cav1.2 channel PKA-dependent modulation.11 Hence, the intracellular side of the channel does not simply consist of loosely hanging tails and linkers, but may instead comprise a tightly packed web of various cytoplasmic regions, whose association may be regulated by proteins such as AKAPs and possibly accessory calcium channel subunits as well as calcium sensors such as calmodulin.33 It is well established that L-type calcium channels mediate calcium-dependent gene transcription by activating calmodulin molecules that are preassociated with the C-terminus of the channel.34 It is also known that L-type calcium channel localization and AKAP79-L-type channel interactions are critical for the regulation of gene transcription.20,35,36 Moreover, AKAP79 is most definitely a calmodulin binding protein,37 and activation of calmodulin induces a release of AKAP79 from the plasma membrane.38-40 Hence, L-type channels appear to exist as a multiprotein signaling complex in the postsynaptic membrane, whose composition may be dynamically regulated by physiological stimuli. Indeed, NMDA receptor stimulation disrupts AKAP79 localization in dendritic spines, and results in a diffuse redistribution in the cell soma.39-41 This suggests the possibility that under glutamate stimulation, AKAP79 could contribute to the import/export/movement of L-type channels between the soma and at more distal sites such as the dendritic spines. This dynamic process may also regulate gene transcription mediated by L-type calcium influx.36 Thus, the picture emerges that AKAP79 may act as a key signaling molecule for regulation of L-type channel function.

Materials and Methods

Molecular biology

Deletions of the PP motif in the CaV1.2 II-III loop (aa 854 to 864) were created by overlapping PCR using as template a wild type CaV1.2 cDNA engineered to contain two unique silent restriction sites (MluI and SpeI) flanking the II-III loop region. The amplified 780 bp MluI-SpeI fragment was reintroduced into the template DNA. Mutant P857A was created by site-directed mutagenesis within the MluI-SpeI fragment and reintroduced into template DNA. The Leucine Zipper ∆LZ mutant (I2046A, F2053A, I2060A) and deletions in the C-terminal domain of CaV1.2 were obtained by site directed mutagenesis and PCR overlap extension respectively, in the SpeI-BsrGI fragment then cloned into the Cav1.2 pMT2 plasmid backbone.

To create Yeast Two-hybrid assay constructs, the II-III loop, the C-terminal domain and the leucine zipper motif of CaV1.2 were subcloned in frame into the Gal4 DNA binding domain vector pGBT11. AKAP79 was subcloned into the Gal 4 activation domain vector pGAD.

For in vitro binding assays, AKAP79, the II-III loop and the C-terminal domain of CaV1.2 were subcloned into pGEX-4T-3 and pGEX-5T-1 respectively (Amersham Biosciences) to make Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins. For 6xHis fusion proteins, the II-III loop, C-terminal domain, ΔPPII-III loop, Cter-LZ and Leu Zipper motif of CaV1.2 were subcloned into the pTrcHis vector (Invitrogen). AKAP79 tagged with the c-Myc epitope was created by PCR amplification and subcloning into c-Myc/pcDNA3. The HA-CaV1.2 construct has been previously described1 and the β3-flag was generously provided by Dr T.P. Snutch. Accuracy of the various constructs was analyzed by sequencing and restriction digests.

Yeast Two-hybrid assay

Direct interaction between the CaV1.2 constructs and AKAP79 was analyzed by both co-transformation and mating using the Y190 yeast strain. Yeast was mixed with 500 μl PEG (50% w/v), 100 μl of 0.1 M lithium acetate pH 8, 2 μl of ssDNA and 1 μg of DNA construct. The mix was incubated at room temperature for 4 h then heat shocked at 42°C for 20 min. Yeast was pelleted at 2000 tr/min and resuspended in 500 μl H2O, pelleted again and resuspended in 100 μl H2O and finally plated on appropriate YPD medium. Clones were selected in media without tryptophan, leucine and histidine supplemented with 0.04% X-gal and 20 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) to reduce the background growth of the Y190 yeast strain. Mated yeast that had both plasmids grew on leu-, trp- plates, then, they were allowed to grow for approximately 3 d on leu-, trp-, his- plates.

Transient expression of recombinant calcium channels

The following cDNA sequences inserted in expression vectors were used (GenBank™ accession numbers are in parentheses): CaV1.2 (M67515), β1b (NM017346), α2-δ1-b (AF286488), AKAP79 (NM004857), AKAP15/18 (NM004842). For transient expression in Xenopus oocytes, nuclear injection was performed as previously reported.1 When AKAP79 was coexpressed with the Ca2+ channel subunits, we used a ratio of 1 (AKAP) to 3 (Ca2+ channel mix). As control, the empty vector was used to obtain the same dilution. Oocytes were then incubated at 18°C for 2 to 4 d in ND96 medium on rotating platform.

Electrophysiology

Macroscopic oocyte currents were recorded using two-electrode voltage-clamp as previously described1 using 5mM Barium as charge carrier. pCLAMP7 software was used for data acquisition and analysis was performed with pCLAMP9, Excel and GraphPad Prism software. Results are presented as the mean ± SEM, and compared using student t-tests or ANOVAS for multiple comparisons.

Purification of fusion proteins

6xHis constructs in pTrcHis vector were transformed in Escherichia coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen). Constructs were grown in a 200 ml culture of SOB broth to A600 = 0.6, at which point protein expression was induced with 100 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside and the cultures were grown for 3.5 to 4 h. Cells were harvested, lysed by 3 cycles of sonication/freeze thaw in the presence of 100 μl of egg white lysozyme (Sigma) and 20 μl of protease inhibitor mixture containing 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride, bestatin, pepstatin, E-64, phosphoramidon (Sigma, P-8849). The lysates were treated with RNase A (5μg/ml), centrifuged to remove insoluble debris, filtered, and used immediately or stored at -80°C. Batch purifications proceeded as follows: Ni2-NTA beads (Qiagen) were buffer equilibrated with phosphate-buffered saline (20 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.8, 500 mM NaCl) and made up to 50%. All incubations/washes were conducted at 4°C. Beads were incubated with 3 volumes of lysate in the presence of 12 mM imidazole, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1%Triton X-100 for 30 min at 4°C, followed by a 10 min washing. The wash buffer consisted of 20 mM Na2HPO4, pH 6.0, 500 mM NaCl, 21 mM imidazole, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% Triton X-100. The beads were then incubated a second time then washed with 2x30 bed volumes of wash buffer for 15 min each. For elution, proteins were incubated at 4°C for 30 min in 20 mM Na2HPO4, pH 6.0, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole. Eluted proteins were dialyzed overnight in Slide-A-Lyzer cassettes (Pierce) at 4°C. 6xHis proteins were use immediately or stored at -80°C.

Constructs in pGEX vectors were transformed into BL21 cells. A 1-L culture at 37°C was grown to A600 = 0.5, at which point protein expression was induced by 0.1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside. Cells were grown for 4 h and harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 35 ml of resuspension buffer (PBS supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20, 2 mM EDTA, 350 mM NaCl, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, and 20 μl of protease inhibitor mixture P8849 (Sigma), and passed through a French press. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation. Glutathione-Sepharose beads (Sigma) were equilibrated with PBST and made to yield a 50% slurry for batch purification. 50% beads were incubated 1:3 with the lysate for 1 h followed by a 20 bed volume wash with PBST and a second incubation with lysate. The final washes consisted of 20 bed volumes of PBST for 10 min, 20 bed volumes of MKM buffer (10 mM MOPS, pH 7.5,150 mM KCl, 4.5 mM Mg(CH3COO)2, 0.2% Triton X-100) for 10 min, 20 bed volumes of PBST supplemented with 350 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol for 10 min, and finally 20 bed volumes of PBST for 10 min. After the final wash, the beads were resuspended to obtain a 50% slurry in PBST, which was subsequently used for binding assays.

In vitro binding assay

Beads-bound GST fusion proteins were incubated at 4°C with purified 6xHis fusion proteins for 2 h. For competition assay, GST-AKAP79 was purified on Glutathione-Sepharose beads and then cleaved from GST using Thrombin. Each reaction was washed at least 30 min with PBST before proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Biosciences). Membranes were probed with an anti-Xpress antibody to detect polyHis tags (1:2500 dilution, Invitrogen) or anti GST (diluted 1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) and Western analysis was detected using ECL detection methods. All in vitro binding assays were repeated three times.

Immunoprecipitation

Transfection of tsA-201 cells was performed in 35 mm dishes using JETPEI (Q-Biogen). The mixture of DNA was as follows; 1 μg of CaV1.2-HA, 0.5 μg of α2-δ1, 0.5 μg of AKAP79-myc and 100 ng of β3-flag plasmid; for the β3-flag alone, 100ng of β3-flag plasmid was used with 1.9 μg of pcDNA3.1 vector. The cells were incubated for 48 h and harvested in 1% CHAPS in PBS + protease inhibitor mix (Boehringer Mannheim). The mixture was vortexed and then centrifuged for 15 min. Anti-FLAG beads (Sigma) were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. Beads were washed 3X (10 min incubations) with 1% CHAP in PBS. 40 μl of 200 mM Glycine (pH 2.5) was added and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The supernatant was removed after a brief centrifugation and neutralized with 1μl of 1M Tris (pH 12). The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Primary antibody incubation was performed overnight with a mouse anti-flag M2 antibody (1:1000; Sigma) in 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Blots were washed 3 times and incubated subsequently using a sheep anti-mouse secondary HRP (Amersham NXA931; 1:10000) for 45 min. This was followed by 3 washes with PBS. ECL was used to detect HRP activity (ECL Western Blot detecting reagents-Amersham). Subsequently for detection of the myc epitope, a primary anti-myc antibody (clone 9E10) at a 1:1000 dilution was used following the same incubation and washing procedure. Mouse secondary HRP was used at a concentration of 1:5000. The HA epitope was detected by using a rat anti-HA primary antibody (1:1000; Roche) with a subsequent incubation with a goat anti-rat-HRP secondary (1:5000; Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Acknowledgments

We thank Terry P. Snutch for providing calcium channel subunit expression vectors. We thank Francois Rassendren for technical help. This work was supported by the Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM), by a Programme International de Collaboration Scientifique du CNRS (PICS), by the Montpellier Genopole and IFR3 technical facilities, by NIH Grant GM482312 (JDS), an operating grant to CA from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Alberta, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut (HSF), and a grant to GWZ from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council. GWZ is a Scientist Scholar of the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR) and a Canada Research Chair. SCS held studentships from the AHFMR and CIHR, SEJ was supported by an AHFMR MD/PhD studentship.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- VGCC

voltage gated calcium channel

- PKA

protein kinase A

- AKAP

A-kinase anchoring protein

- PP

poly-prolines

- PRD

proline rich domain

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- bp

base pair

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/channels/article/20865

References

- 1.Altier C, Dubel SJ, Barrère C, Jarvis SE, Stotz SC, Spaetgens RL, et al. Trafficking of L-type calcium channels mediated by the postsynaptic scaffolding protein AKAP79. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33598–603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:521–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Currie KP. G protein modulation of CaV2 voltage-gated calcium channels. Channels (Austin) 2010;4:497–509. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.6.12871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cain SM, Snutch TP. Contributions of T-type calcium channel isoforms to neuronal firing. Channels (Austin) 2010;4:475–82. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.6.14106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catterall WA. Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a003947. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner RW, Anderson D, Zamponi GW. Signaling complexes of voltage-gated calcium channels. Channels (Austin) 2011;5:440–8. doi: 10.4161/chan.5.5.16473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao T, Yatani A, Dell’Acqua ML, Sako H, Green SA, Dascal N, et al. cAMP-dependent regulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels requires membrane targeting of PKA and phosphorylation of channel subunits. Neuron. 1997;19:185–96. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80358-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hulme JT, Lin TW, Westenbroek RE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Beta-adrenergic regulation requires direct anchoring of PKA to cardiac CaV1.2 channels via a leucine zipper interaction with A kinase-anchoring protein 15. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13093–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135335100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson BD, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Voltage-dependent potentiation of L-type Ca2+ channels in skeletal muscle cells requires anchored cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:11492–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong J, Hume JR, Keef KD. Anchoring protein is required for cAMP-dependent stimulation of L-type Ca(2+) channels in rabbit portal vein. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C840–4. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.4.C840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller MD, Emrick MA, Sadilek M, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular mechanism of calcium channel regulation in the fight-or-flight response. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra70. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall DD, Davare MA, Shi M, Allen ML, Weisenhaus M, McKnight GS, et al. Critical role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase anchoring to the L-type calcium channel Cav1.2 via A-kinase anchor protein 150 in neurons. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1635–46. doi: 10.1021/bi062217x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall MR, Clark JP, 3rd, Westenbroek R, Yu FH, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Functional roles of a C-terminal signaling complex of CaV1 channels and A-kinase anchoring protein 15 in brain neurons. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12627–39. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai S, Hall DD, Hell JW. Supramolecular assemblies and localized regulation of voltage-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:411–52. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandon NJ, Jovanovic JN, Colledge M, Kittler JT, Brandon JM, Scott JD, et al. A-kinase anchoring protein 79/150 facilitates the phosphorylation of GABA(A) receptors by cAMP-dependent protein kinase via selective interaction with receptor beta subunits. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:87–97. doi: 10.1016/S1044-7431(02)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tavalin SJ, Colledge M, Hell JW, Huganir RL, Scott JD. Regulation of Glur1 by the AKAP79 signaling complex shares properties with LTD. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3044–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03044.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali S, Chen X, Lu M, Xu JZ, Lerea KM, Hebert SC, et al. The A kinase anchoring protein is required for mediating the effect of protein kinase A on ROMK1 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10274–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoshi N, Zhang JS, Omaki M, Takeuchi T, Yokoyama S, Wanaverbecq N, et al. AKAP150 signaling complex promotes suppression of the M-current by muscarinic agonists. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:564–71. doi: 10.1038/nn1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davare MA, Avdonin V, Hall DD, Peden EM, Burette A, Weinberg RJ, et al. A beta2 adrenergic receptor signaling complex assembled with the Ca2+ channel Cav1.2. Science. 2001;293:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5527.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliveria SF, Dell’Acqua ML, Sather WA. AKAP79/150 anchoring of calcineurin controls neuronal L-type Ca2+ channel activity and nuclear signaling. Neuron. 2007;55:261–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hulme JT, Ahn M, Hauschka SD, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. A novel leucine zipper targets AKAP15 and cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase to the C terminus of the skeletal muscle Ca2+ channel and modulates its function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4079–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altier C, Garcia-Caballero A, Simms B, You H, Chen L, Walcher J, et al. The Cavβ subunit prevents RFP2-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of L-type channels. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:173–80. doi: 10.1038/nn.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraser ID, Cong M, Kim J, Rollins EN, Daaka Y, Lefkowitz RJ, et al. Assembly of an A kinase-anchoring protein-beta(2)-adrenergic receptor complex facilitates receptor phosphorylation and signaling. Curr Biol. 2000;10:409–12. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00419-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, et al. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell. 2000;101:365–76. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marx SO, Kurokawa J, Reiken S, Motoike H, D’Armiento J, Marks AR, et al. Requirement of a macromolecular signaling complex for beta adrenergic receptor modulation of the KCNQ1-KCNE1 potassium channel. Science. 2002;295:496–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1066843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu Y, Westenbroek RE, Yu FH, Clark JP, 3rd, Marshall MR, Scheuer T, et al. Deletion of the distal C terminus of CaV1.2 channels leads to loss of beta-adrenergic regulation and heart failure in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12617–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandoz G, Thümmler S, Duprat F, Feliciangeli S, Vinh J, Escoubas P, et al. AKAP150, a switch to convert mechano-, pH- and arachidonic acid-sensitive TREK K(+) channels into open leak channels. EMBO J. 2006;25:5864–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin L, Sun W, Kung F, Dell’Acqua ML, Hoffman DA. AKAP79/150 impacts intrinsic excitability of hippocampal neurons through phospho-regulation of A-type K+ channel trafficking. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1323–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5383-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hell JW, Westenbroek RE, Breeze LJ, Wang KK, Chavkin C, Catterall WA. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-induced proteolytic conversion of postsynaptic class C L-type calcium channels in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3362–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerhardstein BL, Gao T, Bünemann M, Puri TS, Adair A, Ma H, et al. Proteolytic processing of the C terminus of the alpha(1C) subunit of L-type calcium channels and the role of a proline-rich domain in membrane tethering of proteolytic fragments. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8556–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao T, Cuadra AE, Ma H, Bunemann M, Gerhardstein BL, Cheng T, et al. C-terminal fragments of the alpha 1C (CaV1.2) subunit associate with and regulate L-type calcium channels containing C-terminal-truncated alpha 1C subunits. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21089–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornet V, Bichet D, Sandoz G, Marty I, Brocard J, Bourinet E, et al. Multiple determinants in voltage-dependent P/Q calcium channels control their retention in the endoplasmic reticulum. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:883–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minor DL, Jr., Findeisen F. Progress in the structural understanding of voltage-gated calcium channel (CaV) function and modulation. Channels (Austin) 2010;4:459–74. doi: 10.4161/chan.4.6.12867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dolmetsch RE, Pajvani U, Fife K, Spotts JM, Greenberg ME. Signaling to the nucleus by an L-type calcium channel-calmodulin complex through the MAP kinase pathway. Science. 2001;294:333–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1063395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weick JP, Groth RD, Isaksen AL, Mermelstein PG. Interactions with PDZ proteins are required for L-type calcium channels to activate cAMP response element-binding protein-dependent gene expression. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3446–56. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03446.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Pink MD, Murphy JG, Stein A, Dell’Acqua ML, Hogan PG. Balanced interactions of calcineurin with AKAP79 regulate Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT signaling. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:337–45. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faux MC, Scott JD. Regulation of the AKAP79-protein kinase C interaction by Ca2+/Calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17038–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dell’Acqua ML, Faux MC, Thorburn J, Thorburn A, Scott JD. Membrane-targeting sequences on AKAP79 bind phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate. EMBO J. 1998;17:2246–60. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Biase V, Obermair GJ, Szabo Z, Altier C, Sanguesa J, Bourinet E, et al. Stable membrane expression of postsynaptic CaV1.2 calcium channel clusters is independent of interactions with AKAP79/150 and PDZ proteins. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13845–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3213-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Di Biase V, Tuluc P, Campiglio M, Obermair GJ, Heine M, Flucher BE. Surface traffic of dendritic CaV1.2 calcium channels in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13682–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2300-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gomez LL, Alam S, Smith KE, Horne E, Dell’Acqua ML. Regulation of A-kinase anchoring protein 79/150-cAMP-dependent protein kinase postsynaptic targeting by NMDA receptor activation of calcineurin and remodeling of dendritic actin. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7027–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07027.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]