Abstract

Bupivacaine is a local anesthetic compound belonging to the amino amide group. Its anesthetic effect is commonly related to its inhibitory effect on voltage-gated sodium channels. However, several studies have shown that this drug can also inhibit voltage-operated K+ channels by a different blocking mechanism. This could explain the observed contractile effects of bupivacaine on blood vessels. Up to now, there were no previous reports in the literature about bupivacaine effects on large conductance voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channels (BKCa). Using the patch-clamp technique, it is shown that bupivacaine inhibits single-channel and whole-cell K+ currents carried by BKCa channels in smooth muscle cells isolated from human umbilical artery (HUA). At the single-channel level bupivacaine produced, in a concentration- and voltage-dependent manner (IC50 324 µM at +80 mV), a reduction of single-channel current amplitude and induced a flickery mode of the open channel state. Bupivacaine (300 µM) can also block whole-cell K+ currents (~45% blockage) in which, under our working conditions, BKCa is the main component. This study presents a new inhibitory effect of bupivacaine on an ion channel involved in different cell functions. Hence, the inhibitory effect of bupivacaine on BKCa channel activity could affect different physiological functions where these channels are involved. Since bupivacaine is commonly used during labor and delivery, its effects on umbilical arteries, where this channel is highly expressed, should be taken into account.

Keywords: BKCa channels, bupivacaine, human umbilical artery, patch clamp, native vascular smooth muscle

Introduction

Bupivacaine is a local anesthetic compound belonging to the amino amide group. Its anesthetic effect is commonly related to its inhibitory effect on voltage-gated sodium channels, which are blocked in the inactivated state.1,2 However, several studies have shown that this drug can also inhibit K+ channels by a different blocking mechanism. Voltage dependent K+ channels, such as Kv1.1, KCNQ2/Q3 and HERG,3 KATP channels and K2P channels are blocked by bupivacaine in different types of cells.4,5 In the cases where the inhibitory mechanism of K+ channels was investigated, bupivacaine produced a characteristic open channel block.6 The blocking of K+ channels could explain the observed effects of bupivacaine on blood vessels. In particular, bupivacaine produced contraction of rat muscle arterioles7 and of isolated human umbilical artery (HUA) rings.8,9 Additionally, Rossner et al.10 demonstrated that bupivacaine depolarized and increased intracellular Ca2+ of cultured smooth muscle cells obtained from HUA.

Up to now, there are no reports of bupivacaine effects on large conductance voltage- and Ca2+- activated K+ channels (BKCa). This channel is highly expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells and is functionally relevant being involved in the control of contractile properties in most blood vessels. In this study we demonstrate that bupivacaine can inhibit BKCa in vascular smooth muscle cells isolated from HUA. Our results show that bupivacaine blocks BKCa channel by inducing a reduction of its conductance, and a flickery mode of the open channel state. These results show a new effect of bupivacaine on a kind of channel highly expressed in HUA smooth muscle cells. Since umbilical arteries are important for the regulation of feto-placental blood flow, the demonstration that bupivacaine affects K+ channels in this human artery is physiologically relevant.

Results

The BKCa channel is one of the K+ channels frequently observed in inside-out patches obtained from human umbilical artery smooth muscle cells, as we described in a previous study.11Figure S1shows typical results which characterize this channel: increase of open probability (NPo) by augmenting free-Ca2+ concentration to 1.2 µM (Fig. S1A), high selectivity to K+ (PK/Pcholine > 15.77 and PK/PCs > 15.77) (Fig. S1B), voltage- and Ca2+-dependence of NPo (Fig. S1C), a single channel conductance of 234 ± 63 pS (Fig. S1D), and complete blockage by 500 nM paxilline (a selective blocker of BKCa channels) (Fig. S1E).

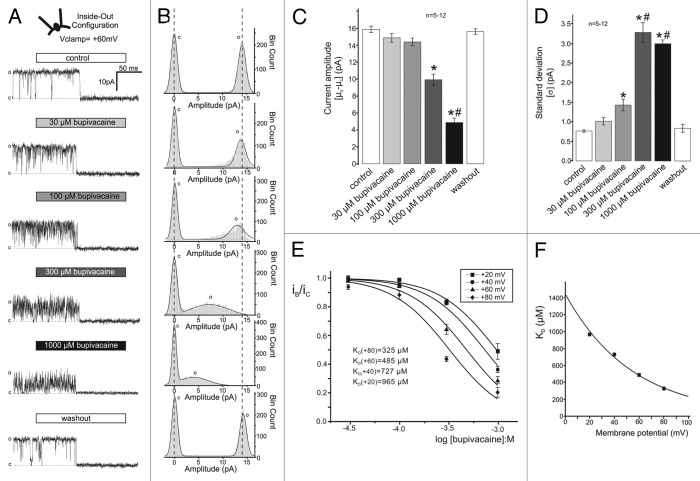

In presence of 1.2 µM Ca2+, where the BKCa channel has a high level of activity, bupivacaine (300 µM) produced a decrease in the amplitude of single-channel current and a flickery mode of the open channel state (Fig. S2). To further study the dose-dependence of the blocking effect of this local anesthetic we recorded the channel activity at +60 mV using a solution with low Ca2+ concentration in contact with the intracellular face of the membrane patch, so the channel displayed an adequate (not too high) level of activity. Figure 1A shows typical recordings with a single channel opening obtained in control condition, in the presence of 30, 100, 300 and 1000 µM of bupivacaine in the BS, and after drug washout. It is possible to observe that bupivacaine, in a concentration-dependent manner, produced a reduction of single-channel BKCa current amplitude and induced a clear flickery mode of the open channel state observed as an increase in the noise of the open channel level. To quantify the reduction in current amplitude we obtained the mean amplitude of the control and of the flickery-blocked channel from the all-point histogram distributions from 250 ms of a single channel recording as described in Methods (Fig. 1B). The histograms were fitted with a Gaussian function with two components obtaining the mean current amplitudes of the open and closed state (µo and µc, respectively), together with the standard deviation (σο) of the open peak, which can be taken as a measure of bupivacaine-induced current flicker. Mean values for single channel current amplitude (µ = µo-µc) and σo as function of bupivacaine concentration are depicted in Figure 1C and 1D, where it can be seen that as bupivacaine concentration rose, the current amplitude (µ) significantly diminished, while the noise (σο) increased. These effects were completely reversible after washout (Fig. 1C, D). The effect of bupivacaine was quick, both in its onset and in the reversal of its block after washout. After 30 sec of perfusion bupivacaine effect was already stable, while it disappeared completely after 1 min of washout. The reduction effect in the single channel open current amplitude as a function of time is shown in Figure S3.

Figure 1. Concentration- and voltage-dependent block of BKCa channel produced by bupivacaine. (A) Typical recordings of a single channel open event in an IO patch clamped at +60 mV. The panels show the effects of increasing concentrations of bupivacaine on BKCa channel open state. All records come from the same patch and represent 250 ms of channel recording chosen so that the amounts of time spent in the open and closed states were approximately equal. (B) All-point current amplitude histograms (0.2 pA bin width) corresponding to the recordings shown in A. The closed and open levels are indicated as C and O, respectively. (C) Mean values of open channel current amplitude (µo-µc) obtained from the fitting of 5–12 sets of histograms equivalent to those shown in B (each set comes from a different patch). The symbol * and the symbol # indicate statistically significant difference vs. control conditions and vs. 300 µM bupivacaine, respectively, by ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak test (p < 0.05). (D) Mean values of open channel current amplitude standard deviation (σo) obtained from the fitting of the same sets of histograms as in C. The symbol * and the symbol # indicate statistically significant difference vs. control conditions and vs. 100 µM bupivacaine, respectively, by ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak test (p < 0.05). (E) Blocked current values (iB) normalized to the current without block (ic) plotted vs. the logarithm of bupivacaine concentration for 3–9 IO patches clamped at different membrane potentials. The data were well fitted with a sigmoid function (see Results) from which the bupivacaine dissociation constant from the channel (KD) for each membrane potential can be obtained. (F) Plot of the KD values calculated in E as a function of the membrane potential. This relationship was well-fitted by an exponential decay function (see Results) from which one can obtain the location of the bupivacaine blocking site in the channel (δ) in terms of the fraction of the electrical field (the electrical distance) measured from the inside of the membrane.

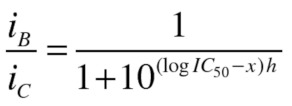

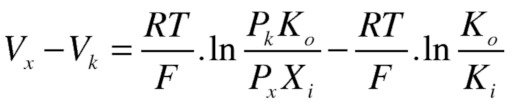

To explore the voltage-dependence of bupivacaine BKCa channel block, the mean amplitude of BKCa single-channel currents were measured at each bupivacaine concentration and at different membrane potentials. The blocked current values (iB) were normalized to the current without block (ic) and this relationship (iB/ic) plotted vs. the logarithm of bupivacaine concentration (Fig. 1E); the resulting data points were fitted with the following equation:

|

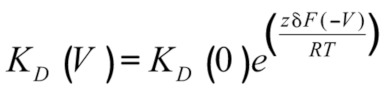

where x is the logarithm of bupivacaine concentration and h is the Hill slope.12,13 From this equation, one can obtain the drug dissociation constant (KD) which represents the bupivacaine concentration that produces 50% current inhibition (IC50) at each membrane potential. The KD calculated for different membrane potentials were statistically different and Figure 1F shows these values plotted as a function of the membrane potential. This relationship was well-fitted by an exponential decay function:12,13

|

where KD (0) is the KD value at 0 mV, z is the valence of the blocker (+1 in this case), V is the voltage across the membrane, δ is the location of the blocking site in terms of the fraction of the electrical field (the electrical distance) measured from the inside of the membrane, and RT/f = 25.3 mV at 22°C. A KD(0) of 1444 µM and a δ of 0.46 were obtained from the best fit to the graph shown in Figure 1F. Together, these results suggest that the blocking effect of bupivacaine is voltage dependent, that depolarization increases the drug affinity, and that the binding site for bupivacaine is located at ~46% of the way along the membrane field.

Another parameter that could have been analyzed was the NPo value of BKCa channel as a function of bupivacaine concentration. However, because of bupivacaine-induced flickery mode of block, it was not possible to measure it precisely. The NPo value obtained from the area of the all-point histograms would have underestimated this parameter, while the value obtained from the idealized recording from single channel events detection by the half-amplitude threshold criterion would have overestimated it.

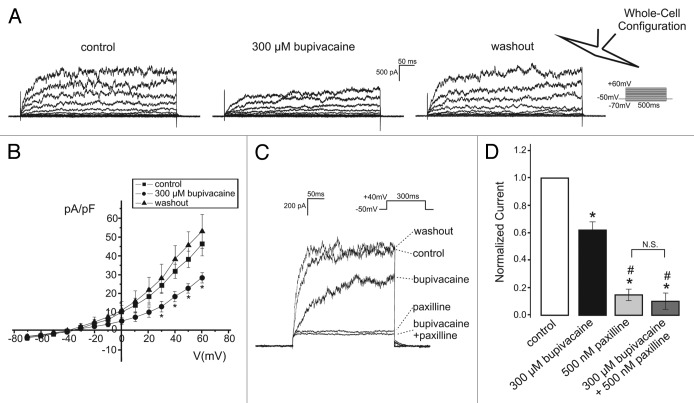

In order to test if the flickery block mode and the reduction in single channel current amplitude was enough to induce inhibition of macroscopic current we performed a series of experiments where the current was recorded in whole-cell configuration. The effect of bupivacaine was tested on a family of currents evoked by 500 ms voltage steps between -70 and +60 mV from a holding potential of -50 mV. In our experimental conditions (see whole-solutions in Methods), about 85% of the total control current was carried by BKCa channels, as judged by sensitivity to 500 nM paxilline (Fig. 2C and D). Increasing the paxilline concentration did not augment the blocking effect (data not shown). The macroscopic current was partially blocked by superfusion with 300 µM bupivacaine (Fig. 2A) and this effect was completely reversible (Fig. 2 A–C) after 3 min of washing. Figure 2B shows the mean current-voltage relationships (I-V) of the steady-state current in control conditions, after the stable effect of bupivacaine and after washout. Subsequent to the current recovery, the same cell was superfused with a solution containing 500 nM paxilline and, after stabilization, paxilline plus bupivacaine to compare the effects of both drugs. While paxilline blocked whole-cell current almost completely, bupivacaine inhibited 44% of control current, and the effect of the two drugs applied together was not different from the effect of paxilline alone (Fig. 2C and D).

Figure 2. Bupivacaine inhibits a BKCa component of whole-cell K+ currents in HUA smooth muscle cells. (A) Superimposed representative recordings of whole-cell currents obtained by applying 10 mV voltage steps from -70 mV to +60 mV from a holding potential of -50 mV in control conditions (left panel), after 300 µM bupivacaine (middle panel) and after bupivacaine washout (right panel). (B) Mean IV curves obtained in the same conditions as in A (n = 10). The symbol * indicates statistically significant difference from control (Student’s t test, p < 0.05). (C) superimposed representative recordings of currents evoked by single steps to +40 mV from a holding potential of -50 mV obtained in a cell which was exposed sequentially to control conditions, then to 300 µM bupivacaine, to washout of bupivacaine followed by 500 nM paxilline and finally, 300 µM bupivacaine plus 500 nM paxilline. (D) Mean ± SEM values for the protocol shown in C (n = 3–10). The symbol * and the symbol # indicate statistically significant difference vs. control conditions and vs. 300 µM bupivacaine, respectively, by ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak test (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The results presented in this study show that the local anesthetic bupivacaine inhibits BKCa channels in HUA smooth muscle cells. This was demonstrated both at the single-channel level, as well as on whole-cell K+ currents. Up to now, there have been no reports in the literature about the effects of bupivacaine on BKCa channels. This channel is highly expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells and is functionally relevant, being involved in the control of contractile properties in most blood vessels.

In the single-channel configuration the ionic selectivity analysis, the voltage and paxilline sensitivity, the conductance value, and the increase in open probability when the intracellular Ca2+ concentration was elevated, all indicate that the channel blocked by bupivacaine is the BKCa channel. This drug is able to block the BKCa channel both during its activation by low micromolar free Ca2+ and in the presence of a modest intracellular Ca2+ concentration, where the open probability was lower. In this latter condition, the analysis of the blocking effect was investigated in more detail. In IO patches, bupivacaine quickly induced a flickering open channel behavior observed as an increase in the noise of the open channel level (estimated by σο) and a clear and significant concentration- dependent reduction of single-channel current amplitude. All these effects were reversible following washout of bupivacaine from the bath. We also observed that bupivacaine blocking effect was voltage-dependent, since the drug KD changed e-fold per 54.7 mV (decreasing with depolarization), indicating that the drug binding is affected by the membrane electrical field, probably by facilitating its entrance into the pore region of the channel. The calculated value of the electrical distance of block suggests that the binding site for this drug is located at ~46% of the way along the membrane field, measured from the inside of the membrane. These results can be compared with those reported for intracellular effects of other BKCa channel blockers, such as TEA and Cs+14

Bupivacaine can also block whole-cell K+ currents in which, under our working conditions, BKCa is a main component. Time-dependent block by bupivacaine has been reported for some subtypes of KV channels, suggesting that bupivacaine has a selective affinity for the open channel state.6 In our case, 300 µM of bupivacaine did not induce any time-dependent block during the depolarizing step, as the current in presence of bupivacaine had lower amplitude than in control conditions but maintained the kinetics of activation for each voltage pulse. Since the combination of bupivacaine plus paxilline did not produce an additive block, we can conclude that 300 µM bupivacaine partially blocks the BKCa macroscopic current in accordance with the single-channel results. The effect of bupivacaine on this channel shows that this drug presents different blocking mechanisms depending on the type of ionic channel involved; e.g., Nilsson et al.6 reported an open channel block mode for two types of KV channels.

Regarding the drug accessibility to the channel, the analysis of unitary currents suggests that the site of action is located on the internal side of the channel. Moreover, as bupivacaine is a molecule that can readily cross the plasma membrane, one could expect it to be effective on BKCa channels when applied on either side of the membrane. This idea is consistent with our data obtained from whole-cell and inside-out patch recording configurations, as we observed that bupivacaine is able to readily block the channel when applied to either the external or internal side of the plasma membrane.

BKCa channels are widely expressed and involved in different and relevant physiological functions in different types of cells. Activation of these channels induced by an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration produces hyperpolarization of the cell membrane, thereby diminishing membrane excitability. This is important for the regulation of different cell mechanisms, like contractility of smooth muscle cells15 or action potential frequency, duration, and inter-burst intervals in neurons.16 So, the inhibitory effect of bupivacaine on BKCa channel activity could affect different physiological functions. In particular, our results give an explanation for the previously described bupivacaine effect on HUA rings, where Rossner et al.10 observed that this drug produced depolarization and contraction of this vessel.

In obstetrics bupivacaine is commonly used during labor and delivery. Placental transfer of this drug has been confirmed by the presence of measurable quantities of bupivacaine in umbilical cord blood.17 Although there are several studies that indicate that bupivacaine use is safe for the mother and fetus,18-20 it has been shown in rats that a considerable amount of bupivacaine is taken up by both sides of the placenta, as well as the amnion and myometrium.21 Moreover, Monuszko et al.,8 suggest that unintentional intravascular injection of bupivacaine intended to be epidural may lead to plasma concentrations sufficiently high to cause umbilical vessel contraction with adverse fetal effects. Since BKCa channels are important for the regulation of human umbilical artery tone, we think that the fact that bupivacaine blocks these channels in this human vessel should be taken into account when using this anesthetic.

In summary, this study presents a new inhibitory effect of bupivacaine on a K+ channel involved in several cell functions and particularly, highly expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells.

Methods

Umbilical cords were obtained from normal, term pregnancies after vaginal and cesarean deliveries, placed in transport solution of the following composition (in mM): 130 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.17 KH2PO4, 1.16 MgSO4, 24 NaCO3H, 2.5 CaCl2, pH 7.4 at 4°C and immediately taken to our laboratory where they were stored at 4°C and used within the next 24 hs. All procedures are in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki (1975).

Cell isolation procedure for patch-clamp experiments

The HUA were dissected from the Wharton’s jelly just before the cell isolation procedure. HUA smooth muscle cells were obtained by a method based on the one described by Klockner et al.22 and later modified in our laboratory in order to diminish the enzyme content in the dissociation medium (DM).23 Briefly, a segment of HUA was cleaned of any residual connective tissue, cut in small strips, and placed for 15 min in a DM containing (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KH2PO4, 5 MgCl2, 6 glucose, 5 HEPES; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. The strips were then placed in DM with 2 mg/ml collagenase type I during 25 min, with gentle agitation, at 35°C. After the incubation period the strips were washed with DM and single HUA smooth muscle cells were obtained by a gentle dispersion of the treated tissue using a Pasteur pipette. The remaining tissue and the supernatant containing isolated cells were stored at room temperature (~22°C) until used. HUA smooth muscle cells were allowed to settle onto the coverglass bottom of a 3 ml experimental chamber.

Patch-clamp current recordings

The isolated HUA smooth muscle cells were observed with a mechanically stabilized, inverted microscope (Telaval 3, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a 40X objective lens. Application of test solutions was performed through a multibarreled pipette positioned close to the cell investigated. After each experiment on a single cell, the experimental chamber was replaced by another one containing a new sample of cells. Only well-relaxed, spindle-shaped smooth muscle cells were used for electrophysiological recordings. Data were collected within 4–6 h after cell isolation. All experiments were performed at room temperature (~22°C).

The standard tight-seal inside-out and whole-cell configurations of the patch-clamp technique24 were used to record single-channel and macroscopic currents respectively. Glass pipettes were drawn from WPI PG52165–4 glass on a two-stage vertical micropipette puller (PP-83, Narishige Scientific Instrument Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) and pipette resistance ranged from 2 to 4 MΩ.

Single-channel recordings

Single-channel currents were recorded in the inside-out configuration (IO), filtered with a 4-pole lowpass Bessel filter at 2 kHz (Axopatch 200A amplifier, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and digitized (Digidata 1200 Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) at 16 kHz. Voltage-clamp 30–60 sec recordings were obtained at different membrane potentials to obtain the single channel current amplitude and the open probability (NPo) of the channels. The control pipette solution (PS) used for single-channel recordings contained (in mM): 140 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 6 glucose, 1 CaCl2, 5 4-aminopirydine (4-AP), pH adjusted to 7.4 with HCl. 4-AP was added to block Kv channels present is HUA smooth muscle cells.11 The bath solution (BS) in contact with the cytosolic face of the membrane contained (in mM): 140 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 6 Glucose, 1 EGTA, pH adjusted to 7.4 with KOH. Different amounts of CaCl2 were added to the BS to obtain the desired free Ca2+ concentrations tested (1.2 µM or 3 nM; calculated using Maxchelator software from Stanford University: maxchelator.stanford.edu).

In order to obtain the relative permeability of the channel to different cations, the BS was modified for some of the experiments: KCl was totally replaced with either 140 mM of CsCl or with 140 mM choline chloride. In these cases, the free Ca2+ concentration was 1.2 µM, which provides adequate activity of BKCa channel over a wide range of membrane potentials. Different concentrations of bupivacaine (30, 100, 300 and 1000 µM) were added to the BS to study voltage- and concentration-dependent effects of this drug on BKCa channels.

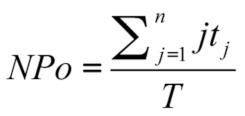

Single-channel currents were analyzed with the pCLAMP software (version 9.2). Current amplitude histograms were plotted for each membrane potential tested to obtain a current-voltage relationship for the study of single channel properties. Open probability is expressed as NPo, where N is the number of single channels present in each patch. NPo values were calculated using the following expression:

|

where T is the duration of recording and tj is the time spent with j = 1,2,3,…n channels open. The parameters were obtained from single channel events detection by the half-amplitude threshold criterion. Stationary conditions of single channel recordings were controlled by plotting the NPo values calculated for intervals of 5 sec during the 30 sec of recording as function of time. The NPo values in control conditions were stable during the recording time in all studied patches.

The K+ selectivity of the channel was tested by studying the relative permeabilities of Cs+ and choline to K+ under conditions of zero net current. These were estimated by analyzing the shift in the reversal potential under biionic conditions.25 The relationship between the permeability ratio and the shift in reversal potential was obtained from the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation.26,27 If K+ in contact with the inner surface of the membrane is replaced equimolarly by X+ while not altering the K+ concentration in contact with the outward membrane surface, the shift in reversal potential is given by:

|

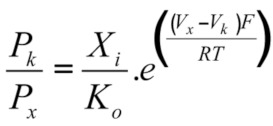

where Vx and VK are the reversal potentials with X+ and K+ at the inner membrane surface, respectively ; Px and Pk are the permeabilities of the channel to X+ and K+, respectively; Ko, Ki;, and Xi are the concentrations of the indicated ions; and F/RT = 0.0394 mV−1 at 22°C. The permeability ratio of X+ to K+ is then obtained by rearrangement:

|

For the selectivity experiments presented in this paper, Ko and Ki were both 140 mM, so that VK = 0. Data for determining reversal potentials were obtained by plots of single channel current amplitude vs. membrane potential, which were nonlinear for the ions studied.28 In the experiments where reversal of the currents was not observed at the range of membrane potential tested, “reversal potentials” are reported as greater than the highest membrane potential tested.

Because bupivacaine decreased single channel current amplitude and increased the open channel noise (see results), the voltage- and dose-dependent blocking effect of bupivacaine on BKCa channel was analyzed on all-points amplitude histograms obtained from portions of single channel recordings of 250 ms of length chosen so the open channel time was the same as the closed channel time. A nonlinear Levenberg-Marquardt least squares curve fitting procedure was used for fitting Gaussian curves. Fitting parameters, mean (µ) and standard deviation (σ), were used to analyze current amplitude (µopen-µclosed) and open channel noise (σopen) in absence and presence of 30, 100, 300 and 1000 µM bupivacaine and after washout. Analysis of dose-response relationships at different membrane potentials was performed using the sigmoidal dose-response (variable slope) curve fitting on GraphPad Prism 4.0. Voltage dependence of KD was fitted with a single exponential decay (Origin Pro 8 Software), in order to obtain δ (see Results for more details).

Whole-cell recordings

Whole-cell currents were filtered with a 4-pole lowpass Bessel filter (Axopatch 200A amplifier) at 2 kHz and digitized (Digidata 1200 Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at a sample frequency of 20 kHz. The experimental recordings were stored on a computer hard disk for later analysis. The pipette solution contained (in mM): 130 KCl, 10 HEPES, 0.1 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 5 ATP-Na2; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with KOH giving a calculated free Ca2+ concentration of 0.7 µM. The bath solution contained (in mM): 130 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 2.5 CaCl2, 5 HEPES, 6 glucose, 5 4-AP; pH was adjusted to 7.4 with HCl. Under these conditions KATP and Kv channels contribution to the macroscopic current are inhibited by ATP-Na2 and 4-AP, respectively,11 while the intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ensures a significant BKCa-carried current component. Whole-cell current stability was monitored by applying successive 500 ms voltage steps (from a holding potential of -50 mV to a test potential of +40 mV) discarding those cells in which the current amplitude did not remain constant in time. After the current was stable, this same voltage-clamp step protocol was applied in control or in the different experimental conditions (300 µM bupivacaine, 500 nM paxilline, or bupivacaine and paxilline together). A family of voltage steps between -70 and +60 mV from a holding potential of -50 mV were also applied in each stable condition for further current-voltage relationship (I-V) analysis. Cell membrane capacitance was calculated from the capacity current obtained from the recording of a single 10 mV hyperpolarizing step.

Drugs and reagents used

Bupivacaine hydrochloride, paxilline, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), EGTA, Na2ATP, and all the enzymes used for cell isolation were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. All other reagents were of analytical grade and purchased from local vendors. Bupivacaine was dissolved in distilled water. Paxilline was dissolved in DMSO. Fresh aliquots of stock solutions of paxilline and bupivacaine were added to the bath solution on the day of the experiment. When comparing with paxilline effects, an appropriate amount of DMSO was added to all solutions without paxilline.

Statistics

The results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Paired or unpaired Student t-tests were used to compare two groups. For the comparison of multiple groups, ANOVA followed by an appropriate test was used. In all cases, a P value lower than 0.05 was considered for establishing statistically significant differences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge excellent technical assistance by Mr. Luciano Piccinini and Mr. Matías Vilche. They also wish to thank Mr. Pablo Urdampilleta, Ms. Anabel Poch and the staff of the Instituto Central de Medicina for collection of umbilical cords. This study was financially supported by the grant PIP 0202 from the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- HUA

human umbilical artery

- BKCa

large conductance voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channels

- Kv

voltage-operated K+ channels

- IO

inside-out configuration

- BS

bath solution

- DM

dissociation medium

- NPo

open probability

- 4-AP

4-aminopyridine

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether) N,N,N’,N’,-tetraacetic acid

- PS

pipette solution

- BS

bath solution

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material may be found here: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/channels/article/20362/

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/channels/article/20362

References

- 1.Hille B. Local anesthetics: hydrophilic and hydrophobic pathways for the drug-receptor reaction. J Gen Physiol. 1977;69:497–515. doi: 10.1085/jgp.69.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hondeghem LM, Katzung BG. Time- and voltage-dependent interactions of antiarrhythmic drugs with cardiac sodium channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;472:373–98. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(77)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sintra Grilo L, Carrupt PA, Abriel H, Daina A. Block of the hERG channel by bupivacaine: Electrophysiological and modeling insights towards stereochemical optimization. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46:3486–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olschewski A, Olschewski H, Bräu ME, Hempelmann G, Vogel W, Safronov BV. Effect of bupivacaine on ATP-dependent potassium channels in rat cardiomyocytes. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:435–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kindler CH, Yost CS, Gray AT. Local anesthetic inhibition of baseline potassium channels with two pore domains in tandem. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1092–102. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199904000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nilsson J, Madeja M, Elinder F, Arhem P. Bupivacaine blocks N-type inactivating Kv channels in the open state: no allosteric effect on inactivation kinetics. Biophys J. 2008;95:5138–52. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johns RA, Seyde WC, DiFazio CA, Longnecker DE. Dose-dependent effects of bupivacaine on rat muscle arterioles. Anesthesiology. 1986;65:186–91. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198608000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monuszko E, Halevy S, Freese K, Liu-Barnett M, Altura B. Vasoactive actions of local anaesthetics on human isolated umbilical veins and arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;97:319–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuvemo T, Willdeck-Lund G. Smooth muscle effects of lidocaine, prilocaine, bupivacaine and etiodocaine on the human umbilical artery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1982;26:104–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1982.tb01734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossner KL, Natke E, Liu-Barnett M, Freese KJ. A proposed mechanism of bupivacaine-induced contraction of human umbilical artery smooth muscle cells. Int J Obstet Anesth. 1999;8:24–9. doi: 10.1016/S0959-289X(99)80148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milesi V, Raingo J, Rebolledo A, Grassi de Gende AO. Potassium channels in human umbilical artery cells. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2003;10:339–46. doi: 10.1016/S1071-5576(03)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodhull AM. Ionic blockage of sodium channels in nerve. J Gen Physiol. 1973;61:687–708. doi: 10.1085/jgp.61.6.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanchez DY, Blatz AL. Block of neuronal fast chloride channels by internal tetraethylammonium ions. J Gen Physiol. 1994;104:173–90. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yellen G. Ionic permeation and blockade in Ca2+-activated K+ channels of bovine chromaffin cells. J Gen Physiol. 1984;84:157–86. doi: 10.1085/jgp.84.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C799–822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sah P, Davies P. Calcium-activated potassium currents in mammalian neurons. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000;27:657–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ralston DH, Shnider SM. The fetal and neonatal effects of regional anesthesia in obstetrics. Anesthesiology. 1978;48:34–64. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197801000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scanlon JW, Ostheimer GW, Lurie AO, Brown wu JR, Weiss JB, Alper MH. Neurobehavioral responses and drugs in newborns after epidural anesthesia with bupivacaine. Anesthesiology. 1976;45:400–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197610000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abboud TK, Khoo SS, Miller F, Doan T, Henriksen EH. Maternal, fetal, and neonatal responses after epidural anesthesia with bupivacaine, 2-chloroprocaine, or lidocaine. Anesth Analg. 1982;61:638–44. doi: 10.1213/00000539-198208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alahuhta S, Räsänen J, Jouppila P, Kangas-Saarela T, Jouppila R, Westerling P, et al. The effects of epidural ropivacaine and bupivacaine for cesarean section on uteroplacental and fetal circulation. Anesthesiology. 1995;83:23–32. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199507000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morishima HO, Ishizaki A, Zhang Y, Whittington RA, Suckow RF, Cooper TB. Disposition of bupivacaine and its metabolites in the maternal, placental, and fetal compartments in rats. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1069–74. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klöckner U. Intracellular calcium ions activate a low-conductance chloride channel in smooth-muscle cells isolated from human mesenteric artery. Pflugers Arch. 1993;424:231–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00384347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raingo J, Rebolledo A, Iveli F, Grassi de Gende AO, Milesi V. Non-selective cationic channels (NSCC) in smooth muscle cells from human umbilical arteries. Placenta. 2004;25:723–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hille B. Potassium channels in myelinated nerve. Selective permeability to small cations. J Gen Physiol. 1973;61:669–86. doi: 10.1085/jgp.61.6.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldman DE. Potential, impedance, and rectification in membranes. J Gen Physiol. 1943;27:37–60. doi: 10.1085/jgp.27.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodgkin AL, Katz B. The effect of sodium ions on the electrical activity of giant axon of the squid. J Physiol. 1949;108:37–77. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blatz AL, Magleby KL. Ion conductance and selectivity of single calcium-activated potassium channels in cultured rat muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1984;84:1–23. doi: 10.1085/jgp.84.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.