Background: Amino sugar utilization pathways are highly variable among different bacteria.

Results: The N-acetylgalactosamine utilization pathway and regulon were reconstructed in the genomes of diverse Proteobacteria.

Conclusion: In vitro pathway reconstitution confirmed a novel variant of the N-acetylgalactosamine utilization pathway in the Shewanella lineage.

Significance: Novel enzymatic activities required for amino sugar utilization were characterized.

Keywords: Bacteria, Carbohydrate Metabolism, Enzymes, Genomics, Transcription Regulation, Transporters, N-Acetylgalactosamine, Shewanella

Abstract

We used a comparative genomics approach to reconstruct the N-acetyl-d-galactosamine (GalNAc) and galactosamine (GalN) utilization pathways and transcriptional regulons in Proteobacteria. The reconstructed GalNAc/GalN utilization pathways include multiple novel genes with specific functional roles. Most of the pathway variations were attributed to the amino sugar transport, phosphorylation, and deacetylation steps, whereas the downstream catabolic enzymes in the pathway were largely conserved. The predicted GalNAc kinase AgaK, the novel variant of GalNAc-6-phosphate deacetylase AgaAII and the GalN-6-phosphate deaminase AgaS from Shewanella sp. ANA-3 were validated in vitro using individual enzymatic assays and reconstitution of the three-step pathway. By using genetic techniques, we confirmed that AgaS but not AgaI functions as the main GalN-6-P deaminase in the GalNAc/GalN utilization pathway in Escherichia coli. Regulons controlled by AgaR repressors were reconstructed by bioinformatics in most proteobacterial genomes encoding GalNAc pathways. Candidate AgaR-binding motifs share a common sequence with consensus CTTTC that was found in multiple copies and arrangements in regulatory regions of aga genes. This study provides comprehensive insights into the common and distinctive features of the GalNAc/GalN catabolism and its regulation in diverse Proteobacteria.

Introduction

Amino sugars N-acetyl-d-galactosamine (GalNAc)4 and d-galactosamine (GalN) constitute various cell structures in all biological domains. In bacteria, GalNAc is a common component of the cell wall (1), being found in lipopolysaccharides (2). In human, GalNAc links carbohydrate chains in mucins (3). The amino sugars were also commonly found in the carbohydrate chains of glycosylated proteins, both in prokaryotes and eukaryotes (4–7).

GalNAc and GalN amino sugars can support the growth of Escherichia coli by serving as carbon and nitrogen sources (8). Genes involved in GalNAc/GalN utilization were initially identified by in silico analysis of the E. coli K-12 genome (8). The proposed catabolic pathway involves the transport and subsequent phosphorylation of GalNAc/GalN substrates, the deacetylation of GalNAc-6-P, the deamination/isomerization of GalN-6-P, the phosphorylation of Tag-6-P, and the cleavage of Tag-1,6-PP to produce glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and glycerone phosphate. Two PTS systems encoded by agaBCD and agaVWEF genes were then confirmed to mediate transport and phosphorylation of GalN and GalNAc, respectively (9). Two putative enzymes encoded by aga gene loci, AgaA and AgaI, were found to be homologous, respectively, to the GlcNAc-6-P deacetylase NagA and the GlcN-6-P deaminase NagB from E. coli (8). Based on this observation, Reizer et al. have proposed that AgaA and AgaI function as the GalNAc-6-P deacetylase and the GalN-6-P deaminase, respectively, but neither of these enzymes was then experimentally validated. The identity of the Tag-6-P kinase is yet unknown; however, two alternative hypotheses were proposed: (i) the fructose-6-phosphate kinase PfkA is also responsible for Tag-6-P phosphorylation (10); and (ii) the putative protein AgaZ encoded in the aga gene locus functions as Tag-6-P kinase (8). The final step of the GalNAc pathway is catalyzed by the Tag-1,6-PP aldolase AgaY that belongs to the class II aldolases (11). The molecular function of the AgaS enzyme encoded in the aga gene cluster has not yet been investigated.

The aga genes in E. coli are transcriptionally regulated by the AgaR repressor from the DeoR family of transcriptional factors (12). The AgaR protein recognizes specific sequences with consensus WRMMTTTCRTTTYRTTTYNYTTKK (where W is A or T, Y is C or T, R is A or G, M is A or C, and K is G or T) located in the promoter regions of the agaZ, agaS, and agaR genes. All three promoters had elevated activity in the presence of GalNAc or GalN in the medium, and this induction was dependent on the AgaR repressor (12). The effector for AgaR was not identified; however, it was proposed that phosphorylated intermediates of the GalNAc/GalN catabolic pathway, GalNAc-6-P and/or GalN-6-P, can serve as molecular inducers.

Recently, a genomic reconstruction of sugar utilization pathways was performed for aquatic γ-Proteobacteria from the Shewanella genus, resulting in identification of a novel variant of the GalNAc catabolic pathway in four Shewanella strains (13). The reconstructed catabolic pathway in Shewanella spp. involves two E. coli-like enzymes (the predicted AgaS deaminase and AgaZ kinase) and four novel functional assignments, including a nonorthologous GalNAc-6-P deacetylase (AgaAII), a predicted GalNAc kinase (AgaK), and an inner membrane GalNAc permease (AgaP) (Fig. 1). Thus, it was proposed that the GalNAc-specific PTS in E. coli is replaced by GalNAc permease and kinase in Shewanella. Experimental testing of growth phenotypes confirmed the ability of Shewanella amazonensis SB2B, and Shewanella MR-4, MR-7, and ANA-3 strains to grow on GalNAc as a sole carbon and energy source (13).

FIGURE 1.

Reconstruction of GalNAc utilization pathways in Proteobacteria. Different pathway variants in E. coli and Shewanella are highlighted by yellow and green background arrows, respectively. Multiple nonorthologous variants of proteins for several functional roles are listed in the same box and marked by uppercase Roman numerals.

In this work, we combined the bioinformatics reconstruction of GalNAc utilization pathways and AgaR transcriptional regulons in the genomes of Proteobacteria with the detailed characterizations of three novel enzymes from the GalNAc catabolic pathway in Shewanella sp. ANA-3. Activities of the novel GalNAc kinase AgaK and GalNAc-6-P deacetylase AgaAII were validated by in vitro enzymatic assays with purified enzymes. We assigned the role of GalN-6-P isomerase to AgaS protein and confirmed its functionality in both Shewanella and E. coli. Finally, we showed that AgaS functions as a main GalN-6-P isomerase in the GalNAc pathway of E. coli, whereas the previously assigned AgaI enzyme is not essential for the GalNAc catabolism. Functional diversity of GalNAc catabolic pathways in various taxonomic groups of Proteobacteria is discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bioinformatics Approaches and Tools

Genome sequences were downloaded from the MicrobesOnline genomic data base (14). Identification of orthologs was performed using BLAST searches in the “nr” data base (15) and confirmed by construction of protein phylogenetic trees. For functional protein annotation, distant homology to characterized proteins was determined using BLAST searches in the Swissprot/Uniprot protein data base. Genomic neighborhood analysis was performed using the MicrobesOnline and SEED Web resources (14, 16). The GalNAc utilization subsystem curation and analysis were conducted using the SEED platform (16). Known specificities of sugar transporters and glycoside hydrolases were extracted from the TCDB (17) and CAZy (18) databases, respectively. Protein domains were determined by protein similarity search tools in the Pfam data base (19). Multiple sequence alignments were constructed by MUSCLE (20). Phylogenetic trees were built using a maximum likelihood algorithm implemented in the proml tool from the PHYLIP package (21). Trees were visualized using Dendroscope (22). Signal peptide sequences were determined using the SignalP server (23).

For genomic reconstruction of AgaR regulons, we used the comparative genomics approach based on identification of candidate regulator-binding sites in closely related bacterial genomes (for review, see Ref. 24). First, we revealed orthologs of the AgaR regulator from E. coli and analyzed the genomic context of agaR genes to reveal their co-localization with other aga genes. A representative subset of species from seven taxonomic groups of Proteobacteria that possess the AgaR regulators and GalNAc utilization pathway genes was selected for comparative genomic analysis (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis of AgaR regulators revealed five major groups of orthologs. For each group of AgaR proteins on the phylogenetic tree, we identified a putative AgaR-binding motif using the combination of the phylogenetic footprinting approach and the motif-discovery tools implemented in the RegPredict Web server (25). We collected training sets of orthologous upstream gene regions for each prospective AgaR-controlled operon that was determined via the genome context analysis of agaR genes. The identified conserved DNA motifs corresponding to the predicted AgaR-binding sites were scanned in the studied genomes using motif-specific positional weight matrices to determine additional candidate-binding sites using the Regpredict tool. The scores of sites were calculated as a sum of nucleotide weights for each position. Newly identified candidate sites were validated using multiple alignments of orthologous upstream regions to determine their sequence conservation. Sequence logos were built using the WebLogo package (26). Reconstructed regulons are represented in the RegPrecise data base (27).

TABLE 1.

Genomic distribution of components of the reconstructed GalNAc utilization pathways in Proteobacteria

| Lineage/Genome | Regulator AgaRa | Catabolic enzymesb |

Transportersb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AgaK | AgaA | AgaS | AgaZ | AgaY | Omp | AgaP | PTS | ||

| Enterobacteriales | |||||||||

| Escherichia coli str. C str. ATCC 8739 | i | I | + | + | I | I,IV | |||

| Citrobacter koseri ATCC BAA-895 | i | I | + | + | I | I | |||

| Enterobacter sp. 638 | i | + | + | I | I,IV | ||||

| Yersinia pestis KIM | ii | I | + | + | I | III | |||

| Serratia proteamaculans 568 | iv,iv | + | + | I | II | ||||

| Edwardsiella tarda EIB202 | ii,iv | I | + | + | I | II,III | |||

| Proteus mirabilis HI4320 | ii | I | + | + | I | III | |||

| Photorhabdus luminescens TTO1 | iv | + | + | I | II | ||||

| Vibrionales | |||||||||

| Vibrio vulnificus CMCP6 | v,v | I | + | + | I | I | |||

| Vibrio fischeri ES114 | ii | I | + | + | I | III | |||

| Vibrio angustum S14 | v,v | I | + | + | I | I | |||

| Photobacterium profundum SS9 | ii,v,v | I | + | + | I | I,III | |||

| Pasteurellales | |||||||||

| Haemophilus parasuis SH0165 | ii | + | II | V | |||||

| Alteromonadales | |||||||||

| Shewanella sp. ANA-3, MR-4, MR-7 | iii | I | II | + | + | + | I | ||

| Shewanella amazonensis SB2B | iii | I | II | + | + | + | I | ||

| Aeromonadales | |||||||||

| Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7966 | i | I | + | + | I | + | I | ||

| Xanthomonadales | |||||||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia K279a | iv | I | I | + | + | + | III | ||

| Caulobacterales | |||||||||

| Caulobacter sp. K31 | + | II | + | + | II | ||||

| Burkholderia | |||||||||

| Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315 | + | II | + | + | II | ||||

a Groups of regulators clustered into five clades on the AgaR phylogenetic tree and characterized by different DNA motifs are presented as lowercase roman numerals (see supplemental Fig. S1 for details).

b The presence of genes for the respective functional roles is shown by + or by uppercase Roman numerals, where each numeral denotes an individual functional variant that is nonorthologous to the others in the same column.

Strains and Growth Conditions

Shewanella sp. ANA-3 and E. coli ATCC 8739 strains were used in this study. The E. coli ATCC 8739 ΔagaS and ΔagaI are derivatives with in-frame deletions of the agaS gene (EcolC_0562) and the agaI gene (EcolC_0557), respectively. E. coli strains DH5α and BL21(DE3)pLysS (Invitrogen) were used for gene cloning and protein overexpression, respectively. The E. coli strains were routinely maintained and cultured on LB medium. Kanamycin (30 μg ml−1), spectinomycin (30 μg ml−1), and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (0.2 mm) were added as appropriate. For growth experiments and RNA isolations, Shewanella sp. ANA-3 and E. coli ATCC 8739 strains were grown in 50 ml of M1 (28) and M9 (29) minimal media, respectively, supplemented with 10 mm GalNAc or GlcNAc used as a sole carbon and energy source. Cell growth was monitored spectrophotometrically at 600 nm.

RNA Isolation and Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from Shewanella sp. ANA-3 cells harvested at a midexponential growth phase. Cells were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and ground into powder. RNA was isolated using TRIzolTM (Invitrogen) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Contaminant DNA was removed by DNase I (Takara) digestion, which was verified by performing the PCR under identical conditions without adding reverse transcriptase. cDNA was generated by reverse transcription reactions using random hexamers as primers, 1 μg of purified RNA, and RTase Moloney murine leukemia virus (RNase H−) reverse transcriptase (Takara). The cDNA was amplified using the Applied Biosystems 7300 real-time PCR system. The reaction mixture (20 μl) contained 50–100 ng of cDNA, 0.2 μm gene-specific primers (as shown in supplemental Table S1), and Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Bio-Rad). The PCR parameters were one cycle of 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 31 s. Melt curves were analyzed to ensure specificity of primer annealing and lack of primer secondary structures. Data analysis was performed with the 7300 system software (Bio-Rad) using 16 S rRNA for normalization. The expression level of each gene was presented as the average of six measurements from two biological replicates, with the corresponding S.D.

Genetic Manipulations

In-frame single-gene deletions of agaS and agaI in E. coli ATCC 8739 were achieved by replacing the target genes with a spectinomycin resistance cassette using the standard Lambda Red-mediated gene replacement method (30). The chromosomal deletions of the individual genes were confirmed by PCR. The primers for gene knock-out and PCR confirmation are shown in supplemental Table S1. For complementation analysis, the full-length coding regions of agaS and/or agaY (EcolC_0561) genes from E. coli ATCC 8739 were PCR-amplified using the primers shown in supplemental Table S1 and inserted downstream into the lac promoter in the pUC118 expression vector (Novagen). The resulting plasmids were then electroporated into the E. coli ATCC 8739 ΔagaS knock-out mutant. For protein overexpression and purification, the agaK (ShewANA3_2698), agaAII (ShewANA3_2697), and agaS (ShewANA3_2699) genes from Shewanella sp. ANA-3 were amplified by PCR using the primers shown in supplemental Table S1. The PCR products were cloned into the expression vector pET28a, and the resulting plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS.

Protein Overexpression and Purification

The recombinant Shewanella proteins AgaK, AgaAII, and AgaS were overexpressed as N-terminal fusions with a His6 tag in E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS. The cells were grown in LB medium to an A600 nm of 0.8 at 37 °C, induced by 0.2 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, and harvested after 12 h of shaking at 16 °C. Protein purification was performed using a rapid Ni-NTA-agarose minicolumn protocol as described previously (31). Briefly, harvested cells were resuspended in 20 mm HEPES buffer (pH 7) containing 100 mm NaCl, 0.03% Brij-35, 2 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Lysozyme was added to a concentration of 1 mg ml−1, and the cells were lysed by freezing-thawing followed by sonication. After centrifugation, the supernatant was loaded onto a Ni-NTA-agarose column (0.2 ml). After bound proteins were washed with the 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8) containing 1 m NaCl, 0.3% Brij-35, and 2 mm β-mercaptoethanol, they were eluted with 0.3 ml of the same buffer supplemented with 250 mm imidazole. The buffer was then changed to 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing 0.3 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, and 10% glycerol by using Bio-Spin columns (Bio-Rad). The purified proteins were run on a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel to monitor their size and purity.

In Vitro Enzymatic Assays

GalNAc kinase activity was assayed by coupling the formation of ADP to the oxidation of NADH to NAD+ via pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase. Briefly, 0.5 μg of purified enzyme was added to 200 μl of 50 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.5) containing 20 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, 2 mm phosphoenolpyruvate, 0.3 mm NADH, 4 units of pyruvate kinase, 4 units of lactate dehydrogenase, and 1 mm GalNAc (Sigma-Aldrich). The change in NADH absorbance was monitored at 340 nm at 30 °C by using a Beckman DU-800 spectrophotometer. To test substrate specificity of AgaK, GalNAc was replaced by 10 mm glucose, GlcNAc, GalN, GlcN, or N-acetylmannosamine in the assay mixture. Determination of the apparent kcat and Km values was performed by varying the GalNAc concentration in the range of 0.2–8 mm and the GlcNAc concentration in the range of 4–64 mm in the presence of a saturating concentration of ATP. Kinetic data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. A standard Michaelis-Menten model was used to determine the apparent kcat and Km values.

The GalNAc-6-P deacetylase activity was assayed by adding 5–10 μg of the purified AgaAII enzyme to 200 μl of reaction mixture containing 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mm GalNAc, 20 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, and 5 μg of the purified GalNAc kinase AgaK. The amount of GalNAc-6-P consumed after 5 min was determined by using p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde reagent and reading the absorbance at 585 nm (32). The reaction rate was proportional to the amount of the GalNAc-6-P deacetylase in the reaction mixture. The activity toward GlcNAc-6-P was also tested by using 2 mm GlcNAc-6-P.

The GalN-6-P deaminase/isomerase activity was assayed by coupling the formation of ammonium with the oxidation of NADH to NAD+ via glutamate dehydrogenase and monitoring the change in NADH absorbance at 340 nm at 30 °C. Briefly, 10 μg of purified enzyme was added to 200 μl of reaction mixture containing 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mm GalNAc, 20 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, 1 mm α-ketoglutarate, 0.3 mm NADH, 2 units of glutamate dehydrogenase, 5 μg of the purified GalNAc kinase, and 10 μg of the purified GalNAc-6-P deacetylase. The reaction rate was proportional to the amount of GalN-6-P deaminase AgaS in the reaction mixture. The activity toward GlcN-6-P was also tested by using 2 mm GlcN-6-P. The same enzymatic assay was also used for in vitro reconstitution of the conversion of GalNAc to Tag-6-P using the three purified recombinant enzymes GalNAc kinase (5 μg), GalNAc-6-P deacetylase (10 μg), and GalN-6-P deaminase/isomerase (10 μg). The reaction was started by adding 2 mm GalNAc. As controls, one or two enzymes were excluded from the reaction mixture.

RESULTS

Comparative Genomics of GalNAc Utilization in Proteobacteria

For integrated genomic reconstruction of GalNAc utilization pathways and transcriptional regulatory networks in Proteobacteria, we used the established comparative genomics techniques (24, 33) implemented in the SEED and RegPredict Web resources (16, 25). As a result, the GalNAc metabolic pathway and AgaR regulon were identified in 21 species representing six lineages of γ-Proteobacteria (Enterobacteriales, Vibrionales, Pasteurellales, Alteromonadales, Aeromonadales, and Xanthomonadales) and two lineages of α- and β-Proteobacteria (Caulobacterales and Burkholderiales, respectively). The distribution of genes encoding the GalNAc catabolic enzymes and associated transporters across the studied species is summarized in Table 1 and supplemental Table S2.

AgaR Regulons

The transcriptional factor AgaR belongs to the DeoR protein family and was initially characterized in E. coli as a repressor of the GalNAc utilization genes (12). Orthologs to the E. coli agaR gene were identified in the genomes of various γ-Proteobacteria and in two individual genomes of α- and β-Proteobacteria. In four genomes, we identified two copies of agaR genes, whereas Photobacterium profundum contains three agaR paralogs (Table 1). A strong tendency of agaR genes to cluster on the chromosome with GalNAc utilization genes was observed, suggesting conservation of the AgaR ortholog function (Fig. 2). Using the phylogenetic analysis of the identified in Proteobacteria AgaR homologs, we selected five major groups of regulators to use them for further comparative genomics based regulon reconstruction (supplemental Fig. S1). Interestingly, P. profundum and Edwardsiella tarda possess distantly related AgaR paralogs (∼45% identity), whereas the AgaR paralogs in Serratia proteamaculans and Vibrio vulnificus are 74 and 57% identical, respectively, and belong to the same phylogenetic groups on the AgaR tree.

FIGURE 2.

Genomic organization of the GalNAc utilization pathway genes. Genes and candidate AgaR-binding sites are shown by arrows and circles, respectively. Genes are colored according to their functional roles in Fig. 1 and named by the last letter of the corresponding protein. Genes from the same genetic locus that are not located immediately next to each other are separated by a slash. Genes from different genetic loci are separated by a double slash or are shown within two lines united by braces. Candidate AgaR sites are colored according to the corresponding AgaR-binding motifs shown at the bottom. Sequence logos for AgaR-binding motifs were generated by the WebLogo package. Genomic locus tags for all displayed genes are available in supplemental Table S2.

To infer the AgaR regulons in Proteobacteria, we applied the comparative genomics approach (as implemented in the RegPredict Web server) that combines identification of candidate regulator-binding sites with cross-genomic comparison of regulons. The upstream regions of GalNAc utilization genes in each group of AgaR-containing genomes were analyzed using a motif-recognition program to identify conserved AgaR-binding DNA motifs. After construction of a positional weight matrix for each identified motif, we searched for additional AgaR-binding sites in the analyzed genomes and finally performed a cross-species comparison of the predicted AgaR regulons using the phylogenetic footprinting approach (34). Multiple alignments of noncoding regulatory regions of orthologous genes from closely related γ-Proteobacterial genomes confirm high conservation of the predicted AgaR-binding sites (supplemental Fig. S2).

The predicted AgaR-binding motifs in five investigated groups share a common sequence pattern, CTTTC (Fig. 2 and supplemental Fig. S1). In group (i), which includes E. coli and related Enterobacteria, the candidate AgaR motif is in accordance with the consensus experimentally determined for E. coli AgaR using a DNase I footprinting approach (12) (supplemental Fig. S2). In groups (i), (ii), and (iii), the candidate AgaR-binding motifs have the same structure of a direct repeat with a common consensus, CTTTC-5nt-CTTTC, although the copy number and orientation of these direct repeats in the particular regulatory gene regions can be different. In contrast, the predicted regulator-binding motif for group (iv) is an inverted repeat with consensus CTTTC-15nt-GAAAG. Finally, the predicted AgaR motif for group (v) has a common structure of a tandem repeat of two GAAAG sites separated by a 16–18-nt spacer.

GalNAc/GalN Utilization Pathways

The reconstructed AgaR regulons in Proteobacteria revealed various sets of genes that are presumably involved in the GalNAc and/or GalN utilization subsystem (Table 1 and Fig. 2). A large number of the AgaR-regulated genes encode novel enzymes and various transport systems. By analyzing protein similarities and genomic contexts for these genes, we inferred their potential functional roles and reconstructed the associated GalNAc/GalN metabolic pathways (Fig. 1).

The most conserved enzyme in the GalNAc/GalN subsystem is AgaS, a hypothetical sugar phosphate isomerase from the SIS family that is present in all analyzed genomes. Previously, it was proposed that the agaI gene in E. coli codes for a deaminase/isomerase that is responsible for converting GalN-6-P to Tag-6-P (35), an essential step in the GalNAc and GalN utilization pathway (Fig. 1). However, an ortholog of the E. coli agaI gene was identified only in Enterobacter sp. 638, suggesting that AgaI plays an auxiliary role in the GalNAc pathway (supplemental Table S1). Thus, an essential GalN-6-P deaminase/isomerase was missing in GalNAc pathways in most analyzed Proteobacteria. Based on the GalNAc subsystem analysis, we tentatively assigned the missing GalN-6-P deaminase/isomerase function to the agaS gene.

The GalNAc-6-P deacetylase agaA is present in 12 studied genomes, where it is always clustered with other GalNAc utilization genes. In Shewanella spp., the aga gene clusters contain a gene encoding the predicted GalNAc-6-P deacetylase, which is most similar to the GlcNAc-6-P deacetylase NagA from Shewanella spp. (50% similarity) (36). The identified in Shewanella spp. novel variant of GalNAc-6-P deacetylase was named AgaAII to distinguish it from the E. coli AgaA enzyme. All three enzymes, AgaA from E. coli and both AgaAII and NagA from Shewanella, belong to the same COG1820 family of the amidohydrolase family. Phylogenetic analysis of this protein family has confirmed that AgaAII is a close paralog of NagA, suggesting its appearance by a recent gene duplication event (supplemental Fig. S3). Interestingly, GalNAc-6-P deacetylases of both types are missing in six analyzed Proteobacteria that have the GalN-6-P catabolic pathway, suggesting that these microorganisms can utilize GalN but not GalNAc amino sugar.

Uptake and subsequent phosphorylation of GalNAc and GalN amino sugars in E. coli are mediated by two specific PTS systems encoded by the agaBCD and agaVWEF genes from the AgaR regulon (9). Genes encoding homologous PTS systems were identified in the aga gene loci and AgaR regulons in Enterobacteria and Vibrionales. To distinguish specificities of these PTS systems, we built the phylogenetic tree for their inner membrane IIC components. The tree contains two separate clades of PTS components that are encoded by gene loci containing the adjacent agaA decetylase genes (supplemental Fig. S4). It can be hypothesized that agaA-linked PTS systems are specific to GalNAc substrate (termed PTSI and PTSIII), whereas those PTS systems that are not accompanied by AgaA are specific to GalN amino sugar (PTSII and PTSIV).

The aga-linked PTS systems are absent from Shewanella species and some other Proteobacteria. In Shewanella and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, the AgaR regulons contain novel genes encoding predicted GalNAc permease and kinase (termed AgaP and AgaK) and a TonB-dependent outer membrane transporter (termed OmpAga) that is potentially involved in the uptake of GalNAc across the outer membrane (Fig. 1). The predicted GalNAc permease AgaP belongs to the GGP sugar transporter family and is a close paralog of the GlcNAc permease NagP from Shewanella spp. (50% identity; see supplemental Fig. S5) (13). The predicted GalNAc kinase AgaK is a novel ROK-family kinase homologous to the Shewanella glucokinase GlkII (35% similarity) (13).

The aga gene clusters in Caulobacter sp. K31 and Burkholderia cenocepacia species encode a candidate sugar kinase from the BcrAD_BadFG family (termed AgaKII) and a candidate transporter from the EamA family (termed AgaPII). Because GalNAc-6-P deacetylase is absent from these two genomes, we propose that AgaPII and AgaKII are involved in GalN uptake and phosphorylation, respectively. Thus, the absence of GalNAc- or GalN-specific PTS systems in the analyzed proteobacterial genomes is complemented by the presence of novel permease and kinase genes that are predicted to function in the GalNAc/GalN uptake and phosphorylation.

The predicted AgaR regulons in many Proteobacteria include several glycoside hydrolases that can be potentially involved in the GalNAc/GalN metabolism (supplemental Table S1). For instance, in the Shewanella group the secreted α-N-acetylgalactosaminidase (termed AgaO) (37), which is classified as GH109 in the carbohydrate-active enzyme data base, is encoded in the aga gene locus. The AgaR regulons in two other γ-Proteobacteria, Photorhabdus luminescens and Aeromonas hydrophila, include an uncharacterized hydrolase from the GH36 family (termed AgaH), which includes α-N-acetylgalactosaminidases.

Experimental Characterization of the GalNAc Catabolic Pathway in Shewanella

Previously, we demonstrated that four Shewanella strains including ANA-3, MR-4, MR-7, and S. amazonensis SB2B are able to grow on GalNAc as a sole carbon and energy source (13). To confirm the predicted physiological role of the aga gene locus in GalNAc utilization, quantitative RT-PCR was carried out with total RNA isolated from Shewanella sp. ANA-3 cells grown with either Gal or GlcNAc used as a control. The expression levels of agaK, agaAII, and agaS genes in the GalNAc-grown cells were elevated >100-fold compared with the cells grown on GlcNAc (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of aga gene expression. Total RNA was isolated from Shewanella sp. ANA-3 cells grown on 10 mm GalNAc or GlcNAc as a sole carbon source. The expression levels of each gene were normalized to the gene expression in the GlcNAc-grown cells. Average ± S.D. (error bars) for six independent experiments are shown.

To provide biochemical evidence for the proposed functional assignments of aga genes, we used the recombinant AgaK, AgaAII, and AgaS proteins from Shewanella sp. ANA-3. The recombinant proteins were overexpressed in E. coli with the N-terminal His6 tag and purified using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, to test for activities of GalNAc kinase, GalNAc-6-P deacetylase, and GalN-6-P deaminase/isomerase, respectively. The predicted enzymatic activities of all three proteins were verified using the specific enzymatic assays.

The Shewanella AgaK displayed the GalNAc kinase activity with high kcat value and low apparent Km value for GalNAc (Table 2). In addition to GalNAc, various other hexoses were tested as substrates of the Shewanella AgaK. Activity was also observed with GlcNAc but not with glucose, GalN, GlcN, or N-acetylmannosamine. However, the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) value with GlcNAc was >200-fold lower than with GalNAc because of the remarkably higher value of Km and the lower value of kcat (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Kinetic constants for AgaK from Shewanella sp. ANA-3

| Substrate | kcat | Km | kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|

| s−1 | mm | m−1 s−1 | |

| GalNAc | 40.3 ± 2.7 | 0.98 ± 0.19 | 4.1 × 104 ± 0.8 × 104 |

| GlcNAc | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 37.2 ± 2.6 | 1.9 × 102 ± 0.2 × 102 |

The Shewanella AgaAII protein also exhibited a significantly higher deacetylase activity with GalNAc-6-P (7.98 μmol mg−1 min−1) than GlcNAc-6-P (0.76 μmol mg−1 min−1). Similarly, the deaminase/isomerase activity of Shewanella AgaS with GalN-6-P (9.48 μmol mg−1 min−1) was approximately 27-fold higher than with GlcN-6-P (0.35 μmol mg−1 min−1).

We further validated the inferred three-step GalNAc catabolic pathway in Shewanella by in vitro pathway reconstitution. The reaction mixtures contained GalNAc, ATP, and combinations of the purified recombinant proteins AgaK, AgaAII, and AgaS from Shewanella sp. ANA-3. The three-step biochemical conversion of GalNAc to Tag-6-P was concomitant with the formation of ammonium, which was monitored by enzymatic coupling with chromogenic conversion of NADH to NAD+ via glutamate dehydrogenase (Fig. 4). Results showed that the simultaneous presence of all three proteins, AgaK, AgaAII, and AgaS, was necessary and sufficient for transformation of GalNAc to Tag-6-P.

FIGURE 4.

In vitro reconstitution of the Shewanella GalNAc pathway. A, biochemical transformations in the GalNAc pathway and the assay used to assess the pathway reconstitution. The pathway product, ammonium, was detected at 340 nm by coupling to NADH-NAD+ conversion via glutamate dehydrogenase. B, pathway reconstitution by using the purified Shewanella sp. ANA-3 enzymes. All samples contained 2 mm GalNAc and 5–10 μg of each enzyme.

Phenotypic Characterization of aga Genes in E. coli.

In E. coli, two genes were proposed for the role of GalN-6-P deaminase/isomerase in the GalNAc catabolic pathway: agaI (previously assigned to the pathway) (35) and agaS (assigned in this work). Our comparative genomics analysis suggests that agaS is a universal gene in aga catabolic gene loci in all Proteobacteria. To uncover the identity of GalN-6-P deaminase and validate the predicted functional role of AgaS in E. coli, the chromosomal deletion mutants ΔagaI and ΔagaS were constructed and tested for their ability to grow on GalNAc as a sole carbon and energy source. Some E. coli strains (C, B, and EC3132, but not K-12) are able to grow on GalNAc as a single carbon source (9). The aga cluster in the E. coli K-12 strain has a large deletion of agaE and agaF and truncation of agaW and agaA genes, resulting in an GalNAc-negative phenotype (9). For knock-out construction and phenotypic characterization we chose the GalNAc-positive E. coli C strain ATCC 8739.

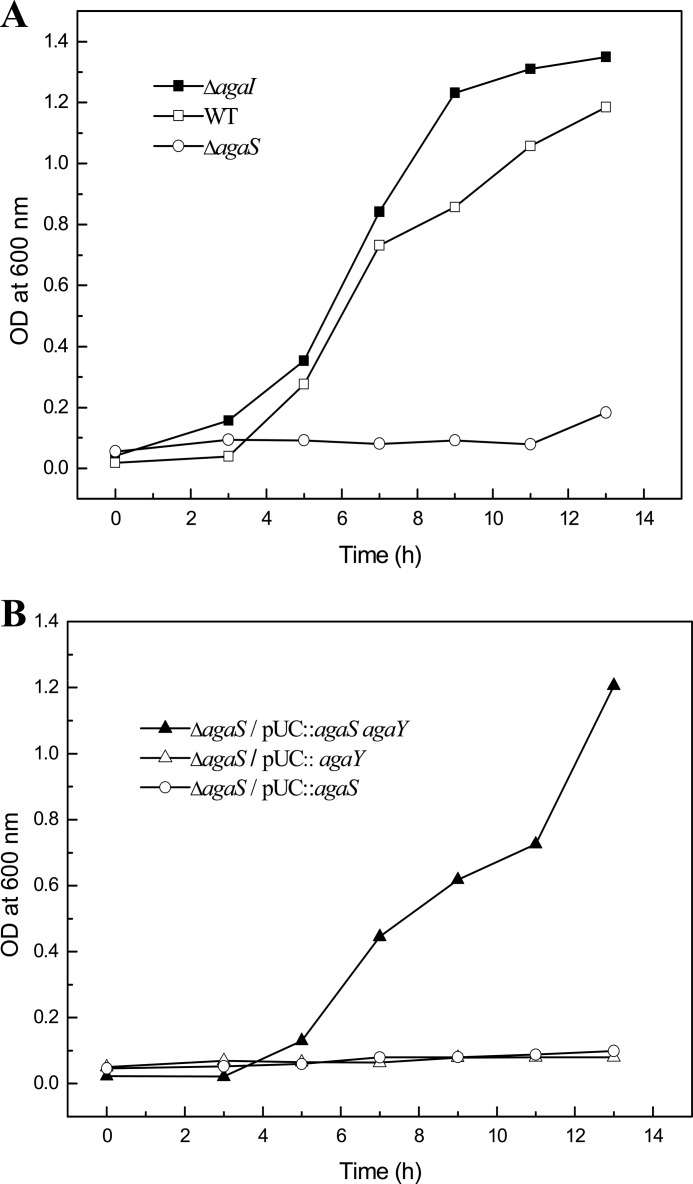

Knock-out of the agaI gene did not affect the growth of the resulting strain on GalNAc (Fig. 5A), whereas the ΔagaS mutant lost the ability to grow on GalNAc in minimal medium. Because the agaS and agaY genes form an operon (12), deletion of the agaS gene could prevent the agaY gene from being transcribed. Thus, genetic complementation experiments were performed by introducing plasmid constructs expressing agaS and/or agaY genes into the ΔagaS mutant. Expression of both agaS and agaY genes restored the ability of the ΔagaS mutant to grow on GalNAc, whereas no appreciable growth was observed when only the agaY gene was used to complement the ΔagaS mutant (Fig. 5B). Therefore, these results confirm the predicted function of the GalN-6-P deaminase agaS, an essential gene in the GalNAc/GalN catabolic pathway in E. coli.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of agaI or agaS gene deletion on GalNAc-dependent cell growth of E. coli. A, growth of ΔagaI and ΔagaS mutant strains compared with the wild type (WT) strain of E. coli ATCC 8739. B, complementation of the ΔagaS mutant of E. coli ATCC 8739 by introducing plasmid constructs expressing both agaS and agaY genes or only the agaY gene from E. coli ATCC 8739. Cells were grown in M9 minimal medium containing 10 mm GalNAc as a sole carbon source. The cell growth was monitored by measuring the A600 nm.

DISCUSSION

Although our current knowledge of sugar utilization metabolic pathways and respective genes in model bacteria such as E. coli is nearly comprehensive, the projection of this knowledge to the rapidly growing number of sequenced genomes of more distant species is the challenging problem. The major difficulties for bioinformatics-based functional gene annotations include the existence of alternative biochemical routes, nonorthologous gene replacements, and functionally heterogeneous families of paralogs. Comparative genomic context analysis based on the identification of conserved chromosomal clusters (operons) and shared regulatory sites (regulons) are particularly efficient for accurate functional assignment of previously uncharacterized genes of sugar utilization pathways (13). In this study, we used comparative genomics to reconstruct novel variants of the GalNAc/GalN amino sugar catabolic pathways in the genomes of Gram-negative bacteria from the Proteobacteria phylum.

In all studied Proteobacteria, the GalNAc utilization genes are co-localized with genes encoding orthologs of the E. coli AgaR repressor. Using the bioinformatic analysis of AgaR orthologs and aga gene regulatory regions, we identified five groups of regulators and their respective binding site motifs. All AgaR motifs contain two or more copies of conserved sequences (CTTTC) that occur either as direct or inverted repeats, depending on the type of AgaR motif (Fig. 2). We propose that these pentameric sequences represent a core site recognized by an AgaR monomer. Candidate AgaR-binding sites identified in the promoter regions of aga genes are often composed of two or more pairs of these pentameric sites, suggesting a possibility of formation of DNA loops by multisubunit complexes of AgaR repressors.

The genomic context analysis and the reconstructed AgaR regulons allowed us to identify novel GalNAc-related genes and reconstruct novel variants of GalNAc utilization pathways in Proteobacteria (Table 1). The most variable parts of the reconstructed GalNAc pathways include transport systems for amino sugar uptake and the first enzymatic steps to convert a substrate to GalN-6-P via its phosphorylation and deacetylation (Fig. 1). The following enzymatic steps for conversion of GalN-6-P to the central glycolytic intermediates are conserved in nearly all studied species.

Proteobacteria use two major strategies to import and phosphorylate amino sugars in the cytoplasm: (i) sugar-specific PTS systems or (ii) a combination of sugar-specific permeases and kinases (Fig. 1). Similarly to E. coli, GalNAc- and/or GalN-specific PTS systems were identified and annotated within the aga gene loci from Enterobacteriales and Vibrionales. In other bacterial taxa without specific PTS systems (e.g. in Shewanella spp.), we identified unique sets of GalNAc- and GalN-specific permeases and kinases (AgaP and AgaK, respectively). AgaP transporters are often accompanied by novel GalNAc-related transporters that belong to the family of outer membrane TonB-dependent receptors (OmpAga). Thus, the proposed novel pathway of GalNAc utilization in Shewanella species includes amino sugar uptake through the outer membrane by the OmpAga receptor, further transport through the inner membrane using the AgaP permease, and subsequent amino sugar phosphorylation by the AgaK kinase.

The predicted GalNAc catabolic pathway in Shewanella species including the GalNAc kinase AgaK, a novel variant of GalNAc-6-P deacetylase AgaAII, and the GalN-6-P isomerase/deaminase AgaS was experimentally validated in vitro by enzymatic assays with the purified recombinant proteins from Shewanella sp. ANA-3. AgaS is the most conserved member of the analyzed AgaR regulons and GalNAc catabolic pathways. The enzymatic function of AgaS, which was determined as a central enzyme in the GalNAc/GalN catabolic pathways, was also validated by genetic techniques in E. coli. Previously, the GalN-6-P isomerase/deaminase function in E. coli was tentatively assigned to the AgaI protein. However, we found that AgaI is not conserved in the analyzed species, being present only in the Enterobacter sp. 638, suggesting its auxiliary role. Indeed, this conclusion was proven by in vivo physiological tests, when deletion of agaS but not agaI gene abolished the growth of E. coli on GalNAc in minimal medium.

The identities of enzymes catalyzing the last two steps in the GalNAc catabolic pathway were not resolved in some analyzed Proteobacteria (Table 1). The predicted Tag-6-P kinase AgaZ is present in most studied genomes with aga genes. The Tag-1,6-PP aldolase AgaY is present mostly in Enterobacteriales and Vibrionales but is missing in Shewanella and several other lineages of Proteobacteria. Earlier reports discussed a possible role of AgaZ as a noncatalytic subunit of the AgaY aldolase (11). The observed different patterns of distribution of agaZ and agaY genes do not support this hypothesis and suggest that AgaZ has an essential functional role in the GalNAc pathway that is independent of AgaY. The proposed Tag-6-P kinase activity of AgaZ has to be confirmed in future experiments. On the other hand, the AgaY aldolase activity missing in Shewanella species can be fulfilled by a noncommitted aldolase enzyme, such as a class II fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (Fba). Fba is an essential glycolytic enzyme that is present in all Shewanella spp. (e.g. SO_0933 in S. oneidensis) (13). Interestingly, the Shewanella Fba enzymes are more similar to AgaY than to FbaA from E. coli (∼50 and 35% of sequence similarity, respectively).

The phylogenetic analysis of proteins from the GalNAc catabolic pathway suggests the following evolutionary scenario for emergence of the unique pathway variant in Shewanella genus. Several novel components of the GalNAc pathway (AgaP, AgaK, and AgaAII) are present only in Shewanella spp. and likely emerged via gene duplication followed by functional divergence. In contrast, the closest orthologs of other components (AgaS, AgaZ, and AgaR repressors) were identified in all other studied Proteobacteria. Thus, the GalNAc pathway in Shewanella is composed of both universal and lineage-specific components. The AgaP permease and AgaAII deacetylase were likely introduced by genus-specific duplication and specialization of, respectively, the ancestral NagP and NagA proteins from the GlcNAc utilization pathway. Interestingly, the AgaAII deacetylase retains a residual activity on GlcNAc-6-P, which is 10-fold less than its activity with GalNAc-6-P. Amino sugar specificities of NagP and AgaP transporters are yet to be determined. Interestingly, the AgaS deaminase, which is similar (21% identity) to the GalN-6-P NagBII deaminase from the GlcNAc utilization pathway in Shewanella spp. (36), has 27-fold less activity on GlcN-6-P than on the GalN-6-P physiological substrate.

The ecophysiological importance of the GalNAc utilization pathway in four Shewanella species that were isolated from various aquatic sources, such as the Black Sea or the Amazon River delta, is not clear. One possibility is that they colonize aquatic animals and utilize GalNAc from the host intestinal mucin. In agreement with this hypothesis, the aga operon in Shewanella encodes the secreted glycoside hydrolase AgaO that can cleave α-1,3-linked GalNAc residues from animal-derived blood cell epitopes (37).

A unique variant of the GalN utilization pathway was identified in Haemophilus parasuis, a pathogenic bacterium causing Glasser disease in pigs. The agaR-agaS-PTSV-bgl-agaYII gene cluster in H. parasuis encodes two sets of proteins of presumably different evolutionary origins. First, the H. parasuis AgaR and AgaS proteins are mostly similar to their respective GalNAc pathway components from Enterobacteria. Second, both the PTSV components and a putative cytoplasmic β-galactosidase (Bgl) have best homologs in the Firmicutes phylum, suggesting that they were likely acquired by horizontal gene transfer. For instance, an orthologous PTSV system is present in eight Streptococcus genomes (e.g. SP_0061–64 in S. pneumoniae), where it has a similar arrangement with bgl and agaS genes. Thus, we propose that H. parasuis possesses a unique pathway for utilization of a GalN-containing disaccharide, possibly of animal origin. Interestingly, the aga gene locus in H. parasuis contains an alternative Tag-1,6-PP aldolase from the LacD family, termed AgaYII, that participates in the Tag-6-P pathway of galactose 6-phosphate degradation in Gram-positive bacteria (38).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrei Osterman for useful discussions and Pavel Novichkov for providing support with RegPredict software.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM077402 through the NIGMS. This work was also supported by the Genomic Science Program (GSP), Office of Biological and Environmental Research (OBER), U.S. Dept. of Energy (DOE) under Contract DE-SC0004999 with the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (SBMRI) and as a contribution of the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) Foundational Scientific Focus Area, and by the National Science Foundation of China Grants 30970035 and 31070033), the Russian Foundation for Basic Research Grant 10-04-01768, and the Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Grant KSCX2-EW-G-5.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1–S5.

- GalNAc

- N-acetyl-d-galactosamine

- GalN

- d-galactosamine

- GalN-6-P

- d-galactosamine 6-phosphate

- GalNAc-6-P

- N-acetyl-d-galactosamine 6-phosphate

- GlcN

- d-glucosamine

- GlcN-6-P

- d-glucosamine 6-phosphate

- GlcNAc

- N-acetyl-d-glucosamine

- GlcNAc-6-P

- N-acetyl-d-glucosamine 6-phosphate

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- nt

- nucleotide(s)

- PTS

- phosphotransferase system

- Tag-6-P

- tagatose 6-phosphate

- Tag-1,6-PP

- tagatose 1,6-bisphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Freymond P. P., Lazarevic V., Soldo B., Karamata D. (2006) Poly(glucosyl-N-acetylgalactosamine 1-phosphate), a wall teichoic acid of Bacillus subtilis 168: its biosynthetic pathway and mode of attachment to peptidoglycan. Microbiology 152, 1709–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bernatchez S., Szymanski C. M., Ishiyama N., Li J., Jarrell H. C., Lau P. C., Berghuis A. M., Young N. M., Wakarchuk W. W. (2005) A single bifunctional UDP-GlcNAc/Glc 4-epimerase supports the synthesis of three cell surface glycoconjugates in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 4792–4802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carraway K. L., Hull S. R. (1991) Cell surface mucin-type glycoproteins and mucin-like domains. Glycobiology 1, 131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abu-Qarn M., Eichler J., Sharon N. (2008) Not just for Eukarya anymore: protein glycosylation in Bacteria and Archaea. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18, 544–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barr J., Nordin P. (1980) Biosynthesis of glycoproteins by membranes of Acer pseudoplatanus: incorporation of mannose and N-acetylglucosamine. Biochem. J. 192, 569–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davis C. G., Elhammer A., Russell D. W., Schneider W. J., Kornfeld S., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. (1986) Deletion of clustered O-linked carbohydrates does not impair function of low density lipoprotein receptor in transfected fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 2828–2838 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sadler J. E., Paulson J. C., Hill R. L. (1979) The role of sialic acid in the expression of human MN blood group antigens. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 2112–2119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reizer J., Ramseier T. M., Reizer A., Charbit A., Saier M. H., Jr. (1996) Novel phosphotransferase genes revealed by bacterial genome sequencing: a gene cluster encoding a putative N-acetylgalactosamine metabolic pathway in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 142, 231–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brinkkötter A., Klöss H., Alpert C., Lengeler J. W. (2000) Pathways for the utilization of N-acetylgalactosamine and galactosamine in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 37, 125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nobelmann B., Lengeler J. W. (1996) Molecular analysis of the gat genes from Escherichia coli and of their roles in galactitol transport and metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 178, 6790–6795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brinkkötter A., Shakeri-Garakani A., Lengeler J. W. (2002) Two class II md-tagatose-bisphosphate aldolases from enteric bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 177, 410–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ray W. K., Larson T. J. (2004) Application of AgaR repressor and dominant repressor variants for verification of a gene cluster involved in N-acetylgalactosamine metabolism in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 51, 813–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rodionov D. A., Yang C., Li X., Rodionova I. A., Wang Y., Obraztsova A. Y., Zagnitko O. P., Overbeek R., Romine M. F., Reed S., Fredrickson J. K., Nealson K. H., Osterman A. L. (2010) Genomic encyclopedia of sugar utilization pathways in the Shewanella genus. BMC Genomics 11, 494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dehal P. S., Joachimiak M. P., Price M. N., Bates J. T., Baumohl J. K., Chivian D., Friedland G. D., Huang K. H., Keller K., Novichkov P. S., Dubchak I. L., Alm E. J., Arkin A. P. (2010) MicrobesOnline: an integrated portal for comparative and functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D396–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D. J. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Overbeek R., Begley T., Butler R. M., Choudhuri J. V., Chuang H. Y., Cohoon M., de Crécy-Lagard V., Diaz N., Disz T., Edwards R., Fonstein M., Frank E. D., Gerdes S., Glass E. M., Goesmann A., Hanson A., Iwata-Reuyl D., Jensen R., Jamshidi N., Krause L., Kubal M., Larsen N., Linke B., McHardy A. C., Meyer F., Neuweger H., Olsen G., Olson R., Osterman A., Portnoy V., Pusch G. D., Rodionov D. A., Rückert C., Steiner J., Stevens R., Thiele I., Vassieva O., Ye Y., Zagnitko O., Vonstein V. (2005) The subsystems approach to genome annotation and its use in the project to annotate 1000 genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 5691–5702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saier M. H., Jr., Yen M. R., Noto K., Tamang D. G., Elkan C. (2009) The Transporter Classification Database: recent advances. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D274–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009) The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Punta M., Coggill P. C., Eberhardt R. Y., Mistry J., Tate J., Boursnell C., Pang N., Forslund K., Ceric G., Clements J., Heger A., Holm L., Sonnhammer E. L., Eddy S. R., Bateman A., Finn R. D. (2012) The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D290–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Edgar R. C. (2004) MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5, 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Felsenstein J. (1996) Inferring phylogenies from protein sequences by parsimony, distance, and likelihood methods. Methods Enzymol. 266, 418–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huson D. H., Richter D. C., Rausch C., Dezulian T., Franz M., Rupp R. (2007) Dendroscope: an interactive viewer for large phylogenetic trees. BMC Bioinformatics 8, 460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Petersen T. N., Brunak S., von Heijne G., Nielsen H. (2011) SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 8, 785–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rodionov D. A. (2007) Comparative genomic reconstruction of transcriptional regulatory networks in bacteria. Chem. Rev. 107, 3467–3497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Novichkov P. S., Rodionov D. A., Stavrovskaya E. D., Novichkova E. S., Kazakov A. E., Gelfand M. S., Arkin A. P., Mironov A. A., Dubchak I. (2010) RegPredict: an integrated system for regulon inference in prokaryotes by comparative genomics approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W299–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J. M., Brenner S. E. (2004) WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Novichkov P. S., Laikova O. N., Novichkova E. S., Gelfand M. S., Arkin A. P., Dubchak I., Rodionov D. A. (2010) RegPrecise: a database of curated genomic inferences of transcriptional regulatory interactions in prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D111–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pinchuk G. E., Ammons C., Culley D. E., Li S. M., McLean J. S., Romine M. F., Nealson K. H., Fredrickson J. K., Beliaev A. S. (2008) Utilization of DNA as a sole source of phosphorus, carbon, and energy by Shewanella spp.: ecological and physiological implications for dissimilatory metal reduction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 1198–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sambrook J., Russell D. W. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 30. Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang C., Rodionov D. A., Rodionova I. A., Li X., Osterman A. L. (2008) Glycerate 2-kinase of Thermotoga maritima and genomic reconstruction of related metabolic pathways. J. Bacteriol. 190, 1773–1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reissig J. L. (1956) Phosphoacetylglucosamine mutase of Neurospora. J. Biol. Chem. 219, 753–767 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Osterman A., Overbeek R. (2003) Missing genes in metabolic pathways: a comparative genomics approach. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 7, 238–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qin Z. S., McCue L. A., Thompson W., Mayerhofer L., Lawrence C. E., Liu J. S. (2003) Identification of co-regulated genes through Bayesian clustering of predicted regulatory-binding sites. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 435–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mukherjee A., Mammel M. K., LeClerc J. E., Cebula T. A. (2008) Altered utilization of N-acetyl-md-galactosamine by Escherichia coli O157:H7 from the 2006 spinach outbreak. J. Bacteriol. 190, 1710–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang C., Rodionov D. A., Li X., Laikova O. N., Gelfand M. S., Zagnitko O. P., Romine M. F., Obraztsova A. Y., Nealson K. H., Osterman A. L. (2006) Comparative genomics and experimental characterization of N-acetylglucosamine utilization pathway of Shewanella oneidensis. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29872–29885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu Q. P., Sulzenbacher G., Yuan H., Bennett E. P., Pietz G., Saunders K., Spence J., Nudelman E., Levery S. B., White T., Neveu J. M., Lane W. S., Bourne Y., Olsson M. L., Henrissat B., Clausen H. (2007) Bacterial glycosidases for the production of universal red blood cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 454–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rosey E. L., Oskouian B., Stewart G. C. (1991) Lactose metabolism by Staphylococcus aureus: characterization of lacABCD, the structural genes of the tagatose 6-phosphate pathway. J. Bacteriol. 173, 5992–5998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.