Background: Cathepsins K and S are powerful elastases and collagenases, but their combined activities toward each other and substrates are unclear.

Results: Cathepsin S degrades cathepsin K even with elastin and collagen present.

Conclusion: Cathepsin cannibalism is a novel mechanism describing protease interactions.

Significance: Cannibalistic interactions reduce total substrate degradation and must be considered for accurate descriptions of proteolytic systems.

Keywords: Cancer, Computational Biology, Enzyme Degradation, Enzyme Kinetics, Osteoporosis, Proteases

Abstract

Cathepsins S and K are potent mammalian proteases secreted into the extracellular space and have been implicated in elastin and collagen degradation in diseases such as atherosclerosis and osteoporosis. Studies of individual cathepsins hydrolyzing elastin or collagen have provided insight into their binding and kinetics, but cooperative or synergistic activity between cathepsins K and S is less described. Using fluorogenic substrate assays, Western blotting, cathepsin zymography, and computational analyses, we uncovered cathepsin cannibalism, a novel mechanism by which cathepsins degrade each other as well as the substrate, with cathepsin S predominantly degrading cathepsin K. As a consequence of these proteolytic interactions, a reduction in total hydrolysis of elastin and type I collagen was measured compared with computationally predicted values derived from individual cathepsin assays. Furthermore, type I collagen was preserved from hydrolysis when a 10-fold ratio of cathepsin S cannibalized the highly collagenolytic cathepsin K, preventing its activity. Elastin was not preserved due to strong elastinolytic ability of both enzymes. Together, these results provide new insight into the combined proteolytic activities of cathepsins toward substrates and each other and present kinetic models to consider for more accurate predictions and descriptions of these systems.

Introduction

Cysteine cathepsins are a family of proteases that comprises 11 members. Cathepsins were first identified and characterized in lysosomes but are now known to be secreted extracellularly into the local microenvironment, where they participate in extracellular matrix (ECM)2 remodeling. Specifically, cathepsins K and S have been implicated in elastin degradation in cardiovascular disease and are produced and secreted by endothelial cells, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells in the arterial wall (1–6). Genetic knockdown of either cathepsin S or K showed reduced elastic lamina degradation in separate mouse models of atherosclerosis (3, 7). Although both cathepsins K and S are notable for high elastinolytic activity (8), each protease has its own unique properties. Cathepsin K is the most potent mammalian collagenase, capable of cleaving collagens I and II both intrahelically and at the telopeptide regions (9, 10), and for these functions is the major protease used by osteoclasts for bone resorption (11, 12). Cathepsin S is noteworthy for its elastase activity and maintaining its proteolytic activity at neutral pH, making it unique among the cathepsins, which generally prefer acidic environments (13, 14).

Cathepsin activity is regulated by many factors in the surrounding microenvironment, with major influences, including temperature, pH, and oxidative potential (15, 16). The binding affinities and hydrolytic rates for ECM components vary by cathepsin. Taken together, in vivo, cathepsins exist as a system of relatively short-lived enzymes working simultaneously on multiple substrates, both intra- and extracellularly, making it difficult to separate and distinguish the activity of an individual cathepsin experimentally (17).

Computational models of proteolytic activity have provided significant insight into the kinetics of these enzymes' proteolytic activity in varied microenvironments and even suggested cathepsin adsorption to soluble and insoluble elastins as a mechanism to stabilize and extend cathepsin K, L, and S half-lives and activity (18). This insight was obtained from observations of individual cathepsins hydrolyzing elastin, but in tissue-degradative diseases such as atherosclerosis, where elastin is a primary ECM-remodeling target, macrophages and smooth muscle cells in the developing plaque region secrete a combination of different cathepsins into the extracellular space. Cooperative or synergistic activity between cathepsins K and S during degradation of elastin and collagen, two dominant structural ECM proteins in the arterial wall, has not been studied but belies a potential mechanism for additional regulation of cathepsin regulation further complicated by the different affinities and rates of catalysis of cathepsins K and S for elastin and collagen. Computational modeling provides the ability to probe for such interactive proteolysis, allowing us to separately parse cathepsin K and S activity in extracellular environments where they are both present and degrading ECM.

Here, we take a step toward understanding the combined proteolytic activity of cathepsins K and S for elastin and type I collagen using experimental and computational approaches. Through these studies, we uncovered unexpected proteolysis of cathepsin S cleaving cathepsin K, termed here cathepsin cannibalism, which reduced the total elastin- and collagen-degradative activity in the multiple cathepsin system. We further show the physiological implications of these interactions for regulating ECM proteolysis; cathepsin cannibalism protects type I collagen through a reduction in the amount of highly collagenolytic cathepsin K available due to cathepsin S degradation of cathepsin K.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fluorescent Elastase Activity Assays

Five pmol of recombinant human cathepsin K from NSO cells (Enzo) or recombinant human cathepsin S from insect cells (Enzo) was incubated with 50 μg/ml DQ elastin (Invitrogen) in phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 2 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.1% Brij 35 for defined time periods in a 96-well plate, and hydrolytic activity was determined by an increase in fluorescence measured at an excitation of 485 nm and an emission of 525 nm with a SpectraMax Plus microplate reader (Molecular Devices). A no-enzyme control was used to subtract background fluorescence.

Substrate Degradation Assays

Five pmol of cathepsin K or S was incubated with 50 μg/ml soluble elastin (Elastin Products), VGVAPG peptides (Elastin Products), VAPG peptide (Sigma-Aldrich), or 500 μg/ml rat tail type I collagen (R&D Systems) in phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 2 mm DTT, and 1 mm EDTA for defined time periods. Laemmli buffer with or without β-mercaptoethanol was added to prepare samples for SDS-PAGE/Western blotting or cathepsin zymography, respectively. SDS-polyacrylamide gels were stained with Coomassie Blue and were imaged after destaining with an ImageQuant LAS 4000 system (GE Healthcare). All recombinant cathepsins are from human sequences and were purchased in mature forms.

Western Blotting

SDS-PAGE was performed on aliquots of cathepsin samples prepared as described above. Protein was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) and probed with monoclonal anti-cathepsin K antibody clone 182-12G5 (Millipore) and anti-cathepsin S antibodies (R&D Biosystems). Donkey anti-mouse or anti-goat secondary antibodies tagged with an infrared fluorophore (Rockland Immunochemicals) were used to image protein with a LI-COR Odyssey scanner.

Kinetic Model Development

Computational models of cathepsin-mediated proteolysis of ECM proteins were built using the MATLAB SimBiology suite (MathWorks). These models were constructed using mass action kinetics describing cathepsin binding and hydrolysis of substrates. Initial models assumed one enzyme binding to one substrate with associated on (kon) and off (koff) rates and then catalysis of the substrate to form product and free enzyme at some rate (kcat). Enzyme inactivation, whether by denaturation, degradation, or some other means, was lumped into the rate parameter kinact. All reaction equations are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Substrate proteolysis model with cathepsin cannibalism-governing equations

catK, cathepsin K; catS, cathepsin S.

| Cathepsin K inactivation | |

| Cathepsin S inactivation | |

| Cathepsin cannibalism | |

| Proteolysis by cathepsin K | |

| Proteolysis by cathepsin S |

Parameter Estimation

Initial guesses for the rate constants were from literature values, and then the parameters were fit to experimental data using a nonlinear minimum search algorithm in MATLAB by minimizing the difference between observed and predicted product formation. Fluorescent elastin product was used to construct elastin models. For collagenolysis simulations, collagen remaining following substrate degradation assays was determined via densitometry of Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels and used to fit collagen rate parameters.

Parameter estimation for the elastin model consisted of two phases; the first parameters elucidated were the binding and catalysis rates (kon, koff, and kcat). These kinetic rates were derived using only the early time points of the fluorescent elastase hydrolysis curves, where product formation was approximately linear and inactivation of the enzymes was assumed to be minimal. Inactivation rates for the enzymes (kinact) were subsequently fit using the same algorithm inclusive of the entire time span of enzyme activity.

Collagenolysis models required fitting parameters across different cathepsin S:K ratios. To do so, models were constructed for each cathepsin S:K ratio data point with identical rate parameters while the concentration of cathepsin S was varied. The rate constants were then determined by minimizing the difference between the predicted and observed collagen remaining.

Cathepsin Zymography

This protocol is based on our previously published protocol (19). Nonreducing loading buffer (5× 0.05% bromphenol blue, 10% SDS, 1.5 m Tris, and 50% glycerol) was added to all samples prior to loading. Protein was resolved on 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing 0.2% gelatin at 4 °C. Gels were removed, and enzymes were renatured in 65 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.4) with 20% glycerol for three washes of 10 min each. Gels were then incubated in activity buffer (0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 1 mm EDTA, and 2 mm DTT freshly added) for 30 min at room temperature. This activity buffer was exchanged for fresh activity buffer of the same pH, and incubation was continued for 18–24 h (overnight) at 37 °C. The gels were rinsed once with deionized water and incubated for 1 h in Coomassie Blue stain (10% acetic acid, 25% isopropyl alcohol, and 4.5% Coomassie Blue), followed by destaining (10% isopropyl alcohol and 10% acetic acid). Gels were imaged using an ImageQuant LAS 4000 system.

RESULTS

Cathepsins K and S Co-degrade Elastin in a Non-additive Fashion

Mechanisms behind cathepsin inactivation have been cited as due to oxidation, pH, denaturation, and other mechanisms (16, 18, 20), but kinetics of autodigestion have been less well described. Cathepsins K and S are both strong elastases implicated in proteolyzing elastic lamina in vascular structures (8), and to gain insight into how the enzymes' loss of activity via inactivation or degradation affects substrate hydrolysis, five pmol of each enzyme were incubated separately with 50 μg/ml DQ elastin, a fluorogenic elastin substrate that releases fluorescence after proteolytic cleavage. Fluorescence was assayed for up to 3 h to measure elastinolysis (Fig. 1A). For cathepsins K (white triangles) and S (white squares), product formation, measured as increased fluorescence, slowed significantly by 1 h. Kinetic parameters for each cathepsin were determined from these data, and a computational model of cathepsin K and S elastase activity was developed to predict their combined elastase activity and is shown by the solid red line. To experimentally determine whether these two proteases work synergistically to degrade elastin, as may be seen in macrophages that secrete both cathepsins K and S into the extracellular space, 5 pmol of each cathepsins K and S were co-incubated with fluorogenic elastin. Elastinolysis measured experimentally (red circles) was substantially less than computationally predicted values (red line).

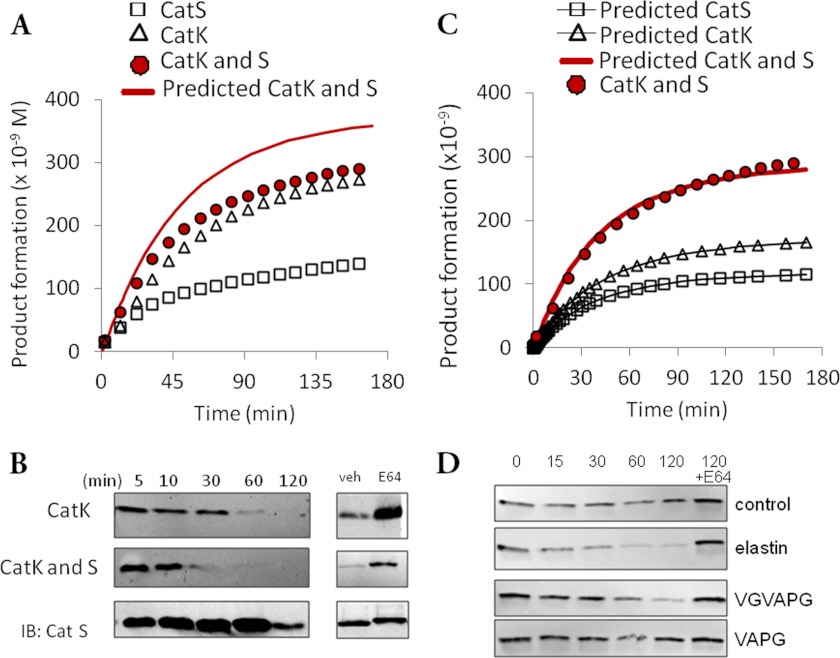

FIGURE 1.

Cathepsin cannibalism interaction is revealed during co-incubation of cathepsins K and S on elastin. A, cathepsin K (CatK; white triangles), cathepsin S (CatS; white squares), or both cathepsins K and S together (red circles) were incubated with fluorogenic elastin, and fluorescence was measured. Predicted elastinolysis (red line) and observed elastinolysis (red circles) are shown. B, cathepsin K was incubated with or without cathepsin S with non-fluorogenic elastin. Reactions were terminated and loaded for Western blotting. All experiments were repeated at least three different times, with representative results are shown. IB, immunoblot. C, contributions to total elastinolytic product formation by cathepsins K (white triangles) and S (white squares) are corrected upon introduction of cathepsin S cannibalism of cathepsin K to the reaction model. D, incubation of cathepsin K with no substrate (control), soluble elastin, VGVAPG elastin peptide, or VAPG elastin peptide to determine the elastin fragment that mediates loss of cathepsin K.

We confirmed that these assays were in the linear fluorescence range by testing increasing concentrations of the fluorogenic elastin substrate from 1 to 100 μg/ml (supplemental Fig. 1); additionally, the maximum potential fluorescence was not reached, as pancreatic elastase incubated with the same concentrations of DQ elastin generated five times the fluorescence signal (data not shown).

Western blotting for cathepsins K and S was performed after co-incubation with soluble elastin for defined time periods to determine whether proteolytic degradation reduced the observed overall elastase activity. Immunodetected bands of cathepsin K disappeared as quickly as 30 min when co-incubated with cathepsin S compared with 60 min when incubated alone (Fig. 1B). This additional degradation could be blocked by the addition of E-64, a small molecule cathepsin inhibitor, suggesting proteolytic cleavage. This appeared to be due to cathepsin S hydrolysis of cathepsin K because the cathepsin S protein band was not diminished during co-incubation. We termed this cathepsin cannibalism, a mechanism by which one enzyme proteolyzes its own family member.

To develop this hypothesis of cannibalistic interactions, cannibalism reaction terms were introduced for cathepsin S degrading cathepsin K in the elastin co-incubation model. In this new model, we assumed that cathepsin S binds to cathepsin K in a catalytically productive manner to form an enzyme-enzyme complex. The cathepsin K can then be cleaved into degradation products, and free cathepsin S is returned to the system, effectively treating cathepsin K as an additional substrate for cathepsin S with unique affinities and catalytic rates (Table 1). This new model was able to recapitulate the experimental data for the co-incubated cathepsins (Fig. 1C, red line) and revealed that reductions in total elastinolytic activity were due to proteolysis of mature active cathepsin K in the combined system. Using this newly defined cathepsin cannibalism model to calculate the separate contributions of cathepsins K and S to total elastinolytic activity, the fraction due to cathepsin K decreased from 94% to just 59% of the total.

To determine which elastin fragments are involved in cathepsin K degradation, we incubated 1 pmol of cathepsin K with 50 μg/ml soluble elastin, VGVAPG elastin fragment, VAPG elastin fragment, or no substrate for 0, 15, 30, 60, or 120 min; a 120-min reaction was also incubated with E-64 to inhibit cathepsin K proteolytic activity. Reactions were terminated by the addition of reducing Laemmli buffer, and samples prepared were for Western blotting with anti-cathepsin K antibodies. The results are shown in Fig. 1D. As expected, the immunodetectable cathepsin K disappeared faster in the presence of soluble elastin compared with controls. The VGVAPG fragment of elastin has been implicated in a number of studies since first being identified as an important chemotactic fragment (21) and, when incubated with cathepsin K, slowed the loss of immunodetectable cathepsin K. However, incubation with the VAPG motifs, missing the initial VG amino acids, showed the greatest reduction in loss of cathepsin K as indicated by the sustained band intensity (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these results suggest that there are several motifs in the full-length elastin monomers that contribute to cathepsin K degradation (e.g. VGVAPG), but that the VG repeats may be most important in mediating this cathepsin K degradation in the presence of elastin, as the VAPG fragment alone minimizes the loss of cathepsin K.

Cathepsin Cannibalism Occurs on Collagen as Well as Elastin

Both cathepsins K and S cleave elastin, albeit with different affinities and catalytic rates, but only cathepsin K cleaves triple helical type I and II collagens (9). To determine whether cathepsin cannibalism is unique to elastin or occurs while degrading other ECM substrates, cathepsins K and S were incubated either separately or together with 500 μg/ml type I collagen for increasing time periods up to 2 h. E-64 was also incubated with samples for 2 h to inhibit cathepsin proteolytic activity. Laemmli buffer was added to stop the reactions, and samples were loaded for SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining to monitor collagen hydrolysis as described (22). Cathepsin K effectively degraded type I collagen as indicated by reduced Coomassie Blue staining at 150 kDa, but cathepsin S did not (Fig. 2A).

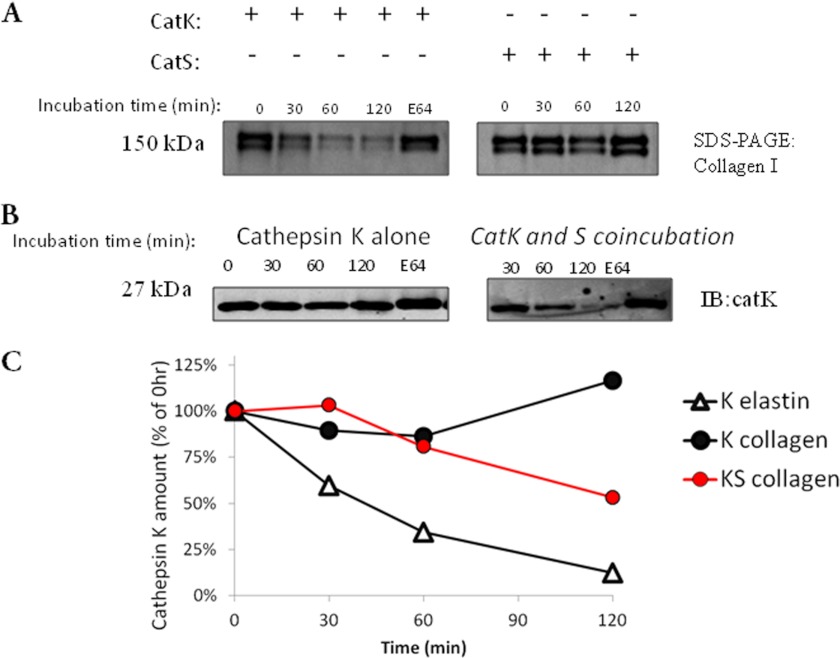

FIGURE 2.

Cathepsin S cannibalism of cathepsin K occurs on type I collagen. Cathepsins K (CatK) and S (CatS) were incubated either separately or together with type I collagen for increasing time periods. Samples were loaded for SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining (A) and for immunoblotting (IB) with antibodies against cathepsin K (B). All experiments were repeated at least three times, and representative gels/blots are shown. C, densitometric analysis of cathepsin K Western blots on both elastin and collagen in the presence or absence of cathepsin S.

Western blotting was performed to probe for cathepsin K protein remaining at each time point. Cathepsin K protein was stabilized in the presence of type I collagen over this 2-h period compared with its degradation in the presence of elastin (Fig. 1B); however, when co-incubated with cathepsin S, immunodetectable cathepsin K decreased with time, suggesting that cannibalism was occurring on collagen as well (Fig. 2B). Densitometry of the cathepsin K immunoblots is summarized in Fig. 2C, indicating that loss of cathepsin K was minimized on collagen compared with elastin, but cannibalism by cathepsin S still occurred during co-incubation and could reduce the amount of cathepsin K protein present.

Cathepsin S at a 10-fold Ratio Preserves Type I Collagen and Degrades Cathepsin K

With the cathepsin S low hydrolytic activity of collagen I, we hypothesized that at some ratiometric amount of cathepsin S to K, cannibalism of cathepsin K in a collagen-rich environment could serve to reduce collagen degradation, thereby preserving it. To test this hypothesis, cathepsin K (1 pmol) was incubated with increasing ratiometric amounts of cathepsin S (0.001-, 0.01-, 0.1-, 1-, and 10-fold) and 500 μg/ml type I collagen for 1 h. The resultant proteolysis and residual cathepsin activity were analyzed by Western blotting, SDS-PAGE, and cathepsin zymography (Fig. 3). Cathepsin K protein was visibly reduced at a 10-fold ratio of cathepsin S:K, coincident with type I collagen preservation in Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Collagen was also preserved when E-64 was added.

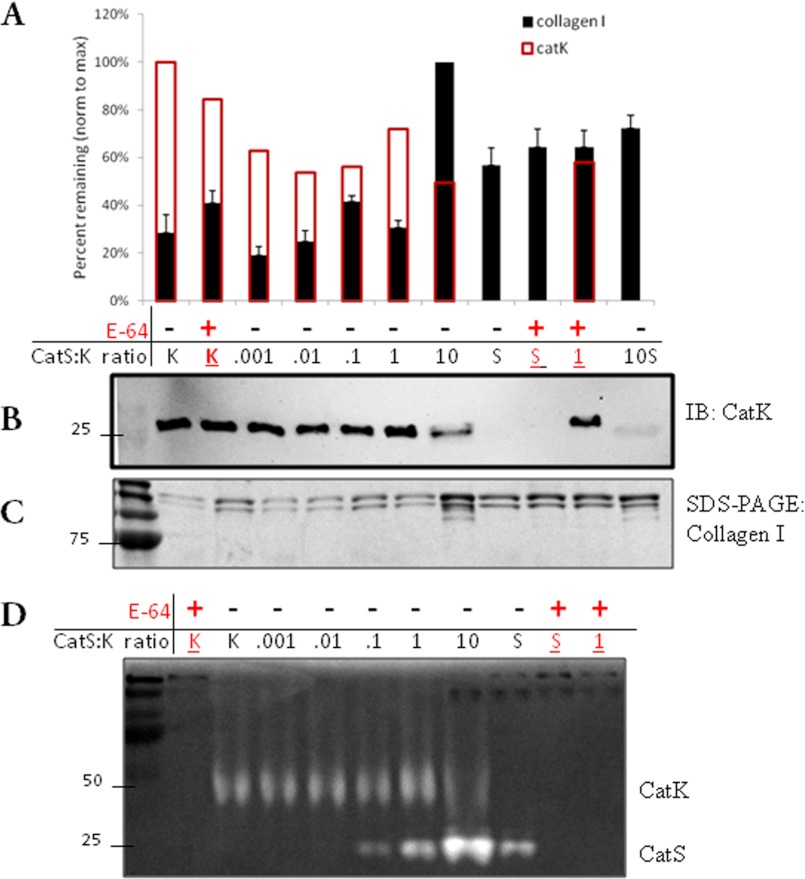

FIGURE 3.

Cathepsin cannibalism protects type I collagen from degradation when incubating cathepsin S at a 10-fold ratio to cathepsin K. Recombinant cathepsin K (catK) was incubated with collagen I and ratiometric concentrations of recombinant cathepsin S to K (CatS:K) at 0:1 to 10:1 ratios. Reactions were terminated after 1 h. A, densitometric analysis of cathepsin K Western blots (red lines) and Coomassie Blue-stained collagen I bands after SDS-PAGE (black bars). Western blots (B) and SDS-polyacrylamide gels (C) are shown. IB, immunoblot. D, aliquots of samples were loaded for cathepsin zymography to image mature cathepsin K and S activities remaining after the co-incubation and cannibalism periods. All experiments were repeated at least three times, and representative gels and blots are shown. Error bars indicate S.E. for densitometry.

Multiplex cathepsin zymography is an assay that visualizes active mature cathepsins S and K and distinguishes them by their unique electrophoretic migration distances; samples of the ratiometric incubations prepared for zymography revealed that the most intense cathepsin S cleared bands were seen in the same lane as the decreased cathepsin K cleared bands of activity at a 10-fold ratio. This indicated a decrease in cathepsin K activity remaining at the 10-fold cathepsin S:K ratio (Fig. 3D).

Computational Model Predicts That Cathepsin Cannibalism Preserves Type I Collagen but Not Elastin

Using kinetic parameters derived from the previous experiments, we developed computational models of cathepsin S cannibalism of cathepsin K during collagen degradation. The predicted and observed values for collagen remaining after a 1-h incubation period are shown in Fig. 4A. From this, we were able to extrapolate a time course of collagen degradation, with the arrow in Fig. 4B indicating increasing collagen preservation as the initial cathepsin S:K ratio was increased.

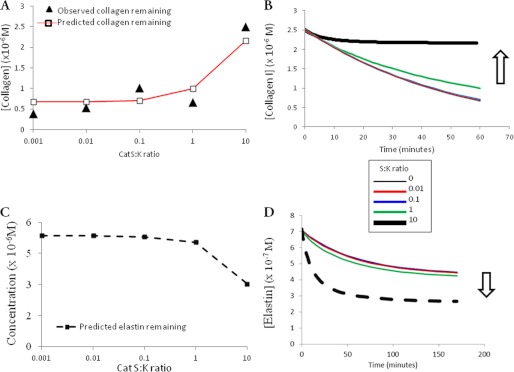

FIGURE 4.

Substrate preservation due to cathepsin cannibalism is unique to collagen I and does not occur on elastin. A, end point computed values of collagen remaining after 1 h of proteolysis (red line) compared with observed experimental values (black triangles). B, collagen degradation over time as predicted by the computational model for the increasing cathepsin S:K (CatS:K) ratios. C, end point computed values of elastin after 1 h of proteolysis. D, elastin degradation over time as predicted by the computational model for the different cathepsin S:K ratios.

If the collagen I preservation effect of cathepsin cannibalism resulted from the low catalytic efficiency of cathepsin S for the substrate, then substrate preservation might not occur on elastin, a substrate that both cathepsins K and S readily proteolyze. To test this, the cathepsin cannibalism model of elastin co-incubation detailed in Fig. 1C was used to predict the effects of increased cathepsin S:K ratios on elastin substrate hydrolysis. Predictions for total elastin remaining following a 1-h co-incubation with an increasing cathepsin S:K ratio are shown in Fig. 4C. Contrary to the collagen I degradation model, more elastin degradation products were formed with increasing ratiometric amounts of cathepsin S, and there was no elastin preservation effect (Fig. 4D).

DISCUSSION

There is a dearth of information on the interactive degradation that will occur if cathepsins are simultaneously secreted to work on the same ECM protein substrates, as has been shown in atherosclerosis, osteoporosis, tumor metastasis, and other tissue-destructive disease microenvironments. There has been an implicit assumption of enzyme inertness, which presupposes that there are negligible degradative interactions between proteases and assumes that each cathepsin focuses solely on hydrolyzing the substrate. We show here that cathepsin interactive proteolysis of each other negates this assumption. We have termed this phenomenon cathepsin cannibalism, where cathepsin S degrades cathepsin K and, in the presence of ECM substrate proteins, can result in a reduction of total substrate proteolysis.

Both cathepsins K and S are strong elastases, but their collagenolytic activity differs significantly: cathepsin K readily cleaves type I collagen both intrahelically and in the telopeptide regions, a unique feature among mammalian collagenases (9). Improved cathepsin K stability in the presence of type I collagen may be an important factor to consider in the context of remodeling diseases such as osteoporosis and arthritis, where collagen I is excessively degraded, and cellular expression of cathepsin K is pathologically increased (23, 24). On the other hand, cathepsin S has a much lower binding affinity and catalytic rate for collagen I and cleaves only at the telopeptide regions of the molecule, regions that are increasingly exposed after hydrolysis by cathepsin K. However, the affinity for and catalysis of cathepsin K by cathepsin S were found to be preferential over its collagenolytic activity in this study. In an environment rich with type I collagen and excess cathepsin K such as osteoporotic bone, cathepsin S cleavage of cathepsin K may actually preserve the collagen by degrading the cathepsin K present and potentially help maintain the bone structure and biomechanics. This mechanism of protease “inhibition” is a novel way in which these enzymes may be working against each other in tissue remodeling and potentially diseased environments.

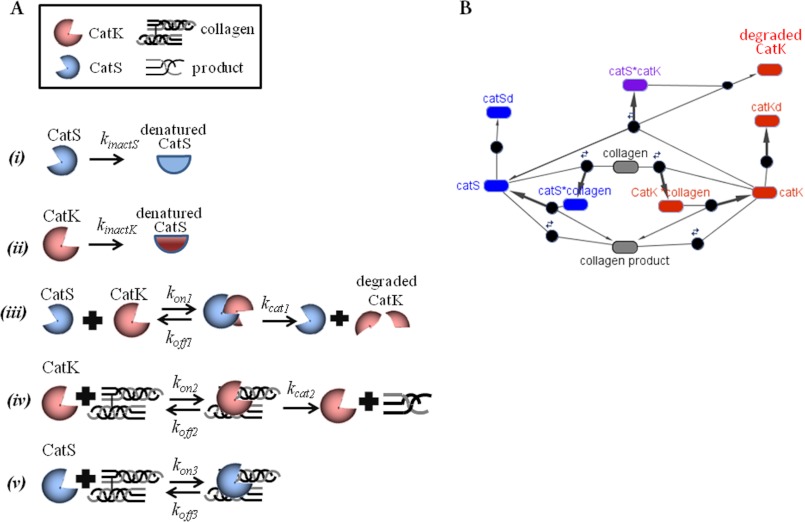

It is the non-intuitive and unexpected activity of these enzymes that has been difficult to monitor in vitro and especially challenging in vivo. Although the bulk contribution of this cathepsin family to overall matrix proteolysis can be measured with E-64 inhibition, it is considerably more difficult to parse out the individual roles of each cathepsin. Knock-out animal models of disease (3, 25) and siRNA experiments (6, 26) have been helpful, but understanding the participation of multiple family members present together in a diseased environment will require computational analysis to understand their individual and interactive proteolytic effects. Toward this goal, we have been able to develop computational models that incorporate cannibalistic reactions of these two cathepsins as they work to hydrolyze elastin or collagen substrates (Fig. 5). This final model details the kinetic reactions occurring simultaneously in these microenvironments. In reactions i and ii, cathepsins K and S are subject to denaturation by still as yet ill defined mechanisms but which probably include autodigestion, denaturation, or inactivation. In reaction iii, cathepsin K is subject to cannibalism by cathepsin S to produce degraded cathepsin K, but while it is mature and active (reaction iv), cathepsin K is capable of binding to triple helical collagen and catalyzing its degradation. In reaction v, active cathepsin S can bind to collagen I, but there is scarce proteolysis. These reactions were used to construct the SimBiology model incorporating the interactions between cathepsins K and S during their co-incubation with ECM substrates and were solved simultaneously as depicted by the schematic in Fig. 5B.

FIGURE 5.

Schematic of cathepsin cannibalism during collagen degradation. A, diagram of the individual reactions describing cathepsin inactivation (reactions i and ii), cathepsin S (CatS) cannibalizing cathepsin K (CatK) (reaction iii), cathepsin K binding to and cleaving collagen I (reaction iv), and cathepsin S binding to but not cleaving collagen I (reaction v). B, schematic of the individual reactions' connectivity and interactions of cathepsins to degrade each other and the substrate protein.

The expansible model framework created here can be extended to predict hydrolytic activity in numerous microenvironments such as ECM degradation by multiple cell types secreting many proteases as seen in tumor environments. As the activity of the individual enzymes alone may not be sufficient to fully explain bulk proteolysis, such a model may lead to a better understanding of how these enzymes work in concert and against each other while generating novel hypotheses to describe proteolytic behavior in vivo under a variety of physiological and pathophysiological conditions.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health New Innovator Grant 1DP2OD007433-01 and by Award DP2OD007433 from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by the Georgia Cancer Coalition, Georgia Institute of Technology startup funds, and the National Science Foundation through Science and Technology Center Emergent Behaviors of Integrated Cellular Systems (EBICS) Grant CBET-0939511.

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- ECM

- extracellular matrix.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shi G. P., Sukhova G. K., Grubb A., Ducharme A., Rhode L. H., Lee R. T., Ridker P. M., Libby P., Chapman H. A. (1999) Cystatin C deficiency in human atherosclerosis and aortic aneurysms. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 1191–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jormsjö S., Wuttge D. M., Sirsjö A., Whatling C., Hamsten A., Stemme S., Eriksson P. (2002) Differential expression of cysteine and aspartic proteases during progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Am. J. Pathol. 161, 939–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lutgens E., Lutgens S. P., Faber B. C., Heeneman S., Gijbels M. M., de Winther M. P., Frederik P., van der Made I., Daugherty A., Sijbers A. M., Fisher A., Long C. J., Saftig P., Black D., Daemen M. J., Cleutjens K. B. (2006) Disruption of the cathepsin K gene reduces atherosclerosis progression and induces plaque fibrosis but accelerates macrophage foam cell formation. Circulation 113, 98–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Platt M. O., Ankeny R. F., Shi G. P., Weiss D., Vega J. D., Taylor W. R., Jo H. (2007) Expression of cathepsin K is regulated by shear stress in cultured endothelial cells and is increased in endothelium in human atherosclerosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292, H1479–H1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sukhova G. K., Shi G. P., Simon D. I., Chapman H. A., Libby P. (1998) Expression of the elastolytic cathepsins S and K in human atheroma and regulation of their production in smooth muscle cells. J. Clin. Invest. 102, 576–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Platt M. O., Ankeny R. F., Jo H. (2006) Laminar shear stress inhibits cathepsin L activity in endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 1784–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sukhova G. K., Zhang Y., Pan J. H., Wada Y., Yamamoto T., Naito M., Kodama T., Tsimikas S., Witztum J. L., Lu M. L., Sakara Y., Chin M. T., Libby P., Shi G. P. (2003) Deficiency of cathepsin S reduces atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 897–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chapman H. A., Riese R. J., Shi G. P. (1997) Emerging roles for cysteine proteases in human biology. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 59, 63–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garnero P., Borel O., Byrjalsen I., Ferreras M., Drake F. H., McQueney M. S., Foged N. T., Delmas P. D., Delaissé J. M. (1998) The collagenolytic activity of cathepsin K is unique among mammalian proteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 32347–32352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kafienah W., Brömme D., Buttle D. J., Croucher L. J., Hollander A. P. (1998) Human cathepsin K cleaves native type I and II collagens at the N-terminal end of the triple helix. Biochem. J. 331, 727–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brömme D., Lecaille F. (2009) Cathepsin K inhibitors for osteoporosis and potential off-target effects. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 18, 585–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Everts V., Korper W., Hoeben K. A., Jansen I. D., Bromme D., Cleutjens K. B., Heeneman S., Peters C., Reinheckel T., Saftig P., Beertsen W. (2006) Osteoclastic bone degradation and the role of different cysteine proteinases and matrix metalloproteinases: differences between calvaria and long bone. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 1399–1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu J., Sukhova G. K., Sun J. S., Xu W. H., Libby P., Shi G. P. (2004) Lysosomal cysteine proteases in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 1359–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirschke H., Wiederanders B., Brömme D., Rinne A. (1989) Cathepsin S from bovine spleen. Purification, distribution, intracellular localization, and action on proteins. Biochem. J. 264, 467–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Novinec M., Kovacic L., Lenarcic B., Baici A. (2010) Conformational flexibility and allosteric regulation of cathepsin K. Biochem. J. 429, 379–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Godat E., Hervé-Grvépinet V., Veillard F., Lecaille F., Belghazi M., Brömme D., Lalmanach G. (2008) Regulation of cathepsin K activity by hydrogen peroxide. Biol. Chem. 389, 1123–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maciewicz R. A., Etherington D. J. (1988) A comparison of four cathepsins (B, L, N, and S) with collagenolytic activity from rabbit spleen. Biochem. J. 256, 433–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Novinec M., Grass R. N., Stark W. J., Turk V., Baici A., Lenarcic B. (2007) Interaction between human cathepsins K, L, and S and elastins: mechanism of elastinolysis and inhibition by macromolecular inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 7893–7902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilder C. L., Park K. Y., Keegan P. M., Platt M. O. (2011) Manipulating substrate and pH in zymography protocols selectively distinguishes cathepsins K, L, S, and V activity in cells and tissues. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 516, 52–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nissler K., Strubel W., Kreusch S., Rommerskirch W., Weber E., Wiederanders B. (1999) The half-life of human procathepsin S. Eur. J. Biochem. 263, 717–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Senior R. M., Griffin G. L., Mecham R. P., Wrenn D. S., Prasad K. U., Urry D. W. (1984) Val-Gly-Val-Ala-Pro-Gly, a repeating peptide in elastin, is chemotactic for fibroblasts and monocytes. J. Cell Biol. 99, 870–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li Z., Hou W. S., Escalante-Torres C. R., Gelb B. D., Bromme D. (2002) Collagenase activity of cathepsin K depends on complex formation with chondroitin sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 28669–28676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hou W. S., Li W., Keyszer G., Weber E., Levy R., Klein M. J., Gravallese E. M., Goldring S. R., Brömme D. (2002) Comparison of cathepsin K and S expression within the rheumatoid and osteoarthritic synovium. Arthritis Rheum. 46, 663–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lecaille F., Brömme D., Lalmanach G. (2008) Biochemical properties and regulation of cathepsin K activity. Biochimie 90, 208–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kitamoto S., Sukhova G. K., Sun J., Yang M., Libby P., Love V., Duramad P., Sun C., Zhang Y., Yang X., Peters C., Shi G. P. (2007) Cathepsin L deficiency reduces diet-induced atherosclerosis in low density lipoprotein receptor knock-out mice. Circulation 115, 2065–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Selinger C. I., Day C. J., Morrison N. A. (2005) Optimized transfection of diced siRNA into mature primary human osteoclasts: inhibition of cathepsin K-mediated bone resorption by siRNA. J. Cell Biochem. 96, 996–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.