Abstract

The anti-angiogenic, carboxy terminal non-collagenous domain (NC1) derived from human Collagen type IV alpha 6 chain, [α6(IV)NC1] or hexastatin, was earlier obtained using different recombinant methods of expression in bacterial systems. However, the effect of L-arginine mediated renaturation in enhancing the relative yields of this protein from bacterial inclusion bodies has not been evaluated. In the present study, direct stirring and on-column renaturation methods using L-arginine and different size exclusion chromatography matrices were applied for enhancing the solubility in purifying the recombinant α6(IV)NC1 from bacterial inclusion bodies. This methodology enabled purification of higher quantities of soluble protein from inclusion bodies, which inhibited endothelial cell proliferation, migration and tube formation. Thus, the scope for L-arginine mediated renaturation in obtaining higher yields of soluble, biologically active NC1 domain from bacterial inclusion bodies was evaluated.

Keywords: Non-collagenous domain of α6 type IV collagen, L-arginine mediated renaturation, Size exclusion chromatography, Anti-angiogenic activity, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells and Vascular endothelial growth factor

1. INTRODUCTION

Type IV collagen is the predominant collagen in vascular basement membranes of blood capillaries [1]. It is organized into a network pattern through head to tail linkage of the individual triple helices, which provide a scaffold for the attachment of endothelial cells (ECs), along with other extracellular matrix proteins [2, 3]. The individual triple helices of type IV collagen are composed of three alpha chains that exist in six isomeric forms, termed as α1–α6 isoforms [4, 5]. Each monomeric α-chain contains a non-collagenous domain (NC1) at its carboxyl-terminus, which facilitates the triple helix and head-to-head link formations [4, 3]. Isolated NC1 domains of type IV collagen [arresten-α1(IV)NC1, canstatin-α2(IV)NC1, tumstatin-α3(IV)NC1 and hexastatin-α6(IV)NC1] were identified to possess anti-angiogenic properties and hence, considered as endogenous angioinhibitors [6–12]. They regulate the angiogenic signaling and EC functions such as proliferation, migration and capillary morphogenesis by binding to the EC receptors [10, 13]. Therefore, type IV collagen derived NC1 domains attained significance for regulation of pathological neovascularization that is evident in tumoral growth and choroidal neovascularization [4, 12, 14–17].

The anti-angiogenic properties of type IV collagen NC1 domains were characterized through cloning and expression of NC1 domain sequences using recombinant expression systems [18, 12, 19–22]. Recombinant NC1 domains expressed in bacteria were purified to homogeneity and they exhibited anti-angiogenic potential both in-vitro and in-vivo [12, 19–22]. However, different recombinant expression systems are under further validation for obtaining higher yields of soluble and purified NC1 domains [16]. The non-collagenous domain of type IV collagen α6 chain [α6(IV)NC1] has a relative molecular mass of 25 kDa in its monomeric form. Recombinant α6(IV)NC1 obtained through expression in bacterial systems exhibited anti-angiogenic properties both in-vitro and in-vivo [12]. It inhibited the proliferation of cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in a dose dependent manner, in-vitro; and also reduced neovascularization and tumor growth in Rip1Tag2 mice tumor models, in-vivo [12].

Expression of recombinant α6(IV)NC1 initially using bacterial system revealed lower yields of soluble α6(IV)NC1, compared to the precipitated form, as reported earlier [12]. We hypothesized that the yields of α6(IV)NC1 can also be enhanced from the bacterial expression systems, without utilizing a soluble fusion tag, by applying suitable renaturation method in purification of α6(IV)NC1 from bacterial inclusion bodies. Thus, the present study was undertaken for evaluating the efficacy of a renaturation method in purification of α6(IV)NC1. Sequential methodology using L-arginine mediated renaturation and size exclusion chromatography (SEC) were applied for obtaining higher yields of soluble α6(IV)NC1 from bacterial expression system, while retaining its anti-angiogenic activities.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from Clonetech™. Sephadex™-G 100, Sephadex™-G 25 and Superdex™-200 were purchased from GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB. BD Matrigel™ Matrix (14.6 mg/ml) was purchased from BD Biosciences Discovery Laboratory. Fetal calf serum (FCS), Endothelial basal medium (EBM-2) and Endothelial cell growth medium (EGM-2) were obtained from Fischer Scientific Inc; recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was obtained from R&D systems, Inc.; penicillin and streptomycin and low melting agarose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and cell stains hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) were purchased from Fischer Scientific Inc. T4-DNA ligase (bacteriophage ligase), different restriction enzymes and polymerases were purchased from New England Biolabs.

2.1. Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were maintained in EGM-2, containing 10% FCS with penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. HUVECs maintained for 2–6 passages were used for all the experiments.

2.2. Cloning and expression of recombinant α6(IV)NC1 domain

The coding sequence corresponding to the C-terminal non-collagenous domain (NC1) from human Collagen type IV α6 chain (NCBI, GenBank ID: EU 182215), was isolated from the placental complementary DNA (cDNA) using one step reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) (Invitrogen, CA). The sequence was amplified using the forward primer: CGGCATATGAGCATGAGAGTGGGCTACACGT and the reverse primer: TCCAAGCTTCAGGCTTTTCATACA (The corresponding restriction sites are italicized and underlined in the primer sequences). Amplification was carried out with an initial melting temperature of 94°C for 4 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C, 30s; 55°C, 30s; 72°C, 60s; with a final extension cycle for 5 min at 72°C. The amplified products were resolved on a 0.8% agarose gel for 60 min at 90 volts (V), and the resulting 690 base pair (bp) amplicon was gel eluted with PREP ease gel extraction kit (USB chemicals, CA). The purified amplicon was digested with Nde I and Hind III and cloned into the Escherichia coli (E. coli) expression vector pET22b that was digested with the same restriction enzymes. The cloned gene was sequenced using T7 forward primer and verified for inframe cloning. The confirmed clone was used to transform E. coli strain BL21 for protein expression and purification.

2.3. Isolation and denaturation of inclusion bodies containing α6(IV)NC1

Inclusion bodies were prepared according to the method of Nagi and Thogerson, 1987 [23], with some modifications. E. coli strain-BL21 expressing the α6(IV)NC1 domain, were cultured in 10 ml of Luria Bertani (LB) medium containing ampicillin. The overnight grown culture was inoculated in 1 L of LB medium with ampicillin and cultured on a shaker incubator at 37°C, until an OD600 of 0.6 was reached and then for 3 hrs by adding Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.7 mM). Bacterial cell pellets were obtained by centrifugation at 2000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Combined pellet from 1 L culture was resuspended in 13 ml of buffer containing 50 mM Tris-hydroxymethyl amino-methane (Tris), 25% sucrose, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.1% sodium azide (NaN3), 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and pH 8.0, followed by sonication for 30 pulses at 4–5 level on ice. The lysate was treated with 100 µl of 50 mg/ml lysozyme, 250 µl of 1% Deoxyribonuclease I (DNAse I) and 50 µl of 0.5 M magnesium chloride (MgCl2), followed by 12.5 ml of lysis buffer [50 mM Tris, 1% Triton × 100, 1% Na deoxycholate, 100 mM sodium chloride (NaCl), 0.1% NaN3, 10 mM DTT, pH 8.0] at room temperature for 30 min. The cell lysate was frozen in liquid nitrogen after adding 350 µl of 0.5 M EDTA. The frozen lysate was thawed at room temperature for 1 hr after adding 200 µl of 0.5 M MgCl2, followed by addition of 350 ml of EDTA (0.5 M), and centrifuged at 11,000 g, for 30 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 10 ml washing buffer with detergent (50 mM Tris, 1% Triton ×100, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% NaN3, 10 mM DTT, pH 8.0) and sonicated on ice followed by centrifugation at 11,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. The pellet was again washed with 10 ml of washing buffer without detergent (50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% NaN3, 10 mM DTT, pH 8.0) and followed by sonication and pelleting to obtain inclusion bodies. Inclusion bodies were dissolved by shaking in 9 ml of 8 M guanidine buffer containing 4 mM DTT, pH 8.0 at room temperature. The dissolved inclusion bodies were aliquoted into 200 µl samples and stored at −80°C until further usage.

2.4. Direct renaturation of denatured α6(IV)NC1 by stirring method

Denatured α6(IV)NC1 protein in 9 ml of guanidine buffer was added as 200 µl aliquots to 200 ml of refolding buffer [50 mM Tris, 200 mM L-arginine, 0.5 mM oxidized glutathione, 5 mM reduced glutathione, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1µM of protease inhibitors, pH 8.0] with continuous stirring initially at room temperature followed by stirring for 1 hr at 4°C. The renatured α6(IV)NC1 protein solution was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4°C and concentrated into a volume of 10 ml with a Millipore filter concentrator.

2.5. On-column renaturation and size exclusion chromatography of α6(IV)NC1

In addition to the renaturation by stirring method, on-column renaturation was performed for simultaneous renaturation and purification of the α6(IV)NC1 protein. Denatured α6(IV)NC1 protein in 800 µl aliquots was loaded onto the Sephadex G-100 column (60×2.5 cm) equilibrated with refolding buffer (composition as mentioned above), connected to the BioLogic LP system (Bio-Rad), and eluted using the same buffer at a constant flow rate of 750 µl/min. Fractions each 1 ml were collected with an automated BioLogic-BioFrac (Bio-Rad) fraction collector, connected to the chromatographic system and the elution chromatogram was recorded using BioLogic-LP view (v1.03) software. Individual fractions obtained from the Sephadex G-100 were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and those fractions (total 10 ml) containing α6(IV)NC1 domain were pooled up for lyophilization and reconstituted to get a final volume of 1 ml using refolding buffer. The re-constituted protein (600 µl) was loaded on Superdex-200 column (50×2.5 cm) and eluted again with the refolding buffer at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The chromatogram was recorded and the individual 1 ml fractions were collected and analyzed through SDS-PAGE. The fractions containing α6(IV)NC1 were pooled (12–14 ml) and further concentrated by lyophilization.

2.6. Desalting by Sephadex G-25 and dialysis of α6(IV)NC1 protein

Lyophilized α6(IV)NC1 fractions obtained from Superdex-200 column were dissolved in 1 ml of refolding buffer and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (1:1), pH 7.8, and loaded on Sephadex G-25 column (60×2.5 cm) equilibrated with 0.1 mM Tris containing PBS, pH 7.8. The column was eluted with same buffer and chromatography was carried out at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The protein fractions corresponding to α6(IV)NC1 were collected and analyzed using SDS-PAGE. Further α6(IV)NC1 desalting was carried out using dialysis. α6(IV)NC1 protein fractions from Sephadex G-25 chromatography were initially dialysed against 2 L of dialysis buffer containing 2.5 mM Tris, 200 mM L-Arginine, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM oxidized glutathione, 5 mM reduced glutathione, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1µM of protease inhibitors, pH 7.6 for 1 h with exchange of buffer for every 15 min, followed by dialysis for 10 hrs by exchanging the buffer containing lower concentrations of L-Arginine without EDTA and glutathione, but increasing the ratio of PBS in the dialysis buffer to 80% and pH 7.5. Final buffer exchange was carried out for 2 hrs with PBS, pH 7.5.

2.7. Estimation of protein concentration and endotoxin levels

Protein estimation was carried out using BCA™ protein estimation method (Pierce) after the dialysis of samples against PBS. Endotoxin levels in the final purified protein samples were estimated using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) QCL-1000 assay kit (Lonza). Concentrations of endotoxin in protein samples were estimated using 96 well microplate method and expressed in endotoxin units/ml (EU/ml) of protein solution according to the manufacturer instructions.

2.8. Proliferation assay

HUVECs cultured to 80% confluence were serum starved for 24 hrs in endothelial basal medium/incomplete medium (EBM-2) with 0.1% FCS followed by trypsinization using trypsin-EDTA. The cells were distributed to a 96 well plate pre-coated with 10 µg/ml of laminin at a density of 5×103 cells/well in EBM-2 and cultured for 24 hrs at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 24 hrs incubation medium was removed from the wells and fresh medium with different compositions were added to the positive, negative and treatment groups as follows. The positive control groups were maintained in EBM-2 containing 10% FCS and 100 U/ml of penicillin and streptomycin, negative control groups were maintained in EBM-2 with 0.1 % FCS and 100 U/ml of penicillin and streptomycin medium, treated groups contained 0.1 and 1.0 µM of purified α6(IV)NC1 and 10 ng/ml of VEGF. Polymyxin B (5 µg/ml) was added to inactivate the endotoxins in the purified protein. Followed by incubation for 48 hrs at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere, the media were removed and cells were washed with PBS. Cells were later fixed in 10% formalin buffered saline for 30 min at room temperature. Fixed cells were then stained with 1% methylene blue in 0.01 M borate buffer (pH, 8.5). Finally, cells were washed thrice with 0.01 M borate buffer and lysed in 100 µl of 0.1 N hydrochloric acid/ethanol (1:1), for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance was recorded at 655 nm using 96 well microplate reader (BioRad, model 680).

2.9. Migration assay

Migration assay was carried out using a 48-well Boyden chamber as reported earlier [3, 14]. HUVECs (1×104 cells/30µl) pre-treated in incomplete media with and without α6(IV)NC1 (0.1 and 1.0 µM) were seeded into each upper well separated by the 8.0 µ polycarbonate membrane from lower wells which contain incomplete medium with 100 ng/ml of VEGF. The chamber was incubated for 24 hr at 37°C with 5% CO2. Incomplete medium with and without VEGF was used as positive and negative control for this migration assay. The number of cells which were migrating and attaching to the underside of the polycarbonate membrane was observed after staining with H&E and through Olympus CK2 light microscope as reported [3].

2.10. Tube formation assay

Tube formation assay was carried out using matrigel matrix in a 24 well plate [3, 14]. Briefly, matrigel matrix was thawed overnight at 4°C and aliquots of 250 µl were added to each well of 24 well culture plates and allowed to ploymerize at 37°C for about 30 min. Suspensions of 5×104 HUVECs in EGM-2 (without antibiotics) were seeded on to the top of matrigel. The cells were treated with or without 0.1 and 1.0 µM purified α6(IV)NC1, EGM-2 medium alone used as negative control. After 48 hr incubation of HUVECs at 37°C, tube formation was observed using Olympus CK2 light microscope as reported [3, 14].

3. RESULTS

3.1 Expression and denaturation of recombinant α6(IV)NC1

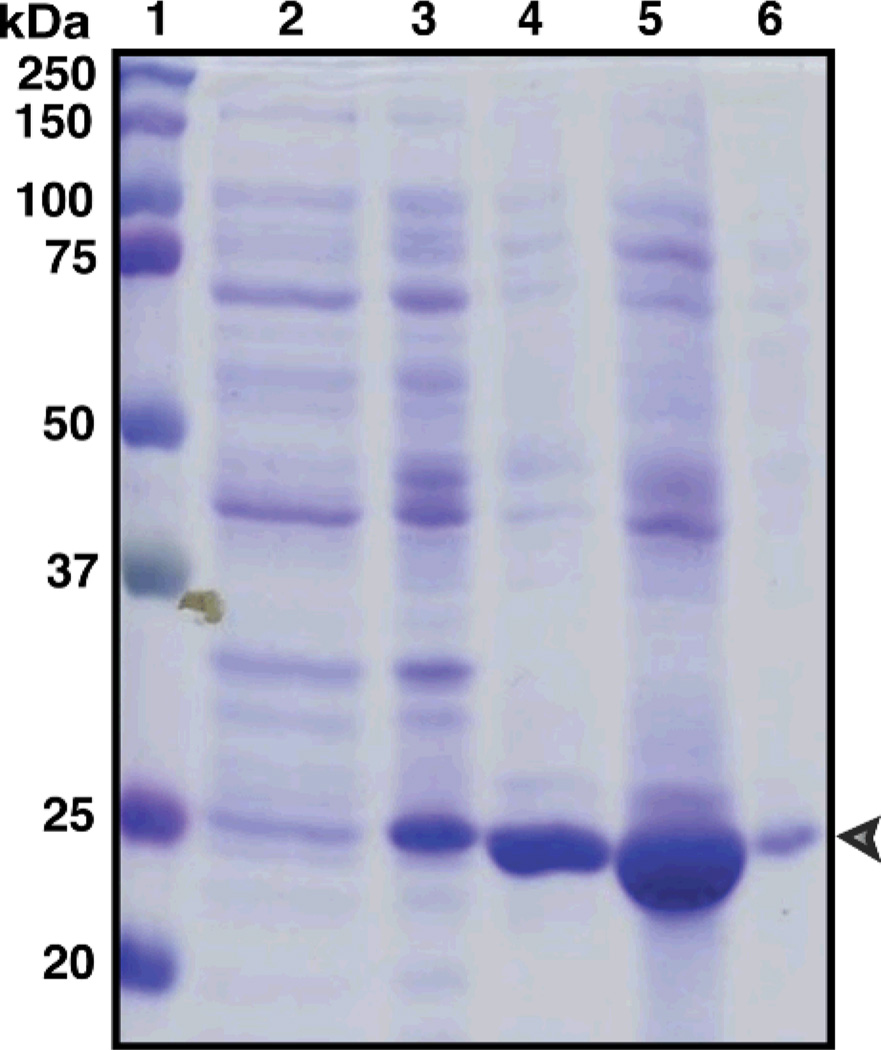

The amino acid sequence of the human α6(IV)NC1 domain (UniProt ID: Q14031) indicates that it is comprised of 225 amino acids with 6 disulfide bonds and an approximate molecular mass (Mr) of 25 kDa. In the present study, the sequence coding for the α6(IV)NC1 domain was amplified and the sequence comparison revealed similarity of the amplified and the published α6(IV)NC1 sequences. Further, SDS-PAGE analysis of the protein extracts from the IPTG induced E. coli transformed with the recombinant expression vector pET22b containing inframe cloned α6(IV)NC1 sequence, showed the induction of a band corresponding to Mr of 25 kDa, indicating over expression of α6(IV)NC1 with IPTG (Fig. 1, lane-3). Further, guanidine mediated denaturation was applied for solubilization and denaturation of inclusion bodies containing α6(IV)NC1 protein in the present methodology. Inclusion bodies were completely solubilized in 6 M guanidine buffer at pH. 8.0, and SDS-PAGE analysis revealed the retention of α6(IV)NC1 protein within the inclusion bodies (Fig. 1, lane-4).

Figure 1. Expression, denaturation and renaturation of α6(IV)NC1.

Lanes: 1-Marker, 2-Uninduced cell proteins, 3-Induced cell proteins, 4-Inclusion bodies denatured in guanidine buffer, 5-protein solubilized in arginine buffer by direct stirring, 6-protein from pellet after direct stirring renaturation [α6(IV)NC1 band apparent at 25 kDa].

3.2. L-Arginine mediated direct stirring promotes solubilization of recombinant α6(IV)NC1 protein

Renaturation of guanidine-solubilized inclusion bodies by direct stirring resulted in clear solution with higher quantity of soluble recombinant α6(IV)NC1 (7.5 mg/L of culture) than in the precipitate (2.2 mg/L) that was formed during the stirring process (Table. 1). The presence of soluble α6(IV)NC1 protein in denatured and renatured protein samples was also confirmed using SDS-PAGE analyses (Fig. 1, lanes 5 & 6).

Table 1.

Relative yields of α6(IV)NC1 protein obtained during purification process.

| Purification step | Quantity of protein (mg/L of E. coli culture) |

|---|---|

| Renaturation by direct stirring (soluble) | 7.5 |

| Renaturation by direct stirring (insoluble) | 2.2 |

| Sephadex-G 100 elution | 8.046 |

| Superdex-200 elution | 7.175 |

| Desalting and dialysis | 7.105 |

3.3. Purification and refolding of α6(IV)NC1 using size exclusion chromatography

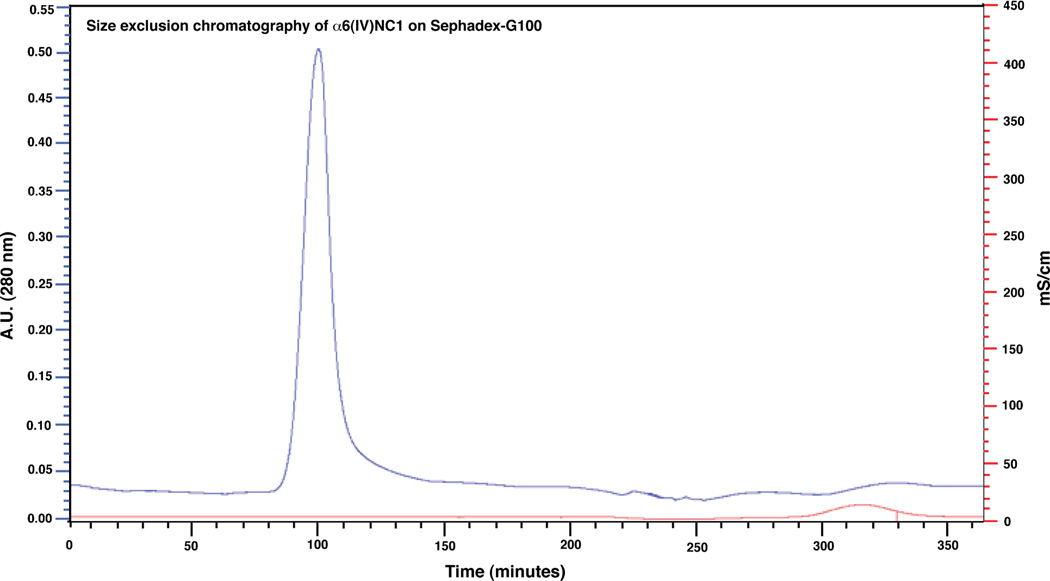

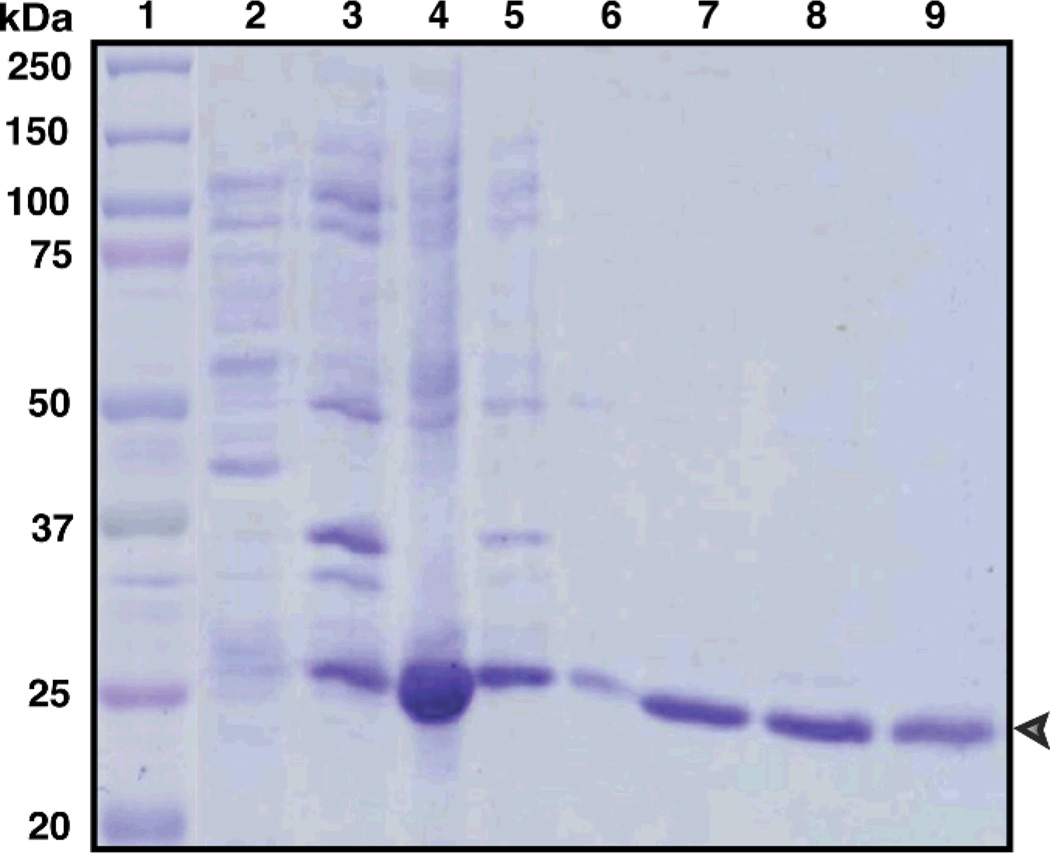

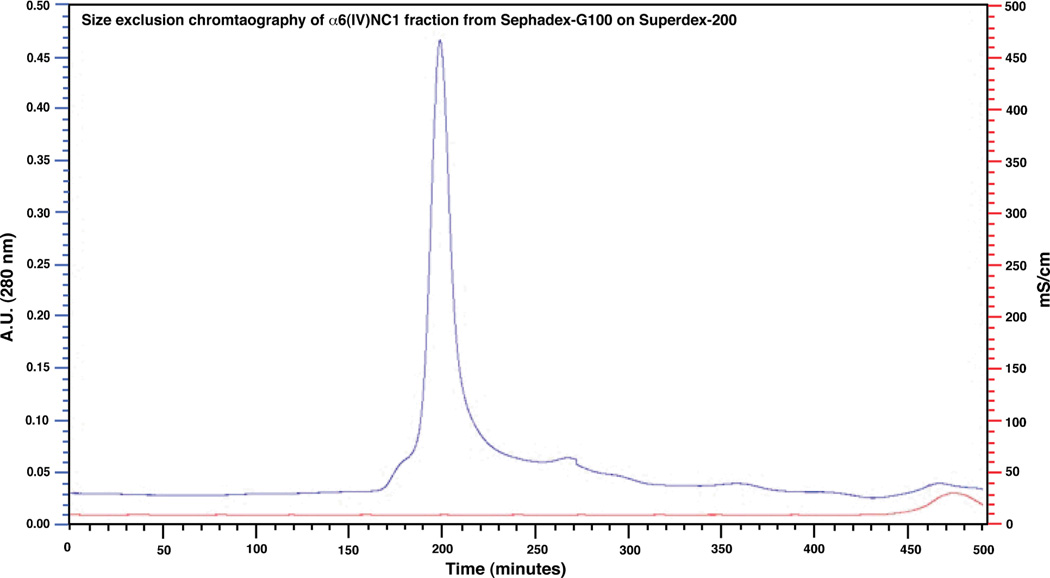

Though, direct stirring method of denatured α6(IV)NC1 revealed the solubility of α6(IV)NC1 in the buffer, many contaminating proteins were evident in the soluble fraction through SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 1). Therefore, column chromatography methods were applied for further purification of α6(IV)NC1. The chromatogram obtained during Sephadex-G 100 chromatography revealed the elution of α6(IV)NC1 in the renaturation buffer (85–105 min). The renaturation buffer also contained oxidized and reduced glutathione similar to the buffer applied in direct stirring method to facilitate refolding of the protein. The separation of the denaturing agent guanidine from the renaturing protein was also revealed by the increase in conductivity of the elution buffer after 280 min of chromatography (Fig. 2). Analysis of the concentrated α6(IV)NC1 fraction eluted from the Sephadex-G100 on SDS-PAGE revealed the presence of high molecular weight proteins (>25 kDa) as co-elutents along with α6(IV)NC1 (Fig. 5, lane 4). Further chromatography of the fractions containing α6(IV)NC1 protein on Superedx-200 was performed to purify the α6(IV)NC1 to its homogeneity. Chromatogram obtained for the α6(IV)NC1 purification, in the present study using Superdex-200, (Fig. 3) revealed few minor peaks and a single major peak between 175 and 205 min. SDS-PAGE analyses showed the elution of high molecular weight proteins (> 25 kDa) in the fractions before 175 min (Fig. 5: lane 5), and elution of pure α6(IV)NC1 (> 95% purity) as the major peak between 195–205 min (Fig. 5, lane 7).

Figure 2. Chromatogram showing elution pattern of α6(IV)NC1 from Sephadex-G 100.

Major peak of absorbance at 280 nm indicates elution of α6(IV)NC1 fraction. [Elution of protein is evident with major peak absorbance at 280 nm (upper curve) and the salts as increase in conductivity peaks (lower curve) respectively].

Figure 5. SDS-PAGE analysis of α6(IV)NC1 purification profile using L-arginine renaturation and column chromatography methods.

Lanes: 1-Marker, 2–4: fractions from Sephadex G-100 (2:65–75 min, 3:75–85 min, 4:95–105min), 5–7: fractions from superedx-200 (5:165–175, 6:175–185min, 7:195–205min), 8: Fraction from desalting on sephadex G-25 (35–40min), 9-dilaysed α6(IV)NC1.

Figure 3. Chromatogram showing elution pattern of α6(IV)NC1 from Superdex-200.

Major peak of absorbance at 280 nm indicates elution of pure α6(IV)NC1 and minor peaks indicate elution of contaminating proteins. [Elution of protein is evident with major peak absorbance at 280 nm (upper curve) and the salts as increase in conductivity peaks (lower curve) respectively].

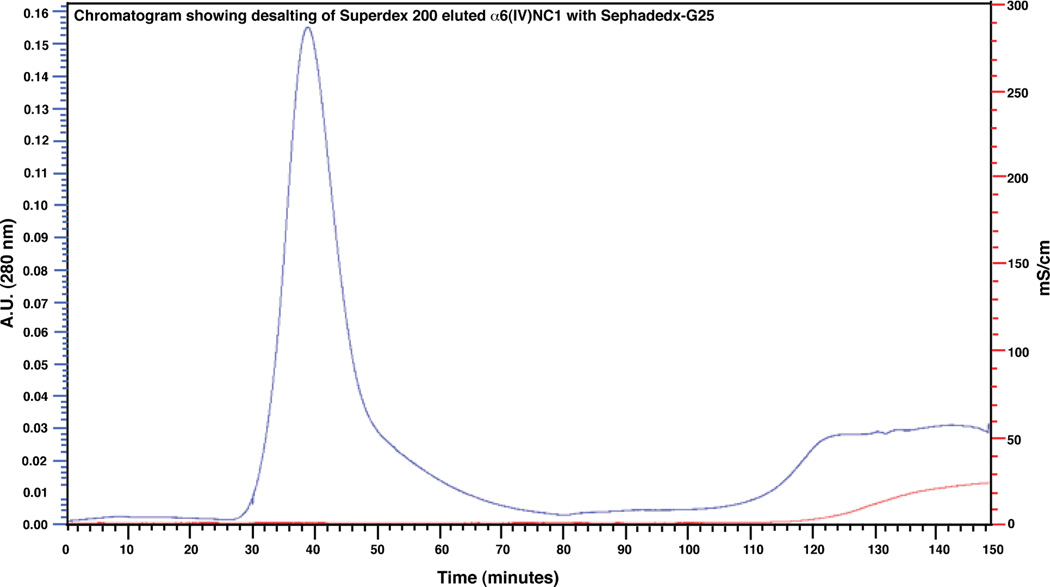

3.4. Desalting of renatured α6(IV)NC1 from Superdex-200 on Sephadex G-25

Desalting of the purified α6(IV)NC1 was carried out on Sephadex-G 25 matrix using the phosphate buffered saline of pH 7.8. The pH of the buffer used for elution was maintained slightly above the neutral range for preventing the denaturation of purified α6(IV)NC1 protein. The chromatogram obtained from desalting on Sephadex-G 25 exhibited a major peak between 30–60 min (Fig. 4), indicating the elution of α6(IV)NC1 in this interval as revealed by the corresponding band from SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 5, lane 8). Another broad peak with considerable increase in absorbance at 280 nm was also observed after 110 min which indicated the elution of L-arginine with other salts as reflected by the increase in conductivity within this interval of elution (Fig. 4, peak in lower curve after 110 min). The eluted protein from Sephadex-G 25 was further subjected to dialysis to remove any traces of salts and L-arginine from the α6(IV)NC1 fraction. Initially dialysis was carried out against the PBS containing L-arginine, glutathione and EDTA to prevent aggregation or precipitation of the protein followed by gradual changing of PBS with pH, 7.5 to obtain α6(IV)NC1 without contamination. Thus with dialysis, about 98% purity of α6(IV)NC1 was obtained in PBS for further biological evaluations (Fig. 5, lane 9).

Figure 4. Chromatogram showing desalting of purified α6(IV)NC1 on Sephadex-G 25.

Major peak of absorbance at 280 nm indicates elution of pure α6(IV)NC1 and broad peak after 110 min indicates elution of L-arginine. [Elution of protein or amino acid is evident with increase in peak absorbance at 280 nm (upper curve) and that of salts as increase in conductivity peaks (lower curve) respectively].

3.5. L-Arginine mediated renaturation yields relatively higher quantities of soluble α6(IV)NC1

Quantification of the protein content in the dialyzed samples obtained from different steps of purification in the present method show relatively higher yields of the soluble, recombinant α6(IV)NC1 (Table. 1). The amount of soluble protein was relatively higher in the Sephadex-G 100 fractions compared to other. However, the purity of α6(IV)NC1 increased with a slight decrease in the yield with further chromatography using Superdex-200.

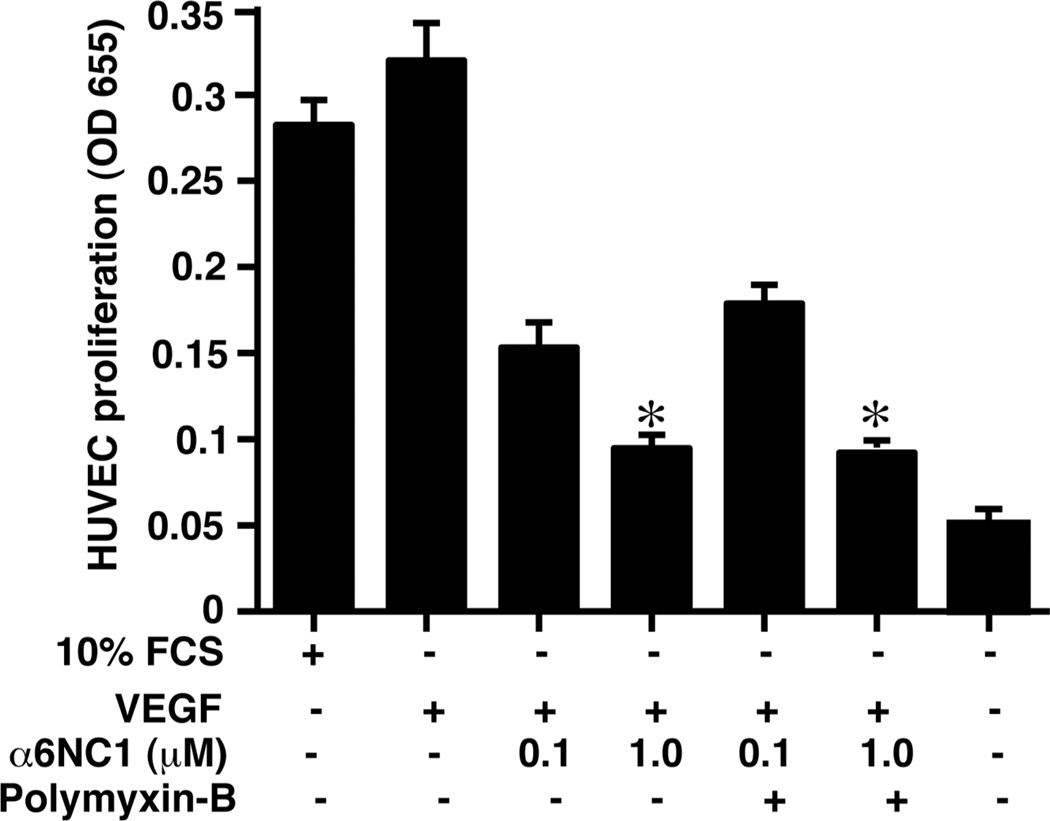

3.6. Distinct anti-angiogenic activities of recombinant α6(IV)NC1 on HUVECs

We have conducted a series of in vitro, angiogenesis experiments to define the anti-angiogenic activity of α6(IV)NC1 using HUVECs. First the anti-proliferative effect of α6(IV)NC1 was examined using methylene blue assays. Recombinant α6(IV)NC1 purified in the present study using the renaturation and SEC methods, exhibited anti-proliferative effect on cultured HUVECs that were stimulated with VEGF in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 6). The anti-proliferative effect of α6(IV)NC1 was similar in presence and absence of polymyxin-B (5 µg/ml,) indicating that the observed anti-proliferative effect on HUVECs was due to the α6(IV)NC1 rather than the endotoxins. Thus, the purified α6(IV)NC1 was active in inhibiting HUVEC proliferation at 0.1 and 1.0 µM concentrations (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Anti-proliferative effect of purified α6(IV)NC1 on HUVECs.

Proliferation was assessed using methylene blue uptake assay of HUVECs treated for 48 hrs with (0.1 and 1 µM) and without α6(IV)NC1. Ploymyxyin B (5 µg/ml) was added to neutralize the endotoxin effect on the cells. Graph shows decrease in cell viability of HUVECs with increase in α6(IV)NC1 concentrations. 10% FCS is the positive control. Bars represent SEM for three replicates (* indicates significant difference P<0.05).

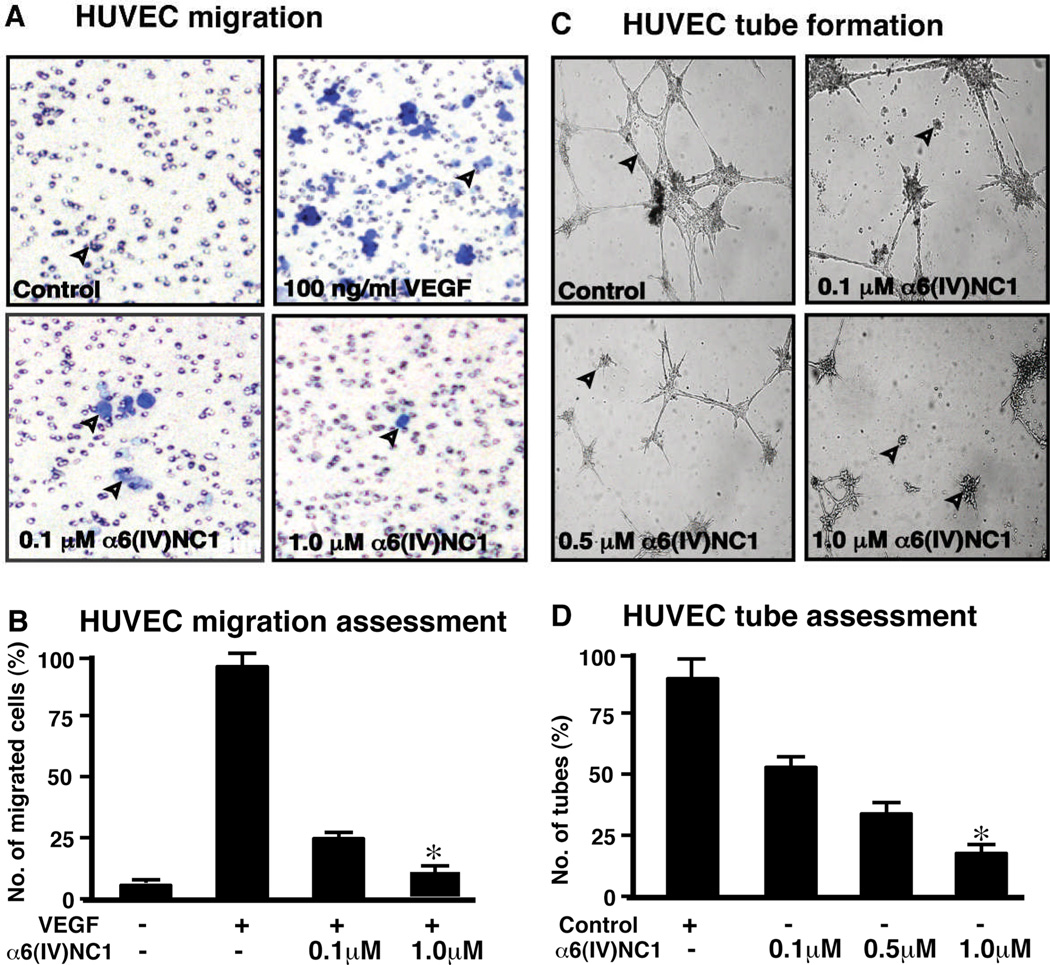

Migration of ECs through a laminin coated membrane towards VEGF in a Boyden chamber is significantly inhibited by α6(IV)NC1 (Fig 7A, left panel). The number of migrating cells decreased with increase of the α6(IV)NC1 concentration (Fig. 7B). Finally, we confirmed the anti-angiogenic activity of α6(IV)NC1 by the functional assay of tube formation. Addition of different concentrations of α6(IV)NC1 to the HUVEC culture media significantly inhibited EC tube formation on matrigel matrix, indicating the anti-angiogneic effects of this recombinant protein (Fig. 7C) with the decrease number of tubes on treatment with α6(IV)NC1 (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7. Inhibition of HUVEC migration and tube formation by α6(IV)NC1.

(A) Migration assay: Photographs showing HUVECs from the underside of Boyden chamber membrane. Control indicates cells migrating in incomplete medium pointed out by arrow heads, 100 ng/ml of VEGF was used as a positive control in which relatively higher number of cells exhibited migration, migration was reduced on treatment with 0.1 and 1.0 µ M α6(IV)NC1 (Fields represent 5 of the replicates as observed at 200× magnification with Olympus CK2 light microscope. (B) Migration assessment: Graph displays average number of cells migrating in three independent experiments. (C) Tube formation assay: Tube formation was evaluated after 48 hrs on Matrigel matrix with and without 0.1 and 1.0 µ M α6(IV)NC1. Tube formation was visualized with Olympus CK2 light microscope and representative fields at 100× magnification are shown. Arrowheads indicate the tubes in control and clumps formed in treated wells. (D) Graphical representation of tube formation. Graph summarizes the percentage of average numbers of tubes formed from 3 independent experiments (error bars in panels B and C indicate SEM & * indicates significant difference P<0.05).

4. Discussion

Bacterial expression systems enable expression of higher quantities of recombinant proteins compared to other systems [14, 24]. Such over expression leads to the sequestration of recombinant proteins into inclusion bodies which facilitate partial isolation of recombinant proteins from other cellular components but mostly in insoluble form [25]. In the present study, inclusion bodies were isolated from the bacterial cell pellet by lysis and freeze-thawing the bacterial cells expressing α6(IV)NC1 in liquid nitrogen, followed by gradual centrifugation and washing procedures [23]. This method enabled the isolation of inclusion bodies with accumulated recombinant α6(IV)NC1 protein. Inclusion bodies are generally insoluble and chaotropic reagents such as guanidine or urea are used for enhancing their solubility, which results in the denaturation of the recombinant proteins [26]. Denaturation leads to the loss of native conformation and functional properties of proteins. Refolding or renaturation of the denatured proteins is therefore essential for obtaining any functional proteins, which can be revealed through the retention of biological activities by those proteins [24–26]. Improper renaturation or refolding of the recombinant proteins can also lead to aggregation of the proteins during their purification process resulting in loss of recombinant proteins as precipitates [27]. Therefore, effective methods of renaturation are considered to prevent the aggregation of E. coli expressed proteins by promoting the refolding of recombinant proteins. L-arginine mediated renaturation has been shown to be an effective method for renaturation of the recombinant proteins of human origin expressed in heterologous systems [14, 28–30]. The positive effects of L-arginine mediated renaturation include proper refolding of the intermediates, prevention of the protein aggregation during renaturation, high yields of recombinant protein from inclusion bodies and retention of the biological activities, as reported [31–33]. Methodologies including direct stirring on-column renaturation and dialysis of denatured protein against refolding buffers were applied for protein renaturation using L-arginine [34–37]. Here in this study, the efficacy of L-arginine mediated renaturation of α6(IV)NC1 was initially evaluated by using direct stirring method for renaturation of denatured α6(IV)NC1.

The yield of soluble α6(IV)NC1 was also higher compared to a previous studies, in which the yields of soluble recombinant proteins were relatively lower when expressed in bacterial systems as His-tagged proteins [12, 14]. The higher solubility of the recombinant α6(IV)NC1 in the present study might be due to the positive effects of L-arginine and the inclusion of oxidized and reduced glutathiones in the renaturation buffer. Oxidized and reduced glutathiones are utilized in the purification methods to promote the formation of disulfide linkages and retention of native conformations by the recombinant proteins [27]. The amino acid sequence corresponding to the α6(IV)NC1 (UniProt ID: Q14031), indicates the presence of 6 disulfide bonds within this domain. Therefore, it can be ascertained that the inclusion of oxidized and reduced glutathione have facilitated the renaturation and solubility of α6(IV)NC1.

On-column renaturation methods along with size exclusion facilitate simultaneous renaturation and purification of the recombinant proteins [30, 34, 35]. In the present study step wise SEC methods using Sephadex-G100 and Superdex 200 were employed for the purification of recombinant α6(IV)NC1. Initial SEC of denatured α6(IV)NC1 protein with Sephadex-G100 matrix using renaturation buffer was applied for the solubilization or exchange of the protein into renaturation buffer and partial purification was obtained in this step. Superdex-200 is a superfine matrix that was applied for purification and screening the purity of proteins [28, 38]. Pure fraction of α6(IV)NC1 was obtained in the second step of SEC using Superdex-200 matrix. Dialysis and desalting resulted in pure protein, with low endotoxin levels and the endotoxin levels in the final protein preparation were very low (0.119 EU/ml) compared to other reports. The method followed in the present study has shown increase in the yields of soluble extra cellular matrix type IV collagen protein domain for one liter of the cultured cells, compared to a previous method in which relatively lower yields of soluble proteins were obtained using metal affinity chromatography method [12, 14]. The purity of the α6(IV)NC1 evaluated using SDS-PAGE analyses in the present study also shows purification of α6(IV)NC1 to greater than 98% after Superdedx-200 chromatography. Thus, the present method is beneficial in obtaining higher yields of soluble α6(IV)NC1 from inclusion bodies without utilizing a soluble tag. Further, the method also yielded α6(IV)NC1 with anti-angiogenic activities as evaluated using in vitro systems. Migration of ECs has been shown to have an important role in neovascularization [39]. Tube formation by endothelial cells also involves endothelial cell migration, proliferation and survival [3, 39]. α6(IV)NC1 purified using renaturation inhibited proliferation, migration and tube formation by EC’s in a dose dependent manner. Thus, the present methodology of solubilization enhanced the yields of biologically active α6(IV)NC1 which can be further applied for purification of α6(IV)NC1 and other NC1 domains for evaluating the mechanisms associated with their anti-angiogenic activities.

In conclusion, the method of L-arginine mediated renaturation with simultaneous size exclusion chromatography, applied in the present study, is validated to be effective for purification of recombinant, human α6(IV)NC1 from bacterial inclusion bodies by retaining the anti-angiogenic properties. α6(IV)NC1 was reported to exhibit potent anti-angiogenic/anti-tumorogenic activities, thus purification of soluble protein in higher quantities is essential for its evaluation using in-vitro and in-vivo studies. Since, the efficacy of the present methodology is reflected form the increase in the yields of the biologically active α6(IV)NC1 from inclusion bodies, it may be applied for the purification of other NC1 domains derived from type IV collagen, to enhance their yields from bacterial inclusion bodies, by optimization of the present methodology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute Young Clinical Scientist Award Grant FAMRI-062558, NIH/NCI grant RO1CA143128, Dobleman Head and Neck Cancer Institute grant DHNCI-61905 and startup research funds of Cell Signaling, Retinal and Tumor Angiogenesis Laboratory at Boys Town National Research Hospital to YAS and 1R15GM080681-01 to CG.

Footnotes

Authors Contribution: V.G., expressed, purified α6(IV)NC1 protein and/or performed all the studies and wrote the manuscript; C.S.B., cloned and expressed α6(IV)NC1 protein; R.K.V., performed α6(IV)NC1 purification studies; C.G., design and analyses of data; YAS conception, design, execution and analyses of the studies and wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Timpl R. Macromolecular organization of basement membranes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8(5):618–624. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timpl R, Wiedemann H, van Delden V, Furthmayr H, Kuhn K. A network model for the organization of type IV collagen molecules in basement membranes. Eur J Biochem. 1981;120(2):203–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudhakar A, Sugimoto H, Yang C, Lively J, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Human tumstatin and human endostatin exhibit distinct antiangiogenic activities mediated by alpha v beta 3 and alpha 5 beta 1 integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(8):4766–4771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730882100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 4.Hamano Y, Zeisberg M, Sugimoto H, Lively JC, Maeshima Y, Yang C, Hynes RO, Werb Z, Sudhakar A, Kalluri R. Physiological levels of tumstatin, a fragment of collagen IV alpha3 chain, are generated by MMP-9 proteolysis and suppress angiogenesis via alphaV beta3 integrin. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(6):589–601. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00133-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prockop DJ, Kivirikko KI. Collagens: molecular biology, diseases, and potentials for therapy. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:403–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colorado PC, Torre A, Kamphaus G, Maeshima Y, Hopfer H, Takahashi K, Volk R, Zamborsky ED, Herman S, Sarkar PK, Ericksen MB, Dhanabal M, Simons M, Post M, Kufe DW, Weichselbaum RR, Sukhatme VP, Kalluri R. Anti-angiogenic cues from vascular basement membrane collagen. Cancer Res. 2000;60(9):2520–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeshima Y, Colorado PC, Torre A, Holthaus KA, Grunkemeyer JA, Ericksen MB, Hopfer H, Xiao Y, Stillman IE, Kalluri R. Distinct antitumor properties of a type IV collagen domain derived from basement membrane. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(28):21340–21348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001956200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamphaus GD, Colorado PC, Panka DJ, Hopfer H, Ramchandran R, Torre A, Maeshima Y, Mier JW, Sukhatme VP, Kalluri R. Canstatin, a novel matrix-derived inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(2):1209–1215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petitclerc E, Boutaud A, Prestayko A, Xu J, Sado Y, Ninomiya Y, Sarras MP, Jr, Hudson BG, Brooks PC. New functions for non-collagenous domains of human collagen type IV. Novel integrin ligands inhibiting angiogenesis and tumor growth in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(11):8051–8061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boosani CS, Mannam AP, Cosgrove D, Silva R, Hodivala-Dilke KM, Keshamouni VG, Sudhakar A. Regulation of COX-2 mediated signaling by alpha3 type IV noncollagenous domain in tumor angiogenesis. Blood. 2007;110(4):1168–1177. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-066282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalluri R. Discovery of type IV collagen non-collagenous domains as novel integrin ligands and endogenous inhibitors of angiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2002;67:255–266. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2002.67.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mundel TM, Yliniemi AM, Maeshima Y, Sugimoto H, Kieran M, Kalluri R. Type IV collagen alpha6 chain-derived noncollagenous domain 1 (alpha6(IV)NC1) inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(8):1738–1744. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sudhakar A, Boosani CS. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by tumstatin: insights into signaling mechanisms and implications in cancer regression. Pharm Res. 2008;25(12):2731–2739. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9634-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 14.Boosani CS, Nalabothula N, Munugalavadla V, Cosgrove D, Keshamoun VG, Sheibani N, Sudhakar A. FAK and p38-MAP kinase-dependent activation of apoptosis and caspase-3 in retinal endothelial cells by alpha1(IV)NC1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(10):4567–4575. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 15.Ortega N, Werb Z. New functional roles for non-collagenous domains of basement membrane collagens. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(22):4201–4214. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boosani CS, Nalabothula N, Sheibani N, Sudhakar A. Inhibitory effects of arresten on bFGF-induced proliferation, migration, and matrix metalloproteinase-2 activation in mouse retinal endothelial cells. Curr Eye Res. 2010;35(1):45–55. doi: 10.3109/02713680903374208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Boosani CS, Sudhakar YA. Proteolytically derived endogenous angioinhibitors originating from the extracellular matrix. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2011;4(12):1551–1577. doi: 10.3390/ph4121551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boosani CS, Sudhakar A. Cloning, purification, and characterization of a non-collagenous antiangiogenic protein domain from human alpha1 type IV collagen expressed in Sf9 cells. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;49(2):211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang X, Wong MK, Zhao Q, Zhu Z, Wang KZ, Huang N, Ye C, Gorelik E, Li M. Soluble recombinant endostatin purified from Escherichia coli: antiangiogenic activity and antitumor effect. Cancer Res. 2001;61(2):478–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li ZS, He XP, Tu ZX, Gao J, Pan X, Gong YF, Jin J. Cloning of human canstatin gene and expression of its recombinant protein. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2005;27(5):587–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu Q, Zhang T, Luo J, Wang F. Expression, purification, and bioactivity of human tumstatin from Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;47(2):461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song Z, Qichang Z, Li W, Xiong J, Shang D, Shu X. Prokaryotic expression and biological activity analysis of human arresten gene. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2005;25(1):8–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02831373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagai K, Thogersen HC. Synthesis and sequence-specific proteolysis of hybrid proteins produced in Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1987;153:461–481. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)53072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laage R, Langosch D. Strategies for prokaryotic expression of eukaryotic membrane proteins. Traffic. 2001;2(2):99–104. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.020204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayer M, Buchner J. Refolding of inclusion body proteins. Methods Mol Med. 2004;94:239–254. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-679-7:239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsumoto K, Ejima D, Kumagai I, Arakawa T. Practical considerations in refolding proteins from inclusion bodies. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;28(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(02)00641-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark EDB. Refolding of recombinant proteins. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1998;9(2):157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(98)80109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouellette T, Destrau S, Zhu J, Roach JM, Coffman JD, Hecht T, Lynch JE, Giardina SL. Production and purification of refolded recombinant human IL-7 from inclusion bodies. Protein Expr Purif. 2003;30(2):156–166. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(03)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hua ZC, Dong C, Zhu DX. Enhancement of in vitro renaturation of recombinant human pro-urokinase by ampicillin. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1996;39(6):1093–1097. doi: 10.1080/15216549600201262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang XT, Engel PC. An optimised system for refolding of human glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase. BMC Biotechnol. 2009;9:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-9-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Callaghan CA, Tormo J, Willcox BE, Blundell CD, Jakobsen BK, Stuart DI, McMichael AJ, Bell JI, Jones EY. Production, crystallization, and preliminary X-ray analysis of the human MHC class Ib molecule HLA-E. Protein Sci. 1998;7(5):1264–1266. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinle A, Li P, Morris DL, Groh V, Lanier LL, Strong RK, Spies T. Interactions of human NKG2D with its ligands MICA, MICB, and homologs of the mouse RAE-1 protein family. Immunogenetics. 2001;53(4):279–287. doi: 10.1007/s002510100325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsumoto K, Umetsu M, Kumagai I, Ejima D, Philo JS, Arakawa T. Role of arginine in protein refolding, solubilization, and purification. Biotechnol Prog. 2004;20(5):1301–1308. doi: 10.1021/bp0498793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiu FF, Venkatesan N, Wu CR, Chou AH, Chen HW, Lian SP, Liu SJ, Huang CC, Lian WC, Chong P, Leng CH. Immunological study of HA1 domain of hemagglutinin of influenza H5N1 virus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;383(1):27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.03.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li M, Su ZG, Janson JC. In vitro protein refolding by chromatographic procedures. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;33(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suenaga M, Ohmae H, Tsuji S, Itoh T, Nishimura O. Renaturation of recombinant human neurotrophin-3 from inclusion bodies using a suppressor agent of aggregation. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 1998;28(2):119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reddy KR, Lilie H, Rudolph R, Lange C. L-Arginine increases the solubility of unfolded species of hen egg white lysozyme. Protein Sci. 2005;14(4):929–935. doi: 10.1110/ps.041085005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salomonson I, Zou J, Carlsson M, Bergh A, Lundstrom F. Rapid screening of antibody aggregates and protein impurities using short gel filtration columns. J Biomol Tech. 2009;20(5):282–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sudhakar A, Nyberg P, Keshamouni VG, Mannam AP, Li J, Sugimoto H, Cosgrove D, Kalluri R. Human alpha1 type IV collagen NC1 domain exhibits distinct antiangiogenic activity mediated by alpha1beta1 integrin. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(10):2801–2810. doi: 10.1172/JCI24813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]