Abstract

The use of drugs for recreational purposes, in particular Methamphetamine, is associated with an increased risk of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1. HIV-1 infection in turn can lead to HIV-associated neurological disorders (HAND) that range from mild cognitive and motor impairment to HIV-associated dementia (HAD). Interestingly, post mortem brain specimens from HAD patients and transgenic (tg) mice expressing the viral envelope protein gp120 in the central nervous system display similar neuropathological signs. In HIV patients, the use of Methamphetamine appears to aggravate neurocognitive alterations. In the present study, we injected HIV/gp120tg mice and non-transgenic littermate control animals with Methamphetamine dissolved in Saline or Saline vehicle and assessed locomotion and stereotyped behaviour. We found that HIVgp120-transgenic mice differ significantly from non-transgenic controls in certain domains of their behavioural response to Methamphetamine. Thus this experimental model system may be useful to further study the mechanistic interaction of both the viral envelope protein and the psychostimulant drug in behavioural alterations and neurodegenerative disease.

Keywords: Methamphetamine, HIV, envelope protein, behaviour, stereotypy, neurodegeneration, drug abuse

1. Introduction

Infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 can lead to HIV-associated neurological disorders (HAND) that range from mild cognitive and motor impairment to fulminant HIV associated dementia (HAD) (Antinori et al., 2007). The pathologic mechanism of brain injury and dementia remains poorly understood, but post mortem brain specimens from HAD patients and transgenic (tg) mice expressing the HIV envelope protein gp120 in the central nervous system present with similar neuropathological signs (Toggas et al., 1994). Those shared pathological features include decreased synaptic and dendritic density, astrocytosis and activated microglia in cortex and hippocampus, and impaired hippocampal neurogenesis (Toggas et al., 1994; Okamoto et al., 2007). HIV/gp120tg mice also develop significant physiological and behavioural changes, such as reduced escape latency, swimming velocity and spatial retention at 12 month of age (Krucker et al., 1998; D'hooge et al., 1999). The relevance of this transgenic model is further supported by the finding that neuronal damage initiated by HIV-infected human macrophages intracerebrally administered into mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) also closely resembles the neuropathology of human acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome (AIDS) brains and gp120tg mice (Persidsky et al., 1996). Furthermore, in vitro and in vivo, HIV gp120 produces injury and apoptosis in both primary rodent and human neurons (Kaul et al., 2001).

The use of recreational drugs, in particular Methamphetamine, is associated with a great risk of HIV-1 infection (Urbina and Jones, 2004). In humans, use of Methamphetamine triggers behavioural symptoms, including agitation, anxiety, paranoia, psychosis and aggression, and apparently increases the willingness to engage in high-risk activities, such as unprotected sexual interaction with HIV-1 infected partners (Urbina and Jones, 2004). Neurocognitive sequelae of Methamphetamine abuse include deficits in attention, working memory and executive functions (Cadet and Krasnova, 2007; Scott et al., 2007). One very obvious effect of acute Methamphetamine exposure is the induction of repetitive behavioural patterns, which are commonly referred to as stereotypies and are induced by the drug in both humans and animals (Randrup et al., 1988). Mechanistically Methamphetamine compromises several neurotransmitter systems, including those based on dopamine and serotonin, induces hypertension and hyperthermia, and interferes with the body’s immune defence (Cadet and Krasnova, 2007; Scott et al., 2007; Talloczy et al., 2008).

In combination, Methamphetamine and HIV-1 appear to cause more neurocognitive deficits than each agent alone, but the interaction of both the virus and the drug is poorly understood (Rippeth et al., 2004; Cadet and Krasnova, 2007). Here we show that HIVgp120-transgenic mice, which express the viral envelope protein in the central nervous system, differ from non-transgenic controls in their stereotypic behavioural response to Methamphetamine, thus providing in vivo experimental evidence that HIV can affect the brain’s response to the psychostimulant drug.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Mice, drug treatment and behavioural testing

In the present study, we injected twenty age-matched 9 to 13 month-old HIV/gp120tg mice and non-transgenic littermate control animals (WT) (Toggas et al., 1994) with Saline (vehicle) or Methamphetamine (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, WA) dissolved in Saline and assessed locomotion and stereotyped behaviour (Randrup et al., 1988). Methamphetamine was applied in increasing doses of 1, 5, 10 and 30 mg/kg i.p., for a total of 4 applications across a 2 month period. Saline was injected and its effect assessed as control prior to the different Methamphetamine treatments. The animals were allowed one week recovery between each of the first three rounds of Saline and Methamphetamine and a three week break before the last 30 mg/kg Methamphetamine application. Following injection with Saline or Methamphetamine the animals were immediately transferred into automated locomotor activity chambers that detect horizontal and vertical movements for 1 hour (Roberts et al., 2004). In addition, an observer blinded to genotype and treatment visually assessed several behaviours for 10 seconds per mouse at 10 minute intervals throughout the 1 hour session. The recorded behaviours were: no movement/still, grooming, locomotion, rearing, head-up sniffing, head-down sniffing, mouth movements, taffy pulling, and circling. Taffy pulling involves movements of both front paws to the mouth and then away, repeated over and over again. Except for ‘no movement’ and locomotion, these behaviours are indicators of stereotypy (repetitive activities). All experimental procedures were in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Burnham Institute for Medical Research and The Scripps Research Institute.

2.2 Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied for statistical analysis of differences between the two genotypes within each given dose level. ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc test, which corrects for multiple comparisons, was used to analyze statistical differences between Saline and the various concentrations of Methamphetamine for both genotypes (StatView®, version 5.0.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). In our exploratory investigation we considered the nine non-automated measures to represent one grouping at each dose level and the two automated measures to constitute a distinct grouping for that same dose level. An overall alpha level of 0.05 was used for statistical significance. We adopted a conservative approach using a Bonferroni correction which requires a p = 0.05 / 9 = 0.0056 for the nine non-automated measures and a p = 0.05 / 2 = 0.025 for the two automated measures to reach significance in a Student’s t-test. In the alternative, second exploratory approach, we investigated the effect of Methamphetamine versus Saline using ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc test. With the correction for multiple comparisons a p = 0.05 / 36 = 0.0014 for each of the 36 comparisons for the non-automated measures (nine measures × 4 dose level comparisons with control) indicated significance. Accordingly, for the two automated measures p = 0.05 / 8 = 0.00625 indicated significance (two measures × 4 dose level comparisons with control).

We decided to report adjusted p-values, i.e., the actual (nominal) p-values multiplied by the corresponding correction factor, to allow the comparison with alpha = 0.05 for indication of statistical significance. Thus for the nine non-automated measures, for example, an actual (nominal) p-value of 0.0008 for a t-test is reported via its adjusted value of p = 0.0008 × 9 = 0.0072 for a direct comparison with alpha = 0.05.

3. Results

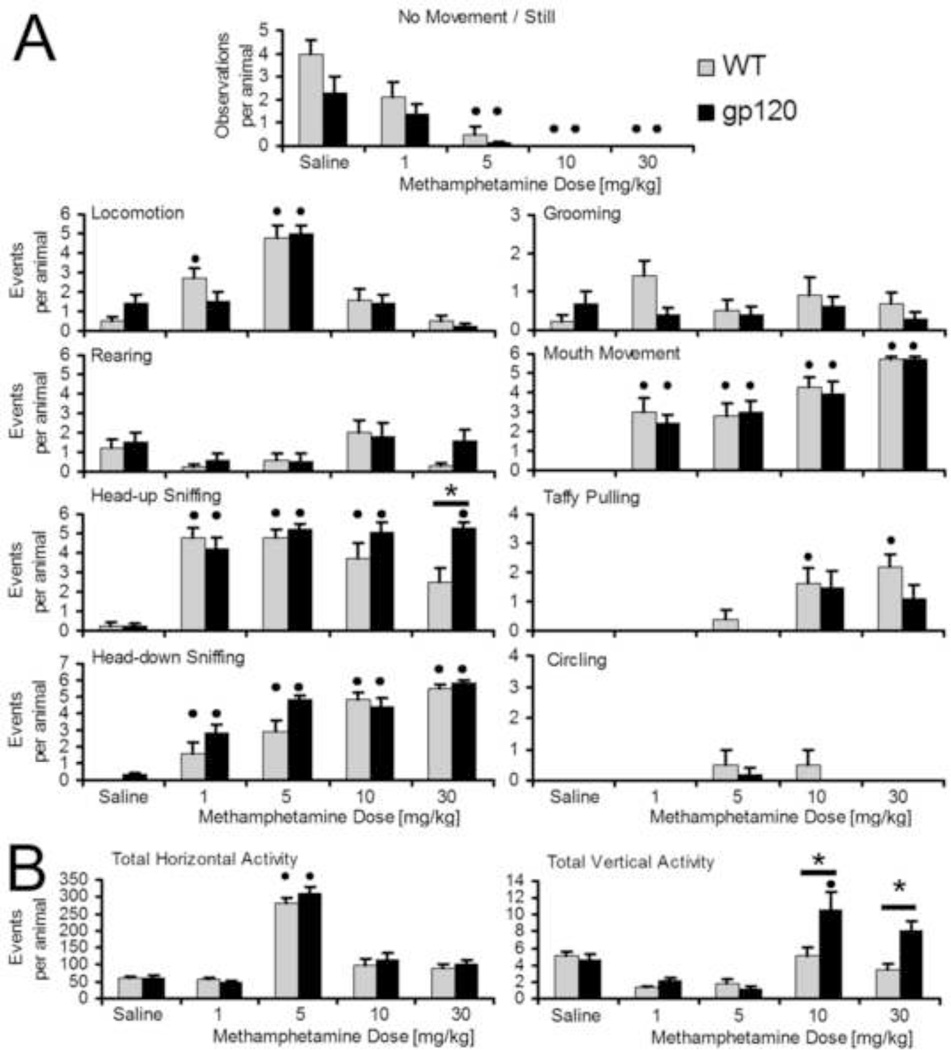

Methamphetamine exposure revealed a highly significant difference between gp120tg and WT mice in head-up sniffing at 30 mg/kg Methamphetamine (adjusted p = 0.0072, Student’s t-test with Bonferroni correction, n = 10 per genotype), Figure 1A, and automatically recorded total vertical activity at 10 and 30 mg/kg Methamphetamine (adjusted p = 0.015 and 0.0006, respectively, Student’s t-test with Bonferroni correction), Figure 1B, with gp120tg mice showing increased activity compared to WT control littermates. Application of Methamphetamine caused significant sniffing and mouth movement at all concentrations in both genotypes (adjusted p = 0.0036, ANOVA and Bonferroni/Dunn) except for both head-up sniffing at 30 mg/kg and head-down sniffing at 1 mg/kg in WT mice, Figure 1A. Locomotion was significantly increased by Methamphetamine at 1 and 5 mg/kg in WT but only at 5 mg/kg in gp120tg mice (adjusted p = 0.022 by ANOVA and Bonferroni/Dunn). Accordingly, observations of no movement were significantly diminished by 5 mg/kg in WT and gp120-transgenic mice (adjusted p = 0.0072 by ANOVA and Bonferroni/Dunn). No movement observations were absent at 10 and 30 mg/kg in both genotypes. Methamphetamine-treated WT animals, but not HIV/gp120tg mice, showed dose-dependent differences for taffy pulling at 10 and 30 mg/kg (adjusted p = 0.032, ANOVA and Bonferroni/Dunn). Although Methamphetamine induced significant mouth movements at all tested concentrations (adjusted p = 0.01, ANOVA and Bonferroni/Dunn), no significant differences between the two genotypes were observed. Furthermore, HIV/gp120tg and WT mice groomed and reared without showing any significant differences between genotypes or Saline and the various Methamphetamine concentrations. Also, no significant circling occurred at any Methamphetamine dosage.

Figure 1.

Activity and stereotyped behaviour of HIV/gp120 transgenic and non-transgenic littermate control mice after i.p. injection of different doses of Methamphetamine or Saline vehicle. Age-matched 9 to 13 month-old HIV/gp120tg mice (5 females, 5 males) and non-transgenic littermate control animals (7 females, 3 males) were injected i.p. with Saline (vehicle control) or Methamphetamine at the indicated concentration. Subsequently locomotion and stereotyped behaviour was assessed by visual observation (A) and automated recording (B) as described in the text. * adjusted p < 0.05 for differences between genotypes, • adjusted p < 0.05 for differences between Saline and Methamphetamine treatments.

Averaged automatically recorded total horizontal activity over a 1 hour test indicated a significant increase in mice of both genotypes after injection of 5 mg/kg Methamphetamine (adjusted p = 0.0008 for 5 mg/kg, ANOVA and Bonferroni/Dunn), Figure 1B. Automated recording of total vertical activity over the same time period indicated significant differences between the genotypes at 10 and 30 mg/kg Methamphetamine as mentioned above. Moreover, Methamphetamine at 10 mg/kg caused a significant increase in vertical activity compared to Saline in HIV/gp120tg mice (adjusted p = 0.0008, ANOVA and Bonferroni/Dunn) but not WT littermate controls.

The behaviour of mice following Saline injections at different times was indistinguishable and therefore test values for all Saline treatments were averaged for each animal. Interestingly however, observations of no movement showed a trend to differ between HIV/gp120tg and non-transgenic littermate control mice throughout Saline applications, with gp120tg animals showing less time without movement (adjusted p = 0.13 by ANOVA with Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc test), Figure 1A.

4. Discussion

Our study compared locomotion and stereotyped behaviour in HIV/gp120tg mice and non-transgenic wild type littermate controls upon exposure to four different doses of Methamphetamine or Saline as control. The behavioural assessments used both visual observations and automated counting and revealed significant differences between the two genotypes in Methamphetamine effects for the following five parameters: head-up and head-down sniffing, taffy pulling, locomotion and total vertical activity counts. In contrast, the two genotypes, when given Methamphetamine, did not significantly differ from each other in the five parameters of rearing, grooming, mouth movement, circling and total horizontal activity. Visual observations of rearing and automated counting of vertical activity would be expected to show similar trends, although the mice need to rear to a certain height and interrupt a light beam to trigger an automated count. In fact both measures support a greater rearing in HIV/gp120 mice following the highest Methamphetamine dosage, while the continuous, automated recording detected a significant increase in vertical activity already at the second highest Methamphetamine dosage. Except for visual observation of locomotion at 1 mg/kg Methamphetamine, neither this measure nor its related automated counting of horizontal activity revealed any other genotypic differences following Methamphetamine. Therefore, HIV/gp120 mice appear to be more sensitive than WT mice to stereotypic effects of Methamphetamine, while being less differentially sensitive to the locomotor stimulant effects of this drug. The nigro-striatal dopamine pathway and the mesolimbic dopaminergic system have been implicated in stereotypic behaviour and control of locomotor stimulation, respectively (Randrup et al., 1988; Phillips and Shen, 1996). The significant differences between HIV/gp120tg and non-transgenic control animals in certain Methamphetamine-induced stereotyped behaviours strongly suggest that the viral envelope protein affects the nigro-striatal dopaminergic pathway and influences the reaction of the brain to Methamphetamine exposure.

Interestingly, visual observations indicated a previously unrecognized trend towards a difference between HIV/gp120tg and control animals under the control condition of Saline injection for no movement and a significant difference at 1 mg/kg Methamphetamine for locomotion, which the automated counting of total horizontal activity surprisingly did not pick up. The observations of locomotion were made at 6 intervals across the 1 hour test period; whereas the automated activity counts were made continuously throughout the test period. In addition, observations of locomotion were made when mice were clearly taking enough consecutive steps in a single direction so as to cover a distance of at least 3 body lengths. Horizontal activity counts were recorded when consecutive photobeams (spaced 10 cm apart, thus less than three body lengths) were disrupted. However, in terms of picking up sensitivity to Methamphetamine effects, both visual observation of locomotion and automated assessment of horizontal activity detected the most pronounced increase in activity after the application of 5 mg/kg Methamphetamine. Therefore, at this time the assessments of locomotion and horizontal activity remain to be further developed in order to clarify whether HIV/gp120 mice show increased activity levels under baseline conditions; however the visual observations support further investigation into a potential alteration of mesolimbic dopaminergic activity due to the expression of HIV/gp120 independently of Methamphetamine. While our findings for locomotion and stereotyped behaviour do not explain why the combination of Methamphetamine and HIV-1 apparently causes more neurocognitive deficits than each agent alone (Rippeth et al., 2004; Cadet and Krasnova, 2007), our experimental model system may be useful to further study the mechanistic interaction of both the viral envelope protein and the drug in behavioural alterations and neurodegenerative disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by NIH grants R01 NS050621 (to M.K.) and P30 NS057096 (NIH Blueprint Grant for La Jolla Interdisciplinary Neuroscience Center Cores, Mouse Behavioural Assessment Core, to A.J.R.). The authors thank Dr. Florin Vaida and Kathryn E. Medders for critically reading the manuscript and declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HAND

HIV-associated neurological disorders

- HAD

HIV-associated dementia

- tg

transgenic

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficiency

- AIDS

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet JL, Krasnova IN. Interactions of HIV and methamphetamine: cellular and molecular mechanisms of toxicity potentiation. Neurotox. Res. 2007;12:181–204. doi: 10.1007/BF03033915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'hooge R, Franck F, Mucke L, De Deyn PP. Age-related behavioural deficits in transgenic mice expressing the HIV-1 coat protein gp120. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4398–4402. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul M, Garden GA, Lipton SA. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nature. 2001;410:988–994. doi: 10.1038/35073667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krucker T, Toggas SM, Mucke L, Siggins GR. Transgenic mice with cerebral expression of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 coat protein gp120 show divergent changes in short- and long-term potentiation in CA1 hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1998;83:691–700. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00413-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto S, Kang Y, Brechtel C, Siviglia E, Russo R, Clemente A, Harrop A, McKercher S, Kaul M, Lipton SA. HIV/gp120 decreases adult neural progenitor cell proliferation via checkpoint kinase-mediated cell cycle withdrawal and G1 arrest. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Limoges J, McComb R, Bock P, Baldwin T, Tyor W, Patil A, Nottet HS, Epstein L, Gelbard H, Flanagan E, Reinhard J, Pirruccello SJ, Gendelman HE. Human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis in SCID mice. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:1027–1053. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TJ, Shen EH. Neurochemical bases of locomotion and ethanol stimulant effects. Int. Rev Neurobiol. 1996;39:243–282. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60669-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randrup A, Sorensen G, Kobayashi M. Stereotyped behaviour in animals induced by stimulant drugs or by a restricted cage environment: relation to disintegrated behaviour, brain dopamine and psychiatric disease. Yakubutsu Seishin Kodo. 1988;8:313–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippeth JD, Heaton RK, Carey CL, Marcotte TD, Moore DJ, Gonzalez R, Wolfson T, Grant I. Methamphetamine dependence increases risk of neuropsychological impairment in HIV infected persons. J Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2004;10:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704101021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, Krucker T, Levy CL, Slanina KA, Sutcliffe JG, Hedlund PB. Mice lacking 5-HT receptors show specific impairments in contextual learning. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1913–1922. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JC, Woods SP, Matt GE, Meyer RA, Heaton RK, Atkinson JH, Grant I. Neurocognitive effects of methamphetamine: a critical review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2007;17:275–297. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talloczy Z, Martinez J, Joset D, Ray Y, Gacser A, Toussi S, Mizushima N, Nosanchuk J, Goldstein H, Loike J, Sulzer D, Santambrogio L. Methamphetamine Inhibits Antigen Processing, Presentation, and Phagocytosis. PLoS. Pathog. 2008;4:e28. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toggas SM, Masliah E, Rockenstein EM, Rall GF, Abraham CR, Mucke L. Central nervous system damage produced by expression of the HIV-1 coat protein gp120 in transgenic mice. Nature. 1994;367:188–193. doi: 10.1038/367188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina A, Jones K. Crystal methamphetamine, its analogues, and HIV infection: medical and psychiatric aspects of a new epidemic. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38:890–894. doi: 10.1086/381975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]