Abstract

Perceived support has been related to lower cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. However, little is known about the specific functional components of support responsible for such links. We tested if emotional, informational, tangible, and belonging support predicted ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) and interpersonal interactions (e.g., responsiveness), and if such links were moderated by gender. In this study, 94 married couples underwent 12 hours of ABP monitoring during daily life which included a night at home with their spouse. They completed a short-form of the interpersonal support evaluation list that provides information on total (global) support, as well as specific dimensions of support. Results revealed that global support scores did not predict ABP during daily life. However, separating out distinct support components revealed that emotional support was a significant predictor of lower ambulatory systolic and diastolic blood pressure, primarily for women. Finally, emotional support predicted greater partner responsiveness and self-disclosure, along with less perceived partner negativity although these results were not moderated by gender. These data are discussed in terms of the importance of considering specific support components and the contextual processes that might influence such links.

Keywords: perceived social support, emotional support, gender, ambulatory blood pressure, partner responsiveness, self-disclosure, health

1. Introduction

Social support is associated with beneficial health outcomes, including reduced rates of mortality and morbidity (Cassel, 1976; Cobb, 1976; Cohen, 1988; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010; House et al., 1988; Seeman; 1996; Uchino, 2004). In the most compelling evidence to date, a meta-analysis of 148 studies and over 300,000 participants found that aspects of social support predicted survival with an effect size comparable to or larger than traditional medical predictors, such as smoking and exercise (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). These effects were not moderated by initial health status, age, or cause of death. Social support is also specifically linked to lower mortality risk due to cardiovascular disease (Barth et al., 2010; Berkman et al., 1992; Orth-Gomer et al., 1993; Kawachi et al., 1996) which is important because cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in most industrialized countries (Xu et al., 2010).

Despite these epidemiological links, relatively less is known about the mechanisms that might be responsible for such links. Ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) is one promising biological mechanism that may explain links between social support and cardiovascular disease. ABP protocols typically examine cardiovascular functioning in the "real world" and hence have relatively high ecological validity. Importantly, ABP is a robust predictor of cardiovascular disease risk even after considering clinic resting blood pressure levels (Bjorklund et al., 2004; Perloff et al., 1983; Pickering et al., 1985).

However, few studies have examined if social support predicts ABP and these studies are heterogeneous in terms of findings. In one study, Linden and colleagues (1993) found perceived social support to predict lower ABP for women but not for men, whereas Brownley and colleagues (1996) found that perceived support predicted lower ABP primarily in high hostile individuals (Brownley et al., 1996). Another study found social support was related to lower ABP only at night (Steptoe et al., 2000). Finally, several studies report no significant link between global social support and ABP (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2008; Steptoe, 2000; Vella et al., 2008).

Several important conceptual issues arise when considering the links between social support and ABP that may help explain these diverse findings. First, social support can be differentiated into distinct functional components (Barrera, 2000; Cohen et al., 1985). These functional components consist of emotional (self-esteem), informational (appraisal), tangible (or instrumental), and belonging support (Cohen et al., 1985; Wills & Shinar, 2000). Emotional support entails empathy and positive feedback regarding self-worth. Informational support involves provision of information or advice, which may also be referred to as appraisal support, because the support might involve provision of information that contributes to re-appraisals of a situation as less stressful or threatening (Cohen et al., 1985). Tangible support comes in the form of material aid, whereas belonging support includes opportunities for social inclusion and recreation.

Importantly, most prior studies in this area have examined global support. This is a significant issue because it has been argued that some components of support are beneficial across situations and hence may be more closely linked to ABP (Cohen & McKay, 1984; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Cutrona & Russell, 1990; Wills, 1991). In particular, emotional and informational support are hypothesized to be more likely to have positive influences on health outcomes because people can always benefit from reassurances of their self-worth or useful information (Cohen & Wills; Cohen, 1988). However, only one previous study of which we are aware compared specific functional components of support and its links to ABP (Brownley et al., 1996). In this particular study, emotional support was not included in the measurement of functional components, yet we know that – of the functional components – emotional support is most often predictive of positive health-related outcomes (Heller et al., 1986; Wills, 1991). For example, King and colleagues (1993) examined the effects of perceived emotional, informational, and tangible support on recovery from coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Their data indicated that emotional support was the only form of social support that proved to be consistently predictive of recovery from CABG over the one year study. In another study, high levels of emotional support predicted lower mortality in older adults whereas tangible support actually predicted greater mortality (Penninx et al., 1997; also see Berkman et al., 1992). Thus, one aim of this study was to examine if different functional components of support would provide a more sensitive test of links to ABP during daily life.

A second aim of this study was to examine potential gender differences in links between functional support components and ABP. Social support processes and outcomes may differ in men and women (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001; Shumaker & Hill, 1991; Flaherty & Richman, 1989). More specifically, a broader literature suggests that emotional support is a particularly important functional component of social support for women (Burleson, 2003). Females receiving high levels of emotional support from family and peers exhibit lower blood pressure reactivity during stress and increases in psychological well-being (Slavin & Rainer, 1990; Wilson & Ampey-Thornhill, 2001; Wilson et al, 1999). Whether due to socialization, social roles, or biological differences, women tend to prefer, seek out, and respond more positively to emotional support (Burleson; Flaherty & Richman; Gilligan, 1982; Shumaker & Hill; Wills, 1985).

Although not a primary aim due to our emphasis on health-relevant biological pathways, we also examined if functional components of support predicted interpersonal processes when couples were at home together. Such data may provide a "snapshot" into the lives of individuals relatively high versus low on social support. Perceived support has been related to positive interpersonal processes such as greater intimacy through self-disclosure, partner responsiveness, and the interpretation of social interactions (Laurenceau, Barrett, & Pietromonaco, 1998; Lakey & Cassady, 1990; Reis, 2007). However, most of this work has not focused on distinct support components or utilized diary experience sampling. Importantly, examining these processes in the context of functional support components furthers our understanding of how perceived social support relates to the interpretation of daily interpersonal interactions. For example, emotional support may be a particularly relevant component as it is characterized by validation, positivity, and responsiveness.

The current study thus expands our understanding of social support processes in a naturalistic setting, with measures of ABP, functional components of support, gender, and interpersonal processes. Participants in our study completed a one day ABP assessment in which a blood pressure reading was randomly taken once during every 30 minute period. Based on the aims of the study, we expected that individuals with greater informational and emotional support would exhibit lower ABP during daily life and more positive interpersonal exchanges. We further expected that emotional support would be associated with lower ABP in women compared to men. We also expected that women higher in emotional support would evidence more positive interpersonal processes.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

As part of a larger program project, 97 healthy heterosexual couples were recruited through advertisements placed in local newspapers, workplace newsletters, and flyers distributed around the community. We used the following criteria to select healthy participants based on our prior work (Cacioppo et al., 1995): no existing hypertension, no cardiovascular prescription medication use, no history of chronic disease with a cardiovascular component (e.g., diabetes), and no recent history of psychological disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder). Participants were all legally married and living together with a mean age of 29.6 (see Table 1). Most were White (83%), college educated (62.4%), and had an income over $40,000 per year (66%). Three couples who did not follow the study protocol were eliminated from the study, resulting in a total of 94 couples. Participants were compensated $75 (or extra course credit) for their time.

Table 1.

Upper Triangle of Correlation Matrix for ISEL Subscales for Men and Women.*

| Variable | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|

Informational |

1.0 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 1.0 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.22 |

|

Belonging |

1.0 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 1.0 | 0.65 | 0.35 | ||

|

Tangible |

1.0 | 0.45 | 1.0 | 0.34 | ||||

| Emotional | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

All correlations were significant at p = .0001

2.2. Study protocol

Eligible participants arrived at the laboratory on the morning of a typical work day. Height and weight were assessed using a Health-o-Meter scale in order to calculate body mass index to be used as a covariate. Demographic information was collected including age, income, and education and participants completed the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (Cohen et al., 1985).

As part of the larger study protocol, participants completed a one day ABP assessment, typically from 8 am to 10 pm (M= 14.01 hours, SD= 0.97) which included working hours and an evening at home with the spouse on the same day.1 The ABP monitor was set to take a random reading once within every 30 minute window. This random interval-contingent monitoring procedure minimizes participants’ anticipation of a blood pressure assessment that might lead them to alter their activities. Following each ABP assessment, individuals were instructed to complete questions (ADR, see below) programmed into a palm pilot device using the Purdue Momentary Assessment Tool (Weiss et al., 2004). Participants were instructed to complete the ADR within 5 minutes of each cuff inflation.

Participants were fitted with the ABP monitor by a trained research assistant and given detailed instructions on how to use it, including how to remove it at the end of the day. They were also given a palm pilot to record diary entries following each blood pressure reading and detailed instructions on how to use it. One reading was obtained before the participants left the lab to insure that the monitors were working properly and that participants understood how to use the palm pilots and how to correctly complete the ADR. An appointment to return the equipment and to receive compensation on the following day was set and participants were debriefed at the return appointment and all questionnaires and equipment were returned.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL)

We used a short-form of the ISEL that contained 15 questions (Cohen et al., 1985). It assessed the perceived availability of support, as well as the specific dimensions of informational (appraisal, 4 items), emotional (self-esteem, 3 items), belonging (4 items), and tangible (4 items) support. In the present study, the internal consistency of the scale was adequate: .81 for the total scale, .60 for tangible support, .69 for informational support, .57 for emotional support, and .66 for belonging support.2 For correlations among ISEL subscales for males and females, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants.

| Variable | Mean±SD |

|---|---|

| Age | 29.56±8.56* |

| BMI | 25.61±5.13** |

| Ethnicity | 83.07% Caucasian |

| 8.99% Latino/Hispanic | |

| 6.35% Asian-American | |

| 1.59% Other | |

| Income | 66.40% $40,000+ |

| 11.11% $30,000–39,999 | |

| 13.76% $20,000–29,999 | |

| 8.73% $19,999 or less | |

| Education | 62.4% College Degree |

In years

Body Mass Index = weight (kg)/height (m2)

2.3.2. Ambulatory blood pressure

The Oscar 2 (Suntech Medical Instruments, Raleigh, NC) was used to estimate ambulatory systolic blood pressure (SBP) and ambulatory diastolic blood pressure (DBP). The Oscar was developed to meet the reliability and validity standards of the British Hypertension Society Protocol (Goodwin et al., 2007). The cuff was worn under the participants’ clothing, and only a small control box (approximately 5.0 × 3.5 × 1.5 inches) attached to the participant’s belt was partially exposed. Outliers associated with artifactual readings were identified using the criteria by Marler, Jacobs, Lehoczky, and Shapiro (1988). These included: (a) SBP < 70 mmHg or > 250 mmHg, (b) DBP < 45 mmHg or > 150 mmHg, and (c) SBP / DBP < [1.065 + (.00125 X DBP)] or > 3.0. Readings were taken once randomly during each 30 minute window. Due to the deletion of artifactual readings (e.g., cuff inflation problems), the mean is slightly longer then the targeted 30 minutes window (M= 31.15, SD= 7.64).

2.3.3. Ambulatory Diary Record (ADR)

Participants were instructed to complete a series of programmed questions following each ambulatory cardiovascular assessment. The ADR was designed to be easy to complete (about 2–3 minutes) in order to maximize cooperation. It contained information on basic variables that might influence ABP (Kamarck et al., 1998). These included posture (lying down, sitting, standing), activity level (1= no activity, 4= strenuous activity), location (work, home, other), talking (no, yes), temperature (too cold, comfortable, too hot), prior exercise (no, yes), and prior consumption of nicotine, caffeine, alcohol or a meal (no, yes). Measures of interpersonal processes were adapted from prior work and included 4 items for perceived partner responsiveness, 2 items for perceived interaction positivity and negativity with the spouse, and 1 item for self-disclosure (Laurenceau, Feldman-Barrett, & Rovine, 2005; Reis & Wheeler, 1991). Readings were examined to ensure compliance and were discarded if not instigated within 5 minutes of a blood pressure reading.

2.4. Statistical analyses

We utilized PROC MIXED (SAS institute, Littell et al., 1996) in order to examine ABP and diary ratings of interpersonal processes (see Schwartz & Stone, 1998). PROC MIXED uses a random regression model to derive parameter estimates both within and across individuals (Singer, 1998). All factors were treated as fixed (Nezlek, 2008) and PROC MIXED treats the unexplained variation within individuals as a random factor.

One advantage of PROC MIXED is the ability to model more accurate covariance structures for the repeated measure assessments. In the present study, we modeled the covariance structure for the two repeated measures factors of dyad (i.e., husband, wife) and measurement occasion (i.e., reading number). Such nested repeated measures designs can be handled in PROC MIXED by specifying separate covariance structures for each of the factors (Park & Lee, 2002). More specifically, we modeled the covariance structure between individuals of a dyad within each measurement occasion, as well as the covariance structure across measurement occasions using the direct (Kronecker) product (Galecki, 1994; Park & Lee, 2002). This direct product is a within-subjects covariance profile containing the product of the two separate covariance matrices (Galecki, 1994). PROC MIXED currently allows only a few possible combinations for calculating the Kronecker product. Based on the recommendations of Park and Lee (2002), we modeled the covariance matrices for dyad and measurement occasion using the “type=un@ar(1)” option. Importantly, this model allowed us to examine predictors of ABP while controlling for the dependency within dyads and measurement occasions. The output of these random regression models were parameter estimates (b) with the appropriate within-subjects covariance structures considered. As recommended by Campbell and Kashy (2002), we used the Satterthwaite approximation to determine the appropriate degrees of freedom.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

We first examined potential covariates such as posture or activity level that might need to be statistically controlled in the analysis of ABP (Kamarck et al., 1998; Marler et al., 1988). Consistent with prior research, results of this initial model revealed that age, gender, household income, body mass, posture, temperature, activity level, prior alcohol, and prior exercise were independent predictors of higher ambulatory SBP (p's < .05). In addition, age, gender, household income, body mass, posture, activity level, and a prior meal independently predicted ambulatory DBP (p's < .05). Consistent with prior work, these factors along with time (i.e., first reading, second reading) were thus statistically controlled in all analyses involving ABP (Kamarck et al., 1998).

3.2. Do Functional Components of Social Support Predict ABP?

A primary aim of this study was to test for differences in ABP as predicted by functional components of social support. However, we first examined whether global perceived support predicted ABP levels. Consistent with the importance of examining specific support components, global social support did not significantly predict either ambulatory SBP (b= −1.98, SE= 1.30, p=.13) or DBP (b= −0.69, SE= 0.82, p=.40). We next examined ABP in analyses where functional components of social support (as assessed by the ISEL subscales of informational, belonging, emotional, and tangible support) were included as separate predictor variables. As shown in Table 3, higher emotional support significantly predicted lower ambulatory SBP (b= −2.82, SE= 1.06 p=.008) and DBP (b= −1.52, SE= 0.67, p=.025). Higher informational support also predicted lower ambulatory SBP (b= −1.8, SE= 0.96, p=.05), although it did not significantly predict DBP (b= −.85, SE= 0.61, p=.16). Other functional components of social support (belonging, tangible) were not separate predictors of either ambulatory SBP or DBP.

Table 3.

Main effects of functional social support on ABP.

| Variable | SBP | DBP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | S.E. | t | df | p | b | S.E. | t | df | p | |

| Informational | −1.84 | 0.96 | −1.93 | 613 | .05** | −0.85 | 0.61 | −1.40 | 769 | .16 |

| Belonging | 0.58 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 610 | .50 | 0.39 | 0.54 | 0.72 | 766 | .47 |

| Tangible | −1.00 | 0.92 | −1.09 | 619 | .28 | −0.13 | 0.58 | −0.23 | 768 | .82 |

| Emotional | −2.82 | 1.06 | −2.67 | 615 | .01** | −1.52 | 0.67 | −2.25 | 767 | .02* |

p<.05,

p<.01

p<.001

Emotional and informational support were both predictors of ambulatory SBP. As a result we also examined their independent links to ABP. Entering both of these support components into the model at the same time revealed that emotional support (b= −2.63, SE= 1.06, p=.01) but not informational support (b= −1.58, SE= 0.96, p=.10) predicted lower ambulatory SBP. These data suggest that emotional support was a stronger predictor of ABP during daily life.

3.3 Does Gender Moderate the Links Between Functional Components of Social Support and ABP?

A second aim of this study was to test for gender-related differences in ABP as predicted by functional components of social support. We thus examined ABP in analyses where functional components of social support (informational, belonging, emotional, and tangible support), gender, and the cross-product term (based on the centered main effects of functional support and gender) were predictor variables. Again, we first examined if global social support interacted with gender in predicting ABP. The interaction between global social support and gender did not significantly predict ambulatory SBP (b= −3.15, SE= 2.51, p=.21) or DBP (b= −1.40, SE= 1.58, p=.38).

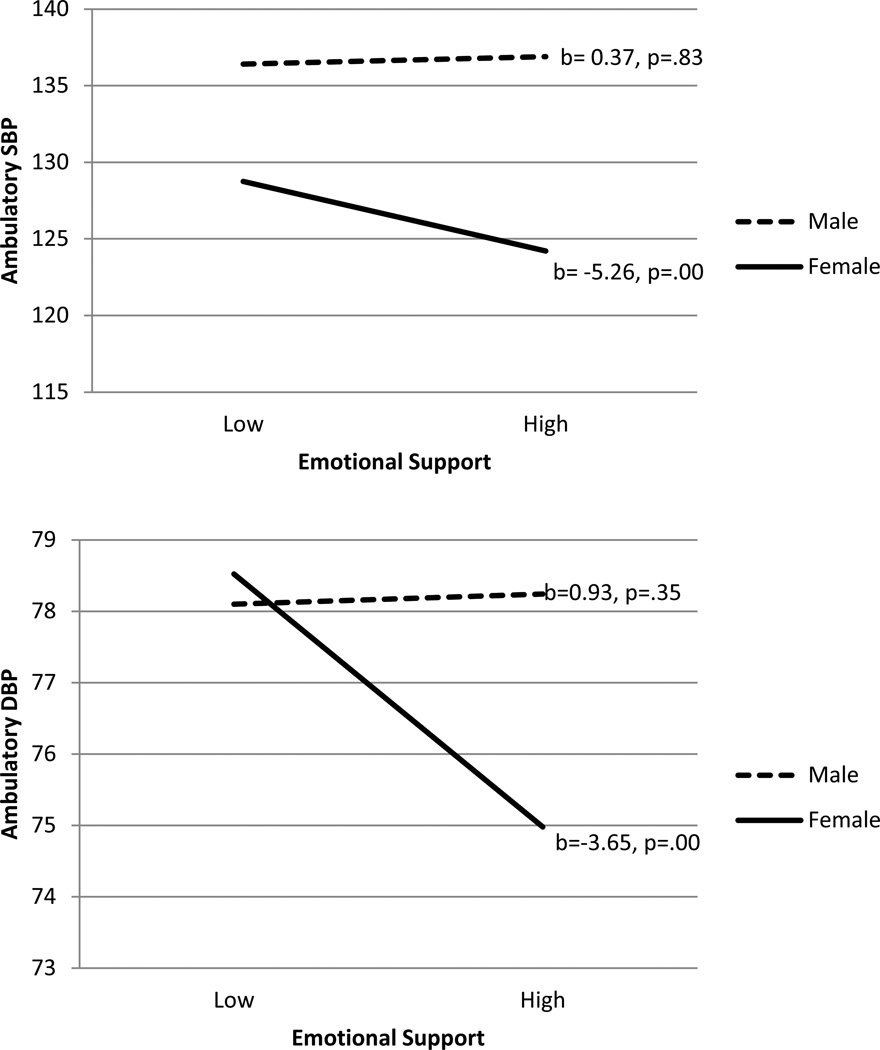

As shown in Table 5, consistent with our predictions, the interaction of emotional support and gender predicted ambulatory SBP (b= −5.90, SE= 2.07, p=.005) and DBP (b= −4.28, SE= 1.30, p=.001). There were no significant interactions between gender and informational, belonging, or tangible support. As depicted in Figure 1, we graphed the form of the significant interaction by plotting predicted ambulatory SBP (top panel) and DBP (bottom panel) values for women and men one standard deviation above and below the mean for emotional support. Follow-up analyses blocking on gender revealed that high levels of emotional support predicted lower ABP for women (p's < .001), but not for men (p's > .35).

Table 5.

Interaction effects of gender and functional social support on ABP.

| Variable | SBP | DBP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | S.E. | t | df | p | b | S.E. | t | df | p | |

| Informational | −3.02 | 1.89 | −1.60 | 615 | .11 | −0.86 | 1.19 | −0.72 | 748 | .47 |

| Belonging | 1.56 | 1.68 | 0.93 | 612 | .36 | 1.45 | 1.79 | 1.37 | 749 | .17 |

| Tangible | −1.71 | 1.79 | −0.95 | 623 | .34 | −0.96 | 1.13 | −0.85 | 764 | .40 |

| Emotional | −5.90 | 2.07 | −2.85 | 628 | .005** | −4.28 | 1.30 | −3.30 | 775 | .001*** |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Figure 1.

Predicted ambulatory SBP (top panel) and DBP (bottom panel) scores for men and women one SD above and below the mean for emotional support.

3. 4. Do Functional Components of Social Support and Gender Predict Daily Interpersonal Processes?

We also tested for differences in interpersonal transactions that occur as a function of support components. As part of this study, couples spent an evening at home with each other while measures of partner responsiveness, perceived positivity of interactions, perceived negativity of interactions, and self-disclosure were taken. Controlling for time, age, and gender, individuals high in global support reported lower perceived negative interactions (b= −0.21, SE= 0.10, p=.04) and greater self-disclosure (b= 0.42, SE= 0.14, p=.004). Consistent with our predictions, analyses of specific support components revealed that emotional support most consistently predicted daily life interpersonal processes in couples. Higher emotional support was related to greater perceived partner responsiveness (b= 0.28, SE= 0.10, p=.006) and self-disclosure (b= 0.37, SE= 0.12, p=.002), and lower perceived home negativity (b= −0.18, SE= 0.08, p=.04). The only other components of support to predict these daily life processes were belonging support and tangible support. Belonging support predicted greater home positivity (b= 0.17, SE= 0.08, p=.03) and self-disclosure (b= 0.27, SE= 0.09, p=.003), whereas tangible support also predicted greater self-disclosure (b= 0.21, SE= 0.10, p=.04). Given that emotional support, tangible support, and belonging support were all predictors of self-disclosure, follow-up analyses examined their independents links by entering all of these support components into the model. Results showed that only emotional support remained a significant predictor of greater self-disclosure (b= 0.28, SE= 0.13, p=.04).

We next examined whether gender moderated the links between support components and these daily life processes in couples. Contrary to our predictions, no gender X emotional support interactions were significant in the prediction of daily interpersonal processes. However, gender did moderate the link between global support and partner responsiveness (b= −0.48, SE= 0.23, p=.04) and perceived interaction positivity (b= −0.54, SE= 0.23, p=02). These statistical interactions with global support primarily reflected the influence of belonging support on responsiveness (b= −0.31, SE= 0.15, p=.04) and the influence of tangible support on home positivity (b= −0.36, SE= 0.16, p=.03). Follow-up analyses revealed that these statistical interactions reflected stronger links between social support and greater partner responsiveness / interaction positivity in husbands (p's < .05) and not wives (p's > .28).

4. Discussion

The primary aims of this study were to (a) examine the links between distinct functional components of social support and ABP, (b) explore gender differences in these associations. An ancillary aim was to also examine these questions using measures of daily interpersonal processes. Most of our major predictions were supported. The results indicate that higher emotional and informational support predicted lower ABP. Emotional support, in particular, predicted lower ABP for women, but not for men. High emotional support also predicted greater perceived partner responsiveness, self-disclosure, and lower perceived interaction negativity when spending an evening at home with a spouse. Inconsistent with our hypotheses, the links between emotional support and interpersonal processes were not moderated by gender. We did find, however, that husbands high in belonging support were more likely to perceive greater partner responsiveness, whereas husbands high in tangible support were more likely to perceive greater interaction positivity.

In accordance with our first hypothesis, higher emotional and informational support predicted lower ABP. Overall global support and other functional components of social support (tangible, belonging) were not significantly associated with ABP. Moreover, the main effect of emotional support on ABP was primarily seen in women. These results are particularly important to consider given the variable findings in previous social support and ABP studies, most of which examined global perceptions of support or gender differences (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2008; Linden et al., 1993; Steptoe, 2000; Vella et al., 2008). In addition, studies that found a significant link between global perceptions of support and ABP tended to have a stronger emotional or informational support component in measurement (Brownley et al., 1996; Linden et al., 1993). Importantly, when both emotional support and informational support were examined as predictors at the same time, only emotional support was related to ABP. These data suggest that of these two support components, emotional support may be especially important to consider in future work.

Consistent with our predictions, women benefited most from emotional support. These findings are consistent with prior literature on the preference, utilization, and receipt of emotional support in women (Flaherty & Richman, 1989). Whether due to socialization, biological differences, or some other unknown factor, women tend to have a more interdependent view of the self and devote more psychological and social resources to establishing and maintaining social ties compared to men (Burleson, 2003; Cross & Madson, 1997). These data suggest that women are more sensitive to the "affective tone" of relationships. Although women may benefit from the positive (especially emotional) aspects, this also implies they are more adversely influenced by negativity in relationships, which is also consistent with the prior literature (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). However, emotional support is a more nurturing and less controlling form of social support, and thus may activate less of these negative aspects, while also promoting relational interdependence through empathy and affirmation (Trobst, 2000).

Ancillary analyses also showed that social support predicted interpersonal processes between husbands and wives during an evening at home. Emotional support was most predictive of these processes, with individuals high in emotional support reporting greater perceived partner responsiveness, self-disclosure and lower negativity. However, unlike results for ABP, gender did not moderate any of these associations. These results are consistent with the uncoupling that can occur between self-report and physiological processes (e.g., Uchino, Bowen, Carlisle, & Birmingham, in press) and highlights the importance of data from different levels of analysis (Cacioppo & Petty, 1986). Of course, we were primarily interested in more direct health-relevant pathways as indexed by ABP but future research might consider links between emotional support, gender, and more specific emotional processes (e.g., social emotions, Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004) which have been linked to both social situations and health-relevant biological processes.

We did find that gender moderated some of the associations between perceived social support and interpersonal processes. More specifically, husbands high in belonging support were more likely to perceive greater partner responsiveness, whereas husbands high in tangible support were more likely to perceive greater interaction positivity. Although one might expect these links to be stronger in women, Neff and Karney (2005) found that wives provided support in a more responsive manner compared to husbands. As a result, these interpersonal links may be stronger in men because they are picking-up (accurately) on the responsive or positive behaviors of their wives (Neff & Karney, 2005).

It is important to consider the conceptual delineation between perceived and received social support when interpreting these findings. The ISEL is a measure of perceived social support – or the internal perception of one’s available support to mobilize if needed within his or her network (Cohen et al., 1985). Importantly, perceived social support differs from received social support, which refers to actual supportive interpersonal transactions or exchanges (Sarason et al., 1990; Kaul & Lakey, 2003; Lakey & Lutz, 1996). These two conceptualizations are not highly correlated, which suggests they are separable constructs (Barrera, 2000; Uchino, 2009). This is important because perceived support has more consistent beneficial links to health as compared to received support (Uchino, 2009). This may be due to received support being perceived by the recipient as a threat to personal independence if unsolicited (Bolger and Amarel, 2007) or creating social inequity or relational debt (Shumaker & Brownell, 1984).

It is also important to note that perceived support was only measured at baseline and we did not have corresponding measures of received support during daily life. So what is captured by our perceived support measure that explains its links to ABP? Perceived social support is a fairly stable construct and hence might be expected to be stable during the course of our study (Lakey & Cassady, 1990; Uchino, 2009). As perceived social support is most consistently tied to positive health outcomes, it may be that perceiving social support as available, but not necessarily using it, leads to cognitive appraisals of greater resources (Wills & Shinar, 2000). Even if such resources are not utilized, knowing it is there gives the person a greater sense of control, independence, or self-efficacy, without the downsides of actually receiving support as mentioned above (Bolger & Amarel, 2007; Thoits, 2011). However, perceived and received support are correlated so it is possible that individuals during the study were receiving support. Future research is necessary to examine this possibility by using more specific assessments of daily support.

There are several limitations of the present study. Because studies collecting ABP in daily life capture data in the context of daily processes in participants’ natural environments, ABP protocols nicely bridge together epidemiology methods – which give data on real world outcomes – and laboratory studies – which allow for greater control and manipulation of contextual factors. However, while lending greater ecological validity to the study, ABP studies also sacrifice experimental control and the ability to detect cause-and-effect relationships. At most, we are able to examine patterns among support and cardiovascular function which could inform relevant experimental or intervention studies.

In spite of the aforementioned limitations of the current study, there are a number of strengths. First, dimensions of support were often better predictors of ABP compared to global support. This highlights the utility of specific functional support approaches in future work. Second, SBP has been identified as a strong linear predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD) for both men and women (Mason et al., 2004; Psaty et al., 2001). Similarly, a 2.5 mmHg difference in DBP translates to a 12% reduction in coronary heart disease risk, regardless of whether an individual is normo- or hypertensive (MacMahon et al., 1990). In the current study, there was a predicted difference of more than 3 mmHg between high and low emotional support for women for both ambulatory SBP and DBP. Thus, if a sustained increase in blood pressure increases risk of cardiovascular disease, then the current findings suggest clinically significant differences in ABP as a function of social support.

Third, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that ABP monitoring is more accurate and effective at diagnosing hypertension and determining the appropriate intervention than looking only at blood pressure in the clinic (Hodgkinson et al., 2011). As such, for the first time in several decades, the United Kingdom’s National Institute on Clinical Excellence revised its diagnosis standards (Mayor, 2011). Similarly, a recent computer modeling study suggests ABP monitoring may be more cost-effective at proper diagnosis of ABP in the long run as compared to traditional diagnosis based on blood pressure readings in the clinic (Lovibund et al., 2011). Thus, studies of social support consequences on ABP and the underlying pathways for this link have important health implications

Table 4.

Main effects of functional social support on ABP in the gender interaction model.

| Variable | SBP | DBP | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | S.E. | t | df | p | b | S.E. | t | df | p | |

| Informational | 2.80 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 594 | .36 | 0.42 | 0.61 | 0.23 | 615 | .82 |

| Belonging | −1.82 | 0.86 | −0.67 | 590 | .50 | −1.75 | 0.54 | −1.06 | 716 | .29 |

| Tangible | 1.61 | 0.92 | 0.56 | 594 | .58 | 1.27 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 720 | .47 |

| Emotional | 6.53 | 1.07 | 1.90 | 599 | .06 | 5.00 | 0.67 | 2.40 | 728 | .02* |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Table 6.

Main effects of functional social support on perceived partner responsiveness and self-disclosure in couple interactions at home.

| Variable | Perceived Partner Responsiveness |

Self-Disclosure | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | S.E | t | df | p | b | S.E | t | df | p | |

| Informational | −0.07 | 0.10 | −0.71 | 293 | .48 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.68 | 307 | .50 |

| Belonging | 0.12 | 0.08 | 1.56 | 290 | .12 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 2.95 | 303 | .003** |

| Tangible | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 275 | .93 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 2.09 | 289 | .04* |

| Emotional | 0.28 | 0.10 | 2.76 | 283 | .01** | 0.37 | 0.12 | 3.09 | 297 | .002** |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Table 7.

Main effects of functional social support on perceived positivity and negativity of couple interactions at home.

| Variable | Positivity | Negativity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | S.E. | t | df | p | b | S.E. | t | df | p | |

| Informational | −0.17 | 0.10 | −1.75 | 292 | .08 | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.88 | 339 | .38 |

| Belonging | 0.17 | 0.08 | 2.20 | 288 | .03* | −0.10 | 0.07 | −1.53 | 338 | .13 |

| Tangible | 0.11 | 0.09 | 1.28 | 272 | .20 | −0.12 | 0.07 | −1.68 | 319 | .09 |

| Emotional | 0.18 | 0.10 | 1.75 | 282 | .08 | −0.18 | 0.09 | −2.10 | 326 | .04* |

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001

Highlights.

Functions of social support predicted ABP, but global support did not.

Emotional support was the most consistently related to ABP.

Women appeared to benefit most from emotional support in terms of ABP.

Social support predicted perceptions of interpersonal processes among couples.

Acknowledgments

This research was generously supported by grants R01 HL68862 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Bert N. Uchino, PI).

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The current paper focuses on perceived functional support. A focus on the quality of the specific relationship between spouses and ABP is the subject of other papers (Sanbonmatsu, Uchino, & Birmingham, 2011; Birmingham et al., 2011).

The emotional support subscale had the least amount of items (3) which limited its internal consistency. We thus analyzed individual items for this subscale to ensure that the pattern was in the same direction for each individual item on ABP. Importantly, the same pattern of results reported below was evident on all items of the subscale.

Contributor Information

Kimberly S. Bowen, Department of Psychology and Health Psychology Program, University of Utah, Telephone: + 1 (801) 581.3176, Fax: + 1 (801) 581.5841, Kimberly.bowen@psych.utah.edu

Wendy Birmingham, Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah.

Bert N. Uchino, Department of Psychology and Health Psychology Program, University of Utah

McKenzie Carlisle, Department of Psychology and Health Psychology Program, University of Utah.

Timothy W. Smith, Department of Psychology and Health Psychology Program, University of Utah

Kathleen C. Light, Department of Anesthesiology, University of Utah

References

- Barrera M. Social support research in community psychology. In: Rappaport J, Seidman E, editors. Handbook of community psychology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2000. pp. 215–245. [Google Scholar]

- Barth J, Schneider S, von Känel R. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:229–238. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Leo-Summers L, Horwitz RI. Emotional support and survival after myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(12):1003–1009. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham W, Uchino BN, Smith TW, Light KC, Carlisle M. Spousal ambivalence is linked to elevated ambulatory blood pressure during daily life. 2011. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund K, Lind L, Zethelius B, Berglund L, Lithell H. Prognostic significance of 24-h ambulatory blood pressure characteristics for cardiovascular morbidity in a population of elderly men. J Hypertens. 2004;22(9):1691–1697. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200409000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Amarel D. Effects of social support visibility on adjustment to stress: Experimental evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(3):458–475. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownley KA, Light KC, Anderson NB. Social support and hostility interact to influence clinic, work, and home blood pressure in black and white women and men. Psychophysiol. 1996;33:434–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1996.tb01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleson BR. The experience and effects of emotional support: What the study of cultural and gender differences can tell us about close relationships, emotion, and interpersonal communication. Pers Relatsh. 2003;10:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Malarkey WB, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Uchino BN, Sgoutas-Emch SA, Sheridan JF, Berntson GG, Glaser R. Heterogeneity in neuroendocrine and immune responses to brief psychological stressors as a function of autonomic cardiac activation. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:154–164. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199503000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Petty RE. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 19. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 123–205. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Kashy DA. Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM: A user-friendly guide. Pers Relatsh. 2002;9:327–342. [Google Scholar]

- Cassel J. The contribution of the social environment to host resistance. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;104:107–123. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb S. Social support as moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med. 1976;38:300–314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychol. 1988;7:269–297. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein RJ, Kamarck T, Hoberman HM. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: Theory, research, and applications. The Hague, the Netherlands: Martinus, Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, McKay G. Social support, stress, and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In: Baum A, Taylor SE, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of psychology and health. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Madson L. Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychol Bull. 1997;122(1):5–37. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW. Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In: Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GR, editors. Social support: An interactional view, Wiley series on personality processes. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 319–366. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(3):355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty J, Richman J. Gender differences in the perception and utilization of social support: Theoretical perspective and an empirical test. Soc Sci Med. 1989;28(12):1221–1228. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galecki AJ. General class of covariance structures for two or more repeated factors in longitudinal data analysis. Commun Stat Theory Methods. 1994;23:3105–3119. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C. In a different voice. Cambridge: MA: Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin J, Bilous M, Winship S, Finn P, Jones SC. Validation of the Oscar 2 oscillometric 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitor according to the British Hypertension Society Protocol. Blood Press Monit. 2007;12:113–117. doi: 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3280acab1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller K, Swindle RW, Dusenbury L. Component Social Support Processes: Comments and Integration. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54(4):466–470. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson J, Mant J, Martin U, Guo B, Hobbs FDR, Deeks JJ, McManus RR. Relative effectiveness of clinic and home blood pressure monitoring compared with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in diagnosis of hypertension: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;342:d362. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Birmingham W, Jones B. Is there something unique about marriage? The relative impact of marital status, relationship quality, and network social support on ambulatory blood pressure and mental health. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(2):239–244. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9018-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarck TW, Shiffman SM, Smithline L, Goodie JL, Paty JA, Gnys M, Yi-Kuan JJ. Effects of task strain, social conflict, and emotional activation on ambulatory cardiovascular activity: Daily life consequences of recurring stress in a multiethnic adult sample. Health Psychol. 1998;17:17–29. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul M, Lakey B. Where is the support in perceived support? The role of generic relationship satisfaction and enacted support in perceived support’s relation to low distress. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2003;22(1):59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, Brimm EB, Giovannucci E, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. A prospective study of social networks in relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease in men in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1996;50:245–251. doi: 10.1136/jech.50.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: his and hers. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(4):472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KB, Reis HT, Porter LA, Norsen LH. Social support and long-term recovery from coronary artery surgery. Health Psychol. 1993;12(1):56–63. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B, Cassady PB. Cognitive processes in perceived social support. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59(2):337–343. [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B, Lutz CJ. Social support and preventive and therapeutic interventions. In: Pierce GR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG, editors. Handbook of social support and the family. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 435–465. [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau JP, Feldman Barrett L, Pietromonaco PR. Intimacy as an interpersonal process: The importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(5):1238–1251. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurenceau JP, Feldman Barrett L, Rovine MJ. The interpersonal process model of intimacy in marriage: A daily-diary and multilevel modeling approach. J Fam Psychol. 2005;19:314–323. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden W, Chambers L, Maurice J, Lenz JW. Sex differences in social support, self-deception, hostility, and ambulatory cardiovascular activity. Health Psychol. 1993;12(5):376–380. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.5.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD. SAS system for mixed models. Cary, NC: SAS institute Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibund K, Jowett S, Barton P, Caulfield M, Heneghan C, Hobbs R, McManus R. Cost-effectiveness of options for the diagnosis of high blood pressure in primary care: a modeling study. Lancet. 2011;378:1219–1230. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marler MR, Jacob RG, Lehoczky JP, Shapiro AP. The statistical analysis of treatment effects in 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure recordings. Stat Med. 1988;7:697–716. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason PJ, Manson JE, Sesso HD, Albert CM, Chown MJ, Cook NR, Greenland P, Ridker PM, Glynn RJ. Blood pressure and risk of secondary cardiovascular events in women: The Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study (WACS) Circulation. 2004;109(13):1623–1629. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124488.06377.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor S. Hypertension diagnosis should be based on ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, NICE recommends. BMJ. 2011;343:d5421. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, Collins R, Sorlie P, Neaton J, Abbott R, Godwin J, Dyer A, Stamler J. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease: Part 1, prolonged differences in blood pressure: Prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990;335:765–774. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff LA, Karney BR. Gender differences in social support: A question of skill or responsiveness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88(1):79–80. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB. An introduction to multilevel modeling for social and personality psychology. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2008;2:842–860. [Google Scholar]

- Orth-Gomer K, Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L. Lack of social support and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged Swedish men. Psychosom Med. 1993;55(1):37–43. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park T, Lee YJ. Covariance models for nested repeated measures data: Analysis of ovarian steroid secretion data. Stat Med. 2002;21:143–164. doi: 10.1002/sim.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BWJH, van Tilburg T, Kriegsman DMW, Deeg DJH, Boeke AJP, van Eijk JTM. Effects of social support and personal control resources on mortality in older age: The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:510–519. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perloff D, Sokolow M, Cowan R. The prognostic value of ambulatory blood pressure. JAMA. 1983;249:2793–2798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering T, Harshfield G, Devereux R, Laragh J. What is the role of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the management of hypertensive patients? Hypertension. 1985;7:171–177. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.7.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psaty BM, Furberg CD, Kuller LH, Cushman M, Savage PJ, Levine D, O’Leary DH, Bryan RN, Anderson M, Lumley T. Association between blood pressure level and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and total mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1183–1192. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT. Steps toward the ripening of relationship science. Pers Relatsh. 2007;14:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Wheeler L. Studying social interaction with the Rochester Interaction Record. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 24. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 270–318. [Google Scholar]

- Sanbonmatsu DM, Uchino BN, Birmingham W. On the importance of knowing your partner's views: Attitude familiarity is associated with better interpersonal functioning and lower ambulatory blood pressure in daily life. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:131–137. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9234-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Pierce GR, editors. Social support: An Interactional View. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JE, Stone AA. Strategies for analyzing ecological momentary assessment data. Health Psychol. 1998;17:6–16. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE. Social ties and health: The benefits of social integration. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6(5):442–451. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker SA, Brownell A. Toward a theory of social support: Closing conceptual gaps. J Soc Issues. 1984;40(4):11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker SA, Hill DR. Gender differences in social support and physical health. Health Psychol. 1991;10(2):102–111. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD. Using SAS PROC MIXED to fit multilevel models, hierarchical models, and individual growth models. J Educ Behav Stat. 1998;23:323–355. [Google Scholar]

- Slavin LA, Rainer KL. Gender differences in emotional support and depressive symptoms among adolescents: A prospective analysis. Am J Community Psychol. 1990;18(3):407–420. doi: 10.1007/BF00938115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A. Stress, social support and cardiovascular activity over the working day. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000;37(3):299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Lundwall K, Cropley M. Gender, family structure and cardiovascular activity during the working day and evening. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(4):531–539. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(2):145–161. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trobst KK. An interpersonal conceptualization and quantification of social support transactions. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2000;26(8):971–986. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of our relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2004. . [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Understanding the links between social support and health: A life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2009;4:236–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Bowen K, Carlisle M, Birmingham W. What are the Psychological Pathways Linking Social Support to Health Outcomes? A Visit with the "Ghosts" of Research Past, Present, and Future. Soc Sci Med. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.023. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vella EJ, Kamarck TW, Shiffman S. Hostility moderates the effects of social support and intimacy on blood pressure in daily social interactions. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):S155–S162. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HM, Beal DJ, Lucy SL, MacDermid SM. Constructing EMA studies with PMAT: The Purdue Momentary Assessment Tool User's Manual. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Military Family Research Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Supportive functions of interpersonal relationships. In: Cohen S, Syme LS, editors. Social support and health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Social support and interpersonal relationships. In: Clark MS, editor. Prosocial behavior: Review of personality and social psychology. Vol. 12. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1991. pp. 265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Shinar O. Measuring perceived and received social support. In: Cohen S, Gordon L, Gottlieb B, editors. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 86–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DK, Ampey-Thornhill G. The role of gender and family support on dietary compliance in an African American adolescent hypertension prevention study. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23(1):59–67. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2301_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DK, Kliewer W, Bayer L, Jones D, Welleford A, Heiney M, Sica DA. The influence of gender and emotional versus instrumental support on cardiovascular reactivity in African-American adolescents. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(3):235–243. doi: 10.1007/BF02884840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58(19) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]