Abstract

Objective

To establish whether cannabis is an effective and safe treatment option in the management of pain.

Design

Systematic review of randomised controlled trials.

Data sources

Electronic databases Medline, Embase, Oxford Pain Database, and Cochrane Library; references from identified papers; hand searches.

Study selection

Trials of cannabis given by any route of administration (experimental intervention) with any analgesic or placebo (control intervention) in patients with acute, chronic non-malignant, or cancer pain. Outcomes examined were pain intensity scores, pain relief scores, and adverse effects. Validity of trials was assessed independently with the Oxford score.

Data extraction

Independent data extraction; discrepancies resolved by consensus.

Data synthesis

20 randomised controlled trials were identified, 11 of which were excluded. Of the 9 included trials (222 patients), 5 trials related to cancer pain, 2 to chronic non-malignant pain, and 2 to acute postoperative pain. No randomised controlled trials evaluated cannabis; all tested active substances were cannabinoids. Oral delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) 5-20 mg, an oral synthetic nitrogen analogue of THC 1 mg, and intramuscular levonantradol 1.5-3 mg were about as effective as codeine 50-120 mg, and oral benzopyranoperidine 2-4 mg was less effective than codeine 60-120 mg and no better than placebo. Adverse effects, most often psychotropic, were common.

Conclusion

Cannabinoids are no more effective than codeine in controlling pain and have depressant effects on the central nervous system that limit their use. Their widespread introduction into clinical practice for pain management is therefore undesirable. In acute postoperative pain they should not be used. Before cannabinoids can be considered for treating spasticity and neuropathic pain, further valid randomised controlled studies are needed.

What is already known on this topic

Three quarters of British doctors surveyed in 1994 wanted cannabis available on prescription

Humans have cannabinoid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous system

In animal testing cannabinoids are analgesic and reduce signs of neuropathic pain

Some evidence exists that cannabinoids may be analgesic in humans

What this study adds

No studies have been conducted on smoked cannabis

Cannabinoids give about the same level of pain relief as codeine in acute postoperative pain

They depress the central nervous system

Introduction

The recent clamour for wider access to cannabis or cannabinoids as analgesics in chronic painful conditions has some logic. Humans have cannabinoid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous system,1 although the functions of these receptors and the endogenous ligands may yet be unclear. In animal testing cannabinoids reduce the hyperalgesia and allodynia associated with formalin, capsaicin, carrageenan, nerve injury, and visceral persistent pain.2 The hope then is that exogenous cannabis or cannabinoid may work as analgesics in pain syndromes that are poorly managed. The spasms of multiple sclerosis and resistant neuropathic pain are two obvious targets.

The background to this debate about legitimising cannabis (also called marijuana)—from the plant Cannabis sativa—for analgesic use is that the drug has been used both therapeutically and recreationally for thousands of years.3 In Britain doctors were able to prescribe cannabis as recently as 1971,4 and in a 1994 survey 74% of UK doctors wanted cannabis to be available on prescription, as it had been until 1971.5 The debate has included both the natural chemicals that act on cannabinoid receptors and the synthetic cannabinoids. The synthetic nabilone is the only legally available cannabinoid preparation in the United Kingdom and is licensed solely for use in nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the most potent cannabinoid, and although it is available in the United States, it is not licensed for use in the United Kingdom.

The evidence used in the public debate about the analgesic efficacy of cannabinoids in humans has been gathered in a less than systematic manner and has often been taken from low quality study designs, such as anecdotal reports, questionnaires, or case series.4 The purpose of this systematic review was to find all of the randomised controlled trials of therapeutic use of cannabis in the management of human pain and then to obtain the best estimates of the efficacy of cannabis compared with either conventional analgesics or placebo. We also sought evidence of adverse effects (safety).

Cannabis is used recreationally because of the euphoria that it produces. The adverse psychological effects (including psychomotor and cognitive impairment; anxiety and panic attacks; and acute psychosis and paranoia) may limit therapeutic use.6 Other adverse physical effects include dry mouth, blurred vision, palpitations, tachycardia, and postural hypotension.3

Decisions about therapeutic cannabinoids, either about medical availability or about future research, should be based on the best available evidence of efficacy, safety, and tolerability. This systematic review was designed to provide that evidence for cannabinoids used as analgesics.

Methods

Searching

Two authors (MRT and DC) searched independently, using different search strategies in Medline (for 1966-99), Embase (1974-99), the Oxford Pain Database (1950-94),7 and the Cochrane Library (1999, issue 3). The most recent search was done in October 1999. The search included different combinations of the following MeSH headings and “free text” terms: marijuana, marihuana, mariuana, cannabis, cannabinoids, THC, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, nabilone, pain, analgesia, and random*, and different combinations of these terms. Additional reports were identified from the reference lists of retrieved reports and review articles. The search included data in any language. Pharmaceutical manufacturers and authors were not contacted. Only full publications in peer reviewed journals were considered for inclusion in the review. Unpublished data were not sought. Data from review articles, case reports, abstracts, and letters were not included.

Selection and validity assessment

Randomised controlled trials of cannabis and its active constituents (namely, cannabinoids) in human pain were sought systematically. Studies of experimental pain were excluded. Relevant papers had to report on comparisons of cannabis or cannabinoids (experimental intervention, given by any route of administration) with any analgesic or placebo (control intervention).

All retrieved reports were checked for inclusion and exclusion criteria by two authors (MRT, DC). Reports that were definitely not relevant were excluded at this stage. All potentially relevant reports that could be described as a randomised controlled trial were read independently by each of the authors and were scored for quality with the validated, 3 item Oxford scale.8 This scale takes into account proper randomisation, double blinding, and reporting of withdrawals and dropouts.

Data extraction

Data extraction was done by one author (FAC) and cross checked by at least two other reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Study characteristics

The following information was extracted from each report: the type, dose, and route of administration of cannabinoids; the controls; the types of pain; the sample size; the study design and duration; outcome measures for pain intensity; pain relief; the use of supplementary analgesia; patients' preferences; and adverse effects.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative meta-analysis with pooling of data from the eligible randomised controlled trials was proposed.

Results

Trial flow

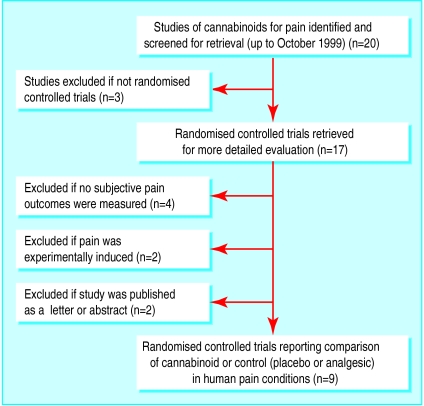

The results of the searches are presented in the figure. The presentation follows the suggested format provided in the QUORUM statement.9 Of the 11 excluded trials, three did not use randomised treatment comparisons,10–12 four did not use subjective pain outcomes,13–16 two had studied experimentally induced pain,17,18 and one was published as a letter19 and one as an abstract.20

Study characteristics

Details from nine randomised controlled trials published in seven reports published between 1975 and 1997 were analysed (table).21–27 The nine randomised controlled trials comprised a total of 222 adult patients. Five studies that were described in four reports comprised 128 patients with cancer pain.21–24 Two studies comprised two patients with chronic non-malignant pain (one patient per trial),25,26 and two trials (conducted as a two phase study) comprised six patients with postoperative pain.27 Follow up was six to seven hours in seven trials and six weeks and five months respectively in the two trials on chronic non-malignant pain.25,26 The number of patients in treatment groups ranged from 1 to 37. All studies used a crossover design except the study of postoperative pain.27 The two studies in chronic pain used an “n of 1 within patient crossover” design.25,26 Seven studies described in five reports were single dose evaluations of the analgesic effectiveness of cannabinoids.21–24,27 The median quality score of the trials was 3 (range 3-4) (possible score 0-5). All studies included a placebo group. An adequate method of blinding—for example, tablets of identical shape, colour, and taste—was used in all trials where treatments were given orally. There was no explicit description of the method of blinding in the phase 1 and 2 trials comparing intramuscular levonantradol with placebo in postoperative pain.27

Four different cannabinoids were tested: oral THC 5-10 mg,22,23,25,26 an oral synthetic nitrogen analogue of THC (NIB) 4 mg,24 oral benzopyranoperidine (BPP) 2-4 mg,21 and intramuscular levonantradol 1.5-3 mg.27 No study evaluated the analgesic effects of cannabis (marijuana) or other inhaled or smoked cannabinoids. Active treatment comparators were oral codeine 50-120 mg21,23,24,26 and oral secobarbital 50 mg.24

Because of the different cannabinoids, regimens, and comparators, numerous clinical settings, different follow up periods, and a large variety of outcome measures used in these trials, pooling of data for meta-analysis was inappropriate. Results were therefore summarised qualitatively.

Cancer pain

In the five trials on cancer pain 128 patients were studied (table). In one study oral benzopyranoperidine (a THC congener) 2-4 mg was not as effective as codeine sulphate 60-120 mg and no more effective than placebo in 37 patients.21 Oral THC 5-20 mg was found to have an analgesic effect when compared with placebo in 10 patients with pain related to advanced cancer.22 In this study a dose-response relation was shown for analgesia but also for adverse effects. In a further study by the same group oral THC 10 mg was found to be about equipotent to codeine 60 mg, and THC 20 mg was about equipotent to codeine 120 mg.23 The higher dose was associated with unacceptable adverse effects. In one trial a synthetic nitrogen analogue of THC given orally was superior to placebo and equivalent to about 50 mg of codeine phosphate.24 In a second study in the same report this nitrogen analogue was found to be superior to placebo and to 50 mg of secobarbital.24 In both of these trials the nitrogen analogue of THC was felt to be not clinically useful because of the frequency of adverse effects.

Chronic non-malignant pain

Two patients were studied in two “n of 1 within patient crossover” trials for six weeks and five months respectively (table). In an experienced cannabis user with familial Mediterranean fever, THC was found to be no better than placebo in terms of visual analogue scores for pain intensity.25 Level of morphine use for breakthrough pain was significantly lower, however, while the patient was taking THC than while taking placebo (170 mg v 410 mg per three weeks). In a patient with neuropathic pain and spasticity secondary to a spinal cord ependymoma, THC 5 mg and codeine 50 mg were equianalgesic, and both were superior to placebo.26 Only THC, however, had a beneficial effect on spasticity.

Postoperative pain

Thirty six patients were studied in two trials (conducted as a two phase study) (table).27 Levonantradol was more effective than placebo when given intramuscularly to patients with postoperative pain.27 Adverse effects with levonantradol were common, although considered mild.

Cannabinoids and adverse effects

Adverse effects were reported in all studies. Two patients withdrew from studies owing to adverse effects of THC.23 THC showed a dose-response relation for adverse effects—for example, mental clouding, ataxia, dizziness, numbness, disorientation, disconnected thought, slurred speech, muscle twitching, impaired memory, dry mouth, and blurred vision—and at 20 mg was highly sedating in 100% of patients, thus prohibiting its use.23 THC 10 mg was better tolerated, but the frequency of these adverse effects was still higher than with codeine 60 mg or 120 mg.23 Reductions in arterial blood pressure occurred compared with placebo, but no more than with codeine. Changes in heart rate were not significant. THC 5 mg was well tolerated in neuropathic pain and did not cause an altered state of consciousness.26 Levonantradol caused adverse effects in most patients, but none withdrew.27 The nitrogen analogue of THC did not affect heart rate but caused drowsiness in 40% of patients and was therefore deemed not clinically useful.24 Benzopyranoperidine caused a similar degree of sedation to codeine but was ineffective as an analgesic.21

Discussion

We found nine randomised trials evaluating the analgesic efficacy and safety of cannabinoids. These trials, of either acute or chronic pain, suggest that little useful analgesia can be expected from single dose cannabis in nociceptive pain.

All the trials had a quality score of 3 or above and therefore are unlikely to be biased. They were predominantly single dose experiments. In eight of the nine trials intramuscular and oral cannabinoids were more effective analgesics than placebo but no more effective than oral codeine 50-120 mg.

Acute pain

In the two postoperative pain trials levonantradol was superior to placebo but no more effective than codeine.27 Such a level of efficacy makes cannabinoids unlikely to be useful, certainly for moderate or severe postoperative pain. Meta-analyses of single dose studies in patients with acute pain found that the number needed to treat for at least 50% pain relief ranged from 2 to 5 compared with placebo for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and paracetamol. The number needed to treat for codeine 60 mg was much less useful, at 16.28 If cannabinoids can deliver analgesia only equivalent to codeine 60 mg, with a presumed number needed to treat of about 16 for at least 50% pain relief, they are unlikely to have a place in acute pain treatment.

Cancer and non-malignant pain

No large trials examined cannabinoids in cancer pain and chronic non-malignant pain. Only two trials had treatment group sizes of more than 30.21,23 All five trials in cancer pain were single dose, and four found the cannabinoid as effective as codeine, but with dose limiting adverse effects.22,23,24 Benzopyranoperidine, tested in one trial, was ineffective compared with both codeine and placebo.21 In chronic non-malignant pain we found two “n of 1 within patient crossover” trials. In a patient with abdominal pain related to familial Mediterranean fever, neither THC nor placebo produced pain relief, but with THC the patient used less additional morphine for breakthrough pain.25 In Maurer et al's n of 1 study of THC 5 mg for neuropathic pain and spasticity, the reduction in pain intensity was similar to that for codeine 50 mg, but only THC reduced spasticity.26 We found no trials evaluating smoked cannabis for pain management, but one trial compared the effect of smoked marijuana with smoked placebo on postural balance in patients with spastic multiple sclerosis.16 The smoked marijuana was associated with subjective improvement of symptoms and with objectively measured impaired posture and balance in all subjects.

Adverse effects

Adverse effects associated with the cannabinoids were common and sometimes severe in six of the eight trials that showed efficacy. The predominant adverse effect seemed to be depression of the central nervous system. Cardiovascular effects were generally mild and well tolerated. Levonantradol was commonly associated with adverse effects (predominantly drowsiness or sedation, or both), of which over half were considered to be moderate or severe. THC 10-20 mg showed a dose-response relation for adverse effects, with depressant effects on the central nervous system occurring in most patients receiving either dose. In Holdcroft et al's patient25 no adverse effects were attributable to THC 50 mg a day, but the patient was an experienced cannabis user. Maurer et al's patient experienced no altered state of consciousness taking THC 5 mg for neuropathic pain; the cannabinoids might be stimulant at low doses and depressant at higher doses, and perhaps this was the reason for lack of sedation in this patient.26 The nitrogen analogue of THC had a side effect profile similar to codeine.24 This cannabinoid was as sedating as secobarbital, which has no analgesic properties, thus it is unlikely that any sedation caused by cannabinoids contributes to their analgesic effect. Other studies have shown that barbiturates and tranquillisers given with analgesics contribute nothing to pain relief.29

Conclusion

The best that can be achieved with single dose cannabis in nociceptive pain is analgesia equivalent to single dose codeine 60 mg, which rates poorly on relative efficacy compared with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or simple analgesics. Increasing the cannabinoid dose to increase the analgesia will increase adverse effects. More intriguing perhaps than these relatively negative analgesic results in nociceptive pain are the suggestions of efficacy in spasticity and in neuropathic pain, where the therapeutic need is greater than in postoperative pain.

We found insufficient evidence to support the introduction of cannabinoids into widespread clinical practice for pain management—although the absence of evidence of effect is not the same as the evidence of absence of effect. Any research agenda needs to be clear, however, and this review may be helpful in defining the agenda. Cannabis is clearly unlikely to usurp existing effective treatments for postoperative pain. New safe and effective agonists at the cannabinoid receptor may dissociate therapeutic from psychotropic effects and make randomised comparisons in neuropathic pain and spasticity worth while.

Figure.

Results of search of Medline, Embase, Oxford Pain Database, Cochrane Library, references on identified papers; and hand searches for work on cannabinoids and pain

Table.

Analysis of nine randomised controlled trials of effectiveness of cannabinoids for three types of pain (cancer pain, chronic non-malignant pain, and postoperative pain)

| Trial | Study chacterisitcs | Quality score (randomisation, blinding, withdrawals) | Intervention (oral unless indicated otherwise) | Efficacy data

|

Adverse drug reactions

|

Comments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain relief (total pain relief or AUDC) | Pain intensity (SPID orVAS) | Other | Quantitatively | Qualitatively | |||||||

| Cancer pain | |||||||||||

| Jochimsen et al21 | n=37 (35 analysed); crossover design; pain: cancer (moderate baseline pain); follow up 6 hours | 1, 2, 0 | BPP 2 mg x 1; BPP 4 mg x 1; codeine 60 mg x 1; codeine 120 mg x 1; placebo x 1 | Complete: BPP 2 mg 2/35; BPP 4 mg 3/35; codeine 60 mg 9/35; codeine 120 mg 8/35; placebo 4/35 | Reduced: BPP 2 mg 19/35; BPP 4 mg 20/35; codeine 60 mg 25/35; codeine 120 mg 31/35; placebo 25/35 | 11 item self assessment scale showed no difference in psychotomimetic effect. Sedation for both doses of BPP similar to both doses of codeine. No difference in blood pressure, heart rate, psychiatric interview | 37 patients entered, 35 completed ( no reason given for 2 who did not complete); analgesic effect of codeine 120 mg better than placebo, BPP 4 mg worse than placebo; adverse effects not significantly different | ||||

| Noyes et al22 | n=10 (9 analysed); crossover design; pain: cancer (moderate baseline pain); follow up 6 hours | 1, 2, 0 | THC 5 mg x 1; THC 10 mg x 1; THC 15 mg x 1; THC 20 mg x 1; placebo x 1 | Total (mean±SE): THC 5 mg 4.7±0.95; THC 10 mg 4.4±0.98; THC 15 mg 5.8±0.84; THC 20 mg 10.8±1.19; placebo 5.1±1.65; | SPID (mean±SE): THC 5 mg 2.6±0.53; THC 10 mg 1.4±0.42; THC 15 mg 3.6±0.65; THC 20 mg 4.6±0.66; placebo 0.9±0.3 | Progressive pain relief with increasing doses of THC (P<0.001) | No of reactions per 10 patients: THC 5 mg 37; THC 10 mg 47; THC 15 mg 64; THC 20 mg 70; placebo 16 | Progressive sedation and mental clouding (THC 20 mg caused heavy sedation in all patients); reduced blood pressure and heart rate; euphoria in 2 patients receiving THC 15 mg and 20 mg, 1 of whom was the only experienced marijuana user | Dose response for analgesia and adverse effects with THC | ||

| Noyes et al23 | n=36 (34 analysed); crossover design; pain: cancer (moderate baseline pain); follow up 7 hours | 1, 2, 0 | THC 10 mg x 1; THC 20 mg x 1; codeine 60 mg x 1; codeine 120 mg x 1; placebo x 1 | Total (mean±SE): THC 10 mg 9.8±1.40; THC 20 mg 12.9±1.46; codeine 60 mg 9.4±1.38; codeine 120 mg 12.2±1.57; placebo 6.8±0.95; P<0.05=THC 20 mg and codeine 120 mg v placebo | SPID (mean±SE): THC 10 mg 2.9±0.62; THC 20 mg 4.7±0.65; codeine 60 mg 3.6±0.75; codeine 120 mg 4.3±0.78; placebo 1.9±0.44; P<0.05 for THC 20 mg and codeine 120 mg v placebo | Analgesic effect of THC in 5 hours, codeine in 3 hours | No of reactions per 34 patients: THC 10 mg 186; THC 20 mg 259; codeine 60 mg 120; codeine 120 mg 13; placebo 92. Withdrawal owing to reactions: THC 2; codeine or placebo 0 | Reduced blood pressure with THC | THC 20 mg highly sedating and produced mental effects prohibiting its use. THC 10 mg was well tolerated and somewhat sedating, but only equipotent to codeine 60 mg | ||

| Staquet et al (study 1)24 | n=30 (26 analysed); crossover design; pain: cancer (moderate baseline pain); follow up 6 hours | 1, 2, 1 | NIB 4 mg x 1; codeine 50 mg x 1; placebo x 1 | No data | SPID (mean±SE): NIB 4.72±3.33; codeine 4.79±3.19; placebo 2.15±2.56; P<0.05 for NIB and codeine v placebo | Drowsiness (% of patients): NIB 40%; codeine 44%; placebo 21% | 4 withdrawals unrelated to study drug | ||||

| Staquet et al (study 2)24 | n=15 (15 analysed); crossover design; pain: cancer (moderate baseline pain); follow up 6 hours | 1, 2, 1 | NIB 4 mg x 1; secobarbital 50 mg x 1; placebo x 1 | No data | SPID (mean±SE): NIB 4.40±2.06; secobarbital 2.13±1.77; placebo 1.87±1.30; P<0.05 for NIB v secobarbital and placebo | Drowsiness: (% of patients): NIB 40%; secobarbital 33%; placebo 21% | Secobarbital did not reduce pain intensity more than placebo, indicating that hypnotic properties do not imply pain relief | ||||

| Chronic non-malignant pain | |||||||||||

| Holdcroft et al25 | n=1; n of 1 crossover design; pain: abdominal (Mediterranean fever); follow up 6 weeks | 1, 2, 0 | THC 10 mg x 5 capsules/day; placebo x 5 capsules/day (each treatment 1 week) | No data | VAS (ranges): THC 4.8-6.2 mm; placebo 5.5-6.1 mm; NS | Daily morphine consumption less in THC group (P<0.001) | Nausea and vomiting throughout study;dysphoria and irritability associated with placebo weeks | Experienced cannabis user able to identify THC capsules for first 4 weeks of trial | |||

| Maurer et al26 | n=1; n of 1 crossover design; pain: spinal cord pathology; follow up 5 months | 1, 2, 0 | THC 5 mg x 18; codeine 50 mg x 18; placebo x 18 | No data | VAS (50 mm scale): THC 25.6 mm; codeine 19.7 mm; placebo 34.3 mm; P<0.05 for THC and codeine v placebo | THC had only antispasticity effect | THC and codeine better than placebo for mood, sleep, concentration, control of micturition, global effect; no altered state of consciousness | ||||

| Postoperative pain | |||||||||||

| Jain et al (phase 1)27 | n=36 (36 analysed); parallel group design; pain: postoperative or trauma (moderate to severe pain); follow up 6 hours | 1, 1, 1 | Intramuscular: levonantradol 1.5 mg x 1; levonantradol 2.0 mg x 1; placebo x 1 | AUDC: P<0.05 for levonantradol v placebo at each dose | AUDC: P<0.05 for levonantradol v placebo at each dose | No of patients with reactions: levonantradol 23/40; placebo 2/16 | Drowsiness common | ||||

| Dry mouth, dizziness, and dysphoria uncommon | |||||||||||

| Levonantradol: increased heart rate and reduced blood pressure (no dose response) | |||||||||||

| Jain et al (phase 2)27 | n=36 (36 analysed); parallel group design; pain: postoperative or trauma (moderate baseline pain); follow up 6 hours | 1, 1, 1 | Intramuscular: levonantradol 2.5 mg x 1; levonantradol 3.0 mg x 1; placebo x 1 | AUDC: P<0.05 for levonantradol v placebo at each dose | AUDC: P<0.05 for levonantradol v placebo at each dose | ||||||

BPP=benzopyranoperidine;THC=9-delta-tetrahydrocannabinol; NIB=nitrogen analogue THC.

AUDC=areas under the difference curves (sum of change from baseline to six hours for pain intensity, pain relief, and pain analgesic scores).

SPID=summed pain intensity difference.

VAS=visual analogue scale.

Footnotes

Funding: MRT was supported by a PROSPER grant from the Swiss National Research Foundation (No 3233-051939.97). DC was supported by the Royal College of Nursing Institute's Research Assessment Exercise grant.

Competing interests: None declared. DC is currently employed by Pfizer; the change of employment occurred after the work in this study was completed.

References

- 1.Martin WJ, Loo CM, Basbaum AI. Cannabinoids are anti-allodynic in rats with persistent inflammation. Pain. 1999;82(2):199–205. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin WJ. Basic mechanisms of cannabinoid-induced analgesia. IASP Newsletter 1999;summer:3-6.

- 3.Ashton CH. Adverse effects of cannabis and cannabinoids. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83:637–649. doi: 10.1093/bja/83.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.BM Association. Therapeutic uses of cannabis. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meek C. Doctors want cannabis prescriptions allowed. BMA News Review 1994;February:1-19.

- 6.Tramèr MR, Carroll D, Campbell FA, Reynolds DJM, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Cannabinoids for control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: quantitative systematic review. BMJ. 2001;323:16–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jadad AR, Carroll D, Moore A, McQuay H. Developing a database of published reports of randomised clinical trials in pain research. Pain. 1996;66:239–246. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUORUM statement. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark WC, Janal MN, Zeidenberg P, Nahas GG. Effects of moderate and high doses of marihuana on thermal pain: a sensory decision theory analysis. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21(suppl 8-9):S299–S310. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill SY, Schwin R, Goodwin DW, Powell BJ. Marihuana and pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1974;188:415–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petro DJ, Ellenberger C., Jr Treatment of human spasticity with delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21(suppl 8-9):S413–S416. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aronow WS, Cassidy J. Effect of marihuana and placebo-marihuana smoking on angina pectoris. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:65–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197407112910203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ungerleider JT, Andyrsiak T, Fairbanks L, Ellison GW, Myers LW. Delta-9-THC in the treatment of spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis. Adv Alcohol Subst Abuse. 1987;7(1):39–50. doi: 10.1300/j251v07n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Consroe P, Laguna J, Allender J, Snider S, Stern L, Sandyk R, et al. Controlled clinical trial of cannabidiol in Huntington's disease. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;40:701–708. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90386-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberg HS, Werness SA, Pugh JE, Andrus RO, Anderson DJ, Domino EF. Short-term effects of smoking marijuana on balance in patients with multiple sclerosis and normal volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55:324–328. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raft D, Gregg J, Ghia J, Harris L. Effects of intravenous tetrahydrocannabinol on experimental and surgical pain. Psychological correlates of the analgesic response. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1977;21(1):26–33. doi: 10.1002/cpt197721126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milstein SL, MacCannell K, Karr G, Clark S. Marijuana-produced changes in pain tolerance. Experienced and non-experienced subjects. Int Pharmacopsychiatry. 1975;10:177–182. doi: 10.1159/000468188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martyn CN, Illis LS, Thom J. Nabilone in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1995;345:579. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kantor TG, Hopper M. A study of levonantradol, a cannabinol derivative, for analgesia in post operative pain. Pain. 1981;(suppl):S37. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jochimsen PR, Lawton RL, VerSteeg K, Noyes R., Jr Effect of benzopyranoperidine, a delta-9-THC congener, on pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1978;24:223–227. doi: 10.1002/cpt1978242223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noyes R, Jr, Brunk SF, Baram DA, Canter A. Analgesic effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Clin Pharmacol. 1975;15:139–143. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1975.tb02348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noyes R, Jr, Brunk SF, Avery DAH, Canter AC. The analgesic properties of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and codeine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1975;18(1):84–89. doi: 10.1002/cpt197518184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staquet M, Gantt C, Machin D. Effect of a nitrogen analog of tetrahydrocannabinol on cancer pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1978;23:397–401. doi: 10.1002/cpt1978234397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holdcroft A, Smith M, Jacklin A, Hodgson H, Smith B, Newton M, et al. Pain relief with oral cannabinoids in familial Mediterranean fever. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:483–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1997.139-az0132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maurer M, Henn V, Dittrich A, Hofmann A. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol shows antispastic and analgesic effects in a single case double-blind trial. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1990;240(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02190083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain AK, Ryan JR, McMahon FG, Smith G. Evaluation of intramuscular levonantradol and placebo in acute postoperative pain. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21(suppl 8-9):S320–S326. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McQuay HJ, Moore RA. An evidence-based resource for pain relief. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moertel CG, Ahmann DL, Taylor WF, Schwartau N. Relief of pain by oral medications. A controlled evaluation of analgesic combinations. JAMA. 1974;229:55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]