Abstract

OBJECTIVE(S)

To determine if endothelial microparticles (EMPs), markers of endothelial damage, are associated with soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1), soluble endoglin (sEnd), and placental growth factor (PlGF) in women with preeclampsia. STUDY DESIGN: A prospective cohort study was conducted on 20 preeclamptic women and 20 controls. EMP’s measured by flow cytometry, sFlt1, sEnd, and PlGF were measured at time of enrollment, 48 hours, and 1 week postpartum.

RESULTS

Preeclamptic CD31+/42−, CD 62E+, and CD105+ EMP levels were significantly elevated in preeclamptics vs. controls at time of enrollment. The sFlt1:PlGF ratio was correlated with CD31+/42− and CD 105+ EMPs (r=0.69 and r=0.51, respectively) in preeclampsia. Levels of CD31+/42− EMPs remained elevated 1-week postpartum (p=0.026).

CONCLUSIONS

EMPs are elevated in preeclampsia. The correlation of EMPs and the sFlt1:PlGF ratio suggests that anti-angiogenesis is related to apoptosis of the endothelia. Endothelial damage persists one week after delivery.

Keywords: Endothelial microparticles, preeclampsia, pregnancy, sFlt:PlGF ratio, soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1)

Introduction

Preeclampsia is a hypertensive disease of pregnancy that manifests as blood pressure elevation with new-onset proteinuria occurring after the 20th week of gestation.1 This disease complicates up to 7% of pregnancies, accounting for significant maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. The pathophysiologic insult occurring in preeclampsia is thought to be diffuse endothelial cell dysfunction and injury.2-4 This endothelial insult, and thereby the clinical manifestations of preeclampsia, appear to be related to the release of circulating factors from the placenta and their effects on the maternal vasculature.5-6 Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) competitively binds to placental growth factor (PlGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), preventing their role in endothelial preservation. Soluble endoglin (sEnd) also serves as an anti-angiogenic protein and has been shown to prevent capillary tube formation and increase vascular permeability by inhibition of the TGF-B1 signaling pathway. The placenta produces sFlt1 and sEnd during normal pregnancy, but significantly higher amounts are produced from the hypoxic placenta in those pregnancies affected by preeclampsia. The presence of these proteins and their effect on PlGF and VEGF create an angiogenically imbalanced vascular environment that contributes to the endothelial insult occurring in preeclampsia. The role of the placenta in this process is further evidenced by the fact that the only true “cure” for preeclampsia is delivery, with symptoms resolving shortly after delivery. Typically sFlt1 and sEnd decrease rapidly after delivery; however the clearance rate is much longer in women with preeclampsia.7

Recent studies provide evidence that identification of circulating endothelial microparticles (EMPs) allows direct assessment of endothelial damage. EMPs are submicroscopic membranous particles that are shed from the endothelial cell wall upon endothelial disturbance and can be identified within the plasma by fluorescent antibody labeling of endothelial cell adhesion molecules retained on the surface of the liberated EMPs.8 Quantification via flow cytometry provides a direct measurement of endothelial damage.9 Moreover, phenotypic variability of the EMPs identified by differential expression of specific cell surface markers may suggest the underlying endothelial insult taking place.10 EMP elevations have been documented in disease states with known endothelial insult, including preeclampsia.11-12 The ability to directly assess endothelial insult allows the relationship between the maternal endothelial environment and the circulating anti-angiogenic factors in preeclampsia to be explored.

This study had 2 main objectives designed to examine both antepartum and postpartum endothelial function. First, we evaluated endothelial microparticles in the antepartum period as objective markers of endothelial damage in women with preeclampsia and determined if levels of liberated EMPs are related to the angiogenic and anti-angiogenic proteins associated with preeclampsia. Second, we evaluated EMP levels in the postpartum period to determine whether endothelial damage persists after delivery.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

A prospective, case-control study was conducted on 20 preeclamptic women and 20 healthy pregnant women recruited from Parkland Memorial Hospital and its affiliated prenatal care clinics between February 2009 through June 2010. Eligibility for enrollment included women with singleton gestations ≥36 weeks gestation. For study subjects, the diagnosis of preeclampsia was defined as blood pressure measurement ≥140/90 mmHg on two occasions within six hours in a previously normotensive woman and ≥2+ proteinuria in a catheterized urine specimen. These patients were recruited from the Labor & Delivery Unit at Parkland Memorial Hospital immediately following the diagnosis of preeclampsia and prior to the administration of magnesium sulfate. Control subjects were healthy pregnant women with singleton gestations, a normal blood pressure, and no proteinuria. These patients were recruited during their routine prenatal care visit and were matched to preeclamptic subjects for maternal age (± 2 years), gestational age at enrollment (± 1 week), and parity. Exclusion criteria for all participants included: preexisting hypertension, proteinuria prior to 24 weeks gestation, pre-gestational or gestational diabetes, renal or hepatic disease, or known fetal anomalies. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects, according to protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of University of Texas Southwestern and Parkland Memorial Hospital.

Collection of Blood Samples

Blood was collected at time of diagnosis of preeclampsia or study enrollment, 48 hours postpartum (±12 hours), and 1 week postpartum (±1 day). A manual blood pressure measurement was taken prior to venipuncture. Blood samples were collected without tourniquet in sterile 5mL sodium citrate tubes for microparticle analysis and 5mL EDTA tubes for ELISA analysis (BD Vacutainer Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Microparticle Analysis

Samples for microparticle analysis were assayed within two hours of venipuncture to avoid contamination with microparticles released ex vivo. To avoid freeze-thaw cycles, the microparticle samples were not frozen as we found similar to previous reports that freezing results in variability in microparticle measurements13. Centrifugation was carried out to obtain plasma depleted of platelets, cells known to release platelet-specfic microparticles. The samples were centrifuged 10 minutes at 0.1 g to prepare platelet-rich plasma (PRP). The PRP was centrifuged 6 minutes at 0.2 g, then 1 minute at 3.3g to obtain platelet-poor plasma (PPP). Aliquots of 50 μL of PPP were transferred into individual microcentrifuge tubes for antibody staining. For measurement of CD31+/42− EMP, the PPP was incubated with 1 μL of FITC-labeled anti-CD42 antibody and 2μL of PE-labeled anti-CD31 antibody (BD Pharmingen, Cat#555472 and 555446, respectively). Double labeling with anti-CD42b was for the exclusion of CD31+ microparticles of platelet origin. CD31+/CD45+ particles account for a negligible percentage of all CD31+ MP, which would represent a subpopulation of leukocyte microparticles that are not considered to significantly alter EMP counts.14 For measurement of CD62E+ and CD105+ EMP, the PPP was incubated with 0.5μL of PE-labeled CD62E antibody or 0.5μL of PE-labeled CD105 antibody (BD Pharmingen, Cat#551144 and Cat#560839, respectively). Antibody incubation time was 15 minutes, shielded from light with gentle orbital shaking. To facilitate removal of excess antibody, 500μL of filtered PBS was added to each sample following incubation. The samples were then centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 minutes at 20°C. Using a transfer pipette, 450 μL of supernatant was gently removed. The sedimented microparticles were re-suspended in 500 μL of filtered PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Two-color flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer equipped with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Thresholds for forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) were set to zero. FSC, SSC, and fluorescence channels were set at logarithmic gain. One μm beads provided the standard for FSC gate determination of microparticle size (Invitrogen, Cat #F-13838). Microparticles were then identified on the basis of their size, density and fluorescence. Analysis of each sample was performed for 45 seconds at medium flow rate. Three consecutive analyses were performed for each sample and the median event count deemed the final count. The absolute concentration of circulating microparticles was calculated using calibrator beads with known concentration added into the sample immediately prior to flow cytoanalysis (Bangs Laboratories, Cat #NT20N/9207). The final microparticle number was expressed as count per μL.

Protein Analysis

The serum samples utilized for measurement of sFlt1, sEnd and PlGF were centrifuged and stored at −70°C. The concentrations of sFlt1, sEnd, and PlGF were determined by using specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) following the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems, Inc, Minneapolis, MN). All samples were examined in duplicate and mean values of individual sera were utilized for statistical analysis. The minimum detectable doses in the assays for sFlt1, sEnd, and PlGF were 3.5, 7, and 7 pg/mL, respectively. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were 3.2 and 5.5 percent, respectively, for sFlt1; 3.0 and 6.3 percent, respectively, for sEnd; and 5.6 and 10.9 percent, respectively, for PlGF.

Statistical Analysis

A sample size of 20 study subjects per group was selected to allow with 80% power a detection of a difference of 5000 EMP/mL between preeclampsia and controls assuming a standard deviation of 5000 EMP/mL. Assumptions are based upon previously published studies.11 Control patients were matched to cases by maternal age, gestational age at enrollment, and parity as stated earlier. Demographic data are expressed as mean + standard deviation, analyzed using the Student’s t-test or expressed as frequency (percent), analyzed using the Pearson chi-square test. In the case of birth weight analysis of covariance was used to adjust the measure of association by gestational age. Endothelial microparticle data are not assumed to be statistically normal an assumption examined using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Consequently, two-group comparisons are made using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Correlations were estimated using the Spearman correlation. Confidence intervals of correlations are estimated using the Fisher’s transformation and the hypothesis of equality of correlation between groups uses the Student’s t-test again through the Fisher’s transformation. For the longitudinal results, data were transformed to statistical normality using the logarithmic transformation. Following transformation, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to substantiate that the transformation did indeed result in normal data. As some subjects did not have data in all three of the time epochs, the repeated measure of time is a random effect. Consequently, the analysis for these longitudinal data is a random effects model with subject grouping (preeclampsia or control) a fixed effect and the repeated measure for time as a random effect at fixed time points of “enrollment”, “two days postpartum”, and “one week postpartum”. Consequently, the study design is a repeated measures analysis of variance with the repeated measure as a random effect. If the overall statistic of the random effects model is significant for the fixed effect of subject grouping, then individual contrasts are examined for the cross-sectional comparisons at each time point. All analysis is conducted in the transformed logarithmic domain. Significance levels less than 0.05 are assumed to be significant. Statistical analyses are performed using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study subjects are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in maternal age, race, parity, gestational age at enrollment, or smoking. Women with preeclampsia had a significantly higher pre-pregnancy body mass index than control subjects (p<0.015). Women with preeclampsia had a higher mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) than control subjects. The mode of delivery was similar between the two groups. The birth weight was significantly lower in the preeclamptic group, but non-significant after adjusting for gestational age at the time of delivery.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

| Preeclampsia (n=20) | Control (n=20) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age (y) | 25.1 ± 7.0 | 25.1 ± 6.7 | NS |

| Race | |||

| African-American | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | NS |

| Hispanic | 19 (95) | 19 (95) | NS |

| Parity | |||

| Nulliparous | 12 (60) | 12 (60) | NS |

| Multiparous | 8 (40) | 8 (40) | NS |

| Pre-Pregnancy BMI | 28.5 ± 5 | 23.9 ± 5 | 0.015 |

| Smoking | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | NS |

| Enrollment GA | 38.6 ± 1.8 | 38.4 ± 1.4 | NS |

| MAP (mm Hg) | |||

| Enrollment | 115 ± 8 | 79 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| 2D PP (n = 14) | 105 ± 9 | 90 ± 9 | <0.001 |

| 1 week PP (n = 15) | 101 ± 12 | 87 ±10 | <0.001 |

| Mode of delivery | |||

| Vaginal | 14 (70) | 13 (65) | NS |

| Cesarean | 6 (30) | 7 (35) | NS |

| Birthweight (g) | 2998 ± 485 | 3543 ± 494 | <0.001* |

Data described as means ± standard deviation or n (percentage)

BMI = body mass index, GA = gestational age, MAP = mean arterial pressure, PP = postpartum

Non-significant when adjusted for gestational age at delivery

Endothelial microparticles and Preeclampsia

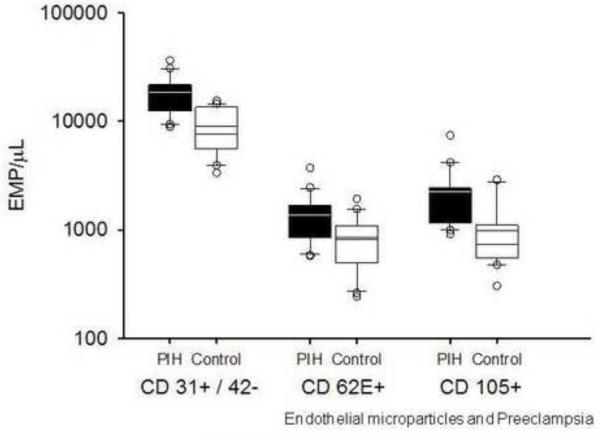

Antepartum Period

The levels of all EMPs measured were elevated in women with preeclampsia (Figure 1). CD 31+/42− EMPs were significantly higher in preeclamptic subjects as compared to control subjects (18552 [12456, 21624] vs. 7606 [5755, 13105] counts/μL, p<0.001). CD62E+ EMPs were increased in women with preeclampsia over control patients (1231 [884, 1661] vs. 739 [452, 1023] counts/μL, p=<0.001). Levels of CD105+ EMPs were also significantly higher in women with preeclamsia (1932 [1210, 2417] vs. 737 [553, 1052] counts/μL, p=0.003).

Figure 1.

EMPs are elevated in preeclampsia.

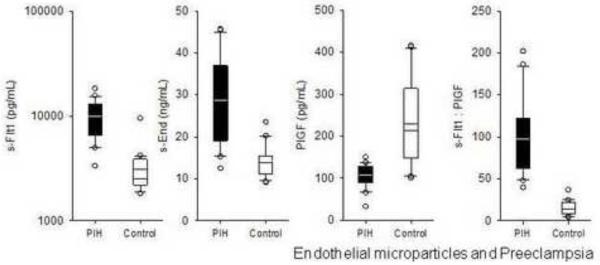

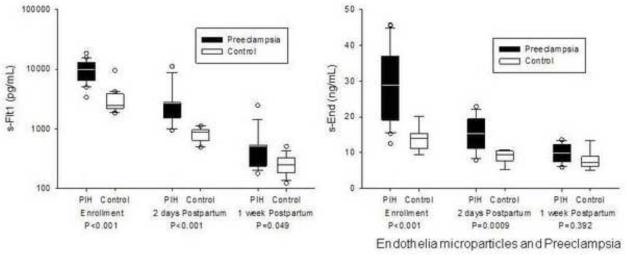

Circulating sFlt1 was significantly elevated in preeclamptic subjects as compared to control subjects (9828 [6612, 12470] vs. 2490 [2209, 3841] pg/mL, p<0.001) (Figure 2). sEnd was also significantly elevated in preeclamptic subjects as compared to control subjects (30 [19, 36] vs. 14 [11, 15] ng/mL, p<0.001). PlGF was significantly lower in women with preeclampsia (108 [90, 127] vs. 213 [149, 315] pg/mL, p=0.006), thereby providing a significantly higher sFlt1:PlGF ratio in this population (88 [65, 116] vs. 14 [10, 22], P<0.001).

Figure 2.

sFlt1, sEnd, and the sFlt1:PlGF ratio are elevated in women with preeclampsia.

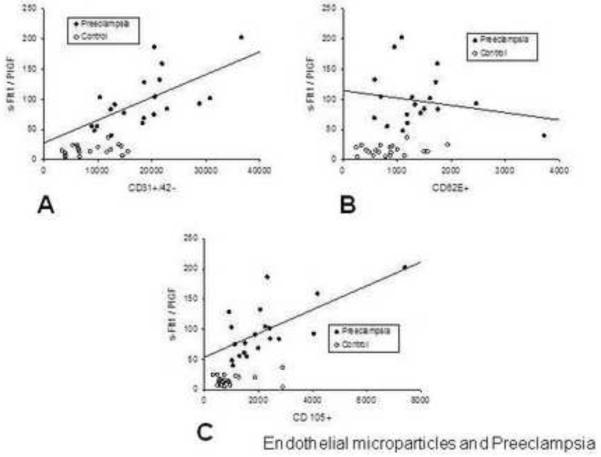

There was no relationship between EMP measurements and the raw concentrations of sFlt1, sEnd or PlGF in the control or preeclamptic cohorts. There was a significantly positive correlation observed between the sFlt1:PlGF ratio and CD31+/42− EMPs (r=0.69, p<0.001) in women with preeclampsia (Figure 3-a). A similarly positive correlation was observed between the sFlt1:PlGF ratio and CD105+ EMPs (r=0.51, p=0.02) (Figure 3-c). There was no relationship between the CD62E+ EMPs and the sFlt1:PlGF ratio (Figure 3-b).

Figure 3.

The sFlt1:PlGF ratio is directly related to the levels of EMPs associated with apoptosis in women with preeclampsia.

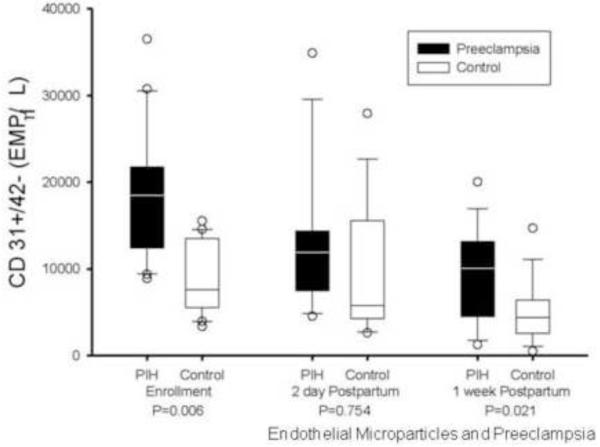

Postpartum Period

While the postpartum levels of CD 31+/41− EMPs declined significantly in both the preeclamptic and control groups, the numbers of CD31+/42− EMPs remained significantly higher 1-week postpartum in women who had preeclampsia as compared to controls (12085 [4483, 13153] vs. 4375 [2671, 6108] counts/μL, P=0.026) (Figure 4). CD62E+ EMPs decreased in both populations in the postpartum period with statistically similar levels at 48 hours and 1 week postpartum. Levels of CD105+ EMPs remained stable during the postpartum period in the control population, while preeclamptic levels showed significant decreases at 48 hours and 1-week postpartum (1044 [807, 1447] and 750 [597, 1264] counts/μL, p=0.031 and 0.017 respectively), approximating control levels by 48 hours.

Figure 4.

The levels of CD 31+/41− EMPs remained significantly higher at 1 week postpartum in women with preeclampsia.

Postpartum levels of sFlt1 and sEnd showed significant decreases both at 48 hours and 1 week after delivery in both preeclamptic and control groups as compared to antepartum levels (Figure 5). At the 48 hour time point, sFlt1 and sEnd was significantly higher in the preeclamptic group than in the control population (1801 [1545, 2733] vs. 888 [665, 947] ng/mL and 16 [11, 19] vs. 10 [8, 10] pg/mL, respectively; p<0.001), but by 1-week postpartum, sFlt1 and sEnd levels were similar between the two groups. There was no correlation identified between EMP levels and sFlt1 or sEnd in the postpartum period.

Figure 5.

sFlt and sEnd decrease in the immediate postpartum period, with similar levels between the preeclamptic and control groups at 1week postpartum.

Comment

The findings of this study support that the anti-angiogenic environment of preeclampsia is related to the degree of endothelial damage occurring at the cellular level. Levine, et al has demonstrated an increase of antiangiogenic proteins, sFlt1 and sEnd, in women destined to develop preeclampsia and hypothesized the interaction of these proteins with PlGF and VEGF leads to an antiangiogenic environment best reflected by the sFlt1:PlGF ratio5,6. This ratio has been shown to correlate with the risk of preterm and term preeclampsia, as well as an increased risk for small-for-gestational-age infants.6 The utilization of the sFlt1:PlGF ratio provides a snapshot of the entire anti-angiogenic imbalance of the maternal vasculature, rather than observing the isolated presence of sFlt1 or sEnd alone, which may not fully represent the insult taking place in the maternal environment as a whole. This study demonstrated increased levels of sFlt1 and sEnd in the preeclamptic population, as well as low PlGF levels in preeclamptics, resulting in an elevated sFlt1:PlGF ratio. Our findings take these observations to the cellular level by demonstrating increased endothelial damage, as measured by an increased release of EMPs. Furthermore we report that while resolution of the antiangiogenic environment begins shortly after birth, recovery from endothelial damage may occur over a longer time frame, as evidenced by a normalization of CD62E+ and CD105+ EMP levels, but a significantly higher level of CD31+/42− EMP in women with preeclampsia compared to control subjects at 1-week postpartum.

The findings of our study support that there is direct endothelial insult occurring in women with preeclampsia. Measurement of EMPs provides a quantifiable measure of endothelial disruption, with EMP research becoming more prevalent in the literature. These liberated endothelial cell antigens are located on varied locations of the endothelial cell and have differing functions. CD31 is found at the endothelial cell junction and is involved in maintaining the integrity of the endothelium and for signaling the adhesion cascade. CD62E is a surface adhesion molecule that is expressed on activated endothelial cells and facilitates recruitment of leukocytes to sights of acute inflammation, CD105, the non-soluble form of endoglin,is found on the vascular endothelium and syncytiotropholasts. It is upregulated on the endothelial cell in response to hypoxia and is associated with the signaling of growth factors. Elevated EMPs have been identified in numerous disease processes with known endothelial damage including multiple sclerosis15, malignant hypertension16, pulmonary hypertension17 and thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura14. Early study by Gonzalez, et al, revealed EMP elevation in CD31+/42-, as well as CD62E+ EMPs in women with preeclampsia and documented a correlation of these levels with the clinical parameters of hypertension and proteinuria. 12 Recent study has also confirmed that higher values of endothelial microparticles were observed in eclamptic patients together with severe preeclamptic patients compared to controls.18 Our study confirms the findings of elevated CD31+/42− and CD 62E+ EMPs in preeclampsia, as well as an additional endothelial-specific marker, CD105+. It was interesting to note that the CD105+ EMP, a marker of endoglin itself, was elevated in preeclampsia, but did not correlate with soluble endoglin levels. Although our study was not designed to investigate the cellular origin of the CD105+ EMP, the lack of relationship between CD105+ EMP and sEnd suggests that this EMP may be derived from the vascular endothelium rather than the syncytiotrophoblast. The clinical implications of the different liberated EMP phenotypes remain uncertain, but the phenotypic expression may provide insight as to the insult occurring at the cellular level. Endothelial cells are noted to release EMPs upon both activation and apoptosis, but the antigenic phenotype of the EMP varies by pathologic process. Jimenez, et al discovered through in vitro study that CD31+/42− and CD105+ EMPs are markedly increased in apoptosis, whereas CD62E+ EMPs are elevated only by activation and not in apoptosis.10 All three phenotypes of EMPs studied were elevated in women with preeclampsia, suggesting a likely combination of both activation and apoptosis occurring at the cellular level. Interestingly, only CD 31+/42− and CD105+ EMPs, those associated with apoptosis, exhibited a positive correlation with the sFlt1:PlGF ratio. This relationship suggests that within the maternal vascular environment, the increased concentration of sFlt1 with the concomitant paucity of PlGF, may be related to an endothelial apoptotic state.

Previous studies have shown that sFlt1 and sEnd are cleared from the maternal circulation within 48 hours after delivery, consistent with the understanding that with delivery of the placenta, the production of sFlt1 and sEnd ceases.19 In patients with preeclampsia, who have significantly higher levels of these proteins in the antepartum state, clearance to non-detectable levels takes longer than that of normal pregnancies.7 The etiology of this delayed clearance is unknown, but undetectable levels are achieved by 1-week postpartum. Despite the restoration of the angiogenic balance in the postpartum period, many of these women have been shown to have increased rates of medical morbidities later in life. Our finding of continued elevation of the CD31+/42− EMPs level at 1-week postpartum lends support to the theory that endothelial damage persists in women with preeclampsia and suggests that endothelial damage may relate to long term sequela.

As with all cellular debris, the mechanism of EMP clearance is likely via the mononuclear phagocyte system, although this has not yet been fully delineated. The rate of EMP clearance from the human circulation has not been investigated to date, but study of labeled platelet microparticles in the rabbit model has documented that microparticles are cleared within 10 minutes from the circulation and do not re-circulate, implying that there must be continuous microparticle production in conditions in which elevated levels of circulating microparticles are detected.20 In this study, EMP levels show an immediate decrease in the postpartum period, similar to the rapid reduction in circulating levels of sFlt1 and sEnd in women with preeclampsia, suggesting that with the clearance of the anti-angiogenic proteins from the maternal circulation endothelial injury abruptly ceases as well. Although a significant correlation between the clearance of EMPs and sFlt1 or sEnd could not be documented, the similar pattern of postpartum clearance is notable. Unlike other EMPs, CD 31+/42− EMPs remain elevated at 1 week postpartum suggesting there is persistent and even possibly ongoing endothelial injury in women with preeclampsia after delivery. This may be clinically significant for prediction of long-term morbidity in a subset of the preeclamptic population or in identification of those women at risk for preeclampsia in future gestations due to persistent endothelial injury. Further study is needed to determine the duration of endothelial insult in the postpartum patient and to determine the implications of ongoing endothelial dysfunction in this population.

The relationship of EMPs and the circulating anti-angiogenic proteins in the antepartum as well as postpartum period in term and preterm preeclampsia is one that warrants further study. Although limited by small sample size, this study provides a rationale for longitudinal studies to investigate the temporal relationship of EMP levels as they relate to sFlt1:PlGF ratio in women destined to develop preeclampsia thus providing insight into the maternal endothelial condition during the pre-clinical disease process.

In summary, levels of CD31+/42−, CD62E+, and CD105+ EMPs are significantly elevated in women with preeclampsia. There is a direct relationship between the levels of CD31+/42− and CD 105+ EMPs and the sFlt1:PlGF ratio in the antepartum preeclamptic state. These EMPs are associated with endothelial apoptosis. Taken together, this data suggests that there is a direct interaction between the anti-angiogenic maternal vascular environment and the degree of endothelial insult, specifically apoptosis, in women with preeclampsia. The potential utility of EMP measurement to further our understanding of the effects of preeclampsia on the endothelium and serve as a biomarker for impending risk of preeclampsia provides wide-ranging avenues for future research.

Condensation.

Endothelial microparticles (EMPs), as markers of endothelial damage, specifically apoptosis, are elevated in preeclampsia and correlate with the sFlt1:PlGF ratio with persistence of EMPs postpartum.

Endothelial microparticles and Preeclampsia

Acknowledgments

Financial support: NIH/NCRR Grant 5 UL1 RR024982-03 Packer (PI)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine, San Francisco, California, February 7-12, 2011

Disclosure: None of the authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Pregnancy: Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;183:S1–S22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidge ST. Oxidative stress and altered endothelial cell function in preeclampsia. Seminars in Reproductive Endocrinology. 1998;16:65–73. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1016254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lockwood CJ, Peters JH. Increased plasma levels of ED1+ cellular fibronectin precede the clinical signs of preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;162:358–62. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90385-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nova A, Sibai BM, Barton JR, Mercer BM, Mitchell MD. Maternal plasma level of endothelin is increased in preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;165:724–727. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90317-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levine RJ, Maynard SE, Qian C, Lim KH, England LJ, Yu KF, Schisterman EF, Thadhani R, Sachs BP, Epstein FH, Sibai BM, Sukhatme VP, Karumanchi SA. Circulating angiogenic factors and the risk of preeclampsia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350:672–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, Yu K, Maynard S, Sachs B, Sibai B, Epstein F, Romero R, Thadhani R, Karumanchi A. Soluble Endoglin and Other Circulating Antiangiogenic Factors in Preeclampsia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:992–1005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powers RW, Roberts JM, Cooper KM, Gallaher MJ, Frank MP, Harger GF, Ness RB. Maternal serum soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 concentrations are not increased in early pregnancy and decrease more slowly postpartum in women who develop preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;193:185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horstman LL, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, Ahn YS. Endothelial microparticles as markers of endothelial dysfunction. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2004;9:1118–35. doi: 10.2741/1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dignat-George F. Measuring circulating cell derived microparticles. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2004;2:1844–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez JJ, Jy W, Mauro LM, Soderland C, Horstman LL, Ahn YS. Endothelial cells release phenotypically and quantitatively distinct microparticles in activation and apoptosis. Thrombosis Research. 2003;109:175–180. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez-Quintero V, Jiménez JJ, Jy W, Mauro LM, Hortman L, O’Sullivan MJ, Ahn Y. Elevated plasma endothelial microparticles in preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;187:450–56. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00469-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Quintero V, Smarkusky LP, Jiménez JJ, Mauro LM, Jy W, Hortsman LL, O’Sullivan MJ, Ahn YS. Elevated plasma endothelial microparticles: preeclampsia versus gestational hypertension. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191(4):1418–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayers L, Kohler M, Harrison P, Sargent I, Dragovic R, et al. Measurement of circulating cell-derived microparticles by flow cytometry: Sources of variability within the assay. Thromobosis Research. 2011;127:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jimenez JJ, Mauro LM, Horstman LL, Ahn YS. Elevated endothelial microparticles in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: finding from brain and renal microvascular cell culture and patients with active disease. British Journal of Hematology. 2001;112:81–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mingar A, Jy w, Jimenez JJ, Sheremata WA, Mauro LM, Mao WW, et al. Elevated plasma endothelial microparticles in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2001;56:1319–24. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preston RA, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, Mauro LM, Horstman LL, Valle M, Aime G, Ahn YS. Effects of severe hypertension on endothelial and platelet microparticles. Hypertension. 2003;41:2111–17. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000049760.15764.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amabile N, Heiss C, Chang V, Angeli FS, Damon L, Rame EJ, McGlothlin D, Grossman W, De Marco T, Yeghiazarians Y. Increased CD62E+ endothelial microparticle levels predict poor outcome in pulmonary hypertension patients. Journal of Heart and Lung Transpantation. 2009;28:1081–86. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reyna-Villasmil E, Mejia-Montilla J, Reyna-Villasmil N, Torres-Cepeda D, Pena-Paredes E, et al. Endothelial microparticles in preeclampsia and ecclampsia. Medicina Clinica. 2011;136(12):522–6. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, Lim KG, Li J, Mondal S, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;111:649–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rand ML, Want H, Bang KWA, Packham MA, Freedman J. Rapid clearance of procoagulant platelet-derived microparticles from the circulation of rabbits. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2006;4:1621–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]