Abstract

The grand vision of manufacturing large-area emissive devices with low-cost roll-to-roll coating methods, akin to how newspapers are produced, appeared with the emergence of the organic light-emitting diode about 20 years ago. Today, small organic light-emitting diode displays are commercially available in smartphones, but the promise of a continuous ambient fabrication has unfortunately not materialized yet, as organic light-emitting diodes invariably depend on the use of one or more time- and energy-consuming process steps under vacuum. Here we report an all-solution-based fabrication of an alternative emissive device, a light-emitting electrochemical cell, using a slot-die roll-coating apparatus. The fabricated flexible sheets exhibit bidirectional and uniform light emission, and feature a fault-tolerant >1-μm-thick active material that is doped in situ during operation. It is notable that the initial preparation of inks, the subsequent coating of the constituent layers and the final device operation all could be executed under ambient air.

Light-emitting electrochromic cells are a promising alternative to organic light-emitting diodes, as their performance is less sensitive to fabrication conditions. Here, a roll-to-roll compatible fabrication of such devices is presented, demonstrating large-area continuous production in ambient conditions.

Light-emitting electrochromic cells are a promising alternative to organic light-emitting diodes, as their performance is less sensitive to fabrication conditions. Here, a roll-to-roll compatible fabrication of such devices is presented, demonstrating large-area continuous production in ambient conditions.

With tantalizing goals such as the projected multi-billion-dollar market for low-cost and environmentally friendly illumination panels in sight1, it comes as no surprise that tremendous efforts have been directed towards the development of high-throughput and cost-effective fabrication methods of qualified lighting technologies. The organic light-emitting diode (OLED) is one such technology2,3,4,5,6,7, and numerous scientific and company reports related to the partial fabrication of OLEDs under ambient air using low-cost printing and coating methods, such as inkjet8,9,10, screen11,12, and gravure13,14, are today available. However, despite these achievements, to our knowledge, no single report on an uninterrupted fabrication of a functional OLED under ambient conditions has appeared to date. This is particularly problematic not only because it makes today's OLEDs prohibitively expensive for many large-scale applications4 but also because the current dependency of OLEDs on, first, an electron-injection layer/cathode with low-work function and concomitant poor ambient stability, and, second, a thin active layer with extremely well-controlled thickness, make the future prospects for such a breakthrough bleak.

An alternative to the OLED is the more process-tolerant light-emitting electrochemical cell (LEC) technology. LECs are characterized by the existence of mobile ions in the active layer, which can redistribute to allow for electrochemical doping following the application of an external voltage. This in-situ electrochemical doping process brings the attractive consequence that the LEC operation is notably insensitive to the above-specified problematic requirements of the OLED, and that LECs thus can be expected to be well suited for the hitherto elusive uninterrupted manufacturing under ambient conditions. Relatively few studies on a potentially scalable fabrication of LECs can be found in the literature, but we note Mauthner et al.'s15 report on inkjet printing of the active material in an open planar device geometry, and recent demonstrations of metal-free16,17 and stretchable LECs18,19.

Here we show that it is possible to fabricate large-area LEC sheets under uninterrupted ambient conditions using a purpose-built roll-coater apparatus. The constituent device layers consist of solely air-stable materials, which are deposited using the slot-die coating technique. The constituent device layers were found to be highly uneven, but the roll-coated LEC devices still exhibited uniform and strong light emission at low applied voltage. The realized LEC sheets are in addition flexible and feature bidirectional light emission as a result of the use of conformable and transparent electrode materials.

Results

Ambient fabrication using a roll-coater apparatus

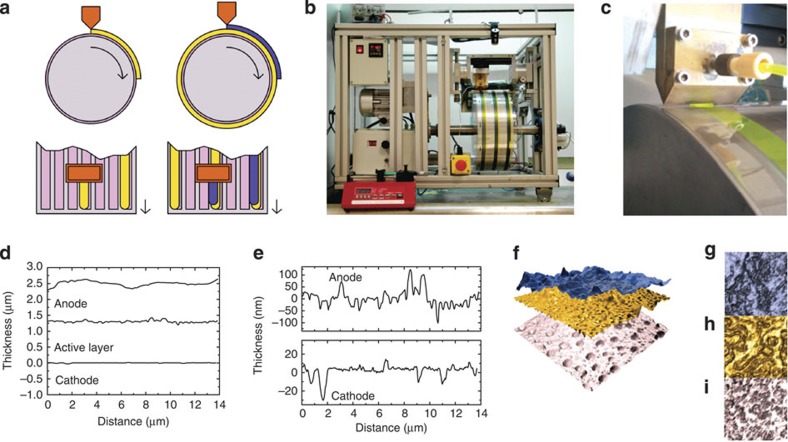

For the fabrication of LEC devices, we used the technique of slot-die coating. Figure 1a depicts schematically the successive deposition of a (yellow) active layer and a (blue) anode on top of a (pink) flexible cathode-coated substrate mounted on a roll. The dissolved material to be coated (the ink) is transferred from an external container via a pump to the (orange) slot-die head, where the coating width is defined by the width of the head's bottom slot through which the ink flows onto the moving substrate, while the coating thickness is dictated by the ink flow rate and the substrate speed. The apparatus shown in Fig. 1b is a new type of slot-die roll coater specifically designed and developed for the challenging task of enabling a time- and material-efficient optimization of a continuous coating process20. The motorized roll can be heated to an elevated temperature of >180 °C and has a diameter of 300 mm, so that a flexible substrate with 1 m length can be mounted and dried directly on the roll. By using a small slot-die head (Fig. 1c), and allowing the head to be translated perpendicular to the coating direction following every complete revolution of the roll, it is possible to coat several stripes on one substrate and enable for an effective substrate length of several metres (Fig. 1b). When the coating system is equipped with the small slot-die head it requires a very small amount of dead volume (<50 μl), which makes the technique well suited for a screening of novel and expensive inks.

Figure 1. Coating process and morphology and thickness of the coated films.

(a) Schematic view of the slot-die roll coating of the (yellow) active layer and the (blue) semitransparent anode on top of a (pink) flexible cathode-coated substrate. The ink is transferred from an external container via a pump to the slot-die head (orange). (b) Photograph of the roll coater during the deposition of the active layer. (c) Close-up photograph of the slot-die head during coating of an active layer stripe. (d) Atomic force microscopy (AFM) data indicating the thickness of the anodic, active and cathodic layers in the LEC device stack. (e) Enlarged AFM data indicating the roughness of the anodic and the cathodic interfaces. (f) Exploded view of 10×10 μm2 AFM height maps of the three constituent layers. (g–i) 2×2 μm2 AFM phase-contrast images of (g) the PEDOT-PSS anode, (h) the active layer and (i) the ZnO cathode.

We prepared a relatively viscous active-material ink, free from binder and thickener additives, comprising a blend of the emissive conjugated polymer superyellow (SY) and the electrolyte KCF3SO3 in poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO). The ink was deposited as multiple stripes (typically three) on a flexible poly(ethylene terephthalate) substrate, precoated with ZnO-on-indium-tin-oxide cathodic stripes21, at a coating speed of 0.6 m min−1; see Fig. 1b,c. A matching number of anode stripes was thereafter coated on top of the active material from a diluted poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) water dispersion at 0.6 m min−1. The ink formulation and coating took place under ambient air, with the roller kept at 40 °C to facilitate the drying of the films. The coated layers had a wet thickness of 100 μm and a dry thickness of 1–1.5 μm (Fig. 1d). The surface morphology map of the dry layers shown in Fig. 1e,f reveals rather uneven interfaces, with an root mean squared surface roughness for the cathodic and anodic interfaces of 4.5 and 20 nm, respectively. Figure 1g–i presents 2×2 μm2 phase-contrast maps of the constituent layers, and we note that the active material (Fig. 1h) displays a relatively minor phase separation on the order of a few hundred nanometres between the hydrophobic conjugated polymer and the hydrophilic electrolyte, which is of the same order of magnitude as for spin-coated LEC films with similar composition22,23,24.

Performance of the roll-coated devices

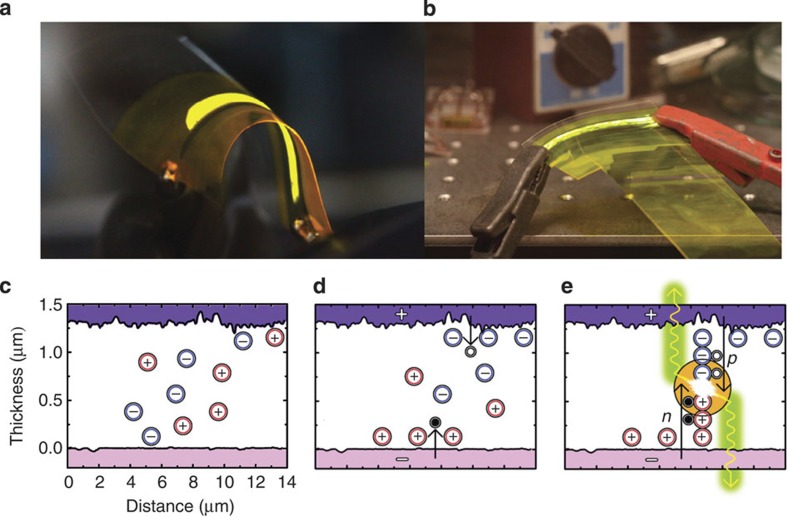

Figure 2a,b shows the light emission from two roll-coated devices when driven with an applied voltage of V=7 V. The emitting area is ~300 mm2, and we call attention to the bidirectionality and the uniformity of the light emission. The former is a consequence of both the anode and the cathode being transparent, whereas the latter is a direct manifestation of the unique operational mechanism of LECs. In fact, an OLED comprising a similar thick and uneven layer for the active material (Fig. 1e,f) would emit with a much lower and non-uniform light intensity, if any. Moreover, as mentioned previously, the current generation of OLEDs depends on the existence of a highly air-sensitive (low-work function) material for the attainment of efficient electron injection, which on generic terms excludes a continuous fabrication process under ambient conditions.

Figure 2. Key aspects of LEC operation.

(a) Photograph of a slot-die–coated LEC, illustrating the bidirectional light emission and the device conformability. (b) Light emission from a semitransparent slot-die–coated LEC following >6 months storage in a glove box. The devices depicted in a and b were driven at V=7 V. (c) Schematic structure of a pristine LEC device, indicating the existence of mobile (red) cations and (blue) anions in the active layer and the rough (blue) anodic and (purple) cathodic interfaces. (d) The electric double-layer formation and the initial electron (solid circles) and hole (open circles) injection within the same device following the application of a voltage bias. (e) The light emission (yellow-green) from the in-situ formed p–n junction at steady state.

So what is the key distinguishing feature between an LEC and an OLED that makes the former so much more fit for a low-cost continuous coating process in ambient conditions? The answer is the existence of mobile ions within the active layer (Fig. 2c)25. These ions redistribute following the application of a voltage to establish nanometre-thin electric double layers at the cathodic and anodic interfaces that allow for balanced and efficient electron and hole injection, respectively (Fig. 2d). The initial injected electrons and holes attract electrostatically compensating counter-ions in an electrochemical doping process—n-type at the cathode and p-type at the anode—and these two doping regions grow with time, eventually making contact in the bulk to form a p–n junction structure (Fig. 2e)26,27. Such an in-situ formation of a p–n junction is particularly attractive in the context of thick and uneven layers of active material that commonly result from a coating or printing process, as the p–n junction will form independent on the thickness of the active layer. In other words, the doped regions continue to grow until they make contact, at which point the limiting thickness of the device is the small and constant thickness of the p–n junction and not the large and spatially varying thickness of the active material.

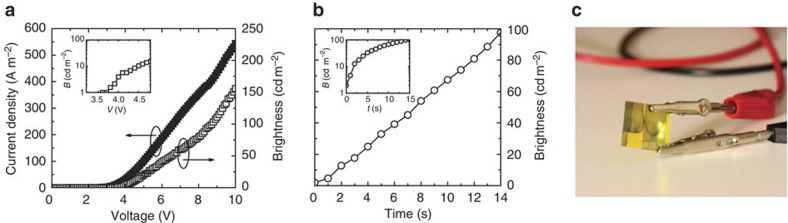

The measured performance of the roll-coated LEC devices is quite promising, considering that these are the pioneering experiments in the field. Figure 3a shows optoelectronic data recorded during a voltage sweep at 0.1 V s−1, during which the brightness reaches B=150 cd m−2 at V=10 V. The turn-on voltage at which the device begins to emit visible light (B>1 cd m−2) is V=3.7 V (see inset in Fig. 3a), which is close to the theoretical limit, as dictated by the band-gap potential of SY; VBG (SY)=2.4 V (refs 28, 29). The turn-on time is a critical and important parameter for LEC devices. Figure 3b presents the brightness versus time for a device driven at constant current density (j). We define the turn-on time as the time to reach B>10 cd m−2 for a pristine device, and find that the turn-on time is ~2 s at j=770 A m−2 (see inset in Fig. 3b). The operational stability of roll-coated LECs can be quantified by the time to reach half-maximum brightness22,30, which we find to be ~8 h at a drive current density of j=77 A m−2. The latter results were attained on devices that had been stored in a glove box for >6 months. The highest recorded current efficacy is 0.6 cd A−1 at a brightness of B=50 cd m−2. Finally, the fabrication yield of the roll-coated LECs is found to be very satisfying, primarily due to the fault-tolerant device geometry with a thick active layer and air-stable materials, and barring mistakes during transportation and contacting, all tested devices were functional and emitting light.

Figure 3. Performance of roll-coated devices.

(a) Optoelectronic data recorded on a roll-coated poly(ethylene terephthalate)/indium-tin-oxide/ZnO/{SY+PEO+KCF3SO3}/PEDOT:PSS device during a voltage sweep at 0.1 V s−1. Inset: the brightness data plotted on a logarithmic scale. (b) The turn-on time for a nominally identical device driven in galvanostatic mode at j=770 A m−2. Inset: the brightness data plotted on a logarithmic scale. (c) Photograph of an encapsulated roll-coated device operating at V=7 V under ambient conditions. Note that the device had been stored under ambient air for 3 days before the voltage was applied.

Discussion

In the above performance context, we mention that the herein used active material was chosen and optimized for the purpose of facile coating, but that, for example, its high electrolyte content has proven to be detrimental for the attainment of high efficiency and long-term stability31. We therefore foresee that the reported performance values can be significantly improved with further optimization of the constituent processes and the utilization of lower-electrolyte-content active materials, so that state-of-the art efficiency and operational stability values for polymer LECs of ~10 cd A−1 and several 1,000 h, respectively, can be attained also for roll-coated LEC devices32,33,34,35.

The ink formulation and coating processes, as presented herein, were conveniently executed solely under ambient conditions, but during light emission the active material in LECs (and in OLEDs) must be free from oxygen and water vapour to enable a satisfying performance. This challenge should, however, be addressable in a manner compatible with ambient processing by including an efficient drying stage at an elevated temperature to drive out remnants of O2/H2O/solvents followed by an immediately subsequent encapsulation stage, where a flexible barrier material is attached to the device with, for example, a simple pressure-sensitive adhesive. Figure 3c shows a photograph of such an encapsulated roll-coated LEC device during operation at V=7 V under ambient conditions. This device could be operated without any signs of deterioration in performance following 3 days of ambient storage, despite the fact that the encapsulation material exhibits rather limited barrier properties (see ref. 36). Considering the current prohibitive significant cost for high-performance barrier materials37, this opportunity to utilize a material-conservative and time-efficient fabrication process and a low-cost barrier material could thus indicate a viable path towards conformable emissive devices for low-end applications, at a cost that could be accepted by the market.

To conclude, we demonstrate that the entire manufacturing of emissive LEC sheets—from the initial preparation of inks, to the coating of the constituent layers, to the final encapsulation—can be carried out in air using a slot-die coating technique that is directly compatible with high-speed and low-cost roll-to-roll fabrication. The fabricated devices are attractively robust and fault-tolerant due to the utilization of air-stable materials and a micrometre-thick emissive layer. Furthermore, the introduced roll-coating apparatus is particularly fit for further optimization of the constituent processes and the device performance. We anticipate that transparent and metal-free plastic applications with good light-emission performance should be a highly realistic option with the use of other available material combinations, and hope that our effort will pave the way so that long-term grand visions within the illumination community, notably an affordable 'light-emitting wall-paper', finally will turn into reality.

Methods

Materials and ink preparation

The dry materials, SY (Merck, catalogue no. PDY-132), PEO (Mw=5×106 g mol−1, Sigma-Aldrich), and KCF3SO3 (Sigma-Aldrich), were separately dissolved in cyclohexanone in a 10 g l−1 concentration. These master solutions were stirred for 24 h at 70 °C, before being blended in a (SY:PEO:KCF3SO3) volume ratio of (1:1.35:0.25) to form the active-material ink. The ink was stored in 20-ml glass vials with Al lined screw caps for >5 days before deposition. The anode ink was a PEDOT:PSS dispersion (Orgacon 5015, Agfa) diluted with 75 volume % isopropanol. All ink formulation was done under ambient air.

Device fabrication

The LEC devices were manufactured on a slot-die roll coater developed at Risø DTU (Fig. 1b)20. A flexible poly(ethylene terephthalate) substrate (length=1 m, width=0.15 m) was roll-coated with a 14-nm-thick ZnO nanoparticle layer on indium-tin oxide (60 Ω/ ) in a line pattern (line width=4 mm, line separation=1 mm)38 and attached to the roller using pressure adhesive tape. The active-layer ink was deposited onto the ZnO cathode with an ink-flow rate of 4.0 ml min−1 at a substrate speed of 0.6 m min−1 using a 13- or 50-mm-wide slot-die head. Following a 5-min intermission, the anode ink was deposited on top of the active layer at 1.0 ml min−1 and 0.6 m min−1 using a 13-mm-wide slot-die head. The entire coating process was executed at 40 °C under ambient air. The LEC devices were additionally dried at 100 °C for 12 h under N2 and thereafter stored under ambient air for >5 days before testing. Some devices were encapsulated on both sides with a 55-μm-thick barrier foil (U-barrier, Amcor Flexibles) to allow for light emission under ambient conditions, whereas non-encapsulated devices were tested in a N2-filled glove box ([O2], [H2O] <10 p.p.m.).

) in a line pattern (line width=4 mm, line separation=1 mm)38 and attached to the roller using pressure adhesive tape. The active-layer ink was deposited onto the ZnO cathode with an ink-flow rate of 4.0 ml min−1 at a substrate speed of 0.6 m min−1 using a 13- or 50-mm-wide slot-die head. Following a 5-min intermission, the anode ink was deposited on top of the active layer at 1.0 ml min−1 and 0.6 m min−1 using a 13-mm-wide slot-die head. The entire coating process was executed at 40 °C under ambient air. The LEC devices were additionally dried at 100 °C for 12 h under N2 and thereafter stored under ambient air for >5 days before testing. Some devices were encapsulated on both sides with a 55-μm-thick barrier foil (U-barrier, Amcor Flexibles) to allow for light emission under ambient conditions, whereas non-encapsulated devices were tested in a N2-filled glove box ([O2], [H2O] <10 p.p.m.).

Device characterization

The roll-coated LEC sheets were characterized using a computer controlled source-measure unit (Agilent U2722A) and a calibrated photodiode equipped with an eye-response filter (Hamamatsu Photonics) connected to a data acquisition card (National Instruments USB-6009) via a current-to-voltage amplifier. The AFM data were recorded in tapping mode under ambient conditions using a MultiMode SPM (Veeco) and the recorded micrographs were visualized using the software Gwyddion. The photographs were recorded with a digital camera (Canon EOS 300D) using the following settings: shutter speed=1/8 s, aperture=f/5.6, sensor sensitivity=ISO-3200.

Author contributions

A.S., H.F.D. and F.C.K. carried out the experiments. L.E. and A.S. wrote the manuscript. A.S., H.F.D., F.C.K. and L.E. contributed to data analysis and project planning.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Sandström, A. et al. Ambient fabrication of flexible and large-area organic light-emitting devices using slot-die coating. Nat. Commun. 3:1002 doi: 10.1038/2002 (2012).

Acknowledgments

L.E. and A.S. are grateful to Kempestiftelserna, Energimyndigheten and the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet) for financial support. L.E. is a Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Research Fellow supported by a grant from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. F.C.K. and H.F.D. are thankful for support from the Danish Strategic Research Council (2104-07-0022).

References

- Sheats J. R. Manufacturing and commercialization issues in organic electronics. J. Mater. Res. 19, 1974–1989 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Tang C. W. & Van Slyke S. A. Organic electroluminescent diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 51, 913–915 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Burroughes J. H. et al. Light-emitting-diodes based on conjugated polymers. Nature 347, 539–541 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Mertens R. The OLED Handbook 1st edn (Metalgrass software, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. R. et al. Management of singlet and triplet excitons for efficient white organic light-emitting devices. Nature 440, 908–912 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reineke S. et al. White organic light-emitting diodes with fluorescent tube efficiency. Nature 459, 234–238 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So F., Kido J. & Burrows P. Organic light-emitting devices for solid-state lighting. MRS Bull. 33, 663–669 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Hebner T. R., Wu C. C., Marcy D., Lu M. H. & Sturm J. C. Ink-jet printing of doped polymers for organic light emitting devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 72, 519–521 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Chang S.- C. et al. Multicolor organic light-emitting diodes processed by hybrid inkjet printing. Adv. Mater. 11, 734–737 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M. et al. A 5.8-in. phosphorescent color AMOLED display fabricated by ink-jet printing on plastic substrate. J. Soc. Inf. Disp. 17, 1037–1042 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Pardo D. A., Jabbour G. E. & Peyghambarian N. Application of screen printing in the fabrication of organic light-emitting devices. Adv. Mater. 12, 1249–1252 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Birnstock J. et al. Screen-printed passive matrix displays based on light-emitting polymers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 3905–3907 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Chung D.- Y., Huang J., Bradley D. D. C. & Campbell A. J. High performance, flexible polymer light-emitting diodes (PLEDs) with gravure contact printed hole injection and light emitting layers. Organic Electronics 11, 1088–1095 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Nakjima H. et al. Flexible OLEDs poster with gravure printing method. SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers 36, 1196–1199 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Mauthner G. et al. Inkjet printed surface cell light-emitting devices from a water-based polymer dispersion. Organic Electronics 9, 164–170 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Matyba P. et al. Flexible and metal-free light-emitting electrochemical cells based on graphene and PEDOT-PSS as the electrode materials. ACS Nano 5, 574–580 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z. B. et al. Fully bendable polymer light emitting devices with carbon nanotubes as cathode and anode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 203304 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z. B., Niu X. F., Liu Z. T. & Pei Q. B. Intrinsically stretchable polymer light-emitting devices using carbon nanotube-polymer composite electrodes. Adv. Mater. 23, 3989–3994 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiatrault H. L., Porteous G. C., Carmichael R. S., Davidson G. J. E. & Carmichael T. B. Elastomeric emissive materials: stretchable light-emitting electrochemical cells using an elastomeric emissive material. Adv. Mater. 24, 2673–2678 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dam H. F. & Krebs F. C. Simple roll coater with variable coating and temperature control for printed polymer solar cells. Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. C. 97, 191–196 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Krebs F. C., Fyenbo J. & Jorgensen M. Product integration of compact roll-to-roll processed polymer solar cell modules: methods and manufacture using flexographic printing, slot-die coating and rotary screen printing. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 8994–9001 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Yu G., Heeger A. J. & Yang C. Y. Efficient, fast response light-emitting electrochemical cells: electroluminescent and solid electrolyte polymers with interpenetrating network morphology. Appl. Phys. Lett. 68 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Wenzl F. P. et al. The influence of the phase morphology on the optoelectronic properties of light-emitting electrochemical cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 14, 441–450 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Matyba P., Andersson M R. & Edman L. On the desired properties of a conjugated polymer-electrolyte blend in a light-emitting electrochemical cell. Organic Electronics 9, 699–710 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Pei Q. B., Yu G., Zhang C., Yang Y. & Heeger A. J. Polymer light-emitting electrochemical-cells. Science 269, 1086–1088 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matyba P. et al. The dynamic organic p-n junction. Nat. Mater. 8, 672–676 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenes M. et al. Operating modes of sandwiched light-emitting electrochemical cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 1581–1586 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom A., Matyba P. & Edman L. Yellow-green light-emitting electrochemical cells with long lifetime and high efficiency. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 053303 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Becker H. et al. Soluble PPVs with enhanced performance—a mechanistic approach. Adv. Mater. 12, 42–48 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Costa R. D. et al. Intramolecular π-stacking in a phenylpyrazole-based iridium complex and its use in light-emitting electrochemical cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5978–5980 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J., Matyba P. & Edman L. The design and realization of flexible, long-lived light-emitting electrochemical cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 2671–2676 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Tang S. & Edman L. Quest for an appropriate electrolyte for high-performance light-emitting electrochemical cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 2727–2732 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z. et al. Stabilizing the dynamic pin junction in polymer light-emitting electrochemical cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 367–372 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. & Pei Q. B. Efficient blue-green and white light-emitting electrochemical cells based on poly 9,9-bis(3,6-dioxaheptyl)-fluorene-2,7-diyl. J. Appl. Phys. 81, 3294–3298 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y., Bazan G. C. & Heeger A. J. Long-lifetime polymer light-emitting electrochemical cells. Adv. Mater. 19, 365–370 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Krebs F. C. et al. A round robin study of flexible large-area roll-to-roll processed polymer solar cell modules. Sol. Energ. Mater. Sol. C. 93, 1968–1977 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Park J. S., Chae H., Chung H. K. & Lee S. I. Thin film encapsulation for flexible AM-OLED: a review. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 26, 034001 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Krebs F. C., Tromholt T. & Jorgensen M. Upscaling of polymer solar cell fabrication using full roll-to-roll processing. Nanoscale 2, 873–886 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]