Abstract

Objective

To quantify the antiemetic efficacy and adverse effects of cannabis used for sickness induced by chemotherapy.

Design

Systematic review.

Data sources

Systematic search (Medline, Embase, Cochrane library, bibliographies), any language, to August 2000.

Studies

30 randomised comparisons of cannabis with placebo or antiemetics from which dichotomous data on efficacy and harm were available (1366 patients). Oral nabilone, oral dronabinol (tetrahydrocannabinol), and intramuscular levonantradol were tested. No cannabis was smoked. Follow up lasted 24 hours.

Results

Cannabinoids were more effective antiemetics than prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, chlorpromazine, thiethylperazine, haloperidol, domperidone, or alizapride: relative risk 1.38 (95% confidence interval 1.18 to 1.62), number needed to treat 6 for complete control of nausea; 1.28 (1.08 to 1.51), NNT 8 for complete control of vomiting. Cannabinoids were not more effective in patients receiving very low or very high emetogenic chemotherapy. In crossover trials, patients preferred cannabinoids for future chemotherapy cycles: 2.39 (2.05 to 2.78), NNT 3. Some potentially beneficial side effects occurred more often with cannabinoids: “high” 10.6 (6.86 to 16.5), NNT 3; sedation or drowsiness 1.66 (1.46 to 1.89), NNT 5; euphoria 12.5 (3.00 to 52.1), NNT 7. Harmful side effects also occurred more often with cannabinoids: dizziness 2.97 (2.31 to 3.83), NNT 3; dysphoria or depression 8.06 (3.38 to 19.2), NNT 8; hallucinations 6.10 (2.41 to 15.4), NNT 17; paranoia 8.58 (6.38 to 11.5), NNT 20; and arterial hypotension 2.23 (1.75 to 2.83), NNT 7. Patients given cannabinoids were more likely to withdraw due to side effects 4.67 (3.07 to 7.09), NNT 11.

Conclusions

In selected patients, the cannabinoids tested in these trials may be useful as mood enhancing adjuvants for controlling chemotherapy related sickness. Potentially serious adverse effects, even when taken short term orally or intramuscularly, are likely to limit their widespread use.

What is already known on this topic

Requests have been made for legalisation of cannabis (marijuana) for medical use

Long term smoking of cannabis can have physical and neuropsychiatric adverse effects

Cannabis may be useful in the control of chemotherapy related sickness

What this study adds

Oral nabilone and dronabinol and intramuscular levonantradol are superior to conventional antiemetics (such as prochlorperazine or metoclopramide) in chemotherapy

Side effects are common with cannabinoids, and although some may be potentially beneficial (euphoria, “high,” sedation), others are harmful (dysphoria, depression, hallucinations)

Many patients have a strong preference for cannabinoids

Introduction

Sections of the medical establishment have pleaded for legalisation of cannabis (marijuana) for medical use.1,2 Interest in cannabis and its active constituents, cannabinoids, as therapeutic agents has increased recently.3 Dronabinol (Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, one of the main ingredients in cannabis) and the synthetic cannabinoid compound nabilone are available by prescription in some countries.

A Medline search using the terms cannabis, cannabinoids, marijuana, and marijuana smoking found 6059 articles from 1975 to 1996; most were on the antiemetic properties of cannabis.4 Surveys of oncologists' choices of treatment for emesis caused by chemotherapy came to divergent results.4 In one, 63% of responding oncologists agreed with the statement affirming the efficacy of cannabis for treatment of emesis.5 In another, oncologists ranked dronabinol or smoked cannabis only ninth out of nine choices for mild nausea, and sixth out of nine for severe nausea.6 An early literature review on cannabinoids and emesis concluded that orally administered dronabinol represented a major advance in antiemetic therapy.7

We searched systematically for the strongest evidence of efficacy and harm of cannabis in patients having chemotherapy. We examined whether there is any evidence that cannabis is antiemetic when given concomitantly with emetogenic chemotherapy, how well cannabis works in this setting compared with placebo or conventional antiemetics, the evidence for a dose-response relation, and the profile of adverse effects.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched systematically for randomised controlled comparisons of the antiemetic efficacy of cannabis (experimental intervention) with any antiemetic or placebo (control) in chemotherapy. Two authors (DC and MRT) searched independently, using different search strategies, in Medline and Embase (last search, 10 August 2000). Free text key words used were cannabinoids, cannabis, nabilone, tetrahydrocannabinol, THC, marihuana, marijuana, levonantradol, dronabinol, randomised, randomized, and human. We also searched the Cochrane Library (issue 3, 2000). Reference lists of retrieved reports and review articles were checked. The search included data in any language. Only full publications in peer reviewed journals were considered. Data from abstracts, letters, and reports from other clinical settings (radiotherapy and postoperative nausea and vomiting) were not considered. We did not contact authors or manufacturers.

Critical appraisal

All retrieved reports were checked for inclusion criteria by one author (MRT). Those definitely not relevant were excluded at this stage. All potentially relevant reports were then read by all authors independently to assess adequacy of randomisation and blinding and description of withdrawals according to the validated three item, five point Oxford score.8 The maximum score of an included randomised controlled trial was five and the minimum was one. Authors met to reach a consensus.

Data extraction

From relevant reports we obtained information on patients, dose of cannabis and control treatments, chemotherapy regimens, and relevant end points. The end point of primary interest was antiemetic efficacy. Different end points for antiemetic efficacy were reported. A “major response,” for instance, could be “no more than two vomiting episodes” in one trial. A “partial response” could be defined as “a reduction of 50% or more in the duration or severity of nausea, and in the number of vomiting episodes, compared with previous courses of identical chemotherapy” in another trial. Because of this inconsistency in definitions we extracted only dichotomous data that came closest to complete control (that is, absence) of nausea or vomiting in the first 24 hours of chemotherapy. Some studies reported incidence of nausea or vomiting per “treatment episode” or per “treatment cycle” rather than per patient. These data were not further analysed. The end point of secondary interest was the number of patients who, after completion of the trial, expressed preference for cannabis or control for future chemotherapy cycles. Data on adverse effects were extracted when reported in dichotomous form.

Quantitative analysis

As an estimate of the significance of a difference between cannabis and control treatments we calculated relative risks with 95% confidence intervals.9 For combined data, a fixed effect model was used because heterogeneity tests lack sensitivity and because we pooled data only when they were clinically homogeneous.10 Clinical relevance of treatment effect was expressed as numbers needed to treat and 95% confidence intervals.11 When the 95% confidence interval of the relative risk excluded 1, the 95% confidence interval for the number needed to treat ranged from a positive limit to a negative limit, indicating that the confidence interval includes infinity.12

We looked for a dose-response relation in data from clinically homogeneous subgroups. Such subgroups had to report comparisons of different doses of one cannabinoid (for instance, nabilone) with one comparator (for instance, placebo), have a similar underlying emetogenic risk (for instance, highly emetogenic chemotherapy with cisplatin), and have a well defined end point (for instance, complete control of vomiting).

Results

Included and excluded trials

We screened 198 reports; 51 were potentially relevant randomised controlled trials. Twenty one were subsequently excluded. Seven were not primarily studies of cannabinoids or had no relevant information.13–19 Four were in other clinical settings (radiotherapy,20,21 surgery,22 or AIDS23). Five randomised trials (four reports) were excluded because they reported emesis data per chemotherapy cycle only and no other relevant data could be extracted,24 the data could not be analysed,25 the study design was unclear,26 or the study used only physiological measurements.27 Finally, five reports (or parts of them28) were duplicates—that is, they contained data that had previously been published as full reports.29–32

We analysed data from 30 randomised controlled trials published between 1975 and 1997 (table 1). In the 30 trials, 1760 patients were randomised, but subsequently 394 (22%) were excluded by the original trialists. Thus, efficacy data from 1366 patients could be analysed. The average trial size was 46 patients (range 8 to 139). The median quality score was 4 (range 1 to 4); 17 scored 4, eight 3, two 2, and three 1. The method of blinding was adequate in 21 (70%) trials—for example, identical tablets. Twenty five trials (83%) used a crossover design. Since the results from crossover trials were usually reported as if they had come from a parallel group trial we used the data accordingly. The median number of chemotherapy cycles was two (range one to six). Two trials were in children,34,39 and one in both children and adults.58 All other trials were in adults only. Various tumours were treated. Chemotherapy was with a variety of cytotoxic regimens with different emetogenic potencies (table 1). Five trials reported on the number of patients with a history of cannabis use.35,36,58–60 In nine trials, all patients were reported not to have used cannabis previously.33,34,39,41–43,46,49,51 In the other 16 trials, it was unclear whether patients had used cannabis previously.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in systematic review of cannabinoids for chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting

| Setting | Chemotherapy | Active v control (No of patients)* | Oxford score (random/blinding/ drop outs)8 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults, small cell bronchial carcinoma33 | Doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, vincristine, etoposide | Nabilone 2 mg×2 (27) v prochlorperazine 10 mg×3 (30) | 1/2/1 |

| Children, age 3.5 to 17.8 years, various paediatric malignancies34 | Doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, fluorouracil, methotrexate, vincristine, etoposide | Nabilone 1-4 mg (30) v prochlorperazine 5-20 mg (30) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults, osteogenic sarcoma35 | High dose methotrexate | Dronabinol 10 mg/m2×4 (15) v placebo (15) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults, various tumours36 | Doxorubicin, cytoxane | Dronabinol 10 mg/m2×4 (8) v placebo (8) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults, solid tumours37 | Cyclophosphamide, mustine | Dronabinol 12 mg/m2×2 (35) v metoclopramide 4.5 mg/m2×1 intravenous (35) v thiethylperazine 6.6 mg/m2×3 (35) | 1/2/0 |

| Adults, adenocarcinoma of the ovary, germ cell tumours38 | Doxorubicin, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, vincristine | Nabilone 1 mg×5 (37) v metoclopramide 1 mg/kg×5 intravenous (39) | 1/2/0 |

| Children <17 years, various tumours39 | Cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine | Nabilone 1-3 mg (18) v domperidone 15-45 mg (18) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults, 15 to 74 years, various tumours40 | Bleomycin, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine | Nabilone 2 mg×4 (80) v prochlorperazine 10 mg×4 (80) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults, 17 to 69 years, various tumours29 | Bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine | Nabilone 2 mg×2 (50) v placebo (50) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults, median age 61 years, gastrointestinal tumours41 | Doxorubicin, fluorouracil, vincristine | Dronabinol 15 mg×2 (38) v prochlorperazine 10 mg×2 (41) v placebo (37) | 1/2/1 |

| Women, various gynaecological tumours42 | Doxorubicin, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide | Nabilone 1 mg×3 (18) v chlorpromazine 12.5 mg×1-2 intramuscular (18) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults 39 to 73 years, various tumours43 | High dose cisplatin | Dronabinol 10 mg/m2×5 (15) v metoclopramide 10 mg/kg×5 intravenous (15) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults, median age 33 (range 15 to 74) years, various tumours44 | Bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, vincristine | Nabilone 2 mg×3-4 (113) v prochlorperazine 10 mg×3-4 (113) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults, mean age 50 (range 17 to 80) years, various tumours45 | Cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, fluorouracil, vincristine | Levonantradol 0.5 mg×3 intramuscular (27) v levonantradol 0.75 mg×3 intramuscular (28) v levonantradol 1.0 mg×3 intramuscular (26) v chlorpromazine 25 mg×3 intramuscular (27) | 1/0/0 |

| Adults aged 18 to 70 years, various tumours46 | Doxorubicin, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine | Nabilone 2 mg×2 (18) v prochlorperazine 10 mg×2 (18) | 1/0/1 |

| Adults aged 20 to 58 years, various tumours47 | Doxorubicin, cisplatin | Nabilone 2 mg×2 (24) v placebo (24) | 1/1/1 |

| Adults, Hodgkin's or non-Hodgkin's lymphoma48 | Vincristine, chlormethine | Dronabinol 10 mg/m2×2 (11) v placebo (11) | 1/2/0 |

| Adults aged 20 to 68 years, various tumours49 | Cisplatin (not high dose) | Dronabinol 10 mg×4 (17) v prochlorperazine 10 mg×4(20) v dronabinol 10 mg×4 plus prochlorperazine 10 mg×4(17) | 1/1/1 |

| Adults, 50th centile = 57 years, various tumours50 | Doxorubicin, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, fluorouracil, methotrexate, vincristine | Nabilone 2 mg×2 (36) v placebo (36) | 1/1/0 |

| Adults aged 18 to 69 years, various tumours, history of emesis due to chemotherapy51 | Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, fluorouracil, vincristine | Dronabinol 15 mg/m2×6 (36) v prochlorperazine 10 mg×6 (36) | 1/0/0 |

| Adults, mean age 41-45 years, various tumours52 | Cisplatin, doxorubicin | Dronabinol 10 mg×4 (average) (37) v haloperidol 2 mg×5 (average) (36) | 1/2/0 |

| Adults aged 19 to 45 years, testicular cancer53 | Doxorubicin, cisplatin | Nabilone 2 mg×2 (20) v alizapride 150 mg×3 (20) | 1/0/0 |

| Adults aged 48 to 78 years, lung cancer54 | Doxorubicin, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine | Nabilone 1 mg×2 (24) v prochlorperazine 7.5 mg×2 (24) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults aged 22 to 71 years, various tumours55 | Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, fluorouracil | Dronabinol 7 mg/m2×4 (55) v prochlorperazine 7 mg/m2×4 (55) v placebo (55) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults aged 21 to 66 years, various tumours56 | Doxorubicin, cisplatin | Nabilone 1 mg×3 (19) v domperidone 20 mg×3 (19) | 1/1/1 |

| Adults aged 18 to 76 years, various tumours57 | No data | Dronabinol 15 mg or 10 mg/m2×3 (20) v placebo (20) | 1/2/1 |

| Children and adults, aged 9 to 70 years, various tumours58 | Cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate | Dronabinol 15 mg or 10 mg/m2×3 (73) v prochlorperazine 10 mg×3 (73) | 1/2/1 |

| Adults aged 19 to 65 years, various tumours59 | Cisplatin | Nabilone 2 mg×2 (37) v prochlorperazine sr 10 mg×2 (37) | 1/1/1 |

| Adults aged 18 to 82 years, various tumours60 | Various | Dronabinol 7.5 to 12.5 mg×3 (172) v prochlorperazine 10 mg×3 (181) | 2/1/1 |

| Adults aged 18 to 81 years, various tumours61 | Doxorubicin, cisplatin | Nabilone 2 mg×2 (84) v placebo (84) | 1/2/1 |

Drugs taken orally unless stated otherwise.

Three different cannabinoids were tested. Oral nabilone was tested in 16 trials, oral dronabinol in 13, and intramuscular levonantradol in one. Nabilone doses ranged from 1 mg per 24 hours in children34 to 8 mg per 24 hours in adults40; the commonest dose was 4 mg per 24 hours. Dronabinol regimens were most often given according to body surface area in m2. Doses ranged from 10 mg/m2 twice daily48 to 15 mg/m2 six times a day.51 Inhaled cannabis was not tested in these trials; however, in one trial comparing dronabinol with placebo, cannabis cigarettes were used as a rescue treatment in the event of a vomiting episode.35

Commonest controls were prochlorperazine (12 trials), and placebo (10 trials). Other comparators were metoclopramide (four), chlorpromazine (two), thiethylperazine (one), haloperidol (one), domperidone (two), and alizapride (one).

Antiemetic efficacy

In 14 trials, the observation period was clearly defined as 24 hours. In the other trials, chemotherapy cycles may have lasted longer, but it was unclear how long observations continued for antiemetic efficacy. We had to assume for all these trials that they reported antiemetic efficacy per patient within 24 hours—that is, acute antiemetic efficacy. In one trial, additional efficacy data were clearly defined for days 2 to 4—that is, delayed antiemetic efficacy. This was not considered for combined analyses. Twelve trials reported antiemetic efficacy with various scoring systems, but we could not extract dichotomous data on the number of patients who were completely free of nausea or vomiting.28,37–40,42,43,47,48,50,56,57

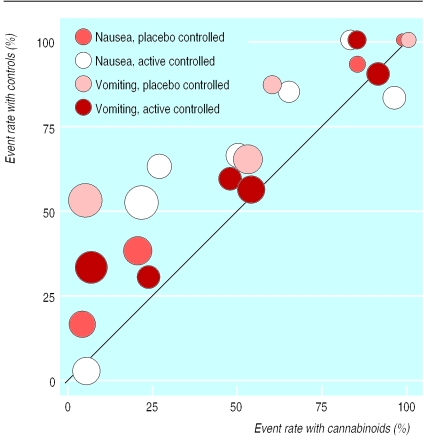

The 10 trials that reported dichotomous data on nausea or vomiting showed a wide variability in event rates with both cannabinoids and controls (fig 1); the event rate scatter suggested increased efficacy with cannabinoids and relative homogeneity of the data.33–36,41,46,53–55

Figure 1.

Incidences of nausea and vomiting with cannabinoids and control treatments. Each symbol represents one trial. Data are from 10 trials that reported separate dichotomous data on nausea or vomiting. Two trials had two comparators (active and placebo) and nine trials had data on both nausea and vomiting. Symbol sizes are proportional to trial sizes. The solid line represents equality

Complete control of nausea or vomiting

Across all trials, cannabinoids were more effective than active comparators and placebo (table 2). Six to eight patients needed to be treated with cannabinoids for one to benefit who would have vomited or had nausea had they all received a conventional antiemetic.

Table 2.

Control of nausea and vomiting and patients' preference for treatment in trials of cannabinoid against active antiemetic or control treatment

| End point | No of trials | Event rate (No of patients)

|

Relative risk (95% CI) | No needed to treat (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis (%) | Control (%) | ||||

| Control of nausea and vomiting | |||||

| Complete control of nausea v placebo | 4 | 70 (81/116) | 57 (66/115) | 1.21 (1.03 to 1.42) | 8.0 (4.0 to 775) |

| Complete control of vomiting v placebo | 4 | 66 (76/116) | 36 (41/115) | 1.84 (1.42 to 2.38) | 3.3 (2.4 to 5.7) |

| Complete control of nausea v active | 7 | 59 (122/207) | 43 (93/215) | 1.38 (1.18 to 1.62) | 6.4 (4.0 to 16) |

| Complete control of vomiting v active | 6 | 57 (111/194) | 45 (90/201) | 1.28 (1.08 to 1.51) | 8.0 (4.5 to 38) |

| Sensitivity analysis (cannabinoids v active) | |||||

| Complete control of nausea: | |||||

| Event rate in controls 25% to 75% | 3 | 70 (75/107) | 41 (46/112) | 1.70 (1.32 to 2.18) | 3.4 (2.4 to 6.1) |

| Event rate in controls <25% or >75% | 4 | 47 (47/100) | 46 (47/103) | 1.06 (0.88 to 1.27) | 73 (6.6 to −8.1) |

| Complete control of vomiting | |||||

| Event rate in controls 25% to 75% | 4 | 72 (105/146) | 57 (87/153) | 1.26 (1.07 to 1.48) | 6.6 (3.9 to 23) |

| Event rate in controls <25% or >75% | 2 | 13 (6/48) | 6 (3/48) | 1.86 (0.53 to 6.47) | 16 (5.6 to −19) |

| Patients' rating | |||||

| Preference for cannabinoid v placebo | 4 | 76 (153/202) | 13 (27/202) | 5.67 (3.95 to 8.15) | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.8) |

| Preference for cannabinoid v active | 14 | 61 (371/604) | 26 (156/608) | 2.39 (2.05 to 2.78) | 2.8 (2.4 to 3.3) |

Active=prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, chlorpromazine, tiethylperazine, haloperidol, domperidone, alizapride.

Sensitivity analyses

One trial reported very low event rates in the control groups: 16% of patients felt nauseous with placebo and 2% with prochlorperazine.41 Chemotherapy was mainly with low emetogenic substances (vincristine, fluorouracil) (table 1).

Six trials reported event rates above 75% in the control group (fig 1). In two nausea rates with placebo were 93% and 100%, respectively, and vomiting rates were 87% and 100%.35,36 Chemotherapy was with high dose methotrexate35 or with doxorubicin and cytoxan.36 In one trial rates of nausea and vomiting were 100% despite prochlorperazine46; chemotherapy was with cisplatin. In two trials, the nausea rate was 85% despite alizapride53 and 83% despite prochlorperazine54; again, the chemotherapy regimen contained cisplatin. Finally, in one trial 90% of controls receiving prochlorperazine vomited; chemotherapy was with moderately emetogenic drugs (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil).34

When data from active controlled trials with medium control event rates (25% to 75%) were combined, cannabinoids were superior to conventional antiemetics, and numbers needed to treat were below 4 to prevent nausea and below 7 to prevent vomiting (table 2). When data from active controlled trials with extreme event rates in control groups (<25% and >75%) were combined, there were no significant differences between cannabinoids and active comparators (table 2).

It became clear that cannabinoids were antiemetic only when the components of the chemotherapy regimen and the event rates in control patients suggested a medium emetogenic setting. We therefore tried to test for dose responsiveness after excluding trials that reported extreme event rates in control groups. The largest clinically homogeneous subgroup contained just two trials, which compared dronabinol 30 mg per day with prochlorperazine 20 mg41 and dronabinol 28 mg/m2 with prochlorperazine 30 mg/m2.55 No sensible conclusion on dose-response relations with cannabinoids could be drawn. For the same reason, no conclusion could be drawn on the relative efficacy of nabilone, dronabinol, or levonantradol.

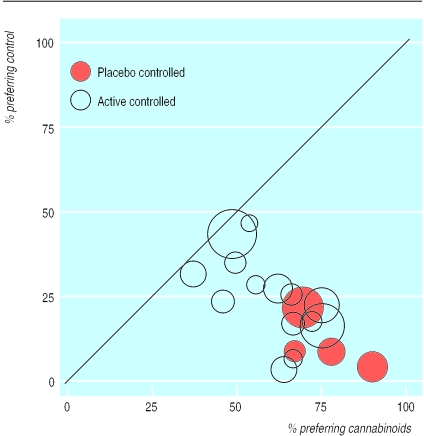

Patients' preference

At the end of 18 crossover trials, patients were asked which treatment they preferred for further chemotherapy cycles. Between 38% and 90% of patients preferred cannabinoids (fig 2). In four placebo controlled crossover trials preference for placebo was between 4% and 22%.28,47,50,61 The difference in favour of cannabinoids was significant (table 2). In 14 active controlled crossover trials 3% to 46% of patients preferred the standard antiemetic.32–34,38–40,42,44,46,51–54,59 The difference in favour of cannabinoids was significant (table 2). A subgroup analysis, taking into account history of cannabis use, was not possible since this was inconsistently reported.

Figure 2.

Percentages of patients preferring cannabinoids or control for future chemotherapy. Each symbol represents one trial. Symbol sizes are proportional to trial sizes. The solid line represents equality

In the only parallel group trial that reported preference as an end point,45 78% of the patients who had received chlorpromazine and 58% of those who had received levonantradol wished to receive the same drug for future chemotherapy cycles. This difference that was not significant (relative risk 0.74, 95% confidence interval 0.50 to 1.09).

Side effects

Side effects happened significantly more often with cannabinoids (table 3). Some side effects could be classified as potentially beneficial (for instance, a sensation of a “high,” euphoria, and drowsiness, sedation, or somnolence) whereas others were definitely harmful (for instance, dysphoria and depression, hallucinations, or paranoia). Hallucinations and paranoia occurred exclusively with cannabinoids. Arterial hypotension (>20% decrease in blood pressure compared with baseline) was also more common with cannabinoids (table 3). In 19 trials, the number of patients who withdrew from the study due to intolerable adverse effects was significantly increased with cannabinoids (table 3).

Table 3.

Rates of side effects among patients receiving cannabinoid antiemetic treatment compared with placebo or active control

| End point | No of trials | Event rate (No of patients)

|

Relative risk (95% CI) | No needed to treat (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis (%) | Control (%) | ||||

| “Beneficial” central side effects: | |||||

| “High” sensation | 8 | 35 (162/470) | 3 (17/562) | 10.6 (6.86 to 16.5) | 3.2 (2.8 to 3.7) |

| Drowsiness, sedation, somnolence | 15 | 50 (320/636) | 30 (224/737) | 1.66 (1.46 to 1.89) | 5.0 (4.0 to 6.8) |

| Euphoria* | 3 | 14 (24/168) | 1 (1/168) | 12.5 (3.00 to 52.1) | 7.3 (5.2 to 12) |

| Harmful central side effects: | |||||

| Dizziness* | 9 | 49 (173/357) | 17 (57/344) | 2.97 (2.31 to 3.83) | 3.1 (2.6 to 3.9) |

| Dysphoria or depression | 10 | 13 (39/312) | 0.3 (1/378) | 8.06 (3.38 to 19.2) | 8.2 (6.3 to 12) |

| Hallucination | 10 | 6 (26/435) | 0 (0/424) | 6.10 (2.41 to 15.4) | 17 (12 to 27) |

| Paranoia | 6 | 5 (14/285) | 0 (0/286) | 8.58 (6.38 to 11.5) | 20 (13 to 42) |

| Hypotension | 13 | 25 (124/497) | 11 (53/485) | 2.23 (1.75 to 2.83) | 7.1 (5.3 to 11) |

| Withdrawal due to side effects | 19 | 11 (108/1003) | 2 (18/1108) | 4.67 (3.07 to 7.09) | 11 (8.9 to 14) |

No studies used a placebo control.

Discussion

The evidence we have from randomised trials shows cannabinoids to be slightly better than conventional antiemetics for treating chemotherapy induced emesis, and patients prefer them. They are also more toxic. Two extreme positions could be taken, perhaps using the following arguments.

Arguments for and against

The optimistic position favours cannabinoids. Overwhelmingly, patients preferred cannabinoids for future chemotherapy, even though cannabinoids were only slightly more effective than other antiemetics and only for moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Patients' subjective view on preference is more important than the scientifically evaluated efficacy of that intervention. Although side effects occur more often with cannabinoids, these may be concentrated in a fairly small number of patients so that most patients find cannabinoids effective without undue adverse effects. There are even some potentially beneficial side effects. Of 100 cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy who received a cannabinoid 30 more would be sedated, 20 would feel a sensation of a “high,” and 15 would feel euphoric compared with 100 who received a conventional antiemetic. Some patients may perceive a degree of sedation or somnolence as useful during chemotherapy. Thus, further clinical trials with cannabinoids in chemotherapy are justified.

The pessimistic position favours conventional antiemetics, as cannabinoids are not much better, and their toxicity is unacceptably high (dizziness, dysphoria, hallucinations, paranoia). The toxic effects may lead to study withdrawal. There were no comparisons of cannabinoids with a serotonin (5-HT3) receptor antagonist, the best comparator for prevention of acute emesis in highly emetogenic chemotherapy. It is, however, unlikely that cannabinoids would be more effective and less toxic than a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist.

The correct position is probably somewhere in the middle. Undoubtedly, most patients preferred cannabinoids for future chemotherapy cycles. One in two compared with placebo, and one in three compared with conventional antiemetics would have preferred to receive cannabinoids again. We do not know whether the incidence of cannabinoid related “beneficial” side effects was related to this overwhelming preference for cannabinoids for future chemotherapy.

Efficacy and safety

Before a chemical compound can be recommended for medical use, both its efficacy and safety must be proved. Cannabinoids were more effective than conventional antiemetics (prochlorperazine, metoclopramide). Of 100 cancer patients treated with oral cannabinoids during chemotherapy, 16 will not be nauseated (number needed to treat 6.4) and 13 will not vomit (8) who would have done so had they all received a conventional antiemetic. Compared with placebo, cannabinoids were obviously better, although a placebo may not be an adequate comparator in patients having chemotherapy. We could not establish a dose-response relation, mainly because there were insufficient quality data from the original trials. In some trials, dose was adjusted during the trial.34 The relation between plasma concentration of a cannabinoid and its antiemetic efficacy is unclear. In one trial, antiemetic efficacy was related to the plasma concentration of dronabinol.35 Another trial found no correlation between dronabinol serum levels and efficacy or adverse reactions.41

Defining an intervention's usefulness includes estimates of the likelihood for harm. The physical and neuropsychiatric adverse effects of long term use of cannabis are well established, based mainly on observations from long term marijuana smokers.62 Our systematic review shows clearly that cannabinoids are toxic for many patients even when taken orally and acutely (for 24 hours). Some adverse effects occurred almost exclusively with cannabinoid exposure. For instance, 5% of patients had paranoia, 6% had hallucinations, and almost 13% had dysphoria or depression (table 3). The number of patients withdrawing from the studies due to intolerable side effects is the most reliable parameter of the severity of cannabinoid related toxicity. One in eleven patients treated with cannabinoids will stop treatment who would not have stopped treatment had they taken a placebo or another antiemetic. This is an important new message for doctors, policy makers, and patients.

These results should make us think hard about the ethics of clinical trials of cannabinoids when safe and effective alternatives are known to exist and when efficacy of cannabinoids is known to be marginal. The trials analysed here are likely to be the largest subgroup on the medical use of cannabinoids and therefore the single most important source of information on their potential for harm.

Effect of bias

This meta-analysis is open to some biases, and they all have the potential to overestimate the efficacy and to underestimate the harm of cannabinoids. The trials we included were of acceptable quality according to the Oxford quality scale, with 25 of 30 trials scoring 3 or 4. In 70% of trials an adequate method of blinding was described. Most crossover trials used a double dummy design. Cannabinoids were given as tablets or intramuscular injection, so any psychological effect of smoking a joint was not a factor. However, cannabinoids showed specific adverse effects that control treatments did not, and their incidence was high. In one trial of oral nabilone, many patients identified which drug they received because of the adverse effects experienced.59 In a series of 100 blinded dronabinol and placebo treatments, nurses correctly identified the active treatment in 85% and patients in 95%; seven of the 10 errors were made by patients on the first drug trial of the study.63 We must therefore assume that most of these trials had some degree of observer bias.

Some trials studied selected groups of patients who either had not responded to conventional antiemetic prophylaxis during previous chemotherapy cycles (“high risk” patients) or regularly used cannabis. Both subgroups introduce a bias in favour of cannabinoids. The selection of refractory patients introduces bias against the regimens that do not include cannabinoids.4 Younger age and previous marijuana exposure have been identified as factors that predicted response to antiemetic treatment.64 Regular cannabis users may be more likely to believe in its antiemetic efficacy. They may also experience adverse effects of cannabis more positively than patients who have not previously taken cannabis (for instance, a “high” or somnolence). In one trial, where more than 50% of patients were regular cannabis users, only 6% did not believe that cannabis would reduce their nausea and vomiting symptoms.60 In view of the numerous biases in these trials, “preference” and “satisfaction” are likely to be surrogate end points. These endpoints alone do not allow to judge with confidence on the usefulness of cannabinoids in the control of chemotherapy related emesis.

Finally, we have the problem of size. Small trials can be greatly affected by the random play of chance.65 Of the 30 studies available for analysis, only nine had over 50 analysable patients and only four more than 100. Small size has been shown to overestimate treatment effects in other circumstances,66 and it is not possible to rule out similar effects here.

Implications

The research agenda needs to be clear. Priority should go to trials of cannabinoids for indications where there are few competing drugs, such as spasticity in multiple sclerosis. In chemotherapy, the combination of weak antiemetic efficacy with potentially beneficial side effects (sedation, euphoria) raises the question whether further trials should be designed to establish the usefulness of cannabinoids as adjuncts to modern antiemetics (for instance, 5-HT3 receptor antagonists). Minimal effective doses would then be needed. Identification of patients who are most likely to profit from the antiemetic effect of cannabinoids and least likely to suffer from neuropsychiatric adverse effects is needed.

In conclusion, the cannabinoids reviewed here were slightly superior to conventional antiemetics after chemotherapy, and patients preferred them. However, potentially serious adverse effects, even when the drugs are taken short term orally or intramuscularly, are likely to limit their widespread use. In selected patients, cannabinoids may be useful as mood enhancing adjuvants for the control of chemotherapy related sickness.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Haake from the Documentation Service of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences for his help in searching electronic databases.

Footnotes

Funding: MRT received a PROSPER grant (No 32-51939.97) from the Swiss National Science Foundation. DC was supported by the Royal College of Nursing Institute RAE Grant.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Kassirer JP. Federal foolishness and marijuana (editorial) N Engl J Med. 1997;336:366. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701303360509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grinspoon L, Bakalar JB. Marihuana as medicine: a plea for reconsideration. JAMA. 1995;273:1875–1876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris K. The cannabis remedy—wonder worker or evil weed? Lancet. 1997;350:1828. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63651-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voth EA, Schwartz RH. Medicinal applications of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and marijuana. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:791–798. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-10-199705150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doblin RE, Kleiman MA. Marijuana as antiemetic medicine: a survey of oncologists' experiences and attitudes. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1314–1319. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.7.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz RH, Beveridge RA. Marijuana as an antiemetic drug: How useful is it today? Opinions from clinical oncologists. J Addict Dis. 1994;13:53–65. doi: 10.1300/J069v13n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poster DS, Penta JS, Bruno S, Macdonald JS. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in clinical oncology. JAMA. 1981;245:2047–2051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris JA, Gardner MJ. Calculating confidence intervals for relative risk, odds ratios, and standardised ratios and rates. In: Gardner MJ, Altman DG, editors. Statistics with confidence: confidence intervals and statistical guidelines. London: BMJ Books; 1995. pp. 50–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gavaghan DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. An evaluation of homogeneity tests in meta-analysis in pain using simulations of individual patient data. Pain. 2000;85:415–424. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ. 1995;310:452–454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman D. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317:1309–1312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higi M, Niederle N, Bremer K, Schmitt G, Schmidt CG, Seeber S. Levonantradol bei der Behandlung von zytostatika-bedingter Übelkeit und Erbrechen. Dtsch med Wschr. 1982;107:1232–1234. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1070107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niiranen A, Mattson K. Antiemetic efficacy of nabilone and dexamethasone: a randomized study of patients with lung cancer receiving chemotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1987;10:325–329. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198708000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roffman RA. The controlled substances therapeutic research act in the state of Washington. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;8-9(suppl):133–40S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Citron ML, Herman TS, Vreeland F, Kransow SH, Fossieck Jr BE, Harwood S, et al. Antiemetic efficacy of levonantradol compared to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985;69:109–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham D, Forrest GJ, Soukop M, Gilchrist NL, Calder IT. Nabilone and prochlorperazine: a useful combination for emesis induced by cytotoxic drugs. BMJ. 1985;291:864–865. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6499.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham D, Bradley CJ, Forrest GJ, Hutcheon AW, Adams L, Sneddon M, et al. A randomized trial of oral nabilone and prochlorperazine compared to intravenous metoclopramide and dexamethasone in the treatment of nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy regimens containing cisplatin or cisplatin analogues. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1988;24:685–689. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(88)90300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert CJ, Ohly KV, Rosner G, Peters WP. Randomized, double-blind comparison of a prochlorperazine-based versus a metoclopramide-based antiemetic regimen in patients undergoing autologous bone marrow transplantation. Cancer. 1995;76:2330–2337. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951201)76:11<2330::aid-cncr2820761122>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Priestman SG, Priestman TJ, Canney PA. A double-blind randomised cross-over comparison of nabilone and metoclopramide in the control of radiation-induced nausea. Clin Radiol. 1987;38:543–544. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(87)80151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucraft HH, Palmer MK. Randomised clinical trial of levonantradol and chlorpromazine in the prevention of radiotherapy-induced vomiting. Clin Radiol. 1982;33:621–622. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(82)80383-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis IH, Campbell DN, Barrowcliffe MP. Effect of nabilone on nausea and vomiting after total abdominal hysterectomy. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:244–246. doi: 10.1093/bja/73.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, Morales JO, Bellman P, Yangco B, et al. Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1995;10:89–97. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(94)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ekert K, Waters KD, Jurk IH, Mobilia J, Loughnan P. Amelioration of cancer chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting by delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Med J Aus. 1979;2:657–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garb S, Beers AL, Bograd M, McMahon RT, Magalik A, Ashmann A, et al. Two-pronged study of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) prevention of vomiting from cancer chemotherapy. IRCS Med Sci. 1980;8:203–204. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stambaugh JE, Jr, McAdams J, Vreeland F. Dose ranging evaluation of the antiemetic efficacy and toxicity of intramuscular levonantradol in cancer subjects with chemotherapy-induced emesis. J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;24:480–485. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1984.tb02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levitt M, Wilson A, Bowman D, Kemel S, Krepart G, Marks V, et al. Physiologic observations in a controlled clinical trial of the antiemetic effectiveness of 5, 10, and 15 mg of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in cancer chemotherapy. Ophthalmologic implications. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:103–19S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Einhorn LH. Nabilone: an effective antiemetic agent in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 1982;9(suppl B):55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(82)80037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colls BM. Cannabis and cancer chemotherapy. Lancet. 1980;i:1187–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lane M, Smith FE, Sullivan RA, Plasse TF. Dronabinol and prochlorperazine alone and in combination as antiemetic agents for cancer chemotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1990;13:480–484. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orr LE, McKernan JF. Antiemetic effect of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol in chemotherapy-associated nausea and emesis as compared to placebo and compazine. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:76–80S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ungerleider JT, Sarna G, Fairbanks LA, Goodnight J, Andrysiak T, Jamison K. THC or compazine for the cancer chemotherapy patient—the UCLA study. Part II: patient drug preference. Am J Clin Oncol. 1985;8:142–147. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmedzai S, Carlyle DL, Calder IT, Moran F. Anti-emetic efficacy and toxicity of nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, in lung cancer chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 1983;48:657–663. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1983.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan HS, Correia JA, MacLeod SM. Nabilone versus prochlorperazine for control of cancer chemotherapy-induced emesis in children: a double-blind, crossover trial. Pediatrics. 1987;79:946–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang AE, Shiling DJ, Stillman RC, Goldberg NH, Seipp CA, Barofsky I, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic in cancer patients receiving high-dose methotrexate. A prospective, randomized evaluation. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:819–824. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-6-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang AE, Shiling DJ, Stillman RC, Goldberg NH, Seipp CA, Barofsky I, et al. A prospective evaluation of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic in patients receiving adriamycin and cytoxan chemotherapy. Cancer. 1981;47:1746–1751. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810401)47:7<1746::aid-cncr2820470704>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colls BM, Ferry DG, Gray AJ, Harvey VJ, McQueen EG. The antiemetic activity of tetrahydrocannabinol versus metoclopramide and thiethylperazine in patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy. N Z Med J. 1980;91:449–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crawford SM, Buckman R. Nabilone and metoclopramide in the treatment of nausea and vomiting due to cisplatinum: a double blind study. Med Oncol Tumor Pharmacother. 1986;3:39–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02934575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dalzell AM, Bartlett H, Lilleyman JS. Nabilone: an alternative antiemetic for cancer chemotherapy. Arch Dis Child. 1986;61:502–505. doi: 10.1136/adc.61.5.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Einhorn LH, Nagy C, Furnas B, Williams SD. Nabilone: an effective antiemetic in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:64–9S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frytak S, Moertel CG, O Fallon JR, Rubin J, Creagan ET. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic for patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. A comparison with prochlorperazine and a placebo. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:825–830. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-6-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.George M, Pejovic MH, Thuaire M, Kramar A, Wolff JP. Randomized comparative trial of a new anti-emetic: nabilone, in cancer patients treated with cisplatin. Biomed Pharmacother. 1983;37:24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gralla RJ, Tyson LB, Bordin LA, Clark RA, Kelsen DP, Kris MG, et al. Antiemetic therapy: a review of recent studies and a report of a random assignment trial comparing metoclopramide with delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Cancer Treat Rep. 1984;68:163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herman TS, Einhorn LH, Jones SE, Nagy C, Chester AB, Dean JC, et al. Superiority of nabilone over prochlorperazine as an antiemetic in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1295–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906073002302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hutcheon AW, Palmer JB, Soukop M, Cunningham D, McArdle C, Welsh J, et al. A randomised multicentre single blind comparison of a cannabinoid anti-emetic (levonantradol) with chlorpromazine in patients receiving their first cytotoxic chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1983;19:1087–1090. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(83)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johansson R, Kilkku P, Groenroos M. A double-blind, controlled trial of nabilone vs prochlorperazine for refractory emesis induced by cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 1982;9:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(82)80032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones SE, Durant JR, Greco FA, Robertone A. A multi-institutional phase III study of nabilone vs placebo in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer Treat Rev. 1982;9:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(82)80035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kluin-Neleman JC, Neleman FA, Meuwissen OJAT, Maes RAA. Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) as an antiemetic for patients receiving cancer chemotherapy; a double blind cross-over trial against placebo. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1979;21:228–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lane M, Vogel CL, Ferguson J, Krasnow S, Saiers JL, Hamm J, et al. Dronabinol and prochlorperazine in combination for treatment of cancer chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Pain Symptom Manag. 1991;6:352–359. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(91)90026-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levitt M. Nabilone vs placebo in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in cancer patients. Cancer Treat Rev. 1982;9(suppl B):49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(82)80036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCabe M, Smith FP, Macdonald JS, Woolley PV, Goldberg D. Efficacy of tetrahydrocannabinol in patients refractory to standard antiemetic therapy. Invest New Drugs. 1988;6:243–246. doi: 10.1007/BF00175407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neidhart JA, Gagen MM, Wilson HE, Young DC. Comparative trial of the antiemetic effects of THC and haloperidol. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:38–42S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Niederle N, Schutte J, Schmidt CG. Crossover comparison of the antiemetic efficacy of nabilone and alizapride in patients with nonseminomatous testicular cancer receiving cisplatin therapy. Klin Wochenschr. 1986;64:362–365. doi: 10.1007/BF01728184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niiranen A, Mattson K. A cross-over comparison of nabilone and prochlorperazine for emesis induced by cancer chemotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol. 1985;8:336–340. doi: 10.1097/00000421-198508000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Orr LE, McKernan JF, Bloome B. Antiemetic effect of tetrahydrocannabinol. Compared with placebo and prochlorperazine in chemotherapy-associated nausea and emesis. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:1431–1433. doi: 10.1001/archinte.140.11.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pomeroy M, Fennelly JJ, Towers M. Prospective randomized double-blind trial of nabilone versus domperidone in the treatment of cytotoxic-induced emesis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1986;17:285–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00256701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sallan SE, Zinberg NE, Frei E., 3rd Antiemetic effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:795–797. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197510162931603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sallan SE, Cronin C, Zelen M, Zinberg NE. Antiemetics in patients receiving chemotherapy for cancer: a randomized comparison of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and prochlorperazine. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:135–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198001173020302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steele N, Gralla RJ, Braun DW, Jr, Young CW. Double-blind comparison of the antiemetic effects of nabilone and prochlorperazine on chemotherapy-induced emesis. Cancer Treat Rep. 1980;64:219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ungerleider JT, Andrysiak T, Fairbanks L, Goodnight J, Sarna G, Jamison K. Cannabis and cancer therapy: a comparison of Delta-9-THC and prochlorperazine. Cancer. 1982;50:636–645. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820815)50:4<636::aid-cncr2820500404>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wada JK, Bogdon DL, Gunnell JC, Hum GJ, Gota CH, Rieth TE. Double-blind, randomized, crossover trial of nabilone vs. placebo in cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 1982;9(Suppl B):39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(82)80034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hubbard JR, Franco SE, Onaivi ES. Marijuana: medical implications. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:2583–2593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seipp CA, Chang AE, Shiling DJ, Rosenberg SA. In search of an effective antiemetic: a nursing staff participates in marijuana research. Cancer Nursing. 1980;Aug:271–276. doi: 10.1097/00002820-198008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vinciguerra V, Moore T, Brennan E. Inhalation marijuana as an antiemetic for cancer chemotherapy. New York State J Med. 1988;88:525–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moore RA, Gavaghan D, Tramèr MR, Collins S, McQuay HJ. Size is everything—the impact of event rate variation on clinical trials and meta-analysis. Pain. 1998;78:208–216. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moore RA, Tramèr MR, Carroll D, Wiffen PJ, McQuay HJ. Quantitative systematic review of topically-applied non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. BMJ. 1998;316:333–338. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]