Abstract

Akt activation by the IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) has been posited to be a mechanism of intrinsic resistance to mTORC1 inhibitors ("rapalogues") for sarcomas. Here we demonstrate that rapamycin-induced phosphorylation of Akt can occur in an IGF-1R-independent manner. Analysis of synovial sarcoma cell lines demonstrated that either the IGF-1R or the PDGF receptor alpha (PDGFRA) could mediate intrinsic resistance to rapamycin. Repressing expression of PDGFRA or inhibiting its kinase activity in synovial sarcoma cells blocked rapamycin-induced phosphorylation of Akt and decreased tumor viability. Expression profiling of clinical tumor samples revealed that PDGFRA was the most highly expressed kinase gene among several sarcoma disease subtypes, suggesting that PDGFRA may be uniquely significant for synovial sarcomas. Tumor biopsy analyses from a synovial sarcoma patient treated with the mTORC1 inhibitor everolimus and PDGFRA inhibitor imatinib mesylate confirmed that this drug combination can impact both mTORC1 and Akt signals in vivo. Together, our findings define mechanistic variations in the intrinsic resistance of synovial sarcomas to rapamycin and suggest therapeutic strategies to address them.

Keywords: mTOR, rapamycin, PDGFR, synovial sarcoma

INTRODUCTION

Evidence for PI3K/Akt/mTOR (phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate kinase/protein kinase B (PKB)/mammalian Target of Rapamycin) pathway activation in sarcomas has made this a pathway of interest for therapeutic development. Signaling through the pathway begins with ligand activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) (such as the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) and the platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRA and PDGFRB)) at the plasma membrane, leading to the recruitment of PI3K directly to the receptor. PI3K converts phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), which then recruits Akt to the membrane where it is activated by phosphorylation.

Mouse models with activated Akt have demonstrated that oncogenesis through this pathway is dependent upon downstream activation of mTOR (1–3). mTOR regulates protein translation through rapamycin- and nutrient- sensitive mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), which phosphorylates S6K 1/2 (ribosomal S6 kinase 1/2) and 4E-BP1 (eukaryotic initiation factor-4E (eIF-4E)-binding protein) to promote mRNA translation. mTOR also associates with a second rapamycin-resistant complex known as mTORC2. mTORC2 phosphorylates Akt at serine 473 (4, 5), which together with threonine 308 phosphorylation results in full Akt activation (6).

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is activated in sarcomas via several mechanisms, including genetic mutations within the pathway (e.g. KIT and PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST); PIK3CA mutations in myxoid/round-cell liposarcomas (7)) or other pathognomonic alterations that promote reliance upon the pathway (e.g. EWS-FLI-1 gene fusion-driven oncogenesis is dependent upon IGF-1R in Ewing sarcoma (EWS)(8)). These observations led to clinical trials testing mTORC1 allosteric inhibitors in sarcoma patients. Rapamycin (sirolimus) was the first mTORC1 inhibitor identified; several rapamycin analogues (known as “rapalogues”) have since been developed. Mechanistically, rapalogues bound to FK506-binding protein 12 (FKBP12) destabilize the multimeric mTORC1 protein complex, resulting in inhibition of its activity. The overall clinical activity of these agents is modest as no more than 5% of sarcoma patients on these trials had meaningful reductions in tumor size (9, 10).

A mechanism of intrinsic mTORC1 inhibitor resistance identified in several cancers, including sarcoma, is the induction of IGF-1R-dependent Akt activation due to a release of negative feedback inhibition (11–14). Biopsies from rapalogue-treated patients confirmed that Akt activation occurs clinically (11, 15) and in one study portended a poorer prognosis (15). The observation that combining rapalogues with IGF-1R inhibitors results in suppression of Akt activation and enhancement of drug-mediated anti-proliferative effects in preclinical models (14) led to efforts to clinically develop this combination for sarcoma patients. However, combined rapamycin and IGF-1R inhibition may not be universally applicable to all sarcoma subtypes (16–18) and IGF-1R-independent mechanisms of rapamycin-induced Akt activation may also be important. To investigate this question, we examined the IGF-1R dependency of rapamycin-induced Akt activation in a sarcoma cell line panel utilizing the IGF-1R targeting antibody R1507 (Roche). R1507 (Roche) is a fully human monoclonal antibody (IgG1) that binds the extracellular domain of IGF-1R with high affinity, causing displacement of IGF-1 and IGF-2 from the receptor as well as downregulation of receptor levels. R1507 does not cross react with human or mouse insulin receptor (IR). We discovered that rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation in sarcoma cell lines can be either IGF-1R-dependent or -independent. In synovial sarcomas, PDGFRA is an alternate RTK that can mediate this biologic process in a subset of tumors, and hence, is an attractive therapeutic target to inhibit in combination with mTORC1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Drugs

R1507, the humanized monoclonal anti-IGF-1R antibody, was provided by Roche (San Francisco, CA). Rapamycin was purchased from EMD Chemicals (Rockland, MA). Imatinib was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). R1507 was stored in a buffered solution of 250 mM trehalose, 20 mM C-histidine, 0.1% Tween 20, and stored at −20°C. Rapamycin and imatinib were dissolved in DMS0 and stored at −20°C. IGF-1, EGF, SCF, PDGF AB, and cycloheximide were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Cell Lines

SYO-1 (19) and HS-SY-II (20) synovial sarcoma cell lines were provided by Dr. Marc Ladanyi (MSKCC, New York, NY). These cell lines were authenticated by confirming expression of the pathognomonic SYT-SSX fusion gene by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in March 2011. Ewing sarcoma (TC71, CHP100, A673) and desmoplastic round cell tumor (JN-DSRCT-1 (21)) cell lines were provided by Dr. Melinda S. Merchant (Center for Cancer Research, NCI/NIH, Bethesda, Maryland). Rhabdomyosarcoma (RD), dedifferentiated liposarcoma (LS141, DDLS), and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST, ST8814) cell lines were provided by Dr. Samuel Singer (MSKCC, New York, NY). Osteosarcoma SAOS-2 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC).

Cell viability assays

Cell viability assays were performed with the Dojindo Molecular Technologies kit (Rockville, MD) per manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 2000–5000 cells were plated in 96-well plates and then treated with the indicated drugs. Media was replaced with 100 µl of media with 10% serum and 10% CCK-8 solution (Dojindo Molecular Technologies Kit). After 1 hour, the optical density was read at 450 nm using a Spectra Max 340 PC (Molecular Devices Corp) to determine viability. Background values from negative control wells without cells were subtracted for final sample quantification.

Western Blots

Western blots were performed as previously described (22). Briefly, cell lysates were prepared with RIPA lysis buffer. Equal amounts of protein were electrophoresed on 4–12% gradient gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to 0.45 micron nitrocellulose membranes (Thermo Scientific). After blocking with 5% milk, membranes were probed with primary antibodies. Bound antibodies were detected with horse radish peroxidase secondary antibodies (GE Healthcare) and visualized by Enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (GE Healthcare). All primary antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling (Boston, MA).

RTK assays

RTK assays were performed with the Proteome Profiler™ Array Kit (R&D, MN) per manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunoprecipitation-Western (IP-Western) Analysis

Immunoprecipitation was performed using 500 µg of total protein. The cell lysates were incubated with 1:50 dilutions of PDGFRA antibody or rabbit IgG control antibody overnight at 4°C. The following day 50 µl of protein A/G agarose beads were added for an overnight incubation at 4°C. Immune complexes were then washed with RIPA buffer five times and suspended in 25 µl of 4X loading buffer and analyzed by Western blot.

Gene Silencing

Experiments with small interfering RNAs (siRNA) were performed as previously described (22). Pooled siRNA constructs targeting PDGFRA (L-003162) and non-targeting, control siRNA (D-001810) were purchased from Dharmacon (ON-TARGET plus SMART pool; Lafayette, CO). The SYT-SSX siRNA was previously published and validated (23); the sense and antisense sequences 5’-CCAGAUCAUGCCCAAGAAGdTdT-3’ and 5’-CUUCUUGGGCAUGAUCUGGdTdT-3’ target the breakpoint of both Type I and Type II fusions.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed as previously described (24). Gene-specific probe and primer sets from TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems) were used to detect PDGFRA, SYT-SSX (23), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) transcripts. The relative expression of PDGFRA was calculated by normalizing to GAPDH.

PDGFRA Overexpression

The PDGFRA expression plasmid was provided by Dr. Marc Ladanyi (MSKCC, New York, NY). Cells were transiently transfected with empty vector and PDGFRA expression plasmids as previously described (25).

Protein stability experiments

Synovial sarcoma cells were transfected with control or SYT-SSX siRNA (Dharmacon) as described above. After transfection, cells were treated with 100 mg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for the time points indicated. The cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by Western blot. For band densitometry, an image of the Western blot was saved in high resolution grey color/JPEG format and analyzed with Image J software.

Expression microarray analysis

RNA was isolated from 139 sarcoma patient tumor samples and 17 cell lines or xenografts representing 5 different sarcoma histologic subtypes. RNA was hybridized to Affymetrix U133A arrays. Microarray data were normalized with the robust multi-array average (RMA) method. These expression microarray data are previously published (26) and are freely available at: http://cbio.mskcc.org/Public/sarcoma_array_data/.

We identified 739 probe sets on a U133A chip corresponding to 432 genes with kinase domains based on searches of the Affymetrix annotation database, published data and genome databases. This represented 83% of the 518 known protein kinase genes. To identify differentially expressed kinase genes, we used two-tailed t-tests with a restrictive Bonferroni correction method with a cut-off p-value 0.01 for multiple comparisons. Differential expression of kinase genes in synovial sarcoma was defined relative to the other 4 groups as a whole.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis of clinical cases

For 57 synovial sarcoma cases, immunohistochemistry was performed on 4-micron formalin-fixed paraffin embedded slides using PDGFRA and IGF-1R antibodies (Ventana, pre-diluted) following standard protocols. The scoring for both antibodies was quantitated on a 0 to 2+ scale: 0 = no or faint/weak staining, 1+ = moderate staining, and 2+ = strong staining. Staining of 2+ was considered positive for PDGFRA. 1+ and 2+ were considered positive for IGF-1R. Photomicrographs were taken with our Leica DM5500 microscope and Openlab 5.0 imaging software.

Western blot of clinical tumor samples

Pre-treatment (within 2 weeks of drug therapy) and on treatment (between weeks 2 and 3 of therapy) biopsies were performed on a patient participating in a National Cancer Institute (NCI) study entitled, “A Phase 1b/2 Study of Imatinib in Combination with Everolimus in Synovial Sarcoma” (NCI# 8603). This protocol was reviewed and approved by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board and has been registered to www.ClinicalTrials.gov (Trial registration ID: NCT01281865). Informed consent was obtained to participate in the therapeutic study as well as the research biopsies. For Western blot analysis of frozen tumor samples, 250 µl of cold RIPA buffer was added to the sample grinding kit tube (GE healthcare) followed by a flash frozen tumor sample (1–2 mm). The tumor was disintegrated by grinding using a pestle. The samples were centrifuged and the supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube. Protein concentrations were measured and analyzed by Western blot.

Statistical analysis

All in vitro experiments were carried out at least 2–3 times. Standard deviation was calculated where indicated.

RESULTS

Evaluating combined mTORC1 and IGF-1R inhibition in a panel of sarcoma cell lines reveals both IGF-1R dependence and independence

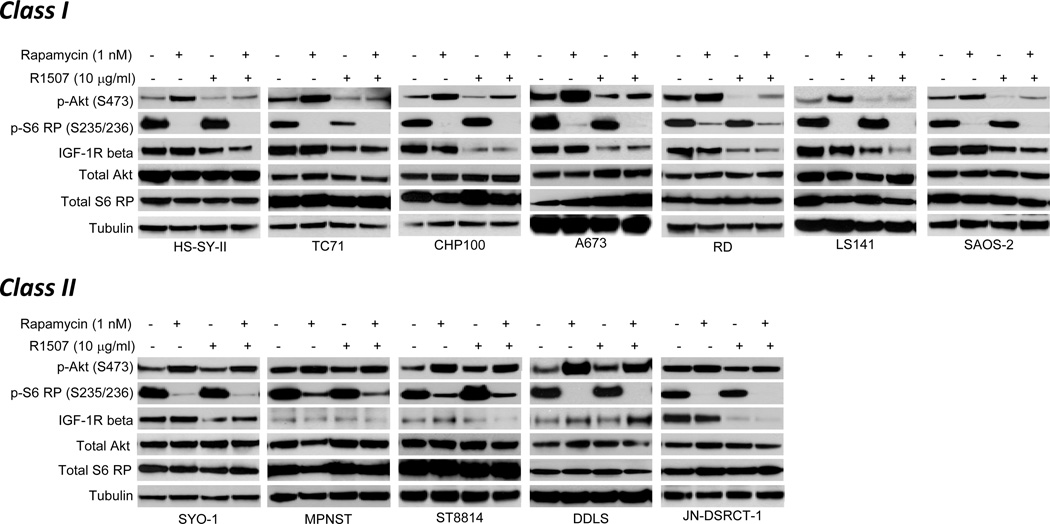

The impact of mTORC1 and IGF-1R inhibition with rapamycin and R1507, respectively, was evaluated in a panel of 12 non-GIST soft-tissue and bone sarcoma cell lines. Histologies represented in the panel included synovial sarcoma (HS-SY-II, SYO-1), Ewing sarcoma (TC71, CHP100, A673), embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (RD), dedifferentiated liposarcoma (LS141, DDLS), malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST, ST8814), osteosarcoma (SAOS-2), and desmoplastic small round cell tumor (JN-DSRCT-1). In all the cells, rapamycin inhibited S6 ribosomal protein (S6 RP) phosphorylation (at serines 235/236), consistent with mTORC1 pathway inhibition (Figure 1). Rapamycin also increased Akt phosphorylation at serine 473 in 11 of the 12 cell lines (JN-DSRCT-1 was the exception) (Figure 1). In all the cell lines with detectable IGF-1R protein, R1507 reduced IGF-1R protein levels, indicative of receptor internalization/degradation, a marker of antibody-mediated IGF-1R targeting (27). The impact of R1507-mediated IGF-1R inhibition was grouped into two categories. For 7 cell lines (designated “Class I”), R1507 partially or completely suppressed rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation (Figure 1). In almost all these cells, R1507 alone also suppressed Akt phosphorylation, suggesting a degree of generalized IGF-1R dependence in Class I cells. In the five remaining cell lines (designated “Class II”), R1507 failed to suppress Akt phosphorylation alone or in combination with rapamycin (Figure 1). The impact upon Akt phosphorylation correlated to tumor cell viability: the R1507 and rapamycin combination cooperatively suppressed sarcoma cell viability in only the Class I, but not Class II, cells (Supplementary Figure 1). We concluded that Akt activation in Class II cell lines was mediated through IGF-1R-independent mechanisms, rendering them resistant to strategies directed at IGF-1R inhibition either alone or in combination with rapamycin.

Figure 1.

Rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation occurs through both IGF-1R-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Western blot analysis of 12 sarcoma cell lines treated with rapamycin and R1507 alone or in combination. Cells were treated with vehicles, 1 nM rapamycin, 10 µg/ml R1507, or both in the presence of serum for 6 hours and analyzed by Western blot. S6 RP, S6 ribosomal protein; IGF-1R beta, beta subunit of the IGF-1 receptor.

Exogenous growth factors are necessary for rapamycin-induced Akt activation in both Class I and Class II synovial sarcoma cell lines

While susceptibility to IGF-1R targeting in rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines has been directly correlated to receptor expression levels (28), IGF-1R-independence in this panel was observed both in cells with detectable IGF-1R protein (SYO-1, JN-DSRCT-1) and those with marginal receptor expression (MPNST, ST8814, DDLS) (Figure 1). In fact, IGF-1R expression in the R1507-resistant synovial sarcoma cell line SYO-1 was comparable to that in the Class I synovial sarcoma cell line HS-SY-II (Figure 1), demonstrating that alternate mechanism(s) of rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation may be relevant even in the context of intact IGF-1R expression. We next focused upon delineating the basis for this differential susceptibility to IGF-1R targeting observed in the synovial sarcoma cell lines.

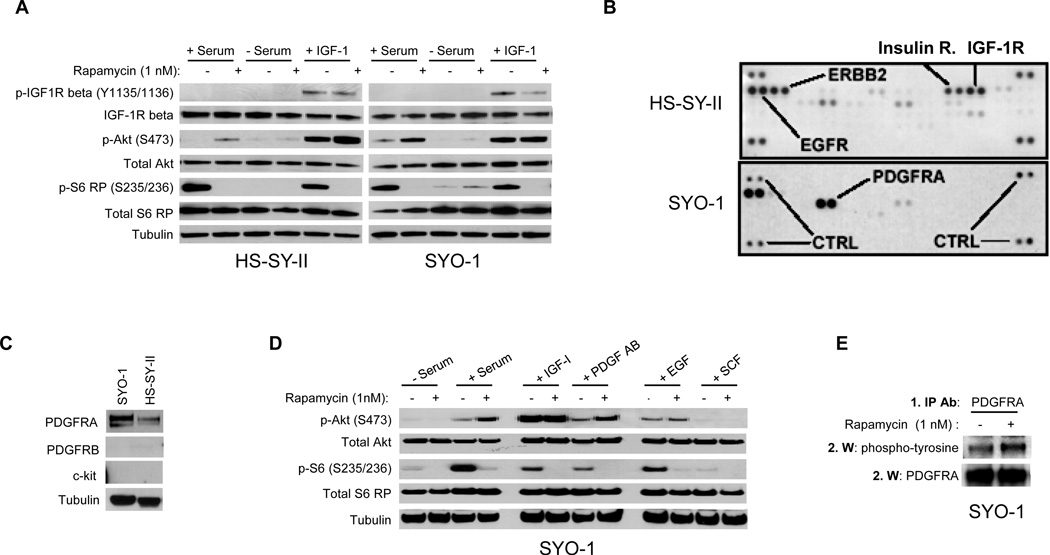

To determine if Akt activation in these cells is dependent upon growth factor signaling, serum-starved HS-SY-II and SYO-1 cells were treated with either vehicle or rapamycin in the presence or absence of serum (Figure 2A). In both cell lines, rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation was observed only in the context of serum, establishing that the exogenous addition of one or more growth factor ligand(s) is/are required for both classes of cells. Consistent with our original classification, purified IGF-1 was sufficient to restore rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation in serum-starved HS-SY-II cells (Class I) (Figure 2A). IGF-1 addition to serum-starved SYO-1 cells only resulted in increased basal Akt phosphorylation, but not rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation. Hence, while SYO-1 cells possess a functional IGF-1R signaling apparatus that can be stimulated to transduce signals to Akt, this pathway is not activated in response to mTORC1 inhibition.

Figure 2.

Exogenous growth factors are required for rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation in synovial sarcoma cell lines. A) Western blot analysis of synovial sarcoma cell lines HS-SY-II and SYO-1 treated with rapamycin in the absence or presence of exogenous growth factors. SYO-1 cells were cultured in serum-free media for 24 hours, then treated with vehicle or 1 nM rapamycin in the context of 10% serum, no serum, or 25 ng/ml of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) for 6 hours (growth factors were added to cells 5 minutes before the drugs), and then analyzed by Western blot. B) RTK antibody array analysis of HS-SY-II and SYO-1 cellular lysates cultured in the presence of serum. The blots reflect the phosphorylation status of 42 RTKs. Duplicate spots in the corners of each blot serve as positive controls. C) Western blot of HS-SY-II and SYO-1 whole cell lysates to detect the receptors indicated. D) Western blot analysis of SYO-1 cells treated with rapamycin in the context of various growth factor ligands. Cells were serum-starved for 24 hours and then treated with vehicle or 1 nM rapamycin in the absence of serum or in the presence of 10% serum, 25 ng/ml IGF-1, 25 ng/ml platelet-derived growth factor AB (PDGF AB), 25 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF), or 25 ng/ml stem cell factor (SCF). E) Immunoprecipitation-western blot analysis (IP-Western) of PDGFRA phosphorylation at tyrosine residues. SYO-1 cells were treated with vehicle or rapamycin for 6 hours in the presence of serum and whole cell lysates were prepared. PDGFRA was immunoprecipitated from these lysates, and those immunoprecipitates were then electrophoresed into a polyacrylamide gel for Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. IP ab, immunoprecipitation antibody; W, Western blot antibody.

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) mediates rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation in SYO-1 cells

In order to identify the potential RTK(s) responsible for the induction of Akt phosphorylation in rapamycin-treated SYO-1 cells, the phosphorylation status of 42 RTKs in both HS-SY-II and SYO-1 cells were profiled utilizing an RTK antibody array (Proteome Profiler, R&D Systems) in the presence of serum (Figure 2B). A strong phosphorylated IGF-1R (and insulin receptor) signal was observed in HS-SY-II cells but not in SYO-1 cells, suggesting baseline IGF-1R activation in the Class I cell line but not the Class II. Conversely, a strong phosphorylated platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) signal was present in SYO-1 cells, while only a modest one was detected in HS-SY-II (Figure 2B). This correlated to higher total PDGFRA receptor levels in SYO-1 cells compared to HS-SY-II (Figure 2C). No signal was detected for phosphorylated PDGFR beta (PDGFRB) in the RTK antibody array. Other RTKs activated at baseline included epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in both cell lines and Erbb2 (HS-SY-II only).

In order to determine if activation of a singular RTK pathway is sufficient to facilitate rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation, the impact of rapamycin upon Akt was tested in SYO-1 cells exposed in isolation to purified growth factor ligands that activate each of the RTKs identified in the antibody arrays (Figure 2D). Each growth factor with the exception of the c-kit ligand (stem cell factor (SCF)) stimulated Akt phosphorylation, but only the addition of PDGF AB ligand recapitulated rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation observed with serum addition. Since commercial Western blot antibodies directed against specific phosphorylated sites on RTKs, including PDGFRA, were not sufficiently sensitive or specific for serum-exposed sarcoma cells, we evaluated PDGFRA phosphorylation status by immunoprecipitating the receptor and analyzing the immune complexes for the presence of phosphorylated tyrosines by Western blot. In the presence of serum, rapamycin increased PDGFRA tyrosine phosphorylation, consistent with receptor activation upon mTORC1 inhibition (Figure 2E). RTK arrays performed on vehicle- and rapamycin-treated cells in the presence of serum confirmed that none of the other assayed RTKs were activated in response to rapamycin (Supplementary Figure 2).

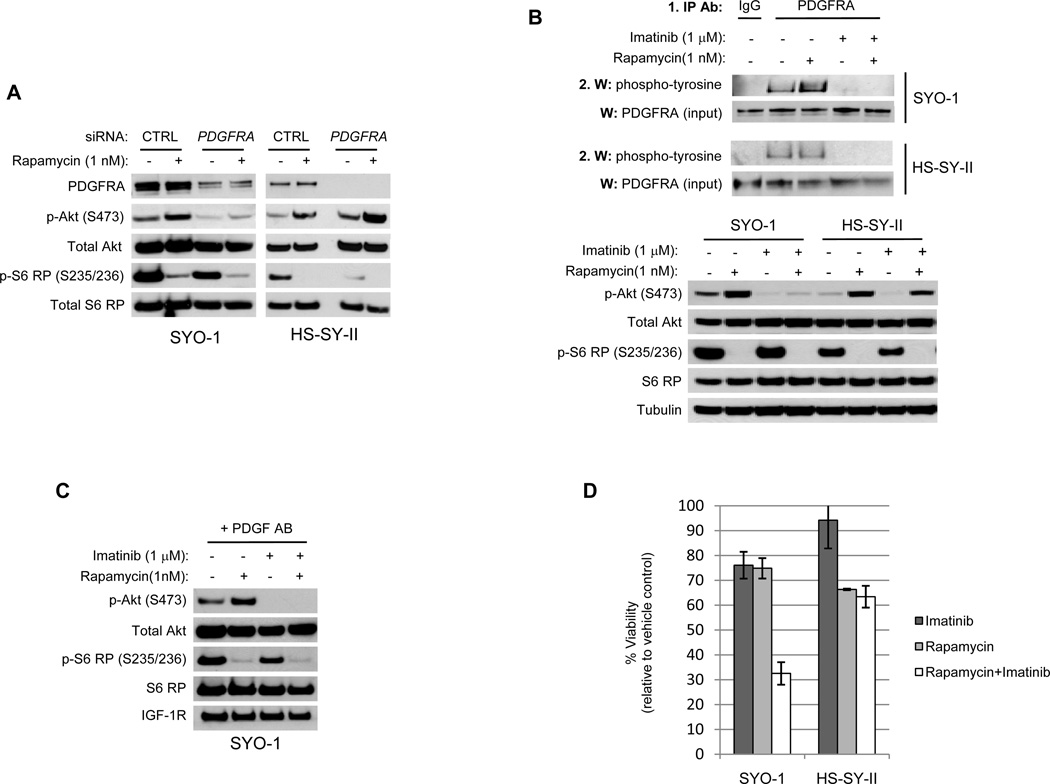

To assess if PDGFRA is required for rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation, pooled PDGFRA-targeting siRNA constructs (Dharmacon, ON-TARGET plus SMART pool) were transfected into SYO-1 and HS-SY-II cells to suppress receptor expression. Decreasing PDGFRA levels abrogated rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation in only SYO-1 cells, not HS-SY-II (Figure 3A). We next utilized the small molecule inhibitor imatinib mesylate to assess the impact of pharmacologically inhibiting PDGFRA kinase activity. Imatinib alone and in combination with rapamycin inhibited PDGFRA phosphorylation in both SYO-1 and HS-SY-II cells, but suppressed rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation only in SYO-1 cells (Figure 3B). While imatinib can inhibit the activity of other PDGFRA-related Type III RTKs such as PDGFRB and c-kit/CD117, each of these receptors were not detectable by Western blot in either SYO-1 or HS-SY-II cells (Figure 2C) (or in the phosphorylated RTK array after rapamycin (Supplementary Figure 2)). Furthermore, imatinib inhibited Akt phosphorylation induced by rapamycin in serum-starved SYO-1 cells exposed to PDGF AB ligand in isolation, affirming that imatinib can specifically modulate PDGF-mediated Akt phosphorylation (Figure 3C). As was observed with R1507, the differential impact upon Akt phosphorylation correlated to cellular viability as the combination cooperatively suppressed tumor cell proliferation in only the SYO-1 cells, and not HS-SY-II, in the context of serum (Figure 3D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that in SYO-1 cells PDGFRA induces Akt phosphorylation in response to mTORC1 inhibition, suggesting that targeting alternate RTKs other than IGF-1R may be critical for overcoming intrinsic sarcoma cell resistance to mTORC1 inhibition.

Figure 3.

PDGFRA is required for rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation in SYO-1 cells. A) Western blot analysis of SYO-1 and HS-SY-II cells treated with rapamycin after transfection of pooled siRNA constructs. Cells were transfected with either control (CTRL) or PDGFRA pooled siRNA constructs (Dharmacon, ON-TARGET plus SMART pool) for 48 hours and then treated with either vehicle or 1 nM rapamycin for 6 hours. Cell lysates were created and analyzed by immunoblot. B) IP-Western and Western blot analysis of SYO-1 and HS-SY-II cells treated with rapamycin and imatinib alone or in combination. Cells were treated with vehicle, 1 nM rapamycin, 1 µM imatinib, or both for 6 hours. IP-Western was performed as described in Figure 2E to assess PDGFRA tyrosine phosphorylation status (a non-targeting IgG antibody was used as a control for the immunoprecipitation); “input” blots indicate the total PDGFRA protein levels detected in the whole cell lysates before immunoprecipitation. Western blot on whole cell lysates was also performed to assess the phosphorylation status of Akt and S6 RP. IP ab, immunoprecipitation antibody; W, Western blot antibody. C) Western blot analysis of SYO-1 cells treated with rapamycin and imatinib alone or in combination in the context of PDGF AB ligand alone. Cells were serum-starved for 24 hours and then treated with drugs as described in B) in the presence of 25 ng/ml PDGF AB (added 5 minutes before the drugs). D) Viability assays were performed on SYO-1 and HS-SY-II cells treated with rapamycin and imatinib alone or in combination in the presence of serum. Cells were treated with drugs as described in B) for 72 hours and viability assays were performed. % Viability= (Viability(Drug treatment))/(Viability(Vehicle))×100. Results are the mean of three replicates. Error bars represent standard deviations.

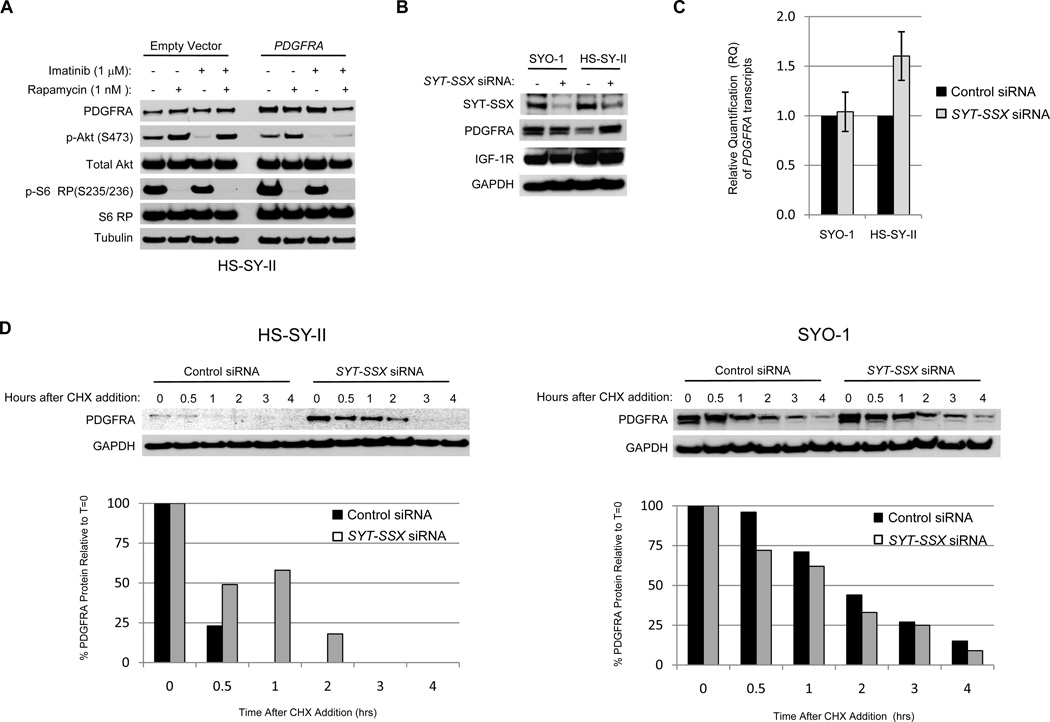

High PDGFRA expression is a critical determinant of imatinib sensitivity and can be regulated by the synovial sarcoma gene fusion SYT-SSX

Since SYO-1 cells express higher total PDGFRA protein levels than HS-SY-II cells (Figure 2C), we hypothesized that the differential susceptibility to PDGFRA targeting in the synovial sarcoma cell lines may be related to this discrepancy in PDGFRA. To test if higher PDGFRA expression could confer greater susceptibility to imatinib-mediated regulation of Akt phosphorylation, HS-SY-II cells were transfected with either a PDGFRA expression plasmid or empty vector and then subjected to drug treatment. Transfection of the PDGFRA expression plasmid resulted in 2.6 fold higher PDGFRA expression relative to empty vector-transfected cells (calculated by densitometry). High PDGFRA expression conferred a new susceptibility to imatinib-mediated inhibition of rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation (Figure 4A), suggesting that the level of PDGFRA expression may be a critical determinant of RTK dependence.

Figure 4.

The level of PDGFRA expression determines susceptibility to imatinib regulation of Akt phosphorylation and is negatively regulated by the SYT-SSX1 fusion gene product. A) Western blot of HS-SY-II cells treated with rapamycin and imatinib alone or in combination after transfection of a PDGFRA expression plasmid. Cells were transfected with a PDGFRA expression plasmid or empty vector for more than 24 hours and then were treated with vehicle, 1 nM rapamycin, 1 µM imatinib, or both for 6 hours and Western blot was performed. B) Western blot of SYO-1 and HS-SY-II cells transfected with unrelated control or SYT-SSX targeting siRNAs. Cells were transfected with the siRNA constructs for 48 hours and Western blots were then performed. The SYT-SSX fusion protein was detected with an antibody targeting the N-terminus of the SYT protein. C) Quantitative real-time PCR of SYO-1 and HS-SY-II cells transfected with control and SYT-SSX targeting siRNA duplexes. The CT values for PDGFRA in each condition were normalized to GAPDH CT values. The relative quantification (RQ) for SYT-SSX siRNA treated samples was determined relative to the control siRNA treated samples for each cell line (RQ for control siRNA samples were set to 1). D) Western blot of HS-SY-II and SYO-1 cells transfected with control or SYT-SSX targeting siRNA duplexes and then treated with cycloheximide to evaluate PDGFRA protein stability. The PDGFRA Western blot bands were quantified by band densitometry. CHX, cycloheximide.

We next investigated the potential mechanism by which PDGFRA is differentially expressed in SYO-1 and HS-SY-II cells. Essentially all synovial sarcomas possess the pathognomonic t(X;18)(p11;q11) translocation which produces the fusion gene SYT (SS18)-SSX. Variability in the Xp11 breakpoint produces a fusion of the SYT gene with either the SSX1 or SSX2 (and rarely SSX4) genes. The ratio of SYT-SSX1 (Type 1 fusion) to SYT-SSX2 (Type 2 fusion) tumors is close to 2:1 (29, 30) and each fusion impacts tumor biology in clinically distinct ways (30).

The HS-SY-II cell line possesses the Type 1 fusion (20), and the SYO-1 cell line the Type 2 (19). To investigate how each fusion type may contribute to PDGFRA expression levels, cells were transfected with an siRNA duplex that can suppress the expression of both SYT-SSX fusion types by targeting the breakpoint region of the translocation (the design and validation of this siRNA construct has been previously published (23) (see Methods for sequence)). While decreasing Type 2 gene fusion expression failed to alter IGF-1R or PDGFRA expression in SYO-1 cells, decreasing Type 1 fusion expression in HS-SY-II cells increased PDGFRA protein levels (Figure 4B), implying that the Type 1 fusion gene can negatively regulate PDGFRA expression. Both PDGFRA transcript levels and protein half-life were examined to better understand the mechanism by which reducing fusion gene expression could impact PDGFRA levels. Quantitative real-time PCR revealed only a modest increase in PDGFRA mRNA levels in HS-SY-II cells after suppression of SYT-SSX1 expression while no change was detected in SYO-1 cells (Figure 4C). Utilizing cycloheximide to block mRNA translation revealed that at baseline the PDGFRA protein half-life in SYO-1 cells (t1/2= 1 to 2 hours) is more than 2-fold longer than in HS-SY-II cells (t1/2 < 0.5 hours) (Figure 4D). siRNA-mediated downregulation of SYT-SSX1 expression in HS-SY-II cells increased PDGFRA protein stability with a longer half-life approximating that observed in SYO-1 cells (Figure 4D). Alternatively, no changes in PDGFRA protein stability were observed in SYO-1 cells with SYT-SSX2 downregulation. These data suggest that the SYT-SSX1 gene product can downregulate PDGFRA expression in synovial sarcoma cells via multiple mechanisms.

PDGFRA transcripts are highly overexpressed in synovial sarcomas relative to other sarcoma subtypes

To assess the clinical relevance of PDGFRA for synovial sarcoma, Affymetrix U133 arrays were used to quantify the transcript levels of kinase genes from five different sarcoma subtypes derived from 139 primary patient tumor specimens and 17 cell lines and xenografts: synovial sarcoma (46 patient cases and 2 cell lines), desmoplastic round cell tumor (28 patient cases, 2 xenografts, and 1 cell line), alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (23 patient cases), alveolar soft part sarcoma (14 patient cases and 2 xenografts), and Ewing sarcoma (28 cases and 10 cell lines). The 739 probe sets on the U133A chip corresponded to 432 genes with kinase domains, representing 83% of the 518 known protein kinase genes. (Note: this microarray expression analysis was utilized in a previous publication as a comparator data set for a study of myxoid chondrosarcoma (26)).

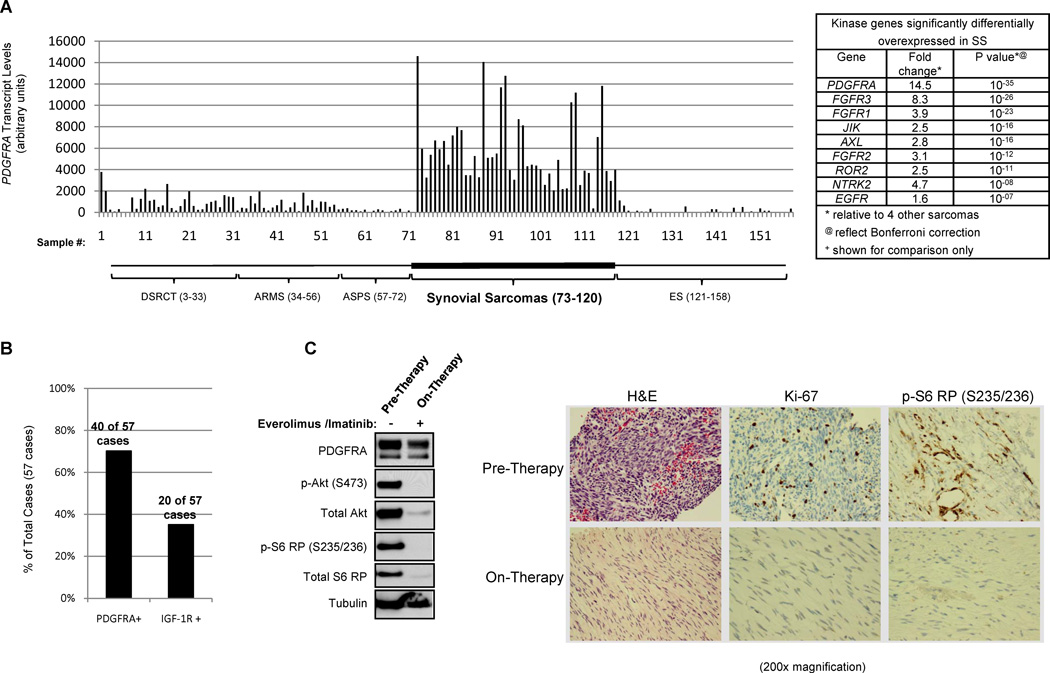

Amongst all the kinase genes evaluated in these 5 sarcoma subtypes, PDGFRA in synovial sarcomas was the most overexpressed: synovial sarcoma cases had 14.5 fold higher levels of PDGFRA than the other four tumor types (Figure 5A), representing the highest disparity in gene expression discovered in this analysis. In 25 synovial tumor cases and the two cell lines, no PDGFRA kinase (exons 12–16) or transmembrane (exons 18–21) domain mutations were found. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) performed on another set of 57 synovial sarcomas demonstrated that 70.2% (40 out of 57) of the tumors expressed PDGFRA protein, while only 35.1% (20 out of 57) were positive for IGF-1R (Figure 5B). This synovial sarcoma tissue analysis establishes that wild-type PDGFRA is uniquely, highly expressed in synovial sarcomas.

Figure 5.

High PDGFRA expression is unique to synovial sarcomas and can be targeted with imatinib in combination with everolimus to inhibit both Akt and mTORC1 substrate phosphorylation. A) PDGFRA transcript levels detected with Affymetrix U133A arrays. 139 sarcoma patient tumor samples and 17 cell lines and xenografts were analyzed. Samples 3–33 are desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT; 28 cases, 2 xenografts, and 1 cell line); samples 34–56 are alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas (ARMS; 23 cases), samples 57–72 are alveolar soft part sarcoma (ASPS; 14 cases and 2 xenografts); samples 73–120 are synovial sarcomas (46 cases and 2 cell lines); and samples 121–158 are Ewing sarcoma (28 cases and 10 cell lines). B) PDGFRA and IGF-1R protein in 57 synovial sarcoma cases were assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC). The graph represents the percentage of cases positive for each of these proteins. C) Western blot and IHC analysis of pre-therapy (within 2 weeks of the start of drug therapy) and on-therapy (between weeks 2 and 3 of drug therapy) tumor biopsies obtained from a patient treated with everolimus (5 mg daily) and imatinib (400 mg daily). Biopsies were obtained from a tumor located on the patient’s extremity. Lysates were created from frozen tissue biopsy samples and Western blot performed. IHC was performed on fixed tissues.

Preliminary clinical evidence of inhibiting Akt phosphorylation with imatinib in combination with mTORC1 inhibition

We are currently conducting a National Cancer Institute (NCI) phase Ib/II clinical trial testing the combination of the mTORC1 inhibitor everolimus (a rapamycin analogue, or “rapalogue”) and imatinib in patients with PDGFRA-positive, recurrent, metastatic synovial sarcoma (NCI# 8603) (trial registration ID: NCT01281865). Pre-therapy (within 2 weeks of starting drugs) and on-therapy (between the second and third week of treatment) tumor biopsies were performed on a patient who experienced a reduction in the size of lung metastases with everolimus (5 mg oral daily) and imatinib (400 mg oral daily) (Figure 5C). Western blot analysis with protein normalized by both tubulin and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) levels revealed a substantial loss of phosphorylated and total S6 RP and Akt with everolimus/imatinib therapy (Figure 5C). Immunohistochemistry of these same tissues revealed a corresponding loss of tumor cellularity, decreased Ki-67 staining, and loss of phosphorylated S6 RP in the tumor cells (Figure 5C). These data demonstrate that combined S6 RP and Akt inhibition can be achieved clinically with rapamycin and imatinib in synovial sarcoma.

DISCUSSION

The hypothesis that induction of IGF-1R-dependent Akt activation is a critical mechanism of intrinsic resistance to rapalogue therapy has led to the development of several early phase clinical trials evaluating combined mTORC1 and IGF-1R inhibition (31–34). Early results have suggested that this approach may have greater clinical efficacy than treatment with agents that inhibit mTORC1 or IGF-1R alone (33). Nonetheless, it is also apparent that IGF-1R inhibition will likely not be effective for reversing intrinsic rapamycin resistance in all sarcomas. A recent phase I study reported that 10 of 17 sarcoma patients treated with mTORC1 and IGF-1R inhibitors in combination still experienced increased tumor growth (34). Recent drug screens in xenograft mouse models have also suggested that this combinatorial approach may have limitations (16–18). The R1507 +/− rapamycin sarcoma cell line screen presented here confirms that IGF-1R inhibition will not be an universally effective approach for overcoming intrinsic rapalogue resistance.

The identification of IGF-1R-dependence and -independence in two synovial sarcoma cell lines provided the opportunity to study an alternate mechanism of intrinsic rapamycin resistance in tumor cells of a shared histology, driven by similar genetic alterations (the SYT-SSX fusion genes). Previous studies investigating IGF-1R targeting in synovial sarcoma cell lines with small molecule inhibitors produced conflicting conclusions regarding IGF-1R-dependence. One study argued that the IGF-1R kinase inhibitor NVP-AEW541 can inhibit the proliferation of several synovial sarcoma cell lines (35), while another observed that these anti-proliferative effects could only be achieved with micromolar NVP-AEW541 concentrations 10 to 50 fold higher than those required for IGF-1R inhibition (36), implicating off-target drug effects rather than IGF-1R-dependence. The impact of IGF-1R inhibition upon Akt phosphorylation has only been explored in the narrow biologic context of serum-starved cells exposed to purified IGF ligands (35, 37) rather than in the context of serum with multiple ligand-stimulated RTK pathways. Taking a more selective approach to receptor targeting with the monoclonal antibody R1507 and conducting these experiments in the presence of serum, we evaluated the contribution of IGF-1R and alternate RTK pathways to the induction of Akt phosphorylation following rapamycin exposure.

In SYO-1 cells, the inability to abrogate rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation with IGF-1R inhibition was not due to a lack of receptor expression since it was expressed at levels comparable to those in the IGF-1R-dependent cell line HS-SY-II. The phosphorylated RTK antibody arrays of serum exposed SYO-1 cells revealed a lack of phosphorylated IGF-1R, implying the receptor is not activated at baseline despite intact expression. Instead, we found that high PDGFRA expression mediates Akt phosphorylation in response to rapamycin in SYO-1 cells. Data from our expression microarray analysis demonstrated that PDGFRA is uniquely overexpressed in synovial sarcomas relative to other sarcoma subtypes (also indicated in a smaller study of 16 synovial sarcomas (38)), corresponding to a higher rate of PDGFRA protein IHC-positivity than IGF-1R in patient tissue samples (Figure 5B). Notably, high expression of a PDGFR pathway component has been demonstrated to be sufficient to drive oncogenesis in other sarcoma subtypes. The COL1A1-PDGFB fusion gene in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) results in PDGF BB ligand overexpression, hyperactivation of the PDGFR pathway, and susceptibility to imatinib (39). Recent studies have reported that high levels of phosphorylated PDGFRA in rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines correlated to susceptibility to PDGFRA inhibition achieved with sunitinib (40) and sorafenib (41). For synovial sarcoma, high PDGFRA is potentially sufficient for establishing it as the dominant RTK responsible for the induction of Akt phosphorylation in response to rapalogue treatment.

Importantly, the sarcoma microarray data presented here also revealed a degree of heterogeneity with regards to how highly abundant PDGFRA transcripts may be amongst synovial sarcomas (Figure 5A). In the synovial sarcoma cell lines, differences in PDGFRA expression translated to differences in PDGFRA dependence for rapamycin-induced Akt activation: resistance to PDGFRA targeting was observed in the lower PDGFRA-expressing HS-SY-II cells, while susceptibility to receptor targeting was found in the higher-PDGFRA-expressing SYO-1 cells. Furthermore, exogenous overexpression of PDGFRA in HS-SY-II cells conferred a new susceptibility to imatinib suppression of rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation (Figure 4A). A recently published phosphoproteomic analysis of sarcoma cell lines confirmed that baseline RTK activation and dependence can vary in different sarcomas (41), suggesting that the specific RTK responsible for mediating intrinsic rapamycin resistance may vary depending upon sarcoma histologic subtype or the genetic context. This phenomenon has also been observed in other cancers, for instance in pleural mesothelioma (42). Though PDGFRA does not play a role in rapamycin-induced Akt phosphorylation for HS-SY-II cells, the receptor still may contribute to pathway signaling in other contexts. PDGFRA knockdown alone in HS- SY-II did result in decreased S6 RP phosphorylation and increased Akt phosphorylation (Figure 3A), while PDGFRA overexpression resulted in the opposite changes (Figure 4A). These observations suggest that at baseline PDGFRA may regulate mTOR activity in these cells and manipulating receptor expression can trigger changes to feedback pathways leading to Akt.

What remains to be better defined is how RTK expression is differentially regulated amongst synovial sarcomas. We found that the specific SYT-SSX fusion type expressed by the tumor can differentially impact PDGFRA expression. The Type 1 fusion in HS-SY-II cells negatively regulates PDGFRA expression, while the Type 2 fusion in SYO-1 cells does not appear to regulate PDGFRA expression at all. The SYT-SSX gene fusions are generally thought to promote oncogenesis in synovial sarcomas by altering chromatin remodeling and dysregulating the expression of several target genes (43). The impact of the Type 1 fusion upon PDGFRA expression does not appear to be limited to regulating PDGFRA transcript abundance, which was only modestly altered by fusion gene downregulation, but also extended to regulating PDGFRA protein half-life. Whether fusion type can reliably predict meaningful differences in PDGFRA expression in synovial sarcomas is not clear. While a modest trend towards higher PDGFRA transcript levels in Type 2 over Type 1 fusions was observed in the microarray analysis (data not shown), without the ability to assess differences in PDGFRA post-transcriptional stability and/or reliably quantify PDGFRA protein levels in clinical samples, an adequate analysis of this question is not yet possible. In the ongoing phase II study evaluating the everolimus and imatinib combination in synovial sarcoma patients, clinical activity will be correlated back to fusion status to explore how fusion type may influence susceptibility to PDGFRA targeting.

As for the mechanism by which rapamycin activates PDGFRA, mTORC1 inhibition has been shown to increase PDGFR transcript levels in hepatocellular tumor cells (44) and in mTOR activated TSC1−/− or TSC2−/− mouse cells (45). In SYO-1 cells, rapamycin increased PDGFRA phosphorylation, but did not upregulate PDGFRA expression (Figures 2E). Furthermore, the molecular events required for PDGFRA activation appear to be different from those critical for rapamycin-induced IGF-1R activation: while rapamycin resulted in decreased phosphorylation of IRS-1 (“insulin receptor substrate-1”, an IGF-1R adaptor protein) (11) and decreased expression of Grb10 (“growth factor receptor-bound protein 10”, a negative regulator of IGF-1R) (46, 47) in HS-SY-II cells, these IGF-1R activating changes were not observed in SYO-1 cells (Supplementary Figure 3A). Differences in the baseline expression or response to rapamycin of these molecules also did not appear to correlate to classifications of IGF-1R dependency (Class I versus Class II) (Supplementary Figure 3B).

In summary, intrinsic resistance to rapalogue therapy mediated by the induction of Akt activation can occur through different mechanisms. In synovial sarcoma, uniquely high levels of PDGFRA expression can translate to the utilization of this RTK for rapalogue-induced Akt activation, providing a new disease-specific mode of resistance that may be exploited therapeutically.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Agnes Viale and staff of the Genomics Core Facility for performing expression microarray hybridizations, Dr. Adam Olshen for assistance with microarray data analysis., and the Bustany Fund for Synovial Sarcoma Research (to M.L.).

GRANT SUPPORT

Financial Support: (NIH) 1 R01 CA140331-01, P01 CA47179, and P50 CA140146

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Majumder PK, Febbo PG, Bikoff R, Berger R, Xue Q, McMahon LM, et al. mTOR inhibition reverses Akt-dependent prostate intraepithelial neoplasia through regulation of apoptotic and HIF-1-dependent pathways. Nat Med. 2004;10:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neshat MS, Mellinghoff IK, Tran C, Stiles B, Thomas G, Petersen R, et al. Enhanced sensitivity of PTEN-deficient tumors to inhibition of FRAP/mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10314–10319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171076798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podsypanina K, Lee RT, Politis C, Hennessy I, Crane A, Puc J, et al. An inhibitor of mTOR reduces neoplasia and normalizes p70/S6 kinase activity in Pten+/− mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10320–10325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171060098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hresko RC, Mueckler M. mTOR.RICTOR is the Ser473 kinase for Akt/protein kinase B in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40406–40416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alessi DR, Andjelkovic M, Caudwell B, Cron P, Morrice N, Cohen P, et al. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J. 1996;15:6541–6551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barretina J, Taylor BS, Banerji S, Ramos AH, Lagos-Quintana M, Decarolis PL, et al. Subtype-specific genomic alterations define new targets for soft-tissue sarcoma therapy. Nature genetics. 2010;42:715–721. doi: 10.1038/ng.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toretsky JA, Kalebic T, Blakesley V, LeRoith D, Helman LJ. The insulin-like growth factor-I receptor is required for EWS/FLI-1 transformation of fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30822–30827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chawla SP, Staddon AP, Baker LH, Schuetze SM, Tolcher AW, D'Amato GZ, et al. Phase II Study of the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Inhibitor Ridaforolimus in Patients With Advanced Bone and Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okuno S, Bailey H, Mahoney MR, Adkins D, Maples W, Fitch T, et al. A phase 2 study of temsirolimus (CCI-779) in patients with soft tissue sarcomas: a study of the Mayo phase 2 consortium (P2C) Cancer. 2011;117:3468–3475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y, Yan H, Frost P, Gera J, Lichtenstein A. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors activate the AKT kinase in multiple myeloma cells by up-regulating the insulin-like growth factor receptor/insulin receptor substrate-1/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase cascade. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1533–1540. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun SY, Rosenberg LM, Wang X, Zhou Z, Yue P, Fu H, et al. Activation of Akt and eIF4E survival pathways by rapamycin-mediated mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7052–7058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan X, Harkavy B, Shen N, Grohar P, Helman LJ. Rapamycin induces feedback activation of Akt signaling through an IGF-1R-dependent mechanism. Oncogene. 2007;26:1932–1940. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cloughesy TF, Yoshimoto K, Nghiemphu P, Brown K, Dang J, Zhu S, et al. Antitumor activity of rapamycin in a Phase I trial for patients with recurrent PTEN-deficient glioblastoma. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolb EA, Gorlick R, Maris JM, Keir ST, Morton CL, Wu J, et al. Combination testing (Stage 2) of the Anti-IGF-1 receptor antibody IMC-A12 with rapamycin by the pediatric preclinical testing program. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pbc.23157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolb EA, Kamara D, Zhang W, Lin J, Hingorani P, Baker L, et al. R1507, a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting IGF-1R, is effective alone and in combination with rapamycin in inhibiting growth of osteosarcoma xenografts. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2010;55:67–75. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurmasheva RT, Dudkin L, Billups C, Debelenko LV, Morton CL, Houghton PJ. The insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor-targeting antibody, CP-751,871, suppresses tumor-derived VEGF and synergizes with rapamycin in models of childhood sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7662–7671. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawai A, Naito N, Yoshida A, Morimoto Y, Ouchida M, Shimizu K, et al. Establishment and characterization of a biphasic synovial sarcoma cell line, SYO-1. Cancer Lett. 2004;204:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonobe H, Manabe Y, Furihata M, Iwata J, Oka T, Ohtsuki Y, et al. Establishment and characterization of a new human synovial sarcoma cell line, HS-SY-II. Lab Invest. 1992;67:498–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Ishiguro M, Ohjimi Y, Fujita C, Yanai F, et al. Establishment and characterization of a novel human desmoplastic small round cell tumor cell line, JN-DSRCT-1. Lab Invest. 2002;82:1175–1182. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000028059.92642.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ambrosini G, Cheema HS, Seelman S, Teed A, Sambol EB, Singer S, et al. Sorafenib inhibits growth and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in malignant peripheral nerve sheath cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:890–896. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saito T, Nagai M, Ladanyi M. SYT-SSX1 and SYT-SSX2 interfere with repression of E-cadherin by snail and slug: a potential mechanism for aberrant mesenchymal to epithelial transition in human synovial sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6919–6927. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ambrosini G, Seelman SL, Qin LX, Schwartz GK. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor flavopiridol potentiates the effects of topoisomerase I poisons by suppressing Rad51 expression in a p53-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2312–2320. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nair JS, Ho AL, Tse AN, Coward J, Cheema H, Ambrosini G, et al. Aurora B kinase regulates the postmitotic endoreduplication checkpoint via phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein at serine 780. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2218–2228. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filion C, Motoi T, Olshen AB, Lae M, Emnett RJ, Gutmann DH, et al. The EWSR1/NR4A3 fusion protein of extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma activates the PPARG nuclear receptor gene. The Journal of pathology. 2009;217:83–93. doi: 10.1002/path.2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hailey J, Maxwell E, Koukouras K, Bishop WR, Pachter JA, Wang Y. Neutralizing anti-insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 antibodies inhibit receptor function and induce receptor degradation in tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:1349–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao L, Yu Y, Darko I, Currier D, Mayeenuddin LH, Wan X, et al. Addiction to elevated insulin-like growth factor i receptor and initial modulation of the AKT pathway define the responsiveness of rhabdomyosarcoma to the targeting antibody. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8039–8048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crew AJ, Clark J, Fisher C, Gill S, Grimer R, Chand A, et al. Fusion of SYT to two genes, SSX1 and SSX2, encoding proteins with homology to the Kruppel-associated box in human synovial sarcoma. EMBO J. 1995;14:2333–2340. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawai A, Woodruff J, Healey JH, Brennan MF, Antonescu CR, Ladanyi M. SYT-SSX gene fusion as a determinant of morphology and prognosis in synovial sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:153–160. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Cosimo S, Bendell J, Cervantes-Ruiperez A, Roda D, Prudkin L, Stein M, et al. A phase I study of the oral mTOR inhibitor ridaforolimus (RIDA) in combination with the IGF-1R antibody dalotozumab (DALO) in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. ASCO Meeting Abtr. 2010;28 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naing A, Kurzrock R, Burger A, Gupta S, Lei X, Busaidy N, et al. Phase I trial of cixutumumab combined with temsirolimus in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6052–6060. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naing A, Lorusso P, Fu S, Hong DS, Anderson P, Benjamin RS, et al. Insulin Growth Factor-Receptor (IGF-1R) Antibody Cixutumumab Combined with the mTOR Inhibitor Temsirolimus in Patients with Refractory Ewing's Sarcoma Family Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quek R, Wang Q, Morgan JA, Shapiro GI, Butrynski JE, Ramaiya N, et al. Combination mTOR and IGF-1R inhibition: phase I trial of everolimus and figitumumab in patients with advanced sarcomas and other solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:871–879. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedrichs N, Kuchler J, Endl E, Koch A, Czerwitzki J, Wurst P, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor acts as a growth regulator in synovial sarcoma. The Journal of pathology. 2008;216:428–439. doi: 10.1002/path.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terry J, Lubieniecka JM, Kwan W, Liu S, Nielsen TO. Hsp90 inhibitor 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin prevents synovial sarcoma proliferation via apoptosis in in vitro models. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5631–5638. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tornkvist M, Natalishvili N, Xie Y, Girnita A, D'Arcy P, Brodin B, et al. Differential roles of SS18-SSX fusion gene and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in synovial sarcoma cell growth. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2008;368:793–800. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baird K, Davis S, Antonescu CR, Harper UL, Walker RL, Chen Y, et al. Gene expression profiling of human sarcomas: insights into sarcoma biology. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9226–9235. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rutkowski P, Van Glabbeke M, Rankin CJ, Ruka W, Rubin BP, Debiec-Rychter M, et al. Imatinib mesylate in advanced dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: pooled analysis of two phase II clinical trials. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:1772–1779. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDermott U, Ames RY, Iafrate AJ, Maheswaran S, Stubbs H, Greninger P, et al. Ligand-dependent platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-alpha activation sensitizes rare lung cancer and sarcoma cells to PDGFR kinase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3937–4946. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bai Y, Li J, Fang B, Edwards A, Zhang G, Bui M, et al. Phosphoproteomics identifies driver tyrosine kinases in sarcoma cell lines and tumors. Cancer Res. 2012 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brevet M, Shimizu S, Bott MJ, Shukla N, Zhou Q, Olshen AB, et al. Coactivation of receptor tyrosine kinases in malignant mesothelioma as a rationale for combination targeted therapy. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2011;6:864–874. doi: 10.1097/jto.0b013e318215a07d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ladanyi M. Fusions of the SYT and SSX genes in synovial sarcoma. Oncogene. 2001;20:5755–5762. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li QL, Gu FM, Wang Z, Jiang JH, Yao LQ, Tan CJ, et al. Activation of PI3K/AKT and MAPK Pathway through a PDGFRbeta-Dependent Feedback Loop Is Involved in Rapamycin Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PloS one. 2012;7:e33379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang H, Bajraszewski N, Wu E, Wang H, Moseman AP, Dabora SL, et al. PDGFRs are critical for PI3K/Akt activation and negatively regulated by mTOR. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:730–738. doi: 10.1172/JCI28984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsu PP, Kang SA, Rameseder J, Zhang Y, Ottina KA, Lim D, et al. The mTOR-regulated phosphoproteome reveals a mechanism of mTORC1-mediated inhibition of growth factor signaling. Science. 2011;332:1317–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.1199498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu Y, Yoon SO, Poulogiannis G, Yang Q, Ma XM, Villen J, et al. Phosphoproteomic analysis identifies Grb10 as an mTORC1 substrate that negatively regulates insulin signaling. Science. 2011;332:1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.1199484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.