Abstract

We characterized the mutational landscape of melanoma, the form of skin cancer with the highest mortality rate, by sequencing the exomes of 147 melanomas. Sun-exposed melanomas had markedly more ultraviolet (UV)-like C>T somatic mutations compared to sun-shielded acral, mucosal and uveal melanomas. Among the newly identified cancer genes was PPP6C, encoding a serine/threonine phosphatase, which harbored mutations that clustered in the active site in 12% of sun-exposed melanomas, exclusively in tumors with mutations in BRAF or NRAS. Notably, we identified a recurrent UV-signature, an activating mutation in RAC1 in 9.2% of sun-exposed melanomas. This activating mutation, the third most frequent in our cohort of sun-exposed melanoma after those of BRAF and NRAS, changes Pro29 to serine (RAC1P29S) in the highly conserved switch I domain. Crystal structures, and biochemical and functional studies of RAC1P29S showed that the alteration releases the conformational restraint conferred by the conserved proline, causes an increased binding of the protein to downstream effectors, and promotes melanocyte proliferation and migration. These findings raise the possibility that pharmacological inhibition of downstream effectors of RAC1 signaling could be of therapeutic benefit.

Identification of mutations in cancer cells that drive malignant transformation has opened the door to patient-tailored targeted therapies that improve overall survival. For example, inhibitors of activating mutations in BRAF, which are present in ~50% of cutaneous melano-mas1, can have substantial therapeutic benefit2–4. Attempts to inhibit NRAS, which is mutated in 15–20% of all tumor types5, have been less successful. Exome or whole-genome sequencing has been used to identify new mutations in melanomas, but to date, studies using these methods have been limited to 25 or fewer tumors6–9. To reveal the scope of melanoma mutations more comprehensively, we performed exome sequencing of 147 primary or metastatic melanomas (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The results identified previously unreported genes and pathways that have a role in melanoma pathogenesis, including effectors for a new gain-of-function mutation that may be amenable to targeted therapy.

RESULTS

Landscape of nonsynonymous somatic mutations

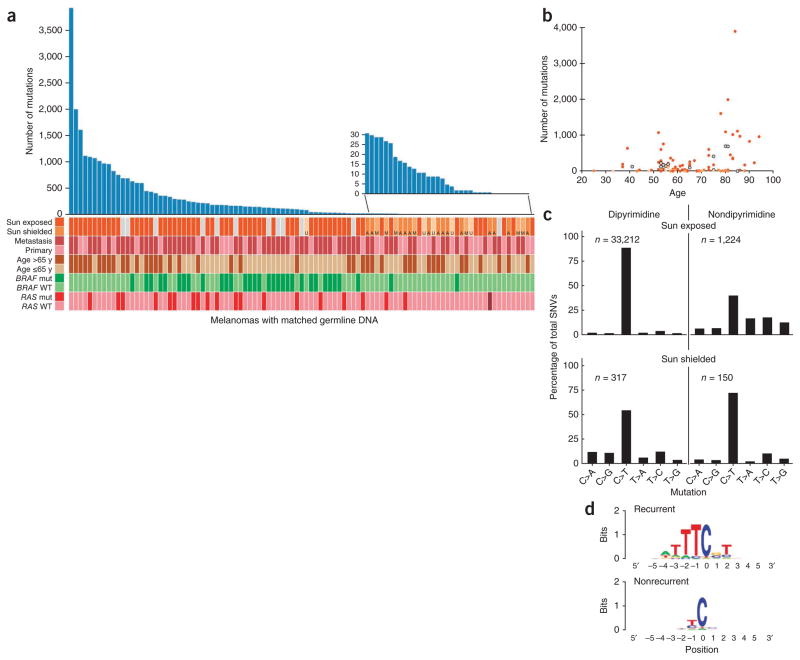

The analysis of protein-altering somatic mutations in 147 melanomas, based on comparison to matched germline DNA (referred to here as matched samples), revealed a total of 23,888 missense and 1,596 nonsense mutations, 399 splice-site variants and 282 insertions/deletions (indels). Melanomas originating from hair-bearing skin, such as the trunk, arms, legs or head (referred to here as sun-exposed melano-mas) had markedly more somatic mutations than melanomas originating from hairless skin such as palms and soles (acral melanoma), as well as mucosal and uveal melanomas (collectively referred to as sun-shielded melanomas), with a median count of 171 mutations per sun-exposed tumor and 9 mutations per sun-shielded tumor (P = 1.6 × 10−5). Melanomas with mutations in either BRAF or RAS were mostly in the center of the mutation load distribution, with a median of 156.5 mutations (Fig. 1a). Tumors with more than 500 somatic mutations were found in older patients (median age of 80.5 years compared to a median age of 65.0 years for the tumors with 500 or less mutations), with a high percentage of primary lesions in these patients on the head and neck (77%), which is a hallmark of chronic sun-damaged melanomas10. The number of mutations generally increased with patient age (Fig. 1b, Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.4, P = 0.0015). The tumors with wild-type BRAF and RAS with low mutation counts were primarily from sun-shielded sites.

Figure 1.

Mutation spectrum in melanoma samples. (a) Numbers of somatic nonsynonymous mutations across 99 matched melanoma samples. The tumors are represented as originating from sun-exposed skin (dark orange bars) or sun-shielded skin (acral (A), mucosal (M) or uveal (U), shown in different shades of light orange) or are melanomas of unknown origin (gray bars). Melanomas from primary compared to metastasis, the age of the patients and BRAF and RAS mutation status are also indicated. Mut, mutated; WT, wild type. NRAS is the most common RAS mutant gene, except for one acral melanoma that harbored the HRAS mutation resulting in p.Gln61His (brown). All BRAF and RAS mutations were validated by Sanger sequencing. The inset shows an expanded scale of the number of mutations in tumors at the lower range. (b) The number of mutations in relation to the age of the patients. (c) Spectrum of somatic variants in exomes of sun-exposed and sun-shielded (acral, mucosal and uveal) melanomas. There is an excess of C>T transitions in dipyrimidines in sun-exposed melanomas, which is an indication of UV exposure and DNA damage. The n values indicate the number of mutations; because any base has a 25% chance of being flanked by a purine on both sides, the frequency at which a mutated base is part of a dipyrimidine by chance is exactly threefold the frequency for nondipyrimidines. (d) Consensus sequence for positions with recurrent (at least three) and nonrecurrent mutations, as indicated. The recurrent mutations are located at a known hotspot sequence motif for cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer formation. The motif represents the actual prevalence of each sequence context without normalizing for the mammalian under-representation of CG dinucleotides.

The higher number of single-base mutations in sun-exposed melanomas was accounted for by mutations linked to UV-induced DNA damage, with an excess of C>T mutations in the dipyrimidines, including CC>TT, in both exonic and intronic sequences (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1a). There were 2.93-fold more C>T transitions in dipyrimidine sequences in the nontemplate compared to the template strand of expressed genes. The corresponding ratio of these transitions in nonexpressed genes was 0.96. These findings are consistent with transcription-coupled repair of mutations in the template strand of expressed genes6. We did not observe a higher number of C>T mutations in the dipyrimidine sequences in sun-shielded melanomas (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1a) or a significant difference in the C>T ratio for the nontranscribed compared to the transcribed strands in either expressed or nonexpressed genes in these tumors (1.19 and 0.91, respectively).

The extended sequence context had a large effect on mutation frequency in sun-exposed melanomas (Fig. 1d). For example, whereas the overall mutation frequency for a cytosine lying 3′ to thymidine was 5.53 × 10−5, the mutation frequency at the TTTCGT motif was 5.83 × 10−4 (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 3); this motif is a subset of the consensus hotspot sequence for creating cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers11.

Recurrent mutations

In addition to known recurrent mutations in BRAF and NRAS, we found a previously unidentified recurrent mutation in RAC1 (ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1), a C>T transition (CCT>TCT) resulting in a p.Pro29Ser substitution (Supplementary Fig. 1b; designated here RAC1P29S), in 7 of the 147 tumors. The next most frequent mutation resulted in a p.Arg630Glu substitution in DBC1 (deleted in bladder cancer 1), which we found in six melanomas. Twelve genes had four recurrences and 56 genes had three recurrences of the same missense mutation (Supplementary Table 4). There were 2.8-fold more recurrent nonsilent than silent mutations occurring in three or more melanomas (76 compared to 27, respectively), significantly more than expected based on a nonsynonymous to synonymous (NS:SN) ratio of 1.95 observed across all melanomas (P = 0.002). There were 1.97-fold more nonsilent mutations occurring in two or more melanomas, which was as expected based on the melanoma-wide NS:SN ratio (P = 0.75). Of note, no silent mutations recurred in more than five melanomas.

Genes with high mutation burden in sun-exposed melanomas

We rank ordered the genes for overall somatic mutation burden using an algorithm that incorporated the sequence context of the mutations, the gene expression status, gene-specific NS:SN ratios and mutation bias, as reflected by the silent mutation counts in each gene (Supplementary Note). Fifteen genes with Benjamini-Hochberg– corrected P values <0.05 were highly ranked for mutation burden in sun-exposed melanomas (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 5). The high load of mutations in DCC, and in particular, inactivating mutations, is unique for melanomas because this gene is commonly associated with low expression in cancer through loss of heterozygosity (LOH) or epi-genetic silencing but not with a high burden of damaging mutations12. Although we identified mutations in MAPK genes (Supplementary Table 6), none ranked high on our list, and none occurred in tumors derived from patients treated with vemurafenib or dabrafenib.

Table 1.

Expressed genes with significant overall mutation burden in sun-exposed melanoma

| Gene | Length (bp) | Number of samples with somatic SNVs | P | PBH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF | 2,290 | 28 | 6.65 × 10−47 | 3.48 × 10−43 |

| NRAS | 565 | 13 | 1.27 × 10−21 | 4.99 × 10−18 |

| DCC | 4,171 | 21 | 2.02 × 10−12 | 6.34 × 10−9 |

| TNC | 5,819 | 11 | 1.98 × 10−9 | 3.88 × 10−6 |

| TP53 | 1,112 | 9 | 5.04 × 10−8 | 8.80 × 10−5 |

| PTPRK | 4,118 | 12 | 1.37 × 10−7 | 2.16 × 10−4 |

| PPP6C | 928 | 8 | 1.61 × 10−7 | 2.17 × 10−4 |

| TLR4 | 1,802 | 8 | 1.65 × 10−7 | 2.17 × 10−4 |

| CD163L1 | 3,877 | 15 | 2.85 × 10−7 | 3.20 × 10−4 |

| GRM3 | 2,124 | 12 | 6.43 × 10−7 | 5.95 × 10−4 |

| NPAP1 | 2,248 | 13 | 1.37 × 10−5 | 7.44 × 10−3 |

| SLC15A2 | 2,186 | 11 | 1.67 × 10−5 | 8.19 × 10−3 |

| RAC1 | 607 | 6 | 3.12 × 10−5 | 1.26 × 10−2 |

| MAGEC1 | 2,245 | 8 | 4.29 × 10−5 | 1.69 × 10−2 |

| JAKMIP2 | 2,356 | 12 | 9.00 × 10−5 | 2.89 × 10−2 |

The numbers are based on samples of melanomas with matched germline DNA (n = 61). P indicates the uncorrected P value; PBH indicates the Benjamini-Hochberg–corrected P value. The length in bp corresponds to the number of bases in the exome capture region. The P values were derived from testing the observed somatic SNVs against an estimated tumor background mutation frequency.

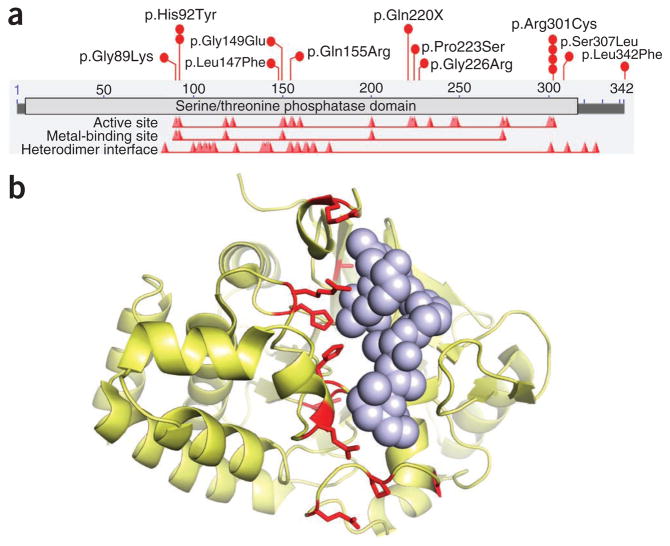

Several genes encoding protein phosphatases were on the list of genes with high mutation burden. The most unique among them is PPP6C (protein phosphatase 6, catalytic subunit), mutations of which affected 12.4% of sun-exposed tumors (Fig. 2), all of which also had BRAF or RAS mutations (P = 0.007; Fig. 3a); two of the alterations in PPP6C, p.His92Tyr and p.Arg301Cys, were recurrent (two and four times, respectively). The PPP6C mutations typically clustered in or near highly conserved positions in the catalytic site and the surrounding substrate recognition area (Fig. 2a, b). We infer that these are probable loss-of-function mutations, as they commonly occurred in the presence of LOH (in 6 of 12 tumors) (Fig. 3a, purple) or in tumors that simultaneously had two different point mutations (3 out of 12 tumors, one of which we confirmed to have trans mutations using targeted sequencing of the cloned complementary DNA (cDNA)). Notably, all the double-mutant tumors included the p.Arg301Cys alteration. Another protein phosphatase, PTPRK (protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, K), was altered in 19.7% of sun-exposed melanomas, with 17 different substitutions distributed throughout the coding region, including one missense mutation leading to early chain termination (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). A third protein phosphatase, encoded by PTPRD (protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, D), which has been reported to be mutated in other sequencing studies13,14, harbored 27 mutations in 17 tumors but ranked low on our list because of its size and high number of synonymous single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) (Supplementary Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of PPP6C alterations. (a) Map of PPP6C functional domains and the sites of amino acid substitutions. The horizontal bar shows the 342 amino acids of PPP6C (NP_001116827.1), the light gray bar shows the serine/threonine phosphatase domain, and the red peaks indicate the active site, the metal-binding sites and the heterodimer interface downloaded from NCBI. The red circles indicate the 11 mutations we discovered in the complete melanoma cohort and validated as somatic by Sanger sequencing. Recurrent mutations are indicated by multiple circles. (b) Mutant residues in PPP6C mapped onto the crystal structure of the phosphatase domain of PP2A (Protein Data Bank (PDB) 2IE4)56. All but one of the amino acids found to be mutated are conserved between PPP6C and PP2A. The PP2A structure is in complex with tumor-inducing okadaic acid, shown as solid spheres, which binds to the catalytic cleft. Mutations discovered in melanoma are shown in red. There is a clear preference for melanoma mutations to occur in the catalytic cleft of PPP6C.

Figure 3.

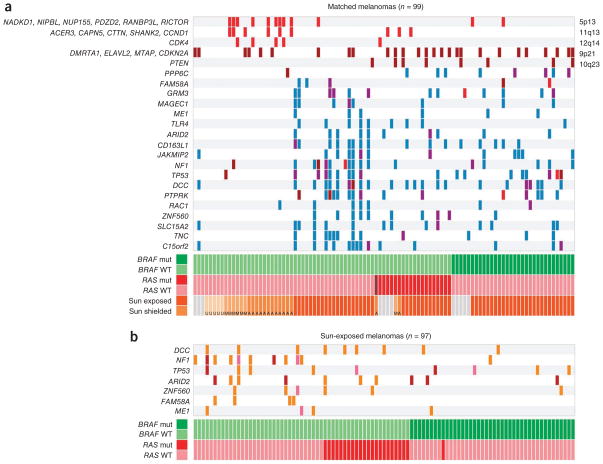

Distribution of SCNAs and genes with high mutation loads in melanomas. (a) A plot showing copy number aberrations and high somatic nonsynonymous mutation load. Red and brown indicate copy gain and loss, respectively, as related to chromosome band (right) and focal gene in the region (left). Mutations are marked in blue, and mutations occurring at LOH are shown in purple. At the bottom, the melanoma subtypes described in Figure 1a are indicated. (b) A plot of genes with a high load of somatic nonsense mutations. The bars indicate point mutations (orange), indels (pink) and splice-site variants (purple) that lead to frame shifts and early chain termination.

Seven expressed genes harbored nonsense mutations, including point mutations, splice-site variants and frame-shift indels, at higher rate than would be expected by chance (Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate of <0.05): DCC, TP53, NF1, ARID2, ZNF560, FAM58A and ME1 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 7).

Genes with high mutation load in sun-shielded melanomas

We found three previously unidentified somatic mutations in DYNC1I1 among 17 acral melanomas, all of which we validated by Sanger sequencing. Two DYNC1I1 mutations were identical and resulted in the p.Arg629Cys substitution. With a mean of only ten somatic mutations per acral melanoma, the likelihood of any mutation recurring in this set by chance is extremely low. An additional melanoma of unknown origin also harbored the somatic mutation in DYNC1I1 resulting in p.Arg629Cys (the DYNC1I1R629C mutation), further supporting its probable importance. DYNC1I1 encodes dynein, cytoplasmic 1, intermediate chain 1, a protein that is implicated in microtubule motor activity, progression through the spindle assembly checkpoint and possible normal chromosome segregation15.

Although the highly recurrent RAC1P29S mutation was not present in sun-shielded melanomas, we identified another mutation in RAC1, which resulted in the p.Asp65Asn substitution, in an acral melanoma that had a total of two somatic mutations. BAP1 has previously been reported to be frequently mutated in uveal melanomas16. We identified one new somatic homozygous frameshift mutation in BAP1, resulting in early termination, among six uveal melanomas. Other mutations that we identified in sun-shielded melanomas are listed in Supplementary Table 8.

Somatic copy-number alterations

We assessed somatic copy-number alterations (SCNAs) using differences in sequence coverage between all matched tumor and germline samples (sun exposed and sun shielded). The mean sequence coverage log ratios across the tumors showed large-scale genomic gains and losses in regions that were similar to those previously obtained by array comparative genome hybridization10 (Supplementary Fig. 3). These included copy number gains on chromosomes 1q, 6p, 7, 8q, 17q and 20q and losses on chromosomes 6q, 9p and 10. Chromosome 3 deletions in uveal melanomas, a frequent event in the metastatic state of the disease17, were also present. The CONTRA copy number program18 identified 23 genomic intervals with evidence of focal copy number gains or losses (Supplementary Table 9 and Supplementary Fig. 3b). Copy losses were in chromosomes 10q23 and 9p21, with strong deletion signals in PTEN and CDKN2A, respectively. Copy gains in chromosomes 5p13, 11q13 and 12q14 were predominantly found in mucosal and acral melanomas (Fig. 3), as has been previously reported10,17,19. We detected amplification signals in RICTOR on 5p13, CCND1 (11q13) and CDK4 (12q14) (Fig. 3). ASPM (asp (abnormal spindle) homolog, micro-cephaly associated (Drosophila)) on 1q31 showed amplification in 11 tumors, with 9 being metastases. ASPM has previously been reported in metastatic melanoma and has been shown to enhance invasion20. Notably, we also identified copy gain in 7q34 (BRAF), supporting prior reports of BRAF amplification in melanoma7.

Melanoma classification by mutations and SCNAs

Supervised clustering according to gene mutations and SCNAs revealed three major melanoma classes. One class, comprising sun-shielded melanomas with wild-type BRAF and NRAS, was characterized by a high number of copy gains and a low mutation load (Fig. 3a). In this group, the copy gains were on chromosomes 5p13 (RICTOR), 11q13 (CCND1) and 12q14 (CDK4). RICTOR encodes a protein that forms a complex with mTOR, suggesting that the amplification on 5p13 in this group contributes to the activation of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway independent of CDKN2A or PTEN copy loss. A second class comprised sun-exposed melanomas with wild-type BRAF and NRAS with few copy number alterations but a high load of mutations, which typically originated in older patients (Fig. 3a). Notably, 30% of the melanomas in this class (10 out of 33 samples) harbored deleterious mutations in NF1 (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, the frequent mutations in TP53, ARID2 and PTPRK in this group suggests that inactivation of tumor suppressors is a crucial step in the pathogenesis of BRAF- and NRAS-independent melanomas. Finally, a third class of melanomas comprised sun-exposed melanomas with mutations in BRAF or NRAS with frequent copy losses in PTEN and/or CDKN2A, copy gains and point mutations in several genes, including PPP6C (Fig. 3a), reinforcing the importance of additional mutations as potential modulators of MAPK-dependent melanoma tumor progression.

RAC1P29S mutations

We focused on RAC1 for further evaluation because it harbored a high rate of recurrent mutation with a strong UV signature (Supplementary Fig. 1b; the TTTCCT motif is mutated 155-fold more frequently in sun-exposed than non–sun-exposed melanomas) and is highly expressed in nonmalignant and malignant melanocytes21,22. In addition, mutations in RAC1 are likely to be biologically relevant because RAC1 is a member of the Rho family of small GTPases (which includes CDC42) that has important roles in the control of cell proliferation, cytoskeletal reorganization and cell migration. In addition, RAC1 effectors include various protein kinases, offering the opportunity for pharmacological inhibition.

We assessed the presence of the RAC1P29S mutation using Sanger sequencing of targeted PCR-amplified products in additional specimens collected by the Specimen Core of the Yale SPORE in Skin Cancer, resulting in a total set of 364 melanomas, including 217 sun-exposed tumors. The RAC1P29S mutation was present in 20 melanomas, all of which originated in the head, neck, limbs or upper trunk, comprising 9.2% of this type of lesion. An independent cohort of melanoma cell lines from Australia isolated from sun-exposed tumors revealed 4 out of 76 cell lines with RAC1P29S mutations (5.3%). There was a similar frequency of the RAC1P29S mutation in primary (9.2%) and metastatic tumors (8.6%), which is consistent with this mutation occurring early in tumorigenesis (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 10). RAC1P29S was significantly more prevalent in male patients (present in 12.8% of males compared to 2.4% of females, P = 0.01; Table 2), which is consistent with these mutations being induced by UV exposure, with melanoma risk increasing with UV exposure and with men having greater UV exposure23 (there were threefold more head and neck melanomas in the men than in the women in our cohort) (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b).

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of RAC1P29S in the Yale tumor cohort

| Category | Percentage with RAC1P29S | P |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 12.8 | 0.01 |

| Female | 2.4 | |

| Primary | 9.2 | 0.92 |

| Metastatic | 8.6 | |

| BRAF mutant | 7.4 | 0.76 |

| BRAF WT | 9.5 | |

| NRAS mutant | 6.3 | 0.77 |

| NRAS WT | 9.5 | |

| NRAS or BRAF mutant | 6.2 | 0.17 |

| NRAS and BRAF WT | 12.5 | |

| DCC mutant | 28.6 | 0.001 |

| DCC WT | 0 | |

| MAPK mutant | 26.3 | 0.009 |

| MAPK WT | 2.4 | |

| C15orf2 mutant | 30.7 | 0.015 |

| C15orf2 WT | 4 | |

| ZNF560 mutant | 37.5 | 0.03 |

| ZNF560 WT | 5.7 | |

| CD163L1 mutant | 26.7 | 0.03 |

| CD163L1 WT | 4.3 |

The male and female, primary and metastatic and BRAF and NRAS status numbers are based on available annotations for sun-exposed melanomas in the Yale cohort (n = 217). The other gene frequency numbers are based on a subset of 61 exome- sequenced sun-exposed melanomas having matched germline DNA. WT, wild type.

The RAC1P29S mutation was more frequent in melanomas that were wild type for both NRAS and BRAF (12.5% of melanomas with wild-type BRAF and NRAS had the mutation compared to 6.2% of melanomas with mutant BRAF or NRAS) (Table 2). Among the 61 sun-exposed samples with matched normal DNA, five of six samples with RAC1P29S also had a mutation in MAPK (P < 0.01; Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 5). RAC1P29S was also positively associated with three of the top mutated genes in sun-exposed melanoma, in particular with DCC, as well as with CD163L1, ZNF560 and C15orf2 (Table 2). RAC1P29S was not enriched in samples that harbored SNPs known to confer melanoma risk (Online Methods).

The RAC1P29S mutation was somatic in all cases for which matched normal DNA samples were available; RAC1P29S is absent from the dbSNP and 1000 Genomes databases and has not been found among 2,577 germline exomes sequenced at Yale or by direct sequencing of 2,596 individuals from 57 anthropologically defined populations originating from diverse parts of the world (Online Methods).

Structural analyses of RAC1P29S

Structural studies have shown that the switch I region of RAC1, which contains the p.Pro29Ser alteration, is a crucial regulatory element of the GTPase superfamily and is important for nucleotide binding and for interactions with effector molecules24,25. A proline residue corresponding to RAC1 Pro29 is completely conserved in the Rho family of GTPases (with the exception of divergent RhoBTB1 and RhoBTB2)24 (Supplementary Fig. 6) and is located at the N terminus of the switch I loop. Previous mutagenesis studies within the RAC1 switch I loop showed that mutation of the Pro29-Gly30 pair reduces the GTPase activity of RAC1 by 50% and results in increased effector activation26.

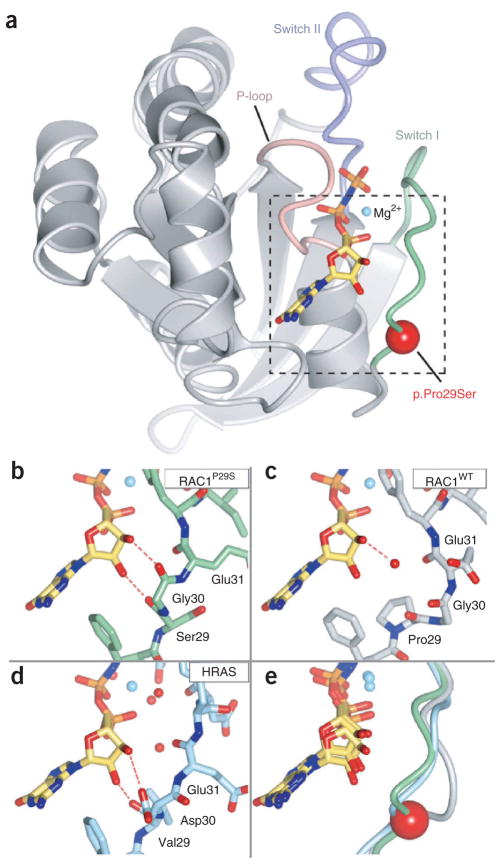

We determined two crystal structures of RAC1P29S in complex with the slowly hydrolyzing GTP analog GMP-PNP at 2.1-Å and 2.6-Å resolution and the crystal structure of wild-type RAC1 (RAC1WT) to 2.3-Å resolution (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 11 and Supplementary Fig. 7). Notably, the crystal structure of RAC1P29S is conformationally distinct from that usually observed in active-state Rho family GTPases and that of RAC1WT (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). In the RAC1P29S crystal structure, there are direct hydrogen bonds between the ribose hydroxyl groups of GMP-PNP and the backbone carbonyls of both Ser29 and Gly30. This bonding contrasts with the pattern typically observed for Rho family GTPases, where water-mediated hydrogen bonds form between the ribose hydroxyl groups and switch I residues24. Instead, the bonding seen in RAC1P29S closely aligns to the hydrogen bonding patterns observed in the crystal structure of activated HRAS, where direct interactions of ribose hydroxyl with the backbone are commonly present (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 7). The p.Pro29Ser alteration seems to release the conformational restraint inherent in a proline residue at position 29, therefore allowing a RAS-like altered conformation for GTP binding in the switch I loop and increased effector activation.

Figure 4.

Crystal structure of RAC1P29S. (a) Overall schematic of RAC1P29S showing the P-loop (pink), switch I (light green), switch II (purple), Mg2+ (cyan) and the slowly hydrolyzing GTP analog, GMP-PNP (stick format). The red sphere indicates the location of p.Pro29Ser. The dashed box indicates the regions shown in b–e. (b) Close-up view showing close contacts of ribose hydroxyls with the switch I region in RAC1P29S. (c) RAC1WT bound to GMP-PNP. (d) HRAS in complex with GMP-PNP (PDB 5P21)57. Direct hydrogen bonding between the switch I backbone and ribose are commonly observed in activated HRAS but are less frequently observed in Rho family GTPases, including RAC1. A RAS-like hydrogen bonding pattern is observed in activated RAC1P29S (dashed red lines). (e) Superposition of the switch I region and GMP-PNP. RAC1P29S is shown in light green, RAC1WT is shown in gray, and HRAS is shown in light blue. The red sphere indicates the location of p.Pro29Ser. The residues discussed in the text are labeled. The figure was made using CCP4mg58.

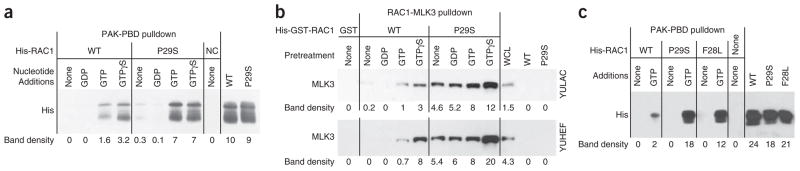

Analyses of RAC1P29S effector binding activity

RAC1 cycles between an inactive GDP-bound (GDP-RAC1) and an active GTP-bound (GTP-RAC1) form. Active RAC1 binds downstream effectors, leading to activation and membrane localization. This binding to RAC1 is mediated by the CRIB (Cdc42/Rac interactive binding) domain, which is present in several downstream effectors. We tested the binding activity of RAC1P29S and RAC1WT to two known effectors containing the CRIB domain: PAK1 (p21 protein activated kinase 1) and MLK3 (mixed-lineage kinase 3, official symbol MAP3K11). We used the canonical in vitro RAC1 activity assay (p21-binding domain (PBD) of PAK1 tagged to GST (GST-PAK1-PBD) and immobilized to beads) to test the binding activity of purified recombinant proteins. The binding assays showed more complex formation of pure RAC1P29S with PAK1-PBD compared to RAC1WT in the presence of GTP or slowly hydrolysable GTPγS (Fig. 5a). Using another in vitro approach, we observed more complex formation between cellularly expressed MLK3 protein kinase and GTP-RAC1P29S compared to GTP- RAC1WT (Fig. 5b). In addition, we also compared the PAK1-PBD complex formation of RAC1P29S to that of RAC1F28L, a spontaneously activated RAC1 with a p.Phe28Leu substitution, which possesses enhanced intrinsic GTP↔GDP exchange (rapidly cycling)27 (Fig. 5c). Quantization by scanning the bands with ImageJ showed that the binding activity of GTP-RAC1P29S with PAK1-PBD was similar to that of GTP-RAC1F28L, and that GTP-RAC1P29S was about 4.5-fold to ninefold more active than GTP-RAC1WT, depending on the gel analyzed (Fig. 5, gel density). These pulldown experiments showed that RAC1P29S is a gain-of-function mutation. Corroborating this conclusion are results from other studies showing that site-directed mutagenesis of the adjacent amino acid, resulting in p.Phe28Leu in RAC1, as well as in p.Phe28Leu in Cdc42 (Cdc42F28L) or p.Phe28Leu in Rho A (RhoAF30L), resulted in a constitutively activated GTPase and was able to transform NIH3T3 cells in culture or in nude mice27,28, highlighting the importance of this region to RAC1 activity.

Figure 5.

In vitro RAC1P29S binding to downstream effectors. (a) PAK1 pulldown assay showing that recombinant histidine-tagged RAC1P29S (His-RAC1P29S) has higher binding to its effector PAK1 compared to His-RAC1WT for samples that include GTP and GTPγS. NC, PAK1-PBD beads alone as a negative control. The His-RAC1WT and His-RACP29S lanes show unbound wild-type and mutant protein, as indicated. The multiple bands in all lanes are RAC1; all bands are observed when RAC1 crystals are run on SDS-PAGE. (b) RAC1 pulldown assay showing that recombinant His-GST-RAC1P29S has higher binding to endogenous MLK3 expressed in melanoma cells compared to His-GST-RAC1WT in all reaction samples. The immobilized recombinant RAC1 proteins were incubated with cell lysates from two independent melanomas (YULAC that is RAC1WT and BRAFV600K and YUHEF that is RAC1P29S and BRAFWT). The figure shows western blot of bound proteins with antibodies to MLK3. As negative controls, we used lysates incubated with GST-bound beads or recombinant RAC1 proteins that were not incubated with cell extracts. The western blot analysis also shows the expression of the relevant proteins in whole-cell lysate (WCL). The reaction mixtures were likely to contain nucleotides contributed by the cell lysates in addition to those added in vitro, as indicated. (c) PAK1 pulldown assay comparing the binding activity of RAC1WT, RAC1P29S and RAC1F28L proteins. The numbers under each lane indicate the band density as determined by scanning the membranes with ImageJ.

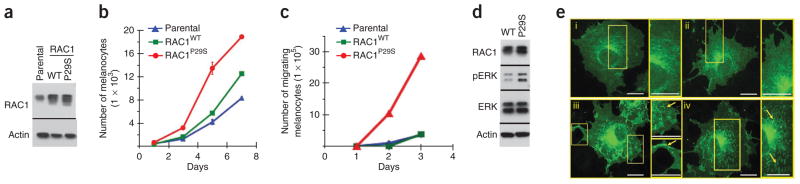

Functional analyses of RAC1P29S in normal and malignant cells

We then examined the cellular activity of RAC1P29S compared to RAC1WT in transiently transfected normal mouse melanocytes and COS-7 cells. Expression of RAC1P29S, but not RAC1WT, in normal melanocytes enhanced ERK phosphorylation, cell proliferation and migration (Fig. 6a–d). Furthermore, GFP-tagged RAC1P29S, but not RAC1WT, induced strong protein accumulation in the ruffling membranes of COS-7 cells (Fig. 6e), which is a hallmark of an activated RAC1 protein29. These findings confirm that the RAC1P29S mutation is a gain-of-function mutation, that it activates downstream signaling, and that it alters the phenotype of melanocytes and other cells.

Figure 6.

Cellular function of RAC1P29S compared to RAC1WT. (a) Western blot analysis of RAC1 in mouse melanocytes infected with wild-type (WT) or mutant RACP29S retroviral expression vectors compared to nontransfected cells (parental). Actin indicates protein loading in each lane. (b) RAC1P29S enhances melanocyte proliferation. The proliferation of melanocytes transiently expressing RAC1WT (green) or RAC1P29S (red) compared to noninfected parental cells (blue). Error bars indicate standard errors. (c) RAC1P29S enhances cell migration. The graphs show the rate of migration of parental, RAC1WT- and RAC1P29S-expressing melanocytes at daily intervals. (d) RAC1P29S enhances ERK activation. Western blots of lysates from mouse melanocytes expressing RAC1WT or RAC1P29S probed with RAC1, pERK, ERK and actin antibodies, as indicated on the side of the gel. (e) Localization of GFP-tagged RAC1WT (GFP-RAC1WT) and GFP-RAC1P29S in COS-7 cells. COS-7 cells transiently expressing GFP-RAC1WT (i, ii) or GFP-RAC1P29S (iii, iv) were fixed with paraformaldehyde and imaged with a spinning-disk confocal-based inverted Olympus microscope. Insets (yellow boxes) illustrate the localization of RAC1P29S, but not RAC1WT, in membrane ruffles (compare i and ii to the yellow arrows in iii and iv, respectively). pERK, phosphorylated ERK. Scale bars, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

Melanoma is known to be a highly heterogeneous disease with respect to histology, cytology, clinical behavior, chromosomal aberrations and mutation patterns19,30,31. Our sequencing of 147 melanoma exomes, the largest number of specimens analyzed so far by this approach, reinforces these observations and sheds new light on melanoma classification and the genetics of the malignant state. In general, we show three major melanoma classes, with high, medium and low mutation count, that are likely to belong to chronically exposed, intermittently sun-exposed and sun-shielded lesions, respectively. Our data reveal a mutation spectrum that is compatible with UV-induced damage in sun-exposed melanomas. The motif TTTCGT is enriched in a large portion of the sites that are mutated three or more times in sun-exposed melanomas. This motif is a known hotspot for creating cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and (6–4) photoproducts, as UV energy is absorbed by the A-T base pairs and transferred down the pyrimidine base stack to the cytosine of a G-C pair11,32. The resulting dipyrimidine photoproducts are usually repaired or correctly replicated, but the remainders are the principal lesions that lead to mutations in tumors after UV exposure33. We did not detect UV damage signature mutations in acral, mucosal or ocular melanomas. The spectrum of mutations located at dipyrimidine sequences in these lesions was indistinguishable from the spectrum of mutations at non-dipyrimidine sequences. This result is in agreement with data from one study9 but is in disagreement with those from another group34,35. The discrepancy between our results and those described in the latter publications might be due to differences in approaches because that study did not report two key elements of the UV signature: the percent of total mutations that were at a dipyrimidine and the percent of C>T transitions that were at a dipyrimidine. The investigators reported that 60% of all mutations in acral melanomas were C>T transitions, but this is at the low end for UV-induced mutations (typically 60–80%) and suggests that UV exposure might not be the only mutagen acting on this type of tumor.

The strength of our sequencing a large number of melanomas is in the discovery of new genes and pathways contributing to melanoma pathogenesis. For example, we identified ARID2 as a putative new tumor suppressor for melanomas. ARID2 is part of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex, suggesting that these types of mutations disrupt normal chromatin function and gene expression. ARID2 loss-of-function mutations were recently identified in hepatocellular carcinoma36.

The high mutation load in several protein phosphatases, including PTPRK, PTPRD and PPP6C, is likely to release constraints on downstream targets. For example, mutations in PTPRK, a TGF-β target gene37, may disrupt the growth-suppressive signaling of TGF-β in the affected tumors. The newly identified alterations in the serine/threonine phosphatase PPP6C are of particular interest because the amino acid substitutions clustered in the active site of the enzyme, are likely to be inactivating and occurred exclusively in tumors with activating mutations in BRAF or NRAS. The recurrent alteration p.Arg301Cys was recently also identified in 2, and the p.Ser307Leu alteration was identified in 1, of 25 metastatic melanomas9. About 80% of nevi harbor the BRAF mutation resulting in p.Val600Glu and, in some cases, a NRAS mutation at Gln61, yet nevi are typically associated with low proliferative activity and only infrequently progress to melanoma38,39. It is assumed that activating mutations in BRAF and NRAS initiate the proliferative process that is followed by senescence, termed oncogene-induced senescence. Loss of PTEN, a dual specificity protein tyrosine phosphatase, was until now considered the major mechanism for abrogating oncogene-induced senescence in either BRAF or NRAS mutant cells through activation of the PI3K-AKT signaling pathways40,41. Our data suggest a new cooperative pathway for transforming BRAF and NRAS mutant melanocytes. So far, PPP6C has not been demonstrated to be part of the MAPK or PI3K-AKT pathway but rather to have a crucial role in mitotic spindle and chromosome segregation42,43, as well as in the response to DNA strand breaks44. A known substrate of PPP6C is Aurora A, a serine/threonine kinase that controls spindle pole formation, centro-some maturation, chromosomal segregation and cytokinesis during mitosis42. As inactivation of PPP6C may lead to stimulation of the kinase activity of Aurora A, pharmacologic inhibition of Aurora A’s kinase activity might be considered. Indeed, a small-molecule inhibitor of Aurora A kinase has been already developed45, has shown a cytotoxic effect on several types of cancer cells, such as breast and glioma46,47, and is being considered for clinical application, especially in combination with other drugs48.

In the oncogene class, a key finding was the discovery of RAC1P29S as a recurrent UV-signature mutation in 9.2% of sun-exposed melano-mas. In our cohort, RAC1P29S was the third most frequent activating mutation after those of BRAF and NRAS. RAC1P29S was predominant in male patients known to have more outdoor exposure than females23. This gender difference was unique to RAC1P29S, and we did not find it for mutations in BRAF or NRAS. Whereas BRAF mutations are often in sites that are not chronically exposed to the sun, the specific types of melanoma that have a high frequency of NRAS mutations has not yet been determined1,19. RAC1P29S has increased binding to PAK1 and MLK3, provides a proliferative and migratory advantage to normal melanocytes through activation of ERK, and induces membrane ruffling. It was previously reported that MLK3 is capable of recruiting a BRAF-RAF1 complex49, suggesting that MLK3 may function as a link between RAC1 and the MAP kinase cascade.

Our gene association analysis showed that the RAC1P29S mutation in the matched melanomas was frequently associated with mutations in DCC, a gene that was recently validated as a tumor suppressor in mouse models50,51. DCC is the netrin 1 receptor that, in the presence of the ligand, mediates positive signals for proliferation, migration and differentiation through RAC1 and CDC42 and mediates apop-tosis in the absence of ligand12. It is possible that activating RAC1 mutations and loss of DCC cooperate in promoting the malignant process in a manner analogous to the combination of BRAF and NRAS mutations with loss of PTEN or PPP6C. The RAC1P29S mutation has been recently reported in 1 out of 74 squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck52, in 1 out of 26 esophageal cancers and 1 out of 44 pancreatic cancers53, suggesting a role for this mutation in other cancers as well.

The in vivo biological importance of RAC1 is supported by studies with mice showing that targeted deletion of Rac1 in melanoblasts causes defects in migration, cell-cycle progression and cytokine-sis54, and mice lacking Prex1, a Rac-specific Rho GTPase guanine nucleotide exchange factor, have defects in melanoblast migration during development and are resistant to metastasis when crossed to a mouse model of melanoma55. In our matched cohort of sun-exposed melanomas, PREX2 harbored 20 mutations in 13 samples, none of which overlapped with those in the published report9. However, this gene did not reach high priority here because it is not expressed in normal or malignant melanocytes, it had seven silent SNVs in seven samples and it is relatively large (4,889 bases in the capture region). Nonexpressed genes may harbor a large number of mutations based on empirical data on mutation load in expressed and nonexpressed genes6.

Gain-of-function mutations have proved to be productive therapeutic targets in a variety of cancers. Collectively, our findings suggest that inhibitors of direct effectors of RAC1, such as members of the PAK family of protein kinases, might be of therapeutic benefit in the treatment of melanomas.

URLs

BLAST, http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi; the full list of mutations is posted on MelaGrid, http://data.melagrid.org/en/dataset/exome-variants-in-melanoma.

ONLINE METHODS

Melanoma tumors and cell cultures

The melanoma tumors were from different patients and were excised to alleviate tumor burden. Specimens were collected with participants’ informed signed consent according to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations with a Human Investigative Committee protocol. The melanomas used for sequencing were from snap-frozen tumors or from short-term cultures59. Most of the melanoma cells were collected after 0–4 passages in culture, except for one sample called ‘YURIF’ that was collected after 14 passages in culture.

Exome capture, high-throughput sequencing and sequence validation

The DNeasy purification kit (QIAGEN) was used to extract genomic DNA from cell pellets and freshly frozen tumors. The OneStep PCR Inhibitor Removal Kit (Zymo Research Corporation) was used for samples with high melanin content. Whole exomes were enriched from genomic DNA by the solution-based SeqCap EZ Exome Library capture method following the manufacturer’s protocols (Roche/NimbleGen) at the Yale Center for Genome Analysis. Sequencing was performed with the Illumina Genome Analyzer (GA) IIx (56 tumor sample and 26 normal samples) and the Illumina HiSeq 2000 (91 tumor samples and 73 normal samples) as 75-bp paired-end reads following the manufacturer’s protocols. The exome capture area comprised 22,448,951 bases in the coding regions of 15,714 genes.

We validated the mutation data by Sanger sequencing of 300 gene-specific amplicons (primer pairs provided on request). The frequency of the recurrent RAC1P29S mutation was assessed using Sanger sequencing and the TaqMan assay (Applied Biosystems). A TaqMan assay to detect the RAC1P29S mutation was designed using the Applied Biosystems software on their website. Samples from 2,596 individuals from 57 anthropologically defined populations originating from diverse parts of the world60 were genotyped. Analyses were done in 384-well plates using the manufacturer’s protocol, except that volume was reduced to 3 μl. After 30 cycles, the plates were read on an AB 9600HD using SDS software.

In addition, another cohort of 76 melanoma cell lines in the Oncogenomics Laboratory, Queensland Institute of Medical Research was tested by Sanger sequencing using BigDye Terminator v3.1 chemistry on a 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The primers used are provided in Supplementary Table 12.

Gene expression

Whole-genome gene expression was derived from hybridization to NimbleGen human whole-genome microarrays, as described21,61. Genes with a median expression value of 550 and above were called ‘expressed’. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) was performed on two independent cultures of normal human melanocytes derived from newborn foreskins and adult skin. Final RNA-Seq libraries were sequenced at 75 bp per sequence using a GAIIx Illumina sequencer. Expression of a RefSeq transcript was determined by summing up all reads across the exons of the transcript. The transcript length-normalized and log-transformed value was used as the measure of gene expression. A two-component Gaussian mixture model was fit to the data, and a lower bound for expressed genes was chosen as two s.d. away from the higher distribution mean. For more details, see the Supplementary Note.

Reference genome and RefSeq database

We used the human reference genome GRCh37/hg19 for mapping exome-sequencing (Exome-Seq) and RNA-Seq data. The RefSeq sequence database downloaded from NCBI on 12 May 2011 was used as our gene model and for determining amino acid substitutions.

Exome-Seq processing

Read mapping and somatic calling

The following procedure was used to call melanoma sequence variations: reads were first trimmed based on their quality scores using the program BTrim62. The reads were then mapped against the reference genome using bwa63. SAMtools version 0.1.8–11 (r672)64 was used for PCR duplicate removal and SNV calling. Annotations of SNVs were performed with MU2A65. Annotation files were checked for adjacent pairs of SNVs affecting the same codon. If present, sequencing reads were scanned for the occurrence of both SNVs on a single allele, and the amino acid change was predicted based on the simultaneous mutations. SNVs were filtered according to the following quality criteria: (i) mutant allele frequency ≥13%; (ii) SAMtools mapping score ≥40; (iii) at least one forward and one backward read; (iv) a minimum coverage of four mutant and eight total reads at the variant position; and (v) uniform mapping of reads with the variant allele across the SNV locus. SNVs were further filtered based on their presence in repositories of common variations (dbSNP135 and 2,577 noncancer exomes sequenced at Yale). An SNV was called somatic in the absence of variant reads in the germline DNA samples, tolerating one mutant read in the normal samples, and expecting a sufficient variant to total read ratio in tumor and normal samples as assessed by Fisher’s exact test (P value threshold of 0.001).

We used SAMtools for indel calling, implementing strict selection criteria, including indel allele frequency >0.1, minimal SNP score of 250 in at least one melanoma and absence from repositories of common variations (dbSNP135 and 2,577 noncancer exomes sequenced at Yale). To identify somatic indels, we first excluded all indels that were also present in our normal samples and, in the absence of an indel call in the normal samples, we required a sequence coverage of at least eight independent reads at the corresponding position in the normal samples.

LOH calculation

To determine LOH in matched samples pairs, we followed a similar approach to that previously described66. We identified heterozygous positions in normal samples and used the R module ‘DNACopy’ to perform circular binary segmentation. The resulting regions were filtered for region-wide LOH.

Somatic copy number analysis

The sequence coverage log fold change was visualized in IGV67. We used the CONTRA copy number analysis program18 to determine SCNAs in the matched melanoma samples. The program was run with default parameters, excluding multimapped reads. We counted the number of samples for which at least one exon in a gene had a significant CONTRA call and fitted a Poisson distribution to the resulting sample counts per gene. Genes that had SCNA events in significantly more samples than expected were retained. We additionally required that these genes were located in chromosomal bands with significant CMDS calls, as previously described68,69.

Testing RAC1 for associations with melanoma risk SNPs, MAPK genes and genes with high mutation burden

We tested the melanoma risk SNPs rs1800401, rs1800407 (both in OCA2), rs16891982 (SLC45A2), rs1801516 (ATM) and rs1126809 (TYR), all of which are located in the exome capture area, for association with RAC1 mutations using the Fisher’s exact test. We proceeded similarly for assessing the association of RAC1 mutations with MAPK genes, as well as for genes with high mutation burden.

Cloning and analysis of double-mutant PPP6C in melanoma cells

Total RNA was extracted from YUGANK melanoma cells carrying the double PPP6C mutations resulting in p.Gln220X and p.Arg301Cys using an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was constructed using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase following the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). The region containing the p.Gln220X and p.Arg301Cys alterations was PCR amplified (Supplementary Table 12), and the 494-bp fragments were cloned into the pCR4-TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen). One Shot TOP10 (Invitrogen) competent Escherichia coli cells were transformed with the TOPO cloning reaction following the manufacturer’s instructions. Transformants were analyzed by colony PCR using M13 primers. PCR reactions were cleaned with ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix) and Sanger sequenced with T3 and T7 primers.

Site-directed mutagenesis and transient ectopic RAC1 expression

The pBabe-CyPet-RAC1 retroviral expression vector and the pcDNA3-eGFP-RAC1 plasmid were purchased from Addgene. The plasmids were constructed by K.M. Hahn70–72, who deposited them in Addgene for distribution. The CyPet tag is cleaved from RAC1 in mouse melanocytes, as observed before in neutrophils (K.M. Hahn, personal communication).

The p.Pro29Ser alteration was introduced in each of the plasmids with the QuikChange Kit (Stratagene). The alteration in the vector was validated by sequencing the plasmids. The primers used are provided in Supplementary Table 12.

Mouse melanocytes (from C57BL mice) at passage 19 were infected with retroviruses encoding pBabe-CyPet-RAC1WT or RAC1P29S. Puromycin (1 μg/ml) was added 2 d later, and the melanocytes were tested for cell proliferation and migration after 10 d of selection with the drug.

Fluorescence microscopy

COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with 1.5 μg pcDNA3-eGFP-RAC1WT and RAC1P29S constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After transfection, cells were plated in 24-well trays on Fisherbrand number 1.5 coverslips (12-545-81), and after 1 d of culture in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (PBS) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin, were washed, fixed with paraformalde-hyde (3.2%) and washed again, and coverslips were mounted onto microscope slides using ProLong Gold antifade mountant (Invitrogen, P36935). Cells were examined with a multicolor spinning-disk confocal UltraVIEW VoX system (PerkinElmer) based on an inverted Olympus microscope (1X-71) equipped with a 1 Kb × 1 Kb electromagnetic charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu Photonics) using a 60× 1.4 numerical aperture (NA) oil objective lens. The system was controlled by Velocity software.

Western blot analyses

Total cell extracts (16 μg protein per lane) with concentrations estimated with the Bio-Rad kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) were subjected to western blot analysis21. The membranes were probed with the mouse monoclonal antibody against recombinant full-length RAC1 protein (23A8, Millipore 05-389), monoclonal antibody to Erk1/2 phosphorylated at Thr202 and Tyr204 (Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), ERK1/2 (ERK1/2, 137F5) (both from Cell Signaling Technology) and monoclonal antibody to β-actin (A1978, Sigma-Aldrich). All antibodies were used at 1:1,000 dilution.

Cell proliferation and migration assays

Cell proliferation assays were performed in 6-well plates (~2,000 cells per well) in triplicate wells in OptiMEM supplemented with antibiotics and 7% horse serum in the presence of the required growth factor TPA (10 ng/ml, 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate, Sigma) and puromycin (1 μg/ml). The cells were harvested at 2-d intervals and counted with a Coulter counter.

Cell migration was measured with the Cultrex 24-Well Cell Migration Assay (Trevigen, 3465-024-K) following the manufacturer’s instructions and as described59.

RAC1WT and RAC1P29S expression and purification

RAC1P29S spanning residues 2–177 was subcloned into a modified pET-28 vector with a six- histidine N-terminal tag followed by GST and thrombin cleavage site. Recombinant RAC1P29S was expressed as an N-terminal fusion protein with glutathione-S-transferase (GST) in BL21(DE3) cells and induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 12 h at 30 °C. The fusion protein was affinity purified and cleaved by thrombin at 4 °C overnight. The protein was then loaded on a Superdex 200 HiLoad 16/60 (GE Healthcare) column in a buffer of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Purified mutant protein was finally concentrated to 3.5 mg/ml in a buffer of 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 5 mM MgCl2 with and without 1 mM GMP-PNP.

For RAC1WT, we subcloned residues 2–177 into a modified pET-28 vector with a six-histidine N-terminal tag. RAC1WT was expressed as an N-terminal fusion in BL21(DE3) cells and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 12 h at 30 °C. Briefly, RAC1WT was affinity purified and loaded on a Superdex 75 (GE Healthcare) column in a buffer of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT. Purified RAC1WT was finally concentrated to 7 mg/ml in a buffer of 20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM GMP-PNP.

RAC1P29S and RAC1WT crystallization

Crystals of RAC1P29S were grown by vapor-diffusion hanging drops formed by mixing a 1:1 volume ratio of purified RAC1P29S and reservoir solution containing 0.1 M 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1- piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.5), 20% (v/v) PEG 4,000 and 7% (v/v) isopropanol at room temperature. RAC1P29S crystals belong to space group P212121 with unit cell dimensions a = 50.3 Å, b = 80.0 Å, c = 94.9 Å and α, β, γ = 90°. There were two molecules per asymmetric unit. Crystals were equilibrated in a cryoprotectant buffer containing reservoir buffer plus 30% (v/v) ethylene glycol and were flash frozen in a nitrogen stream at 100 K. X-ray data from a single crystal were collected to 2.1-Å resolution at the Yale Chemical and Biophysical Instrumentation Center using a Rigaku HF007 generator and a Saturn 944+ CCD detector.

A second crystal form was determined to 2.6-Å resolution from identical crystallization conditions in the space group P22121 with unit cell dimensions a = 40.6 Å, b = 51.9 Å, c = 99.3 Å and α, β, γ = 90°. This crystal form has similar packing to the P212121 crystal and is conformationally similar (root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) values of 0.5 Å and 0.3 Å over 177 and 176 Cα atoms when compared to chains A and B, respectively), so we conducted our analyses using the P212121 crystal.

Crystals of RAC1WT were grown in almost identical conditions in the space group P21 with unit cell dimensions a = 40.9 Å, b = 97.9 Å, c = 51.7 Å and β = 96.6°. This crystal form has similar packing to both of the RAC1P29S crystals, allowing us to investigate whether the conformational changes observed for RAC1P29S were caused by crystal packing (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Structure determination and refinement

For the RAC1P29S P212121 crystal form, data were processed using the HKL2000 package73, and the initial phases were calculated by molecular replacement using the program Phaser74,75. Wild-type RAC1 (PDB 1MH1)75 was used as a search model and yielded translation Z-scores of 19.2 and 47.1 for the two molecules in the asymmetric unit. Automated model building with ARP/wARP76 built residues 2–176 in molecule A and residues 3–175 in molecule B, thus avoiding potential problems with model bias. Cycles of refinement and manual model building were conducted using REFMAC577 with a maximum-likelihood target, two TLS (Translation/Libration/Screw) groups per molecule and medium NCS (non-crystallographic symmetry) using COOT78. Model validation was conducted using MolProbity79. The final refined model of RAC1P29S had R and Rfree values of 24.0% and 28.5%, respectively (Supplementary Table 8). All of the residues fell within favored or allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot. Good electron density was observed throughout the structure, including for GMP-PNP and the switch I region (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). The structure is deposited in PDB under accession code 3SBD.

A similar processing, solution and refinement protocol was conducted for the 2.6-Å P22121 structure of RAC1P29S (Supplementary Table 10), and the data have been deposited in PDB under accession code 3SBE. Good electron density was observed throughout this structure, including for GMP-PNP and the switch I region.

A similar processing, solution and refinement protocol was conducted for the 2.3-Å P21 structure of RAC1WT (Supplementary Table 10), and the data have been deposited in PDB under accession code 3TH5. Good electron density was observed throughout this structure, including for GMP-PNP; however, the switch I regions of both molecules in the asymmetric unit were not well defined (Supplementary Fig. 8c). For molecule A, the switch I loop had poor electron density, and for molecule B, the switch I loop was not visible in the electron density. The crystal structure of RAC1WT has similar lattice interfaces as RAC1P29S, illustrating that the conformational differences observed in switch I are not the result of crystal packing effects.

Overall, the two RAC1WT molecules are globally similar to the RAC1P29S structures (molecule A has r.m.s.d. values of 0.44 Å, 0.31 Å and 0.34 Å over 173, 173 and 174 residues, respectively, when compared to the P212121 A, B and P22121 crystals; and molecule B has r.m.s.d. values of 0.39 Å, 0.35 Å and 0.43 Å over 170, 169 and 171 residues, respectively, when compared to the P212121 A, B and P22121 crystals).

RAC1 activity assays

Two independent approaches were used to assess the activity of RAC1P29S compared to RAC1WT. The traditional PAK1 pulldown assay (Millipore, RAC1 activation assay kit) was used with recombinant N-terminal His-tagged RAC1WT and RAC1P29S purified by affinity and size exclusion, as previously described80. The proteins were dialyzed for 12 h against buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 10 mM EDTA, followed by 2× dialysis for 12 h against the same buffer without EDTA to discharge innately bound nucleotides80. His-RAC1WT and His-RAC1P29S (6 μg) were incubated with 1 mM of nucleotide and GST-PAK1-PBD (GST fusion protein corresponding to residues 67–150 the p21-binding domain (PBD), of human PAK1 bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads) (5 μg) for 3 h at 4 °C in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 10 mM MgCl2. The beads were sedimented by centrifugation, the pellets were washed 3× with the same buffer, and the bound proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer at 95 °C and analyzed by western blot with polyhistidine antibody (HIS-1, H1029, Sigma-Aldrich) at 1:1,000- dilution. Incubations included no addition, GDP, GTP or GTPγS. NC (negative control) indicates GST-PAK1-PBD without any loaded RAC1 protein. One microgram of His-RAC1WT and His-RAC1P29S were included as controls. In addition, the ‘fast-cycling’ p.Phe28Leu alteration was introduced to His-RAC1WT by site-directed mutagenesis (Supplementary Table 12). We then tested the PAK1-PBD binding activity of His-RAC1WT, His-RAC1P29S and His-RAC1F28L purified proteins (1 μg of each) following the manufacturer’s procedure.

Alternatively, we performed RAC1 pulldown experiments to assess the binding of RAC1 to MLK3 in melanoma cell lysates. MLK3 contains a CRIB motif that interacts with a cloned construct of RAC1 in a two-hybrid system81. In these experiments, we used immobilized His-GST–tagged proteins captured to glutathione-Sepharose from bacteria lysates following the manufacturer’s instructions without further manipulations. The bead-bound slurries of His-GST-RAC1WT and His-GST-RAC1P29S were incubated with no addition, GDP, GTP or GTPγS in 20 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 10 mM MgCl2 for 3 h on ice. The beads were then washed 3× with lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, 1 mM EDTA and 1% NP40, plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors) and then incubated with YULAC (RAC1WT or BRAFV600E) and YUHEF (RAC1P29S or BRAFWT) melanoma cell lysates (500 μg per assay) overnight on a rotating wheel at 8 °C. The beads were washed 3× with lysis buffer, and the bound proteins were eluted with 2× SDS sample buffer and subjected to western blotting with mouse monoclonal antibodies to MLK3 (LS-C133912, LifeSpan BioSciences) at 1:1,000 dilution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Yale SPORE in Skin Cancer funded by the National Cancer Institute grant number 1 P50 CA121974 (principal investigator, R.H.), the Melanoma Research Alliance (a Team award to R.H., M.B., M.K. and D.F.S.), The National Library of Medicine Training grant 5T15LM007056 (P.E.), the Department of Dermatology (R.H.), Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center (M.K.), the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (N.K.H. and K.D.-R.), Gilead Sciences, Inc. (J.S., M.K., R.H. and T.J.B.) and a generous gift from Roz and Jerry Meyer (R.H., M.S. and H.M.K.). We thank C. Truini, W. Meng, B. Speed, E. Straka, A. Raefski, M. Scallion and S. Levin for technical support, P. Parsons, C. Schmidt and colleagues at the Queensland Institute of Medical Research for generously providing many of the melanoma cell lines, the Yale Center for Genome Analysis and the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team (NE-CAT) facility at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory.

Footnotes

Accession codes. Crystal structures are deposited in PDB with accession codesBD, 3SBE and 3TH5.

Note: Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.K., R.H., R.P.L., J.S. and T.J.B. designed and supervised the study. Y.K., P.E., M.C., J.P.M., S. Ma, G.G. and A.C. performed the bioinformatic analyses. A.B., E.C., E.C.H., M.J.D., K.D.-R., K.K.K., N.K.H. and S. Mane collected and analyzed the melanoma samples and performed the sequencing and functional experiments. B.H.H. and T.J.B. performed the crystallographic studies. S.A., D.N., M.B., M.S., H.M.K., M.A.M. and R.S.L. provided the clinical specimens and the clinical annotation. D.E.B. and D.F.S. analyzed sun-related mutations. All authors contributed to the final version of the paper.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

References

- 1.Bauer J, et al. BRAF mutations in cutaneous melanoma are independently associated with age, anatomic site of the primary tumor, and the degree of solar elastosis at the primary tumor site. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:345–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bollag G, et al. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature. 2010;467:596–599. doi: 10.1038/nature09454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman PB, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribas A, Flaherty KT. BRAF targeted therapy changes the treatment paradigm in melanoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:426–433. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jakob JA, et al. NRAS mutation status is an independent prognostic factor in metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 2011 Dec 16; doi: 10.1002/cncr.26724. published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pleasance ED, et al. A comprehensive catalogue of somatic mutations from a human cancer genome. Nature. 2010;463:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature08658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikolaev SI, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic MAP2K1 and MAP2K2 mutations in melanoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:133–139. doi: 10.1038/ng.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei X, et al. Exome sequencing identifies GRIN2A as frequently mutated in melanoma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:442–446. doi: 10.1038/ng.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger MF, et al. Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations. Nature. 2012;485:502–506. doi: 10.1038/nature11071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtin JA, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135–2147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brash DE, Haseltine WA. UV-induced mutation hotspots occur at DNA damage hotspots. Nature. 1982;298:189–192. doi: 10.1038/298189a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernet A, Fitamant J. Netrin-1 and its receptors in tumour growth promotion. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:995–1007. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.8.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon DA, et al. Mutational inactivation of PTPRD in glioblastoma multiforme and malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10300–10306. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stark MS, et al. Frequent somatic mutations in MAP3K5 and MAP3K9 in metastatic melanoma identified by exome sequencing. Nat Genet. 2012;44:165–169. doi: 10.1038/ng.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sivaram MV, Wadzinski TL, Redick SD, Manna T, Doxsey SJ. Dynein light intermediate chain 1 is required for progress through the spindle assembly checkpoint. EMBO J. 2009;28:902–914. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harbour JW, et al. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 2010;330:1410–1413. doi: 10.1126/science.1194472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onken MD, et al. Loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 3 detected with single nucleotide polymorphisms is superior to monosomy 3 for predicting metastasis in uveal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2923–2927. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, et al. CONTRA: copy number analysis for targeted resequencing. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1307–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiteman DC, Pavan WJ, Bastian BC. The melanomas: a synthesis of epidemiological, clinical, histopathological, genetic, and biological aspects, supporting distinct subtypes, causal pathways, and cells of origin. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:879–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabbarah O, et al. Integrative genome comparison of primary and metastatic melanomas. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koga Y, et al. Genome-wide screen of promoter methylation identifies novel markers in melanoma. Genome Res. 2009;19:1462–1470. doi: 10.1101/gr.091447.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halaban R, et al. Integrative analysis of epigenetic modulation in melanoma cell response to decitabine: clinical implications. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fears TR, et al. Average midrange ultraviolet radiation flux and time outdoors predict melanoma risk. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3992–3996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wennerberg K, Rossman KL, Der CJ. The Ras superfamily at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:843–846. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hakoshima T, Shimizu T, Maesaki R. Structural basis of the Rho GTPase signaling. J Biochem. 2003;134:327–331. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ménard L, Snyderman R. Role of phosphate-magnesium–binding regions in the high GTPase activity of rac1 protein. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13357–13361. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reinstein J, Schlichting I, Frech M, Goody RS, Wittinghofer A. p21 with a phenylalanine 28→leucine mutation reacts normally with the GTPase activating protein GAP but nevertheless has transforming properties. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17700–17706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin R, Cerione RA, Manor D. Specific contributions of the small GTPases Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 to Dbl transformation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23633–23641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ridley AJ, Paterson HF, Johnston CL, Diekmann D, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell. 1992;70:401–410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Broekaert SM, et al. Genetic and morphologic features for melanoma classification. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:763–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viros A, et al. Improving melanoma classification by integrating genetic and morphologic features. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crespo-Hernández CE, Cohen B, Kohler B. Base stacking controls excited-state dynamics in A.T DNA. Nature. 2005;436:1141–1144. doi: 10.1038/nature03933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziegler A, et al. Mutation hotspots due to sunlight in the p53 gene of nonmelanoma skin cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4216–4220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turajlic S, et al. Whole genome sequencing of matched primary and metastatic acral melanomas. Genome Res. 2012;22:196–207. doi: 10.1101/gr.125591.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furney SJ, et al. Genomic characterisation of acral melanoma cell lines. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25:488–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2012.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li M, et al. Inactivating mutations of the chromatin remodeling gene ARID2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:828–829. doi: 10.1038/ng.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flavell JR, et al. Down-regulation of the TGF-β target gene, PTPRK, by the Epstein-Barr virus encoded EBNA1 contributes to the growth and survival of Hodgkin lymphoma cells. Blood. 2008;111:292–301. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-059881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pollock PM, et al. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat Genet. 2003;33:19–20. doi: 10.1038/ng1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauer J, Curtin JA, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Congenital melanocytic nevi frequently harbor NRAS mutations but no BRAF mutations. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:179–182. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vredeveld LC, et al. Abrogation of BRAFV600E-induced senescence by PI3K pathway activation contributes to melanomagenesis. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1055–1069. doi: 10.1101/gad.187252.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nogueira C, et al. Cooperative interactions of PTEN deficiency and RAS activation in melanoma metastasis. Oncogene. 2010;29:6222–6232. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeng K, Bastos RN, Barr FA, Gruneberg U. Protein phosphatase 6 regulates mitotic spindle formation by controlling the T-loop phosphorylation state of Aurora A bound to its activator TPX2. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1315–1332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201008106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barr FA, Elliott PR, Gruneberg U. Protein phosphatases and the regulation of mitosis. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:2323–2334. doi: 10.1242/jcs.087106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Douglas P, et al. Protein phosphatase 6 interacts with the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit and dephosphorylates γ-H2AX. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1368–1381. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00741-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manfredi MG, et al. Characterization of Alisertib (MLN8237), an investigational small-molecule inhibitor of aurora A kinase using novel in vivo pharmacodynamic assays. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7614–7624. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sehdev V, et al. The Aurora kinase A inhibitor MLN8237 enhances cisplatin-induced cell death in esophageal adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:763–774. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jensen JS, Omarsdottir S, Thorsteinsdottir JB, Ogmundsdottir HM, Olafsdottir ES. Synergistic cytotoxic effect of the microtubule inhibitor marchantin a from marchantia polymorpha and the Aurora kinase inhibitor MLN8237 on breast cancer cells in vitro. Planta Med. 2012;78:448–454. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Macarulla T, et al. Phase I study of the selective Aurora A kinase inhibitor MLN8054 in patients with advanced solid tumors: safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2844–2852. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chadee DN, et al. Mixed-lineage kinase 3 regulates B-Raf through maintenance of the B-Raf/Raf-1 complex and inhibition by the NF2 tumor suppressor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4463–4468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510651103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castets M, et al. DCC constrains tumour progression via its dependence receptor activity. Nature. 2012;482:534–537. doi: 10.1038/nature10708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krimpenfort P, et al. Deleted in colorectal carcinoma suppresses metastasis in p53-deficient mammary tumours. Nature. 2012;482:538–541. doi: 10.1038/nature10790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stransky N, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barretina J, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607. doi: 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li A, et al. Rac1 drives melanoblast organization during mouse development by orchestrating pseudopod-driven motility and cell-cycle progression. Dev Cell. 2011;21:722–734. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lindsay CR, et al. P-Rex1 is required for efficient melanoblast migration and melanoma metastasis. Nat Commun. 2011;2:555. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xing Y, et al. Structure of protein phosphatase 2A core enzyme bound to tumor-inducing toxins. Cell. 2006;127:341–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pai EF, et al. Refined crystal structure of the triphosphate conformation of H-ras p21 at 1.35 A resolution: implications for the mechanism of GTP hydrolysis. EMBO J. 1990;9:2351–2359. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Potterton L, et al. Developments in the CCP4 molecular-graphics project. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2288–2294. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halaban R, et al. PLX4032, a selective BRAF(V600E) kinase inhibitor, activates the ERK pathway and enhances cell migration and proliferation of BRAF(WT) melanoma cells. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00685.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Donnelly MP, et al. The distribution and most recent common ancestor of the 17q21 inversion in humans. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tworkoski K, et al. Phosphoproteomic screen identifies potential therapeutic targets in melanoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:801–812. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kong Y. Btrim: A fast, lightweight adapter and quality trimming program for next-generation sequencing technologies. Genomics. 2011;98:152–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garla V, Kong Y, Szpakowski S, Krauthammer M. MU2A—reconciling the genome and transcriptome to determine the effects of base substitutions. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:416–418. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sathirapongsasuti JF, et al. Exome sequencing-based copy-number variation and loss of heterozygosity detection: ExomeCNV. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2648–2654. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2012 Apr 19; doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koboldt DC, et al. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2012;22:568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Q, et al. CMDS: a population-based method for identifying recurrent DNA copy number aberrations in cancer from high-resolution data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:464–469. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang X, He L, Wu YI, Hahn KM, Montell DJ. Light-mediated activation reveals a key role for Rac in collective guidance of cell movement in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:591–597. doi: 10.1038/ncb2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu YI, et al. A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature. 2009;461:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Machacek M, et al. Coordination of Rho GTPase activities during cell protrusion. Nature. 2009;461:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature08242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Otwinowski Z, Minor W, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 276. Academic Press; New York: 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode; pp. 307–326. Ch. 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast translation functions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:458–464. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hirshberg M, Stockley RW, Dodson G, Webb MR. The crystal structure of human rac1, a member of the rho-family complexed with a GTP analogue. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:147–152. doi: 10.1038/nsb0297-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Perrakis A, Harkiolaki M, Wilson KS, Lamzin VS. ARP/wARP and molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:1445–1450. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901014007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]