Abstract

Context

The Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA) and the FDA Amendment Act of 2007 (FDAAA), respectively, established mandates for registration of interventional human research studies on the website clinicaltrials.gov (CTG) and for posting of results of completed studies.

Objective

To characterise, contrast and explain rates of compliance with ontime registration of new studies and posting of results for completed studies on CTG.

Design

Statistical analysis of publically available data downloaded from the CTG website.

Participants

US studies registered on CTG since 1 November 1999, the date when the CTG website became operational, through 24 June 2011, the date the data set was downloaded for analysis.

Main outcome measures

Ontime registration (within 21 days of study start); average delay from study start to registration; proportion of studies posting their results from within the group of studies listed as completed on CTG.

Results

As of 24 June 2011, CTG contained 54 890 studies registered in the USA. Prior to 2005, an estimated 80% of US studies were not being registered. Among registered studies, only 55.7% registered within the 21-day reporting window. The average delay on CTG was 322 days. Between 28 September 2007 and June 23 2010, 28% of intervention studies at Phase II or beyond posted their study results on CTG, compared with 8.4% for studies without industry funding (RR 4.2, 95% CI 3.7 to 4.8). Factors associated with posting of results included exclusively paediatric studies (adjusted OR (AOR) 2.9, 95% CI 2.1 to 4.0), and later phase clinical trials (relative to Phase II studies, AOR for Phase III was 3.4, 95% CI 2.8 to 4.1; AOR for Phase IV was 6.0, 95% CI 4.8 to 7.6).

Conclusions

Non-compliance with FDAMA and FDAAA appears to be very common, although compliance is higher for studies sponsored by industry. Further oversight may be required to improve compliance.

Article summary.

Article focus

Since 1997, clinical trials in the USA involving ‘serious or life-threatening conditions’ are required to register on the website Clinicaltrials.gov within 21 days of study start.

Since 2007, interventional, Phase II–IV studies governed under an IND application were also required to post basic results on the website.

Key messages

Prior to 2004, the majority of studies were not being registered at all.

Overall, registration of studies occurs long after study start.

Approximately 75% of studies that appear required to post results do not do so.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This analysis includes over 54 000 studies registered in the USA, and thus provides considerable insight into registration practices and how these are affected by statutory actions.

The analysis may somewhat overestimate non-compliance rates, since not all studies that register on Clinicaltrials.gov are required to do so.

Introduction

The Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA) required the National Institutes of Health to establish a clinical trials registry to track efficacy studies involving human subjects. This resulted in the Clinicaltrials.gov (CTG) website, launched in November 1999.1 FDAMA requires that all studies for ‘serious or life-threatening conditions’ register on CTG. This applies to all Federally and industry-sponsored studies conducted in the USA and to studies conducted abroad if under the jurisdiction of an Investigational New Drug (IND) application. In 2002, FDA issued a binding guidance document listing CTG's four required elements: (1) a description of the study and experimental treatment; (2) recruitment information (eligibility and study enrolment status); (3) location and contact information; and (4) administrative data (protocol ID numbers and sponsor).2 The guidance also established timelines for registration (within 21 days of study start).

Subsequently, the FDA Amendment Act of 2007 (FDAAA) established an additional mandate that certain categories of industry-sponsored studies post basic trial results on CTG within 1 year of trial completion.3 This requirement applied to studies which (1) include subjects enrolled from at least one US site; (2) intervention studies at Phase II or beyond; (3) governed under an IND application; and (4) were initiated or ongoing as of 27 September 2007.4 In 2008, the CTG website was updated to include a templated interface for uploading basic trial results.4 5

The impetus for the CTG national trials registry rested on two key factors. First was patient equity: patient advocacy groups had long lobbied for a registry to help patients gain access to up-to-date information about potentially life-saving therapies and have the opportunity to enrol in relevant trials. From an ethical perspective, registration of studies is consistent with the Belmont Report's three core principles: respect for individuals; beneficence; and justice.6

Second, CTG was intended to combat publication bias. In the early 2000s, public trust in the medical literature was severely damaged when it emerged that data had been suppressed regarding an apparent increase in suicides among adolescents taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors7 and of severe cardiovascular events in patients taking the Cox-2 inhibitor rofecoxib.8 A recent meta-analysis of several candidate antidepressants provided a quantified example of publication bias. This analysis assessed 74 clinical studies, all of which had been registered with the FDA under IND, and therefore comprised a complete set of studies on these drugs. Of the 38 ‘positive studies’, 37 were published. In contrast, of the 36 studies judged ‘negative’ by the FDA, only 3 were published as such, whereas 11 were published so as to imply a positive result and the remaining 22 were never published at all.9 In response to such events, in 2004 the International Committee of Medical Journal editors (ICMJE) issued a policy declaring trial registration as a precondition for publication of efficacy studies.10

Yet 13 years after the CTG website has been launched, little is known about patterns of utilisation for efficacy studies conducted in the USA, nor to what degree study sponsors are compliant with the deadlines for trial registration and posting of results. To better understand these issues, I analysed the CTG database itself, which is freely available for download from the CTG website.

Methods

After limiting the data set to studies for which the ‘Location’ tab was the USA (selecting ‘Country 1’=‘United States’), I downloaded the CTG dataset on 24 June 2011 from http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/search/advanced. The data were exported as an XML file, which I then imported into SPSS V. 19 for further analysis.

My analysis focused on the following three questions:

‘What was the pattern of trial registrations over time, and how did this relate external events intended to promote compliance with the mandates?’

‘What proportion of studies were registered on time?’

‘Among relevant studies (as defined below), what proportion posted their results on CTG within 1 year of study completion?’

For the analysis of study registrations, I defined a trial as registered on time if its start date was ≤21 days before the CTG registration date (ie, within FDAMA's compliance window). For the analysis of study result postings, I defined compliance more narrowly to fit with the limits set by FDAAA. Accordingly, I limited the analysis set to interventional studies at Phase II or beyond for which industry was the sole sponsor, since these should be governed under IND. I then narrowed the set to a relevant window of time. On the front end, I included studies that listed their completion date as 28 September 2007 or beyond, reasoning that if the completion date was on or after the 28th, then the study must have been ongoing as of the 27th. Since studies were required to post results within 1 year of the completion date, I limited the set to studies that were listed as complete as of 23 June 2010, that is, 1 full year prior to the date when I downloaded the data set for analysis. In this way, only trials that had a complete year in which to post their results were included. As a spot check to the fidelity of these limits, I manually inspected the study descriptions of the first 200 studies retrieved and found that all were interventional, industry sponsored, US-based studies at Phase II or beyond.

I defined a ‘completed study’ as one for which a valid completion date had been entered on CTG, either under the field ‘Completion Date’, or when this field was left blank, the ‘Primary endpoint completion date’. The average time from registration to start dates was calculated as the difference between the CTG registration and study start dates. The average study duration was calculated from study start and study completion dates. Funding sources were classified as ‘Industry only’, ‘Non-industry only’ and ‘Blended funding’, indicating a mixture of industry and non-industry funds. Studies were categorised by the phase of development (Phases I–IV). For studies that were listed ambiguously as Phase I/Phase II, I classified them as Phase II; for studies that were listed ambiguously as Phase II/III, I classified them as Phase III. Study subject composition was categorised as ‘Males ’, ‘Females’ or ‘Males and Females’; ages were categorised as ‘Adults’ (including seniors), ‘Children’ or ‘All ages combined’.

In bivariate analyses I calculated relative risks and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) where appropriate. I stratified results by source of funding and calendar years. For the analysis of results postings, I included industry- and non-industry-sponsored studies with a completion date on or after 28 September 2007. To create an indexed interpretation of posting rates, I divided the number of results posted by the number of studies completed during the same period, recognising that these would not necessarily be the same studies.

To identify factors related to on-time registrations of posting of results, I used logistic regression models to generate adjusted OR (AOR). The regression models were built by selecting variables for inclusion in the models that either showed significant relationships in bivariate analyses, or which I felt a priori should be included (sex, age groups). The final models included the following variables: study phase; year of registration; sexes included; age groups included; and source of funding. In the multivariate analysis for posting of results, I limited the analysis set to completed, industry-sponsored studies, at Phase II or beyond, which occurred within the period 28 September 2007 through 23 June 2010.

Results

US studies registered on CTG

As of 24 June 2011, 54 890 US studies had been registered on CTG and were included in this analysis (table 1). Most studies recruited subjects of both sexes. Exclusively paediatric studies comprised 5.4% of the total. Later stage (Phase II and beyond) accounted for 77% of the studies that provided this information. Roughly one-third of studies were sponsored by industry. Among the 46 888 ‘completed’ studies, the average study duration was 1222 days (SD 1085 days). This varied significantly by funding source: 783 days (SD 732 days) for industry studies versus 1454 days (SD 1199 days) for non-industry studies versus 1178 days (SD 879 days) for studies with blended funding (ANOVA, 2df, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies registered on the Clinicaltrials.gov website1

| Study characteristic | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total studies registered in the USA | 54890 | 100 |

| Sex of study subjects | ||

| Females only | 5314 | 9.7 |

| Males only | 2170 | 4.0 |

| Both sexes combined | 47355 | 86.3 |

| Not indicated | 51 | <0.1 |

| Age of study subjects | ||

| Adults (including seniors) | 42283 | 77.0 |

| Children | 2952 | 5.4 |

| Both adults and children | 9646 | 17.6 |

| Not indicated | 9 | <0.1 |

| Study phase | ||

| Phase I | 8145 | 14.8 |

| Phase II | 15911 | 29.0 |

| Phase III | 8142 | 14.8 |

| Phase IV | 4292 | 7.8 |

| Phase not indicated | 18400 | 33.5 |

| Source of funding | ||

| Industry | 15903 | 29.0 |

| Non-industry* | 32499 | 59.2 |

| Blended (industry plus non-industry) | 6477 | 11.8 |

| Source of funding not indicated | 11 | <0.1 |

1CTG began accepting trial registrations on 1 November 1999.

- 6480 trials for which NIH was the sole sponsor;

- 1227 trials sponsored by another US Federal agency;

- 10 166 trials with multiple non-industry sources of funding (including NIH); and

- 14 626 trials for which the funding source was listed as ‘other’ or was not listed.

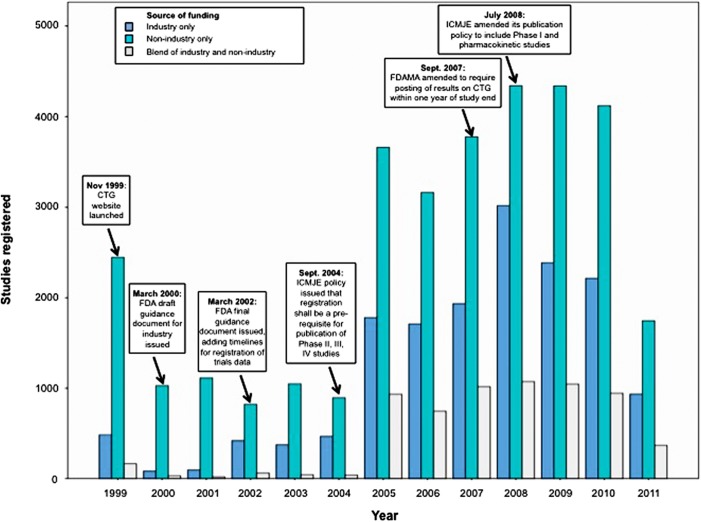

Figure 1 summarises the numbers of registrations by year across the three funding categories. The overall number of registrations in 1999 far exceeded those during each of the years 2000–2004. This is likely an artefact created by the backlog of ongoing trials that were registered en masse with the launch of the CTG website.

Figure 1.

Studies registered on Clinicaltrials.gov, by year and funding source.

In 2002, the number of industry-sponsored trial registrations increased from 83 and 95 per year in 2000 and 2001, respectively, to between 373 and 466 in the years 2002–2004. This change appears to coincide with when FDA posted its final guidance document for the use of CTG in 2002, mandating a timeline for compliance with registration.

Between the years 2004–2005 there was a very large increase in the number of new studies being registered. Of note, 2004 was the year that the ICMJE issued its policy that journals should not publish any study that had not been registered. This event created a natural experiment by which to estimate the extent of ‘non-registration’ in the period 2000–2004. By calculating the average number of trials registered/year from 2000–2004, and the average number of registrations per year from 2005–2010 (I excluded 2011 from this calculation since it only included half a year of data), and assuming that the latter period was a truer estimate of new trials actually being initiated each year, I estimated the proportion of studies that were probably not being registered during 2000–2004. Overall, plausibly 79% of studies were not being registered prior to 2005; for industry-sponsored trials, 85.6% were not being registered; for non-industry trials 72.7% were not being registered; and for trials with blended funding, 95.7% were not being registered.

A smaller increase in registrations occurred in 2008. This appears coincident with when FDAMA was amended in 2007 to require posting of results within 1 year, and when ICMJE updated its policy in 2008 to also require registration of Phase I and pharmacokinetic studies.

Registration of studies on CTG

Even excluding the backlog of ongoing studies that came in during 1999 (for which studies registered an average of 1204 days (SD 1386 days) after study start), late registration was the rule rather than the exception (table 2). On average, studies were registered on CTG 322 days (SD 764 days) after the study had begun, with non-industry-sponsored studies showing the greatest delay and industry studies the least: 442 days (SD 929 days) vs 216 days (SD 577 days), respectively (ANOVA, 2df, p<0.001). Viewed another way, among trials that listed a start date on CTG, 55.7% (29 035 /52 622) registered after the 21-day window mandated by FDAMA. Compared with studies funded by industry, non-industry studies were less likely to be registered on time than industry studies (AOR 0.51, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.54). Across all years, 56.0% (8426/15 048) of industry studies vs 38.5% (12 063/31 333) of non-industry studies registered on time (χ2, 2 df, p<0.001). Among industry-sponsored studies, the proportion registered on time steadily increased over the years (figure 2), with the exception of 2005, the year after the ICMJE's policy was issued. Consistent with the theory that this transient drop in compliance was driven by a backlog of ongoing studies being registered en masse, the average delay to registration for studies registered in 2005 was several hundred days longer than in either of the two adjacent years (table 2). Nonetheless, by 2011, non-industry studies and industry studies, respectively, still registered an average of 256 (SD 762 days) and 139 days (SD 557 days) after study start (ANOVA, 2df, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Time between registration on Clinicaltrials.gov website and study start, by year and source of funding

| Year registered | Source of funding | Number of trials registered in year* | Mean delay from start to registration (days) | SD (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | Industry only | 83 | −579.6 | 514.1 |

| Non-industry only | 2043 | −1238.2 | 1406.7 | |

| Blended | 18 | −274.5 | 1385.9 | |

| Total | 2144 | −1204.7 | 1385.9 | |

| 2000 | Industry only | 68 | −193.5 | 178.5 |

| Non-industry only | 918 | −255.1 | 749.2 | |

| Blended | 22 | −373.2 | 542.4 | |

| Total | 1008 | −253.5 | 721.1 | |

| 2001 | Industry only | 85 | −173.4 | 186.8 |

| Non-industry only | 960 | −364.8 | 694.8 | |

| Blended | 18 | −239.2 | 267.2 | |

| Total | 1063 | −347.4 | 665.4 | |

| 2002 | Industry only | 341 | −181.9 | 321.6 |

| Non-industry only | 765 | −191.9 | 582.6 | |

| Blended | 58 | −347.8 | 530.4 | |

| Total | 1164 | −196.8 | 517.9 | |

| 2003 | Industry only | 332 | −134 | 340.3 |

| Non-industry only | 1001 | −246.7 | 722.2 | |

| Blended | 42 | −170.4 | 382.9 | |

| Total | 1375 | −217.2 | 643.6 | |

| 2004 | Industry only | 415 | −120.3 | 245.7 |

| Non-industry only | 872 | −167.7 | 449.6 | |

| Blended | 36 | −310.3 | 677.7 | |

| Total | 1323 | −156.7 | 406.7 | |

| 2005 | Industry only | 1704 | −348.5 | 556.9 |

| Non-industry only | 3539 | −617.2 | 964.4 | |

| Blended | 899 | −563.1 | 704.1 | |

| Total | 6142 | −534.7 | 841.4 | |

| 2006 | Industry only | 1643 | −183.9 | 531.8 |

| Non-industry only | 3084 | −485.2 | 971.8 | |

| Blended | 735 | −281.1 | 624 | |

| Total | 5462 | −367.1 | 830.4 | |

| 2007 | Industry only | 1897 | −168.7 | 502.4 |

| Non-industry only | 3739 | −557.2 | 1032.7 | |

| Blended | 1007 | −358.5 | 675.4 | |

| Total | 6643 | −416.1 | 877.8 | |

| 2008 | Industry only | 3001 | −335.1 | 715 |

| Non-industry only | 4321 | −383.4 | 803.8 | |

| Blended | 1067 | −265.9 | 748.2 | |

| Total | 8389 | −351.2 | 767 | |

| 2009 | Industry only | 2354 | −194.9 | 626.7 |

| Non-industry only | 4290 | −316.6 | 840.8 | |

| Blended | 1035 | −145.2 | 497.4 | |

| Total | 7679 | −256.2 | 743.9 | |

| 2010 | Industry only | 2201 | −94.4 | 489.2 |

| Non-industry only | 4076 | −238.9 | 719.5 | |

| Blended | 937 | −146.5 | 532.5 | |

| Total | 7214 | −182.8 | 637.6 | |

| 2011 | Industry only | 924 | −139.3 | 556.7 |

| Non-industry only | 1725 | −255.5 | 762.1 | |

| Blended | 364 | −76.2 | 345.4 | |

| Total | 3013 | −198.2 | 668.2 | |

| Total | Industry only | 14965 | −215.9 | 576.5 |

| Non-industry only | 29290 | −441.9 | 929.3 | |

| Blended | 6220 | −277.1 | 636.9 | |

| Total | 52619* | −321.8 | 763.7 |

*Total is limited to studies that indicated their funding source.

Figure 2.

Proportion of studies registered on time on Clinicaltrials.gov, by year and funding source.

In multivariate analyses (adjusting for sexes included age groups, year of registration, study phase and source of funding), on-time registration became steadily more likely with each year after 1999. Compared with Phase I studies, Phase II and III studies were 20% more likely to be registered on time, whereas Phase IV trials were 20% less likely. Neither the age composition nor gender of study subjects were associated with the likelihood of registering on time (table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted odds for on-time registration of studies on Clinicaltrials.gov

| p Value | Adjusted OR* | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexes of subjects included | |||

| Females only | Reference | ||

| Males only | 0.18 | 0.9 | 0.8 to 1.0 |

| Females and males | 0.08 | 1.1 | 1.0 to 1.2 |

| Age groups included | |||

| Adults | Reference | ||

| Adults and children | 0.18 | 1.0 | 0.9 to 1.0 |

| Children only | 0.46 | 1.0 | 0.9 to 1.1 |

| Year of registration | |||

| 1999 | Reference | ||

| 2000 | <0.001 | 11.5 | 8.8 to 15.0 |

| 2001 | <0.001 | 8.9 | 6.8 to 11.6 |

| 2002 | <0.001 | 9.1 | 7.0 to 11.9 |

| 2003 | <0.001 | 11.9 | 9.2 to 15.4 |

| 2004 | <0.001 | 11.8 | 9.1 to 15.2 |

| 2005 | <0.001 | 5.5 | 4.3 to 7.0 |

| 2006 | <0.001 | 15.5 | 12.2 to 19.7 |

| 2007 | <0.001 | 15.6 | 12.3 to 19.8 |

| 2008 | <0.001 | 19.9 | 15.7 to 25.2 |

| 2009 | <0.001 | 31.4 | 24.8 to 39.9 |

| 2010 | <0.001 | 42.3 | 33.3 to 53.8 |

| 2011 | <0.001 | 46.8 | 36.4 to 60.3 |

| Study phase | |||

| Phase I | Reference | ||

| Phase II | <0.001 | 1.2 | 1.2 to 1.3 |

| Phase III | <0.001 | 1.2 | 1.1 to 1.3 |

| Phase IV | <0.001 | 0.8 | 0.7 to 0.9 |

| Source of funding | |||

| Industry only | Reference | ||

| Non-industry only | <0.001 | 0.6 | 0.6 to 0.7 |

| Blended | <0.001 | 0.8 | 0.8 to 0.9 |

*Logistic regression model included the following covariates: sex composition of subjects; age groups; year of registration; study phase; and source of funding.

Posting of results on CTG

Within the period 28 September 2007 and 23 June 2010, a total of 7442 US-based, intervention studies at Phase II or beyond were entered as completed on CTG (table 4). Of these, 3368 were sponsored solely by industry (45.3%). Indexing the number of studies that posted results on CTG against the number of studies completed in the same interval, the proportion of posted/completed peaked in 2008 for industry-sponsored studies at 33.7%, and averaged 28.0% across the entire period. Non-industry-sponsored studies were not required to post results to CTG, and >90% did not. Compared with non-industry studies, industry studies were significantly more likely to post results of completed studies to CTG (RR 4.3, 95% CI 3.7 to 4.9).

Table 4.

Posting of study results on Clinicaltrials.gov website indexed against number of completed trials, by year and source of study funding

| Year | Source of funding | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Non-industry | Blended‡ | Total | |

| 2007* | ||||

| No. posted | 73 | 11 | 4 | 88 |

| No. completed in interval | 260 | 234 | 74 | 568 |

| % posted/completed | 28.1 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 15.5 |

| 2008 | ||||

| No. posted | 434 | 81 | 53 | 568 |

| No. completed in interval | 1286 | 908 | 320 | 2514 |

| % posted/completed | 33.7 | 8.9 | 16.6 | 22.6 |

| 2009 | ||||

| No. posted | 339 | 86 | 57 | 482 |

| No. completed in interval | 1252 | 1225 | 406 | 2883 |

| % posted/completed | 27.1 | 7.0 | 14.0 | 16.7 |

| 2010† | ||||

| No. posted | 95 | 31 | 21 | 147 |

| No. completed in interval | 562 | 696 | 204 | 1462 |

| % posted/completed | 16.9 | 4.5 | 10.3 | 10.1 |

| Total | ||||

| No. posted | 941 | 209 | 135 | 1285 |

| No. completed in interval | 3360 | 3063 | 1004 | 7427 |

| % posted/completed | 28.0 | 6.8 | 13.4 | 17.3 |

*Interval limited to postings from 28 September 2007.

†Interval limited to postings through 23 June 2010.

‡Industry and non-industry funding.

Analysis data set limited to US-based, intervention studies at Phase II or beyond.

Among the industry-sponsored studies at Phase II or beyond, within this same time period, 13.7%, 36.9% and 49.4% of Phase II, III and IV studies, respectively, posted results to CTG. In multivariate analysis, factors related to posting vs non-posting included paediatric study populations, completion of the study in 2008 (the first year that FDAAA came into effect) and studies beyond Phase II (table 5).

Table 5.

Factors related to posting of study results on Clinicaltrials.gov for US-based Phase II, II or IV industry sponsored studies*

| p value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexes of subjects included | |||

| Females only | Reference | ||

| Males only | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.8 to 2.5 |

| Females and males | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.7 to 1.4 |

| Age groups included | |||

| Adults | Reference | ||

| Adults and children | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.9 to 1.6 |

| Children only | <0.001 | 2.9 | 2.1 to 4.0 |

| Year trial completed | |||

| 2007 | Reference | ||

| 2008 | <0.001 | 1.5 | 1.1 to 2.0 |

| 2009 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.8 to 1.5 |

| 2010 | <0.001 | 0.6 | 0.4 to 0.9 |

| Study phase | |||

| Phase II | Reference | ||

| Phase III | <0.001 | 3.4 | 2.8 to 4.1 |

| Phase IV | <0.001 | 6.0 | 4.6 to 7.2 |

*Analysis set limited to industry-sponsored, US-based, intervention studies at Phase II or beyond for which the study completion date listed on clinicaltrials.gov fell between 28 September 2007 and 23 June 2010, inclusive. The final model included the following covariates: gender of subjects; age group of subjects; year of study completion; and study phase.

Discussion

This analysis indicates that compliance with registration of US-based human subject research trials on CTG remains quite poor. While compliance with registration has improved substantially since 2005, overall >50% of studies register after the 21 day limit set by FDAMA, with an average delay from study start to registration on CTG of >200 days. Since (by definition) this analysis only included studies that were registered on CTG, it is impossible to precisely define what proportion of studies were left unregistered. What the analysis could show was that the ICMJE's policy on registration was temporally associated with a significant increase in registration rates. The implication of this is that prior to 2005, plausibly 80% or more of studies were not being registered at all.

Interestingly, in 2006, the FDA conducted an internal audit of CTG compliance within a subset of industry-sponsored oncology trials registered between May and July 2005. Of these, only 76% had been registered on CTG.11 This suggests that non-registration may still be very common. Similarly, even among those studies specifically targeted by FDAAA for posting results on CTG, >75% do not currently so. While this analysis focuses solely on metrics defined by the registration/posting process, poor quality of the data that are entered on CTG is a further problem that will need to be addressed in the future.12

Regarding the pattern of registering trials on CTG, several points merit further discussion.

First, studies are frequently registered on CTG long after data collection has begun. For patients who might be interested in enrolling in ongoing studies, late registration constitutes a barrier to enrolment and therefore conflicts with the principles for the ethical conduct of clinical research. Late registration may also contribute to publication bias by allowing for interim reviews of study data prior to registration. Consequences could range from sponsors amending key study endpoints post hoc, or even halting studies and foregoing registration entirely if results appear to be unfavourable.

Second, it appears that funding source is strongly associated with registration rates on CTG. This may reflect the fact that industry-sponsored trials operate within a highly scrutinised and regulated research environment, in which non-compliance could lead to financial penalties or suspension of an IND, or that industry has more resources available and is thus better able to respond to the reporting mandate. Regardless, FDAMA provides no exemption on the basis of sponsorship, and publication bias has an equally corrosive influence on the fidelity of the published literature, regardless of funding source. What are some key messages from this analysis? First, the mere fact of a statutory requirement for the registration of trials, for registration to be on time and for results to be posted, does not appear to have had much impact on the behaviours of researchers and sponsors conducting trials in the USA. In contrast, the non-statutory penalty imposed by ICMJE's refusal to publish unregistered trials had a very potent effect on registrations.

Third, judging by how few results are posted to CTG, attempts to curb publication bias through statute do not appear to have been terribly successful. Given how influential the ICMJE was on encouraging registrations and on-time registrations, one could question whether a similarly powerful impact could be seen if sponsors were also required to post their results on CTG prior to completing the peer-review process. It should be noted that the FDAAA focused only on a particular category of research studies, namely US-based, later phase interventional studies governed under an IND application. Outside these parameters, non-publication of research remains a very serious problem. In a recent analysis of NIH-sponsored studies that were registered on CTG, only 68% of studies had been published in the literature, even after allowing for 30 months to pass from the time the study was listed as complete on CTG.13

This analysis had several limitations. First, because of the large number of studies included, it was not possible to manually inspect all studies in the set to confirm whether all would have met the requirements for registration on CTG. It is possible that some studies that were registered on CTG were not required to have done so, and this could overestimate the degree of non-compliance to some degree. Similarly, the requirement to post results on CTG only applied to industry-sponsored US-based intervention studies governed under IND at Phase II or beyond. I limited the analysis set to studies that met these parameters, but it is still possible that this restricted set might have contained some studies that fell outside the mandate of the statute. That said, of the 200 studies I manually inspected after applying my limits for the analysis, all proved to be Phase II, US-based intervention studies as expected. Therefore, the effect of this misclassification, if any, should be minimal.

Second, the definition of studies to be covered by the FDAMA statute as ‘serious and life-threatening conditions’ is somewhat vague. Recognising this ambiguity, FDA issued guidance that this should be interpreted broadly rather than narrowly, citing depression as an example of a condition that was serious and potentially life threatening. In this analysis, I therefore assumed that a sponsor's decision to register a study on CTG indicated that the sponsor deemed the study to have met these criteria, but it is possible that some proportion did not need to be registered.

Lastly, the number of postings reflects a theoretical maximum, since studies supporting new drugs under review for licensure are not required to post results until licensure has been granted. Unfortunately, there was no practical way to determine what proportion of studies in the data set might have qualified from this exemption. Nevertheless, the overall conclusion that posting rates are sub-optimal remains intact.

The results from this analysis are in broad agreement with two other recent analyses of the CTG dataset. Law et al. also found that studies often registered late and rarely posted their results. One notable difference, Law's analysis indicated a far lower rate of compliance with posting of results from industry-sponsored studies than the current analysis (9.5% vs 28.0%). One factor that might account for this difference is time, since Law's analysis included CTG data through May 2010. It is possible that many studies posted results subsequent to that time and were captured in the current analysis. In support of this theory, Law noted that a large number of studies posted their results after a delay of 300 days or more.14 Similarly, Prayle et al15 analysed CTG data through December 2009, and found that few studies posted results, with higher rates among industry-sponsored trials.

Moving forward, it is important to better understand the reasons for non-compliance with registration and reporting of results. While much of the focus regarding compliance has centred on industry-sponsored studies, academic institutions are also governed by FDAMA. At present, it is unknown as to whether non-compliance is due to willful disregard of the mandates, reflects a lack of resources with which to be compliant or other factors. For example, it could be instructive to better understand the experience of registering or reporting on CTG, to determine whether ‘ease of use’ is relevant to compliance and could be improved.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Drs Matthew Fox, Donald Thea and Jonathon Simon for their thoughtful advice during this analysis. Dr Gill declares that he has no conflicts of interest related to this analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: CJG conceived the analysis, downloaded the data set, performed the statistical analysis and solely wrote the manuscript. The data sets for this analysis can be provided on request.

Funding: This work was not supported by any outside funding agency.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The raw data files used for this analysis have been uploaded to DRYAD for public access: DOI 10.5061/dryad.4j190.

References

- 1.Food and Drug Administration FDA Modernization Act of 1997, Public Law 105–115, 105th Congress. Section 113, Information program on clinical trials for serious or life-threatening diseases. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Food and Drug Administration Guidance for industry: information program on clinical trials for serious or life-threatening diseases and conditions. In: CBER Ca Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007 121 Stat. 823. USA: US Government Printing Office, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tse T, Williams RJ, Zarin DA. Reporting ‘basic results'in ClinicalTrials.gov. Chest 2009;136:295–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, et al. The ClinicalTrials.gov results database – update and key issues. N Engl J Med 2011;364:852–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institutes of Health The Belmont Report: ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health, 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy P, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet 2004;363:1341–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham DJ. COX-2 inhibitors, other NSAIDs, and cardiovascular risk: the seduction of common sense. JAMA 2006;296:1653–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ioannidis JP. Effectiveness of antidepressants: an evidence myth constructed from a thousand randomized trials? Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2008;3:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FAet al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:477–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Food and Drug Administration FDAMA Section 113: analysis of cancer trials submitted May-July, 2005. Washington, DC: Food and Drug Administration, Office of Special Health Issues, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viergever RF, Ghersi D. The quality of registration of clinical trials. PLoS One 2011;6:e14701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross JS, Tse T, Zarin DA, et al. Publication of NIH funded trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional analysis. BMJ 2012;344:d7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Law MR, Kawasumi Y, Morgan SG. Despite law, fewer than one in eight completed studies of drugs and biologics are reported on time on ClinicalTrials.gov. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:2338–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prayle AP, Hurley MN, Smyth AR. Compliance with mandatory reporting of clinical trial results on ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional study. BMJ 2012;344:d7373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.