Abstract

Objectives

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF1α) plays an integral role in response to hypoxia, controlling dozens of target genes including aldolaseC (ALDC), an important enzyme in the glycolytic pathway. It also induces angiogenesis, allowing survival and proliferation of cancer cells. The aims of our study were to evaluate the expressions of HIF1α and ALDC in patients with endometrial cancer (EC) and define their association with disease outcome and to determine the existence of an association between HIF1α and ALDC proteins.

Design

This is a population-based retrospective cohort study using the gynaecological-oncology database. The authors identified all women with EC with adequate follow-up. Immunohistochemistry using antibodies to ALDC and HIF1α was performed on paraffin-embedded tissue from 279 patients. To test the association between ALDC /HIF1α protein using immunohistochemistry (IHC) (positive and negative) and the clinical parameters, Fisher's exact test was performed for categorical parameters and the logistic regression model was used for continuous ones. Pearson correlation was used to check the association of IHC between ALDC and HIF1α.

Setting

Academic referral centre.

Participants

Women with EC from 2000 to 2010 obtained from the gynaecological-oncology database.

Outcome measures

The disease outcome is defined by alive with no evidence of disease versus all other outcomes.

Results

ALDC and HIF1α were overexpressed in the vast majority of EC cases (78% and 76%, respectively). There was a strong positive association between HIF1α and ALDC (p=0.0017). There was a significant association between ALDC and depth of myometrial invasion (p=0.0438), and between HIF1α and tumour grade (p=0.0231) and tumour subtype (p=0.018). However, there was no association between neither ALDC nor HIF1α and disease status.

Conclusions

ALDC and HIF1α play an important role in endometrial carcinogenesis. Their expression by the majority of EC makes inhibition of HIF1α a very attractive therapeutic option for treating patients with EC and we suggest that it will be prospectively validated in future studies.

Keywords: Basic Sciences, Pathology, Gynaecology, Gynaecological oncology

Article summary.

Article focus

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF1α) and aldolaseC (ALDC) expressions in patients with endometrial cancer (EC).

HIF1α and ALDC interaction in vivo in EC.

HIF1α and ALDC value in predicting disease outcome in patients with EC.

Key messages

HIF1α and ALDC are frequently expressed in EC.

There is a strong association between HIF1α and ALDC in EC and therefore they could play an important role in its pathogenesis.

HIF1α and ALDC are associated with poor prognostic factors.

HIF1α and ALDC are not independent predictive biomarkers of poor outcome.

Strengths and limitations of this study

It is a large study of 279 patients.

It is one of the few in the literature.

It is the first to evaluate the association of HIF1α and ALDC in vivo in EC.

The study did not have a large numbers of type II cancers (serous and clear cell carcinomas).

The study did not contain too many cases of late-stage tumours (stage III and IV).

Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynaecological malignancy in developed countries. There are approximately 42 000 cases diagnosed annually in the USA, resulting in almost 8000 deaths.1. EC has been classified into two types based on morphology, pathogenesis, behaviour and treatment: type I (endometrioid and mucinous carcinomas) and type II (serous and clear cell carcinomas). Type I is usually low grade and low stage at initial presentation. Type II is usually high grade and in an advanced stage at initial presentation. The most reliable prognostic factors in predicting disease outcome in EC are tumour grade, tumour stage, tumour subtype, depth of myometrial invasion and lymph node involvement.2–4

One of the most prominent metabolic alterations in cancer cells is an increase in aerobic glycolysis, known as the Warburg effect after its discovery by Otto Warburg in 1920.5 This increase in glycolysis, due to a shift in glucose metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation into the aerobic glycolysis pathway, provides the tumour with metabolic and survival advantages.6–8 Aldolase, a critical enzyme in the glycolytic pathway, catalyses the reversible conversion of fructose-1,6-biphosphate to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate. Aldolase has three distinct isoenzymes, A, B and C, which are similar in sequence with 78% identity between A and C and 68% identity between B and C.9 10 Originally identified in brain tissue, aldolaseC (ALDC) has been seen to be overexpressed in carcinomas of the lung, kidney, cervix and endometrium.11–13

The hypoxic-inducible factor (HIF1) gene codes for two subunits, α and β, and is usually activated by hypoxic conditions, a microenvironment that commonly accompanies cancerous tumours. When activated, HIF1 can interact with enzymes and other transcription factors in order to control vascularisation and tissue growth. HIF1α was recently identified as a potent regulator of ALDC, another mechanism by which it may promote carcinogenesis.14 Thus, attempts to target the HIF1α pathway in hopes of suppressing cancer cell proliferation and progression are underway. In the gynaecological tract, HIF1α expression increases as the endometrium undergoes changes from normal to premalignant to endometrioid adenocarcinoma (EAC). This is paralleled by increased angiogenesis in the endometrium, suggesting that HIF1α might be a key regulator in endometrial carcinogenesis.15

Although the interaction between HIF1α and ALDC has been seen in vivo, their interaction in human samples and in endometrial carcinoma has not yet been described. Therefore, the aims of this study are (1) to evaluate the expression of HIF1α and ALDC proteins in patients with EC and to find an association between these two proteins in this patient sample and (2) to determine whether either of these two proteins independently or any combination of their expressions might have an impact on disease outcome.

Materials and methods

Patient population

After obtaining IRB approval, the pathology archives were searched for endometrial carcinoma cases from January 2000 to December 2010. Data were extracted from clinical charts including patients’ age at the time of diagnosis, surgical stage, postoperative therapy, site of recurrence, and cause and time of death. All patients underwent surgical staging with a total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH+BSO), and pelvic washings. Pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy was performed for patients with advanced stage disease and high-grade tumours. Patients were treated according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (www.cancer.gov).

Histological evaluation

Tumour grade was assessed using the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system and by nuclear grading. FIGO grading was determined as follows; tumours with <5% solid areas were grade 1 (G1), tumours with 5–50% solid areas were grade 2 (G2) and tumours with >50% solid areas were grade 3 (G3). Nuclear grade of tumours was determined by the variation in nuclear size and shape, chromatin distribution and size of the nucleoli. Grade 1 nuclei are oval, mildly enlarged and have evenly dispersed chromatin. Grade 3 nuclei are markedly enlarged and pleomorphic and have preominent eosinophilic nucleoli. Grade 2 nuclei have features between G1 and G3. Tumour stage was assigned based on 1988 FIGO surgical staging guidelines.16 All slides were examined by an expert gynaecological pathologist for confirmation of the histologic type, tumour size, tumour grade, depth of myometrial invasion (MI) and presence of lymphovascular invasion (LVI).

Immunohistochemistry

Four micron thick sections from 279 cases were deparaffinised with xylene and washed with ethanol. In addition, five sections from normal endometrium were also included in the study. Sections were cooled for 20 min and incubated for 10 min with 3% H2O2 to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Blocking was performed using a serum-free protein block, Dakocytomation (Carpenteria, California, USA), for 30 min. The sections were pretreated with an EDTA buffer saline solution, steamed for 20 min and then sections were incubated with HIF1α (monoclonal; 1 : 1000 dilution; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, Colorado, USA) and ALDC (monoclonal; 1 : 250 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. The diaminobenzidine complex was used as a chromogen. Negative control slides omitting the primary antibody were included in all assays. Breast cancer was used as positive controls for HIF1α and ALDC. The extent of immunochemical reactivity was graded based on intensity as follows: 0 (negative), 1+ (weak), 2+ (moderate), 3+ (strong). For the sake of statistical analysis, negative and weak stains were grouped as group I (negative) and moderate and strong as group II (positive).

Statistical analyses

The clinical parameters used for modelling were age, tumour size, histological subtype, tumour stage, myometrial depth of invasion, LVI, FIGO grade, nuclear grade, lymph node status, recurrence, recurrence time, survival time and status. To test the association between ALDC/HIF1α IHC (positive and negative) and the clinical parameters, Fisher's exact test was performed for categorical parameters and the logistic regression model was used for continuous ones. Pearson correlation was used to check the association of IHC between ALDC and HIF1α. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package R (http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Clinical and pathological features

Two hundred and seventy-nine patients diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma were included in the study. The age ranged from 29 to 97 years (median age 65 years). The follow-up period ranged from 0 (as one patient was lost for follow-up) to 137.16 months (median 46.32 months). The clinical and histological features are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathological features of patients (data in parentheses are percentages)

| Characteristics | |

| No. of evaluable patients | 279 |

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 65 |

| Range | 29–97 |

| Follow time (months) | |

| Median | 46.32 |

| Range | (0–137.16) |

| Stage | |

| I | 181 (64.87) |

| II | 35 (12.54) |

| III | 43 (15.41) |

| IV | 20 (7.17) |

| Subtype | |

| Endometrioid | 202 (72.4) |

| CCC+serous | 77 (27.6) |

| Grade (FIGO) | |

| 1 | 119 (42.65) |

| 2 | 53 (19) |

| 3 | 107 (38.35) |

| Grade (nuclear) | |

| 1 | 93 (33.33) |

| 2 | 75 (26.88) |

| 3 | 111 (39.78) |

| Tumour size (cm) | |

| ≤2 | 62 (22) |

| >2 | 217 (78) |

| Depth of invasion | |

| Median | 28 |

| Range | 0–100 |

| LVI | |

| No | 202 (72.4) |

| Yes | 77 (27.6) |

| Lymph node status | |

| Positive | 50 (17.92) |

| Negative | 135 (48.39) |

| Unknown | 94 (33.69) |

| Recurrence | |

| No | 215 (77.06) |

| Yes | 47 (16.85) |

| Persistent | 12 (4.3) |

| Progression | 4 (1.43) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.36) |

| Status | |

| ANED | 188 (67.38) |

| AWED | 22 (7.89) |

| DOD | 38 (13.62) |

| DNED | 22 (7.89) |

| Dead unknown cause | 1 (0.36) |

| DWED | 7 (2.51) |

| Lost for FU | 1 (0.36) |

ANED, alive with no evidence of disease; AWED, alive with evidence of disease; CCC, clear cell carcinoma; DOD, dead of disease; DNED, dead with no evidence of disease; DWED, dead with evidence of disease; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

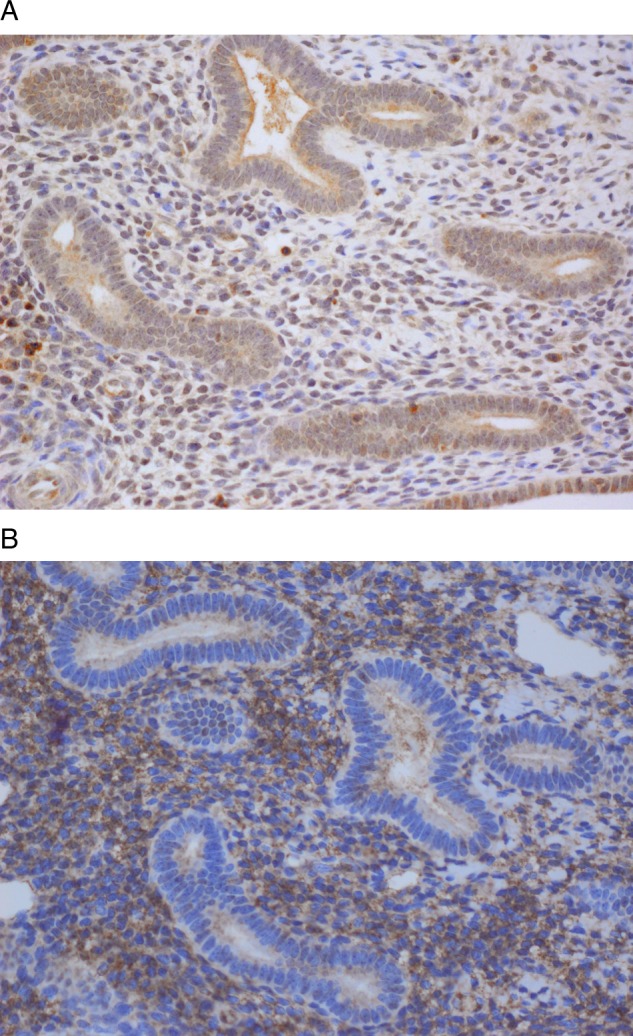

ALDC and HIF1α immunoexpressions

The staining patterns were nuclear for HIF1α and cytoplasmic for ALDC. The five cases of normal endometrium all came from patients who underwent a hysterectomy for benign reasons, such as fibroids, and were weakly positive for ALDC and negative for HIF1α (figure 1A,B). There was a strong positive association between ALDC and HIF1α proteins (p=0.0017) in EC. The results of the association of ALDC and the clinical–pathological variables are shown in table 2. Fifty-nine of 279 (22%) cases were negative for ALDC protein and 220/279 (78%) were positive (figure 2A,B). ALDC was only associated with depth of myometrial invasion (p=0.0438), lending to the conclusion that tumours invading deeper into the myometrium are more likely to overexpress ALDC.

Figure 1.

(A) AldolaseC is negative in normal endometrium (× 40) and (B) Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α is negative/weakly positive in normal endometrium (×40).

Table 2.

Association of aldolaseC IHC with clinicopathologic variables

| Negative |

Positive |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (n=59) | (n=220) | |

| Age (median) | 69 | 65 | 0.4* |

| Myometrial invasion (median) | 21 | 31.5 | 0.0438 |

| Stage | |||

| I | 41 (69.49) | 140 (63.64) | 0.7656 |

| II | 8 (13.56) | 27 (12.27) | |

| III | 7 (11.86) | 36 (16.36) | |

| IV | 3 (5.08) | 17 (7.73) | |

| Tumour size (cm) | |||

| ≤2 | 15 (25.42) | 47 (21.36) | 0.4866** |

| >2 | 44 (74.58) | 173 (78.64) | |

| LVI | |||

| No | 46 (77.97) | 156 (70.91) | 0.3273 |

| Yes | 13 (22.03) | 64 (29.09) | |

| Grade_FIGO | |||

| 1 | 24 (40.68) | 95 (43.18) | 0.9266 |

| 2 | 11 (18.64) | 42 (19.09) | |

| 3 | 24 (40.68) | 83 (37.73) | |

| Grade_nuclear | |||

| 1 | 15 (25.42) | 78 (35.45) | 0.3096 |

| 2 | 19 (32.2) | 56 (25.45) | |

| 3 | 25 (42.37) | 86 (39.09) | |

| Lymph node status | |||

| Positive | 6 (16.22) | 44 (29.73) | 0.1461 |

| Negative | 31 (83.78) | 104 (70.27) | |

| Subtype | |||

| CCC+Serous | 17 (28.81) | 60 (27.27) | 0.87 |

| Endometrioid | 42 (71.19) | 160 (72.73) | |

| Recurrence | |||

| No | 45 (81.82) | 170 (82.13) | 1 |

| Yes | 10 (18.18) | 37 (17.87) | |

| Status | |||

| ANED | 41 (69.49) | 147 (66.82) | 0.7561 |

| Others | 18 (30.51) | 73 (33.18) | |

*p Value calculated by logistic linear regression.

**p Value calculated by Fisher's exact test.

ANED, alive with no evidence of disease; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; IHC, immunohistochemical; LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

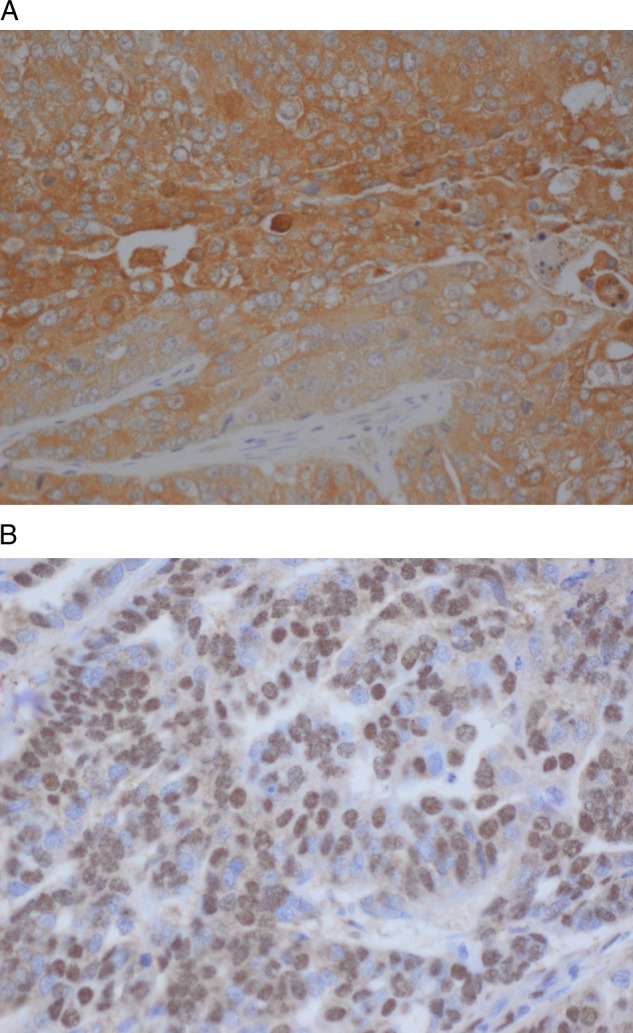

Figure 2.

(A) AdolaseC in endometrioid adnoacrcinoma exhibiting a strong cytoplasmic pattern. (B) HIF1a in endometrid adenocarcinoma with strong nuclear pattern.

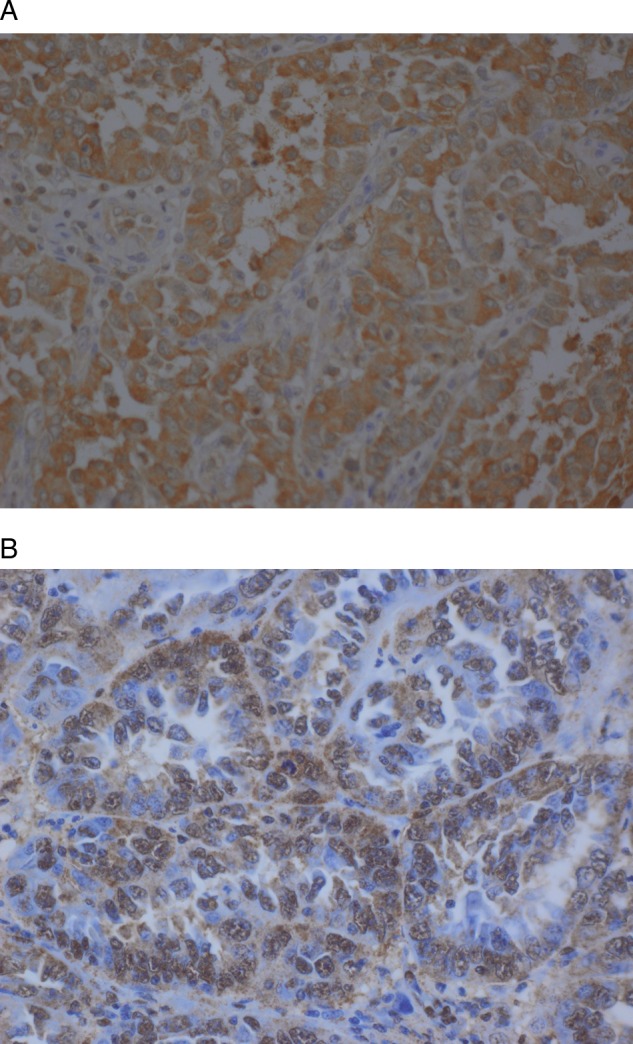

The results of the association between HIF1α and the clinical–pathological variables are summarised in table 3. Sixty-six of 279 (24%) cases did not express HIF1α and 213/279 (76%) did (figure 3B). There was an association between HIF1α and histological subtype and tumour grade (p=0.018 and 0.0368, respectively). This led us to the conclusion that EACs are more likely to express HIF1α than clear cell and serous adenocarcinomas. In addition, high-grade tumours, G2 and G3, are more likely to express HIF1α than low-grade tumours (G1).

Table 3.

Association of IHF1α IHC with clinicopathological variables

| Negative |

Positive |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (n=66) | (n=213) | |

| Age (median) | 65 | 65 | 0.3571* |

| Myometrial invasion (median) | 40 | 25 | 0.0646** |

| Stage | |||

| I | 39 (59.09) | 142 (66.67) | 0.6376 |

| II | 10 (15.15) | 25 (11.74) | |

| III | 11 (16.67) | 32 (15.02) | |

| IV | 6 (9.09) | 14 (6.57) | |

| Tumour size (cm) | |||

| ≤2 | 15 (22.73) | 47 (22.07) | 1 |

| >2 | 51 (77.27) | 166 (77.93) | |

| LVI | |||

| No | 46 (69.7) | 156 (73.24) | 0.6367 |

| Yes | 20 (30.3) | 57 (26.76) | |

| Grade_FIGO | |||

| 1 | 22 (33.33) | 97 (45.54) | 0.0231 |

| 2 | 9 (13.64) | 44 (20.66) | |

| 3 | 35 (53.03) | 72 (33.8) | |

| Grade_nuclear | |||

| 1 | 19 (28.79) | 74 (34.74) | 0.0368 |

| 2 | 12 (18.18) | 63 (29.58) | |

| 3 | 35 (53.03) | 76 (35.68) | |

| Lymph node status | |||

| Positive | 14 (26.92) | 36 (27.07) | 1 |

| Negative | 38 (73.08) | 97 (72.93) | |

| Subtype | |||

| CCC+Serous | 26 (39.39) | 51 (23.94) | 0.018 |

| Endometrioid | 40 (60.61) | 162 (76.06) | |

| Recurrence | |||

| No | 48 (81.36) | 167 (82.27) | 0.849 |

| Yes | 11 (18.64) | 36 (17.73) | |

| Status | |||

| ANED | 40 (60.61) | 148 (69.48) | 0.1805 |

| Others | 26 (39.39) | 65 (30.52) | |

*p Value calculated by logistic linear regression.

**p Value calculated by Fisher's exact test.

ANED, alive with no evidence of disease; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HIF1α, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α; IHC, immunohistochemical; LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

Figure 3.

(A) AldolaseC in serous adenocarcinoma showing a strong cytoplasmic staining. (B) HIF1a in serous adenocarcinoma with strong nuclear pattern.

Finally, neither ALDC nor HIF1α proteins individually, or any combination of their expressions—(ALDC+/HIF1α−), (ALDC+/HIF1α+), (ALDC−/HIF1α+), (ALDC−/HIF1α−)—had an impact on disease outcome such as recurrence, progression or death of disease.

Discussion

HIF1α is a transcription factor and it is a major regulator of oxygen homeostasis within cells.14 It plays an important role in tumourigenesis through its enhancement of angiogenesis via regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) transcription, which promotes endothelial cell migration towards a hypoxic area. In addition, in hypoxic conditions, HIF1α regulates metabolism by shifting the production of ATP via oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic metabolism by stimulation of a variety of glycolytic enzymes, including ALDC.17 18 Even though this relation between HIF1α and ALDC is well established in vitro and animal models, their association in human cancer tissues, namely EC, is still widely unexplored. Our main goal was to evaluate the expression of ALDC and HIF1α in a large series of cases of EC. We found that ALDC and HIF1α were both expressed in the majority of EC cases and they were negative in normal endometrium. In addition, a strong positive association between HIF1α and ALDC was seen in these cases.

Previously, using cDNA microarray, we showed that one of the genes that is upregulated in uterine serous carcinoma in comparison with EAC is aldolaseC.19 20 Furthermore, qRT-PCR showed that the ALDC mRNA level was overexpressed in endometrial carcinomas in comparison with normal endometrium, but there was no association between ALDC-mRNA level and the EC subtypes.21 Similarly, in this study, we found that ALDC was not associated with tumour subtype. However, it was associated with one of the most reliable pathological prognostic factors of poor outcome, depth of myometrial invasion. In addition, we found that overexpression of HIF1α is associated with high tumour grade, another major prognostic factor of poor outcome in patients with EC. This further confirms that ALDC and HIF1α overexpression may be related to tumour aggressiveness.15 22. All the above data lead us to suggest that these two proteins may be key regulators in endometrial carcinogenesis.

Recently, with clearer understanding of the function of HIF1α and its pathway, efforts directed at manipulation of this complex in order to decrease cellular HIF1α levels in tumour cells have been undertaken. Thus, modulation of HIF1α and its pathway promises to have a significant impact on cancer and it seems to be an attractive therapeutic option for patients with EC.

In summary, ALDC and HIF1α seem to play a role in the tumourigenesis of EC and their expression may be an indication of tumour aggressiveness, and we suggest that prospectively it will be validated in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: PMF designed and wrote the study; DW and SL performed the statistical analysis; DS, HG and TM reviewed the patients charts; DS and FO helped in reviewing the manuscript; SL and TP were involved in conducting and writing the study.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the IRB committee and was conducted with maintenance of respect to privacy of all patients throughout.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:225–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Part J. Prognostic parameters of endometrial carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2004;35:649–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitchener HC, Trimble EL. Endometrial cancer state of the science meeting. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2009;19:134–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naumann RW. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: state of the state. Curr Oncol Rep 2008;10:505–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956;123:309–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckner ME, Stracke ML, Liotta LA, et al. Glycolysis as primary energy source in tumor chemotaxis. J Natl Cancer Inst 1990;82:1836–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greiner EF, Guppy M, Brand K. Glucose is essential for proliferation and the glycolytic enzyme induction that provokes a transition to glycolytic energy production. J Biol Chem 1994;269:31484–490 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saw RJ. Glucose metabolism and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2006;18:598–08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurganov BI, Sugrobova NP, Mil'man LS. Supramolecular organization of glycolytic enzymes. J Theor Biol 1985;116:509–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ronai Z. Glycolytic enzymes as DNA binding proteins. Int J Biochem 1993;25:1073–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshall MJ, Goldberg DM, Neal FE, et al. Enzymes of glucose metabolism in carcinoma of the cervix and endometrium of the human uterus. Br J Cancer 1978;37:990–01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takashi M, Haimoto H, Koshikawa T, et al. Expression of aldolaseC isozyme in renal cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1990;93:631–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ojika T, Imaizumi M, Abe T, et al. Immunochemical and immunohistochemical studies on three aldolase isozymes in human lung cancer. Cancer 1991;67:2153–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeillo JE, Jovin IS, Huang Y. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 regulatory pathway and its potential for therapeutic intervention in malignancy and ischemia. Yale J Biol Med 2007;80:51–60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horree N, van Diest PJ, van der Groep P, et al. Hypoxia and angiogenesis in endometrioid endometrial carcinogenesis. Cell Oncol 2007;29:219–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.FIGO Announcements, stages-1988 Revision Gynecol Oncol 1989;35:125 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel PS, Rawal GN, Balar DB. Combined use of serum enzyme levels as tumor markers in cervical carcinoma patients. Tumour Biol 1994;15:45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jean JC, Rich CB, Joyce-Brady M. Hypoxia results in an HIF-1-dependent induction of brain-specific aldolaseC in lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;291:L950–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Wang D, Kesterson J, et al. Gene expression profiles in stage I uterine serous carcinoma in comparison to grade 3 and grade 1 stage I endometrioid adenocarcinoma. PLoS One 2011;6:e18066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Wang D, Kesterson J, et al. Microarray analysis reveals distinct gene expression profiles among different tumor histology, stage and disease outcomes in endometrial adenocarcinoma. PLoS One 2010;5:e15415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Wang D, Kesterson J, et al. Aldolase mRNA expression in endometrial cancer and the role of clotrimazole in endometrial cancer cell viability and morphology. Histopathology 2011;59:1015–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seeber LMS, Horree N, Voojis MA, et al. Necrosis related HIF-1a expression predicts prognosis in patients with endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2010;10:307–3118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.