Abstract

Objectives

Structured methods to assess and support improvement in the quality of end-of-life care are lacking and need to be developed. This need is particularly high outside the specialised palliative care. This study examines whether participation in a national quality register increased the quality of end-of-life care.

Design

This study is a cross-sectional longitudinal register study.

Setting

The Swedish Register of Palliative Care (SRPC) collects data about end-of-life care for deaths in all types of healthcare units all over Sweden. Data from all 503 healthcare units that had reported patients continuously to the register during a 3-year period were analysed.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Data on provided care during the last weeks of life were compared year-by-year with logistic regression.

Participants

The study included a total 30 283 patients. The gender distribution was 54% women and 46% men. A total of 60% of patients in the study had a cancer diagnosis.

Results

Provided end-of-life care improved in a number of ways. The prevalence of six examined symptoms decreased. The prescription of ‘as needed’ medications for pain, nausea, anxiety and death rattle increased. A higher proportion of patients died in their place of preference. The patient's next of kin was more often offered a follow-up appointment after the patient's death. No changes were seen with respect to providing information to the patient or next of kin.

Conclusions

Participation in a national quality register covariates with quality improvements in end-of-life care over time.

Article summary.

Article focus

Does participation in a quality register that focus on end-of-life issues improve the provided care?

Key messages

-

During a period of 3 years, the participating units improved end-of-life care by:

Decreasing the prevalence of six examined symptoms.

Increasing the prescription of as needed medications for pain, nausea, anxiety and death rattle.

Increasing the proportion of patients dying in their place of preference and the proportion of next of kin offered a follow-up appointment after the patient's death.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Strengths include the number of included patients is large (30.283 patients).

Patients are included without exclusions.

The study illustrates the potentially beneficial effects on end-of-life care by participation in a quality register.

This study cannot prove causation, only correlation between participation and improved care.

Registry data are retrospectively reported by staff.

Response shift and impact from society could not be excluded.

Introduction

Structured methods to assess and support improvement in the quality of end-of-life care are lacking and need to be developed. Approximately 91 000 people die annually in Sweden,1 which corresponds to about 1% of the Swedish population. About 80% of all deaths are ‘non-sudden’, implying potential need for palliative care.2 In Sweden, approximately 7–8% of dying patients were cared for in specialised palliative care and approximately 40–50% of dying patients were cared for in nursing homes and short-term care homes.1 There is still a need to develop end-of-life care in many areas. Data from the Swedish Register of Palliative Care (SRPC) show that end-of-life care has the potential for further improvement especially in care not provided by specialised palliative care units.1

As of 2011, there are 89 national quality registers in Sweden that are financed by Swedish local authorities and regions. Quality registers enable monitoring of care quality, quality care improvement and clinical research. Sweden has unique opportunities for quality registers because Sweden has comprehensive population registers and unique personal identification numbers. As early as 1975, the first quality register in Sweden—the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register—started. Many quality registers focus on specialised care and specific treatments, but in recent years they have also begun to address a broader patient population, including dying people. The SRPC is an example of this type of register. Swedish local authorities and regions invest in quality registers that focus on the elderly with multiple diseases, including SRPC.3 4

Several studies on improvement of quality in palliative care or end-of-life care have been published. Preliminary results using benchmarks to develop palliative care in Catalonia have been presented.5 In North Carolina (USA), a project for developing a regional database for community-based palliative care has been established.6 In an Australian national project, data are collected about cancer patients that have been referred to hospices/palliative care.7 In addition, the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) for the dying patient has been used in several studies and settings to improve end-of-life care. A multicentre study including hospital wards, palliative nursing homes, regular nursing homes and home care showed that the use of LCP improved symptom alleviation and increased documentation of end-of-life care issues.8 Another study showed that the use of LCP in a hospital improved staff knowledge about physical symptom management and increased awareness of problems related to end-of-life care.9 A method based on LCP was shown to improve end-of-life care in emergency medicine.10

Several studies have used register work to improve various areas including stroke, myocardial infarction, cardiac rehabilitation, trauma and in vitro fertilisation,11–15 but no studies reporting nationwide quality registers with effect on end-of-life care quality were found. This study examines whether participation in the SRPC during a 3-year period (from May 2007 to April 2010) increased the quality of palliative care regarding eight predetermined quality indicators of good end-of-life care such as symptom alleviation and information provided to patient and next of kin.

Methods

Since 2005, the SRPC, one of the Swedish national quality registers, has been measuring the quality of end-of-life care.4 During 2010, 34.5% of all deaths nationwide were reported to the register.1 Data are collected through a questionnaire with items based on different essential aspects of end-of-life care as proposed by British Geriatrics Society.16 Items concern providing information to patients and next of kin, alleviating pain and other distressing symptoms, prescribing necessary drugs and fulfilling the wish of preferred place of death. The online questionnaire is answered by the responsible nurse and/or physician as soon as a patient dies (see supplementary material for a translated version of the questionnaire). All questions have to be answered before submission, leading to no missing data. Deaths are reported to the register from all types of healthcare units. Descriptive data are published continuously on the register website (http://www.palliativ.se). The individual healthcare unit has continuous access to its own results online and can use this as a basis for self-improvement.

The version of the questionnaire that was used to collect data was launched in May 2007. Data from May 2007 to April 2010 were used in this study. To examine change over time, only data from the healthcare units that had reported patients in all 3 years were used. Some units reported patients who eventually died at another type of unit, but since the aim of this study was to examine the effect of using the register on the healthcare units and the palliative care provided, these patients were not included in the study. Eleven healthcare units changed their unit type during the study period. These 11 units are characterised as they were defined at the baseline and these are the characteristics used in the results section and in the tables.

Data were compared year-by-year to examine if there was a systematic change in the answers, indicating a possible change in the quality of end-of-life care. The questionnaire contains 27 questions. Eight of these questions are about the provided care in the last few weeks of life and were analysed. The remaining 16 questions (not analysed) cover background information, social demographics and patient characteristics. Each alternative of the eight questions were analysed separately. Time (the chosen 3-year period) was the only independent variable. The eight items analysed in the study (dependent variables) included the following: information provided to the patient about imminent death; information provided to next of kin of the imminent death; whether six symptoms were fully alleviated during the last week of life; whether ‘as needed’ medications in the form of injections for pain, nausea, anxiety and death rattle were prescribed at least one day before death; whether the patient had pressure ulcers (graded from 1 to 4 according to the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel) during the last week of life; whether next of kin and/or staff was present at the moment of death; whether the place of death corresponded to the patient's last spoken wish and whether next of kin were offered a follow-up appointment after death of the patient. Further details about the questions are presented in the supplementary material.

Data were analysed using logistic regression in the statistic program Stata V.11.0 from StataCorp LP. Subgroup analyses for the five most common places of death were performed. Statistical analyses of significant differences in effect size between different healthcare unit types were not performed. In the analysis of the item concerning information to the patient, only patients without cognitive impairment were included. Cognitive impairment was defined as present when the patient was registered as having lost the ability of self-determination weeks before death or earlier. In the two questions about information, information from the doctor was emphasised because physician participation was deemed most essential. In question number 19 (pressure ulcers), the ulcers are graded from 1 to 4 according to the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel.17 p Values below 0.05 were considered significant. This study was approved by the ethics committee at Umeå University, Sweden.

Results

A total of 30 283 patients reported by 503 healthcare units were included in this study. Table 1 shows detailed information of the total number of patients, the number of patients with cancer diagnoses, the distribution of women and men and the number of patients with cognitive impairment. Some aspects of the care in specialised palliative units were high at baseline (see tables 2 and 3). In specialised palliative home care, 94% of the patients died at their preferred place of death, 97% of the patients’ next of kin were offered a follow-up appointment and 93% of the patients had ‘as needed’ pain medication prescribed. In hospices/palliative hospital wards, 92% of the next of kin were offered a follow-up appointment, 98% of the patients were given ‘as needed’ medication prescription, 95% of the patients were given anxiety medication and 92% of the patients were given death rattle medication.

Table 1.

Detailed information of the patients in this study

| Place of death | Year 1 (n/% of year total) | Year 2 (n/% of year total) | Year 3 (n/% of year total) | Total (n/%=) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (503 units) | ||||

| Patients | 7584 | 11409 | 11290 | 30283 |

| With cancer | 63% | 58% | 60% | 18238 (60%) |

| Cognitively impaired* | 21% | 22% | 19% | 6354 (21%) |

| Women | 54% | 54% | 54% | 16342 (54%) |

| Men | 46% | 46% | 46% | 13941 (46%) |

| Hospice/palliative hospital ward (39 units) | ||||

| Patients | 2948 | 3739 | 3793 | 10480 |

| With cancer | 95% | 94% | 93% | 9832 (94%) |

| Cognitively impaired* | 11% | 8% | 8% | 938 (9%) |

| Women | 51% | 53% | 52% | 5480 (52%) |

| Men | 49% | 47% | 48% | 5000 (48%) |

| Nursing home (233 units) | ||||

| Patients | 1628 | 2691 | 2488 | 6807 |

| With cancer | 11% | 11% | 12% | 778 (11%) |

| Cognitively impaired* | 51% | 54% | 48% | 3484 (51%) |

| Women | 64% | 64% | 63% | 4359 (64%) |

| Men | 36% | 36% | 37% | 2448 (36%) |

| Specialised palliative home care (60 units) | ||||

| Patients | 1097 | 1532 | 1704 | 4333 |

| With cancer | 91% | 90% | 89% | 3887 (90%) |

| Cognitively impaired* | 6% | 8% | 6% | 298 (7%) |

| Women | 47% | 49% | 47% | 2061 (48%) |

| Men | 53% | 51% | 53% | 2272 (52%) |

| Hospital ward, not palliative (88 units) | ||||

| Patients | 1333 | 2456 | 2292 | 6081 |

| With cancer | 45% | 40% | 41% | 2507 (41%) |

| Cognitively impaired* | 19% | 20% | 19% | 1195 (20%) |

| Women | 51% | 51% | 53% | 3144 (52%) |

| Men | 49% | 49% | 47% | 2937 (48%) |

| Short-term care home (56 units) | ||||

| Patients | 508 | 856 | 869 | 2233 |

| With cancer | 42% | 48% | 52% | 1071 (48%) |

| Cognitively impaired* | 24% | 15% | 15% | 479 (21%) |

| Women | 54% | 49% | 49% | 1117 (50%) |

| Men | 46% | 51% | 51% | 1116 (50%) |

| Basal home care (27 units) | ||||

| Patients | 70 | 135 | 144 | 349 |

*Reported to have lost their ability of self-determination weeks before death or earlier.

Table 2.

Number of patients with prescriptions for ‘as needed’ medication for pain, death rattle, nausea and anxiety during the last day of life

| Total | Nursing home | Short-term care home | Hospital ward, not palliative | Hospice/palliative hospital ward | Specialised palliative home care | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain medication ‘as needed’ prescribed | 89%→90% | 78%→83% | 83%→88% | 79% → 81% | 98%→99% | 93%→94% |

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p=0.012 | p=0.001 | NS | NS | |

| Death rattle medication ‘as needed’ prescribed | 80%→83% | 72%→78% | 76%→81% | 60%→69% | 92%→94% | 84%→89% |

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | NS | p<0.001 | p=0.008 | p<0.001 | |

| Nausea medication ‘as needed’ prescribed | 55%→82% | 24%→74% | 30%→78% | 28%→67% | 83%→94% | 71%→88% |

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | |

| Anxiety medication ‘as needed’ prescribed | 78%→82% | 61%→69% | 65%→76% | 59%→69% | 95%→96% | 88%→91% |

| p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | NS | p=0.005 |

NS, not significant.

Table 3.

Changes during the study years shown for total and divided into the five subgroups regarding preferred place of death, information to patient and next of kin, presence at the moment of death and follow-up appointment offered

| Total | Nursing home | Short-term care home | Hospital ward, not palliative | Hospice/palliative hospital ward | Specialised palliative home care | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13. Information from doctor to patient* | 58%→58% | 16%→17% | 29%→37% | 39%→39% | 75%→78% | 76%→81% |

| NS | NS | p=0.022 | NS | p=0.007 | p=0.005 | |

| 14. Information from doctor to next of kin | 70%→71% | 33%→31% | 53%→62% | 73%→73% | 88%→91% | 85%→87% |

| NS | NS | p=0.004 | NS | p<0.001 | NS | |

| 21. No one present at the moment of death | 15%→15% | 15%→14% | 18%→15% | 25%→22% | 14%→16% | 6%→6% |

| NS | NS | NS | p=0.007 | NS | NS | |

| 22. Place of death corresponded to preference | 48%→50% | 32%→35% | 21%→33% | 13%→12% | 60%→66% | 94%→94% |

| p=0.001 | p=0.020 | p<0.001 | NS | p<0.001 | NS | |

| 24. Next of kin offered follow-up appointment | 72%→74% | 54%→63% | 38%→70% | 42%→39% | 92%→94% | 97%→96% |

| p=0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | NS | NS | NS |

Question number from the end-of-life questionnaire is shown.

*Only including patients without cognitive impairment.

NS, not significant.

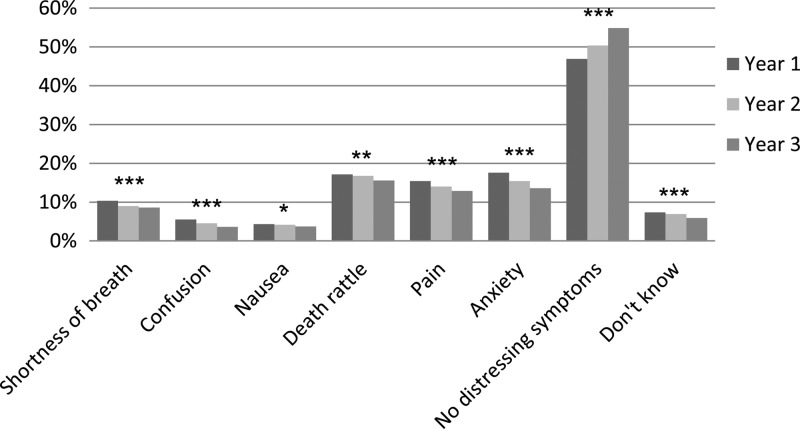

The prevalence of not fully alleviated symptoms (question number 17) during the study years is presented in figure 1. During the first study year, the prevalence of distressing symptoms was 10% for shortness of breath, 6% for confusion, 4% for nausea, 17% for death rattle, 15% for pain and 17% for anxiety. Reductions in prevalence were seen over time for all symptoms. No decrease in symptoms was seen at nursing homes. Hospital wards (not palliative) showed decrease for pain only, while the other types of care units showed decreases in three or more symptoms.

Figure 1.

Question number 17 from the end-of-life questionnaire: Mark the symptom(s) that was/were not fully alleviated during the last week of life. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 and n=7584–11 409 per year.

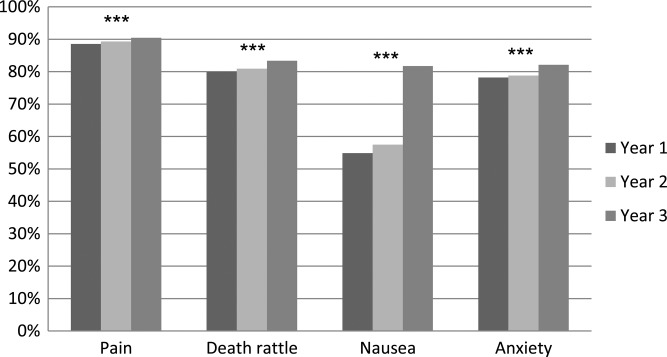

The item concerning prescription of ‘as needed’ drugs at least 1 day before death (question number 20) is presented in figure 2 and table 2. Prescriptions against all four symptoms increased significantly. The largest increase was seen for ‘as needed’ drugs against nausea, from 55% to 82% of the patients. Prescriptions against nausea increased significantly in all types of care units. Nursing homes and hospital wards (not palliative) showed an increase in ‘as needed’ prescriptions for all registered symptoms.

Figure 2.

Question number 20 from the end-of-life questionnaire: Was ‘as needed’ medication prescribed in the form of injections at least 1 day before death against pain, anxiety, death rattle and/or nausea? ***p<0.001 and n=7584–11 409 per year.

The item whether someone was present at the time of death (question number 21) is presented in table 3. The proportion of patients dying alone did not change overall. However, a decrease was seen in hospital wards (not palliative). The item concerning whether the place of death corresponded to the patient's last spoken wish (question number 22) is presented in table 3. There was a significant trend towards more patients dying in their preferred place of death. A significant trend towards more next of kin being offered follow-up appointments after death of the patient (question number 24) was seen (table 3).

No improvements were seen over time regarding prevalence of pressure ulcers (question number 19; see table 4). On the contrary, the total number of patients with pressure ulcers grade 1 (graded according to the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel) increased from 9.1% to 10.2%. The number of patients with higher grades of pressure ulcers was unchanged.

Table 4.

Presence of pressure ulcers during the last week of life.

| Total | |

|---|---|

| Pressure ulcer grade 1 | 9%→10% |

| p=0.016 | |

| Pressure ulcer grade 2 | 5%→6% |

| NS | |

| Pressure ulcer grade 3 | 3%→3% |

| NS | |

| Pressure ulcer grade 4 | 2%→2% |

| NS | |

| No pressure ulcer | 79%→77% |

| p=0.006 | |

| Do not know if patient had pressure ulcer | 3%→2% |

| NS |

No important changes were seen regarding providing information to patients about their imminent death (question number 13) or information to next of kin about the patient's imminent death (question number 14; table 3). No changes were seen when examining the information given by doctors.

Discussion

We have found by following structured assessment of end-of-life care using a national quality register that palliative care improved in several aspects, implying that the structured assessment itself may have contributed to the improvements. Large improvements were seen in the prevalence of distressing symptoms during the last week of life and prescription of ‘as needed’ medication for symptom alleviation. The large number of included patients strengthens these findings.

Even if causality cannot be proven, the regular use of SRPC covariates with the seen improvements. By providing clear lists of important care activities and an opportunity to evaluate each care episode it is not unlikely that the SRPC use has contributed to this improvement. The principal nurse, or sometimes the principal doctor, via registration of each deceased patient had the opportunity to comprehensively evaluate that patient's end-of-life care. Furthermore, the possibility of immediate web-generated feedback from the SRPC with detailed diagrams illustrating the results over time produced by the reporting care unit compared to similar care units nationwide provides a unique possibility to identify the care activities in most urgent need of improvement. We believe it is likely that these SRPC-generated activities over a 3-year period have influenced the provided end-of-life care in the desired direction. To a certain extent, the identified improvements could also be due to better documentation and/or staff awareness, both positively contributing to enhanced continuity in care and validity of collected data. The consequent positive direction of the observed changes and that all involved units were unaware of this study lessen the risk for systemic bias.

The results of this study also confirm that the SRPC as a register is widely applicable in all kinds of care units where end-of-life care is provided and that the potential for improvements are more pronounced outside specialised palliative care. As the coverage of SRPC within specialised palliative units is estimated to be close to 100%, we assume that approximately 7–8% of dying patients nationwide receive end-of-life care at specialised palliative units. Accordingly, the vast majority (about 70%) of the population has to rely on hospital wards, nursing homes and non-specialised home care for their end-of-life care. If the use of SRPC in these care contexts can contribute to measurable improvements of end-of life care, the potential impact over time may be immense.

The trend that more patients were prescribed 'as needed’ medications for symptom alleviation is encouraging. The level of nausea medication prescription is approaching the prescription levels for the other three symptoms. Only having a prescription for ‘as needed’ medication does not necessarily mean that the patient suffers less from symptoms, but an adequate prescription is most often a prerequisite for providing immediate relief from symptoms. The trend that lower grade of pressure ulcers increased during the study years does not necessarily mean that pressure ulcers increased. The increase of lesser degree pressure ulcers may be a sign of increased staff awareness.

The widely differing prevalence of cancer (11–94%) and cognitive impairment (7–51%) between different unit types illustrates that they represent different patient populations. These different case-mixes imply different challenges considering end-of-life care and disqualify direct comparisons between different unit types. Hospital wards have probably the most varied patient selections and many of these are resource consuming. Nursing homes and short-term care homes showed marked improvement. The specialised palliative care units performed well in many items leaving limited room for further improvements. For this reason, it is likely that a similar study including only healthcare units without palliative specialisation could have shown greater overall improvements.

There are some methodological weaknesses with this study. Since the questionnaires are answered retrospectively, recall bias could have affected the results. It is, however, unlikely that recall bias alone could have given systematic positive changes over time. The results could possibly also be affected by a change in interpretation of answering alternatives, the response shift. Although the use of output register data for evaluation at the units is one of the potential mechanisms for the improvement caused by SRPC, this study did not examine to what extent this has been done during the study period. We cannot say how much of the positive changes seen in this study were the result of participating in SRPC. A number of possible factors could have affected the results. The contributions of each are not possible to identify by this study. In addition to the work of the SRPC, the change in society during the study years cannot easily be measured. There has been an increased focus on end-of-life care and the dying process in medicine and in public discourse, but neither of these has been measured in this study. During the studied years, no national healthcare programmes on palliative medicine or palliative care have been launched, but some local areas have started their own palliative programmes. This could also have influenced the participating units.

How many patients do not want to die alone or who these patients want to be with at the time of their death was not found in the literature. According to a Swedish report, many health professionals think that a dignified death means not dying alone.18 One study found that 87% of terminally ill cancer patients wished to die at home.19 Another study including patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumonia found that only 43% preferred to have terminal care at home, while 48% preferred hospitals.20 The litterature is consistent with the finding in this study that almost all patients in specialised palliative home care (91% cancer patients) died in their preferred place of death. Some patients are not able to communicate their wishes. Almost half of the patients with unknown wishes could represent those who lost their ability of self-determination weeks before death or earlier (table 1). The other half of those with unknown wishes were probably able to declare their preference if asked. The proportion of patients dying at a place they did not prefer could be close to its possible limit because it is probably inevitable that a small proportion of patients cannot have their wishes fulfilled.

Although the presented data show that palliative care has improved over the years, there is still potential for further improvement. A regular monitoring of provided end-of-life care enables continuous feedback and constructive discussions for further improvements. Registrations in the SRPC can probably only increase the quality to some extent, as the results suggest. More studies are needed to investigate the possibility of quality improvement in end-of-life care with more extensive actions. It is possible that additional improvements can be achieved with the help of SRPC by combining questionnaire collecting with information to and training for concerned healthcare professionals and/or prospective use end-of-life care pathways (eg, Liverpool Care Pathway for the dying patient). Other ways to collect data on patients in end-of-life care should also be reviewed, such as designing a similar questionnaire to be answered by patients in palliative care or by their next of kin. Methods to promote greater use of evaluation of registry data at the individual units are also options that should be reviewed. Regardless of which means are used to accomplish better end-of-life care, results in SRPC can be an easy and efficient way to monitor improvements and identify areas that need further attention.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LM contributed to conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the article. CJF contributed to conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critically revising article. SL contributed to conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, critically revising article. LN analysed and intrepretated data, critilally revising article. BA contributed to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the article. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: Swedish Register of Palliative Care.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The Ethical Committee in Umeå, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.The Swedish Register of Palliative Care (Annual report from the Swedish Register of Palliative Care fiscal year 2010.) http://www.palliativ.se/html/sve/Arsrapport/Palliativregistret2011.pdf (accessed 1 Jul 2011).

- 2.Socialstyrelsen (Causes of death 2008.) Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosén M. (Review of national quality registers. Gold mine in care. Proposal for a joint initiative from 2011 to 2015.) http://brs.skl.se/brsbibl/kata_documents/doc39859_1.pdf (accessed 23 Jun 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lundström S, Axelsson B, Heedman P-A, et al. Developing a national quality register in end-of-life care: the Swedish experience. Palliat Med 2012;26:313–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gómez-Batiste X, Caja C, Espinosa J, et al. Quality improvement in palliative care services and networks: preliminary results of a benchmarking process in Catalonia, Spain. J Palliat Med 2010;13:1237–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bull J, Zafar Y, Wheeler JL. Establishing a regional, multisite database for quality improvement and service planning in community-based palliative care and hospice. J Palliat Med 2010;13:1013–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Currow DC, Eagar K, Aoun S, et al. Is it feasible and desirable to collect voluntarily quality and outcome data nationally in Palliative Oncology Care? J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3853–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veerbeek L, van Zuylen L, Swart SJ, et al. The effect of the Liverpool Care Pathway for the dying: a multi-centre study. Palliat Med 2008;22:145–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Leo S, Beccaro M, Finelli S, et al. Expectations about and impact of the Liverpool Care Pathway for the dying patient in an Italian hospital. Palliat Med 2011;25:293–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paterson BC, Duncan R, Conway R, et al. Introduction of the Liverpool Care Pathway for end of life care to emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 2009;26:777–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Use of a Registry to Improve Acute Stroke Care—Seven States, 2005−2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:206–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson ED, Roe MT, Chen AY, et al. The NCDR ACTION Registry—GWTG: transforming contemporary acute myocardial infarction clinical care. Heart 2010;96:1798–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chauhan U, Baker D, Edwards R, et al. Improving care in cardiac rehabilitation for minority ethnic populations. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2010;9:272–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakahara S, Ichikawa M, Kimura A. Simplified alternative to the TRISS method for resource-constrained settings. World J Surg 2011;35:512–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart LM, Holman CD, Hart R, et al. How effective is in vitro fertilization, and how can it be improved? Fertil Steril 2011;95:1677–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.British Geriatrics Society Palliative and End of Life Care of Older People, BGS Compendium Document 4.8, 2004. Revised in September 2006

- 17.Beeckman D, Schoonhoven L, Fletcher J, et al. EPUAP classification system for pressure ulcers: European reliability study. J Adv Nurs 2007;60:682–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swedish (Death concerns us all—dignified care at the end of life.) Stockholm: Fritze, 2001. SOU 2001:6 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang ST. When death is imminent: where terminally ill patients with cancer prefer to die and why. Cancer Nurs 2003;26:245–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fried TR, van Doorn C, O'Leary JR, et al. Older persons’ preferences for site of terminal care. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:109–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.