Abstract

Objectives

To analyse coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality and risk factor trends in the West Bank, occupied Palestinian territory between 1998 and 2009.

Design

Modelling study using CHD IMPACT model.

Setting

The West Bank, occupied Palestinian territory.

Participants

Data on populations, mortality, patient groups and numbers, treatments and cardiovascular risk factor trends were obtained from national and local surveys, routine national and WHO statistics, and critically appraised. Data were then integrated and analysed using a previously validated CHD model.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

CHD deaths prevented or postponed are the main outcome.

Results

CHD death rates fell by 20% in the West Bank, between 1998 and 2009. Smoking prevalence was initially high in men, 51%, but decreased to 42%. Population blood pressure levels and total cholesterol levels also decreased. Conversely, body mass index rose by 1–2 kg/m2 and diabetes increased by 2–8%. Population modelling suggested that more than two-thirds of the mortality fall was attributable to decreases in major risk factors, mainly total cholesterol, blood pressure and smoking. Approximately one-third of the CHD mortality decreases were attributable to treatments, particularly for secondary prevention and heart failure. However, the contributions from statins, surgery and angioplasty were consistently small.

Conclusions

CHD mortality fell by 20% between 1998 and 2009 in the West Bank. More than two-third of this fall was due to decreases in major risk factors, particularly total cholesterol and blood pressure. Our results clearly indicate that risk factor reductions in the general population compared save substantially more lives to specific treatments for individual patients. This emphasizes the importance of population-wide primary prevention strategies.

Keywords: Cardiology, Cardiac Epidemiology, Cardiology, Myocardial infarction, Epidemiology, Public Health, Surgery, Cardiac surgery

Key points.

CHD mortality fell by 20% between 1998 and 2009 in the West Bank.

More than two-third of this fall was due to decreases in major risk factors, particularly total cholesterol, and blood pressure.

Introduction

The occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) comprises the Gaza Strip and the West Bank including East Jerusalem. Some 46% of the Palestinian population of 3.8 million are younger than 15 years while only 3% are older than 65 years. However, the number of older people is increasing gradually and the population is slowly ageing. The Palestinians are also undergoing rapid epidemiological transition. Communicable diseases of childhood have already been controlled with effective immunisation programmes, and poliomyelitis has been eradicated. However, non-communicable diseases have now overtaken communicable diseases as the main causes of mortality.1 Thus, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer are now the major causes of morbidity and mortality in the oPt.2 The Ministry of Heath (MOH) recently reported that 25% of all deaths are due to cardiovascular diseases in 2010, followed by cerebrovascular diseases (12%), cancer (11%) and diabetes (6%).3 Increasing levels of adverse risk factors such as diabetes, obesity and physical inactivity have been repeatedly documented.4 5

Chronic disease death rates are actually decreasing in the developed world (Western Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand). However, mortality is increasing in the developing countries. It is predicted that by 2020, CVD deaths will exceed infectious and parasitic disease deaths in all regions except for sub-Saharan Africa.6 Furthermore, the Eastern Mediterranean region has been recognised as a hot spot for diabetes and CVD, yet local data to inform policy is severely limited.

The IMPACT coronary heart disease (CHD) model was developed to quantify recent trends in CHD mortality, in order to help maximise the effective use of existing information and resources to develop appropriate policies and strategies. This study aims to adopt the IMPACT CHD model to the Palestinian context, namely the West Bank population, in order to help explain recent changes in CHD mortality.

Methods

A validated version of the IMPACT CHD mortality model was further modified and updated to suit the countries in the Middle East and specifically the oPt. The IMPACT model was previously validated in many developed countries7–10 and in one middle-income country (China).11

Palestinian data on risk factors levels and current uptake levels of evidence-based treatments were identified by extensive searches for published or unpublished data and complemented with specifically designed surveys. All data sources were critically appraised by the local research team and the results are presented in the appendix. The data needed for the analysis were available for men and women aged 25–75 years in the West Bank, occupied Palestinian territory for the period 1998–2009 with some age limitations as described in the appendix.

The specific data items used to populate the model included: (1) Patient numbers in specific CHD groups (myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure and chronic angina pectoris), (2) uptake of specific medical and surgical treatments, (3) population trends in major cardiovascular risk factors (smoking, total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), diabetes and physical inactivity).

The main output of the model is the number of deaths prevented or postponed attributed to the changes in specific treatments and/or risk factor levels.

Identification and assessment of relevant data

Information on the West Bank population demographic changes was obtained and validated for the first year from 1997 census-based projections and 2007 census-based projections for the final year by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS).12 Numbers of deaths for both years were obtained from the Health Information Management Centre—Palestinian Ministry of Health (MOH). Population risk factors trend data for the year 1998 were obtained from two epidemiological studies conducted in the rural and urban areas of Ramallah governorate in the West Bank. These were the only available published epidemiological studies in the West Bank for that period. They covered a rural and an urban site that were prototypic of many West Bank villages and urban sites.4 13

CHD numbers of hospital admissions in addition to treatment uptake were obtained from our treatment uptake survey conducted in 2009 which included four hospitals in the north, centre and south of the West Bank. The number of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting and angioplasty were obtained from records in the two hospitals providing this service in the West Bank. The prevalence of angina, heart attack survivors and congestive heart failure in the community were each estimated on the basis of national health surveys and treatment uptake surveys. Information on treatment uptake in the community was also checked by eliciting expert opinion from practising clinicians.

The efficacy of therapeutic interventions was based on recent meta-analyses and randomised controlled trials. The Mant and Hicks14 approach was used to correct for polypharmacy.

Change in CHD deaths

First, the number of CHD deaths expected in 2009 was calculated by indirect age standardisation based on the assumption that 1998 death rates had persisted unchanged until 2009. The number of CHD deaths actually observed in 2009 was then subtracted. The difference between the two represents the fall in CHD deaths (the number of deaths prevented or postponed) that the model needed to explain.

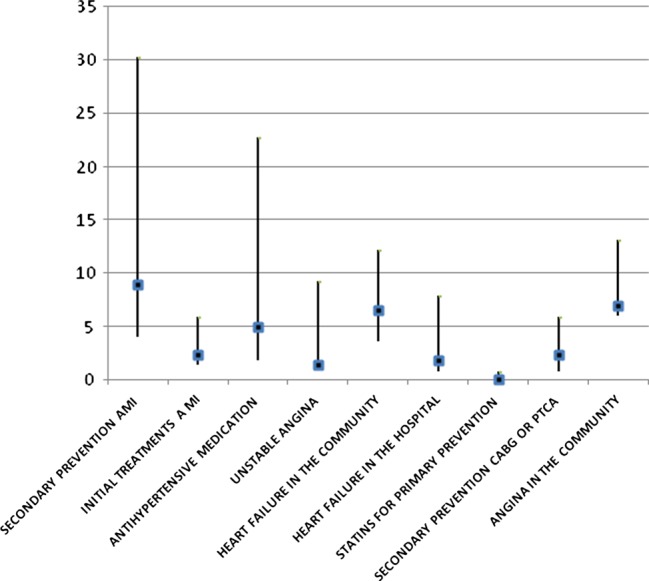

Mortality changes attributed to risk factor trends

The number of deaths prevented or postponed from changes in risk factors was estimated using two approaches. The regression β coefficients approach was used to quantify the population mortality impact of change in those specific risk factors, measured as continuous variables (blood pressure, total cholesterol and BMI). The second approach, population-attributable risk fraction, was employed for categorical variables—diabetes, physical inactivity and smoking:

|

PAR calculation was stratified by age and sex. Details of model methodology have been published previously7 and worked examples are shown in the appendix.

Estimating the contribution of medical and surgical treatments

The model aimed to include all medical and surgical treatments in 1998 (the base year) and 2009 (the final year). Treatment uptake data were not available for the year 1998 and thus the data included in the model for this year was estimated after consultation with cardiologists and experts working in hospital and community at that time.

The mortality reduction for each treatment for the number of patients in each group, stratified by age and sex, was calculated as the age-specific case death in that group multiplied by the relative mortality reduction reported in published meta-analyses multiplied by the treatment uptake (the proportion of patients receiving that specific treatment, appendix).

Case- death data were obtained from large, unselected, population-based patient cohorts. The survival benefit over a 1-year time interval was used for all treatments.

Treatment overlaps

Potential overlaps between different groups of patients were identified and appropriate adjustments were made. Patients group calculations and assumptions are detailed in the appendix.

Treatment adherence

Adherence (defined as the proportion of treated patients actually taking therapeutically effective levels of the prescribed medication) was assumed to be 100% among hospital patients, 70% among all symptomatic community patients and 50% among asymptomatic community patients, based on the literature.15

Sensitivity analyses

Because of the uncertainties surrounding some of the values, multiway sensitivity analyses using the Brigg's analysis of extremes method was used.16

Model validation: comparison with observed mortality falls

The model estimate for the changes in deaths attributed to all treatments plus all risk factor changes was summed for men and women in each specific age group. The model fit was then compared with the observed change in mortality for that group.

Results

Between 1998 and 2009 CHD mortality in the West Bank fell by 20%. This resulted in approximately 125 fewer CHD deaths compared with the expected number of CHD deaths in 2009 if 1998 death rate had persisted unchanged (table 1).

Table 1.

Population sizes and coronary heart disease death rates in the West Bank, 1998 and 2009

| Age groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | Total | |

| Men | ||||||

| Population in 1998 | 132084 | 80434 | 41727 | 28653 | 19524 | 302422 |

| Population in 2009 | 177873 | 132945 | 86399 | 41984 | 21619 | 460820 |

| Deaths in 1998 (number) | 9 | 21 | 57 | 101 | 130 | 318 |

| Deaths in 2009 (number) | 11 | 30 | 89 | 131 | 133 | 394 |

| Death rates per 100000 in 1998 | 6.4 | 26.1 | 135.4 | 350.7 | 665.8 | 105.2 |

| Death rates per 100000 in 2009 | 6.2 | 22.8 | 103.4 | 311.2 | 616.7 | 85.5 |

| Percentage of change (crude) | 0 | −12.6 | −23.6 | −11.3 | −7.4 | −19 |

| Women | ||||||

| Population in 1998 | 125493 | 76747 | 45711 | 36038 | 24445 | 308434 |

| Population in 2009 | 170942 | 127590 | 80883 | 43693 | 28424 | 451532 |

| Deaths in 1998 (number) | 5 | 9 | 22 | 59 | 107 | 202 |

| Deaths in 2009 (number) | 5 | 11 | 20 | 51 | 105 | 192 |

| Death rates per 100000 in 1998 | 3.6 | 11.1 | 48.1 | 162.3 | 437.7 | 65.5 |

| Death rates per 100000 in 2009 | 3.1 | 8.9 | 24.7 | 116.0 | 370.6 | 42.5 |

| Percentage of change (crude) | 0 | −19.8 | −48.6 | −28.6 | −15.3 | −35 |

The reduction in CHD mortality among women (35%) was twice as large as the 19% reduction observed among men. The CHD mortality reduction was seen in all age groups with particularly large reductions being observed among those aged 45–54 years, men (24%) and women (49%).

Major CHD risk factors

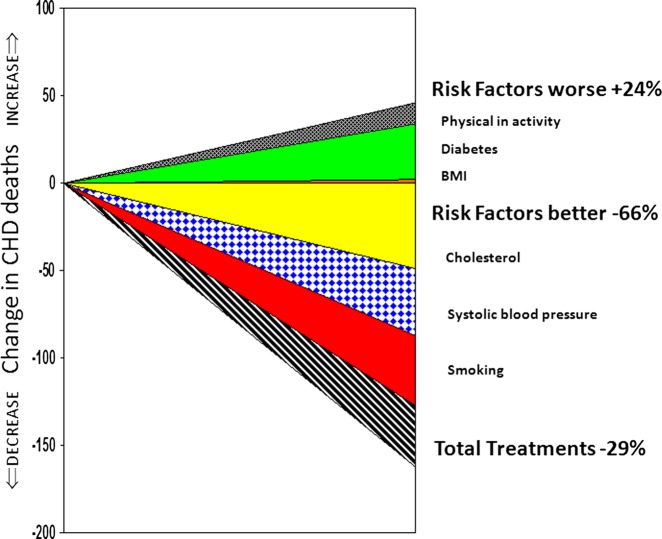

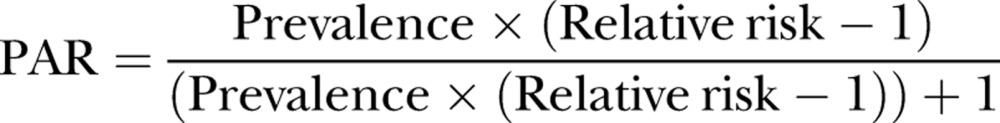

Changes in cardiovascular risk factors included in the model were together estimated to prevent or postpone approximately 80 deaths in 2009 (minimum estimate 75 and maximum estimate 140), which represented approximately 66% of the total CHD mortality fall (figure 1).Table 2 presents changes in the selected risk factors and the attributed deaths. Changes in risk factors were complex: reduction in total cholesterol (mean reduction 0.34mmol/l in men and 0.22 mmol/l in women), blood pressure (5.27 mm Hg in men and 0.01 mm Hg in women) and in smoking prevalence (11.5% in men and 2.2% in women). These changes together prevented or postponed approximately 125 deaths (table 2). A total fall of 40% in CHD deaths were thus attributable to cholesterol reduction (minimum 38% and maximum 77%), and 36% to blood pressure reduction (minimum 30% and maximum 50%) and 33% to smoking reduction (minimum 22% and maximum 49%). However, an additional 45 deaths were attributable to adverse trends (figure 2). Mainly an increase in diabetes prevalence (8.5% in men and 2% in women) generated approximately 30 additional deaths. The mortality effects of increases in physical inactivity and mean BMI were relatively modest (table 2).

Figure 1.

Coronary heart disease deaths prevented or postponed by treatment and risk factor changes in the West Bank population between 1998 and 2009.

Table 2.

Deaths attributable to population risk factor changes in the West Bank between 1998 and 2009

| Risk factors | Risk factor levels | Absolute change in risk factor 1998–2009 | Relative risk (or β coefficient) | Deaths prevented or postponed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 2009 | Best estimate | Minimum estimate | Maximum estimate | Proportion of overall deaths (%) | |||

| Cholesterol (total) (mmol/l) | 49 | 46 | 94 | −40.3 | ||||

| Cholesterol (men) | 5.37 | 5.03 | 0.34 | βετα 0.65 | ||||

| Cholesterol (women) | 5.25 | 5.03 | 0.22 | βετα 0.65 | ||||

| Smoking (total) (%) | 40 | 26 | 59 | −32.5 | ||||

| (% men smoking) | 51.5 | 40 | 11.5 | |||||

| (% women smoking) | 5.5 | 3.3 | 2.2 | |||||

| Body mass index (BMI) (total) (kg/m2) | −2 | −2 | −5 | −2 | ||||

| BMI (men) | 26.95 | 30.88 | −3.93 | βετα 0.02 | ||||

| BMI (women) | 29.12 | 30.99 | −1.87 | βετα 0.02 | ||||

| Diabetes (total) % | −32 | −27 | −60 | 26.2 | ||||

| Percentage of diabetes (men) | 9.1 | 17.6 | −8.5 | 2 | ||||

| Percentage of diabetes (women) | 12.4 | 14.4 | −2 | 2 | ||||

| Population systolic blood pressure (BP) (total) mm Hg | 43 | 39 | 84 | −35.6 | ||||

| Population BP (men) | 125.57 | 120.3 | 5.27 | βετα 0.053 | ||||

| Population BP (women) | 118.44 | 118.45 | −0.01 | βετα a0.053 | ||||

| Population BP after adjustment for hypertension treatments | 38 | 37 | 61 | −31.5 | ||||

| Physical inactivity | −12 | −8 | −17 | 9.7 | ||||

| Percentage of physical inactivity men | 79.3 | 91.3 | 12 | |||||

| Percentage of physical inactivity women | 87.9 | 93 | 5.1 | |||||

| Estimated total risk factor effects | 81 | 73 | 138 | −66.5 | ||||

Figure 2.

Coronary heart disease deaths prevented or postponed attributable to specific risk factor changes in Palestine 1998–2009: Sensitivity analysis (▪, best estimate; bars indicate minimum and maximum estimates).

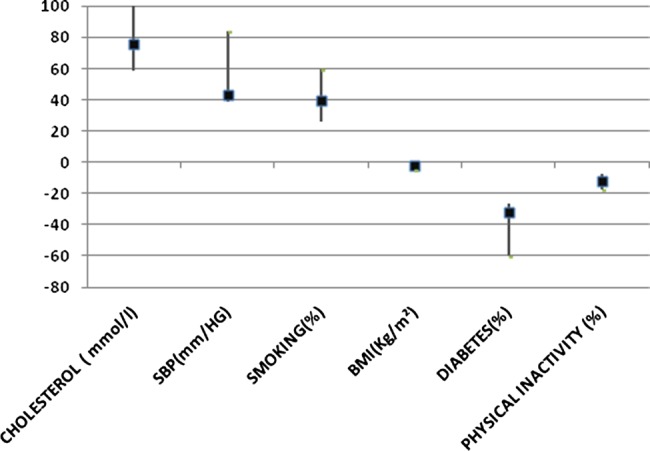

Medical and surgical treatments

Medical and surgical treatments together prevented or postponed approximately 35 deaths in 2009 (minimum estimate 20 and maximum estimate 108; figure 3). The total treatments thus accounted for approximately 29% (minimum 17% and maximum 82%) of the total CHD mortality reduction (table 3). Secondary prevention following acute MI explained over 7% (minimum 3% and maximum 25%) of deaths prevented or postponed (with ACE inhibitors, aspirin and β-blockers and β-blockers being the main contributors in this group; table 3). Smaller contributions came from chronic angina treatment (6%, minimum 5% and maximum 11%) and heart failure treatment in the community (5%, minimum 3% and maximum 10%) and hypertensive treatment in the community (4%, minimum 1% and maximum 19%). Secondary prevention postrevascularisation had a very modest effect on CHD mortality reduction with a contribution of 2% (minimum 1% and maximum 5%; table 3).

Figure 3.

Coronary heart disease deaths prevented or postponed attributable to specific treatments in Palestine 1998–2009: Sensitivity analysis (▪, best estimate; bars indicate minimum and maximum estimates).

Table 3.

Deaths prevented or postponed by medical and surgical treatments in the West Bank in 2009

| Coronary heart disease deaths prevented or postponed | Proportion of overall deaths prevented or postponed (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Patients eligible | Treatment uptake (%) | Best estimate | Minimum estimate | Maximum estimate | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 489 | 2 | 1 | 6 | −1.9 | |

| Hospital resuscitation | 0.06 | 0 | 0 | 1 | −0.3 | |

| Thrombolysis and aspirin | ||||||

| Aspirin alone | 0.90 | 5 | 2 | 9 | −3.8 | |

| Thrombolysis alone | 0.39 | 3 | 1 | 6 | −2.4 | |

| β-Blockers | 0.58 | 1 | 0 | 2 | −0.6 | |

| ACE inhibitors | 0.44 | 1 | 0 | 2 | −1 | |

| Secondary preventionpostinfarction | 2266 | 9 | 4 | 30 | −7.4 | |

| Aspirin | 0.483 | 4 | 1 | 9 | −2.9 | |

| β-Blockers | 0.388 | 4 | 1 | 11 | −3.6 | |

| Aspirin and β-blockers | 0.415 | 4 | 1 | 10 | −3.4 | |

| ACE inhibitors | 0.472 | 5 | 2 | 13 | −4.2 | |

| Statins | 0.046 | 0 | 0 | 1 | −0.4 | |

| Warfarin | 0.100 | 1 | 0 | 3 | −0.9 | |

| Rehabilitation | 0.483 | 1 | 0 | 3 | −0.9 | |

| Secondary preventionpostrevascularisation | 208 | 2 | 0 | 6 | − 1.9 | |

| Angina | 7 | 6 | 13 | −5.7 | ||

| Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting surgery (2004–2005) | 208 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 10 | −4.6 |

| Aspirin in the community | 22180 | 0.47 | 15 | 13 | 40 | −12.7 |

| Statin in the community | 22180 | 0.46 | 20 | 11 | 50 | −16.8 |

| Unstable angina | 489 | 1 | 2 | 9 | −1.1 | |

| Heart failure | 2811 | |||||

| Hospital patients | 468 | −2 | −1 | −8 | −1.5 | |

| Community patients | 2342 | −7 | −4 | −4 | −5.4 | |

| Hypertension treatments | −5 | −2 | −23 | −4.1 | ||

| Total treatment effects | 35 | 20 | 108 | 29 | ||

Validation and model fit

In summary, when including all risk factor and treatment data, the model explained approximately 95% of the total CHD mortality reduction observed in the West Bank population between 1998 and 2009. The remaining 5% was unexplained and might reflect other, unmeasured factors. The model estimates of deaths were reasonably consistent with the observed deaths for almost all age groups. Overall, the model fit was better for men than for women. However, in the age group 45–54 the model overestimated deaths in men and women (table 4). Moreover, irrespective of whether best minimum or maximum estimates were used, the relative contributions remained relatively consistent.

Table 4.

Model validation: estimated versus observed changes in coronary heart disease (CHD) deaths between 1998 and 2009

| Age groups | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | 65–74 | Total | |

| Men | ||||||

| Estimated fall in CHD deaths | 11 | 35 | 117 | 147 | 144 | 454 |

| Observed fall in CHD deaths | 11 | 30 | 89 | 131 | 133 | 394 |

| Discrepancy | 0 | −5 | −28 | −16 | −11 | −60 |

| Estimated fall/ observed fall in CHD deaths (%) | 100 | 117 | 131 | 112 | 108 | 115 |

| Women | ||||||

| Estimated fall in CHD deaths | 6 | 14 | 39 | 71 | 124 | 254 |

| Observed fall in CHD deaths | 5 | 11 | 20 | 51 | 105 | 192 |

| Discrepancy | −1 | −3 | −19 | −20 | −19 | −62 |

| Estimated fall/observed fall in CHD deaths (%) | 120 | 127 | 195 | 139 | 118 | 132 |

Discussion

CHDs mortality decreased by 20% in the West Bank, oPt between 1998 and 2009. Almost two-thirds of this reduction was attributable to changes in major risk factors and approximately one-third was explained by medical and surgical treatments. The recent mortality trends observed in the West Bank were thus characterised by reductions in CHD mortality similar to those observed in the developed rather than developing countries. Other studies have documented similar reductions in CHD mortality in Europe, North America and New Zealand especially since the 1980s.7 8 17 18

The biggest CHD mortality reductions attributable to changes in major risk factors came from declines in total cholesterol and smoking, and also blood pressure in men. Interestingly, the implementation efforts of an antismoking law in 2005 might have contributed to the substantial declines in smoking prevalence.19 20

However, the increasing Westernisation of diet, particularly junk food and soda represent an ominous future threat. Furthermore, diabetes, obesity and physical inactivity increased substantially between 1998 and 2009.21–23 In the year 1998, the prevalence of obesity was 49% for women and 30% for men aged 35–64 years old.24 Since then, the prevalence of obesity has increased mainly among men.25 26 The increase in diabetes prevalence generated approximately 30 additional CHD deaths. Rising diabetes and obesity, especially among men, represents a public health priority. Effective evidence-based interventions exist and should be considered, notably junk-food taxes, labelling and reformulation issues and advertising bans.27 28

The recently developed Palestinian non-communicable diseases (NCDs) strategy adopted an integrated approach encompassing promotion, prevention and control programmes. Population-based multisectoral effective evidence-based interventions were clearly indicated to control diabetes and promote physical activity such as health promotion, fiscal measures, market control and community participation. Yet a clear vision and scope of implementation are still evolving.29

Modern medical treatments accounted for approximately 30% of the CHD mortality reduction. The scale of effect is similar to that reported in studies using the same methodology in Iceland, Sweden and Finland9 but lower than the 45–50% reported for North America30 and Europe.8 10 The biggest contributions came from aspirin and community-based medications for secondary prevention, chronic angina and heart failure. Treatment uptakes were generally mediocre and need to be improved. However, such treatments create challenges for health providers in terms of identifying patients, providing medications and ensuring their long-term compliance.

Data on patient groups and treatment uptake levels were scarce. Such data were not available at the national or the hospital level. The required information was therefore collected directly from the hospital patients’ records to be utilised in this study. Furthermore, the uptake levels were not consistent among different hospitals and sometimes between physicians. These two findings therefore highlight a lack of standardised healthcare provision and important gaps in the NCD health information system.

Modelling strengths and limitations

The modelling approach used in the study was comprehensive, it synthesised all the key risk factors and treatment options to help quantify changes in CHD mortality. Additionally, the model used rigorous sensitivity analyses to systematically examine the potential influence of uncertainties in the data (quality and sources) and model assumptions, and hence quantify the potential maximum and minimum effects of these contributory factors

This modelling approach also has obvious limitations. Notably, the extent and quantity of available data on CHD risk factor trends and treatment uptake. Furthermore, the model tended to overestimate the number of deaths averted in almost all age groups, especially among women. This may reflect less precision in female data. However, the data used in this model was generally of good quality. Mortality data were obtained from MOH death registry. Death registry data were evaluated in previous studies as medium quality based on the WHO criteria.31 The demographic information was obtained from census data, and the risk factor trends were obtained from well-designed epidemiological studies and national PCBS, MOH and WHO surveys. Treatment uptake and patient group data were obtained from an extensive hospital-based survey conducted in 2009. Very scarce data available on treatment uptake were also obtained. However, researchers had to conduct additional surveys to get the timely, accurate data required by the model. Certain assumptions were needed to fill in the gaps for missing information. For instance, assumptions were made for the small group aged 65–74 years where risk factor information were not available. Assumption on treatment uptake at the starting point was also based on expert opinions working in the system for more than 10 years. Estimates of treatment uptake were collated from international and regional literature then validated with the expert opinions. The generalisation of efficiency estimates from meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials to effectiveness in clinical practice in the West Bank setting were clearly optimistic, and may have resulted in an overestimate of the true treatment benefits.

All these assumptions are transparent, being systematically detailed in the appendix, supported by local expert opinions and literature from the region and included in the sensitivity analyses. By good luck, the overall model fit approached 100%. However, it should be noted that fit within specific age groups was much less perfect.

Public health implications

CHD mortality fell by 20% between 1998 and 2009 in the West Bank, oPt. More than two-third of this fall was due to changes in major risk factors mainly total cholesterol, blood pressure and smoking.

Our results clearly indicate that risk factor improvements in the general population saved substantially more lives than specific treatments for individual patients. This emphasizes the importance of population-wide primary prevention strategies. Such strategies should also emphasize the risk factors which had a negative effect on the reduction of CHD in the model especially, diabetes, BMI and increased levels of physical inactivity. The Palestinian policy and strategic plan for NCD had focused on health diet and physical activity as its second and third policy objectives (MOH).32

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Palestinian Ministry of Health, specifically the Palestinian Health Information Centre and Primary Health Care Staff for providing the researchers with the Stepwise Survey 2010 data.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have fulfilled the following contributions (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and (3) final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: FP7-HEALTH-2007-B. Project number 223075.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Giacaman R, Khatib R, Shabaneh L, et al. An overview of health conditions and health services in the occupied Palestinian territory. Lancet 2009;373:837–49 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Husseini A, Abu-Rmeileh N, Mikki N, et al. Cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, and cancer in the occupied Palestinian territory. Lancet 2009;373:1041–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health P Health status in Palestine 2010. Palestine: Ministry of Health, April 2011

- 4.Husseini A. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and selected associated factors in an adult Palestinian population: an epidemiologic study of type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) in Kobar and Ramallah, Palestine. PhD thesis Oslo: University of Oslo, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdul-Rahim HF. The metabolic syndrome in a rural and an urban Palestinian population: an epidemiological study of selected components of the metabolic syndrome, including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity in the adult population of a rural and an urban Palestinian community. PhD thesis Oslo: University of Oslo, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas P. Cardiovascular disease in developing countries: myths, realities, and opportunities. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1999;13:95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unal B, Critchley JA, Capewell S. Modelling the decline in coronary heart disease deaths in England and Wales, 1981–2000: comparing contributions from primary prevention and secondary prevention. BMJ 2005;331:614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmieri L, Bennett K, Giampaoli S, et al. Explaining the decrease in coronary heart disease mortality in Italy between 1980 and 2000. Am J Public Health 2010;100:684–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laatikainen T, Critchley J, Vartiainen E, et al. Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in Finland between 1982 and 1997. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:764–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett K, Kabir Z, Unal B, et al Explaining the recent decrease in coronary heart disease mortality rates in Ireland, 1985–2000. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006; 60:322–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Critchley J, Liu J, Zhao D, et al. Explaining the increase in coronary heart disease mortality in Beijing between 1984 and 1999. Circulation 2004;110:1236–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Population projections in the Palestinian territory, mid 2006. In: Ramallah, Palestine: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdul-Rahim HF, Abu-Rmeileh NM, Husseini A, et al. Obesity and selected co-morbidities in an urban Palestinian population. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001;25:1736–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mant J, Hicks N. Detecting differences in quality of care: the sensitivity of measures of process and outcome in treating acute myocardial infarction. BMJ 1995;311:793–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2388–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briggs A, Sculpher M, Buxton M. Uncertainty in the economic evaluation of health care technologies: the role of sensitivity analysis. Health Economics 1994;3:95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aspelund T, Gudnason V, Magnusdottir BT, et al. Analysing the large decline in coronary heart disease mortality in the icelandic population aged 25–74 between the years 1981 and 2006. PLoS One 2010;5:e13957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capewell S, Ford E, Croft J, et al. Cardiovascular risk factor trends and potential for reducing coronary heart disease mortality in the United States of America. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:120–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Community and Public Health Smoking and associated factors in the oPt: an analysis of three demographic and health surveys (1995, 2000, and 2004). Ramallah: Birzeit University; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Palestine family health survey, 2006: preliminary report. Ramallah-Palestine: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Health survey—2000: main findings. In: Ramallah-Palestine: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Demographic Health Survey-2004. Final Report. Ramallah, Palestine: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Palestinian family health survey, 2006. Ramallah-Palestine: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdul-Rahim H, Abu-Rmeileh N, Husseini A, et al. Obesity and selected co-morbidities in an urban Palestinian population. Int J Obes 2001;25:1736–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.PCBS Palestinian family health survey, 2006. Ramallah-Palestine: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 26.PCBS. Health Demographic Survey-2004. Final Report. Ramallah: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stettler N, et al. Population-based prevention of obesity: the need for comprehensive promotion of healthful eating, physical activity, and energy balance: a scientific statement from American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Interdisciplinary Committee for prevention (formerly the expert panel on population and prevention science). Circulation 2008;118:428–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sacks G, Veerman JL, Moodie M, et al. ‘Traffic-light/; nutrition labelling and ‘junk-food’ tax: a modelled comparison of cost-effectiveness for obesity prevention. Int J Obes 2011;35:1001–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ministry of Health Priority Areas for Action: In The National Policy and Strategic Plan for Prevention and Management of Non-Communicable Diseases: 2010–2014. Healthof Palestinian National Authority, 2011:7–12 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the U.S. from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:2128–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abu-Rmeileh NME, Husseini A, Abu-Arqoub O, et al. An overview of mortality patterns in the West Bank, occupied Palestinian territory 1999–2003. Prev Chron Dis 2008;5:A112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palestinian Ministry of Health The national policy and strategic plan for prevention and management of non-communicable diseases (2010–2014). Ramallah, Palestine: Palestinian Ministry of Health, 2010 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.