Abstract

The present study examined how postlingually deafened adults with cochlear implants combine visual information from lipreading with auditory cues in an open-set word recognition task. Adults with normal hearing served as a comparison group. Word recognition performance was assessed using lexically controlled word lists presented under auditory-only, visual-only, and combined audiovisual presentation formats. Effects of talker variability were studied by manipulating the number of talkers producing the stimulus tokens. Lexical competition was investigated using sets of lexically easy and lexically hard test words. To assess the degree of audiovisual integration, a measure of visual enhancement, Ra, was used to assess the gain in performance provided in the audiovisual presentation format relative to the maximum possible performance obtainable in the auditory-only format. Results showed that word recognition performance was highest for audiovisual presentation followed by auditory-only and then visual-only stimulus presentation. Performance was better for single-talker lists than for multiple-talker lists, particularly under the audiovisual presentation format. Word recognition performance was better for the lexically easy than for the lexically hard words regardless of presentation format. Visual enhancement scores were higher for single-talker conditions compared to multiple-talker conditions and tended to be somewhat better for lexically easy words than for lexically hard words. The pattern of results suggests that information from the auditory and visual modalities is used to access common, multimodal lexical representations in memory. The findings are discussed in terms of the complementary nature of auditory and visual sources of information that specify the same underlying gestures and articulatory events in speech.

Keywords: cochlear implants, hearing impairment, speech perception, audiovisual

Cochlear implants (CIs) are electronic auditory prostheses for individuals with severe-to-profound hearing impairment that enable many of them to perceive and understand spoken language. However, the benefit to an individual user varies greatly. Auditory-alone performance measures have demonstrated that some CI users are able to communicate successfully over a telephone even when lipreading cues are unavailable (e.g., Dorman, Dankowski, McCandless, Parkin, & Smith, 1991). Other CI users display little benefit in open-set speech perception tests under auditory-alone listening conditions, but find that the CI helps them understand speech when visual information also is available. One source of these individual differences is undoubtedly the way in which the surviving neural elements in the cochlea are stimulated with electrical currents provided by the speech processor (Fryauf-Bertschy, Tyler, Kelsay, Gantz, & Woodworth, 1997). Other sources of variability may result from the way in which these initial sensory inputs are coded and processed by higher centers in the auditory system. For example, listeners with detailed knowledge of the underlying phonotactic rules of English may be able to use limited or degraded sources of sensory information in conjunction with this knowledge to achieve better overall performance.

Fortunately, everyday speech communication is not limited to input from only one sensory modality. Optical information about speech obtained from lipreading improves speech understanding in listeners with normal hearing (NH; Sumby & Pollack, 1954) as well as in persons with CIs (Tyler, Parkinson, Woodworth, Lowder, & Gantz, 1997). Although lipreading cues enhance speech perception, the sensory, perceptual, and cognitive processes underlying this gain in performance are not well understood. In one of the first studies to investigate audiovisual integration, Sumby and Pollack demonstrated that lipreading cues greatly enhance the speech perception performance of NH listeners, especially when the acoustic signal is masked by noise. They found that performance on closed-set word recognition tasks increased substantially under audiovisual presentation compared to auditory-alone presentation. This increase in performance was comparable to the gain observed when the auditory signal was increased by 15 dB under auditory-alone conditions (Summerfield, 1987). Since then, other studies have demonstrated that visual information from lipreading improves speech perception performance over auditory-alone conditions for NH adults (Massaro & Cohen, 1995) and for adults with varying degrees of hearing impairment (Grant, Walden, & Seitz, 1998; Massaro & Cohen, 1999).

Individual Variability and Integration of Auditory and Visual Cues for Speech Perception

The cognitive processes by which individuals combine and integrate auditory and visual speech information with lexical and syntactic knowledge have become an important area of research in the field of speech perception. Audiovisual speech perception appears to be more than the simple addition of auditory and visual information (Bernstein, Demorest, & Tucker, 2000; Massaro & Cohen, 1999). A well-known example of the robustness of audiovisual speech perception is the “McGurk effect” (McGurk & MacDonald, 1976). When presented with an auditory/ba/stimulus and a visual/ga/stimulus, many listeners report hearing an entirely new stimulus: a perceptual/da/. Thus, information from separate sensory modalities can be combined to produce percepts that differ predictably from either the auditory or the visual percept alone. However, these findings are not universal across all individuals (see Massaro & Cohen, 2000). Grant and Seitz (1998) suggested that listeners who are more susceptible to the McGurk effect also are better at integrating auditory and visual speech cues. He and his colleagues proposed that some listeners could improve consonant perception skills by as much as 26% by sharpening their integration abilities (Grant et al., 1998). Their findings on individual variability in the integration of auditory and visual speech cues may have important clinical implications for deaf and hard-of-hearing listeners because consonant perception accounted for approximately half of the variance of word and sentence recognition in their study.

Talker Variability and Spoken Word Recognition

Another source of variability in CI outcomes may lie in each patient’s ability to perceive speech from a variety of different talkers and to deal with the resulting variations in the acoustic–phonetic properties of speech. NH listeners reliably extract invariant phonological and semantic information from speech, even when the utterances are produced by different talkers using different speaking rates or dialects, different styles, or under adverse listening environments (Pisoni, 1993, 1996). The processes by which listeners recognize words and extract meaning from widely divergent acoustic signals are often referred to as perceptual constancy or perceptual normalization.

One of the first studies to examine the effects of talker variability on spoken word recognition was performed by Creelman (1957). He presented lists of words consisting of tokens produced by one to eight talkers to NH listeners in noise. He found poorer speech intelligibility for lists containing tokens produced by two or more talkers than lists produced by only one talker. Subsequent studies have demonstrated similar findings for NH listeners using auditory-alone presentation (Bradlow, Akahne-Yamada, Pisoni, & Tohkura, 1999; Bradlow & Pisoni, 1999; Mullennix, Pisoni, & Martin, 1989; Nygaard & Pisoni, 1995, 1998; Sommers, Nygaard, & Pisoni, 1994) and for listeners with hearing loss (Kirk, Pisoni, & Miyamoto, 1997; Sommers, Kirk, & Pisoni, 1997).

One explanation for the effects of talker variability on spoken word recognition is that perceptual normalization increases processing demands and may divert limited cognitive resources that are normally used for speech perception (Mullennix et al., 1989; Sommers et al., 1994). This hypothesis can account for the decrease in speech perception performance for word lists produced by multiple talkers. An alternative explanation of these findings is that listeners learn to focus on the acoustic cues present in a particular individual’s voice and then use these talker-specific cues to help them in perceiving single-talker word lists (Nygaard & Pisoni, 1998). The first proposal suggests that multiple-talker lists produce a decrement in speech perception performance because cognitive resources are diverted from the normal processes of speech perception to operations needed for perceptual normalization (Mullennix & Pisoni, 1990). The second account suggests that the perceptual advantage for single-talker lists over multiple-talker lists is due to processes related to perceptual learning, attunement, and talker-specific adaptation or adjustment to an individual talker’s voice (Nygaard & Pisoni, 1998).

At present, little is known about the effects of talker variability on speech perception by NH listeners under audiovisual presentation conditions (Demorest & Bernstein, 1992; Lachs, 1996, 1999). Even less is known about talker effects on spoken word recognition by CI recipients under either an auditory-alone or an audiovisual presentation mode. It is not clear whether previous findings with NH listeners can be generalized to adult CI users because some talker-specific attributes, such as a talker’s fundamental frequency, may not be well represented in the electrical stimulation pattern provided by the current-generation of multichannel CIs. If the percepts elicited by changes in fundamental frequency play a role in mediating talker effects, then one might expect the effects of talker variability to be different for NH listeners than for listeners with CIs. CI users may differ in their ability to discriminate the subtle differences between similar talkers, and this in turn may contribute to the differences in spoken word recognition evident across this population.

Lexical Effects on Spoken Word Recognition and Audiovisual Speech Integration

There has been a great deal of research on audiovisual integration and multimodal speech perception in both NH and hearing impaired listeners in the last few years. However, the contributions of the lexicon and knowledge of the sound patterns of words in the language have not been studied. Such investigations may provide important new insights into the large individual differences in CI outcomes.

Audiovisual speech perception is a complex process in which information from separate auditory and visual sensory modalities is combined with prior linguistic knowledge stored in long-term memory. Several researchers have argued that the process of speech perception is fundamentally the same regardless of the conditions under which it is performed, implying that the nervous system processes optical and auditory cues in a similar manner using the same perceptual and linguistic mechanisms (Stein & Meredith, 1993). Recently, Grant et al. (1998) proposed a conceptual framework that can be used to assess this proposal. Their approach combines top-down, cognitive processes and bottom-up, sensory processes to account for performance on audiovisual speech perception tasks. Grant et al. argued that audiovisual integration takes place prior to the influence of higher level lexical factors. Although their approach acknowledges that lexical factors may influence the perception of auditory and visual speech cues, they claim that the largest increases in audiovisual speech perception occur when the information present in the auditory and visual signals is complementary and specifies the same underlying phonetic events expressed in the talker’s articulation.

The Neighborhood Activation Model of Spoken Word Recognition

One way to investigate the perception of auditory and visual speech cues and assess the effects of the lexicon on word recognition is to measure speech perception and audiovisual integration abilities using words that have different lexical properties. The neighborhood activation model (NAM) provides a theoretical framework for understanding how spoken words are recognized and identified from sensory inputs (Luce & Pisoni, 1998). More specifically, NAM provides a theoretical basis for explaining why some words are easy to identify and other words are hard to identify. The NAM assumes that a stimulus input activates a set of similar acoustic–phonetic patterns in memory, a lexical neighborhood. The activation level of each word pattern is proportional to the degree of similarity between the acoustic–phonetic input of the target word and the acoustic–phonetic patterns stored in memory in a multidimensional acoustic–phonetic space. Lexical properties also strengthen or attenuate these levels of activation for particular sound patterns. In the NAM, a word’s level of activation is proportional to its word frequency (i.e., how often that word occurs in the language). The probability of matching a given sensory input to a particular stored lexical pattern is based on the activation level of the individual pattern and the sum of the activation levels of all of the sound patterns selected (Luce & Pisoni, 1998).

The NAM uses information about a word’s lexical neighborhood, its acoustic–phonetic similarity space, to predict whether it will be relatively easy or relatively hard to perceive. In one version of the NAM model, words are considered to be lexical neighbors (i.e., part of the same activation set) if they differ from a target word by the addition, deletion, or substitution of a single phoneme. For example, scat, at, and cap are neighbors of the target word cat. For a given target word, the number of lexical neighbors is called the neighborhood density of the word. Words from “dense” lexical neighborhoods have many similar sounding words, or neighbors, with which they can be confused. Words from “sparse” neighborhoods have fewer similar sounding words, or lexical neighbors. Neighborhood frequency is the average frequency of occurrence in the language of all the words in the neighborhood of a target word. Using these lexical characteristics and word frequency, it is possible to construct two sets of words that differ in lexical discriminability. Lexically easy words occur often in the language and come from low-density lexical neighborhoods with low average neighborhood frequency, whereas lexically hard words occur rarely and come from high-density lexical neighborhoods with high average neighborhood frequency. Luce and Pisoni (1998) showed that lexically easy words are identified faster and more accurately than lexically hard words under auditory-only presentation.

Purpose of the Present Investigation

It is well known that audiovisual speech perception often provides large benefits to individuals with hearing impairment (Erber, 1972, 1975), including CI recipients (Tyler, Fryauf-Bertschy, et al., 1997). In everyday activities, listeners with CIs perceive speech in a wide variety of contexts, including television, face-to-face conversation, and over the telephone. Success in recognizing words and understanding the talker’s intended message may differ quite substantially under these diverse listening conditions. The primary goal of this study was to examine the ability of CI users to integrate the limited auditory information they receive from their device with visual speech cues during spoken word recognition. Secondary goals were to evaluate the effects of lexical difficulty and talker variability on audiovisual speech integration by listeners with CIs.

Method

Participants

Forty-one adults served as listeners in this study and were paid for their participation. Twenty were postlingually deafened adult CI users who were recruited from the clinical population at Indiana University (see Table 1). All of the CI users had profound bilateral sensorineural hearing losses and had used their device for at least 6 months. Their mean age at time of testing was 50 years. The comparison group consisted of 21 adult NH listeners who were recruited from within Indiana University and the associated campuses through newspaper and e-mail advertisements and announcements. The average age of these participants was 42 years. All of the listeners in the control group had pure-tone thresholds below 25 dB HL at 250, 500, 1000, 2000, 3000, and 4000 Hz and below 30 dB HL at 6000 Hz. Each participant was reimbursed for travel to and from testing sessions and was paid $10 per hour of testing.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients with cochlear implants

| Participant | Age (years) at test | Onset of deafness (years) | CI use (months) | Implant type | Processor | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI1 | 69 | 65 | 30 | N22 | Spectra | SPEAK |

| CI2 | 43 | 27 | 24 | MedEl | Combi40 | n-of-m |

| CI3 | 51 | 50 | 8 | N24 | Sprint | SPEAK |

| CI4 | 71 | 36 | 6 | MedEl | Combi40+ | CIS |

| CI5 | 35 | 30 | 48 | N22 | Spectra | SPEAK |

| CI6 | 42 | 39 | 6 | N24 | Sprint | SPEAK |

| CI7 | 59 | 38 | 108 | N22 | Spectra | SPEAK |

| CI8 | 62 | 56 | 60 | N22 | MSP | MPEAK |

| CI9 | 36 | 34 | 6 | N24 | Sprint | SPEAK |

| CI10 | 59 | 50 | 107 | N22 | Spectra | SPEAK |

| CI11 | 45 | 40 | 60 | N22 | Spectra | MPEAK |

| CI12 | 19 | 5 | 96 | N22 | Spectra | SPEAK |

| CI13 | 49 | 41 | 6 | N24 | Sprint | ACE |

| CI14 | 34 | 30 | 36 | Clarion | Clarion | CIS |

| CI15 | 66 | 57 | 63 | Clarion | Clarion | CIS |

| CI16 | 74 | 65 | 34 | N22 | Spectra | SPEAK |

| CI17 | 68 | 58 | 12 | Clarion | Clarion | CIS |

| CI18 | 40 | 9 | 18 | Clarion | Clarion | CIS |

| CI19 | 37 | 3 | 57 | Clarion | Clarion | CIS |

| CI20 | 44 | 43 | 12 | Clarion | Clarion | CIS |

Note. n-of-m = stimulation of n electrodes per cycle out of a total of m electrodes; CIS = continuous interleaved sampling.

Stimulus Materials

The stimulus materials used in the present investigation were drawn from a large database of digitally recorded audiovisual speech tokens (Sheffert, Lachs, & Hernández, 1996). This database contains 300 monosyllabic English words produced by five male and five female talkers. For the present study, we created six equivalent word lists that would allow us to examine the effect of presentation format, talker variability, and lexical difficulty on spoken word recognition. Each test list contained 36 words. On each list, half of the words were lexically easy and half were lexically hard. Lexical density was calculated for each word by counting the number of lexical neighbors using the Hoosier Mental Lexicon database (Nusbaum, Pisoni, & Davis, 1984). The word frequency values represented the number of times each target word occurred per 1 million words of text (Kucera & Francis, 1967). Two versions of each of the six original word lists were produced. One version contained tokens produced by a single talker and the second contained tokens produced by six different talkers. This arrangement enabled us to administer a single-talker or multiple-talker version of each test list.

Balanced Word List Generation

The specific audiovisual stimulus tokens used in the 12 word lists were selected from the digital database using intelligibility data obtained from undergraduate psychology students at Indiana University in two earlier investigations (Lachs & Hernández, 1998; Sheffert et al., 1996). In these intelligibility studies, different groups of students listened to the words produced by each of the talkers in the database and typed the word they perceived into a computer. Separate groups of listeners were used for each talker under each presentation condition (visual-only, auditory-only, and audiovisual). The average intelligibility of each word produced by each talker was computed separately under each of the three presentation formats. In creating the final word lists, 216 words were selected from seven of the talkers using a customized computer program. This program generated equivalent word lists within a given presentation format regardless of lexical discriminability. That is, the average intelligibility of the lexically easy words and the lexically hard words was equivalent across the six lists used under the three presentation formats. This equivalence was verified by paired t tests, which revealed no significant differences in the speech intelligibility scores between any of the lists under a given presentation format.

Because one goal of this study was to examine the effects of talker variability on word recognition, the lists also were balanced for talker effects. To accomplish this, the talker whose average speech intelligibility rating in the visual-only condition was the closest to the average across all talkers in that condition was chosen as the talker for the single-talker lists. Speech intelligibility scores from the visual-only condition were used to select the single talker because intelligibility scores obtained from the undergraduate psychology students in the other two presentation conditions were near ceiling. Once the speaker for the single-talker lists was chosen, the individual intelligibility scores for the tokens produced by the single talker and the remaining six talkers in all three presentation conditions were used to equate intelligibility of the single-talker and multiple-talker lists, respectively. Following this procedure, all six word lists were equally intelligible under a given presentation format regardless of talker condition.

Procedure

Testing was conducted in a single-walled sound treated IAC booth (Industrial Acoustics Company, Bronx, NY, Model 102249). The digitized audiovisual stimuli were presented to participants using a PowerWave 604 (Macintosh-compatible) computer equipped with a Targa 2000 video board. All listeners were tested individually, one at a time. The experimental procedures were self-paced. Video signals were presented with a JVC 13U color monitor. Speech tokens were presented via a loudspeaker at 70 dB SPL (C-weighted) for participants using CIs. Each participant was administered three single-talker and three multiple-talker lists. Within each talker condition, one list was presented in the auditory-only condition, one in the visual-only condition, and one in the audiovisual condition. Visual-only presentation was achieved by attenuating the loudspeaker, and auditory-only presentation was achieved by turning off the video display monitor.

NH participants were tested using a −5 dB signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in speech spectrum noise at 70 dB SPL relative to the 65 dB SPL speech tokens. This SNR was chosen during preliminary testing to prevent most of the participants with NH from attaining ceiling performance on the task. All of the participants were asked to repeat verbally the word that was presented aloud. The experimenter subsequently recorded the participants’ verbal responses into computer files online. No feedback was provided.

Results

A summary of the raw scores obtained by the two participant groups as a function of presentation format, lexical difficulty, and talker variability is presented in Table 2. With the exception of the visual-only condition, direct comparisons of the raw scores between the CI and NH control groups are not valid. Recall that in formats where auditory speech information was presented, the CI group was tested in quiet whereas the NH group was tested in white noise to reduce performance below ceiling levels. It is the pattern of performance within each listener group that can be compared, not absolute scores between groups.

Table 2.

Mean percentage correct word recognition performance by condition.

| Talker cond. and lexical discrim. | Presentation format

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI (N = 20)

|

NH (N = 21)

|

|||||

| V | A | AV | V | A | AV | |

| Single-talker | ||||||

| Easy | 23.9 (2.4) | 34.4 (5.0) | 75.8 (3.3) | 18.0 (2.4) | 54.2 (3.6) | 75.4 (2.5) |

| Hard | 8.9 (1.4) | 29.4 (4.9) | 64.2 (3.7) | 4.8 (0.9) | 45.2 (2.7) | 70.9 (2.8) |

| Multiple-talker | ||||||

| Easy | 21.7 (2.6) | 38.6 (4.7) | 70.0 (3.3) | 15.6 (2.5) | 48.9 (3.7) | 74.3 (3.0) |

| Hard | 9.4 (1.5) | 23.9 (3.6) | 52.7 (4.0) | 8.2 (1.3) | 39.7 (3.9) | 62.2 (4.0) |

Note. V = visual-only; A = auditory-only; AV = audiovisual. Standard error of the mean is shown in parentheses.

Accordingly, the data from the CI group and the NH group were submitted to two separate three-way repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs), with the factors of presentation mode (visual-only, auditory-only, and audiovisual), talker variability (single vs. multiple), and lexical difficulty (easy vs. hard) treated as within-subjects variables. The results of the two ANOVAs revealed several commonalities between the two comparison groups with respect to the manipulated factors. For readability, these results have been tabulated in Table 3 and are discussed below in more detail.

Table 3.

Results of ANOVAs for raw scores.

| Listener group | Effect | Statistic | S |

|---|---|---|---|

| CI | Presentation Format | F(2, 38) = 121.37 | ≤ .0009 |

| Talker | F(1, 19) = 7.88 | .011 | |

| Lexical | F(1, 19) = 90.94 | ≤ .0009 | |

| Presentation Format × Talker | F(2, 38) = 3.07 | .058 | |

| Presentation Format × Lexical | F(2, 38) = 1.03 | .366 | |

| Talker × Lexical | F(1, 19) = 3.49 | .077 | |

| Presentation Format × Talker × Lexical | F(2, 38) = 2.75 | .077 | |

| NH | Presentation Format | F(2, 38) = 277.96 | ≤ .0009 |

| Talker | F(1, 19) = 5.98 | .024 | |

| Lexical | F(1, 19) = 66.78 | ≤ .0009 | |

| Presentation Format × Talker | F(2, 38) = 3.48 | .04 | |

| Presentation Format × Lexical | F(2, 38) < 1 | .847 | |

| Talker × Lexical | F(1, 19) < 1 | .628 | |

| Presentation Format × Talker × Lexical | F(2, 38) = 2.48 | .097 |

Effects of Presentation Format

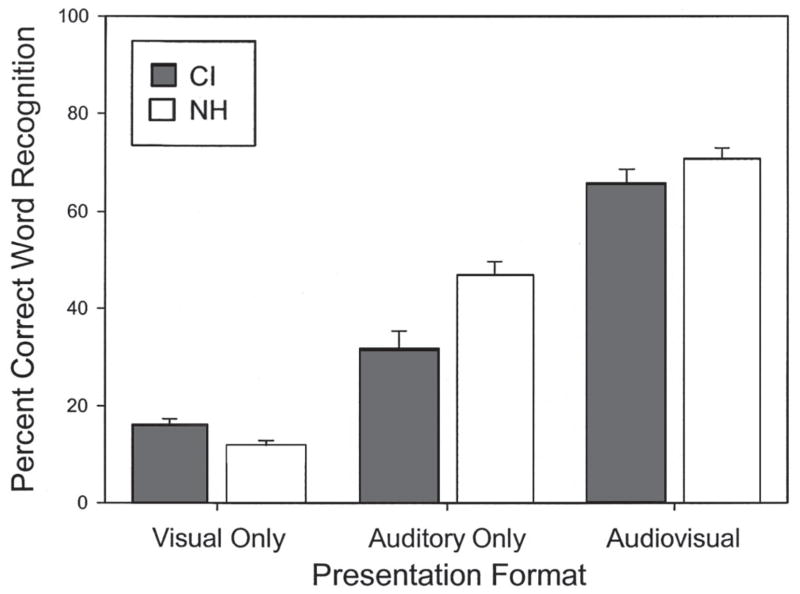

The performance of each participant group under the three presentation formats, averaged across talker condition and lexical competition, is displayed in Figure 1. A significant main effect of presentation mode was observed for both groups (see Table 3). Regardless of group membership, performance in the visual-only condition (MCI = 15.97%, SECI = 1.37%; MNH = 11.64%, SENH = 1.27%) was worse than in the auditory-only condition (MCI = 31.60%, SECI = 3.91%; MNH = 46.76%, SENH = 2.93%), which in turn was even worse than in the audiovisual condition (MCI = 65.69%, SECI = 3.06%; MNH = 70.70%, SENH = 2.28%). As shown in Figure 1, CI users obtained higher scores in the visual-only condition than their NH counterparts.

Figure 1.

Percentage correct word recognition performance of the CI and the NH listeners under the three presentation formats averaged over talker and lexical variables. CI listeners were tested in quiet and NH listeners were tested in noise at −5 dB SPL. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

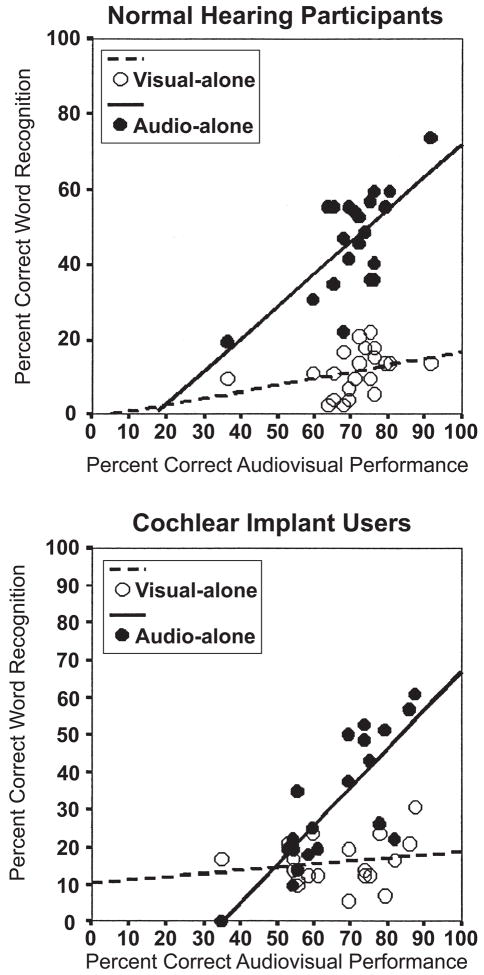

To examine the relations among the presentation conditions, speech intelligibility scores obtained under each presentation condition were evaluated separately for each group of listeners. Each participant’s performance in the visual-only and auditory-only presentation conditions is plotted as a function of performance in the audiovisual condition in Figure 2. The data for the NH group are shown in the top panel and the data for the CI group are shown in the bottom panel. The data are collapsed over talker and lexical variables. Significant correlations were obtained between performance in the auditory-only and audiovisual conditions for both groups of listeners, r(21) = .67, p < .001 for NH listeners and r(20) = .81, p < .001 for CI listeners. However, the correlations between performance in the visual-only and audiovisual conditions were not significant for either group. Additional correlations were computed between performance in the visual-only and auditory-only conditions for each group of listeners. None of these correlations was significant. Inspection of Figure 2 reveals for the unimodal presentation conditions that the individual scores for CI listeners varied over a somewhat greater range than the individual performance for NH listeners tested in noise. Moreover, the scatter of the data generally was greater for the CI group than for the NH group, but the overall range of variation was similar for the two groups (36.1%–91.7% and 34.7%–87.5% for the NH and CI listeners, respectively). Scores in the auditory-only condition varied between 19.3% and 73.6% for the NH group and between 0% and 61.1% for the CI group. Ranges of scores in visual-only condition were more restricted, with performance between 2.8% and 22.2% for the NH group and between 5.6% and 30.6% for the CI group. Given that many phonemes look alike when they are produced, the average lipreading score for the CI users falls within the expected range.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of each individual’s word recognition performance for the auditory-only and visual-only conditions as a function of his or her word recognition performance in the audiovisual presentation format. Performance is shown separately for NH listeners (top panel) and the CI listeners (bottom panel). Data were averaged across talker and lexical variables. Least-squares fitted lines are shown separately for auditory-only and visual-only correlations with the audiovisual presentation format.

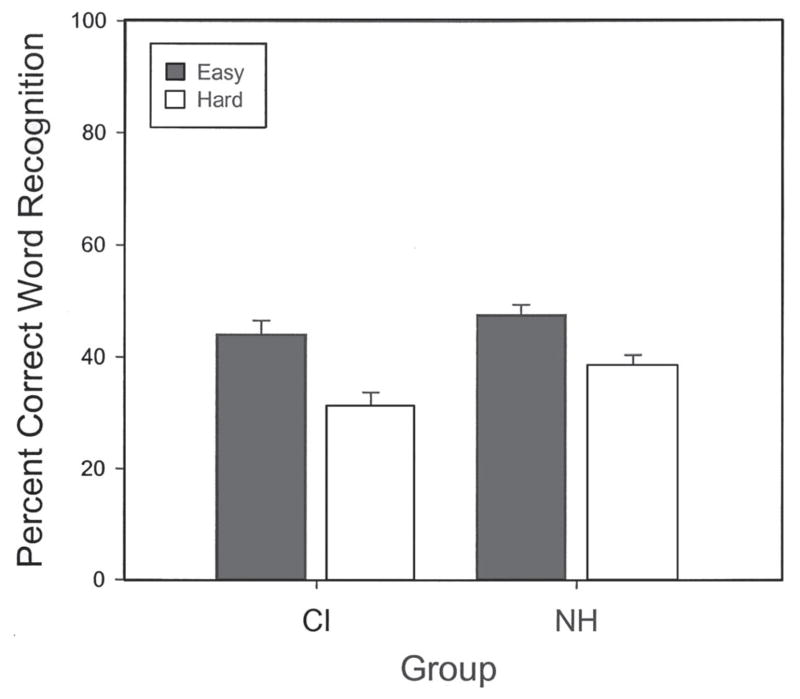

Effects of Lexical Competition

The three-way ANOVAs also revealed a significant main effect of lexical difficulty for both groups (see Table 3). As shown in Figure 3, easy words (MCI = 44.07%, SECI = 2.42%; MNH = 47.58%, SENH = 1.78%) were recognized with greater accuracy than hard words (MCI = 31.44%, SECI = 2.37%; MNH = 41.50%, SENH = 1.87%) for both groups of participants.

Figure 3.

The percentage of words correctly identified by CI and NH listeners as a function of lexical difficulty of the stimulus words.

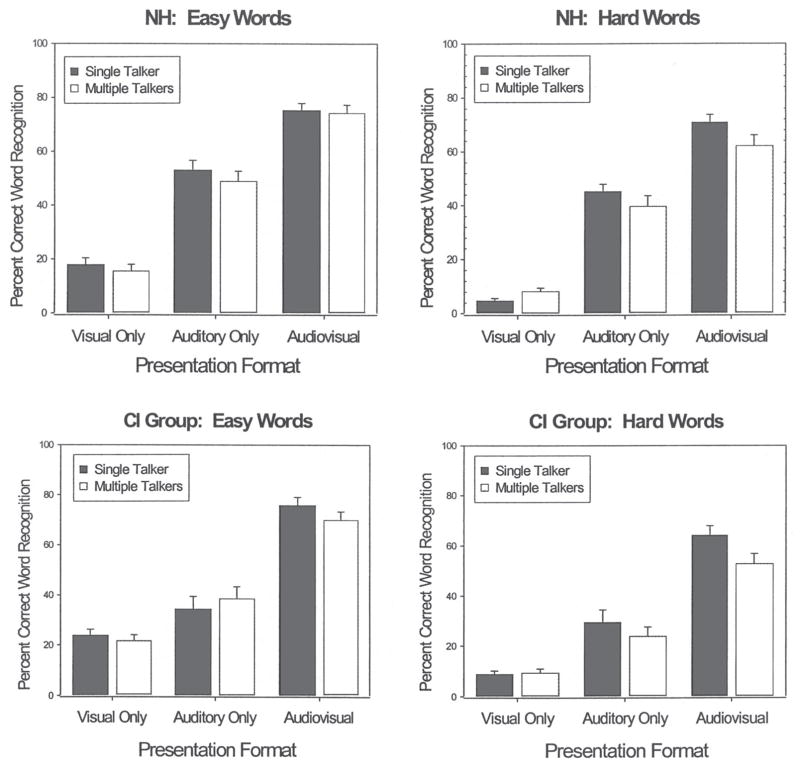

Effects of Talker Variability

The main effect of talker variability also was significant for the CI and NH groups. Overall, single-talker lists (MCI = 39.44%, SECI = 2.08%; MNH = 44.58%, SENH = 2.03%) were identified better than multiple-talker lists (MCI = 36.07%, SECI = 2.21%; MNH = 41.49%, SENH = 2.16%). Talker variability also interacted with presentation mode for both groups, although the effect was only marginally significant for the CI group. A similar marginally significant three-way interaction between presentation mode, talker variability, and lexical difficulty also was obtained for both groups of participants (see Table 3).1 This interaction is shown for each participant group in Figure 4. Tests of simple effects revealed a complex pattern of results (see Table 4). For easy words (the left panels of Figure 4), the difference in performance between single- and multiple-talker lists did not differ for the NH group in any presentation condition; the interaction between presentation mode and talker variability for the CI group also is not quite significant. Post hoc analyses revealed that, for the CI group, performance on single-talker lists was better than performance on multiple-talker lists in the audiovisual condition only. In summary, talker variability played a limited role in word recognition performance for lexically easy words, regardless of hearing group.

Figure 4.

The percentage of words correctly identified in each presentation format by the NH listeners (top panel) and CI users (bottom panel) for lexically easy (left panels) and hard (right panels) words. The parameter in each panel is the condition of talker variability.

Table 4.

Simple effects for both groups for the three-way interaction between presentation format, talker variability, and lexical competition.

| Listener group and lexical competition | Effect | Statistic | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| CI | |||

| Easy | Presentation Format × Talker | F(2, 38) = 2.53 | .093 |

| Hard | Presentation Format × Talker | F(2, 38) = 3.36 | .045 |

| NH | |||

| Easy | Presentation Format × Talker | F(2, 40) < 1 | .737 |

| Hard | Presentation Format × Talker | F(2, 40) = 6.08 | .005 |

In contrast, we found that for lexically hard words (the right panels of Figure 4), presentation mode interacted with talker variability for both groups of listeners. For hard words, performance on single-talker lists was better than performance on multiple-talker lists in the audiovisual condition for both groups of listeners.

Visual Enhancement

In their pioneering study of audiovisual speech perception, Sumby and Pollack (1954) developed a quantitative metric to evaluate the gains in speech intelligibility performance due to the addition of visual information from seeing a talker’s face. Because speech perception scores have a theoretical maximum (i.e., perfect performance), the measure was developed to show the extent to which additional visual information about speech improved performance relative to the amount by which auditory performance could possibly improve. Their metric, Ra, can be used to assess the extent of visual enhancement for an individual perceiver in our study. To assess visual enhancement, Ra was calculated for all 41 participants based on the recognition scores obtained in the auditory-alone and audiovisual conditions using Equation 1 from Sumby and Pollack (1954):

| (1) |

In the equation, AV is performance in the audiovisual condition, and A is performance in the auditory-alone condition. Ra was calculated separately for lexically easy and lexically hard words in each of the two talker conditions. The Ra’s resulting from this analysis are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mean visual enhancement (Ra) as a function of listener group, lexical difficulty, and talker condition.

| Lexical difficulty | Listener group

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI

|

NH

|

|||

| Single-talker cond. | Multiple-talker cond. | Single-talker cond. | Multiple-talker cond. | |

| Ra for lexically easy words | .64 (.07) | .50 (.05) | .40 (.07) | .49 (.05) |

| Ra for lexically hard words | .64 (.07) | .50 (.05) | .40 (.07) | .49 (.05) |

| Total Ra | .56 (.04) | .43 (.04) | .45 (.04) | .43 (.04) |

Note. Standard error of the mean is shown in parentheses.

An ANOVA was used to evaluate the visual enhancement scores in each condition. Because Ra normalizes for auditory-alone performance, it is possible to compare across listener groups. Thus, listener group was a between-subject factor in the ANOVA. talker variability and lexical difficulty were within-subject factors. Overall, Ra was larger for single-talker (M = 0.50, SE = 0.03) conditions than for multiple-talker conditions (M = 0.43, SE = 0.03), F(1, 39) = 4.78, p = .04. The interaction between talker and group also was significant, F(1, 39) = 4.05, p = .05. Simple effects analysis revealed that the interaction was due to a difference in visual enhancement for single-versus multiple-talker lists for CI users, F(1, 39) = 8.58, p = .006, but not for NH participants, F(1, 39) < 1, ns.

There also was a marginal main effect of lexical difficulty, F(1, 39) = 3.82, p = .06. Ra scores for lexically easy words (M = 0.51, SE = 0.04) were higher than the scores for lexically hard words (M = 0.42, SE = 0.03). This result indicates that listeners obtained somewhat greater visual benefit from words that have less lexical competition than from words that have more lexical competition. No other main effects or interactions from the Ra ANOVA were significant.

Discussion

Effects of Presentation Format

We want to emphasize that direct comparisons of the raw scores between the two groups of listeners as a function of presentation format need to be made with some degree of caution. The nature of the degradation resulting from the presentation of speech in noise to NH listeners is not equivalent to the transformation of speech that is processed by a CI. However, the pattern of performance within each listener group can be compared.

Presentation format affected both groups of listeners in similar ways: Performance in the visual-only condition was consistently below performance in the auditory-only condition. In addition, performance was always best when both auditory and visual sources of information were available for speech perception. In addition, NH listeners performed better than CI users in the auditory-only condition but CI users performed better than NH listeners in the visual-only condition. These findings are consistent with a recent report by Bernstein, Auer, and Tucker (2001), who found reliable differences in the performance of NH and hearing-impaired speechreaders on a visual-alone speech perception task. The pattern of results observed in the present study may be due to the way lipreading skills were acquired in these patients. The CI users in our sample all were progressively, postlingually deafened. It is possible that over long periods of time, a gradual reliance on lipreading eventually leads to greater use of the visual correlates of speech when the auditory information in the speech signal is no longer sufficient to support word recognition. Further work on the time course of learning speechreading skills in postlingually deafened adults is needed before any definitive conclusions can be drawn.

The two groups of listeners also achieved roughly the same level of performance in the audiovisual condition even though they differed in the extent to which they were able to perceive speech from either sensory modality alone. This result illustrates the complementary use of auditory and visual information in speech perception (Summerfield, 1987). Namely, when the information available in one sensory modality (e.g., audition) is noisy, degraded, or impoverished, information available in the other modality (e.g., vision) can “make up the difference” by providing complementary cues that combine to enhance overall word recognition performance in a particular task.

For both groups, performance in the auditory-only and audiovisual conditions was significantly correlated. Performance in the visual-only condition was not correlated significantly with performance in the auditory-only or audiovisual conditions for either group. The present results differ somewhat from those of earlier investigations. Previous studies have demonstrated significant correlations among visual-only, auditory-only, and audiovisual performance on consonant perception measures (Grant & Seitz, 1998) and between visual-only and auditory-only performance on word perception measures (Watson, Qiu, Chamberlain, & Li, 1996). It is very likely that the lack of correlations with scores from the visual-only condition is due to floor effects and the absence of variability in that condition.

The event-based theory of speech perception (Fowler, 1986) suggests the two sources of sensory stimulation that provide information about speech are complementary because auditory and visual speech cues are structured by a unitary, underlying articulatory event. That is, when a person speaks, his or her articulatory patterns and gestures simultaneously shape both auditory and optic patterns of energy in very specific, lawful ways. The relations between the two modalities, then, are specified by the information relating each pattern to the common, underlying, dynamic vocal tract gestures of the talker that produced them. It is precisely this time-varying articulatory behavior of the vocal tract that has been shown to be of primary importance in the perception of speech (Liberman, Cooper, Shankweiler, & Studdert-Kennedy, 1967; Remez, Fellowes, Pisoni, Goh, & Rubin, 1998; Remez, Rubin, Pisoni, & Carrell, 1981; Remez, Rubin, Berns, Pardo, & Lang, 1994).

With this conceptualization in mind, the sensory and perceptual information relevant for speech perception is modality-neutral or amodal, because it can be carried by more than one sensory modality (Fowler, 1986; Gaver, 1993; Remez et al., 1998; Rosenblum & Saldaña, 1996). The amodal nature of phonetic information is demonstrated convincingly in studies showing that perceptual information obtained via the tactile modality, in the form of Tadoma, can be used and integrated across sensory modalities in speech perception (Fowler & Dekle, 1991), albeit with limited utility.

The information necessary for speech perception may be modality-neutral, but the internal representation of speech appears to be based on an individual’s experience with perceptual events and actions in the physical world (Lachs, Pisoni, & Kirk, 2001). Thus, awareness of the intermodal relations between auditory and visual information is contingent on experience with more than one sensory modality. Because our CI participants were all postlingually deafened adults, they had acquired knowledge of the lawful correspondences between auditory and visual correlates of speech. As the present findings demonstrate, the CI participants were able to make use of this experience when presented with audiovisual stimuli; they recognized isolated words in the audiovisual condition at levels comparable to those of the NH participants.

Although there were similarities in performance across the two groups, other comparisons revealed small and consistent differences within groups. Both groups of listeners integrated auditory and visual speech information, but the CI listeners made better use of the visual speech cues in more difficult listening conditions (e.g., when they were forced to make fine phonetic discriminations among acoustically confusable words or when there was ambiguity about the talker).

Effects of Lexical Competition

For both groups, lexically easy words were recognized better than lexically hard words, indicating that NH and CI listeners organize and access words from memory in fundamentally similar ways. Thus, phonetically similar words in the mental lexicons of CI users compete for selection during word recognition. This process also is affected by word frequency, such that more frequently occurring words are apt to win out among phonetically similar competitors. The pattern of the CI listeners’ word recognition scores demonstrates that they recognize spoken words “relationally” in the context of other words they know and have in their mental lexicons, just as do NH listeners. Presumably, the adults with CIs developed extensive lexical representations when they had normal hearing and retained some form of this information over time after their hearing loss.

CI users performed more poorly on lexically hard words than NH listeners. However, performance for both groups on lexically easy words was statistically equivalent. This interaction suggests that the CI users were poorer at making the fine acoustic–phonetic distinctions among words that are needed to distinguish lexically hard words from their phonetically similar neighbors. Although auditory information provided by a CI appears adequate for recognizing words when only gross acoustic cues are sufficient, it may not provide the more fine-grained phonetic information necessary to discriminate between very similar lexical candidates for some individuals. Our data suggest that differences in performance between the two groups of listeners occur during early perceptual analysis when the initial sensory information is encoded prior to lexical selection.

Effects of Talker Variability

Talker variability did not significantly influence the recognition of lexically easy words. However, both groups of listeners were significantly better at recognizing lexically hard words in the audiovisual condition when they were spoken by a single talker rather than by multiple talkers. The results on the effects of talker variability are consistent with the proposal that repeated exposure to a single talker allows the listener to encode voice-specific attributes of the speech signal. Once internalized, voice-specific information can improve word recognition performance (Nygaard & Pisoni, 1998; Nygaard, Sommers, & Pisoni, 1995). The single-talker advantage appears to be most helpful when there is a great deal of lexical competition among words, as with lexically hard words. Talker-specific information can serve to disambiguate multiple word candidates from within the lexicon. For both groups of listeners, this detail is provided in the audiovisual condition. The lack of a talker effect in other presentation conditions may have occurred because the optical or auditory displays alone were insufficient to adequately limit the set of potential lexical candidates. In addition, it is very likely that detailed talker-specific information would be difficult to obtain for the visual-alone presentation of short words in isolation. The same can be said for auditory-alone presentation of isolated words perceived through CIs or buried in noise (see Nygaard & Pisoni, 1998; Nygaard, Sommers, & Pisoni, 1994). Nygaard et al. (1994) found that it was much more difficult for participants to learn novel voices from isolated words than from short sentences. Sentences provide additional information about prosody and timing that is not available in isolated words.

Visual Enhancement

Visual enhancement scores indicate the extent to which visual speech information enhances spoken word recognition relative to the amount by which auditory-alone performance could improve. The current results revealed a significant interaction between group and talker variability for visual enhancement scores. That is, visual enhancement was similar for the two groups in the multiple-talker conditions, but the CI users demonstrated greater visual enhancement in the single-talker condition than did the NH listeners. This finding does not mean that NH listeners were unaffected by talker variability. However, talker variability did not affect the degree to which NH listeners could combine auditory and visual speech cues. The present findings suggest that CI users are better able to extract idiosyncratic talker information from audiovisual displays than are the NH listeners. Perhaps the CI listeners appear better because they rely more on visual speech information to perceive speech in everyday situations. With repeated exposure to audiovisual stimuli spoken by the same talker, the CI users exhibited a gain beyond that observed for the NH listeners. CI users may be able to acquire more detailed knowledge of the cross-modal relations between audition and vision for a particular talker. Because NH listeners can successfully process spoken language by relying entirely on auditory cues, they may not have learned to utilize visual cues as successfully (Bernstein et al., 2001). Combined audiovisual information from a single talker may not provide NH listeners any additional information about that talker than the cues provided by the auditory presentation. This is especially true in a short-term laboratory experiment like the present one. The NH listeners have little prior exposure to visual-alone stimuli. It seems likely that if the NH listeners had received more practice in listening to degraded speech in noise, then they also might have developed a greater awareness of the cross-modal relations between auditory and visual speech cues. In turn, their scores likely would have shown effects after practice.

In future studies using NH listeners as control participants, it would be preferable to use methods of signal degradation other than masking noise to reduce scores below the ceiling. For example, a number of researchers have used noise-band speech to simulate the nature of the hearing loss and signal transformation produced by a CI (Dorman, Loizou, Fitzke, & Tu, 1998; Dorman, Loizou, Kemp, & Kirk, 2000; Shannon, Zeng, Kamath, Wygonski, & Ekelid, 1995). Such simulations should make possible direct comparisons of the performance of CI and NH listeners in auditory-only and audiovisual presentation formats.

Clinical Implications

With recent advances in CI technology, many postlingually deafened adults are now able to achieve very high levels of spoken word recognition through listening alone (Kirk, 2000). Other patients may derive substantial benefit from a CI only when the auditory cues they receive are combined with visual information from a talker’s face. Like NH listeners, many CI recipients report benefit from the presence of visual speech cues under difficult listening situations (e.g., when the talker is speaking rapidly or has an unfamiliar dialect, or when listening in the presence of background noise).

Although we did not observe any consistent individual differences in performance across any of the experimental conditions, it is well known that listeners with CIs display a wide range of performance on various outcome measures. The patients selected for this study were all good users who were able to derive large benefits from their CIs. All of them were able to respond appropriately in an open-set word recognition task given the limited auditory input provided by their implant. Examination of the other CI patients who do more poorly under these conditions may reveal a wider range of scores, a different pattern of audiovisual integration skills, and different levels of reliance on visual information about speech.

Structured aural rehabilitation activities with a sensory aid (either a CI or a hearing aid) often rely on highly constrained and organized listening activities intended to enhance the users’ ability to discriminate or recognize various acoustic cues in speech. Words or sentences are usually presented in the auditory modality by a single clinician. There has been little systematic application of the findings from recent studies on variation and variability in speech perception and multimodal perception to therapy and rehabilitation with clinical populations. The findings from the present study suggest that it may be fruitful to apply some of the knowledge gained recently about audiovisual speech perception to clinical problems associated with intervention and aural rehabilitation after a patient receives a sensory aid. Exposure to multiple talkers and a wide range of speaking styles in both auditory-alone and audiovisual modalities may provide patients with a greater range of stimulus variability during the first few months of use after receiving an implant; this in turn may help patients develop more robust perceptual strategies for dealing with speech in real-world listening conditions that exist outside the clinic and research laboratory. Specially designed word lists can be developed and used for training materials under different presentation formats to emphasize difficult phonetic contrasts. Such contrasts may be hard to recognize using only auditory speech cues, but easy to identify when both auditory and visual cues are available. Similarly, activities such as connected discourse tracking with audiovisual stimuli may promote and enhance the development of robust multimodal speech representations and spoken language processing. Auditory training activities using multimodal stimuli may enhance the perception of both auditory and visual speech cues. As noted above, not all CI recipients can recognize speech through listening alone. For many of these patients, the CI serves as a sensory aid to improve lipreading skills they already have acquired and use routinely in processing spoken language.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grants K23 DC00126, R01 DC00111, and T32 DC 00012. Support also was provided by Psi Iota Xi National Sorority. We thank Marcia Hay-McCutcheon and Stacey Yount for their assistance in data collection and management. We also are grateful to Luis Hernandez and Marcelo Areal for their development of the software used for stimulus presentation and data collection. Finally, we thank Sujuan Gao for her assistance with the power analyses reported here.

Footnotes

Power analyses were conducted assuming the effect sizes observed in the data. A pooled standard deviation estimate was used for a common standard deviation at each factor combination level. Intraclass correlations were set to be .48 based on the data. Type I error was set at .05 for all analyses. The power analyses revealed that the power to detect a significant two-way interaction between presentation mode and talker variability for the CI group was estimated at 71%, whereas the power for detecting a significant three-way interaction including lexical competition was only 68% for the CI group and 58% for the NH group. Thus, it is likely that with testing of more CI participants, the two-way interaction would have reached significance, as it did for the NH group.

Contributor Information

Adam R. Kaiser, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis

Karen Iler Kirk, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis.

Lorin Lachs, Indiana University, Bloomington.

David B. Pisoni, Indiana University, Bloomington

References

- Bernstein LE, Demorest ME, Tucker PE. Speech perception without hearing. Perception & Psychophysics. 2000;62:233–252. doi: 10.3758/bf03205546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein LE, Edward T, Auer J, Tucker PE. Enhanced speechreading in deaf adults: Can short-term training/practice close the gap for hearing adults? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001;44:5–18. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradlow AR, Akahne-Yamada R, Pisoni DB, Tohkura Y. Training Japanese listeners to identify English/r/and/l/: Long-term retention of learning perception and production. Perception & Psychophysics. 1999;61:977–985. doi: 10.3758/bf03206911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradlow AR, Pisoni DB. Recognition of spoken words by native and non-native listeners: Talker-, listener-, and item-related factors. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1999;106:2074–2085. doi: 10.1121/1.427952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creelman CD. Case of the unknown talker [Abstract] Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1957;29:655. [Google Scholar]

- Demorest ME, Bernstein LE. Sources of variability on speechreading sentences: A generalizability analysis. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1992;35:876–891. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3504.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MF, Dankowski K, McCandless G, Parkin JL, Smith LB. Vowel and consonant recognition with the aid of a multichannel cochlear implant. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1991;43:585–601. doi: 10.1080/14640749108400988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MF, Loizou PC, Fitzke J, Tu Z. The recognition of sentences in noise by normal-hearing listeners using simulations of cochlear-implant signal processors with 6–20 channels. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1998;104:3583–3596. doi: 10.1121/1.423940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MF, Loizou PC, Kemp LL, Kirk KI. Word recognition by children listening to speech processed into a small number of channels: Data from normal-hearing children and children with cochlear implants. Ear and Hearing. 2000;21:590–596. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber NP. Auditory, visual and auditory-visual recognition of consonants by children with normal and impaired hearing. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1972;15:413–422. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1502.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber NP. Auditory-visual perception of speech. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1975;40:481–492. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4004.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CA. An event approach to the study of speech perception from a direct-realist perspective. Journal of Phonetics. 1986;14:3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CA, Dekle DJ. Listening with eye and hand: Cross-modal contributions to speech perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1991;17:816–828. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.17.3.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryauf-Bertschy H, Tyler RS, Kelsay DMR, Gantz B, Woodworth G. Cochlear implant use by prelingually deafened children: The influences of age at implant and length of device use. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1997;40:183–199. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4001.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaver WW. What in the world do we hear?: An ecological approach to auditory event perception. Ecological Psychology. 1993;5(1):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Grant KW, Seitz PF. Measures of auditory-visual integration in nonsense syllables and sentences. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1998;104:2438–2450. doi: 10.1121/1.423751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KW, Walden BE, Seitz PF. Auditory-visual speech recognition by hearing-impaired subjects: Consonant recognition, sentence recognition, and auditory-visual integration. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1998;103:2677–2690. doi: 10.1121/1.422788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk KI. Challenges in the clinical investigation of cochlear implant outcomes. In: Niparko JK, Kirk KI, Mellon NK, Robbins AM, Tucci DL, Wilson BS, editors. Cochlear implants: Principles and practices. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 225–259. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk KI, Pisoni DB, Miyamoto RC. Effects of stimulus variability on speech perception in listeners with hearing impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1997;40:1395–1405. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4006.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera F, Francis W. Computational analysis of present day American English. Providence, RI: Brown University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Lachs L. Research on spoken language processing. Progress Report No. 22. Bloomington: Indiana University, Department of Psychology, Speech Research Laboratory; 1996. Static vs. dynamic faces as retrieval cues in recognition of spoken words; pp. 141–177. [Google Scholar]

- Lachs L. Research on spoken language processing. Progress Report No. 23. Bloomington: Indiana University, Department of Psychology, Speech Research Laboratory; 1999. A voice is a face is a voice; pp. 81–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lachs L, Hernández LR. Research on spoken language processing. Progress Report No. 22. Bloomington: Indiana University, Department of Psychology, Speech Research Laboratory; 1998. Update: The Hoosier Audiovisual Multitalker Database; pp. 377–388. [Google Scholar]

- Lachs L, Pisoni DB, Kirk KI. Use of audiovisual information in speech perception by prelingually deaf children with cochlear implants: A first report. Ear and Hearing. 2001;22(2):236–251. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200106000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman AM, Cooper FS, Shankweiler DP, Studdert-Kennedy M. Perception of the speech code. Psychological Review. 1967;74:431–461. doi: 10.1037/h0020279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce PA, Pisoni DB. Recognizing spoken words: The neighborhood activation model. Ear and Hearing. 1998;19:1–36. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199802000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaro DW, Cohen MM. Perceiving talking faces. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4(4):104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Massaro DW, Cohen MM. Speech perception in perceivers with hearing loss: Synergy of multiple modalities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999;42:21–41. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4201.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaro DW, Cohen MM. Tests of auditory-visual integration efficiency within the framework of the fuzzy logical model of perception. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2000;108:784–789. doi: 10.1121/1.429611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk H, MacDonald JW. Hearing lips and seeing voices. Nature. 1976;264:746–748. doi: 10.1038/264746a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullennix JW, Pisoni DB. Stimulus variability and processing dependencies in speech perception. Perception & Psychophysics. 1990;47:379–390. doi: 10.3758/bf03210878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullennix JW, Pisoni DB, Martin CS. Some effects of talker variability on spoken word recognition. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1989;85:365–378. doi: 10.1121/1.397688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusbaum HC, Pisoni DB, Davis CK. Research on speech perception. Progress Report No. 10. Bloomington: Indiana University, Department of Psychology, Speech Research Laboratory; 1984. Sizing up the Hoosier mental lexicon: Measuring the familiarity of 20,000 words; pp. 357–376. [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard LC, Pisoni DB. Talker- and task-specific perceptual learning in speech perception. International Congress on Phonetic Sciences. 1995;95(1):194–197. (Section 9.5) [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard LC, Pisoni DB. Talker-specific learning in speech perception. Perception & Psychophysics. 1998;60:355–376. doi: 10.3758/bf03206860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard LC, Sommers MS, Pisoni DB. Speech perception as a talker-contingent process. Psychological Science. 1994;5(1):42–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1994.tb00612.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard LC, Sommers MS, Pisoni DB. Effects of stimulus variability on perception and representation of spoken words in memory. Perception & Psychophysics. 1995;57:989–1001. doi: 10.3758/bf03205458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB. Long-term memory in speech perception: Some new findings on talker variability, speaking rate, and perceptual learning. Speech Communication. 1993;13:109–125. doi: 10.1016/0167-6393(93)90063-q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB. Some thoughts on “normalization” in speech perception. In: Johnson K, Mullenix W, editors. Talker variability in speech processing. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Remez RE, Fellowes JM, Pisoni DB, Goh WD, Rubin P. Multimodal perceptual organization of speech: Evidence from tone analogs of spoken utterances. Speech Communication. 1998;26:65–73. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6393(98)00050-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remez RE, Rubin P, Pisoni DB, Carrell TD. Speech perception without traditional speech cues. Science. 1981;212:947–950. doi: 10.1126/science.7233191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remez RE, Rubin PE, Berns SM, Pardo JS, Lang JM. On the perceptual organization of speech. Psychological Review. 1994;101:129–156. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.101.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum LD, Saldaña HM. An audiovisual test of kinematic primitives for visual speech perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1996;22:318–331. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.22.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon RV, Zeng FG, Kamath V, Wygonski J, Ekelid M. Speech recognition with primarily temporal cues. Science. 1995;270:303–304. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffert SM, Lachs L, Hernández LR. Research on spoken language processing. Progress Report No. 21. Bloomington: Indiana University, Department of Psychology, Speech Research Laboratory; 1996. The Hoosier Audiovisual Multitalker Database; pp. 578–583. [Google Scholar]

- Sommers MS, Kirk KI, Pisoni DB. Some considerations in evaluating spoken word recognition by normal-hearing, noise masked normal hearing and cochlear implant listeners. I: The effects of response format. Ear and Hearing. 1997;18:89–99. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199704000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers MS, Nygaard LC, Pisoni DB. Stimulus variability and spoken word recognition. I: Effects of variability in speaking rate and overall amplitude. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1994;96:1314–1324. doi: 10.1121/1.411453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein BE, Meredith MA. The merging of the senses. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sumby WH, Pollack I. Visual contribution to speech intelligibility in noise. Journal of Acoustical Society of America. 1954;26:212–215. [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield Q. Some preliminaries to a comprehensive account of audio-visual speech perception. In: Dodd B, Campbell R, editors. Hearing by eye: The psychology of lip-reading. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1987. pp. 3–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler RS, Fryauf-Bertschy H, Kelsay DM, Gantz B, Woodworth G, Parkinson A. Speech perception by prelingually deaf children using cochlear implants. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 1997;117(3 Part 1):180–187. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(97)70172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler RS, Parkinson AJ, Woodworth GG, Lowder MW, Gantz BJ. Performance over time of adult patients using the Ineraid or nucleus cochlear implant. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1997;102:508–522. doi: 10.1121/1.419724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson CS, Qiu WW, Chamberlain MM, Li X. Auditory and visual speech perception: Confirmation of a modality-independent source of individual differences in speech recognition. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1996;100:1153–1162. doi: 10.1121/1.416300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]