Abstract

Current theories and models of the structural organization of verbal short-term memory are primarily based on evidence obtained from manipulations of features inherent m the short-term traces of the presented stimuli, such as phonological similarity. In the present study, we investigated whether properties of the stimuli that are not inherent in the short-term traces of spoken words would affect performance in an immediate memory span task. We studied the lexical neighbourhood properties of the stimulus items, which are based on the structure and organization of words in the mental lexicon. The experiments manipulated lexical competition by varying the phonological neighbourhood structure (i.e., neighbourhood density and neighbourhood frequency) of the words on a test list while controlling for word frequency and intra-set phonological similarity (family size). Immediate memory span for spoken words was measured under repeated and nonrepeated sampling procedures. The results demonstrated that lexical competition only emerged when a nonrepeated sampling procedure was used and the participants had to access new words from their lexicons. These findings were not dependent on individual differences in short-term memory capacity. Additional results showed that the lexical competition effects did not interact with proactive interference. Analyses of error patterns indicated that item-type errors, but not positional errors, were influenced by the lexical attributes of the stimulus items. These results complement and extend previous findings that have argued for separate contributions of long-term knowledge and short-term memory rehearsal processes in immediate verbal serial recall tasks.

One of the major assumptions of current verbal short-term memory (STM) models is the proposal that words are coded and represented in a phonological form in immediate memory. For example, in Baddeley and Hitch’s (1974) well-known “working” memory model, they propose a specific mechanism called the “phonological (or articulatory) loop” to support the retention of verbal lists on a temporary basis. The impetus for positing specific mechanisms to handle phonological coding of words stems from a number of robust findings in the STM literature. These include the phonological similarity effect (e.g.,Baddeley, 1966; Conrad, 1964), the word length effect (Baddeley, Thomson, & Buchanan, 1975), the unattended speech effect (Salamé & Baddeley, 1982, 1987, 1989), and the articulatory suppression effect (Baddeley, Lewis, &Vallar, 1984).

The Interpretations given to these diverse findings on immediate memory span have not gone unchallenged (see, e.g., Caplan, Rochon, & Waters, 1992; Caplan & Waters, 1994; Cowan, Wood, Nugent, & Treisman, 1997; Lovatt, Avons, & Masterson, 2000; Nairne, Neath, & Serra, 1997, for alternative accounts of the word length effect; Bavelier & Potter, 1992, for articulatory suppression and phonological similarity; and Bridges & Jones, 1996, for unattended speech). However, the prevailing approach to investigating working memory may not reveal the contribution of more abstract underlying factors that are beyond the physical properties of the specific experimental stimuli. These factors include the organizational structure of the mental lexicon as a whole and the statistical distribution of the properties that define each individual word with respect to the entire lexicon (Luce & Pisoni, 1998; Pisoni, Nusbaum, Luce, & Slowiaczek, 1985). For example, word frequency does not exist as an inherent property of the set of experimental stimuli hut is a function of long-term acquisition and experience of a participant. Yet, word frequency has been repeatedly demonstrated to influence immediate memory span tasks. Memory span for high-frequency words is consistently longer than the memory span for low-frequency words (e.g., Engle, Nations, & Cantor, 1990; Hulme et al., 1997). The effects of word frequency and the contribution of the structural organization of words in the mental lexicon have generally been considered to fall within the domain of the more permanent long-term memory (LTM) system and are, therefore, not given much consideration when describing the properties and operations of STM processes.

However, recent investigations have indicated that the structure of LTM representation affects STM tasks, and several researchers have begun to describe in detail the interaction between LTM and STM processes (e.g., Bourassa & Besner, 1994; Gathercole, Frankish, Pickering, & Peaker, 1999; Gupta & MacWhinney, 1997; Hulme, Maughan, & Brown, 1991; Hulme et al., 1997; Poirier & Saint-Aubin, 1995; Schweickert, 1993). In general, these studies have demonstrated that information about words stored in the mental lexicon can facilitate the recall of verbal information in STM. Immediate memory span for nonwords or words from an unfamiliar language is significantly lower than memory span for familiar words (Hulme et al., 1991). Immediate memory span is also affected by the semantic attributes of words (Bourassa & Besner, 1994; Poirier& Saint-Aubin, 1995; Walker & Hulme, 1999), phonotactic properties (Gathercole et al., 1999), and word frequency (Hulme et al., 1997). Lexical status, phonotactic information, and word frequency are all assumed to be stored with the memory trace of the word in the mental lexicon in LTM. Using the framework of Schweickert’s (1993) multinomial processing tree model of immediate recall, one could argue that such properties of the long-term traces of words are used to aid in the “redintegration” of decayed traces in STM and, thus, facilitate their subsequent retrieval and recall. For example, items that do not have a lexical representation in LTM, such as nonwords, would not have the additional advantage of permanent traces to aid in the recall process and would, therefore, produce lower memory spans (see also Schweickert, Chen, & Poirier, 1999).

Other evidence suggests that the contribution of LTM factors to memory span performance is independent of mechanisms postulated to be critical for STM recall. For example, speech rate has been shown to be positively correlated to STM span (e.g., Baddeley et al., 1975). Baddeley has argued that this is evidence for the contribution of the limited capacity articulatory loop and rehearsal processes in the working memory model (Baddeley, 1986; 1998). The faster that one can rehearse items in the loop, the less susceptible to decay the items will be. Hulme et al. (1991) found that the slope of the speech rate recall function was equivalent for both word and nonword items and interpreted this result as evidence for the equal contribution of rehearsal processes to both words and nonwords. However, the intercept of the speech rate recall function for nonwords was lower than the function for words, suggesting an additive and independent contribution of lexicality to STM performance. Bourassa and Besner (1994) also demonstrated that content words were recalled better than function words in an immediate serial recall task, but recall of both types of word was equally impaired by articulatory suppression. This result was interpreted as support for the independent contribution of semantic coding to STM span performance—articulatory suppression affected rehearsal processes but did not interact with the semantic attributes of the items to be recalled.

Lexical neighbourhoods of spoken words

Given the increasing evidence for LTM contributions to STM performance, it is important to investigate how the phonological properties of words are stored and organized in LTM, since phonological coding has long been considered the primary code for STM. One way to describe the long-term phonological information about a word is to consider the notion of lexical neighbourhoods defined by phonological similarity (Landauer & Streeter, 1973; Luce & Pisoni, 1998; Treisman, 1978). A similarity neighbourhood is an equivalence classification that is defined by the number of words that can be obtained by substituting one phoneme position in the target word or by the single addition or deletion of a phoneme (see also Coltheart, Davelaar, Jonasson, & Besner, 1977, for orthographic neighbourhoods). For example, the neighbours of the word cat would include hat, cut, and cap by one phoneme substitution, and scat and at by one phoneme addition/deletion.

Luce and Pisoni’s (1998) Neighbourhood Activation Model (NAM) of spoken word recognition assumes the presence of lexical competition among phonologically similar words. The basic assumptions of the NAM model include the proposition that words in the mental lexicon are organized and stored in terms of the similarity neighbourhoods, and that the LTM representations of words will contain many overlapping phonetic features if they are from the same lexical neighbourhood. Word recognition is assumed to involve a competitive discrimination process among the individual lexical items in LTM (Luce & Pisoni, 1998; Vitevitch & Luce, 1998). According to NAM, when a stimulus pattern is parsed during word recognition, all representations with similar features get activated. Through a process of lexical competition, a particular word wins and is recognized. The speed and accuracy of recognition is directly dependent on the lexical neighbourhood properties of the target word (Luce & Pisoni, 1998). The key assumption of the NAM model of spoken word recognition is that words are recognized “relationally” through a process of lexical discrimination and selection—that is, words are recognized in the context of other phonologically similar words that are present in the mental lexicon.

The structure of a lexical neighbourhood can be characterized in terms of its density and frequency (Luce & Pisoni, 1998). Neighbourhood density refers to the number of words in a similarity neighbourhood. Dense neighbourhoods contain many phonologically similar sounding words while sparse neighbourhoods contain fewer phonologically similar sounding words. Neighbourhood frequency refers to the average frequency of occurrence of words in a similarity neighbourhood. High-frequency neighbourhoods contain primarily high-frequency words, while low-frequency neighbourboods contain primarily low-frequency words. Finally, word frequency is an individual word’s frequency of occurrence in the language based on text count (e.g., Kucera & Francis, 1967) and should not be confused with neighbourhood frequency, which is the average frequency of the word’s neighbours.

Based on these three structural properties, words can be classified into those items that would be “easy” or “hard” to recognize, depending on the degree of lexical competition. “Easy words” are words that “stand out” because they arc higher in frequency relative to their neighbours, and they also have few neighbours. These words reside in low density and low-frequency neighbourhoods. In contrast, “hard words” tend to get “swamped” by their neighbours because of their lower relative frequency and the crowded neighbourhood they live in. These words reside in high-density and high-frequency neighbourhoods in the lexicon.

Lexical competition has been shown to influence spoken word recognition in a variety of behavioural tasks, including accuracy in perceptual identification (Landauer & Streeter, 1973; Luce & Pisoni, 1998), naming and lexical decision latency (Cluff & Luce, 1990; Luce, Pisoni, & Goldinger, 1990), priming (Goldinger, Luce, & Pisoni, 1989; Goldinger, Luce, Pisoni, & Marcario, 1992), and phonetic/phonological reduction in speech (Wright, 1997). Taken together, the overall pattern of results suggests that words are recognized relationally in the context of other words in the lexicon—that is, words compete for recognition (Luce & Pisoni, 1998; Vitevitch & Luce, 1998).

Would the lexical neighbourhoods of spoken words have an effect on STM processes? One might ask why the similarity neighbourhoods of spoken words should continue to exert an influence once a word has been recognized. In the typical immediate memory span tasks used in STM studies, the spoken words are recognized very rapidly, long before the participant is required to actually recall the list of items. Since the words are already recognized, why should their lexical neighbours continue to affect anything?

If we can demonstrate that lexical competition does, in fact, influence immediate memory span, then two things become clear in terms of theoretical implications. First, lexical neighbourhood effects persist beyond initial word recognition. Second, the processes involved in immediate memory span tasks are also influenced by phonological information about words in LTM and not just the short-term phonological traces of the words.

It is important to emphasize here the differences in how words are selected by an experimenter in phonological similarity studies on immediate memory span and how they are selected in word recognition studies. In a typical STM experiment that investigates phonological similarity effects, phonologically similar words are picked from one lexical neighbourhood to maximize their phonetic similarity, while the phonologically dissimilar words are picked from different neighbourhoods to maximize their phonetic dissimilarity. In contrast, for experiments on spoken word recognition that examine the effects of lexical competition, “easy” and “hard” lists are both picked from multiple neighbourhoods. The lists used in these studies are therefore equivalent to the “dissimilar” word lists in phonological similarity experiments. If there is any disparity in performance on “easy” and “hard” words, it is not because of short-term phonological traces. Rather, differences in performance are caused by the contribution of long-term phonological neighbourhood properties of the specific items used in these lists and lexical competition among phonologically similar words.

Several years ago, Goldinger, Pisoni, and Logan (1991) examined the effects of talker variability on serial recall of 10-word lists using several presentation rates. In their study, they included a lexical manipulation that involved the use of “easy” and “hard” words. The effects of talker variability reported in their paper are not relevant to this study, but there were several effects of the lexical neighbourhood factor (“easy” vs. “hard” word lists) that warrant further discussion, First, Goldinger et al. (1991) found a main effect of lexical neighbourhood. Recall of “easy” word lists was higher than that of “hard” word lists. Second, they found that lexical neighbourhood did not interact with presentation rate, indicating that the “easy” word advantage was not affected by changes in the speed of presentation and, hence, the strength of encoding and rehearsal. Third, they found an interaction between lexical neighbourhood and serial position. There was a larger “easy” word advantage in the primacy region of the serial position curve. Goldinger et al. (1991) suggested that this interaction may reflect the effects of long-term phonological neighbourhoods and lexical competition on rehearsal processes, since the early list items would presumably have received the greatest amount of rehearsal. But the results could also be due to an interaction between STM rehearsal and retrieval from LTM, since the primacy effect is generally interpreted as reflecting the transfer of information from STM to LTM. It should be noted here that Goldinger et al. (1991) used a constant list length of 10 words in their recall experiment, which is generally considered to be a “superspan” task that is beyond the STM capacity of most people. However, no data on the participants’ STM capacity was ever collected, so it was not possible to determine whether the contribution of long-term phonological neighbourhoods and lexical competition to serial recall performance was independent of STM capacity.

The initial findings of Goldinger et al. (1991) on lexical neighbourhoods provided part of the motivation for the current series of experiments. One way to investigate whether lexical neighbourhoods influence STM processing is to determine whether individual differences in STM capacity are associated with the size of the difference between memory spans for word lists that differ on the degree of lexical competition. If lexical competition interacts with STM processing, one might expect a significant relationship between STM capacity and the difference in memory span for “easy” and “hard” word lists. If lexical competition makes an independent contribution to immediate memory span for words, then there should be no relationship between STM capacity and the “easy–hard” memory span differences. Data on individual differences would provide important new evidence for the contribution of LTM factors to STM processing—specifically, whether differences in STM capacity are related to immediate memory span of word lists that differ in lexical competition.

Repeated and nonrepeated sampling

We now turn to the second motivation for the current study. Many of the memory span studies described above used a repeated sampling procedure—that is, the experimenter selects a small fixed number of words, which are then used repeatedly from trial to trial or from list to list in the experiment. Some years ago, Drewnowski and Murdock (1980) noted that this procedure might turn the experimental stimuli into a very restricted set and might induce participants to encode or retrieve the words in a task-specific manner based on partial information of each item and their knowledge of the restricted stimulus set. If participants know that the same five words are going to be used on the lists over and over again, it might be sufficient for them to simply encode or maintain the stimulus features that distinguish one item from the other within the set, since these features can subsequently be retrieved and mapped onto the appropriate token, LTM effects may therefore be attenuated or even eliminated under these presentation conditions. Item repetition may also increase proactive interference (PI) from previous lists because the same small set of words are used over and over except for differences in presentation order. This observation applies to the traditional digit-span tests of immediate memory as well, although the list often digits from 0 to 9 forms a naturally closed set of items. The role of interference and inhibition mechanisms may be an important consideration in elucidating the nature of memory processing (e.g., Hasher & Zacks, 1988).

If the test words are unique from trial to trial, then each token is only accessed from LTM and activated once, and limited coding and PI will not obscure the influence of its LTM representation. In fact, Nairne et al. (1997) recently argued that PI played a role in the word length effect for repeated lists because the word length effect only emerged after many trials and was not apparent in the initial trials of an experiment. They proposed that participants were directly recovering list information from LTM without any interference in the initial trials. Their suggestion is similar to the explanation of the results of an earlier memory study by La Pointe and Engle (1990), who showed that the word length effect was not abolished by articulatory suppression for nonrepeated lists. By using new words for each list, the effects of PI and limited coding were minimized. It is quite plausible that articulatory suppression would not be expected to have any effects at all if the words were being retrieved directly from LTM for each list of new items.

Recently, Cowan et al. (1998) suggested that the preservation of the word length effect for nonrepeatcd lists despite articulatory suppression could be due lo output or decay effects on the phonological traces—that is, longer words may be more susceptible to decay since they take a longer time lo output. Articulatory suppression would only affect rehearsal processes, which in turn are essential for maintaining words in their correct order. Rehearsal may be more critical for reducing PI under repeated sampling because all items would remain active in STM, and the features that distinguish the current list from previous lists would only be the order of the items and not the individual items themselves. The phonological traces alone may not be useful in recall, and thus the word length effect would disappear with articulatory suppression. In contrast, when new words are always used on each list, the unique phonological traces of the current list may be sufficiently distinct from previous lists’ traces to help in recall, despite the interference of rehearsal processes under articulatory suppression.

Differences in recall performance between repeated and nonrepeated sampling procedures are not consistent in the literature. Coltheart (1993) found that the phonological similarity effect persisted under both repeated and nonrepeated conditions. However, in Coltheart’s study, her pool of phonologically similar words in the nonrepeatcd condition was essentially drawn from one large lexical neighbourhood. So it was not surprising that the similarity of the unique tokens from one list to another caused interference. More recently, Nairne and Kelley (1999) reported that the phonological similarity effect could be reversed under certain experimental conditions using a nonrepeated sampling procedure. By using a delayed recall task and varying the retention interval, the advantage of phonologically dissimilar tokens over phonologically similar items actually reversed at the longest retention interval of 24 s. Nairne and Kelley’s (1999) explanation of this pattern was that the similarity of phonological features can be an effective retrieval cue for discriminating words between lists, while it may produce impairments for discriminating words within lists. Another study by Roodenrys and Quinlan (2000) that manipulated word frequency and sampling repetition found that the effect of frequency did not entirely disappear under repeated sampling, although the frequency effect was larger under nonrepeated sampling. Low-frequency words were also recalled better under repeated sampling than under nonrepeated sampling whereas there was no difference in the recall of high-frequency words under either sampling conditions.

Taken together, these findings suggest that it may be informative to examine differences in performance using both repeated and nonrepeated sampling techniques in studies of STM or working memory. Any LTM effects are probably going to be strongest when using nonrepeated sampling since this procedure minimizes the effects of PI and the use of limited or item-specific coding strategies. In fact, the recent findings of Sommers, Kirk, and Pisoni (1997) support this assertion. Using a perceptual identification task, Sommers et al. demonstrated that participants who used a “closed-set” response format (i.e., they bad to identify a presented word from a set of six possible targets) showed no performance difference in identifying “easy” and “hard” spoken words mixed in noise over a range of signal-to-noise ratios. However, participants who used an “open-set” response format (i.e., they bad to identify a presented word without any available response alternatives) showed a consistent performance advantage for “easy” over “hard” words for the same set of items.

Sommers et al. (1997) argued that the closed-set response format effectively eliminated the need to access LTM since the search is only limited to the given set of possible responses. Under closed-set conditions, the words were no longer competing with other words in LTM, and thus there was no need to access the neighbourhood structure of the lexicon. On the other hand, under the open-set response format, the search space may be thought of as essentially the listener’s entire lexicon of words in the language. Not surprisingly, in the Sommers et al. experiments, the structural organization of words in the lexicon influenced performance in open-set conditions, and large differences in speech intelligibility were observed between the “easy” and “hard” words. An examination of lexical competition effects under both repeated and nonrepeated sampling conditions is important because the nature of the task demands and memory processes recruited may be substantially different under these two presentation formats.

EXPERIMENT 1

Experiment 1 was designed to investigate whether an interaction would be observed between lexical competition and the sampling procedure used in immediate memory span for spoken words. We manipulated lexical competition by using test lists made up of only “easy” words or only “hard” words. To ensure that any effect on memory span for spoken words can be attributed to the lexical neighbourhood structure of words in LTM per se, rather than to intra-list influences (i.e., lexical family size), the word lists were constructed so that the “easy-hard” distinction referred to differences in global neighbourhood density and neighbourhood frequency. The average word frequency and the average number of intra-set neighbours—that is, the number of words within the chosen words that were phonological neighbours of each other—were equated across both “easy” and “hard” word lists. We also manipulated the sampling procedure by using repeated and nonrepeated items. We hypothesized an interaction between sampling procedure and lexical competition and predicted that the difference in word spans between the “easy” and “hard” word lists would only be observed under the nonrepeated sampling procedure. Lexical competition effects were expected to he minimal under repeated sampling conditions because this procedure effectively makes the limited pool of words a closed response set and therefore changes the nature of the task demands substantially compared to nonrepeated sampling which uses an open-set response format.

Method

Participants

A total of 56 undergraduates from the Psychology Department at Indiana University participated in the study for course credit. All were native English speakers with no speech or hearing disorder at the time of testing.

Materials

The set of test words was obtained from a prerecorded digital speech database that contained 300 monosyllabic English words from the Modified Rhyme Test (House, Williams, Hecker,& Kryter, 1965) and from phonetically balanced word lists (Egan, 1948). A set of 66 “easy” CVC words and a set of 66 “hard” CVC words spoken by one mate talker were selected so that the mean properties of the two sets differed on neighbourhood density and neighbourhood frequency but were equated on word frequency and the number of intra set neighbours (lexical family size). All of these words were used in the nonrepeated sampling conditions. In selecting the eight-word sets for the repeated sampling conditions, it was not possible to fully equate the small sets of words with the larger sets in terms of the number of intra-set neighbours. To obtain an approximate balance for all sets of words, we ensured that the proportion of words with at least one intra-set neighbour was roughly equal. For the larger 66-word sets, 94% of the “hard” words had at least one intra-set neighbour, and 88% of the “easy” words had at least one intraset neighbour. We ensured that seven of the eight words in the eight-word sets for both “easy” and “hard” words had at least one intra-set neighbour, which accounts for 88% of each set and is therefore a rough approximation to the distribution in the 66-word sets. The word lists and their structural properties are listed in the **Appendix.

Tokens of the 10 spoken digits (0 to 9) used in the digit-span task were obtained from the Texas Instruments 46-Word (TI46) Speaker-Dependent Isolated Word Corpus (Texas Instruments, 1991). The overall RMS (root-mean-square) amplitude levels for each digit token were digitally equated with the word tokens to ensure equal presentation levels.

Apparatus

Gateway 2000 Pentium 133-MHz IBM-compatible computers equipped with 15-inch Vivitron SVGA monitors and SoundBlaster A WE32 sound cards were used to control the experiment. The auditory stimuli were presented to participants via a pair of Beyer Dynamic DT100 headphones at approximately 75 dB SPL.

Design

The experiment employed a 2 × 2 mixed factorial design. The sampling independent variable (repeated vs. nonrepeated) was run between subjects while the word type independent variable (“easy” vs. “hard”) was run within subjects. Digit-spans were also obtained from all subjects as a baseline measurement of STM capacity. This was necessary to ensure that the subjects assigned to the two sampling conditions did not differ in STM capacity as measured by the traditional digit-span tests.

Procedure

Participants were tested individually or in small groups of five or fewer. The digit-span test was always done first, followed by the word-span tests. The “easy–hard” order of presentation for the word-span tests was counterbalanced across participants.

The procedure used in these tests followed the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Wechsler, 1955) method of increasing the list length by one item after every two trials. For example, our digit-span test started with a list length of four digits. This constituted one trial. The second trial was also a list of four digits. The third trial was a list of five digits, and so on. The digit-span test began with a list length of 4 digits and ended with a length of 10, resulting in a total of 14 trials for each test. The “easy” and “hard” word-span tests began with a list length of three words and ended at a length of eight, resulting in 12 trials for each test.

During a given trial, the computer presented each stimulus item with an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 500 ms. The tokens were randomly presented to the participants via the headphones. Within a single trial for all conditions, the stimuli were sampled without replacement from the current pool. In the digit-span tests and the repeated-sampling condition, all stimulus items were returned to the pool after the completion of a trial, and the next trial began by sampling again from this pool. In the nonrepeated sampling condition, items that were previously used were never returned to the pool. Thus, repeated and nonrepeated samplings refers to repetition across trials and not within trials. Within a single trial, no items were ever repeated on a given test list.

Participants were told to memorize the list of words because they would be required to reproduce all the words on the list in the correct sequential order. Participants wrote down their responses on prepared answer booklets at the end of each trial. Participants initiated the next trial by pressing a key on the computer keyboard.

Data scoring

A response was considered to be correct if its identity and sequence position were both recalled accurately. Four different scoring procedures adapted from the methods originally described in La Pointe and Engle (1990)—highest, strict, absolute, and total span—were used to summarize the data. The pattern of results observed using the mean span scores was identical for all four scoring procedures, so we only report the analyses of the total span scores—obtained by counting the total number of Items recalled correctly regardless of whether the trial was perfectly recalled.

Results

Digit-Span scores

The mean digit-spans for participants assigned to the repeated and nonrepeated sampling conditions were 70.86 (SD = 10.14) and 69.50 (SD = 7.42), respectively. An independent groups t test showed that the average STM capacity of the two groups of participants was equivalent, t < 1.

Lexical neighbourhood and item repetition

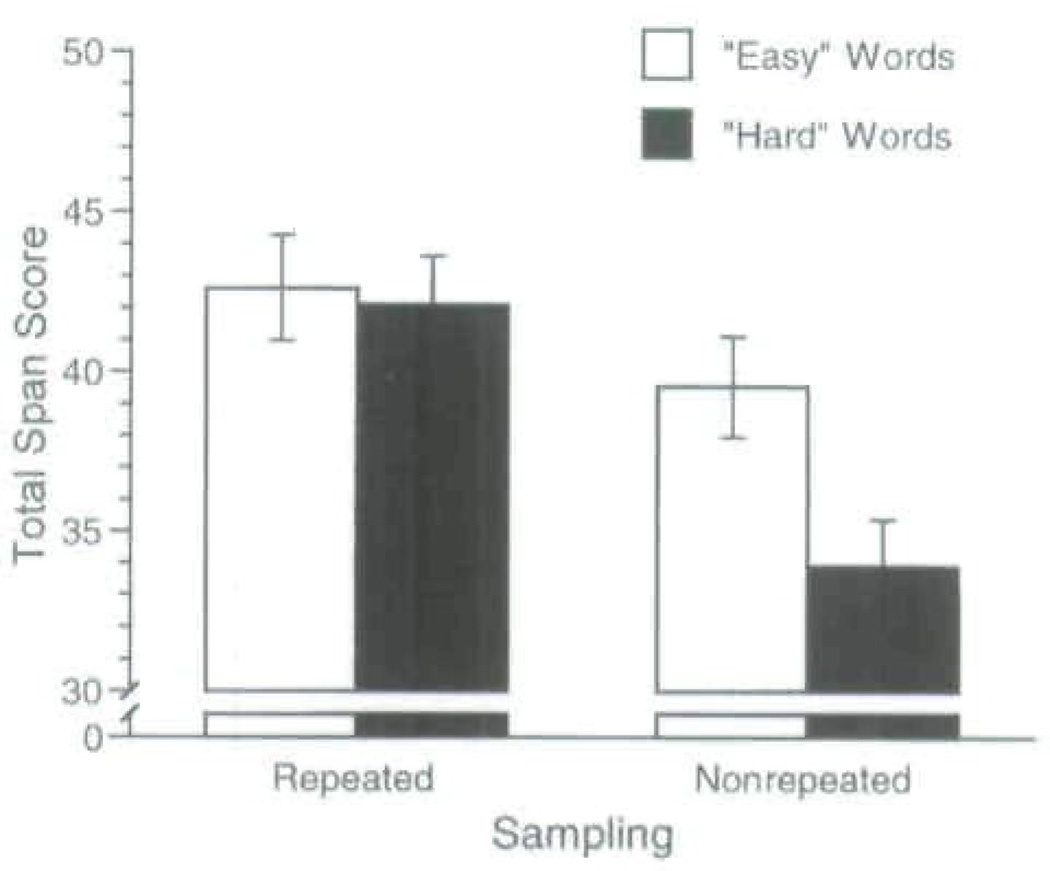

Figure 1 shows the interaction between the sampling and word type conditions, This interaction was significant in a two-way mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA), F(1, 54) = 10.32, MSE = 17.94, p < .01. Tests of simple effects indicated that the source of the interaction was the difference between the “easy” and “hard” word-spans in the nonrepeated sampling condition, F(1, 54) = 24.85, MSE = 17.94, p < .001, and the difference between repeated and nonrepeated sampling performance on “hard” word-spans, F(1, 54) = 15.10, MSE = 62.54, p < .001. None of the other simple effects were significant, all Fs < 1.9. This pattern of results indicates that the effect of lexical competition on memory span was confined to the nonrepeated sampling condition.

Figure 1.

Mean total span score (+SE) as a function) of sampling and word type in Experiment 1.

To elucidate the relationship between individual differences in STM capacity and the effects of lexical competition on memory span, we determined whether the magnitude of the difference between “easy” and “hard” word-span scores for each participant in the nonrepeated sampling condition was correlated with their digit-span scores. To do this analysis, we took each participant’s “hard” word-span score and subtracted it from their “easy” word-span score to obtain the “easy–hard” lexical difference. We then correlated this difference score with the corresponding digit-span score. Participants with larger memory capacities might show smaller “easy–hard” lexical differences than participants with smaller memory capacities. If this is correct, we would expect a negative correlation between digit-span and the “easy–hard” lexical difference. However, the “easy–hard” difference score was not significantly correlated with the digit-span score, r(28) = .09, so we are confident that STM capacity, at least as measured by digit-span, did not significantly contribute to the “easy–hard” lexical difference observed in the nonrepeated sampling condition.

Effects of list length

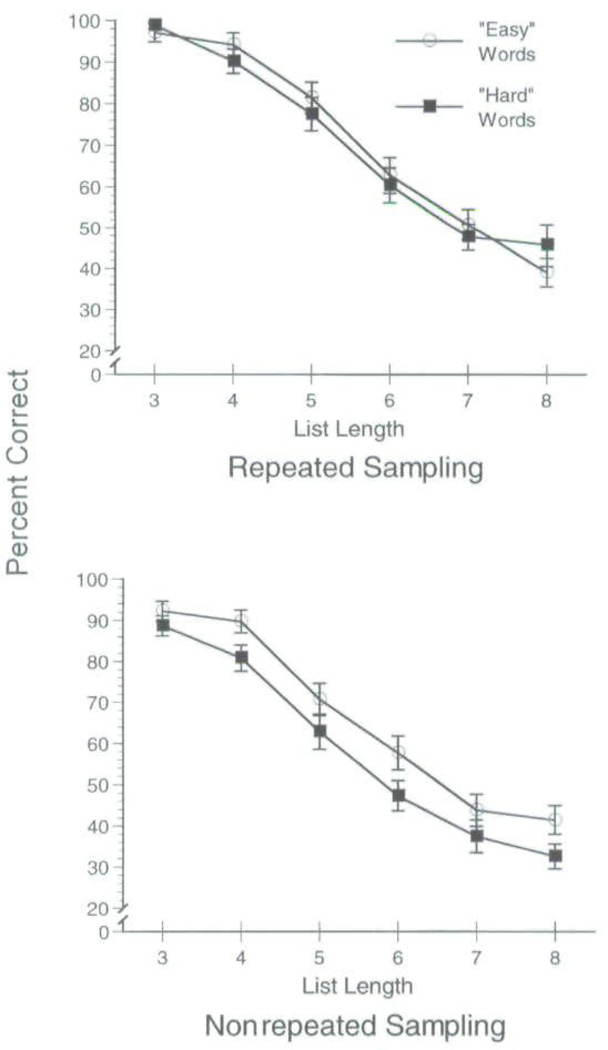

We next analysed the performance of the “easy” and “hard” word-spans across each list length. Figure 2 shows the recall performance for the different word types at each list length under the two sampling conditions. The number of words correctly recalled across the two trials at each list length was summed and converted to a percentage correct score. A three-way mixed-design ANOVA (Sampling × Word Type × List Length) revealed significant main effects of word type, F(1, 54) = 13.14, MSE = 230.90, p < .01, and list length, F(5, 270) = 181.85, MSE = 317.09, p < .001. More importantly, the interaction between word type and sampling was also significant, F(1, 54) = 8.57, MSE = 230.90, p < .01. None of the other interactions and main effects were significant. The absence of a significant three-way interaction between list length, word, and sampling condition indicated that the magnitude of the “easy–hard” lexical difference remained essentially the same across the Word × Sampling interaction.

Figure 2.

Mean percentage recall (+SE) as a function of list length, sampling, and word type in Experiment 1.

Error analyses

To obtain additional information about the locus of the lexical competition effects, we examined the recall errors made by participants in the word-span tasks. The mechanisms of the phonological loop as specified by the Baddeley and Hitch (1974) model of working memory are assumed to be important for maintaining serial order information by way of rehearsal processes. If the locus of the lexical effects is found in mechanisms that operate separately from STM, such as the structural organization of words in LTM, one would expect them to influence item-type errors rather than order or positional errors. These responses would include substitution or neighbourhood errors, and it is reasonable to expect that “hard” words might be more susceptible to these errors than “easy” words because they have denser phonological neighbourhoods and are therefore more confusable with each other due to the increased competition among phonologically similar words.

Order errors should not be affected by lexical factors if the locus of the neighbourhood effects is not dependent on the maintenance of serial order information in STM. Furthermore, since the lexical neighbourhood effects only emerge under nonrepeated sampling conditions, it is reasonable to expect that order errors may also be more prominent than item errors for both “easy” and “hard” word lists in the repeated sampling condition. On the other hand, if the lexical competition effects primarily influence order rather than item accuracy, this error pattern would suggest that the lexical factors interact with STM mechanisms that are responsible for the maintenance of serial order information. In other words, the locus of the lexical competition effects is not just in the structural organization of words in LTM but also influences the positional coding of items in STM.

We classified all errors made by participants into four mutually exclusive categories. An order error was a response where a presented word was correctly recalled but in the wrong serial position. An omission error was a response where participants did not recall any word in that serial position. An intrusion error was a response where a word that was not presented on the current list was recalled. A neighbourhood error was a response where the recalled word differed by a single phoneme from the word presented in the same serial position on the current list. The last two categories can be considered item-type errors. Most of these categories are commonly used for error analyses in the literature (e.g., Henson, 1998, 1999).

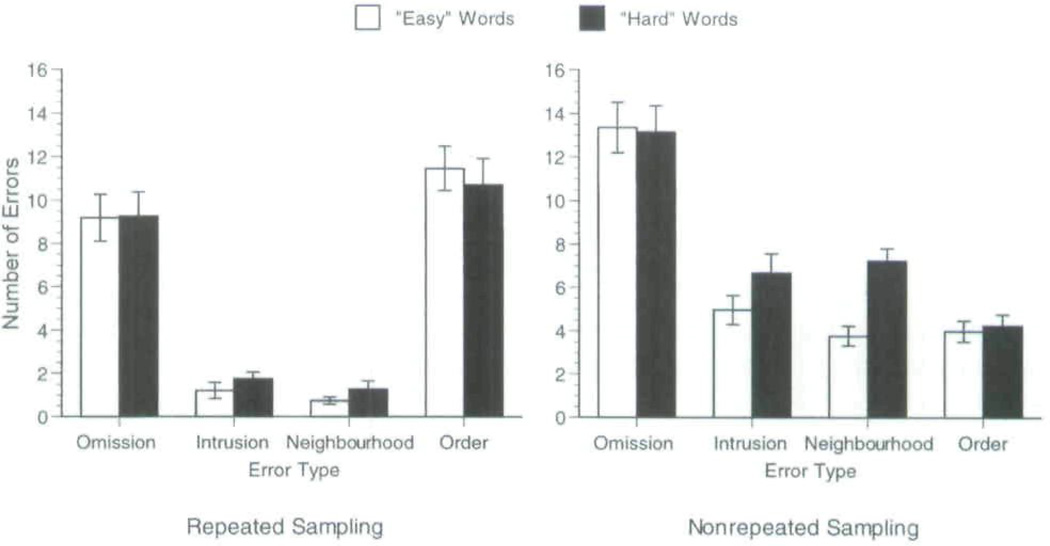

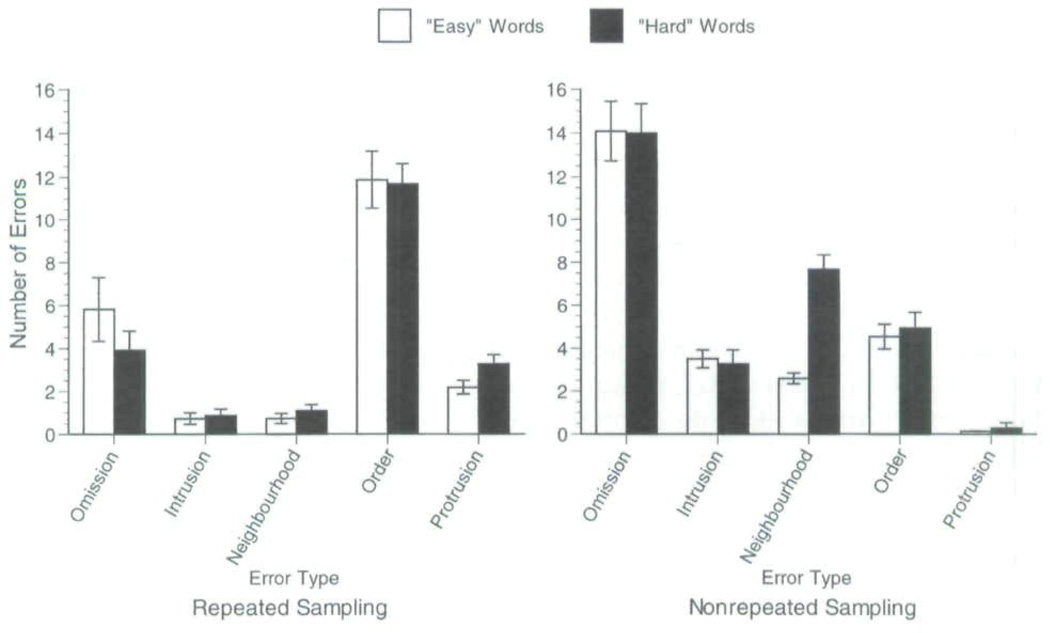

Figure 3 shows the average number of error types made by participants under the two sampling conditions for the “easy” and “hard” word lists. A three-way mixed design ANOVA revealed a significant Word Type × Terror Type × Sampling interaction, F(3, 162) = 3.71, MSE = 8.47, p < .05. To identify the source of the three-way interaction, tests of simple effects between the “easy” and “hard” words for each type of error were performed for each sampling condition separately. Under the repeated sampling condition, none of the simple effects were significant, indicating that there were no differences between “easy” and “hard” words for any of the four error types. It is also clear from an inspection of Figure 3 that there were many more order errors than item errors in the repeated sampling condition. These results confirmed our prediction that the lexical effects would not influence the types of error made under repeated sampling conditions, and that the errors in this condition would be primarily positional in nature.

Figure 3.

Average number of errors (+SE) for Experiment 1 in the repeated and nonrepeated sampling conditions.

Under the nonrepeated sampling condition, however, significant simple effects of word type for intrusion and neighbourhood errors were observed, all Fs(1, 27) > 8.1, MSEs < 6.0, ps < .01. Figure 3 shows that there were more item errors for “hard” words than for “easy” words. The simple effects of word type for omission and order errors were not significant, all Fs < 1. This critical result indicates that the “easy–hard” manipulation only influenced item errors and not order errors—-there was no significant difference between “easy” and “hard” words for order errors. Figure 3 also clearly shows that more item errors than order errors occurred in the nonrepeated sampling condition as we predicted.

Discussion

The pattern of results obtained in this immediate word-span experiment demonstrates that the lexical neighbourhood properties of the stimulus items used on a test list exert a large and systematic influence on immediate memory span beyond the recognition of individual words, especially when the use of limited coding and PI is minimized by using a nonrepeated sampling procedure. In particular, two findings strongly suggest that these lexical competition effects are not influenced by memory capacity. First, the correlations between the magnitudes of the “easy–hard” word-span difference scores and digit-span scores were not significant. This finding indicates that the observed memory span advantage for lists of “easy” words over lists of “hard” words using nonrepeated sampling is not related to participants’ STM capacity, as measured by traditional digit-span, in any consistent fashion. Second, the “easy” word-span advantage did not increase with increases in list length. This finding means that the advantage is relatively constant and does not vary with the overall cognitive load placed on STM capacity by increases in list length.

Consider what might he happening when a participant encodes each token of a spoken word under nonrepeating presentation conditions. During the process of word recognition, the entire lexical neighbourhood of the word receives some initial activation (cf., Luce & Pisoni, 1998). “Hard” word lists, having denser neighbourhoods, will therefore create more lexical competition than “easy” word lists, resulting in a lower span score. The error analyses lend further support to the proposal that the locus of lexical competition effects in immediate memory span tasks may be found in LTM activation mechanisms rather than STM processes. When lexical competition had no effect on span performance under repeated sampling, errors were mainly order errors. There were also no differences between “easy” and “hard” words in alt error categories. When memory span performance was influenced by lexical competition under the nonrepeated conditions, many more item errors were observed. More important, there was still no difference between “easy” and “hard” words for the order errors, but there were more “hard” word item errors than “easy” word item errors. The present results can be explained by assuming that order and positional information is handled primary by STM rehearsal mechanisms such as the phonological loop, but item-specific information is also influenced by properties of LTM, such as the statistical distribution of words and phonological similarity of individual items in the lexicon.

In the case of repeated sampling of a small set of words, however, the repetition of the words serves to strengthen their activations on every trial and, with enough trials during an experiment, effectively makes them a closed response set (cf., Sommers et al., 1997). The strength of the words’ activations could possibly diminish lexical competition from LTM. As a consequence, the lexical neighbourhoods of the stimulus items would have no effect on the maintenance of the words’ activations. Any extraneous interference under the repeated sampling procedure would come from PI effects from previous lists in the test session but not the stimulus words themselves.

Are there any alternative explanations for the lexical effects we have observed in these experiments? Although we have argued that using a nonrepeated sampling procedure would minimize the effects of PI, it is possible that the rate of PI build-up may be different for the “easy” and “hard” words. Because of more competition from denser lexical neighbourhoods, the PI build-up for “hard” words may be much faster than for “easy” words. Unfortunately, the current experimental design does not permit us to examine this prediction. At the beginning of the experiment when PI should be lowest, participants all start with a short list length. List length continues to increase, at the same time that PI may start to increase, throughout the experiment. As a result, we cannot dissociate the effects of PI from the effects of cognitive load due to increases in list length. Maintaining a constant list length across all trials in the experiment would allow an examination of the time-course of any lexical competition or PI effects (cf., Nairne et al, 1997). The next experiment addressed this issue directly.

EXPERIMENT 2

Experiment 2 was designed to determine whether the PI build-up for “hard” words occurs at a faster rate than that for “easy” words. By keeping list length constant across all trials to control for cognitive load, we would expect to find a larger difference in recall between “easy” and “hard” lists as the number of trials increases, if it is indeed the case that PI interacts with the degree of lexical competition. During the initial trials, PI would be lowest, and hence the “easy–hard” recall difference should be smaller; and then as PI increases, the recall difference should increase accordingly. Also, if the PI build-up rate is different for “easy” and “hard” word lists, this should be reflected in different slopes for the respective recall functions across trials. On the other hand, if PI does not interact with lexical competition, then we would expect the magnitude of the “easy–hard” differences to remain relatively stable across trials. Differences in immediate recall can then be primarily attributed to the lexical neighbourhood properties of the words.

Method

Participants

A total of 44 undergraduates from the Psychology Department at Indiana University participated in the study for course credit. All were native English speakers with no speech or hearing disorder at the time of testing.

Materials

The same materials and apparatus as those in Experiment 1 was used.

Design and procedure

The study followed the same general design and procedure as those in Experiment 1 except for the following: A list length of six items was used throughout all trials, with a total of 11 trials.

Data scoring

Because this experiment did not use a memory span procedure with incremental list lengths, the scoring methods of the previous experiments were no longer appropriate. The number of words recalled in the correct serial position at each trial was used as the dependent measure in alt the analyses reported below.

Results and discussion

Digit-span scores

There were no significant differences in the digit-span scores for the participants assigned to the two different sampling conditions, all ts(41) < 1.4, indicating that both groups were similar in STM capacity.

Lexical neighbourhood and item repetition

We collapsed the data across all trials to determine whether the fixed list length manipulation affected the general findings obtained in the first experiment. A two-way ANOVA showed that the Word Type × Sampling interaction was once again significant, F(1, 42) = 8.92, MSE = 22.88, p < .01. Analyses of simple effects again identified the recall advantage of “easy” over “hard” words under the nonrepeated sampling condition, F(l, 42)= 12.69, MSE = 22.88, p < .01, and the advantage of repeated sampling over nonrepeated sampling for “hard” words, F(1, 42) = 11.45, MSE = 67.93, p < .01, as the causes of the interaction. There was also no significant correlation between participants’ digit-span scores and the magnitude of the “easy–hard” difference scores under the nonrepeated condition, all rs(22) x .3. Thus, the basic pattern of results from the first experiment was replicated again in this experiment—lexical competition effects emerged only under nonrepeated sampling, and the magnitude of the “easy–hard” difference was not related to STM capacity when measured using digit-spans.

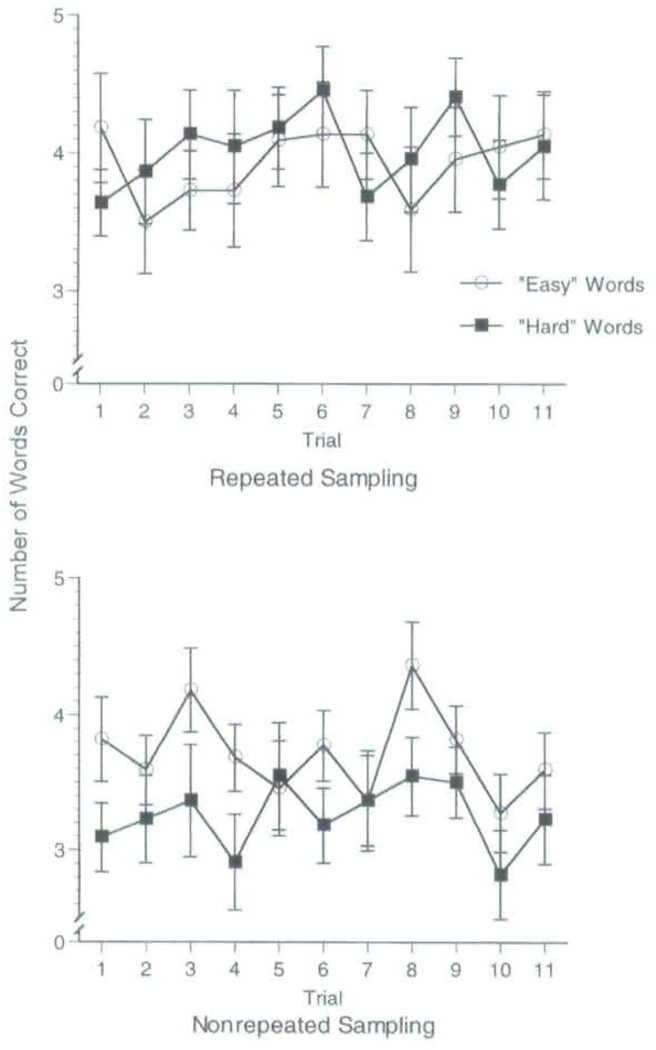

Analyses across trials

The average number of words recalled across the 11 trials in the two sampling conditions is shown in Figure 4. A three-way mixed design ANOVA using word type, sampling, and trial as the fixed factors showed that the main effect of trial and all of the interactions involving the trial factor were not significant, all Fs < 1. These results indicate that the Word Type × Sampling interaction observed above was not influenced by any potential PI effects that should have increased across trials, under both the repeated and nonrepeated conditions. It can be seen clearly from the nonrepeated sampling condition shown in the lower panel in Figure 4 that the magnitude of the difference between recall of “easy” and recall of “hard” words remained relatively constant across trials. There was also no indication that there was any difference in the slopes of the recall function for “easy” and “hard” word lists, as they are both relatively flat.

Figure 4.

Recall performance across trials and sampling conditions in Experiment 2.

These results suggest that any PI effects operating on recall performance are similar for both types of word lists, and the observed performance differences are driven primarily by lexical competition. Rehearsal processes in STM, such as those associated with the phonological loop, are likely to be effective in maintaining serial order information and minimizing the effects of PL However, rehearsal is unlikely to prevent LTM attributes of words, such as neighbourhood properties, from influencing recall. This was clearly evident under nonrepeated sampling conditions because the words are unique on each list and have to he newly activated and retrieved from LTM on each trial. Under repeated sampling conditions, LTM does not have to be accessed, and therefore the neighbourhood effects disappear completely.

Error analyses

We classified the errors using the same categories as before. Because a fixed list length was being used, it was now possible to add the category of protrusion errors (see Henson, 1998). This error is defined as responding in the current trial with an item that was in the same serial position in the immediately preceding list. Protrusion errors can be considered a type of positional error that involves interference from a prior list. We would expect protrusion errors to be more common when words are repeated across trials but not under nonrepeated sampling conditions.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of errors collapsed across all trials for the two sampling conditions. The general pattern found for the errors in Experiment 1 was replicated in the present experiment. As in the earlier error analyses, a three-way ANOVA revealed a significant Word Type × Sampling × Error Type interaction, F(4, 168) = 3.21, MSE = 8.68, p < .05. Inspection of the simple effects again showed that there were no differences between “easy” and “hard” words for all the error categories in the repeated sampling condition. There were more neighbourhood errors for “hard” words than for “easy” words in the nonrepeated condition, F(1, 21) = 8.62, MSE = 5.33, p < .01, but unlike Experiment 1, no difference was found for intrusion errors, F < 1. No differences were found between “easy” and “hard” words for order and protrusion errors, all Fs < 1. As before, it is also clear from the data shown in Figure 5 that there were generally more item-type errors than positional-type errors in the nonrepeated sampling condition, whereas the reverse pattern was true for the repeated sampling condition. These error patterns again suggest that positional information in STM was not influenced by lexical competition from LTM, whereas lexical factors were closely associated with the maintenance of item information in STM.

Figure 5.

Average number of errors (+SE) for Experiment 2 in the repeated and nonrepeated sampling conditions.

Item analyses of Experiments 1 and 2

One potential problem with the words used in the repeated sampling conditions is that the number of vowels used was not balanced. There were five different vowels among the eight “easy” words but only three different vowels among the eight “hard” words. Previous studies have demonstrated that vowels tend to be better remembered than consonants (e.g., Darwin & Baddeley, 1974; Surprenant & Neath, 1996). It is possible that having more words that share the same vowel in the “hard” word set might cause greater confusion for these words in STM than the words that comprised the “easy” word set. Therefore, differences between “easy” and “hard” words could stem from both LTM neighbourhood properties and the fact that the number of vowels was not balanced in the two sets. This is not problematic in the nonrepeated sampling conditions because many words were sampled, but is a potential problem for the eight-word sets in the repeated sampling conditions. It should be pointed out that one would expect recall for the “hard” words to be lower than recall for “easy” words in the repeated sampling conditions if indeed the greater number of “hard” words sharing the same vowels increased the degree of confusion in the STM traces of the “hard” words. However, no significant differences in recall were found between the “easy” and “hard” words in the repeated sampling conditions in both Experiments 1 and 2. Nevertheless, it is possible that while overall recall rates were the same for “easy” and “hard” words in the repeated sampling conditions, different rates of recall for specific words could have been influenced by whether those words shared the same vowel with other words in the set.

The mean recall probability of each word used in the repeated sampling conditions was computed to determine whether there was any trend suggesting that recall rates were associated with the number of shared vowels. The computation of recall probabilities for each word in Experiment 2 was straightforward because the list length of six was constant for all trials. A similar item analysis could not be adequately performed in Experiment 1 because several list lengths were used with only two trials per list length. A reasonable comparison with Experiment 2 could be made by examining the trend for the performance at a list length of six in Experiment 1. However, the variances of the recall probabilities between the two experiments are not homogeneous because of the large difference in the number of trials used to derive the recall probabilities between Experiments 1 and 2 (2 vs. 11). Therefore, no appropriate statistical analysis could be performed across experiments.

The recall probabilities are presented in Table 1. If recall probability is affected by the number of words sharing the same vowel, one would predict that the “hard” words sane, cake, lace, and race would have significantly lower recall rates than the words bun, sun, wit, and sit. Likewise, one might predict that the “easy” words heap and death would have significantly better recall rates than the words fig, pig, gang, sang, hop, and top. For both experiments, one-way within-subjects ANOVAs performed separately for the “easy” and “hard” word sets revealed no significant differences among the recall probabilities of each of the “easy” and “hard” words, all Fs < 1. This result demonstrates that there is no compelling evidence to suggest that recall rates are associated with the number of words sharing the same vowel.

TABLE 1.

Recall proportions for words in the repeated sampling conditions

| Experiment 1a | Experiment 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Words | M | SD | M | SD | |

| “Easy” | fig | .61 | .38 | .65 | .20 |

| pig | .57 | .43 | .61 | .19 | |

| gang | .63 | .38 | .64 | .19 | |

| sang | .73 | .35 | .71 | .17 | |

| hop | .60 | .43 | .65 | .16 | |

| top | .66 | .42 | .63 | .21 | |

| heap | .65 | .43 | .67 | .20 | |

| death | .66 | .40 | .68 | .20 | |

| “Hard” | bun | .61 | .42 | .70 | .18 |

| sun | .65 | .37 | .66 | .17 | |

| sane | .61 | .40 | .59 | .27 | |

| cake | .46 | .45 | .70 | .16 | |

| lace | .63 | .41 | .71 | .18 | |

| race | .59 | .41 | .67 | .17 | |

| wit | .65 | .41 | .74 | .17 | |

| sit | .66 | .40 | .67 | .20 | |

List length 6.

One difference between the present study and previous studies showing differential recall rates for vowels and consonants (e.g., Darwin & Baddeley, 1974; Surprenant & Neath, 1996) is that the previous studies used mostly nonsense syllables or a mixture of word and nonwords, whereas the present study used only real words. It is entirely possible that when nonword stimuli are used, sublexical properties such as phonotactics and consonant and vowel features are more salient and are recruited in redintegration and recall (for a detailed discussion of sublexical and lexical influences, see Gathercole et al., 1999; Vitevitch & Luce, 1998). However, when only words are used as stimuli, lexical features such as phonological word neighbourhoods become more salient.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The results of the present investigation demonstrate that lexical competition and the neighbourhood properties of spoken words affect immediate memory span beyond initial word recognition, particularly when the use of limited coding strategies and PI was explicitly minimized under nonrepeated sampling conditions. Several findings suggest that these lexical neighbourhood effects were dependent on LTM mechanisms that operate independently of STM processes. First, the correlations between the magnitude of the “easy–hard” word-span lexical difference scores and traditional digit-span scores were small and not significant. This finding indicates that the observed memory span advantage for lists of “easy” words over lists of “hard” words, using nonrepeated sampling, was not related to individual differences in participants’ STM capacity for immediately recalling digits in any systematic fashion. Second, the “easy” word-span advantage did not increase with increases in list length. This finding means that the advantage was relatively constant and did not vary with the overall processing load placed on STM capacity by increases in list length. Finally, the general pattern of recall errors was consistent with the immediate memory span results—item-type errors such as intrusions and neighbourhood errors showed lexical effects only under the nonrepeated sampling conditions. In contrast, positional-type errors such as order and protrusion errors did not exhibit lexical effects under either sampling condition. Since postulated STM mechanisms such as the phonological loop are associated with the maintenance of serial order information in working memory, the lack of an “easy—hard” lexical difference in positional-type errors suggests that lexical competition does not influence the operation of rehearsal mechanisms involved in simply maintaining serial order information in working memory.

The present findings support previous results reported in the recent literature that have demonstrated a strong LTM contribution to memory span performance (e.g., Gathercole et al, 1999; Hulme, Roodenrys, Brown, & Mercer, 1995; Hulme et al., 1995, 1997; Walker & Hulme, 1999) and have suggested independent LTM effects on STM serial recall tasks (e.g., Bourassa & Besner, 1994; Hulme et al., 1991). Our results extend these findings in several new directions, however, by showing that the magnitude of the lexical neighbourhood effects is not systematically related to individual differences in STM capacity for spoken digits, which may be interpreted as additional evidence for a separate influence of LTM organization on immediate memory span. The error patterns observed here also generalize earlier findings by demonstrating converging evidence for the proposal that different processing mechanisms are primarily responsible for long-term lexical effects and short-term rehearsal processes.

Baddeley (1998) has suggested that STM mechanisms such as the phonological loop are dedicated to maintaining STM traces by way of articulatory and rehearsal processes in immediate span tasks. Other researchers have also suggested that the attributes of words that are stored in LTM, such as frequency, similarity, phonotactics, and lexicality, aid in reconstructive processes when the traces in the phonological loop are too degraded for direct recall from STM (Gathercole et al., 1999; Hulme et al., 1991; Schweickert, 1993; Schweickert et al., 1999).

Schweickert’s (1993) multinomial processing tree model predicts that direct recall from the STM trace is initially attempted. If the trace is still relatively intact, there will be a very high probability of recall. However, if the trace has been degraded in some way to the point where direct recall is not possible, then redintegrative processes are assumed to come into play. Redintegration is essentially a “clean-up” process, which attempts to reconstruct the decayed STM trace on the basis of noisy or incomplete information. The process will be facilitated if the item has a representation in LTM that can be used to aid reconstruction. Hence, real words have a substantial advantage over nonwords because of the availability of permanent LTM representations for real words in the lexicon (Hulme et al., 1991).

Our findings can be accommodated within Schweickert’s (1993) theoretical framework. There is less lexical competition among similar sounding traces for lexically “easy” words, which leads to less confusion among the candidates for reconstruction, and thus redintegration of the decayed traces of “easy” words is easier. In contrast, lexically “hard” words have many more similar sounding competitors, and thus the reconstructive process will be more difficult. This results in a higher probability of successful recovery with less acoustic–phonetic confusability in the phonological neighbourhoods of “easy” words than those in of “hard” words.

We should emphasize that the differences in immediate memory span reported here for “easy” and “hard” words are not simply another example of the phonological similarity effect that is observed when memory span is greater for phonologically dissimilar words than for phonologically similar words (cf., Baddeley, 1998). Lexical competition and the lexical neighbourhood properties of spoken words do not exist in the phonological traces or phonetic details of the individual stimulus items per se; rather, they exist only in the long-term structure and relational organization of words in the mental lexicon and the pattern of activations within a lexical neighbourhood for a particular word (see Luce & Pisoni, 1998). This means that the individual words are not only activating their own phonological representations in LTM, but they are also activating other phonetically similar words, which are related to their phonological attributes. Thus, lexical activation in LTM subsequently affects the retrieval and reconstructive processes in STM that are involved in the immediate memory span task for spoken words. Also, in the case of repeated sampling of a small set of words, the repetition of the same words over and over again may serve to strengthen their activations on each trial and effectively make these items a closed response set (cf., Sommers et al., 1997). Thus, the strength of the words’ activations could possibly reduce the interference of other words from the same lexical neighbourhood. As a consequence, lexical neighbourhoods should have no effect on the maintenance of the words’ activations under repeated sampling conditions, as we found in these experiments.

An explanation of the present findings in terms of reconstructive processes during retrieval suggests that memory processing may be analogous to speech production processes, as several researchers have claimed (e.g., Knott, Patterson, & Hodges, 1997; Schweickert, 1993). Redintegration processes in memory may be similar to the reconstructive processes involved in repairing speech errors (Schweickert, 1993). However, it is also necessary to consider speech perception processes as well. The effects of lexical neighbourhoods on immediate memory span observed in our experiments are similar to the lexical competition effects observed in other word recognition studies. Models of word recognition such as NAM (Luce & Pisoni, 1998), TRACE (McClelland & Elman, 1986), and PARSYN (Luce, Goldinger, Auer, & Vitevitch, 2000) account for these neighbourhood effects by postulating some form of competition among LTM traces of the words, so that words with many similar overlapping features would be harder to recognize. Because spoken word recognition involves accessing the words from the mental lexicon, the locus of neighbourhood effects is related to the nature of the statistical distribution of features of words that are stored in the entire lexicon in LTM. Similarly, retrieving words from lexical memory during speech production or STM tasks also involves access to the mental lexicon and will thus be influenced by the nature of its organization. It seems reasonable to assume that a common lexical access mechanism is used in both reconstruction of memory traces and recognition of words—redintegrative processes may he functionally similar to the discrimination and selection processes embodied in current models of word recognition that involve competition among LTM representations.

The proposal that speech processing and STM share common underlying mechanisms is not new and has been fundamental in the explanations for the word length and articulatory suppression effects (Baddeley et al., 1975; Salamé & Baddeley, 1982). One computational model that incorporates both speech processing and STM mechanisms is Gupta and MacWhinney’s (1997) model of immediate .serial recall. Their model demonstrated that the maintenance of information in STM is mediated by both a phonological representation system and a speech planning apparatus. These two underlying mechanisms account for both immediate serial recall performance and vocabulary acquisition. While vocabulary acquisition is beyond the scope of this paper, the present findings showing that the organization of long-term phonological knowledge influences memory span for spoken words is consistent with Gupta and MacWhinney’s simulations that demonstrate the significant role played by the long-term phonological representation system in determining immediate memory span size.

We should also acknowledge the possibility that lexical neighbourhood effects observed here may also arise during the output phase of the immediate serial recall task. It is possible that words with few competitors result in faster verbal output and are therefore less susceptible to decay (cf., Cowan et al., 1998), thus producing the “easy” word advantage that we found. Because our experimental procedures required written responses as output, it is difficult to investigate this question with the present data. Future research on speech production should explore this issue more thoroughly using spoken responses.

In summary, the present findings demonstrate that lexical competition influences performance in immediate memory span tasks. The locus of these effects appears to be in the LTM mechanisms employed during lexical access. The present results reveal important differences in performance depending on whether repeated or nonrepeated sampling is used in immediate memory span tasks. Although the present study does not seek to argue for a specific memory architecture, one implication for current memory models is that the specialized “phonological loop”-type modules will need to include long-term phonological organization and structure into their mechanisms and processes. It may turn out to be more parsimonious to consider STM and LTM processes in a more tightly integrated fashion or even as one unitary memory system, as some memory theorists have suggested. For example, STM might be considered as the currently active portion of LTM (e.g., Anderson &; Bower, 1973; Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1971; Engle, 1996). It should be acknowledged that the present results are also compatible with the view that there are multiple memory systems, for which there is a growing body of evidence from patients with selective impairment to phonological and lexical aspects of verbal working memory (e.g., Baddeley, Papagno,& Vallar, 1988; Martin & Romani, 1994), and from other neuropsychological and brain imaging studies that show different patterns of activation associated with the different components of working memory (see Gabrieli, 1998; and Smith & Jonides, 1997, for recent reviews). From the present results, the temporary maintenance of words in a specific serial order or when the words are drawn repeatedly from a small closed set might rely heavily on a STM system for verbal material. On the other hand, a separate system that stores long-term lexical knowledge may be recruited in circumstances where STM traces are incomplete, such as when a large pool of words arc used without replacement.

Whatever architecture one adopts, the present results on immediate memory span for spoken words demonstrate that the processes used in accessing and recognizing spoken words may also be recruited in immediate serial recall of spoken words under nonrepeated presentation conditions. The present findings are consistent with the general principles of speech perception and production—that spoken words are recognized “relationally” in the context of other phonetically similar words stored in long-term lexical memory (Luce & Pisoni, 1998). Thus, the process of recognizing, memorizing, and recalling spoken words from working memory appears to make use of a common processing mechanism that exploits “competition” among a set of activated patterns in LTM that differ in lexical density and acoustic–phonetic similarity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH-NIDCD Research Grant DC00011 to Indiana University and a staff training grant awarded to the first author from the National University of Singapore. We would like to thank Luis Hernandez and Michael Vitevitch for help in programming the experiment and Jaime Brumfield, Patrick Kelley, and Jeff Karpicke for assistance in data collection and storing.

Contributor Information

Winston D. Goh, National University of Singapore, Singapore

David B. Pisoni, Indiana University, Bloomington, USA

REFERENCES

- Anderson JR, Bower GH. Human associative memory. Washington, DC: Winston; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson RC, Shiffrin RM. The control of short-term memory. Scientific American. 1971;225:82–90. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0871-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD. Short-term memory for word sequences as a function of acoustic, semantic and formal similarity. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1966;18:363–365. doi: 10.1080/14640746608400055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD. Working memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD. Human memory: Theory and practice. Rev. ed. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Hitch G. Working memory. In: Bower GH, editor. Recent advances, in the psychology of learning and motivation. Vol. VII. New York: Academic Press; 1974. pp. 47–89. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Lewis V, Vallar G. Exploring the articulatory loop. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1984;36A:233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Papagno C, Vallar G. When long-term learning depends on short-term storage. Journal of Memory and Language. 1988;27:586–595. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, Thomson N, Buchanan M. Word length and the structure of short-term memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1975;14:575–589. [Google Scholar]

- Bavelier D, Potter MC. Visual and phonological codes in repetition blindness. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1992;18:134–147. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.18.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa DC, Besner D. Beyond the articulatory loop: A semantic contribution to serial order recall of subspan lists. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1994;1:122–125. doi: 10.3758/BF03200768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges AM, Jones DM. Word dose in the disruption of serial recall by irrelevant speech: Phonological confusions or changing state? Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1996;49A:919–939. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Rochon E, Waters GS. Articulatory and phonological determinants of word length effects in span tasks. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1992;45A:177–192. doi: 10.1080/14640749208401323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Waters GS. Articulatory length and phonological similarity in span tasks: A reply to Baddeley and Andrade. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1994;47A:1055–1062. doi: 10.1080/14640749408401108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluff MS, Luce PA. Similarity neighbourhoods of spoken two-syllable words: Retroactive effects on multiple activation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1990;16:551–563. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.16.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart V. Effects of phonological similarity and concurrent irrelevant articulation on short-term-memory recall of repeated and novel word lists. Memory and Cognition. 1993;21:539–545. doi: 10.3758/bf03197185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart M, Davelaar E, Jonasson JT, Besner D. Access to the internal lexicon. In: Dornic S, editor. Attention and performance VI. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 535–555. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad R. Acoustic confusions in immediate memory. British Journal of Psychology. 1964;55:75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N, Wood NL, Nugent LD, Treisman M. There are two word-length effects in verbal short-term memory: Opposed effects of duration and complexity. Psychological Science. 1997;8:290–295. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N, Wood NL, Wood PK, Keller TA, Nugent LD, Keller CV. Two separate verbal processing rates contributing to short-term memory span. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1998;127:141–160. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.127.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin CJ, Baddeley AD. Acoustic memory and the perception of speech. Cognitive Psychology. 1974;6:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Murdock BB., Jr The role of auditory features in memory span for words. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory. 1980;6:319–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan JP. Articulation testing methods. Laryngoscope. 1948;58:955–991. doi: 10.1288/00005537-194809000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle RW. Working memory and retrieval: An inhibition-resource approach. In: Richardson JTE, editor. Working memory and human cognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 89–119. [Google Scholar]

- Engle RW, Nations JK, Cantor J. Is “working memory capacity” just another name for word knowledge? Journal of Educational Psychology. 1990;82:799–804. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrieli JD. Cognitive neuroscience of human memory. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:87–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Frankish CR, Pickering SJ, Peaker S. Phonotactic influences on short-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1999;25:84–95. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.25.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldinger SD, Luce PA, Pisoni DB. Priming lexical neighbours of spoken words: Effects of competition and inhibition. Journal of Memory and Language. 1989;28:501–518. doi: 10.1016/0749-596x(89)90009-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldinger SD, Luce PA, Pisoni DB, Marcario JK. Form-based priming in spoken word recognition: The roles of competition and bias. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1992;18:1211–1238. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.18.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldinger SD, Pisoni DB, Logan JS. On the nature of talker variability effects on recall of spoken word lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1991;17:152–162. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.17.1.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P, MacWhinney B. Vocabulary acquisition and verbal short-term memory: Computational and neural bases. Brain and Language. 1997;59:267–333. doi: 10.1006/brln.1997.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasher L, Zacks RT. Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In: Bower GH, editor. The psychology of learning and motivation. Vol. 22. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 193–225. [Google Scholar]

- Henson RNA. Short-term memory for serial order; The Start–End Model. Cognitive Psychology. 1998;36:73–137. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1998.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson RNA. Positional information in short–term memory: Relative or absolute? Memory & Cognition. 1999;27:915–927. doi: 10.3758/bf03198544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House A, Williams C, Hecker M, Kryter K. Articulation testing methods: Consonantal differentiation with a closed-response set. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1965;37:158–166. doi: 10.1121/1.1909295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme C, Maughan S, Brown GDA. Memory for familiar and unfamiliar words: Evidence for a long-term memory contribution to short-term memory span. Journal of Memory and Language. 1991;30:685–701. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme C, Roodenrys S, Brown G, Mercer R. The role of long-term memory mechanisms in memory span. British Journal of Psychology. 1995;86:527–536. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme C, Roodenrys S, Schweickert R, Brown GDA, Martin S, Stuart G. Word-frequency effects on short-term memory tasks: Evidence for a redintegration process in immediate serial recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 1997;23:1217–1232. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.23.5.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott R, Patterson K, Hodges JR. Lexical and semantic binding effects in short-term memory: Evidence from semantic dementia. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 1997;14:1165–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Kucera H, Francis WN. Computational analysis of present-day American English. Providence, RI: Brown University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Landauer TK, Streeter LA. Structural differences between common and rare words: Failure of equivalence assumptions for theories of word recognition. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1973;12:119–131. [Google Scholar]

- La Pointe LB, Engle RW. Simple and complex word spans as measures of working memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1990;16:1118–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Lovatt P, Avons SE, Masterson J. The word-length effect and disyllabic words. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2000;53A:1–22. doi: 10.1080/713755877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce PA, Goldinger SD, Auer ET, Vitevitch MS. Phonetic priming, neighbourhood activation and PARSYN. Perception & Psychophysics. 2000;62:615–625. doi: 10.3758/bf03212113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce PA, Pisoni DB. Recognizing spoken words: The neighbourhood activation model. Ear & Hearing. 1998;19:1–36. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199802000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce PA, Pisoni DB, Goldinger SD. Similarity neighbourhoods for spoken words. In: Altmann GTM, editor. Cognitive models of speech processing: Psycholinguistic and computational perspectives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1990. pp. 142–147. [Google Scholar]