Abstract

Objective

Although there has been a great deal of recent empirical work and new theoretical interest in audiovisual speech perception in both normal-hearing and hearing-impaired adults, relatively little is known about the development of these abilities and skills in deaf children with cochlear implants. This study examined how prelingually deafened children combine visual information available in the talker’s face with auditory speech cues provided by their cochlear implants to enhance spoken language comprehension.

Design

Twenty-seven hearing-impaired children who use cochlear implants identified spoken sentences presented under auditory-alone and audiovisual conditions. Five additional measures of spoken word recognition performance were used to assess auditory-alone speech perception skills. A measure of speech intelligibility was also obtained to assess the speech production abilities of these children.

Results

A measure of audiovisual gain, “Ra,” was computed using sentence recognition scores in auditory-alone and audiovisual conditions. Another measure of audiovisual gain, “Rv,” was computed using scores in visual-alone and audiovisual conditions. The results indicated that children who were better at recognizing isolated spoken words through listening alone were also better at combining the complementary sensory information about speech articulation available under audiovisual stimulation. In addition, we found that children who received more benefit from audiovisual presentation also produced more intelligible speech, suggesting a close link between speech perception and production and a common underlying linguistic basis for audiovisual enhancement effects. Finally, an examination of the distribution of children enrolled in Oral Communication (OC) and Total Communication (TC) indicated that OC children tended to score higher on measures of audiovisual gain, spoken word recognition, and speech intelligibility.

Conclusions

The relationships observed between auditory-alone speech perception, audiovisual benefit, and speech intelligibility indicate that these abilities are not based on independent language skills, but instead reflect a common source of linguistic knowledge, used in both perception and production, that is based on the dynamic, articulatory motions of the vocal tract. The effects of communication mode demonstrate the important contribution of early sensory experience to perceptual development, specifically, language acquisition and the use of phonological processing skills. Intervention and treatment programs that aim to increase receptive and productive spoken language skills, therefore, may wish to emphasize the inherent cross-correlations that exist between auditory and visual sources of information in speech perception.

With the continued broadening of candidacy criteria and the numerous technological advances in cochlear implant signal processing, more children than ever before have the potential to develop spoken language processing skills using cochlear implants. However, there are enormous individual differences in pediatric cochlear implant outcomes (Fryauf-Bertschy, Tyler, Kelsay, & Gantz, 1992; Fryauf-Bertschy, Tyler, Kelsay, Gantz, & Woodworth, 1997; Miyamoto et al., 1989; Osberger et al., 1991; Staller, Beiter, Brimacombe, Mecklenberg, & Arndt, 1991; Tyler, Fryauf-Bertschy, Kelsay, Gantz, Woodworth, & Parkinson, 1997; Tyler, Fryauf-Bertschy, Gantz, Kelsay, & Woodworth, 1997; Tyler, Parkinson, Fryauf-Bertschy, Lowder, Parkinson, Gantz, & Kelsay, 1997; Zimmerman-Phillips, Osberger, & Robbins, 1997). Some children can learn to communicate extremely well using the auditory/oral modality and acquire age-appropriate language skills, whereas other children may display only minimal spoken word recognition skills and/or display very delayed language abilities (Bollard, Chute, Popp, & Parisier, 1999; Pisoni, Svirsky, Kirk, & Miyamoto, Reference Note 3; Robbins, Bollard, & Green, 1999; Robbins, Svirsky, & Kirk, 1997; Svirsky, Sloan, Caldwell, & Miyamoto, Reference Note 4; Tomblin, Spencer, Flock, Tyler, & Gantz, 1999; Tyler, Tomblin, Spencer, Kelsay, & Fryauf-Bertschy, in press). At the present time, these differences cannot be predicted very well before implantation but emerge only after electrical stimulation has commenced (Pisoni, 2000).

It has been demonstrated that demographic and audiological factors play a role in success with a cochlear implant. For example, research suggests that children with superior spoken word recognition scores after implantation are typically those who are implanted at a very young age (Waltzman & Cohen, 1988) or those who had more residual hearing before implantation (Zwolan, Zimmerman-Phillips, Ashbaugh, Hieer, Kileny, & Telain, 1997). In addition, the type of therapeutic intervention also appears to affect postimplant performance. That is, children who utilize auditory-oral and are educated in that modality have significantly higher spoken word recognition abilities, on average, than children who utilize Total Communication (TC), which is the combined use of signed and spoken English (Osberger & Fisher, Reference Note 2). However, although demographic and audiological factors play an important role in pediatric cochlear implant outcomes, these independent variables alone are not sufficient to account for the large individual differences (Fryauf-Bertschy et al., 1992, 1997). Rather, variability in performance with a cochlear implant may be related to perceptual, cognitive and linguistic processes involved in the acquisition and processing of spoken language by the central nervous system (Pisoni, Cleary, Geers, & Tobey, 2000; Pisoni & Geers, 2000). One important perceptual process that may provide some new insights into the underlying basis of the large individual differences is multimodal sensory integration. It is well known that normal-hearing and hearing-impaired adults can make use of both auditory and visual information to enhance speech perception, especially under poor listening conditions (Massaro & Cohen, 1995; Rosenblum, Johnson, & Saldaña, 1996; Sumby & Pollack, 1954; Summerfield, 1987). Early investigations into audiovisual speech perception by children showed that similar gains in speech recognition are obtained by children with hearing impairments, as well as those with normal hearing (Erber, 1971, 1972a, 1972b, 1974, 1975).

Relatively little, however, is known about the ability to use both auditory and visual sources of information about speech in normal-hearing children or prelingually deaf children with cochlear implants. Preliminary work in this area showed that children with cochlear implants do receive a gain due to combined audiovisual inputs relative to audition alone or vision alone (Tyler, Opie, Fryauf-Bertschy, & Gantz, 1992). In another study, Tyler, Fryauf-Bertschy, Kelsay, Gantz, Tyler, Woodworth, and Parkinson (1997) tested children with cochlear implants on a 10-alternative forced-choice test of audiovisual feature detection called the Audiovisual Speech Perception Feature Test for Children. Their results demonstrated that children with cochlear implants display evidence of audiovisual enhancement; that is, audiovisual scores were higher than audio-alone scores. As might be expected, audio-alone and audiovisual perception scores also increased over time with implant use. Interestingly, Tyler et al.’s data also revealed that the implanted children showed improvement in lipreading abilities over time. That is, as the children accumulated experience with the implant (between 2 and 4 yr postimplantation), their skills in perceiving speech via vision alone improved as well. This finding suggests that a cochlear implant, aside from providing access to the auditory sensory modality, also allows for the construction of more general, more fully specified phonetic representations of the articulatory form of speech, a theme we will be returning to throughout this paper.

Audiovisual integration reflects the perceiver’s ability to use different sources of sensory information to perceive and recover the underlying articulations of the talker’s vocal tract (Fowler, 1989; Fowler & Dekle, 1991; Gaver, 1993; Massaro & Cohen, 1995; Remez, Fellowes, Pisoni, Goh, & Rubin, 1999; Rosenblum, 1994; Rosenblum & Saldaña, 1996; Vatikiotis-Bateson, Munhall, Kasahara, Garcia, & Yehia, Reference Note 5). The seminal work in this area was first conducted by Sumby and Pollack (1954) who found that simply allowing listeners to hear and see words spoken in noise was equivalent to an increase in the signal to noise ratio of about 15 dB (Summerfield, 1987). Because this gain in performance was so large, the combination of multiple sources of information about speech has the potential to be extremely useful for listeners with hearing impairments (Berger, 1972). The study of multimodal integration may also provide new knowledge about the underlying sensory and perceptual basis of the large individual differences among deaf children with cochlear implants, and may have several implications for the development of new treatment and intervention strategies with this population of children.

Some analysis of the sensory integrative abilities of listeners with hearing impairments has been carried out (Massaro & Cohen, 1999, also contains a meta-analysis and modeling of some of these studies; see Tyler, Tye-Murray, & Lansing, 1988, for an excellent review article). For example, Erber (1972a) measured the speech perception abilities of children with normal hearing, children with severely impaired hearing, and children with profoundly impaired hearing under auditory-alone, visual-alone, and auditory-visual presentation conditions. The stimuli used in his experiment were consonants in an /aCa/ environment. Like the participants in Sumby and Pollack’s (1954) study, Erber found that the children with hearing impairment were able to make use of the complementary information provided by the visual modality in the auditory-visual condition, increasing their speech perception performance relative to the scores obtained in the auditory-alone condition.

In another study using adult listeners, consonant confusions made by two multiple-channel cochlear implant users were analyzed under auditory-alone, visual-alone, and auditory-visual presentation conditions (Dowell, Martin, Tong, Clark, Seligman, & Patrick, 1982). The authors found that speech perception scores were enhanced when patients were able to combine auditory information in the form of electrical stimulation through the cochlear implant and visual information. Taken together, these and other studies demonstrate a consistent finding—audiovisual presentation facilitates speech perception performance relative to performance under auditory-alone or visual-alone presentation conditions (Massaro & Cohen, 1995; Summerfield, 1987).

Substantial individual variation exists, however, in the extent to which a particular subject’s scores are improved by the additional sensory information provided by visual input. In a recent study, Grant, Walden, and Seitz (1998) compared the observed audiovisual facilitation with scores predicted by several models of sensory integration. These models predicted optimal audiovisual performance based on observed recognition scores for consonant identification in auditory-alone and visual-alone conditions. Grant et al. (1998) found that the models either over- or under-predicted the observed audiovisual data, indicating that not all individuals integrate auditory and visual information optimally. This was especially true when speech perception performance was measured using higher-order linguistic units such as words and sentences. Although Grant et al.’s predictions based on segmental accuracy could account for a large amount of the variance observed (e.g., 50% of sentence-level integration variability), the authors concluded that much more work must be carried out before an adequate model of word- and sentence-level audiovisual integration can be developed.

There is also an extensive literature on the factors that influence the efficacy of “speechreading,” or speech perception under visual-alone conditions (see Berger, 1972, for an excellent summary of preliminary work in this area). For example, lighting, angle of viewing, and distance from a talker obviously affect the quality of the optical information provided in a visual-alone environment and the ability of the speechreader to use that information (Auer & Bernstein, 1997; Jackson, 1988). Similarly, the distinctive and idiosyncratic way in which a particular talker articulates speech also plays a large role in affecting his or her speech intelligibility when observed in visual-alone environments (Lesner, 1988; Lesner & Kricos, 1981). Finally, the idiosyncratic speechreading abilities of the observer receiving the message also contribute to visual-only speech intelligibility. Factors as diverse as visual acuity, training, hearing loss, attention and even motivation play important roles in speechreading (Berger, 1972).

Because so little is known about the audiovisual skills of pediatric users of cochlear implants, the present study was carried out to directly examine the relationship between auditory-alone measures of spoken language processing and the use of audiovisual information by hearing-impaired children who use cochlear implants.

Methods

Participants

The participants examined in this study were 27 children with prelingual deafness who had used a multichannel cochlear implant for 2 yr. The average age of onset of deafness was 0.51 yr. The average age at the time of implantation was 4.52 yr. Their mean unaided pure tone average threshold was 112 dB HL. Table 1 provides a summary of the demographic data for each participant in this study. All children were profoundly deaf at the time of implantation, and derived little benefit from any other amplification before implantation (this was a prerequisite for the surgical procedure at the time these children were implanted). Because the children lived some distance from the Indiana University medical center, ongoing aural rehabilitation was provided through a local source. At the time of testing, all the children were enrolled in programs that provided training and therapy. Eighteen of the 27 participating children had implants that use older processing strategies.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants in the present study. For all participants, the length of device use was 2 yr

| Number | Communication Mode | Age at Profound Loss (yr) | Unaided PTA (dB HL) | Age CI Fit (yr) | Processor | Strategy | # Active Elec.s | Age (yr) | PPVT Age Equivalent (yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TC | Congenital | 117 | 3.50 | MSP | MPEAK | 18.00 | 5.50 | 3.50 |

| 2 | OC | Congenital | 112 | 5.50 | MSP | MPEAK | 22.00 | 7.70 | 2.83 |

| 3 | TC | 1.00 | 120 | 4.90 | MSP | MPEAK | 22.00 | 6.80 | 3.83 |

| 4 | OC | 0.40 | 112 | 3.80 | SPECTRA | SPEAK | 18.00 | 5.90 | 3.75 |

| 5 | OC | Congenital | 102 | 5.80 | MSP | MPEAK | 13.00 | 7.80 | 4.08 |

| 6 | OC | Congenital | 117 | 4.10 | MSP | MPEAK | 19.00 | 6.10 | 2.42 |

| 7 | OC | Congenital | 103 | 5.20 | MSP | MPEAK | 22.00 | 6.90 | 2.92 |

| 8 | TC | Congenital | 118 | 4.90 | WSP | F0F1F2 | 13.00 | 6.90 | 5.5 |

| 9 | OC | 3.00 | 113 | 5.20 | MSP | MPEAK | 19.00 | 7.30 | 2.67 |

| 10 | TC | Congenital | 110 | 3.70 | SPECTRA | SPEAK | 18.00 | 5.90 | 4.92 |

| 11 | OC | 1.90 | 118 | 5.40 | MSP | F0F1F2 | 8.00 | 8.00 | 4.75 |

| 12 | OC | Congenital | 108 | 4.40 | SPECTRA | SPEAK | 18.00 | 6.30 | 3.83 |

| 13 | TC | Congenital | 108 | 4.60 | MSP | MPEAK | 18.00 | 6.60 | 5.5 |

| 14 | OC | Congenital | 112 | 5.30 | SPECTRA | SPEAK | 19.00 | 7.20 | 3.92 |

| 15 | TC | Congenital | 105 | 5.00 | MSP | MPEAK | 19.00 | 7.00 | 3.83 |

| 16 | TC | Congenital | 118 | 5.30 | SPECTRA | SPEAK | 20.00 | 7.30 | 5.75 |

| 17 | TC | Congenital | 100 | 5.20 | SPECTRA | SPEAK | 22.00 | 7.40 | 3.17 |

| 18 | OC | Congenital | 112 | 4.30 | MSP | MPEAK | 22.00 | 6.30 | 2.25 |

| 19 | TC | 1.80 | 117 | 4.30 | WSP | F0F1F2 | 15.00 | 6.30 | 5.5 |

| 20 | TC | 1.80 | 117 | 5.30 | MSP | MPEAK | 16.00 | 7.10 | 5.75 |

| 21 | OC | Congenital | 98 | 4.30 | SPECTRA | SPEAK | 20.00 | 6.30 | 3.08 |

| 22 | TC | 1.40 | 113 | 2.20 | SPECTRA | SPEAK | 18.00 | 4.20 | 2.92 |

| 23 | TC | Congenital | 113 | 2.90 | MSP | F0F1F2 | 21.00 | 4.90 | 5.33 |

| 24 | TC | 1.20 | 115 | 4.60 | MSP | MPEAK | 19.00 | 6.60 | 5.75 |

| 25 | TC | Congenital | 118 | 4.20 | SPECTRA | SPEAK | 20.00 | 6.30 | 3.42 |

| 26 | OC | 1.30 | 113 | 3.10 | MSP | MPEAK | 19.00 | 5.30 | 3.50 |

| 27 | TC | Congenital | 118 | 5.00 | MSP | MPEAK | 19.00 | 7.10 | 7.50 |

PTA = pure-tone average; CI = cochlear implant; PPVT = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test; TC = Total Communication; OC = Oral Communication.

Procedures and Measures

Scores from the Common Phrases Test (Osberger et al., 1991) were obtained from these children under three presentation conditions, auditory-alone (A), visual-alone (V), and audiovisual (AV). The test was administered live-voice. The Common Phrases Test measures the ability to understand phrases used in everyday situations, such as “It is cold outside.” Performance in each condition was scored by the percentage of phrases correctly repeated, in their entirety, by the child. There were 10 phrases in each presentation condition. The words in the phrases were not balanced for lexical variables. There was no language criterion for administering the test.

The scores in the auditory-alone and audiovisual conditions were combined to obtain the measure Ra, the relative gain in speech perception due to the addition of visual information about articulation (Sumby & Pollack, 1954). Ra was computed using the following formula:

| (1) |

where AV and A represent the accuracy scores obtained in the audiovisual and auditory-alone conditions, respectively. From this formula, one can see that Ra measures the gain in accuracy in the AV condition relative to the accuracy in the A condition, normalized relative to the amount by which speech intelligibility could have possibly improved above auditory-alone scores. An analogous measure, Rv, was also computed using scores in the visual-alone condition as the baseline:

| (2) |

This alternative measure of gain may be more appropriate for these children, because it is reasonable to assume that they may rely more on visual input than on auditory input for speech perception (Grant & Seitz, 1998). Thus, the gain over visual-alone performance due to “additional” auditory information is reported here as Rv.

Three additional tests designed to measure spoken word recognition performance under auditory-alone conditions were administered live-voice to participants by an audiologist or speech-language pathologist. The Lexical Neighborhood Test (LNT) and Multisyllabic Lexical Neighborhood Test (MLNT) (Kirk, 1999; Kirk, Eisenberg, Martinez, & Hay-McCutcheon, 1999; Kirk, Pisoni, & Osberger, 1995) are both open-set tests of word recognition for children that assess the effects of word frequency and lexical similarity on spoken word recognition in children. Using the lexical factors of frequency and similarity, it is possible to classify the items on the LNT and MLNT tests into “Easy” and “Hard.” Frequency here refers to the frequency of occurrence of a word in English (Kucera & Francis, 1967). Easy words are high-frequency words that reside in low-frequency, sparse phonological neighborhoods (i.e., there are few phonologically similar words with which can they be confused). Hard words are low-frequency words that reside in high-frequency, dense phonological neighborhoods (i.e., there are many phonologically similar words with which they can be confused). Differences in performance between easy and hard words on these tests will be maintained throughout the rest of this report because these scores provide important diagnostic information about how the process of lexical competition operates during spoken word recognition (see Luce & Pisoni, 1998).

In addition to the LNT and MLNT tests, the Phonetically Balanced Kindergarten word lists (PB-K) (Haskins, Reference Note 1) were administered via live voice to assess speech perception under auditory-alone presentation conditions. This test also provides an open-set measure of word recognition performance using items that are balanced for phonetic content. The PB-K is a widely used clinical measure of speech perception skills in children who have cochlear implants (Kirk, Diefendorf, Pisoni, & Robbins, 1997; Meyer & Pisoni, 1999). These three measures of spoken word recognition performance were chosen because they are among the most commonly used to determine cochlear implant candidacy and to monitor postimplant outcome benefits in children. The scores on these tests (LNT, MLNT, and PB-K) will be referred to collectively as the “auditory measures.”

A measure of receptive language was used to assess differences in the ability of these children to use language in general. This measure was obtained using the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT), a standardized test that provides a measure of receptive language development based on word knowledge (Dunn & Dunn, 1997). Test items were presented using the child’s preferred mode of communication, either speech or sign, depending on whether the child was immersed in an OC-only or TC educational environment.

Finally, in addition to these receptive measures of performance, a test of speech production was administered to each child to obtain a measure of speech intelligibility (Miyamoto, Svirsky, Kirk, Robbins, Todd, & Riley, 1997). Each child imitated 10 Beginner’s Intelligibility Test (BIT) sentences (Osberger, Robbins, Todd, & Riley, 1994). The child’s utterances were recorded and played back later for transcription by three naïve adult listeners who are unfamiliar with deaf speech. Speech intelligibility scores were measured by calculating the average number of words correct for the three listeners.

Results

Raw Scores on Common Phrases and Audiovisual Gain

Table 2 shows the individual scores obtained by each child in the auditory-alone, visual-alone, and audiovisual conditions obtained from the Common Phrases Test, along with the corresponding R values. Because these data were collected along with numerous other assessment tests as part of a longitudinal project, some of the children were judged too tired or unable to participate in the visual-alone condition of the Common Phrases Test due to time constraints. For these children (N = 7), visual-alone scores are not reported.

TABLE 2.

Performance of participants on the three subtests of the Common Phrases test, along with the measure of visual enhancement, Ra, and auditory enhancement, Rv, calculated from those measures

| Participant | Presentation Format of Common Phrases Test

|

Best Difference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auditory-Alone | Visual-Alone | Audiovisual | Unimodal Sum | Ra Score (Auditory) | Rv Score (Visual) | ||

| 1 | 0 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 0.30 | 0.13 | 10 |

| 2 | 20 | 50 | 50 | 70 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 |

| 4 | 80 | 50 | 100 | 100* | 1.00 | 1.00 | 20 |

| 5 | 80 | 80 | 100 | 100* | 1.00 | 1.00 | 20 |

| 6 | 0 | 30 | 40 | 30 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 10 |

| 7 | 0 | 40 | 20 | 40 | 0.20 | −0.33 | −20 |

| 8 | 10 | — | 80 | — | 0.78 | — | — |

| 9 | 60 | — | 70 | — | 0.25 | — | — |

| 10 | 80 | 20 | 90 | 100 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 10 |

| 11 | 0 | 80 | 90 | 80 | 0.90 | 0.50 | 10 |

| 12 | 70 | 50 | 90 | 100* | 0.67 | 0.80 | 20 |

| 13 | 0 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 0.10 | −0.13 | −10 |

| 14 | 90 | 50 | 100 | 100* | 1.00 | 1.00 | 10 |

| 15 | 10 | 0 | 30 | 10 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 20 |

| 16 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0 |

| 17 | 30 | 40 | 60 | 70 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 20 |

| 18 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0 |

| 19 | 40 | — | 60 | — | 0.33 | — | — |

| 20 | 0 | 50 | 60 | 50 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 10 |

| 21 | 70 | 60 | 80 | 100* | 0.33 | 0.50 | 10 |

| 22 | 40 | 0 | 30 | 40 | −0.17 | 0.30 | −10 |

| 23 | 0 | — | 40 | — | 0.40 | — | — |

| 24 | 10 | — | 80 | — | 0.78 | — | — |

| 25 | 20 | — | 30 | — | 0.13 | — | — |

| 26 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 20 |

| 27 | 0 | — | 70 | — | 0.70 | — | — |

| Mean | 27.78 | 32.50 | 54.44 | 54.00 | .42 | .36 | 7.5 |

| Lower bounda | 15.30 | 20.18 | 42.16 | 36.46 | .32 | .17 | n/a |

| Upper bounda | 40.26 | 44.82 | 66.72 | 71.53 | .58 | .54 | n/a |

A “—” indicates that the participant was not tested under that condition. The “Best Difference” column indicates the difference between the score in the audiovisual condition and the score for the better of either the auditory-alone or visual-alone conditions. For ease of comparison, the better single modality score for each child is printed in bold notation.

Bounds associated with 95% confidence interval.

Sum of unimodal scores exceeds maximum of 100.

The range of scores in all presentation conditions varied considerably. In the auditory-alone condition, scores varied from 0% to 90% correct. Similarly, in the visual-alone condition, scores ranged from 0% to 80%. Audiovisual scores varied across the entire possible range.

It is important to note here that there was no significant difference between performance in the two “unimodal” presentation conditions: auditory-alone and visual-alone, t(19) = −0.72, n.s. Thus, on average, there was no overall tendency for these children to rely more on one input modality than the other. However, on an individual basis, it is apparent that some children used one input modality more than the other. Table 2 shows that of the 20 children tested in both unimodal conditions, eight had higher visual-alone scores, nine had higher auditory-alone scores, and three had equal scores in each condition.

There were, however, significant correlations among the three presentation conditions on the Common Phrases Test. Auditory-alone and visual-alone performance showed a significant relationship, r(18) = +0.40, p < 0.05. In addition, performance in the audiovisual condition was strongly related to both the auditory-alone condition, r(25) = +0.67, p < 0.01, and the visual-alone condition, r(18) = +0.78, p < 0.01. These correlations suggest a common underlying source of variance—that the same set of skills may be used on the Common Phrases Test, regardless of presentation modality. However, these relations may not simply be due to a more global language proficiency or to an ability to use the contextual framework of the Common Phrases task better. Correlations between the Common Phrases for each of the three presentation formats and PPVT age equivalence scores were not significant (auditory-alone: r(25) = +0.20, n.s.; visual-alone: r(18) = −0.12, n.s.; audiovisual: r(25) = +0.20, n.s.).

We also analyzed the relationship between Ra and PPVT age equivalence. Despite the fact that vocabulary knowledge was not related to the Common Phrases scores in each of the presentation modalities, there was a relationship between Ra and PPVT age equivalence, r(25) = +0.32, p < 0.05. This indicates that the ability to benefit from audiovisual input is related to global language abilities, independent of a child’s perception scores.

Inspection of the Ra and Rv scores in Table 2 shows that on the Common Phrases Test, children with cochlear implants exhibit a wide range of ability to combine multisensory input. The final column in Table 2 lists the difference between each child’s audiovisual score and the score obtained in the better of the two unimodal conditions.

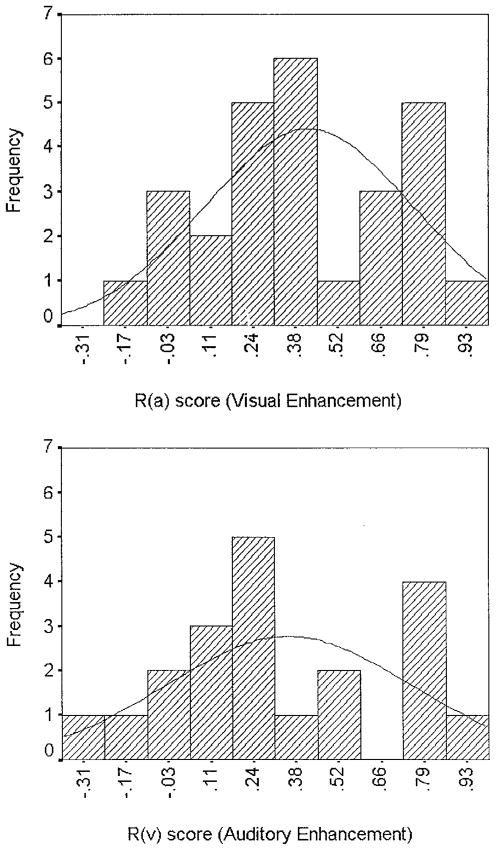

Such raw score gains are not meaningful, however, unless put in the context of possible gains, as is done with Ra. The top panel of Figure 1a shows the frequency distribution of Ra scores for children in the sample under study. The normal curve superimposed over the data is based on the mean (M = 0.42) and standard deviation (SD = 0.34) of the sample. As shown in the figure, our sample was normally distributed with respect to the ability to derive benefit from audiovisual input, with a slight positive skew. Given access to the visual information about the form of the utterances in the audiovisual condition, some children (N = 3) increased their performance as much as possible from their auditory-alone baselines (indicated by R scores of 1.0). In contrast, other children received little or no benefit at all from the “additional” visual information provided in the AV condition (indicated by Ra scores of 0.0). One child’s performance in the AV condition was actually worse than in the auditory-alone condition, resulting in a negative Ra score. However, for most of the children (N = 23), the audiovisual score was significantly higher than the auditory-alone score, t(26) = 5.48, p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Top panel shows the frequency distribution of Ra scores (enhancement relative to auditory-alone performance) for the sample. Bottom panel shows the frequency distribution of Rv scores (enhancement relative to visual-alone performance). Higher R scores denote larger gains in accuracy in the audiovisual condition relative to accuracy in the relevant unimodal condition.

Because these children have been without normal hearing for most of their lives, one might argue that in the AV condition the children were simply relying on the visual information alone to perform the task, and were not actually combining the information from both sensory modalities. However, for many of the children who had visual-alone scores, the observed AV scores were greater than the visual-alone scores (N = 16 out of 20 total). This finding is supported by a paired t-test on scores in the audiovisual and visual-alone conditions, t(19) = 4.08, p < 0.001. Interestingly, for two of the children, the visual-alone score was higher than the AV score, suggesting the possibility that for these children, additional auditory information may produce inhibition and reduce performance. Although the present study does not address issues related to inhibition and competition among input signals, it may be interesting in the future to study the characteristics of children who show this atypical pattern of audiovisual performance under these testing conditions.

As discussed above, almost half of the children tested had higher visual-alone scores than auditory-alone scores. Thus, gains in the audiovisual condition might be better described as gains observed over visual-alone rather than auditory-alone performance (i.e., Rv rather than Ra). However, there was a very strong positive correlation between Ra and Rv, r(18) = +0.76, p < 0.01, a finding that is very likely due to the close relationship between audio-alone and visual-alone performance reported above. For the sake of completeness, however, we present a histogram showing the distribution of Rv scores in the bottom panel of Figure 1. Again, the scores appear to be normally distributed, although they are slightly more positively skewed than the distribution of Ra scores.

Table 2 also displays a column in which the sum of the scores in the audio-alone and visual-alone presentation conditions is listed. This score is reported only for those children tested in both the auditory-alone and visual-alone conditions of the Common Phrases Test. The scores shown in this column represent the expected performance of the child in the audiovisual condition if the mechanism for combining multisensory cues is purely additive. In other words, if the process of audiovisual integration simply combined information from the two sensory modalities, we would expect that performance would be the simple sum of performance in the audio-alone and visual-alone conditions. This is admittedly a simple model of audiovisual integration. However, it can serve as a convenient benchmark for comparing theories that predict super-additive performance in audiovisual presentation conditions. Comparison of scores in this column with the observed audiovisual scores reveals that for most children, audiovisual performance did not differ from the simple sum of performance in the audio-alone and visual-alone conditions. A paired t-test on the observed and predicted scores did not show a significant difference between the two, t(19) = 0.72, n.s. For most children, audiovisual performance did not exceed that predicted by the simple sum of performance in the unimodal conditions. Thus, there does not appear to be a super-additive effect of audiovisual integration during the perception of highly familiar test sentences, such as those on the Common Phrases Test.

Correlations among Measures of Auditory Speech Perception

It is also important to assess the correlations among our various measures of auditory-alone speech perception, to assess their validity as measures of a general ability to recognize spoken words in auditory-alone environments. Table 3 shows the various measures and their intercorrelation. Inspection of the table reveals that all the measures were significantly related to one another. It is worth noting here that the auditory-alone subtest of the Common Phrases (the first column in the table) was strongly related to all the other auditory-alone measures of speech perception.

TABLE 3.

Intercorrelations among auditory-alone measures of spoken word recognition. Ns for each cell are reported in parentheses below the correlations

| Auditory-Alone Spoken Word Recognition Test

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP auditory | LNT Easy | LNT Hard | MLNT Easy | MLNT Hard | |

| CP Auditory | |||||

| LNT Easy | 0.90** (17) | ||||

| LNT Hard | 0.72** (13) | 0.75** (13) | |||

| MLNT Easy | 0.83** (15) | 0.85** (15) | 0.65* (11) | ||

| MLNT Hard | 0.86** (11) | 0.80** (11) | 0.57* (10) | 0.75** (11) | |

| PB-K | 0.81** (24) | 0.83** (15) | 0.76** (12) | 0.70** (14) | 0.77** (10) |

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05.

Correlations of Audiovisual Gain with Spoken Word Recognition Scores

In this study, we were also interested in whether measures of spoken word recognition were related to AV benefit. To address this question, the median score for each auditory measure was calculated, and participants were categorized as either being above the median score for the auditory measure (“high” group) or below the median score (“low” group). Using this method, it was entirely possible for a particular child to be classified in the low group for the split based on one measure and in the high group for the split based on another measure. However, when this happened for a particular child, it only affected classification based on one or two tests. Because not all of the children contributed to each of the auditory-alone word recognition measures, the total Ns for the various splits differed slightly.

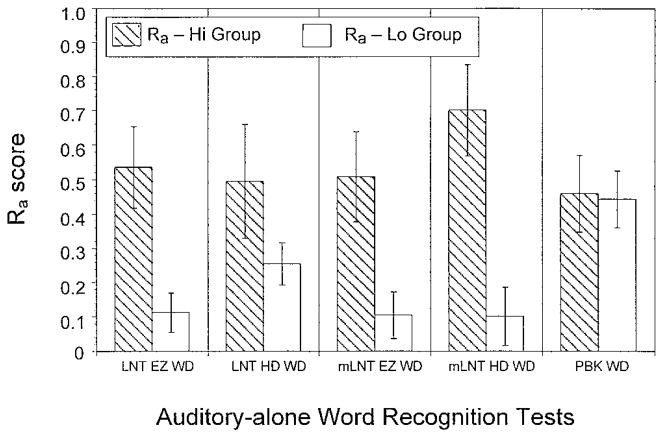

Figure 2 shows the Ra scores for the high and low groups for each median split. Each panel shows the results based on a different median split. The filled bar in each panel shows the average Ra score for children in the high group, the open bar shows the average Ra score for children in the low group. Overall, there was a consistent pattern— children who had higher auditory-alone word recognition scores displayed higher audiovisual gain scores.

Figure 2.

Audiovisual benefit (Ra) for the high-performing (above the median) and low-performing (below the median) groups of the median splits for five measures of auditory-alone word recognition. Error bars are standard errors.

One-tailed t-tests for independent samples were conducted to assess differences in the Ra scores for children in the low versus high groups for each of the auditory measures. Significant differences were found in this analysis when the children were split by median scores on the LNT Easy test, t(15) = 3.36, p = 0.002, the MLNT Easy test, t(13) = 2.62, p = 0.01, and the MLNT Hard test, t(9) = 3.927, p = 0.002. However, the analyses failed to show a significant difference for median splits based on the LNT Hard test, t(11) = 1.275, n.s., and the PB-K test, t(22) = 0.116, n.s. As shown by the low scores obtained on these two tests, they were the two most difficult measures for the children. The results from this first analysis demonstrate that children who derive more benefit from the multisensory input of audiovisual presentation also tend to be good performers on auditory-alone measures of spoken word recognition.

To quantify the relationship between audiovisual benefit and measures of spoken word recognition, a series of simple bivariate correlations were calculated between the Ra scores and each of the five auditory-alone word recognition measures. Table 4 shows the correlations between each of these measures and Ra. The correlations reveal the same pattern of results as the t-tests using median splits. Strong correlations were obtained between the Ra score and performance on the LNT Easy, MLNT Easy, and MLNT Hard tests. The correlations between Ra and performance on the LNT Hard and PB-K tests were low and nonsignificant.

TABLE 4.

Correlations between Ra scores and measures of spoken word recognition

| Auditory-Alone Spoken Word Recognition Test

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNT Easy | LNT Hard | MLNT Easy | MLNT Hard | PB-K | |

| Ra score | 0.78** | 0.28 | 0.57* | 0.68* | 0.28 |

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05.

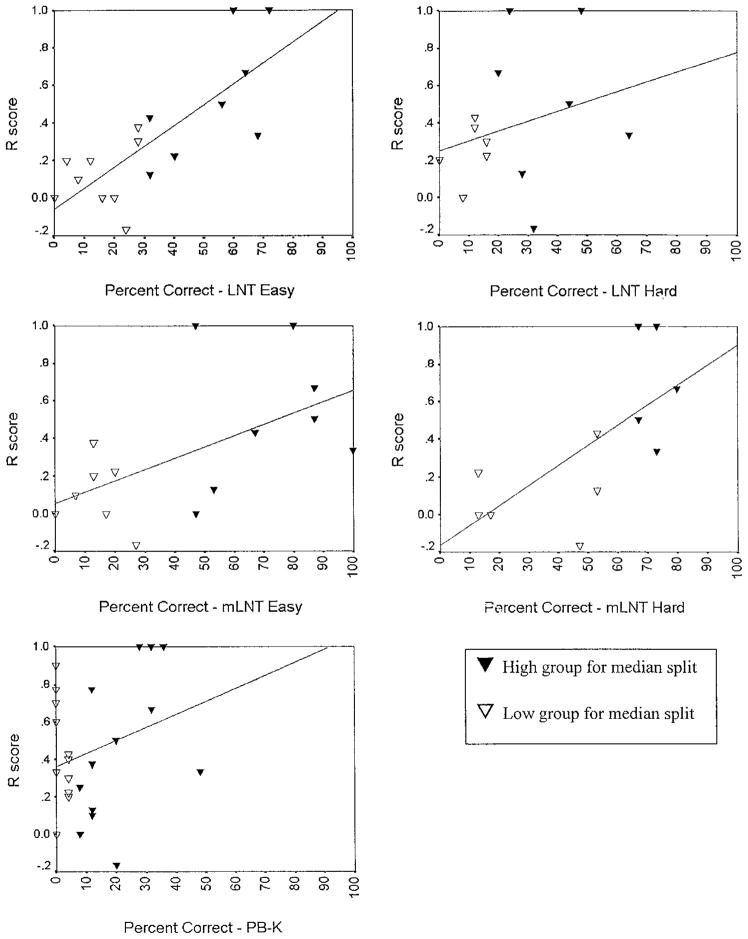

Figure 3 shows scatterplots for each of the five word recognition measures. In each figure, the ordinate represents the Ra score and the abscissa represents the score on one of the spoken word recognition tests. Each point represents an individual child. Open triangles are for children who scored below the median, filled triangles are for children who scored above the median. These scatterplots also show the regression line for the two variables. Not surprisingly, the figures show a strong relationship between the Ra score and the LNT Easy test and both word lists of the MLNT test.

Figure 3.

Scatterplots showing the relationships between Ra score (audiovisual benefit) and the auditory-alone measures of spoken word recognition

The restricted range of the LNT Hard test may be responsible for the lack of a significant relationship with Ra. Table 5 shows the skew values associated with the distribution of scores for each of the auditory measures. Examination of the table indicates that the distribution of scores for the LNT Hard and PB-K tests are more positively skewed than the distributions for the other measures used in the present study. These measures confirm that the LNT Hard and PB-K tests were extremely difficult for most of the children included in our study. Considering that the two tests with the highest positive skews failed to show significant correlations with R, it is very likely that these findings are the result of floor effects.

TABLE 5.

Measures of skewness for the five auditory-alone measures of spoken word recognition. Positive values denote rightward skews, and negative values denote leftward skews

| Auditory-Alone Speech Perception Test

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNT Easy | LNT Hard | MLNT Easy | MLNT Hard | PB-K | |

| Skewness | 0.377 | 0.890 | 0.322 | −0.655 | 1.167 |

Inspection of the scatterplots shows that the lack of a significant relationship between Ra and the LNT Hard score may also be due in part to an unusually low outlier (the filled triangle with a negative Ra score and an LNT Hard score of around 33). This participant was below the median score for all the other tests, except the PB-K, which also failed to show a significant relationship with R. Again, the range of scores in the LNT Hard and PB-K tests was substantially reduced relative to variation observed on the other tests, raising the possibility that this child would fall above, rather than below, the median.

We also carried out a set of similar correlations between Rv (i.e., gain over visual-alone performance due to added auditory information) and the auditory-alone word recognition measures. Table 6 shows that the relationships were all very strong, including those for the LNT Hard and PB-K tests. It is not surprising that the audiovisual gain over visual-alone performance was related to performance on the auditory-alone measures. If a child is receiving a substantial benefit from his or her cochlear implant under auditory-alone conditions, under audiovisual conditions he or she is able to use “extra” auditory information to improve his or her speech perception performance under audiovisual conditions.

TABLE 6.

Correlations between Rv scores and measures of spoken word recognition

| Auditory-Alone Spoken Word Recognition Test

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNT Easy | LNT Hard | MLNT Easy | MLNT Hard | PB-K | |

| Rv score | 0.90** | 0.63* | 0.77** | 0.81** | 0.69** |

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05.

Measures of Speech Production and Speech Intelligibility

In addition to these word recognition measures, 23 of the 27 participants also provided speech intelligibility scores. On average, naïve adult listeners could correctly identify 17.13% of the words produced by these children on the elicited sentence production task. The speech intelligibility scores ranged from 2% to 45%. Although this may seem like very poor performance, it is important to emphasize here that these judgments were made by naïve adult listeners. Trained clinicians, such as those who administered our auditory-alone tests, have much more experience with the speech of deaf children and have little difficulty understanding their responses.

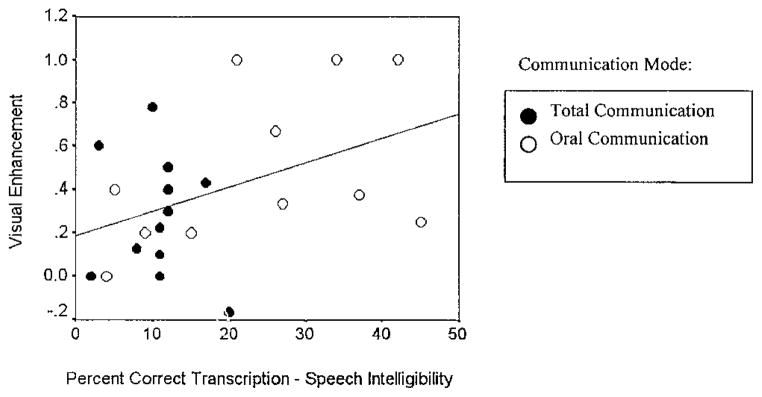

To assess the relations between visual enhancement (Ra) and speech intelligibility, we computed a simple correlation between these two measures. The analysis revealed a significant correlation between the speech intelligibility scores and Ra scores, r(21) = +0.42, p < 0.05. We also observed a significant relationship between speech intelligibility and Rv scores, r(17) = +0.54, p < 0.01. Both correlations indicate that children who receive larger gains from combined audiovisual information also have more intelligible speech. This pattern suggests a common link between speech perception and speech production skills in these children.

Effects of Communication Mode

We also examined the effects of communication mode on R. Eleven of the children who provided speech intelligibility scores for this analysis were enrolled in education settings using OC methods, and 12 of the children were enrolled in settings using TC methods. The children enrolled in oral programs are taught to use speaking and listening skills (including lipreading) for communication. Children in this study who were enrolled in a TC approach used a combination of spoken and manually coded English for communication.

Figure 4 shows a scatterplot displaying the distribution of the speech intelligibility and audiovisual enhancement (Ra) scores for each of these two groups of children. The diagonal line through the scatterplot is the regression line predicting Ra from speech intelligibility. In this figure, the data are split by communication mode.

Figure 4.

Scatterplots showing the relationship between visual enhancement and speech intelligibility split by communication mode. Oral Communication children are represented by open triangles; Total Communication children are represented by filled triangles.

Examination of Figure 4 shows that children with higher Ra scores also had higher speech intelligibility scores. In addition, it appears that most of the high scorers on the speech intelligibility measure (and consequently the Ra scale) used OC (open circles). In fact, 72.7% of the OC children in this figure (N = 8) were above the median speech intelligibility score of 12%. In contrast, only 41.7% of the TC children (N = 5) achieved speech intelligibility scores higher than the median. A t-test for independent samples confirmed the finding that speech intelligibility scores for OC children were significantly higher than the scores for TC children, t(21) = 2.99, p = 0.04.

We also calculated the correlation between Ra and speech intelligibility for each of the communication mode groups independently. The results showed a marginally significant correlation for children in the OC group, r(9) = +0.463, p = 0.08. However, there was no relationship between the two measures for children in the TC group, r(10) = −0.19, n.s. Because the Ns are so small in each group, it is hard to draw firm conclusions about these correlations. However, the results of this analysis are suggestive and indicate that audiovisual gain is a better predictor of speech intelligibility for the OC children than for the TC children.

Discussion

The present study examined the performance of a group of prelingually deafened children with cochlear implants in combining perceptual information about spoken language from two sensory modalities—audition and vision. The results of a series of analyses demonstrate that the skills in deriving benefit from audiovisual sensory input are not isolated or independent but are closely related to auditory-alone spoken word recognition and speech production abilities, both of which draw on a common set of underlying phonological processing abilities. We observed strong relationships in performance between R, a measure of audiovisual gain, and scores on the LNT Easy, MLNT Easy, and MLNT Hard tests. Children who derived more gain from combined sensory inputs were also better performers on auditory-alone measures of spoken word recognition. In addition, we found a positive correlation between both types of R score and speech intelligibility scores. Children who derived more AV benefit also produced more intelligible speech. Finally, our analyses showed that early sensory and linguistic experience, in the form of OC or TC education, is related to the intelligibility of speech and the ability to combine auditory and visual sources of information. These relations were stronger in OC children than in TC children. For OC children, there was a marginally significant relationship between the intelligibility of a child’s speech and his or her ability to derive benefit from combined sensory input, revealing the effects of early sensory experience on the ability to derive a benefit from combined perceptual sources of information about speech.

Audiovisual gain reflects the ability of perceivers to combine and use diverse information from disparate sensory modalities to recognize spoken words, syllables, and phonemes (Braida, 1991; Fowler & Dekle, 1991; Green & Gerdeman, 1995; Green & Kuhl, 1991; Kuhl & Meltzoff, 1984; Massaro & Cohen, 1995; Remez et al., 1999; Rosenblum & Saldaña, 1996; Summerfield, 1987; Vatikiotis-Bateson, Munhall, Hirayama, Lee, & Terzepoulos, 1997). Recent theoretical accounts of AV integration assume that sources of auditory and visual information about spoken language are combined by the perceptual system because both sensory modalities carry information relevant to specifying the dynamic behavior of a talker’s articulating vocal tract (Rosenblum & Saldaña, 1996). Visual cues specifying the movement and action of the lips, the tongue tip and the jaw provide complementary information that can be used to recover the underlying behavior of the vocal tract. Auditory access to the movement and action of more internal articulators, such as the tongue blade, the tongue body, and the velum provides additional information about the same articulatory events (Summerfield, 1987). It is precisely this time-varying articulatory behavior of the vocal tract that has been shown to be of primary importance in the perception of speech (Liberman & Mattingly, 1985; Remez, Rubin, Berns, Pardo, & Lang, 1994; Remez, Rubin, Pisoni, & Carrell, 1981) and it is precisely these same gestures that are represented in auditory and optical displays of speech.

Viewed with this framework, the sensory and perceptual information relevant for speech perception is said to be modality-neutral, because it can be carried by more than one sensory modality (Fowler, 1986; Gaver, 1993; Remez et al., 1999; Rosenblum & Saldaña, 1996). In addition, because the acoustic and optic specifications of speech information are produced by the same underlying articulatory gestures, they are lawfully related to each other and to the underlying sensory-motor events that produce them (Vatikiotis-Bateson, et al., Reference Note 5). Consequently, as long as information about the articulations of the vocal tract can be perceived, some degree of speech perception will be possible. Indeed, this fact is clearly demonstrated by the remarkable speechreading abilities of some people with hearing impairments (Rönnberg, Andersson, Samuelsson, Söderfeldt, Lyxell, & Risberg, 1999), and even by those with normal hearing (Bernstein, Demorest, & Tucker, 2000). Even more impressive is the finding that perceptual information obtained via the tactile modality, in the form of Tadoma, can be used and integrated across sensory modalities in speech perception (Fowler & Dekle, 1991), albeit with limited utility.

However, although the information necessary for speech perception may be modality-neutral, the internal representation of speech must be based on an individual’s experience with perceptual events and actions in the physical world. Clearly, awareness of the intermodal relationships between auditory and visual information must be contingent on experience with more than one sensory modality. Over time, processes of perceptual learning will come to exploit lawful co-occurrences in disparate modalities, until a rich and highly redundant multimodal representation of speech emerges (see Stein & Meredith, 1993, for more on the neural bases for multimodal sensory processing).

For prelingually deafened children who have received cochlear implants, however, these audiovisual learning processes only begin to develop after they receive their cochlear implant and begin to experience lawful relationships between vision and sound in their perceptual environment. The degree to which an individual can combine sensory information across sensory modalities may reflect the extent to which he or she has encoded and internalized the inherent commonalities between auditory and visual information about speech. The correlations we found in the gains from audiovisual information and performance on auditory-alone measures of speech perception in deaf children with cochlear implants suggest that the ability to combine multiple sources of information reflects generalized phonological processing skills that utilize phonetic information in any of its sensory forms. We also found that age equivalency, representing generalized language skill, was related to audiovisual gain, but not to accuracy itself, providing more evidence for our hypothesis that audiovisual gain reflects the internalization of linguistically relevant information in the speech signal. The conclusion is further supported by the finding that the productive speech capabilities of children with cochlear implants, as measured by speech intelligibility, are also strongly correlated with their ability to perceptually combine multiple sources of information about speech.

The generalized ability to utilize phonetic information during speech perception and production reflects the access to and use of audiovisual neural representations of the articulatory behavior of the vocal tract. At present, with our limited data, we can only speculate as to how these detailed representations develop, and why there are large individual differences among deaf children with cochlear implants in the ability to form them. However, the differences in performance between the TC and OC children suggest that early sensory experience plays a very important role and that focusing on the oral/aural communication of language may help to strengthen and solidify phonological and lexical representations in memory. Teaching hearing-impaired children about language in general does not appear to be sufficient for building the kinds of representations most advantageous for auditory speech perception. Rather, emphasis on the underlying linguistically relevant articulatory events that produce speech, by training orally and aurally, leads to improved ability in the perception and production of speech. The relationships observed in the present study between the benefits of audiovisual information, on the one hand, and performance measures of auditory-alone spoken word recognition and speech intelligibility, on the other hand, suggest that treatment and intervention programs should place greater emphasis on the inherent cross-correlations between auditory and visual information in speech. In this way, more robust phonological and lexical representations will be formed, ultimately leading to better performance on traditional outcome measures.

Although it is often quite common in clinics to work with deaf children using auditory and visual input, at the time assessments are carried out, auditory-alone measures are obtained and used as an index of learning and outcome. For the children who are good lip-readers and who display large audiovisual gains, these auditory-alone tests may not provide appropriate measures of their true underlying perceptual skills because an important source of sensory information has been arbitrarily removed for the purposes of measuring outcome. We strongly advocate the assessment of speech skills under a wide variety of conditions, including both auditory-alone and audiovisual measures of performance, so that a more complete picture of the development of spoken language processing skills in these children can be obtained to study change over time (Kirk, 2000).

General Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we observed a strong relationship between audiovisual gain scores in perception (as measured by both Rs) and speech intelligibility scores in production. Our findings suggest that one of the factors that differentiates good cochlear implant users from poor cochlear implant users is related to some common underlying set of phonological processing skills. These skills include perceptual, cognitive, and linguistic processes that are used in the initial encoding, storage, rehearsal and manipulation of the phonological and lexical representations of spoken words and the construction and implementation of sensory-motor programs for speech production and articulation. It is difficult for us to imagine other theoretical accounts of these audiovisual perception findings that are framed entirely in terms of peripheral sensory factors related to audibility without additional assumptions about the existence and use of phonological and lexical representations in tasks that are routinely used to measure outcome.

To account for the present set of findings, we believe it is necessary to assume the presence of some underlying linguistic structure and process that mediates between speech perception and speech production. Without a common underlying linguistic system—a grammar and specifically, a phonology—these separate perceptual and productive abilities would not be so closely coordinated and mutually interdependent. It is well known and clearly documented in the literature on language development that reciprocal links exist between speech perception, speech production and a whole range of language-related abilities and skills, including reading and writing (Ritchie & Bhatia, 1999). These links between the receptive and expressive aspects of language reflect the child’s developing linguistic knowledge of phonology, morphology and syntax and his or her attempts to use this knowledge productively in a range of language processing tasks.

It needs to be emphasized strongly here that the deaf children investigated in this study have been deprived of auditory experience for a substantial portion of their early lives before they received their cochlear implants. Some of these children are able to quickly learn to perceive and understand spoken language via electrical stimulation from their cochlear implants. Although they are delayed in their auditory and spoken language development relative to their normal-hearing peers, many of these children appear to be making large gains in language development (Svirsky, Robbins, Kirk, Pisoni, & Miyamoto, 2000). However, other children are not so fortunate and they seem to have much more difficulty making use of the degraded auditory information provided by their implant.

We believe that the study of individual differences in outcome and effectiveness of cochlear implants is an important research problem to investigate because of the direct and practical clinical implications this knowledge may yield. If we had a better understanding of the reasons for these individual differences in performance, we would be in a much stronger position to recommend specific changes in the child’s language learning environment that were based on some theoretical motivation and set of operating principles. At the present time, clinical decisions are made about intervention, treatment and therapy without a firm understanding of exactly why some children do well with their cochlear implant and why other children appear to do so much more poorly.

The findings from the present investigation suggest that larger gains in spoken word recognition and language comprehension performance might be obtained if deaf children with cochlear implants were encouraged to use all sources of sensory information about articulation. We uncovered several relationships in performance between audiovisual gain and auditory-alone measures of spoken word recognition in children with cochlear implants. In addition, we also found a strong relationship between the gain a child received from audiovisual presentation and measures of speech intelligibility. Both sets of findings suggest the importance of developing rich, multimodal long-term lexical representations of speech that encode linguistically significant differences. Because phonological and lexical representations are used in a variety of speech processing tasks, including both perception and production, performance on one task appears to be closely related to performance on other tasks, suggesting a common set of underlying linguistic processes and skills that reflect the child’s developing knowledge of spoken language.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH-NIDCD grants K23 DC00126, R01 DC00064, T32 DC00012, and R01 DC00423 to Indiana University and by Psi Iota Xi to Karen Iler Kirk. We also thank three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

References

- Auer ET, Jr, Bernstein LE. Speechreading and the structure of the lexicon: Computationally modeling the effects of reduced phonetic distinctiveness on lexical uniqueness. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1997;102:3704–3710. doi: 10.1121/1.420402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger KW. Speechreading: principles and methods. Baltimore: National Educational Press, Inc; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein LE, Demorest ME, Tucker PE. Speech perception without hearing. Perception and Psychophysics. 2000;62:233–252. doi: 10.3758/bf03205546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollard PM, Chute PM, Popp A, Parisier SC. Specific language growth in young children using the Clarion cochlear implant. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, & Laryngology. 1999;108(Suppl 117):119–123. doi: 10.1177/00034894991080s424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braida LD. Crossmodal integration in the identification of consonant segments. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1991;43A:647–677. doi: 10.1080/14640749108400991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell RC, Martin LFA, Tong YC, Clark GM, Seligman PM, Patrick JE. A 12-consonant confusion study on a multiple-channel cochlear implant patient. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research. 1982;25:509–516. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2504.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L, Dunn L. The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. 3. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Erber NM. Auditory and audiovisual reception of words in low-frequency noise by children with normal hearing and by children with impaired hearing. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1971;14:496–512. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1403.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber NP. Auditory, visual and auditory-visual recognition of consonants by children with normal and impaired hearing. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1972a;15:413–422. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1502.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber NP. Speech-envelope cues as an acoustic aid to lipreading for profoundly deaf children. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1972b;51:1224–1227. doi: 10.1121/1.1912964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber NP. Effects of angle, distance, and illumination on visual reception of speech by profoundly deaf children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1974;17:99–112. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1701.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber NP. Auditory-visual perception of speech. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1975;40:481–492. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4004.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CA. An event approach to the study of speech perception from a direct-realist perspective. Journal of Phonetics. 1986;14:3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CA. Real objects of speech perception: A commentary on Diehl and Kluender. Ecological Psychology. 1989;1:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CA, Dekle DJ. Listening with eye and hand: Cross-modal contributions to speech perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1991;17:816–828. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.17.3.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryauf-Bertschy H, Tyler RS, Kelsay DM, Gantz BJ. Performance over time of congenitally deaf and postlingually deafened children using a multichannel cochlear implant. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1992;35:913–920. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3504.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryauf-Bertschy H, Tyler RS, Kelsay DMR, Gantz BJ, Woodworth GG. Cochlear implant use by prelingually deafened children: The influences of age at implant and length of device use. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1997;40:183–199. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4001.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaver WW. What in the world do we hear? An ecological approach to auditory event perception. Ecological Psychology. 1993;5:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Grant KW, Seitz PF. Measures of auditory-visual integration in nonsense syllables and sentences. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1998;104:2438–2450. doi: 10.1121/1.423751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KW, Walden BE, Seitz PF. Auditory-visual speech recognition by hearing-impaired subjects: Consonant recognition, sentence recognition, and auditory-visual integration. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1998;103:2677–2690. doi: 10.1121/1.422788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KP, Gerdeman A. Cross-modal discrepancies in coarticulation and the integration of speech information: The McGurk effect with mismatched vowels. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1995;21:1409–1426. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.21.6.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KP, Kuhl PK. Integral processing of visual place and auditory voicing information during phonetic perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1991;17:278–288. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.17.1.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PL. The theoretical minimal unit for visual speech perception: Visemes and coarticulation. The Volta Review. 1988;90(5):99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk KI. Assessing speech perception in listeners with cochlear implants: The development of the lexical neighborhood tests. The Volta Review. 1999;100(2):63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk KI. Challenges in the clinical investigation of cochlear implant outcomes. In: Niparko JK, Kirk KI, Mellon NK, Robbins AM, Tucci DL, Wilson BS, editors. Cochlear Implants: Principles and Practices. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 225–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk KI, Diefendorf AO, Pisoni DB, Robbins AM. Assessing speech perception in children. In: Mendel LL, Danhauer JL, editors. Audiologic Evaluation and Management and Speech Perception Assessment. San Diego: Singular Publishing; 1997. pp. 101–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk KI, Eisenberg LS, Martinez AS, Hay-McCutcheon M. The Lexical Neighborhood Tests: Test-retest reliability and interlist equivalency. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 1999;10:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk KI, Pisoni DB, Osberger MJ. Lexical effects on spoken word recognition by pediatric cochlear implant users. Ear and Hearing. 1995;16:470–481. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199510000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera F, Francis W. Computational analysis of present day American English. Providence, RI: Brown University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl PK, Meltzoff AN. The intermodal representation of speech in infants. Infant Behavior and Development. 1984;7:361–381. [Google Scholar]

- Lesner SA. The talker. The Volta Review. 1988;90(5):89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lesner SA, Kricos PB. Visual vowel and diphthong perception across speakers. Journal of the Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology. 1981;14:252–258. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman A, Mattingly I. The motor theory revised. Cognition. 1985;21:1–36. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(85)90021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce PA, Pisoni DB. Recognizing spoken words: The neighborhood activation model. Ear and Hearing. 1998;19:1–36. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199802000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaro DW, Cohen MM. Perceiving talking faces. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Massaro DW, Cohen MM. Speech perception in perceivers with hearing loss: Synergy of multiple modalities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999;42:21–41. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4201.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TA, Pisoni DB. Some computational analyses of the PBK test: Effects of frequency and lexical density on spoken word recognition. Ear and Hearing. 1999;20:363–371. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199908000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto RT, Osberger MJ, Robbins AM, Renshaw JJ, Myres WA, Kessler K, Pope ML. Comparison of sensory aids in deaf children. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 1989;98:2–7. doi: 10.1177/00034894890980s801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto RT, Svirsky MA, Kirk KI, Robbins AM, Todd S, Riley A. Speech intelligibility of children with multichannel cochlear implants. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 1997;106:35–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osberger MJ, Miyamoto RT, Zimmerman-Phillips S, Kernink JK, Stroer BS, Firzst JB, Novak MA. Independent evaluation of the speech perception abilities of children with the Nucleus 22-channel cochlear implant system. Ear and Hearing. 1991;12(Suppl):66S–80S. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199108001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osberger MJ, Robbins AM, Todd SL, Riley AI. Speech intelligibility of children with cochlear implants. Volta Review. 1994;96:169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB. Cognitive factors and cochlear implants: Some thoughts on perception, learning, and memory in speech perception. Ear and Hearing. 2000;21:70–78. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200002000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB, Cleary M, Geers AE, Tobey EA. Individual differences in effectiveness of cochlear implants in prelingually deaf children: Some new process measures of performance. Volta Review. 2000;101:111–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB, Geers A. Working memory in deaf children with cochlear implants: Correlations between digit span and measures of spoken language processing. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 2000;109:92–93. doi: 10.1177/0003489400109s1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remez RE, Fellowes JM, Pisoni DB, Goh WD, Rubin PE. Multimodal perceptual organization of speech: Evidence from tone analogs of spoken utterances. Speech Communication. 1999;26(1–2):65–73. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6393(98)00050-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remez RE, Rubin PE, Berns SM, Pardo JS, Lang JM. On the perceptual organization of speech. Psychological Review. 1994;101:129–156. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.101.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remez RE, Rubin PE, Pisoni DB, Carrell TD. Speech perception without traditional speech cues. Science. 1981;212:947–950. doi: 10.1126/science.7233191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie WC, Bhatia TK. Handbook of Child Language Acquisition. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins AM, Bollard PM, Green J. Language development in children implanted with the Clarion cochlear implant. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 1999;108(Suppl 117):113–118. doi: 10.1177/00034894991080s423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins AM, Svirsky MA, Kirk KI. Children with implants can speak, but can they communicate? Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1997;117:155–160. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(97)70168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönnberg J, Andersson J, Samuelsson S, Söderfeldt B, Lyxell B, Risberg J. A speechreading expert: The case of MM. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999;42:5–20. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4201.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum LD. How special is audiovisual speech integration? Current Psychology of Cognition. 1994;13:110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum LD, Johnson JA, Saldaña HM. Point-light facial displays enhance comprehension of speech in noise. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1996;39:1159–1170. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3906.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum LD, Saldaña HM. An audiovisual test of kinematic primitives for visual speech perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1996;22:318–331. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.22.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staller S, Beiter AL, Brimacombe JA, Mecklenberg D, Arndt P. Pediatric performance with the Nucleus 22-channel implant system. American Journal of Otology. 1991;12:126–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein BE, Meredith MA. The Merging of the Senses. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sumby WH, Pollack I. Visual contribution of speech intelligibility in noise. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1954;26:212–215. [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield Q. Some preliminaries to a comprehensive account of audiovisual speech perception. In: Dodd B, Campbell R, editors. Hearing by Eye: The Psychology of Lip-Reading. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1987. pp. 3–51. [Google Scholar]

- Svirsky MA, Robbins AM, Kirk KI, Pisoni DB, Miyamoto RT. Language development in children with profound and prelingual hearing loss, without cochlear implants. Psychological Science. 2000;11:153–158. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin JB, Spencer L, Flock S, Tyler R, Gantz B. A comparison of language achievement in children with cochlear implants and children using hearing aids. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 1999;42:497–511. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4202.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler RS, Fryauf-Bertschy H, Kelsay DMR, Gantz BJ, Woodworth GG, Parkinson A. Speech perception by prelingually deaf children using cochlear implants. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1997;117:180–187. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(97)70172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler RS, Fryauf-Bertschy H, Kelsay DMR, Gantz BJ, Woodworth GG. Speech perception in prelingually implanted children after four years. In: Honjo I, Takahashi H, editors. Cochlear Implant and Related Science Update (Advances in Otolaryngology 52) Basel: Karger; 1997. pp. 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler RS, Opie JM, Fryauf-Bertschy H, Gantz BJ. Future directions for cochlear implants. Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology. 1992;16:151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler RS, Parkinson AJ, Fryauf-Bertschy H, Lowder MW, Parkinson WS, Gantz BJ, Kelsay DMR. Speech perception by prelingually deaf children and postlingually deaf adults with cochlear implants. Scandinavian Journal of Audiology. 1997;26(Suppl 46):65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler RS, Tomblin JB, Spencer LJ, Kelsay DMR, Fryauf-Bertschy H. How speech perception through a cochlear implant affects language and education. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery in press. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler RS, Tye-Murray N, Lansing CR. Electrical stimulation as an aid to speechreading. Special Issue: New reflections on speechreading. Volta Review. 1988;90(5):119–148. [Google Scholar]

- Vatikiotis-Bateson E, Munhall KG, Hirayama M, Lee YV, Terzepoulos D. The dynamics of audiovisual behavior in speech. In: Stork DG, Hennecke ME, editors. Speechreading by Humans and Machines. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1997. pp. 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Waltzman S, Cohen NL. Effects of cochlear implantation on the young deaf child. American Journal of Otology. 1988;19:158–162. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman-Phillips S, Osberger MJ, Robbins AM. Infant toddler Meaningful Auditory Integration Scale (IT-MAIS) Sylmar, CA: Advanced Bionics Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zwolan TA, Zimmerman-Phillips S, Ashbaugh CJ, Hieer SJ, Kileny PR, Telain SA. Cochlear implantation of children with minimal open-set speech recognition. Ear and Hearing. 1997;18:240–251. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199706000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reference Notes

- 1.Haskins H. Unpublished master’s thesis. Northwestern University; Evanston, IL: 1949. A phonetically balanced test of speech discrimination for children. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osberger MJ, Fisher LM. Preoperative predictors of postoperative implant performance in young children. Paper presented at the 7th Symposium on Cochlear Implants in Children; Iowa City, IA. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pisoni DB, Svirsky MA, Kirk KI, Miyamoto RT. Looking at the “stars”: A first report on the intercorrelations among measures of speech perception, intelligibility and language in pediatric cochlear implant users, Progress Report on Spoken Language Processing #21. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University, Department of Psychology; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svirsky MA, Sloan RB, Caldwell M, Miyamoto RT. Speech intelligibility of prelingually deaf children with multichannel cochlear implants. Paper presented at the Seventh Symposium on Cochlear Implants in Children; Iowa City, IA. 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vatikiotis-Bateson E, Munhall KG, Kasahara Y, Garcia F, Yehia H. Characterizing audiovisual information during speech. Paper presented at the International Conference on Spoken Language Processing; Philadelphia, PA. 1996. [Google Scholar]