Abstract

We have exploited a typically undesired elementary step in cross-coupling reactions, β-hydride elimination, to accomplish palladium-catalyzed dehydrohalogenations of alkyl bromides to form terminal olefins. We have applied this method, which proceeds in excellent yield at room temperature in the presence of a variety of functional groups, to a formal total synthesis of (R)-mevalonolactone. Our mechanistic studies establish that the rate-determining step can vary with the structure of the alkyl bromide, and, most significantly, that L2PdHBr (L=phosphine), an often-invoked intermediate in palladium-catalyzed processes such as the Heck reaction, is not an intermediate in the active catalytic cycle.

INTRODUCTION

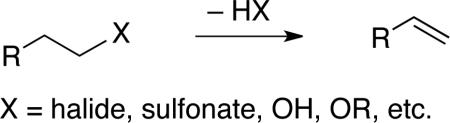

The elimination of HX to form an olefin is one of the most elementary transformations in organic chemistry (eq 1).1,2 However, harsh conditions, such as the use of a strong Brønsted acid/base or a high temperature (which can lead to poor functional-group compatibility and to olefin isomerization) are often necessary for this seemingly straightforward process. For example, many classical methods for the dehydration of alcohols, such as the Chugaev elimination via a xanthate ester,3 require elevated temperature (e.g., 100–250 °C). More recently, through the development of sophisticated derivatizing agents such as the Burgess4 and Martin5 reagents, some of the deficiencies of the older approaches have been remedied; however, while these particular methods are effective for net dehydrations of secondary and tertiary alcohols, they are not generally useful for primary alcohols.

|

(1) |

For the dehydration of primary alcohols, the Sharpless–Grieco reaction, wherein the alcohol is converted into a selenide and then a selenoxide prior to elimination, is a particularly effective approach.6 Due to the mildness of the conditions (e.g., elimination at room temperature or below), this method has been widely used in organic synthesis.7 However, drawbacks of this reaction include the generation of a stoichiometric amount of a toxic arylselenol byproduct and difficulties in separating the desired olefin from selenium-based impurities.

With respect to metal-catalyzed methods for HX elimination, Oshima reported in 2008 that CoCl2/IMes•HCl effects the formation of olefins from alkyl halides (but not sulfonates) in the presence of two equivalents of a Grignard reagent (Me2PhSiCH2MgCl).8 Although this investigation focused on the regioselective synthesis of terminal olefins from secondary alkyl bromides, Oshima also applied his method to two primary alkyl halides, which provided good yields of the terminal olefin (79– 96%), along with small amounts of the internal olefin (2–8%). Furthermore, while our study was underway, Frantz reported that Pd(P(t-Bu)3)2 catalyzes the elimination/isomerization of certain enol triflates to 1,3-dienes.9

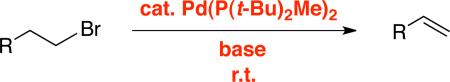

The development of mild new methods for the elimination of HX to generate an olefin, a fundamental transformation in organic synthesis, persists as a worthwhile endeavor. In this report, we describe the use of a palladium catalyst to achieve elimination reactions of primary alkyl electrophiles and furnish terminal olefins in excellent yield at room temperature (eq 2).

|

(2) |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

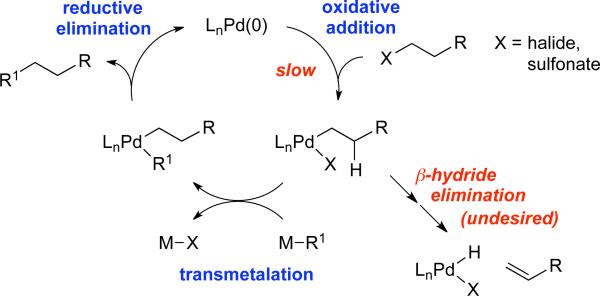

In recent years, we and others have pursued the development of metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of alkyl electrophiles that contain β-hydrogens.10 Historically, it was believed that two substantial impediments to accomplishing this objective were slow oxidative addition and, if oxidative addition could be achieved, rapid β-hydride elimination in preference to transmetalation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Outline of a possible pathway for (and impediments to) palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling of an alkyl electrophile.

Having made progress in the development of palladium-based catalysts for cross-coupling alkyl electrophiles,10d,f we sought to exploit these advances to devise a mild method for H–X elimination of alkyl electrophiles to form olefins, since the oxidative-addition challenge had presumably been solved, and the “deleterious” β-hydride elimination process (Figure 1) would now be the desired pathway. Indeed, in our earlier efforts to achieve cross-coupling reactions of alkyl electrophiles, we had noted that significant, although not synthetically useful, quantities of the olefin were sometimes observed as undesired side products (e.g., up to 31% in the case of a Suzuki coupling11).

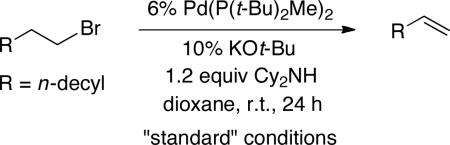

Upon examining an array of reaction parameters, we have been able to develop a palladium-catalyzed method for olefin synthesis that accomplishes the dehydrohalogenation of a primary alkyl bromide at room temperature with excellent efficiency (Table 1, entry 1). The ligand of choice is P(t-Bu)2Me, which we have previously established is useful for palladium-catalyzed Suzuki reactions of alkyl electrophiles.12 Essentially no 2-dodecene is detected (<1%).13

Table 1.

Palladium-Catalyzed Elimination of an Alkyl Bromide to Generate an Olefin: Influence of Reaction Parameters

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | variation from the “standard” conditions | yield (%)a |

| 1 | none | 98 (91) |

| 2 | no Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2 | 3 |

| 3 | no KOt-Bu | 95 (81) |

| 4 | no Cy2NH | 13 |

| 5 | Pd(P(t-Bu)3)2, instead of Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2 | 3 |

| 6 | Pd(PCy3)2, instead of Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2 | 12 |

| 7 | Pd(PPh3)4, instead of Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2 | 3 |

| 8 | Cy2NMe, instead of Cy2NH | 42 |

| 9 | Cs2CO3, instead of Cy2NH | 28 |

| 10 | 3% Pd2(dba)3 + 12% P(t-Bu)2Me, instead of Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2 | 96 (76) |

| 11 | 3%, instead of 6%, Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2 | 90 (75) |

Determined via gas chromatography with the aid of a calibrated internal standard (average of two experiments); the yield after 4 h is given in parentheses.

In the absence of Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2, virtually no olefin is formed (Table 1, entry 2). Although KOt-Bu is not necessary (entry 3), a poor yield is obtained in the absence of Cy2NH (entry 4). Palladium complexes that bear other hindered trialkylphosphines (entries 5 and 6) or PPh3 (entry 7) are comparatively ineffective, as are other Brønsted bases (entries 8 and 9). An active catalyst can be generated in situ from Pd2(dba)3 and P(t-Bu)2Me (entry 10), and a lower loading of Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2 can be employed with only a small loss in yield (entry 11). termined via 1H NMR spectroscopy) is given in brackets. bDue to the volatility of allylbenzene, the yield was determined via gas chromatography versus a calibrated internal standard (average of two experiments). cKOt-Bu loading: 2.5%. dKOt-Bu loading: 20%.

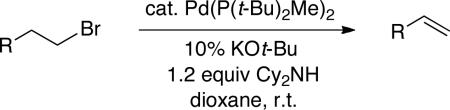

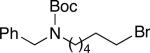

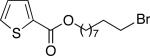

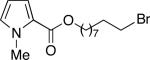

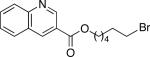

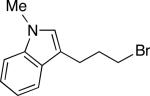

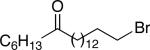

We have determined that this Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2-catalyzed method can be applied to the room-temperature dehydrohalogenation of a range of primary alkyl bromides, furnishing the desired terminal olefins in generally high yields (Table 2; for each reaction essentially no (<2%) product is formed in the absence of Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2).14 Through the use of a higher catalyst loading (compare entries 1–3), more hindered (γ- and β-branched) electrophiles can be converted to olefins nearly quantitatively. Allylbenzene, too, can be generated in excellent yield and with no isomerization to β-methylstyrene (entry 4). A wide array of functional groups are compatible with this mild method for elimination of HBr, including a silyl ether (entry 5), a carbamate (entry 6), esters (entries 7–12), an aryl chlo-ride (entry 8), heteroaromatic substituents (oxygen, sulfur, and nitrogen; entries 9–13), and a ketone (entry 14); on the other hand, preliminary studies indicate that the presence of a primary alcohol, an aldehyde, or a nitroarene can be problematic.15 A primary alkyl bromide reacts exclusively in the presence of a secondary bromide (entry 15),16 a primary tosylate (entry 16), and a primary chloride (entry 17). For most of these elimination processes, virtually no (<2%) isomerization to the internal olefin is observed.

Table 2.

Palladium-Catalyzed Elimination Reactions of Alkyl Bromides

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | yield (cat. loading) a |

| 1 |

|

94 (6) |

| 2 |

|

98 (14) |

| 3 |

|

99 (30) |

| 4 |

|

100 b (8) |

| 5 |

|

88 (8) |

| 6 |

|

98 (8) |

| 7 |

|

86 (8) |

| 8 |

|

91 (5) |

| 9 |

|

86 (8) |

| 10 |

|

96 (8) |

| 11c |

|

92 (8) [17:1] |

| 12 |

|

96 (12) |

| 13 |

|

84 (7) |

| 14 |

|

92 (15) |

| 15 d |

|

78 (12) |

| 16 |

|

86 (11) [6:1] |

| 17 |

|

89 (6) |

Both values are percentages. The isolated yield is provided (average of two experiments). In all cases, >98% of the unpurified elimination product is the terminal olefin, with the exception of entries 11 and 16, where the ratio of terminal:internal olefins (determined via 1H NMR spectroscopy) is given in brackets.

Due to the volatility of allylbenzene, the yield was determined via gas chromatography versus a calibrated internal standard (average of two experiments).

KOt-Bu loading: 2.5%.

KOt-Bu loading: 20%.

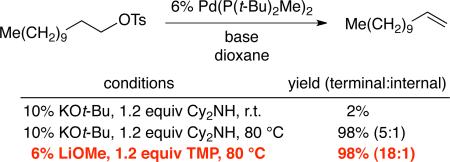

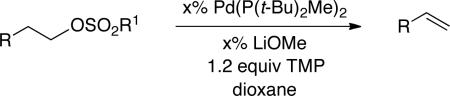

When 1-iodododecane is subjected to the method developed for the dehydrohalogenation of alkyl bromides (Table 1), only a small amount of 1-dodecene (20% yield) is generated; N-alkylation of dicyclohexylamine is the major product. Furthermore, under the same conditions, essentially no elimination is observed with a primary alkyl chloride or tosylate, presumably due to the relatively high barrier to oxidative addition to Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2.17 On the other hand, at elevated temperature, elimination of a primary tosylate to the desired terminal olefin can proceed in excellent yield (eq 3). It is worth noting that alkyl tosylates are not suitable substrates for Oshima's cobalt-catalyzed elimination, likely because of difficulty in achieving homolytic cleavage of the C–O bond;8 in contrast, under our conditions, C–O scission is probably accomplished through an SN2 pathway.12a,c

|

(3) |

Palladium-catalyzed eliminations of more hindered (γ- and β-branched) primary alkyl tosylates also proceed in excellent yield (Table 3, entries 2 and 3). Interestingly, a secondary alkyl tosylate undergoes elimination, predominantly generating the internal 2-alkene (entry 4; 2:1 internal:terminal). Furthermore, not only an alkyl tosylate, but also a mesylate, can be eliminated to form an olefin with good efficiency (entry 5). Perhaps due in part to the elevated reaction temperature, small amounts of olefin isomerization are sometimes observed in eliminations of alkyl sulfonates (entries 1 and 5), and preliminary experiments indicate that the functional-group tolerance of the method is limited. For each elimination illustrated in Table 3, essentially no olefin is produced in the absence of Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2 (<2%).

Table 3.

Palladium-Catalyzed Elimination Reactions of Alkyl Sulfonates

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | temperature (°C), x | yield a |

| 1 |

|

80, 6 | 98 [18:1] |

| 2 |

|

90, 6 | 97 |

| 3 |

|

100, 17 | 96 |

| 4 |

|

100, 25 | 94 [1:2] |

| 5 |

|

80, 12 | 90 [14:1] |

The isolated yield (%) is provided (average of two experiments). For eliminations in which >2% of the internal olefin is generated, the ratio of terminal:internal olefins (determined via 1H NMR spectroscopy) is given in brackets.

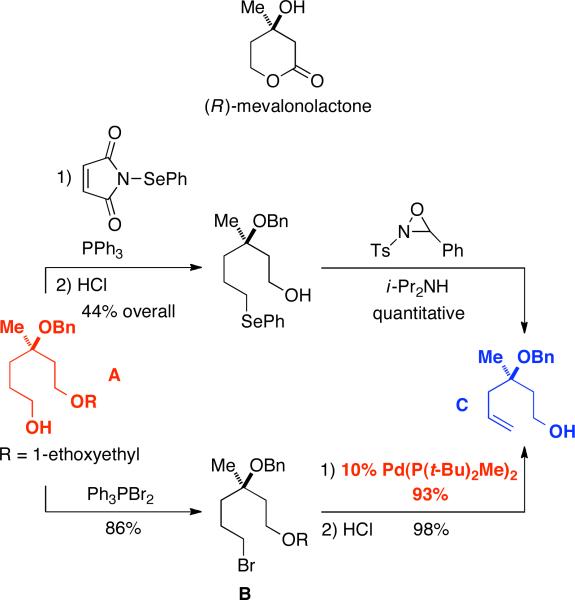

We have applied our palladium-catalyzed elimination process to a formal total synthesis of (R)-mevalonolactone. Spencer described the preparation of this bioactive compound from nerol via alcohol A, which was transformed into olefin C via a Sharpless–Grieco sequence (top of Figure 2).18 Spencer noted that the conversion of the alcohol to the selenide “proved to be the only difficult step in the synthesis”.19

Figure 2.

Conversion of an alcohol to an olefin, en route to (R)-mevalonolactone: Spencer (top); this study (bottom).

We have effected the transformation of alcohol A into olefin C in 78% overall yield through our palladium-catalyzed elimination process (bottom of Figure 2). Thus, treatment of A with Ph3PBr2 furnishes primary alkyl bromide B. Next, palladium-catalyzed dehydrohalogenation under our standard conditions at room temperature affords the desired olefin in excellent yield (93%). Finally, removal of the 1-ethoxyethyl protecting group generates Spencer's intermediate C.

Mechanism

Our current hypothesis is that these palladium-catalyzed elimination reactions follow the pathway outlined in Figure 3 (throughout this section, L= P(t-Bu)2Me). Thus, oxidative addition of the alkyl bromide to L2Pd proceeds via an SN2 process to generate L2Pd(CH2CH2R)Br (D).12a,c Dissociation of one phosphine furnishes a 14-electron palladium adduct (E), which undergoes β-hydride elimination to provide a palladium olefin–hydride intermediate (F). In the presence of base (Cy2NH) and L, palladium complex F affords [Cy2NH2]Br, the olefin, and L2Pd.

Figure 3.

Outline of a possible mechanism for Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2-catalyzed dehydrobromination reactions.

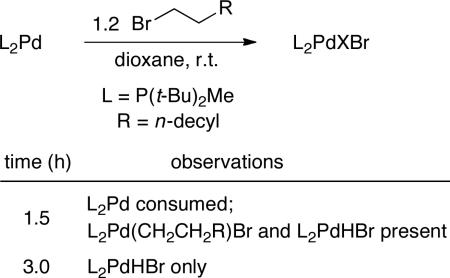

In order for our mechanistic study to be more tractable, we chose to focus our investigation on palladium-catalyzed dehydrobrominations in the absence of KOt-Bu, a process that also occurs in excellent yield (entry 3 of Table 1).20 With regard to the oxidative-addition step of the proposed catalytic cycle, we have previously established that L2Pd reacts with 1-bromo-3-phenylpropane in Et2O at 0 °C, and we have crystallographically characterized the Pd(II) adduct.12b We have now examined the reaction of 1-bromododecane with L2Pd in dioxane at room temperature, and we have determined that oxidative addition is complete within 1.5 hours, affording a mixture of L2Pd(CH2CH2R)Br and L2PdHBr21 (eq 4). After an additional 1.5 hours, this mixture has proceeded to form L2PdHBr quantitatively. Taken together, these data indicate that oxidative addition and then β-hydride elimination are chemically and kinetically competent initial steps of the catalytic cycle.

|

(4) |

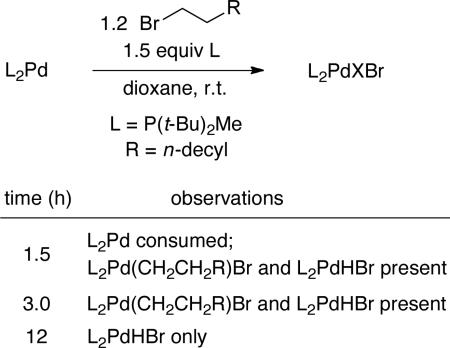

We have investigated the impact of added P(t-Bu)2Me on the reaction of 1-bromododecane with L2Pd (eq 5). The rate of consumption of L2Pd is unaffected by the additional ligand, whereas the rate of formation of L2PdHBr is inhibited, consistent with the suggestion that L2Pd (rather than L1Pd or L3Pd) is the species undergoing oxidative addition and that ligand dissociation precedes β-hydride elimination.22

The rate law for the palladium-catalyzed dehydrobromination of 1-bromododecane is first order in L2Pd, fractional (first order at lower concentration, zeroth order at higher concentration) order in the alkyl bromide, and zeroth order in Cy2NH. According to 31P NMR spectroscopy, L2Pd(CH2CH2R)Br is the predominant resting state of palladium during the early stages of the reaction (small amounts of L2Pd and L2PdHBr are also present; as the reaction progresses, the proportion of L2PdHBr increases). These data are consistent with oxidative addition and a subsequent step each being partially rate-determining.

|

(5) |

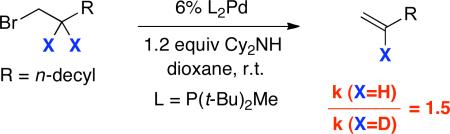

For the stoichiometric chemistry of L2Pd, we have established that β-hydride elimination is impeded by the addition of excess P(t-Bu)2Me (eq 5); we have similarly determined that the palladium-catalyzed dehydrohalogenation of 1-bromododecane is inhibited by added P(t-Bu)2Me. Furthermore, we observe a modest kinetic isotope effect when comparing the rate of elimination of 1-bromododecane with that of 1-bromo-2,2-dideuteriododecane (kH/kD = 1.5; eq 6). Collectively, these data are consistent with β-hydride elimination being the other partially rate-determining step.

|

(6) |

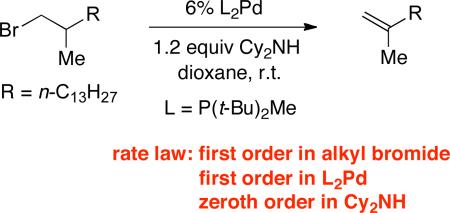

In a previous study, we have demonstrated that oxidative addition of a primary alkyl electrophile to Pd/P(t-Bu)2Me preferentially proceeds through an SN2 pathway.12a,c If oxidative addition is indeed partially rate-determining for the dehydrohalogenation of 1-bromododecane, then one might anticipate that, in the case of a more hindered alkyl bromide, oxidative addition would be entirely rate-determining. The rate law the dehydrobromination of a β-branched primary alkyl bromide and established that the rate law is first order in the alkyl bromide, first order in L2Pd, and zeroth order in Cy2NH (eq 7). Furthermore, 31P NMR spectroscopy reveals that L2Pd is the predominant resting state of the catalyst. Taken together, these observations are consistent with oxidative addition being the rate-determining step for the palladium-catalyzed elimination of this more hindered alkyl bromide.

|

(7) |

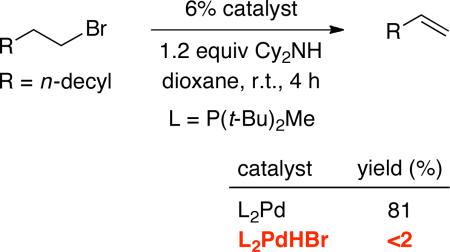

Interestingly, L2PdHBr is not an intermediate in the primary catalytic cycle. Thus, treatment of 1-bromododecane with 6% L2PdHBr, rather than L2Pd, results in essentially no 1-dodecene (eq 8).

|

(8) |

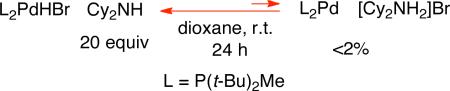

We have established that Cy2NH is not a sufficiently strong Brønsted base to drive the acid-base equilibrium illustrated in eq 9 to the right, thereby producing L2Pd from L2PdHBr.23,24 Thus, it appears that, during our palladium-catalyzed dehydrobromination process, a palladium–hydride other than L2PdHBr is undergoing reductive elimination to regenerate Pd(0).

|

(9) |

Because each turnover of catalyst generates [Cy2NH2]Br, a question arises as to why this ammonium salt does not protonate L2Pd to form L2PdHBr, thereby deactivating the palladium catalyst. In fact, during the course of the dehydrobromination process, we do observe a slow accumulation of L2PdHBr. Fortunately, however, the poor solubility of [Cy2NH2]Br in dioxane impedes this deleterious protonation, i.e., [Cy2NH2]Br precipitates faster than it protonates L2Pd.25

Although we had previously postulated that the formation of a relatively stable L2PdHCl (L=PCy3) complex could be the origin of low catalyst activity in a Heck reaction of an aryl chloride,23 we had not fully appreciated the importance of avoiding the formation of L2PdHBr in developing a mild Pd/P(t-Bu)2Me-catalyzed method for the dehydrohalogenation of alkyl bromides. The fortuitous solubility properties of [Cy2NH2]Br, combined with the unanticipated regeneration of Pd(0) prior to the formation of L2PdHBr (L=phosphine), are likely critical to the success of this process. The latter observation regarding the timing of reductive elimination is worth considering when contemplating the mechanism of Heck reactions.26

CONCLUSIONS

Although the elimination of HX to form an olefin is a classic transformation in organic chemistry, there remains a need for mild new methods for accomplishing this fundamental process. Herein, we have exploited a generally undesired elementary step in cross-coupling reactions, β-hydride elimination, to achieve palladium-catalyzed dehydrohalogenations of alkyl bromides. This method, which we have applied to a formal total synthesis of (R)-mevalonolactone, enables the efficient synthesis of terminal olefins at room temperature in the presence of a variety of functional groups, including heterocycles. Our mechanistic studies establish that the rate-determining step can vary with the structure of the alkyl bromide. Most significantly, we have determined that L2PdHBr (L=phosphine), an often-invoked intermediate in palladium-catalyzed processes such as the Heck reaction, is not an intermediate in the active catalytic cycle.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Support has been provided by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of General Medical Sciences, grant R01– GM62871), an American Australian Association Merck Company Foundation Fellowship (A.C.B.), the Paul E. Gray (1954) Endowed Fund for the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program (A.L.), and the John Reed Fund (A.L.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Experimental procedures and compound characterization data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.a McMurry J. Organic Chemistry. Thomson; Belmont, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]; b Smith JG. Organic Chemistry. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kostikov RR, Khlebnikov AF, Sokolov VV. In: Science of Synthesis. de Meijere A, editor. 47b. Thieme; Stuttgart: 2010. pp. 771–881. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Chugaev L. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1899;32:3332–3335. [Google Scholar]; b Fuchter MJ. In: Name Reactions for Functional Group Transformations. Li JJ, editor. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2007. pp. 334–342. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Burgess EM, Penton HR, Jr., Taylor EA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970;92:5224–5226. [Google Scholar]; b Holsworth DD. In: Name Reactions for Functional Group Transformations. Li JJ, editor. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2007. pp. 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a Martin JC, Arhart RJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971;93:4327–4329. [Google Scholar]; b Shea KM. In: Name Reactions for Functional Group Transformations. Li JJ, editor. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2007. pp. 248–264. [Google Scholar]

- 6.a Sharpless KB, Young M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:2697–2699. [Google Scholar]; b Sharpless KB, Young MW. J. Org. Chem. 1975;40:947–949. [Google Scholar]; c Grieco PA, Gilman S, Nishizawa M. J. Org. Chem. 1976;41:1485–1486. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For example, see: Danishefsky SJ, Masters JJ, Young WB, Link JT, Snyder LB, Magee TV, Jung DK, Isaacs RCA, Bornmann WG, Alaimo CA, Coburn CA, Di Grandi MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2843–2859.

- 8.Kobayashi T, Ohmiya H, Yorimitsu H, Oshima K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11276–11277. doi: 10.1021/ja804277x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crouch IT, Dreier T, Frantz DE. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6128–6132. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For reviews and leading references, see: Glasspoole BW, Crudden CM. Nature Chem. 2011;3:912–913. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1210.Kambe N, Iwasaki T, Terao J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4937–4947. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15129k.Rudolph A, Lautens M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:2656–2670. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803611.Netherton MR, Fu GC. In: Topics in Organometallic Chemistry: Palladium in Organic Synthesis. Tsuji J, editor. Springer; New York: 2005. pp. 85–108.Frisch AC, Beller M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:674–688. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461432.Netherton MR, Fu GC. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:1525–1532.

- 11.Netherton MR, Dai C, Neuschütz K, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:10099–10100. doi: 10.1021/ja011306o. See also: Firmansjah L, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11340–11341. doi: 10.1021/ja075245r.

- 12.a Netherton MR, Fu GC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:3910–3912. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021018)41:20<3910::AID-ANIE3910>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kirchhoff JH, Netherton MR, Hills ID, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:13662–13663. doi: 10.1021/ja0283899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hills ID, Netherton MR, Fu GC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:5749–5752. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isomerization of the initially generated olefin by a palladium–hydride intermediate is a well-established side reaction in Heck couplings. For recent examples of isomerizations of olefins catalyzed by palladium hydrides, including Pd(P(t-Bu)3)2HCl, see: Gauthier D, Lindhardt AT, Olsen EPK, Overgaard J, Skrydstrup T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:7998–8009. doi: 10.1021/ja9108424.

- 14.The proportion of internal olefin does not increase as the reaction progresses, and treatment of 1-dodecene with L2PdHBr in dioxane at room temperature does not lead to the generation of internal olefins (however, isomerization is observed at elevated temperature).

- 15.Under our standard conditions (Table 1), in the presence of one equivalent of a primary-amine additive, the dehydrobromination of 1-bromododecane proceeded in ~95% yield. The dehydrobromination was slightly inhibited (55-70% yield, with the balance being unreacted 1-bromododecane) by the addition of one equivalent of an unprotected indole or a nitrile.

- 16.The relative rate of dehydrobromination of 1-bromododecane vs. 1-bromo-2-methylpentadecane (a β-branched alkyl bromide) is ~13.

- 17.For a study of the relative rates of oxidative addition of n-nonyl–X (X=I, Br, Cl, F, OTs) to Pd(P(t-Bu)2Me)2 in THF, see Ref. 12c.

- 18.Ray NC, Raveendranath PC, Spencer TA. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:9427–9432. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spencer also notes that the selenide was “tenaciously contaminated” by a selenium-containing impurity.

- 20.Due to the slow accumulation of L2PdHBr during the course of the palladium-catalyzed dehydrobromination (vide infra), our mechanistic studies have focused on the early stages of the reaction.

- 21.Throughout this discussion, L2PdHBr refers to trans-L2PdHBr.

- 22.This contrasts with Yamamoto's studies of thermal decomposition of trans-L2PdEt2, wherein β-hydride elimination proceeds predominantly without ligand dissociation: Ozawa F, Ito T, Yamamoto A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:6457–6463.

- 23.Treatment of L2Pd with [Cy2NH2]Br in dioxane at room temperature leads to very slow formation of L2PdHBr. For related observations with a different ligand (PCy3), halide (Cl), and base (Cy2NMe), see: Hills ID, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13178–13179. doi: 10.1021/ja0471424.

- 24.On the other hand, KOt-Bu does react with L2PdHBr to generate L2Pd in quantitative yield. However, if KOt-Bu, rather than Cy2NH, is employed as the stoichiometric base, then the elimination does not proceed cleanly, and there is a considerable background reaction (E2).

- 25.The decreased efficiency of Cy2NMe relative to Cy2NH (Table 1, entry 8 versus entry 1) may be due to the greater solubility in dioxane of [Cy2NHMe]Br compared with [Cy2NH2]Br, which leads to more protonation of L2Pd to form inactive L2PdHBr.

- 26.Oestreich M, editor. The Mizoroki–Heck Reaction. Wiley; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.