Abstract

Waste materials containing Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), a suspected endocrine disruptor and reasonably anticipated human carcinogen, are typically disposed of in landfills. Despite this, very few studies had been conducted to isolate and identify DEHP-degrading bacteria in landfill leachate. Therefore, this study was conducted to isolate and characterize bacteria in landfill leachate growing on DEHP as the sole carbon source and deteriorating PVC materials. Four strains LHM1, LHM2, LHM3 and LHM4, not previously reported as DEHP-degraders, were identified via 16S rRNA gene sequence. Gram-positive strains LHM1 and LHM2 had a greater than 97% similarity with Chryseomicrobium imtechense MW 10(T) and Lysinibacillus fusiformis NBRC 15717(T), respectively. Gram-negative strains LHM3 and LHM4 were related to Acinetobacter calcoaceticus DSM 30006(T) (90.7% similarity) and Stenotrophomonas pavanii ICB 89(T) (96.0% similarity), respectively. Phylogenetic analysis also corroborated these similarities of strains LHM1 and LHM2 to the corresponding bacteria species. Strains LHM2 and LHM4 grew faster than strains LHM1 and LHM3 in the enrichment where DEHP was the sole carbon source. When augmented to the reactors with PVC shower curtains containing DEHP, strains LHM1 and LHM2 developed greater optical densities in the solution phase and thicker biofilm on the surfaces of the shower curtains.

Keywords: Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, landfill leachate, Gram positive, PVC shower curtains

INTRODUCTION

Phthalic acid diesters (PAEs) are synthetic compounds that have been widely used in plastic manufacturing to improve the mechanical properties of plastic resins. In addition, PAEs have been used in nail polish, perfumes and skin moisturizers to enhance penetration and hold scent and color of the products. They are also used in toys, vinyl gloves, shoes and food wraps. [1] World production of PAEs was increased from 1.8 million tons in 1975 to 2.4 million tons in 1993 and 3 million tons in 2005. [2]

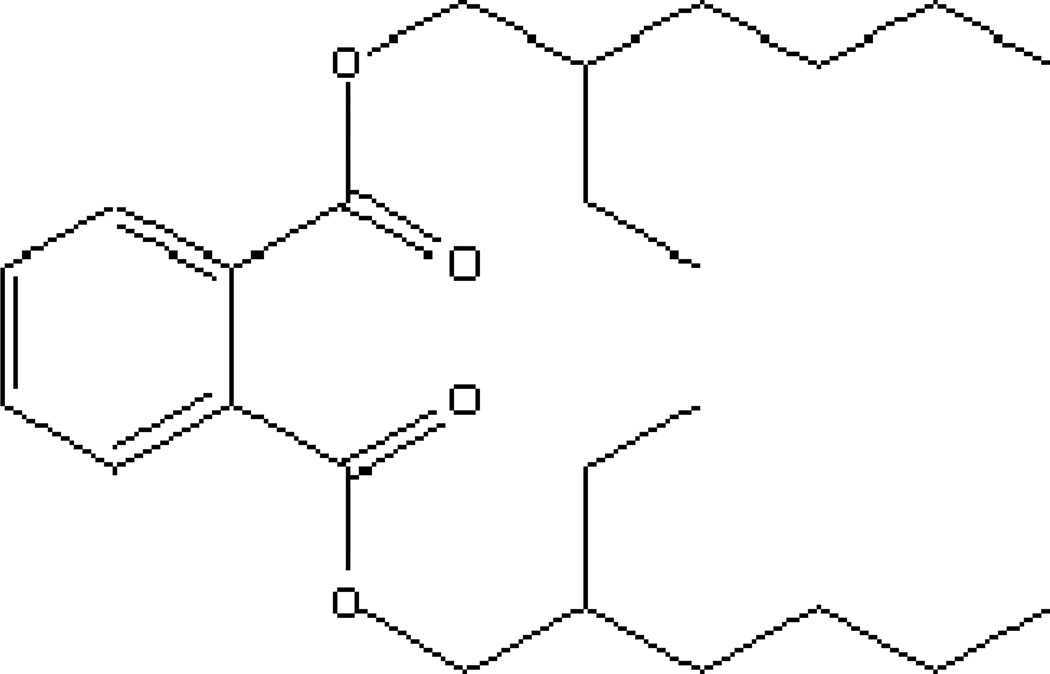

Among the PAEs, Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) is one of the most produced and widely used PAEs. For example, 23% by weight of the world production of PAEs in 1979 was DEHP. [3] DEHP (Fig. 1) has a low water solubility (0.285 mg L−1 at 24 °C), long side chain and high octanol-water partitioning coefficient (log Kow = 7.50) (Table 1), which makes it relative stable in natural environment and, consequently, difficult to degrade. However, several bacterial strains, mostly Gram-negative, were found capable of degrading DEHP under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. For example, DEHP was degraded by Pseudomonas fluoresences FS1 isolated from activated sludge; Sphingomonas sp. and Corynebacterium sp. isolated from river sediment and petrochemical sludge; Rhodococcus rhodochrous, Corynebacterium nitrilophilus, Gordonia polyisoprenivorans, Mycobacterium sp., Pseudomonas acidovorans and Rhodococcus erythropolis isolated from soils; and Actinomycetes, Agrobacterium sp., Burkholderia sp. and Sphingomonas sp. isolated from microcosm biofilm. [2,4–8]

Fig. 1.

Molecular structure of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), a suspected endocrine disruptor and reasonably anticipated human carcinogen.

Table 1.

Physio-chemical characteristics of di-(2ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP).

| Chemical Formula |

Molecular weight (g/mol) |

Melting Point (°C) |

Boiling Point (°C) |

Density (kg/m3) |

Vapor Pressure (10−8 kPa) |

Water Solubility (mg/L) |

Partitioning Coefficient (log Kow) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C24H38O4 | 350.97 | −47 | 384 | 984 (20 °C) |

1.33 | 0.285 (24 °C) |

7.50 |

DEHP is physically rather than chemically bonded to the plastic structure so that they can easily release and leach into the environment. [9] DEHP concentrations have been found in landfill leachate, activated sludge, soils, sediments, and estuaries as well as on groundwater resources. [10] Several studies elucidated that DEHP could be linked to hepatocellular tumors and are developmental and reproductive toxicants. [11] For this matter, concerns with respect to its production and occurrence in the environment have increased in recent years.

Most materials containing DEHP are typically disposed of in landfills as the endpoint of solid waste management. Despite this, very few studies were conducted to isolate and identify DEHP-degrading bacteria in landfill leachate. Therefore, this study aimed to (1) characterize bacteria isolated from landfill leachate capable of using DEHP as the sole carbon source and (2) assess their potential of deteriorating DEHP-containing PVC materials.

METHODOLOGY

Bacteria Isolation and Culture Conditions

Fed batch reactors (FBRs) were run to isolate bacteria that grew in the presence of DEHP. FBRs had 1.5 L of leachate collected from a local landfill (Añasco, PR). One reactor, as the treatment FBR, received a weekly spike of 1.5 mL pure DEHP for five weeks, whereas the other FBR (as the control) did not. Aerobic environment was ensured in both FBRs at a dissolved concentration of ~5 mg L−1.

After five weeks, 0.5 mL of the leachate from the treatment FBR was plated on the Petri dishes containing 0.3% tryptic soy, 1.5% agar, and one mL of trace metals consisted of (in g L−1) 8.5 KH2PO4, 33.4 Na2HPO4 7H2O, 22.5 MgSO4 7H2O, 27.5 CaCl2, 0.25 FeCl2, and 1.7 NH4Cl. The plates were incubated in dark for 2 days at 35 °C.

Based on morphological characteristics, a total of five strains were selected and inoculated for further enrichment in a mineral salt medium (MSM) with DEHP as the sole carbon source as described by Oliver et al.. [5] The MSM consisted of (in g L−1) 2 K2HPO4, 2 KH2PO4, 1.6 NaNO2, 1 NH4Cl, 0.2 MgSO47H2O, 0.05 CaCl2 H2O, 0.02 MnSO4 and 1 mL of trace metals that were comprised of (in g L−1) 0.162 FeCl3 6H2O, 0.014 ZnCl2 4H2O, 0.012 CoCl2 6H2O, 0.012 NaMoO4 2H2O, 0.006 CaCl2 2H2O, 1.21 CuSO4, and 0.392 H3BO3. Pure DEHP was added to the enrichments at 1 mL L−1.

Enrichments were incubated in a water bath at 30 °C at 100 rpm and 2 mL of the enrichments were transferred weekly to fresh medium. Enrichments were transferred more than ten times serially into fresh medium, and the final enrichment was streaked on the plates. Bacterial growth after 10-week enrichment was monitored by measuring an optical density (OD) at a wavelength of 610 nm with a Perkin Elmer UV/VIS Spectrophotometer Lambda 20. Okeke and Frankenberger Jr. [12] utilized an OD measurement for assessment of microbial growth profiles in biodegradation of methyl tertiary butyl ether. An OD measurement was also employed for nitrate respiration and growth of Pseudomonas stutzeri A15. [13] All the mediums were sterilized prior to use by autoclaving at 20 psi and 121 °C for 30 minutes.

Morphological Identification

The isolates were analyzed at a macroscopic level by general morphological description of the colony such as elevation, form and margin using the criteria described by Harley and Prescott. [14] Gram staining was also performed to identify between two major groups of bacteria, Gram-positive and Gram-negative. Cell morphology was observed via a bright field microscopy (BFM) at x100 with an OMANO Opima OM159T equipped with an OPTIXCAM video camera.

Genomic DNA Extraction

Based on the growth on DEHP as the sole carbon source during the enrichment, four isolates were selected for further molecular identification. Extraction of genomic DNA was perform using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit according to standard procedures specified by the manufacturer (Promega). Briefly, the cell pellets from pure culture were re-suspended in a cell lysis solution, which was incubated at 80 °C for 10 minutes. A degradation catalyzer, RNase, was added to the solution and was incubated at 37 °C for 15 minutes. Protein precipitation solution was added and the mixed solution remained on ice for 5 minutes. After washing the DNA pellet with isopropanol and ethanol, the dried DNA pellet was re-suspended. A DNA gel electrophoresis was performed to assess DNA extraction at 1 % of agarose. Basically, DNA extracted (5 µL), Tris-EDTA 1× (6 µL) and bromophenol blue (2 µL) were put on the gel with KB (2 µL), Tris-EDTA 1× (6 µL) and bromophenol blue dye (2 µL) as a marker. The gel was run for 50 minutes at 150 V. After 50 minutes, the gel was removed and put into ethidium bromide solution for 20 seconds. Gel electrophoresis picture was taken with the BioDoC-it Imagining System. DNA concentration was measured using Nanodrop (10000 V 3.52). DNA concentrations were diluted to 15 ng µL−1 before polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification.

Amplification and Sequencing of 16S rRNA Gene

The 16S rRNA is a well-conserved, universal bacterial gene widely used to identify differences among bacteria. [15] The reaction conditions for PCR included an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation (1 min at 94 °C), annealing with two universal primers, 519 F µM (5’-CAGCMGCCGCGGTAATWC-3’) and 1392 R µM (5’-ACGGGCGGTGTGTRC-3’) (1 min at 55 °C), and extension with dNTPs to synthesize the complimentary sequence of DNA (2 min at 72 °C) with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 minutes. PCR amplification was performed with the following reaction components: 15 ng µL−1 of DNA extracted and a master mix solution containing: 1× of buffer, 2.5 mM of MgCl2, 1 pm of 519 F, 1 pm of 1392 R, 4× of BSA, 400 dNTPs µM and 0.026 ug µL-1 of Taq polymerase.

The amplification products (3 µL) were separated by electrophoresis on a 1 % agarose gel with TAE 100× buffer to confirm the amplification of the gene before sequencing. MinElute PCR purification kit from QIAGEN was used to purify PCR product according to manufacturer’s instructions. Strains were selected for further characterization by DNA sequence analysis. The purified PCR product was send to the Sequencing and Genotyping Facility at the University of Puerto Rico at Rio Piedras to sequence. Quality of sequences was analyzed using BioEdit Software. The 16S rRNA gene related taxa was obtained from a GenBank database using Ez Taxon algorithm. Pairwise and multiple-sequence alignment with 16S rRNA gene sequences of closely related organisms (as identified by Ez Taxon analysis) was made by ClustalW program using MEGA ver. 5.05.

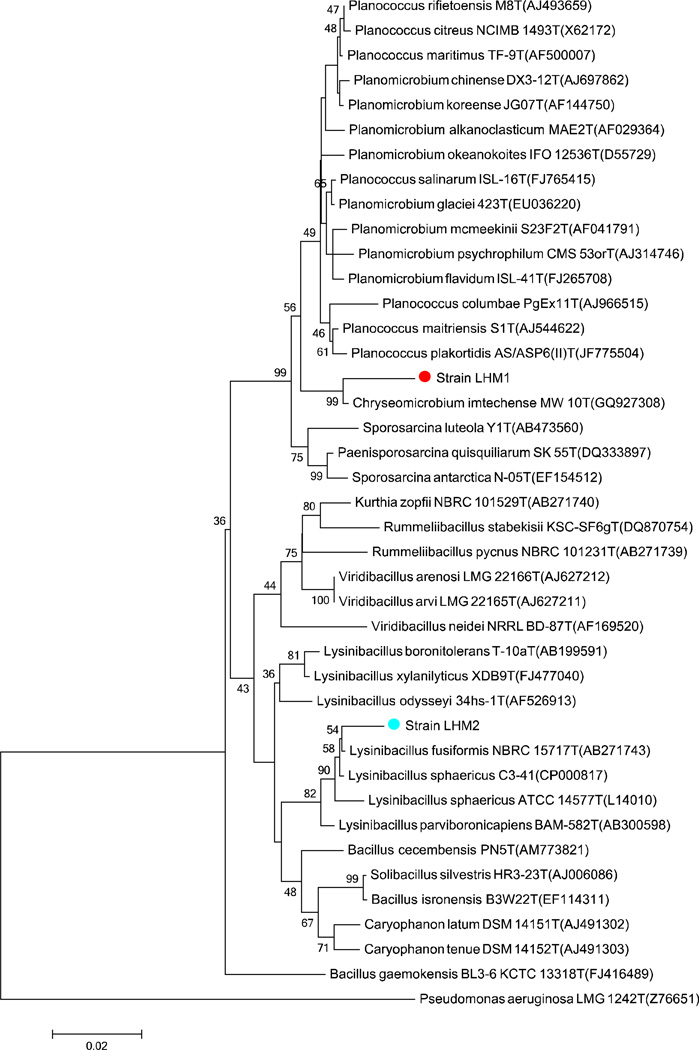

Phylogenic Analysis

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted for strains LHM1 and LHM2 using the Neighbor-Joining method of MEGA ver. 5.05. Bootstrap test and p-distance model were used for the phylogeny analysis. [16] Final trees were constructed with 814 and 832 bp nucleotides for strains LHM1 and LHM2, respectively.

Growth Potential of Strain LHM1 and LHM2 with DEHP-containing PVC Shower Curtains

Three flexible PVC shower curtains were purchased from a local store and cut in the same dimensions (2.5 cm × 15 cm). Water-soluble DEHP concentrations of the shower curtains were 0.8~2.1 % (w/w) of water-soluble total organic carbon (TOC). A glass cylindrical reactor (2 L) had six shower curtain strips (two from each brand) that were hung vertically in a 1.2 L MSM aforementioned in Section Bacteria Isolation and Culture Conditions. One mL of the enriched bacteria solution was taken to a phosphate buffer solution at the 4th day when the OD at 610 nm was on a stationary-growth phase. They were centrifuged at 3,400 rpm for 30 mins and re-suspended in a phosphate buffer solution. Centrifugation and re-suspension were repeated three times prior to bacterial inoculation to the reactors. Initial bacterial concentrations (in 108 CFU 100 mL−1) were 1.57 ± 0.01 (n=2) and 0.97 ± 0.05 (n=2) in the bioaugmented reactors with strain LHM1 and LHM2, respectively.

Aerobic condition was maintained throughout the experiment by aerating the reactors to achieve a dissolved oxygen concentration at ~5 mg L−1. Venting filters were used to protect the reactors from external contaminants through air inlets and exhausts. The reactors were run for more than one month and OD at 610 nm was periodically monitored.

Analysis of Water-Soluble TOC / DEHP and Shower Curtains Surfaces

For analysis of water-soluble DEHP and TOC concentrations, the shower curtain strips were placed in the reactor containing the MSM amended with 200 mg L−1 sodium azide (NaN3) to inhibit the microbial growth. The reactors were incubated in a water bath at 30 °C at 100 rpm for >5 weeks. Aliquot samples were taken at a time interval for the TOC and DEHP analyses.

Water-soluble TOC were analyzed via TOC Reagent Set (Hach Method 10129). For water-soluble DEHP analysis, the aqueous samples were extracted with dichloromethane at a volumetric ratio of 10:1 (sample:dichloromethane) and put on a shaker for 15 min at 100 rpm. Dichloromethane on the bottom of the extraction vial was transferred to a 2 mL gas chromatography vial and allowed to air dry (at least 10 hrs). One mL of hexane was then added to the GC vial that was vortexed prior to analysis with a gas chromatograph (GC, Varian CP3800). Recovery percentage was 98% for DEHP. The GC was equipped with an electron capture detector and DB-5 capillary column (15 m; 0.25 um film thickness; 0.25 mm ID) (Phenomenex, USA). One µL was injected from an automatic sample tray to the GC. The initial column temperature was set at 100 °C for one min, increased by 20 °C min−1 to 280 °C, and held for two mins. Injector and detector temperatures were set at 250 and 300 °C, respectively. Helium was used as a carrier at a flow rate of two mL min−1 and nitrogen was a make-up gas at a flow rate of 25 mL min−1.

The surface of the shower curtains was monitored after air-drying overnight by SEM (JEOL JSM-6390 Scanning Electron Microscope) operated at 5 keV. SEM samples were coated with gold using a Denton Vacuum Desk IV sputter-coater to improve the conductivity of the samples and thus the quality of the images.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

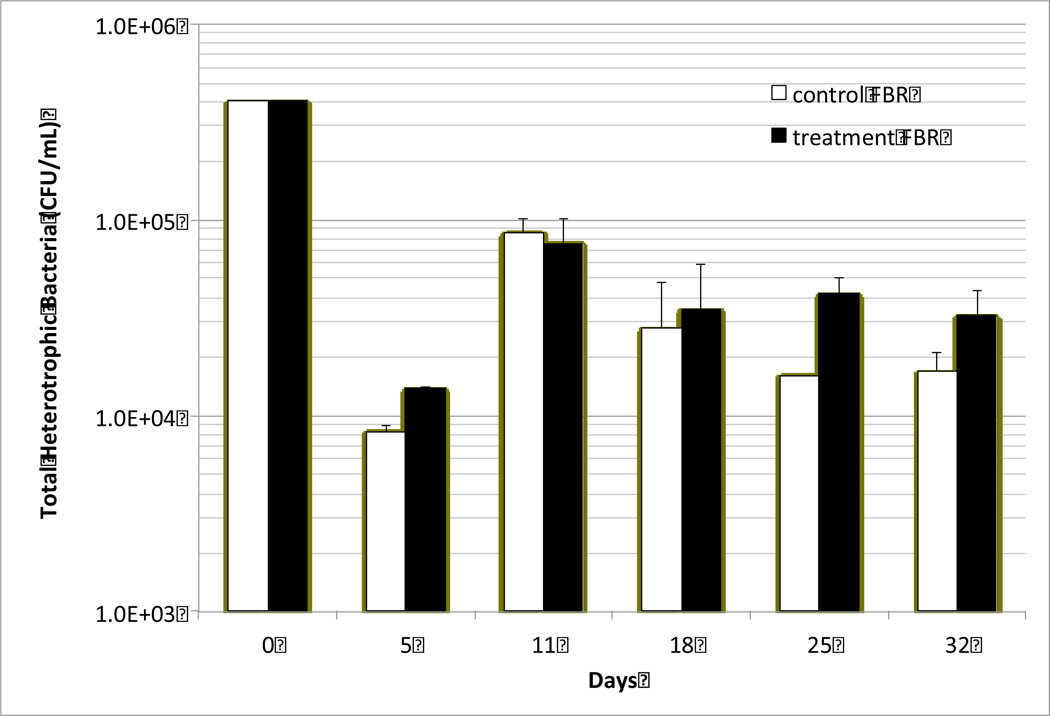

Total Heterotrophic Bacteria Growth in the Presence of High DEHP Concentration

Figure 2 shows the trend of total heterotrophic bacteria (THB) growth in landfill leachate reactors. Greater THB growth was observed in the treatment FBR, that had a high weekly dosage of 1.5 mL pure DEHP per L of leachate, than in the control FBR. This implies that some, if not all, of landfill leachate bacteria in the treatment FBR were able to metabolize DEHP as an additional carbon source for their growth.

Fig. 2.

Growth trend of total heterotrophic bacteria (THB) in fed batch reactors (FBRs) with DEHP inoculation (treatment FBR) and without it (control FBR). Data are shown the average values with standard deviations (n=3).

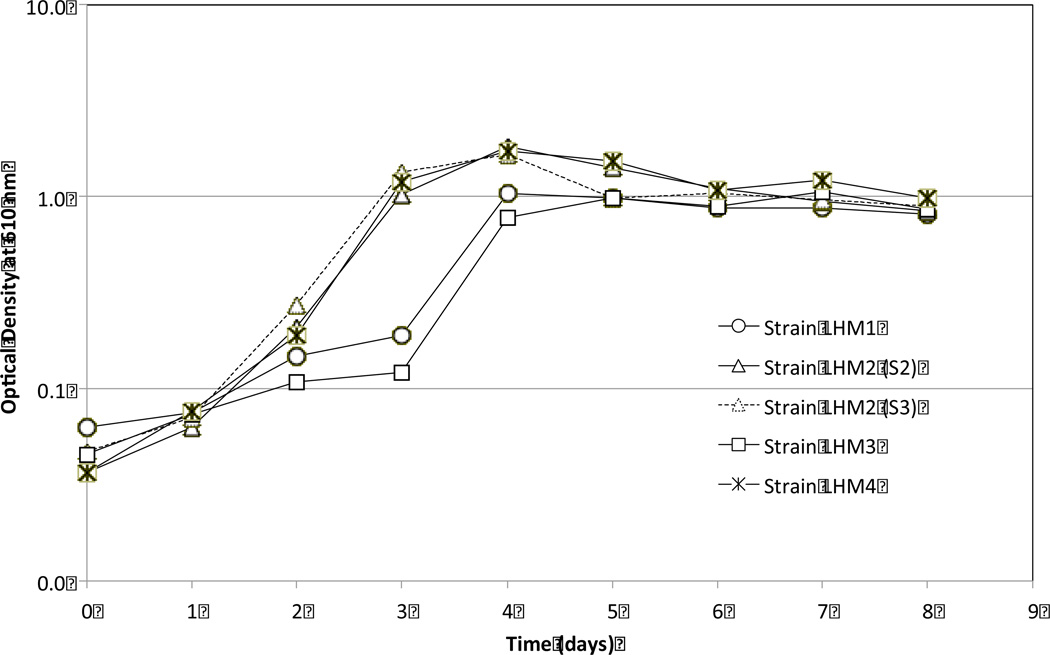

Enrichment of the Isolates Growing on DEHP as the Sole Carbon Source

As enriched with DEHP as the sole carbon source for >10 weeks in MSM, three isolates did not have a lag phase (Fig. 3). However, strains LHM2 and LHM4 grew faster reaching a maximum OD value of ~1.8 AU and entered stationary-growth phase after three days of incubation. In comparison, strains LHM1 and LHM3 reached a stationary-growth phase after four days of incubation and showed an OD value of ~0.9 AU. All strains reached to a stationary-growth phase at ~1.0 AU at the end of incubation.

Fig. 3.

Growth of Gram-positive strains LHM1 and LHM2 and Gram-negative strains LHM3 and LHM4 during the enrichment in a mineral salt medium with DEHP as the sole carbon source.

Based on the growth patterns on DEHP as the sole carbon source, it is construed that strains LHM2 and LHM4 metabolized more DEHP at a faster rate than the other two isolates, resulting in the growth decline at a later period of incubation due probably to nutrient limitation, quorum sensing, and/or production of toxic metabolites. [17,18]

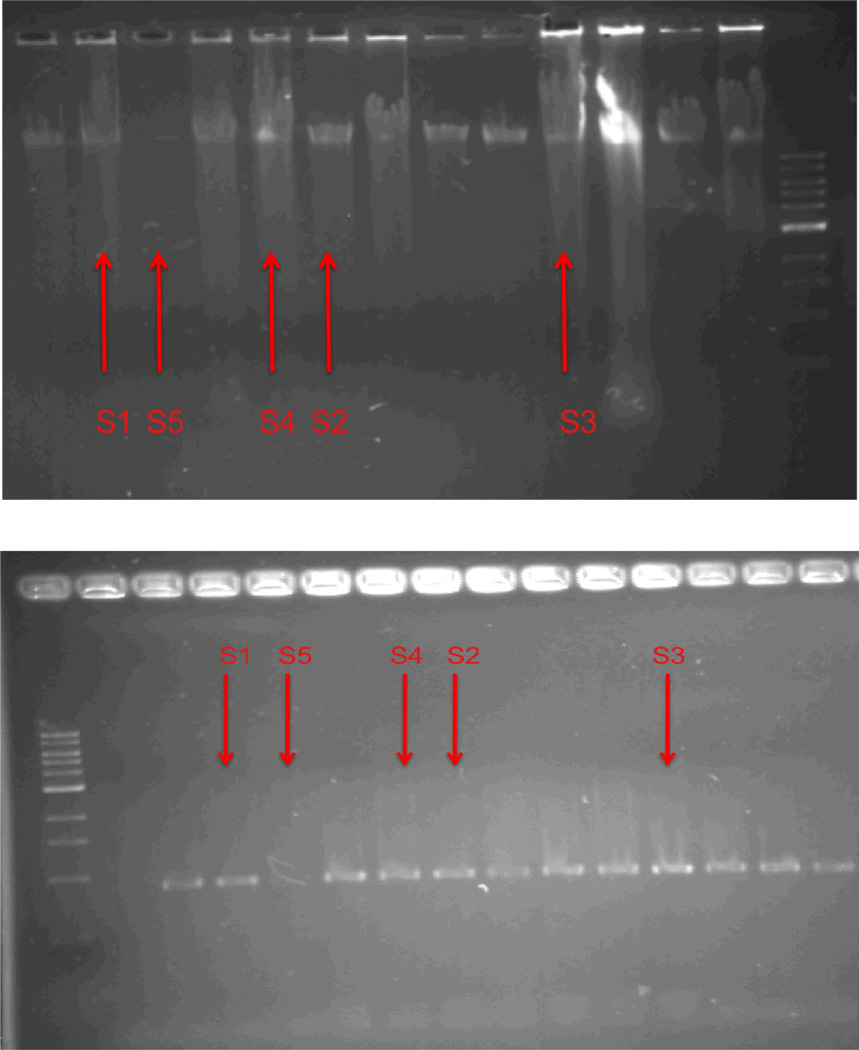

Identification of Enriched Bacteria Grown on DEHP as the Sole Carbon Source

Gel electrophoresis for genomic DNA extraction from the isolated strains was done with a weight greater than 10,000 bp. PCR product was also amplified for all strains with lower than 900 bp (Fig. 4). Morphological and molecular identification revealed that strains LHM1 and LHM2 were closely related to Gram-positive Chryseomicrobium sp. and Lysinibacillus sp., respectively. Gram-negative strains LHM3 and LHM4 were similar to Acinetobacter sp. and Stenotrophomonas sp., respectively.

Fig. 4.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of the extracted DNA (top) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification product (bottom). S1: strain LHM1, S2 and S3: strain LHM2, S4: strain LHM3, and S5: strain LHM4.

According to 16S rRNA gene sequence, strain LHM1 showed a 96.1 % of similarity on 519 F sequence and a 97.2 % of similarity on 1392 R sequence with Chryseomicrobium imtechense MW 10(T) (Table 2). The strain LHM1 was Gram-positive, rod-shaped, aerobic and yellow colored, circular and convex, and with an entire margin. Chryseomicrobium imtechense is a new member of the family Planococcaceae. [19] Gram-positive Chryseomicrobium sp. has never been reported for their growth on or biodegradation of environmental contaminants, to the authors’ knowledge.

Table 2.

Identification results by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis with Ez Taxon.

| Strains | Accession No. |

Identification | Similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LHM1 | GQ927308 | Chryseomicrobium imtechense MW 10(T) | 97.176 |

| LHM2 (S2) | AB271743 | Lysinibacillus fusiformis NBRC 15717(T) | 98.318 |

| LHM2 (S3) | AB271743 | Lysinibacillus fusiformis NBRC 15717(T) | 97.319 |

| LHM3 | X81661 | Acinetobacter calcoaceticus DSM 30006(T) | 90.673 |

| LHM4 | FJ748683 | Stenotrophomonas pavanii ICB 89(T) | 96.041 |

Two isolates of strain LHM2 (S2 and S3) showed the highest similarity greater than 97 % with Lysinibacillus fusiformis NBRC 15717(T) (Table 2). This is the first documentation of these bacteria, especially Gram-positive strains LHM1 and LHM2, capable of growing on DEHP as the sole carbon source. They were Gram-positive, aerobic and rod-shaped, but with different colors in the same culture medium, creamy-yellowish (S2) and orange (S3). This made us to believe that they were two different species. Creamy-yellowish colonies grown on TS agar plates were irregular shaped, flat and with lobate margins, whereas orange colonies were circular, raised and with entire margins.

Lysinibacillus genera were used to be part of the genus Bacillus, but recently they were separated as a new genus basically for differences in the composition of the peptidoglycan cell wall. [20] Five species compose this genus: Lysinibacillus fusiformis, Lysinibacillus sphaericus, Lysinibacillus parviboronicapiens, Lysinibacillus xylanilyticus and Lysinibacillus boronitolerans. Lysinibacillus are ubiquitous in soil, are able to survive under harsh environments, and is capable of metabolizing various environmental contaminants. For example, Wu et al. [21] reported biodegradation of dichloromethane (a halogenated solvent) by Lysinibacillus sp.. However, no research has been reported for Lysinibacillus sp. as DEHP-degraders.

Strains LHM3 and LHM4 showed a 90.7% and 96.0% similarity with the genus Acinetobacter and Stenotrophomonas, respectively (Table 2). Strain LHM3 was a Gram-negative, aerobic, irregular shaped, flat, with undulated margins and rods and coccus shaped. Creamy colonies of strain LHM4 were Gram-negative, aerobic, irregular shaped and flat with lobate margins.

Acinetonacter sp. and Stenotrophomonas sp. have been reported for their capability of degradation of environmental contaminants, but not of DEHP. For example, hydrolysis of fenamiphos (an organophosphate nematicide) was studied with Acinetobacter rhizosphaaerae which was isolated from banana plantation soil. [22] Stenotrophomonas sp. was assessed as bioremediation potential for the sites contaminated with petrochemicals. [23]

Phylogenetic analysis was conducted to corroborate the results of the molecular identification of the strains LHM1 and LHM2 that had shown the highest similarities of 97.2% and 98.3% to Chryseomicrobium imtechense MW 10(T) and Lysinibacillus fusiformis NBRC 15717(T), respectively. Figure 5 illustrates that strains LHM1 and strain LHM2 are closely related to Chryseomicrobium imtechense MW 10(T) with a bootstrap value of 99% and Lysinibacillus fusiformis NBRC 15717(T) with a bootstrap value of 54%, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Neighbor-joining distance tree using the 16S rRNA gene sequences of strains LHM1 and LHM2 and closely related species. Bootstrap values higher than 35% are shown. Accession numbers are shown in the parenthesis. Pseudomonas aeruginosa LMG 1242T (Z76651) was used as the outgroup. The scale bar indicates 0.02 substitutions per nucleotide position.

Application of Strains LHM1 and LHM2 to DEHP-Containing PVC Shower Curtain

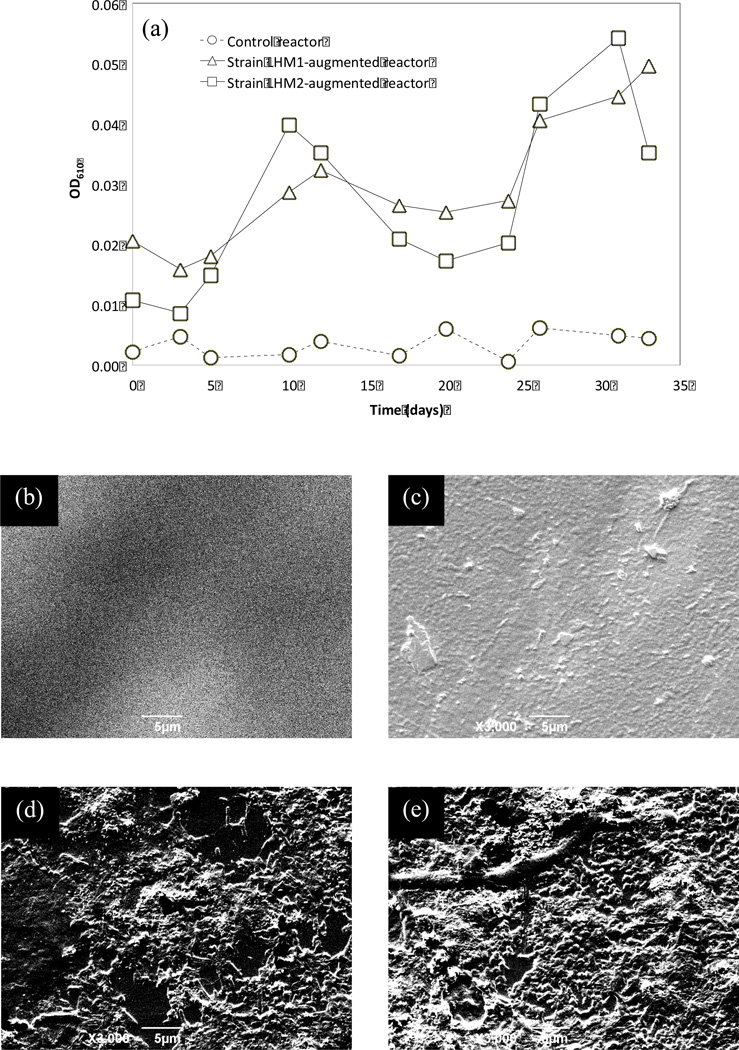

An increasing trend of OD was found in the solution phase of bioaugmented reactors with strains LHM1 and LHM2 (Fig. 6). Between two bioaugmented reactors, differences in the solution-phase OD were not observed. However, their OD values were substantially higher than those in the control reactor where an abiotic environment was maintained during the experiment.

Fig. 6.

Growths of strain LHM1 and LHM2 on PVC shower curtain (type 3). Optical densities at 610 nm are measured in the solution phase during the 34-day experiment and the results are shown in (a). Images of scanning electron microscope (x3,000) taken at the end of the 34-day experiment are shown: (b) virgin shower curtain 3, (c) shower curtain 3 from the control reactor, (d) shower curtain 3 from the reactor bioaugmented with strain LHM1, and (e) shower curtain 3 from the reactor bioaugmented with strain LHM2.

Images of SEM analysis also revealed higher density of attached growth on the shower curtains in the reactors bioaugmented with strain LHM1 and LHM2, compared to that in the control reactor. Microorganisms tend to develop biofilm (i.e., attached growth) under low substrate environments and this causes biodeterioration of the surfaces of polymeric materials. [24] BFM analysis showed pigmentation with dark brown pigment on the shower curtains in the reactors bioaugmented with the strains (date not shown) indicating the capability of the strain LHM1 and LHM 2 to produce extracellular enzyme for metabolic degradation [25] of DEHP-containing PVC shower curtains.

CONCLUSIONS

Four strains LHM1, LHM2, LHM3 and LHM4 capable of using DEHP as the sole carbon source were isolated from landfill leachate and were identified via 16S rRNA gene sequence. Gram-positive strains LHM1 and LHM2 had a greater than 97% similarity with Chryseomicrobium imtechense MW 10(T) and Lysinibacillus fusiformis NBRC 15717(T), respectively. Gram-negative strains LHM3 and LHM4 were related to Acinetobacter calcoaceticus DSM 30006(T) (90.7% similarity) and Stenotrophomonas pavanii ICB 89(T) (96.0% similarity), respectively. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first documentation of these bacteria, especially Gram-positive strains LHM1 and LHM2, capable of growing on DEHP as the sole carbon source.

The isolated strains LHM1 and LHM2 showed increasing growth patterns, in terms of OD at 610 nm, in the reactors with DEHP-containing PVC shower curtains. Thicker biofilm development on the surface of the shower curtains was also observed with bioaugmentation with strain LHM1 and LHM2. Therefore, these newly isolated, not previously reported, strains LHM1 and LHM2 grown on DEHP as the sole carbon source may significantly contribute to the fate, transport, remediation of DEHP in landfill settings. Further study is, however, warranted to elucidate the degradation pathways by the isolated strains and their gene expressions to corroborate the findings of the current study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The project described was supported by Award Number P42ES017198 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. We also wish to acknowledge the support provided by the Puerto Rico Institute for Functional Nanomaterials under the National Science Foundation Award Number EPS-1002410. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the National Institutes of Health, or the National Science Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Staples CA, Peterson DR, Parkerton TF, Adams WJ. The environmental fate of phthalate esters: A literature review. Chemosphere. 1997;35:667–749. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patil NK, Veeranagouda V, Vijaykumar M, Nayak SA, Karegoudar T. Enhanced and potential degradation of o-phthalate by Bacillus sp. immobilized cells in alginate and polyurethane. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2006;57:82–87. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shelton DR, Boyd SA, Tiedje AM. Anaerobic biodegradation of phthalic acid esters in sludge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1984;1904:93–97. doi: 10.1021/es00120a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chao W, Cheng C. Effect of introduced phthalate-degrading bacteria on the diversity of indigenous bacterial communities during di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) degradation in a soil microcosm. Chemosphere. 2007;67:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver R, May E, Williams J. Microcosm investigation of phthalate behavior in sewage treatment biofilms. Sci. Total Environ. 2007;372:605–614. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang B, Liao C, Yuan S. Anaerobic degradation of diethyl phthalate, di-n-butyl phthalate, and di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate from river sediment in Taiwan. Chemosphere. 2005;58:1601–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakamiya K, Hashimoto S, Ito H, Edmonds JS, Yasuhara A, Morita M. Microbial treatment of bis (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in polyvinyl chloride with isolated bacteria. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2005;99:115–119. doi: 10.1263/jbb.99.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng F, Cui K, Li X, Fu J, Sheng G. Biodegradation kinetics of phthalate esters by Pseudomonas fluoresences FS1. Process Biochem. 2004;39:1125–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang CR, Yao J, Zheng YG, Jiang CJ, Hu LF, Wu YY. Dibutyl phthalate degradation by Enterobacter sp. T5 isolated from municipal solid waste in landfill bioreactor. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2010;64:442–446. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner V, Rawling M. The behavior of di- 2-ethylhexyl phthalate in estuaries. Mar. Chem. 2000;68:203–217. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voss C, Zerban H, Bannasch P, Berger MR. Lifelong exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl)-phthalate induces tumors in liver and testes of Sprague–Dawley rats. Toxicology. 2005;206:359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okeke BC, Frankenburger WT., Jr Biodegradation of methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE) by a bacterial enrichment consortia and its monoculture isolates. Mirobiol. Res. 2003;158:99–106. doi: 10.1078/0944-5013-00181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rediers H, Vanderleyden J, De Mot R. Nitrate respiration in Pseudomonas stutzeri A15 and its involvement in rice and wheat root colonization. Microbiol Res. 2009;164:461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harley JP, Prescott L. Laboratory Exercises in Microbiology. Fourth Edition. McGraw-Hill; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Medina F, Vinson SB, Coates CJ. Isolation, characterization, and molecular identification of bacteria from the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) midgut. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2005;89:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pepe O, Sannino L, Palomba S, Anastasio M, Blaiotta G, Villani F, Moschetti G. Heterotrophic microorganisms in deteriorated medieval wall paintings in southern Italian churches. Microbiol Res. 2010;165:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carbonell X, Corchero JL, Cubarsi R, Vila P, Villaverde A. Control of Escherichia coli growth rate through cell density. Microbiol Res. 2002;157:257–265. doi: 10.1078/0944-5013-00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srivastava VC, Manderson GJ, Bhamidimarri R. Injibitory metabolites production by the cyanobacterium Fischerella muscicola. Microbiol Res. 1999;153:309–317. doi: 10.1016/S0944-5013(99)80043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arora PK, Chauhan A, Pant B, Korpole S, Mayilraj S, Jain RK. Chryseomicrobium imtechense gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the family Planococcaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011;61:1859–1864. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.023184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed I, Yokota A, Yamazoe A, Fujiwara T. Proposal of Lysinibacillus boronitolerans gen. nov., sp., nov., and transfer of Bacillus fusiformis to Lysinibacillus fusiformis comb. nov. and Bacillus sphaericus to Lysinibacillus sphaericus comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007;57:1117–1125. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63867-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu SJ, Hu ZH, Zhang LL, Yu X, Chen JM. A novel dichloromethane-degrading Lysinibacillus sphaericus strain wh22 and its degradative plasmid. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;82:731–740. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1873-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chanika E, Georgiadou D, Soueref E, Karas P, Karanasios E, Tsiropoulos NG, Tzortzakakis EA, Karpouzas DG. Isolation of soil bacteria able to hydrolyze both organophosphate and carbamate pesticides. Bioresource Technol. 2011;102:3184–3192. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.10.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verma V, Raju SC, Kapley A, Kalia VC, Kanade GS, Daginawala HF, Purohit HJ. Degradative potential of Stenotrophomonas strain HPC383 having genes homologous to dmp operon. Bioresource Technol. 2011;102:3227–3233. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flemming H-C. Relevance of biofilms for the biodeterioration of surfaces of polymeric materials. Polym. Degra. Stab. 1998;59:309–315. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan L, Gu J-G, Yin B, Cheng S-P. Contribution to deterioration of polymeric materials by a slow-growing bacterium Nocardia corynebacterioides. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2009;63:24–29. [Google Scholar]