Abstract

African-American and White youth (N = 405) were assessed annually for 8 years, providing data from ages 9–20 years. Alcohol use increased with age, as did binge drinking, drunkenness, peer alcohol use, and ease of attaining alcohol. At younger ages, the usual alcoholic drink was wine; other drinks were preferred at older ages. Fewer African Americans compared to Whites reported alcohol use, binge drinking, drunkenness, peer alcohol use, and encouragement of alcohol. These results support and extend previous findings, and suggest that contextual influences may help explain alcohol use differences and similarities between African-American and White youth.

Keywords: African American, Ethnicity, Youth, Alcohol Use, Descriptive

Early initiation of alcohol use is one of the strongest predictors of late adolescent and young adult alcohol abuse and alcohol-related problems, including school or work-related problems, absenteeism, drinking and driving, injuries and accidents, homicides and sexually transmitted diseases, and poor social and coping skills (Brook, Whiteman, Gordon, & Cohen, 1996; DeWitt, Adlaf, Offord, & Ogborne, 2000; Gillmore, Butler, Lohr, & Gilchrist, 1991; Gruber, DiClemente, Anderson, & Lodico, 1996; Peterson, Hawkins, Abbott, & Catalano, 1994; Wechsler et al., 2002). To accurately document patterns and trends in alcohol consumption throughout childhood and adolescence, and to assess changes in alcohol use throughout this developmental period, it is important to conduct longitudinal studies in which the same respondents are followed over time (Bahr, Marcos, & Maughan, 1995; Barnes, Reifman, Farrell, & Dintcheff, 2000).

Relatively few studies have examined the etiology of alcohol use among minority youth and adolescents. Typically, studies find that White adolescents report greater alcohol use than African Americans (Bryan & Stallings, 2003; Forney, Forney, & Ripley, 1991; Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 1987). For example, the National Household Survey of Drug Abuse (NHSDA; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003) reported that alcohol use in the past 30 days for youth ages 12–17 was 18% for Whites and 10.9% for African Americans. In addition, early initiation of alcohol has been found to be more prevalent among White than African American youth (e.g., Johnston et al., 1987; Newcomb & Bentler, 1986), yet African Americans exhibit a disproportionate number of adverse effects related to alcohol use, such as depression, violence, and suicide (Nasim, Belgrave, Jagers, Wilson, & Owens, 2007). Other studies have not found significant differences between the alcohol use of African-American and White youth (Bray, Adams, Getz, & Baer, 2001; Dolcini & Adler, 1994), suggesting that more research is needed to provide information on patterns of alcohol use among these ethnic groups.

There is a lack of recent data on alcohol use and related variables among African-American and White youth. To remain current on patterns and trends in youth alcohol use, and to use such data to inform future research and program development, it is important to disseminate data in a timely manner. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to present descriptive alcohol use data of African-American and White youth from a recent study in the Pacific Northwest. Results presented are from a longitudinal study (the “Adolescents, Families, & Neighborhoods Project”) in which target youth and their families were randomly recruited and assessed annually for 8 consecutive years from 1999–2007. Target children were initially recruited from three cohorts (9, 11, and 13 years of age), resulting in data collection from ages 9–20 by the end of the project. Relatively equal numbers of African-American and White male and female target children from the three age cohorts were recruited, allowing examination of data across ethnicity and gender.

The purpose of this manuscript is to present and discuss a picture of alcohol use at ages 9–20 across African Americans and Whites, focusing specifically on those alcohol use variables the authors believe to be of key interest.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data were collected across 8 years (1999–2007) from residents of a large metropolitan area in the Northwest. The sample comprised 405 youth and their families. Youth were 48.4% female, 50.4% African American, and 49.6% White. Families were randomly recruited via telephone using a computer-assisted telephone interviewing system. A total of 72,412 cold calls were made over 12.5 months, of which 45.5% resulted in contact; 1.3% were eligible and 75% of those eligible agreed to participate. Target youth were recruited approximately equally from three age cohorts (9-, 11-, and 13-year-old cohorts), across gender (male and female), and ethnicity (African American and White). More detailed recruitment information is presented in Duncan, Strycker, Duncan, He, and Stark (2002).

In addition to the target child, all family members aged 9 years or older were invited to participate. All assessments took place in the participants’ homes. Family members completed annual surveys under the supervision and guidance of research assistants. In the first year, families were paid $100 for completing the assessment with a $20 bonus if all eligible family members participated. Each participating child also was paid $5. Family payments were increased by $10 in each subsequent assessment year. Yearly attrition from T1 to T8 was 2.7%, 1.3%, 3.6%, 5.6%, 6%, 8%, and 3.9%, respectively. Overall attrition from T1 to T8 was 27%.

Measures

All of the following measures were included in each year of the study (T1–T8) unless otherwise specified.

Ever used alcohol

Youth were asked, “Have you ever used alcohol of any kind (such as beer, wine, wine coolers, or hard liquor such as scotch, whiskey, rum, gin, or vodka)?” The percentage of those answering “yes” is reported.

Current alcohol use

Questions were asked separately for beer, wine/wine coolers, and hard liquor, “How often do you drink [beer/wine/liquor] now?” Responses ranged from 1 = don’t use at all to 8 = use 2–3 times per day or more. The variables were dichotomized so that 0 = no current use and 1 = current use.

Binge drinking/Drunkenness

Binge drinking was assessed by asking participants how many times in the past year they had five or more drinks of alcohol at one time or in one day. Responses ranged from 1 = never to 5 = more than three times, and were recoded such that 0 = no binge drinking and 1 = at least one episode of binge drinking. Participants also reported how many times in the past year they had used alcohol to the point of being drunk, and responses were recoded for analysis, to 0 = no times and 1 = one or more times.

Usual alcoholic drink

Youth who had used alcohol were asked, “When you use alcohol, what do you usually drink?” Responses included beer, malt liquor, wine or wine cooler, fortified wine, hard liquor, and “it varies.”

Alcohol purchases

Those who had used alcohol were asked if they had tried to purchase alcohol in a store in the past year. If they responded “yes,” they were then asked what happened when they tried to purchase. Possible responses were 1 = I was refused all of the time, 2 = I was refused most of the time, 3 = I was refused some of the time, and 4 = I was able to buy every time.

Peer use, encouragement, and offering of alcohol

To assess peer alcohol use, youth were asked, “How often in the past year did your friends drink alcohol?” Responses ranged from 1 = friends don’t use at all to 8 = friends use 2–3 times per day or more. Peer encouragement of alcohol use was measured via a single self-report item, “Do your friends generally encourage or discourage your use of alcohol?” Responses were on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = strongly discourage to 5 = strongly encourage. To assess the extent of friends offering alcohol, youth were asked, “In the past year, how many of your friends have offered you alcohol?” Responses ranged from 0 to 5 or more friends. All variables were dichotomized for analysis to indicate the lack or presence of alcohol use, encouragement, and offers.

Alcohol use norms among school peers

Youth were asked, “How many of the kids at your school do you think drink beer/wine/liquor?” Responses were on a five-point scale from 1 = very few to 5 = almost all. Responses were dichotomized for analysis (0 = very few to some kids and 1 = about half or more kids).

Neighborhood alcohol

Two questions asked how much respondents agreed or disagreed that the following were a problem in their neighborhood: (a) alcohol use among kids and (b) alcohol use among adults. Responses ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. In addition, youth were asked how easy it would be for them to get alcohol in their neighborhood, with responses ranging from 1 = not at all easy to 5 = extremely easy. Responses were dichotomized to reflect absence vs. presence of neighborhood alcohol problems, and ease vs. difficulty of attaining alcohol.

Drinking and driving

At later time points in the study, older youth were asked questions relating to drinking and driving. These questions included how often they drink and drive, if they have been charged with driving while intoxicated ever and in the past year, and if they had ever had their driver’s license suspended for driving while intoxicated.

Results

Table 1 summarizes study participants across age cohort, ethnicity, and gender.

Table 1.

Age, Sex, and Race of the Youth Sample at T1

| Cohort | African American, N = 203 (107 boys, 96 girls) N |

White, N = 202 (104 boys, 98 girls) N |

|---|---|---|

| 9-year-olds | 70 | 70 |

| Boys | 40 | 37 |

| Girls | 30 | 33 |

| 11-year-olds | 69 | 70 |

| Boys | 32 | 36 |

| Girls | 37 | 34 |

| 13-year-olds | 64 | 62 |

| Boys | 35 | 31 |

| Girls | 29 | 31 |

Note: Total N = 405; 211 boys and 194 girls

Ever used alcohol

Reported alcohol use increased in the overall sample across the 9–20 age span; 13% said they had used alcohol at age 9 compared to 76% at age 20 (see Table 2). Significantly more White youth reported alcohol use than African-American youth (19% of Whites vs. 7% of African Americans at age 9 [Π2(1) = 4.49, p < .05]; 87% of Whites vs. 63% of African Americans at age 20 [Π2(1) = 6.93, p < .01]).

Table 2.

Alcohol Use and Binge Drinking/Drunkenness

| All | African American |

White | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Alcohol Use (% Ever Used) |

|||

| Age 9 | 13% | 7% | 19% |

| Age 14 | 26% | 19% | 32% |

| Age 20 | 76% | 63% | 87% |

|

Binge Drinking (% Yes) |

|||

| Age 9 | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Age 14 | 5% | 5% | 6% |

| Age 20 | 53% | 32% | 72% |

|

Drunkenness (% Yes) |

|||

| Age 9 | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Age 14 | 10% | 8% | 12% |

| Age 20 | 65% | 50% | 78% |

Current alcohol use

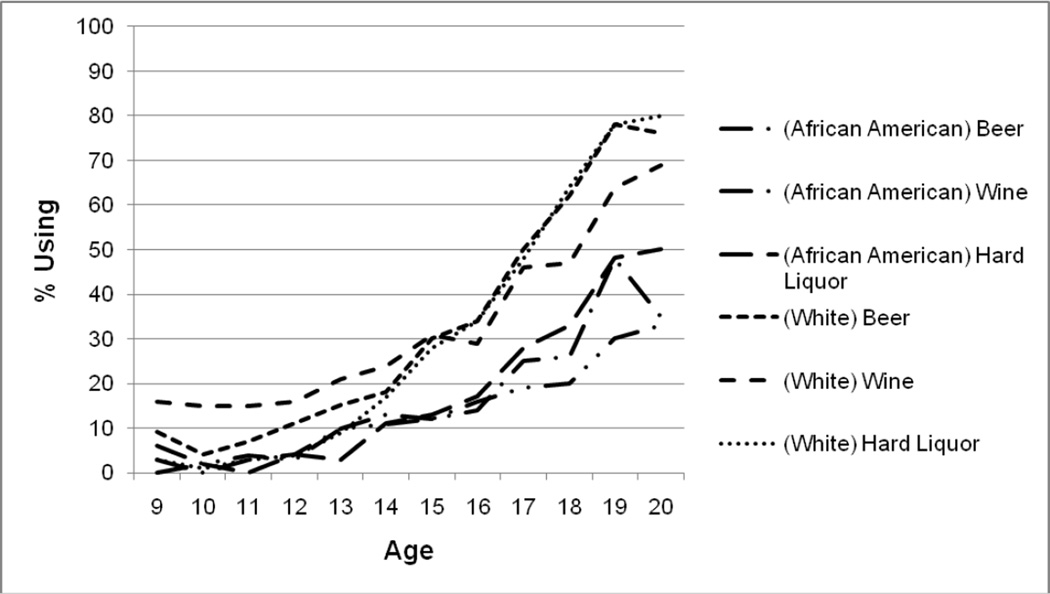

From ages 9–20, the percentage of youth in the overall sample reporting current use of beer, wine, and hard liquor steadily rose, from 6%, 11%, and 1% using these three substances, respectively, at age 9 to 56%, 52%, and 66% at age 20. Figure 1 presents current beer, wine, and hard liquor use as a function of age and race, illustrating this increasing pattern of use, as well as the widening gap in alcohol use between Whites and African Americans across the age span (87% of Whites vs. 63% of African Americans reported current use of at least one of these substances at age 20 [Π2(1) = 6.64, p < .01]).

Figure 1.

Percentage of youth reporting current beer, wine, and hard liquor use as a function of age and race (White vs. African American).

Binge drinking/Drunkenness

In the overall sample, binge drinking and drunkenness increased from ages 9–20, from 0% (age 9) to 53% (age 20) of youth reporting binge drinking (defined as having five or more drinks at one time or in one day) and from 0% (age 9) to 65% (age 20) of youth reporting being drunk in the past year (see Table 2). Results differed significantly by race, with greater percentages of Whites compared to African Americans reporting binge drinking (72% Whites vs. 32% African Americans, Π2(1) = 13.24, p < .001) and drunkenness (78% vs. 50%, Π2(1) = 7.52, p < .01) at age 20.

Usual alcoholic drink

Of youth in the overall sample who had used alcohol, wine was reported as the usual drink at younger ages, but preference for wine steadily declined across the 9–20 age span while preference for other alcoholic drinks held steady or increased (see Table 3). The percentage of alcohol users reporting wine as their usual drink averaged 55% from ages 9–14 and 18% from ages 15–20. Meanwhile, beer preference remained about the same (average 23% ages 9–14 vs. 24% ages 15–20), malt liquor preference increased slightly (average 0% ages 9–14 vs. 5% ages 15–20), hard liquor preference increased (average 11% ages 9–14 vs. 28% ages 15–20), and a preference for varied alcoholic drinks increased (average 10% ages 9–14 vs. 25% ages 15–20). Fortified wine use was rarely reported. Alcohol drink preference patterns did not differ significantly between White and African-American youth.

Table 3.

Usual Alcoholic Drink

| All N (%) |

African American N (%) |

White N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Beer | |||

| Age 9 | 3 (27%) | 1 (20%) | 2 (33%) |

| Age 14 | 19 (21%) | 8 (24%) | 11 (19%) |

| Age 20 | 17 (26%) | 4 (15%) | 13 (33%) |

| Wine | |||

| Age 9 | 7 (64%) | 4 (80%) | 3 (50%) |

| Age 14 | 36 (39%) | 9 (27%) | 27 (46%) |

| Age 20 | 9 (14%) | 3 (12%) | 3 (15%) |

|

Hard Liquor |

|||

| Age 9 | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (17%) |

| Age 14 | 14 (15%) | 9 (27%) | 5 (9%) |

| Age 20 | 21 (32%) | 11 (42%) | 10 (25%) |

|

Various Drinks |

|||

| Age 9 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Age 14 | 22 (24%) | 6 (18%) | 16 (27%) |

| Age 20 | 14 (21%) | 6 (23%) | 8 (20%) |

Alcohol purchases

In the overall sample, attempts to buy alcohol steadily increased from ages 9–20, from an average of less than 1% at ages 9–14 to an average of 14% at ages 15–20. About 30% of 20-year-old participants reported that they had tried to purchase alcohol; of these, 5% were refused most of the time, 5% were refused some of the time, and 90% were successful in purchasing alcohol every time they tried. These alcohol purchasing patterns did not differ significantly between Whites and African Americans.

Peer use, encouragement, and offering of alcohol

In the overall sample, the influence of friends increased gradually over the 9–20 age span (see Table 4). Less than 1% reported having friends who used alcohol at age 9, 33% at age 14, and 86% at age 20. Peer alcohol use significantly differed by race, with 96% of Whites and 75% of African Americans reporting friends that used alcohol at age 20 (Π2(1) = 7.60, p < .01). Friends increasingly encouraged alcohol use from ages 9–20. In the overall sample, fewer than 1% of 9-year-olds said their friends encouraged alcohol use compared to 29% of 20-year-olds. This trend of increasing encouragement differed by race: Among 20-year-olds, 41% of White youth and 15% of African-American youth reported having friends who encouraged them to use alcohol (Π2(1) = 7.18, p < .01). Similarly, peers increasingly offered alcohol from ages 9–20; offers rose steadily from 1% at age 9 to 24% at age 14 and 78% at age 20. Although White youth tended to receive more offers from friends than African-American youth (85% of Whites and 70% African Americans reported friends offering alcohol at age 20), the trend was nonsignificant.

Table 4.

Peer Use, Encouragement, and Offering of Alcohol

| All | African American |

White | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Peer Use of Alcohol (% Yes) |

|||

| Age 9 | <1% | 0% | 1% |

| Age 14 | 33% | 26% | 40% |

| Age 20 | 86% | 75% | 96% |

|

Peer Encouragement of Alcohol (% Yes) |

|||

| Age 9 | 1% | 0% | 1% |

| Age 14 | 4% | 26% | 40% |

| Age 20 | 86% | 75% | 96% |

|

Peer Offering of Alcohol (% Yes) |

|||

| Age 9 | 1% | 0% | 3% |

| Age 14 | 24% | 23% | 25% |

| Age 20 | 78% | 70% | 85% |

Alcohol use norms among school peers

In the overall sample, youth reported increasing numbers of schoolmates drinking beer, wine, and hard liquor from ages 9–17. Beer, wine, and hard liquor use was low among 9-year-olds (only 1% said about half or more kids at school drink beer, wine, and hard liquor) compared to 17-year-olds (72% of youth said half or more kids at school drink beer, 54% said half or more kids drink wine, and 64% said half or more kids drink hard liquor). Alcohol use norms did not differ significantly between White and African-American youth.

Neighborhood alcohol

From ages 9–17 in the overall sample, perceptions of neighborhood problems related to youth and adult alcohol use remained fairly constant (see Table 5). About 22% of 9-year-olds and 22% of 17-year-olds thought youth alcohol use was a neighborhood problem, and 29% of 9-year-olds and 25% of 17-year-olds thought adult alcohol use was a neighborhood problem. African Americans and Whites did not differ significantly in their perceptions of youth alcohol-use problems in the neighborhood. However, African-American youth perceived significantly greater problems with adult alcohol use in their neighborhoods than White youth across the age span (37% of 9-year-old and 31% 17-year-old African Americans perceived adult alcohol problems vs. 21% of 9-year-old and 19% of 17-year-old Whites [(Π2(1) = 4.09, p < .05]). As they aged, youth increasingly believed that alcohol was easy to attain in the neighborhood (15% of 9-year-olds vs. 52% of 17-year-olds thought it was easy to get alcohol); results did not differ significantly by ethnicity.

Table 5.

Neighborhood Alcohol

| All | African American |

White | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Youth Alcohol Use Problems (% Yes) |

|||

| Age 9 | 22% | 24% | 19% |

| Age 14 | 13% | 15% | 12% |

| Age 17 | 22% | 24% | 19% |

|

Adult Alcohol Use Problems (% Yes) |

|||

| Age 9 | 29% | 37% | 21% |

| Age 14 | 23% | 32% | 14% |

| Age 17 | 25% | 31% | 19% |

|

Easy to Get Alcohol (% Yes) |

|||

| Age 9 | 15% | 10% | 20% |

| Age 14 | 39% | 33% | 44% |

| Age 17 | 52% | 52% | 53% |

Drinking and driving

In the overall sample at the last time point (T8), 79 participants (56 White and 23 African American) reported that they drove. Of those, seven participants (8.9%; 4 White; 3 African American) reported drinking and driving in the past year. At no time point did any participants report being charged or having their licenses suspended for drunk driving.

Discussion

Understanding the development of alcohol use across adolescence for both African-American and White youth is important for interventions aimed at reducing alcohol and other substance use. A key limitation of the prevention literature has been the paucity of research that examines the extent to which substance use findings in studies of White adolescents generalize to African American and other non-White youth (Wallace & Muroff, 2002).

Results of the present longitudinal study of African-American and White youth document increasing use of alcohol from ages 9–20, as well as changing preferences in alcoholic drinks, binge drinking and drunkenness, alcohol purchasing, peer norms, encouragement and offers of alcohol from friends, neighborhood alcohol problems and access, and drinking and driving. Many of the results differed by ethnic group, indicating that alcohol use is more common among Whites than African Americans. By the age of 20, most youth in the present study reported that they had used alcohol (about 87% of Whites and about 63% of African Americans). By the age of 13, 16% of African Americans in this study had tried alcohol, similar to the 10% of African-American 13-year-olds that had used alcohol according to NHSDA (2003) and somewhat less than the 26.1% reported in Nasim, Belgrave, Jagers, Wilson, & Owens (2007) in an at-risk sample. As youth in both ethnic groups aged in the current study, their usual drink was less apt to be wine and more often beer, hard liquor, and varied drinks. Binge drinking and drunkenness became more common at later ages, with significantly more of these behaviors occurring in Whites compared to African Americans. Alcohol purchasing also increased over the age span in both ethnic groups.

Differences and similarities between ethnic groups may vary according to family, peer, and neighborhood influences. For example, Peterson et al. (1994) found that family experiences of African-American adolescents may help to protect them from the risk of early initiation when compared to their White counterparts. Family contextual variables may thus help explain the lower levels of alcohol use among African American youth in this study compared to Whites. Gillmore et al. (1990) and Ringwalt and Palmer (1990) suggested that African-American adolescents are less susceptible to peer influence than White youth, a finding supported by the present study. Peers of White youth in this study tended to use more alcohol, to encourage alcohol use, and to offer alcohol to a greater degree than African-American youth. However, Whites and African Americans did not differ significantly in their perceptions of alcohol use norms among school peers, likely because they attended the same, integrated schools. Gottfredson and Koper (1996) argue for research that includes broader culturally significant contextual factors, such as neighborhood problems and the availability of substances, to understand the influences on alcohol use for different ethnic groups. Broader community influences (e.g., neighborhood climate, drug availability) have been found to significantly influence alcohol, other substance use, and related problems across ethnicities (Brook et al., 2001; Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker, 2002). The present study offers evidence that the neighborhood is an important influence for alcohol use among both African-American and White youth, who increasingly perceived that alcohol was easy to access in their neighborhoods.

Future research is needed to analyze the predictors and consequences of alcohol use in African-American and White youth, contextual influences of alcohol use (e.g., family, peer, neighborhood), and the relationship of alcohol to other substances and problem behaviors across both ethnicities from pre- through late adolescence.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by Grant AA11510 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and Grant DA018760 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Contributor Information

Susan C. Duncan, Email: sued@ori.org.

Lisa A. Strycker, Email: lisas@ori.org.

Terry E. Duncan, Email: terryd@ori.org.

References

- Bahr SJ, Marcos AC, Maughan SL. Family, educational and peer influences on the alcohol use of female and male adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:457–469. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Reifman AS, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. The effects of parenting on the development of adolescent alcohol misuse: A six-wave latent growth model. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Bray JH, Adams GJ, Getz JG, McQueen A. Individuation, peers, and adolescent alcohol use: A latent growth analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:553–564. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Gordon AS, Cohen P. Dynamics of childhood and adolescent personality traits and adolescent drug use. Developmental Psychology. 1996;22:403–414. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Brook DW, De La Rosa M, Whiteman M, Johnson E, Montoya I. Adolescent illegal drug use: The impact of personality, family, and environmental factors. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;24:183–203. doi: 10.1023/a:1010714715534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A, Stallings MC. A case control study of adolescent risky sexual behavior and its relationship to personality dimensions, conduct disorder, and substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2003;31:387–396. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: A risk factor for the development of alcohol disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:745–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcini MM, Adler NE. Perceived competencies, peer group affiliation, and risk behavior among early adolescents. Health Psychology. 1994;13:496–506. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.6.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Strycker LA. A multilevel analysis of neighborhood context and youth alcohol and drug problems. Prevention Science. 2002;3:125–134. doi: 10.1023/a:1015483317310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Strycker LA, Duncan TE, He H, Stark MJ. Telephone recruitment of a random stratified African American and White family study sample. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2002;1:57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Forney MA, Forney PD, Ripley WK. Alcohol use among Black adolescents: Parental and peer influences. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1991;36:36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore MR, Catalano RF, Morrison DM, Wells EA, Iritani B, Hawkins JD. Racial differences in acceptability and availability of drugs and early initiation of substance use. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16:185–205. doi: 10.3109/00952999009001583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore MR, Butler S, Lohr MJ, Gilchrist L. Substance use and other factors associated with risky sexual behavior in a sample of pregnant adolescents. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, School of Social Work; 1991. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Koper CS. Race and sex differences in the prediction of drug use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:305–313. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber E, DiClemente RJ, Anderson MM, Lodico M. Early drinking onset and its association with alcohol use and problem behavior in late adolescence. Preventive Medicine. 1996;25:293–300. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1987. National trends in drug use and related factors among American high school students and young adults, 1975–1986. DHHS Pub. No. ADM 87-1535. [Google Scholar]

- Nasim A, Belgrave FZ, Jagers RJ, Wilson KD, Owens K. The moderating effects of culture on peer deviance and alcohol use among high-risk African-American adolescents. Journal of Drug Education. 2007;37:335–363. doi: 10.2190/DE.37.3.g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Household Survey of Drug Abuse (NHSDA) The NHSDA Report from the Office of Applied Studies Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSHA) 2003

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Drug use, educational aspirations, and work force involvement: The transition from adolescence to young adulthood. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1986;14:303–321. doi: 10.1007/BF00911177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PL, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Disentangling the effects of parental drinking, family management, and parental alcohol norms on current drinking by Black and White adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1994;4:203–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ringwalt CL, Palmer JH. Differences between White and Black youth who drink heavily. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:455–460. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90032-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Muroff JR. Preventing substance abuse among African American children and youth: Race differences in risk factor exposure and vulnerability. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2002;22:235–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]