Crotamine from C. durissus terrificus was crystallized and diffraction data were collected to a resolution of 1.9 Å.

Keywords: crotamine, myotoxins, Crotalus durissus terrificus

Abstract

Crotamine, a highly basic myotoxic polypeptide (molecular mass 4881 Da) isolated from the venom of the Brazilian rattlesnake Crotalus durissus terrificus, causes skeletal muscle contraction and spasms, affects the functioning of voltage-sensitive sodium channels by inducing sodium influx and possesses antitumour activity, suggesting potential pharmaceutical applications. Crotamine was purified from C. durissus terrificus venom; the crystals diffracted to 1.9 Å resolution and belonged to the orthorhombic space group I212121 or I222, with unit-cell parameters a = 67.75, b = 74.4, c = 81.01 Å. The self-rotation function indicated that the asymmetric unit contained three molecules. However, structure determination by molecular replacement using NMR-determined coordinates was unsuccessful and a search for potential derivatives has been initiated.

1. Introduction

Crotamine induces spastic paralysis and myonecrosis (Katagiri et al., 1998 ▶), binding strongly to excitable membranes, and causes the contraction of skeletal muscle, resulting in rapid lysis of the sarcolemma, myofibril clumping and hypercontraction of sarcomeres (Matavel et al., 1998 ▶). This toxin induces skeletal muscle spasms (Oguiura et al., 2005 ▶) and interferes with the functioning of voltage-sensitive sodium channels of the skeletal muscle sarcolemma, leading to rapid sodium influx. Crotamine also causes depolarization and contraction of skeletal muscle attributed to the inhibition of voltage-gated potassium channels (Peigneur et al., 2012 ▶). More recently, it has been demonstrated that crotamine targets tumour tissue in vivo and triggers a lethal calcium-dependent pathway in cultured cells (Nascimento et al., 2011 ▶).

Crotamine (GenBank accession code P01475), a multifunctional small (molecular mass 4881 Da) and highly basic (pI = 10.3; Giglio, 1975 ▶) protein isolated from the venom of Crotalus durissus terrificus (Gonçalves & Polson, 1947 ▶; Laure, 1975 ▶), belongs to a class of closely related polypeptide myotoxins which are stabilized by three disulfide bridges. Crotamine is unglycosylated, rich in arginine and lysine residues (Boni-Mitake et al., 2001 ▶) and shares a relatively low sequence identity of 23% with human β-defensins. Multiple sequence alignments indicated partial conservation of the β-defensin fold (Schibli et al., 2002 ▶). The relatively highly positive potential surface charge allows us to hypothesize that it can interact electrostatically with the negative surface of membranes, causing local disruption and thereby inducing leakage of ions.

Relatively large and well diffracting crystals of crotamine have been obtained. However, exhaustive attempts to solve the crystal structure using models based on two independently determined NMR structures of crotamine (Nicastro et al., 2003 ▶; Fadel et al., 2005 ▶) have not been successful, probably owing to inherent flexibility or disorder. Thus, since neither the crystal structures nor the multimer interactions of these peptides have been determined, a search for suitable derivatives has been initiated.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Venom collection and purification

Since the content of crotamine present in the venom of C. durissus terrificus varies according to geographical location, crude venom was obtained from a number of different sources. The venom obtained from CEVAP, Botucatu, Brazil contained a significantly greater amount of crotamine (approximately 15% by weight). 150 mg desiccated crude venom was dissolved in 2 ml 0.05 M acetic acid pH 5 and centrifuged at 10 000g for 10 min. The clear supernatant was applied onto a Mono S HR 10/10 column (Amersham Biosciences; Fig. 1 ▶ a) previously equilibrated with the same buffer, the column was washed at a flow rate of 60 ml h−1 until the baseline stabilized and the bound fractions were eluted with the previously described solution additionally containing 1.0 M NaCl.

Figure 1.

(a) Purification of crotamine by cation-exchange chromatography (Mono S HR 10/10). Inset, Coomassie-stained 12% SDS–PAGE gel of crotamine. Lane M, molecular-mass markers (labelled in kDa); lanes 2–9, pooled purified crotamine at different concentrations. (b) Representative MALDI–TOF spectrum obtained from crotamine.

The purity of the protein was confirmed using SDS–PAGE gels (12%) as described by Laemmli (1970 ▶). Protein bands were visualized by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (Fig. 1 ▶ a, inset). Protein concentrations were determined by calculating the theoretical extinction coefficient and absorption was measured at 280 nm using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

The molecular mass was confirmed by mass spectroscopy (MALDI–TOF) on an UltrafleXtreme instrument (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) and the sequence of the first ten N-terminal amino acids was confirmed by Edman degradation (476A protein sequencer, Applied Biosystems; Fig. 1 ▶ b).

2.2. Crystallization

For crystallization experiments, crotamine was concentrated to 22 mg ml−1 in ultrapure water using microconcentrators (Amicon Ultra-4, Ultracel membrane). In situ dynamic light-scattering (DLS) measurements were carried out at 293 K at the same concentration using a SpectroLIGHT 500 system (Nabitek, Germany; Garcia-Caballero et al., 2011 ▶). DLS confirmed the presence of a single monodisperse population.

Crystallization conditions for crotamine were screened using the vapour-diffusion method (McPherson, 1999 ▶). A total of 384 crystallization conditions based on the commercially available JCSG+, ComPAS, Classics and Cryos Suites (NeXtal, Qiagen) were screened using a Honeybee 961 dispensing robot (Zinsser Analytic GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany) at 293 K in 96-well crystallization plates (NeXtal QIA1 µplates, Qiagen) using the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method. A 300 nl droplet of protein at approximately 10 mg ml−1 in buffer was mixed with the same volume of reservoir solution and equilibrated against 35 µl reservoir solution. The initial crystals obtained were relatively small; in order to increase their quality and size, they were reproduced manually using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method in Linbro 24-well plates. Diffraction-quality crystals with approximate dimensions of 0.5 × 0.25 × 0.1 mm were obtained after 2 d when a 1 µl protein droplet was mixed with an equal volume of reservoir solution consisting of 0.2 M sodium thiocyanate, 1.9 M ammonium sulfate pH 6.1 (Fig. 2 ▶).

Figure 2.

Native crystals of crotamine with approximate dimensions of 0.5 × 0.25 × 0.1 mm.

2.3. X-ray data collection

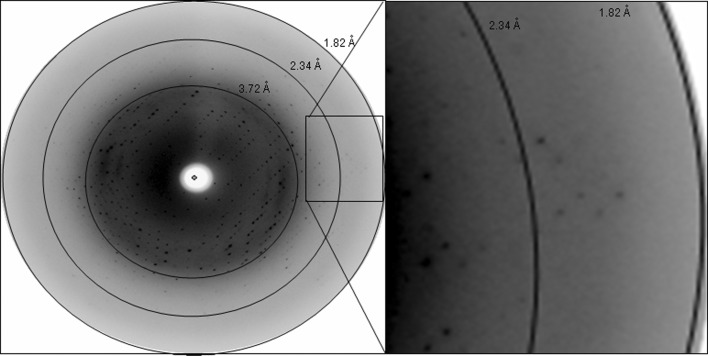

For diffraction data collection, a single crystal was flash-cooled after soaking it in reservoir solution that additionally contained 20% glycerol prior to data collection. X-ray diffraction data were collected on the X13 Consortium Beamline at DESY/HASYLAB. The wavelength of the radiation source was set to 0.8123 Å and a MAR CCD detector was used to record the X-ray diffraction intensities as 256 images with an oscillation range of 1° per image (Fig. 3 ▶). The raw intensities were indexed, integrated and scaled using the program MOSFLM (Leslie & Powell, 2007 ▶) from the CCP4 suite (Winn et al., 2011 ▶). Details of the data-collection and processing statistics are summarized in Table 1 ▶.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction pattern of crotamine: concentric rings indicate resolution ranges and the high-resolution diffraction pattern is magnified.

Table 1. Summary of data-collection and crystal parameters.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Radiation source | X13 Consortium Beamline, DESY/HASYLAB |

| Detector | MAR CCD |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.8123 |

| Space group | I222 or I212121 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = 67.75, b = 74.40, c = 81.01 |

| V M (Å3 Da−1) | 3.54 |

| Solvent content (%) | 65.2 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 18.7–1.9 (1.90–1.85) |

| Data completeness (%) | 94.8 (76.1) |

| R merge † (%) | 3.6 (48.9) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 34.7 (3.6) |

R

merge =

, where 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity of the observations I

i(hkl) of reflection hkl.

, where 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean intensity of the observations I

i(hkl) of reflection hkl.

3. Results and discussion

The molecular mass of the purified crotamine was determined to be 4881.70 Da and the presence of an isoform (with a molecular mass of 4736.58 Da) was observed (Fig. 1 ▶ b). The crotamine crystals (Fig. 2 ▶) diffracted X-rays to 1.8 Å resolution (Fig. 3 ▶). Processing of the diffraction data resulted in an R merge of 4.3% and a completeness of 97.05%. Examination of the systematic absences indicated that the crystals belonged to the enantiomorphic space groups I212121 or I222, with unit-cell parameters a = 67.75, b = 74.40, c = 81.01 Å. Based on the results of the self-rotation function, the Matthews coefficient (Matthews, 1968 ▶) was calculated to be 3.54 Å3 Da−1 assuming the presence of three molecules of crotamine in the asymmetric unit, which corresponds to a solvent content of 65.2%. Since both structure determination by molecular replacement using various models based on the independently determined NMR atomic coordinates (Nicastro et al., 2003 ▶; Fadel et al., 2005 ▶) with the program MOLREP (Vagin & Teplyakov, 2010 ▶) and attempts to use the anomalous sulfur signals were not successful, a search for suitable derivatives has been initiated.

Acknowledgments

This study was financed by grants from the DFG (Project BE 1443-18-1), FAPESP, CNPq, CAPES (80563/2911) and DAAD (PROBAL 50754442). DG thanks the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Bonn, Germany for providing a research fellowship (3.3-BUL/1073481 STP).

References

- Boni-Mitake, M., Costa, H., Spencer, P. J., Vassilieff, V. S. & Rogero, J. R. (2001). Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 34, 1531–1538. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fadel, V., Bettendorff, P., Herrmann, T., de Azevedo, W. F., Oliveira, E. B., Yamane, T. & Wüthrich, K. (2005). Toxicon, 46, 759–767. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Caballero, A. et al. (2011). Cryst. Growth Des. 11, 2112–2121.

- Giglio, J. R. (1975). Anal. Biochem. 69, 207–221. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, J. M. & Polson, A. (1947). Arch. Biochem. 13, 253–259. [PubMed]

- Katagiri, C., Ishikawa, H. H., Ohkura, M., Nakagawasai, O., Tadano, T., Kisara, K. & Ohizumi, Y. (1998). Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 76, 395–400. [PubMed]

- Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Nature (London), 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Laure, C. J. (1975). Hoppe Seylers Z. Physiol. Chem. 356, 213–215. [PubMed]

- Leslie, A. G. W. & Powell, H. R. (2007). Evolving Methods for Macromolecular Crystallography, edited by R. J. Read & J. L. Sussman, pp. 41–51. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Matavel, A. C., Ferreira-Alves, D. L., Beirão, P. S. & Cruz, J. S. (1998). Eur. J. Pharmacol. 348, 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McPherson, A. (1999). Crystallization of Biological Macromolecules New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Nascimento, F. D., Sancey, L., Pereira, A., Rome, C., Oliveira, V., Oliveira, E. B., Nader, H. B., Yamane, T., Kerkis, I., Tersariol, I. L. S., Coll, J.-L. & Hayashi, M. A. F. (2011). Mol. Pharm. 9, 211–221. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nicastro, G., Franzoni, L., de Chiara, C., Mancin, A. C., Giglio, J. R. & Spisni, A. (2003). Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 1969–1979. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oguiura, N., Boni-Mitake, M. & Rádis-Baptista, G. (2005). Toxicon, 46, 363–370. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Peigneur, S., Orts, D. J. B., Prieto da Silva, A. R., Oguiura, N., Boni-Mitake, M., de-Oliveira, E. B., Zaharenko, A. J., de-Freitas, J. C. & Tytgat, J. (2012). Mol. Pharmacol. 82, 90–96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schibli, D. J., Hunter, H. N., Aseyev, V., Starner, T. D., Wiencek, J. M., McCray, P. B., Tack, B. F. & Vogel, H. J. (2002). J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8279–8289. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vagin, A. & Teplyakov, A. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.