Uracil-DNA glycosylase from S. tokodaii strain 7 was overexpressed and purified. Crystals of the apo form and of a complex with uracil were obtained.

Keywords: family 4 uracil-DNA glycosylases, Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7

Abstract

Uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) specifically removes uracil from DNA by catalyzing hydrolysis of the N-glycosidic bond, thereby initiating the base-excision repair pathway. Although a number of UDG structures have been determined, the structure of archaeal UDG remains unknown. In this study, a deletion mutant of UDG isolated from Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7 (stoUDGΔ) and stoUDGΔ complexed with uracil were crystallized and analyzed by X-ray crystallography. The crystals were found to belong to the orthorhombic space group P212121, with unit-cell parameters a = 52.2, b = 52.3, c = 74.7 Å and a = 52.1, b = 52.2, c = 74.1 Å for apo stoUDGΔ and stoUDGΔ complexed with uracil, respectively.

1. Introduction

Spontaneous deamination of cytosine to uracil in DNA leads to a G·C to A·T transition mutation if the error is not repaired before the next round of replication. The rate of cytosine deamination is estimated at ∼70–200 events per human genome per day (Kavli et al., 2007 ▶). Uracil-DNA glycosylase (UDG) is a base-excision repair (BER) pathway enzyme that catalyzes the removal of uracil from DNA (Lindahl, 1974 ▶). Specifically, UDG catalyzes the hydrolysis of the N-glycosidic bond between uracil and the deoxyribose backbone, leaving an apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) site, which is repaired by downstream BER pathway enzymes (e.g. AP endonuclease, DNA polymerase and DNA ligase).

Uracil-DNA glycosylase is widely found in eukaryotes, bacteria, archaea and some DNA viruses. The UDG superfamily consists of six families of enzymes that are classified based on conserved motifs, structural similarities and substrate specificity (Pearl, 2000 ▶; Lee et al., 2011 ▶). The most efficient UDGs are found in family 1; these enzymes can remove uracil from both double-stranded and single-stranded DNA, regardless of whether the opposite base is a guanine or an adenine (Varshney et al., 1988 ▶). Family 2 UDGs exhibit greater sequence specificity, removing uracil only when uracil (or thymine) is paired with guanine (Gallinari & Jiricny, 1996 ▶; Yang et al., 2000 ▶). Family 3 UDGs were originally identified by their ability to remove uracil and 5-hydroxymethyluracil from single-stranded DNA (Haushalter et al., 1999 ▶). Family 4 and family 5 UDGs are found in thermophiles and possess four well conserved cysteine residues that are required to coordinate the 4Fe–4S cluster. In addition, family 4 UDGs are functionally similar to those of family 1 (Sartori et al., 2001 ▶), while family 5 UDGs have broad substrate specificity and a distinctive active-site motif that lacks polar amino-acid residues (Sartori et al., 2002 ▶). Family 6 represents a newly identified group of UDGs that exhibit hypoxanthine DNA glycosylase activity (Lee et al., 2011 ▶).

Crystal structures of UDGs isolated from various eukaryotes (Mol et al., 1995 ▶; Wibley et al., 2003 ▶; Leiros et al., 2003 ▶), bacteria (Ravishankar et al., 1998 ▶; Barrett et al., 1998 ▶; Hoseki et al., 2003 ▶; Leiros et al., 2005 ▶; Moe et al., 2006 ▶; Kosaka et al., 2007 ▶; Kaushal et al., 2008 ▶; Raeder et al., 2010 ▶) and viruses (Savva et al., 1995 ▶; Géoui et al., 2007 ▶; Schormann et al., 2007 ▶) have been reported and deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB entries 3tr7, 3cxm and 1vk2). The structure of UDGs generally consists of a three-layer α/β/α sandwich fold and a conserved Phe residue, which interacts with uracil by a π–π stacking interaction, located at the bottom of the active-site pocket. However, to date there have been no reports of a crystal structure of a UDG from an archaeon. In order to enhance understanding of the structural features of UDGs, we have studied the detailed structure and function of a family 4 UDG from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7 (stoUDG; its activity is shown in Supplementary Fig. 11). High temperature leads to an acceleration of the rate constant for spontaneous cytosine deamination (Lindahl & Nyberg, 1974 ▶). Moreover, it has been reported that the family B DNA polymerase found in hyperthermophilic archaea specifically recognizes uracil and hypoxanthine at the +4 position of the template strand (Fogg et al., 2002 ▶). When family B DNA polymerase captures a deaminated base, replication is aborted. These findings indicate that in hyperthermophilic archaea deaminated bases are strictly recognized as a risk factor for a transition mutation. A three-dimensional structural study of stoUDG would help to explain the mechanism of uracil-excision repair in hyperthermophilic archaea. Here, we report the successful crystallization and the preliminary X-ray crystallographic analysis of stoUDGΔ, which is a stoUDG deletion mutant that lacks the C-terminal region (Tyr194–Lys220) of the enzyme.

2. Methods

2.1. Protein expression and purification

The stoUDG expression vector constructed by inserting the STK_22380 gene (GenBank accession No. BAB67347) into the NdeI and BamHI restriction-enzyme sites of the pET-11a plasmid (Novagen) was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells. These cells produced recombinant stoUDG without any tags. Transformant cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.6 at 310 K in Luria–Bertani broth and 20%(w/v) lactose solution was then added to a final concentration of 1 mM. The cells were grown for an extra 4 h and then harvested by centrifugation (6500g for 20 min). The cells were resuspended in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 containing 1.5 M ammonium sulfate and disrupted by sonication. The disrupted cells were incubated at 343 K for 30 min and then centrifuged (15 000g for 1 h). The supernatant was applied onto a HiTrap Phe hydrophobic column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 containing 1.2 M ammonium sulfate, and stoUDG was eluted with 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 containing 0.4 M ammonium sulfate. The eluate containing stoUDG was dialyzed overnight against 1 l 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0. Further purification was performed on a HiTrap SP cation-exchange column (GE Healthcare), which was eluted with a linear gradient of 0–0.5 M NaCl in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0. Fractions exhibiting high absorbance at 330 and 280 nm (indicative of the presence of an iron–sulfur cluster) were collected, dialyzed twice against 1 l 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 and concentrated to 20 mg ml−1 for crystallization trials. The purity of the stoUDG used in this study was evaluated by SDS–PAGE.

2.2. Crystallization

2.2.1. Initial screening for crystallization

Initial crystallization screening of stoUDG, stoUDGΔ and stoUDGΔ complexed with uracil (stoUDGΔ–uracil) was performed by the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method using Index, Crystal Screen and Crystal Screen 2 kits (Hampton Research) at 293 K. stoUDGΔ–uracil was formed by incubating stoUDGΔ solution (40 mg ml−1) with an equal amount of 8 mM uracil solution at 277 K overnight. A 1.2 µl volume of protein solution was mixed with an equal volume of reservoir solution and the mixture was equilibrated against 0.1 ml aliquots of reservoir solution in a 96-well sitting-drop CrystalQuick plate (Greiner Bio-One).

2.2.2. stoUDGΔ crystallization

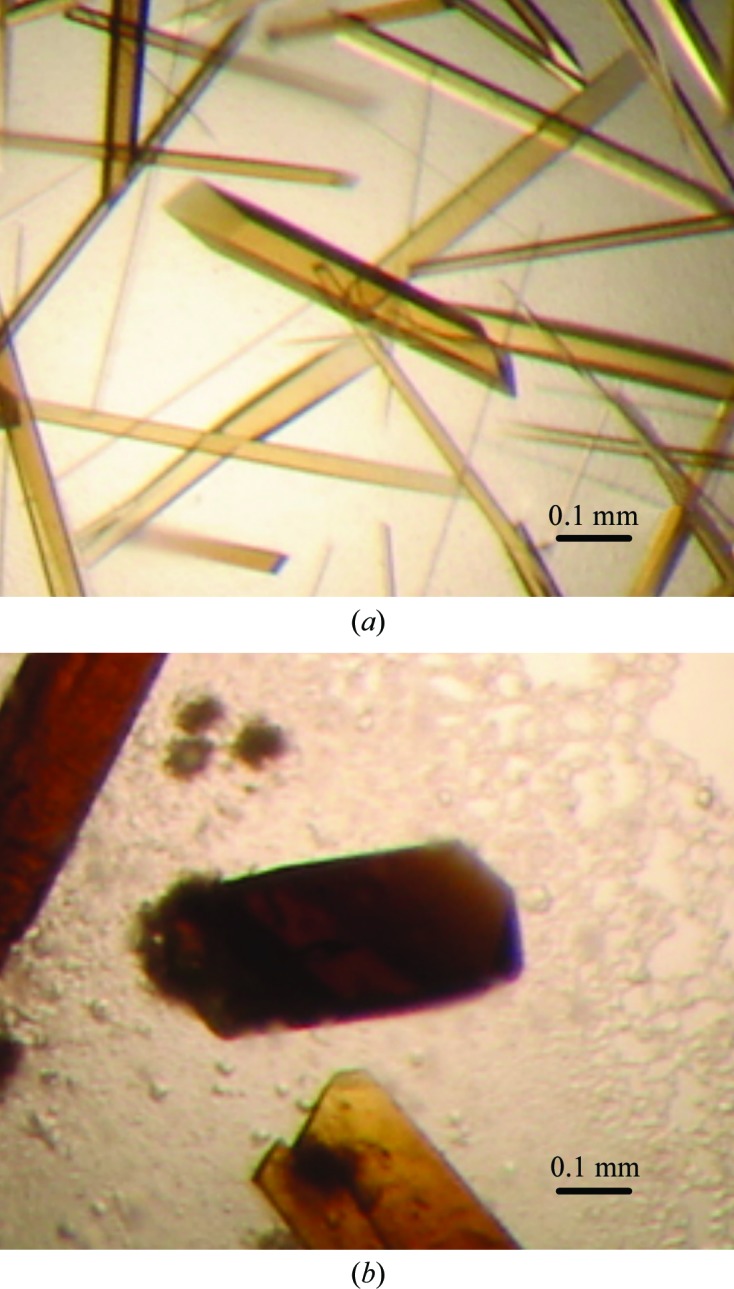

Crystallization of stoUDGΔ was performed by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method. The best crystals were obtained in 4–5 d at 293 K by mixing 2 µl stoUDGΔ solution (10 mg ml−1) with 2 µl reservoir solution consisting of 20%(w/v) PEG 3350, 0.1 M MES pH 5.8, 20%(v/v) glycerol (Fig. 1 ▶ a).

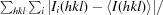

Figure 1.

Crystals of stoUDGΔ. (a) Crystal of stoUDGΔ with dimensions of 0.05 × 0.1 × 0.4 mm. (b) Crystal of stoUDGΔ–uracil with dimensions of 0.2 × 0.2 × 0.4 mm.

2.2.3. stoUDGΔ–uracil crystallization

Crystallization of stoUDGΔ–uracil was performed by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method. The best stoUDGΔ–uracil cocrystals were obtained in 1–2 weeks at 293 K by mixing 2 µl stoUDGΔ–uracil solution (10 mg ml−1 containing 2 mM uracil) with 2 µl reservoir solution consisting of 15%(w/v) PEG 3350, 0.1 M MES pH 5.8 (Fig. 1 ▶ b).

2.3. Data collection and processing

An stoUDGΔ crystal was flash-cooled directly in a nitrogen stream at 100 K. An stoUDGΔ–uracil cocrystal was transferred into a solution containing 30%(w/v) polyethylene glycol (PEG) 200 as a cryoprotectant and was then flash-cooled in a nitrogen stream at 100 K. Diffraction data sets for stoUDGΔ and stoUDGΔ–uracil were collected on a DIP-6040 image-plate detector (MAC Science/Bruker AXS) on beamline BL44XU at SPring-8, Harima, Japan. A total of 180 image frames were collected with an oscillation of 1.0° per frame, an exposure time of 1 s and a crystal-to-detector distance of 300 mm. The data sets were processed and scaled using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶).

3. Results and discussion

A wild-type stoUDG crystal appeared in Index condition No. 39 [0.1 M HEPES pH 7.0, 30%(v/v) Jeffamine ED-2001]; therefore, attempts were made to optimize this condition by examining various pH values, precipitant concentrations and additives. Crystals could not be obtained again using the above crystallization conditions; therefore, the conditions, including the expression, purification, stoUDG concentration and crystallization conditions, were re-examined. Unfortunately, we were not able to determine conditions that enabled reproducible crystallization of wild-type stoUDG.

To obtain reproducible stoUDG crystallization, we designed and constructed a deletion mutant of stoUDG (stoUDGΔ). The deletion region was determined by reference to the results of disorder and secondary-structure predictions using the DISOPRED2 (Ward et al., 2004 ▶) and PredictProtein (Tamura et al., 2003 ▶) programs, respectively. Expression, purification and initial crystallization of stoUDGΔ were performed using the same methods as used for wild-type stoUDG. An stoUDGΔ crystal appeared in Index condition No. 42 [0.1 M bis-Tris pH 5.5, 25%(w/v) PEG 3350]. Under optimized crystallization conditions, rod-shaped crystals were obtained (Fig. 1 ▶ a). The addition of glycerol to the reservoir solution seemed to improve the size and the diffraction quality of the stoUDGΔ crystals.

Crystallographic analyses indicated that the stoUDGΔ and stoUDGΔ–uracil crystals belonged to the orthorhombic space group P212121, with unit-cell parameters a = 52.2, b = 52.3, c = 74.5 Å and a = 52.1, b = 52.2, c = 74.1 Å, respectively. Assuming the presence of one molecule per asymmetric unit, the Matthews coefficient V M was determined to be 2.3 Å3 Da−1 (Matthews, 1968 ▶), with a calculated solvent content of 46%. The data-collection statistics are summarized in Table 1 ▶.

Table 1. Data-collection statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| stoUDGΔ | stoUDGΔ–uracil | |

|---|---|---|

| Source | BL44XU, SPring-8 | BL44XU, SPring-8 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9000 | 0.9000 |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = 52.2, b = 52.3, c = 74.5 | a = 52.1, b = 52.2, c = 74.1 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.0–1.70 (1.76–1.70) | 50.0–1.70 (1.76–1.70) |

| No. of observed reflections | 168247 | 123660 |

| No. of unique reflections | 23097 (2275) | 23005 (2248) |

| Multiplicity | 7.3 (7.1) | 5.4 (5.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 99.9 (99.6) |

| R merge † | 0.050 (0.339) | 0.056 (0.397) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 50.8 (6.4) | 37.6 (4.5) |

R

merge =

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of the ith measurement of reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the average value of Ii(hkl) for all i measurements.

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of the ith measurement of reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the average value of Ii(hkl) for all i measurements.

A molecular-replacement search for stoUDGΔ was performed using the coordinates of Thermus thermophilis UDG (48% sequence identity to stoUDG; PDB entry 1ui0; Hoseki et al., 2003 ▶) as the search model. Calculations were performed using MOLREP (Vagin & Teplyakov, 2010 ▶) from the CCP4 program suite (Winn et al., 2011 ▶) and a clear solution was obtained with an R factor of 0.599 and a MOLREP score of 0.496. Rigid-body refinement followed by several cycles of positional refinement was performed using CNS (Brünger et al., 1998 ▶; Brunger, 2007 ▶), resulting in an R work of 0.397 (R free = 0.428). Manual model building was performed using Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▶). A preliminary F o − F c map derived from the stoUDGΔ–uracil diffraction data shows what we take to be electron density for a uracil molecule in the DNA-binding cleft of stoUDG. Precise model building and structure refinement are in progress.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material file. DOI: 10.1107/S1744309112030278/en5508sup1.pdf

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Masato Yoshimura, Dr Eiki Yamashita, Professor Atsushi Nakagawa and the beamline staff for their support at BL44XU at SPring-8. Synchrotron experiments were performed with the approval of the Joint Research Committee of the Institute for Protein Research, Osaka University and the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (Proposal No. 2007B6927). This work was partly supported by the National Project on Protein Structural and Functional Analysis of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (Protein 3000 project). We thank Professor Seiki Kuramitsu for organizing the research group in the program.

Footnotes

Supplementary material has been deposited in the IUCr electronic archive (Reference: EN5508).

References

- Barrett, T. E., Savva, R., Panayotou, G., Barlow, T., Brown, T., Jiricny, J. & Pearl, L. H. (1998). Cell, 92, 117–129. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brunger, A. T. (2007). Nature Protoc. 2, 2728–2733. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brünger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J.-S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N. S., Read, R. J., Rice, L. M., Simonson, T. & Warren, G. L. (1998). Acta Cryst. D54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fogg, M. J., Pearl, L. H. & Connolly, B. A. (2002). Nature Struct. Biol. 9, 922–927. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gallinari, P. & Jiricny, J. (1996). Nature (London), 383, 735–738. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Géoui, T., Buisson, M., Tarbouriech, N. & Burmeister, W. P. (2007). J. Mol. Biol. 366, 117–131. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Haushalter, K. A., Stukenberg, P. T., Kirschner, M. W. & Verdine, G. L. (1999). Curr. Biol. 9, 174–185. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hoseki, J., Okamoto, A., Masui, R., Shibata, T., Inoue, Y., Yokoyama, S. & Kuramitsu, S. (2003). J. Mol. Biol. 333, 515–526. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kaushal, P. S., Talawar, R. K., Krishna, P. D. V., Varshney, U. & Vijayan, M. (2008). Acta Cryst. D64, 551–560. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kavli, B., Otterlei, M., Slupphaug, G. & Krokan, H. E. (2007). DNA Repair, 6, 505–516. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kosaka, H., Hoseki, J., Nakagawa, N., Kuramitsu, S. & Masui, R. (2007). J. Mol. Biol. 373, 839–850. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-W., Dominy, B. N. & Cao, W. (2011). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31282–31287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Leiros, I., Moe, E., Lanes, O., Smalås, A. O. & Willassen, N. P. (2003). Acta Cryst. D59, 1357–1365. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leiros, I., Moe, E., Smalås, A. O. & McSweeney, S. (2005). Acta Cryst. D61, 1049–1056. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lindahl, T. (1974). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 71, 3649–3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lindahl, T. & Nyberg, B. (1974). Biochemistry, 13, 3405–3410. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Moe, E., Leiros, I., Smalås, A. O. & McSweeney, S. (2006). J. Biol. Chem. 281, 569–577. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mol, C. D., Arvai, A. S., Sanderson, R. J., Slupphaug, G., Kavli, B., Krokan, H. E., Mosbaugh, D. W. & Tainer, J. A. (1995). Cell, 82, 701–708. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pearl, L. H. (2000). Mutat. Res. 460, 165–181. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Raeder, I. L. U., Moe, E., Willassen, N. P., Smalås, A. O. & Leiros, I. (2010). Acta Cryst. F66, 130–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ravishankar, R., Bidya Sagar, M., Roy, S., Purnapatre, K., Handa, P., Varshney, U. & Vijayan, M. (1998). Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 4880–4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sartori, A. A., Fitz-Gibbon, S., Yang, H., Miller, J. H. & Jiricny, J. (2002). EMBO J. 21, 3182–3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sartori, A. A., Schär, P., Fitz-Gibbon, S., Miller, J. H. & Jiricny, J. (2001). J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29979–29986. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Savva, R., McAuley-Hecht, K., Brown, T. & Pearl, L. (1995). Nature (London), 373, 487–493. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schormann, N., Grigorian, A., Samal, A., Krishnan, R., DeLucas, L. & Chattopadhyay, D. (2007). BMC Struct. Biol. 7, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K., Peterson, D., Peterson, N., Stecher, G., Nei, M. & Kumar, S. (2003). Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W321–W326.

- Vagin, A. & Teplyakov, A. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Varshney, U., Hutcheon, T. & van de Sande, J. H. (1988). J. Biol. Chem. 263, 7776–7784. [PubMed]

- Ward, J. J., Sodhi, J. S., McGuffin, L. J., Buxton, B. F. & Jones, D. T. (2004). J. Mol. Biol. 337, 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wibley, J. E., Waters, T. R., Haushalter, K., Verdine, G. L. & Pearl, L. H. (2003). Mol. Cell, 11, 1647–1659. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.

- Yang, H., Fitz-Gibbon, S., Marcotte, E. M., Tai, J. H., Hyman, E. C. & Miller, J. H. (2000). J. Bacteriol. 182, 1272–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material file. DOI: 10.1107/S1744309112030278/en5508sup1.pdf