Abstract

We report a consecutive series of 59 patients with MDS who underwent reduced-intensity hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (RI-HSCT) with fludarabine/melphalan conditioning and tacrolimus/sirolimus-based GVHD prophylaxis. Two-year OS, EFS, and relapse incidences were 75.1%, 65.2%, and 20.9%, respectively. The cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality at 100 days, 1 year, and 2 years was 3.4%, 8.5%, and 10.5%, respectively. The incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD was 35.4%; grade III-IV was 18.6%. Forty of 55 evaluable patients developed chronic GVHD, 35 extensive grade. This RI-HSCT protocol produces encouraging outcomes in MDS patients, and tacrolimus/sirolimus-based GVHD prophylaxis may contribute to that promising result.

Keywords: myelodysplastic syndrome, sirolimus, tacrolimus, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are clonal hematopoietic stem-cell disorders characterized by ineffective dysplastic hematopoiesis involving one or more cell lineages, peripheral blood cytopenia, and a high risk of progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Azacitidine and 2-deoxy-5-azacytidine (decitabine) are hypomethylating agents that demonstrate clinical activity with hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with MDS [1, 2], with a survival advantage demonstrated by the recent AZA001 study [3] when compared with conventional care. These agents are now the current standard of care for patients with high-risk MDS; however, 40% to 50% of patients do not respond to therapy, and most responders experience disease progression within 2 years of response.

Currently, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHSCT) is the only potentially curative treatment option for patients with MDS, replacing recipient dysplastic hematopoiesis with healthy donor hematopoiesis and immune system, coupled with a potential graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect. Conventional myeloablative alloHSCT is associated with a relapse rate ranging from 28 to 48%, substantial non-relapse mortality ranging from 34 to 54%, and increased frequency/severity of transplantion-related complications with increased age [4-6]. Over the last several years, reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens have been demonstrated to be safe and efficacious in a wide range of hematologic malignancies, including MDS/AML [7-12].

We previously reported the outcome of RI-HSCT in 43 patients with MDS, or AML arising from MDS, transplanted between September 2000 and December 2004, with encouraging 2-year OS and DFS probabilities of 53.5% and 51.2%, respectively [13]. However, due to a relatively high rate of non-relapse mortality (NRM) of 35.2%, and grade II–IV acute GVHD of 63%, we adopted a new GVHD prophylactic regimen of tacrolimus combined with sirolimus (TACRO/SIRO) in 2005, replacing the previous cyclosporine/mycophenolate mofetil (CSA/MMF)-based prophylaxis.

Sirolimus, originally named rapamycin, binds to the same family of intracellular FK-506-binding proteins (FKBP12 and others) as does tacrolimus (TACRO), but at a distinct site. Sirolimus-FKBP complexes inhibit the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a kinase that regulates cell cycle entry in response to IL-2 signaling and other cellular functions. The combination of tacrolimus and sirolimus (TACRO/SIRO) is associated with low rates of acute GVHD and non-relapse mortality (NRM) [14-17], although sirolimus is also associated with an increased risk of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) [17, 18].

In this retrospective chart review, we describe the transplantation outcomes in patients with MDS (excluding AML) who underwent alloHSCT using fludarabine/melphalan conditioning with tacrolimus/sirolimus (TACRO/SIRO)-based GVHD prophylaxis.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

In this retrospective analysis conducted under City of Hope IRB-approved protocol #09080, we studied outcomes in a consecutive case-series of 59 patients diagnosed with MDS who underwent an RI-HSCT conditioned with fludarabine and melphalan, from an HLA-identical sibling or unrelated donor, between August 2005 and December 2010. A diagnosis of MDS and subtype was based on peripheral blood and bone marrow morphology immediately before the transplantation. We excluded chronic myelomonocytic leukemia from this analysis. RAEB-T was also excluded if the diagnosis was made prior to the current WHO criteria.

Donors and stem cell source

High-resolution polymerase chain reaction was performed using sequence-specific-primers for HLA class I and II as described previously [19]. Twenty-one patients received a transplantation from sibling donors with 6/6 matches while the remaining 38 patients received unrelated donor transplantations (20 donors were 10/10 matched by high resolution typing of HLA-A, B, C, DR, DQ, 18 were <10/10 match). Five patients (8.5%) received bone marrow grafts and the remaining 54 patients (91.5%) received peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) grafts with a median infused CD34+ cell dose at 6.3 ×106/kg (range: 0.7–39.2 ×106/kg).

Preparative regimen and GVHD prophylaxis

All patients received fludarabine 25 mg/m2 intravenously (i.v.) daily for 5 days, followed by melphalan 140 mg/m2 i.v. for conditioning. The TACRO/SIRO GVHD prophylaxis was administered according to published reports [17] as follows: sirolimus 12 mg by mouth on day -3 (loading dose), followed by 4 mg orally daily (dose adjusted to maintain serum levels from 3-12 ng/ml by high performance liquid chromatography); tacrolimus 0.02 mg/kg i.v. daily starting on day -3, and switched to an equivalent oral dose when oral intake was adequate (target serum levels of 5-10 ng/ml). Tacrolimus and sirolimus levels were measured at least weekly until around day 100. Based on these measurements the dose may have been adjusted to maintain target levels and/or for toxicity. For mismatched unrelated donor transplantations, MTX was given at 5 mg/m2 i.v. on day +1, and +5 mg/m2 on days +3 and +6. Rabbit antithymocyte globulin (r-ATG) was given to 10 patients who were considered high-risk for GVHD or graft rejection by the treating physicians; one of these 10 patients also received methotrexate.

Supportive care

Supportive care, including prophylactic antibiotics, antifungal therapy, total parenteral nutrition, hematopoietic growth factors, immune globulin replacement, treatment of mucositis and neutropenic fever, was administered in accordance with institutional standard practice guidelines [20]. Surveillance blood cultures for cytomegalovirus were taken twice weekly between days +21 and +100 post-HSCT. Patients received pre-emptive ganciclovir at onset of cytomegalovirus viremia. Serial samples of peripheral blood or bone marrow were monitored for hematopoietic chimerism using polymerase chain reaction analyses of variable number tandem repeats [21]. Our standard antifungal agents include amphotericin B (1-2 mg/kg/day) or micafungin (50mg/day). Voriconazole was prohibited as a prophylactic drug when TACRO/SIRO was used for GVHD prophylaxis.

Statistical methods

Demographic, disease and treatment characteristics for all patients were summarized using descriptive statistics. Survival estimates were calculated based on the product limit method [22], and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the logit transformation and the Greenwood variance estimate [23]. Differences between Kaplan-Meier curves were assessed by the log-rank test. Patients who were alive at the time of analysis were censored at the last contact date. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the day of stem cell infusion to death from any cause. Event-free survival (EFS) was defined as time from stem cell infusion to relapse/progression, second transplantation (for graft failure), or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Relapse/progression cumulative incidence (RI) was defined as time from transplant to recurrence or progression. Non-relapse mortality (NRM) was measured from stem cell infusion to death from any cause other than disease relapse or progression. The cumulative incidences of RI and NRM were computed as competing risks using the method described by Gooley et al [24]. The significance of demographic, disease and treatment features was assessed using Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis [25].

The list of prognostic variables analyzed included patient age at transplantation (above or below median), donor type (related versus unrelated), donor-patient gender match (female to male versus other combinations), patient CMV serostatus, HLA match degree (fully matched versus others), CD34+ cell dose (above or below median), IPSS Score (low/int-1 versus int-2/high) [26], cytogenetic risk, bone marrow blast %, and disease origin: de novo or secondary MDS. All calculations were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (version 2.11.1; http://www.r-project.org). Statistical significance was set at the P <0.05 level; all P values were two-sided. The data were locked for analysis on October 11, 2011 (analytic date).

RESULTS

Patient demographic and transplantation characteristics are summarized in Table 1. All but two patients (3%) engrafted, with the median neutrophil recovery at 15.5 days (range: 10-39). The median day +30 donor chimerism was 100% (range 20-100%). Of the two patients with graft failure, one patient successfully engrafted after salvage HSCT from a second donor, while the other patient died of graft failure. The overall cumulative incidence of grade II-IV acute graft-versus-host disease was 35.4% (24.8-50.4%) and grade III-IV was 18.6% (10.6, 32.6%). Forty of 55 evaluable patients (surviving > 100 days) developed chronic GVHD; of these 35 were extensive grade (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of Patient/Disease/Transplant Characteristics (N=59)

| Variable | N (Percent) or Median (Range) |

|---|---|

| Patient Age at HCT (median: range) | 56 (20 – 73) |

| # of patients ≥50years | 39 (66.1%) |

| Patient Gender | |

| Female | 22 (37.3%) |

| Male | 37 (62.7%) |

| Donor/Recipient Gender match | |

| Female Donor to Male Recipient | 10 (17.0%) |

| Other combinations | 49 (83%) |

| Percent Blasts in Bone Marrow at HCT | |

| ≤10% | 44 (74.6%) |

| >10% | 15 (25.4%) |

| Percent Blasts in Blood at HCT | |

| ≤5% | 54 (91.5%) |

| >5% | 5 (8.5%) |

| Median time from diagnosis to HCT (months) | 8.2 (1.0 – 131.5) |

| De Novo Disease | 40 (67.8%) |

| Cytogenetic Risk | |

| Low | 23 (39.0%) |

| Intermediate | 17 (28.8%) |

| High | 19 (32.2%) |

| IPSS Score | |

| Int-1 | 23 (39.0%) |

| Int-2 / High | 36 (61.0%) |

| MDS subtype | |

| RA | 25 (42.4%) |

| RARS | 1 (1.7%) |

| RAEB-1 | 14 (23.7%) |

| RAEB-2 | 19 (32.2%) |

| Donor Type | |

| Sibling | 21 (35.6%) |

| Unrelated | 38 (64.4%) |

| HLA Matching | |

| Match | 41 (69.5%) |

| Mismatch (<10/10 A, B, C, DR, DQ) | 18 (30.5%) |

| Stem Cell Source | |

| Bone Marrow | 5 (8.5%) |

| Peripheral Blood Stem Cell | 54 (91.5%) |

| Infused CD34+ Cell Dose (106/kg) | 6.3 (0.7 – 39.2) |

| Prior hypomethylating therapy | 31 (52.5%) |

| 5-Azacitidine | 15 |

| Decitabine | 13 |

| Both | 3 |

| No hypomethylating therapy | 28 (47.5%) |

| Prior Autologous HCT | 9 (15.3) |

| Patient CMV Status | |

| Positive | 46 (78.0) |

| Negative | 13 (22.0) |

Table 2.

Graft-versus-Host Disease

| Variable | N (Percent) or Median (Range) |

|---|---|

| Acute GVHD Grade | |

| Yes | 30 (53.6%) |

| Grade I | 10 (33.3%) |

| Grade II | 10 (33.3%) |

| Grade III | 8 (26.7%) |

| Grade IV | 2 (6.7%) |

| No | 26 (46.4%) |

| Inevaluable (Engraftment Failure/Early Death) | 3 |

| Time to Acute GVHD Onset (Days) | 25 (6 – 84) |

| Chronic GVHD | |

| Yes | 40 (72.7%) |

| Limited | 5 (12.5%) |

| Extensive | 35 (87.5%) |

| No | 15 (27.3%) |

| Inevaluable (Died < 100 days) | 4 |

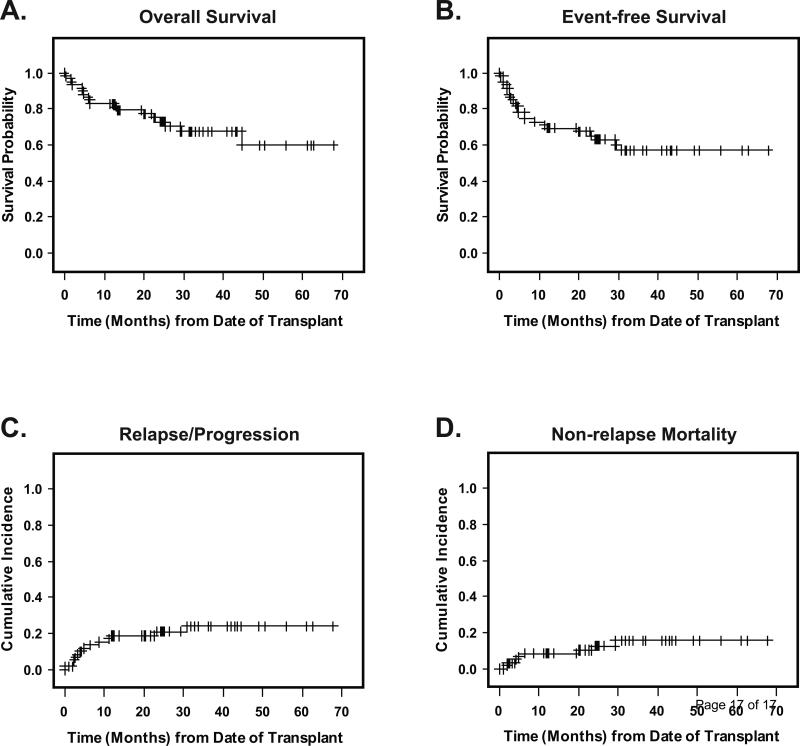

Of 59 patients, 41 were alive after a median follow up of 25 months (range: 6.4-67.8 months) for surviving patients. Nine of the 18 deaths occurred in a setting of relapsed or progressive MDS/AML. Causes of non-relapse deaths included infection (n=3), GVHD (n=3), multi-organ failure (n=1), and unknown cause (no record available, n=1). The 2-year OS, EFS, and relapse incidence were 75.1% (65.2-82.5%), 65.2% (56.5-72.6%), and 20.9% (12.6-34.7%), respectively (Figure 1A-C). The cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality at 100 days, 1 year, and 2 years was 3.4% (0.9-13.2%), 8.5% (3.7-19.6%), and 10.5% (4.9-22.3%), respectively (Figure 1D). By IPSS, the 2-year EFS was 71.4% (54.7-82.9%) for Int-1 (n=23) compared with 61.1% (50.6-70.0%) in Int-2/High (n=36)(not statistically significant, p=0.3)

Figure 1. Outcomes.

Panel A shows the probability of overall survival, from date of transplant to death from any cause and Panel B shows event-free survival from date of transplant to death, relapse, progression, second transplant or engraftment failure., Panel C depicts the cumulative incidence of relapse/progression (RI), and Panel D, the cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality (NRM), RI and NRM were calculated as competing risks. Non-engraftment was also treated as a competing risk for both RI and NRM.

TMA is a complication known to be associated with TACRO/SIRO. Five of 59 patients developed clinical TMA post-HSCT. The 100-day cumulative incidence of TMA was 8.5% (95% CI: 3.7, 19.6). Three additional patients were suspected to have TMA by the treating physician without meeting the full diagnostic criteria [17] (i.e. serum creatinine or lactose dehydrogenase values less than the cutoff).

Prior to HSCT, 31 patients received MDS therapy with hypomethylating agents 5-azacitidine (n=15), decitabine (n=13), or both (n=3). Younger patients were less likely to have received hypomethylating agents; 38% in patients at the median age of 56 years or under, compared with 67% in patients over the median (p=0.03). Thirteen of these 31 patients showed a documented response to therapy (CR = 2, PR/hematologic improvement = 11) while the remaining patients had no response or were not evaluable (<4 cycles given).

By univariable analysis, bone marrow blasts >10% at the time of HSCT were significantly associated with worse EFS [HR 2.52 (1.11-5.76), p=0.03] and OS [HR 3.72 (1.47-9.42), p=0.006]. Some degree of association was also seen for HLA match and cytogenetic risk: HLA match was associated with improved OS [HR 0.42 (0.17-1.06), p=0.07] and unfavorable cytogenetics was associated with inferior EFS compared to good-risk cytogenetics [HR 2.44 (0.94-6.39), p=0.07]. Other variables including IPSS, cytogenetic risk, de novo vs. therapy-related MDS, donor type (related versus unrelated), HLA match (10/10 vs. <10/10), prior autologous HSCT, prior hypomethylating agents, documented response to hypomethylating agents, infused CD34+ cell dose, were not significantly associated with EFS or OS.

DISCUSSION

This is the first report of TACRO/SIRO-based GVHD prophylaxis focused on MDS. Our data after a median follow-up of 25 months showed a promising 2-year EFS of 65.2% (56.5-72.6%). The results compare favorably to recent reports of allogeneic HSCT for MDS using RIC or full-intensity conditioning [7-12]. We previously reported the results of RI-HSCT using fludarabine plus melphalan with cyclosporine/mycophenolate-based GVHD prophylaxis for MDS [13]. This earlier study showed a DFS probability of 51.2% (CI 43.3–58.5) and a relatively high rate of NRM; 35.2%, largely attributable to high rate of acute GVHD (grade II-IV: 63%). The current study showed an improved aGVHD rate of 35.4%, which appears to be translated into an improved NRM of 10.4% at 2 years. While no conclusion can be made without a randomized trial, we believe the observed improvement in survival and GVHD prevention are at least partly due to the tacrolimus/sirolimus-based GVHD prophylaxis. Other possible factors include improved supportive care/anti-fungal agents, use of rabbit ATG in some patients (n=10), and the fact that patients with RAEB-T/AML arising from MDS are excluded from the current study.

The current data are consistent with our earlier observations in myelofibrosis (n=23 patients), in which the estimated 2-year OS for the CSA/MMF cohort was 55.6% (CI: 36.0-71.3), compared with 92.9% (CI: 63.3-98.8) for the TACRO/SIRO cohort (P=0.047) [27]. The probability of grade III or IV acute GVHD (aGVHD) was 60% for the CSA/MMF patients, and 10% for the TACRO/SIRO (P=0.01).

The combination of TACRO/SIRO was evaluated by researchers at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) and our center with encouragingly low rates of GVHD and NRM in both fully ablative conditioning and RIC [14-16, 28]. The use of sirolimus has also been found to be associated with reductions in cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia [29] and the incidence/severity of oral mucositis [30]. Our recent prospective trials at City of Hope also showed similar encouraging results [17] associated with a reduction in severe aGVHD (grade III-IV) and NRM.

However, sirolimus is associated with an increased risk of TMA in a retrospective analysis of myeloablative allogeneic HSCT recipients at DFCI [18] and in our phase II trial at City of Hope [17]. Another recent study showed an increase in veno-occlusive disease [VOD] associated with sirolimus use, particularly when methotrexate was added to the GVHD prophylaxis, or when busulfan/cyclophosphamide was used in conditioning [31]. In this case series, we observed a 100-day cumulative incidence of TMA at 8.5%, which is consistent with our experience with reduced-intensity conditioning.

Many of our patients are referred to us after they have been started on hypomethylating therapy, though little is known about the impact of hypomethylating agents on transplantation outcomes in MDS. De Padua Silva and colleagues reported a small case series in which the transplantation-related toxicity did not seem to be increased by previous use of decitabine [32]. While cytoreduction and reduced transfusion requirements prior to HSCT may potentially improve the transplantation outcome, it is unclear whether transplantation should be performed at the time of best response or should be postponed until loss of response to hypomethylating agents is evident.

There have been no prospective studies to date evaluating the outcome differences between non-transplantation approaches using hypomethylating agents/best supportive care and alloHSCT, to qualitatively and quantitatively compare the survival and quality of life of MDS patients. Such a study was recently requested by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Our encouraging data support the hypothesis that alloHSCT is associated with a better survival benefit for MDS patients whose general health condition permits HSCT and who have available donors. This question needs to be addressed by a carefully designed prospective phase III trial with a biologic allocation according to donor availability.

In summary, our data showed a very promising outcome with RI-HSCT for MDS patients, particularly with the use of TACRO/SIRO-based GVHD prophylaxis, and compares favorably to recent reports using either RIC or full-intensity conditioning transplantation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the transplant coordinators and transplant nurses for their dedicated care of our patients. We also thank all members of the Hematopoietic Cell Transplant team for their constant support of the program, including the clinical research associates for their protocol management and data collection support.

Funding: This work was supported by the Comprehensive Cancer Center grant (P30 CA33572), Hem/HCT Program Project grant (PO1 CA30206-21) and the Tim Nesvig Lymphoma Research Fund, which recently awarded a grant to Dr. Ryotaro Nakamura.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: RN, MRO, JP, and SJF conceived and designed the study; RN, MRO, JChao, JA, PP, VP, AS, DSnyder, RB, and SJF provided study materials or patients; RN, TS, JCai, RM, KC, SW, DSenitzer collected and assembled the data (e.g. HLA typing, pathology data. stem cell doses, clinical endpoints); RN, JP, TS, and ST analyzed and interpreted the data; and RN, MRO, JP, ST, and SJF drafted the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Silverman LR, Demakos EP, Peterson BL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of azacitidine in patients with the myelodysplastic syndrome: a study of the cancer and leukemia group B. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2429–2440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silverman LR, McKenzie DR, Peterson BL, et al. Further analysis of trials with azacitidine in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome: studies 8421, 8921, and 9221 by the Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3895–3903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, et al. Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open-label, phase III study. The lancet oncology. 2009;10:223–232. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson JE, Appelbaum FR, Fisher LD, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for 93 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 1993;82:677–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zikos P, Van Lint MT, Frassoni F, et al. Low transplant mortality in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: a randomized study of low-dose cyclosporin versus low-dose cyclosporin and low-dose methotrexate. Blood. 1998;91:3503–3508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro-Malaspina H, Harris RE, Gajewski J, et al. Unrelated donor marrow transplantation for myelodysplastic syndromes: outcome analysis in 510 transplants facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program. Blood. 2002;99:1943–1951. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lima M, Anagnostopoulos A, Munsell M, et al. Nonablative versus reduced-intensity conditioning regimens in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: dose is relevant for long-term disease control after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2004;104:865–872. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Lima M, Couriel D, Thall PF, et al. Once-daily intravenous busulfan and fludarabine: clinical and pharmacokinetic results of a myeloablative, reduced-toxicity conditioning regimen for allogeneic stem cell transplantation in AML and MDS. Blood. 2004;104:857–864. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho AY, Pagliuca A, Kenyon M, et al. Reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia with multilineage dysplasia using fludarabine, busulphan, and alemtuzumab (FBC) conditioning. Blood. 2004;104:1616–1623. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Besien K, Artz A, Smith S, et al. Fludarabine, melphalan, and alemtuzumab conditioning in adults with standard-risk advanced acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5728–5738. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.15.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tauro S, Craddock C, Peggs K, et al. Allogeneic stem-cell transplantation using a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen has the capacity to produce durable remissions and long-term disease-free survival in patients with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9387–9393. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laport GG, Sandmaier BM, Storer BE, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning followed by allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for adult patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and myeloproliferative disorders. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura R, Rodriguez R, Palmer J, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with fludarabine and melphalan is associated with durable disease control in myelodysplastic syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:843–850. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antin JH, Kim HT, Cutler C, et al. Sirolimus, tacrolimus, and low-dose methotrexate for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in mismatched related donor or unrelated donor transplantation. Blood. 2003;102:1601–1605. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cutler C, Kim HT, Hochberg E, et al. Sirolimus and tacrolimus without methotrexate as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after matched related donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004;10:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2003.12.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cutler C, Li S, Ho VT, et al. Extended follow-up of methotrexate-free immunosuppression using sirolimus and tacrolimus in related and unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;109:3108–3114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez R, Nakamura R, Palmer JM, et al. A phase II pilot study of tacrolimus/sirolimus GVHD prophylaxis for sibling donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using 3 conditioning regimens. Blood. 2010;115:1098–1105. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-207563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cutler C, Henry NL, Magee C, et al. Sirolimus and thrombotic microangiopathy after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaffer M, Olerup O. HLA-AB typing by polymerase-chain reaction with sequence-specific primers: more accurate, less errors, and increased resolution compared to serological typing. Tissue Antigens. 2001;58:299–307. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.580503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blume KG, Forman SJ, Appelbaum FR, editors. Thomas’ Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ugozzoli L, Yam P, Petz LD, et al. Amplification by the polymerase chain reaction of hypervariable regions of the human genome for evaluation of chimerism after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1991;77:1607–1615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan G, Meier P. Non-parametric estimations from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research: volume II, the design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Sci Publ. 1987;82:1–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1972;B34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89:2079–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snyder DS, Palmer J, Gaal K, et al. Improved outcomes using tacrolimus/sirolimus for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant as treatment of myelofibrosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alyea EP, Li S, Kim HT, et al. Sirolimus, tacrolimus, and low-dose methotrexate as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in related and unrelated donor reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:920–926. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marty FM, Bryar J, Browne SK, et al. Sirolimus-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis protects against cytomegalovirus reactivation after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a cohort analysis. Blood. 2007;110:490–500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cutler C, Li S, Kim HT, et al. Mucositis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a cohort study of methotrexate- and non-methotrexate-containing graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis regimens. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cutler C, Stevenson K, Kim HT, et al. Sirolimus is associated with veno-occlusive disease of the liver after myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2008;112:4425–4431. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-169342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Padua Silva L, de Lima M, Kantarjian H, et al. Feasibility of allo-SCT after hypomethylating therapy with decitabine for myelodysplastic syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43:839–843. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]