Abstract

Background

Exposure of rhesus macaque fetuses for 24 h, or neonates for 9 h, to ketamine anesthesia causes neuroapoptosis in the developing brain. The present study further clarifies the minimum exposure required for, and the extent and spatial distribution of, ketamine-induced neuroapoptosis in rhesus fetuses and neonates.

Method

Ketamine was administered by intravenous infusion for 5 h to postnatal day 6 rhesus neonates, or to pregnant rhesus females at 120 days gestation (full term = 165 days). Three hours later, fetuses were delivered by caesarian section, and the fetal and neonatal brains were studied for evidence of apoptotic neurodegeneration, as determined by activated caspase-3 staining.

Results

Both the fetal (n = 3) and neonatal (n = 4) ketamine-exposed brains had a significant increase in apoptotic profiles compared to drug-naive controls (fetal n = 4; neonatal n = 5). Loss of neurons due to ketamine exposure was 2.2 times greater in fetuses than in neonates. The pattern of neurodegeneration in fetuses was different from that in neonates, and all subjects exposed at either age had a pattern characteristic for that age.

Conclusion

The developing rhesus macaque brain is sensitive to the apoptogenic action of ketamine at both a fetal and neonatal age, and exposure duration of 5 h is sufficient to induce a significant neuroapoptosis response at either age. The pattern of neurodegeneration induced by ketamine in fetuses was different from that in neonates, and loss of neurons attributable to ketamine exposure was 2.2 times greater in the fetal than neonatal brains.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, several classes of drugs, including those that block N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors, those that activate γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptors, and ethanol (which has both NMDA antagonist and GABA-mimetic properties), have been shown to trigger widespread apoptotic death of neurons in the developing animal brain1–5. Vulnerability to the apoptogenic mechanism reaches its peak during the developmental period of rapid synaptogenesis,1,2 also known as the brain growth spurt period, which in rodents occurs primarily during the first 2 weeks after birth, but in humans extends from about mid-gestation to several years after birth.6

Drug-induced developmental neuroapoptosis has been shown at both light and electron microscopic levels to have classical morphological characteristics of apoptosis1,3,5,7,8. The cell death process involves translocation of Bax protein to mitochondrial membranes, and extra-mitochondrial leakage of cytochrome c, followed by activation of caspase-3.9–11 Because commitment to cell death occurs prior to the caspase-3 activation step11, activated caspase-3 (AC3) immunohistochemistry reliably identifies cells that have progressed beyond the point of cell death commitment. Therefore, AC-3 immunohistochemistry has been used extensively for marking dying neurons in recent studies focusing on drug-induced developmental neuroapoptosis.3,8–27

Neuroapoptosis induced in the developing brain by NMDA antagonist and GABA-mimetic drugs is potentially relevant in a public health context because there are many agents that the developing human brain may be exposed to that have NMDA antagonist or GABA-mimetic properties, including drugs that are sometimes abused by pregnant mothers (ethanol, phencyclidine, ketamine, nitrous oxide, barbiturates, benzodiazepine 28–30,*), and many drugs used worldwide in obstetric and pediatric medicine as anticonvulsants, sedatives or anesthetics. Of particular concern is mounting evidence from animal studies that even single or brief exposure to clinically relevant doses of commonly used anesthetics (ketamine, midazolam, propofol, isoflurane, sevoflurane, chloral hydrate) may trigger a significant neuroapoptosis response in the developing brain,3,13–18,22,23,26 and that exposure of the developing rodent brain to these agents can result in long-term neurobehavioral impairments.5,26,31–34 In addition, there is evidence potentially linking anesthesia exposure in infancy with long-term neurobehavioral deficits in both human35–39 and nonhuman40 primates.

The important question whether anesthetic drugs can trigger neuroapoptosis in the developing non-human primate (NHP) brain was first addressed by Slikker and colleagues who reported20,21 that intravenous infusion of ketamine triggered neuroapoptosis in the 5-day old (P5) rhesus macaque brain if the infusion was continued for 9 or 24 h, but not if it was stopped at 3 hours. In addition, it was shown that a 24-h ketamine infusion triggered neuroapoptosis in the G120 fetal rhesus macaque brain20, but briefer periods of fetal exposure were not studied. More recently, we have shown27 that a neuroapoptosis response is induced in the 6-day old rhesus macaque brain by 5-h exposure to the potent volatile anesthetic, isoflurane. To further clarify the clinical relevance of ketamine's apoptogenic potential, we administered ketamine by intravenous infusion for 5 h to pregnant (gestational day 120; G120) or neonatal (postnatal day 6; P6) rhesus macaques, and examined the fetal or neonatal brains 3 h later for histological evidence of apoptotic neurons.

METHODS AND METHODS

Animals and Experimental Procedures

All animal procedures were approved by the Oregon National Primate Research Center (Beaverton, OR) and Washington University Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (St. Louis, Missouri) and were conducted in full accordance with the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Two studies were performed, one pertaining to fetal and the other to neonatal subjects:

Fetuses

To produce time-mated pregnant dams, cycling females were paired for 4 days with fertile males beginning on day 10 ± 2 of the menstrual cycle (first day of menses = day 1; gestation length was counted from the first day of pairing, first day = day 0). Pregnancy was confirmed by blood progesterone levels of greater than 1 ng/ml at 29 ± 2 and 42 ± 3 days after the menses prior to mating. Blood samples were collected from conscious animals using minimal restraint. The pregnant dams were not exposed to any sedative agents throughout the pregnancy. Pregnant female macaques at G120 were exposed for 5 hours to no anesthesia (n = 4) or to an intravenous infusion of ketamine (n = 3). Full term for these macaques is 165 days.

At initiation of the experiment the pregnant females were gently restrained according to standard methods (in the same apparatus used for blood sampling, see above, thus the animals are well accustomed to the procedure) to facilitate placement of an IV catheter for intravenous administration of ketamine. Anesthesia was induced by a bolus of ketamine (10 mg/kg), which was followed by a continuous ketamine infusion at 10–85 mg/kg/hour for 5 h, augmented by additional IV boluses as needed to maintain an intermediate surgical plane of anesthesia, defined as no movement and not more than 10% increase in heart rate or blood pressure in response to a profound mosquito-clamp pinch at hand and foot (checked every 30 min). Animals assigned to ketamine anesthesia were tracheally intubated (conventional direct laryngoscopy, 4.0 ID endotracheal tube; Mallinckrodt, Hazelwood, MO), mechanically ventilated using a conventional anesthesia machine ventilator (Hallowell EMC, Pittsfield, MA), to control oxygenation and gas exchange, and maintained using extended physiologic monitoring (continuous endtidal carbon dioxide, FiO2, electrocardiogram, peripheral oxygen saturation, noninvasive blood pressure [every 15 min], body temperature [esophageal temperature probe, Smiths Medical ASD, SurgiVet Monitor, Smith Medical, Wankesha, WI], blood gases, metabolic profile including pH, BE, BUN, hematocrit, hemoglobin, Na, Cl, K, and serum glucose and lactate levels [every 2 h; i-STAT, Princeton, NJ]). Intravenous fluids (Lactated Ringer’s solution) and glucose were substituted as needed and physiologic temperature was maintained using a warming device and forced warm air (Bair Hugger, Arizant Healthcare Inc., Eden Prairie, MN). Ultrasonography was performed hourly to monitor fetal heart rate and health of the fetus. After 5 h the ketamine infusion was stopped and the animals were observed for 3 h. The trachea was extubated when appropriate, and the animals were then returned to climatized cages and offered biscuits and water as tolerated for the remainder of the observation period. At 8 h after time zero, ketamine anesthesia was induced again (10 mg/kg IV, followed by a continuous infusion at 50–85 mg/kg/hour), and a cesarean section was performed to deliver the fetus, which was euthanized for tissue collection (high dose phenobarbital followed by transcardial perfusion according to National Institutes of Health guidelines). Following recovery from anesthesia, the dam was given appropriate analgesic and was returned to her home cage. Dams that were randomized to receive no anesthesia (control group) were measured at baseline, received an IV injection of saline by the same method as the ketamine treated animals, and then returned to their cage where they had access to light food and water ad libitum. Eight hours later a cesarean section was performed in order to remove the fetus for transcardial perfusion under deep anesthesia as described above, and the dam was allowed to recover according to the above paradigm.

Neonates

Neonates were naturally delivered from dams that had been group housed or were specifically paired with males as part of the time-mated breeding program. Pregnancy was determined by ultrasound under light sedation of the dam using ketamine (5–10 mg/kg) during the first or early second trimester. On postnatal day 6 (P6) neonatal rhesus macaques were exposed for 5 h either to no anesthesia (n = 5) or to intravenous ketamine (n = 4). Neonates were gently hand restrained; after establishing an intravenous access and blood draws for baseline measurements, the animals assigned to receive general anesthesia were given ketamine (20 mg/kg bolus IV) followed by a continuous IV infusion (20–50 mg/kg/hour for 5 h) and additional IV boluses for maintenance of an intermediate surgical plane of anesthesia, defined as no movement and not more than 10% increase in heart rate or blood pressure in response to a profound mosquito-clamp pinch at hand and foot (checked every 30 min). The animals were tracheally intubated (semi-rigid fiberoptic endoscope; Karl Storz America, El Segundo, CA; 2.0 ID endotracheal tube; Mallinckrodt), mechanically ventilated (small animal ventilator; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA), and maintained using extended physiologic monitoring (continuous endtidal carbon dioxide, FiO2 [Capnomac, Datex Ohmeda, Madison, WI], electrocardiogram, peripheral oxygen saturation, noninvasive blood pressure [every 15 min; SurgiVet Advisor V9200, Smith Medical], rectal temperature [hand held rectal thermometer, Vicks, V965F, KAZ Inc., Proctor and Gamble Co. Cincinnati, OH]), blood gases, metabolic profile including pH, BE, BUN, hematocrit, hemoglobin, Na, Cl, K, and serum glucose and lactate levels [every 2 h; i-STAT]). After 5 h, the ketamine infusion was stopped and the animals were observed for 3 h. The trachea was extubated when appropriate, and the animals were then kept in an infant monkey incubator (Snyder ICU cage, Snyder MFG.Co, Centennial, CO) and were provided formula as tolerated. At the end of the 3-h observation period (8 h after time zero), and following final measurements, the animals received ketamine (20 mg/kg IV), followed by high-dose phenobarbital to secure a deep level of anesthesia, and were then transcardially perfusion-fixed to prepare the brain for histopathological analysis. Animals that were randomized to the control group (no anesthesia) were measured at baseline, received an IV injection of saline in order to mimic the stress to which the experimental animals were exposed prior to being anesthetized, and were then returned to their mothers until final measurements and euthanasia 8 h later.

Rationale for the ketamine protocol employed

The present study pertaining to ketamine is part of a larger research program aimed at comparing the potential toxic impact of several anesthetic drugs on the developing NHP brain. In order to make such a comparison, each agent must be administered in a manner that provides the same level of anesthesia for the same duration of time. Thus, the 5-hketamine perfusion protocol employed in this study was chosen to match a specific depth and duration of anesthesia that is used for each anesthetic drug being tested. The authors recognize that ketamine is not commonly used as a stand-alone drug in either pediatric or obstetric anesthesia to maintain patients in a fully anesthetized state for an extended period of hours, and this is a caveat that must be taken into consideration in interpreting the human significance of the findings.

Histopathology Methods

For histopathological analysis, the perfusion-fixed neonatal and fetal brains were cut on a vibratome into 70 µM serial coronal sections across the entire rostrocaudal extent of the forebrain and midbrain, and into serial sagittal sections across the brain stem and cerebellum. Sections were selected at 2 mm intervals and stained for detection and quantification of apoptotic profiles by AC3 immunohistochemistry, as described previously.3,8–27 Before applying the AC3 stain, sections were processed for antigen retrieval to reduce background nonspecific staining and maximize the AC3-specific signal. For antigen retrieval, sections were immersed in a citrate buffer, pH 6.0 and subjected to heat in a pressure cooker for 10 min.

It can be considered a limitation of the present study that only a single posttreatment survival interval was used, and only a single method (AC3 staining) was employed to detect apoptotic profiles. We chose the AC3 staining procedure for several reasons: 1) It has been shown in numerous prior studies3,8–26 to faithfully mark cellular profiles that are undergoing apoptotic degeneration following exposure to various apoptogenic drugs, including ketamine13,15,16,23; 2) It has been demonstrated that cellular profiles marked by the AC3 stain are also marked by the cupric silver stain which selectively stains cells that are dead or dying1–5,12; 3) It has been confirmed by electron microscopy that these cells display all of the classical ultrastructural characteristics of cells undergoing cell death by apoptosis;1–3,7,8,12 4) In addition, it has been found9,27 that the AC3 stain is valuable, not only for identifying cells that are undergoing apoptosis, but for revealing whether the cell is in an early or advanced stage of degeneration, and for revealing what type of cell is undergoing degeneration. The AC3 stain can provide this information because, in the early stages of apoptotic degeneration, brain cells generate copious amounts of AC3 protein, which fills the cell body and its processes, so that the full microanatomy of the cell can be visualized by immunohistochemical staining with AC3 antibody in this early stage. In the ensuing several hours, the processes shrivel and become fragmented, the cell body becomes condensed or rounded up into a spherical shape, and these changes signify that the cell is progressing from early to advanced stages of cell death.27

Quantification of apoptotic cells

AC3-positive cellular profiles were counted by an investigator who was blinded to the treatment condition. Each stained section was comprehensively scanned by light microscopy using a 10× objective lens and a computer-assisted stereoinvestigator system (Microbrightfield Inc., Williston, VT) with an electronically driven automatic stage to plot the number and location of each AC3 stained neuronal profile in each section. The total area scanned, and the total number of stained neurons per section and per brain were computer-recorded. The total area was converted to volume by multiplying by the thickness of the section (70 µM), and the total number of neurons was divided by the total volume of tissue within which counts were made to yield a density count (number of stained profiles per mm3) for each brain. Density counts were converted to total numbers of apoptotic neurons in a given brain by calculating the mean volume of tissue per counted section and multiplying this times the number of serial sections cut from the entire brain. The density of apoptotic neurons (number per mm3) times the total brain volume yielded an accurate estimate of the total number of apoptotic neurons per brain.

Statistical Evaluation

There are important ethical and logistical considerations regarding nonhuman primate experimentation. It is important to include as few animals as are needed to answer research questions with as much precision as possible. Prior experiments in nonhuman primates and rodents have shown that, when neonatal animals are exposed to drugs that consistently and potently induce neuroapoptosis, the apoptosis is extensive and can be demonstrated compellingly with a small number of animals, typically between three and five per group.13,14,16,20–22,23–25,27 For statistical analysis, an unpaired Student's t-test with Welch correction, where appropriate, was used, a two-sided P value less than 0.05 was judged significant, and the 95% confidence interval for the mean difference provided a measure of precision. Statistical analysis was performed with Analyse-It® Statistical Software (Leeds, United Kingdom) for Microsoft Excel® (Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

Fetuses

The pregnant dams were assigned on post-conception day 120 ± 2 days to receive general anesthesia (ketamine group; body weight range 6.15 to 7.45 kg; n = 3) or not (control group; 5.40 to 7.45 kg; n = 4). Induction (10 mg/kg, IV) and maintenance of ketamine anesthesia was generally well tolerated, and the trachea of all animals were intubated for airway control. The animals retained adequate spontaneous ventilation and were connected to the breathing circuit of a conventional anesthesia machine to control oxygenation and gas exchange. Blood gases, acid-base status, laboratory variables, glucose and lactate level, as well as hemodynamic variable and body temperature were controlled within species-specific physiologic limits throughout the experimental period. Fetal heart rates remained within physiologic limits and varied in concert with the maternal heart rate. The animals were extubated without problems within about 90 min after the ketamine infusion was stopped, and the dams remained somnolent and were kept in a climatized cage under direct observation until the scheduled cesarean section. The cesarean sections were conducted using ketamine general anesthesia and standard intraoperative monitoring according to established protocols at the Oregon National Primate Research Center surgical center. The animals tolerated the procedure well and retained stable vital signs, blood gases and acid-base levels within physiologic limits (table 1). The time from induction of general anesthesia to clamping of the umbilical cord of the fetuses was less than 10 min in all cases and fetal heart rate monitoring prior to surgical incision and umbilical arterial and venous blood samples confirmed fetal well-being until the cord was clamped (table 2), which was followed immediately by transcardial perfusion fixation as described in the method section. Fetal body weight (ketamine group 215 to 237 g; control group 129 to 252 g) as well as other standard body dimensions were age-appropriate for the macaque G120 time point.

Table 1.

Physiologic Variables of Pregnant Females (G120) during Ketamine Anesthesia

| Anesthesia Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 h | 2.5 h | 4.5 h | |

| Maternal | |||

| Temp (°C) | 37.6 (37.3–37.9) | 37.7 (37.2–38.2) | 37.8 (37.5–38.5) |

| MAP (mmHg) | 94 (87–101) | 68 (59–74) | 61 (51–70) |

| HR (/min) | 148 (139–161) | 115 (101–132) | 128 (106–144) |

| Fetal HR (/min) | 178 (168–190) | 160 (138–185) | 157 (133–190) |

| Maternal | |||

| EtCO2 (mmHg) | 35 (33–29) | 31 (27–37) | 30 (24–37) |

| pH (arterial) | 7.44 (7.38–7.49) | 7.43 (7.40–7.46) | 7.41 (7.40–7.44) |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 37 (35–39) | 34 (31–38) | 33 (32–34) |

| PaO2(mmHg) | 289 (284–294) | 178 (122–259) | 223 (209–249) |

| Hb (mg/dl) | 13 (11–14) | 12 (10–13) | 12 (11–12) |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 64 (59–73) | 70 (47–92) | 71 (56–91) |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.5 (1.1–4.9) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

Data are presented as Median (range: Min – Max).

EtCO2 = end-tidal carbon dioxide; Fetal HR = ultrasound-guided measurements of fetal heart rate (six measurements/time point/animal); Hb = hemoglobin; HR = heart rate; MAP = mean arterial pressure (noninvasive); PaCO2 = arterial carbon dioxide tension; PaO2 = arterial oxygen tension (FiO2 = 0.4); Temp = temperature (rectal).

Table 2.

Physiologic Variables of Dams and Fetuses Immediately Prior and After Cesarean Section (C/S)

| Group | Dams after induction of anesthesia and before C/S | Fetus immediately after C/S (Umbilical Artery)# | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temp | Control (n = 4) | 37.7 (37.3–38.2) | |

| (°C) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 38.8 (38.5–39.2) | |

| MAP | Control (n = 4) | 54 (42–68) | |

| (mmHg) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 70 (57–84) | |

| HR | Control (n = 4) | 171 (145–191) | |

| (/min) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 155 (133–68) | |

| Fetal HR | Control (n = 4) | 171 (165–183) | |

| (/min) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 175 (140–213) | |

| EtCO2 | Control (n = 4) | 34 (26–41) | |

| (mmHg) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 28 (23–34) | |

| pH | Control (n = 4) | 7.27 (7.20–7.35) | 7.23 (7.20–7.25) |

| (venous) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 7.39 (7.38–7.40) | 7.17 (7.08–7.26) |

| - | |||

| PvCO2 | Control (n = 4) | 43 (38–48) | 58 (53–62) |

| (mmHg) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 35 (34–36) | 65 (49–81) |

| - | |||

| PvO2 | Control (n = 4) | 56 (48–63) | 16 (10–26) |

| (mmHg) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 43 (38–47) | 12 (11–13) |

| - | |||

| Hb | Control (n = 4) | 14 (12–15) | 13 (12–16) |

| (mg/dl) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 13 (12–14) | 15 (14–15) |

| - | |||

| Glucose | Control (n = 4) | 83 (61–96) | 56 (34–66) |

| (mmol/L) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 53 (46–65) | 50 (34–66) |

| Lactate | Control (n = 4) | 6.7 (3.5–9.2) | 4.0 (2.8–5.5) |

| (mmol/L) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 0.8 (0.7–0.8) | 4.5 (2.9–6.1) |

Data are presented as Median (range: Min – Max)

EtCO2 = end-tidal carbon dioxide; Hb = hemoglobin; HR = heart rate; MAP = mean arterial pressure (noninvasive); PvCO2 = venous carbon dioxide tension; PvO2 = venous oxygen tension; Temp = temperature (rectal).

n = 3 for Ketamine group due to spurious sample.

Over the first 90 min, ketamine doses of 1.10 to 1.35 mg/kg/min were necessary to achieve the desired anesthetic depth (no movement and <10% increase in heart rate / blood pressure in response to profound mosquito-clamp pinch). The total doses of ketamine per animal were 260.4 to 432.6 mg/kg during the 5-h anesthesia (48.1 to 86.5 mg/kg/h). One dam showed clinical signs of seizure activity (eye blinking, bilateral upper extremity jerks) at 85 min of ketamine anesthesia. This animal received 2.5 mg diazepam intravenously which immediately stopped the clinical seizure-like activity. The subsequent clinical course of this animal was uneventful.

Animals assigned to the control group had unremarkable baseline measurements and underwent cesarean section 5 h later according to the same protocol and monitoring. At time of delivery the measured physiologic variables (fetal heart rate, metabolic status and blood gases of dam and fetus) were within physiologic limits and comparable to those in the ketamine group. One dam in the control group showed an anion gap-positive metabolic acidosis with elevated lactate levels. Further laboratory evaluation of this animal revealed mild aspartate aminotransferase elevation and low globulin levels. Differential diagnoses include subclinical chronic liver or renal disease, chronic infection or a tumor disease. At the time of the experiment the animal was clinically unremarkable as was the delivered fetus. The brain of this fetus had a low apoptotic profile count similar to the other brains in the control group.

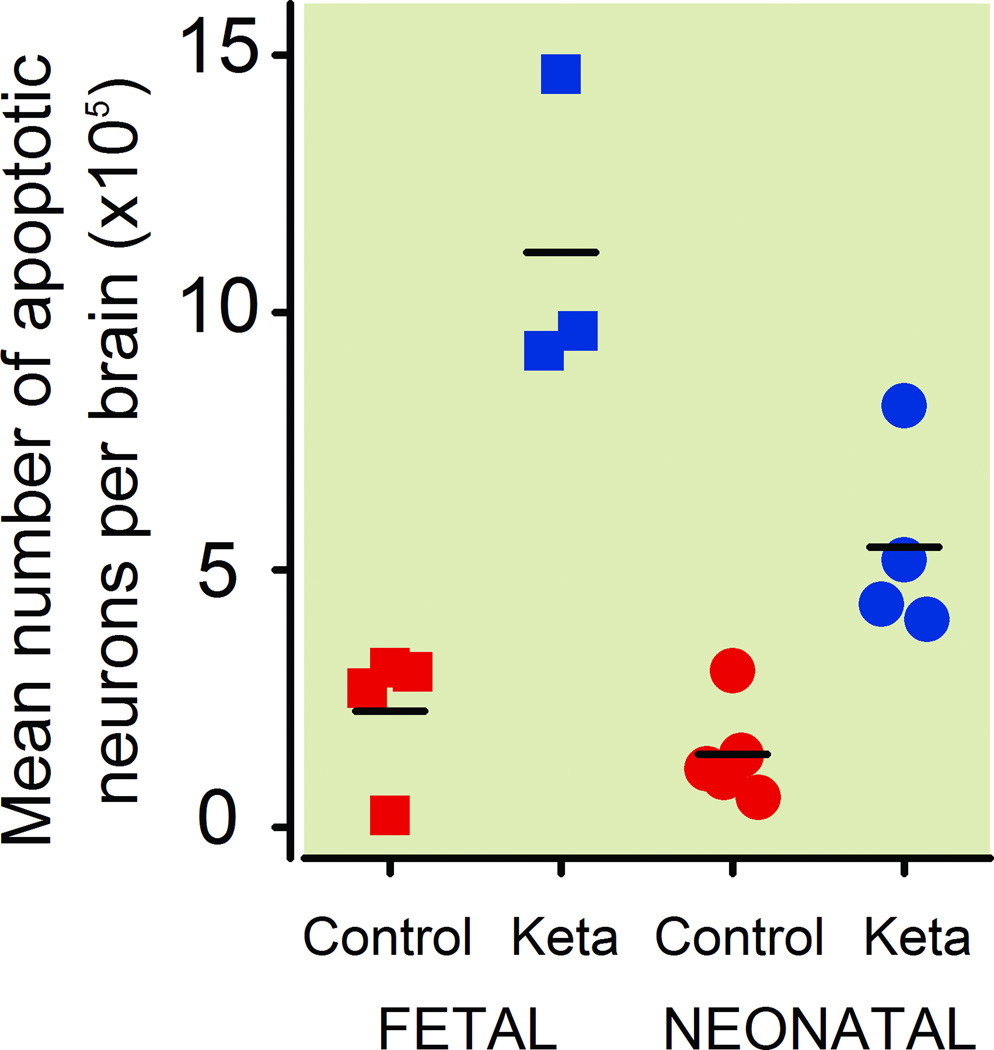

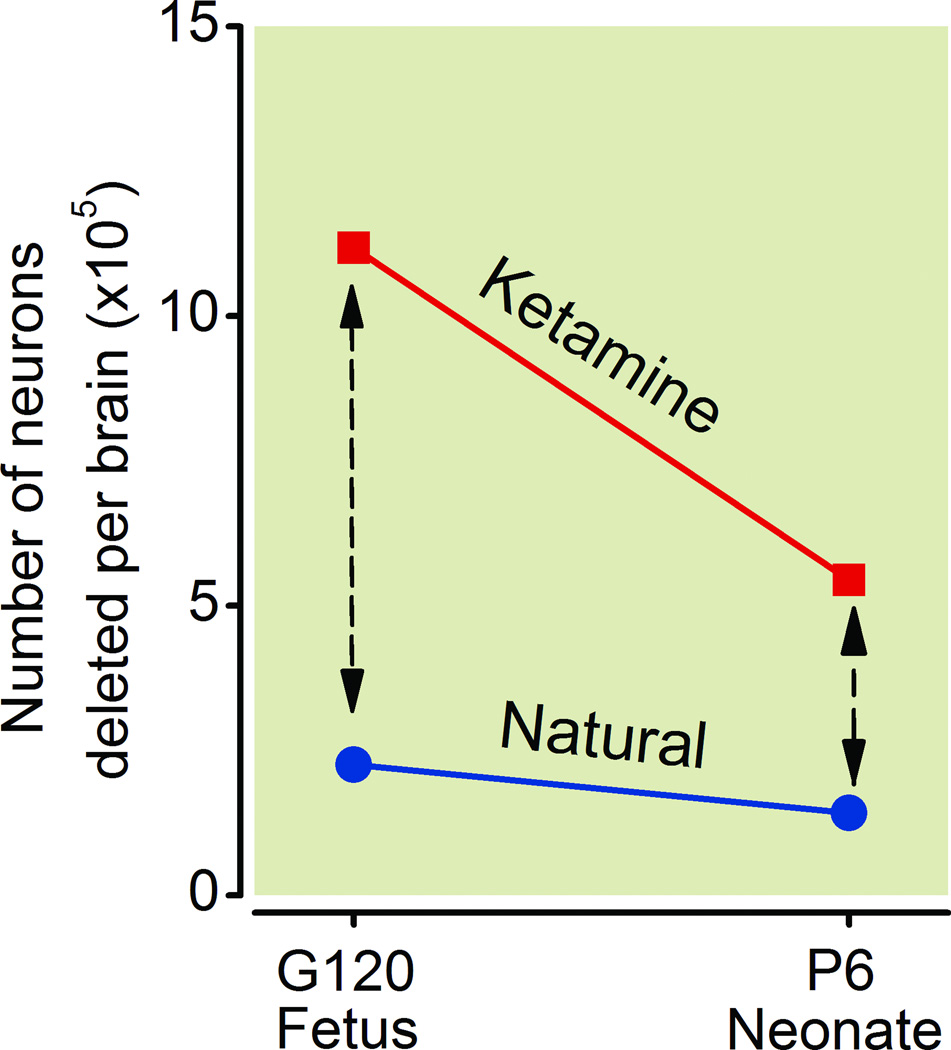

Quantitative evaluation of AC3-stained brain sections from the fetal brains (G120) revealed that the mean (± SD) number of AC3-positive neuronal profiles per brain in the three ketamine-exposed fetal brains was 11.17 ×105 ± 2.99 ×105, and in the four control fetal brains was 2.26 ×105 ± 1.37 ×105 (fig. 1), which amounts to a 4.9-fold increase in the number of apoptotic neurons in the ketamine-exposed fetal brains compared to the drug-naive controls. The difference between the means for ketamine-exposed versus control brains was 8.92 ×105 (95% confidence interval, 13.18 ×105 to 4.65 ×105, p = 0.003).

Figure 1.

Neuroapoptosis, as detected by activated caspase-3 (AC3) positivity, induced in the fetal and neonatal monkey brain by ketamine exposure for 5 h. The mean number of AC3-positive neuronal profiles in the ketamine-exposed fetal brains was 4.9-fold higher than in the drug-naive fetal control brains. The difference between the means for ketamine-exposed versus control brains was 8.92 ×105 (95% confidence interval, 13.18 ×105 to 4.65 ×105, p = 0.003). The mean number of AC3-positive neuronal profiles in the ketamine-exposed neonatal brains was 3.83-fold higher than in the drug-naive neonatal control brains. The difference in the mean number of apoptotic neurons between the ketamine and control groups was 4.02 ×105 (95% confidence interval, 6.29 ×105 to 1.74 ×105, p=0.004). AC3 = activated caspase-3.

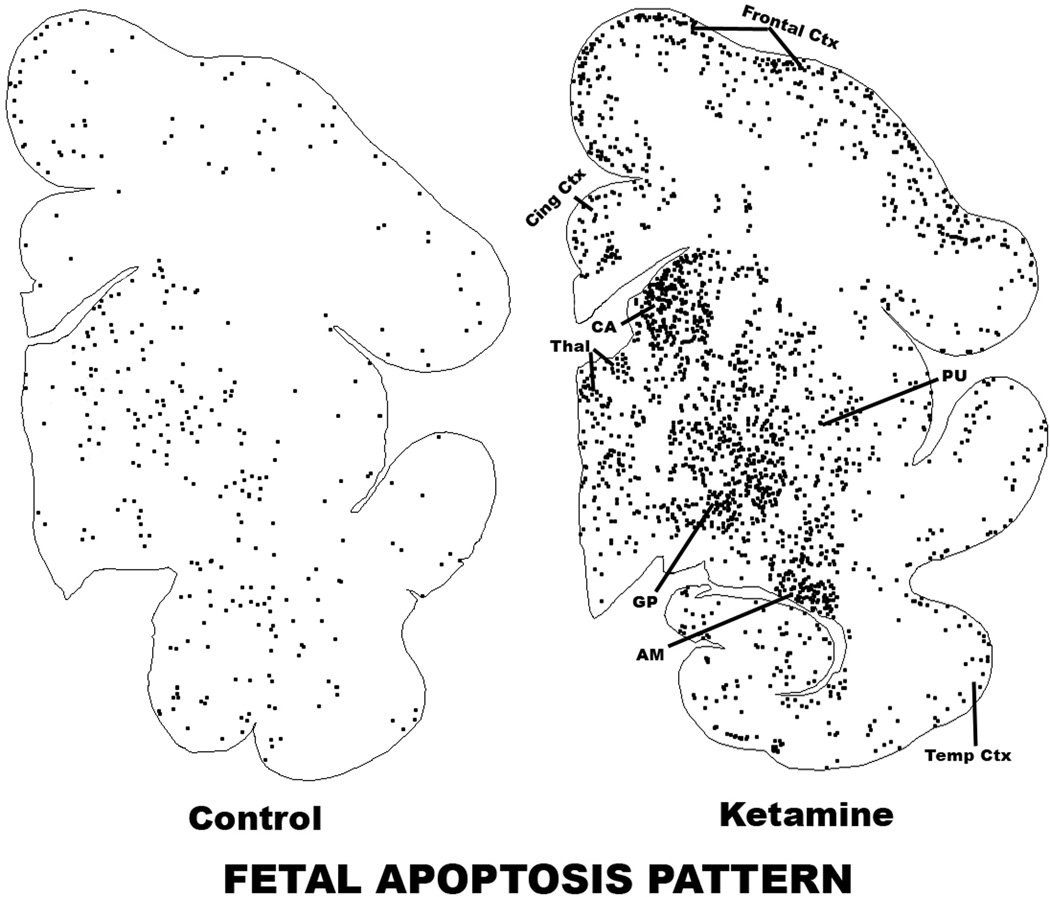

The pattern of augmented neuroapoptosis in the ketamine-exposed fetal brains was widespread. Brain regions preferentially affected were the cerebellum, brain stem, inferior and superior colliculi, several thalamic nuclei, caudate nucleus, putamen, globus pallidus, nucleus accumbens, several neuronal groups in the hypothalamus and basal forebrain, all divisions of the neocortex and several limbic cortical regions, with the notable exception of the hippocampus, which showed very little effect. The most severely affected regions were the cerebellum, caudate nucleus, putamen and nucleus accumbens. The pattern of neuroapoptosis induced by ketamine in the fetal brain is illustrated in figures 2 and 3. The histological appearance of neurons undergoing apoptosis in the NHP fetal brain is illustrated in figures 4 and 5.

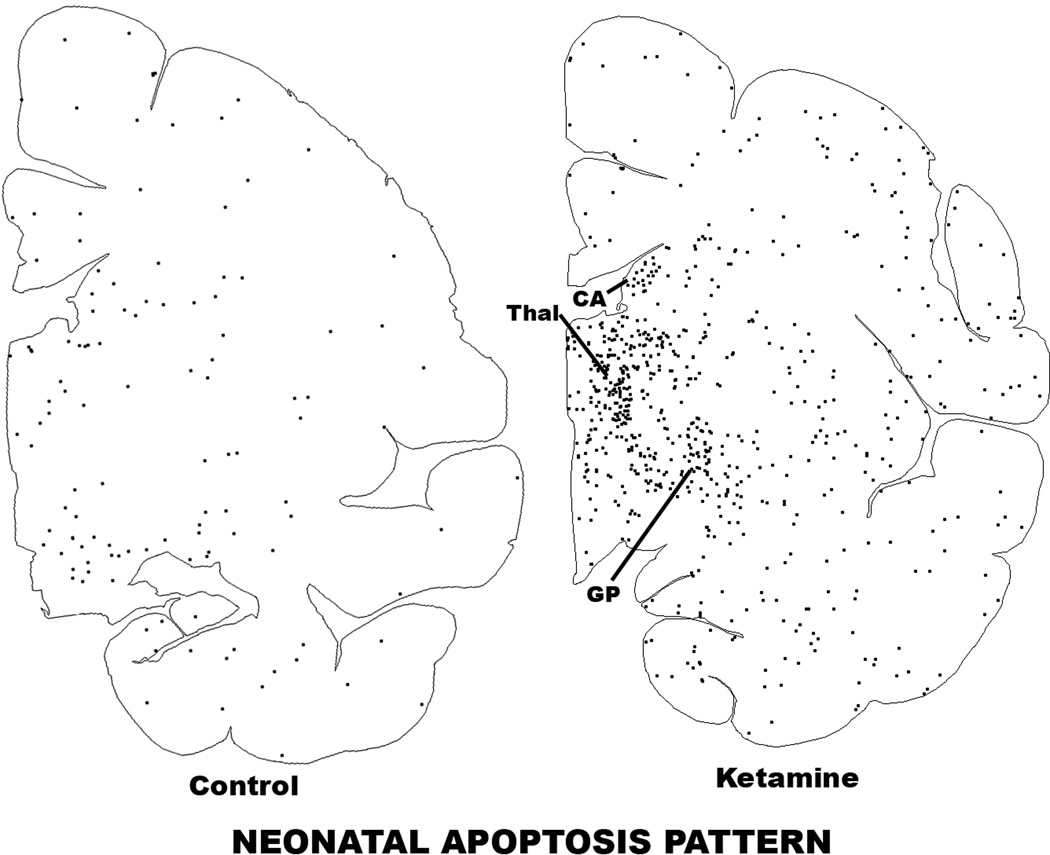

Figure 2.

Computer plot depicting the pattern of neuroapoptosis in ketamine-exposed versus control fetal macaque brains. These sections display several gray matter zones, including frontal, cingulate (Cing) and temporal (Temp) cortices, thalamus (Thal), caudate nucleus (CA), putamen (PU), globus pallidus (GP) and amygdala (AM). An outline of each section was sketched into the computer and the location of each activated caspase-3-stained neuron was marked by a black dot. The pattern of neuronal staining in the control brain due to natural neuroapoptosis is similar to the pattern in the ketamine-exposed brain, but stained neuronal profiles in the former are sparse and in the latter are abundant and heavily concentrated in regions such as the frontal cortex, thalamus, caudate nucleus, globus pallidus and amygdala.

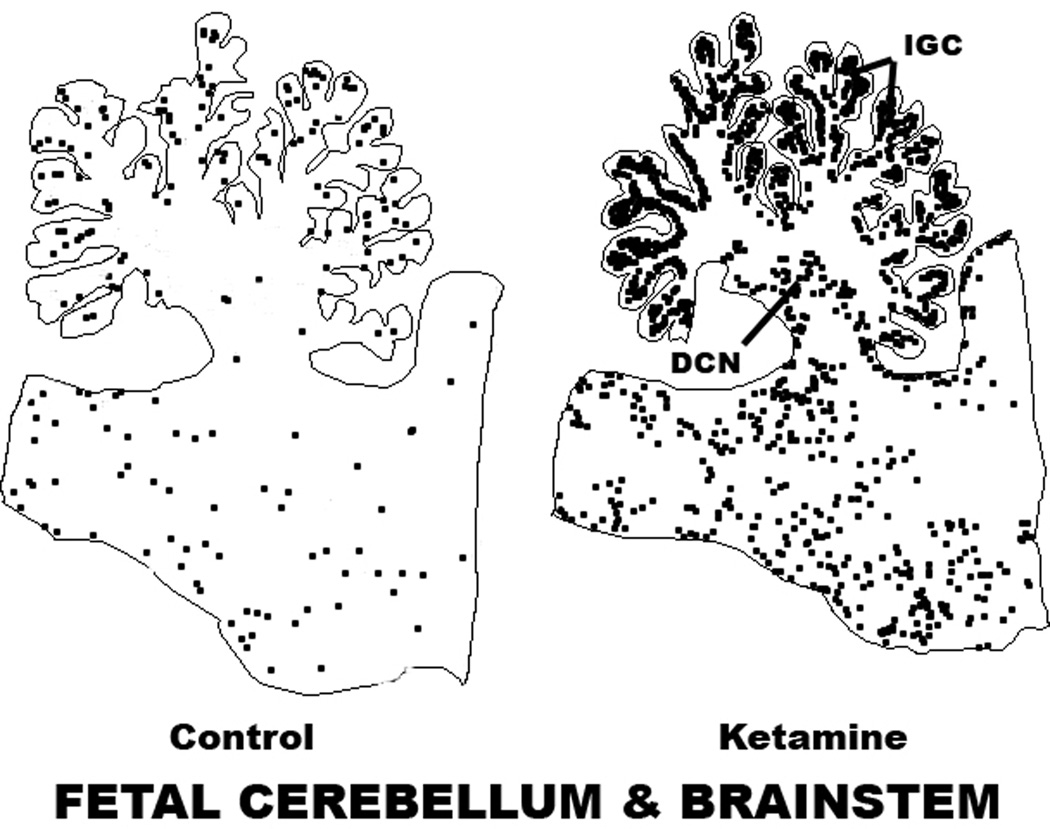

Figure 3.

Computer plot showing the pattern of neuroapoptosis in sagittal sections of the cerebellum and brain stem of ketamine-exposed versus control fetal macaque brains. The apoptotic profiles in the cerebellar folia are in the internal granule cell (IGC) zone and those at the base of the cerebellum are in the region of the deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN).

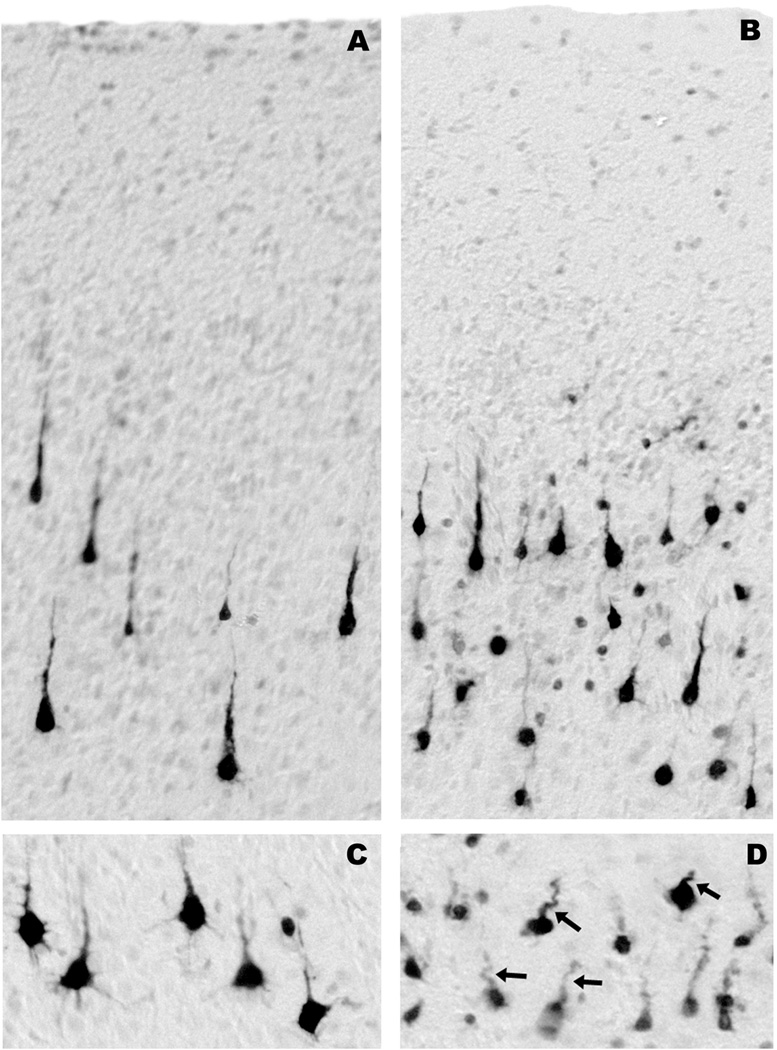

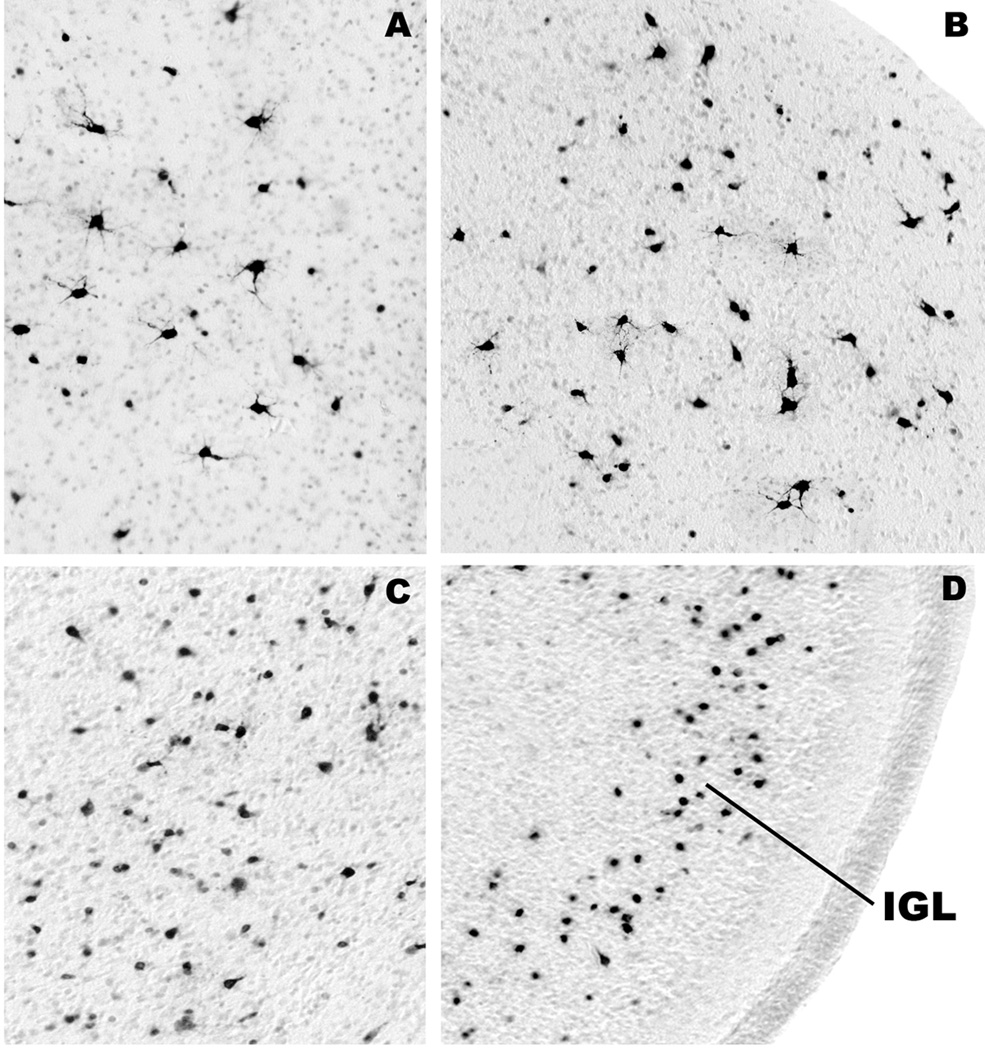

Figure 4.

All panels are from fetal brains harvested 3 h after 5 h exposure to ketamine. They display the histological appearance of activated caspase-3 (AC3)-positive neuronal profiles in layers III (A) and V (C) of the frontal cortex, layer III of the temporal cortex (B), and the pyramidal cell layer in the subiculum (D). These panels depict neurons in several stages of degeneration. Subicular neurons are in a late stage of degeneration because they are very sensitive and tend to degenerate early; this is revealed by faint and incomplete staining and by the corkscrew deformity of their apical dendrites (arrows, D). Affected neurons in layer III of the temporal cortex are heterogeneous; some degenerate early and some late. The early dying cells have degenerated beyond recognition and present as faintly stained small round dots (B). Neurons in layer V of the frontal cortex (C) are relatively resistant and have just begun to degenerate. Therefore, they are robustly AC3-positive and show very few signs of structural deformity.

Figure 5.

The histological appearance of activated caspase-3-positive neuronal profiles in the lateral septum (A), anterodorsal thalamic nucleus (B), caudate nucleus (C) and cerebellum (D) of fetal brains harvested 3 hours after 5 hours exposure to ketamine. Most of the affected neurons in the septum (A) and thalmus (B) are large multipolar neurons that are relatively resistant and, therefore, are in a relatively early stage of degeneration. The affected neurons in the caudate nucleus (C) are morphologically heterogeneous. A small cell type degenerates very rapidly and presents as a faintly stained, small, condensed, shrunken structure amidst other larger cells that degenerate on a slightly later time schedule. The most sensitive cell population in the cerebellum (D) is one that is located in the inner portion of the inner granule cell layer (IGL). These cells degenerate rapidly following exposure of either infant rodents or fetal monkeys to alcohol or anesthetic drugs. As is explained in previous publications8,39, it is not clear whether they are granule cells or other cell types that are migrating through the granule cell layer.

Neonates

On the day of the experiment the infant macaques (ketamine group [n = 4], mean age 5.7 days, 449 to 680 g body weight; control group [n = 5] mean age 5.6 days and body weight 430 to 546 g) were assigned to either receive general anesthesia or not. Intravenous induction (20 mg/kg, IV) and maintenance of ketamine anesthesia were well tolerated by all infant animals. At adequate anesthetic depth the trachea was intubated in all animals and the lungs were mechanically ventilated which allowed controlling blood gases and acid-base status within physiologic limits throughout the five hours of general anesthesia. Active warming and fluid and glucose application maintained basic homeostasis, documented by continuous intraoperative monitoring of hemodynamic variables and point-of-care laboratory results throughout the entire experimental period (table 3). Within 45 min after cessation of the ketamine infusion the infant macaques were weaned from the ventilator, extubated without complications, and maintained in an animal incubator at physiologic condition. Animals remained drowsy and were directly observed for 3 h until transcardial perfusion.

Table 3.

Physiologic Variables of Neonatal Animals (P6) during Ketamine Anesthesia and Recovery

| Time | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesia | ||||||

| Group | Baseline | 0.5 h | 2.5 h | 4.5 h | 3 h Recovery | |

| Temp | Control (n = 5) | 37.7 (37.3–38.2) | - | - | - | 37.8 (37.7–37.9) |

| (°C) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 36.5 (35.9–37.1) | 36.8 (36.8–36.8) | 38.0 (37.7–38.4) | 38.3 (37.9–39.3) | 38.0 (37.7–38.4) |

| MAP | Control (n = 5)# | - | - | - | - | - |

| (mmHg) | Ketamine (n = 4) | -# | 65 (60–76) | 50 (41–59) | 43 (35–50) | 51 (44–60) |

| HR | Control (n = 5)# | - | - | - | - | - |

| (/min) | Ketamine (n = 4) | -# | 187 (147–210) | 166 (128–218) | 163 (122–210) | 196 (160–222) |

| EtCO2 | Control (n = 5)# | - | - | - | - | - |

| (mmHg) | Ketamine (n = 4) | - | 26 (23–28) | 29 (28–30) | 28 (28-28) | - |

| pH | Control (n = 5) | 7.30 (7.27–7.34) | - | - | - | 7.31 (7.23–7.36) |

| (venous) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 7.29 (7.24–7.34) | 7.43 (7.39–7.49) | 7.33 (7.22–7.41) | 7.34 (7.29–7.37) | 7.28 (7.12–7.39) |

| PvCO2 | Control (n = 5) | 43 (39–56) | - | - | - | 40 (37–45) |

| (mmHg) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 39 (37–42) | 28 (24–36) | 33 (29–37) | 36 (30–43) | 40 (35–48) |

| PvO2 | Control (n = 5) | 25 (20–34) | - | - | - | 33 (28–40) |

| (mmHg) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 28 (26–31) | 37 (30–41) | 35 (21–41) | 33 (28–40) | 28 (25–31) |

| Hb | Control (n = 5) | 18 (16–19) | - | - | - | 15 (14–17) |

| (mg/dl) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 14 (12–15) | 12 (10–15) | 11 (9–13) | 11 (10–12) | 11 (10–13) |

| Glucose | Control (n = 5) | 92 (55–159) | - | - | - | 74 (51–95) |

| (mmol/L) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 66 (52–73) | 114 (69–233) | 131 (105–166) | 90 (60–155) | 56 (46–67) |

| Lactate | Control (n = 5) | 3.9 (1.9–5.3) | 3.1 (1.8–5.5) | |||

| (mmol/L) | Ketamine (n = 4) | 6.1 (3.3–9.5) | 2.69(1.6–4.4) | 3.2 (1.1–4.9) | 2.1 (1.6–2.8) | 3.0 (1.2–4.4) |

Data are presented as Median (range: Min – Max).

Baseline = animal awake, no sedation, hand restrained, IV access established; 3-h recovery = animal awake, residual mild sedation, hand restrained, IV access still in place; EtCO2 = end-tidal carbon dioxide; Hb = hemoglobin; HR = heart rate; MAP = mean arterial pressure (noninvasive); PvCO2 = venous carbon dioxide tension; PvO2 = venous oxygen tension; Temp = temperature (rectal).

Variables not obtained.

In the first 90 min 0.52 to 1.28 mg/kg/min of ketamine was applied to the neonatal macaques in order to achieve the desired anesthetic depth (no movement and <10% increase in heart rate/blood pressure in response to profound mosquito-clamp pinch). The total doses of ketamine per infant macaque were 92 to 280 mg/kg during the 5-h anesthesia (18.40 to 56.0 mg/kg/h). There were no adverse effects of ketamine anesthesia observed in the neonatal cohort.

Quantitative evaluation of AC3-stained sections from the P6 neonatal brains revealed that the mean (± SD) number of apoptotic neuronal profiles per brain in the four ketamine-exposed neonatal brains was 5.44 ×105 ± 1.89 ×105 and in the five control neonatal brains was 1.42 ×105 ± 0.95 ×105 (fig. 1), which equals a 3.83-fold increase in the number of apoptotic neurons in the ketamine-exposed brains compared to the brains from drug-naive controls. The difference in the mean number of apoptotic neurons between the ketamine and control groups was 4.02 ×105 (95% confidence interval, 6.29 ×105 to 1.74 ×105, p = 0.004).

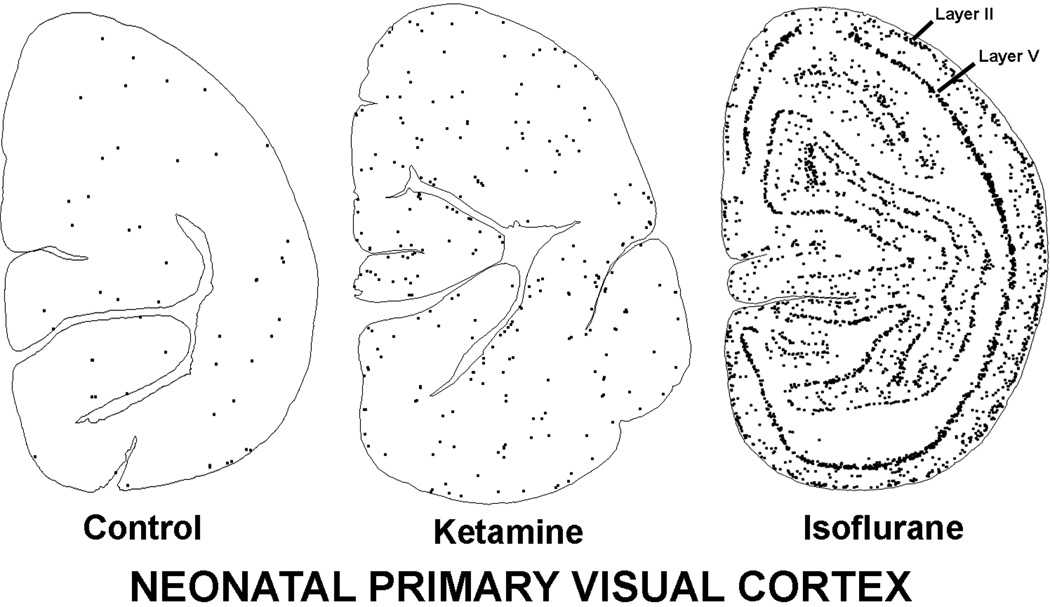

Ketamine caused a less widespread pattern and less dense concentration of neuroapoptosis in the neonatal than fetal brains. A major difference between the fetal and neonatal response to ketamine was that many of the caudal and subcortical brain regions that were preferentially affected in the fetal brains, including the cerebellum and brain stem, showed little or no neuroapoptosis response in the neonatal brains. A major exception to this rule was that the strongest neuroapoptosis response to ketamine in the neonatal brain was in the basal ganglia (caudate nucleus, putamen, nucleus accumbens, globus pallidus) and several thalamic areas (fig. 6). These same regions, although not necessarily the same neuronal populations within each region, also had a high neuroapoptosis count following ketamine exposure of fetal brains. The neuroapoptosis response in the cerebral cortex of ketamine-exposed neonates was evenly distributed across cortical regions and was only moderately increased compared to controls in most cortical regions. This distribution is different from that recently described in neonatal macaque brains exposed to isoflurane27. The apoptotic response following isoflurane exposure was most prominent in several divisions of the neocortex, especially the temporal cortex (layers II and IV) and the primary visual cortex (layers II and V). The striking difference in pattern and density of neuroapoptosis in the primary visual cortex following isoflurane exposure versus ketamine exposure is illustrated in figure 7.

Figure 6.

Computer plot revealing the pattern of neuroapoptosis in ketamine-exposed versus control neonatal macaque brains. These sections are cut through the forebrain at the same level as the fetal sections in figure 3. Although, the density of apoptotic neural profiles is decreased in the neonatal compared to the fetal brain, the pattern at both ages features a high density of apoptotic profiles in the basal ganglia, including the caudate nucleus (CA), globus pallidus (GP), and adjacent thalamus (Thal) relative to other regions of the neonatal brain.

Figure 7.

Apoptosis induced by ketamine vs. isoflurane in the neonatal primary visual cortex. The ketamine illustration is from the present study and the isoflurane illustration is reproduced from our prior publication pertaining to isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis27. The control brain has a very sparse and randomly scattered pattern of neuroapoptosis. The ketamine-exposed visual cortex has a moderately increased number of neural apoptotic profiles and they are distributed in a less random pattern. The isoflurane-exposed visual cortex is heavily studded with apoptotic neural profiles and they are organized in a distinctive laminar pattern corresponding to the location of neurons in layers II and V.

The rate of natural neuroapoptosis and of ketamine-induced neuroapoptosis in the fetal versus neonatal period is illustrated in figure 8. The rate of neuroapoptosis declines between the fetal and neonatal period for both phenomena, and the decline is more rapid for ketamine-induced than for natural neuroapoptosis. However, because the magnitude of the drug-induced phenomenon is so much higher, the two curves will perhaps approach zero at roughly the same time in the late neonatal or early juvenile period. The dashed lines with arrows represent the amount of neuroapoptosis that can be attributed to ketamine treatment at each age (8.92 ×105 for fetuses and 4.02 × 105 for neonates). The value for fetuses is 2.22 times greater than the value for neonates.

Figure 8.

The impact of ketamine treatment on neurons in the fetal versus neonatal brain is depicted in terms of the mean number of neurons affected in the brain by ketamine at each age. For comparison the mean number undergoing natural neuroapoptosis in the control brains is also illustrated. The rate of neuroapoptosis induced by ketamine declines more sharply between the fetal and neonatal period than the rate for natural neuroapoptosis. The dashed lines with arrows represent the amount of apoptosis that can be attributed to ketamine treatment at each age. The number of neurons affected by ketamine exposure in the fetal period is 2.2 times greater than in the neonatal period.

Dose effects

Ketamine anesthesia was titrated clinically to achieve a moderate anesthesia plane (see methods) and the total doses of ketamine/kg body weight varied between individuals and between the fetal and neonatal cohorts. While individual biological variability and the small number of animals preclude reaching firm conclusions regarding linearity, a linear dose-response relationship is suggested by the fact that at each age the lowest dose was associated with the lowest apoptosis count and higher doses were associated with correspondingly higher counts, with the exception of one neonate that received a high dose and had a lower than would have been predicted neuroapoptosis score (table 4).

Table 4.

Fetal and Neonatal Dose/Response Data

| Animal ID | Dose (mg/kg) | NA Density (Profiles/mm3) |

|---|---|---|

| FE 17 | 260 | 35.54 |

| FE 15 | 339 | 36.86 |

| FE 16 | 433 | 65.97 |

| Neo 13 | 92 | 5.35 |

| Neo 14 | 160 | 10.24 |

| Neo 16 | 260 | 14.00 |

| Neo 15 | 280 | 7.60 |

All neuroapoptosis (NA) values for both fetuses and neonates are consistent with a linear dose-response relationship except for Neonate 15, whose NA score is lower than theoretically would be predicted. Ketamine doses indicted for each fetus are expressed in mg/kg of the body weight of the respective dam; doses for each neonate are expressed in mg/kg body weight of the respective neonate.

DISCUSSION

It has been estimated that the minimum ketamine exposure duration for inducing neuroapoptosis in the developing NHP brain lies somewhere between 3 and 9 h20. The present findings clarify that a 5-h ketamine infusion is sufficient to induce a significant neuroapoptosis response in either the fetal or neonatal NHP brain. A comparison of the brain growth spurt curve for the rhesus macaque with that for the human6, suggests that the rhesus brain at G120 may be at a developmental stage approximately equivalent to the brain of a mid to late third trimester human fetus (or prematurely born infant), and the P6 rhesus may be equivalent to a 4–6-month-old human infant. Therefore, the period in human development to which the present data are potentially most relevant would be an 8-month interval from the middle of the third trimester of gestation to about 6 months after birth.

The total number of neurons that showed AC3 positivity as a result of ketamine exposure was more than two times greater when exposure occurred in the fetal period. This suggests that human risk for ketamine-induced neuroapoptosis may be greatest at some point in third trimester prenatal development, which corresponds in general to the range of brain ages for human infants born prematurely. Such infants are often exposed to anesthetic drugs for procedural sedation and/or surgery. Since a G120 rhesus brain equates closely with a late, but not early, third trimester human brain, this points to the need for NHP studies examining ketamine neurotoxicity at additional gestational ages corresponding to a human brain age earlier in the third trimester. Similarly, whereas all of the recent human epidemiological studies pertaining to developmental anesthesia neurotoxicity35–39 have focused on full-term infants and children, the focus of future human research should be expanded to include third trimester fetuses and prematurely born infants.

Our data indicating that ketamine, an NMDA antagonist, may be more damaging to the fetal than neonatal NHP brain, has implications in both a clinical anesthesia and a drug abuse context. Maternal abuse of drugs is the most common cause of preventable developmental brain damage in modern society. Alcohol, the most widely and frequently abused drug in human experience, which has damaged more fetal brains (Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder) than any drug in human history, is also an NMDA antagonist, as is phencyclidine (1-(1-phenylcyclohexyl)-piperidine [Angel Dust]), a dissociative anesthetic and notorious psychotomimetic drug of abuse.† Ketamine, in recent years, has become a popular drug of abuse in the United States and other regions of the world2,28–30. Our findings identify the third trimester of pregnancy as a developmental period when neurons may be at peak sensitivity to the apoptogenic action of NMDA antagonist drugs. This information is relevant to the use of ketamine to anesthetize pregnant women or premature infants41–43, and also to the maternal abuse of ketamine, phencyclidine or alcohol during this period of heightened fetal sensitivity.

A comparison of the fetal and neonatal patterns of damage induced in the macaque brain by ketamine suggests that in the fetal period caudal and some subcortical brain regions transition through their window of vulnerability, so that a number of these regions are vulnerable in the fetal but not neonatal period. A similar finding was recently reported44 for fetal macaques exposed at G120 versus at G155 (one week before term) to alcohol. It is noteworthy, however, that several subcortical brain regions, especially the basal ganglia and thalamus, were severely affected in both the fetal and neonatal period. This observation has potentially important implications, in that a deficit in neuronal mass of the basal ganglia has been emphasized in several reports as a prominent finding in children who were exposed in utero to alcohol 45,46, and the same finding was recently reported in children exposed in utero to antiepileptic drugs47. Both alcohol and antiepileptic drugs have apoptogenic properties similar to those of ketamine2–4,13,44.

The pattern of degeneration induced by ketamine in the fetal NHP brain was substantially different from the pattern induced by ketamine in the neonatal brain. This signifies that if anesthesia-induced neuroapoptosis in the primate brain gives rise to lasting neurocognitive disabilities, the nature of the disabilities will vary as a function of the time of exposure. This will complicate the task of establishing correlations between anesthesia exposure of the developing human brain with subsequent neurobehavioral disturbances, in that the disturbances will display wide ranging heterogeneity correlated not with anesthesia per se, but with age at the time of exposure. In addition, of course, duration of exposure and type of anesthetic drug and many other interacting variables will also complicate the analysis.

Our findings document important differences in the patterns of neuroapoptosis induced in the neonatal NHP brain by ketamine, as observed in the present study, versus isoflurane, as observed in a prior study27. The most prominent difference is that the isoflurane pattern was heavily concentrated in the temporal and occipital lobes where it featured a laminar pattern of degeneration affecting many neurons in layers II and IV of the temporal cortex and layers II and V of the primary visual cortex. The ketamine-exposed neonatal brains displayed a pattern more evenly and lightly distributed over various divisions of the cerebral cortex, and none of the ketamine-exposed brains showed a laminar pattern of dense degeneration selectively affecting large numbers of neurons in specific layers of the temporal and primary visual cortices.

Our findings corroborate those of Slikker et al regarding NHP susceptibility to ketamine's apoptogenic action, but some of our observations are different from theirs. They reported that in both neonatal and fetal rhesus macaques, ketamine triggered neuroapoptosis in only one brain region, the frontal cortex. Our findings document a more widespread pattern of neuroapoptosis in both the fetal and neonatal macaque brain following 5-h exposure to ketamine. We believe these divergent results can best be explained by differences in experimental protocol. For example, our methods for sampling and counting apoptotic profiles are different from theirs, and their experiments in which ketamine was found to induce neuroapoptosis are based on a prolonged time frame and ours on a much shorter time frame. They maintained the ketamine infusion for either 24 or 9 h and allowed an additional 6-h survival time before obtaining the brains for histological analysis. Thus, the total time for their experiments was either 30 or 15 h. We terminated drug exposure at 5 h and allowed an additional 3 h survival, for a total duration of 8 hours. We geared our experiments to a shorter time frame because we have observed in numerous prior studies in rodents3,5,9,11,12–14,16,19 and in NHPs exposed to alcohol44 that evidence for neuroapoptosis (caspase 3 activation) is already detectable in many brain regions within approximately 3–5 h after initiation of drug exposure. To reliably detect this rapid apoptosis response, we have found AC3 immunohistochemistry to be the best method. However, once the apoptosis cascade becomes evident by AC3 staining, it transpires rapidly to end-stage cell death. Within a 5–6 h time frame, the apoptotic profiles begin to lose immunoreactivity, undergo degradation into small fragments and are phagocytized3,11. Thus, if brains are examined at 15 or 30 h after initiation of anesthesia, it is possible to detect late-dying cells, but the most sensitive cells (those that died early) may not be detected.

Paule et al.40 have reported relatively robust and apparently permanent neurocognitive deficits in rhesus macaques following neonatal exposure to ketamine for 24 h. The human relevance of this finding is difficult to assess because of the long exposure time. Our demonstration that within a more clinically relevant exposure time, both ketamine and isoflurane induce a significant neuroapoptosis response in the developing monkey brain, clearly indicates the need for well designed research to clarify whether these more clinically relevant anesthesia exposure conditions are associated with long term neurobehavioral disturbances.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that a 5-h exposure to ketamine, an anesthetic drug with NMDA antagonist properties, is sufficient to induce a significant neuroapoptosis reaction in the developing NHP brain at either a fetal or neonatal age. The apoptotic response at the fetal age (early third trimester) was 2.2 times greater than at the neonatal age, which signifies that the third trimester of pregnancy may be a period when the primate brain is particularly sensitive to the neuroapoptogenic action of NMDA antagonist drugs. This is potentially important in a public health context because at this developmental age human fetuses and premature infants are exposed to NMDA antagonist drugs (ketamine, nitrous oxide), either alone or together with other neuroactive agents, for sedative, analgesic or anesthetic purposes, and fetuses may also be exposed to NMDA antagonists (ketamine, phencyclidine, alcohol) by mothers who abuse these drugs for recreational purposes.

Final Boxed Summary Statement.

What Is Known

Prior work has shown that sustained exposure to ketamine (e.g., 9–24 h) produces neurodegeneration in the developing rhesus macaque brain.

What is New

Shorter exposure intervals (e.g., 5 h) also produce neurodegeneration. Patterns of neuroapoptosis are different in fetal versus neonatal rhesus macaque brain, with the number of damaged cells being greater in fetal brain.

Acknowledgments

Funding support by National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; Grants HD37100, HD 052664, HD 062171, DA 05072 and RR-000163 for the operation of the Oregon National Primate Research Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Summary Statement: Fetal and neonatal rhesus macaques were exposed for 5 h to ketamine anesthesia or to no anesthesia. Histological evaluation of the brains 3 h later revealed a significant increase in neuroapoptosis in many regions of both the fetal and neonatal ketamine-exposed brains.

NSDUH Report. Substance use among women during pregnancy and following childbirth. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Rockville, Maryland. 2009; Available at: http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k9/135/PregWoSubUse.htm. Last accessed July 20, 2011.

NSDUH Report. Substance use among women during pregnancy and following childbirth. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Rockville, Maryland. 2009; Available at: http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k9/135/PregWoSubUse.htm. Last accessed July 20, 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ikonomidou C, Bosch F, Miksa M, Bittigau P, Vöckler J, Dikranian K, Tenkova T, Stevoska V, Turski L, Olney JW. Blockade of NMDA receptors and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Science. 1999;283:70–74. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ikonomidou C, Bittigau P, Ishimaru MJ, Wozniak DF, Koch C, Genz K, Price MT, Stefovska V, Hörster F, Tenkova T, Dikranian K, Olney JW. Ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration and fetal alcohol syndrome. Science. 2000;287:1056–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olney JW, Tenkova T, Dikranian K, Qin YQ, Labruyere J, Ikonomidou C. Ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing C57BL/6 mouse brain. Dev Brain Res. 2002;133:115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bittigau P, Sifringer M, Genz K, Reith E, Pospischil D, Govindarajalu S, Dzietko M, Pesditschek S, Mai I, Dikranian K, Olney JW, Ikonomidou C. Antiepileptic drugs and apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15089–15094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222550499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, Benshoff ND, Dikranian K, Zorumski CF, Olney JW, Wozniak DF. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci. 2003;23:876–882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00876.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Hum Dev. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dikranian K, Ishimaru MJ, Tenkova T, Labruyere J, Qin YQ, Ikonomidou C, Olney JW. Apoptosis in the in vivo mammalian forebrain. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:359–379. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dikranian K, Qin YQ, Labruyere J, Nemmers B, Olney JW. Ethanol-induced neuroapoptosis in the developing rodent cerebellum and related brain stem structures. Dev Brain Res. 2005;155:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olney JW, Tenkova T, Dikranian K, Muglia LJ, Jermakowicz WJ, D’Sa C, Roth KA. Ethanol-induced caspase-3 activation in the in vivo developing mouse brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;9:205–219. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young C, Klocke BJ, Tenkova T, Choi J, Labruyere J, Qin YQ, Holtzman DM, Roth KA, Olney JW. Ethanol-induced neuronal apoptosis in vivo require BAX in the developing mouse brain. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:1148–1155. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young C, Roth KA, Klocke BJ, West T, Holtzman DM, Labruyere J, Qin YQ, Dikranian K, Olney JW. Role of caspase-3 in ethanol-induced developmental neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:608–614. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tenkova T, Young C, Dikranian K, Olney JW. Ethanol-induced apoptosis in the visual system during synaptogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2809–2817. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young C, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Qin YQ, Tenkova T, Wang H, Labruyere J, Olney JW. Potential of ketamine and midazolam, individually or in combination, to induce apoptotic neurodegeneration in the infant mouse brain. Brit J Pharmacol. 2005;146:189–197. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cattano D, Young C, Straiko MMW, Olney JW. Subanesthetic doses of propofol induce neuroapoptosis in the infant mouse brain. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1712–1714. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318172ba0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma D, Williamson P, Januszewski A, Nogaro MC, Hossain M, Ong LP, Shu Y, Franks NP, Maze M. Xenon mitigates isoflurane-induced neuronal apoptosis in the developing rodent brain. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:746–753. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264762.48920.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson SA, Young C, Olney JW. Isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in the developing brain of non-hypoglycemic mice. J Neurosurg Anesth. 2008;20:21–28. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3181271850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Xue Z, Sun A. Subclinical concentration of sevoflurane potentiates neuronal apoptosis in the developing C57BL/6 mouse brain. Neurosci Lett. 2008;447:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cattano D, Straiko MMW, Olney JW. Chloral hydrate induces and lithium prevents neuroapoptosis in the infant mouse brain. Presented at the Annual Meeting of American Society of Anesthesiologists; October 17, 2008; Orlando, Florida. #A315. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wozniak DF, Hartman RE, Boyle MP, Vogt SK, Brooks AR, Tenkova T, Young C, Olney JW, Muglia LJ. Apoptotic neurodegeneration induced by ethanol in neonatal mice is associated with profound learning/memory deficits in juveniles followed by progressive functional recovery in adults. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slikker W, Jr, Zou X, Hotchkiss CE, Divine RL, Sadovova N, Twaddle NC, Doerge DR, Scallet AC, Patterson TA, Hanig JP, Paule MG, Wang C. Ketamine-induced neuronal cell death in the perinatal rhesus monkey. Toxicol Sci. 2007;98:145–158. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zou X, Patterson TA, Divine RL, Sadova N, Zhang X, Hanig JP, Paule MG, Slikker W, Wang C. Prolonged exposure to ketamine increases neurodegeneration in the developing monkey brain. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2009;27:727–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Straiko MMW, Young C, Cattano D, Creeley CE, Wang H, Smith DJ, Johnson SA, Li ES, Olney JW. Lithium protects against anesthesia-induced developmental neuroapoptosis. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:662–668. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819b5eab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanders RD, Xu J, Shu Y, Fidalgo A, Ma D, Maze M. General anesthetics induce apoptotic neurodegeneration in the neonatal rat spinal cord. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1708–1711. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181733fdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong J, Yang X, Yao W, Lee W. Lithium protects ethanol-induced neuronal apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:905–910. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Young C, Straiko MMW, Johnson SA, Creeley CE, Olney JW. Ethanol causes and lithium prevents neuroapoptosis and suppression of pERK in the infant mouse brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satomoto M, Satoh Y, Terui K, Miyao H, Takishima K, Ito M, Imaki J. Neonatal exposure to sevoflurane induces abnormal social behaviors and deficits in fear conditioning in mice. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:628–637. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181974fa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brambrink AM, Evers AS, Avidan MS, Farber NB, Smith DJ, Zhang X, Dissen GA, Creeley CE, Olney JW. Isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in the neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:834–841. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d049cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su PH, Chang YZ, Chen JY. Infant with in utero ketamine exposure. Quantitative measurement of residual dosage in hair. Pediatr Neonatol. 2010;51:279–284. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(10)60054-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albright BB, Rayburn WF. Substance abuse among reproductive age women. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2009;36:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore DG, Turner JD, Parrott AC, Goodwin JE, Fulton SE, Min MO, Fox HC, Braddick FMB, Axelsson L, Lynch S, Ribeiro H, Frostick CJ, Singer LT. During pregnancy, recreational drug-using women stop taking ecstasy (3, 4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine) and reduce alcohol consumption, but continue to smoke tobacco and cannabis: Initial findings from the Development and Infancy Study. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1403–1410. doi: 10.1177/0269881109348165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fredriksson A, Ponten E, Gordh T, Eriksson P. Neonatal exposure to a combination of N-methyl-d-aspartate and γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor anesthetic agents potentiates apoptotic neurodegeneration and persistent behavioral deficits. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:427–436. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000278892.62305.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fredriksson A, Archer T, Alm H, Gordh T, Eriksson P. Neurofunctional deficits and potentiated apoptosis by neonatal NMDA antagonist administration. Behav Brain Res. 2004;153:367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fredriksson A, Archer T. Neurobehavioural deficits associated with apoptotic neurodegeneration and vulnerability for ADHD. Neurotox Res. 2004;6:435–456. doi: 10.1007/BF03033280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stratmann G, Visrodia K, May L, Sall J, Shin Y. Effects of isoflurane on hippocampal neurogenesis in neonatal rats. Presented at the Annual Meeting of American Society of Anesthesiologists; October 20, 2008; Orlando, Florida. #A1412. [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiMaggio C, Sun LS, Kakavouli A, Burne MW, Li G. A retrospective cohort study of the association of anesthesia and hernia repair surgery with behavioral and developmental disorders in young children. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2009;4:286–291. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3181a71f11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DiMaggio C, Sun LS, Li G. Early childhood exposure to anesthesia and risk of developmental and behavioral disorders in a birth cohort of 5824 twin pairs. Presented at The IARS and SAFEKIDS International Science Symposium, International Anesthesiology Research Society 2010 Annual Meeting; March 20, 2010; Honolulu, Hawaii. #ISS-A1. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalkman CJ, Peelen LM, deJong TP, Sinnema G, Moons KG. Behavior and development in children and age at time of first anesthetic exposure. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:805–812. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819c7124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas JJ, Choi JW, Bayman EO, Kimble KK, Todd MM, Block RI. Does anesthesia exposure in infancy affect academic performance in childhood?. Presented at The IARS and SAFEKIDS International Science Symposium, International Anesthesiology Research Society 2010 Annual Meeting; March 20, 2010; Honolulu, Hawaii. #ISS-A4. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilder RT, Flick RP, Sprung J, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Mickelson C, Gleich SJ, Schroeder DR, Weaver AL, Warner DO. Early exposure to anesthesia and learning disabilities in a population-based birth cohort. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:796–804. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000344728.34332.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paule MG, Li M, Allen RR, Liu F, Zou X, Hotchkiss C, Hanig JP, Patterson TA, Slikker W, Jr, Wang C. Ketamine anesthesia during the first week of life can cause long-lasting cognitive deficits in rhesus monkeys. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2011;33:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams GD, Maan H, Ramamoorthy C, Kamra K, Bratton SL, Bair E, Kuan CC, Hammer GB, Feinstein JA. Perioperative complications in children with pulmonary hypertension undergoing general anesthesia with ketamine. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:28–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall RW, Shbarou RM. Drugs of choice for sedation and analgesia in the neonatal ICU. Clin Perinatol. 2009;36:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joselyn AS, Cherian VT, Joel S. Ketamine for labour analgesia. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010;19:122–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farber NB, Creeley CE, Olney JW. Alcohol-induced neuroapoptosis in the fetal macaque brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mattson SN, Riley EP, Sowell ER, Jernigan TL, Sobel DF, Jones KL. A decrease in the size of the basal ganglia in children with fetal alcohol syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1088–1093. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riley EP, McGee CL. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. An overview with emphasis on changes in brain and behavior. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:357–365. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ikonomidou C, Scheer I, Wilhelm T, Juengling FD, Titze K, Stöver B, Lehmkuhl U, Koch S, Kassubek J. Brain morphology alterations in the basal ganglia and the hypothalamus following prenatal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2007;11:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]