Summary

Microglia and astrocytes play essential roles in the maintenance of homeostasis within the central nervous system, but mechanisms that control the magnitude and duration of responses to infection and injury remain poorly understood. Here, we provide evidence that 5-androsten-3β,17β-diol (ADIOL) functions as a selective modulator of estrogen receptor (ER)β to suppress inflammatory responses of microglia and astrocytes. ADIOL and a subset of synthetic ERβ-specific ligands, but not 17β-estradiol, mediate recruitment of CtBP co-repressor complexes to AP-1-dependent promoters, thereby repressing genes that amplify inflammatory responses and activate Th17 T cells. Reduction of ADIOL or ERβ expression results in exaggerated inflammatory responses to TLR4 agonists. Conversely, the administration of ADIOL or synthetic ERβ-specific ligands that promote CtBP recruitment prevents experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in an ERβ-dependent manner. These findings provide evidence for an ADIOL/ERβ/CtBP-transrepression pathway that regulates inflammatory responses in microglia and can be targeted by selective ERβ modulators.

Introduction

Microglia are resident myeloid-lineage cells in the parenchyma of the central nervous system (CNS) that play essential roles in the maintenance of homeostasis and responses to infection and injury (Glass et al., 2010; Ransohoff and Perry, 2009; Streit, 2002). Under normal conditions, microglia are maintained in a quiescent state by neuron and astrocyte-derived factors (Cardona et al., 2006), and constantly survey the surrounding environment through an extensive array of ramified processes (Nimmerjahn et al., 2005). Upon detection of microbial invasion or evidence of tissue damage, microglia rapidly initiate an inflammatory response that serves to recruit the immune system and tissue repair processes. Microglia sense infection and injury through numerous pattern recognition receptors, such as toll-like receptors (TLR), that regulate the activities of NF-κB, AP-1 and other signal-dependent transcription factors (Akira et al., 2006). These transcription factors act in a combinatorial manner to induce a robust program of gene expression that initiates innate and adaptive immune responses (Vallabhapurapu and Karin, 2009). Astrocytes also sense infection and injury, and amplify the immune reaction initiated by microglia (Saijo et al., 2009; Sofroniew and Vinters, 2010). Microglia/astrocyte activation is required for effective immune responses, but the inflammatory program that is induced by these cells also has the potential to cause neuronal dysfunction and death if inflammatory responses are not properly resolved. Deregulation of inflammatory responses by microglia and astrocytes has been suggested to contribute to the severity of several neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, HIV-associated dementia and Multiple Sclerosis (MS) (Glass et al., 2010; Perry et al., 2010; Yadav and Collman, 2009; Tiwari-Woodruff et al., 2007).

Estrogens and synthetic estrogen receptor (ER) ligands have been documented to exert anti-inflammatory effects in animal models for MS (Gold and Voskuhl, 2009; Glass and Saijo, 2010), suggesting that estrogen receptors may participate in physiological regulation of inflammation. Roles of estrogens and their receptors in the brain are particularly complex. Two members of the nuclear receptor superfamily, estrogen receptor (ER), ERα (NR3A1) and ERβ (NR3A2), bind to 17β-estradiol and activate estrogen-regulated target genes (Kuiper et al., 1996; Chang et al., 2008). ERα is highly expressed in female reproductive organs and plays major roles in mediating the reproductive and sexually dimorphic effects of estrogens in females. ERβ also regulates reproductive functions, but exhibits a distinct pattern of expression. Both ERβ and ERα are expressed in the brain, with differential levels of expression observed in specific regions (Kuiper et al., 1997; Laflamme et al., 1998). The relative expression levels and functions of ERα and ERβ in specific subsets of microglia, astrocytes and neurons have not been established.

Although the DNA binding domains (DBDs) of ERα and ERβ are highly conserved (98% identity in human), their ligand-binding domains (LBDs) exhibit less conservation (59% identity in human), and ERβ binds selectively a distinct spectrum of naturally occurring as well as synthetic and plant-derived steroids (Kuiper et al., 1997). Consistent with this, it has been possible to develop synthetic ligands that exhibit preferential affinity for ERα or ERβ (Minutolo et al., 2009). Anti-inflammatory effects of estrogens and ER-selective ligands within the CNS have been extensively evaluated in the context of experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE), an animal model of MS (Gold and Voskuhl, 2009; Tiwari-Woodruff et al., 2007; Vegeto et al., 2000). Therapeutic mechanisms include anti-inflammatory effects in antigen presenting cells as well as neurotrophic effects. Estrogen represses several pro-inflammatory mediators including cytokines, chemokines, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in dendritic cells (Gold et al., 2009) and in microglia (Vegeto et al., 2000). The protective effect of estrogen requires ERα, since it is not observed in ERα knockout mice (Gold and Voskuhl, 2009). However, treatment with the ERβ-selective ligand 2,3-bis (4-hydroxy-phenyl)-propionitrile (DPN) was also recently shown to be protective in the EAE model (Tiwari-Woodruff et al., 2007). This effect was not associated with anti-inflammatory activity, but rather was proposed to be due to ERβ ligands acting on neurons to promote survival and preserve myelination.

Here, we report that synthetic ERβ-specific ligands based on a halogen-substituted phenyl-2H-indazole core (referred to hereafter as Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl) (De Angelis et al., 2005) potently inhibit transcriptional activation of inflammatory response genes in microglia and astrocytes. This observation led to the identification of an ERβ-specific transrepression pathway that we propose is controlled endogenously by regulated production of 5-androsten-3β,17β-diol (ADIOL). 17β -hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 14 (HSD17B14), a member of HSD17B-family, converts 5-androsten-3β-ol-17-one (dehydroepiandrosterone, DHEA) to ADIOL, and the expression of HSD17B14 itself is controlled by inducers and inhibitors of inflammatory responses. Lack of this enzyme or ERβ results in exaggerated inflammatory responses in microglia and astrocytes. These findings suggest that an ADIOL-ERβ repression pathway may play roles in the maintenance of CNS homeostasis by regulating the magnitude and duration of inflammatory responses.

Results

A subset of ERβ-specific ligands inhibit inflammatory responses in microglia

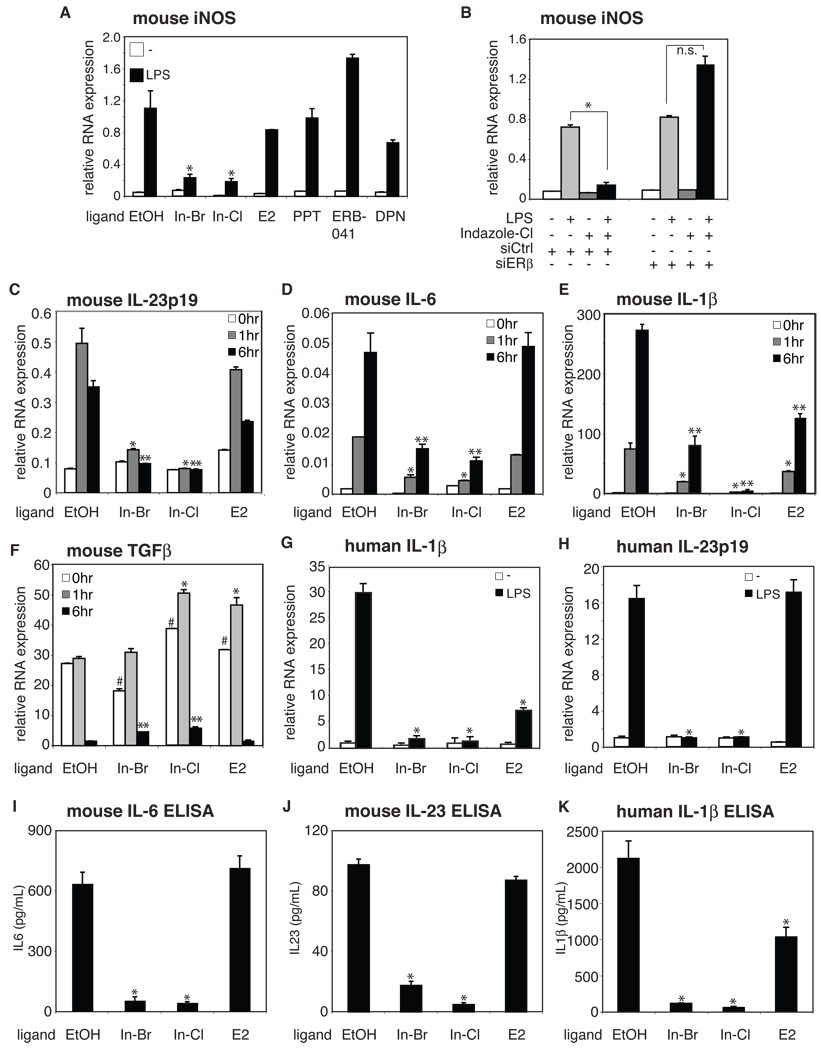

Quantitative analysis of nuclear receptor expression in primary mouse and human microglia indicated high levels of ERβ transcripts and relatively low levels of ERα transcripts (Figure S1A and B). The murine BV2 microglia cell line selectively expressed ERβ (Figure S1C), in agreement with a previous report (Baker et al., 2004). Taking advantage of BV2 cells, we first tested several ERβ-specific synthetic ligands for their effects on LPS-dependent activation of the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) gene. Notably Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl (Figure S1D) (De Angelis et al., 2005) significantly repressed the induction of iNOS mRNA, while 17β-estradiol (E2), the ERα selective agonist 4,4',4"-(4-propyl-(1H)-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl) trisphenol (PPT) (Stauffer et al., 2000), and the structurally distinct ERβ-specific ligands DPN (Meyers et al., 2001) and ERΒ-041 (Malamas et al., 2004) did not (Figure 1A). Knockdown of ERβ expression using a specific small inhibitory RNA (siRNA) abolished the Indazole-Cl-mediated repression of iNOS mRNA expression upon LPS stimulation (Figure 1B and Figure S1E). In addition, Indazoles did not repress LPS-induced iNOS expression in mouse RAW264.7 macrophages that selectively express ERα (Figure S1C and F). These results indicate that Indazole-Br- and Indazole-Cl-mediated repression is ERβ-dependent.

Figure 1. Indazole-estrogens repress inflammatory responses in microglia.

A. Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl inhibit LPS induction of iNOS mRNA 6 hr after LPS stimulation of murine BV2 microglia cells. *p < 0.01 compared to EtOH sample. B. Inhibitory effects of Indazole-Cl on LPS induction of iNOS in BV2 cells are abolished by knockdown of ERβ expression. *p < 0.01 compared to control siRNA transfected samples. C–F. Effects of Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl on LPS induction of IL-23p19 (C), IL-6 (D), IL-1β (E) and TGFβ (F) mRNAs in BV2 cells. *p < 0.01 compared to EtOH treated 1hr LPS stimulated sample, **p < 0.01 compared to EtOH treated 6hr LPS stimulated sample. G–H. Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl inhibit LPS induction of IL-1β (G) and IL-23p19 (H) mRNAs (black bar) in human primary microglia cells. *p < 0.01 compared to 1 hr LPS + EtOH-stimulated sample, *p < 0.01 compared to 6 hr LPS + EtOH-stimulated sample. I–K. Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl inhibit LPS-induced secretion of mouse IL-6 (I), mouse IL-23 (J) and human IL-1β 24hr after stimulation of corresponding primary mouse and human microglia cells as determined by ELISA. *p < 0.01 compared to EtOH treated sample. Error bars represent SD. In-Br and In-Cl are Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl, respectively. E2 is 17β-estradiol. See also Figure S1.

Several lines of evidence suggest that Th17 T cells play essential roles in focal autoimmune diseases including MS (Korn et al., 2009; Littman and Rudensky, 2010). The differentiation and activation of Th17 T cells requires specific combinations of cytokines provided by antigen presenting cells such as Transforming growth factor (TGF)β, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β and IL-23 for mice (Ghoreschi et al., 2010; Korn et al., 2009; Littman and Rudensky, 2010). Since microglia have been suggested to perform an essential role in the onset of EAE (Heppner et al., 2005) and estrogen played important roles to modify MS/EAE (Gold and Voskuhl, 2009; Vegeto et al., 2008), we tested whether Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl could repress those cytokines required for the differentiation and activation of Th17 T cells. In BV2 cells, Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl significantly repressed the mRNA expression of IL-23p19 (Figure 1C), IL-6 (Figure 1D) and IL-1β (Figure 1E) that are required for the differentiation and activation of Th17 T cells, but not TGFβ, which is important also for the differentiation of anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells (Tregs) (Figure 1F) (Littman and Rudensky, 2010). Indazole-Cl repressed IL-6 expression with an EC50 value of ~ 30–100 nM in BV2 cells (Figure S1G). Similarly, Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl repressed IL-23p19 and IL-6 in primary mouse microglia cells (Figure S1H and I). It was reported that IL-1β, but not IL-6, is required for the differentiation of human Th17 cells (Acosta-Rodriguez et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 2007). Therefore, we also tested whether the Indazoles repressed these cytokines in human microglia cells. Indazoles significantly repressed the mRNA expression of IL-1β (Figure 1G) and IL-23p19 (Figure 1H) to a greater extent than 17β-estradiol. In contrast, 17β-estradiol, but not Indazoles, suppressed expression of TGFβ in human primary microglia (Figure S1J). Next, we tested ERβ-dependency of Indazole-mediated repression of IL-1β, using siRNAs specific for ERβ and ERα. Transfection of siRNAs specifically targeting ERβ abolished Indazole-Cl-mediated repression of IL-1β (Figure S1K–M). In contrast, transfection of siRNAs against ERα did not show any reversal of Indazole-Cl-mediated repression. Thus, Indazole-Cl-mediated repression of pro-inflammatory genes in human microglia cells is also mediated by ERβ.

Finally, we measured cytokine secretion by mouse and human microglia cells by ELISA. Consistent with mRNA data, the production of IL-6 and IL-23 were strongly induced by LPS stimulation, and both Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl significantly inhibited their secretion (Figure 1I and J), with corresponding effects on IL-1β in human microglia (Figure 1K). These data indicate that, in contrast to 17β-estradiol, Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl act to strongly suppress the production of pro-inflammatory mediators in response to LPS, including those required for the differentiation and activation of Th17 T cells.

A subset of ERβ-specific ligands inhibit inflammatory responses in astrocytes

Astrocytes also contribute to inflammatory responses and have been reported to be a major source of BAFF (also known as BLyS/TNFSF13B) (Krumbholz et al., 2005), which supports the survival of potential auto-reactive B cells (Mackay and Browning, 2002). Since both human and mouse primary astrocytes express high levels of ERβ (Figure S2A and B), we next examined whether the Indazoles repressed inflammatory responses in these cells. Activated mouse and human astrocytes upregulated mRNA expression of BAFF when stimulated by IL-1β, consistent with previous reports, and Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl, but not 17β-estradiol, significantly repressed this response (Figure 2A and D). Similarly, Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl suppressed IL1β-induced expression of IL-23p19 and iNOS mRNAs in mouse and human astrocytes (Figure 2B, C, E and F). Although, the expression of ERα in astrocytes is significantly lower than ERβ, we confirmed that Indazole-mediated repression was indeed ERβ-dependent by knocking down ERα or ERβ expression using specific siRNAs (Figure S2C). As shown in Figure 2G, knockdown of ERβ expression, but not ERα expression, reverted Indazole-Cl-mediated repression of BAFF mRNA expression. Notably, siRNA knockdown of ERβ resulted in a marked increase in induced BAFF expression. Finally, the Greiss reaction was used to determine effects of ERβ ligands on IL-1β-induced NO production. Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl, but not 17β-estradiol, inhibited IL-1β-induced production of NO in human astrocytes (Figure 2H).

Figure 2. Indazole-estrogens repress inflammatory responses of astrocytes.

A–C. Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl inhibit IL-1β-dependent induction of BAFF (A), IL-23p19 (B) and iNOS (C) mRNAs in primary mouse astrocytes. *p < 0.01 compared to EtOH treated IL1β stimulated sample, **p < 0.01 compared to EtOH treated 6 hr LPS stimulated sample. D–F. Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl inhibit IL-1β-dependent induction of BAFF (D), IL-23p19 (E) and iNOS (F) mRNAs in primary human astrocytes. **p < 0.01 compared to EtOH treated 6 hr IL-1β stimulated sample. # p < 0.01 compared to EtOH treated non-stimulated sample. G. siRNA-mediated knockdown of ERβ in astrocytes results in exaggerated BAFF expression in response to IL1β and abolishes the inhibitory effects of Indazole-Cl. H. Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl inhibit IL1β-dependent production of nitric oxide (NO) by human primary astrocytes as determined by the Greiss reaction. *p < 0.01 compared to EtOH treated and IL-1β stimulated sample. Error bars represent SD. See also Figure S2.

Synthetic and endogenous ERβ modulators prevent EAE in mice

To determine whether Indazoles could inhibit inflammation in the brain, we monitored the effect of Indazole-Cl treatment on the expression of pro-inflammatory genes in the substantia nigra following injection of LPS into the peritoneal cavity (Figure 3A), which induces both systemic and CNS inflammation (Bhaskar et al., 2010). Indazole-Cl treatment suppressed induction of IL-6 in the substantia nigra (Figure 3A), but did not suppress iNOS induction in the bone marrow (Figure S3A), consistent with high expression of ERβ in microglia and astrocytes, but low expression in myeloid cells. Based on the ability of Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl to repress induction of factors in microglia that promote Th17 T cell differentiation and activation, and the established roles of microglia in the onset of EAE (Heppner et al., 2005), we also evaluated effects of Indazole-Cl on development of EAE. Female C57BL/6 mice (WT mice) without oophorectomy were immunized with MOG35–55 peptide in the presence of complete Freund adjuvant and pertusis toxin, following an aggressive protocol (Stromnes and Goverman, 2006). After about 3 weeks of immunization with peptide, mice treated with ethanol (vehicle) showed severe signs of EAE. In contrast, Indazole-Cl treated mice showed no obvious signs or limited paralysis only in tails (Figure 3B). The therapeutic effect of Indozole-Cl required ERβ, as it had no effect on the severity of EAE in ERβ−/− mice (Figure 3B). Consistent with in vitro data (Figure 1 and 2), Indazole-Cl treatment of WT EAE-induced mice resulted in the reduction of Th17 T cells (Figure S3B).

Figure 3. Indazole-Cl and ADIOL exert anti-inflammatory effects in vivo and inhibit EAE dependent on ERβ.

A. Systemic administration of Indazole-Cl (approximately 2.4 µmol/kg/day) blocks the ability of LPS injection (10 mg/kg) to induce IL-6 expression in the substantia nigra (n=4/group). Data are representative of three independent experiments. B. Indazole-Cl (2.4 µmol/kg/day) inhibits development of EAE in wild-type female mice, but not in ERβ knockout female mice. Clinical scores are indicated for age matched wild-type mice treated with EtOH (n=24, black dashed line), wild-type mice treated with Indazole-Cl treated (n=24, black solid line), ERβ−/− mice treated with EtOH (n=8, red dashed line) and ERβ−/− mice treated with Indazole-Cl (n=8, red solid line) (0 = no evidence of disease, 4 = moribund. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for immunization protocol and scoring system). Data are representative of three independent experiments. C. Indazole–Cl induces partial remission of established EAE. EAE was induced and scored as in B, but Indazole-Cl (n=8) or EtOH vehicle (n=8) treatments were not initiated until mice exhibited a clinical score of 1 (~day 10). Data are representative of two independent experiments.. D. A screen of endogenous steroids identifies ADIOL as a suppressor LPS induction of IL-6 in BV2 cells. *p < 0.01 compared to EtOH treated 6 hr LPS stimulated sample. E. Structure of ADIOL. F. Systemic administration of ADIOL (2.4 µmol/kg/day) blocks the ability of LPS injection (10 mg/kg) to induce IL-6 expression in the substantia nigra (n=5/group). Data are representative of two independent experiments. G. ADIOL (2.4 µmol/kg/day) inhibits development of EAE in wild-type female mice, but not in ERβ knockout female mice. Age matched wild-type mice treated with EtOH (n=8, black dashed line), wild-type mice treated with ADIOL (n=8, black solid line), ERβ−/− mice treated with EtOH (n=8, red dashed line) and ERβ−/− mice treated with ADIOL (n=8, red solid line) were scored for clinical severity as in B. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Error bars represent SD. See also Figure S3.

Although ERβ−/− mice did not exhibit more severe disease than WT mice in these studies, the aggressive immunization protocol might have precluded measurement of a difference in sensitivity. To address this possibility, a second series of studies was performed using a less aggressive immunization protocol that produced mild tail paralysis in WT animals. In these experiments, ERβ−/− mice still developed severe disease, indicating that loss of ERβ increases susceptibility to EAE (Figure S3C). Finally, to test the potential clinical utility of Indazole-Cl treatment, studies were performed using the aggressive immunization protocol in which treatment was not initiated until after animals exhibited signs of disease (approximate clinical score of 1) (Figure 3C). Both Indazole-Cl-treated and vehicle-treated animals continued to worsen for the next three to four days. Thereafter, treated animals exhibited significant improvement, while untreated animals developed increasingly severe disease, indicating that Indazole-Cl can promote resolution of established inflammation after it has been established.

ADIOL is an endogenous ERβ ligand and controls inflammation in microglia

Although 17β-estradiol binds to ERβ and stimulates its transcriptional activities on positively regulated genes (Kuiper et al., 1996) it was much less effective at inhibiting inflammatory responses than Indazole-Br or Indazole-Cl. This observation raised the question of whether endogenous steroids other than 17β-estradiol might act similarly to Indazole-Br or Indazole-Cl to effect ERβ-mediated repression of inflammatory response genes in microglia and astrocytes. To address this question, we screened a panel of naturally occurring steroids reported to bind ERβ (Kuiper et al., 1997) for the ability to suppress induction of IL-6 in microglia upon LPS stimulation (Figure 3D) as well as synthetic or plant plant-derived steroids (Figure S3D). Although most of these molecules had no activity, ADIOL (5-androstene-3β,17β-diol), the synthetic ligand 4-estren-17β-ol-3-one (19-nortestosterone) and the non-steroidal ligand coumestrol exerted substantial repressive effects, while DHEA (5- androsten-3β-ol-17-one, dehydroepiandrosterone) and 5α-androstan-3β,17β-diol had weak activity.

We focused our attention on ADIOL (Figure 3E) because it can be generated from its precursor DHEA in microglia by reduction of the 17 keto group (Jellinck et al., 2007). In addition to suppressing activation of IL-6, ADIOL also inhibited the expression of IL-1β upon LPS stimulation of human microglia (Figure S3E), and the expression of iNOS mRNA in mouse astrocytes when cells were stimulated by IL-1β (Figure S3F). In microglia, ADIOL repressed induction of IL-6 mRNA transcription with an IC50 of ~30–100 nM (Figure S3G). ADIOL-mediated repression of inflammation was dependent on ERβ, since siRNA against ERβ abolished the repression of IL-23p19 in microglia (Figure S3H). ADIOL also repressed the expression of IL-6 in the substantia nigra following LPS injection into peritoneal cavity, indicating that ADIOL can repress microglia-mediated inflammation in vivo (Figure 3F). Next we evaluated the ability of ADIOL to repress the signs of EAE. Although less efficacious than Indazole-Cl, ADIOL also suppressed signs of EAE in an ERβ-dependent manner (Figure 3G). These findings suggest that ADIOL is a steroid with ERβ-modulatory activities similar to those of Indazole-Cl and Indazole-Br.

Regulated production of ADIOL by HSD17B14

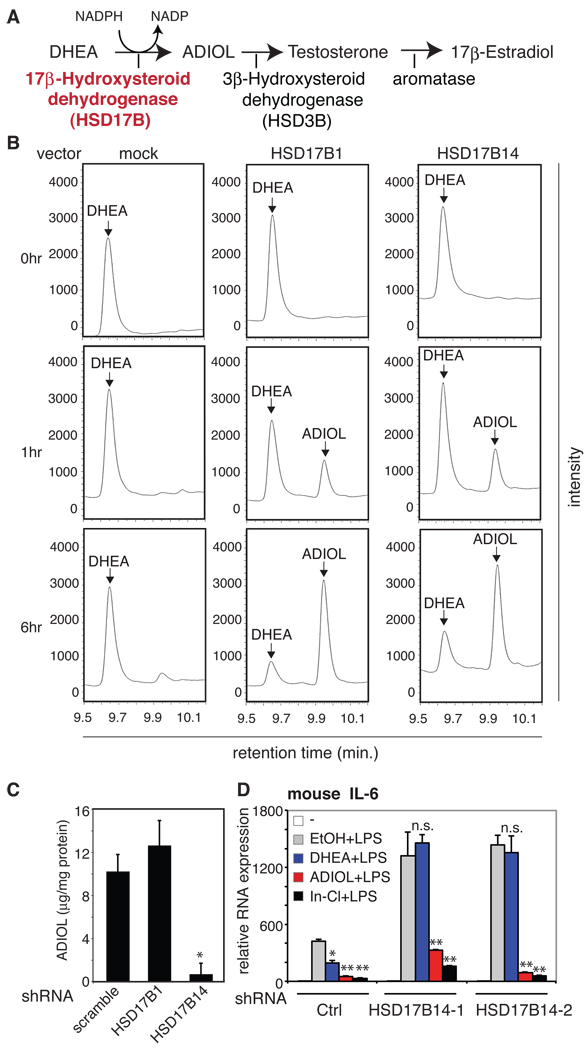

The conversion of DHEA to ADIOL requires the enzymatic activities of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases (17β-HSD, HSD17B) (Figure 4A) (Moeller and Adamski, 2009). HSD17B1 was previously reported to mediate the conversion of DHEA to ADIOL (Lin et al., 2006). However, there are at least 14 different members of the 17β-HSD family identified in humans and mice, and some of them could also potentially convert DHEA to ADIOL (Moeller and Adamski, 2009). ADIOL is converted by 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/Δ5, Δ4 isomerase (3β-HSD, HSD3B) to testosterone, and finally to estradiol by aromatase (Figure 4A) (Simard et al., 2005). Mouse and human microglia express most of the 17β-HSDs to variable extents (Figure S4A and B, respectively). Among these, HSD17B14 is highly expressed and is located on human chromosome 19q13, which has been identified as an MS susceptible locus (Bonetti et al., 2009; Wise et al., 1999).

Figure 4. HSD17B14 mediates ADIOL generation in BV2 microglia cells and regulates inflammatory responses.

A. A partial scheme of the biosynthesis and metabolism of ADIOL. B. HSD17B14 mediates conversion of DHEA to ADIOL. COS-1 cells were transfected with the indicated expression vectors, using HSD17B1 as a positive control, and the products of DHEA conversion were monitored by gas chromatography at 0, 1 and 6 hr. Retention times for DHEA and ADIOL standards are indicated. C. Knockdown of HSD17B14 in BV2 cells by stable transduction with a lentiviral vector directing expression of a specific shRNA inhibits conversion of DHEA to ADIOL. ADIOL levels in media were quantified 24 hr after addition of DHEA. D. Stable knockdown of HSD17B14 using two different shRNAs blocks the ability of DHEA, but not ADIOL or Indazole-Cl, to suppress LPS induction of IL-6 mRNA in BV2 cells. Cells were pre-treated with the indicated ligands for 1 hour except for DHEA, which was added 6 hours prior to LPS stimulation. *p < 0.01 compared to EtOH treated and LPS stimulated sample. Error bars represent SD. See also Figure S4.

17β-HSD type 14 (HSD17B14) is a newly identified member of the 17β-HSD family initially shown to covert estradiol to estrone (Lukacik et al., 2007). To investigate whether HSD17B14 is also able to convert DHEA to ADIOL, COS-1 cells that do not exhibit endogenous activity to convert DHEA to ADIOL (Figure 4B, left column) were transiently transfected with expression vectors for HSD17B1 or HSD17B14. Then cells were pulsed with DHEA and conversion to metabolites was monitored over time by gas chromatography (GC). Expression of HSD17B1 efficiently catalyzed conversion of DHEA to a product that exhibited an identical retention time to that of an ADIOL standard, consistent with the previously established enzymatic activity of HSD17B1 (Figure 4B, middle panel). As shown in Figure 4B (right column), expression of HSD17B14 at similar proteins levels (Figure S4C) generated a product with an identical retention time with similar efficiency. Importantly, the supernatants from HSD17B1 and B14-expressing cells, but not from mock-transfected cells, repressed the expression of IL-6 upon LPS stimulation in BV2 microglia cells in a manner similar to that of ADIOL (Figure S4D). Next, to investigate whether HSD17B14 might contribute to conversion of DHEA into ADIOL in microglia cells, we generated stable BV2 microglia cell lines expressing specific short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) against HSD17B14 (shHSD17B14), HSD17B1 (shHSD17B1) or scramble control (shCtrl) using lentivirus vectors (Figure S4E). Knockdown of HSD17B14, but not HSD17B1, significantly reduced the conversion of DHEA to ADIOL (Figure 4C). In addition, knockdown of HSD17B14 resulted in greatly exaggerated responses to LPS and abolished the ability of DHEA to suppress LPS induction of IL-6 mRNA (Figure 4D). In contrast, ADIOL and Indazole-Cl suppressed LPS induction of IL-6 in all three cell lines. Collectively, these findings suggest that HSD17B14 can efficiently catalyze the production of ADIOL from DHEA in microglia cells.

To further investigate the role of HSD17B14 in controlling ERβ activity in microglia, we compared the consequences of knocking down HSD17B14, HSD17B1 and ERβ on the magnitude and duration of the response to LPS. Knockdown of ERβ and HSD17B14, but not HSD17B1, increased and prolonged the induction of IL-23p19 (Figure 5A) and IL-6 (Figure S5A) mRNAs. Notably, HSD17B14 mRNA expression was down-regulated in mouse and human microglia by LPS treatment (Figure 5B and C). Consistent with this, ADIOL conversion was decreased following LPS stimulation of microglia cells (Figure 5D). Expression of HSD17B14 was also down-regulated by IL-1β in mouse and human astrocytes (Figure S5C and D, respectively). Conversely, LPS induced expression of the major 3β-HSDs expressed in mouse and human microglia (Figure S5D and E). Interestingly, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 up-regulated the expression of HSD17B14 in mouse and human microglia (Figure 5E and F).

Figure 5. HSD17B expression is regulated by pro- and anti-inflammatory stimuli.

A. Knockdown of ERβ and HSD17B14, but not HSD17B1, results in exaggerated and prolonged induction of IL-23p19 mRNA in LPS-treated BV2 cells. B, C. LPS treatment of primary mouse (B) and human (C) microglia cells results in down-regulation of HSD17B14 expression. *p < 0.01 and **p < 0.001 compared to non-stimulated sample. D. LPS treatment of BV2 cells suppresses production of ADIOL. *p < 0.001 compared to non-stimulated sample. E, F. IL-10 induces expression of HSD17B14 mRNA in primary mouse (E) and human (F) microglia. *p < 0.01 compared to non-stimulated sample. G. 17β estradiol (E2) inhibits ADIOL repression of IL6 in LPS-treated BV2 cells. *p < 0.01 compared to ADIOL + LPS alone. In all panels, error bars represent SD. See also Figure S5.

The observation that 17β-estradiol inefficiently induced anti-inflammatory activities of ERβ in microglia and astrocytes, but binds to ERβ with a higher affinity than ADIOL (Kuiper et al., 1997) raised the possibility that it could antagonize ERβ-mediated repression of inflammatory response genes. Consistent with this possibility, 17β-estradiol inhibited ADIOL suppression of IL-6 induction, with an IC50 value of ~ 0.1µM, in accord with the relative affinities of 17β-estradiol and ADIOL for ERβ (Figure 5G).

ERβ-mediated repression is initiated by tethering to cFos

A major question raised by these observations was the molecular basis for differential activities of 17β-estradiol and the Indazoles and ADIOL. Nuclear receptors can act as transcriptional repressors by direct interactions with specific DNA sequences in target genes or by transrepression mechanisms involving tethering to other transcription factors that are specifically bound to target gene promoters (Glass and Saijo, 2010). To test which of these was used by ERβ to suppress inflammatory response genes, we mutated the DNA binding domain (DBD) of ERβ so that it could not bind to estrogen responsive element (ERE) sequences. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with wild-type ERβ or DBD-mutant expression plasmids together with siRNAs directed against ERα to prevent any spurious effects of ERα. The DBD-mutant of ERβ was unable to activate an ERE-luciferase reporter gene as expected (Figure S6A), but was able to repress induction of iNOS-luciferase by LPS (Figure 6A), consistent with a transrepression mechanism. Next, we looked for potential transcription factors that ERβ could tether to on target gene promoters. Among the factors evaluated, ERβ was found to co-immunoprecipitate with cFos upon LPS stimulation in BV2 cells (Figure 6B). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays demonstrated that ERβ and cFos were recruited to the IL-23p19 promoter in BV2 cells in response to LPS (Figure 6C). ERβ was not recruited to the promoter in cFos knock-down BV2 cells (Figure S6B), consistent with a tethering-dependent mechanism.

Figure 6. ERβ tethers to cFos in a protein kinase A-dependent manner.

A. Sequence-specific DNA binding is not required for ERβ-mediated repression. RAW264.7 cells were transfected with a vector directing expression of a DBD-mutant of ERβ and a specific siRNA directed against ERα. Cells were stimulated with LPS in the presence of the indicated ligands and iNOS-promoter activity was measured by luciferase-reporter assay. *p < 0.01 compared to EtOH treated sample. B. LPS stimulates the interaction of ERβ with cFos in BV2 cells. Lysates of BV2 cells stimulated with LPS for the indicated times were immunoprecipitated with anti-ERβ antibody, and western blots were developed with anti-cFos antibody. C. ERβ is recruited to the IL-23p19 promoter coincident with cFos as detected by ChIP assay. D. LPS treatment of BV2 cells induces phosphorylation of the protein kinase A (PKA) substrate S362 of cFos. E. Protein kinase A is required for Indazole-Cl-dependent repression. Expression of IL-6 mRNA 6hr after LPS stimulation was determined in BV2 cells stably expressing a control shRNA or shRNAs directed against the α and β PKA catalytic subunits. Error bars represent SD. *p < 0.01. F. Knockdown of the PKA-α and β catalytic subunits abolishes LPS-induced interaction of ERβ with cFos as determined by co-immunoprecipitation assay as in D. G. Phosphorylation of cFos at S362 is required for LPS-induced interaction with ERβ. Lentivirus carrying HA-tagged wild-type (WT), S352A and S362E mutant cFos were infected into BV2 cells. Cells were stimulated with LPS for 30 minutes and whole cell extracts were analyzed by immuno-precipitation with α - ERβ antibody and Western blotting for HA. See also Figure S6.

We next investigated specific signals that might be required for inducing this interaction. cFos is known to be phosphorylated by several kinases such as ERK, RSK and IKKβ and protein kinase A (PKA) (Koga et al., 2009; Piechaczyk and Blanchard, 1994). Surprisingly, LPS treatment of microglia induced phosphorylation of cFos at sites that could be detected with an anti-phospho-PKA substrate antibody (Figure 6D), implicating phosphorylation by PKA. Consistent with this observation, LPS stimulation induced the activation of PKA in microglia cells (Figure S6C). IL1β and CpG DNA also activated PKA, while polyI:C did not (Figure S6E), suggesting involvement of the MyD88 pathway. To investigate whether PKA activity was important for ERβ-mediated repression, we established microglia cell lines in which shRNAs were used to knock-down expression of the two catalytic subunits of PKA, Ca and Cb (Wall et al., 2009). As shown in Figure 6E, knockdown of the catalytic subunits of PKA abolished Indazole-mediated repression of IL-6. Similarly, the stimulation-dependent binding of cFos and ERβ was abolished in these cells (Figure 6F). Finally, we identified serine 362 (S362) as the main residue in cFos targeted by PKA-phosphorylation and mutated this residue into alanine to prevent phosphorylation (S362A) or to glutamate to mimic constitutive phosphorylation (S362E). The cFos S362A mutant exhibited impaired stimulation-dependent binding to ERβ, while the S362E mutant exhibited constitutive interaction (Figure 6G). These results suggest that ERβ-mediated repression of pro-inflammatory mediators in microglia is initiated by tethering of ERβ to cFos in a PKA-mediated phosphorylation-dependent manner.

Ligand-specific recruitment of CtBP to ERβ mediates transrepression

Transrepression functions of nuclear receptors have previously been documented to involve prevention of co-repressor removal or co-repressor recruitment (Glass and Saijo, 2010). Therefore, we next performed an siRNA screen to search for co-repressors that might be required for ERβ transrepression activity in microglia cells. In this screen, siRNAs directed against either C-terminal binding protein (CtBP)1 or 2 were found to revert Indazole-mediated repression of IL-23p19 (Figure 7A) and ADIOL-mediated repression of IL-6 (Figure S7A). Thus, we speculated that ERβ recruits CtBP corepressor complexes upon ligand treatment. To confirm whether CtBP was recruited to the target gene promoters, we performed ChIP assay at the IL-23p19 and IL-6 promoter. LPS alone or Indazole alone did not recruit CtBP at the promoter region, but both LPS and Indazole (Figure 7B and S7B) or ADIOL (Figure S7C and D) induced the recruitment of CtBP at the promoter region. To confirm whether ERβ is required for the recruitment of CtBP to the promoter, we performed ChIP assay in BV2 cells infected the lentivirus carrying specific shRNA against ERβ (shERβ). As shown in Figure 7C, the recruitment of CtBP was abolished in shERβ cells upon LPS and Indazole treatment, suggesting that ERβ is acting as a beacon for CtBP.

Figure 7. CtBP is a ligand-specific corepressor of ERβ.

A. BV2 cells were transfected with specific siRNAs against CtBP1 (siCtBP1), CtBP2 (siCtBP2) or control (siCtrl), and expression of IL-23p19 mRNA was determined 1hr after LPS stimulation. *p < 0.01 compared to siCtrl samples. B. CtBP1/2 are recruited to the IL-23p19 promoter in response to the combination of Indazole-Cl plus LPS (circle, black solid line) as determined by ChIP assay. For Indazole-Cl plus LPS treatment conditions, cells were pre-treated with Indazole-Cl for 1hr followed by LPS for the indicated times. C. Recruitment of CtBP to the IL-23p19 promoter requires ERβ. BV2 cells transduced with shRNA against ERβ (shERβ, solid line) or control (shCtrl, dash line) were pre-treated with Indazole-Cl for 1hr followed by LPS stimulation for the indicated times prior to ChIP assay using anti-CtBP. Data are shown as %input. D. Ligand dependent binding of CtBP and ERβ. BV2 cells were stimulated with LPS, 17β-estradiol (E2), Indazole-Cl and ADIOL for 30 minutes. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-ERβ antibody. IP samples and inputs were developed with anti-CtBP antibody. E. Model for ERβ-mediated repression. See Discussion for details. See also Figure S7.

Importantly, CtBP could be co-immunoprecipitated with ERβ in microglia cells that were stimulated by Indazole-Cl and ADIOL, which induced the repressive function of ERβ, but not by 17β-estradiol, which did not stimulate transrepression activity of ERβ in microglia (Figure 7D). Although LPS stimulation was required to promote interaction of ERβ with cFos, it was not required for the interaction between ERβ and CtBP in microglia (Figure 7D). These observations suggest that the selective ability of Indazole-Cl/Br and ADIOL to recruit CtBP complexes to ERβ provides a molecular explanation for their differential effects on inflammatory gene expression.

Discussion

ERα and ERβ activate target genes in response to 17β-estradiol and both are considered to be physiologic estrogen receptors (Minutolo et al., 2009; Pettersson and Gustafsson, 2001). Although ERα and ERβ have highly conserved DNA binding domains, recent studies have shown that there are significant differences in the chromatin binding sites that they occupy upon stimulation by 17β-estradiol or other hormonal ligands and the genes that they regulated (Chang et al., 2008; Grober et al., 2011). In addition, variation in their respective ligand-binding cavities confers overlapping but distinct ligand-binding properties (Kuiper et al., 1997; Minutolo et al., 2009). These differences have been exploited for the development of numerous synthetic ligands that exhibit marked preferences for binding to ERα or ERβ (Minutolo et al., 2009). In most cases, functional evaluation of these ligands has been carried out to characterize their ability to positively regulate estrogen-responsive reporter genes (Meyers et al., 2001; Stauffer et al., 2000) or endogenous genes (Chang et al., 2008). The present studies are based on the serendipitous observation that two ERβ-specific ligands based on a halogen-substituted phenyl-2H-indazole core (De Angelis et al., 2005) potently suppressed transcriptional activation of TLR4-responsive genes in microglia, while 17β-estradiol and, in particular, a number of other ERβ-selective ligands did not. Notably, Indazole-Br and Indazole-Cl suppressed production of cytokines by activated microglia and astrocytes that promote Th17 cell differentiation and activation, and Indazole-Cl potently inhibited signs of EAE in mice in an ERβ-dependent manner and reversed established disease.

These findings raised the question of whether Indozole-Br and Indazole-Cl might be mimicking the activities of endogenous sterols other than 17β-estradiol that function to regulate the transrepression activities of ERβ. Studies of endogenous steroids that are known to bind to ERβ (Kuiper et al., 1997) resulted in the identification of ADIOL and a small set of other naturally occurring and synthetic steroids as also being able to repress induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines in microglia, raising the possibility of ERβ-dependent anti-inflammatory roles of these molecules in vivo. Potential functional roles of ADIOL are of particular interest because of extensive prior work documenting its biosynthesis in microglia (Jellinck et al., 2007) and linkage of genetic variation in the vicinity of the 17β-HSD type 14 locus to risk of Multiple Sclerosis (Bonetti et al., 2009; Wise et al., 1999).

A working model for how ERβ could act as a transcriptional repressor is illustrated in Figure 7E. First, inflammatory stimuli such as LPS induce binding of cJun/cFos AP-1 heterodimers to inflammatory responsive genes. PKA is coordinately activated in a MyD88-dependent manner and induces the phosphorylation of cFos, providing a docking site for ERβ. Binding of Indazole-Br/Cl or ADIOL to ERβ induces interaction of the CtBP-repressor, resulting in transcriptional repression. This proposed transrepression mechanism is functionally analogous to transrepression mechanisms utilized by the glucocorticoid receptor (Rogatsky et al., 2002) and Nurr1 (Saijo et al., 2009) to recruit GRIP and CoREST co-repressor complexes, respectively, to transcriptionally active promoters. Thus, the ERβ pathway functions as a negative feedback mechanism to attenuate transcription from active promoters.

CtBP complexes can also be used to mediate active repression by ERα at a subset of estrogen response elements (Stossi et al., 2009). A key question is therefore to understand the mechanisms and specificity of recruitment of the CtBP complex. The present studies indicate that Indazole-Br/Cl and ADIOL function as selective ERβ modulators that effectively promote interaction with this complex. The inability of 17β-estradiol to induce CtBP interaction therefore provides a molecular explanation for the differential effects of Indazoles and ADIOL vs. 17β-estradiol as inhibitors of inflammatory response genes in microglia. It will be of considerable interest to define the structural differences imposed by these ligands on the ERβ ligand domain and how these differences are ultimately interpreted by components of the CtBP complex. CtBP frequently interacts with target proteins through a PXDLS motif (Schaeper et al., 1998), but ERβ does not have this motif. Therefore, alternative linker proteins are likely to be involved in bridging ERβ and CtBP in ligand-dependent manner, possibly involving posttranslational modifications. Further studies will be required to establish the precise mechanisms of interaction.

Overall, our data suggest that in addition to being a receptor for 17β-estradiol, ERβ is a physiologic receptor for ADIOL that is produced in an autocrine manner by microglia (Jellinck et al., 2007), and potentially astrocytes. Although, the concentration of ADIOL in the brain is not clear at this moment, knockdown of HSD17B14 in microglia cells cultured in 10% serum resulted in an exaggerated inflammatory response. This result suggests that the concentrations of serum-derived DHEA provide substrate for synthesis of sufficient ADIOL to suppress inflammatory responses. The findings that HSD17B14 and HSD3Bs are reciprocally regulated by LPS and that HSD17B14 is positively regulated by the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 suggests that in the setting of acute infection or injury, the ADIOL pathway is rapidly down-regulated to allow an effective inflammatory response to occur. Upon eradication of the inciting stimulus, anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 induce expression of HSD17B14, which by activating the ERβ/CtBP pathway, could promote resolution of inflammation and reestablishment of the de-activated phenotypes of microglia and astrocytes, in concert with other resolution pathways. The finding that 17β-estradiol can antagonize the anti-inflammatory activities of ADIOL provides another level by which the ADIOL pathway might be controlled, and could help explain some of the complexity of estrogen activity in the brain and the increased susceptibility of females to Multiple Sclerosis.

The ability of Indozole-Cl to induce remission of EAE after clinical signs have developed suggests new points of therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative diseases in which inflammation plays a pathogenic role. Prior studies of the ERβ-selective ligand DPN in EAE demonstrated limited benefit that was unrelated to inflammation (Tiwari-Woodruff et al., 2007), consistent with our finding that it does not promote entry of ERβ into the CtBP-dependent transrepression pathway. This, together with our finding that DPN and another ERβ-selective ligand, ERB-041, were inactive in repressing activation of inflammatory response genes in microglia that were inhibited by Indazoles, indicates that ligands that are ERβ-selective but have somewhat different structures can have surprisingly different activities. Although not widely documented, this compound-specific activity of different ERβ-selective ligands appears to be an emerging trend (Minutolo et al., 2009). Therefore, the development of ERβ-specific ligands that are optimized for this activity might be of therapeutic benefit in diseases driven by dysfunction of the innate and adaptive immune systems.

Experimental procedures

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River and ERβ−/− mice were purchased from Jackson laboratory. All animal housing and experiments were approved by IACUC at UCSD.

Cell culture

Primary human microglia and astrocytes were obtained from Clonexpress and Sciencell, respectively. COS-1 cells were purchased from ATCC. Primary mouse microglia and astrocytes were obtained and cultured as described before (Saijo et al., 2009). To treat the cells with various ERβ ligands, cells were cultured in DMEM without Phenol-red (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% Charcoal/Dextran-stripped FBS (Hyclone) for 24 hours in prior to the pre-treatment. Then, cells were incubated with the indicated ligands at the final concentration of 1µM unless otherwise noted for 1 hour followed by 0.1µg/ml LPS (E. coli 0111:B4, Sigma) to microglia or 10ng/ml IL-1β (R & D system) to astrocytes for indicated time. See supplemental experimental procedures for other cells.

Reagents

All smart-pool siRNAs and GIPZ or pLKO.1 shRNA containing lentivirus were purchased from Dharmacon and OpenBiosystems, respectively. Retrovirus carrying shRNA against the PKA a and b catalytic subunits was kindly provided by Mel Simon. Commercially available ERβ ligands were purchased from Steraloids.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assays

2 × 107 BV2 cells were used for ChIP as described before (Saijo et al., 2009). Anti-ERβ (L-20 and H-150), anti-cFos (H-125 and 4) and anti-CtBP1/2 (E-12) were purchased from Santa Cruz biotechnology.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated by RNAeasy kit (QIAGEN) from cells. One microgram of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using Superscript III (Invitrogen), and quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR-GreenER (Invitrogen) detected by 7300 Real Time PCR System (ABI). The sequences of qPCR primers used for mRNA quantification in this study were obtained from PrimerBank (Spandidos et al., 2010).

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)

Osmotic pumps (Alzet) with ligands or vehicle were implanted under the skin 2 days before EAE induction or after the clinical score developed at 1. 8~12 weeks age matched mice were used for the experiment based on the standard protocol (Stromnes and Goverman, 2006). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for detailed protocols.

Gas Chromatography (GC)

For GC determination, steroids were extracted from 1 ml of media and 25 µg of androsterone (Steraloids) added as an internal standard using the method by Gottfried-Blackmore et al. with minor modifications (Gottfried-Blackmore et al., 2008). Samples were loaded onto a Shimadzu GC-2014 gas chromatogram using a 30 m × 0.25 mm (i.d.) ZB-5HT inferno capillary column (film thickness 0.2 µm) (Phenomenex). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for detailed protocols.

Statistical Analyses

Standard deviation (SD), two-tail Student's t-test and ANOVA were performed with the Prism 5 program. p < 0.01 was considered significant. All data are presented as mean ± SD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Benita Katzenellenbogen, Joshua Stender and Christian Schmedt for the critical reading of this manuscript. We are grateful to Norio Yasui for the preparation of Indazole-Cl and Mel Simon for retrovirus carrying shRNA against PKA catalytic subunits, the CMMW vivarium for taking care of animals and Lynn Bautista for help with preparing figures. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (CA52599 to C.K.G., HL087391 to A.C.L., and DK015556 to J.A.K.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

None

References

- Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Napolitani G, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Interleukins 1beta and 6 but not transforming growth factor-beta are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing human T helper cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:942–949. doi: 10.1038/ni1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AE, Brautigam VM, Watters JJ. Estrogen modulates microglial inflammatory mediator production via interactions with estrogen receptor beta. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5021–5032. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar K, Konerth M, Kokiko-Cochran ON, Cardona A, Ransohoff RM, Lamb BT. Regulation of tau pathology by the microglial fractalkine receptor. Neuron. 2010;68:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti A, Koivisto K, Pirttila T, Elovaara I, Reunanen M, Laaksonen M, Ruutiainen J, Peltonen L, Rantamaki T, Tienari PJ. A follow-up study of chromosome 19q13 in multiple sclerosis susceptibility. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;208:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona AE, Pioro EP, Sasse ME, Kostenko V, Cardona SM, Dijkstra IM, Huang D, Kidd G, Dombrowski S, Dutta R, et al. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:917–924. doi: 10.1038/nn1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, Charn TH, Park SH, Helferich WG, Komm B, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS. Estrogen Receptors alpha and beta as determinants of gene expression: influence of ligand, dose, and chromatin binding. Molecular endocrinology. 2008;22:1032–1043. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnadurai G. Transcriptional regulation by C-terminal binding proteins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1593–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis M, Stossi F, Carlson KA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Indazole estrogens: highly selective ligands for the estrogen receptor beta. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1132–1144. doi: 10.1021/jm049223g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, Tato CM, McGeachy MJ, Konkel JE, Ramos HL, Wei L, Davidson TS, Bouladoux N, et al. Generation of pathogenic T(H)17 cells in the absence of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 2010;467:967–971. doi: 10.1038/nature09447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Ogawa S. Combinatorial roles of nuclear receptors in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:44–55. doi: 10.1038/nri1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Saijo K. Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:365–376. doi: 10.1038/nri2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Saijo K, Winner B, Marchetto MC, Gage FH. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010;140:918–934. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold SM, Sasidhar MV, Morales LB, Du S, Sicotte NL, Tiwari-Woodruff SK, Voskuhl RR. Estrogen treatment decreases matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 in autoimmune demyelinating disease through estrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha) Lab Invest. 2009;89:1076–1083. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Estrogen treatment in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;286:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried-Blackmore A, Sierra A, Jellinck PH, McEwen BS, Bulloch K. Brain microglia express steroid-converting enzymes in the mouse. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;109:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober OM, Mutarelli M, Giurato G, Ravo M, Cicatiello L, De Filippo MR, Ferraro L, Nassa G, Papa MF, Paris O, et al. Global analysis of estrogen receptor beta binding to breast cancer cell genome reveals an extensive interplay with estrogen receptor alpha for target gene regulation. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner FL, Greter M, Marino D, Falsig J, Raivich G, Hovelmeyer N, Waisman A, Rulicke T, Prinz M, Priller J, et al. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis repressed by microglial paralysis. Nat Med. 2005;11:146–152. doi: 10.1038/nm1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinck PH, Kaufmann M, Gottfried-Blackmore A, McEwen BS, Jones G, Bulloch K. Selective conversion by microglia of dehydroepiandrosterone to 5-androstenediol-A steroid with inherent estrogenic properties. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;107:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga K, Takaesu G, Yoshida R, Nakaya M, Kobayashi T, Kinjyo I, Yoshimura A. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate suppresses the transcription of proinflammatory cytokines via the phosphorylated c-Fos protein. Immunity. 2009;30:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumbholz M, Theil D, Derfuss T, Rosenwald A, Schrader F, Monoranu CM, Kalled SL, Hess DM, Serafini B, Aloisi F, et al. BAFF is produced by astrocytes and up-regulated in multiple sclerosis lesions and primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2005;201:195–200. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Carlsson B, Grandien K, Enmark E, Haggblad J, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology. 1997;138:863–870. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laflamme N, Nappi RE, Drolet G, Labrie C, Rivest S. Expression and neuropeptidergic characterization of estrogen receptors (ERalpha and ERbeta) throughout the rat brain: anatomical evidence of distinct roles of each subtype. Journal of neurobiology. 1998;36:357–378. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19980905)36:3<357::aid-neu5>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SX, Shi R, Qiu W, Azzi A, Zhu DW, Dabbagh HA, Zhou M. Structural basis of the multispecificity demonstrated by 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase types 1 and 5. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;248:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littman DR, Rudensky AY. Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:845–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacik P, Keller B, Bunkoczi G, Kavanagh KL, Lee WH, Adamski J, Oppermann U. Structural and biochemical characterization of human orphan DHRS10 reveals a novel cytosolic enzyme with steroid dehydrogenase activity. Biochem J. 2007;402:419–427. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay F, Browning JL. BAFF: a fundamental survival factor for B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:465–475. doi: 10.1038/nri844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamas MS, Manas ES, McDevitt RE, Gunawan I, Xu ZB, Collini MD, Miller CP, Dinh T, Henderson RA, Keith JC, Jr, et al. Design and synthesis of aryl diphenolic azoles as potent and selective estrogen receptor-beta ligands. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5021–5040. doi: 10.1021/jm049719y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers MJ, Sun J, Carlson KE, Marriner GA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Estrogen receptor-beta potency-selective ligands: structure-activity relationship studies of diarylpropionitriles and their acetylene and polar analogues. J Med Chem. 2001;44:4230–4251. doi: 10.1021/jm010254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minutolo F, Macchia M, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Estrogen receptor beta ligands: Recent advances and biomedical applications. Med Res Rev. doi: 10.1002/med.20186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller G, Adamski J. Integrated view on 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;301:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F, Helmchen F. Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo. Science. 2005;308:1314–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry VH, Nicoll JA, Holmes C. Microglia in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:193–201. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson K, Gustafsson JA. Role of estrogen receptor beta in estrogen action. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:165–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piechaczyk M, Blanchard JM. c-fos proto-oncogene regulation and function. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1994;17:93–131. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial physiology: unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:119–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogatsky I, Luecke HF, Leitman DC, Yamamoto KR. Alternate surfaces of transcriptional coregulator GRIP1 function in different glucocorticoid receptor activation and repression contexts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16701–16706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262671599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo K, Winner B, Carson CT, Collier JG, Boyer L, Rosenfeld MG, Gage FH, Glass CK. A Nurr1/CoREST pathway in microglia and astrocytes protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation-induced death. Cell. 2009;137:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeper U, Subramanian T, Lim L, Boyd JM, Chinnadurai G. Interaction between a cellular protein that binds to the C-terminal region of adenovirus E1A (CtBP) and a novel cellular protein is disrupted by E1A through a conserved PLDLS motif. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8549–8552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard J, Ricketts ML, Gingras S, Soucy P, Feltus FA, Melner MH. Molecular biology of the 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/delta5-delta4 isomerase gene family. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:525–582. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofroniew MV, Vinters HV. Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:7–35. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0619-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spandidos A, Wang X, Wang H, Seed B. PrimerBank: a resource of human and mouse PCR primer pairs for gene expression detection and quantification. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:D792–D799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer SR, Coletta CJ, Tedesco R, Nishiguchi G, Carlson K, Sun J, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Pyrazole ligands: structure-affinity/activity relationships and estrogen receptor-alpha-selective agonists. J Med Chem. 2000;43:4934–4947. doi: 10.1021/jm000170m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stossi F, Madak-Erdogan Z, Katzenellenbogen BS. Estrogen receptor alpha represses transcription of early target genes via p300 and CtBP1. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1749–1759. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01476-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit WJ. Microglia as neuroprotective, immunocompetent cells of the CNS. Glia. 2002;40:133–139. doi: 10.1002/glia.10154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromnes IM, Goverman JM. Active induction of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1810–1819. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari-Woodruff S, Morales LB, Lee R, Voskuhl RR. Differential neuroprotective and antiinflammatory effects of estrogen receptor (ER)alpha and ERbeta ligand treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14813–14818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703783104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallabhapurapu S, Karin M. Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:693–733. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vegeto E, Benedusi V, Maggi A. Estrogen anti-inflammatory activity in brain: a therapeutic opportunity for menopause and neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vegeto E, Pollio G, Ciana P, Maggi A. Estrogen blocks inducible nitric oxide synthase accumulation in LPS-activated microglia cells. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:1309–1316. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivar OI, Zhao X, Saunier EF, Griffin C, Mayba OS, Tagliaferri M, Cohen I, Speed TP, Leitman DC. Estrogen receptor beta binds to and regulates three distinct classes of target genes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:22059–22066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.114116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall EA, Zavzavadjian JR, Chang MS, Randhawa B, Zhu X, Hsueh RC, Liu J, Driver A, Bao XR, Sternweis PC, et al. Suppression of LPS-induced TNF-alpha production in macrophages by cAMP is mediated by PKA-AKAP95-p105. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra28. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NJ, Boniface K, Chan JR, McKenzie BS, Blumenschein WM, Mattson JD, Basham B, Smith K, Chen T, Morel F, et al. Development, cytokine profile and function of human interleukin 17-producing helper T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:950–957. doi: 10.1038/ni1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise LH, Lanchbury JS, Lewis CM. Meta-analysis of genome searches. Ann Hum Genet. 1999;63:263–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.1999.6330263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav A, Collman RG. CNS inflammation and macrophage/microglial biology associated with HIV-1 infection. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009;4:430–447. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9174-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Gao H, Liu Y, Papoutsi Z, Jaffrey S, Gustafsson JA, Dahlman-Wright K. Genome-wide mapping of estrogen receptor-beta-binding regions reveals extensive cross-talk with transcription factor activator protein-1. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5174–5183. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.