Abstract

Purpose

The authors analyzed the trend from the birth-related statistics of high birth weight infants (HBWIs) over 50 years in Korea from 1960 to 2010.

Methods

We used 2 data sources, namely, the hospital units (1960's to 1990's) and Statistics Korea (1993 to 2010). The analyses include the incidence of HBWIs, birth weight distribution, sex ratio, and the relationship of HBWI to maternal age.

Results

The hospital unit data indicated the incidence of HBWI as 3 to 7% in the 1960's and 1970's and 4 to 7% in the 1980's and 1990's. Data from Statistics Korea indicated the percentages of HBWIs among total live births decreased over the years: 6.7% (1993), 6.3% (1995), 5.1% (2000), 4.5% (2000), and 3.5% (2010). In HBWIs, the birth weight rages and percentage of incidence in infants' were 4.0 to 4.4 kg (90.3%), 4.5 to 4.9 kg (8.8%), 5.0 to 5.4 kg (0.8%), 5.5 to 5.9 kg (0.1%), and >6.0 kg (0.0%) in 2000 but were 92.2%, 7.2%, 0.6%, 0.0%, and 0.0% in 2009. The male to female ratio of HBWIs was 1.89 in 1993 and 1.84 in 2010. In 2010, the mother's age distribution correlated with low (4.9%), normal (91.0%), and high birth weights (3.6%): an increase in mother's age resulted in an increase in the frequency of low birth weight infants (LBWIs) and HBWIs.

Conclusion

The incidence of HBWIs for the past 50 years has been dropping in Korea. The older the mother, the higher was the risk of a HBWI and LBWI. We hope that these findings would be utilized as basic data that will aid those managing HBWIs.

Keywords: Birth weight, Newborn infant, Fetal macrosomia, Incidence, Epidemiology

Introduction

Classification of newborns by birth weight is as follows: low birth weight infant (LBWI, less than 2,500 g), normal birth weight infant (NBWI, 2,500 to 3,999 g), high birth weight infant (HBWI, over 4,000 g)1). Macrosomia means the same as HBWI. The morbidity and mortality is different according to birth weight and the high risk groups include LBWI, HBWI along with premature infant requiring neonatal intensive care1).

Most epidemiologic data of HBWI was dependent on individual hospital units from 1960's to 1990's2-18). There were few studies during the period and the only nationwide survey was conducted by Park et al.19) 1996 based on the data from the governmental statistics department, Statistics Korea. Therefore, we analyzed the epidemiologic data of HBWI from those individual hospital based reports2-18) from 1960's to 1990's. We used the formal nationwide data from Statics Korea from 1993 to 201020,21). The purpose of our study was to establish and support the fundamental descriptive statistics of HBWI in field of neonatal care in Korea.

Materials and methods

First, we surveyed the incidence of HBWI by searching the reports from the individual hospitals from 1960's to 1990's2-18).

Second, because the statistical birth reports from Statistics Korea started in 1993, we could analyze the formal nationwide incidence of HBWI from 1993 to 201020). We used purchased raw data21) of those periods. We analyzed the incidence, distribution characteristics of birth, gender ratio, and the relationship between maternal age.

Results

1. Data from individual hospital units (1960's to 1990's)

1) Incidence of HBWI

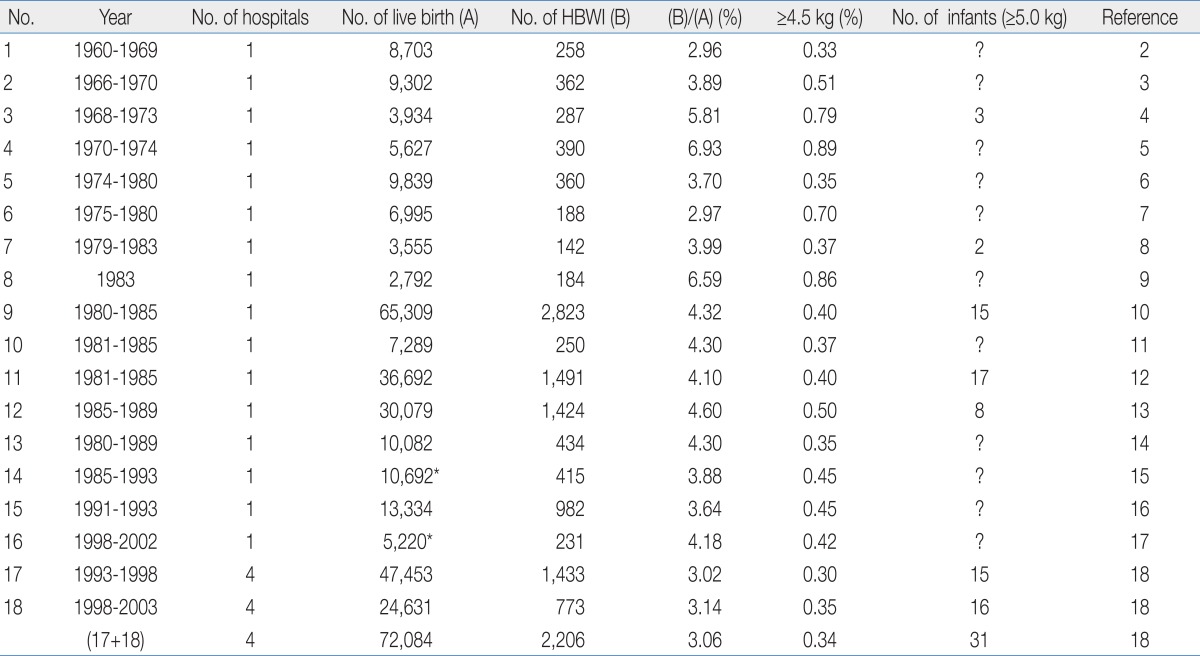

The incidence of HBWI was approximately 3 to 7% in 1960's and 1970's, and 4 to 7% in 1980's and 1990's2-18) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reported High Birth Weight Infants (HBWIs) in Korea (1960 to 2003)

*Live births of term newborn.

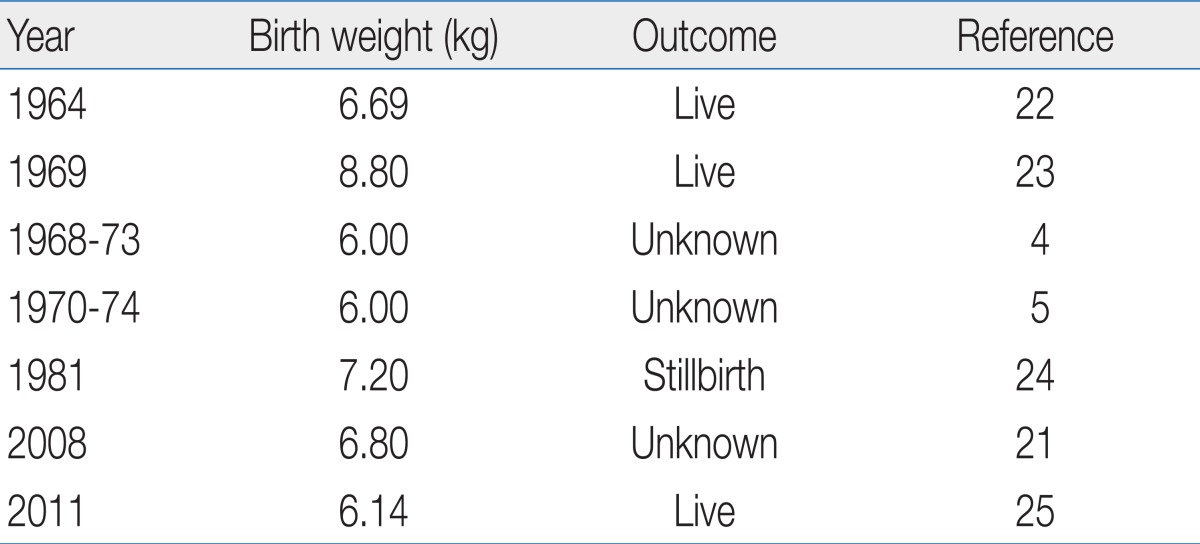

2) Summary of extremely HBWI (>6.0 kg ) report

Table 2 shows characteristics of seven reported cases4,6,21-25) of extremely HBWI (>6.0 kg) from 1964 to 2011 in Korea. Each birth weights were ranged between 6.0 to 8.8 kg.

Table 2.

Reported Extreme Macrosomia (over 6.0 kg of Birth Weight) in Korea

2. Results from Statistics Korea database of HBWI in Korea

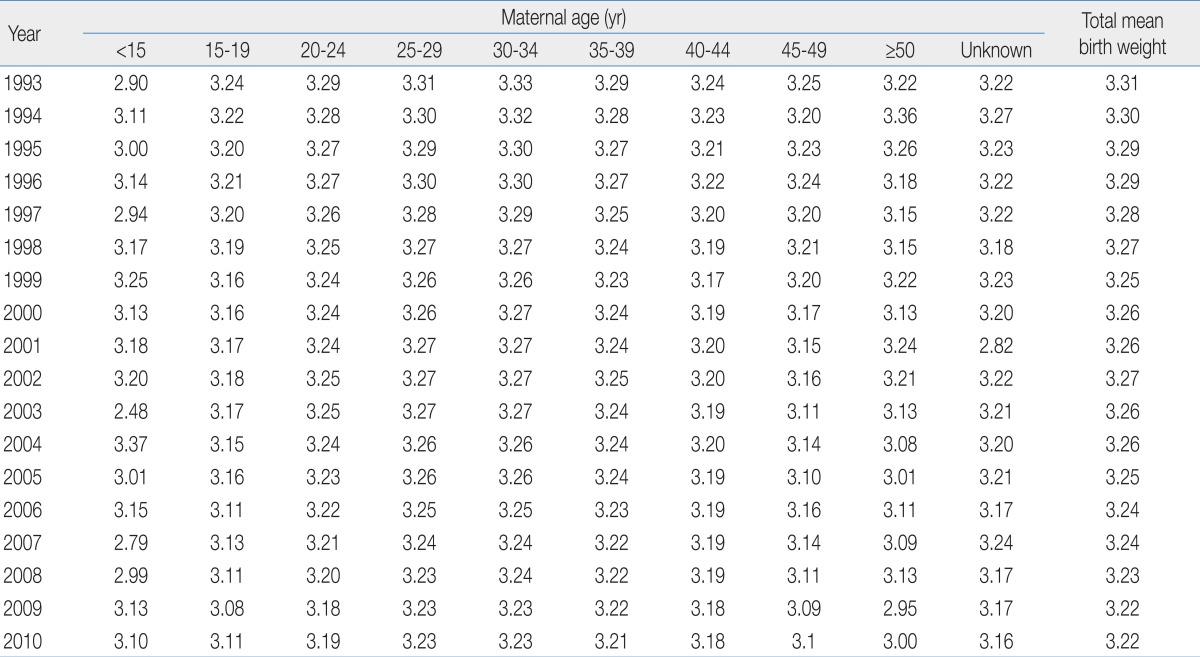

1) Average birth weight in Korea (1993-2010)

The trend in average birth weight and the average weight distribution among mothers grouped in 5-year intervals are shown in Table 3. The average birth weight has decreased from 3.31 kg (1993), 3.29 kg (1995), 3.26 kg (2000), 3.25 kg (2005), and 3.22 kg (2010). Between 1993 and 2010, the birth weight was reduced by approximately 0.1 kg. This is attributed to the recently increased birth frequencies of premature infants, LBWI, and multiple births. Based on the 2010 data, the average birth weights increased from 3.1 kg among mothers younger than 15 years old to 3.23 kg among mother aged 25 to 34 years old. Among mothers over 45 years, the birth weight was 3.0 to 3.1 kg.

Table 3.

Mean Birth Weights (kg) in Korea (1993 to 2010)20)

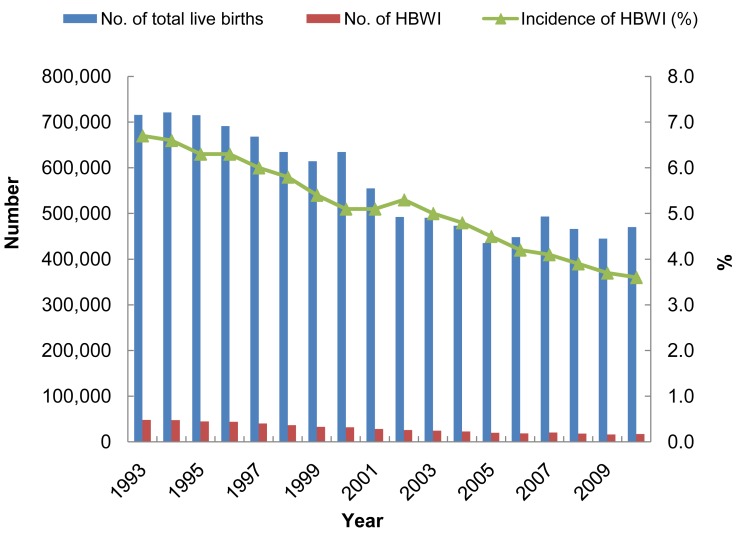

2) Number and frequency of HBWI among total live births (1993 to 2010)

Between 1993 and 2010, the yearly numbers of HBWI and proportions toward total live births are shown in Fig. 1. There has generally been a decreasing trend among HBWI. Between 1993 and 2010, the frequency was reduced by almost half from 6.7 to 3.5%. This suggests that for the past 17 years, the frequency of HBWI has shown a significant decrease.

Fig. 1.

High birth weight infants (HBWIs) among total live births in Korea (1993-2010)20).

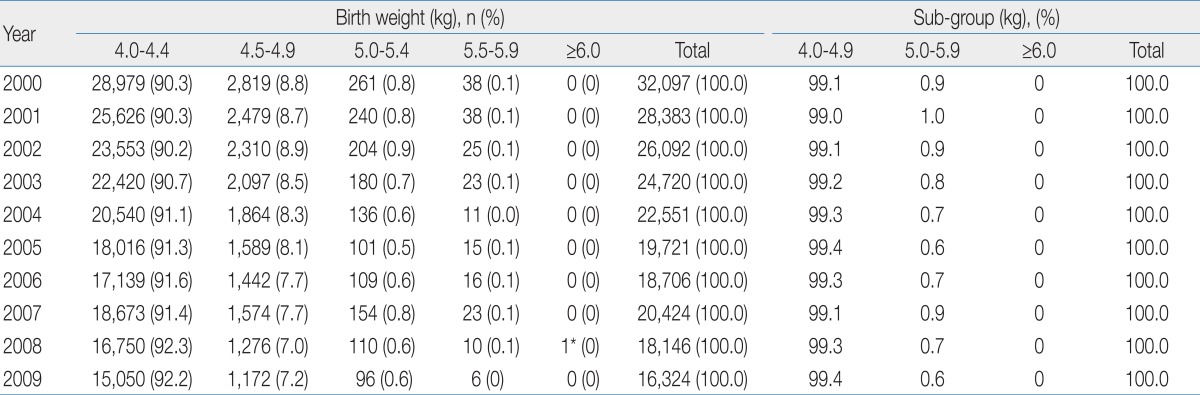

3) Birth weight distribution of HBWI (2000 to 2009)

Table 4 shows the weight distribution when the birth weights of HBWI were divided in 0.5 kg unit intervals. HBWI birth weight in 2009 compared to 2000 is proportionately more distributed to the 4.0 to 4.4 kg range. Most of HBWI (99.4%) was in the 4.0 to 4.9 kg category in 2009. For 10 years, only one infant over 6.0 kg (extreme macrosomia) was born, with birth weight of 6.82 kg. We were unable to follow up with this infant.

Table 4.

Birth Weight Distribution among High Birth Weight Group in Korea (2000-2009)21)

*6.82 kg.

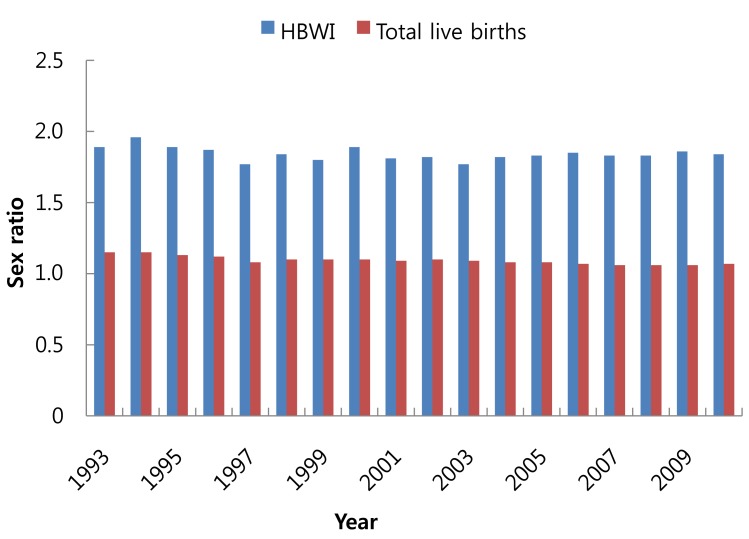

4) Sex ratio of HBWI (1993 to 2010)

Fig. 2 shows the sex ratio between males and females of HBWI. The ratio of male HBWI births to female HBWI is approximately 1.8 from 1993 to 2009. For reference, the sex ratio in total annual births in Korea was averages about 1.1 to 1.2 from 1993 to 2009. Thus, among HBWI, the ratio of males (1.84 in 2010) was higher than females compared with the sex ratio of total births (1.07 in 2010).

Fig. 2.

Sex ratio of high birth weight infants (HBWIs) in Korea (1993-2010)20).

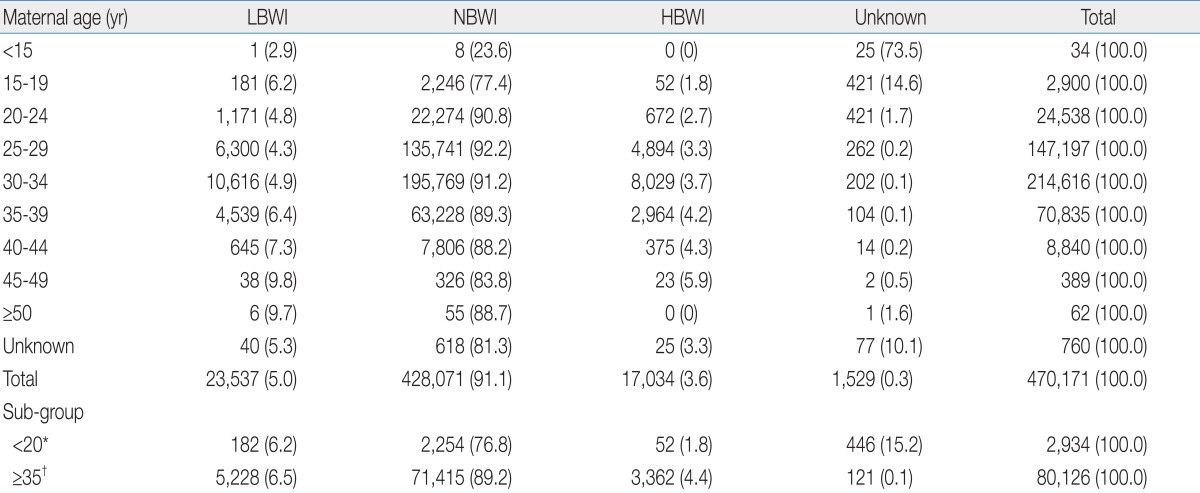

5) Relation between age of mother and HBWI (2010)

In 2010, the age distribution of mothers with LBWI, NBWI, and HBWI is shown in Table 5. The percentages of LBWI, NBWI, and HBWI among the totals were 4.9%, 91.0%, and 3.6%, respectively. Older maternal age increases the risk of both LBWI and HBWI. It was difficult to analyze teen mothers (aged below 20) as their exact ages were unknown in most cases. The frequencies of LBWI and HBWI among aged mothers over 35 years old were higher than the total average.

Table 5.

Distribution of Low, Normal, and High Birth Weight Infants depending on Age of Mothers in Korea (2010)20)

Values are presented as number (%).

LBWI, low birth weight infant (<2.5 kg); NBWI, normal birth weight infant (2.5 to 3.9 kg); HBWI, high birth weight infant (≥4.0 kg).

*Teen aged group. †Advanced maternal aged group.

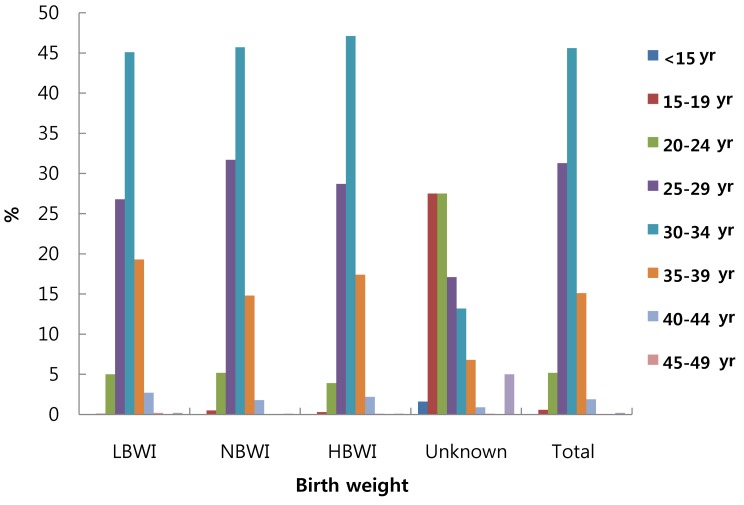

The age distribution of mothers in the LBWI, NBWI, and HBWI categories is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Age distribution of mothers in division of low, normal, and high birth weight infants in Korea (2010)20). LBWI, low birth weight infant; NBWI, normal birth weight infant; HBWI, high birth weight infant.

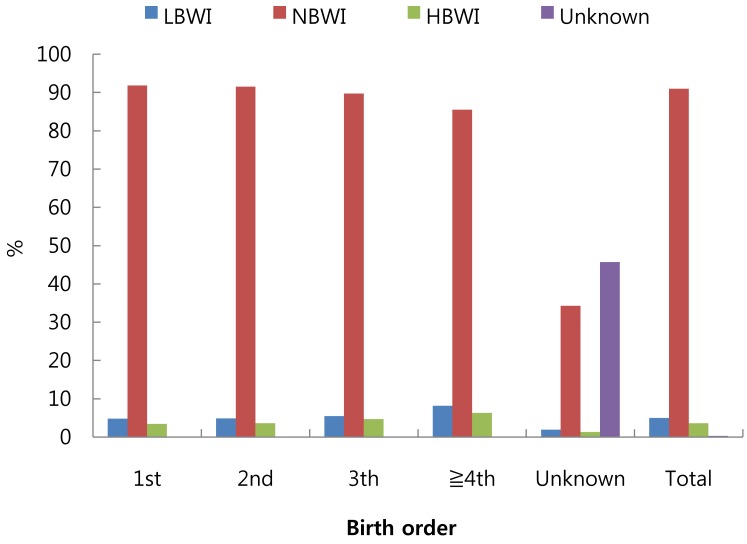

6) Relationship between birth orders of mother and HBWI (2010)

The distribution of LBWI, NBWI, and HBWI depending on the birth order of the infants in 2010 is shown in Fig. 4. The overall frequency of HBWI was 3.6% of the total births and among HBWI, it was 6.3% for mothers who had delivered more than 4 infants. In other words, the higher the fertility, the higher was HBWI frequency. The risk of HBWI with increased birth order could be a result of increased maternal age (confounding) but we are unable to separate those effects with these data.

Fig. 4.

Relationship between birth orders of mother and low, normal, and high birth weight Infants in Korea (2010)20). LBWI, low birth weight infant; NBWI, normal birth weight infant; HBWI, high birth weight infant.

Discussion

Macrosomia of newborn frequently occur in gestational diabetes mellitus, obesity and in families with previous history. Approximately 6 to 10% of pregnant women are obese and 19% of obesity is accompanied with diabetes26). Cho et al.26) reported that increased body mass index raises risk of diabetes, and obesity in pregnant women is closely related to macrosomia birth. Three to 10% of all pregnant women with diabetes have abnormal blood sugar and 80% have gestational diabetes26). Various complications can occur in the fetus of pregnant women with diabetes. However, the typical pathogenesis is that elevated glucose and nutrients of pregnant women can cause hyper-insulinemia in the fetus with resulting complications. Its effects over a fetus or live born includes macrosomia27). Cho et al.26) discussed numerous risk factors for gestational diabetes, many of which center round a prior history of such problems, and notes that delivery of macrosomia infant was significantly high. The frequency of macrosomia was 13.3% in the case of gestational diabetes, contrasted to 3.6% in the mothers without gestational diabetes26).

From 1993 through 2010, the average birth weight of Korea was reduced from 3.31 kg in 1993 to 3.22 kg in 2010 by approximately 0.1kg. This is attributed to the increase of LBWI and multiple fetus28-30), increase of LBWI including improved survival of LBWIs, and multiple births28-30), increase of LBWI including improved survival of LBWIs, and multiple births resulting from both improved survival of non-singletons and use of assisted reproductive techniques.

From 1960 to 1990, a summary of HBWI and frequencies of over 4.5 kg in birth weight as reported in single- and multi-site hospitals2-18) in Korea are shown in Table 1. The frequency of HBWI at a single hospital was 2.96 to 6.93% and the frequency of birth weight over 4.5 kg was 0.30 to 0.86%. When observing the heaviest weight among HBWI during 1964 to 2011 (Table 2), infants of 8.8 kg, 7,2 kg (stillbirth), 6,8 kg, 6,14 kg, 6,0 kg, 6,0 kg were represented by examples as the maximum birth weight21-25).

Park et al.19) analyzed the delivery data of HBWI for a single fetus numbering 673,766 infants for one year in 1996 by using birth data of Statistics Korea.

The frequency of HBWI based on birth registration data from Statistics Korea20) was reduced from 6.7% in 1993 to 3.6% in 2010. This figure is the similar to figures reported during the period from 1960 to early 2000 of the aforementioned single hospital studies. As the frequency is reduced every year from 1993 through 2010 based on Statistics Korea, and between 1993 and 2010, it is reduced by half. This reduction is due to improved management before delivery for the mother, particularly for those with gestational diabetes, the most important cause among HBWI causes.

Although national birth statistics data was utilized for this study, the data for diseases, including maternal diabetes, were not complete; thus, we unable to analyze them. Additional research in this area is needed.

As above, the frequency and trend of HBWI during the past 50 years in Korea has been observed and the relationship between a maternal age and fertility in HBWI was analyzed. HBWI is also a high-risk infant group. We hope that these basic epidemiology findings would be useful in the infant management of HBWI.

References

- 1.Stoll BJ, Adams-Chapman I. The high risk infant. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton B, editors. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Saunder Elsevier; 2007. pp. 698–711. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JH, Chang BS, Hur S, Cha HK. Clinical survey of giant babies. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;14:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung YC, Lee MH, Lee KH, Pae JM, Cho TH. Obstetric risk of large fetus. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;15:445–451. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhee NH, Lee CN, Kang JD, Ahn KS. Clinical survey of large fetuses. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;19:109–118. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park EH, Sul YH, Wee HK, Ko HJ, Im HJ. A clinical survey of large babies. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;19:405–410. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim KJ, Lim WS, Suh HS, Kim BC, Cho TH. A clinical study of the macrosomia. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;26:143–148. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoo MS, Park CS, Cha IS, Bae HK. Clinical survey and obstetric significance of giant baby. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;25:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JM, Kim KT, Kim HI, Kim HC. Obstetric implications of fetal macrosomia. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;27:1257–1266. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn JJ. A clinical study on large infants. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;27:1660–1667. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DS, Park HJ, Cho S, Nha DJ, Bae SN, Kim CI. Clinical study of macrosomia. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;28:1613–1619. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ha HR, Kang JM, Lee YJ, Cha DS, Kim DH. A clinical study on large babies. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;31:100–106. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong KW, Kim HJ, Oh JY, Chun CH, Martin BH. Clinical survey of fetal macrosomia. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;31:925–933. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang IG, Kim JW, Lee WM, Kim JK, Lee BT, Kang SD, et al. Clinical survey of fetal macrosomia. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;34:941–947. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon HK, Eom SH, Chung SY, Hwang SH, Kim SD, Ahn JY. Clinical survey on macrosomia. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;36:150–156. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JS, Ko HJ, Kim YS, Cho Y, Roe ES, Kim YP. Clinical survey on fetal macrosomia. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;37:650–656. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JI, Jeong CJ, Lee MR, Lee TS, Yoon SD, Lee DY. Clinical survey on fetal macrosomia. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;37:1186–1193. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim DG, Yang HS. Clinical survey on fetal macrosomia. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;47:1668–1672. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han CH, Cheon SH, Lee Y, Kwon I, Shin JC, Kim SJ. A Clinical study on macrosomia. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SH, Han JH, Lim KS, Ku SY, Kim SH. Study on macrosomia based on birth certificate data. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;43:1611–1615. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Statistics Korea, Korean Statistical Information Service [Internet] Daejeon: Statistics Korea; c2010. [cited 2012 Mar 30]. Birth statistics. Available from: http://kosis.kr/abroad/abroad_01List.jsp?parentId=A. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Statistics Korea. Birth data (raw data from Statistics Korea), 2000-2009. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pak HS, Ko DY. A case report of giant baby. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;8:177–180. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park HS, Park SH, Ahn KH, Han CW. A case of a giant baby whose weight at birth was 8.8 kg. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;12:541–543. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YT, Ko EK, Lee KH, Yoo H. One case of giant baby. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;27:411–414. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeong KA, Kim SY, Chang JY, Bae CW. An extremely macrosomia born weighted to 6.14 kg: case report and review of the literatures. J Korean Soc Neonatol. 2012;19:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho AR, Kyeung KS, Park MA, Lee YM, Jeong EH. Risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus. Korean J Perinatol. 2007;18:329–337. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hwang JS. Neonate born to diabetic mother. Korean J Perinatol. 2006;17:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang BH, Jung KA, Hahn WH, Shim KS, Chang JY, Bae CW. Regional analysis on the incidence of preterm and low birth weight infant and the current situation on the neonatal intensive care units in Korea, 2009. J Korean Soc Neonatol. 2011;18:70–75. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi SH, Park YS, Shim KS, Choi YS, Chang JY, Hahn WH, et al. Recent trends in the incidence of multiple births and its consequences on perinatal problems in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:1191–1196. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.8.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park YS, Choi SH, Shim KS, Chang JY, Hahn WH, Choi YS, et al. Multiple births conceived by assisted reproductive technology in Korea. Korean J Pediatr. 2010;53:880–885. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2010.53.10.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]