Abstract

Urocortin 3 (also known as stresscopin) is an endogenous ligand for the corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2 (CRF2). Despite predominant Gs-coupling of CRF2, promiscuous coupling with other G proteins has been also associated with the activation of this receptor. As urocortin 3 has been involved in central cardiovascular regulation at hypothalamic and medullary sites, we examined its cellular effects on cardiac vagal neurons of nucleus ambiguus, a key area for the autonomic control of heart rate. Urocortin 3 (1 nM to 1000 nM) induced a concentration-dependent increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration that was blocked by the CRF2 antagonist K41498. In the case of two consecutive treatments with urocortin 3, the second urocortin 3-induced Ca2+ response was reduced, indicating receptor desensitization. The effect of urocortin 3 was abolished by pretreatment with pertussis toxin and by inhibition of phospolipase C with U-73122. Urocortin 3 activated a Ca2+ influx via voltage-gated P/Q-type channels as well as Ca2+ release from endoplasmic reticulum. Urocortin 3 promoted Ca2+ release via inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate receptors but not ryanodine receptors. Our results indicate a novel Ca2+- mobilizing effect of urocortin 3 in vagal preganglionic neurons of nucleus ambiguus, providing a cellular mechanism for a previously reported role for this peptide in parasympathetic cardiac regulation.

Keywords: calcium imaging; CRF2; endoplasmic reticulum; inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate receptors

Introduction

The mammalian corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) family includes CRF, urocortins 1, 2 and 3, their receptors: CRF1 and CRF2, and a CRF binding protein (Bale and Vale, 2004). CRF acts within both the central and peripheral nervous system to coordinate the overall response of the body to stress. Urocortins contribute to the fine-tuning of the complex process of stress adaptation by exerting complementary or sometimes contrasting actions (Hillhouse and Grammatopoulos, 2006). Urocortin 3 (stresscopin), the newest member of CRF family, has high affinity for CRF2 (Hsu and Hsueh, 2001; Lewis et al., 2001). While CRF1 expression is high in cortical, cerebellar and sensory structures, CRF2 expression was found confined to subcortical structures (Chalmers et al., 1995), and medullary nuclei (Van Pett et al., 2000), indicating distinctive functional roles for each receptor. In addition, distinct pharmacological profiles were identified for CRF1 and CRF2 (Prius et al., 1997). Multiple splice variants were identified for CRF2: CRF2 alpha and gamma are expressed in the brain while CRF2 beta, identified in the brain and peripheral tissues such as heart and skeletal muscle (Lovenberg et al., 1995; Kostich et al., 1998).

CRF receptors have a critical role in the stress adaptation response (Valentino et al., 2010). Emerging evidence supports a complex interaction between CRF1 and CFR2 that contributes to the fine tuning of the cellular responses. Their contribution to stress response is brain area specific (Waselus et al., 2009). For example, in the dorsal raphe, activating CRF1 vs CRF2 has opposing physiological and behavioral consequences (Waselus et al., 2011). Relatively low levels of CRF released during mild stress or the initial stages of a more severe stress activate primarily CRF1 receptors at this level, initiating an active behavioral response. In contrast, more severe stress or stress of a longer duration release higher levels of CRF followed by the activation of CRF2 in dorsal raphe, and promotes passive behavior (Waselus et al., 2011). Moreover, CRF2 activation may dynamically regulate the tone of the serotonin system depending on the level of endogenous or exogenous ligand (Pernar et al., 2004). A differential cellular distribution and receptor trafficking of CRF1 and CRF2 in dorsal raphe (Valentino et al., 2010) or locus coeruleus (Reyes et al., 2008) have been involved in stress-related behavioral plasticity.

Urocortins modulates cardiovascular function by acting at multiple levels via several mechanisms (Yang et al., 2010; Emeto et al., 2011). Microinjection of urocortin 3 in nucleus of the solitary tract produced neuronal excitation followed by depressor and bradycardic responses; the bradycardia was vagally-mediated (Nakamura et al., 2009). Conversely, intracerebroventricular administration or microinjection of urocortin 3 into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus elicited pressor and tachycardic responses via sympatho-adrenal-medullary system (Chu et al., 2004, Li et al., 2010). Microinjection of urocortin 1 in the nucleus ambiguus elicited vagally-mediated bradycardia via CRF1 activation (Chitravanshi and Sapru, 2011).

The bradycardic effect induced by microinjection of urocortin 3 in the nucleus ambiguus (Chitravanshi and Sapru, 2007) prompted us to explore the cellular effects of urocortin 3 in preganglionic vagal neurons of nucleus ambiguus.

Experimental procedures

Chemicals

2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB, K41498, ω-conotoxin MVIIC, ω-conotoxin GVIA, pertussis toxin, cholera toxin, and U-73122 were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), xestospongin C and ryanodine were from EMD Chemicals Inc (San Diego, CA), and urocortin 3 was from American Peptide Company Inc (Sunnyvale, CA).

Animals

Neonatal Sprague Dawley rats (1–2-day-old) (Ace Animals Inc., Boyertown, PA), of either sex, were used for retrograde tracing, and neuronal culture. Experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Neuronal labeling and culture

Cardiac vagal preganglionic neurons of nucleus ambiguus were retrogradely labeled by intrapericardial injection of rhodamine (X-TRITC, 40 μl, 0.01 %, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), similar to previous reports (Mendelowitz and Kunze, 1991; Mendelowitz, 1996; Bouairi et al., 2006). Medullary neurons were dissociated and cultured, 24 hours after rhodamine injection, as previously described (Brailoiu et al., 2009). The neuronal labeling was verified by fluorescence microscopy in medullary slices cut with a vibratome (300 μm), fixed in paraformaldehyde, treated with DMSO and mounted in Citifluor. For the neuronal culture, the brains were quickly removed and immersed in ice-cold Hanks balanced salt solution (Mediatech, Manassas, VA). The ventral side of the medulla (containing nucleus ambiguus) was dissected, minced and the cells were dissociated by enzymatic digestion with papain, followed by mechanical trituration. After centrifugation at 500g, fractions enriched in neurons were collected and resuspended in culture medium containing Neurobasal-A (Invitrogen), which promotes the survival of postnatal neurons, 1% GlutaMax (Invitrogen), 2% penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin B solution (Mediatech) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA). Cells were plated on round 25 mm glass coverslips previously coated with poly-D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich) in 6-well plates. Three neonates provided enough medullary cells for 6 × 25 mm coverslips. Cultures were maintained at 37° C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The mitotic inhibitor cytosine β-arabino furanoside (1μM) (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the culture to inhibit glial cell proliferation (Schoniger et al., 2001). Unpublished observations from our laboratory, using labeling for neuronal specific enolase (NSE) and glial filament associated protein (GFAP) indicate that in our culture conditions, 70% – 80% of the cells are neurons. Cells were used for calcium imaging after 2–4 days in culture. Ca2+ measurements were carried out in 6–10 rhodamine-labeled neurons for each compound/concentration.

Calcium imaging

Measurements of [Ca2+]i were performed from rhodamine-labeled neurons as previously described (Brailoiu et al., 2009, 2012). Cells were incubated with 5 μM fura-2 AM (Invitrogen) in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) at room temperature for 45 min, in the dark, washed three times with dye-free HBSS, and then incubated for another 45 min to allow for complete de-esterification of the dye. Coverslips (25 mm diameter) were subsequently mounted in an open bath chamber (RP-40LP, Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) on the stage of an inverted microscope Nikon Eclipse TiE (Optical Apparatus Co., Ardmore, PA). The microscope is equipped with a Perfect Focus System and a Photometrics CoolSnap HQ2 CCD camera (Roper Scientific, Optical Apparatus Co.). During the experiments the Perfect Focus System was activated. Rhodamine (emission 580 nm)-labeled neurons were identified after excitation at 510 nm. Fura-2 AM fluorescence (emission= 510 nm), following alternate excitation at 340 and 380 nm, was acquired at a frequency of 0.25 Hz. Images were acquired and analyzed using NIS-Elements AR 3.1 software (Nikon/Optical Apparatus Co.). The ratio of the fluorescence signals (340/380 nm) was converted to Ca2+ concentrations (Grynkiewicz et al., 1985). Neurons were transferred to a medium without fetal serum 12 hr prior to Ca2+ measurements.

Statistical analysis

Data was expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). One way ANOVA followed by post-hoc analysis using Bonferonni and Tukey tests was used to evaluate significant differences between groups; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Urocortin 3 increases [Ca2+]i in preganglionic neurons of nucleus ambiguus

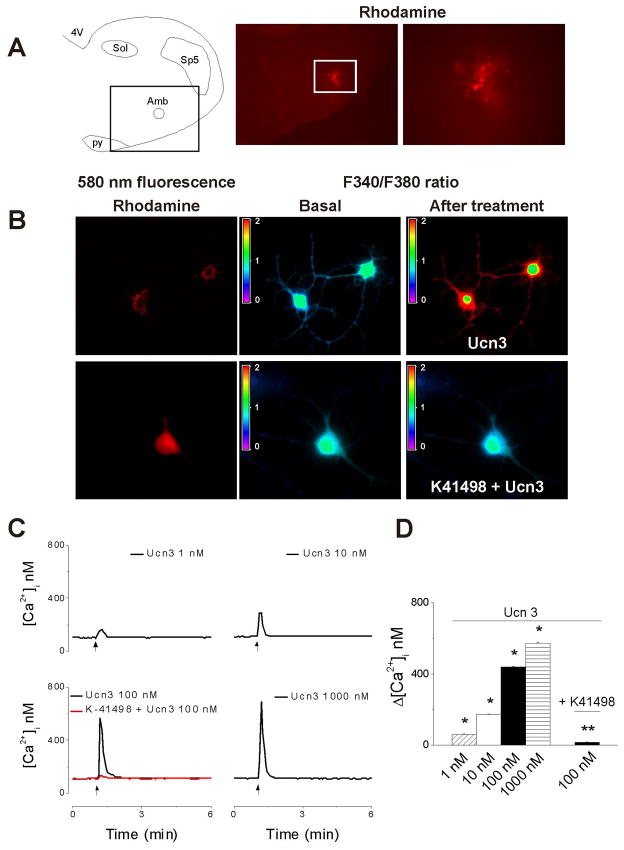

Rhodamine has been shown to be a reliable marker for retrograde labeling of cardiac vagal neurons (Mendelowitz and Kunze, 1991; Bouairi et al., 2006). Parasympathetic cardioinhibitory neurons in the nucleus ambiguus were identified by the presence of the rhodamine as a cluster situated in the rostroventrolateral quadrant of the medullary slices (Fig. 1A). Rhodamine-labeled cells whose longest neurite was at least three times longer than the cell body and which responded to KCl (20 mM) by a robust increase in Ca2+ were considered neurons (Brailoiu et al., 2005, 2012) and were selected for Ca2+ measurements (Fig. 1B, left panels). Higher K+ concentration (KCl 50 mM) has been shown to elicit an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ in astrocytes (Oikawa et al., 2005). Urocortin 3 (100 nM) produced an increase in F340/F380 ratio of fura-2AM-loaded neurons, which was prevented by treatment with K41498, a CRF2 antagonist (Fig. 1B). Treatment with urocortin 3 (1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM and 1000 nM) produced a fast and transitory increase in [Ca2+]i by 61 ± 1.8 nM, 173 ± 2.2, 438 ± 3.9 and 572 ± 4.1 nM, respectively; n = 6–10 neurons for each concentration tested. Representative examples of urocortin 3-induced increases in [Ca2+]i are shown in Fig. 1C and the concentration-dependent relationship in Fig. 1D. In the presence of K41498 (10 μM), urocortin 3 (100 nM) produced an increase in [Ca2+]i by only 16 ± 1.3 nM (versus 438 ± 3.9 in the absence of the antagonist), (n= 10) indicating that the response was CRF2-mediated.

Figure 1. Urocortin 3 increases cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in vagal preganglionic neurons via CRF2 activation.

A, The left panel indicates the localization of nucleus ambiguus (Amb) in a medullary slice; the boxed area indicates the level shown in the middle panel. Abbreviations: 4V, 4th ventricle; py, pyramidal tract; Sol, nucleus of the solitary tract, and Sp5, spinal trigeminal nucleus. Lower magnification (middle panel) and higher magnification (right panel) of a medullary slice illustrating retrogradely labeled rhodamine-containing cardiac vagal neurons of nucleus ambiguus. B, Fura-2 AM fluorescence ratio (F340/F380 nm) of rhodamine-labeled neurons, before and after treatment with urocortin 3 (Ucn3, 100 nM) in the absence (top panels) and presence of CRF2 antagonist K41498 (10 μM). C, Representative examples of increases in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, [Ca2+]i, in response to different concentrations of urocortin 3 (1–1000 nM) and urocortin 3 (100 nM) after pretreatment with K41498 (10 μM.); the arrows indicate the application of Ucn3. D, Comparison of mean amplitude ± SEM of [Ca2+]i increase produced by urocortin 3 (1–1000 nM) and urocortin 3 (100 nM) after pretreatment with K41498 (10 μM); urocortin 3 induced a concentration-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i; the effect was abolished by K41498. P < 0.05 compared to basal [Ca2+]i (*) or to urocortin 3 (100 nM)-induced increase in [Ca2+]i (**).

Urocortin 3-induced increase in [Ca2+]i is subject to tachyphylaxis

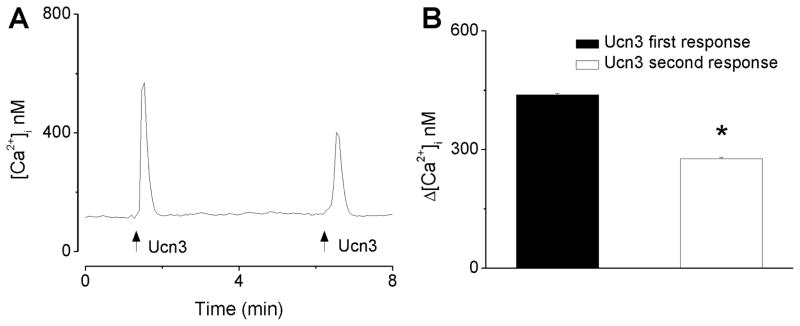

In this series of experiments we examined the Ca2+ responses of nucleus ambiguus neurons to two consecutive applications of urocortin 3; a representative example is illustrated in Fig. 2A. The first application of urocortin 3 (100 nM) produced a fast and transient increase in [Ca2+]i; the second application of urocortin 3 (100 nM), five minutes after the first treatment, produced a fast and transitory increase in [Ca2+]i with lower amplitude than the first response (Fig. 2A). The first administration of urocortin 3 (100 nM) produced an increase in [Ca2+]i by 438 ± 3.9 nM, while the second administration increased [Ca2+]i by 277 ± 3.1 nM (n = 6) (Fig. 2B). The second response was significantly smaller than the first response (P < 0.05) indicating desensitization of the receptors.

Figure 2. Urocortin 3-induced increase in [Ca2+]i is subject to tachyphylaxis.

A, Representative example of [Ca2+]i increases produced by two consecutive applications of urocortin 3 (100 nM), 5 min apart, in vagal preganglionic neurons of nucleus ambiguus; the arrows indicate the application of urocortin 3 (Ucn3). B, Comparison of the mean amplitude ± SEM of [Ca2+]i increase produced by the first and second application of urocortin 3 (100 nM); * P < 0.05 compared to the first response.

CRF2 receptors are coupled with Gi/o proteins and PLC activation in nucleus ambiguus neurons

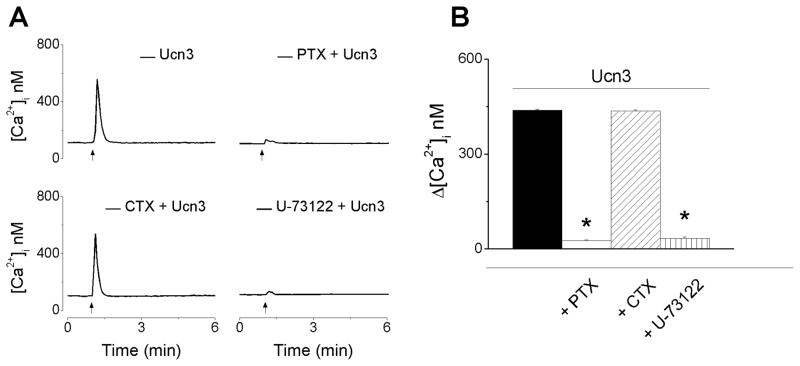

As CRF2 receptors have been reported to be coupled with multiple G proteins, we next examined the type of G protein coupling in cardiac vagal neurons. Treatment with pertussin toxin (100 nM), that inhibits Gi/o proteins, prevented the urocortin 3-induced increase in Ca2+ (27 ± 1.1 nM in cells pretreated with pertussis toxin, as compared to 438 ± 3.9 in the absence of pretreatment, n = 6) (Fig. 3). On the other hand, inhibition of Gs proteins with cholera toxin (100 nM) did not affect the response (436 ± 3.9 nM). Inhibition of phospholipase C by U-73122 (1 μM), markedly decreased the urocotin 3-induced increase in [Ca2+]i (34 ± 3.7 nM, n = 6). Examples of representative Ca2+ recordings from neurons treated with urocortin 3 (100 nM) in absence and presence of the pertussis toxin (PTX) cholera toxin (CTX) and U-73122 are shown in Fig. 3A, and the comparison of the average increases in Ca2+ in Fig. 3B.

Figure 3. Urocortin 3-induced increase in [Ca2+]i is inhibited by pertussis toxin and U-73122.

A, Representative examples of urocortin 3 (100 nM)-induced increase in [Ca2+]i in the absence (top left trace) and presence of pertussis toxin (PTX) (100 nM, top right), a Gi/o inhibitor; cholera toxin (CTX) (100 nM, bottom left), a Gs inhibitor, and U-73122 (1 μM, bottom right), a PLC inhibitor. B, Comparison of mean amplitude ± SEM of [Ca2+]i increase produced by urocortin 3 (100 nM) in the absence or presence of PTX, CTX and U-73122 (* P < 0.05 compared to the response to urocortin 3 alone). Pertussis toxin and U-73122 abolished urocortin 3-induced increase in [Ca2+]i

Urocortin 3 promotes Ca2+ influx via voltage-gated P and Q channels

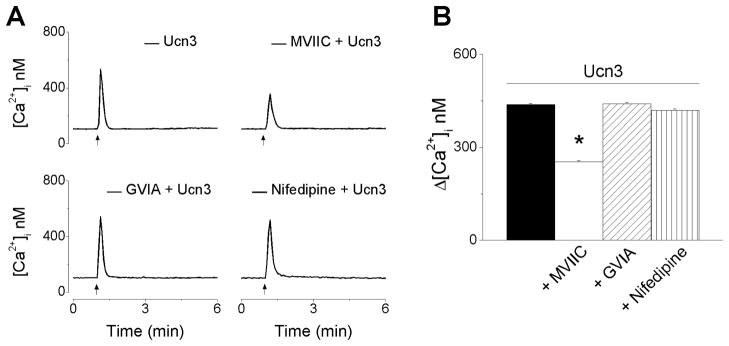

We evaluated the contribution of Ca2+ influx via voltage-gated P/Q-, N- and L-type Ca2+ channels in urocortin 3-induced increase in [Ca2+]i. Representative Ca2+ recordings from neurons treated with urocortin 3 (100 nM) in absence and presence of Ca2+ channel blockers are shown in Fig. 4A, indicating a reduction in the amplitude of Ca2+ response in the presence of ω-conotoxin MVIIC. Blockade of voltage-gated P/Q Ca2+ channels with ω-conotoxin MVIIC (100 nM), reduced the amplitude of urocortin 3-induced [Ca2+]i to 253 ± 3.4 nM (as compared to 438 ± 3.9 nM in the absence of the blocker) (Fig. 4B). Pretreatment with ω-conotoxin GVIA (100 nM), a blocker of N-type channels or with nifedipine (1 μM), a blocker of L-type channels did not significantly affect urocortin 3-induced increase in [Ca2+]i (441 ± 3.8 nM after ω-conotoxin GVIA, and 419 ± 4.6 nM after nifedipine).

Figure 4. Urocortin 3 promotes Ca2+ influx via voltage-gated P and Q channels.

A, Representative examples of urocortin 3 (100 nM)-induced increase in [Ca2+]i in the absence (top left trace) and presence of ω-conotoxin MVIIC (MVIIC, 100 nM, top right), a P/Q-type inhibitor; ω-conotoxin GVIA (GIVA, 100 nM bottom left), a N-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor, or nifedipine (1 μM, bottom right), a L-type Ca2+ channel. B, Comparison of mean amplitude ± SEM of [Ca2+]i increase produced by urocortin 3 (100 nM) in the absence or presence of MVIIC, GVIA or nifedipine (* P < 0.05 compared to the response to urocortin 3 alone).

Urocortin 3 promotes Ca2+ release via IP3 receptors

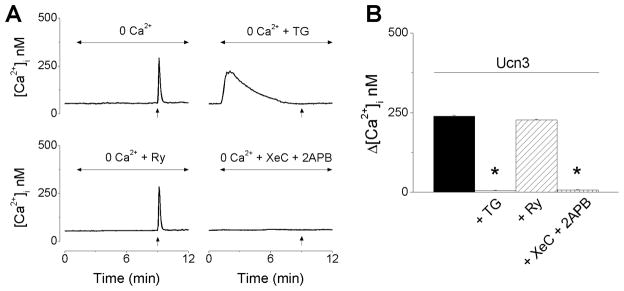

In Ca2+-free saline, urocortin 3 produced a fast and transitory increase in [Ca2+]i with a lower amplitude than that occurring in Ca2+-containing saline. The response elicited by urocortin 3 in Ca2+-free saline was abolished by thapsigargin, a sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATP-ase inhibitor or by blockade of IP3 receptors with xestospongin C (XeC) and 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) (Fig. 5A). Urocortin 3 (100 nM) -induced increase in [Ca2+]i in Ca2+-free saline, was 239 ± 2.5 nM (Fig. 5B, black column), which was significantly lower (P < 0.05) than the response in regular Ca2+-containing saline (438 ± 3.9 nM) (Fig. 1). Pretreatment with thapsigargin or xestospongin C and 2-APB abolished the response; from Δ[Ca2+]i =239 ± 2.5 nM to 5 ± 1.4 nM and 7 ± 1.8 nM, respectively (Fig. 5B). Blockade of ryanodine receptors with ryanodine (10 μM) did not significantly affect the response (Δ[Ca2+]i = 227 ± 2.7 nM) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Urocortin 3 promotes Ca2+ release via IP3-dependent mechanisms.

A, Representative examples of increases in [Ca2+]i produced by urocortin 3 (100 nM) in Ca2+-free saline alone before (top left) or after treatment with thapsigargin (TG, 1 μM, top right), ryanodine (Ry, 10 μM, bottom left) or xestospongin C (XeC, 1 μM) and 2- aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2APB, 100 μM, bottom right); the arrows indicate the treatment with Ucn3. B, Comparisons of mean amplitude ± SEM of [Ca2+]i increase produced by urocortin 3 (100 nM) in Ca2+-free saline alone or in presence of TG, Ry or XeC + 2APB (* P < 0.05 compared to the response to urocortin 3 alone).

Discussion

Urocortin 3 (stresscopin) has been involved in the central cardiovascular regulation by activating CRF2 in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (Li et al., 2010) or nucleus of the solitary tract (Nakamura et al., 2009). The parasympathetic activity to the heart is dominated by cardiac vagal neurons originating in the nucleus ambiguus (Mendelowitz, 1999). Microinjection of urocortin 3 in nucleus ambiguus elicited bradycardia (Chitravanshi and Sapru, 2007); this prompted us to examine the underlying mechanisms of urocortin 3 effects on cardiac vagal neurons of nucleus ambiguus.

Urocortin 3 induced a concentration-dependent increase in cytosolic Ca2+ that was sensitive to K41498, a highly selective CRF2 antagonist (Lawrence et al., 2002), indicating that the effect was CRF2-mediated. Although a partial overlap between urocortin 3 immunoreactive fibers and CRF2 receptors has been identified in several brain regions, including medullary nuclei such as nucleus of the solitary tract, the presence of urocortin 3 fibers or CRF2 in the rat nucleus ambiguus has not been clearly established (Primus et al., 1997; Van Pett et al., 2000, Li et al., 2002). This may imply that the levels of CRF2 are very low or can only be detected under certain conditions; this has been proposed also for other brain regions where urocortins are active despite the lack of identification of the receptors (Li et al., 2002; Hauger et al., 2003). Mammalians express three known CRF2 variants: CRF2α and CRF2β are found in both human and rodents and CRF2γ has so far been found only in human CNS (Hillhouse and Grammatopoulos, D, 2006). Moreover, there have been reports that the gene encoding the CRF2 is frequently misspliced, and the existence of additional CRF2 isoforms in the rat has been suggested (Kostich et al., 1998).

A second application of urocortin 3 produced a significantly reduced response than the first application, suggesting the desensitization of the receptor, a phenomenon common to G protein-coupled receptors (Gainetdinov et al., 2004) and also reported for CRF receptors (Schilling et al., 1998).

Multiple signaling mechanisms were associated with CRF2 activation (Blank et al., 2003; Hillhouse and Grammatopoulos, 2006). Several lines of evidence indicate that CRF2 is Gs-coupled (Kishimoto et al., 2005; Dautzenberg et al., 1997; Lewis et al., 2001). However, emerging evidence indicate the CRFs receptors are highly promiscuous and can activate different Gα-subunits, with an order of potency Gαs> Gαo>Gαq/11>GGαi1/2>Gαz (Hillhouse and Grammatopoulos, 2006). The promiscuous coupling may be explained by distinct active conformations of the CRFs and different profiles of G protein activation determined by the agonists interaction with specific binding domains within the receptor binding pocket.

Despite the fact that an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ by GPCR agonists is generally associated with activation of Gq/11 proteins, Gi/o and Gs proteins can also lead to Ca2+ mobilization. βγ subunit of Gi/o protein family may bind to and activate phospholipase C (PLC)-β (Katz et al., 1992; Koch et al., 1994), while Gs protein may activate PLC-ε, via Epac (Kang et al., 2003), a cAMP sensor, followed by Ca2+ mobilization. We examined the possible involvement of Gi/o coupling by determining the sensitivity of Ca2+ response to urocortin to treatment with pertussis toxin, which inhibits Gi/o signaling via ADP ribosylation of Gi/o proteins. Interestingly, pertussis toxin abolished urocortin 3-induced Ca2+ response, indicating that in cardiac vagal neurons, pertussis toxin uncouples the G protein from the receptor and prevent ligand-mediated release of βγ subunit. This is not without precedent, as CRF2-mediated Ca2+ elevation in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells stably expressing human CRF2a was also sensitive to pertussis toxin (Gutnecht et al, 2009). On the other hand, Gs inhibition by cholera toxin markedly reduced the CRF2-mediated response in HEK293 cells stably expressing cells (Gutnecht et al, 2009), but did not affect the response in our cell model, indicating differences in signaling mechanisms between the two cell systems.

To verify whether or not PLC is involved in the response to urocortin 3, we examined the sensitivity of urocortin-3-induced Ca2+ increase to inhibition of PLC with U-73122; U-73122 inhibited the response to urocortin 3. Similarly, activation of CRF2 produced a PLC-mediated increase in cytosolic Ca2+ in CRF2-expressing HEK293 cells (Dautzenberg et al., 2004) and in dopamine neurons of the ventral tegmental area (Ungless et al., 2003).

In neurons, similar to other cells, an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ may be produced by Ca2+ influx or Ca2+ release from internal stores (Berridge, 1998). Using selective Ca2+ channels blockers, we identified that urocortin 3-induced Ca2+ response was reduced by ω-conotoxin MVIIC, a blocker of P/Q Ca2+ channels (Terlau et al., 2004), but not significantly affected by ω-conotoxin GVIA, a blocker of N-type Ca2+ channels or by nifedipine, a L-type Ca2+ channels blocker. Similarly, a previous study indicates that voltage-gated Ca2+ currents in premotor cardiac parasympathetic NA neurons comprise nearly entirely of the P/Q type (Irnaten et al., 2003).

The main internal Ca2+ store is the endoplasmic reticulum; Ca2+ release from ER occurs through inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors or ryanodine receptors (Berridge et al., 2002). The increase in Ca2+ produced by urocortin 3 was sensitive to thapsigargin, an inhibitor of sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (Treiman et al., 1998), indicating the endoplasmic reticulum as the major Ca2+ source mobilized by urocortin 3 in these neurons, as previously reported in CRF2-expressing cells (Gutknecht et al., 2009).

We further assessed the contribution of IP3 and ryanodine receptors by using selective antagonists. Urocortin 3-induced [Ca2+]i elevation was abolished by IP3 receptor inhibitors 2-APB (Maruyama et al., 1997) and xestospongin C (Gafni et al., 1997), but not affected by ryanodine receptor blockade. The finding that Ca2+ release in response to urocortin 3 occurs primarily through the IP3 receptors in cardiac vagal neurons of nucleus ambiguus, is similar to previous reports in dopamine-neurons (Ungless et al., 2003) or 2+ CRF2-transfected cells (Dautzenberg et al., 2004; Gutknecht et al., 2009). As the Ca response to urocortin 3 was abolished by pertussis toxin and U-73122, the increase in IP3 and subsequential IP3R activation may be due to the activation of PLCβ by the βγ subunit (Koch et al., 1994; Gutknecht et al., 2009).

Cardiac projecting preganglionic neurons of nucleus ambiguus have a cholinergic phenotype (Bouairi et al., 2006); activation of these neurons stimulates the release of acetylcholine in cardiac vagal terminals and consequently decreases the heart rate (Mendelowitz, 1999). Our results indicate that urocortin 3 acting on CRF2 in nucleus ambiguus activates these neurons and produces Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ release from internal stores; this is a possible cellular mechanism for the previously reported bradycardia produced by microinjection of urocortin 3 in nucleus ambiguus (Chitravanshi and Sapru, 2007). In addition, microinjection of urocortin1 into the rat nucleus ambiguus elicits bradycardia via CRF1 activation (Chitravanshi and Sapru, 2011). Interestingly, unlike other brain regions, where activation of CRF1 and CRF2 has opposing effects (Bale and Vale, 2004), in nucleus ambiguus, they lead to the same effect. The interplay between CRF1 and CRF2 has been studied in other brain regions. For example, in the dorsal raphe neurons, which have both CRF1 and CRF2 receptors, activation of CRF1 by CRF results in the recruitment of CRF2 to the plasma membrane (Waselus et al., 2009; Valentino et al., 2010) and thus urocortins could activate CRF2. Stress may induce the intracellular redistribution of CRF1/CRF2 between cytosol and plasma membrane and consequent modulation of the cellular response (Waselus et al., 2009). Whether or not a similar mechanism is involved in the effects of CRF/urocortins in the nucleus ambiguus is not currently known.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant HL090804 (EB) from the Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interests.

References

- Bale TL, Vale WW. CRF and CRF receptors: role in stress responsivity and other behaviors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:525–557. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Neuronal calcium signaling. Neuron. 1998;21:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. The endoplasmic reticulum: a multifunctional signaling organelle. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:235–249. doi: 10.1016/s0143416002001823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank T, Nijholt I, Grammatopoulos DK, Randeva HS, Hillhouse EW, Spiess J. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors couple to multiple G-proteins to activate diverse intracellular signaling pathways in mouse hippocampus: role in neuronal excitability and associative learning. J Neurosci. 2003;23:700–707. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00700.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouairi E, Kamendi H, Wang X, Gorini C, Mendelowitz D. Multiple types of GABAA receptors mediate inhibition in brain stem parasympathetic cardiac neurons in the nucleus ambiguus. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:3266–3272. doi: 10.1152/jn.00590.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu E, Hoard JL, Filipeanu CM, Brailoiu GC, Dun SL, Patel S, Dun NJ. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate potentiates neurite outgrowth. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5646–5650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408746200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu GC, Brailoiu E, Parkesh R, Galione A, Churchill GC, Patel S, Dun NJ. NAADP-mediated channel ‘chatter’ in neurons of the rat medulla oblongata. Biochem J. 2009;419:91–97. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081138. 92 p following 97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu GC, Deliu E, Hooper R, Dun NJ, Undieh AS, Adler MW, Benamar K, Brailoiu E. Agonist-selective effects of opioid receptor ligands on cytosolic calcium concentration in rat striatal neurons. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:277–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers DT, Lovenberg TW, De Souza EB. Localization of novel corticotropin-releasing factor receptor (CRF2) mRNA expression to specific subcortical nuclei in rat brain: comparison with CRF1 receptor mRNA expression. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6340–6350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06340.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitravanshi VC, Sapru HN. Bradycardic effects of microinjections of urocortin-III into the nucleus ambiguus in the rat [abstract] The FASEB Journal. 2007;21:750.14. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00224.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitravanshi VC, Sapru HN. Microinjections of urocortin1 into the nucleus ambiguus of the rat elicit bradycardia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H223–229. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00391.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CP, Qiu DL, Kato K, Kunitake T, Watanabe S, Yu NS, Nakazato M, Kannan H. Central stresscopin modulates cardiovascular function through the adrenal medulla in conscious rats. Regul Pept. 2004;119:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautzenberg FM, Dietrich K, Palchaudhuri MR, Spiess J. Identification of two corticotropin-releasing factor receptors from Xenopus laevis with high ligand selectivity: unusual pharmacology of the type 1 receptor. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1640–1649. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautzenberg FM, Gutknecht E, Van der Linden I, Olivares-Reyes JA, Durrenberger F, Hauger RL. Cell-type specific calcium signaling by corticotropin-releasing factor type 1 (CRF1) and 2a (CRF2(a)) receptors: phospholipase C-mediated responses in human embryonic kidney 293 but not SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1833–1844. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emeto TI, Moxon JV, Rush C, Woodward L, Golledge J. Relevance of urocortins to cardiovascular disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafni J, Munsch JA, Lam TH, Catlin MC, Costa LG, Molinski TF, Pessah IN. Xestospongins: potent membrane permeable blockers of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Neuron. 1997;19:723–733. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainetdinov RR, Premont RT, Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors and neuronal functions. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:107–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutknecht E, Van der Linden I, Van Kolen K, Verhoeven KF, Vauquelin G, Dautzenberg FM. Molecular mechanisms of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor-induced calcium signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:648–657. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauger RL, Grigoriadis DE, Dallman MF, Plotsky PM, Vale WW, Dautzenberg FM. International Union of Pharmacology. XXXVI. Current status of the nomenclature for receptors for corticotropin-releasing factor and their ligands. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:21–26. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse EW, Grammatopoulos DK. The molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of the biological activity of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptors: implications for physiology and pathophysiology. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:260–286. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY, Hsueh AJ. Human stresscopin and stresscopin-related peptide are selective ligands for the type 2 corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor. Nat Med. 2001;7:605–611. doi: 10.1038/87936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irnaten M, Aicher SA, Wang J, Venkatesan P, Evans C, Baxi S, Mendelowitz D. Mu-opioid receptors are located postsynaptically and endomorphin-1 inhibits voltage-gated calcium currents in premotor cardiac parasympathetic neurons in the rat nucleus ambiguus. Neuroscience. 2003;116:573–582. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00657-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang G, Joseph JW, Chepurny OG, Monaco M, Wheeler MB, Bos JL, Schwede F, Genieser HG, Holz GG. Epac-selective cAMP analog 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP as a stimulus for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and exocytosis in pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8279–8285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211682200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz A, Wu D, Simon MI. Subunits beta gamma of heterotrimeric G protein activate beta 2 isoform of phospholipase C. Nature. 1992;360:686–689. doi: 10.1038/360686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto T, Pearse RV, 2nd, Lin CR, Rosenfeld MG. A sauvagine/corticotropin-releasing factor receptor expressed in heart and skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1108–1112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch WJ, Hawes BE, Inglese J, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Cellular expression of the carboxyl terminus of a G protein-coupled receptor kinase attenuates G beta gamma-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6193–6197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostich WA, Chen A, Sperle K, Largent BL. Molecular identification and analysis of a novel human corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) receptor: the CRF2gamma receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1077–1085. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.8.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AJ, Krstew EV, Dautzenberg FM, Ruhmann A. The highly selective CRF(2) receptor antagonist K41498 binds to presynaptic CRF(2) receptors in rat brain. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:896–904. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K, Li C, Perrin MH, et al. Identification of urocortin III, an additional member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) family with high affinity for the CRF2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7570–7575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121165198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Vaughan J, Sawchenko PE, Vale WW. Urocortin III-immunoreactive projections in rat brain: partial overlap with sites of type 2 corticotrophin-releasing factor receptor expression. J Neurosci. 2002;22:991–1001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00991.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Fan M, Shen L, Cao Y, Zhu D, Hong Z. Excitatory responses of cardiovascular activities to urocortin3 administration into the PVN of the rat. Auton Neurosci. 2010;154:108–111. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovenberg TW, Chalmers DT, Liu C, De Souza EB. CRF2 alpha and CRF2 beta receptor mRNAs are differentially distributed between the rat central nervous system and peripheral tissues. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4139–4142. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.9.7544278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Kanaji T, Nakade S, Kanno T, Mikoshiba K. 2APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate, a membrane-penetrable modulator of Ins(1,4,5)P3-induced Ca2+ release. J Biochem. 1997;122:498–505. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelowitz D. Firing properties of identified parasympathetic cardiac neurons in nucleus ambiguus. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H2609–2614. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelowitz D. Advances in Parasympathetic Control of Heart Rate and Cardiac Function. News Physiol Sci. 1999;14:155–161. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1999.14.4.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelowitz D, Kunze DL. Identification and dissociation of cardiovascular neurons from the medulla for patch clamp analysis. Neurosci Lett. 1991;132:217–221. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(91)90305-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Sapru HN. Cardiovascular responses to microinjections of urocortins into the NTS: role of inotropic glutamate receptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H2022–2029. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00191.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikawa H, Nakamichi N, Kambe Y, Ogura M, Yoneda Y. An increase in intracellular free calcium ions by nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in a single cultured rat cortical astrocyte. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:535–544. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernar L, Curtis AL, Vale WW, Rivier JE, Valentino RJ. Selective activation of corticotropin-releasing factor-2 receptors on neurochemically identified neurons in the rat dorsal raphe nucleus reveals dual actions. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1305–1311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2885-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primus RJ, Yevich E, Baltazar C, Gallager DW. Autoradiographic localization of CRF1 and CRF2 binding sites in adult rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;17:308–316. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes BA, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Stress-induced intracellular trafficking of corticotropin-releasing factor receptors in rat locus coeruleus neurons. Endocrinology. 2008;149:122–130. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto R. Intracellular Ca(2+) pools in neuronal signalling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:306–311. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling L, Kanzler C, Schmiedek P, Ehrenreich H. Characterization of the relaxant action of urocortin, a new peptide related to corticotropin-releasing factor in the rat isolated basilar artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;125:1164–1171. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoniger S, Wehming S, Gonzalez C, Schobitz K, Rodriguez E, Oksche A, Yulis CR, Nurnberger F. The dispersed cell culture as model for functional studies of the subcommissural organ: preparation and characterization of the culture system. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;107:47–61. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00351-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlau H, Olivera BM. Conus venoms: a rich source of novel ion channel-targeted peptides. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:41–68. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiman M, Caspersen C, Christensen SB. A tool coming of age: thapsigargin as an inhibitor of sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:131–135. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungless MA, Singh V, Crowder TL, Yaka R, Ron D, Bonci A. Corticotropin-releasing factor requires CRF binding protein to potentiate NMDA receptors via CRF receptor 2 in dopamine neurons. Neuron. 2003;39:401–407. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Lucki I, Van Bockstaele E. Corticotropin-releasing factor in the dorsal raphe nucleus: Linking stress coping and addiction. Brain Res. 2010;1314:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Pett K, Viau V, Bittencourt JC, et al. Distribution of mRNAs encoding CRF receptors in brain and pituitary of rat and mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428:191–212. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001211)428:2<191::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waselus M, Nazzaro C, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Stress-induced redistribution of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor subtypes in the dorsal raphe nucleus. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waselus M, Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele EJ. Collateralized dorsal raphe nucleus projections: a mechanism for the integration of diverse functions during stress. J Chem Neuroanat. 2011;41:266–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LZ, Tovote P, Rayner M, Kockskamper J, Pieske B, Spiess J. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors and urocortins, links between the brain and the heart. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;632:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]