Abstract

Brain edema after ischemic brain injury is a key determinant of morbidity and mortality. Aquaporin-4 (AQP4) plays an important role in water transport in the central nervous system and is highly expressed in brain astrocytes. However, the AQP4 regulatory mechanisms are poorly understood. In this study, we investigated whether mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), which are involved in changes in osmolality, might mediate AQP4 expression in models of rat cortical astrocytes after ischemia. Increased levels of AQP4 in primary cultured astrocytes subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) and 2 h of reoxygenation were observed, after which they immediately decreased at 0 h of reoxygenation. Astrocytes exposed to OGD injury had significantly increased phosphorylation of three kinds of MAPKs. Treatment with SB203580, a selective p38 MAPK inhibitor, or SP600125, a selective c-Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitor, significantly attenuated the return of AQP4 to its normal level, and SB203580, but not SP600125, significantly decreased cell death. In an in vivo study, AQP4 expression was upregulated 1–3 days after reperfusion, which was consistent with the time course of p38 phosphorylation and activation, and decreased by the p38 inhibition after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). These results suggest that p38 MAPK may regulate AQP4 expression in cortical astrocytes after ischemic injury.

Key words: aquaporin-4, astrocyte, brain edema, ischemia, mitogen-activated protein kinase

Introduction

Ischemia is critically involved in brain edema formation. Edema is a major risk factor for life-threatening complications after ischemia, and its treatment is currently limited. It has been classified into two main types: cellular (cytotoxic) and vasogenic (Klatzo, 1994). Aquaporin-4 (AQP4), which is the predominant subtype in the central nervous system, plays an important role in water transport and is expressed in brain astrocyte end-feet (Nielsen et al., 1997; Tait et al., 2008). Astrocytes swell in both types of edema. Studies indicate that modulating AQP4 expression in astrocytes may play a role in a new therapeutic strategy for reducing cerebral edema (Hirt et al., 2009; Manley et al., 2000; Verkman, 2005). However, the regulatory mechanisms of AQP4 are poorly understood.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) have crucial roles in signal translocation from the cell surface to the nucleus by regulating cell death and survival. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) is activated in response to several kinds of growth factors, intracellular calcium increases, and glutamate receptor stimulation. In contrast, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 MAPK are activated in response to a variety of cellular stresses, such as DNA damage, heat shock protein, or inflammatory cytokines, and they modulate the expression of several transcriptional factors. Several studies in animal models have shown that expression of or the phosphorylation level of MAPKs change in ischemic brain tissue, and that inhibition of MAPK pathways can alter the outcome of ischemic brain injury by regulation of cell death or survival (Ferrer et al., 2003; Irving and Bamford, 2002; Nozaki et al., 2001; Sugino et al., 2000). MAPKs are also important signal transduction pathways involved in changes in osmolality (Crépel et al., 1998; Han et al., 1994; Jayakumar et al., 2006). Some studies have shown that expression of aquaporins-1, -4, -5, and -9 is regulated by MAPKs in response to changes in osmolality (Arima et al., 2003; Hoffert et al., 2000; Rao et al., 2010; St. Hillaire et al., 2005; Umenishi and Schrier, 2003), and it has also been reported that hyperosmotic stress increases AQP4 through a p38 MAPK-dependent pathway in cultured rat astrocytes (Arima et al., 2003).

We examined the role of the MAPK pathways in AQP4 regulation in rat primary astrocytes using oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) injury, and the immunoreactivity of p38 MAPK and AQP4 in brain edema formation after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in rats. We hypothesized that MAPK pathways, especially p38 MAPK, mediate AQP4 expression in cortical astrocytes after in vitro and in vivo ischemic brain injuries.

Materials and Methods

Primary cortical astrocyte cultures

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care of Stanford University, and were conducted in accordance with the recommendations provided in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Astrocyte cultures were prepared from the cerebral cortices of post-natal (days 1–2) Sprague-Dawley rats as described previously (Dugan et al., 1995; Lee et al., 2006). Briefly, cerebral cortices freed of meninges were incubated in 0.25% trypsin, diluted in Eagle's minimal essential medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min at 37°C, then mechanically dissociated. The dissociated neocortical cells were plated at a density of 1–1.5 hemispheres per multi-well in Eagle's minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% equine serum, 10% fetal bovine serum, 21 mmol/L (final concentration) glucose, and 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor. Cultures were maintained in a 37°C humidified incubator with 5% CO2 in room air.

Oxygen-glucose deprivation

The culture medium was replaced with deoxygenated glucose- and serum-free balanced salt solution (BSS0), pH 7.4, containing phenol red (10 mg/L), and the following (in mmol/L): NaCl 116, CaCl2 1.8, MgSO4 0.8, KCl 5.4, NaH2PO4 1, NaHCO3 14.7, and HEPES 10. Oxygenated BSS5.5 containing 5.5 mmol/L glucose in BSS was used for uninjured controls incubated in a normoxic incubator. The cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of SB203580, PD98059, SP600125 (1 μM or 10 μM; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), or dimethyl sulfoxide, prior to OGD injury. Cultures were incubated at 37°C in the anaerobic chamber in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, 5% H2, and 90% N2 (O2<0.1%) for 6 h. OGD was ended by adding glucose to the culture medium to a final concentration of 5.5 mmol/L and returning the cultures to the normoxic chamber.

Western blot analysis

Cells were collected and sonicated in homogenizing buffer (250 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4] with KOH, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail). The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 4°C at 1000 g to remove unbroken cells and debris. The resulting supernatant was quantified and used for immunoblots of MAPKs and phosphorylated MAPKs. The cell pellets were resuspended in homogenizing buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and recentrifuged for 60 min at 100,000g to obtain membrane fractions for AQP4. Protein concentrations were determined and equal amounts of the samples (with equal volumes of Tris- glycine sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer) were loaded per lane. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed on a Tris-glycine gel (Invitrogen), and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Invitrogen). The membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against AQP4 (1:1000; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), phospho-p38 (p-p38, 1:750), p38 (1:1000), phospho-p44/42 (1:2000), p44/42 (1:1000), phospho-stress-activated protein kinase/JNK (1:2000), stress-activated protein kinase/JNK (1:1000; all from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, and then the signal was detected with chemiluminescence Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham International, Buckinghamshire, U.K.). The film was scanned with an imaging densitometer (GS-700; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), and the optical density was quantified using Multi-Analyst software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Immunoprecipitation and kinase assays

p38, ERK, or JNK activity was measured with immune complex protein kinase assays, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Cell Signaling Technology). Equal amounts of protein prepared from each tissue homogenate were incubated with immobilized p-p38 MAPK monoclonal antibody, phosphorylated 44/42 monoclonal antibody, or c-Jun fusion protein beads, with gentle rocking overnight at 4°C. After washing the beads and centrifugation, the pellets were suspended in kinase buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5 mM glycerol phosphate, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, and 10 mM MgCl2) supplemented with adenosine triphosphate, and then exogenous activating transcription factor (ATF)-2, Elk-1, or c-Jun fusion protein was used as a substrate for the p38, ERK, and JNK assays, respectively, at 30°C for 30 min. Phosphorylation of ATF-2, Elk-1, or c-Jun was measured by Western blotting.

Lactate dehydrogenase assay

Cell death was determined after 24 h of recovery in the normoxic incubator using a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay (Koh and Choi, 1987). The medium was sampled at 24 h of reoxygenation. Astrocytes were then frozen/thawed to provide the maximum LDH release values (full-kill numbers). The percentage of death (% of LDH release) was calculated by dividing the experimental time point by the full-kill values×100.

Focal cerebral ischemia

During surgical preparation, male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in a mixture of 70% N2O and 30% O2 with spontaneous breathing. The left external carotid artery was exposed through a midline cervical incision and its branches were electrocoagulated. A 22-mm 3-0 surgical monofilament nylon suture, blunted at the end, was introduced into the left internal carotid artery through the external carotid artery stump, per our previous report (Okuno et al., 2004). Body temperature was maintained at 37°C using a heating pad during the surgical procedure for MCAO. After 90 min of MCAO, cerebral blood flow was restored by removal of the nylon thread. Blood samples were collected from the tail artery before and during MCAO and just after reperfusion for measurement of pH, Po2, and Pco2. Sham control animals were treated in the same way without MCAO. The animals were killed by decapitation at 24 h and 1, 3, and 7 days of reperfusion.

Drug injection

For intracranial surgery, the rats were anesthetized and placed on a stereotaxic apparatus. The scalp was incised on the midline and the skull was exposed. Thirty minutes before the ischemic insult, a total of 10 μL of 100 μM of SB203580 (100 μM dissolved in 1% dimethyl sulfoxide), a specific p38 inhibitor (Calbiochem), or vehicle (1% dimethyl sulfoxide), were injected stereotaxically into the right lateral cerebroventricle (coordinates with reference to the bregma: 1.4 mm lateral, 0.8 mm posterior, 3.6 mm deep) using a 26-G Hamilton microsyringe (80330; Hamilton Company, Reno, NV).

2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining

The animals were decapitated at 3 days of reperfusion and the brains were cut into 2-mm cortical slices. The slices were stained by immersion in 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride at 37°C and fixed in 10% buffered formalin overnight. The area of ischemic lesion for each section was quantified according to the indirect method and analyzed using an image analysis system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Edema volume was determined by subtracting the non-ischemic cortical or striatal volume from the ischemic volume (Maier et al., 1998).

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni/Dunn post-hoc test. A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

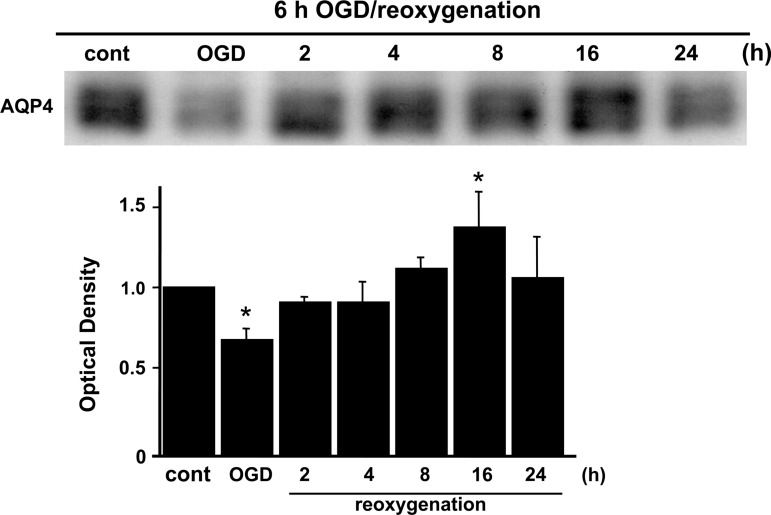

AQP4 expression after OGD

To study the water channel protein in rat cortical astrocytes after OGD, Western blots were performed. Slight AQP4 expression was seen in control cells (Fig. 1). After OGD injury, AQP4 expression was significantly decreased at 0 h, immediately after OGD and before the start of reoxygenation compared with controls, with increased expression seen 2 h after reoxygenation, and gradual recovery during reoxygenation, as detected by immunoblotting. AQP4 was significantly upregulated at 16 h compared with controls (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Western blot analysis of the water channel protein in rat cortical astrocytes that underwent OGD/reoxygenation. Expression of AQP4 was significantly decreased by OGD injury, but gradually recovered after reoxygenation. AQP4 was significantly upregulated at 16 h. Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation of three independent experiments (*p<0.01 compared with control [cont]; ODG, oxygen-glucose deprivation; AQP4, aquaporin-4).

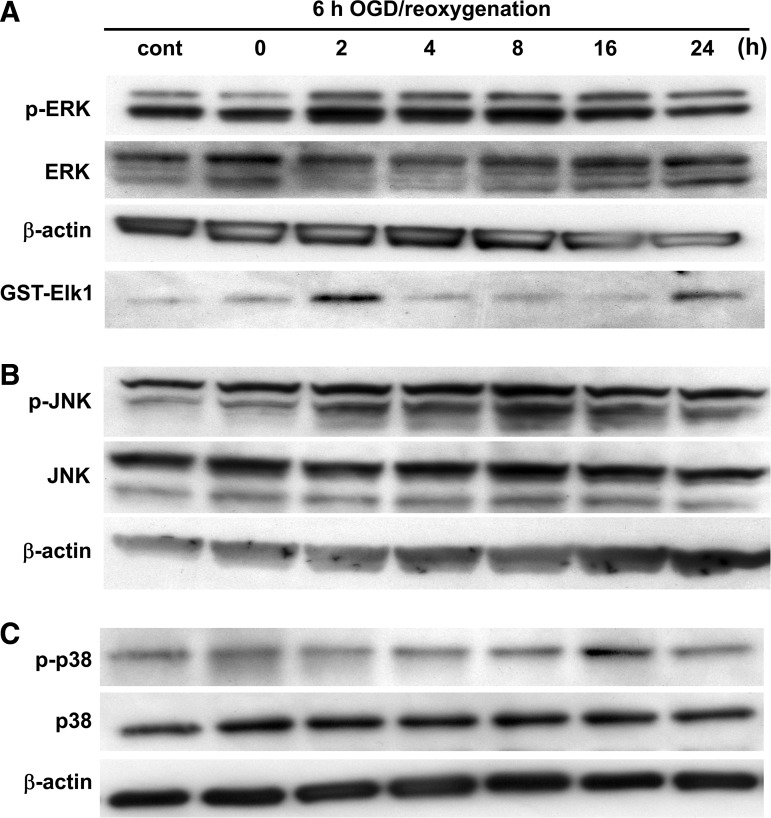

Involvement of MAPKs in cortical astrocytes after OGD

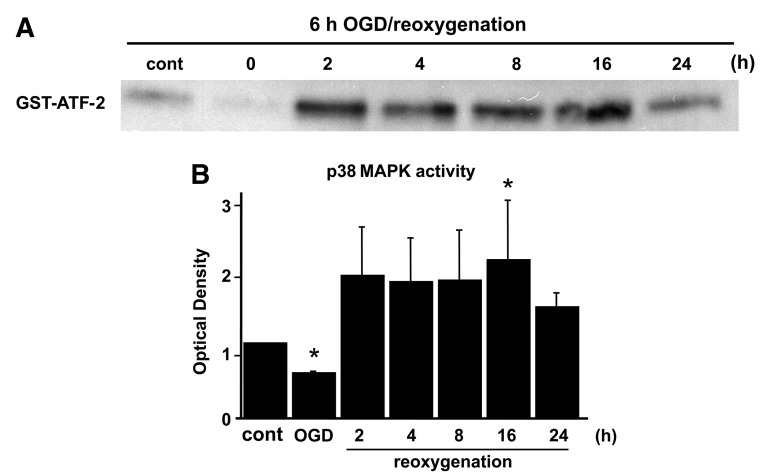

To analyze the contribution of MAPKs after OGD, ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 were examined by measuring levels of phosphorylation and activation on immunoblotting. Phosphorylation of ERK and JNK was gradually increased after OGD, and decreased at 16 h of reoxygenation (Fig. 2A and B). The protein level of p-p38 was increased at 16 h of reoxygenation, and decreased by 24 h after reoxygenation (Fig. 2C). An ERK1/2 activity assay demonstrated that ERK1/2 activation was quickly increased at 2 h and decreased by 4 h after reoxygenation (Fig. 2A). Activation of p38 was gradually increased after reoxygenation, and the peak level of expression was seen at 16 h (Fig. 3A and B), consistent with the Western blot results for AQP4 (Fig. 1). JNK activation was not detected in the astrocytes after OGD.

FIG. 2.

Changes in the levels of phospho-ERK1/2 (p-ERK) and ERK1/2 (A) or phospho-JNK (p-JNK) and JNK (B) in rat cortical astrocytes during reoxygenation after 6 h of OGD. Changes in the levels of p-p38 and p38 MAPK (C) in rat cortical astrocytes during reoxygenation after 6 h of OGD. ERK1/2 activity (A) was also examined after reoxygenation. Tissue homogenates were subjected to kinase assays using GST-Elk-1 as the substrate (cont, control; GST, glutathione S-transferase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; OGD, oxygen-glucose deprivation; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase).

FIG. 3.

(A) p38 MAPK activity was examined after reoxygenation. Tissue homogenates were subjected to kinase assays using GST-ATF-2 as the substrate. Activation of p38 was gradually increased after reoxygenation and the peak level of expression occurred at 16 h. (B) Quantitative analysis showed that activation of p38 increased significantly 16 h after reoxygenation compared with the control (cont). Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation of four independent experiments (*p<0.05 compared with control; GST, glutathione S-transferase; ATF-2, activating transcription factor-2; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase).

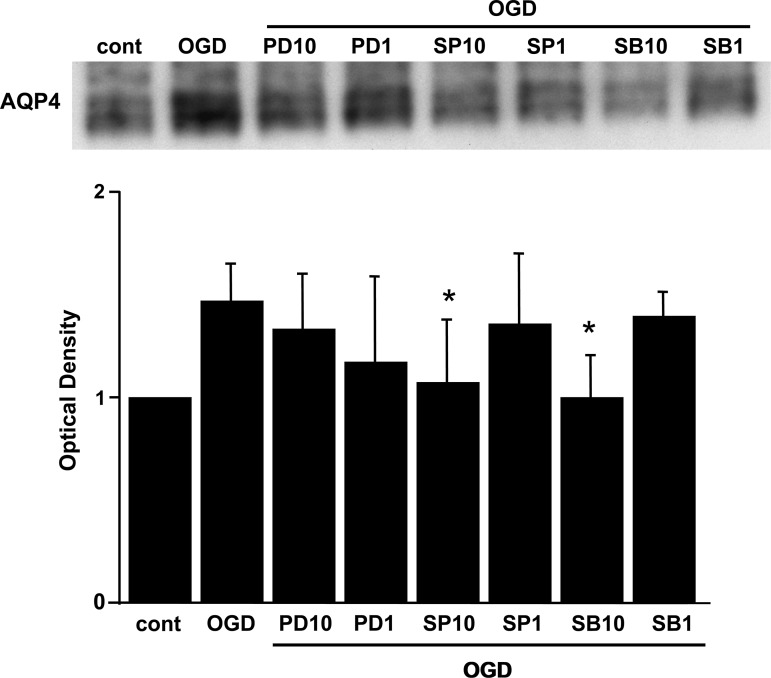

To confirm the role of these MAPKs with the water channel protein, we compared the effects of various MAPK inhibitors (PD98059, SP600125, and SB203580) on the expression of AQP4 after OGD injury. Sixteen hours after reoxygenation, the AQP4 level was determined by Western blot analysis. Pretreatment with 10 μM of SB203580 (the p38 kinase inhibitor), or 10 μM of SP600125 (the JNK inhibitor), but not 1 μM of SP600125, significantly reduced AQP4 expression to the basal level 16 h after reoxygenation (Fig. 4). In contrast, 1 μM or 10 μM of PD98059 (the MAPK/ERK1 inhibitor, the upstream kinase specific for ERK1/2) did not induce any change in AQP4 expression (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

The cells were treated with 10 μM or 1 μM of PD98059, SP600125, or SB203580, before OGD. Sixteen hours after reoxygenation, the AQP4 level was determined by Western blot analysis. Ten micromoles of SB203580 or SP600125 significantly suppressed expression of AQP4 to the basal level 16 h after reoxygenation. Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation of four independent experiments (*p<0.05 compared with the OGD group; cont, control; ODG, oxygen-glucose deprivation; AQP4, aquaporin-4; PD10, 10 μM PD98059; PD1, 1 μM PD98059; SP10, 10 μM SP600125; SP1, 1 μM SP600125; SB10, 10 μM SB203580; SB1, 1 μM SB203580).

An association between AQP4 inhibition and a reduction in astrocyte death by the p38 inhibitor SB203580

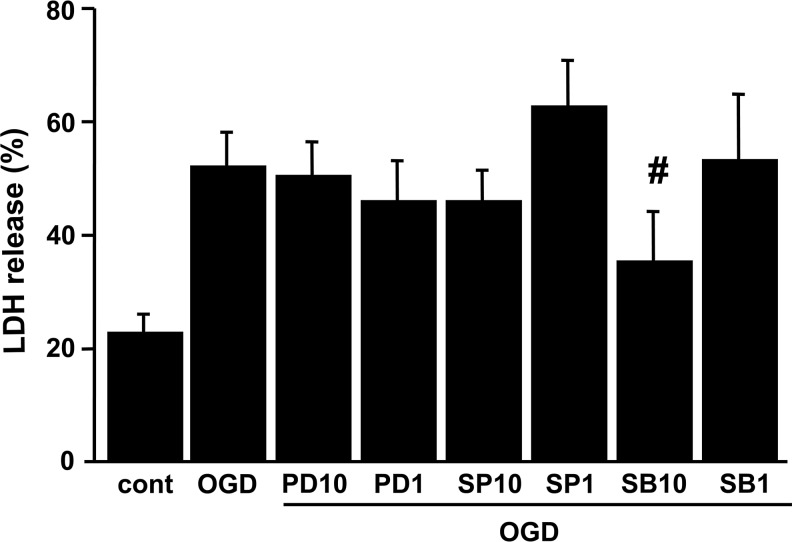

We then determined whether inhibiting AQP4 upregulation affects OGD-induced cell death. OGD was terminated by the addition of oxygen and glucose to the medium (reoxygenation). The medium was then sampled for LDH release as a measure of cell injury. Six hours of OGD resulted in 51.5% cell death in the rat cortical astrocytes (Fig. 5). Although the other two MAPK inhibitors offered no protection, treatment with 10 μM of SB203580 (the p38 kinase inhibitor) significantly protected the rat astrocytes, reducing cell death to 34.9% after OGD (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

LDH release after OGD injury in rat cortical astrocytes. Cells were subjected to 6 h of OGD, followed by 24 h of reoxygenation. Cell death was assessed by LDH release. SB203580 (10 μM) significantly reduced OGD-induced cell death. Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in triplicate (#p<0.05 compared with the OGD group; cont, control; PD10, 10 μM PD98059; PD1, 1 μM PD98059; SP10, 10 μM SP600125; SP1, 1 μM SP600125; SB10, 10 μM SB203580; SB1, 1 μM SB203580; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; OGD, oxygen-glucose deprivation).

The p38 inhibitor SB203580 restored AQP4 expression and attenuated edema and infarct volumes after transient focal cerebral ischemia

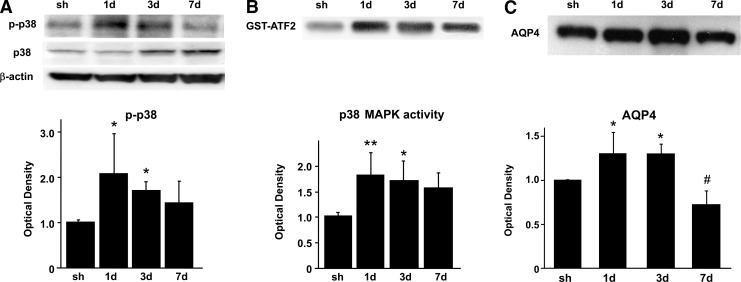

We then examined activation and phosphorylation of p38 and expression of AQP4 in the rat brains after transient focal cerebral ischemia. For the Western blot analysis, we used a specific antibody against p-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) and p38. The protein level of p38 phosphorylation was also significantly increased from 1–3 days after reperfusion (Fig. 6A). Expression of total p38 was sustained at the same level until 1 day, and was markedly increased from 3–7 days (Fig. 6A). p38 activation, as examined by phosphorylation of ATF-2, a downstream substrate of p38 signaling, was significantly increased from 1–3 days after reperfusion and peaked at 1 day (Fig. 6B). The AQP4 protein level was markedly increased 1–3 days after reperfusion and decreased at 7 days (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

(A) Western blot analysis of p-p38 and p38 in the rat cortex 1, 3, and 7 days after focal ischemia. After 90 min of MCAO, expression of p-p38 was increased from day 1 to day 3. (B) p38 MAPK activity (GST-ATF-2) was examined 1, 3, and 7 days after 90 min of MCAO. Activation of p38 was increased maximally on day 1. (C) Western blot analysis of AQP4 in the rat cortex 1, 3, and 7 days after focal ischemia. After 90 min of MCAO, AQP4 protein levels continued to increase significantly until 3 days. AQP4 expression was significantly decreased at 7 days. Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (*p<0.05, **p<0.001, #p<0.05 compared with the sham group; sh, sham; GST, glutathione S-transferase; MCAO, middle cerebral artery occlusion; AQP4, aquaporin-4; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; ATF-2, activating transcription factor-2).

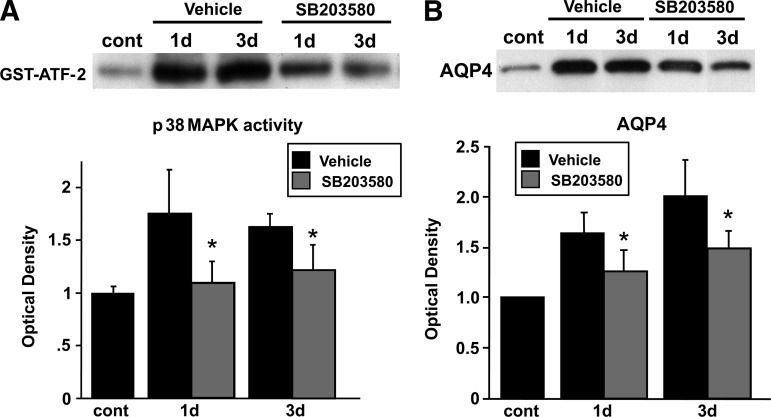

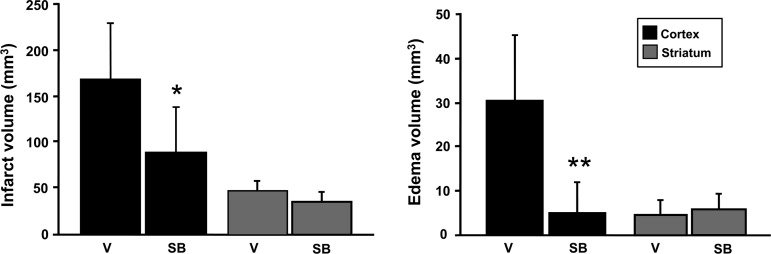

Administration of SB203580 significantly attenuated p38 MAPK activity, as observed by decreased phosphorylation of ATF-2, 1 and 3 days after reperfusion (Fig. 7A), without affecting p38 MAPK phosphorylation (data not shown), because the phosphorylated form of ATF-2, but not p38, is inhibited by SB203580. SB203580 inhibits the phosphorylation of ATF-2, which is a downstream substrate of p-p38 (Larsen et al., 1997). AQP4 expression was decreased and restored to the normal level by the p38 inhibitor 1–3 days after reperfusion (Fig. 7B). p38 inhibition significantly attenuated infarct and edema volumes in the cortex 3 days after transient focal cerebral ischemia in the treated rats compared with their untreated counterparts (Fig. 8).

FIG. 7.

(A) Suppression of p38 MAPK activity by administration of SB203580. p38 MAPK activity was examined 1 and 3 days after reperfusion with or without SB203580 administration. SB203580 was administered 30 min before ischemic insult, and phosphorylation of ATF-2, a downstream substrate, was examined by Western blot analysis. (B) Suppression of AQP4 expression in SB203580-treated animals. Expression of AQP4 with or without SB203580 administration was examined by Western blot analysis. Values are mean±standard deviation (n=4 in each group; *p<0.05 for the SB203580-treated groups versus the vehicle-treated groups; GST, glutathione S-transferase; cont, control; ATF-2, activating transcription factor-2; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; AQP4, aquaporin-4).

FIG. 8.

Infarct volume and edema volume 3 days after transient focal cerebral ischemia in vehicle-treated and SB203580-treated rats (n=6 each; *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared with ischemic controls; V, vehicle-treated rats; SB, SB203580-treated rats).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that AQP4 and three kinds of MAPKs were significantly upregulated after OGD, that the relatively selective p38 inhibitor SB203580 normalized AQP4 expression to basal levels, and that p38 inhibition by SB203580 reduced cell death in brain cortical astrocytes after OGD. We also found that p38 phosphorylation and AQP4 expression were decreased immediately after ischemia, but were concomitantly upregulated from 1–3 days after reperfusion in an in vivo study. Furthermore, inhibition of p38 reduced infarct and edema volumes, confirming our earlier report (Nito et al., 2008). These findings suggest that a key role for p38 in the mechanism of AQP4 might be mediation of water accumulation in the ischemic brain.

We demonstrated the time-dependent expression of AQP4 in cortical cultured astrocytes after ischemic-like conditions. AQP4 expression was significantly downregulated just after OGD, and then upregulated and restored to its normal level after reoxygenation. These data are consistent with previously reported findings (Yamamoto et al., 2001).

We also demonstrated that SB203580, an inhibitor of p38, reduced AQP4 expression, suggesting that p38 MAPK might be a dominant pathway mediating AQP4 expression in cerebral cortex astrocytes after OGD, and that the relatively selective p38 inhibitor SB203580 reduced cell death. In contrast, no effects on either AQP4 expression or cell survival were detectable when PD98059 was used to target the ERK1/2 pathways. One of the reasons why the ERK1/2 inhibitor failed to attenuate AQP4 expression compared with p38 inhibition might be the different expression time courses of AQP4 and ERK1/2. Activation of ERK1/2 occurred early, at 2 h, and then decreased at 4 h, whereas AQP4 expression continued to upregulate up to 16 h. Alternatively, the blockade of ERK1 only by PD98059 may not have been sufficient to regulate AQP4 and cell death after the ischemic insult. We detected phosphorylation and activation of JNK. A selective JNK inhibitor (SP600125) reduced AQP4 expression; however, the inhibition of JNK expression did not protect against cell death in this model. The partial inhibition of JNK may not be sufficient to inhibit cell death, because SP600125 prevented phosphorylation of JNK1, but not JNK2/3. Other studies have demonstrated that JNK inactivation by SP600125 was effective in decreasing neuronal apoptosis and death after in vivo ischemia. Our study was based in astrocytes in primary cultures, and this would explain the different results we obtained. In our model, the JNK1 pathway may not be involved in astrocytic death after ischemia.

Increased AQP4 expression in astrocytes has also been reported in several pathologies (for which cytotoxic edema is predominant), including stroke, traumatic brain injury, meningitis, and hyponatremia (Papadopoulos and Verkman, 2005). There is evidence of an increased synthesis of AQP4 in the peri-infarct area of the cortex at 24 h of reperfusion after MCAO (Frydenlund et al., 2006). However, while an increased level of AQP4 was observed in the penumbral region of the ischemic cortex, AQP4 expression was decreased in the striatal and cortical cortices (Frydenlund et al., 2006). In vivo studies have also shown that p38 MAPK pathways are activated after stroke, and that a delayed surge of p38β MAPK is induced in reactive astrocytes in the penumbral region after transient focal ischemia (Irving et al., 2000; Piao et al., 2002). Moreover, treatment with the p38 inhibitor SB203580 reduced infarct size and afforded brain protection after transient focal ischemia (Barone et al., 2001; Piao et al., 2002,2003), and reduced neuronal death in the CA1 region after transient global ischemia (Sugino et al., 2000).

In the present study, we found that activation and phosphorylation of p38 significantly increased from 1–3 days, and that AQP4 was also markedly upregulated in the cortical brain 1–3 days after reperfusion. Thus both exhibit a similar temporal pattern, suggesting that p38 phosphorylation may modulate AQP-mediated edema after ischemic insult. Moreover, inhibition of p38 decreased the AQP4 upregulation and reduced infarct and edema volumes. This is in contradiction to a report by Tait and colleagues (2010), in which they showed that AQP4 deletion increased brain edema following subarachnoid hemorrhage by reducing elimination of excess brain water. In fact, AQP4 upregulation is beneficial in the reduction of vasogenic edema and associated complications. In an earlier report by Manley and colleagues (2000), they demonstrated that edema after cerebral ischemia is reduced in AQP4-knockout mice. This difference may be due to the nature of injury and the model used. More detailed study and analyses of water movement after cerebral injury in the knockout mice may be necessary. Modulation of p38 has been shown to be neuroprotective and is possibly independent of AQP4-mediated edema. Some of the effects observed here may be indirect consequences of smaller infarcts and overall injury. Nevertheless, this study shows that AQP4 was inhibited by SB203580, a p38 inhibitor, suggesting that p38 may play an important role in AQP4 modulation after cerebral ischemia.

Several reports have been published about the pathophysiological role of AQP4 in brain injury involving protein kinase C (Fazzina et al., 2010; Nakahama et al., 1999; Yamamoto et al., 2001), nuclear factor-κB (Ito et al., 2006), and p38 MAPK (Arima et al., 2003; Rao et al., 2010; St. Hillaire et al., 2005). In one of these studies, Arima and colleagues (2003) suggested that p38 activation is necessary but not sufficient for AQP4 induction after brain injury.

In our study, we demonstrated that p38 MAPK may be a dominant pathway mediating AQP4 expression among three MAPKs, and that the effect of p38 inhibition reduced cell death in cerebral cortex astrocytes after both in vitro and in vivo ischemic injuries. Further studies are required to determine the regulation of AQP4 expression in astrocytes after injury and the role of AQP4 in the two types of brain edema seen after ischemia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants PO1 NS014543, RO1 NS025372, and RO1 NS038653, from the National Institutes of Health, and by the James R. Doty Endowment (to P.H.C.). We thank Liza Reola and Bernard Calagui for technical assistance, and Cheryl Christensen for editorial assistance.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Arima H. Yamamoto N. Sobue K. Umenishi F. Tada T. Katsuya H. Asai K. Hyperosmolar mannitol stimulates expression of aquaporins 4 and 9 through a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway in rat astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:44525–44534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone F.C. Irving E.A. Ray A.M. Lee J.C. Kassis S. Kumar S. Badger A.M. Legos J.J. Erhardt J.A. Ohlstein E.H. Hunter A.J. Harrison D.C. Philpott K. Smith B.R. Adams J.L. Parsons A.A. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase provides neuroprotection in cerebral focal ischemia. Med. Res. Rev. 2001;21:129–145. doi: 10.1002/1098-1128(200103)21:2<129::aid-med1003>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crépel V. Panenka W. Kelly M.E.M. MacVicar B.A. Mitogen-activated protein and tyrosine kinases in the activation of astrocyte volume-activated chloride current. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:1196–1206. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01196.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan L.L. Bruno V.M.G. Amagasu S.M. Giffard R.G. Glia modulate the response of murine cortical neurons to excitotoxicity: glia exacerbate AMPA neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:4545–4555. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04545.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzina G. Amorini A.M. Marmarou C.R. Fukui S. Okuno K. Dunbar J.G. Glisson R. Marmarou A. Kleindienst A. The protein kinase C activator phorbol myristate acetate decreases brain edema by aquaporin 4 downregulation after middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:453–461. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer I. Friguls B. Dalfó E. Planas A.M. Early modifications in the expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK/ERK), stress-activated kinases SAPK/JNK and p38, and their phosphorylated substrates following focal cerebral ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;105:425–437. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0661-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydenlund D.S. Bhardwaj A. Otsuka T. Mylonakou M.N. Yasumura T. Davidson K.G.V. Zeynalov E. Skare Ø. Laake P. Haug F.-M. Rash J.E. Agre P. Ottersen O.P. Amiry-Moghaddam M. Temporary loss of perivascular aquaporin-4 in neocortex after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:13532–13536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605796103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J. Lee J.-D. Bibbs L. Ulevitch R.J. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science. 1994;265:808–811. doi: 10.1126/science.7914033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirt L. Ternon B. Price M. Mastour N. Brunet J.-F. Badaut J. Protective role of early aquaporin 4 induction against postischemic edema formation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:423–433. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffert J.D. Leitch V. Agre P. King L.S. Hypertonic induction of aquaporin-5 expression through an ERK-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:9070–9077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.9070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving E.A. Bamford M. Role of mitogen- and stress-activated kinases in ischemic injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:631–647. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200206000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving E.A. Barone F.C. Reith A.D. Hadingham S.J. Parsons A.A. Differential activation of MAPK/ERK and p38/SAPK in neurones and glia following focal cerebral ischaemia in the rat. Mol. Brain Res. 2000;77:65–75. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H. Yamamoto N. Arima H. Hirate H. Morishima T. Umenishi F. Tada T. Asai K. Katsuya H. Sobue K. Interleukin-1β induces the expression of aquaporin-4 through a nuclear factor-κB pathway in rat astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 2006;99:107–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar A.R. Panickar K.S. Murthy C.R.K. Norenberg M.D. Oxidative stress and mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation mediate ammonia-induced cell swelling and glutamate uptake inhibition in cultured astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:4774–4784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0120-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatzo I. Evolution of brain edema concepts. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 1994;60:3–6. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9334-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh J.Y. Choi D.W. Quantitative determination of glutamate mediated cortical neuronal injury in cell culture by lactate dehydrogenase efflux assay. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1987;20:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(87)90041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen J.K. Yamboliev I.A. Weber L.A. Gerthoffer W.T. Phosphorylation of the 27-kDa heat shock protein via p38 MAP kinase and MAPKAP kinase in smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 1997;273:L930–L940. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.5.L930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.-S. Song Y.S. Giffard R.G. Chan P.H. Biphasic role of nuclear factor-κB on cell survival and COX-2 expression in SOD1 Tg astrocytes after oxygen glucose deprivation. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1076–1088. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier C.M. Ahern K.V. Cheng M.L. Lee J.E. Yenari M.A. Steinberg G.K. Optimal depth and duration of mild hypothermia in a focal model of transient cerebral ischemia. Effects on neurologic outcome, infarct size, apoptosis, and inflammation. Stroke. 1998;29:2171–2180. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.10.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley G.T. Fujimura M. Ma T. Noshita N. Filiz F. Bollen A.W. Chan P. Verkman A.S. Aquaporin-4 deletion in mice reduces brain edema after acute water intoxication and ischemic stroke. Nat. Med. 2000;6:159–163. doi: 10.1038/72256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahama K.-I. Nagano M. Fujioka A. Shinoda K. Sasaki H. Effect of TPA on aquaporin 4 mRNA expression in cultured rat astrocytes. Glia. 1999;25:240–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S. Nagelhus E.A. Amiry-Moghaddam M. Bourque C. Agre P. Ottersen O.P. Specialized membrane domains for water transport in glial cells: high-resolution immunogold cytochemistry of aquaporin-4 in rat brain. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:171–180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00171.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nito C. Kamada H. Endo H. Niizuma K. Myer D.J. Chan P.H. Role of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/cytosolic phospholipase A(2) signaling pathway in blood-brain barrier disruption after focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1686–1696. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki K. Nishimura M. Hashimoto N. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and cerebral ischemia. Mol. Neurobiol. 2001;23:1–19. doi: 10.1385/MN:23:1:01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno S. Saito A. Hayashi T. Chan P.H. The c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase signaling pathway mediates Bax activation and subsequent neuronal apoptosis through interaction with Bim after transient focal cerebral ischemia. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:7879–7887. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1745-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos M.C. Verkman A.S. Aquaporin-4 gene disruption in mice reduces brain swelling and mortality in pneumococcal meningitis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13906–13912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao C.S. Che Y. Han P.L. Lee J.K. Delayed and differential induction of p38 MAPK isoforms in microglia and astrocytes in the brain after transient global ischemia. Mol. Brain Res. 2002;107:137–144. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00456-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao C.S. Kim J.B. Han P.L. Lee J.K. Administration of the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 affords brain protection with a wide therapeutic window against focal ischemic insult. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003;73:537–544. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao K.V.R. Jayakumar A.R. Reddy P.V.B. Tong X. Curtis K.M. Norenberg M.D. Aquaporin-4 in manganese-treated cultured astrocytes. Glia. 2010;58:1490–1499. doi: 10.1002/glia.21023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Hillaire C. Vargas D. Pardo C.A. Gincel D. Mann J. Rothstein J.D. McArthur J.C. Conant K. Aquaporin 4 is increased in association with human immunodeficiency virus dementia: implications for disease pathogenesis. J. Neurovirol. 2005;11:535–543. doi: 10.1080/13550280500385203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugino T. Nozaki K. Takagi Y. Hattori I. Hashimoto N. Moriguchi T. Nishida E. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases after transient forebrain ischemia in gerbil hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:4506–4514. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04506.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait M.J. Saadoun S. Bell B.A. Papadopoulos M.C. Water movements in the brain: role of aquaporins. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait M.J. Saadoun S. Bell B.A. Verkman A.S. Papadopoulos M.C. Increased brain edema in AQP4-null mice in an experimental model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neuroscience. 2010;167:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umenishi F. Schrier R.W. Hypertonicity-induced aquaporin-1 (AQP1) expression is mediated by the activation of MAPK pathways and hypertonicity-responsive element in the AQP1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15765–15770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209980200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkman A.S. More than just water channels: unexpected cellular roles of aquaporins. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:3225–3232. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N. Sobue K. Miyachi T. Inagaki M. Miura Y. Katsuya H. Asai K. Differential regulation of aquaporin expression in astrocytes by protein kinase C. Mol. Brain Res. 2001;95:110–116. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]