Abstract

Mechanistic investigation of gold(I)-catalyzed intramolecular allene hydroalkoxylation established a mechanism involving rapid and reversible C–O bond formation followed by turnover-limiting protodeauration from a mono(gold) vinyl complex. This on-cycle pathway competes with catalyst aggregation and formation of an off-cycle bis(gold) vinyl complex.

Over the past decade, the applications of soluble gold(I) complexes as catalysts for organic transformations, in particular the electrophilic activation of C–C multiple bonds, have increased dramatically.1 In contrast to the extensive development of the synthetic aspects of gold(I) π-activation catalysis, the mechanisms of these transformations remain poorly defined and are derived largely from computational analyses.2 However, experimental evidence pertaining to the mechanisms of gold(I) π-activation catalysis, notably the in situ detection and/or independent synthesis of potential catalytic intermediates, has begun to emerge.3–5 Perhaps most intriguing among these potential intermediates are the bis(gold) vinyl complexes formed via the addition of nucleophiles to allenes or alkynes in the presence of gold(I).5,6 However, the extent to which formation of bis(gold) species represents a general phenomenon in gold π-activation catalysis remains unclear and lacking is information regarding the behavior of bis(gold) vinyl species vis-à-vis mono(gold) vinyl complexes4 under catalytic conditions.

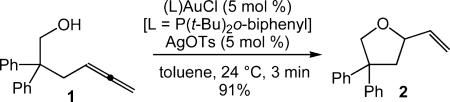

Herein, we report the mechanistic investigation of the gold(I)-catalyzed intramolecular hydroalkoxylation of 2,2-diphenyl-4,5-hexadien-1-ol (1) to form 2-vinyltetrahydrofuran 2 (eq 1),7 which represents the first mechanistic analysis of

|

eq 1 |

gold-catalyzed hydroalkoxylation. Importantly, this investigation delineates the catalytic behavior and interplay of the mono(gold) and bis(gold) vinyl complexes generated under catalytic conditions and establishes the reversibility of C–O bond formation.8–10

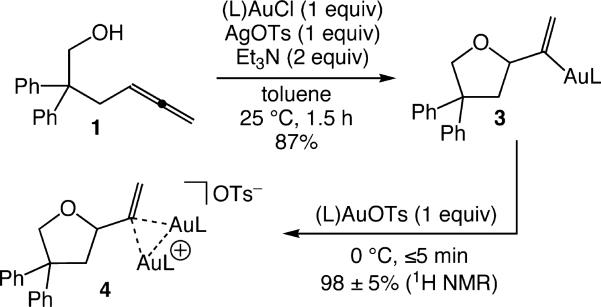

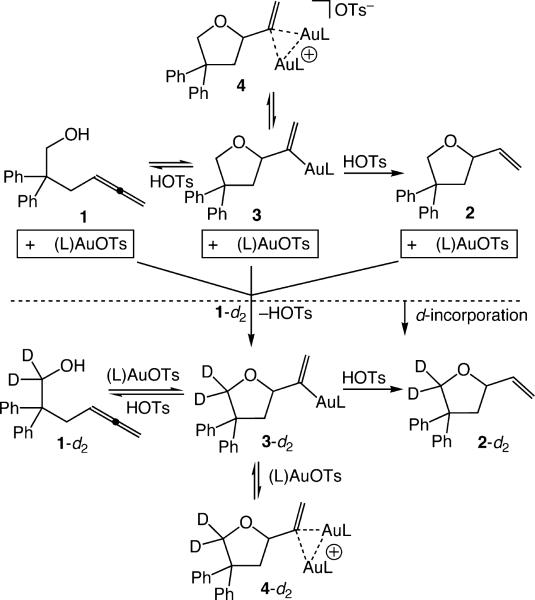

In an effort to intercept gold vinyl intermediates in the gold(I)-catalyzed conversion of 1 to 2, a toluene suspension of 1, (L)AuCl [L = P(t-Bu)2o-biphenyl], AgOTs, and Et3N (1:1:1:2) was stirred at room temperature for 1.5 h (Scheme 1).11 Aqueous workup and crystallization from warm hexanes gave mono(gold) vinyl complex 3 in 87% yield as an air- and thermally stable white solid that was fully characterized by spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography (Figure 1). Treatment of 3 (31 mM) with (L)AuOTs (1 equiv) in CD2Cl2 at 0 °C led to immediate (≤5 min) formation of the bis(gold) vinyl complex 4 in 98 ± 5% yield by 1H NMR (Scheme 1). Complex 4 persisted indefinitely in solution at this temperature but decomposed when concentrated and was therefore characterized in solution. Notably, the 31P NMR spectrum of 4 displayed a 1:1 ratio of resonances at δ 61.7 and 60.9, which established the presence of chemically inequivalent (L)Au fragments, while the large difference in the 1H NMR shifts of the vinylic protons of 4 [δ 4.84 and 3.90] relative to those of 3 [δ 5.48 and 4.45] established interaction of the vinyl moiety of 4 with both (L)Au+ fragments.

Scheme 1.

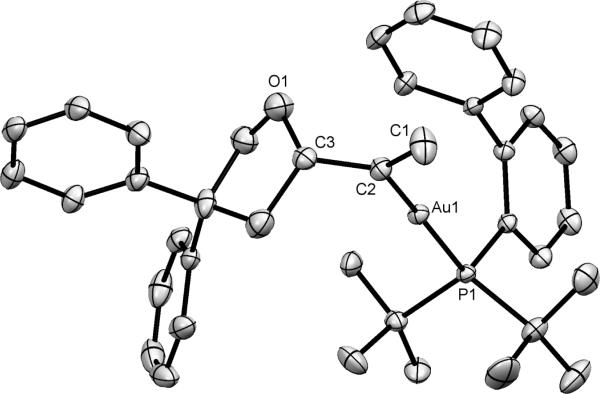

Figure 1.

ORTEP diagram of 3. Ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability and hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg): Au1−C2 = 2.048(7), Au1−P1 = 2.3163(16), C1−C2 = 1.333(11), C2−C3 = 1.518(10), C2−Au1−P1 = 174.3(2), C1−C2−Au1 = 120.5(6), C3−C2−Au1 = 122.4(5), C1−C2−C3 = 117.0(7).

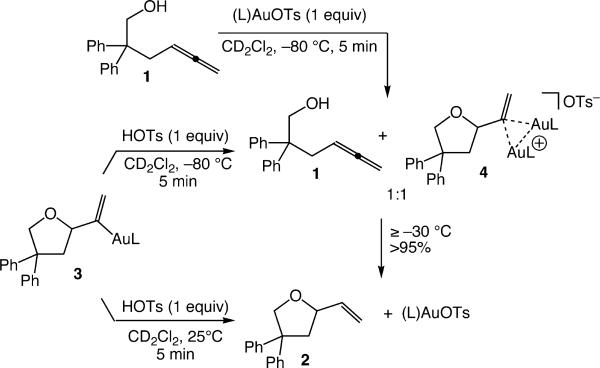

To evaluate the relevance of vinyl gold complexes 3 and 4 in the gold-catalyzed conversion of 1 to 2, we investigated the reaction of 1 with (L)AuOTs under stoichiometric and catalytic conditions. Reaction of a equimolar solution of 1 (55 mM) and (L)AuOTs in CD2Cl2 at −80 °C led to immediate (≤10 min) formation of a 1:1 mixture of 1 and 4 without generation of detectable quantities of 3 or 2, which established the facility of both C–O bond formation and aggregation relative to protodeauration (Scheme 2). Warming this solution to −30 °C for 3 h led to formation of 2 in 94 ± 5% yield (1H NMR) with concomitant regeneration of (L)AuOTs. When a solution of 1 (120 mM) and a catalytic amount of (L)AuOTs (5 mol %) in CD2Cl2 at −30 °C was monitored periodically by 31P NMR spectroscopy, resonances corresponding to 4 appeared immediately, persisted throughout ~95% conversion as the only detectable organometallic species, and then disappeared with regeneration of (L)AuOTs (δ 53.5). Kinetic analysis of the gold-catalyzed conversion of 1 to 2 under similar conditions revealed a deuterium KIE of kH/kD = 5.3 upon substitution of 1 with 1-O-d (94% d).12

Scheme 2.

We likewise investigated the protonolysis behavior of vinyl gold complexes 3 and 4. Treatment of mono(gold) vinyl species 3 with TsOH (2 equiv) at 25 °C led to immediate (≤10 min) formation of tetrahydrofuran 2 in 99 ± 5% yield (1H NMR; Scheme 2).12 However, 1H NMR analysis of the reaction of 3 with TsOH (1.3 equiv) at −80 °C revealed immediate (≤5 min) retrocyclization/aggregation to form a ~1:1 mixture of 1 and 4 in >90% combined yield, along with traces (~8%) of 2 (Scheme 2). Warming this solution at 0 °C for 20 min led to complete (97 ± 5% yield by 1H NMR) conversion to 2 and (L)AuOTs (Scheme 2). Independent kinetic analysis of the reaction of 4 (40 mM) with HOTs at 5 °C in CD2Cl2 revealed ~zeroth-order dependence on [HOTs] from 38 to 152 mM with no significant deuterium KIE (kH/kD = 0.9) for the reaction of 4 with DOTs (38 mM). Both observations point to a mechanism for the conversion of 4 to 2 involving rate-limiting disproportionation of 4 into 3 and (L)AuOTs followed by rapid protodeauration of 3; however, it must be noted that the concentrations of both 4 and HOTs in these experiments exceed those present under catalytic conditions by an order of magnitude.

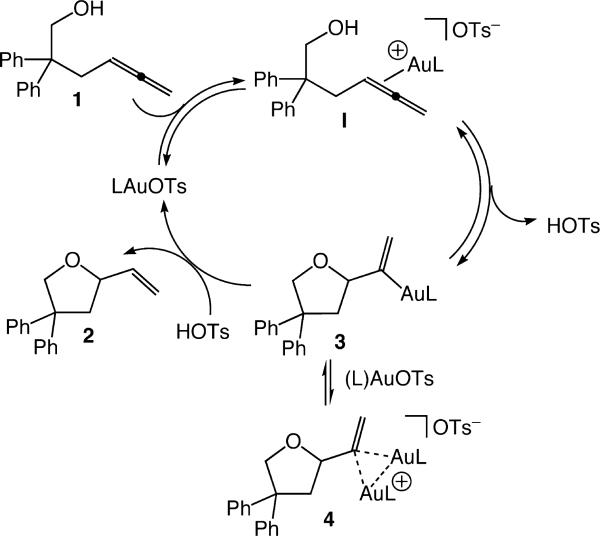

The experimental observations describe herein and elsewhere7,13 support a mechanism for the gold-catalyzed conversion of 1 to 2 involving rapid and reversible outer-sphere C–O bond formation7 from the unobserved gold π-allene complex I13 to form mono(gold) vinyl complex 3 with release of HOTs (Scheme 3). Complex 3 undergoes turnover-limiting protodeauration with HOTs to form 2 and (L)AuOTs or, alternatively, 3 is reversibly sequestered by (L)Au+ to form 4 in an off-cycle pathway. All available evidence, notably the large deuterium KIE of catalytic hydroalkoxylation, points to turnover-limiting protodeauration, while the kinetics and KIE of the stoichiometric reaction of 4 with HOTs argues strongly against the direct protonation of 4.

Scheme 3.

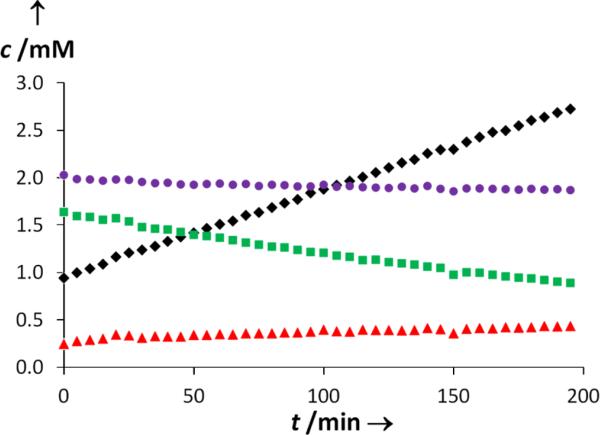

With a working mechanism in place, we sought to more fully delineate the interplay between mono(gold) and bis(gold) vinyl complexes during catalysis and to likewise evaluate the reversibility of C–O bond formation under catalytic conditions. To this end, we performed a deuterium-labeling experiment that allowed the evolution of bis(gold) vinyl complex 4 to be analyzed independently from on-cycle catalytic turnover. Specifically, an equimolar mixture of 4 and HOTs (1.4 mM) was generated in situ from reaction of 1 and (L)AuOTs (1:2) at −78 °C in CD2Cl2 (Scheme 4). This solution was treated with excess 1,1-dideuterio-2,2-diphenyl-4,5-hexadien-1-ol (1-d2; 29 mM) at −78 °C, warmed to −45 °C, and monitored periodically by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Scheme 4). Plots of [4], [4 + 4-d2], [2], and [2 + 2-d2] versus time early in the reaction (2–7% conversion)14 provided initial rate values for the consumption of 4 (k4 = (−3.8 ± 0.1) × 10−3 mM min−1) and 4 + 4-d2 (k4tot = (−0.61 ± 0.02) × 10−3 mM min−1) and for the appearance of 2 (k2 = (0.74 ± 0.04) × 10−3 mM min−1) and 2 + 2-d2 (k2tot = (9.1 ± 0.1) × 10−3 mM min−1) (Figure 2). These data reveal that the rate of total product formation [2-dx; x = 0,2] was ~2.5 times greater than was the rate at which 4 was consumed, which, in turn, was ~5 times greater than the rate of formation of 2 (Figure 2). Two important conclusions were drawn from these observations. First, ~70% of catalyst turnover bypasses the bis(gold) vinyl complex 4-dx, which solidifies assignment of 4 as an off-cycle catalyst reservoir. Second, ~80% of mono(gold) vinyl complex 3 generated via disproportionation of protio 4 undergoes cycloreversion and ligand exchange rather than protodeauration.15 Also worth noting was that over the same conversion range noted above (2–7%), the total concentration of bis(gold) vinyl isotopomers [4-dx, x = 0,2] decreased by ~8%, which presumably reflects the approach to the steady-state distribution of (L)Au+ between 4-dx and on-cycle mono(gold) complexes (Scheme 3).

Scheme 4.

Pathways for the Consumption of 4 (1.4 mM) in the Presence of 1-d2 (29 mM) in CD2CI2 at −45 °C

Figure 2.

Concentration versus time plot for the cyclization of 1-d2 (29 mM) catalyzed by in situ generated 4 (2 mM) in CD2Cl2 at −45 °C from ~2% to ~7% conversion: [2 + 2-d2] (black ◆); [2] (red ▲); [4 + 4-d2] (purple ●); [4] (green ■).

In summary, we have elucidated the mechanism of the gold(I)-catalyzed conversion of 1 to 2, which represents the first mechanistic analysis of gold-catalyzed hydroalkoxylation. The two key conclusions drawn from these studies are that (1) bis(gold) vinyl complex 4 is an off-cycle catalyst reservoir and (2) C–O bond formation is rapid and reversible under catalytic conditions. The presence of an off-cycle intermediate provides both a target for improving catalytic efficiencies and a rationale for the enhanced reactivity of sterically hindered phosphine and carbene supporting ligands (vis-à-vis PPh3) in many gold(I)-catalyzed reactions.1 Likewise, reversible C–O bond formation has important implications regarding stereochemical control in gold(I)-catalyzed enantioselective allene hydrofunctionalization.16 Specifically, the result suggests that extant mechanistic models invoking stereochemically determining C–Nuc bond formation may require re-evaluation in the context of stereochemically determining protodeauration of an equilibrating mixture of diastereomeric gold vinyl complexes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support is gratefully acknowledged from Duke University for a C. R. Hauser fellowship (T.J.B.), the Fulbright Foreign Student Program (D.W.), the National Institute of General Medicine (GM-60578), and the NSF (CHE-0555425).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Experimental procedures and kinetic, spectroscopic, and X-ray crystallographic data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Bandini M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1358. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00041h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Corma A, Leyva-Pérez A, Sabater MJ. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1657. doi: 10.1021/cr100414u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) de Mendoza P, Echavarren AM. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010;82:801. [Google Scholar]; (d) Fürstner A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3208. doi: 10.1039/b816696j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Rudolph M, Hashmi ASK. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:6536. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10780a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Krause N, Winter C. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1994. doi: 10.1021/cr1004088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Boorman TC, Larrosa I. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1910. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00098a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Pradal A, Toullec PY, Michelet V. Synthesis. 2011:1501. [Google Scholar]; (i) Sengupta S, Shi X. ChemCatChem. 2010;2:609. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Computational Mechanisms of Au and Pt Catalyzed Reactions. Soriano E, Marco-Contelles J, editors. Topics in Current Chemistry. Vol. 302. Springer; New York: 2011.

- (3).(a) Liu L-P, Hammond GB. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:3129. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15318a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schmidbaur H, Schier A. Organometallics. 2010;29:2. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hashmi ASK. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:5232. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Liu L-P, Xu B, Mashuta MS, Hammond GB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:17642. doi: 10.1021/ja806685j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hashmi ASK, Schuster AM, Gaillard S, Cavallo L, Poater A, Nolan SP. Organometallics. 2011;30:6328. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hashmi ASK, Ramamurthi TD, Rominger F. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:971. [Google Scholar]; (d) Chen Y, Wang D, Petersen JL, Akhmedov NG, Shi X. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:6147. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01338b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hashmi ASK, Schuster AM, Rominger F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:8247. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Weber D, Tarselli MA, Gagne MR. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:5733. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Weber D, Gagné MR. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4962. doi: 10.1021/ol902116b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Seidel G, Lehmann CW, Fürstner A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:8466. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Weber D, Jones TD, Adduci LL, Gagné MR. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:2452. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hashmi ASK, Braun I, Nösel P, Schädlich J, Wieteck M, Rudolph M, Rominger F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:4456. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Bis(gold) complexes were first proposed on the basis of DFT calculations: Cheong PH, Morganelli P, Luzung MR, Houk KN, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:4517. doi: 10.1021/ja711058f.

- (7).Zhang Z, Liu C, Kinder RE, Han X, Qian H, Widenhoefer RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9066. doi: 10.1021/ja062045r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Reversible C–Nuc bond formation has not previously been documented for gold-catalyzed allene hydrofunctionalization. Blum has documented the reversible cyclization of an allyl allenoate to form a gold σ-vinyl allyl oxonium complex,9 while Toste has provided evidence for the reversible conversion of a γ-alkenyl urea to a σ-alkyl gold complex.10

- (9).(a) Shi Y, Roth KE, Ramgren SD, Blum SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:18022. doi: 10.1021/ja9068497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Roth KE, Blum SA. Organometallics. 2010;29:1712. [Google Scholar]

- (10).LaLonde RL, Brenzovich JWE, Benitez D, Tkatchouk E, Kelley K, Goddard WA, Toste FD. Chem. Sci. 2010;1:226. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00255K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Cyclization of /1 catalyzed by either (L)AuOTs (5 mol %) in dichloromethane or by a mixture of (L)AuCl/AgOTs in toluene formed 2 in >90% yield within 5 min at room temperature.

- (12).Both the cyclization of 1-O-d (≥90% d) catalyzed by (L)AuOTs and the stoichiometric reaction of 4 with DOTs (≥90% d) formed 4,4-diphenyl-2-vinyl(1-deuterio)tetrahydrofuran (2-d1) with 85 and 79% deuterium incorporation, respectively.

- (13).Brown TJ, Sugie A, Dickens MG, Widenhoefer RA. Organometallics. 2010;29:4207. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Conversion defined by total product formation (2 + 2-d2).

- (15).Because cycloreversion without ligand exchange (3 → I) would not lead to dispersion of 1 into the reactant pool, the relative rates of cycloreversion and protodeauration from 3 may be significantly greater than the ~4:1 ratio determined from this experiment.

- (16).(a) Li H, Lee SD, Widenhoefer RA. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011;696:316. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) LaLonde RL, Wang ZJ, Mba M, Lackner AD, Toste FD. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:598. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhang Z, Bender CF, Widenhoefer RA. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2887. doi: 10.1021/ol071108n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhang Z, Bender CF, Widenhoefer RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14148. doi: 10.1021/ja0760731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) LaLonde RL, Sherry BD, Kang EJ, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2452. doi: 10.1021/ja068819l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Hamilton GL, Kang EJ, Mba M, Toste FD. Science. 2007;317:496. doi: 10.1126/science.1145229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Zhang Z, Widenhoefer RA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:283. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.