Summary

The effects of putative A3 adenosine receptor antagonists of three diverse chemical classes (the flavonoid MRS 1067, the 6-phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridines MRS 1097 and MRS 1191, and the triazoloquinazo-line MRS 1220) were characterized in receptor binding and functional assays. MRS1067, MRS 1191 and MRS 1220 were found to be competitive in saturation binding studies using the agonist radioligand [125I]AB-MECA (N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5'-N-methyluronamide) at cloned human brain A3 receptors expressed in HEK-293 cells. Antagonism was demonstrated in functional assays consisting of agonist-induced inhibition of adenylate cyclase and the stimulation of binding of [35S]guanosine 5'-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) ([35S]GTP-γ-S) to the associated G-proteins. MRS 1220 and MRS 1191, with KB values of 1.7 and 92 nM, respectively, proved to be highly selective for human A3 receptor vs human A1 receptor-mediated effects on adenylate cyclase. In addition, MRS 1220 reversed the effect of A3 agonist-elicited inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α formation in the human macrophage U-937 cell line, with an IC50 value of 0.3 μM. Published by Elsevier Science Ltd.

Keywords: Dihydropyridine, flavonoid, triazoloquinazoline, adenylate cyclase, tumor necrosis factor, guanine nucleotides, adenosine A3 receptor, adenosine

Adenosine agonists and antagonists selective for one of the subtypes of adenosine receptors (A1 through A3) have therapeutic potential for the treatment of diseases of the central nervous system (von Lubitz et al., 1996b; Jacobson et al., 1996a). Endogenous adenosine is thought to be critical to homeostasis of the brain, heart and other organs and to have a natural neuroprotective role. Manipulation of these adenosine receptors through the exogenous administration of receptor subtype selective agents can have a major impact on the outcome of cerebral ischemia and other neurodegenerative conditions. For example, the selective A1 agonist ADAC (MRS 998) was recently shown to provide protection against global ischemia in gerbils, even upon administration as late as 12 hr post-ischemia (von Lubitz et al., 1996a). The actions of A1 agonists, in general, may counteract excitotoxic glutaminergic stimulation at multiple stages, both pre- and postsynaptic, and the inverse relationship of activation of A1 vs NMDA receptors has been demonstrated (von Lubitz et al., 1995). Furthermore, using the A1 agonist ADAC there appears to be a dose window [≤ 0.1 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)] of selectivity, in which the cerebroprotection occurs without accompanying side-effects of hypotension, bradycairdia and hypothermia. These side-effects have previously been considered a drawback to the use of A1 agonists for acute treatment of stroke. Selective antagonists at either A1 or A2A receptors have been in clinical trials for the treatment of cognitive deficits (Schingnitz et al., 1991) or Parkinson's disease (Shimada et al., 1992), respectively. The first A3 receptor-selective agonist, developed in our laboratory (Kim et al., 1994), N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5'-N-methylcarbamoyladenosine (IB-MECA, MRS 465), was shown to be cerebroprotective in the gerbil global ischemia model following chronic, but not acute administration (von Lubitz et al., 1994). An 'effect reversal' depending on acute vs chronic administration has been noted for A1 receptors, i.e. the chronic administration of an agonist mimics the action of an acute antagonist selective for that subtype in stroke and seizure models (Jacobson et al., 1996a). Thus it has been proposed that antagonists selective for A3 receptors may also prove to be cerebroprotective, at least in the case of acute administration.

Until recently A3 receptor antagonists were unknown (Jacobson et al., 1995). We have introduced A3 receptor antagonists belonging to three distinct, non-purine chemical classes (Fig. 1). A broad screening of phytochemicals in competitive binding assays vs the high affinity agonist [I25I]AB-MECA (N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5'-N-methyluronamide) has demonstrated that certain naturally occurring flavonoids have micromolar affinity at cloned human brain A3-adenosine receptors (Ji et al., 1996). This finding has been subjected to chemical optimization leading to 3,6-dichloro-2'-isopropyloxy-4'-methyl-flavone (MRS 1067; Ki = 0.56 μM), which was both relatively potent and highly selective (200-fold) for human A3 vs human A1 receptors (Karton et al., 1996). This derivative effectively antagonized the effects of an agonist in a functional A3 receptor assay, that is, inhibition of adenylate cyclase in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells expressing cloned rat A3 receptors. The considerable affinity of flavones at adenosine receptors may explain some of the previously observed vascular and other biological effects of these compounds. Similarly 1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives, such as the known L-type Ca2+ channel antagonists niguldipine and nicardipine, demonstrated intermediate (micromolar) affinity at human A3 receptors (van Rhee et al., 1996). Chemical optimization of this class of antagonists has resulted in derivatives such as 3,5-diethyl 2-methyl-6-phenyl-4-[2-phenyl-(E)-vinyl]-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (MRS 1097), which is 200-fold selective in binding to human A3 (Ki = 0.51 μM) vs human A1 receptors and does not bind to Ca2+ channels. A later generation compound in the series of 6-phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridines (Jiang et al., 1996), 3-ethyl 5-benzyl 2-methyl-6-phenyl-4-phenylethynyl-1,4-(±)-dihydropyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (MRS 1191), is 1300-fold selective in binding to human A3 receptors (Ki = 31.4 nM) vs rat A1 receptors. Although the selectivity and affinity of MRS 1191 was much less at the rat A3 (28-fold selective vs rat A1 receptors; Jiang et al., 1997) than at the human A3 receptor, this agent nevertheless reversed the electrophysiological effects of A3 receptor agonists in rat hippocampal slices without affecting A1 receptors. Finally, 9-chloiro-2-(2-furyl)-5-phenylacetylamino[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazoline (MRS 1220), a derivative of the triazoloquinazoline antagonist CGS15943, was found to selectively displace radioligand from human A3 receptors with a Ki value of 0.65 nM (Kim et al., 1996). The N-phenylacetyl group of MRS 1220 is key to its selectivity (470-fold vs rat A1 and 80-fold vs rat A2A receptors) and extremely high potency at A3 receptors. With such a high affinity it would be worthwhile to prepare a radiolabeled antagonist for use in binding experiments. Other A3 receptor antagonists L-249313 (6-carboxymethyl-5,9-dihydro-9-methyl-2-phenyl-[1,2,4]-triazolo[5,1-a][2,7]naphthyr-idine) and L-268605 (3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-5-amino-7-oxo-thiazolo[3,2]pyrimidine) have been identified through broad screening by Jacobson et al. (1996b) at Merck. L-249313 was shown to be non-competitive in binding, while L-268605 is a competitive antagonist. Recently we have synthesized antagonists in the dihydropyridine class with A3 receptor selectivities of >37 000-fold (Jiang et al, 1997).

Fig. 1.

Structures of A3 receptor-selective antagonists of diverse chemical structures. Ki values (nM) for binding at A1/A2A/A3 receptors are shown, in rat unless noted by `h' (human).

Prior to other affinity studies and biophysical studies of the A3 receptor binding site, it is first necessary in the present study to demonstrate whether the binding of these three novel classes of ligands in the MRS series is competitive and whether they are full antagonists. The competitive nature of binding has been characterized using an appropriate range of concentrations of the putative antagonists vs saturation of agonist radioligand binding at cloned A3 receptors expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells. Antagonism is shown in functional assays consisting of both the inhibition of adenylate cyclase mediated by agonists acting at cloned human brain A3 receptors and the stimulation of binding of [35S]GTP-γ-S at the associated G-proteins (Lorenzen et al., 1996; Lazareno and Birdsall, 1993). In addition, the antagonists are examined in reversing the newly discovered effect of A3 agonist-elicited inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) formation in human macrophages (Sajjadi et al., 1996).

METHODS

Materials

A3 adenosine receptor agonists IB-MECA and Cl-IB-MECA (2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarba-moyladenosine, MRS 533) and the A3 adenosine receptor agonist R-PIA (N6-(phenylisopropyl)adenosine) were obtained from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA, USA). A3 antagonists were synthesized as described (van Rhee et al., 1996; Karton et al., 1996; Kim et al., 1996; Jiang et al., 1996). The dihydropyridine derivatives were stored either as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) stock solutions or as solids at −20°C to avoid decomposition. [125I]AB-MECA was obtained from Amersham (Chicago, IL, USA). Membranes of HEK-293 cells stably expressing human brain A3 receptors were purchased from Receptor Biology, Inc. (Baltimore, MD, USA). Alternately, human A3 receptors were stably transfected in CHO cells.

Radioligand binding assays

Radioligand binding assays for adenosine A3 receptors were performed in membranes prepared from HEK-293 cells stably expressing human brain A3 receptors (Salvatore et al., 1993) as described previously (Karton et al., 1996). Briefly, in 125 μl of 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0) containing 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA and 2 U/ml adenosine deaminase, saturation binding studies using [125I]AB-MECA (N6-(4-amino-3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide) were conducted in the presence or absence of adenosine A3 antagonist at room temperature for 60 min. The reaction was terminated by filtration using a cell harvester (Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) over GF/B filters followed by three washings with 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0) containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM EDTA. Nonspecific binding was defined by using 100 μM NECA, and the final concentration of [125I]AB-MECA ranged from 0.8 to 10 nM.

Binding of [35S]GTP-γ-s

The binding of [35S]GTP-γ-S was carried out using HEK-293 cells expressing human A3 receptors. Membranes were suspended in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 3 U/ml adenosine deaminase, 100 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4 at a protein concentration of 5–10 μg per tube. The membrane suspension was pre-incubated with 0.5 μM GDP, 10 μM. NECA or 1 μM Cl-IB-MECA and antagonist in a final volume of 450 μl buffer at 30°C for 20 min and then transferred to ice for 20 min. [35S]GTP-γ-S was added to a final concentration of 0.1 nM in a total volume of 500 μl and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 30°C. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM GTP-γ-S. Incubation of the reaction mixture was terminated by filtration over GF/B glass fibers using a Brandel cell harvester and washed with the same buffer.

Adenylate cyclase assay

Adenylate cyclase assays were performed with membranes prepared from CHO cells stably expressing either the human A1 receptor or human A3 receptor by the method of Salomon et al. (1974) as described previously (Olah et al., 1994) with the following modifications. 4-(3-Butoxy-4-methoxybenzyl)-2-imidazolidinone (Ro 20-1724, 20 μM, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) was employed to inhibit phosphodiesterases rather than papaverine, and the NaCl concentration in the assay was 25 mM. Membranes were pretreated with 2 U/ml adenosine deaminase, and the antagonists MRS 1220 (100 nM) or MRS 1191 (1 μM) at 30°C for 5 min prior to initiation of the adenylate cyclase assay. Adenosine agonists used were either R-PIA at A1 receptors or IB-MECA at A3 receptors. Adenylate cyclase was stimulated with forskolin (5 μM), which typically produced an ~9- to 12-fold increase of activity over basal levels. Concentration-response data for the inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity by IB-MECA (human A3 receptor) and R-PIA (human A1 receptor) were obtained. Maximal inhibition of adenylate cyclase by IB-MECA at the human A3 receptor and by R-PIA at the human A1 receptor correlated to ~60% and ~50% of total stimulation, respectively. IC50 values were calculated using InPlot (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

Differentiation of U937 cells and stimulation of TNF-α production

Human U937 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA) and cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The differentiation of U937 cells were induced by treating the cells (2.5 × 105 cells/0.5 ml/well) with phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (TPA, 20ng/ml, Cal-biochem, San Diego, CA, USA) in flat-bottomed 24-well microtiter plates for 48 hr (Haas et al., 1989; Sajjadi et al., 1996). The supernatant was removed, and the adherent cells were washed once with 1 ml of the above culture medium. The cells (0.5 ml/well) were subse-quently incubated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 0.1 μg/ ml, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in the presence or absence of adenosine A3 ligand(s) for 24 hr. Aliquots of the supernatant were then assayed by ELISA for (h)TNF-α with the human TNF-α kit from Amersham International pic (Buckinghamshire, UK).

RESULTS

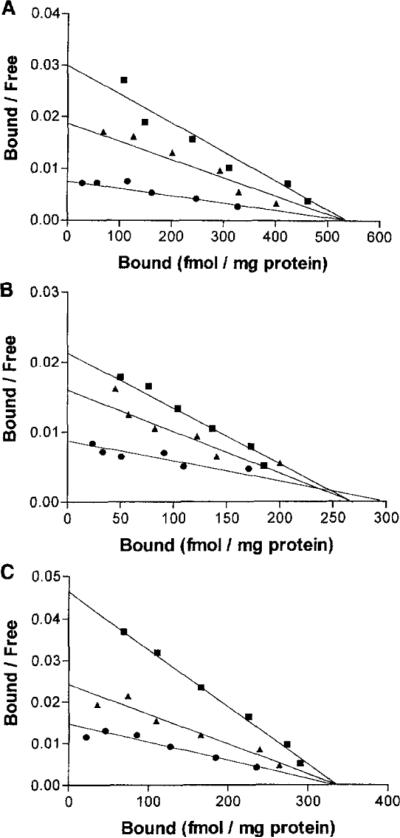

As reported previously, [125I]AB-MECA bound with high affinity to membranes prepared from HEK-293 cells expressing cloned human brain A3 receptors [clone HS-21a, Salvatore et al. (1993)]. The effects of adding fixed concentrations of the selective ligands MRS 1067, MRS 1191 and MRS 1220 during saturation experiments in these membranes with the agonist radioligand binding were examined (Table 1 and Fig. 2A–C). MRS 1067 (10 or 25 μM), MRS 1220 (1 or 3 nM), and MRS 1191 (200 or 500 nM) were clearly competitive in their interaction at the A3 receptor binding site, since no significant change in Bmax was observed. The apparent affinity (Kd) of [125I]AB-MECA decreased progressively with increasing concentrations of the agents. The order of potency of these three antagonists as competitive ligands at human A3 receptors as indicated in the Scatchard analysis was apparently: MRS 1220>MRS 1191>MRS 1067.

Table 1.

Effect of ligands to stimulate or inhibit [35S]GTP-γ-S binding to membranes of cells expressing the cloned hA3AR, compared with published receptor binding affinities and adenylate cyclase data

| Ligand | (h)A3 Receptor binding affinity | [3SS]GTP-γ-S binding | Inhibition of cAMP |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Ki (nM)* | EC50 or IC50 (nM)† | KB, Ka or IC50 (nM)‡ | |

| Agonists | |||

| NECA | 28 | 584 ± 107 | 130 |

| CI-IB-MECA | 1.17 | 46 ± 7 | 59.1 ± 9.1 |

| R-PIA | 53 | 1258 | 720 |

| Antagonists | |||

| MRS 1220 | 0.59 | 7.2 ± 4.6 | 1.7 |

| MRS 1191 | 31 | 554 ± 341 | 92 |

| MRS 1097 | 100 | 3360 ± 1455 | ND |

| MRS 1067 | 591 | 6400 ± 730 | ND |

Affinity data for NECA and R-PIA were from Salvatore et al. (1993). Affinity data for for other compounds were from Karton et al. (1996) (MRS 1067), van Rhee et al. (1996) (MRS 1097), Jiang et al. (1996) (MRS 1191) and Kim et al. (1996) (MRS 1220). Values determined in binding to membranes of transfected HEK 293 cells.

EC50 for stimulation of basal [35S]GTP-γ-S binding by agonists or IC50 for inhibition by antagonists in the presence of 10 μM NECA in membranes from transfected HEK 293 cells (± SEM).

Ka for NECA and R-PIA [transiected HEK 293 cells, Salvatore et al. (1993)] or IC50 for CI-IB-MECA (present study, transfected CHO cells, n = 3, ± SEM) or KB for antagonists (present study, transfected CHO cells). ND, not determined.

Fig. 2.

Scatchard plot for the binding of [125I]AB-MECA in the absence or presence of A3-adenosine receptor antagonists (A, MRS 1067; B, MRS 1220; C, MRS 1191) in membranes prepared from HEK-293 cells stably expressing human brain A3 receptors. Membranes were incubated with radioligand at room temperature for 1 hr, in the absence (squares) or presence of low (triangles) or high concentration (•) A3-receptor antagonists. The concentrations of A3-receptor antagonists used and the calculated binding parameters (apparent KD in nM, n = 3) are as follows: MRS 1067, 0 μM (3.21 ± 0.67), 10 μM (4.21 ± 1.81), 25 μM (8.03 ± 3.36); MRS 1220, 0 nM (2.26 ± 0.71) 1 nM (4.47 ± 0.86), 3 nM (15.5 ± 3.3); MRS 1191, OnM (2.48 ± 0.04), 200 nM (4.31 ± 0.79), 500 nM (7.82 ± 0.89).

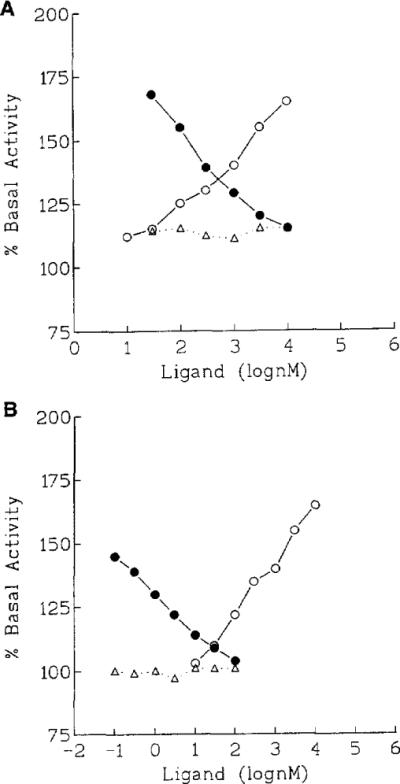

The agonist-induced stimulation of binding of [35S]GTP-γ-S to activated G proteins has been used as a functional assay for a variety of receptors, including adenosine receptors in particular (Lorenzen et al., 1996; Jacobson et al., 1996b). The effects of four A3 receptor-selective ligands MRS 1067, MRS 1097, MRS 1191 and MRS 1220 on agonist-induced stimulation of binding of [35S]GTP-γ-S from membranes of HEK-293 cells expressing the human A3 receptor clone were studied (Fig. 3). The non-selective adenosine agonist NECA caused a dose dependent increase in the level of the guanine nucleotide bound. The antagonists alone had no effect on the level of radioligand bound. However, each of the antagonists caused a concentration-dependent loss of binding of [35S]GTP-γ-S in the presence of a constant high concentration of NEC A (10 μM). EC50 values ranged from 7.2 nM for MRS1220 to 6.4 μM for MRS 1067 (Table 1). In each case the EC50 value was between 11-and 34-fold the Ki value obtained in a binding assay at human A3 receptors. Similar results were obtained using variable concentrations of the antagonists in the presence of a fixed concentration (1 μM) of the agonist Cl-IB-MECA (MRS 533).

Fig. 3.

Functional assay of the effects of antagonists (A, MRS 1191; B, MRS 1220) on the agonist-elicited activation of G protein. Binding of [35S]GTP-γ-S in membranes prepared from HEK-293 cells stably expressing human brain A3 receptors is stimulated by increasing concentrations of the non-selective agonist NEC A (◯). A3-adenosine receptor antagonists alone at the indicated concentration (triangles) had no effect. The stimulation by NEC A at a single concentration (10 μM) was antagonized in the presence of A3-adenosine receptor antago-nists (●) at the indicated concentration. Membranes were incubated with radioligand at 30°C for 30 min.

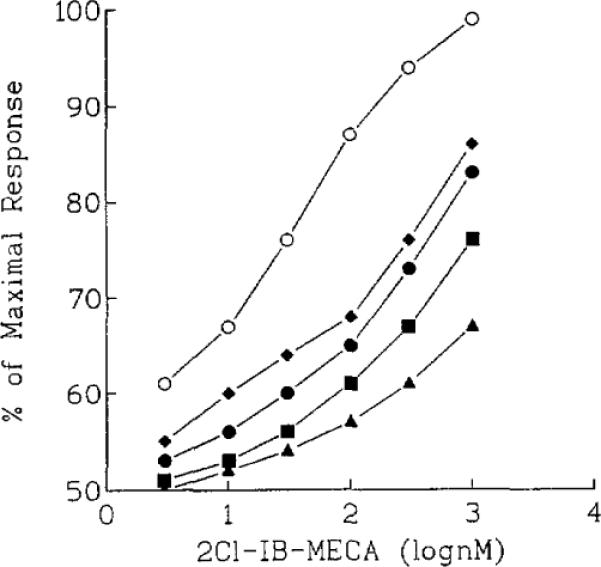

Another demonstration of the antagonism at A3 receptors was seen in Fig. 4. The highly selective agonist Cl-IB-MECA was very active in the [35S]GTP-γ-S assay with an EC50 of 46 ± 7 nM. Concentration-response curves for Cl-IB-MECA were depressed and right-shifted using fixed concentrations of the antagonists.

Fig. 4.

Concentration-response curves for stimulation of binding of [35S]GTP-γ-S by Cl-IB-MECA in membranes prepared from HEK-293 cells stably expressing human brain A3 receptors. Effects of the agonist alone (◯) or in the presence of A3-adenosine receptor antagonists (diamonds, 30 μM MRS 1067; ●, 10 μM MRS 1097; squares, 100 nM MRS 1220; triangles, 3 μM MRS 1191) are shown. Membranes were incubated with radioligand at 30°C for 30 min.

In a functional assay in CHO cells expressing the human A3 receptor [Fig. 5(A)], IB-MECA inhibited adenylate cyclase via human A3 receptors with an IC50 of 10.1 ± 4.9 nM (n = 3). In the presence of 1 μM MRS 1191, the concentration response curve was shifted to the right, with an IC5O of 120 ± 30 nM (n = 3). Similarly, in the presence of the more potent antagonist MRS 1220 at a concentration of 100 nM, the concentration response curve was shifted to the right, with an IC50 of 598 ± 129 nM (n = 3). The same degree of maximal inhibition of cyclase was observed in the presence of either antagonist as for agonist alone, suggesting competitive antagonism. From a Schild analysis (Alunlakshana and Schild, 1959) KB values obtained for antagonism by MRS 1191 and MRS 1220 are 92 and 1.7 nM, respectively, that is, in each case ca three times the Ki value obtained in binding to human A3 receptors. In a functional assay in CHO cells expressing the human A1 receptor [Fig. 5(B)], R-PIA inhibited adenylate cyclase with an IC5O of 1.77 ± 0.30 nM (n = 3). In the presence of A3 antagonists (MRS 1220 at 100 nM or MRS 1191 at 1 μM) the concentration response curves were only slightly right-shifted giving EC50 values of 11.0 ± 4.4 and 5.20 ± 0.9 nM, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of adenylate cyclase in membranes from CHO cell stably transfected with human A3 receptors (A) or human A1 receptors (B), by either IB-MECA orR-PIA, respectively. The assay was carried out as described in the presence of 5μM forskolin, 20 μM Ro 20–1724, and 25 mM NaCl. Each data point is shown as mean ± SEM for three determinations. Responses are shown for agonist alone (◯) or in combination with the A3 adenosine antagonists MRS 1191 (1 μM triangles) and MRS 1220 (100 nM, ●). IC5O values were 10.1 ± 4.9 (IB-MECA alone), 120 ± 30 nM (+MRS 1191), 598 ± 129 nM (+MRS 1191).

Cl-IB-MECA at relatively high concentrations was found to inhibit the release of TNF-α formation in the human macrophage U-937 cell line. The effect was concentration dependent with an IC5o of 3.6 μM [Fig. 6(A)], which was comparable to that reported previously (Sajjadi et al., 1996) for IB-MECA. The very potent antagonist MRS 1220 reversed the effect of A3 agonist-elicited inhibition of TNF-α formation in this cell line [Fig. 6(B)], with an IC5O of 0.3 μM. The antagonists MRS 1067 and MRS 1191 at submicromolar concentrations did not reverse the effect, consistent with their lower affinity at human A3 receptors. Higher concentrations of these antagonists were not examined due to the necessity of making stock solutions in DMSO and the extreme sensitivity of this assay to the presence of DMSO. A concentration of 0.05% DMSO was found to preclude the effect of LPS on TNF-α formation (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Effects on the A3 agonist-elicited inhibition of TNF-α formation in U-937 human macrophages. (A) A concentration response curve for Cl-IB-MECA indicated that the IC50 was ca 3.6 μM. The secretion of (h)TNF-α in the presence of LPS alone was 5182 ± 216 pg/ml. (B) Effects of combinations of antagonists and 5 μM Cl-IB-MECA on secretion of (h)TNF-α. The secretion of (h)TNF-α in the presence of LPS alone was 6523 ± 92 pg/ml. Key: squares, MRS 1220; triangles, MRS 1191; and inverted triangles, MRS 1067.

DISCUSSION

The activation of A3 receptors has been associated with paradoxical effects, both protective and damage-inducing. In an in vivo stroke model in gerbils (von Lubitz et al., 1994), a moderate dose of 0.1 mg/kg i.p. of the A3 selective agonist IB-MECA decreased survival and increased hippocampal cell damage. Also high concentrations of A3 selective agonists induced apoptosis and/or cell necrosis in human leukemia HL-60 cells, in human eosinophils, in astroglial cells and in cardiomyocytes (Kohno et al., 1996a, 1996b; Ceruti et al., 1996; Shneyvais et al., 1997). Lower concentrations of the agonists (~ 100 nM) protected against apoptosis in rat astroglial cell cultures (Ceruti et al., 1996). Curiously, moderately low concentrations of the antagonists MRS 1191, L249313 and MRS 1220 alone in various tumor cell lines induce the expression of bak protein, associated with the induction of apoptosis, and low doses of Cl-IB-MECA protect in this paradigm (Yao et al., 1997). There are also multiple second messenger systems associated with the A3 receptor subtype: activation of phospholipase C and D (Ali et al., 1996) and inhibition of adenylate cyclase (Zhou et al., 1992). The effects in both of these second messenger pathways are mediated by G proteins. Thus, selective antagonists are critically needed for the elucidation of these various effects mediated by the A3 receptor and to define the circumstances in which activation of this subtype by endogenous adenosine has a physiological role. A3 antagonists are postulated to be anti-inflammatory (Beaven et al., 1994) or cerebroprotective agents (von Lubitz et al., 1994).

In the present study we have shown that MRS 1067, MRS 1097, MRS 1191 and MRS 1220 are antagonists of the agonist-induced stimulation of binding of [35S]GTP-γ-S, which detects a composite response rather than a single second messenger pathway (Lorenzen et al., 1996). The two more potent antagonists (MRS 1191 and MRS 1220) were found to antagonize the inhibitory effects of an A3 selective agonist on the adenylate cyclase pathway. These agents were highly selective in antagonizing the inhibitory effects on adenylate cyclase by human A3 receptors vs human A1 receptors. The potencies for the antagonists in antagonizing the agonist-induced inhibition of adenylate cyclase were comparable to the corresponding affinities measured in the binding experiment (Table 1). In contrast, those involved in inhibiting the stimulation of binding of [35S]GTP-γ-S were somewhat decreased. Furthermore, MRS 1067, MRS 1191 and MRS 1220 were demonstrated to be competitive in saturation binding studies. The potencies of both IB-MECA (Sajjadi et al., 1996) and Cl-IB-MECA (this study, Fig. 6) in inhibiting the release of TNF-α in a human macrophage cell line were > 1000-fold less than the corresponding Ki values in binding at human A3 receptors. Also, the selective A3 receptor antagonists were less potent than anticipated in antagonizing the inhibition of TNF-α secretion, based on potencies in the two other functional assays. Among antagonists used in this assay, only the most potent, MRS 1220, completely reversed the effect of Cl-IB-MECA, and this occurred at relatively high concentrations. The comparatively low potencies of both A3 receptor agonists and antagonists in the TNF-α assay are unexplained.

Another unusual aspect of A3 receptor pharmacology is the striking species differences in antagonist affinity. In general, most antagonists yet studied, both xanthines and non-xanthines, are considerably more potent at the human clone than in the rat. For example, the A3 receptor binding affinities for the xanthine amine congener (XAC) differ by 410-fold in the two species (Salvatore et al., 1993; Jacobson et al., 1995). For the antagonists utilized in the present study, the following ratios of affinity at A3 receptors (human/rat): MRS 1067 (9.8-fold); MRS 1097 (39-fold); MRS 1191 (112-fold); and MRS 1220 (>2000-fold) were measured in previous studies (Karton et al., 1996; Jiang et al., 1996; Kim et al., 1996). The species difference at A3 receptors, which is more pronounced than for typical species homologues of other G protein-coupled receptors has even raised the hypothesis that these are indeed separate receptor subtypes. However, attempts to clone additional A3 receptor-like subtypes from either rat or human have not yet succeeded. Selective antagonists promise to be useful to further characterize the species differences. Antagonists that are A3 receptor-selective across species or in rat tissue alone are also needed as pharmacological tools to define the role of these receptors and also to establish if there exist multiple A3 receptors. For human A3 receptors, the most potent of these antagonists is MRS 1220, although MRS 1191 is the most selective. For use in rat, MRS 1191 would be preferred since it is still selective for A3 receptors (28-fold in binding), and its selectivity was already shown in the rat hippocampus (Dunwiddie et al., 1997).

The inhibition of release of the proinflammatory cytokine TFN-α by A3 agonists has been demonstrated using IB-MECA (Sajjadi et al., 1996) and in this study using Cl-IB-MECA. This supports the conclusions of Sajjadi et al. that the effect is mediated by A3 rather than A2B receptors, since Cl-IB-MECA is inactive at human A2B receptors at concentration of 100 μM (A. IJzerman, unpublished data). High levels of this cytokine are associated with various neurodegenerative diseases and have been implicated mechanistically in their progression, for example, in models of autoimmune diseases such as encephalomyelitis (Sun et al., 1996) and demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis and Guillain-Barré syndrome (Redford et al., 1995). TFN-α was shown to have a cytotoxic effect on glial cells (Sun et al., 1996). TFN-α has also been postulated to play a role in the pathogenesis of immunologically mediated fatigue (Sheng et al., 1996), the effects of viral infection of the brain (Tan et al., 1996), and Creutzfeld-Jakob disease (Kordek et al., 1996). TFN-α expression is a mediator of the intrinsic inflammatory reaction of the brain after ischemia (Buttini et al., 1996), suggesting that the protective effects of chronically administered IB-MECA (von Lubitz et al., 1994) may be related to modulation of the level of this cytokine. TFN-α also was found to induce the formation in astrocytes of nitric oxide (Rossi and Bianchini, 1996), which is deleterious during ischemia. This induction was a synergistic effect of both TFN-α and β-amyloid protein, suggesting a role in neuronal damage in Alzheimer's disease. Conversely, the presence of TFN-α has been shown to be protective against parasitic infection of the brain (Daubener et al., 1996) and against tumor growth. All of the above observations suggest that A3 agonists and/or antagonists, by virtue of effects on cytokines such as TFN-α and on apoptosis, may be useful in treating pathology of the central nervous system.

In the present study, we have demonstrated that representative compounds of the flavonoid, the 1,4-dihydropyridine, and the triazoloquinazoline classes are indeed potent, competitive antagonists at human A3 receptors. In the triazoloquinazoline classes, subnano-molar affinity has already been achieved with MRS 1220, thus this compound appears to be suitable for radiolabeling. Although the affinity is not as great, the selectivity of the 1,4-dihydropyridine MRS 1191 and later generation analogues in this class (Jiang et al., 1997) also suggests their utility as pharmacological probes. In conclusion, these novel antagonists promise to be very useful in pharmacological studies and as prototypical leads for the development of even more potent and subtype-selective A3 antagonists.

REFERENCES

- Ali H, Choi OH, Fraundorfer PF, Yamada K, Gonzaga HMS, Beaven MA. Sustained activation of phospholipase-D via adenosine A3 receptors is associated with enhancement of antigen-ionophore-induced and Ca2+-ionophore-induced secretion in a rat mast-cell line. Journal of Pharmacological Experimental Therapy. 1996;276:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alunlakshana O, Schild HO. British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. 1959;14:48. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1959.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaven MA, Ramkumar V, Ali H. Adenosine-A3 receptors in mast-cells. Trends in Pharmacological Science. 1994;15:13–14. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttini M, Appel K, Sauter A, Gebicke-Haerter PJ, Boddeke HW. Expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha after focal cerebral ischaemia in the rat. Neuroscience. 1996;71:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00414-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceruti S, Barbieri D, Franceschi C, Giammarioli AM, Rainaldi G, Malorni W, Kim HO, von Lubitz DKJE, Jacobson KA, Cattabeni F, Abbracchio MP. Dual actions of adenosine A3 receptor agonists on mammalian astrocytes: protection at low concentrations and apoptosis at high concentrations. Drug Development Research. 1996;37:77. [Google Scholar]

- Daubener W, Remscheid C, Nockemann S, Pilz K, Seghrouchni S, Mackenzie C, Hadding U. Anti-parasitic effector mechanisms in human brain tumor cells: role of interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. European Journal of Immunology. 1996;26:487–492. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Diao L, Kim HO, Jiang J-L, Jacobson KA. Activation of hippocampal adenosine A3 receptors produces a heterologous desensitization of A1 receptor mediated responses in rat hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:607–614. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00607.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas R, Bartels H, Topley N, Hadam M, Kohler L, Goppelt-Strube M, Resch K. TPA-induced differentiation and adhesion of U937 cells: changes in ultrastructure, cytoskeletal organization and expression of cell surface antigens. European Journal of Cellular Biology. 1989;48:282–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Kim HO, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles G, von Lubitz DKJE. A3 adenosine receptors: design of selective ligands and therapeutic prospects. Drugs of the Future. 1995;20:689–699. doi: 10.1358/dof.1995.020.07.531583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson MA, Chakravarty PK, Johnson RG, Norton R. Novel selective non-xanthine selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. Drug Development Research. 1996b;37:131. [Google Scholar]

- Ji X-D, Melman N, Jacobson KA. Interactions of flavonoids and other phytochemicals with adenosine receptors. Journal of Medical Chemistry. 1996;39:781–788. doi: 10.1021/jm950661k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J-L, van Rhee AM, Melman N, Ji X-D, Jacobson KA. 6-Phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridine derivatives as potent and selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. Journal of Medical Chemistry. 1996;39:4667–4675. doi: 10.1021/jm960457c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J-L, van Rhee AM, Chang L, Patchornik A, Evans P, Melman N, Jacobson KA. Structure activity relationships of 4-phenylethynyl-6-phenyl-1,4-dihydropyridines as highly selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. Journal of Medical Chemistry. 1997;40:2596–2608. doi: 10.1021/jm970091j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karton Y, Jiang J-L, Ji X-D, Melman N, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. Synthesis and biological-activities of flavonoid derivatives as as adenosine receptor antagonists. Journal of Medical Chemistry. 1996;39:2293–2301. doi: 10.1021/jm950923i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HO, Ji X-D, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. 2-Substitution of N6-benzyladeno-sine-5'-uronamides enhances selectivity for A3-adenosine receptors. Journal of Medical Chemistry. 1994;37:3614–3621. doi: 10.1021/jm00047a018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y-C, Ji X-D, Jacobson KA. Derivatives of the triazoloquinazoline adenosine antagonist (CGS15943) are selective for the human A3 receptor subtype. Journal of Medical Chemistry. 1996;39:4142–4148. doi: 10.1021/jm960482i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno Y, Sei Y, Koshiba M, Kim HO, Jacobson KA. Induction of apoptosis in HL-60 human promyelocytic leukemia cells by selective adenosine A3 receptor agonists. Biochemistry and Biophysics Research Communication. 1996a;219:904–910. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno Y, Ji X-D, Mawhorter SD, Bochner B, Sei Y, Koshiba M, Jacobson KA. Activation of adenosine A3 receptor on human eosinophils raises intracellular Ca2+ and induces apoptosis. Drug Development Research. 1996b;37:182. [Google Scholar]

- Kordek R, Nerurkar VR, Liberski PP, Isaacson S, Yanagihara R, Gajdusek DC. Heightened expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 1 alpha, and glial fibrillary acidic protein in experimental Creutz-feldt-Jakob disease in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the U.S.A. 1996;93:9754–9758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazareno S, Birdsall N. Pharmacological characterization of acetylcholine-stimulated [35S]-GTP-γ-S binding mediated by human muscarinic m1–m4 receptors: antagonist studies. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1993;109:1220–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen A, Guerra L, Vogt H, Schwabe U. Interaction of full and partial agonists of the A1 adenosine receptor with receptor/G protein complexes in rats-brain membranes. Molecular Pharmacology. 1996;49:915–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olah ME, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. 125I-4-Aminobenzyl-5'-N-methylcarboxamidoade-nosine, a high affinity radioligand for the rat A3 adenosine receptor. Molecular Pharmacology. 1994;45:978–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redford EJ, Hall SM, Smith KJ. Vascular changes and demyelination induced by the intraneural injection of tumour necrosis factor. Brain. 1995;118:869–878. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.4.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi F, Bianchini E. Synergistic induction of nitric oxide by beta-amyloid and cytokines in astrocytes. Biochemistry and Biophysics Research Communication. 1996;225:474–478. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajjadi FG, Takabayashi K, Foster AC, Domingo RC, Firestein GS. Inhibition of TNF-α expression by adenosine: role of A3 adenosine receptors. Journal of Immunology. 1996;156:3435–3442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon Y, Londos C, Rodbell M. A highly sensitive adenylate cyclase assay. Analytical Biochemistry. 1974;58:541–548. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore CA, Jacobson MA, Taylor HE, Linden J, Johnson RG. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human A3 adenosine receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the U.S.A. 1993;90:10365–10369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schingnitz G, Küfner-Mühl U, Ensinger H, Lehr E, Kuhn FJ. Selective A1-antagonists for treatment of cognitive deficits. Nucleosides and Nucleotides. 1991;10:1067–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng WS, Hu S, Lamkin A, Peterson PK, Chao CC. Susceptibility to immunologically mediated fatigue in C57BL/6 versus Balb/c mice. Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology. 1996;81:161–167. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada J, Suzuki F, Nonaka H, Ishii A, Ichikawa S. (E)-1,3-Dialkyl-7-methyl-8-(3,4,5-trimethoxystyryl)-xanthines-potent and selective adenosine-A2 antagonists. Journal of Medical Chemistry. 1992;35:2342–2345. doi: 10.1021/jm00090a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shneyvais V, Jacobson KA, Shainberg A. Induction of apoptosis in cultured cardiac myocytes by adenosine A3 receptor agonist. Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology. 1997 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Hu X, Shah R, Zhang L, Coleclough C. Production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha as a result of glia-T-cell interaction correlates with the pathogenic activity of myelin basic protein-reactive T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1996;45:400–409. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960815)45:4<400::AID-JNR9>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan SV, Guiloff RJ, Henderson DC, Gazzard BG, Miller R. AIDS-associated vacuolar myelopathy and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) Journal of Neurological Science. 1996;138:134–144. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(95)00354-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rhee AM, Jiang J-L, Melman N, Olah ME, Stiles GL, Jacobson KA. Interaction of 1,4-dihydropyr-idine and pyridine-derivatives with adenosine receptors— selectivity for A3 receptors. Journal of Medical Chemistry. 1996;39:2980–2989. doi: 10.1021/jm9600205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lubitz DKJE, Lin RCS, Popik P, Carter MF, Jacobson KA. Adenosine A3 receptor stimulation and cerebral ischemia. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1994;263:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90523-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lubitz DKJE, Kim J, Beenhakker M, Carter M, Lin R-C, Meshulam Y, Daly JW, Shi D, Zhou L-M, Jacobson KA. Chronic stimulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in mice: interactions with adenosine A1 receptors and protection against NMDA-induced seizures. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1995;283:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00338-l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lubitz DKJE, Lin R-C, Paul IA, Beenhakker M, Boyd M, Bischofberger N, Jacobson KA. Postischemic administration of adenosine amine congener (ADAC): analysis of recovery in gerbils. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1996a;316:171–179. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00667-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lubitz DKJE, Lin RCS, Sei Y, Boyd M, Abbracchio M, Bischofberger N, Jacobson KA. Adenosine receptors and ischemic brain injury: a hope or a disaster? Drug Development Research. 1996b;37:140. [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Sei Y, Abbracchio MP, Kim Y-C, Jacobson KA. Adenosine A3 receptor agonists protect HL-60 and U-937 cells from apoptosis induced by A3 antagonists. Biochemistry and Biophysics Research Communication. 1997;232:317–322. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou QY, Li CY, Olah ME, Johnson RA, Stiles GL, Civelli O. The A3 adenosine receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the U.S.A. 1992;89:7432–7436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]