Abstract

Background

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may be associated with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), a disorder most commonly occurring in young obese women. Because polysomnography, the standard test for diagnosing OSA, is expensive and time-consuming, questionnaires have been developed to identify persons with OSA. The Berlin questionnaire (BQ) reliably identifies middle-aged and older persons in the community who are at high-risk for OSA. We aimed to validate the BQ as a screening tool for OSA in IIH patients.

Methods

Patients with newly diagnosed IIH completed the BQ and then underwent diagnostic polysomnography. The BQ was scored as high- or low-risk for OSA, and the diagnosis of OSA was based on polysomnography findings. OSA was defined as an apnea-hypopnea index of ≥5 on polysomnography.

Results

Thirty patients were evaluated [24 women; 15 white, 15 black; age 16–54 years (median 32 years) and BMI 27.3–51.7 kg/m2 (median 39.8 kg/m2)]. Twenty patients (66.7%) had a high-risk BQ score and eighteen (60%) exhibited OSA. Fifteen of 20 (75%) with a high-risk BQ score had OSA, while 3 of 10 (30%) with a low-risk score had OSA (Fisher test, p=0.045). The sensitivity and specificity of the BQ for OSA in IIH patients were 83% and 58%, respectively, whereas the positive predictive value was 75%.

Conclusions

A low-risk BQ score identifies IIH patients who are unlikely to have OSA. Polysomnography should be considered in those with a high-risk score.

Keywords: Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension, Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Berlin Questionnaire

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common condition in which there are intermittent partial (viz., hypopneas) and complete (viz., apnea) limitations in airflow, with associated hypoxia and sympathetic arousals, during sleep.[1,2] It is associated with obesity and older age, is more common in men, and, when left untreated, results in increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.[1–3] Polysomnography is the gold standard test for OSA diagnosis, but requires overnight evaluation.[4] The Berlin questionnaire (BQ), which includes questions about snoring, daytime somnolence, body mass index (BMI), and hypertension, is a brief and validated screening tool that identifies persons in the community who are at high risk for OSA.[5]

OSA is thought be associated with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH).[6] Although the BQ has been used as a screening tool for OSA in prior IIH studies [7], validation studies of the BQ have only been performed in middle-aged and older adults living in the community, whereas IIH most often occurs in young, obese women.[5] Because visual outcomes may be worse in IIH patients who have OSA,[3,11] we obtained diagnostic polysomnography as part of routine clinical practice on newly-diagnosed IIH patients. We concurrently administered the BQ, to evaluate the validity of the BQ as a screening tool for OSA in IIH patients.

Methods

Standard Protocol Approvals and Patient Consents

The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (IRB). As data were collected retrospectively, patients were not required to give written informed consent.

Patients

Since March 2008, all newly-diagnosed IIH patients seen in the neuroophthalmology unit at our institution have completed the BQ and been referred for overnight polysomnography as part of their standard evaluation; polysomnography could not be obtained in some patients (e.g., if they declined or did not have medical insurance). We retrospectively included all newly-diagnosed patients satisfying the updated modified Dandy criteria for IIH [9] who had completed the BQ and had undergone polysomnography. We excluded patients who were pregnant, aged less than 16 years, had a prior diagnosis of IIH, or had another cause for their increased intracranial pressure.

Berlin questionnaire

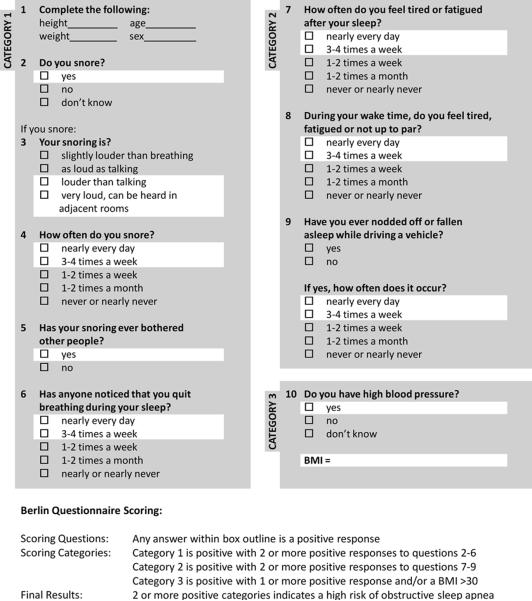

The BQ (Figure 1) incorporates questions about snoring (category 1), daytime somnolence (category 2), and hypertension and BMI (category 3).[5] The BQ was administered at the time of the patient's initial visit. When available, the patient's family or bed partner was asked to confirm the accuracy of responses to the questions about snoring. The overall BQ score was determined, as in previous studies,[5] from the responses to the three categories: scores from the first and second categories were positive if the responses indicated frequent symptoms (>3–4 times/week), whereas the score from the third category was positive if there was a history of hypertension or a BMI >30 kg/m2.[5] Patients were scored as being at high-risk for OSA if they had a positive score on two or more categories, while those who did not were scored as being at low-risk.[5]

Figure 1.

The Berlin questionnaire for obstructive sleep apnea.[5] The questionnaire incorporates questions about snoring (category 1), daytime somnolence (category 2), and hypertension and BMI (category 3).

Polysomnography

All patients had overnight laboratory-based video polysomnography, including electroencephalogram, electro-oculography, surface mentalis and anterior tibialis electromyogram, electrocardiogram, respiratory airflow (measured by thermistor) and effort (measured by piezoelectric sensors), and oxyhemoglobin saturation. The presence of apneas and hypopneas was determined using conventional criteria.[4] The polysomnographic technologists scoring the study and the board-certified sleep specialists who interpreted the studies were blinded to the results of the BQ. The apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) was then calculated as the average number of apneas and hypopneas per hour. OSA was diagnosed when AHI was ≥5.[4]

Data analysis

Univariate analyses were used to summarize the results. The sensitivity and specificity of the BQ for OSA were determined by comparing the number of IIH patients with high-risk and low-risk BQ scores to the number with and without OSA, while the significance of the association between BQ score and OSA was determined using Fisher's exact test.

Results

Patient demographics

Thirty newly diagnosed IIH patients were included. Twenty-four were women. The median age was 32 years (range: 16–54 years). Fifteen were white and fifteen black. The median BMI was 39.8 kg/m2 (range: 27.3–51.7 kg/m2). There was no difference in age, race, or BMI between patients who underwent polysomnography and those who did not (p>0.18).

Berlin questionnaire scores

Twenty of 30 patients (66.7%) had a high risk score for OSA on the BQ, while 10 (33.3%) had a low risk score (Table 1). Sixteen of 24 women (66.7%) and 4 of 6 men (66.7%) had a high-risk score. Eleven of 15 white patients (73.3%) and 9 of 15 black patients (60%) had a high-risk score. Of 30 patients, 17 (56.7%) had a positive score in category 1 of the BQ, 17 (56.7%) had a positive score in category 2, and 28 (93.3%) had a positive score in category 3, in most cases because their BMI was >30 kg/m2. Snoring could not be determined in three patients (10%), as they did not have a bed partner who could corroborate their perceived absence of snoring.

Table 1.

Contingency table of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) determined by polysomnography (apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 5) vs. Berlin questionnaire (BQ) score

| OSA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | ||

| BQ | High risk | 15 | 5 |

| Low risk | 3 | 7 | |

Fisher test: p=0.045

Polysomnography results

Eighteen of 30 patients (60%) had OSA (Table 1), with 7 (23.3%) having mild, 4 (13.3%) having moderate, and 7 (23.3%) having severe OSA. Fourteen of 24 women (58.3%) and 4 of 6 men (66.7%) had OSA. Ten of 15 white patients (66.7%) and 8 of 15 black patients (53.3%) had OSA.

Berlin questionnaire sensitivity and specificity

Fifteen of 20 patients (75%) with a high-risk BQ score had polysomnographically-verified OSA, whereas 7 of 10 (70%) with a low-risk BQ score did not have OSA (Table 1). The sensitivity of the BQ for OSA in IIH patients was 83.3%, the specificity was 58.3%, the positive predictive value was 75%, and the negative predictive value was 70% (Fisher test, p=0.045).

Discussion

Overnight laboratory-based polysomnography is the gold standard test for diagnosing OSA,[4] but given the expense, time-consumption, and inconvenience of polysomnography for many patients, it would be preferable to first use a simple and sensitive screening test to determine an IIH patient's risk for OSA. The BQ can be completed in a few minutes and has been validated as a useful screening tool for identifying persons in the community who are at high-risk for OSA.[5] In one large study, 744 community-dwelling adults completed the BQ; similar numbers of men and women were studied, but most were middle-aged or older (48.9 ± 17.5 yrs, mean ± SD).[5] After completing the BQ, 100 of the participants underwent polysomnography. Fifty-nine of 69 participants (86%) with a high risk score had OSA and 7 of 31 (23%) with a low risk score had OSA, and, thus, the sensitivity and specificity of the BQ for identifying OSA were 86% and 77%, respectively.[5] However, the BQ is not as predictive of OSA in specialized sleep clinics.[10] Indeed, a lower threshold for performing diagnostic polysomnograms on a mixed patient population likely accounts for a lower sensitivity and specificity for identifying OSA (i.e., 68% and 49%, respectively).[10] IIH patients are typically young, in contrast to study and sleep clinic populations, and, thus, it was uncertain that the BQ would reliably identify IIH patients with OSA.[5,10] Because OSA may be associated with IIH,[6,8,11,12] likely increases intracranial pressure,[11] and has been shown to increase cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,[3] we felt compelled to evaluate all IIH patients for OSA with polysomnography until the BQ was validated in the IIH population.

We routinely administered the BQ and obtained diagnostic polysomnography on newly-diagnosed IIH patients, and found a 83% sensitivity, 58% specificity, and 75% positive predictive value of the BQ for identifying OSA in IIH patients. The frequency of snoring might have been underestimated by the BQ, as several patients did not have a bed partner. Nonetheless, our findings demonstrate that the sensitivity of the BQ in IIH patients is comparable to that observed in older community dwellers.

It is important to note that this study was not designed to evaluate for an association between OSA and IIH. Although the majority of our patients had OSA by polysomnography, comparison with age-, sex-, race-, and BMI-matched controls is required to determine if there is any evidence of an association between IIH and OSA.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study was retrospective rather than prospective. However, all patients were evaluated in a standardized fashion, which should have substantially reduced the biases usually associated with retrospective studies. Second, some patients declined polysomnography or did not have it done (e.g., if they did not have medical insurance). However, all patients were referred for polysomnography regardless of their perceived risk for OSA and, thus, bias was minimized as much as possible. Furthermore, there were no systematic differences between the groups of patients who did and did not undergo polysomnography.

Despite these limitations, our study suggests that the BQ is a practical adjunct tool for stratifying IIH patients as to their risk for OSA. Given the significant morbidity associated with OSA, especially in obese individuals, polysomnography should be considered in IIH patients with high-risk BQ scores.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure and Funding: Supported in part by a departmental grant (Department of Ophthalmology) from the Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc, New York, NY, by core grant P30-EY06360. Dr Bruce received research support from the National Institutes of Health/Public Health Service (KL2-RR025009, UL1-RR025008), National Institutes of Health/National Eye Institute (K23-EY019341), and the Knights Templar Eye Foundation and also the American Academy of Neurology Practice Research Fellowship. Dr Biousse received research support from National Institutes of Health/Public Health Service (UL1-RR025008). Dr Newman is a recipient of the Research to Prevent Blindness Lew R. Wasserman Merit Award. Dr Rye received research support from the NIH/USPHS (NS055015 and MH083746) and is a consultant for the USPHS, Merck Co, Inc, and UCB Inc.

References

- 1.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, Redline S, Newman AB, Gottlieb DJ, Walsleben JA, Finn L, Enright P, Samet JM, Sleep Heart Health Study Research Group Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:893–900. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.8.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Punjabi NM, Caffo BS, Goodwin JL, Gottlieb DJ, Newman AB, O'Connor GT, Rapoport DM, Redline S, Resnick HE, Robbins JA, Shahar E, Unruh ML, Samet JM. Sleep-disordered breathing and mortality: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL, Quan SF. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; Westchester, IL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:485–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcus DM, Lynn J, Miller JJ, Chaudhary O, Thomas D, Chaudhary B. Sleep disorders: a risk factor for pseudotumor cerebri? J Neuroophthalmol. 2001;21:121–123. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200106000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser JA, Bruce BB, Rucker J, Fraser LA, Atkins EJ, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Risk factors for idiopathic intracranial hypertension in men: a case-control study. J Neurol Sci. 2010;290:86–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee AG, Golnik K, Kardon R, Wall M, Eggenberger E, Yedavally S. Sleep apnea and intracranial hypertension in men. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:482–485. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2002;59:1492–1495. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000029570.69134.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmadi N, Chung SA, Gibbs A, Shapiro CM. The Berlin questionnaire for sleep apnea in a sleep clinic population: relationship to polysomnographic measurement of respiratory disturbance. Sleep Breath. 2008;12:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s11325-007-0125-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jennum P, Borgesen SE. Intracranial pressure and obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1989;95:279–283. doi: 10.1378/chest.95.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wall M, Purvin V. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in men and the relationship to sleep apnea. Neurology. 2009;72:300–301. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000336338.97703.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]