Abstract

Background

Warfarin is a high-risk medication where patient information may be critical to help ensure safe and effective treatment. Considering the time constraints of healthcare providers, the internet can be an important supplementary information resource for patients prescribed warfarin. The usefulness of internet-based patient information is often limited by challenges associated with finding valid and reliable health information. Given patients' increasing access of the internet for information, this study investigated the quality, suitability and readability of patient information about warfarin presented on the internet.

Method

Previously validated tools were used to evaluate the quality, suitability and readability of patient information about warfarin on selected websites.

Results

The initial search yielded 200 websites, of which 11 fit selection criteria, comprising seven non-commercial and four commercial websites. Regarding quality, most of the non-commercial sites (six out of seven) scored at least an ‘adequate’ score. With regard to suitability, 6 of the 11 websites (including two of the four commercial sites) attained an ‘adequate’ score. It was determined that information on 7 of the 11 sites (including two commercial sites) was written at reading grade levels beyond that considered representative of the adult patient population with poor literacy skills (e.g. school grade 8 or less).

Conclusion

Despite the overall ‘adequate’ quality and suitability of the internet derived patient information about warfarin, the actual usability of such websites may be limited due to their poor readability grades, particularly in patients with low literacy skills.

Keywords: Warfarin, internet, health information, quality, suitability, readability

What this study adds:

Patient information currently available on internet warfarin-specific websites is generally adequate in terms of quality and suitability; however, the readability tends to be poor.

Patient information available on warfarin-specific websites may lack broad cross-cultural utility.

When considering the suitability of patient information available on warfarin-specific websites, healthcare professionals should consider the quality and readability of the information before recommending a particular website to their patients.

Background

The World Wide Web (WWW), or simply the ‘web’ or the ‘internet', has become a significant source of health information that is increasing in popularity.1,2 Data from the USA and Europe shows that as many as 61% of the general adult population, including older people (aged 65 years and over), seek information on the internet about their health and related medical issues.1,2 Evidence suggests that the use of internet-based health information has encouraged some patients to be more proactive in the management of their own health/medical conditions.3 It is important to note,however, that this cost-effective and easily accessible resource4,5 for health information is largely unregulated.6 The internet may potentially contain poor quality and unsuitable information,7, 8 which is difficult to read and understand.4,5,9,10

Quality of health information on the internet

Despite its potential as a significant patient information resource, the internet's usefulness is often limited by the challenges associated with finding good quality health information that comes from authentic and reliable sources.8,9 Previous studies9,11 have reported that more than half of websites provide poor quality health information. Currently available quality evaluation tools, e.g., Health-Related Website Evaluation Form (HRWEF)12 and Quality Component Scoring System (QCSS)13,14 can be used to evaluate the quality of internet-based health information using criteria such as: purpose of the content; disclosure of authors/sponsors; currency of information; accuracy and reliability of information; accessibility and interactivity (e.g. allows patients to make comments or post questions online); readability of information; and graphics/layout of information.6,9,11,15 However, since none of these quality evaluation tools individually addresses each of these criteria,6,16 a comprehensive evaluation of the quality of information available on the internet requires the application of multiple tools.

Suitability health information on the internet

Suitability is an important aspect of written health information that helps to predict how well the information can be read and understood by general patient populations, and in particular, those with limited literacy skills. Inadequate attention may be paid to the suitability of internet-based health information despite recognition that the internet readership includes an adult population with more than 25% having low literacy skills.1,17 The Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM)18 is an available and commonly used10,19,20 rating scale, which measures suitability in terms of content, literacy demand, graphics and layout, learning stimulation/motivation and cultural specificity.

Readability of health information on the internet

Readability formulae, such as the Flesch-Kincaid (F-K) grade formula21 and the SMOG (Simple Measure of Gobbledygook) grade formula,22 are commonly used to assess the readability of health information.23,24 Previous studies9,23,24 using such formulae have shown that in most cases (e.g., between 60-96%) health information on the internet is written at high grade levels (e.g. school grade 12). This is particularly concerning for older patients with poor literacy skills, estimated to be approximately 16% amongst those aged between 60-65 years, and 58% among those aged 85 years and above.25 Further, this older group of patients are more likely to be cognitively challenged, often taking several medications for co-morbid conditions.26 It is recommended therefore that health information should be written at a 6 to 8 school grade level9,27 to ensure that it can be read and understood by the general adult patient population, including those older patients with poor literacy skills.

Increasingly, patients and carers are turning to the internet for information pertaining to complex health problems and/or complicated therapies. A case in point is warfarin therapy, which is one of the 10 most prescribed medications used worldwide and its use has increased by approximately 8-10% per year, mostly because of the increased prescribing of warfarin for older patients (at risk of chronic thromboembolic complications) who have been diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (AF).28-30 Evidence suggests that 55-60% of older patients (aged 65 years or more) with AF are currently treated with warfarin.31-33 Although a potentially life-saving medication, warfarin therapy carries a risk of excessive and potentially life-threatening bleeding complications owing to its complex pharmacology and very narrow therapeutic range of dosage.34 For example, the rate of major bleeding events associated with oral anticoagulation therapy is 7.2 per 100 patient-year as shown in a meta-analysis.35 Further, warfarin is attributed to about 10% of all preventable adverse drug events in high-risk patient groups such as elderly patients.36 Providing patient education and information about warfarin is therefore an essential component for safe and effective warfarin management along with other measures that include regular blood testing and dosage adjustment.34-37 However, health practitioners short of time could fail to effectively convey important warfarin information to their patients.38 The internet may therefore be seen as a very useful supplementary information resource for many patients receiving warfarin therapy. The quality, suitability and readability of patient information about warfarin on the available websites we evaluated two years ago, are unknown. Therefore, our aim in this study was to evaluate the quality, suitability and readability of patient information on the internet about warfarin. The specific objectives were to inform health professionals about the weaknesses and strengths of the available information, as well as to demonstrate a process for the evaluation of the quality, suitability and readability of internet-based health information.

Method

A quantitative study, comprising the evaluation of quality, suitability and readability of health information about warfarin for patients extracted from systematically selected websites, was conducted during August-September, 2009.

Identification and selection of the websites

Websites providing information about warfarin for adult patients were identified via the key internet search engines: Google, Yahoo, Bing and AltaVista, using search terms such as ‘warfarin', ‘oral anticoagulation', and ‘website'. The first 200 websites (first 20 search pages containing 10 entries per page) yielded by each of the search engines were screened to identify potential websites providing patient information about warfarin, and then accessed to review the content. Inclusion criteria for selecting websites for assessment were: written in the English language, dedicated to patients only, and specific to warfarin alone. Additionally, websites that could not be accessed due to a broken/dead link were excluded.

Assessment and evaluation of the information on the websites

Validated tools were used to assess the quality, suitability and readability of web-based patient information about warfarin. A brief description of selected evaluation tools is provided below and in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of the QUALITY and SUITABILITY evaluation tools.

| Evaluation tool | No. of criteria | Scoring system | Quality/Suitability score and rating |

| Quality evaluation of information | |||

| Health-Related Website Evaluation Form (HRWEF)(11) | 36 | 0=Not applicable 1=Disagree 2=Agree |

>90% = Excellent 75-89 =Adequate <75 =Poor |

| Quality Component Scoring System (QCSS)(12,13) | 21 | 0=No information 1=Partial information 2=Complete information |

>80% =Excellent 70-79% =Very good 60-69% =Good 50-59% =Fair <50% =Poor |

| Suitability evaluation of information | |||

| Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM)(17) | 22* | 0=Not suitable 1=Adequate 2=Superior |

70-100%) =Superior 40-69% =Adequate 0-39% =Not suitable |

Only 21 criteria were assessed in the study and the criterion ‘cover graphics’ was omitted as it did not apply to websites.

Quality of information:

The Health-Related Website Evaluation Form (HRWEF)12 and the Quality Component Scoring System (QCSS)13,14 were used to evaluate the quality of the selected websites (Table 1). The principal researcher and three other independent researchers assessed the quality of the information using both tools.

Suitability of information:

The validated and reliable SAM instrument18 was used to evaluate the suitability of information on the selected websites (Table 1). Flesch-Kincaid reading grades for each of the websites were used by the researchers to determine the ‘reading grade level’ criterion of the SAM instrument. The evaluation of suitability was conducted by the principal researcher and three other independent researchers.

Readability of information:

It is generally accepted that, in evaluating the readability grades/scores of written information, the use of more than one readability formula improves the reliability of readability scores,39 hence we used two readability formulae in this study (F-K grade level formula21 and the SMOG formula.22 For F-K calculations, written information from each selected website was copied and pasted into a blank Microsoft Office Word (Professional Edition 2003) document which was then evaluated for readability. The final grade level (i.e., the average school grade level of reading ability required to comprehend the information) for each website was reported as the average of the combined individual grade levels calculated for each webpage. SMOG readability grades were measured by using both the manual SMOG formula22 and the online SMOG calculator.40 Manual SMOG calculations involved copying and pasting the relevant patient information from the websites into a separate blank document, and then evaluated for readability by the principal researcher as well as two independent researchers using the same 30 lines from the beginning, middle, and end of the document. Online SMOG calculations, however, involved cutting and pasting the relevant patient information from each website into the online tool to generate an automatic SMOG readability grade. In doing so, the online SMOG calculator served to confirm the manual SMOG calculations.

Inter-rater reliability and statistical analyses

To verify the reliability of the findings, the quality and suitability scores were cross-checked against the evaluations undertaken by all the eight assessors (in some cases an individual researcher was involved in more than one evaluation). The quality and suitability coding of all websites were assessed for inter-rater reliability via intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs), with a high ICC value (maximum 1.0) indicating no variance in the scoring between different assessors. The ICC values calculated for HRWEF, QCSS, and the SAM were 0.8, 0.8 and 0.7 respectively, indicated a fair to good level of consistency for the quality and suitability rating measurements. Since the F-K grades were calculated using computerised software, inter-rater consistency was not measured. The ICC value for manually calculated SMOG grade levels was 1.0 which indicated perfect agreement between the different assessors. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS)41 was used to conduct descriptive statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation, proportion, range) and to calculate ICC values.

Results

Characteristics of the websites providing information about warfarin

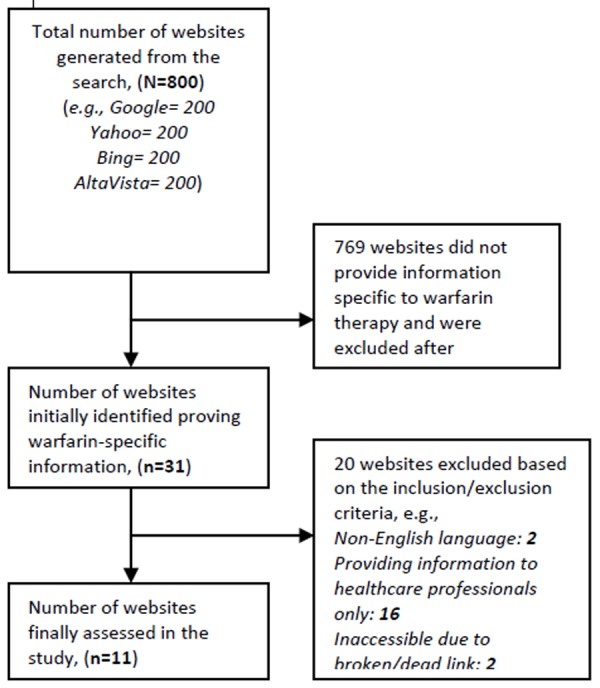

The selection of the potential websites is clearly outlined in Figure 1. Based on the stated inclusion criteria, 11 websites were finally evaluated for the quality, suitability and readability of information. Four of these websites were identified as commercial sites (Table 2) (e.g. published by the pharmaceutical industry or for-profit organisations) and the remaining seven were non-commercial sites (e.g. published by government/education/non-profit organisations or patient support groups).

Figure 1: Schematic presentation of identifying the warfarin-specific websites.

Table 2. Evaluation scores and ratings for QUALITY of the websites’ information (N=11): Quality Rating Scale/(Score):

| HRWEF | QCSS | |

| Websites Evaluated | Overall % Score/ Rating | Overall % Score/ Rating |

| A. www.anticoagulation.com.au | 88.2 (Adequate) | 92.9 (Excellent) |

| B. www.anticoagulationeurope.org | 76.7 (Adequate) | 71.4 (Very Good) |

| C. www.clotcare.com | 84.8 (Adequate) | 78.6 (Very Good) |

| D. www.coaguchek.com† | 78.3 (Adequate) | 64.3 (Good) |

| E. www.coumadin.com† | 73.1 (Poor) | 42.9 (Poor) |

| F. www.ismaap.org | 81.5 (Adequate) | 71.4 (Very Good) |

| G. www.mybloodthinner.org | 73.3 (Poor) | 33.3 (Poor) |

| H. www.ptinr.comt | 68.0 (Poor) | 25.0 (Poor) |

| I. www.stoptheclot.org | 82.4 (Adequate) | 85.7 (Excellent) |

| J. www.tigc.org | 82.3 (Adequate) | 71.4 (Very Good) |

| K. www.warfarinfo.comt | 66.7 (Poor) | 71.4 (Very Good) |

| Mean (SD) / Rating 95% Confidence Interval | 77.8 (6.9) /(Adequate) 73.1 - 82.4 | 64.4 (21.6)/ (Good) 49.9 - 78.9 |

HRWEF: Excellent (>90%), Adequate (75-89%), Poor (<75%) QCSS: Excellent (>80%); Very good (70-79%); Good (60-69%); Fair (50-59%); Poor (<50%) †Commercial sites

Quality of internet-based health information about warfarin for patients

Table 2 highlights that the quality of the internet-based information about warfarin was at least ‘adequate', ‘good’ or ‘moderate’ for the majority of sites based on the overall scores from the HRWEF and QCSS instruments. The commercial sites were found to have overall poorer quality scores/ratings compared to the non-commercial sites.

The Health-Related Website Evaluation Form (HRWEF):

Using the HRWEF instrument, none of the websites scored an ‘excellent’ (>90%) rating for quality (Table 2). Whilst seven of the sites achieved ‘adequate’ scores for quality, the remaining four sites (three of which were commercial sites: www.ptinr.com; www.coumadin.com; and www.warfarininfo.com) attained ‘poor’ scores.

The Quality Component Scoring System (QCSS):

Using the overall QCSS scores, two websites, www.anticoagulation.com.au and www.stoptheclot.org, were found to provide information of ‘excellent’ quality, while six other sites provided information of at least ‘good’ quality (Table 2). Similar to HRWEF findings, the commercial sites www.ptinr.com and www.coumadin.com achieved overall ‘poor’ quality scores.

In summary, the non-commercial website www.anticoagulation.com.au and the commercial site www.ptinr.com consistently attained the highest and lowest quality scores/ratings, respectively. Overall, fairly consistent results relating to the quality scores/ratings were yielded using the HRWEF and QCSS evaluation tools (Table 2), except for the www.warfarinfo.com site, which achieved a ‘poor’ quality rating using the HRWEF tool and a ‘very good’ rating using the QCSS.

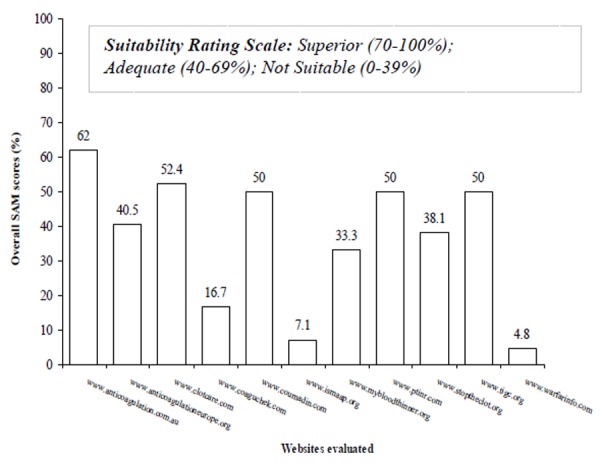

Suitability of the internet-based health information about warfarin

Based on overall SAM scores (Figure 2), none of the websites achieved ‘superior’ ratings for suitability. Of the six sites attaining ‘adequate’ suitability score, two were commercial sites (www.coumadin.com and www.ptinr.com) (Figure 2). Regarding individual SAM criteria, less than half of the sites adequately addressed issues relating to layout and graphics, and learning motivation (Table 3). For example, relevant graphics/illustrations or subheadings were presented on only three of the non-commercial websites (www.anticoagulation.com.au; www.clotcare.com; and www.mybloodthinner.org). None of the sites addressed the cultural specificity of information relating to language, experience or provision of examples to patients from diverse socio-demographic backgrounds based on the SAM tool. In summary, those websites achieving the highest and lowest suitability scores/ratings were www.anticoagulation.com.au and www.warfarinfo.com, respectively.

Figure 2: Evaluation scores and ratings for SUITABILITY of the selected websites, (N=11).

Table 3. Websites adequately addressing general SUITABILITY criteria, (N=11).

| Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) evaluation criteria | Websites addressing the SAM criteria adequately** |

| 1. CONTENT | |

| Purpose is evident | A-K |

| Content about behaviours | A-E, G-J |

| Scope is limited | A-E, G, H,J |

| Summary or review included | A, C-E, G-J |

| 2. LITERACY DEMAND | |

| Reading grade level | A, H, J, K |

| Writing style, active voice | A-E, G-J |

| Vocabulary uses common words | A, B, D, E, G, H, J |

| Context is given first | A-J |

| Learning aids via "road sign" | A, C, E, G-J |

| 3. GRAPHICS | |

| Cover graphic shows purpose | N/A* |

| Type of graphics | A, C, G |

| Relevance of illustrations | A, C, G |

| List, tables, etc. explained | A |

| Captions used for graphics | None |

| 4. LAYOUT AND TYPOGRAPHY | |

| Layout factors | A, C, G, H, J |

| Typography | A-E, G-K |

| Subheads (“chunking”) used | A, H, I |

| 5. LEARNING STIMULATION, MOTIVATION | |

| Interaction used (question-and-answer format used) | B-E, G-J |

| Behaviours are modelled and specific | A, C-E, G-J |

| Motivation- self-efficacy | A, E, H-J |

| 6. CULTURAL APPROPRIATENESS | |

| Match in logic, language, experience | None |

| Cultural image and examples | None |

N/A not applicable for website

Required score for ‘adequate’ suitability: 40-69%

Readability of internet-based health information about warfarin

Readability grades for all evaluated websites are shown in Table 4. Whilst there was some variability in the actual readability grades attained, the ranking order of the sites (lowest versus highest grades) was consistent across each of the tools used. Brief descriptions of the readability grades determined by each of the readability tools are as follows:

Table 4. Evaluation scores and Grade Levels for READABILITY of the websites' information, (N=11).

| Websites Evaluated | F-K Grade | SMOG Grade1 | SMOG Grade2 |

| A. www.anticoagulation.com.au | 8.1 | 9.0 | 12.3 |

| B. www.anticoagulationeurope.org | 9.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 |

| C. www.clotcare.com | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 |

| D. www.coaguchek.com† | 12.3 | 13.0 | 15.3 |

| E. www.coumadin.com† | 9.1 | 11.0 | 13.0 |

| F. www.ismaap.org | 12.4 | 12.0 | 15.1 |

| G. www.mybloodthinner.org | 11.0 | 11.0 | 15.0 |

| H. www.ptinr.com† | 6.0 | 9.0 | 10.4 |

| I. www.stoptheclot.org | 10.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 |

| J. www.tigc.org | 8.2 | 9.0 | 11.1 |

| K. www.warfarinfo.com† | 8.0 | 11.0 | 13.0 |

| Mean (SD) 95% Confidence Interval | 9.6(2.1) (8.2-11.0) | 11.0 (1.6) (10.1-12.3) | 13.4 (1.7) (12.3-14.5) |

Grade level from SMOG manual calculation;

Grade level measured by online SMOG calculator;

Commercial sites

Flesch-Kincaid (F-K) readability grade:

The mean F-K readability grade level was measured as 9.6 (SD 2.1; 95% CI 8.2-11.0). The F-K formula found that four of the websites (including two non-commercial sites; www.anticoagulation.com.au, www.tigc.org; and two commercial sites: www.ptinr.com, www.warfarinfo.com) were written at an approximately grade 8 school level or below (Table 4), in line with what is the recommended level for written health information. The www.ptinr.com site (a commercial site) provided information that was written at the lowest readability grade (grade 6) based on the F-K grades, whereas www.clotcare.com, www.ismaap.org (noncommercial sites) and www.coaguchek.com (commercial site) provided information that was written at the highest readability level (approximately grade 12).

SMOG readability grade formula:

The mean SMOG readability grade levels were measured as 11.0 (SD 1.6; 95% CI 10.1-12.3) and 13.4 (SD 1.7; 95% CI 12.3-14.5) for the manual and online SMOG formulae, respectively. Table 4 highlights that the SMOG readability grades measured by the manual and online calculator ranged between grades 913 and grades 10.4-15.3, respectively (i.e., varying by 1-3 grade levels).

Discussion

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to have systematically evaluated websites providing information for patients about warfarin therapy. Specifically, this study has audited the quality, suitability and readability of the content of these websites to help gauge their utility for the general adult patient population including those with low literacy skills.34 The results of this study provide some important insights regarding medicines information on the internet, specifically information about warfarin therapy. Overall, the aspects of quality and suitability are adequate; the readability is generally poor and targeted toward patients with high skills.

This study found that the quality of internet-based information about warfarin on most of the evaluated websites was generally adequate. These findings are consistent with the findings from previous studies,14,42,43 which have evaluated health information available on the internet for a range of different chronic diseases. This study also highlights that the quality of information about warfarin on the evaluated commercial websites is poor, which is also consistent with the findings of other studies.9,26,42 This is an important finding given the increasing reliance of patients on the internet as an information resource,1,2 as well as the increasing referral of patients by healthcare professionals to such websites. The relative advantages and disadvantages of non-commercial and commercial sites need to be carefully identified and communicated to patients, given that some commercial sites may not always be reliable sources of good quality information about warfarin.

Similar to the findings of a US-based study10 evaluating the suitability of health information available on the internet about osteoporosis using the SAM instrument, the present study found that information about warfarin on most of the selected websites (including two commercial sites) was generally adequate (i.e. satisfactory) for the general adult population with limited literacy skills. Despite the overall adequate suitability ratings of information on these selected websites, specific deficiencies were identified regarding specific SAM criteria, such as graphics, layout and cultural appropriateness. This study's finding relating to the limited use of graphics/illustrations is consistent with those of other studies27,44 evaluating health information available on the internet. This is unfortunate given that these features help to effectively convey and define complex medical words and terminologies, and/or findings from clinical studies (e.g., risk versus benefit), thus having the potential to improve patient understanding of health information.45,46

In ethnically diverse countries, it is important to consider the cultural appropriateness of the information presented, given the ubiquitous nature of the internet making such information accessible to patients from a range of social, ethnic and cultural backgrounds.47,48 The present study highlights the issue that internet-based health information about warfarin does not always consider issues relevant to patients from non-mainstream ethnic groups, and/or how people from different ethnicities may interpret or apply the information. This reflects previous studies23,48 that have evaluated health information available on the internet about cancer therapy and which reported similar findings. Whilst it is difficult to cater to the needs of all existing socio-ethno-cultural groups, several key health websites have implemented simple measures to help meet the needs of their target populations; for example, the Canadian Breast Cancer Network (www.cbcn.ca) provides links to culturally relevant breast cancer information for aboriginal people, ethnic minorities and those for whom English is a second language. In regard to warfarin therapy, where complex information about lifestyle issues must be clearly communicated to patients (e.g., drug interactions with food/diet, risks of bleeding with normal activities of daily living), it is important to consider and address relevant socio-ethno-cultural ‘habits’ (e.g., diets, religious practices, health beliefs) within internet-based health information.

In regard to the readability, this study highlights that the information presented on most websites is written at readability levels well beyond (e.g. grade 12) that of the average adult population. This result is consistent with Estrada et al (2000)25 and is important given that many patients receiving warfarin therapy are older patients with poor literacy skills. 25 For these patients, as well as others with poor literacy skills (e.g. poorly educated, culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds), patient information about warfarin should be written at approximately school grade 8 or less to facilitate better understanding.6,25 Importantly, although a difference by approximately 2-4 grades was observed between the readability grades measured by the SMOG and F-K readability formulae, such a difference is not uncommon and is considered the result of variation between different measurement scales.24 Similarly, even though there is a disparity between the calculated reading grade levels for the manual and online SMOG formulae, they are all consistent with regard to the trends in increased reading grade levels required for the different websites. However, the comparatively higher readability grades generated by the online SMOG calculator compared to that of the manual SMOG formula warrant that care should be taken when using the online tools to measure the readability levels of health information available on the internet.

In summary, a wide variability in the quality, suitability and readability scores of internet-based health information about warfarin has been identified in this study. The overall scores indicate that whilst a website may score highly regarding quality parameters it may also achieve poor scores for other evaluated criteria, such as suitability and readability. In the current study, only www.anticoagulation.com.au consistently attained higher scores/ratings in terms of the quality, suitability and readability of information abut warfarin.

Collectively, the study highlights that there are key areas for improvement to help increase the utility of the health and medicines information in relation to warfarin therapy. As a first measure, healthcare professionals might actively be aware of the information presented on websites, as well as purposefully identifying websites that patients may be accessing. By doing so, they will be able to not only identify misinformation but better direct their patients to more effective websites. Secondly, developers of internet-based health information could carefully consider each of these criteria and ensure that the information presented on their sites is relevant and suitable for their target audience (patient population) across each of the three criteria.

Limitations of the study

In interpreting the findings of this study, it is important to consider some of its potential limitations. Only English language sites were evaluated, and therefore the findings may not be generalisable to those websites written in other languages. The subjective nature of some quality and suitability criteria may potentially introduce variability in scoring, although a fair to good level of inter-rater consistency across the ratings was demonstrated. Furthermore, the SAM instrument principally evaluates the suitability of health information for the general adult population with limited literacy and it is not known to what extent this caters to other patient groups (e.g. older patients). The readability tools may have overestimated the required readability levels because they do not discriminate between commonly and infrequently used terms/words. For example, the analysis would not include commonly used, albeit polysyllabic, clinical and medical terms such as ‘warfarin’ and ‘anticoagulation'. Finally, a conflicting finding regarding the quality score/rating was measured by the HRWEF and the QCSS evaluation tools for the site www.warfarinfo.com. However, such a finding may not be entirely unexpected given the different scoring/rating systems used and characteristics of evaluation criteria included in the above quality evaluation tools.

Conclusion

Whilst the quality and suitability of internet-based health information about warfarin is generally adequate, the actual usability of the sites examined in this study may be limited due to poor readability levels, which could be problematic in patients with poor literacy skills. Since the internet can be readily accessed as a valuable patient information resource, healthcare professionals have an opportunity to direct patients to websites that provide readable information of good quality and suitability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Renske Hebing, Maya von Moos, Isabella Renman, Shirley Sparla, Judith van Dalem, Ashraf Eissa and Viki Yaputra for their assistance in testing the tools used in the study, and Dr Kylie Williams and Dr Warren Rich for their feedback. The preliminary results of this study were presented (as poster presentation) at the Australasian Pharmaceutical Sciences Association annual scientific meeting, Hobart (Tasmania, Australia) 9- 11 December, 2009.

Footnotes

PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned. Externally peer reviewed

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

FUNDING

No financial support was received for this study

ETHICS COMMITTEE APPROVAL

No ethics approval was required for this study

Please cite this paper as: Nasser S, Mullan J, Bajorek B. Assessing the quality, suitability and readability of web-based information about warfarin for patients. AMJ 2012, 5, 3, 194-203. http//dx.doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2012.862

References

- 1.Fox S, Jones S. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Washington, D.C: Jun, 2009. The Social Life of Health Information; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreassen HK, Bujnowska-Fedak MM, Chronaki CE, Dumitru RC, Pudule I, Santana S, Voss H, Wynn R. European citizens’ use of E-health services: A study of seven countries. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CJ, Gray SW, Lewis N. Internet use leads cancer patients to be active health care consumers. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:S63–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CH, Taal E, Smit WM, Moens HB, Siesling S, Syedel ER, van de Laar MA. Health-related Internet use by patients with somatic diseases: Frequency of use and characteristics of users. Informatics for Health & Social Care. 2009;34(1):2009–34. doi: 10.1080/17538150902773272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner TH, Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Singer S. Use of the internet for health information by the chronically ill. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1(4):2004–1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harland J, Bath P. Assessing the quality of websites providing information on multiple sclerosis: evaluating tools and comparing sites. Health Informatics J. 2007;13(3):2007–13. doi: 10.1177/1460458207079837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maloney S, Ilic D, Green S. Accessibility, nature and quality of health information on the Internet: a survey on osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2005;44:382–85. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berland GK, Elliott MN, Morales LS, Algazy JI, Kravitz RL, Broder MS, Kanouse DE, Munoz JA, Puyol JA, Lara M, Watkins KE, Yang H, McGlynn EA. Health information on the Internet: Accessibility, quality, and readability in English and Spanish. JAMA. 2001;285(20):2001–285. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.20.2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Marel S, Duijvestein M, Hardwick JC, van den Brink GR, Veenendaal R, Hommes DW, Fidder HH. Quality of web-based information on inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(12):2009–15. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallace LS, Turner LW, Ballard JE, Keenum AJ, Weiss BD. Evaluation of web-based osteoporosis educational materials. J. Womens Health. 2005;14(10):2005–14. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oermann MH, Gerich J, Ostosh L, Zaleski S. Evaluation of asthma websites for patient and parent education. J Pediatr Nurs. 2003;18(6):2003–18. doi: 10.1016/s0882-5963(03)00161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teach L. Health-Related Web Site Evaluation Form. Rollins School of Public health, Emory University; USA: 1998. Available from: http://www.sph.emory.edu/WELLNESS/instrument.html (accessed on Jul 29, 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martins EN, Morse LS. Evaluation of internet websites about retinopathy of prematurity patient education. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:565–68. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.055111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterlin BL, Gambini-Suarez E, Lidicker J, Levin M. An analysis of cluster headache information provided on Internet websites. Headache. 2008;48:378–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim P, Eng TR, Deering MJ, Maxfield A. Published criteria for evaluating health related web sites: review. BMJ. 1999;318:647–49. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7184.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernstama EV, Sheltona DM, Waljia M, Meric-Bernstamb F. Instruments to assess the quality of health information on the World Wide Web: what can our patients actually use? Int J Med Inf. 2005;74:13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabharwal S, Badarudeen S, Kunju SU. Readability of online patient education materials from the AA OS web site. Clin Orthop. 2008;466:1245–50. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0193-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. 2. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1996. Teaching patients with low literacy skills; pp. 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Turner LW, Keenum AJ, Weiss BD. Suitability of written supplemental materials available on the Internet for nonprescription medications. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2006;63:71–78. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vallance JK, Taylor LM, Lavallee C. Suitability and readability assessment of education print resources related to physical activity: Implications and recommendations for practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72:342–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, Chissom BS. Millington, TN: Navy Research Branch; 1975. Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLaughlin GH. SMOG grading- a new readability formula. J Reading. 1969;12:639–46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman DB, Hoffman-Goetz L, Arocha JF. Readability of cancer information on the Internet. J Cancer Educ. 2004;19:117–22. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce1902_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson M. Readability and patient education materials used for low-income populations. Clin Nurse Spec. 2009;23(1):2009–23. doi: 10.1097/01.NUR.0000343079.50214.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Estrada CA, Hryniewicz MM, Higgs VB, Collins C, Byrd JC. Anticoagulant patient information material is written at high readability levels. Stroke. 2000;31:2966–70. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.12.2966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunst H, Khan KS. Quality of web-based medical information on stable COPD: comparison of non-commercial and commercial websites. Health Info Libr J. 2002;19:42–8. doi: 10.1046/j.0265-6647.2002.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Croft DR. An evaluation of the quality and contents of asthma education on the World Wide Web. Chest. 2002;121:1301–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.4.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bereznicki LR, Peterson GM, Jackson SL, Jeffrey EC. The risks of warfarin use in the elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006;5(3):2006–5. doi: 10.1517/14740338.5.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker RI, Coughlin PB, Gallus AS, Harper PL, Salem HH, Wood EM. Warfarin Reversal Consensus Group. Warfarin reversal: consensus guidelines, on behalf of the Australasian Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Med J Aust. 2004;181:492–97. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wittkowsky AK, Boccuzzi SJ, Wogen J, Wygant G, Patel P, Hauch O. Frequency of concurrent use of warfarin with potentially interacting drugs. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24(12):2004–24. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.17.1668.52338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srivastava A, Hudson M, Hamoud I, Cavalcante J, Pai C, Kaatz S. Examining warfarin underutilization rates in patients with atrial fibrillation: Detailed chart review essential to capture contraindications to warfarin therapy. Thrombosis Journal. 2008;6(6) doi: 10.1186/1477-9560-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Go AS, Hylek EM, Borowsky LH, Phillips KA, Selby JV, Singer DE. Warfarin use among ambulatory patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: The AnTicoagulation and Risk factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:927–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-12-199912210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krass I, Ogle SJ, Duguid JJ, Shenfield GM, Bajorek BV. The impact of age on antithrombotic use in elderly patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Australas J Ageing. 2002;21(1):2002–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bajorek BV, Ogle SJ, Duguid MJ, Shenfield GM, Krass I. Balancing risk versus benefit: the elderly patient's perspective on warfarin therapy. Pharmacy Practice (Internet) 2009;7(2):2009–7. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552009000200008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linkins L, Choi PT, Douketis JD. Clinical Impact of bleeding in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism: A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:893–900. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bockwoldt D. Antithrombosis management in community-dwelling elderly: Improving safety. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31(1):2010–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mullan J. Wollongong: The University of Wollongong; 2005. To develop and trial a new warfarin education programme [PhD Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lane DA, Ponsford J, Shelley A, Sirpal A, Lip GY. Patient knowledge and perceptions of atrial fibrillation and anticoagulant therapy: Effects of an educational intervention programme. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:354–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedman DB, Hoffman-Goetz L. A systematic review of readability and comprehension instruments used for print and web-based cancer information. Health Educ Behav. 2006;33(3):2006–33. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLaughlin GH. SMOG (Simple Measure of Gobbledygook) calculator. Available from: http://wwwharrymclaughlincom/SMOGhtm, accessed 17 Aug 2009)

- 41.(SPSS) SPftSS. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2008. SPSS for Windows: version 17.0 [Computer Software] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thakurdesai PA, Kole PL, Pareek RP. Evaluation of the quality and contents of diabetes mellitus patient education on Internet. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53:309–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandvik H. Health information and interaction on the internet: a survey of female urinary incontinence. BMJ. 1999;19:29–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7201.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kisely S, Ong G, Takyar A. A survey of the quality of web based information on the treatment of schizophrenia and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37:85–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawley ST, Zikmund-Fisher B, Ubel P, Jancovic A, Lucas T, Fagerlin A. The impact of the format of graphical presentation on health-related knowledge and treatment choices. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;73:448–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mansoor LE, Dowse R. Effect of pictograms on readability of patient information Materials. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(37):2003–37. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Birru MS, Steinman RA. Online health information and low-literacy African Americans. J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e26. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Friedman DB, Kao EK. A comprehensive assessment of the difficulty level and cultural sensitivity of online cancer prevention resources for older minority men. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(1) Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/jan/07_0146.htm, accessed 11 Feb 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]