Abstract

The 54‐item Social Adjustment Scale – Self‐report (SAS‐SR) is a measure of social functioning used in research studies and clinical practice. Two shortened versions were recently developed: the 24‐item SAS‐SR: Short and the 14‐item SAS‐SR: Screener. We briefly describe the development of the shortened scales and then assess their reliability and validity in comparison to the full SAS‐SR in new analyses from two separate samples of convenience from a family study and from a primary care clinic.

Compared to the full SAS‐SR, the shortened scales performed well, exhibiting high correlations with full SAS‐SR scores (r values between 0.81 and 0.95); significant correlations with health‐related quality of life as measured by the Short Form 36 Health Survey; the ability to distinguish subjects with major depression versus other psychiatric disorders versus no mental disorders; and sensitivity to change in clinical status as measured longitudinally with the Symptom Checklist‐90 and Global Assessment Scale.

The SAS‐SR: Short and SAS‐SR: Screener retained the areas assessed by the full SAS‐SR with fewer items in each area, and appear to be promising replacements for the full scale when a shorter administration time is desired and detailed information on performance in different areas is not required. Further work is needed to test the validity of the shortened measures. Copyright © 2011 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: social adjustment scale–self‐report (SAS‐SR), screening, reliability, validity

Introduction

The importance of social adjustment as an index of mental health can be traced to the 1960s, when deinstitutionalization led to the realization that patients with chronic mental disorders were having problems adjusting to community life. It became increasingly clear that the treatment and clinical course of individuals with mental disorders were often influenced by the patient's family, social, and work life. The exclusive focus on patients' symptoms began to be seen as inadequate. Many clinical and epidemiological studies since then have documented the enormous social impairment associated with mental disorders such as depression (e.g. Klerman and Weissman, 1992; Mintz et al., 1992; Greenberg et al., 1993; Wittchen et al., 2000; Kessler et al., 2003; Rytsala et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2007; Bolton et al., 2009). In the 1990s, the Global Burden of Disease study found that the disability associated with mental disorders ranked as high as the disability associated with cardiovascular and respiratory diseases (Murray and Lopez, 1996; Üstün, 1999). Gold‐standard classification systems of medical and mental disorders now incorporate measures of functioning. The World Health Organization's (WHO's) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF; WHO, 2001) assesses disability in physical, social, occupational, and other areas. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM‐IV‐TR; APA, 2000) includes the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) for the clinician to rate social, occupational, and psychological functioning. There is continuing interest in differentiating functional impairment from symptoms, and in measuring each of them independently (Ustün and Kennedy, 2009).

Several short scales for assessing social functioning have been developed and are widely used to measure different aspects of functioning (Weissman et al., 1978; Sheehan, 1983; Ware and Sherbourne, 1992; Ware et al., 1996; Bosc et al., 1997; Weissman et al., 2001; Mundt et al., 2002; Tyrer et al., 2005). The Social Adjustment Scale – Self‐report (SAS‐SR) is among these scales. While it offers assessment of functioning in major roles, its length makes it less useful for epidemiologic studies and other situations where time burden must be minimized, such as with patient screening or as outcome measures. Two abbreviated versions of the scale were thus developed, the SAS‐SR: Short and the SAS‐SR: Screener. The primary goal was to shorten the SAS‐SR to allow for shorter administration time while retaining the original areas of coverage. Both shortened scales were developed in collaboration with staff at MultiHealth Systems, Inc. (MHS) and presented in a technical manual (Weissman and MHS Staff, 2007) that was not peer‐reviewed, indexed, or widely available. While the technical manual encouraged further research with the shortened scales (2007, p. 51), without publication in a scientific journal, this is unlikely to happen. The purpose of this paper is to briefly summarize the development and testing of the shortened versions of the SAS‐SR so that it is more widely available in a peer‐reviewed journal, and to present new data from two samples of convenience which have become available. The purpose is to make this information available so that further independent testing can take place.

Description of the Social Adjustment Scale – Self‐report (SAS‐SR)

The 54‐item SAS‐SR (Weissman et al., 1999, 2001, 1978) is a paper‐and‐pencil self‐report scale of social adjustment intended for use with individuals aged 17 years and older. It was derived directly from the Social Adjustment Scale interview (Weissman and Bothwell, 1976), with wording of the questions changed to suit the self‐report format. The SAS‐SR has been translated into 17 languages and has a fourth grade reading level. The questions were designed to measure expressive and instrumental performance over the past two weeks in six role areas: (1) work, either as a paid worker, unpaid homemaker, or student, (2) social and leisure activities, (3) relationships with extended family, (4) role as a marital partner, (5) parental role, and (6) role within the family unit, including perceptions about economic functioning. The questions within each area cover four expressive and instrumental categories: performance at expected tasks; the amount of friction with people; finer aspects of interpersonal relations; and feelings and satisfactions. Each question is rated on a five‐point scale from which role area means and an overall mean can be obtained, with higher scores denoting greater impairment. Role areas not relevant to the respondent can be skipped. Overall means are based on all items completed by the respondent.

Development of the SAS‐SR: Short and SAS‐SR: Screener

Table 1 gives brief descriptions of the 54 items on the original SAS‐SR and the role areas they cover, as well as the items retained for the Short and Screener versions. Corrected item‐total correlations are also given. The analytic methods used to select the items for the shortened scales are summarized in this section.

Table 1.

SAS‐SR items retained for the SAS‐SR: Short and SAS‐SR: Screener

| Full SAS‐SR role area and item descriptions | Retained for the SAS‐SR: Short | Corrected item‐total correlation (r)a | Retained for the SAS‐SR: Screener | Corrected item‐total correlation (r)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work roleb | ||||

| Feelings of inadequacy | ● | 0.55 | ● | 0.47 |

| Impaired performance | ● | 0.55 | ||

| Time lost | ● | 0.30 | ● | 0.21 |

| (Friction) | ||||

| (Distress) | ||||

| (Disinterest) | ||||

| Social and leisure | ||||

| Loneliness | ● | 0.55 | ● | 0.69 |

| Boredom | ● | 0.48 | ● | 0.54 |

| Diminished contact with friends | ● | 0.29 | ||

| (Diminished social interaction) | ||||

| (Impaired leisure activities) | ||||

| (Diminished romantic relations) | ||||

| (Reticence) | ||||

| (Hypersensitivity) | ||||

| (Friction) | ||||

| (Social discomfort) | ||||

| (Disinterest in romantic relations) | ||||

| Extended family | ||||

| Withdrawal | ● | 0.45 | ● | 0.41 |

| Reticence | ● | 0.41 | ||

| Resentment | ● | 0.37 | ● | 0.56 |

| (Boredom) | ||||

| (Rebellion) | ||||

| (Friction) | ||||

| (Guilt) | ||||

| (Worry) | ||||

| Primary relationship | ||||

| Lack of affection | ● | 0.69 | ||

| Reticence | ● | 0.62 | ● | 0.49 |

| Friction | ● | 0.59 | ||

| (Diminished sexual activity) | ||||

| (Sexual problems) | ||||

| (Dependency) | ||||

| (Submissiveness) | ||||

| (Domineering) | ||||

| (Disinterest in sex) | ||||

| Parental | ||||

| Impaired communication | ● | 0.67 | ||

| Friction | ● | 0.54 | ● | 0.38 |

| Lack of involvement | ● | 0.53 | ||

| (Lack of affection) | ||||

| Family unit | ||||

| Worry | ● | 0.47 | ||

| Guilt | ● | 0.46 | ● | 0.61 |

| Economic inadequacy | ● | 0.35 | ● | 0.35 |

| (Resentment) |

Correlation between the item and the remaining items in that subscale of the full SAS‐SR.

Each of the work role items (six on the SAS‐SR: Full, three on the SAS‐SR: Short, and two on the SAS‐SR: Screener) appears three times on each instrument to accommodate respondents whose primary work is paid employment, housework, or as a student. Accordingly, there are a total of 18 work role items on the full SAS‐SR, nine on the SAS‐SR: Short, and six on the SAS‐SR: Screener.

Development sample

The original development sample used by the MHS staff consisted of 957 adult community respondents (N = 422 males and 535 females aged 18–87 years) from a National Family Opinion (NFO) panel survey testing the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder (Hirschfeld et al., 2003). Participants were selected to be nationally representative according to gender, age, race, income, and geographical region. The 54‐item SAS‐SR was among the scales. Since the SAS‐SR had been included in the NFO study, MHS purchased the data set to carry out the initial development. Selected demographic characteristics of the development sample appear in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the National Family Opinion (NFO) study sample used in the development of the SAS‐SR: Short and SAS‐SR: Screener (N = 957)

| Characteristic | n | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 535 | 55.9 |

| Male | 422 | 44.1 |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 69 | 7.2 |

| 25–34 | 148 | 15.5 |

| 35–44 | 230 | 24.0 |

| 45–54 | 208 | 21.7 |

| 55–64 | 126 | 13.2 |

| 65+ | 176 | 18.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 831 | 86.8 |

| African American | 53 | 5.5 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 11 | 1.2 |

| American Indian or Aleut Eskimo | 8 | 0.8 |

| Other | 18 | 1.9 |

| Missing | 36 | 3.8 |

| Income | ||

| <$20,000 | 207 | 21.6 |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 197 | 20.6 |

| $35,000–$54,999 | 212 | 22.2 |

| $55,000–$84,999 | 178 | 18.6 |

| $85,000+ | 163 | 17.0 |

Note: Reprinted with permission from Weissman and MHS Staff (2007).

SAS‐SR item selection strategy

It was decided that both shortened forms would be developed and evaluated according to standard psychometric criteria but not at the expense of maintaining the theory underlying the original SAS‐SR. A priori decisions included:

All six role areas would be represented. On the Short scale, role areas would be represented equally by retaining three items from each area; on the Screener, two items each would be retained from the work role, social and leisure, extended family, and family unit role areas. Because the primary relationship and parental role areas are potentially less applicable to many respondents, the Screener would retain only one item from each of these role areas.

In order to maintain representation from all four content areas (i.e. performance, interpersonal, friction, and feelings), at least one item from each area would be included on both shortened scales.

To allow the Short and Screener versions to be used for economic assessment like the full SAS‐SR, two items, those assessing how much time was lost from work (work role area) and the adequacy of current financial resources (family unit role area), would be retained regardless of their psychometric properties.

Initial reliability and validity of the shortened scales were assessed with the NFO development sample described earlier.

Item selection for the SAS–SR: Short

For each role area, item analyses were conducted in a stepwise manner. Items with the lowest item‐total correlation (i.e. correlation between the item and the sum of the scores of the remaining scale items) were removed one at a time until the three best items remained. As described earlier, the “Work role: time lost” item was retained for theoretical reasons. All other a priori decisions were upheld psychometrically. After reliability analyses on all six role areas were complete, items from each content area were found to be present on the scale (i.e. six performance, three interpersonal, two friction, and seven feelings items). Cronbach's alpha for the SAS‐SR: Short was 0.88. Alphas for the role area subscales ranged from 0.58 to 0.78, and the corrected item‐total correlations had acceptable values. The standard error of measurement (SEM) of the SAS‐SR: Short was 0.20, i.e. about 95% of the time, a respondent's obtained score is expected to vary ± 0.40 (two standard errors) about his or her true score. The SEM of role area scores on the SAS‐SR: Short ranged from 0.32 to 0.57.

The final set of items on the SAS‐SR: Short was found to have good factorial validity, with substantial evidence for the expected six‐factor structure and a higher‐order model with good fit. The association between SAS‐SR: Short overall scores and full SAS‐SR overall scores was very high (r = 0.93). Together, these findings supported the suitability of using the SAS‐SR: Short overall score as a summary measure of social adjustment.

Item selection for the SAS–SR: Screener

The item pool for the SAS‐SR: Screener was comprised of the final 24 items selected for the SAS‐SR: Short. Within each of the SAS‐SR: Short role areas, items were removed in a stepwise manner according to lowest item‐total correlation. Internal consistency of the resulting 14 items was 0.80. Evidence for the unidimensionality of the final SAS‐SR: Screener was strong, and the association between SAS‐SR: Screener and full SAS‐SR overall mean scores was very high (r = 0.88). Together, these findings supported the suitability of using the SAS‐SR: Screener as a brief measure of social adjustment.

Method

In the current study, our goal is to assess the utility of the SAS‐SR: Short and SAS‐SR: Screener in independent (i.e. non‐development) samples. We used two convenience samples drawn from different populations than the development sample. Except where noted, these analyses are being published here for the first time.

Testing the SAS‐SR: Short and SAS‐SR: Screener

The first sample (henceforth, the Family Study sample) consists of 141 adults from an ongoing longitudinal study of families at high and low risk for depression (Weissman et al., 2006). This sample includes subjects from two generations: (a) 76 adult probands (from 76 unique families), of whom 53 had major depressive disorder (MDD) using Research Diagnostic Criteria, and 23 were members of the community, group‐matched for age and sex, who showed no evidence of psychiatric disorder or treatment during multiple interviews (Weissman et al., 1997), and (b) 65 adult children (from 65 unique families). Measures analyzed here include the full SAS‐SR; the Symptom Checklist‐90 (SCL‐90; Derogatis et al., 1976), a validated self‐report measure of general psychopathology; and the Global Assessment Scale (GAS; Endicott et al., 1976), a validated measure of global functioning rated by a clinical assessor. We used data from multiple waves to enable calculation of person‐level changes on the SAS‐SR and on the SCL‐90 (for 57 parents at waves 1 and 2, two years apart) and the GAS (for 65 adult children at waves 3 and 4, 10 years apart). Age and sex were not associated with any of the above measures in the current analyses therefore we did not adjust for them.

The second sample (henceforth, the Primary Care sample) is comprised of 211 participants in a cross‐sectional survey conducted in an urban primary care clinic serving a largely immigrant population (Olfson et al., 2000). Of 3427 systematically sampled patients, 1264 met eligibility criteria and 1005 participated in Phase 1 (response rate = 80%), which included a demographic questionnaire, diagnostic screening instruments, and an assessment of functioning and treatment utilization. A subset of Phase 1 patients was randomly selected to participate in Phase 2, in which 211 patients (reflecting an 82% response rate; Weissman et al., 2001) were interviewed by trained mental health professionals with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 2.1 (WHO, 1997). They also completed self‐report measures that included the full SAS‐SR and the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF‐36) (Ware and Sherbourne, 1992) (for details, see Gross et al., 2005). Of these 211 patients, 207 had complete data and were included in the present analyses. Many of the subjects were Spanish‐speaking, enabling us to compare results on the English and Spanish versions of the SAS‐SR: Short and SAS‐SR: Screener. Selected characteristics of the family study and primary care samples are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the samples used to validate the SAS‐SR: Short and SAS‐SR: Screener

| Characteristic | Family study sample (N = 141) | Primary care sample (N = 207) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percent | n | Percent | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 86 | 61.0 | 158 | 76.3 |

| Male | 55 | 39.0 | 49 | 23.7 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 | 12 | 8.5 | 11 | 5.2 |

| 30–39 | 39 | 27.7 | 16 | 7.6 |

| 40–49 | 43 | 30.5 | 44 | 20.9 |

| 50–59 | 26 | 18.4 | 57 | 27.0 |

| 60–69 | 20 | 14.2 | 74 | 35.1 |

| 70–71 | 1 | 0.7 | 9 | 4.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | — | — | 144 | 69.6 |

| African American, non‐Hispanic | — | — | 50 | 24.2 |

| White/Other, non‐Hispanic | 141 | 100.0 | 13 | 6.3 |

| Language | ||||

| English | 141 | 100.0 | 85 | 41.1 |

| Spanish | — | — | 122 | 58.9 |

Validity

As an initial look at how well the shortened scales represent the information captured by the full SAS‐SR, we assessed correlations between the shortened scales' overall and role area scores and the full scale's overall and role area scores in each of the two validation samples. These correlations were compared with those found with the development sample.

Convergent validity was assessed by examining correlations between the shortened versions of the SAS‐SR and two measures in the family study sample: SCL‐90 Global Symptom Index scores among parents (self‐reported in waves 1 and 2), and GAS ratings of children (assessed by raters in waves 3 and 4). These measures should correlate highly with the full SAS‐SR, and we assessed the degree to which correlations with the shortened versions of the SAS‐SR were maintained. Correlations were assessed cross‐sectionally at two time points, where the time frame for the SAS‐SR and other clinical assessments were the same (i.e. “current”). We also calculated change scores on all the measures and examined how well changes on the shortened versions of the SAS‐SR correlated with changes on the other clinical measures, as compared to how well changes on the full SAS‐SR correlated with changes in the other measures. Comparable correlations would suggest that the shortened versions of the SAS‐SR are able to capture changes in social functioning as well as the full SAS‐SR.

We also assessed correlations between the shortened SAS‐SR versions and scores on the SF‐36, a measure often used in medical settings to assess quality of life in physical and mental domains (Ware and Sherbourne, 1992). We compared these results to previously published results obtained with the same sample using the full SAS–SR (Weissman et al., 2001).

Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing three groups of subjects in the primary care sample on the shortened versions of the SAS–SR. We examined whether scores on the shortened versions could distinguish patients with current major depression from those with other current psychiatric disorders and those with no current psychiatric disorder as assessed with the CIDI, and we compared these results to those found with the same sample using the full SAS–SR (Weissman et al., 2001). As in the previous study, we expected subjects with major depression to exhibit more social impairment than subjects with other disorders or no disorders.

Our hypothesis throughout is that evidence for the reliability and validity of the SAS–SR will be comparable whether one is considering the full, short, or screener version of the scale.

Results

Intercorrelations between full SAS‐SR and SAS‐SR: Short scores in the primary care and family study samples, respectively, were very similar to those in the development sample (the latter shown in parentheses): Overall score: 0.89 and 0.95 (0.93); work role: 0.87 and 0.86 (0.84); social and leisure role: 0.77 and 0.78 (0.83); extended family role: 0.79 and 0.83 (0.81); primary relationship role: 0.79 and 0.85 (0.84); parental role: 0.98 and 0.97 (0.98); and family unit role: 0.95 and 0.96 (0.97) (Table 4). Intercorrelations between the full SAS‐SR and the SAS‐SR: Screener were 0.81 and 0.89 (0.88).

Table 4.

Correlation of overall and role area scores between the original SAS‐SR and the SAS‐SR: Short and SAS‐SR: Screener in two samples

| Variable | Correlation with SAS‐SR: Full (r, 95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAS‐SR: Full overall score | SAS‐SR: Full role areas | ||||||

| Work (primary) | Social and leisure | Extended family | Primary relationship | Parental | Family unit | ||

| Primary care samplea | |||||||

| Overall scores | |||||||

| SAS‐SR: Short (n = 207) | 0.89 (0.86, 0.91) | 0.63 (0.53, 0.71) | 0.63 (0.54, 0.71) | 0.67 (0.59, 0.74) | 0.73 (0.60, 0.83) | 0.40 (0.21, 0.56) | 0.66 (0.57, 0.73) |

| SAS‐SR: Screener (n = 207) | 0.81 (0.76, 0.85) | 0.63 (0.53, 0.71) | 0.56 (0.46, 0.65) | 0.61 (0.51, 0.69) | 0.66 (0.50, 0.78) | 0.35 (0.16, 0.52) | 0.63 (0.54, 0.71) |

| SAS‐SR: Short role areas | |||||||

| Work (primary) (n = 171) | 0.43 (0.30, 0.54) | 0.87 (0.83, 0.90) | 0.29 (0.15, 0.42) | 0.23 (0.08, 0.37) | 0.34 (0.08, 0.57) | 0.16 (−0.07, 0.37) | 0.29 (0.15, 0.42) |

| Social and leisure (n = 207) | 0.69 (0.61, 0.76) | 0.38 (0.24, 0.50) | 0.77 (0.71, 0.82) | 0.38 (0.26, 0.49) | 0.43 (0.21, 0.61) | 0.21 (0.01, 0.40) | 0.27 (0.14, 0.39) |

| Extended family (n = 200) | 0.54 (0.44, 0.63) | 0.30 (0.15, 0.43) | 0.34 (0.21, 0.46) | 0.79 (0.73, 0.83) | 0.43 (0.20, 0.61) | −0.06 (−0.27, 0.14) | 0.28 (0.15, 0.40) |

| Primary relationship (n = 67) | 0.69 (0.54, 0.80) | 0.42 (0.17, 0.62) | 0.40 (0.18, 0.58) | 0.47 (0.25, 0.64) | 0.79 (0.68, 0.87) | −0.01 (−0.31, 0.28) | 0.37 (0.14, 0.56) |

| Parental (n = 92) | 0.41 (0.23, 0.57) | 0.20 (−0.03, 0.40) | 0.15 (−0.06,0.34) | 0.26 (0.06, 0.45) | 0.16 (−0.14, 0.44) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.34 (0.14, 0.51) |

| Family unit (n = 206) | 0.53 (0.42, 0.62) | 0.26 (0.12, 0.40) | 0.26 (0.13, 0.39) | 0.39 (0.27, 0.50) | 0.21 (−0.03, 0.43) | 0.32 (0.12, 0.49) | 0.95 (0.93, 0.96) |

| Family study sampleb | |||||||

| Overall scores | |||||||

| SAS‐SR: Short (n = 76) | 0.95 (0.91, 0.96) | 0.73 (0.59, 0.83) | 0.76 (0.64, 0.84) | 0.74 (0.62, 0.83) | 0.70 (0.54, 0.81) | 0.55 (0.30, 0.73) | 0.78 (0.68, 0.86) |

| SAS‐SR: Screener (n = 76) | 0.89 (0.84, 0.93) | 0.74 (0.60, 0.83) | 0.69 (0.55, 0.79) | 0.71 (0.58, 0.81) | 0.70 (0.55, 0.81) | 0.43 (0.15, 0.65) | 0.79 (0.69, 0.86) |

| SAS‐SR: Short role areas | |||||||

| Work (primary) (n = 62) | 0.59 (0.40, 0.73) | 0.86 (0.77, 0.91) | 0.45 (0.23, 0.63) | 0.42 (0.19, 0.61) | 0.33 (0.05, 0.55) | 0.14 (−0.19, 0.45) | 0.35 (0.11, 0.55) |

| Social and leisure (n = 76) | 0.69 (0.56, 0.80) | 0.53 (0.32, 0.68) | 0.78 (0.67, 0.85) | 0.36 (0.15, 0.55) | 0.44 (0.21, 0.62) | 0.28 (−0.03, 0.53) | 0.60 (0.43, 0.72) |

| Extended family (n = 75) | 0.59 (0.42, 0.72) | 0.36 (0.13, 0.56) | 0.47 (0.27, 0.63) | 0.83 (0.75, 0.89) | 0.21 (−0.04, 0.44) | 0.05 (−0.26, 0.34) | 0.24 (0.02, 0.45) |

| Primary relationship (n = 63) | 0.65 (0.48, 0.77) | 0.49 (0.24, 0.67) | 0.48 (0.26, 0.65) | 0.29 (0.04, 0.50) | 0.85 (0.76, 0.91) | 0.24 (−0.11, 0.53) | 0.60 (0.42, 0.74) |

| Parental (n = 43) | 0.44 (0.16, 0.65) | 0.03 (−0.29, 0.35) | 0.22 (−0.08, 0.49) | 0.29 (−0.01, 0.54) | 0.21 (−0.14, 0.51) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.42 (0.14, 0.64) |

| Family unit (n = 75) | 0.76 (0.65, 0.84) | 0.60 (0.42, 0.74) | 0.54 (0.36, 0.69) | 0.50 (0.31, 0.66) | 0.58 (0.39, 0.73) | 0.50 (0.23, 0.70) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) |

Note: Pearson r values with confidence intervals not encompassing zero are significant at p < 0.05. Correlations between corresponding full and shortened versions of overall and role area scores appear in italic.

Analysis of 207 primary care patients. The values of n are lower for role areas that did not apply to the respondent.

Analysis of 76 adult probands at wave 1. The values of n are lower for role areas that did not apply to the respondent.

Table 5 shows that two widely used clinical measures generally correlate as strongly with the Short and Screener versions of the SAS‐SR as they do with the full SAS‐SR. SCL‐90 Global Symptom Index scores and GAS scores were significantly related to scores on all three versions of the SAS‐SR at two distinct time points. The magnitude of association between change in the clinical scores and change in SAS‐SR scores was highest when using the SAS‐SR: Screener (absolute r values = 0.49 and 0.41), somewhat lower when using the SAS‐SR: Short (absolute r values = 0.45 and 0.29), and lowest when using the full SAS‐SR (absolute r values = 0.36 and 0.23). While confidence intervals for the three SAS‐SR versions showed great overlap, the trend in these correlations suggests that the items selected for the shorter versions of the SAS‐SR, particularly the Screener, might be particularly sensitive to symptom‐related changes in social adjustment.

Table 5.

Concurrent and longitudinal associations of SAS‐SR: Full, SAS‐SR: Short, and SAS‐SR: Screener scores with global symptoms and rater‐assessed global functioning in the family study sample

| Clinical variable | Correlation, r (95% CI) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall score on the SAS‐SR: Full | Overall score on the SAS‐SR: Short | Overall score on the SAS‐SR: Screener | ||||||||

| T1 | T2 | ∆ | T1 | T2 | ∆ | T1 | T2 | ∆ | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.67 (0.31) | 1.69 (0.34) | 0.02 (0.30) | 1.66 (0.38) | 1.66 (0.40) | −0.00 (0.37) | 1.54 (0.43) | 1.53 (0.46) | −0.01 (0.41) | |

| Via self‐report (n = 57)a | ||||||||||

| SCL‐90 Global Symptom index | ||||||||||

| T1 | 0.39 (0.45) | 0.64 (0.46, 0.77) | — | — | 0.67 (0.49, 0.79) | — | — | 0.67 (0.49, 0.79) | — | — |

| T2 | 0.29 (0.35) | — | 0.76 (0.62, 0.85) | — | — | 0.77 (0.64, 0.86) | — | — | 0.77 (0.63, 0.86) | — |

| ∆ | −0.10 (0.36) | — | — | 0.36 (0.11, 0.57) | — | — | 0.45 (0.22, 0.64) | — | — | 0.49 (0.26, 0.66) |

| Mean (SD) | 1.70 (0.36) | 1.68 (0.31) | −0.02 (0.37) | 1.63 (0.42) | 1.61 (0.34) | −0.02 (0.44) | 1.52 (0.45) | 1.53 (0.38) | 0.01 (0.47) | |

| Via rater assessment (n = 65)b | ||||||||||

| Global assessment Scale (GAS) | ||||||||||

| T1 | 80.15 (11.14) | −0.44 (−0.62, –0.22) | — | — | −0.42 (−0.60, –0.19) | — | — | −0.44 (−0.61, –0.21) | — | — |

| T2 | 81.69 (8.99) | — | −0.45 (−0.62, –0.23) | — | — | −0.43 (−0.61, –0.21) | — | — | −0.44 (−0.62, –0.22) | — |

| ∆ | 1.54 (11.52) | — | — | −0.23 (−0.44, 0.01) | — | — | −0.29 (−0.50, –0.05) | — | — | −0.41 (−0.59, –0.18) |

Note: T1, Time 1; T2, Time 2; ∆, score difference between Time 1 and Time 2.

Analysis of 57 adult probands at waves 1 and 2 (two years apart).

Analysis of 65 adult children of probands at waves 3 and 4 (10 years apart).

Table 6 shows that the patterns of correlations between the SF‐36 summary and subscale scores and the Short and Screener versions of the SAS‐SR are similar to those between SF‐36 scores and the full SAS‐SR. For each SF‐36 subscale, the range of Pearson correlation coefficients among the different SAS‐SR versions was never more than ±0.05. This is further evidence that scores from the shortened scales are an adequate replacement for the full SAS‐SR. Differences in correlations between the English‐ and Spanish‐speaking subjects were very slight (results available upon request).

Table 6.

Intercorrelations of scores on the Short Form 36 health survey (SF‐36) and the Full, Short, and Screener versions of the SAS‐SR in the primary care sample

| Variable | Correlation (r, 95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAS‐SR Overall scores | SF‐36 | ||||

| SAS‐SR (54 items) | SAS‐SR: Short (24 items) | SAS‐SR: Screener(14 items) | Physical component | Mental component | |

| Overall scores | |||||

| Social Adjustment Scale – Self‐report (n = 207) | |||||

| SAS‐SR (54 items) | — | — | — | — | — |

| SAS‐SR: Short (24 items) | 0.89 (0.86, 0.91) | — | — | — | — |

| SAS‐SR: Screener (14 items) | 0.81 (0.76, 0.85) | 0.91 (0.88, 0.93) | — | — | — |

| Short Form health survey (n = 203) | |||||

| Physical component summary score | −0.17 (−0.29, –0.03) | −0.14 (−0.27, –0.001) | −0.15 (−0.28, –0.01) | — | — |

| Mental component summary score | −0.61 (−0.69, –0.52) | −0.62 (−0.77, –0.53) | −0.64 (−0.71, –0.55) | 0.01 (−0.13, 0.15) | — |

| Subscale and role area scores | |||||

| SAS: Short role areasa | |||||

| Work (primary) (n = 167–171) | 0.43 (0.30, 0.54) | 0.59 (0.48, 0.68) | 0.59 (0.48, 0.68) | −0.23 (−0.37, –0.08) | −0.32 (−0.45, –0.18) |

| Social and leisure (n = 203–207) | 0.69 (0.61, 0.76) | 0.70 (0.63, 0.77) | 0.68 (0.60, 0.75) | −0.14 (−0.27, –0.002) | −0.61 (−0.69, –0.51) |

| Extended family (n = 196–200) | 0.54 (0.43, 0.63) | 0.60 (0.50, 0.68) | 0.50 (0.39, 0.60) | 0.02 (−0.12, 0.16) | −0.32 (−0.44, –0.19) |

| Primary relationship (n = 66–67) | 0.69 (0.54, 0.80) | 0.72 (0.58, 0.82) | 0.62 (0.44, 0.75) | 0.17 (−0.08, 0.40) | −0.53 (−0.68, –0.33) |

| Parental (n = 91–92) | 0.41 (0.23, 0.57) | 0.48 (0.30, 0.62) | 0.43 (0.24, 0.58) | −0.01 (−0.22, 0.19) | −0.27 (−0.45, –0.07) |

| Family unit (n = 203–206) | 0.53 (0.42, 0.62) | 0.63 (0.54, 0.71) | 0.59 (0.50, 0.68) | −0.18 (−0.31, –0.04) | −0.32 (−0.44, –0.19) |

| Short Form health survey subscales (n = 203–207) | |||||

| Physical functioning | −0.12 (−0.25, 0.02) | −0.15 (−0.28, –0.01) | −0.15 (−0.28, –0.01) | 0.82 (0.77, 0.86) | 0.19 (0.05, 0.32) |

| Role – physical | −0.15 (−0.28, –0.01) | −0.20 (−0.32, –0.06) | −0.19 (−0.31, –0.05) | 0.72 (0.65, 0.78) | 0.33 (0.20, 0.45) |

| Bodily pain | −0.21 (−0.33, –0.07) | −0.19 (−0.32, –0.05) | −0.19 (−0.32, –0.06) | 0.66 (0.57, 0.73) | 0.20 (0.06, 0.33) |

| General health | −0.20 (−0.33, –0.06) | −0.17 (−0.30, –0.03) | −0.17 (−0.30, –0.03) | 0.56 (0.46, 0.65) | 0.49 (0.38, 0.59) |

| Vitality | −0.27 (−0.39, –0.13) | −0.26 (−0.39, –0.13) | −0.29 (−0.41, –0.16) | 0.39 (0.26, 0.50) | 0.74 (0.67, 0.80) |

| Social functioning | −0.40 (−0.50, –0.27) | −0.41 (−0.52, –0.29) | −0.44 (−0.54, –0.32) | 0.40 (0.30, 0.51) | 0.66 (0.57, 0.73) |

| Role – emotional | −0.32 (−0.43, –0.19) | −0.36 (−0.47, –0.23) | −0.37 (−0.48, –0.25) | 0.13 (−0.01, 0.26) | 0.80 (0.74, 0.84) |

| Mental health | −0.29 (−0.41, –0.16) | −0.28 (−0.41, –0.15) | −0.31 (−0.43, –0.18) | 0.16 (0.03, 0.30) | 0.88 (0.85, 0.91) |

Note: Pearson r values with confidence intervals not encompassing zero are significant at p < 0.05.

The values of n are lower for some role areas because the role area did not apply to the respondent.

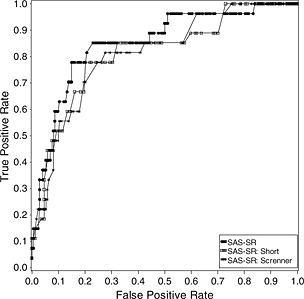

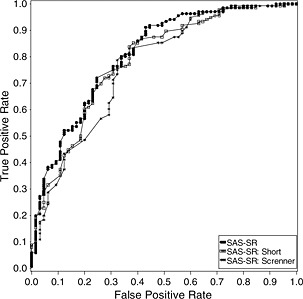

Table 7 replicates our previous findings with the full SAS‐SR, which appear in the top row of the table. The shorter scales differentiated the three groups as well as the full scale. Additionally, the three versions of the scale had similar‐looking receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and acceptably similar areas under the curve (AUC) when scores were used to predict the presence of current MDD (Figure 1) and the presence of any current disorder (Figure 2).

Table 7.

Mean scores on the Full, Short, and Screener versions of the SAS‐SR among patients in the primary care sample with major depressive disorder, other psychiatric disorders, and no psychiatric disorders

| Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Patients with current MDD (n = 27) | Patients with other current psychiatric disorders (n = 38) | Patients with no current psychiatric disorders (n = 136) | Significant post hoc comparisonsa | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Overall scores | |||||||

| SAS‐SR: Full (54 items)b | 2.52 | 0.56 | 2.16 | 0.43 | 1.79 | 0.34 | MDD > Oth, ND; Oth > ND |

| SAS‐SR: Short (24 items) | 2.61 | 0.78 | 2.18 | 0.58 | 1.72 | 0.46 | MDD > Oth, ND; Oth > ND |

| SAS‐SR: Screener (14 items) | 2.58 | 0.84 | 2.07 | 0.68 | 1.58 | 0.47 | MDD > Oth, ND; Oth > ND |

Note: SD, standard deviation; MDD, current major depressive disorder; Oth, other current psychiatric disorders; ND, no current psychiatric disorders.

The post hoc multiple comparisons used Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference test (p < 0.05) and were run only when the omnibus test was significant (p < 0.05). All tests are adjusted for age and gender.

This row of data is from Weissman et al. (2001).

Figure 1.

ROC curves for the Full, Short, and Screener versions of the SAS‐SR predicting current major depressive disorder (MDD) in 201 primary care patients. Note: AUC = 0.851 (SAS‐SR: Full), 0.813 (SAS‐SR: Short), and 0.812 (SAS‐SR: Screener).

Figure 2.

ROC curves for the Full, Short, and Screener versions of the SAS‐SR predicting presence of any current mental disorder in 201 primary care patients. Note: AUC = 0.810 (SAS‐SR: Full), 0.785 (SAS‐SR: Short), and 0.763 (SAS‐SR: Screener).

Discussion

The 54‐item SAS‐SR has utility as a measure of social adjustment in research and clinical practice, however it is relatively long to administer. In this paper, we tested two recently developed and available shortened versions of the SAS‐SR to see if they operated comparably to the full scale. Like the full SAS‐SR, the 24‐item SAS‐SR: Short provides a score for overall social adjustment as well as subscale scores representing each of the original six role areas. The 14‐item SAS‐SR: Screener provides an overall score of social adjustment but does not include role area scores. Both shortened versions contain items from each of the six role areas and all four content categories (i.e. performance, interpersonal, friction, and feelings). The Short takes about 10 minutes to complete and the Screener takes about five minutes.

We found that the shortened versions of the SAS‐SR performed well in comparison to the full scale. Our findings suggest that the shortened scales capture a large proportion of the information captured by the full scale. In our two samples of convenience, correlations with the full SAS‐SR were high for both the Short (r values = 0.89 and 0.95) and Screener (r values = 0.81 and 0.89) versions, and their magnitudes were similar to those found in the development sample (Full ~ Short: r = 0.93; Full ~ Screener: r = 0.88).

We found that SAS‐SR overall scores were significantly associated with self‐report and rater‐assessed measures of psychopathology (the SCL‐90 and GAS) and with a widely used measure of health‐related quality of life (SF‐36). Our findings indicate that these associations are generally as large, and sometimes larger, when using overall scores on either of the shortened versions of the SAS‐SR. The shortened versions were also able to distinguish various clinical groups as efficiently as the full SAS‐SR, suggesting that the shortened scales can be used in place of the full scale when details of role performance are not needed.

There are several well‐tested brief self‐report scales available to measure an individual's current social functioning. These include, in addition to the SAS‐SR: Screener and SAS: Short, the SF‐12, the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), the Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ), and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) (Table 8). These scales generally take less than 10 minutes to complete and are thus candidates for inclusion in clinical trials and other contexts where administration time is limited. The choice of scale depends in part on available time resources and determination of the domains most important to assess, as shown in Table 8. The scales differ in number of items (from 3 to 24) and whether items are phrased such that impairment must be due to a specific disorder (WSAS), physical health (SF‐12), or emotional problems (SF‐12, SDS), or items are not explicitly attributed to a particular cause (SFQ, SAS‐SR: Screener, SAS: Short). The SF‐12 is the only scale that assesses general health or physical limitations, the SDS is the shortest of the scales, and both shortened versions of the SAS‐SR are the only scales to assess functioning in the parental role and work functioning in multiple areas, and to include at least one item from each of the six role areas and each of the four content categories from the full SAS‐SR.

Table 8.

Selected brief self‐report scales for assessing social adjustment/impairment

| Scale name | Number of items | Time frame | Areas assessed | Attribution of impairment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Adjustment Scale – Self‐report (SAS‐SR): Screener | 14a | Past two weeks | Work (for pay; housework; student) | —b |

| Social and leisure | ||||

| Family outside the home | ||||

| Primary relationship | ||||

| Parental | ||||

| Family unit | ||||

| Social Adjustment Scale – Self‐report (SAS‐SR): Short | 24a | Past two weeks | Work (for pay; housework; student) | —b |

| Social and leisure | ||||

| Family outside the home | ||||

| Primary relationship | ||||

| Parental | ||||

| Family unit | ||||

| MOS Short Form‐12 (SF‐12) | 12 | Past four weeks | General health | “Physical health” |

| Physical limitations | “Emotional problems” | |||

| Work or other regular daily activities | ||||

| Social activities | ||||

| Bodily pain | ||||

| Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) | 3 | —c | Work/school | “Emotional problems” |

| Social life | ||||

| Family life/home responsibilities | ||||

| Social Functioning Questionnaire (SFQ) | 8 | Past two weeks | Work | —b |

| Tasks at home | ||||

| Money problems | ||||

| Close relationships | ||||

| Sex life | ||||

| Family | ||||

| Loneliness | ||||

| Spare time | ||||

| Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) | 5 | —c | Work | Specific (identified) disorder |

| Home management | ||||

| Social leisure activities | ||||

| Private leisure activities | ||||

| Close relationships |

Actual number of items completed may be fewer if certain role areas do not apply to the respondent.

No explicit attribution.

No specific time frame given; “current” is implied.

Limitations of this study include: (1) respondents in the convenience samples completed all 54 items; the shortened scales were “embedded” and a more accurate test would be to administer just the shorter list of items, and (2) the shorter versions need to be tested with a broader range of respondents (e.g. different nationalities and languages).

In summary, the full SAS‐SR might be used when maximum detail about functioning in various role areas is desired and when respondent burden is not a major concern. In clinical contexts, examination of specific responses may aid in the interpretation of scale scores and help to identify specific areas in need of remediation. The SAS‐SR: Short may be useful in situations where time does not permit the administration of the full SAS‐SR but information on the respondent's level of adjustment in each role area is desired. The SAS‐SR: Screener may be useful in situations where the respondent's overall level of social adjustment requires a brief assessment, such as when time is scarce or the SAS‐SR is included in a repeated battery of tests.

Declaration of interest statement

Over the last two years, Dr Gameroff received research funding from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD); Dr Wickramaratne received research funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); and Dr Weissman received research funding from NIMH, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), NARSAD, the Sackler Institute for Developmental Psychobiology, the Interstitial Cystitis Foundation, and the Templeton Foundation; received book royalties from the Oxford University Press, Perseus Press, and the American Psychiatric Association Press; and received royalties from MultiHealth Systems, Inc., for all versions of the Social Adjustment Scale – Self‐report.

Acknowledgments

Data from the Family Study sample came from R01MH 036197 from the National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, Maryland. Data from the Primary Care sample came from an investigator‐initiated grant from Eli Lilly & Co. that ended in 2003. The development of the Short and Screener versions of the SAS‐SR was funded in part by MultiHealth Systems, Inc., who own the copyright.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed. Text Revision). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton J.M., Robinson J., Sareen J. (2009) Self‐medication of mood disorders with alcohol and drugs in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 115, 367–375, DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosc M., Dubini A., Polin V. (1997) Development and validation of a social functioning scale, the Social Adaptation Self‐evaluation Scale. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 7(Suppl. 1), S57–S70, DOI: 10.1016/S0924-977X(97)00420-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L.R., Rickels K., Rock A.F. (1976) The SCL‐90 and the MMPI: a step in the validation of a new self‐report scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 128, 280–289, DOI: 10.1192/bjp.128.3.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J., Spitzer R.L., Fleiss J.L., Cohen J. (1976) The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry, 33, 766–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg P.E., Stiglin L.E., Finkelstein S.N., Berndt E.R. (1993). The economic burden of depression in 1990. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 54, 405–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross R., Olfson M., Gameroff M.J., Shea S., Feder A., Lantigua R., Fuentes M., Weissman M.M. (2005) Social anxiety disorder in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry, 27, 161–168, DOI: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld R.M., Calabrese J.R., Weissman M.M., Reed M., Davies M.A., Frye M.A., Keck P.E. Jr, Lewis L., McElroy S.L., McNulty J.P., Wagner K.D. (2003) Screening for bipolar disorder in the community. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 53–59, DOI: 10.4088/JCP.v64n0111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Koretz D., Merikangas K.R., Rush A.J., Walters E.E., Wang P.S. (2003) The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS‐R). Journal of the American Medical Association, 289, 3095–3105, DOI: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman G., Weissman M.M. (1992) The course, morbidity, and costs of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49, 831–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz J., Mintz L.I., Arruda M.J., Hwang S.S. (1992) Treatments of depression and the functional capacity to work. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49, 7761–7768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt J.C., Marks I.M., Shear M.K., Greist J.H. (2002) The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 461–464, DOI: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C.J.L., Lopez A.D. (1996) Global Health Statistics: A Compendium of Incidence, Prevalence and Mortality Estimates for over 200 Conditions, Cambridge, Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M., Shea S., Feder A., Fuentes M., Nomura Y., Gameroff M., Weissman M.M. (2000) Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders in an urban general medicine practice. Archives of Family Medicine, 9, 876–883, DOI: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytsala H.J., Melartin T.K., Leskela U.S., Lestela‐Mielonen P.S., Sokero T.P., Isometsa E.T. (2006) Determinants of functional disability and social adjustment in major depressive disorder: a prospective study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194, 570–576, DOI: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000230394.21345.c4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V. (1983) The Anxiety Disease, New York, Scribner Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer P., Nur U., Crawford M., Karlsen S., McLean C., Rao B., Johnson T. (2005) The Social Functioning Questionnaire: a rapid and robust measure of perceived functioning. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 51, 265–275, DOI: 10.1177/0020764005057391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Üstün T.B. (1999) Global burden of mental disease. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1315–1318, DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustün B., Kennedy C. (2009) What is “functional impairment”? Disentangling disability from clinical significance. World Psychiatry, 8, 82–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J.E., Jr , Sherbourne C.D. (1992) The MOS 36‐item Short‐Form health survey (SF‐36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30, 473–483, DOI: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J., Jr , Kosinski M., Keller S.D. (1996) A 12‐item Short‐Form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care, 34, 220–233, DOI: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M.M., Bothwell S. (1976) Assessment of social adjustment by patient self‐report. Archives of General Psychiatry, 33, 1111–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M., MHS Staff . (1999) Social Adjustment Scale – Self‐report (SAS‐SR) User's Manual, North Tonawanda, NY, Multi‐Health Systems, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M., MHS Staff . (2007) Social Adjustment Scale – Self‐report: Short (SAS‐SR: Short) & Social Adjustment Scale – Self‐report: Screener (SAS‐SR: Screener) Technical Manual, North Tonawanda, NY, Multi‐Health Systems, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M.M., Olfson M., Gameroff M.J., Feder A., Fuentes M. (2001) A comparison of three scales for assessing social functioning in primary care. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 460–466, DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M.M., Prusoff B.A., Thompson W.D., Harding P.S., Myers J.K. (1978) Social adjustment by self‐report in a community sample and in psychiatric outpatients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 166, 317–326, DOI: 10.1097/00005053-197805000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M.M., Warner V., Wickramaratne P., Moreau D., Olfson M. (1997) Offspring of depressed parents: 10 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 932–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman M.M., Wickramaratne P., Nomura Y., Warner V., Pilowsky D., Verdeli H. (2006) Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 1001–1008, DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D.R., Gonzalez H.M., Neighbors H., Nesse R., Abelson J.M., Sweetman J., Jackson J.S. (2007) Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non‐Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 305–315, DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H.U., Carter R.M., Pfister H., Montgomery S.A., Kessler R.C. (2000) Disabilities and quality of life in pure and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and major depression in a national survey. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 15, 319–328, DOI: 10.1097/00004850-200015060-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) . (1997) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): Version 2.1, Geneva, WHO. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) . (2001) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), Geneva, WHO. [Google Scholar]