Abstract

Binge eating disorder (BED) is the most prevalent eating disorder in adults, and individuals with BED report greater general and specific psychopathology than non-eating disordered individuals. The current paper reviews research on psychological treatments for BED, including the rationale and empirical support for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), behavioral weight loss (BWL), and other treatments warranting further study. Research supports the effectiveness of CBT and IPT for the treatment of BED, particularly for those with higher eating disorder and general psychopathology. Guided self-help CBT has shown efficacy for BED without additional pathology. DBT has shown some promise as a treatment for BED, but requires further study to determine its long-term efficacy. Predictors and moderators of treatment response, such as weight and shape concerns, are highlighted and a stepped-care model proposed. Future directions include expanding the adoption of efficacious treatments in clinical practice, testing adapted treatments in diverse samples (e.g., minorities and youth), improving treatment outcomes for nonresponders, and developing efficient and cost-effective stepped-care models.

Keywords: Binge eating disorder, Eating disorders, Loss of control, Psychological treatments, Treatment review, Randomized controlled trials, Cognitive behavioral therapy, Guided self-help, Interpersonal psychotherapy, Behavioral weight loss, Dialectical behavior therapy

Introduction

Binge eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent binge eating (i.e., eating an unusually large amount of food accompanied by a sense of loss of control) in the absence of significant compensatory behaviors (e.g., self-induced vomiting, excessive exercise). BED affects 3.5% of women and 2.0% of men in the USA [1], and is similarly prevalent across racial/ethnic groups [2–4]. Although children and adolescents are less likely than adults to meet the criteria for BED, related behaviors such as loss of control eating (i.e., the experience of loss of control over eating regardless of the amount of food consumed) are prevalent [5–7].

Binge eating disorder is associated with significant morbidity, including medical complications related to obesity (e.g., type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease), eating disorder psychopathology (e.g., weight and shape concerns), psychiatric co-morbidity, reduced quality of life, and impaired social functioning [8]. The clinical significance of BED has been well established [9, 10], and its diagnosis has been suggested for inclusion in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (www.dsm5.org).

Although BED is associated with significant impairment, prognosis is good with appropriate therapeutic intervention. Treatments for BED target binge eating, associated eating disorder psychopathology, and the prevention of excess weight gain or modest weight loss. The present paper will review randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychological treatments for BED in order to inform current clinical practice and future research. The rationale and empirical evidence for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), behavioral weight loss treatment (BWL), and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), as well as promising alternative treatments, will be presented (see Table 1). Predictors and moderators of treatment outcome, which may aid in developing and delivering more effective and efficient treatments, will also be reviewed.

Table 1.

Overview of the psychological treatments for binge eating disorder (BED)

| Treatment | Theoretical approach | Treatment targets | Empirical support for BED |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral weight loss (BWL) | Promote weight loss by decreasing energy intake and increasing energy expenditure | Making gradual lifestyle changes in diet, exercise, and eating habits | No strong empirical support for BWL over specialist treatments for BED on either weight loss or eating pathology outcomes |

| Self-monitoring of food intake, exercise, and thoughts about food | Specialized treatments are more effective than BWL in the long term | ||

| Weight loss goal of one pound per week | BWL may be an effective weight loss option for responders to CBT or IPT | ||

| Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) | Disturbed eating patterns and problematic thoughts/beliefs related to eating, shape, and weight contribute to binge eating | Address chaotic eating patterns (e.g., encourage regular meals) | Strong empirical support for therapist-led CBT in short- and long-term outcomes |

| Change dysfunctional thoughts about the self and the importance of weight and shape | Self-help CBT may represent a worthwhile first-line treatment; however it is not recommended for patients with low self-esteem and/or high shape and weight concerns. Retention also remains a challenge. | ||

| Encourage healthy weight-control behaviors (e.g., self-monitoring and exercise) | |||

| Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) | Interpersonal stressors contribute to using binge eating as a way to cope with negative affect | Target social deficits and promote mastery in interpersonal domains | Strong evidence demonstrating a short- and long-term reduction in binge eating, comparable to results found in CBT |

| Address problems in four primary areas: interpersonal deficits, interpersonal role disputes, role transitions, and grief | |||

| Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) | Difficulty regulating affect leads to pathological or maladaptive behaviors, such as binge eating | Teach healthier ways to modulate negative emotional arousal | Preliminary research shows promising results for binge abstinence. |

| Achieve proficiency in four domains: mindfulness skills, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness | More research must be conducted to examine its long-term efficacy and success compared with other specialist treatments |

While pharmacological treatments for BED have received much attention in recent years [11], the current review focuses on RCTs of psychological treatments delivered alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy (see Table 2), given evidence that pharmacological treatments are not as efficacious as psychological treatments [12]. A recent meta-analysis of psychological and pharmacological treatments for BED found that psychotherapy and structured self-help treatments had more robust effects on outcomes, including binge abstinence [12]. Finally, the long-term efficacy of pharmacological treatments is largely unknown, owing to a lack of follow-up research [11].

Table 2.

Selected randomized controlled trials of treatments for BED

| Study | Treatment conditions | n | Male (%) |

Caucasian (%) |

Attrition rate (%) |

Dose | Post-treatment outcome (% abstinent) |

Follow-up outcome (% abstinent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [13] | a) CBT | 23 | 0 | 91 | 17 | 10 sessions (10 weeks) | a) 79* | a) 46% remained abstinent |

| b) Wait-list control | 21 | 0 | b) 0 | |||||

| [20] | a) CBT | 18 | 0 | 86 | 33 | 16 sessions (16 weeks) | a) 28* | NR |

| b) IPT | 18 | 11 | b) 44* | |||||

| c) Wait-list control | 20 | c) 0 | ||||||

| [22] | a) BWLT | 37 | 0 | NR | 27 | 30 sessions (36 weeks) | a) 19 | a) 14 |

| b) BWLT + CBT | 36 | 17 | b) 37 | b) 28 | ||||

| c) BWLT + CBT + desipramine | 36 | 23 | c) 41 | c) 32 (3 month) | ||||

| [105] | a) CBT | 39 | 14 | NR | 14 | 12 sessions (12 weeks) | a) 55* | (see [15]) |

| b) Wait-list control | 11 | 9 | b) 9 | |||||

| [15] | a) BWLT + CBT | 93 | 0 | 92 | 18 | 30 sessions (36 weeks) | a) 33 | NR |

| 1-year follow-up data from [17,22, 105] | ||||||||

| [33] | a) Guided self-help CBT | 24 | 0 | 97 | 33 | Self directed (12 weeks) | a) 50* | a) 41, 50 |

| b) Unguided self-help CBT | 24 | 0 | b) 43* | b) 37, 40 | ||||

| c) Wait-list control | 24 | 4 (12% overall) | c) 8 | (3, 6 months) | ||||

| [35,36] | a) Therapist-led CBT | 16 | 0 | 97 | 12 | 14 sessions (8 weeks) | a) 69* | a) 55, 56, 67 |

| b) Partial self-help CBT | 19 | 10 | b) 68* | b) 69, 70, 85 | ||||

| c) Structured self-help CBT | 15 | 27 | c) 87* | c) 64, 75, 75 (1, 6, 12 months) | ||||

| d) Wait-list control | 11 | 18 | d) 13 | |||||

| [106] | a) CBTgsh | 40 (82.5% BED) | 0 | 95 | 3 | a) 6 sessions (10 weeks) | a) 68* | NR |

| b) CBT unguided self-help | 3 | b) 10 weeks | b) 55 | |||||

| [68] | a) Cognitive therapy | 37 | 0 | NR | 14 | 15 sessions (15 weeks) | a) 67 | a) 86* |

| b) Behavioral therapy | 37 BED = 37 | b) 44 | b) 44 (6 months) | |||||

| [29] | a) CBT | 81 | 17 | 94 | 11 | 20 sessions (20 weeks) | a) 79 | a) 59 |

| b) IPT | 81 | 17 | 91 | 9 | b) 73 | b) 62 (12 months) | ||

| [25] | a) CBTgsh | 37 | 21 | 77 | 13 | Self directed (12 weeks) | a) 46* | No follow-up |

| b) BWLTgsh | 38 | 33 | b) 18 | |||||

| c) Wait-list control | 15 | 13 | c) 13 | |||||

| [25] | a) CBTgsh + orlistat | 25 | 12 | 88 | 24 | 6 brief individual sessions (12 weeks) | a) 64* | a) 52 |

| b) CBTgsh + placebo | 25 | 20 | b) 36 | b) 52 (3 month) | ||||

| [25] | a) CBT + fluoxetine | 26 | 23 | 89 | 23 | 16 sessions (16 weeks) | a) 50* | No follow-up |

| b) CBT + placebo | 28 | 21 | 93 | 21 | b) 61* | |||

| c) Fluoxetine | 27 | 30 | 100 | 22 | c) 22 | |||

| d) Placebo | 27 (108) | 15 (22) | 74 (89) | 15 (20) | d) 26 | |||

| [23,24] | a) BWLT + CBT + fluoxetine | 28 | 22 | 77 | 32 | 16 sessions (BWLT) | a&b) 62* (CBT) | 68, 61, 70, 74 (6, 12, 18, 24 months) |

| b) BWLT + CBT + placebo | 25 | 20 sessions (CBT) | c&d) 33 (BWLT) | CBT>BWL (24 months) | ||||

| c) BWLT + fluoxetine | 32 | (5 months) | ||||||

| d) BWLT + placebo | 31 | |||||||

| [48] | a) Group CBT | 47 | 9 | 98 | 21 | 16 sessions (16 weeks) | a) 62* | a) 65, 68 |

| b) Group psychodynamic IPT | 48 | 23 | b) 60* | b) 62, 57 (12 months) | ||||

| c) Wait-list control | 40 | 18 | c) 9 | |||||

| [31] | a) Group CBT + topiramate | 37 | 3 | 62 | 19 | 19 sessions (21 weeks) | a) 84* | No follow-up |

| b) Group CBT + placebo | 36 | 6 | 53 | 28 | b) 61 | |||

| [16] | a) CBT | 30 | 6 | NR | 7 | 15 sessions (20 weeks) | a) 63* | a & b) 80 (groups analyzed together) (12 month) |

| b) Wait-list control | 22 | 0 | b) 18 | |||||

| [37] | a) CBT | 44 | 9 | NR | 30 | 16 sessions (16 weeks) + 6 monthly follow-up sessions | a) 41 | a) 52 |

| b) BWLT | 36 | 14 | 25 | b) 58* | b) 50 (12 month) | |||

| [107] | a) Group CBT | 22 | 9 | 68 | 32 | 10 sessions (10 weeks) | a) 8 | a) 22 |

| b) CD-ROM CBT | 22 | 9 | 64 | 41 | 10 weeks | b) 13 | b) 13 (2 months) | |

| c) Wait-list control | 22 | 5 | 77 | 9 | ||||

| [108] | a) Adapted motivational interviewing (AMI) | 54 | 0 | 89 | 11 | 1 AMI session + self-Help handbook | a) 28* | NR |

| b) Control | 54 | 15 | Self-help handbook | b) 11% | ||||

| [25] | a) CBT + booster session | 18 | 0 | NR | 6 | 8 sessions (8 weeks) + 5 booster sessions during follow-up | a) 11* | a & b) 41, 23, 25 (3, 6, 12 months) |

| b) Wait-list control | 18 | 0 | b) 0 | |||||

| [109] | a) Psychoeducational treatment (PET) | 13 | 0 | 91 | 8 | 11 sessions (12 weeks) a and | b) 78 (groups analyzed together) | a and b) 87 (12 months) |

| b) Wait-list control | 27 | 59 | ||||||

| [57] | a) DBT-BED | 50 | 14 | 80 | 4 | 20 sessions (21 weeks) | a) 64 | a) 64 |

| b) Active comparison group therapy (ACGT) | 51 | 16 | 73 | 33 | b) 33 | b) 49 (12 months) | ||

| [37] | a) CBT-GSH | 59 | 8 | 98 | 12 | a) 8 sessions (12 weeks) | a) 64* | a) 75*, 64* |

| b) Treatment as usual (control) | 64 (48% BED) | 95 | 6 | b) 28 | b) 44, 45 (26, 52 weeks) | |||

| [39] | a) CBTgsh | 66 | 18 | 82 | 30 | 10 sessions | a) 62 | a) 59, 62 |

| b) IPT | 75 | 15 | 77 | 7 | 20 sessions | b) 67 | b) 55, 64 | |

| c) BWLT | 64 | 11 | 88 | 28 | 20 sessions (24 weeks) | c) 64 | c) 50, 47 (12, 24 months) | |

| [41] | a) CBTgsh (internet-based) | 37 | 0 | NR | 24 | Self directed (6 months) | a) 35* | a) 43 |

| b) Wait-list control | 37 | 11 | b) 8 | b) NR (6 months) | ||||

| [26] | a) CBT | 45 | 36 | 76 | 24 | a & b)16 sessions (24 weeks) | a) 44 | a) 51, 51 |

| b) BWLT | 45 | 38 | 80 | 31 | c) 16 sessions (16 weeks—CBT); 16 sessions (24 weeks—BWLT) | b) 38 | b) 33, 36 | |

| c) CBT followed by BWLT | 35 | 20 | 74 | 40 | c) 49 | c) 49, 40 (6, 12 months) | ||

| [110] | a) CBT + diet | 25 | 24 | 80 | 20 | 21 sessions (6 months) | a) 60 | NR |

| b) CBT + nutritional counseling | 25 | 8 | b) 72 |

Significant difference

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Rationale

The rationale for modifying CBT for BED is based on the restraint model of binge eating. This model posits that problematic eating patterns and concerns about shape and weight result in extreme restriction [13, 14]. This promotes a dysfunctional pattern of over- and under-restriction, in which patients alternate between dietary restraint and binge eating. The goal of CBT is to disrupt this “diet-binge cycle” by promoting healthier, more structured eating patterns (e.g., regular meals and snacks), improving shape and weight concerns, and encouraging the use of healthy weight-control behaviors (e.g., engaging in flexible dietary restraint). CBT encourages patients to normalize eating patterns by setting goals and using self-monitoring to develop flexible restraint and modify negative views of themselves in order to reduce binge eating.

Empirical Evidence

Cognitive behavioral therapy is the most studied and well-established psychological treatment for BED [14]. Overall, research has shown that individual and group formats of CBT are associated with significantly higher abstinence rates compared with no treatment [13, 15–20], supportive therapy [21], and BWL [22–25, 26•, 27], with individual and group therapy formats producing similar long-term results [28].

The largest RCT to date to evaluate the efficacy of CBT for BED was conducted by Wilfley and colleagues [29] and compared group formats of CBT and IPT [29]. After 20 sessions of either CBT or IPT, 79% and 73% of participants respectively, were abstinent from binge eating, and 59% and 62% were abstinent at 1-year follow-up [29]. Further, an examination of long-term follow-up data showed that improvements were well maintained over 4 years [30•]. Studies that followed have provided further support for the effectiveness of CBT for BED.

A study comparing 15 sessions of CBT (63% abstinence) to a wait-list control (18% abstinence) demonstrated the superiority of CBT over no treatment [16]. At 1-year follow-up, 80% of the sample (including wait-list controls who had received CBT), were abstinent [16]. Additionally, Munsch and colleagues [27] found that CBT produced superior abstinence rates to BWL (i.e., 80% vs. 36% respectively, based on completer analyses) [27], and at 1-year follow-up, CBT was associated with significantly fewer binge days than BWL [27].

Studies have also examined the efficacy of CBT combined with pharmacological treatments. Grilo and colleagues [25] compared CBT plus placebo or fluoxetine with placebo or fluoxetine alone, and found that CBT conditions were associated with higher abstinence rates as compared with medication-only, suggesting that the addition of fluoxetine to CBT does not confer any additional benefit in terms of reducing binge eating [25]. Conversely, the addition of 200 mg of topiramate to CBT produced significantly larger abstinence rates (84% abstinence) compared with CBT plus placebo (61% abstinence); however, no follow-up was conducted [31]. Thus, it remains unclear as to which pharmacological agents, if any, may enhance the long-term effectiveness of CBT.

Guided Self-Help CBT

Guided self-help CBT (CBTgsh) addresses the need for more widely disseminable therapies for BED. Such treatments are low cost and require minimal specialist care. The majority of CBTgsh treatments provide participants with the self-help manual Overcoming Binge Eating by Christopher Fairburn [32], as well as regular brief meetings with a therapist. Like traditional CBT, guided self-help targets binge eating by promoting regular eating patterns and moderate dietary restraint through self-monitoring and problem-solving strategies. The therapist’s role is to encourage adherence, aid in goal development, and provide the rationale for CBTgsh. Studies have shown that CBTgsh produces superior outcomes compared with a wait-list control, treatment as usual, and guided self-help BWL [25, 33–36, 37•], and produces similar outcomes to IPT [39•] for individuals with low levels of additional pathology. It produces consistent reductions in binge eating and associated psychopathology at post-treatment and long term follow up [38].

In a primary care setting, Striegel-Moore and colleagues [37•] compared eight sessions of CBTgsh, which included an additional module targeting body checking and avoidance, to treatment as usual (TAU) [37•]. Post-treatment CBTgsh was associated with superior abstinence rates (64%) as compared with TAU (45%) [37•]. Attrition rates in this study were typical of those reported in others [25, 33]. In another large study, Wilson and colleagues [39•] found that CBTgsh and IPT were associated with similar abstinence rates (65% and 67%), and with significantly larger abstinence rates than BWL (47%) 2 years following treatment [39•]. However, CBTgsh was associated with significantly larger attrition rates than IPT and was rated by participants as being less acceptable before the start of treatment [39•]. Furthermore, CBTgsh was less effective than IPT for individuals with higher baseline binge eating frequency or lower self-esteem plus higher eating disorder psychopathology [39•].

Additionally, a study comparing CBT formats requiring varying levels of therapist involvement found that, post-treatment, therapist-led and therapist-assisted (i.e., video-delivered psychoeducation followed by therapist-led discussion and homework review) CBT formats were more effective than a self-help group with no therapist involvement. However, by 12-month follow-up, the three groups produced similar abstinence rates, suggesting that laypersons delivering CBT in a group format may be as effective as therapist-led group CBT [34]. Importantly, however, 12-month abstinence rates reported in this study were quite low (around 20%) [34].

Recent studies have also examined CBTgsh delivered through scalable technologies, including the internet, but understanding of their long-term efficacy is limited. Two studies of web-based CBTgsh have shown them to be associated with significantly larger abstinence rates than a wait-list control [40]. Abstinence rates in these studies were sustained at 6 months, but neither compared CBTgsh with a control group at follow-up [40, 41]. Thus, it is clear that further research is warranted to elucidate the long-term effectiveness of CBTgsh delivered through scalable technologies that may be particularly attractive to adolescents and young adults.

Overall, research suggests that CBTgsh is an effective treatment for BED, particularly compared with no treatment. However, few studies have compared CBTgsh with active treatments [42]. Notably, CBTgsh is associated with higher attrition than specialist treatments (e.g., IPT and CBT) and appears to be less effective for individuals with a more severe pre-treatment eating disorder and general psychopathology [39•, 43]. Thus, CBTgsh may be an appropriate treatment for individuals with BED that is uncomplicated by additional pathology (e.g., high negative affect, weight and shape concerns). Furthermore, the level of training required by a CBTgsh “therapist” is not clear and should be studied further. It may be that laypersons may provide guidance just as effectively as trained therapists for a subset of individuals.

Interpersonal Psychotherapy

Rationale

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) has been applied to the treatment of BED based on a strong body of evidence demonstrating a consistent relationship between poor interpersonal functioning and eating disorders [44, 45]. The interpersonal model of binge eating posits that social problems create an environment in which binge eating develops and is maintained as a coping mechanism, serving to reduce negative affect in response to unfulfilling social interactions [46]. Binge eating may, in turn, worsen interpersonal problems by increasing social isolation and impeding on fulfilling relationships, thereby maintaining the eating disorder [46]. People with BED often present with suppressed affect; so, instead of expressing negative affect, they eat to cope. IPT helps individuals acknowledge and express this painful affect so that they can better manage negative feelings without turning to food. IPT also seeks to reduce binge eating pathology by supporting the development of healthy interpersonal skills that can replace maladaptive behaviors and promote a positive self-image [47].

Empirical Support

Interpersonal psychotherapy is the only treatment that has shown comparable long-term outcomes to CBT. As discussed earlier, Wilfley and colleagues [29] compared CBT with IPT and found equivalent abstinence rates post-treatment, and at the 1-year and 5-year follow-ups [29, 30•]. Further, IPT was shown to be more effective than BWL two years following treatment [39•]. Psychodynamic IPT, similar to IPT but with an additional focus on reducing cyclical relational patterns and negative internalizations, was found to perform comparably to CBT both post-treatment and at 12-month follow-up [48]. IPT has also been applied to the treatment of loss of control eating in adolescents, and has demonstrated greater efficacy than a standard-of-care health education program [49].

Importantly, IPT demonstrates a number of advantages relative to CBT-based treatments, such that patients rate IPT as more acceptable and report greater expectations of success [39•, 50, 51]. IPT may also be more effective for racial/ethnic minority patients, including African–Americans, who were less likely to drop out of IPT than CBTgsh and BWL in one study [39•]. Finally, IPT has shown greater efficacy for patients with more severe eating pathology and lower self-esteem [39•], and thus may be a more appropriate first-line treatment for such individuals.

Behavioral Weight Loss Treatment

Rationale

The majority of individuals with BED struggle with overweight and obesity and have a higher average body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) than their non-BED overweight and obese counterparts [52]. Thus, BWL, the most commonly implemented treatment for adult obesity, has been examined as a potential treatment for BED. BWL focuses on weight loss through moderate reductions in caloric intake and increased physical activity, rather than targeting binge eating directly. It is hypothesized that the improved eating and activity patterns promoted in BWL will result in less binge eating and successful weight loss.

Empirical Evidence

Research shows that BWL is not as effective as specialist treatments for BED in reducing binge eating. Notably, a recent meta-analysis found that BWL only inconsistently produced reductions in binge eating [53]. A study that compared guided self-help formats of BWL and CBT found that CBTgsh was associated with significantly higher abstinence rates than BWLgsh and a wait-list control (46%, 18%, and 13% respectively) [25]. As described above, both IPT and CBTgsh were shown to produce superior binge abstinence rates compared with BWL 2 years following treatment [39•]. Another study found that compared with BWL, CBT produced superior post-treatment abstinence rates and 12-month follow-up reductions in binge eating [27]. Researchers have also examined the efficacy of BWL in conjunction with CBT. Devlin and colleagues [23] compared 20 sessions of CBT plus BWL and either fluoxetine or placebo, to BWL plus placebo or fluoxetine [23]. Post-treatment, all CBT conditions were associated with significantly greater abstinence rates (62% overall) than BWL conditions (33% overall) [23]. Over the course of follow-up, abstinence rates increased in both groups, with CBT conditions remaining superior to BWL conditions at 2-year follow-up [24]. Similarly, a sequential program of CBT followed by BWL did not confer greater benefit than CBTa lone with regard to binge abstinence at the 1-year follow-up [26•]. However, preliminary data suggest that rapid responders in BWL do significantly better than non-rapid responders, with long-term binge abstinence rates similar to patients receiving specialist treatment, and weight loss maintained at 12-month follow up [26•]. Thus, while BWL is more easily disseminable than CBT or IPT, when compared to specialist treatments for BED, current evidence indicates that BWL is not an effective treatment for binge eating in the short- or long-term for most individuals.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy

Rationale

The modification of DBT for BED is based on the affect regulation model of binge eating, which posits that binge eating occurs in response to intolerable emotional experiences when more adaptive coping mechanisms are not accessible. Engaging in binge eating is hypothesized to provide temporary relief from negative affect, reinforcing the behavior. This model of binge eating has been the focus of considerable research, and has sparked interest in the use of DBT as a treatment for BED [54]. DBT comprises four focal areas: mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness. The latter component is often omitted in the study of DBT for BED to avoid overlap with IPT, and to decrease the length of treatment [55]. The main goal of DBT is the development of adaptive emotional regulation skills and their implementation in daily life [56].

Empirical Evidence

Completer analyses from a large study of DBT for BED showed that 89% of DBT participants were abstinent post-treatment, compared with 12.5% of controls [56]. However, abstinence rates dropped to 56% at the 6-month follow-up and comparisons with the control group were not reported [56]. More recently, group DBT was compared with active comparison group therapy (ACGT) [57•]. ACGT was designed to share therapeutic factors with DBT (e.g., therapist alliance, therapeutic optimism, and treatment expectations), without any of the specific components of DBT or other BED treatments [57•]. Both DBT and ACGT resulted in comparable abstinence rates both post-treatment (64% and 36% respectively) and at the 12-month follow-up (64% and 56% respectively) [57•]. Importantly, DBT was associated with significantly lower dropout rates than ACTG, suggesting that DBT was more acceptable to participants [57•]. Furthermore, as discussed below, certain pretreatment participant characteristics predicted better outcome following DBT vs ACTG [58]. While these findings are promising, more research must be conducted to examine the long-term efficacy and success of DBT compared with other specialist treatments for BED.

Alternative or Adjunctive Treatments

Additional treatments for BED have been studied, and may enhance outcomes when included within specialist treatment programs. Appetite Awareness Training targets binge eating by promoting recognition of and response to internal rather than external food cues, and has been associated with greater reductions in binge eating than a wait-list control [59]. Mindfulness has also shown some promise as an adjunct treatment for BED. The purpose of mindfulness is to increase awareness of binge triggers, while increasing self-control and maintaining an attitude of self-acceptance [60]. An initial pilot study of mindfulness-based CBT reported post-treatment abstinence rates of 40% [60]. Finally, adding exercise and virtual reality therapy to specialist treatments for BED has shown efficacy for enhancing weight loss and body image outcomes respectively [61–65]. In sum, adjunct therapies for BED may garner more robust treatment outcomes, but this possibility must be tested in larger and more diverse samples.

Additional Treatment Considerations

Weight and Shape Concerns

A large number of individuals with BED endorse overconcern about weight and shape. Clinical levels of overconcern, referred to as overvaluation of weight and shape, have been associated with greater pre-treatment psychopathology and poorer treatment outcome, and researchers have suggested it be included in the DSM-5 as a severity specifier [66]. Thus, effective treatments for BED must also have an impact on weight and shape concerns in order to truly reduce distress and prevent relapse among those with BED.

Indeed, in studies that have included weight and shape concerns as an outcome, treatments for BED have shown a positive impact. CBT has been shown to be associated with significantly greater reductions in weight and shape concerns compared with no treatment and fluoxetine in both the short and the long term [19, 67]. Furthermore, CBT, CBTgsh, BWL, and IPT are associated with similar decreases in weight and shape concerns, both post-treatment and at up to 2 years following treatment [27, 29, 37•, 39•].

Weight Loss

Treatments for BED have demonstrated a minimal impact on weight loss. However, studies have shown that including an exercise component in CBT is associated with greater weight loss compared to CBT-only, suggesting that exercise might enhance clinically meaningful and sustained weight loss following specialist treatment for BED.

Although studies have shown that BWL produces significantly greater weight loss post-treatment (as compared to CBT, IPT, and CBTgsh), these differences are not maintained long-term [27, 39•]. Furthermore, the addition of BWL during or following CBT does not appear to confer any additional benefit [23, 24, 26]. Notably, one study found that those abstinent from binge eating following CBT who subsequently received BWL experienced weight loss post-treatment (average of 4.0 kg), whereas those who were not abstinent experienced weight gain (average of 3.8 kg) [15]. Thus, BWL may be an effective weight-loss treatment for those who are abstinent from binge eating following specialist treatment, but this finding must be replicated.

Nonetheless, research suggests that abstinence from binge eating is associated with long-term weight maintenance and modest weight loss [26•, 27, 30•, 39•, 68]. Importantly, one study found that individuals with BED reported an average 12-month weight gain of 15 pounds before beginning treatment, whereas weight has been shown to remain stable for up to 4 years following group CBT and IPT [30•, 69]. This can be illustrated by using the example of a patient who binges the minimum of four times per month. If a binge is estimated to contain 1,000 kilocalories, then binge abstinence will prevent the intake of 4,000 kilocalories per month, thus preventing weight gain of 1.1 pounds per month, and 13.7 pounds per year [70]. Thus, psychological treatments for BED likely prevent the upward weight trajectories of individuals with BED.

Predictors, Mediators, and Moderators of Treatment

A number of predictors, mediators, and moderators (i.e., predicts differential treatment response at different levels of the moderator) of treatment outcomes have been identified. These data may be useful in developing stepped-care models that optimize treatment type, duration, and intensity for a given individual, with the ultimate goal of producing more robust outcomes and lowering overall treatment costs.

Nonspecific Predictors

Rapid Response

The best-studied predictor of treatment outcome is rapid response, defined as ≥65–70% reduction in binge eating by the fourth treatment session [71–74]. These studies show that compared to nonrapid responders, rapid responders are more likely to be abstinent immediately following BWL, BWLgsh, and fluoxetine. Conversely, in CBT and CBTgsh, rapid responders and non-rapid responders show similar abstinence rates up to 12 months post-treatment [71–74]. Notably, one study found that a 15% reduction in binge eating by week 1 rather than a 65–70% reduction by week 4, was predictive of post-treatment abstinence following therapist-moderated and self-help CBT treatments [75]. Further defining the influence of rapid response on treatment outcome may enable providers to identify when treatments should be discontinued versus when further improvements can be expected. Furthermore, identifying baseline predictors of rapid response may enhance the potential for matching treatments to individuals with certain baseline characteristics.

Pretreatment Psychopathology

Higher baseline psychopathology has consistently been found to have a negative impact on the effectiveness of BED treatments [39•, 76–80]. Personality disorders have been shown to predict greater post-treatment eating disorder psychopathology and depression following CBTgsh and BWLgsh [77], as well as higher levels of binge eating one year following group CBT and IPT [76, 79]. In addition, pre-treatment depressive symptoms predicted reduced likelihood of post-treatment abstinence following CBT [78], and a lifetime history of depression predicted reduced likelihood of abstinence for 2 years following IPT, BWL, and CBTgsh [39•]. Further, higher trait negative affect was associated with higher post-treatment eating disorder psychopathology and attrition from CBTgsh [77].

Weight and Shape Concerns

Reductions in weight concerns over the course of treatment have been found to fully mediate the association between CBT and abstinence [16]. Similarly, greater weight and shape concerns have been found to predict less likelihood of post-treatment abstinence following group CBT and IPT [79], as well as greater levels of eating disorder psychopathology following CBTgsh [77]. Furthermore, Grilo and colleagues found clinical overvaluation of weight and shape to be the most salient predictor of post-treatment and 12 month abstinence following both CBT and fluoxetine [81•].

Dietary Restraint

Overall, moderate dietary restraint, which is an ultimate goal of CBT-based therapies, is associated with better treatment outcome. Increases in flexible restraint and decreases in rigid restraint over the course of CBTgsh were found in one study to predict higher likelihood of abstinence post-treatment and at the 3-month follow-up [82]. Higher pre-treatment maladaptive restraint was found to predict relapse for 6 months following DBT [83]. Additionally, a greater number of previous diet attempts were found to predict a lower likelihood of post-treatment abstinence following CBT [78]. Furthermore, classifying patients into pure dietary restraint (DR) and dietary restraint-negative affect (DRNA) subtypes demonstrates some predictive validity [84]. The DRNA subtype is associated with greater frequency of binge eating post-treatment compared with the DR subtype, suggesting that individuals who display high levels of dietary restraint and negative affect represent a more severe and treatment-resistant subtype of BED [84].

Demographics

Lower levels of educational attainment have been found to predict poorer treatment outcome. Lower education was found to predict non-abstinence following IPT, CBTgsh, and BWL [38]. Additionally, a meta-analytic review of predictors of treatment response found that lower education predicted higher binge frequency and lack of binge remission following treatment [85]. This review also found that African-Americans were more than twice as likely to drop out of treatment as compared with Caucasians. However, African-Americans demonstrated greater reductions in global eating disorder psychopathology than their Caucasian counterparts. Additionally, an earlier age of onset of binge eating (at or before age 16) was found to predict lack of abstinence post-treatment [105].

Grilo and colleagues [81•] also identified important demographic predictors of treatment outcome. They found that, when comparing CBT plus fluoxetine, CBT-only, and fluoxetine-only, younger participants were more likely to achieve abstinence than older participants when given fluoxetine, whereas older participants saw greater reductions in depression if given CBT. Further, older age at BED onset predicted faster reductions in binge eating frequency and eating disorder psychopathology if receiving CBT versus fluoxetine-only.

Moderators

Only a limited number of studies have identified moderators of treatment outcome. Sysko and colleagues [43] identified two classes of severity that predicted differential response to IPT, CBTgsh, and BWL [39•, 43]. The highest rates of abstinence were found for “class 2” (i.e., most frequent binge eating and compensatory behaviors, highest weight and shape concerns and negative affect, and most distress) individuals receiving IPT and “class 3” (i.e., similar levels of binge eating to “class 2,” with lower levels of exercise and compensatory behaviors) individuals receiving CBTgsh [43]. Within this sample, IPT was also associated with superior 2-year abstinence rates among participants with lower baseline self-esteem and/or higher baseline eating disorder psychopathology [39•].

Grilo and colleagues [81•] found that higher pretreatment binge eating frequency predicted greater reductions in eating disorder psychopathology if receiving CBT as opposed to fluoxetine [81•]. Additionally, participants with lower self-esteem saw greater reductions in depression if they received CBT rather than fluoxetine. Finally, those categorized as having negative affect or overvaluation of weight/shape subtype saw greater reductions in eating disorder pathology and depression if receiving CBT versus fluoxetine [81•]. Furthermore, although DBT and active comparison group therapy (ACGT) were found to produce similar long-term outcomes, those who reported earlier onset of overweight and dieting (i.e., <15 years old) or who met criteria for avoidant personality disorder reported a reduction in binge days post-treatment only if they received DBT [58].

Overall, current research has identified nonspecific predictors of both short-term and long-term abstinence, such as rapid response, negative affect, weight/shape concerns, and extreme dietary restraint. These variables have also been found to predict dimensional outcomes, including depression and eating disorder psychopathology. A small number of studies have identified moderators of treatment outcome, including pre-treatment eating disorder severity, negative affect, and overvaluation of weight and shape. Further research is needed to replicate these findings and to establish the reliability of these predictors and moderators in order to inform the development of treatment matching algorithms and stepped-care models.

Future Directions

A potential next step for clinicians and researchers is to respond to the National Institute for Mental Health’s strategic plan (National Institute of Mental Health Strategic Plan, http://www.nimh.nih.gov) to:

Enhance the public health impact of current treatments

Incorporate the diverse needs of patients

Promote discovery in the brain and behavioral sciences

Chart mental illness trajectories to determine when, where, and how to intervene.

Enhance the Public Health Impact of Current Treatments

There is a need to translate evidence-based treatments for BED into clinical settings in order to increase access to care. Although there are robust treatments for BED, their use in clinical practice is relatively scarce [86]. Dissemination and implementation science will enable the identification of the most effective strategies for training practitioners and implementing treatments in diverse clinical settings in a sustainable manner. For example, researchers may examine the relative effectiveness of traditional training models (e.g., expert-led workshops) versus models that promote systemic change (e.g., training staff to become expert trainers and supervisors), to identify which will most likely increase adoption, penetration, and sustainability of treatments.

Furthermore, the potential for telecare, the internet, and other technologies to enhance access to treatments for BED is a burgeoning area of research. For example, one study found that email bulimia therapy (i.e., participants interacting with therapists via email) was more effective than self-directed writing and a wait-list control in reducing binge eating [87]. Internet-based CBTgsh has also shown preliminary efficacy [88, 40, 41], and other technologies such as texting and daily electronic diaries have shown efficacy for problems such as smoking and obesity [89, 90]. Such studies demonstrate that scalable therapies for BED may be as effective as more intensive treatments. However, relatively high attrition rates seen in such therapies must be addressed effectively by, for example, enhancing treatment engagement and adherence (e.g., adding social networking components).

Incorporating the Diverse Needs of Patients

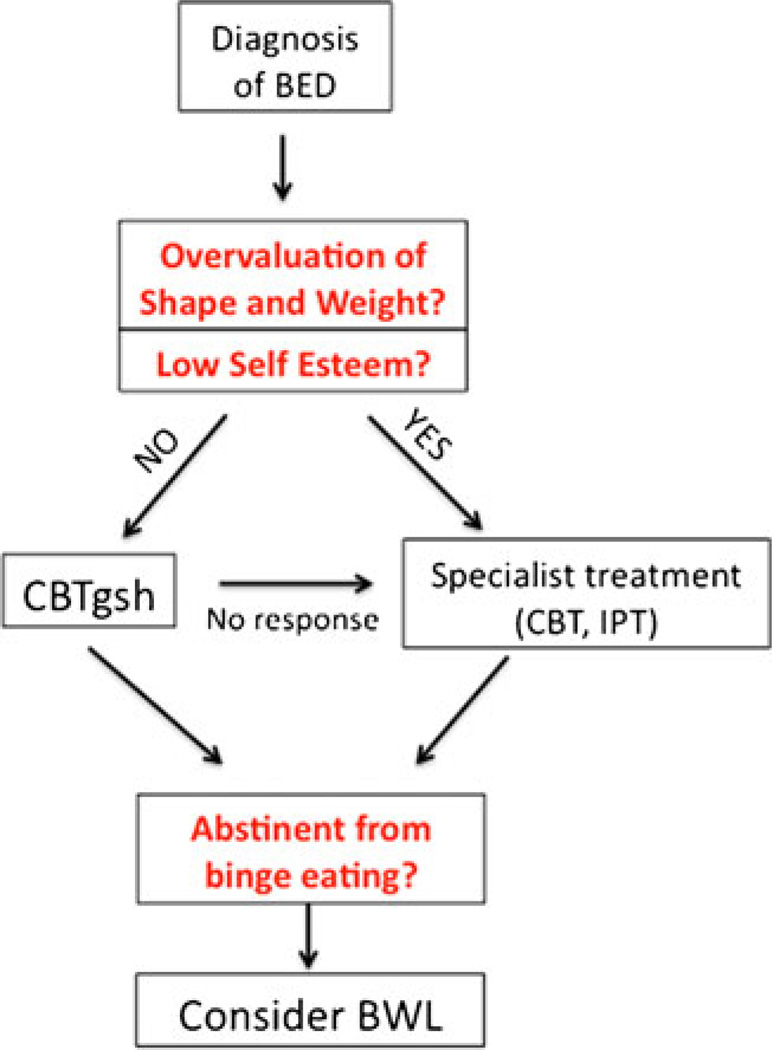

Research suggests that certain treatment modalities are more effective than others for individuals with particular pretreatment characteristics. Incorporating such knowledge into treatment planning may enable the development of successful stepped-care models. For example, individuals with BED uncomplicated by additional pathology may be initially treated with CBTgsh, whereas those with high levels of eating disorder psychopathology or negative affect may be treated initially with group or individual IPT or CBT (see Fig. 1). Additionally, methods for adapting treatments to specific sub-populations (e.g., ethnic minorities) are still a matter of inquiry. Notably, studies suggest that African-Americans with BED are less likely to drop out of IPT than CBTgsh and BWL [39•]. It will be important to include key stakeholders (e.g., patients, families, community health providers) in treatment development to modify treatments so that they address eating- and weight-related issues in a manner appropriate and acceptable to the target population.

Fig. 1.

Potential stepped care model for the treatment of binge eating disorder (BED)

Promote Discovery in the Brain and Behavioral Sciences

Treatments that can simultaneously address binge eating and obesity may be identified through basic biological and behavioral research investigating their causal mechanisms. Research has shown that high fat/sugar foods, and drugs of abuse act similarly on brain reward pathways [91, 92], and there is growing evidence of brain reward dysfunction in both BED and obesity [93–95].

Such brain abnormalities may be linked with behavioral problems [93], sometimes labeled “reinforcement pathology” [96], including high impulsivity and the inability to delay gratification [97–99]. In addition, overabundance of high fat/sugar foods in the environment may place individuals with genetic, neurological, and/or cognitive-behavioral vulnerabilities at increased risk of the development of binge eating and obesity.

As such, psychological treatments for BED may produce even more robust outcomes when including adjuvant pharmacotherapies or behavioral therapies that specifically target brain reward system abnormalities associated with reinforcement pathology. For example, a behavioral therapy that targets high food reinforcement may focus on enhancing the availability of alternate reinforcers across the home, school/work, and community milieus. Indeed, treatments with a socio-environmental approach have been shown to produce weight maintenance in the long term for overweight children [100, 101], as such strategies create healthy zones across settings and promote sustainable outcomes. The integration of state-of-the-science research on the treatment and prevention of both BED and obesity is crucial to producing more robust treatment outcomes.

Chart Mental Illness Trajectories to Determine When, Where, and how to Intervene

It is well-known that binge eating pathology in childhood and adolescence is associated with excess weight gain over time and increased risk of developing BED [7, 102, 103]. Early identification and treatment of children at risk for the development of BED will be critical, as psychological interventions are likely to be most potent during transitional periods of adolescent brain development [104]. Treatment studies with children and adolescents with early onset or at high risk of developing BED are imperative. IPT has been modified for adolescent girls with loss of control eating to be efficacious for reducing eating pathology and preventing weight gain [102]. Furthermore, developing, implementing, and evaluating therapist-led and internet-based treatments within multiple contexts (e.g., school, primary care, home) will be crucial in establishing the long-term health outcomes.

Conclusion

Overall, research shows that CBT, IPT, and CBTgsh, which directly target binge eating and associated pathology, are associated with the most robust short- and long-term binge abstinence rates. Additionally, DBT shows promise as a specialist treatment for BED, but further research is needed to elucidate its long-term efficacy compared with nonspecific and established therapies for BED. Furthermore, a number of treatment adjuncts (e.g., mindfulness, physical activity) have shown preliminary efficacy and may be useful for improving overall health, well-being, and sustainability of outcomes. Conversely, BWL, a generalist treatment that targets weight loss rather than binge eating, does confer some benefit but is not as effective as specialist treatments.

Important nonspecific predictors and moderators of treatment outcomes have been identified. Greater pre-treatment eating disorder psychopathology and negative affect are negative prognostic indicators for all BED treatments. However, when low-dose treatments (e.g., CBTgsh) and pharmacotherapy (e.g., fluoxetine) are compared with more intensive treatments (e.g., IPT and CBT), the latter are more effective for those with more severe illness. Rapid response, weight and shape concerns, and extreme dietary restraint are also nonspecific predict treatment outcomes. Continued research into this area will enable the development of stepped-care treatment models. Future practice and research is required to maximize the availability, accessibility, and effectiveness of evidence-based psychological treatments for BED, as well as their ability to target binge eating and weight control simultaneously.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Heather Waldron for her assistance in preparing this manuscript.

The following funding sources are also acknowledged: NIDDK grant 5T32HL007456, NIMH grants 5K24MH070446-09, 1R01MH095748 and 5R29MH051384, CTSA grant UL1RR024992, and the Washington University Chancellor's Graduate Fellowship Program.

Footnotes

Disclosure J.M. Iacovino, D.M. Gredysa, and M. Altman reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article. D.E. Wilfley has received research grants from National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); has served as a board member of Minnesota Obesity Center, Wellspring Academies, and UnitedHealth Group; and has served as a consultant for Lee Regional Visiting Nurse Association.

Contributor Information

Juliette M. Iacovino, Department of Psychology, Washington University in St. Louis, Campus Box 1125, One Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130, USA, jcmcclen@wustl.edu

Dana M. Gredysa, Department of Psychology, Washington University in St. Louis, Campus Box 1125, One Brookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130, USA

Myra Altman, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8134, 660S Euclid, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA.

Denise E. Wilfley, Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8134, 660S Euclid, St. Louis, MO 63110, USA

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor CB, Bryson S, Celio Doyle AA, et al. The adverse effect of negative comments about weight and shape from family and siblings on women at high risk for eating disorders. Pediatrics. 2006;118:731–738. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicdao EG, Hong S, Takeuchi DT. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders among Asian Americans: results from the national Latino and Asian American study. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:S22–S26. doi: 10.1002/eat.20450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alegria M, Woo M, Cao Z, et al. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in Latinos in the United States. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:S15–S21. doi: 10.1002/eat.20406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goossens L, Braet C, Decaluwé V. Loss of control over eating in obese youngsters. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan CM, Yanovski SZ, Nguyen TT, et al. Loss of control over eating, adiposity, and psychopathology in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31:430–441. doi: 10.1002/eat.10038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Goossens L, Eddy KT, et al. A multisite investigation of binge eating behaviors in children and adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:901–913. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rieger E, Wilfley DE, Stein RI, et al. A comparison of quality of life in obese individuals with and without binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37:234–240. doi: 10.1002/eat.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilfley DE, Wilson GT, Agras WS. The clinical significance of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34(Suppl):S96–S106. doi: 10.1002/eat.10209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wonderlich SA, Gordon KH, Mitchell JE, et al. The validity and clinical utility of binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:687–705. doi: 10.1002/eat.20719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reas DL, Grilo CM. Review and meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy for binge-eating disorder. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2024–2038. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vocks S, Tuschen-Caffier B, Pietrowsky R, et al. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:205–217. doi: 10.1002/eat.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Telch CF, Agras WS, Rossiter EM, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment for the nonpurging bulimic: an initial evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:629–635. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson GT, Shafran R. Eating disorders guidelines from nice. Lancet. 2005;365:79–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17669-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agras WS, Telch CF, Arnow B, et al. One-year follow-up of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obese individuals with binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:343–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dingemans AE, Spinhoven P, van Furth EF. Predictors and mediators of treatment outcome in patients with binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:2551–2562. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eldredge KL, Agras WS. The relationship between perceived evaluation of weight and treatment outcome among individuals with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22:43–49. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199707)22:1<43::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorin AA, Le Grange D, Stone AA. Effectiveness of spouse involvement in cognitive behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;33:421–433. doi: 10.1002/eat.10152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlup B, Munsch S, Meyer AH, et al. The efficacy of a short version of a cognitive-behavioral treatment followed by booster sessions for binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:628–635. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilfley DE, Agras WS, Telch CF, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the nonpurging bulimic individual: a controlled comparison. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:296–305. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenardy J, Mensch M, Bowen K, et al. Group therapy for binge eating in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Diabet Med. 2002;19:234–239. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agras WS, Telch CF, Arnow B, et al. Weight loss, cognitive-behavioral, and desipramine treatments in binge eating disorder: an additive design. Behav Ther. 1994;25:225–238. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devlin MJ, Goldfein JA, Petkova E, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine as adjuncts to group behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. Obes Res. 2005;13:1077–1088. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devlin MJ, Goldfein JA, Petkova E, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for binge eating disorder: two-year follow-up. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:1702–1709. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grilo CM, Masheb RM. A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1509–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, et al. Cognitive–behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge-eating disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:675–685. doi: 10.1037/a0025049. This study (N=125) compared 16 sessions of CBT (24% attrition), 16 sessions of BWL (31% attrition), and 16 sessions of CBT followed by 16 sessions of BWL (40% attrition). All participants were obese. Post-treatment, 6-month, and 12-month follow-ups were completed. At the 12-month follow-up, abstinence rates were 51% (CBT), 36% (BWL), and 40% (CBT + BWL), and average reductions in percent BMI were −0.9, −2.1, and 1.5 respectively. CBT was associated with higher rates of binge abstinence through the 12-month follow-up, whereas BWL was associated with greater weight loss during treatment. However, at the 12-month follow-up, all conditions were associated with statistically equivalent weight loss. Binge abstinence was associated with greater weight loss post-treatment and at the 12-month follow-up.

- 27.Munsch S, Biedert E, Meyer A, et al. A randomized comparison of cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss treatment for overweight individuals with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:102–113. doi: 10.1002/eat.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ricca V, Castellini G, Mannucci E, et al. Comparison of individual and group cognitive behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. A randomized, three-year follow-up study. Appetite. 2010;55:656–665. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge-eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:713–721. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hilbert A, Bishop ME, Stein RI, et al. Long-term efficacy of psychological treatments for binge eating disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200:232–237. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.089664. This study examined the long-term efficacy of outpatient CBT and IPT groups. The sample had participated in Wilfley and colleagues’ 2002 study. Four years following the completion of treatment, participants in both groups showed substantial long-term recovery, partial remission, as well as significant reductions in associated psychopathology, with no significant differences found between groups.

- 31.Claudino AM, de Oliveira IR, Appolinario JC, et al. Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate plus cognitive-behavior therapy in binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatr. 2007;68:1324–1332. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fairburn CG. Overcoming binge eating. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carter JC, Fairburn CG. Cognitive-behavioral self-help for binge eating disorder: a controlled effectiveness study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:616–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, et al. The efficacy of self-help group treatment and therapist-led group treatment for binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1347–1354. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder: a comparison of therapist-led versus self-help formats. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;24:125–136. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199809)24:2<125::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson CB, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, et al. Self-help versus therapist-led group cognitive-behavioral treatment of binge eating disorder at follow-up. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;30:363–374. doi: 10.1002/eat.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Striegel-Moore RH, Wilson GT, DeBar L, et al. Cognitive behavioral guided self-help for the treatment of recurrent binge eating. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:312–321. doi: 10.1037/a0018915. This study compared CBTgsh with treatment as usual in a sample of adults (N=123). The treatment was delivered my masters-level trained therapists within a primary care setting. The majority of participants had a diagnosis of full-syndrome or sub-clinical BED (89%), whereas the other 11% had a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa. Post-treatment, and 6-month and 12-month follow-up data were collected. At the 12-month follow-up, CBTgsh was associated with higher abstinence rates than treatment as usual (64% vs 45%). CBTgsh was also associated with greater reductions in eating disorder psychopathology (i.e., dietary restraint and shape, weight, and eating concerns) and improvements in social adjustment.

- 38.Wilson GT, Zandberg LJ. Cognitive–behavioral guided self-help for eating disorders: effectiveness and scalability. Clin Psych Rev. 2012;32:343–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras WS, et al. Psychological treatments of binge eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:94–101. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.170. This large-scale RCT compared IPT, CBTgsh, and BWL in the treatment of BED. Two years following the completion of treatment, IPT and CBTgsh resulted in significantly greater binge remission than BWL. Self-esteem and Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) scores were both moderators of binge abstinence, in that IPT was equally as effective regardless of self-esteem or EDE score; CBTgsh was less effective for those with both low self-esteem and high EDE scores; and BWL was less effective for those with low self-esteem, high EDE scores, or both.

- 40.Ljotsson B, Lundin C, Mitsell K, et al. Remote treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: a randomized trial of internet-assisted cognitive behavioural therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:649–661. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carrard I, Crépin C, Rouget P, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a guided self-help treatment on the internet for binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sysko R, Walsh BT. A critical evaluation of the efficacy of self-help interventions for the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:97–112. doi: 10.1002/eat.20475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sysko R, Hildebrandt T, Wilson GT, et al. Heterogeneity moderates treatment response among patients with binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:681–690. doi: 10.1037/a0019735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almeida L, Savoy S, Boxer P. The role of weight stigmatization in cumulative risk for binge eating. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(3):278–292. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Striegel-Moore RH, Fairburn CG, Wilfley D, Pike KM, Dohm FA, Kraemer HC. Toward an understanding of risk factors for binge-eating disorder in black and white women: a community-based case-control study. Psychol Med. 2005;35(6):6. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rieger E, Van Buren DJ, Bishop M, et al. An eating disorder-specific model of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT-ED): causal pathways and treatment implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:400–410. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.001. This paper details the theoretical rationale for IPT for binge-related eating disorders. The authors provide a description of and evidence for the interpersonal model of binge eating. The interpersonal model posits that interpersonal deficits set individuals at risk of experiencing unsatisfying interpersonal interactions or social isolation, which lead to negative affect. In turn, individuals turn to food to cope with negative emotions and self-evaluations associated with unfulfilling social interactions. The paper describes IPT as intervening at the level of social deficits and/or communication patterns in order to increase positive social interactions and to reduce negative affect and subsequent binge eating.

- 47.Wolfe BE, Baker CW, Smith AT, Kelly-Weeder S. Validity and utility of the current definition of binge eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:674–686. doi: 10.1002/eat.20728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tasca GA, Ritchie K, Conrad G, et al. Attachment scales predict outcome in a randomized controlled trial of two group therapies for binge eating disorder: an aptitude by treatment interaction. Psychother Res. 2006;16:106–121. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Young JF, et al. A pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy for preventing excess weight gain in adolescent girls at-risk for obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;43:701–706. doi: 10.1002/eat.20773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanofsky-Kraff WS, Walsh T, Fairburn CG, et al. A multicenter comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:459–466. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chui W, Safer DL, Bryson SW, et al. A comparison of ethnic groups in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Eat Behav. 2007;8:485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith DE, Marcus MD, Lewis CE, et al. Prevalence of binge eating disorder, obesity, and depression in a biracial cohort of young adults. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20:227–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02884965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blaine B, Rodman J. Responses to weight loss treatment among obese individuals with and without bed: a matched-study meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord. 2007;12:54–60. doi: 10.1007/BF03327579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polivy J, Herman CP. In: Etiology of binge eating: psychological mechanisms. Binge eating: nature, assessment and treatment. Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 173–205. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiser S, Telch CF. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychol. 1999;55:755–768. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199906)55:6<755::aid-jclp8>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Telch CF, Agras WS, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:1061–1065. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Safer DL, Robinson AH, Jo B. Outcome from a randomized controlled trial of group therapy for binge eating disorder: comparing dialectical behavior therapy adapted for binge eating to an active comparison group therapy. Behav Ther. 2010;41:106–120. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.01.006. This study (N=101) compared the effects of group DBT for BED with an active comparison group therapy. DBT-BED showed greater initial efficacy, and fewer treatment dropouts; however, differences were not sustained over the long term, with both treatments resulting in large abstinence rates. The authors hypothesize that there are no specific long-term effects of DBT-BED over shared therapeutic factors.

- 58.Robinson AH, Safer DL. Moderators of dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder: results from a randomized controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:597–602. doi: 10.1002/eat.20932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allen C, Craighead LW. Appetite monitoring in the treatment of binge eating disorder. Behav Ther. 1999;30:253–272. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kristeller JL, Hallett B. An exploratory study of a meditation-based intervention for binge eating disorder. J Health Psychol. 1999;4:357–363. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fossati M, Amati F, Painot D, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with simultaneous nutritional and physical activity education in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Eat Weight Disord. 2004;9:134–138. doi: 10.1007/BF03325057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pendleton VR, Goodrick GK, Poston WSC, et al. Exercise augments the effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of binge eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31:172–184. doi: 10.1002/eat.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Riva G, Bacchetta M, Baruffi M, et al. Virtual reality-based multidimensional therapy for the treatment of body image disturbances in obesity: a controlled study. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2001;4:511–526. doi: 10.1089/109493101750527079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riva G, Bacchetta M, Baruffi M, et al. Virtual-reality-based multidimensional therapy for the treatment of body image disturbances in binge eating disorders: a preliminary controlled study. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2002;6:224–234. doi: 10.1109/titb.2002.802372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riva G, Bacchetta M, Cesa G, et al. Six-month follow-up of inpatient experiential cognitive therapy for binge eating disorders. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2003;6:251–258. doi: 10.1089/109493103322011533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grilo CM, Hrabosky JI, White MA, et al. Overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder and overweight controls: refinement of a diagnostic construct. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:414–419. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nauta H, Hospers H, Kok G, et al. A comparison between a cognitive and a behavioral treatment for obese binge eaters and obese non-binge eaters. Behav Ther. 2000;31:441–461. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blomquist KK, Barnes RD, White MA, et al. Exploring weight gain in year before treatment for binge eating disorder: a different context for interpreting limited weight losses in treatment studies. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44:435–439. doi: 10.1002/eat.20836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Raymond NC, Peterson RE, Bartholome LT, Raatz SK, Jensen MD, Levine JA. Comparisons of energy intake and energy expenditure in overweight and obese women with and without binge eating disorder. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(4):765–772. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Rapid response predicts binge eating and weight loss in binge eating disorder: findings from a controlled trial of orlistat with guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:2537–2550. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Rapid response to treatment for binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:602–613. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grilo CM, White MA, Wilson GT, et al. Rapid response predicts 12-month post-treatment outcomes in binge-eating disorder: theoretical and clinical implications. Psychol Med. 2011:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Rapid response predicts treatment outcomes in binge eating disorder: implications for stepped care. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:639–644. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zunker C, Peterson CB, Cao L, et al. A receiver operator characteristics analysis of treatment outcome in binge eating disorder to identify patterns of rapid response. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:1227–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wilfley DE, Friedman MA, Dounchis JZ, et al. Comorbid psychopathology in binge eating disorder: relation to eating disorder severity at baseline and following treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:641–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Examination of predictors and moderators for self-help treatments of binge-eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:900–904. doi: 10.1037/a0012917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Castellini G, Mannucci E, Lo Sauro C, et al. Different moderators of cognitive-behavioral therapy on subjective and objective binge eating in bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: a three-year follow-up study. Psychother Psychosom. 2012;81:11–20. doi: 10.1159/000329358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hilbert A, Saelens BE, Stein RI, et al. Pretreatment and process predictors of outcome in interpersonal and cognitive behavioral psychotherapy for binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:645–651. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pendleton VR, Willems E, Swank P, et al. Negative stress and the outcome of treatment for binge eating. Eat Disord. 2001;9:351–360. doi: 10.1080/106402601753454912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Crosby RD. Predictors and moderators of response to cognitive behavioral therapy and medication for the treatment of binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0027001. in press. In this study, based on Grilo and colleagues’ 2005 trial comparing CBT and fluoxetine treatments, the authors identified a number of predictors and moderators of treatment outcome. Younger age predicted better outcome from fluoxetine, whereas older age at BED onset predicted faster reductions in binge eating frequency and eating disorder psychopathology if receiving CBT, and older age predicted greater reductions in depression if receiving CBT. Lower self-esteem, negative affect, and overvaluation of weight and shape were associated with better outcome from CBT compared with fluoxetine. Furthermore, overvaluation of weight and shape predicted greater reductions in eating disorder psychopathology and depression following CBT versus fluoxetine. The authors suggest that these findings might drive treatment planning, and that the robust nature of overvaluation as a moderator and predictor suggests that it should be included as a diagnostic specifier for BED.

- 82.Blomquist KK, Grilo CM. Predictive significance of changes in dietary restraint in obese patients with binge eating disorder during treatment. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44:515–523. doi: 10.1002/eat.20849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Safer DL, Lively TJ, Telch CF, et al. Predictors of relapse following successful dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32:155–163. doi: 10.1002/eat.10080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Prognostic significance of two sub-categorization methods for the treatment of binge eating disorder: negative affect and overvaluation predict, but do not moderate, specific outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Thompson-Brenner H, Franko DL, Thompson DR, Grilo CM, Boisseau CL, Roehrig JP, et al. Race/ethnicity, education, and treatment parameters as moderators and predictors of outcome in binge eating disorder. Presented at the 17th Annual Meeting of the Eating Disorders Research; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kazdin AE. Evidence-based treatment and practice: new opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. Am Psychol. 2008;63:146–159. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Robinson P, Serfaty M. Getting better byte by byte: a pilot randomised controlled trial of email therapy for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2008;16:84–93. doi: 10.1002/erv.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jones M, Luce KH, Osborne MI, Taylor K, Cunning D, Doyle AC, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an internet-facilitated intervention for reducing binge eating and overweight in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):453–462. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Woolford SJ, Clark SJ, Strecher VJ, et al. Tailored mobile phone text messages as an adjunct to obesity treatment for adolescents. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16:458–461. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.100207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gwaltney CJ, Bartolomei R, Colby SM, et al. Ecological momentary assessment of adolescent smoking cessation: a feasibility study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1185–1190. doi: 10.1080/14622200802163118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kenny PJ. Common cellular and molecular mechanisms in obesity and drug addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:638–651. doi: 10.1038/nrn3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kelley AE, Berridge KC. The neuroscience of natural rewards: relevance to addictive drugs. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3306–3311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03306.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Logan J, et al. Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancet. 2001;357:354–357. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Maynard L, et al. Brain dopamine is associated with eating behaviors in humans. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;33:136–142. doi: 10.1002/eat.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. Overlapping neuronal circuits in addiction and obesity: evidence of systems pathology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3191–3200. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Epstein LH, Salvy SJ, Carr KA, et al. Food reinforcement, delay discounting and obesity. Physiol Behav. 2010;100:438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Manwaring JL, Green L, Myerson J, et al. Discounting of various types of rewards by women with and without binge eating disorder: evidence for general rather than specific differences. Psychol Rec. 2011;61:22. doi: 10.1007/bf03395777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fields SA, Sabet M, Peal A, et al. Relationship between weight status and delay discounting in a sample of adolescent cigarette smokers. Behav Pharmacol. 2011;22:266–268. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328345c855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Weller RE, Cook EW, Iii, Avsar KB, et al. Obese women show greater delay discounting than healthy-weight women. Appetite. 2008;51:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wilfley DE, Stein RI, Saelens BE, et al. Efficacy of maintenance treatment approaches for childhood overweight: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1661–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wilfley DE, Van Buren DJ, Theim KR, et al. The use of biosimulation in the design of a novel multilevel weight loss maintenance program for overweight children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(Suppl 1):S91–S98. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Schvey NA, et al. A prospective study of loss of control eating for body weight gain in children at high risk for adult obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:26–30. doi: 10.1002/eat.20580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Olsen C, et al. A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120:108–118. doi: 10.1037/a0021406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA. The adolescent brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:111–126. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Agras WS, Telch CF, Arnow B, et al. Does interpersonal therapy help patients with binge eating disorder who fail to respond to cognitive-behavioral therapy? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:356–360. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Loeb KL, Wilson GT, Gilbert JS, Labouvie E. Guided and unguided self-help for binge eating. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:259–272. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]