Abstract

High activity of dendritic cells (DCs) in inducing cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) led to their application as therapeutic cancer vaccines. The ability of DCs to produce IL-12p70 is one of the key requirements for effective CTL induction and a predictive marker of their therapeutic efficacy in vivo. We have previously reported that defined cocktails of cytokines, involving TNFα and IFNγ, induce mature type-1 polarized DCs (DC1s) which produce strongly elevated levels of IL-12 and CXCL10/IP10 upon CD40 ligation compared to “standard” PGE2-matured DCs (sDCs; matured with IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and PGE2) and show higher CTL-inducing activity. Guided by our observations that DC1s can be induced by TNFα- and IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells, we have tested the feasibility of using lymphocytes to generate DC1s in a clinically-compatible process, to limit the need for clinical-grade recombinant cytokines and the associated costs. CD3/CD28 activation of bulk lymphocytes expanded them and primed them for effective production of IFNγand TNFαfollowing restimulation. Restimulated lymphocytes, or their culture supernatants, enhanced the maturation status of immature (i)DCs, elevating their expression of CD80, CD83 and CCR7, and the ability to produce IL-12p70 and CXCL10 upon subsequent CD40 ligation. The “lymphocyte-matured” DC1s showed elevated migration in response to the lymph-node-directing chemokine, CCL21, when compared to iDCs. When loaded with antigenic peptides, supernatant-matured DCs induced much high levels of CTLs recognizing tumor-associated antigenic epitope, than PGE2-matured DCs from the same donors. These results demonstrate the feasibility of generation of polarized DC1s using autologous lymphocytes.

Keywords: Dendritic cells, DC1 polarization, effector CD8+ T cells, IL-12p70, cancer

INTRODUCTION

Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs), specialized in inducing T cell responses [1, 2]. Upon antigen encounter, DCs take up antigenic material, undergo maturation , and migrate from peripheral sites to draining lymph nodes where they are able to prime naïve antigen-specific T cells by providing them with processed antigen in the form of antigenic peptides complexed with MHC class I molecules (signal 1) [3, 4]. In addition to this signal 1, mature DCs also express co-stimulatory molecules (signal 2) that regulate the magnitude of the T cells responses. They also to secrete different amounts of cytokines (signal 3), which determine the type of T cell response (i.e. Th1, Th2, Th17) that is elicited [5-8].

The ability of DCs to elicit T cell responses has been the rationale for the use of DCs as cancer vaccines in clinical trials [9, 10]. Furthermore, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved the use of the first DC-containing cellular immunotherapy, Sipuleucel–T, (Provenge) for the treatment of hormone-refractory prostate cancer. While Provenge provides a 4 month survival benefit over placebo-treated patients, it does not affect the time to progression or tumor burden [11]. These results indicate the feasibility of DC-based therapies for cancer, but also highlight the need for optimization of the methods of DC generation.

The production of high levels of interleukin-12 (IL-12) [12] by DC vaccines has been shown to correlate with their enhanced induction of anti-tumor responses [13-16] and predict their therapeutic benefit in vivo [17].Various maturation protocols are being used for the generation of type-1 polarized monocyte-derived DCs (DC1) that have high IL-12 production capacity in clinically-applicable conditions. These maturation protocols are based on the use of inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IFNγ, IFNα, and TNFα) and/or Toll-like receptor ligands (e.g. LPS and polyI:C) [18-22]. While the different maturation protocols are effective at polarizing DCs for high IL-12 production, for use in a clinical setting these maturation and polarization protocols require the use of clinical grade cytokines, which make the production of the DCs expensive.

We have previously shown that activated lymphocytes produce IFNγand/or TNFα. Naïve CD8+ T cells can perform a helper function, by producing IFNγand TNFα, in co-activating DCs for the secretion of high levels of IL-12 [23, 24]. The ability of lymphocytes to produce IFNγand TNFαupon activation, and to use these factors to induce maturation and type-1 polarization of DCs [23, 25] prompted us to analyze whether this function could be used to induce DC1-based cancer vaccines in a clinically-compatible process, as alternative to immature DCs used in the currently-approved DC-containing Provenge.

Here we report on the ability to induce maturation and polarization of DCs using expanded autologous lymphocytes. The lymphocyte-matured DCs have a high expression of co-stimulatory molecules, migrate in response to the lymph node-associated chemokine CCL21, and produce high levels of bioactive IL-12p70 and interferon-inducible protein 10 (IP-10/CXCL10). When lymphocyte-matured DCs were loaded with peptides representing various tumor-associated antigens (MART-1, gp100, PSA2 and PAP-3), they induce strong peptide-specific CTL responses in autologous naïve CD8+ T cells.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Cell lines, media and reagents

Serum-free AIM-V medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to generate DCs and Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM; Invitrogen) with 5% human AB serum (Gemini Bio-products, West Sacramento, CA) was used for CTL induction experiments. The following factors were used to generate mature DCs: rhGM-CSF and rhIL-4 (gifts from Schering Plough, Kenilworth, NJ), rhTNFα, rhIL-1β(both Strathmann Biotech, Germany), rhIL-6 (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA), Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). IL-2 and rhIL-7 (Strathmann Biotech) were used to support the CD8+ T cell expansion.

Generation of DCs from healthy donors and cancer patients

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PMBCs) were obtained from healthy donors or from buffy coats (obtained from the blood bank) using lymphocyte separation medium (Cellgro, Mediatech, Herndon, VA). CD14+ monocytes were isolated from PBMCs using CD14+ isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). Peripheral blood from melanoma patients was collected in accordance with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Pittsburgh. All patients had given written consent. Blood was obtained by leukapheresis and cell subsets were separated by elutriation density gradient separation (Elutra) and stored in liquid nitrogen. In both cases, the resulting monocytes were cultured in serum-free AIM-V medium supplemented with rhGM-CSF (1000 U/ml) and rhIL-4 (1000 U/ml) in 24 well plates at 5-6 × 105 cells/ml for 5 days. On day 3, half the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing rhGM-CSF and rhIL-4 (both at final concentration 1000 U/ml). On day 5, immature (i)DCs were matured for 24 hours by removing half the medium and adding fresh medium containing the maturation factors described below.

Expansion of bulk lymphocytes

Total CD14-negative cells from healthy donors, from CD14+ isolation described above, or fraction 3 Elutra cells from cancer patients were washed and resuspended in IMDM supplemented with 5% human AB serum (Gemini Bio-products) at 1 × 106 cells/ml. Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Invitrogen Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway) were added to the lymphocytes at 5 μl/ml and cells were expanded for 6-7 days in 12 well plates with 2 ml/well. On day 3, fresh medium was added to the expanding cells.

Cytokine production by expanded lymphocytes

Day 6-7 expanded lymphocytes were collected in 50 ml conical tubes and CD3/CD28 beads were removed by placing the tube in a magnet for 15 minutes. Bead-free cell suspension was transferred to a fresh tube and cells were washed and resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml in serum-free AIM-V. Expanded lymphocytes were restimulated in either 96 well plates (for analysis of cytokine production) or 6 well plates (for DC maturation) with either plate-bound OKT3 Ab (1μg/ml; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or 5 μl/ml CD3/CD28 beads. At the indicated times, supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C until analysis by ELISA. Briefly, ELISA plates were coated overnight at room temperature (RT) with 2 μg/ml monoclonal anti-human IFNγAb (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) or 2 μg/ml monoclonal anti-human TNFαAb (Endogen). After incubation, plates were blocked using PBS with 4% Bovine Serum Albumin for 1 hour at RT. Plates were washed (50 mM Tris/0.2% Tween) and incubated with culture supernatants or appropriate cytokine standards for 1 hour. Supernatants were removed and plates were incubated for 1 hour with biotin-labeled monoclonal Abs against IFNγor TNFα (both at 0.5 μg/ml). Following incubation, plates were washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Thermo Scientific) for 30 minutes, after which the plates were washed and incubated with 100 μl TMB substrate solution (Pierce Biotechnology Inc, Rockford, IL). The color reactions were stopped by addition of 100 μl 2% H2SO4 and the absorbance was measured at 450nm.

Maturation of DCs

To induce the maturation of day 5 DCs, half the medium was removed and replaced with 500μl fresh serum-free AIM-V medium containing: (for iDC): rhGM-CSF and IL-4 (both 1000 U/ml) only; (for PGE2-matured “standard” DC; sDC): rhGM-CSF (1000 U/ml) rhIL-1β(25 ng/ml) rhIL-6 (1000 U/ml) rhTNFα(50 ng/ml) and PGE2; 10−6 M); (for lymphocyte-CD3/CD28-matured DCs): rhGM-CSF, 2 × 105 expanded lymphocytes/ml and αCD3/αCD28 beads (5 μl/ml); (for lymphocyte-OKT3-matured DCs), rhGM-CSF, 2 × 105 expanded lymphocytes/ml and OKT3 (1 μg/ml); or (for supernatant-matured DCs; supDC): rhGM-CSF and 500μl supernatant from 24 hour restimulated expanded lymphocytes. DCs were matured for 24 hours at 37°C. The recovery of supernatant-matured DCs was less than that of PGE2-matured DCs but only slightly less than previously observed for other type-1 polarized DCs generated in our lab (αDC1). Typical cell yields were: PGE2-matured DC: 1:3-5 (1 DC recovered per 3-5 monocytes plated); supernatant DCs: 1:9-12; iDC: 1:6-13). For the analysis of DC maturation markers, matured DCs were collected, resuspended in IMDM-5% HS and kept overnight at 37°C before performing flow cytometric analysis. We have previously observed that the CCL19 production during type-1 polarized DC maturation results in transient internalization of surface CCR7, which is restored after removing the cells from the CCL19-rich maturation media, resulting in effective migration in vitro and in vivo [26]. We therefore rested the matured DCs overnight in fresh media before performing phenotype and migration analysis. The morphology of the DCs was determined using an EVOS XL Core microscope (Advanced Microscopy Group, Bothell, WA).

Flow cytometry

3-color flow cytometry was performed using an Accuri C6 flow cytometer. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-human CD80, CD40, CD3, CD40L, Phyocoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-human CD83, CD16, PE-Cy5-labeled anti-human CD8, CD4, CD19, CD56 and Allophycocyanin (APC)-labeled anti-human CD86 were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). APC-labeled anti-human CCR7 was obtained from R&D systems. PE-labeled MART-1(ELAGIGILTV) tetramer was purchased from Beckman Coulter (Immunomics, Fullerton CA). Cells were transferred to a V-bottom 96-well plate and washed with FACS buffer (PBS/0.5%BSA/0.1% Azide). Cells were incubated for 45 minutes in the dark at RT. Following labeling, cells were washed twice and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4°C until analysis. Flow cytometry data was analyzed using FCS Express V3 software.

Chemotaxis

The analysis of DC migratory function was performed using a 24-well transwell system with 5 μm pore size polycarbonate filter (Corning Inc, Corning, NY). 1 × 105 differentially matured DCs were rested overnight to allow for re-expression of CCR7, as described above, loaded to the top chamber of the transwell system and allowed to migrate towards rCCL21 (100 ng/ml; Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) over a 3 hour period at 37°C. Following incubation, the migrated cells from the bottom compartment were collected, the total volume of the cell suspension was measured and the cells in 100 μl of the suspension were counted using an Accuri C6 flow cytometer. The total number of migrated cells was calculated and is represented as percentage migrated cells of total cells. The number of cells that migrated in response to media (IMDM-5%HS) alone was subtracted from the number of chemokine-specific migrated cells to correct for background migration.

ELISA analysis of IL-12p70 and CXCL10 production by the differentially-matured DCs

Differentially matured DCs were harvested and resuspended in IMDM supplemented with 5% human AB serum at 2 × 105 cells/ml. 100μl of DC suspension (2 × 104 DCs) were transferred to a flat-bottom 96 well plate and stimulated for 20-24 hours with 5 × 104 CD40L-transfected J558 cells (kind gift of Dr. P. Lane, Birmingham, UK). After incubation, supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C until analysis. IL-12p70 and CXCL10 analysis was performed as described above for IFNγand TNFα, using 2μg/ml primary Ab (mouse anti-human IL-12(p70), Thermo Scientific Pierce) and 0.5 μg/ml biotin-labeled Ab (rat anti-human IL-12(p70), Thermo Scientific Pierce) for IL-12p70 and 10 μg/ml primary Ab (rabbit anti-human IP-10, Peprotech) and 2.5 μg/ml biotin-labeled secondary Ab (rabbit anti-human IP-10, Peprotech) for CXCL10. HRP-conjugated streptavidin followed by TMB substrate development was used for analysis and the colorimetric reaction was stopped with 2% H2SO4 and measured at 450nm.

Isolation of naïve CD8+ T cells

For the induction of CTL responses, naïve CD8+ T cells (CD8+CD45RO−CD45RA+) were isolated from the CD14neg (lymphocyte) population by incubating the cells with anti-CD45RO-biotin Abs (StemCell Technologies Inc, Vancouver, Canada). Following incubation, cells were washed and incubated with tetrameric anti-biotin complex and CD8 T cell enrichment cocktail (StemCell). Cells were then incubated with magnetic colloid (StemCell) after which naïve CD8+ T cells were isolated using a magnetic column (StemCell).

CTL induction

For the induction of CTL responses from naïve CD8+ T cells, matured DCs were loaded with tumor-associated peptides (MART-126-35, gp100209-217, PAP-3135-143, and PSA2146-154; all were used at the concentration of 10 μg/ml) for 2 hours at 37°C in IMDM-5% human AB serum. Peptide-loaded DCs were co-cultured with autologous CD8+ T cells at a 1:10 ratio in 48 well plates for 12 days. CD8+ T cells were supplemented with rhIL-2 (20 U/ml) on day 4 and with rhIL-2 and rhIL-7 (5 ng/ml) on day 7 and day 9. Day 12 CD8+ T cells were analyzed for the presence of MART-1 specific CTLs or were stimulated with individual peptides for 24 hours for the analysis of the frequency of tumor-peptide specific CD8+ T cells by IFNγenzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using unpaired Student’s t test (2-tailed). P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Expanded lymphocytes rapidly produce DC maturation- and polarization-inducing factors upon restimulation

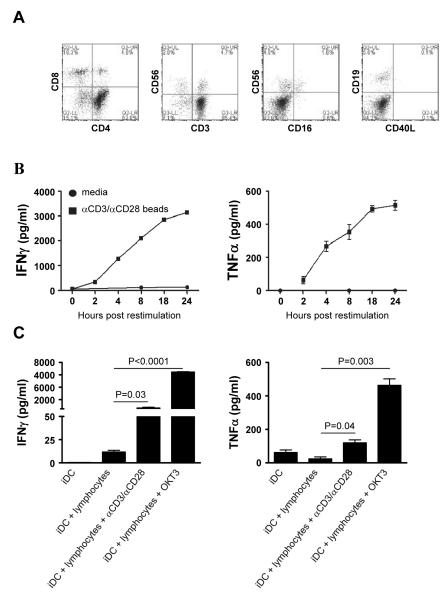

The combination of a DC maturation factor and IFNγhas been shown critical for the induction of polarized DC1s [27] with additional need for IFNαfor the complete development of polarized DC1s in the absence of FCS [18]. Since superantigen (SEB)-activated T cells secrete IFNγas well as TNFα and can use these factors to induce maturation and polarization of DCs in bovine-serum-supplemented cultures [23, 25], we tested whether activated bulk lymphocytes could be used to mature DCs in clinically-compatible protocols, involving serum-free media and clinically-relevant reagents. To test this, isolated lymphocytes were expanded for 6 days with αCD3 and αCD28 beads and analyzed to determine which cells were present. As expected, the expanded lymphocyte cultures consisted of mostly CD4+ T cells (~65%) and CD8+ T cells (~20%) while there were only low percentages (~5%) of NK cells and B cells present (Fig.1A).

Figure 1. Ex vivo-expanded lymphocytes rapidly produce IFNγand TNFαupon restimulation.

Isolated lymphocytes were expanded for 7 days with αCD3- and αCD28-coated beads. A) The phenotype of day 7 expanded lymphocytes was determined by flow cytometry. B) Day 7 expanded lymphocytes were harvested and either cultured in the absence of additional stimulation (circles) or restimulated (squares). At the indicated times, supernatants were collected to determine the secretion of IFNγ(left) and TNFα (right). C) Autologous day 5 iDCs were cultured in the presence of the day 7 expanded lymphocytes in the presence or absence of the indicated stimuli. After 24 hours of co-cultures, supernatants were collect and the production of IFNγ(left) and TNFα(right) was determined. Data shown from one of at least 2 independent experiments that yielded similar results.

The acquisition of high IL-12p70 producing ability by monocyte-derived DCs and counteracting DC exhaustion requires IFNγsignaling during maturation [27]. To test whether the expanded lymphocytes were able to mature DCs and prime them for high IL-12p70 production, we restimulated day 6 expanded lymphocytes with αCD3/CD28 beads and analyzed cytokine secretion at various times after re-stimulation. As shown in figure 1B, the restimulated lymphocytes started producing both IFNγ(left panel) and TNFα(right panel) within 2 hours of restimulation and continued to secrete these cytokine up to at least 24 hours after restimulation.

Since the expanded lymphocytes rapidly produced high amounts of both IFNγand TNFαupon restimulation, we analyzed the ability of expanded lymphocytes to induce maturation and polarization of immature autologous DCs. For this, monocytes were isolated and cultured for 5 days in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 to generate immature DCs (iDCs). The co-cultures of iDC with expanded lymphocytes in the absence of a TCR stimulus did not result in any IFNγor TNFαsecretion by the lymphocytes (Fig 1C). In contrast, when a TCR stimulus was added (i.e. αCD3/CD28 beads or soluble OKT3), the lymphocytes secreted both these cytokines (Fig. 1C).

Restimulated lymphocytes from healthy donors and melanoma patients induce DC maturation and polarization

In order to test whether the expanded and re-activated lymphocytes were able to induce the maturation of autologous iDC, we analyzed the morphology and phenotype of 24 hours matured DCs. As seen in figure 2A, DCs matured by re-activated lymphocytes or by the supernatant of 24 hour re-activated lymphocytes had a distinct morphology compared to iDCs or mature PGE2-matured ”standard” DCs (sDC; matured in the presence of recombinant cytokines and PGE2) [28] (Fig 2A). To verify the maturation status of the DCs, we analyzed the expression of co-stimulatory molecules by the DCs. DCs exposed to restimulated lymphocytes had increased expression of the co-stimulatory molecules and maturation-associated markers CD83, CD80, CD86 and CD40 compared to iDC and DCs co-cultured with lymphocytes in the absence of activation stimuli (Figure 2B and 2C).

Figure 2. Restimulated expanded lymphocytes or supernatant induce the maturation of autologous DCs and primes them for high IL-12p70 and CXCL10 production.

iDC were cultured for 24 hours with autologous day 7 expanded lymphocytes in the presence or absence of the indicated stimuli or with supernatant from 24 hours restimulated lymphocytes. A) After 24 hours, the morphology of the DCs was analyzed using bright field microscopy. The morphology of lymphocyte-matured DCs was compared with that of iDCs and with that of DCs exposed to the non-polarizing maturation-inducing cytokine cocktail (PGE2-matured sDC: IL1β, TNFα, IL-6 and PGE2). B) 24 hour matured DCs were collected, washed and rested overnight at 37°C in fresh media to remove any CCL19 produced during maturation and allow for re-expression of chemokine receptor CCR7 on the cell surface [26] (see M&M). After resting, the phenotype of the DCs was determined by flow cytometry. C) Average Mean Fluorescence Intensity expression of DC maturation markers of 3-5 individual experiments. D-E) 24 hour matured DCs were collected, washed and subsequently cultured for 24 hour with CD40L-expressing J558 cells (2×104 DC: 5×104 J558). After co-culture, supernatant was collected and analyzed for the presence of (D) IL12p70 and (E) CXCL10. Data shown are representative results from at least 2 independent experiments. F) Comparison of average of Mean Fluorescence Intensity of DC maturation associated markers on lymphocyte-matured DCs from 4 healthy donors with those of 3 melanoma patients. G) Comparison of IL-12p70 production by immature and lymphocyte-matured DCs from healthy donors (4) and melanoma patients (3) after 24 hours of CD40L stimulation.

Lymphocyte-matured DCs also had elevated levels of the lymphoid-homing chemokine receptor CCR7, which allows for the migration of mature DCs to the lymphoid organs. Supernatant-matured DCs showed a mixed phenotype with a population of cells having an immature phenotype (CD83low CCR7low) and another population being mature (CD83high CCR7high) (Fig. 2B and 2C).

The induction of Th1 and cytolytic CD8+ T cell (CTL) responses requires the secretion of IL-12p70 by DCs during the priming of naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [29]. Upon interaction with Ag-presenting mature DCs, CD4+ T cells up-regulate the expression of CD40L, which interacts with CD40 on the DCs and induces IL-12p70 secretion. To determine the ability of the differentially matured DCs to produce IL-12p70, we activated them for 24 hours with CD40L-transduced J558 cells, as a surrogate for CD40L-expressing CD4+ T cells [30]. As shown in Figure 2D, while iDCs and PGE2-matured sDCs produce only low levels of IL-12p70, DCs matured by restimulated lymphocytes or supernatant from restimulated lymphocytes have an elevated ability to secrete IL-12p70.

It has been shown that the optimal induction of Th1 responses by at least mouse DC vaccines relies on the secretion of CXCL10/interferon inducible protein 10 (IP-10) by mature DCs, which retains Th1 cells in the T cells area of the lymph nodes [31, 32]. To determine if the lymphocyte-matured DCs were able to secrete CXCL10, we co-cultured 24 hour matured DCs with CD40L-expressing J558 cells and determined the levels of CXCL10 in the supernatant after 24 hours. As shown in Fig 2E, iDC and PGE2-matured sDCs lacked production of CXCL10 while both the supernatant- and lymphocyte-matured DCs produced high levels of the CXCL10.

In order to test the feasibility of using autologous lymphocytes to induce the maturation of DCs obtained from cancer patients, we compared the maturation- and polarization status of DCs from healthy donors with that of DCs derived from melanoma patients. Restimulation of patients’ lymphocytes resulted in the secretion of similar levels of IFNγand TNFα with similar kinetics (compare Fig 1B and Supplemental Figure 1A). Following co-culture of autologous lymphocytes with iDCs in the presence of a TCR stimulus the DCs from healthy donors and from melanoma patients showed similar levels of up-regulation of co-stimulatory molecules and maturation associated markers (Fig 2F). Furthermore, CD40L stimulation of matured DCs from healthy donors and melanoma patients in both cases resulted in the elevated secretion of IL-12p70. There was no significant difference in IL-12 production between DCs from healthy donors and those obtained from PBMCs from melanoma patients (Fig 2G).

Lymphocyte supernatant-matured DCs migrate in response to CCL21

For clinical applications, the use of co-cultures of DCs and lymphocytes in the presence of TCR stimuli would be undesirable unless the DCs are subsequently separated from the poly-clonally-activated lymphocytes. Therefore, the use of supernatant-matured DCs may be more feasible for clinical applications. For this reason, we decided to focus on these cells for the subsequent experiments. Also, since there was no difference between DCs from healthy donors and from melanoma patients, we only used DCs from healthy donors for the remaining experiments.

Since the ability of mature DCs to migrate into lymph nodes is dependent on the expression of the lymphoid-homing chemokine receptor CCR7 [33, 34], the elevated expression of CCR7 on supernatant-matured DCs prompted us to determine their capacity to migrate in response to CCL21, the chemokine involved in attracting DCs to lymph nodes [35]. Using a transwell system we found that, in contrast to immature DCs, PGE2-matured sDCs migrated efficiently towards CCL21. Supernatant-matured DCs also migrated towards CCL21 albeit to a lesser extent than the cytokine-matured PGE2-matured sDCs (Fig 3), which correlates with the difference observed in surface expression of CCR7 (Fig. 2B).

Figure 3. Supernatant-matured DCs efficiently migrate in response to CCL21.

24 hour matured DCs were collected, washed and rested overnight at 37°C. After resting, DCs were placed in the top chamber of a transwell system and allowed to migrate for 3 hours towards CCL21 (in the bottom chamber) in a chemotaxis assay. Following incubation, the migrated cells in the bottom chamber of the transwell were collected and counted using a flow cytometer (see M&M). Migrated cells are represented as percentage of total cells. Migrated cells were counted twice and data is shown as mean +/− SD. Data shown are representative results from 2 independent experiments.

Lymphocyte supernatant-matured DCs induce strong anti-tumor peptide CTL responses

Since the DCs matured by supernatant from restimulated lymphocytes showed a distinctly-activated phenotype, we compared the ability of the supernatant-matured DCs to induce Ag-specific CTL responses with that of the PGE2-matured sDCs. DCs from a healthy HLA-A2+ donor were matured for 24 hours and loaded with a panel of 4 peptides (MART-1, gp100, PSA2, PAP-3) that are associated with different cancers (melanoma and prostate cancer) and used to prime autologous naïve CD8+ T cells. As shown in Figure 4A, peptide-loaded supernatant-matured DCs generated a similar expansion of MART-1-specific CD8+ T cells as the PGE2-matured sDC. The CD8+ T cells were then tested for their ability to recognize the individual peptides in an IFNγ-ELISPOT, which has been shown to be a good correlate of CTL function [36]. Naïve CD8+ T cells primed by peptide-loaded supernatant-matured DCs induced strong IFNγresponses against all 4 peptides, in contrast to naïve CD8+ primed by peptide-loaded PGE2-matured sDC (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Tumor-peptide-loaded supernatant-matured DCs induce strong anti-tumor CTL responses from autologous naïve CD8+ T cells.

24 hour-matured DCs (supernatant-matured or PGE2-matured sDC) from healthy donors were collected, washed and loaded for 2 hours with tumor peptides (MART-1, gp100, PAP3, and PSA2). Following peptide loading, DCs were cultured with autologous naïve CD8+ T cells at a 1:10 ratio. A) On day 12, CD8+ T cells were collected and the percentage of MART-1-specifc CD8+ T cells was determined by tetramer staining. B) Day 12 CD8+ T cells were collected, washed and used in a 24 hour IFNγ-ELISPOT analysis against tumor-peptides. Data are shown as mean +/− SEM of triplicate spot counts of one of 3 independent experiments that yielded similar results.

DISCUSSION

The ability of dendritic cells to induce strong adaptive immune responses has resulted in the use of DCs to treat malignancies in clinical trials. Since the generation of clinically-approved DCs requires the use of expensive cGMP cytokines, we analyzed the possibility of using activated lymphocytes to mature and polarize autologous iDC. We found that re-stimulation of expanded lymphocytes resulted in rapid secretion of inflammatory cytokines IFNγand TNFα, which led to type-1 polarization of iDCs. These lymphocyte-matured DCs were able to migrate in response to the lymphoid-homing chemokine CCL21 and, when loaded with peptides, prime naïve CD8+ T cells for strong anti-tumor peptide responses.

Animal studies and in vitro studies have shown that the ability to induce strong anti-tumor responses is dependent on the inflammatory cytokine IL-12 [13, 37]. Currently, the use of a mixture of IL-1β, IL-6, TNFαand PGE2 for the maturation of DCs is commonly used in the preparation of DCs for vaccinations. As we present here and have shown before, these cells have a limited IL-12 production capacity compared to type-1 polarized DCs and the use of these “exhausted” DCs as cancer vaccines in clinical trials might be a possible explanation for the lack of clinical responses in these trials. In contrast, the use of type-1 polarized DCs that have a high IL-12 production upon CD40L ligation [18] have been shown to be very effective in the treatment of malignant gliomas [17].

The ability of monocyte-derived DCs to produce high levels of IL-12 requires maturation in the presence of exogenous inflammatory factors, mimicking the conditions of acute (e.g. viral) infection [19, 27, 29]. It is known that activated lymphocytes are able to produce such inflammatory signals when interacting with Ag-presenting DCs. Naïve CD8+ T cells help CD40L-expressing CD4+ T cells, by producing IFNγand TNFα[23]. As shown here, this ability of lymphocytes to produce cytokines that induce type-1 polarization of (autologous) iDCs could be used to circumvent the need for expensive cGMP cytokines for the generation of clinically applicable DCs.

It was recently shown in a mouse model, that the ability of DCs to produce CXCL10/IP-10 at a tumor site allows them to attract effector T cells [31]. This ability allowed for enhanced anti-tumor responses and increased survival. Furthermore, the CXCL10 producing ability of DCs was shown to be pivotal for retaining Th1 cells in the T cell areas of the lymph nodes for optimal induction of Th1-mediated immune responses [32]. Unlike the PGE2-matured sDCs, supernatant- and lymphocyte-matured DCs were able to secrete high levels of CXCL10.

The presence of non-matured DCs in the supernatant-matured DCs may indicate that the soluble factors in the supernatant were less concentrated compared to the DC-lymphocyte co-cultures due to the proximity of secretion of the factors. Since the DCs that did not mature with the supernatant are still immature (and not partially matured) the involvement of surface molecule interaction in the DC maturation is unlikely.

The ability of DCs to migrate in response to lymph node-homing chemokines is a key feature of matured DCs and required for induction of T cell responses. Although DCs matured in the presence of PGE2 have a high expression of the lymph node homing chemokine receptor CCR7, the DC1s induced by restimulated lymphocytes (or their supernatants) also acquire CCR7 expression (and enhance its expression upon prolonged culture) and were able to migrate towards CCL21 in a transwell system. While supernatant-matured DCs contained both mature and non-matured cells, the expression of CCR7 is only observed on the matured (CD83+) population. The lower migration of these cells, when compared to PGE2-matured sDCs, correlates with the mixed character of the supernatant-matured DC population. We anticipate that a subcutaneous or intradermal application of such cells in clinical settings would result in the CCR7+ subset of DCs to migrate to the lymph nodes to interact with naïve and memory T cells, while the CCR7− iDCs are more likely to stay at the site of injection, interacting with effector- and effector-memory-type T cells. The presence of iDCs at the peripheral effector site could be beneficial since it has been shown that in the presence of tumor cells, iDCs protect tumor-specific CTLs from tumor-mediated activation-induced cell death (AICD) [38]. The iDC at the site of injection could also take up tumor-Ag and possibly continue to infiltrate the nodes due its continued process of maturation following the injection and the inflammatory milieu at the effector site. However, the injection of Ag-loaded iDCs has also been linked to Ag-specific inhibition of CTL functions [39], suggesting the need for optimization of DC maturation protocols. In regard of this, we have previously shown that in media without FCS the induction of type-1 polarized DCs could be enhanced by the addition of IFNα[18]. Since IFNα(Intron A) is relatively inexpensive, the addition of IFNαto optimize the DC maturation by supernatant from restimulated lymphocytes would not greatly increase the production costs. An alternative approach to further enhance the maturation status of the lymphocyte-matured DCs may be the addition of TLR ligands, such as poly-I:C used in our earlier studies with cytokines or NK cells [18].

Whether the same protocol can be used for the large scale production of type-1 polarized DCs in cancer patients still needs to be verified. Our preliminary comparison between DCs from healthy donors and melanoma patients show the elevation of the maturation status and priming for elevated of IL-12 production, independently on the source of the cells (Figure 2F, 2G and supplemental figure 1). Since T cells constitute high proportion in PBMCs and can also be efficiently expanded using CD3/CD28 beads (available as clinical grade reagent), the current method is likely to generate sufficient numbers of DCs needed for repetitive cycles of vaccination. Importantly for the clinical application of this method, we have shown the feasibility of using the cell-free supernatants from expanded T cells, eliminating the logistic concerns related to the presence of T cells in DC preparations, and the risk associated with the contact of immature DCs with T cells , which can lead to DC killing or suppression [25, 36, 40].

While the proposed approach is likely to reduce the overall cost of generation of type-1 polarized DCs, due to the elimination of the expensive recombinant cGMP cytokines, these advantages need to be balanced against the higher complexity of the whole process of DC1 generation, which involves an additional step of T cell expansion and generation of T cell conditioned media, and need to decide if the quality control process may need to include additional T cell-relevant variables, apart from the quality of the final DC product. However, since the times of T cell expansion and generation of immature DCs can at least partially overlap, the overall duration of generating polarized DC1s may be comparable to the process involving recombinant cytokines.

These data show that activated lymphocytes can be used to induce maturation and priming of autologous DCs, that these DCs produce high levels of cytokines associated with type-1 polarization (IL-12p70 and CXCL10) and are efficient in inducing anti-tumor responses by naïve CD8+ T cells when loaded with peptides. The use of expanded lymphocytes could eliminate the use of expensive clinical grade cytokines and reduce the cost for generating DCs for immunotherapies.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Lymphocytes, or their supernatants induce maturation and type-1 polarization of DCs

Lymphocyte-matured DC1s produce IL-12p70 and CXCL10 upon subsequent CD40 ligation

Lymphocyte-matured DC1s showed enhanced CCR7 expression and migration to CCL21

Lymphocyte-matured DC1s induce CTLs against tumor-associated antigens

TNFα/IFNγ-secreting T cells limit the need for DC1-polarizing cytokines

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors like to thank Dr. Eva Wieckowski, Dr. Julie Urban and Jeffery Wong for their critical comments, stimulating discussions and technical help.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Regulation of T cell immunity by dendritic cells. Cell. 2001 Aug 10;106(3):263–266. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Nestle FO, Filgueira L, Nickoloff BJ, Burg G. Human dermal dendritic cells process and present soluble protein antigens. J Invest Dermatol. 1998 May;110(5):762–766. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kalinski P, Hilkens CM, Wierenga EA, Kapsenberg ML. T-cell priming by type-1 and type-2 polarized dendritic cells: the concept of a third signal. Immunol Today. 1999 Dec;20(12):561–567. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].de Jong EC, Smits HH, Kapsenberg ML. Dendritic cell-mediated T cell polarization. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005 Jan;26(3):289–307. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Steinman RM, Young JW. Signals arising from antigen-presenting cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 1991 Jun;3(3):361–372. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(91)90039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Langenkamp A, Messi M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Kinetics of dendritic cell activation: impact on priming of TH1, TH2 and nonpolarized T cells. Nat Immunol. 2000 Oct;1(4):311–316. doi: 10.1038/79758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Iwashita Y, Tahara K, Goto S, Sasaki A, Kai S, Seike M, Chen CL, Kawano K, Kitano S. A phase I study of autologous dendritic cell-based immunotherapy for patients with unresectable primary liver cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003 Mar;52(3):155–161. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0360-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nestle FO, Alijagic S, Gilliet M, Sun Y, Grabbe S, Dummer R, Burg G, Schadendorf D. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide- or tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1998 Mar;4(3):328–332. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, Redfern CH, Ferrari AC, Dreicer R, Sims RB, Xu Y, Frohlich MW, Schellhammer PF. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jul 29;363(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hsieh CS, Macatonia SE, Tripp CS, Wolf SF, O’Garra A, Murphy KM. Development of TH1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science. 1993 Apr 23;260(5107):547–549. doi: 10.1126/science.8097338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].DeBenedette MA, Calderhead DM, Tcherepanova IY, Nicolette CA, Healey DG. Potency of mature CD40L RNA electroporated dendritic cells correlates with IL-12 secretion by tracking multifunctional CD8(+)/CD28(+) cytotoxic T-cell responses in vitro. J Immunother. 2011 Jan;34(1):45–57. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181fb651a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003 Feb;3(2):133–146. doi: 10.1038/nri1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Butterfield LH, Gooding W, Whiteside TL. Development of a potency assay for human dendritic cells: IL-12p70 production. J Immunother. 2008 Jan;31(1):89–100. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318158fce0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee JJ, Foon KA, Mailliard RB, Muthuswamy R, Kalinski P. Type 1-polarized dendritic cells loaded with autologous tumor are a potent immunogen against chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Leukoc Biol. 2008 Jul;84(1):319–325. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Okada H, Kalinski P, Ueda R, Hoji A, Kohanbash G, Donegan TE, Mintz AH, Engh JA, Bartlett DL, Brown CK, Zeh H, Holtzman MP, Reinhart TA, Whiteside TL, Butterfield LH, Hamilton RL, Potter DM, Pollack IF, Salazar AM, Lieberman FS. Induction of CD8+ T-cell responses against novel glioma-associated antigen peptides and clinical activity by vaccinations with {alpha}-type 1 polarized dendritic cells and polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid stabilized by lysine and carboxymethylcellulose in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Jan 20;29(3):330–336. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mailliard RB, Wankowicz-Kalinska A, Cai Q, Wesa A, Hilkens CM, Kapsenberg ML, Kirkwood JM, Storkus WJ, Kalinski P. alpha-type-1 polarized dendritic cells: a novel immunization tool with optimized CTL-inducing activity. Cancer Res. 2004 Sep 1;64(17):5934–5937. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Paustian C, Caspell R, Johnson T, Cohen PA, Shu S, Xu S, Czerniecki BJ, Koski GK. Effect of multiple activation stimuli on the generation of Th1-polarizing dendritic cells. Hum Immunol. 2011 Jan;72(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Roses RE, Xu S, Xu M, Koldovsky U, Koski G, Czerniecki BJ. Differential production of IL-23 and IL-12 by myeloid-derived dendritic cells in response to TLR agonists. J Immunol. 2008 Oct 1;181(7):5120–5127. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.5120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gigante M, Mandic M, Wesa AK, Cavalcanti E, Dambrosio M, Mancini V, Battaglia M, Gesualdo L, Storkus WJ, Ranieri E. Interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha)-conditioned DC preferentially stimulate type-1 and limit Treg-type in vitro T-cell responses from RCC patients. J Immunother. 2008 Apr;31(3):254–262. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318167b023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ten Brinke A, Karsten ML, Dieker MC, Zwaginga JJ, van Ham SM. The clinical grade maturation cocktail monophosphoryl lipid A plus IFNgamma generates monocyte-derived dendritic cells with the capacity to migrate and induce Th1 polarization. Vaccine. 2007 Oct 10;25(41):7145–7152. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mailliard RB, Egawa S, Cai Q, Kalinska A, Bykovskaya SN, Lotze MT, Kapsenberg ML, Storkus WJ, Kalinski P. Complementary dendritic cell-activating function of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells: helper role of CD8+ T cells in the development of T helper type 1 responses. J Exp Med. 2002 Feb 18;195(4):473–483. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kalinski P, Nakamura Y, Watchmaker P, Giermasz A, Muthuswamy R, Mailliard RB. Helper roles of NK and CD8+ T cells in the induction of tumor immunity. Polarized dendritic cells as cancer vaccines. Immunol Res. 2006;36(1-3):137–146. doi: 10.1385/IR:36:1:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Watchmaker PB, Urban JA, Berk E, Nakamura Y, Mailliard RB, Watkins SC, van Ham SM, Kalinski P. Memory CD8+ T cells protect dendritic cells from CTL killing. J Immunol. 2008 Mar 15;180(6):3857–3865. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Muthuswamy R, Mueller-Berghaus J, Haberkorn U, Reinhart TA, Schadendorf D, Kalinski P. PGE(2) transiently enhances DC expression of CCR7 but inhibits the ability of DCs to produce CCL19 and attract naive T cells. Blood. 2010 Sep 2;116(9):1454–1459. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-258038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Vieira PL, de Jong EC, Wierenga EA, Kapsenberg ML, Kalinski P. Development of Th1-inducing capacity in myeloid dendritic cells requires environmental instruction. J Immunol. 2000 May 1;164(9):4507–4512. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jonuleit H, Kuhn U, Muller G, Steinbrink K, Paragnik L, Schmitt E, Knop J, Enk AH. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandins induce maturation of potent immunostimulatory dendritic cells under fetal calf serum-free conditions. Eur J Immunol. 1997 Dec;27(12):3135–3142. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hilkens CM, Kalinski P, de Boer M, Kapsenberg ML. Human dendritic cells require exogenous interleukin-12-inducing factors to direct the development of naive T-helper cells toward the Th1 phenotype. Blood. 1997 Sep 1;90(5):1920–1926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cella M, Scheidegger D, Palmer-Lehmann K, Lane P, Lanzavecchia A, Alber G. Ligation of CD40 on dendritic cells triggers production of high levels of interleukin-12 and enhances T cell stimulatory capacity: T-T help via APC activation. J Exp Med. 1996 Aug 1;184(2):747–752. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fujita M, Zhu X, Ueda R, Sasaki K, Kohanbash G, Kastenhuber ER, McDonald HA, Gibson GA, Watkins SC, Muthuswamy R, Kalinski P, Okada H. Effective immunotherapy against murine gliomas using type 1 polarizing dendritic cells--significant roles of CXCL10. Cancer Res. 2009 Feb 15;69(4):1587–1595. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yoneyama H, Narumi S, Zhang Y, Murai M, Baggiolini M, Lanzavecchia A, Ichida T, Asakura H, Matsushima K. Pivotal role of dendritic cell-derived CXCL10 in the retention of T helper cell 1 lymphocytes in secondary lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2002 May 20;195(10):1257–1266. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hirao M, Onai N, Hiroishi K, Watkins SC, Matsushima K, Robbins PD, Lotze MT, Tahara H. CC chemokine receptor-7 on dendritic cells is induced after interaction with apoptotic tumor cells: critical role in migration from the tumor site to draining lymph nodes. Cancer Res. 2000 Apr 15;60(8):2209–2217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Understanding dendritic cell and T-lymphocyte traffic through the analysis of chemokine receptor expression. Immunol Rev. 2000 Oct;177:134–140. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.17717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Britschgi MR, Favre S, Luther SA. CCL21 is sufficient to mediate DC migration, maturation and function in the absence of CCL19. Eur J Immunol. 2010 May;40(5):1266–1271. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yang DH, Kim MH, Lee YK, Hong CY, Lee HJ, Nguyen-Pham TN, Bae SY, Ahn JS, Kim YK, Chung IJ, Kim HJ, Kalinski P, Lee JJ. Successful cross-presentation of allogeneic myeloma cells by autologous alpha-type 1-polarized dendritic cells as an effective tumor antigen in myeloma patients with matched monoclonal immunoglobulins. Ann Hematol. 2011 Dec;90(12):1419–1426. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1219-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Muller J, Feige K, Wunderlin P, Hodl A, Meli ML, Seltenhammer M, Grest P, Nicolson L, Schelling C, Heinzerling LM. Double-blind placebo-controlled study with interleukin-18 and interleukin-12-encoding plasmid DNA shows antitumor effect in metastatic melanoma in gray horses. J Immunother. 2011 Jan;34(1):58–64. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181fe1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mailliard RB, Lotze MT. Dendritic cells prolong tumor-specific T-cell survival and effector function after interaction with tumor targets. Clin Cancer Res. 2001 Mar;7(3 Suppl):980s–988s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dhodapkar MV, Steinman RM, Krasovsky J, Munz C, Bhardwaj N. Antigen-specific inhibition of effector T cell function in humans after injection of immature dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2001 Jan 15;193(2):233–238. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Sato K, Tateishi S, Kubo K, Mimura T, Yamamoto K, Kanda H. Downregulation of IL-12 and a novel negative feedback system mediated by CD25+CD4+ T cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005 Apr 29;330(1):226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.