Abstract

Aims

The study evaluated the effectiveness of an 8-week combined group plus individual 12-step facilitative intervention on stimulant drug use and 12-step meeting attendance and service.

Design

Multisite randomized controlled trial, with assessments at baseline, mid-treatment, end of treatment, and 3- and 6-month post-randomization follow-ups (FU).

Setting

Intensive outpatient substance treatment programs.

Participants

Individuals with stimulant use disorders (n = 471) randomly assigned to treatment as usual (TAU) or TAU into which the STAGE-12 intervention was integrated.

Measurements

Urinalysis and self-reports of substance use and 12-step attendance and activities.

Intervention

Group sessions focused on increasing acceptance of 12-step principles; individual sessions incorporated an intensive referral procedure connecting participants to 12-step volunteers.

Findings

Compared to TAU, STAGE-12 participants had significantly greater odds of self-reported stimulant abstinence during the active 8-week treatment phase; however, among those who had not achieved abstinence during this period, STAGE-12 participants had more days of use. STAGE-12 participants had lower ASI Drug Composite scores at and a significant reduction from baseline to the 3-month FU, attended 12-step meetings on a greater number of days during the early phase of active treatment, engaged in more other types of 12-step activities throughout the active treatment phase and the entire FU period, and had more days of self-reported service at meetings from mid-treatment through the 6-month FU.

Conclusions

The present findings are mixed with respect to the impact of integrating the STAGE-12 intervention into intensive outpatient drug treatment compared to TAU on stimulant drug use. However, the results more clearly indicate that individuals in STAGE-12 had higher rates of 12-step meeting attendance and were engaged in more related activities throughout both the active treatment phase and the entire 6-month follow-up period than did those in TAU.

Twelve-step and mutual support groups represent important, readily available, and pervasive resources in substance abuse recovery (Humphreys, 1999; Kelly & Moos, 2003; Room & Greenfield, 1993). All 12-step programs (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, Cocaine Anonymous) provide mutual support for drug dependent individuals. Involvement in these programs is often incorporated into treatment programs for opiate (Gossop, Stewart, & Marsden, 2008), cocaine (Daley, Mercer, & Carpenter, 1999; Mercer & Woody, 1999; Rawson et al., 1995; Weiss et al., 2005; Wells, Peterson, Gainey, Hawkins, & Catalano, 1994), and methamphetamine dependence (Donovan & Wells, 2007; Fiorentine, 1999; Obert et al., 2000) as well as polydrug abuse (Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2000a; Laudet, Stanick, & Sands, 2007).

Recent studies have found a positive relationship between 12-step involvement and improvement on substance use outcomes for both alcohol and drug dependent individuals (Connors, Tonigan, Miller, & Project MATCH Research Group, 2001; Donovan, 1999; Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2000a; Gossop, et al., 2008; Kaskutas, 2009; McKay, Merikle, Mulvaney, Weiss, & Koppenhaver, 2001; McKellar, Stewart, & Humphreys, 2003; Morgenstern, Labouvie, McCrady, Kahler, & Frey, 1997; Tonigan, 2001; Tonigan, Connors, & Miller, 2003; Watson et al., 1997; Weiss, et al., 2005), even over extended periods ranging up to 16 years (Moos & Moos, 2005; Moos & Moos, 2006). Conversely, low and inconsistent involvement is associated with poorer outcomes (Fiorentine, 1999; Moos & Moos, 2004; Weiss, Griffin, Gallop, Onken, et al., 2000; Weiss, et al., 2005; Weiss et al., 1996).

Meeting attendance and involvement in 12-step activities, though related, appear to have different predictive abilities in relationship to subsequent substance use (Majer, Jason, Ferrari, & Miller, 2011; Weiss, et al., 2005). Increased frequency and consistency of meeting attendance is associated with greater benefit with respect to substance use outcomes than less frequent or inconsistent attendance (Caldwell & Cutter, 1998; Fiorentine, 1999; Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2000a; Kaskutas et al., 2005; Moos & Moos, 2004; Moos & Moos, 2005; Morgenstern, Kahler, Frey, & Labouvie, 1996; Weiss, Griffin, Gallop, Onken, et al., 2000). However, relative to attendance, involvement in 12-step recovery-oriented activities (e.g., reading 12-step literature; doing service at meetings, such as helping newcomers, setting up chairs, making coffee, cleaning up afterwards; having a 12-step sponsor; meeting with or calling sponsors or other 12-step group members) appears to better predict and is associated with better substance use outcomes for both alcoholics (Caldwell & Cutter, 1998; Gilbert 1991; McKellar, et al., 2003; Montgomery, Miller, & Tonigan, 1995; Subbaraman, Kaskutas, & Zemore, 2011) and cocaine abusers (Weiss, Griffin, Gallop, Onken, et al., 2000; Weiss, et al., 2005). As an example, 12-step meeting attendance did not predict subsequent cocaine use or the Drug Use Composite score on the Addiction Severity Index among cocaine dependent individuals, whereas higher levels and consistent patterns of involvement in 12-step activities and service were predictive of fewer days of cocaine use and lower Composite scores (Weiss, et al., 2005). Consistent with this, engaging in service activities was found to be a significant mediator of the relationship between a 12-step facilitative intervention and increased abstinence from alcohol and drugs while AA/NA/CA meeting attendance was not (Subbaraman, et al., 2011).

While a relatively large percentage of substance abusers entering treatment have attended a 12-step meeting in the past, there are high rates of dropout or inconsistent attendance among those who have (Godlaski, Leukefeld, & Cloud, 1997; Harris et al., 2003; Kelly & Moos, 2003; Rawson, Obert, McCann, Castro, & Ling, 1991; Weiss, et al., 1996). This may be particularly true for stimulant abusers (Rawson, et al., 1991; Weiss, Griffin, Gallop, Onken, et al., 2000; Weiss, et al., 1996). However, individuals who initiate 12-step involvement during treatment are significantly less likely to drop out of the 12-step program during the subsequent year (Kelly & Moos, 2003); there also appears to be an additive effect on abstinence rates for those who participate in 12-step programs while in treatment (Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2000a). These findings have led to recommendations that treatment programs emphasize the importance of mutual support groups, encourage 12-step group attendance and participation, and employ empirically supported approaches to facilitate engagement (Caldwell, 1999; Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2000a; Humphreys, 1999, 2003; Humphreys et al., 2004; Weiss, Griffin, Gallop, Luborsky, et al., 2000; Weiss, Griffin, Gallop, Onken, et al., 2000). However, interventions that are effective in increasing attendance may be insufficient to ensure active involvement. Individuals who attend 12-step meetings but have difficulty embracing key program aspects may need assistance that focuses more on 12-step practices and tenets rather than on meeting attendance (Caldwell & Cutter, 1998).

Referral by professionals, while common (Humphreys, 1997), is not always practiced in a manner that fosters client acceptance of 12-step groups (Caldwell, 1999). A number of interventions specifically designed to facilitate involvement in 12-step programs have been found to enhance attendance at and involvement in mutual support groups and result in significant and substantial reductions in substance use (Carroll et al., 2000; Carroll, Nich, Ball, McCance, & Rounsavile, 1998; Donovan & Floyd, 2008; Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2000a, 2000b; Humphreys, Huebsch, Finney, & Moos, 1999; Kaskutas, Subbaraman, Witbrodt, & Zemore, 2009; Ouimette, Finney, & Moos, 1997; Timko & DeBenedetti, 2007; Timko, DeBenedetti, & Billow, 2006; Weiss, et al., 2005). However, treatment programs are likely to find many previously evaluated 12-step facilitation interventions, such as employed in Project MATCH and the NIDA Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study (NCCTS), relatively lengthy and difficult to sustain in programs with reduced lengths of stay and within current reimbursement models. To make such interventions fit better within current constraints of clinical practice and reimbursement models, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration/Veterans Health Administration Workgroup on Substance Abuse Self-Help Organizations has recommended that briefer forms of 12-step facilitation should be developed and evaluated (Humphreys, 1999; Humphreys, et al., 2004).

One approach recommended for further study (Humphreys, 1999; Owen et al., 2003) is “systematic encouragement and community access” (Sisson & Mallams, 1981), which utilizes 12-step members as volunteers in a “buddy system” that provides a “bridge” between formal treatment and community 12-step programs. In this intensive referral procedure, the counselor supplements typical referral models (e.g., providing a list of meetings and encouraging attendance) with an in-session telephone call introducing the client to a current 12-step member who arranges to attend a meeting with him or her. Timko and colleagues (Timko & DeBenedetti, 2007; Timko, et al., 2006) evaluated a 3-session, individual intensive 12-step referral procedure in a two-site randomized trial with individuals entering outpatient substance abuse treatment. At the 12-month follow-up those in the intensive referral condition had significantly greater reductions on the Alcohol and Drug Use Composite scores of the Addiction Severity Index, significantly higher rates of abstinence from both alcohol and drugs, and greater engagement in 12-step activities than individuals who had received standard referral.

Several studies have demonstrated the feasibility and effectiveness of 12-step oriented interventions delivered in a group format (T.G. Brown, P. Seraganian, J. Tremblay, & H. Annis, 2002a; T.G. Brown, P. Seraganian, J. Tremblay, & H. Annis, 2002b; Kaskutas, et al., 2009; Wells, et al., 1994). Group based 12-step approaches appear to be enhanced further by the addition of individual sessions that reinforce and augment the group sessions (Crits-Christoph et al., 1999). A combination of individual plus group counseling is a common method of delivering care in outpatient treatment, particularly intensive outpatient care (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1994). Thus, such a format would be compatible with current clinical service delivery practices.

Miller identified Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF) therapy from Project MATCH and systematic encouragement as two empirically supported interventions (Owen, et al., 2003), and noted that treatment is the time to initiate them. Miller’s conclusions helped shape the present study, which evaluated the impact of a brief combined group and individual treatment approach for stimulant abusers, a population for whom effective pharmacological interventions are not yet available (Vocci & Ling, 2005 ), for which an expanded range of psychosocial interventions is needed to improve treatment outcomes (Vocci & Montoya, 2009 ), and for which emerging results suggest that adjunctive 12-step approaches may be effective (Crits-Christoph, et al., 1999; Donovan & Wells, 2007; Fiorentine & Hillhouse, 2000a; Weiss, et al., 2005; Wells, et al., 1994). Specifically, STAGE-12 (Stimulant Abuser Groups to Engage in 12-Step) was based on core therapy modules from the Project MATCH TSF therapy as modified for use with drug abusers (Baker, 1998; Carroll, et al., 1998) and delivered in a group format (Brown, et al., 2002a; Brown, et al., 2002b). Group sessions focused on conveying a basic understanding of 12-step practices and tenets and were augmented by three individual sessions integrating the intensive referral procedure (Timko & DeBenedetti, 2007; Timko, et al., 2006).

The study compared the extent to which the STAGE-12 intervention, integrated into treatment as usual (TAU), would lead to significantly greater reductions in stimulant drug use than TAU. It also examined the extent to which STAGE-12 increased self-help meeting attendance and involvement in recovery activities over and above that of clients receiving TAU.

METHODS

The study and its procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board (IRB), as well as the IRBs of the participating universities with which each of the clinical sites was affiliated. An independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board oversaw the conduct of the trial.

Participants

Participating clinical sites

Through a multi-staged, blinded rating process (Potter et al., 2011), 10 community-based treatment programs (CTPs) affiliated with the NIDA Clinical Trials Network (CTN) were selected from a pool of 30 programs that provided 5 to 15 hours of weekly psychosocial outpatient ambulatory care. The 10 selected CTPs provided a mean of 9.6 hours of treatment per week (SD = 2.85, ranging from 6–15 hours) for an average of 13. 5 weeks (SD = 5.12, ranging from 7.5–24 weeks). During the course of the study clients in participating CTPs typically attended 3 group sessions and one individual session per week. Five sites had predominantly cocaine clients, four had primarily methamphetamine clients, and one had a relatively equal mix of cocaine and methamphetamine clients.

Treatment Directors of the participating CTPs completed the Drug and Alcohol Treatment Program Inventory (DAPTI) (Peterson, Swindle, Paradise, & Moos, 1994; Swindle, Peterson, Paradise, & Moos, 1995), which assessed the extent to which CTPs endorsed a variety of therapeutic approaches. The three most prominently endorsed approaches were 12-step (Median = 5 on a scale from 1 = Not at all to 5 = Very much), cognitive-behavioral/relapse prevention therapy (Median = 4.5), and motivational interviewing (Median = 4). However, it appears that the programs are relatively eclectic in that they employ elements from a number of therapeutic approaches. The DAPTI also assessed the frequency with which participating CTPs emphasized 12-step oriented treatment goals. Helping clients accept recovery as a life-long process was the most highly rated of these goals (Median = 4 on a scale from 1 = None or very little focus to 4 = Primary focus of treatment). The two goals most consistent with the focus of the STAGE-12 intervention, appreciating the importance of regular 12-step meeting participation and committing to actively working the 12 steps, were both rated as being a considerable focus of treatment in the programs (Median = 3).

The project was implemented in two waves, with three sites beginning in February and the remaining seven beginning in November, 2008. The last subject was randomized on September 30, 2009.

Participating counselors

Study clinicians were drawn from existing credentialed CTP counseling staff who agreed to complete informed consent documents; complete counselor assessments; be randomly assigned to provide STAGE-12 or TAU only; implement the manual-guided STAGE-12 intervention and conform to restrictions placed on TAU; record their STAGE-12 sessions for fidelity rating; participate in supervision sessions; and complete process/adherence ratings. They also needed to have a working familiarity with 12-step recovery principles and mutual support programs that utilize them. Personal recovery status was not an inclusion factor. From a pool of 106 counselors meeting these criteria, two per site were randomly selected to provide STAGE-12. Twenty counselors and 10 on-site supervisors were initially selected. Additional STAGE-12 counselors (N = 4) and supervisors (N = 3) were added as replacements when needed. The remaining 82 unselected counselors continued as TAU counselors providing standard clinic care and did not provide additional data for the study.

Two centralized 2-day national training seminars were conducted for STAGE-12 counselors and supervisors; replacement counselors and supervisors were trained locally using standardized materials developed for the national trainings. Trainings comprised a review of basic 12-step principles, topic-by-topic review of the STAGE-12 manual, several role play and practice exercises, discussion of case examples, and rehearsing strategies for challenging cases. Following training, STAGE-12 counselors were certified to see trial participants only after independent raters had evaluated audiotapes of 3 training cases, (each consisting of 1 individual and 2 group sessions) to reach a criterion threshold. Every STAGE-12 group and individual session was audio recorded throughout the trial; on-site supervisors and centralized raters reviewed a random selection of 20% for both fidelity monitoring and clinical supervision. Counselors with inadequate fidelity completed additional training and underwent more frequent monitoring and supervision until they met the fidelity requirement.

Participating stimulant abusers

Potential participants were approached about the study and recruited upon admission into participating intensive outpatient programs. Eligibility criteria included: 1) age 18 years or older; 2) in outpatient treatment at participating CTP; 3) stimulant drug use within the past 60 days (or within the past 90 days if incarcerated during the past 60 days); 4) DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for current (within the past 6 months) abuse or dependence on a stimulant drug as primary or secondary drug of abuse; 5) able to provide consent and willing to provide information about alcohol and drug use, be randomly assigned to a treatment condition, and be audio-recorded during group and individual counseling sessions. Exclusion criteria included: 1) needing detoxification for opiate withdrawal; 2) seeking detoxification only, methadone maintenance, or residential/inpatient treatment; 3) a medical or psychiatric condition that would make participation hazardous; 4) incarcerated more than 60 days within the 90 days prior to baseline; or 5) had pending legal action that would prohibit participation in the study.

A total of 471 individuals meeting these criteria were recruited and randomized from the 10 participating CTPs. The number of participants randomized per CTP ranged from 36 to 80 (Mean = 47.1, Median = 41.5). Utilizing a centralized randomization procedure, 237 participants were assigned to TAU and 234 to STAGE-12. Participants were assessed at baseline, week 4 (mid-treatment), week 8 (end of treatment), and at 3- and 6-month post-randomization follow-ups. Individuals were reimbursed $30 for each completed assessment plus an additional $40 bonus if all assessments were completed.

Treatment Conditions

TAU

The CTPs’ standard outpatient psychosocial treatment (minimum of 5–15 hours weekly) constituted TAU. While many CTPs promote a 12-step treatment philosophy and encourage clients to become involved in 12-step activities, these efforts typically are not applied in a structured or systematic manner (Carroll, et al., 2000; Humphreys, 1999; Humphreys & Moos, 2007; Humphreys, et al., 2004; Timko, et al., 2006). Although TAU counselors might discuss 12-step meetings with clients, they were prohibited from providing participants any of the components of the STAGE-12 intervention, including project-prepared handouts, reading material, or journals. TAU clients also were not connected to a community-based 12-step volunteer and did not receive lists of potential sponsors from TAU counselors.

STAGE-12

STAGE-12 is a manualized, combined group plus individual intervention (Baker, Daley, Donovan, & Floyd, 2007; Daley, Baker, Donovan, Hodgkins, & Perl, 2011). It consists of five 90-minute group sessions adapted from Twelve-Step Facilitation Therapy for Drug Abuse and Dependence (Baker, 1998; Carroll, et al., 1998) and for delivery in a group format (Brown, et al., 2002a; Brown, et al., 2002b) plus three complementary individual sessions. The use of a combined group plus individual approach, as well as the use of open-ended groups with rolling admission, was informed by the results of surveys of CTN-affiliated outpatient programs during the design of the study (Donovan et al., 2011). The STAGE-12 sessions were integrated into rather than being in addition to the standard TAU, substituting for three individual and five group TAU sessions; thus the amount of treatment available to clients over the active treatment period of the study was comparable across conditions within a CTP.

STAGE-12 group sessions emphasized the primary goal of TSF, to promote abstinence from substances by helping participants better understand and incorporate the core principles of 12-Step approaches, facilitating acceptance and surrender of their addiction, and encouraging active involvement in 12-step meetings and related activities. The group sessions encompassed five topics from the TSF manual: Acceptance (Step 1); People, places, & things (habits, routines, and relapse triggers); Surrender (Steps 2 & 3); Getting active in 12-step programs; and Managing negative emotions (HALT: Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired). The group counselor provided education, facilitated group discussions of session topics, and was supportive and encouraging to participants.

The three individual sessions included adaptations of the introductory and termination sessions from the TSF manual and incorporated an intensive referral procedure (Timko, et al., 2006). A major portion of the first individual session was devoted to the intensive referral process, which emphasized active participation in 12-step activities as a primary means to recovery and focused primarily on facilitating participants’ attendance at 12-step groups. Consistent with AA’s Bridging the Gap program (Alcoholics Anonymous, 1991), the STAGE-12 counselor and participant worked collaboratively to link the participant with a 12-step volunteer from the community to arrange to attend a 12-step meeting together (Timko, et al., 2006). The content of the second session varied, depending on whether the participant had attended a 12-step meeting since the first session. If so, the participant’s reactions to the meeting were discussed; if not, the session focused on perceived and actual barriers to meeting attendance and a 12-step volunteer was again contacted to arrange to attend a meeting together. The third session incorporated components from the termination session from the TSF manual, reviewed recovery assignments and participant experiences, and focused on changes in participants’ views of addiction and 12-step programs over the course of treatment. It focused on finding a sponsor if a meeting had been attended since the last session or on linking with a 12-step volunteer if a meeting had not been attended. Barriers to participation were reviewed and goals and plans for the future were discussed.

STAGE-12 group and individual sessions were augmented by between-session “homework” tasks. These included reading literature (e.g., excerpts from AA’s Big Book, NA’s Basic Text); “recovery tasks” (e.g., contacting a sponsor, doing service work at a meeting,); attending different kinds of 12-step meetings each week; and keeping a journal to document 12-step group attendance and participation, reactions to meetings and other assigned recovery tasks, or barriers to attendance if the client did not attend a meeting. Journal entries were reviewed at the beginning of each individual session, while the other activities were reviewed during the check-in at group sessions.

Measures

Participant Baseline Background Measures

Demographics

This was collected from a standard CTN demographics form and the demographics section of the Addiction Severity Index - Lite (ASI-Lite) (McLellan, Alterman, Cacciola, Metzger, & O’Brien, 1992).

Substance use diagnoses and problem severity

DSM-IV substance use disorder diagnoses were derived from the DSM-IV Criteria Checklist (DSM-IV Checklist) interview (Hudziak et al., 1993). The ASI Drug Use Composite score, ranging between 0 (no endorsement of any problems) and 1 (maximal endorsement of all problems), measured problem severity and perceived need for treatment during the 30-days preceding the assessment.

Twelve-step experiences

The Twelve-Step Experiences and Expectations (TSEE), developed for the present project, is a brief measure of participants’ prior experiences with 12-step groups as well as the likelihood of and anticipated benefits from 12-step group involvement during this treatment episode. The Survey of Readiness for Alcoholics Anonymous Participation (SYRAAP) assessed issues related to ambivalence and readiness to engage in 12-step activities, including the perceived benefits of and perceived barriers to involvement (Kingree, Simpson, Thompson, McCrady, & Tonigan, 2007; Kingree et al., 2006 ).

Substance Use Outcome Measures

The primary outcome variable was the number of days of self-reported stimulant drug use within 30-day periods across the 6-month post-randomization period as assessed by the Substance Use Calendar (SUC), a calendar-based assessment similar to the timeline follow-back procedure (Fals-Stewart, O’Farrell, Freitas, McFarlin, & Rutigliano, 2000; Sobell & Sobell, 1992). These data were collected at baseline, week 4 (mid-treatment), week 8 (end-of-treatment), and at 3- and 6-month post- randomization follow-ups.

Urine Drug Screens were collected at the same time points as the SUC. Urinalyses positive for stimulant drugs served as a secondary outcome measure, as did the Drug Use Composite score from the ASI-Lite, collected at baseline and the 3- and 6-month post-randomization follow-ups.

Twelve-Step Outcome Measures

Attendance at 12-step/mutual support meetings was assessed using the calendar-based SUC, similar to the procedure used by Walitzer and colleagues (Walitzer, Dermen, & Barrick, 2009 ). The Self-Help Activities Questionnaire (SHAQ), which was the primary measure of 12-step attendance and involvement in the NIDA Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study (Weiss, et al., 1996), assessed the number of days in the preceding 30-day period on which group meetings (both 12-step and non-12-step) had been attended, as well as participation in 12-step/mutual support activities, including the number of days participants performed service (e.g., setting up, making coffee), talked at meetings, met with sponsors or other group members outside of meetings, phoned or had been phoned by sponsors or other group members, read 12-step recovery literature, and worked on any of the 12 steps.

Statistical Analysis Approach

Count data and appropriate statistical model for the primary outcome analysis

Distributional characteristics of the primary outcome of stimulant use indicated considerable post-baseline zero-inflation, over-dispersion and a non-linear trend (i.e., decreasing in value from pre-baseline to mid-treatment and increasing from mid-treatment to end-of-treatment). Based on these considerations, the statistical model utilized was a zero-inflated negative binomial random-effects regression model, with a pre-treatment covariate. With the repeated measures aspect of the outcome assessment, the random effects model is considered appropriate to account for variation within subjects across time. Additionally, the average of measures within the two pre-baseline time windows (60–90 days and 30–60 days prior to baseline) and one baseline measure (0–30 days pre-treatment) provided a more normally distributed, continuous covariate. Using these allowed inclusion of pre-treatment information into the model and avoidance of potential confounding and interpretive problems associated with alternative procedures such as spline regression or inclusion of orthogonal polynomials. Both of these latter approaches would result in a model with two interaction terms consisting of the same main effect of treatment to account for the non-linear trend (Hilbe, 2008).

However, use of this average would require that at least one value be available at any of the post-baseline time points for the analysis. Of the 471 individuals randomized to treatment, 50 subjects (TAU, N = 20, STAGE-12, N = 30) did not have any post-baseline measures and were therefore eliminated from the statistical analysis of the primary outcome and some of the secondary outcomes. There were no inordinate differences between the subjects included and the 50 excluded from the analyses on demographic and baseline variables related to substance use. Additionally, the average of the two pre-baseline and one baseline measure for the primary outcome was not statistically different (t469 = 0.55, p = .58) between those included (Mean = 9.56, SD = 7.56, N = 421) and those excluded from the analyses (Mean = 8.94, SD = 6.88, N = 50).

The statistical approach for the primary outcome is a mixture model with a logistic part for assessing zero-inflation and a negative-binomial part for the over-dispersed count data. Interpretation of results are based on the values and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the odds ratios (ORs, logistic part for abstinence) and incidence rate ratios (RRs, negative binomial part for count or days of stimulant use) at each post-baseline time point, with interaction effects calculated by algorithms provided by Hilbe (Hilbe, 2008).

Statistical models for secondary outcomes

Most of the secondary outcomes are considered to be count data, with the exception of the binary urine screen data and the continuous ASI Drug Use Composite scores greater than 0. In analyses of secondary outcomes where there is count data and no zero-inflation, a regular negative binomial with over-dispersion, or Poisson with equidispersion, random-effects regression model was used. Statistical interpretation of these count models was based on the incidence rate ratios and their 95% CIs.

All models were estimated with the SAS (2008) program and the NLMIXED procedure.

RESULTS

Participant Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 presents participant demographic and baseline drug-related characteristics; Table 2 presents data related to prior 12-step involvement, expectancies, and readiness to engage in 12-step groups. Participants were predominantly non-Hispanic Caucasian females, with a substantial representation of Black/African American individuals, with a 12th grade equivalent education. Approximately half the sample had never been married, with another third separated or divorced. The sample was divided approximately into thirds with respect to employment: employed full time, employed part time, and unemployed.

Table 1.

Participant Baseline Demographic and Substance Use Information

| Characteristics | TAU (N = 237) | STAGE-12 (N = 234) | Total (N = 471) | Statistical Test of Difference in TAU & Stage-12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Percent female | 55.7 | 62.0 | 58.8 | Z=1.389 (p=.16) |

|

| ||||

| Percent Hispanic/Latino | 6.3 | 6.4 | 6.4 | Z=0.044 (p=.96) |

|

| ||||

| Percent Caucasian | 49.0 | 46.2 | 47.6 | Z=0.607 (p=.54) |

|

| ||||

| Percent Black/African American | 35.0 | 37.6 | 36.3 | Z=0.586 (p=.56) |

|

| ||||

| Mean age (SD.) | 38.5 (9.4) | 38.2 (10.0) | 38.4 (9.7) | t(469)=0.23 (p=.81) |

|

| ||||

| Mean years of education (SD) | 12.1 ( 1.6) | 12.2 (1.7) | 12.2 (1.6) | t(468)= −1.07 (p=.28) |

|

| ||||

| Percent employed: | ||||

| Full Time | 37.1 | 35.5 | 36.3 | Z=0.360 (p=.72) |

| Part Time | 23.6 | 24.8 | 24.2 | Z=0.303 (p=.76) |

| Unemployed | 35.4 | 34.2 | 35.0 | Z=0.273 (p=.79) |

|

| ||||

| Percent marital status: | ||||

| Married | 9.8 | 15.5 | 12.6 | Z=1.862 (p=.06) |

| Separated/Divorced | 34.3 | 34.3 | 34.3 | Z=0.000 (p=1.00) |

| Never Married | 51.8 | 49.4 | 50.3 | Z=0.520 (p=.60) |

|

| ||||

| Percent Court Mandated | 20.7 | 22.2 | 21.4 | Z =0.396 (p=.69) |

|

| ||||

| Percent DSM-IV Dependence | ||||

| Cocaine | 70.9 | 72.7 | 71.8 | Z=0.433 (p=.66) |

| Methamphetamine | 38.4 | 33.8 | 36.1 | Z=1.038 (p=.30) |

| Amphetamine | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | Z=0.000 (p=1.00) |

| Alcohol | 45.6 | 44.9 | 45.2 | Z=0.152 (p=.88) |

|

| ||||

| Percent lifetime/Percent past 30- day use Cocaine | 76.4/44.7 | 82.1/44.4 | 79.2/44.6 | Z=1.526 (p=.13)/Z=0.065 (p=.95) |

| Methamphetamine | 44.7/19.4 | 39.7/20.5 | 42.3/20.0 | Z=1.098 (p=.27)/Z=0.298 (p=.77) |

| Amphetamine | 13.5/3.0 | 12.8/0.9 | 13.2/1.9 | Z=0.224 (p=.82)/Z=1.652 (p=.10 ) |

|

| ||||

| Percent self-reported 30-day pre-baseline stimulant abstinence | 38.0 | 39.7 | 38.9 | Z=0.378 (p=.71) |

|

| ||||

| Percent stimulant-negative urines | 77.7 | 78.6 | 78.1 | Z=0.236 (p=.81) |

|

| ||||

| Mean ASI composite scores (SD) | ||||

| Drugs | .157 (.09) | .155 (.09) | .156 (.09) | t(463)=0.18 (p=.86) |

| Alcohol | .162 (.21) | .159 (.20) | .161 (.21) | t(427)=0.11 (p=.91) |

| Psychiatric | .353 (.24) | .369 (.24) | .361 (.24) | t(452)= −0.73 (p=.78) |

|

| ||||

| Percent feeling considerably/extremely troubled by use | 51.7 | 54.5 | 53.1 | Z=0.608 (p=.5433) |

|

| ||||

| Percent feeling considerable/extreme need for treatment | 76.5 | 73.6 | 75.1 | Z=0.726 (p=.47) |

Table 2.

Participant 12-Step Experiences, Expectations, and Readiness

| 12-Step Variables | TAU (N = 237) | STAGE-12 (N = 234) | Total (N = 471) | Statistical Test of Difference in TAU & Stage-12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Twelve-Step Experiences and Expectancies (TSEE) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Percent ever previously involved in AOD mutual support groups | 59.4% | 62.9% | 61.1% | Z=0.778 (p=.44) |

|

| ||||

| Alcoholic Anonymous | ||||

| % previously attended1 | 86.3% | 89.3% | 87.8% | Z=0.994 (p=.32) |

| Median number of meetings attended2 | 45 | 50 | 50 | Z=−0.458 (p=.65) |

|

| ||||

| Narcotics Anonymous | ||||

| % previously attended1 | 89.9% | 86.0% | 87.9% | Z=1.299 (p=.19) |

| Median number of meetings attended2 | 45 | 30 | 39 | Z=1.136 (p=.26) |

|

| ||||

| Cocaine Anonymous | ||||

| % previously attended1 | 29.4% | 31.3% | 30.4% | Z=0.448 (p=.65) |

| Median number of meetings attended2 | 12 | 10 | 10 | Z=0.755 (p=.45) |

|

| ||||

| Mean helpfulness of previous mutual support group experiences (1 = Made things worse, 6 = Extremely helpful) (SD) | 4.8 (1.0) | 4.7 (1.1) | 4.7 (1.0) | t(280)=0.48 (p=.63) |

|

| ||||

| Mean rating of overall prior mutual support group experience (1 = Extremely negative, 4 = Extremely positive) (SD) | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.2 (0.7) | t(277)=0.03 (p=.98) |

|

| ||||

| Mean likelihood of getting involved in mutual support group meetings during this treatment (1 = Not at all likely, 4 = Extremely likely) (SD) | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.8) | t(461)= −1.21 (p=.23) |

|

| ||||

| Mean expected helpfulness of mutual support group as part of your current treatment and recovery process (1 = Not at all helpful, 4 = Extremely helpful) (SD) | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.4 (0.8) | t(459)= −0.28 (p=.78) |

|

| ||||

| Survey of Readiness for 12-Step Participation (SYRAAP) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Mean Perceived Benefit (SD) | 9.3 (4.0) | 9.6 (3.9) | 9.5 (4.0) | t(425)= −0.66 (p=.51) |

|

| ||||

| Mean Perceived Severity (SD) | 21.6 (4.1) | 21.8 (3.7) | 21.7 (3.9) | t(434)= −0.84 (p=.40) |

|

| ||||

| Mean Perceived Barriers (SD) | 22.4 (3.7) | 22.7 (3.3) | 22. 6 (3.5) | t(459)= −0.64 (p=.52) |

Percent of those individuals who indicated prior self-help group attendance who report having attended this particular 12-step program meeting

Median number of meetings attended by those who report having attended 1 or more meetings of this 12-step program

There were high endorsement rates for lifetime use of stimulant drugs. Over 70% of the sample met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for recent (past 6 months) cocaine dependence, 36.1% for methamphetamine dependence, and 6.8% amphetamine dependence, although relatively few participants (21.9%) had stimulant-positive urines at baseline. Approximately 45% of the total sample also met criteria for alcohol dependence. The ASI Drug Use Composite score for the total sample was 0.156 (SD=.09). Over 50% of the sample felt considerably or extremely troubled by their current drug use and 75% indicated a considerable or extreme need for treatment.

Over 60% of the sample had prior involvement in some form of 12-step substance-related mutual support group (AA: N = 251; NA: N = 250; and CA: N = 90). Participants in the two conditions were comparable in their positive appraisal of their prior 12-step experiences, the likelihood of engaging in 12-step meetings and activities in this treatment episode, the anticipated benefit from doing so, and in their readiness to participate in 12-step programs.

The two groups did not differ on any of the baseline variables found in Tables 1 and 2.

Follow-up Rates and Treatment Exposure

The number of participants in each condition that attended research visits decreased across time, as shown in Table 3. The overall follow-up rate was 70% and primary outcome data were available for 82% of the overall sample.

Table 3.

Number and percent of participants that attended each research visit by treatment condition

| Assessment Time Points | TAU [N (%)] | STAGE-12 [N (%)] | Total Sample [N (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 237 (100) | 233 (99.6) | 470 (99.8) |

| Week 4 | 200 (84.4) | 190 (81.2) | 390 (82.8) |

| Week 8 | 186 (78.5) | 168 (71.8) | 354 (75.2) |

| Month 3 | 175 (73.8) | 153 (65.4) | 328 (69.6) |

| Month 6 | 172 (72.6) | 158 (67.5) | 330 (70.1) |

Intensive outpatient treatment completion rates were not tracked. However, indicators of the services received during the 8-week period during which the STAGE-12 intervention was delivered were assessed using the Treatment Services Review (McLellan, et al., 1992), which was administered at week 4 (mid-treatment) and week 8 (end-of-treatment). Participants were asked how many times in the previous 30 days they had attended drug-focused educational sessions, relapse prevention meetings, individual counseling sessions, and group counseling sessions either in or outside of the CTP program. First, based on chi-square analyses, there were no differences between groups with respect to whether or not they had been receiving treatment services in their CTP during either of the 30 day windows of the two assessment points. There were no between-group differences at either assessment with respect to the number of educational sessions, relapse prevention meetings, or group counseling sessions attended in or outside of the CTP. However, STAGE-12 participants reported having attended more in-program individual sessions than TAU participants at the week-4 assessment (Mean = 1.49, SD = 1.21 versus Mean = 1.20, SD = 2.24) and at the 8-week assessment (Mean = 1.38, SD = 1.44 versus Mean = 0.98, SD = 1.77).

Overall, 66% of all scheduled STAGE-12 individual and group sessions were completed. Of the participants randomized to the STAGE-12 condition, 77% met the a priori criteria of having received a therapeutic dose of STAGE-12, having attended 2 or more individual sessions plus 3 or more group sessions.

Substance Use Outcomes

Self-reported stimulant use

Table 4 compares STAGE-12 and TAU groups on self-reported stimulant substance use across time and presents odds ratios for abstinence and the rate ratios and 95% CIs for days of non-abstinent stimulant use at each of the assessment points. The results indicate that for the 30-day windows from baseline to mid-treatment and between mid-treatment and end-of-treatment, the odds of abstinence from stimulant use were 3.34 and 2.44 times greater, respectively, for participants in STAGE-12 versus those in TAU, both of which are statistically significant. The model-based average predicted probabilities of abstinence from stimulant drugs for STAGE-12 and TAU, respectively, at these two time points were .71 versus .57 and .72 versus .61. The odds remain greater than one at the 90-day (OR = 1.78) and 120-day post-randomization follow-ups (OR = 1.30); while continuing to favor the STAGE-12 group, these odds ratios are not significant at p < .05.

Table 4.

Interaction odds ratios (abstinence) and incidence rate ratios (days of use) with primary outcome of stimulant substance use within a 30-day window of assessment.

| Logistic Portion of Model (Abstinence vs. Non- Abstinence) | Model-based average predicted probabilities of abstinence for stimulant substance use within each 30-day window | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment Time Points | Odds Ratio | 95% CI for Odds Ratio | TAU | STAGE-12 | Total |

| Mid-Treatment (30-day) | 3.34** | 1.20, 9.28 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.64 |

| End-of-Treatment (60-day) | 2.44* | 1.01, 5.86 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.66 |

| 1st Follow-up (90-day) | 1.78 | 0.81, 3.90 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.69 |

| 2nd Follow-up (120-day) | 1.30 | 0.60, 2.79 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.71 |

| 3rd Follow-up (150-day) | 0.95 | 0.42, 2.15 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.73 |

| Last Follow-up (180-day) | 0.69 | 0.27, 1.77 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.75 |

| Negative Binomial Portion of Model (Count of Non-zero Use) | Model-based average predicted values of number of days of stimulant substance use within each 30-day window | ||||

| Assessment Time Points | Rate Ratio | 95% CI for Rate Ratio | TAU | STAGE-12 | Total |

| Mid-Treatment (30-day) | 1.66* | 1.05, 2.60 | 1.08 | 1.19 | 1.13 |

| End-of-Treatment (60-day) | 1.50* | 1.01, 2.24 | 1.28 | 1.34 | 1.31 |

| 1st Follow-up (90-day) | 1.36 | 0.93, 1.98 | 1.51 | 1.50 | 1.51 |

| 2nd Follow-up (120-day) | 1.23 | 0.84, 1.79 | 1.77 | 1.69 | 1.73 |

| 3rd Follow-up (150-day) | 1.11 | 0.74, 1.66 | 2.05 | 1. 90 | 1.98 |

| Last Follow-up (180-day) | 1.00 | 0.64, 1.57 | 2.35 | 2.13 | 2.25 |

p<.05;

p<.025

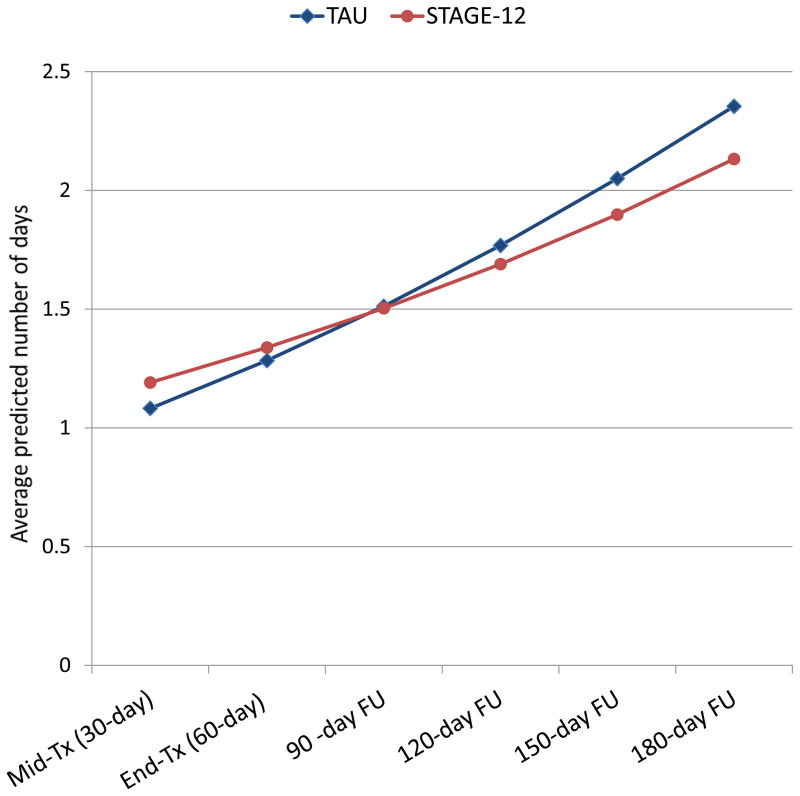

However, Table 4 also shows that for participants not stimulant-abstinent, the rate of stimulant use in STAGE-12 was 1.66 times greater than in TAU, from baseline to mid-treatment; the corresponding rate ratio was of 1.50 in the 30 days between mid-treatment to end-of-treatment. Subsequent rate ratios are not statistically significant. Although significant, the absolute differences between conditions in the model-based average predicted number of days of stimulant use both at mid-treatment (STAGE-12 = 1.19 days, TAU = 1.08 days) and end-of-treatment (STAGE-12 = 1.34 days, TAU = 1.28 days) are quite small. Furthermore, as seen in Figure 1, the direction of the difference in rates of use changes during the post-treatment follow-up points, with STAGE-12 having lower rates of use than TAU; however, these latter differences at the subsequent time points are not significant.

Figure 1.

Model-based average predicted values of number of days of stimulant substance use within each 30-day window

Urinalysis results

The urine screen data for stimulant drugs were binary in nature (positive or negative); thus a logistic random-effects regression model was used to compare groups. No interaction odds ratios were noted, but the statistically significant time main effect revealed an OR = 1.28 (95% CI = 1.13, 1.45), which indicates that with each unit increase in time (30 days), the odds of having a stimulant-positive urine screen increased by a factor of 1.28, irrespective of treatment condition.

ASI Dug Use Composite score

Given the skewed distributional properties of the ASI Drug Use Composite score, it was evaluated as both a dichotomous (0, >0) and a continuous variable for those having scores greater than zero at baseline, 3-month, and 6-month follow-up points. There were no differences between STAGE-12 and TAU conditions in the percent of participants with zero scores on the dichotomized ASI Drug Use Composite scores at any of the time points. There was a significant difference between groups (t(206) = 2.02, p = .044) at the 3-month follow-up, with STAGE-12 having a significantly lower Drug Use Composite score than the TAU group. The STAGE-12 group also demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in the ASI Drug Use Composite score from baseline to the 3-month follow-up than did the TAU group (t(324) = −2.12, p = .035).

12-Step Outcomes

Mutual support meeting attendance

A zero-inflated negative binomial random-effects regression model analysis was conducted to compare treatment groups on the number of days of meeting attendance within a 30-day window of assessment as measured by the SUC. No differences were found between STAGE-12 and TAU groups in the probability of attending (ORs) or number of days of attending meetings (RRs). With each passing 30-day time period from baseline, the odds of NOT attending increase by a factor of 1.87, regardless of treatment group (OR = 1.87 [95% CI = 1.60, 2.19]). Similarly, with each passing 30-day time period the number of days of attendance decrease by a factor of .93, irrespective of the treatment group (RR = 0.93 [95% CI = 0.91, 0.95]).

Results of a negative binomial random-effects regression model based on the SHAQ show that STAGE-12 participants report a significantly greater number of days of AA, NA, CA or CMA meeting attendance within 30-day assessment windows than TAU clients, as indicated by significant interaction rate ratios at baseline and mid-treatment, RR = 1.21 and RR = 1.18, respectively. The model based number of days of attendance by STAGE-12 and TAU groups, respectively, were 15.13 vs. 13.15 days and 14.45 versus 12.87 days at these two time points. The RR = 1.15 between mid- and end-of treatment is borderline, within rounding error of a 95% CI = (1.00, 1.33), indicating that STAGE-12 participants had a higher rate of attendance than those in TAU.

12-Step mutual support activities

The study operationalized 12-step/mutual support involvement within each 30-day time period using three variables derived from the SHAQ: (1) the sum of occurrence of 6 activities critical to 12-step involvement; (2) the maximum number of days of self-reported speaking at AA, NA, CA or CMA meetings; and (3) the maximum number of days of self-reported meeting service activities (e.g., helping set up or clean up, making coffee). A Poisson random-effects regression model was used to analyze the first of these variables, and negative binomial random-effects regression models were used to analyze the latter two. Table 5 provides the rate ratios and model-based values associated with each of these analyses.

Table 5.

Interaction rate ratios and model-based predicted average values for indicators of 12-step engagement and participation from the SHAQ

| Interaction rate ratios and model-based average predicted number of other activities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time point | Rate Ratio (95% CI) | Average number of activities | ||

| TAU | Stage-12 | Total | ||

| Baseline | 1.294* (1.114, 1.503) | 2.46 | 2.94 | 2.70 |

| Mid-treatment (30-day) | 1.311* (1.139, 1.512) | 2.48 | 3.01 | 2.74 |

| End-of-treatment (60-day) | 1.331** (1.15, 1.52) | 2.50 | 3.08 | 2.79 |

| 1st Follow-up (90-day) | 1.349** (1.173, 1.553) | 2.52 | 3.15 | 2.84 |

| Last Follow-up (180-day) | 1.408** (1.223, 1.620) | 2.59 | 3.38 | 2.98 |

| * p < .001, ** p < .0001 | N = 232 | N = 231 | N = 463 | |

| Interaction rate ratios and model-based average predicted number of self-reported days of speaking at AA, NA, CA, or CMA Meetings | ||||

| Time point | Rate Ratio (95% CI) | Average number of days | ||

| TAU | Stage-12 | Total | ||

| Baseline | 1.308 (0.935, 1.831) | 3.13 | 3.56 | 3.35 |

| Mid-treatment (30-day) | 1.323 (0.970, 1.806) | 3.14 | 3.60 | 3.37 |

| End-of-treatment (60-day) | 1.339 (0.989, 1.813) | 3.14 | 3.65 | 3.39 |

| 1st Follow-up (90-day) | 1.354 (0.989, 1.854) | 3.14 | 3.69 | 3.42 |

| Last Follow-up (180-day) | 1.401 (0.9996, 1.919) | 3.15 | 3.83 | 3.49 |

| N = 211 | N = 213 | N = 424 | ||

| Interaction rate ratios and model-based average predicted number of self-reported days of service activities at AA, NA, CA, or CMA Meetings | ||||

| Time point | Rate Ratio (95% CI) | Average number of days | ||

| TAU | Stage-12 | Total | ||

| Baseline | 1.320 (0.817, 2.132) | 1.45 | 1.46 | 1.45 |

| Mid-treatment (30-day) | 1.456 (0.933, 2.273) | 1.54 | 1.71 | 1.63 |

| End-of-treatment (60-day) | 1.607* (1.043, 2.476) | 1.64 | 2.01 | 1.83 |

| 1st Follow-up (90-day) | 1.773** (1.137, 2.764) | 1.75 | 2.37 | 2.0 |

| Last Follow-up (180-day) | 2.380*** (1.527, 3.711) | 2.12 | 3.85 | 2.98 |

| *p<.05, **, p<.05, ***p<.001 | N = 211 | N = 213 | N = 424 | |

The Poisson random-effects regression model analysis indicates significant interaction rate ratios at baseline through last follow-up for the number of mutual support activities, with STAGE-12 participants engaging in significantly more activities. Although the rate ratio at baseline is significant with this longitudinal model, a univariate Poisson model comparing the baseline measure alone between the TAU and STAGE-12 treatment groups was not significant (RR = 1.08, 95% CI = 0.96, 1.23), or alternatively, the Wald χ2 = 1.69, p = .194. Observed baseline values are 2.25 (N = 222) for TAU and 2.44 (N = 217) for STAGE-12. Therefore, the significance at baseline may be more model-driven with a linear trend of increasing rates from baseline to last follow-up. The model-based average predicted number of other activities, which could range from 0 to 6, increased from 3.01 at mid-treatment to 3.38 at the 6-month post-randomization follow-up for STAGE-12; the number of activities increased from 2.48 to 2.59 over this same time period.

The negative binomial random-effects regression analyses indicate no significant interaction rate ratios from baseline through last follow-up with respect to speaking at mutual support meetings; the main effects of Time and Treatment were also not significant. However, significant interaction rate ratios were observed at end-of-treatment and the first (90-day) and last (180-day) follow-up periods for self-reported days of carrying out service activities at meetings. These rate ratios tend to increase over time, favoring the STAGE-12 group. The rate of the number of service activities for subjects in STAGE-12 is 1.61 times that of those in TAU between mid- and end-of-treatment, and increases to a rate of 2.38 for the 30 days preceding the last follow-up assessment. The model-based average predicted number of self-reported days of service at meetings increased from 2.01 at end-of-treatment to 3.85 at the 6-month post-randomization follow-up for the STAGE-12 group; days of service increased from 1.64 to 2.12 for the TAU group over the same time period.

DISCUSSION

The results of the current trial present mixed findings with respect to the impact of integrating the STAGE-12 intervention into an intensive outpatient drug treatment program on the stimulant use of individuals with stimulant use disorders. STAGE-12 involvement was associated with significantly increased odds of abstinence from stimulant drug use over the duration of the active treatment phase. The odds of abstinence for STAGE-12 participants relative to TAU ranged from 3.34 times greater from baseline to mid-treatment and 2.44 between mid-treatment and end-of-treatment. Although the odds ratios still favored STAGE-12 out to the 6 -month post-randomization follow-up, they were no longer significant. However, an unexpected finding showed that if a participant was not abstinent, then the rate of stimulant use was significantly greater for those in STAGE-12 than in TAU during the active treatment phase; this relationship reversed during the follow-up periods.

The pattern of these findings suggests a complex dynamic: the STAGE-12 intervention, as incorporated into existing intensive outpatient treatment, facilitates the initiation and probability of stimulant abstinence, but is not particularly effective for those who are unable to achieve or maintain abstinence. A possible explanatory hypothesis for this pattern can be drawn from the Abstinence Violation Effect (AVE) proposed by Marlatt and colleagues (Marlatt, 1985; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985) as part of their cognitive-behavioral relapse model . The AVE suggests that if an individual is strongly committed to abstinence as a goal but is unable to achieve or maintain abstinence, the likelihood of continued use is increased. It may be that STAGE-12’s systematic and intensive focus on 12-step principles increased the salience of abstinence as a goal; as a result those who were unable to achieve this goal were more vulnerable to continued heavy use. The original construct of the AVE was posited to be mediated by a sense of self-blame and internal attributions to oneself as a failure in one’s inability to maintain abstinence (e.g., “Once an addict, always an addict”), with resultant guilt, and a decrease in perceived self-efficacy. However, results of later studies with substance abusers suggested that the heavy use associated with the AVE may be related more to low levels of self-efficacy than to either attributions of self-blame or guilt (Birke, Edelmann, & Davis, 1990; Kirchner, Shiffman, & Wileyto, 2011; Ross, Miller, Emmerson, & Todt, 1988 -1989; Walton, Castro, & Barrington, 1994). The STAGE-12 intervention may need to be modified to specifically address such emotional reactions of patients when they feel they are not achieving their abstinence goals. For example, this issue could be addressed specifically in one of the individual sessions, discussed as a possible phenomenon during the group session on managing negative emotions and the HALT relapse precipitants, or emphasized as something to write about while journaling with follow-up discussion in sessions.

Alternatively, as has been found with other behavioral treatments with substance abusers, there may be subgroups for whom the STAGE-12 intervention is clinically effective while others for whom there is no effect or even clinical deterioration (Ilgen & Moos, 2005). Two factors of particular relevance in this regard are treatment exposure and the initial, early achievement of abstinence. Kaskutas (Kaskutas, et al., 2009) found a significant linear trend between the number of sessions of a group-based 12-step facilitation intervention attended and the percent of participants substance free at 12-month follow-up. Three-quarters of STAGE-12 participants reached an a priori criterion of a therapeutic dose of the intervention by having attended two or more individual sessions plus three or more of the group sessions. It may be that the smaller subgroup of STAGE-12 “non-completers” accounts for the observed increased rates of stimulant use. Similarly, in addition to the predictive utility of entering treatment stimulant-free (Ahmadi et al., 2009; Peirce et al., 2009), the early attainment of abstinence among cocaine dependent individuals in clinical trials is one of the best predictors of later abstinence (McKay, et al., 2001; Plebani, Kampman, & Lynch, 2009). As McKay and colleagues note, continued participation in mutual support groups and the early achievement of cocaine abstinence appear to be important factors in longer term outcomes.

Despite the higher self-reported rates of stimulant use among the non-abstinent STAGE-12 group members during the active treatment phase, there was a significant difference favoring STAGE-12 with respect to the ASI Drug Use Composite score at the 3-month follow-up period. Similarly, STAGE-12 participants significantly reduced their scores on this measure from baseline to the 3-month follow-up while TAU participants did not. The Composite score is based on drug use across a number of different substances, perceived drug-related problems, and perceived need for drug treatment during the 30-days preceding the interview. The results suggest that at the 3-month follow-up the STAGE-12 participants, as a group, reported less drug use and perceived themselves as having fewer substance-related problems and less need for treatment than those who had been in TAU. This finding is consistent with the fact that the odds of abstinence at that point, although not significant, still favored STAGE-12 and the rate of use among non-abstinent individuals was comparable between conditions and thereafter began favoring STAGE-12.

A secondary study focus was to determine the impact of STAGE-12 on increasing 12-step meeting attendance and engagement in 12-step activities. Two different measures were used to assess this variable. The Substance Use Calendar results demonstrated no differences between the conditions with respect to either the odds of attending meetings or the number of days on which meetings were attended. However, the Self-Help Activities Questionnaire (SHAQ) data demonstrated that the STAGE-12 group had a significantly higher rate of meeting attendance from baseline to the mid-treatment point and a nearly significant rate from the mid-point to the end of treatment than did the TAU group. The reason for the divergence in these two measures is not clear, although their respective methodologies are somewhat different. Specifically, the SUC asks about meeting attendance on a day-to-day basis on a calendar and has demonstrated intervention effects for a facilitative intervention to increase AA attendance by alcohol dependent individuals. The SHAQ (Weiss, et al., 1996) asks individuals to estimate the number of days in a 30 day window in which they attended AA, CA, NA, and other 12-step and non-12-step (e.g., Secular Organization for Sobriety, Rational Recovery) self-help meetings as well as the number of days of engaging in 12-step recovery activities and service . Previous versions of the SHAQ have been found to have a high degree of internal consistency and predictive validity, have been used to describe mutual support related behaviors, to evaluate differential changes in these behaviors as a function of the type of treatment received, and to compare the relationship between 12-step attendance and participation with subsequent drug use outcomes (Weiss, Griffin, Gallop, Luborsky, et al., 2000; Weiss, Griffin, Gallop, Onken, et al., 2000; Weiss, et al., 2005; Weiss, et al., 1996). Measures similar to the SHAQ, in which participants are asked to estimate the number or frequency of 12-step meetings attended and the frequency of other 12-step activities and indicators of affiliation, have been used extensively in prior 12-step research and have demonstrated predictive utility (Humphreys, Kaskutas, & Weisner, 1998; McKellar, et al., 2003; Morgenstern, et al., 1996; Tonigan, Connors, & Miller, 1996). It is of note that the difference between groups on the SHAQ was found over the first four weeks of the intervention period, the time during which the intensive referral process might have been most likely to have led to the arranged 12-step meeting attendance with the community volunteer in the STAGE-12 condition.

The SHAQ results more clearly indicate that individuals in STAGE-12 had higher rates of 12-step related activities throughout both the active treatment phase and the entire 6-month follow-up period than did those in TAU. Furthermore, the rate ratios of the number of days of service at meetings (e.g., setting up, making coffee, cleaning up) for subjects in STAGE-12 was significantly greater, increasing from 1.61 times that for those in TAU between mid- and end-of-treatment and increasing to a rate of 2.38 for the 30 days preceding the 6-month follow-up assessment. This is of particular note since a number of studies have shown that involvement in 12-step activities and service often increase over time (whereas meeting attendance may decline) and is a more important indicator of engagement, a better predictor of subsequent outcome, and the potential mediator of change associated with 12-step mutual support groups (Kaskutas, 2009; Owen, et al., 2003; Subbaraman, et al., 2011; Weiss, et al., 2005). Consistent with this, data derived from the SHAQ in the NCCTS demonstrated that 12-step meeting attendance did not predict drug use or ASI Drug Use Composite scores among cocaine dependent individuals while indicators of 12-step service and activities predicted both (Weiss, et al., 2005).

The present study has a number of limitations. First, although TAU counselors were instructed not to utilize components or distribute materials from the STAGE-12 intervention, no specific assessments were conducted to determine if and to what extent there might have been contamination or “bleed” from the STAGE-12 condition to TAU. Second, while information about group and individual counseling sessions was available from the Treatment Services Review for both conditions during the 8-week period over which the STAGE-12 intervention was delivered, data concerning drop-out/completion rates for the overall CTP intensive outpatient program that participants were attending is lacking. Third, there was considerable variability across CTPs in both the length/duration and the number of hours per week of the IOP into which STAGE-12 was integrated; the relative impact of STAGE-12 may vary depending on these characteristics of the clinical program.

In summary, STAGE-12, compared to TAU, contributed to a greater likelihood of abstinence from stimulant drugs over the active treatment phase, although it was associated with more days of use among those not achieving abstinence during this period. Relative to TAU, STAGE-12 was also associated with a significant reduction in, and a lower level of, substance use problems as measured by the ASI Drug Use Composite score at the 3-month follow-up. STAGE-12 participants also engaged in significantly more 12-Step activities and meeting-related service than did those in TAU. Subsequent analyses are planned to explore treatment exposure and early achievement of abstinence as well as other variables that might predict and differentiate subgroups having differential outcomes in STAGE-12. Subsequent analyses also will examine the relative predictive value of measures of 12-step attendance versus participation with respect to both substance use and psychosocial outcomes among stimulant abusers.

Acknowledgments

This report was supported by a series of grants from NIDA as part of the Cooperative Agreement on National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network (CTN): Appalachian/Tri-States Node (U10DA20036), Florida Node Alliance (U10DA13720), Ohio Valley Node (U10DA13732), Oregon Node (U10DA13036), Pacific Region Node (U10DA13045), Pacific Northwest Node (U10DA13714), Southern Consortium Node (U10DA13727), and Texas Node (U10DA20024). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA.

We would like to express our appreciation to the patients and the administrative, clinical, and research staff of the 10 community-based treatment programs that participated in the present study: Center for Psychiatric & Chemical Dependency Services, Pittsburgh, PA; ChangePoint, Inc. Portland, OR; Dorchester Alcohol & Drug Commission, Summerville, SC; Evergreen Manor, Everett, WA; Gateway Community Services, Jacksonville, FL; Hina Mauka, Kaneohe, HI; Maryhaven, Columbus, OH; Nexus Recovery Center, Dallas, TX; Recovery Centers of King County, Seattle, WA; Willamette Family Treatment Services, Eugene, OR.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmadi J, Kampman KM, Oslin DM, Pettinati HM, Dackis C, Sparkman T. Predictors of treatment outcome in outpatient cocaine and alcohol dependence treatment. American Journal of Addiction. 2009;18(1):81–86. doi: 10.1080/10550490802545174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcoholics Anonymous. Bridging the gap between treatment and AA through temporary contact programs. New York, NY: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baker S. Twelve Step Facilitation for Drug Dependence. New Haven, CT: Psychotherapy Development Center, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Baker S, Daley DC, Donovan DM, Floyd AS. STAGE-12: Stimulant Abuser Groups to Engage in 12-Step Programs: A combined group and individual treatment program. Unpublished therapy manual. Center for the Clinical Trials Network, National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Birke SA, Edelmann RJ, Davis PE. An analysis of the abstinence violation effect in a sample of illicit drug users. British Journal on Addictions. 1990;85(10):1299–1397. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TG, Seraganian P, Tremblay J, Annis H. Matching substance abuse aftercare treatments to client characteristics. Addict ive Behaviors. 2002a;27(4):585–604. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TG, Seraganian P, Tremblay J, Annis H. Process and outcome changes with relapse prevention versus 12-Step aftercare programs for substance abusers. Addiction. 2002b;97:677–689. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell PE. Fostering client connections with Alcoholics Anonymous: a framework for social workers in various practice settings. Social Work in Health Care. 1999;28(4):45–61. doi: 10.1300/J010v28n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell PE, Cutter HS. Alcoholics Anonymous affiliation during early recovery. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1998;15(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, McCance E, Frankforter TL, Rounsaville BJ. One-year follow-up of disulfiram and psychotherapy for cocaine-alcohol users: Sustained effects of treatment. Addiction. 2000;95(9):1335–1349. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95913355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Ball SA, McCance E, Rounsavile BJ. Treatment of cocaine and alcohol dependence with psychotherapy and disulfiram. Addiction. 1998;93(5):713–727. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9357137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Intensive outpatient treatment for alcohol and other drug abuse (Vol. Tip No. 8) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR Project MATCH Research Group. A longitudinal model of intake symptomatology, AA participation and outcome: retrospective study of the Project MATCH outpatient and aftercare samples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(6):817–825. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Blaine J, Frank A, Luborsky L, Onken LS, Beck AT. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56(6):493–502. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley DC, Baker S, Donovan DM, Hodgkins CC, Perl H. A combined group and individual 12-Step facilitative intervention targeting stimulant abuse in the NIDA Clinical Trials Network: STAGE-12. Journal of Groups in Addiction and Recovery. 2011;6(3):228–244. doi: 10.1080/1556035X.2011.597196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley DC, Mercer DE, Carpenter G. Drug counseling for cocaine addiction: The Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study model. Vol. 4. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM. Efficacy and effectiveness: Complementary findings from two multisite trials evaluating outcomes of alcohol treatments differing in theoretical orientations. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23(3):564–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Daley DC, Brigham GS, Hodgkins CC, Perl HI, Floyd AS. How practice and science are balanced and blended in the NIDA Clinical Trials Network: The bidirectional process in the development of the STAGE-12 protocol as an example. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37(5):408–416. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.596970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Floyd AS. Facilitating involvement in twelve-step programs. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. 2008;18:303–320. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-77725-2_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Wells EA. “Tweaking 12-Step”: The potential role of 12-step self-help group involvement in methamphetamine recovery. Addiction. 2007;102(Supplement 1):121–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O’Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(1):134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentine R. After drug treatment: Are 12-step programs effective in maintaining abstinence? American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25(1):93–116. doi: 10.1081/ada-100101848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentine R, Hillhouse MP. Drug treatment and 12-step program participation: The additive effects of integrated recovery activities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2000a;18(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(99)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentine R, Hillhouse MP. Exploring the additive effects of drug misuse treatment and Twelve-Step involvement: does Twelve-Step ideology matter? Substance Use and Misuse. 2000b;35(3):367–397. doi: 10.3109/10826080009147702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert FS. Development of a “Steps Questionnaire”. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52(4):353–360. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godlaski TM, Leukefeld C, Cloud R. Recovery: with and without self-help. Substance Use and Misuse. 1997;32(5):621–627. doi: 10.3109/10826089709027316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossop M, Stewart D, Marsden J. Attendance at Narcotics Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, frequency of attendance and substance use outcomes after residential treatment for drug dependence: A 5-year follow-up study. Addiction. 2008;103(1):119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Best D, Gossop M, Marshall J, Man LH, Manning V, Strang J. Prior Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) affiliation and the acceptability of the Twelve Steps to patients entering UK statutory addiction treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(2):257–261. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM. Brief overview on interpreting count model risk ratios: An addendum to Negative Binomial Regression. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hudziak JJ, Helzer JE, Wetzel WW, Kessel KB, McGee B, Janca A, Przybeck T. The use of the DSM-III-R Checklist for initial diagnostic assessment. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1993;34(6):375–383. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(93)90061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K. Professional interventions that facilitate 12-step self-help group involvement. Alcohol Research and Health. 1999;23(2):93–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K. Alcoholics Anonymous and 12-step alcoholism treatment programs. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. 2003;16:149–164. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47939-7_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Huebsch PD, Finney JW, Moos RH. A comparative evaluation of substance abuse treatment: V. Substance abuse treatment can enhance the effectiveness of self-help groups. Alcohol: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23(3):558–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Kaskutas LA, Weisner C. The Alcoholics Anonymous Affiliation Scale: development, reliability, and norms for diverse treated and untreated populations. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22(5):974–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Moos RH. Encouraging posttreatment self-help group involvement to reduce demand for continuing care services: Two-year clinical and utilization outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2007;31(1):64–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K, Wing S, McCarty D, Chappel J, Gallant L, Haberle B, Weiss R. Self-help organizations for alcohol and drug problems: toward evidence-based practice and policy. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;26(3):151–158. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen M, Moos R. Deterioration following alcohol-use disorder treatment in project MATCH. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(4):517–525. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA. Alcoholics anonymous effectiveness: Faith meets science. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2009;28(2):145–157. doi: 10.1080/10550880902772464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Ammon L, Delucchi K, Room R, Bond J, Weisner C. Alcoholics anonymous careers: Patterns of AA involvement five years after treatment entry. Alchoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(11):1983–1990. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000187156.88588.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Subbaraman MS, Witbrodt J, Zemore SE. Effectiveness of Making Alcoholics Anonymous Easier: a group format 12-step facilitation approach. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37(3):228–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Moos R. Dropout from 12-step self-help groups: prevalence, predictors, and counteracting treatment influences. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24(3):241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingree JB, Simpson A, Thompson M, McCrady B, Tonigan JS. The predictive validity of the survey of readiness for alcoholics anonymous participation. 2007;68(1):141–148. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingree JB, Simpson A, Thompson M, McCrady B, Tonigan JS, Lautenschlager G. The development and initial evaluation of the survey of readiness for alcoholics anonymous participation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20(4):453–462. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner TR, Shiffman S, Wileyto EP. Relapse dynamics during smoking cessation: Recurrent abstinence violation effects and lapse-relapse progression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0024451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet A, Stanick V, Sands B. An exploration of the effect of on-site 12-Step meetings on post-treatment outcomes among polysubstance-dependent outpatient clients. Evaluation Review. 2007;31(6):613–646. doi: 10.1177/0193841x07306745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majer JM, Jason LA, Ferrari JR, Miller SA. 12-Step involvement among a U.S. national sample of Oxford House residents. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2011;41(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention: Theoretical rational and overview of the model. In: Marlatt GA, Gordon JR, editors. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Gordon JR, editors. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Merikle E, Mulvaney FD, Weiss RV, Koppenhaver JM. Factors accounting for cocaine use two years following initiation of continuing care. Addiction. 2001;96(2):213–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9622134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKellar J, Stewart E, Humphreys K. Alcoholics anonymous involvement and positive alcohol-related outcomes: Consequence, or just a correlate? A prospective 2-year study of 2,319 alcohol-dependent men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(2):302–308. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Cacciola J, Metzger D, O’Brien CP. A new measure of substance abuse treatment: Initial studies of the Treatment Services Review. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1992;180(2):101–110. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer DE, Woody GE. An individual drug counseling approach to treat cocaine addiction: The Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study Model. (Manual 3) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery HA, Miller WR, Tonigan JS. Does Alcoholics Anonymous involvement predict treatment outcome? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1995;12:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)00018-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Long-term influence of duration and frequency of participation in alcoholics anonymous on individuals with alcohol use disorders. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(1):81–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Paths of entry into alcoholics anonymous: consequences for participation and remission. Alchoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(10):1858–1868. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183006.76551.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]