Abstract

BACKGROUND

The effect of body mass index (BMI) on treatment outcome of children with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is unclear and needs further evaluation.

METHODS

Children with AML (n=314) enrolled in 4 consecutive St. Jude protocols were grouped according to BMI (underweight, <5th percentile; healthy weight, 5th to 85th percentile; and overweight/obese, ≥ 85th percentile).

RESULTS

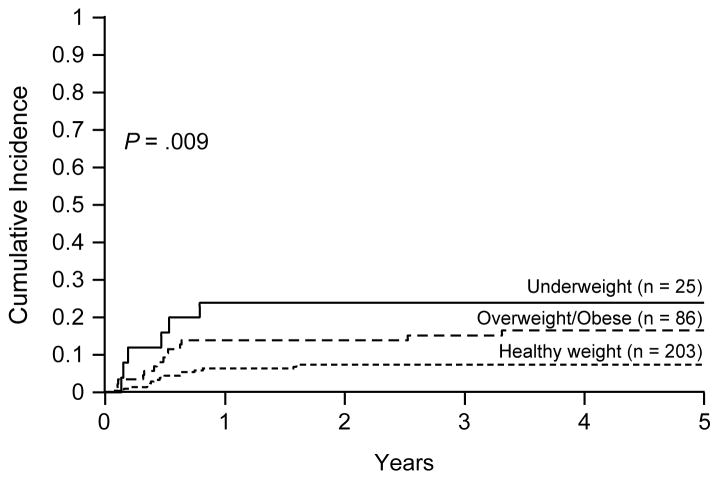

Twenty-five (8.0%) patients were underweight, 86 (27.4%) overweight/obese, and 203 (64.6%) had healthy weight. Five-year overall survival of overweight/obese patients (46.5±7.3%) was lower than that of patients with healthy weight (67.1±4.3%, P < .001); underweight patients also tended to have lower survival rates (50.6±10.7%, P = .18). In a multivariable analysis adjusting for age, leukocyte count, FAB type, and study protocols, patients with healthy weight had the best survival rate among the 3 groups (P = .01). When BMI was considered as continuous variable, patients with lower or higher BMI percentiles had worse survival (P = .03). There was no difference in the occurrence of induction failure or relapse among BMI groups but underweight and overweight/obese patients had a significantly higher cumulative incidence of treatment-related mortality, especially due to infection (P = .009).

CONCLUSIONS

An unhealthy BMI is associated with worse survival and more treatment-related mortality in children with AML. Meticulous supportive care, with nutritional support and education, infection prophylaxis, and detailed laboratory and physical examination is required for these patients. These measures, together with pharmacokinetics-guided chemotherapy dosing may improve outcome.

Keywords: body mass index, children, acute myeloid leukemia, survival, toxicity

INTRODUCTION

The use of comprehensive risk classification algorithms, improvements in supportive care, and careful application of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation have increased survival rates for children with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) to approximately 70% in recent clinical trials.1, 2 Current risk classification strategies are based primarily on the analysis of genetic abnormalities of leukemic blasts and the careful monitoring of each patient’s early response to induction therapy, both of which are used to adjust therapy.2, 3 However, certain clinical features, such as age and body mass index (BMI), which are not typically used for risk stratification, are also associated with outcome.2, 4 For example, age greater than 10 years was an independent adverse prognostic feature in our AML02 trial.2 In the Children’s Cancer Group (CCG) 2961 trial, underweight and overweight patients with AML were less likely to survive and more likely to experience treatment-related mortality than were middleweight patients,4 but these results await confirmation. Thus, we examined the effects of BMI on treatment outcome of children with AML in our patient cohort.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients with AML (n = 314) who were 2 to 20 years old and were enrolled in 4 consecutive St. Jude AML protocols (AML87,5 AML91,6 AML97,7 and AML022) were included in this analysis. Patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL, enrolled in only AML87), mixed phenotype acute leukemia (enrolled in only AML97 and 02) and secondary AML were excluded. The chemotherapy dose was not modified on the basis of BMI. The protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at participating hospitals, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their guardians or parents.

BMI Classification

The BMI at diagnosis for each of the 314 eligible patients was calculated by using the macro for SAS provided by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/resources/sas.htm). The patients were initially classified into 4 groups based on CDC weight status and BMI percentiles for children and teens (http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html#What): underweight, < 5th percentile; healthy weight, 5th to 85th percentile; overweight, 85th to 95th percentile; obese, ≥ 95th percentile.

Statistical Analyses

The association of BMI category with other categorical variables was explored by using a Monte-Carlo approximation to the exact Chi-square test; this approximation was based on 10,000 permutations. The association of BMI category with continuous variables was explored by using the Kruskal-Wallis test.8

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time elapsed from study enrollment to death, with those still living at the last follow-up considered censored. Event-free survival (EFS) was defined as the time elapsed from study enrollment to induction failure, withdrawal, relapse, secondary malignancy, or death, with those living and event-free at the last follow-up considered censored. The time to first occurrence of infection was defined as the time elapsed from study enrollment to the first occurrence of a grade 2 or higher infection during chemotherapy. Withdrawal, death, and relapse were treated as competing events. Those without events were sequentially censored at the end of the last course, when off therapy, or when off study.

The Kaplan-Meier method9 was used to estimate the probability of OS and EFS, and standard errors were determined by using the method of Peto and Pike.10 Survival comparisons were performed by using the Mantel-Haenszel log-rank test, with significance being determined by 10,000 permutations.11 The log-rank test was stratified by study protocol for 2-group comparisons. In multivariable analysis, OS and EFS were modeled by using the Cox proportional hazard model with age, leukocyte count, FAB type, and weight status as class predictor variables, stratified by study protocol.12 Gray’s method was used to estimate and compare the cumulative incidence of infection, induction failure and relapse, and death during complete remission.13 OS and EFS were also modeled in the Cox proportional hazard regression analysis by using BMI percentile as a continuous variable in a spline model, stratified by study protocol.14 In multivariable analysis, OS and EFS were modeled in the Cox proportional hazard regression analysis with age, leukocyte count and FAB type as class predictor variables and BMI percentile as a continuous variable in a spline model, stratified by study protocol. The degrees of freedom were automatically selected by Akaike Information Criteria.

All analyses were performed using SAS software Windows version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and StatXact Windows version 7.1 (Cytel Corporation, Cambridge, MA).

RESULTS

Patient demographics

Among the 314 patients, 25 (8.0%) were classified as underweight, 203 (64.6%) as healthy weight, 37 (11.8%) as overweight, and 49 (15.6%) as obese. Because there was no significant difference in all analyses between overweight and obese patients, they were grouped into one BMI category, i.e., overweight/obese (86 patients, 27.4%) (Table 1). The prevalence of the three BMI groups was significantly different among patients of different age. Underweight children were younger than healthy weight children, who in turn were younger than overweight/obese children (P < .001). We also noted that patients enrolled in the most recent protocol had a higher BMI (P = .001).

Table 1.

Demographics and Disease Characteristics of Patients in the 3 BMI Groups

| Clinical Features | Underweight (N=25) | Healthy Weight (N=203) | Overweight/Obese (N=86) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| Median (range) | 6.7 (2.1–18.6) | 9.6 (2.0–19.3) | 13.2 (2.0–19.9) | <.001 |

| 2–9.9 | 15 | 103 | 21 | <.001 |

| 10–20 | 10 | 100 | 65 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 12 | 107 | 45 | .92 |

| Female | 13 | 96 | 41 | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 16 | 148 | 56 | .66 |

| Black | 7 | 36 | 23 | |

| Hispanic | 1 | 5 | 2 | |

| Other | 1 | 13 | 5 | |

| Not available | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| White blood cell count (× 109/L) | ||||

| Median (range) | 12.2 (1.7–209) | 12.8 (0.01–412.2) | 23.7 (0.03–358.1) | .09* |

| <50 | 20 | 157 | 56 | .08 |

| ≥ 50 | 5 | 46 | 30 | |

| FAB | ||||

| M0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | .04 |

| M1 | 1 | 27 | 17 | |

| M2 | 8 | 64 | 20 | |

| M4 | 5 | 49 | 19 | |

| M5 | 3 | 30 | 19 | |

| M6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| M7 | 6 | 9 | 4 | |

| MDS | 1 | 7 | 0 | |

| Not available | 0 | 13 | 4 | |

| Cytogenetics | ||||

| Normal | 6 | 70 | 27 | .50 |

| t(8;21) | 4 | 44 | 15 | |

| inv(16) | 4 | 17 | 11 | |

| t(9;11) | 0 | 13 | 7 | |

| 11q23 | 2 | 13 | 10 | |

| Other | 9 | 44 | 15 | |

| Not available | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| Study Protocol | ||||

| AML875 | 7 | 22 | 6 | .001 |

| AML916 | 7 | 43 | 7 | |

| AML977 | 4 | 45 | 18 | |

| AML022 | 7 | 93 | 55 | |

| HSCT | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 83 | 27 | .28 |

| No | 17 | 120 | 59 | |

Abbreviations: FAB, French-American-British classification; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Kruskal-Wallis test. All other P values are from exact Chi-square test.

Associations between BMI and Survival

Five-year OS rates differed significantly when the three BMI groups were compared (P = .003, Fig. 1A). In comparisons between healthy weight and either unhealthy BMI categories, overweight/obese patients had a significantly lower 5-year OS rate than that of patients with healthy weight (46.5±7.3% versus 67.1±4.3%, P < .001); underweight patients also had a lower, but not significantly different statistically, survival rate (50.6±10.7%, P = .18). Five-year EFS rates were also significantly different among the 3 BMI categories (P = .04, Fig. 1B), with overweight/obese patients having a significantly lower 5-year EFS than those with healthy weight (39.4±7.2% versus 54.6±4.7%, P = .005), and underweight patients with a lower but not significantly inferior rate (40.0±10.3%, P = .21).

Figure 1.

Overall survival (A) and event-free survival (B) of 314 children with acute myeloid leukemia. Data were analyzed with patients classified into 3 groups of body mass index: underweight, healthy weight, overweight/obese.

In a multivariable analysis including BMI, age, leukocyte count, and AML FAB subtype, stratified by study protocols, BMI status remained significantly associated with OS (P = .01) but not with EFS (P = .14) (Table 2). In this analysis, overweight/obese patients had a significantly lower OS (P = .004) as compared to patients with healthy weight, and tended to have lower EFS (P = .08). The OS and EFS did not differ significantly between underweight and healthy weight patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable COX Regression Model of Survival Stratified by Study Protocol

| Event-Free survival | Overall Survival | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P value | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P value | |

| Weight Category | .14 | .01 | ||||

| Age (10–20 vs. 2–9.9) | 1.69 | 1.166–2.451 | .006 | 1.76 | 1.16–2.671 | .008 |

| FAB type | .005 | .004 | ||||

| WBC (≥50 vs. <50) | 1.394 | 0.951–2.045 | .09 | 1.253 | 0.815–1.926 | .30 |

|

| ||||||

| Overweight/obese vs. Healthy weight | 1.401 | 0.963–2.038 | .08 | 1.84 | 1.218–2.78 | .004 |

| Age (10–20 vs. 2–9.9) | 1.464 | 0.992–2.16 | .06 | 1.644 | 1.053–2.569 | .03 |

| FAB type | .19 | .38 | ||||

| WBC (≥50 vs. <50) | 1.375 | 0.933–2.027 | .11 | 1.221 | 0.79–1.888 | .37 |

|

| ||||||

| Underweight vs. Healthy weight | 1.427 | 0.81–2.514 | .22 | 1.391 | 0.737–2.627 | .31 |

| Age (10–20 vs. 2–9.9) | 2.142 | 1.389–3.303 | <.001 | 2.32 | 1.396–3.854 | .001 |

| FAB type | .002 | <.001 | ||||

| WBC (≥50 vs. <50) | 2.045 | 1.257–3.329 | .004 | 1.348 | 0.748–2.431 | .32 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FAB, French-American-British classification; WBC, white blood cell

Because BMI criteria for underweight, healthy weight, and overweight/obese differ among studies,4, 15, 16 we evaluated OS and EFS by using Cox proportional hazard model with BMI percentile as a continuous variable in a spline model. There were significant non-linear association of BMI percentile with OS (P = .008, Fig. 2A) and EFS (P = .02, Fig. 2B). Patients with low or high BMI percentiles had worse OS and EFS. In multivariable analysis, BMI percentile had significant non-linear association with OS (P = .03, Fig. 2C) but not with EFS (P = .07, Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Association between BMI percentile and overall survival (OS, A and C) and event-free survival (EFS, B and D). Data were analyzed with Cox regression on BMI percentile as a continuous variable in a spline model, stratified by study protocol (A and B). In multivariable analysis, OS and EFS were modeled in the Cox proportional hazard regression with age, leukocyte count and FAB type as class predictor variables and BMI percentile as a continuous variable in a spline model, stratified by study protocol (C and D). In each panel, black line shows smoothing spline fit and gray lines show ±1 standard errors.

Causes of Treatment Failure

The prevalence of remission-induction failure or AML relapse among the three BMI groups was not significantly different: the mean (±SE) 5-year cumulative incidence of these events was 38.0±5.4% for overweight/obese patients, 40.0±10.1% for underweight patients, and 36.4±3.4% for those with healthy weight (P = .88). However, there was a significantly different cumulative incidence of grade 2 or higher infections (P = .03; Fig. 3A) and of grade 3 or higher infections (P = .006; Fig. 3B) among the three BMI groups. Both types of infection occurred more frequently during the early treatment phase in overweight/obese patients, whereas grade 4 infections tended to occur more frequently in underweight patients (P = .10; Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of grade 2 or higher infections (A), grade 3 or higher infections (B), and grade 4 infections (C). Data were analyzed after patients were classified into 3 groups of body mass index: underweight, healthy weight, overweight/obese.

Among the 314 patients, 35 died of toxicity, including 29 from infection (13 fungus including 7 Aspergillus and 4 Candida, 6 bacterial, 4 viral, and 6 organisms not identified), 5 from hemorrhage, and 1 from encephalopathy of unknown etiology. Infection was the cause of death for all the 14 overweight/obese and 5 of 6 underweight patients who died. The cumulative incidence of treatment-related mortality was significantly associated with BMI, with higher rates seen in underweight (3-year cumulative incidence, 24.0±8.8%) and overweight/obese patients (15.2±3.9%) than in healthy weight patients (7.4±1.9%, P = .009; Fig. 4). When the unhealthy BMI categories were individually compared to the healthy weight category, the cumulative incidence of treatment-related mortality was significantly higher in overweight/obese patients and underweight patients than in patients of healthy weight (P = .02 and .006, respectively). Although we did not examine the dose modifications due to toxicities or organ dysfunction in individual patients, we evaluated the duration of each chemotherapy course in each protocol. We did not find any statistically significant differences among the 3 BMI groups except during consolidation I of AML02: overweight/obese patients (median, 40 days; range, 22–149 days) had longer duration than either healthy weight (32.5 days; 21–88 days) or underweight (33 days; 24–54 days) patients did (P < .001).

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence of treatment-related mortality in 314 children with acute myeloid leukemia. Data were analyzed with patients were classified into 3 groups of body mass index: underweight, healthy weight, overweight/obese.

We compared the cumulative incidences of treatment-related mortality among patients treated on AML02 (2002–2008) to that of those treated on earlier trials (1987–2001). Although the difference was not statistically significant, there was a trend toward lower rates of treatment-related mortality for patients on AML02 compared to those on previous trials (3-year cumulative incidence, 7.9±2.2% vs. 13.8±2.8%, P = 0.07), suggesting that improvement in supportive care could results in improved outcomes. Even in AML02, however, overweight/obese patients still had higher rates of treatment-related mortality than healthy weight patients (3-year cumulative incidence, 13.0±4.7% vs. 5.5±2.4%, P = 0.12). When obese patients (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) were analyzed separately, their treatment-related mortality was 16.7±7.0% (P = 0.06).

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that overweight/obese patients with AML have a significantly worse survival. Excessive treatment-related mortality was seen in unhealthy BMI groups including both underweight and overweight/obese patients, while the rates of refractory leukemia and relapse were nearly identical across weight categories.

In pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, reports of the effect of BMI on patient outcome are conflicting. A study from the CCG showed that obese children (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) who were 10 years old or older had a significantly higher risk of events and relapses.15 In contrast, a study from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital found no differences in survival, event, or relapse rates among 4 BMI groups (underweight, BMI ≤ 10th percentile; normal 10th to 85th percentile; at risk of overweight, BMI 85th to 95th percentile; overweight, BMI ≥ 95th percentile).16 Reports on the impact of BMI in children with AML are in better agreement. A study from the CCG found that overweight (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) and underweight patients (BMI ≤ 10th percentile) had worse survival rates, a results primarily due to a higher rate of infection-related deaths during the first 2 courses of chemotherapy.4 Our current study confirms that overweight patients (BMI 85th to 95th percentile) as well as obese patients (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) have a worse survival, and suggests that their prognosis is unfavorable even in the context of contemporary supportive care. When comparing BMI data, the differences in category criteria must be taken into account. Currently, the CDC categorizes those with a BMI less than the 5th percentile as being underweight; however, the CCG AML study used the 10th percentile as the cutoff value for the category.4 Although our data showed that underweight patients had higher treatment-related mortality, a significantly lower survival was not seen. Because our more stringent criteria to define the underweight category might have limited the statistical power of our survival analysis, we evaluated the association between BMI percentile as a continuous variable and OS and EFS by using Cox regression model, which showed significant non-linear effect of BMI percentile on OS; patients with lower or higher BMI percentiles had worse OS. We also analyzed our data based on the 10th percentile cut-off, the criterion used in the CCG AML study (data not shown). Although the 5-year OS rate of underweight patients in this cut-off range was significantly lower than that of patients with healthy weight in univariate analysis, this difference was not significant in multivariable analysis, perhaps because of the lower number of patients examined in our study.

In contrast to the results of pediatric studies, those of 2 recent adult AML studies showed that obesity was not associated with worse survival or toxicities.17, 18 Although there is no clear explanation for this discrepancy between pediatric and adult findings, adults tend to have poorer results and higher-risk cytogenetic features that may overcome any association of BMI with outcome. Increasing BMI was strongly associated with APL but not with other subtypes of AML.19 The results of a recently published study of children and adults with APL showed that overweight/obese patients had a significantly higher relapse rate and incidence of differentiation syndrome.20 These results may suggest a relationship between obesity-related metabolic mediators and the pathogenesis of APL.

The prevalence of obesity has increased substantially over the past few decades among children and adolescents in the United States; 16.9% of the surveyed population were categorized as obese, and 31.7% were within overweight ranges of BMI for age.21 Therefore, obesity is a factor frequently encountered in pediatric oncology,22 with significantly increased percentages of obese patients in our recent protocols, especially among older children. Overweight/obese patients can have subtle immunologic abnormalities that could contribute to an increased likelihood of infection-related death.23 For example, adipocytokines, such as adiponectin, can suppress the synthesis of tumor-necrosis factor and interferon-γ, and induce the production of antiinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-1 receptor antagonist.23 Another adipocytokine, leptin can induce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor, IL-6, and IL-12.23 Overweight and obese patients may also have co-morbid conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension.22 Furthermore, physical examination of obese patients may be difficult and less effective, especially at identifying abdominal and peri-rectal pathology, which can affect outcomes.24 These issues necessitate detailed laboratory tests, including metabolic and immunologic profiles, along with nutrition assessment, dietary education, early use of prophylactic antibiotics, careful physical examination, and frequent clinic visits or inpatient care. Underweight patients also had worse treatment-related mortality in this study. Chronic malnutrition in developed countries, including the United States, is seen in about 1% of children.25 In addition to impaired physical growth and cognitive functions, the immune response is changed early in the course of significant malnutrition in a child.26 Associated problems include loss of delayed hypersensitivity; fewer T lymphocytes; impaired lymphocyte response; and impaired phagocytosis secondary to decreased complement, cytokines, and immunoglobulins. Therefore, underweight children with AML need immediate nutritional intervention to help prevent or reverse nutrition deficiencies as well as infection prophylaxis with antibiotics and supplemental immunoglobulin.

The data comparing the pharmacokinetics of various drugs in adult or pediatric obese patients to the pharmacokinetics in normal weight controls are conflicting,22 and few studies have examined this issue in underweight patients. Pharmacokinetics is affected by multiple factors such as plasma protein binding capacity, water- or lipid-solubility of the compound, liver metabolism, and the function of the excretion pathway. Hijiya et al.16 showed that intracellular levels of thioguanine nucleotides and methotrexate polyglutamates as well as systemic clearance of methotrexate, teniposide, etoposide, and low-dose cytarabine did not differ between 4 BMI groups of patients with pediatric ALL. In AML, however, high-dose cytarabine, the mainstay of treatment, is highly associated with alpha-streptococcus bacteremia,27 and similar pharmacokinetics studies have not been performed in obese or underweight patients. Doxorubicin had lower clearance and longer half-life in the most obese patients, resulting in a larger area-under-the-curve and more exposure although the pharmacokinetics of doxorubicinol, an active metabolite, did not differ among patient groups.28 Prospective pharmacokinetic studies of medications used in AML, especially cytarabine, anthracycline, and etoposide are needed. In most cases, neither we nor CCG modified the chemotherapy dosing on the basis of BMI or weight in AML studies.4 However, pharmacokinetics-guided dosing may reduce toxicity in those AML patients with an unhealthy BMI.

In conclusion, children with an unhealthy BMI (i.e., underweight, overweight, and obese) have lower survival rates due to treatment-related mortality. BMI-oriented supportive care should be provided to these patients during treatment for AML.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant P30 CA021765-30 from the National Institutes of Health and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). Ching-Hon Pui is an American Cancer Society Professor.

The authors would like to thank Cherise Guess, PhD, for editorial assistance and Soheil Meshinchi, MD, Barbara Degar, MD, and Gladstone Airewele, MD for participating in AML02 study.

Footnotes

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tsukimoto I, Tawa A, Horibe K, et al. Risk-stratified therapy and the intensive use of cytarabine improves the outcome in childhood acute myeloid leukemia: the AML99 trial from the Japanese Childhood AML Cooperative Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(24):4007–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubnitz JE, Inaba H, Dahl G, et al. Minimal residual disease-directed therapy for childhood acute myeloid leukaemia: results of the AML02 multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(6):543–52. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70090-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimwade D, Hills RK. Independent prognostic factors for AML outcome. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009:385–95. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lange BJ, Gerbing RB, Feusner J, et al. Mortality in overweight and underweight children with acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA. 2005;293(2):203–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnaout MK, Radomski KM, Srivastava DK, et al. Treatment of childhood acute myelogenous leukemia with an intensive regimen (AML-87) that individualizes etoposide and cytarabine dosages: short- and long-term effects. Leukemia. 2000;14(10):1736–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krance RA, Hurwitz CA, Head DR, et al. Experience with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine in previously untreated children with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic diseases. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(11):2804–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubnitz JE, Crews KR, Pounds S, et al. Combination of cladribine and cytarabine is effective for childhood acute myeloid leukemia: results of the St Jude AML97 trial. Leukemia. 2009;23(8):1410–6. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruskal WH, Wallis WA. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1952;47(260):583–621. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan ELMP. Non-parametric estimation for incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples. Br J Cancer. 1977;35(1):1–39. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1977.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50(3):163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox D. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Annals of Statistics. 1988;16:1141–54. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray RJ. Spline-based tests in survival analysis. Biometrics. 1994;50(3):640–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butturini AM, Dorey FJ, Lange BJ, et al. Obesity and outcome in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(15):2063–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.7792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hijiya N, Panetta JC, Zhou Y, et al. Body mass index does not influence pharmacokinetics or outcome of treatment in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2006;108(13):3997–4002. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medeiros BC, Othus M, Estey EH, Fang M, Appelbaum FR. Impact of body-mass index in the outcome of adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2012 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.056390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HJ, Licht AS, Hyland AJ, et al. Is obesity a prognostic factor for acute myeloid leukemia outcome? Ann Hematol. 2012;91(3):359–65. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1319-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estey E, Thall P, Kantarjian H, Pierce S, Kornblau S, Keating M. Association between increased body mass index and a diagnosis of acute promyelocytic leukemia in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 1997;11(10):1661–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breccia M, Mazzarella L, Bagnardi V, et al. Increased BMI correlates with higher risk of disease relapse and differentiation syndrome in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with the AIDA protocols. Blood. 2012;119(1):49–54. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-369595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):242–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers PC, Meacham LR, Oeffinger KC, Henry DW, Lange BJ. Obesity in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;45(7):881–91. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Adipocytokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(10):772–83. doi: 10.1038/nri1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiernik PH, Serpick AA. Factors effecting remission and survival in adult acute nonlymphocytic leukemia (ANLL) Medicine (Baltimore) 1970;49(6):505–13. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Onis M, Blossner M, Borghi E, Frongillo EA, Morris R. Estimates of global prevalence of childhood underweight in 1990 and 2015. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2600–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandra RK. Nutrition and the immune system from birth to old age. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56 (Suppl 3):S73–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamis AS, Howells WB, DeSwarte-Wallace J, Feusner JH, Buckley JD, Woods WG. Alpha hemolytic streptococcal infection during intensive treatment for acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the Children’s cancer group study CCG-2891. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(9):1845–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.9.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodvold KA, Rushing DA, Tewksbury DA. Doxorubicin clearance in the obese. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6(8):1321–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.8.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]