Abstract

The phonological processing skills of 24 pre-lingually deaf 8- and 9-year-old experienced cochlear implant users were measured using a nonword repetition task. The children heard recordings of 20 nonwords and were asked to repeat each pattern as accurately as possible. Detailed segmental analyses of the consonants in the children’s imitation responses were carried out. Overall, 39% of the consonants were imitated correctly. Coronals were produced correctly more often than labials or dorsals. There was no difference in the proportion of correctly reproduced stops, fricatives, nasals, and liquids, or voiced and voiceless consonants. Although nonword repetition performance was not correlated with the children’s demographic characteristics, the nonword repetition scores were strongly correlated with other measures of the component processes required for the immediate reproduction of a novel sound pattern: spoken word recognition, language comprehension, working memory, and speech production.

Keywords: Cochlear implants, nonword imitation, segmental analysis

Introduction

The remarkable ability of children as young as 2 years of age to spontaneously imitate the speech of adult models has helped researchers in developing theories of child language acquisition (e.g. Slobin and Welsh, 1973). Similarly, elicited nonword repetition tasks have been used by researchers to provide new insights into the language learning skills of adults and to study children with various language-learning difficulties (Edwards and Lahey, 1998). Studies have revealed that nonword repetition accuracy appears to be correlated with such skills as adults’ ability to learn foreign-language lexical items (Papagno, Valentine and Baddeley, 1991) and children’s ability to learn the nonword names of toys (Gathercole and Baddeley, 1990).

In the present study, we examined the nonword repetition performance of 24 hearing-impaired children who were experienced cochlear implant users. The nonwords were a subset of the 40 nonwords in the Children’s Test of Nonword Repetition (CNRep), a test originally designed to assess individual differences in phonological working memory in young normal-hearing children (Gathercole, Willis, Baddeley and Emslie, 1994; Gathercole and Baddeley, 1996). The children were asked to listen to a nonword pattern and repeat it back aloud after a single auditory-only exposure. They were alerted in advance that the stimuli would be unfamiliar, and were told to imitate the items to the best of their ability.

Although nonword repetition may appear to be relatively simple at first glance, it actually involves several component processes including: auditory and phonological encoding, short-term storage of the target item in working memory, and articulatory planning and speech production. In order to be able to imitate a nonword pattern, a child needs to perform reasonably well in each of these component processes. After four or five years of experience with a cochlear implant, we assumed that many of these children possessed a phonological system sufficient to allow them to produce nonword imitations that closely resembled the targets. Furthermore, we expected that individual differences in the children’s performance on a nonword imitation task such as the one used in the present study might be related to individual differences in their performance on other tasks measuring the component processes of speech perception, speech production, and working memory.

Preliminary results from 14 of the children in this study were presented in Cleary, Dillon and Pisoni (2002). Suprasegmental analyses of the present set of imitation responses have already been reported by Carter, Dillon, and Pisoni (2002). In that study, we found that 64% of imitations contained the correct syllable number and 61% had correct placement of primary stress. We also observed significant correlations between the children’s imitation of these two suprasegmental properties, and their performance on other speech, language and working memory measures. In addition, the children’s performance was strongly correlated with imitation accuracy ratings obtained from normal-hearing adults. Our findings were consistent with Hudgins and Numbers’ (1942) results showing that the speech rhythm (or suprasegmental properties) of 192 8- to 20-year-old deaf students was correlated with measures of speech intelligibility. Hudgins and Numbers also found a strong correlation between speech intelligibility and consonant production. These earlier findings encouraged us to examine the consonant production accuracy of the nonword imitation responses obtained in the present study.

The results of other speech production studies reported by Dawson, Blamey, Dettman, Rowland, Barker, Tobey, Busby, Cowan and Clark (1995) and Sehgal, Kirk, Svirsky, Ertmer and Osberger (1998) indicated that children who use CIs produced labial consonants correctly more often than consonants with other places of articulation. Affricates were produced correctly less often than consonants with any other manner of articulation. Similarly, in a study of the spontaneous speech of 14 pre-lingually deaf children who had used CIs for 1 year, Osberger, Robbins, Berry, Todd, Hesketh and Sedey (1991) found that the children correctly produced bilabial stops and nasal /m/ most often, followed by alveolar and velar stops, followed by fricatives, then liquids, and lastly glides.

Based on these results, we expected that the children in our study would imitate labials correctly more often than consonants with other places of articulation, and that the target stops in our study would be produced correctly more often than fricatives, and fricatives more often than liquids. In addition to presenting the results on the imitation accuracy of the consonants in the target nonwords, we also report correlations between the children’s nonword repetition performance and scores on other speech and language measures as well as several demographic variables.

Method

Subjects

The CI users were 24 children who participated in the Central Institute for the Deaf (CID) ‘Cochlear Implants and Education of the Deaf Child’ project in 1999 or 2000 (see Geers and Brenner, 2003). Although 88 children participated in the study, the 24 children described in the present study are the subset who provided a response to all 20 target nonword stimuli (see Cleary et al., 2002; Dillon, Burkholder, Cleary and Pisoni, under review). Demographic information about the children is shown in table 1. Responses from 15 males and nine females were analysed. Nineteen of the participants were congenitally deaf; the other five children were deaf by the age of 3. The average duration of deafness prior to implantation was 3.0 years (SD 1.1, range 0.7–5.4 years). At the time of testing, the children had used their cochlear implant for an average of 5.4 years (SD 0.8, range 3.8–6.6 years). The average chronological age of the children was 8.8 years (SD 0.5, range 8.2–9.9 years). Children who primarily used oral communication and children who primarily used total communication (TC) were included in the group. The average Communication Mode score was 4.4 (SD 1.4, range 2–6). This score is the average of scores assigned by parental report, at the time of testing, for five intervals: prior to implantation, the first, second, and third year after implantation, and the current year of testing. For each interval, a ranking using the following scale was assigned to each child: 1 point for TC with emphasis on sign, 2 points for TC with equal emphasis on sign and speech, 3 for TC with emphasis on speech, 4 for cued speech, 5 for auditory-oral communication, and 6 for auditory-verbal communication. Thus, an average communication mode score of 3.5 or lower indicates that the child’s method of communication was primarily TC, while a score of 3.6 or higher indicates that the child’s communication setting was primarily oral (Geers and Brenner, 2003). Accordingly, 18 of the children in the present study used oral communication and six of the children used total communication. Twenty-three of the children were users of a Nucleus 22 CI and the SPEAK coding strategy. One child used a Clarion CI.

Table 1.

Demographic information for the 24 children analysed

| Child ID # | Gender | Age at onset of deafness (in months) | Duration of deafness (in years) | Duration of CI use (in years) | Chronological Age (in years) | Communication Mode Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00102 | m | 0 | 3.3 | 5.8 | 9.1 | 5.2 |

| 00105 | m | 0 | 3.9 | 4.8 | 8.7 | 5.0 |

| 00109 | m | 0 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 8.2 | 3.6 |

| 00110 | m | 0 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 9.5 | 3.4 |

| 00207 | f | 0 | 2.1 | 6.1 | 8.3 | 4.8 |

| 00208 | m | 0 | 2.1 | 6.1 | 8.3 | 4.6 |

| 00213 | f | 36 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 9.4 | 6.0 |

| 00307 | m | 18 | 0.7 | 6.0 | 8.2 | 5.2 |

| 00309 | m | 0 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 8.7 | 2.6 |

| 00314 | m | 0 | 4.5 | 5.4 | 9.9 | 2.0 |

| 99101 | m | 0 | 3.4 | 5.6 | 9.0 | 5.4 |

| 99103 | f | 0 | 2.2 | 6.5 | 8.7 | 6.0 |

| 99104 | m | 0 | 2.9 | 6.6 | 9.5 | 5.0 |

| 99105 | f | 0 | 3.2 | 5.3 | 8.5 | 4.6 |

| 99108 | f | 0 | 2.4 | 5.9 | 8.3 | 5.8 |

| 99205 | f | 0 | 3.0 | 5.4 | 8.3 | 4.2 |

| 99207 | m | 0 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 8.4 | 4.0 |

| 99211 | m | 10 | 2.7 | 4.7 | 8.2 | 2.2 |

| 99214 | m | 24 | 1.7 | 4.5 | 8.2 | 2.0 |

| 99301 | m | 18 | 1.6 | 6.0 | 9.0 | 6.0 |

| 99304 | m | 0 | 2.6 | 6.4 | 9.0 | 6.0 |

| 99305 | f | 0 | 3.3 | 5.1 | 8.4 | 5.6 |

| 99307 | f | 0 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 9.1 | 4.2 |

| 99312 | f | 0 | 3.2 | 6.5 | 9.7 | 2.4 |

| Mean | (SD): | 4.4 (9.7) | 3.0 (1.1) | 5.4 (0.8) | 8.8 (0.5) | 4.4 (1.4) |

Stimulus materials

Twenty nonwords from the CNRep test were used as stimuli in the present study (see Carlson, Cleary and Pisoni, 1998). The stimuli included five nonwords at each of four lengths: two, three, four, and five syllables. Each of the nonwords is shown with its phonemic transcription in table 2. The nonwords used in the present study were originally designed to assess individual differences in phonological working memory in young normal-hearing children (Gathercole et al., 1994; Gathercole and Baddeley, 1996). Although the nonwords were balanced in terms of the number of syllables, the stimuli were not balanced for syllable structure, consonant or vowel features, or stress patterns. Nevertheless, as shown in table 3, the segments contained in the target nonwords included consonants with a range of manner features (stops, fricatives, an affricate, nasals, and liquids), consonants with all three gross places of articulation (labial, coronal, and dorsal), and both voiced and voiceless consonants.

Table 2.

The 20 nonwords used in the present study (see Carlson et al., 1998), adapted from Gathercole et al. (1994)

| Number of syllables | Target nonword orthography | Target nonword transcription |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | ballop | ˈbæ.ləp |

| prindle | ˈpɹın.dl | |

| rubid | ˈɹuˌbıd | |

| sladding | ˈslæ.diŋ | |

| tafflist | ˈtæ.flıst | |

|

| ||

| 3 | bannifer | ˈbæ.nɚ̩f |

| berrizen | ˈbɛ.ɹəˌzın | |

| doppolate |

|

|

| glistering | ˈglı.stɚ.iŋ | |

| skiticult | ˈskı.ɾəˌkʌlt | |

|

| ||

| 4 | comisitate |

|

| contramponist | kənˈtɹæm.pəˌnıst | |

| emplifervent | ɛmˈplı.fɚˌvɛnt | |

| fennerizer |

|

|

| penneriful | pəˈnɛ.ɹ əˌfʌl | |

|

| ||

| 5 | altupatory | ælˈtu.pəˌtɔ. ɹi |

| detratapillic | diˈtɹæ. ɾəˌpı.lık | |

| pristeractional | ˈpəı.stɚæk.ʃə.nl | |

| versatrationist |

|

|

| voltularity | ˈvɑl.tʃʊˌlɛ.ɹəˌti | |

Table 3.

The 112 target consonants in the 20 nonwords

| Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | 9 /p/ | 17 /t/ | 6 /k/ |

| voiced | 4 /b/ | 5 /d/, 2 /ɾ/ | 1 /g/ | |

| Fricative | voiceless | 5 /f/ | 9 /s/, 2 /ʃ/ | — |

| voiced | 3 /v/ | 2 /z/ | — | |

| Affricate | voiceless | — |

|

— |

| Nasal | voiced | 3 /m/ | 10 /n/ | 2 /ŋ/ |

| Liquid | voiced | — | 14 /l/, 17 /ɹ/ | — |

Procedure

For the present study, the CNRep nonwords were re-recorded by a female speaker of American English (Carlson et al., 1998) and presented auditorily to the children via a desktop speaker (Cyber Acoustics MMS-1) at approximately 70 dB SPL. In a few cases, the signal level was increased at the child’s request. Each child heard the nonword stimuli played aloud one at a time, in random order. The children were told that they would hear a ‘funny word’ and were instructed to repeat it back as well as they could. Their imitation responses were recorded via a head-mounted microphone (Audio-Technica ATM75) onto digital audio tape using a TEAC DA-P20 tape deck. The DAT tapes were later digitized and segmented into individual sound files. Each imitation response was independently transcribed by two trained transcribers. Intertranscriber agreement was 93%. Discrepancies were resolved by a third transcriber.

Scoring

Previous studies of nonword repetition have measured performance using a binary scoring procedure (e.g. Gathercole, 1995; Avons, Wragg, Cupples, and Lovegrove, 1998). The examiners credited the children with either 1 point or 0 points for each response. Any error, even if the error involved only a single segment (i.e. phoneme), usually resulted in no credit. Provisions have sometimes been made for predictable patterns of immature articulation in very young children. However, the children with CIs in the present study produced many segmental errors, so that out of a total of 480 possible imitation responses, only 5% of the imitations would have received full credit using this binary scoring procedure. The traditional scoring procedure was therefore not suitable for use in the present study. Instead, we calculated an accuracy score for each segment. If the child’s response segment was the same English phoneme as the corresponding target, then he/she received 1 point. Three additional accuracy scores were also computed for the consonants. For these scores, points were assigned based on the featural accuracy of the child’s imitation segment. The four accuracy scores are described below.

Segment score: an imitation segment was counted as correct and given 1 point if the segment was correctly reproduced. For example, for a target /p/, if a child produced a /p/, he/she was given 1 point. The production of any other phoneme received 0 points.

Manner Feature score: an imitation consonant was counted as correct and given 1 point if the consonant was correct in terms of manner of articulation. For example, for a target /p/, which is a stop, if a child produced any stop consonant, such as [p], [b], [t] or [d], he/she was given 1 point. If, for a target /p/, a child produced a fricative, affricate, or any segment whose manner was other than a stop, he/she received 0 points.

Voice Feature score: an imitation consonant was counted as correct and given 1 point if the consonant was correct in terms of voicing. For example, for a target /p/, which is voiceless, if a child produced any voiceless consonant, he/she was given 1 point. If, for a target /p/, a child produced an imitation response with a voiced segment, he/she received 0 points.

Place Feature score: an imitation consonant was counted as correct and given 1 point if the place feature of the consonant was correct in terms of the three gross places of articulation (labial, coronal and dorsal). For example, for a target /p/, which is a labial, if a child produced any labial consonant, such as [p], [b], [f ] or [v], he/she received 1 point. If, for a target /p/, a child produced a coronal or dorsal, he/she received 0 points.

For each imitation, the segment score for all of the consonants was summed and divided by the number of consonants in the target nonword. This calculation results in a ‘segmental accuracy score’ for each imitation. The segmental accuracy scores assigned to all of the imitations produced by a given child were averaged in order to calculate a mean segmental accuracy score per child. In addition, the segmental accuracy scores assigned to all of the imitations provided in response to a given target nonword were averaged in order to calculate a mean segmental accuracy score per target nonword.

Results

Nonword repetition accuracy results

The children reproduced only 5% of the target nonwords correctly without errors. Overall, 39% of the consonants were reproduced correctly. 56% of the target consonants were imitated correctly in terms of manner, 61% were correct in terms of place, and 66% were correct in terms of voicing. To gain further insights into whether the children had more difficulty imitating certain consonant features more than others, we examined the children’s imitations of each of the features more closely. (The target affricate was not included in the following analyses because there was only one affricate in the stimulus set.)

The manner feature was imitated correctly with similar levels of accuracy across the four target manners of stop, fricative, nasal and liquid (59%, 58%, 55% and 51%, respectively). The children also produced imitations with the correct voicing for an equal proportion of target voiceless and target voiced consonants (66%). Two one-way ANOVAs revealed that neither the specific manner feature nor the specific voicing feature of the target consonant significantly affected the number of imitations produced with the correct manner or voicing, respectively.

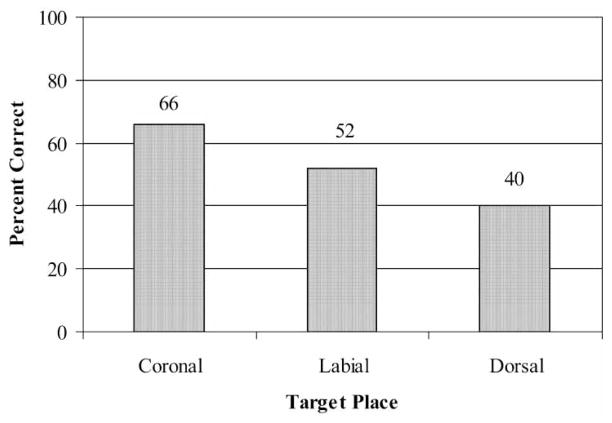

As shown in figure 1, the children correctly imitated the place feature of a greater proportion of target coronals than labials or dorsals (66% versus 52% and 40%, respectively). A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of target place of articulation (F(2, 109) = 12.1, p<0.001). Post-hoc Tukey tests indicated that target coronal consonants were reproduced with the correct place more often than target labials or dorsals (p<0.01 and p<0.001, respectively). There was no significant difference between the proportion of target labials and dorsals reproduced with the correct place.

Figure 1.

Per cent of target consonants imitated correctly in terms of place of articulation.

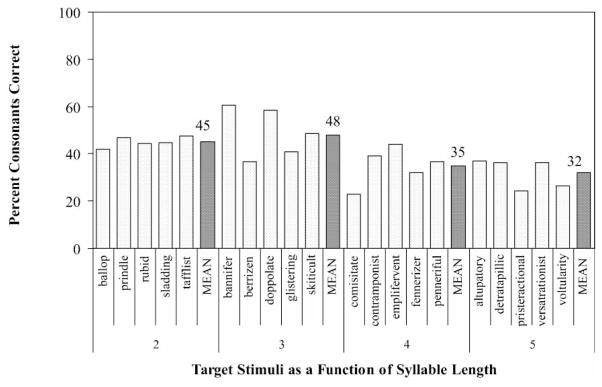

We also carried out analyses by item and by subject. For the item analysis, we computed mean segmental accuracy scores for each target nonword (averaged across children). We also calculated the mean segmental accuracy score for each target syllable length (two, three, four and five). The results of the item analysis, shown in figure 2, revealed that the segmental accuracy scores differed depending on the target nonword. The shorter target nonwords (two- and three-syllables) tended to be imitated better than the longer target nonwords (four- and five-syllables). A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of syllable length (F(3, 16)=4.3, p<0.05). Post-hoc Tukey tests revealed a significant difference between the two-syllable nonwords and the five-syllable nonwords (p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Mean segmental accuracy score for each target nonword as a function of syllable length, averaged over children.

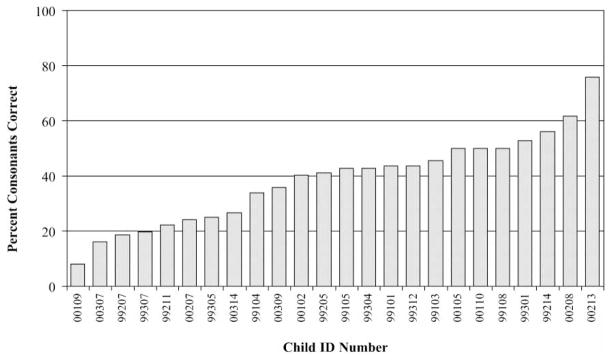

We also computed mean segmental accuracy scores for each child (averaged over the nonwords), shown in figure 3. The individual children’s segmental accuracy scores exhibited a great deal of variation, ranging from 8% to 76%. The wide range of scores for the 24 children demonstrates that, despite the fact that all of these children produced a response to each of the stimuli, they still displayed a great deal of variability on this task.

Figure 3.

Mean segmental accuracy score for each child, averaged over target nonwords.

Correlational analyses

Demographics

We were also interested in the relations between the children’s imitation responses and their demographic characteristics. To examine this, we computed correlations between the segmental accuracy scores and the following demographic variables: age at onset of deafness, duration of deafness prior to implantation, age at implantation, duration of CI use, age at time of testing, gender, number of active electrodes, and degree of exposure to an oral-only communication environment based on Communication Mode scores. None of these demographic variables were significantly correlated with the segmental accuracy scores.

As part of the larger project carried out at CID (Geers and Brenner, 2003), the 24 children in this study also participated in tasks that provided measures of their performance on the component processes of nonword repetition. These scores provided an unusual opportunity to assess the relationship between nonword repetition and several component processes. Correlations between the children’s scores on these outcome and process measures and their segmental accuracy scores are shown in table 4.

Table 4.

Correlations between the children’s mean segmental accuracy scores and their scores on several speech and language outcome and process measures.

| Correlation r-values | |

|---|---|

| Outcome and Process Measures of Performance | Segmental Accuracy |

| Word Recognition | |

| Word identification, closed-set, pointing response | |

| Word Intelligibility by Picture Identification (WIPI) | +0.72** |

| Word identification, open-set, spoken repetition | |

| Lexical Neighborhood Test, Easy Words (LNTe) | +0.80** |

| Word identification, open-set, spoken repetition | |

| Lexical Neighborhood Test, Hard Words (LNTh) | +0.80** |

| Word identification, open-set, spoken repetition | |

| Lexical Neighborhood Test, Multisyllabic Words (mLNT) | +0.77** |

| Sentence identification, open-set repetition of target sentence | |

| Bamford-Kowal-Bench (BKB) | +0.80** |

| Language Comprehension | |

| Closed set, receptive language comprehension of words and sentences | |

| Test of Auditory Comprehension of Language-Revised (TACL-R) | +0.69** |

| Phonetic Feature Discrimination | |

| Perception of speech pattern contrasts | |

| Video Game for Assessing speech pattern contrasts (VIDSPAC) | +0.34 |

| Working Memory | |

| Forward Digit Span | |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-III) Auditory Digit Span Subtest, Forward Recall of Digit-Name Lists | +0.64** |

| Backward Digit Span | |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-III) Auditory Digit Span Subtest, Backward Recall of Digit-Name Lists | +0.30 |

| Speech Production | |

| Speech Intelligibility | |

| McGarr Sentence Intelligibility Test | +0.82** |

| Speaking Rate | |

| McGarr Mean Duration of 3-Syllable Sentences (log, msec) | −0.63** |

| McGarr Mean Duration of 5-Syllable Sentences (log, msec) | −0.81** |

| McGarr Mean Duration of 7-Syllable Sentences (log, msec) | −0.84** |

p≤0.001

Speech and language outcome measures

Several of the assessment tasks provided measures of speech perception and spoken word recognition. The Word Intelligibility by Picture Identification (WIPI) test is a closed-set test of spoken word identification that requires a pointing response (Ross and Lerman, 1979). The Lexical Neighborhood Test (LNT; Kirk, Pisoni and Osberger, 1995) is an open-set test of spoken word identification consisting of ‘lexically easy’ (LNTe) and ‘lexically hard’ (LNTh) lists of monosyllabic words. The Multisyllabic Lexical Neighborhood Test (mLNT) contains multisyllabic words of two or three syllables. The Bamford-Kowal-Bench Sentence List Test (BKB) is an open-set task requiring spoken repetition of a target sentence (Bench, Kowal and Bamford, 1979). As shown in table 4, strong correlations were obtained between the children’s segmental accuracy scores and their scores on the WIPI (r=+0.72, p<0.001), LNTe (r=+0.80, p<0.001), LNTh (r=+0.80, p<0.001), mLNT (r=+0.77, p<0.001) and BKB (r=+0.80, p<0.001). Children who scored higher on measures of spoken word recognition tended to imitate more consonants correctly in the nonword repetition task.

The battery of tests also included the Test of Auditory Comprehension of Language Revised (TACL-R), a language comprehension measure that assesses children’s receptive vocabulary, morphology, and syntax (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1985). The children’s segmental accuracy scores were highly correlated with the TACL-R scores (r=+0.69, p<0.001). Better performance on the nonword repetition task used in the present study corresponds to higher language comprehension scores in terms of receptive vocabulary, morphology, and syntax.

A measure of phonetic feature discrimination using the VIDSPAC was also obtained. The VIDSPAC is a video game test that was specifically designed to measure hearing-impaired children’s ability to perceive speech feature contrasts (Boothroyd, 1997). The children’s VIDSPAC scores were not significantly correlated with their segmental accuracy scores.

As part of the larger study at CID, measures of working memory were also obtained from the children using the WISC Digit Span Supplementary Verbal Sub-test of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Third Edition (WISC-III) (Wechsler, 1991). The WISC has both a ‘digits forward’ subtest and a ‘digits backward’ subtest. For the forward digit span task, a child listens to and repeats back lists of digits as spoken live-voice by the experimenter at a rate of approximately one digit per second (WISC-III Manual, Wechsler, 1991). Two lists are administered at each list length, beginning with two digits. The list length is increased one digit at a time until the child fails to correctly repeat both lists administered at a given length. The child receives points for correct repetition of each list, with no partial credit. The backward digit span task differs from the forward digit span task only in that the children are asked to repeat back the digits that they heard in backwards order, starting with the last digit that was presented to them, and finishing with the first digit that was presented.

We found strong correlations between the children’s segmental accuracy scores in the nonword repetition task and their forward digit spans (r=+0.64, p<0.001). Longer digit spans were associated with higher nonword repetition scores. The correlations between the children’s backward digit spans and segmental accuracy were not significant. Backward digit span is often considered a measure of executive function, and is usually found not to correlate with measures that tap into the same cognitive processes as forward digit span, which is a measure of phonological coding and verbal rehearsal (see Lezak, 1983; Li and Lewandowsky, 1995; Rosen and Engle, 1997; Cowan, Saults, Elliot and Moreno, 2002; Engle, 2002).

Measures of speech intelligibility and speaking rate were also obtained from each child using the 36 McGarr sentences (McGarr, 1983). Each child was provided with spoken and/or signed models of each sentence as well as the printed text, and was prompted to speak as intelligibly as possible. Utterances were digitized, edited and stored in individual wave files. Audio samples were played to judges who were naive to deaf speech. For every child, each of his/her 36 sentences were heard by three different judges. Each judge only heard one sentence from any given child. Thus, every child received a score from 3 different judges for each of his/her 36 sentences, and these 108 scores were averaged to calculate a mean intelligibility score (Tobey, Geers, Douek, Perrin, Skellett, Brenner and Torretta, 2000).

In addition, overall sentence duration was acquired by examining the waveform files of the individual sentences and placing cursors at the initial and final acoustic segments (Tobey et al., 2000). In an earlier study, sentence durations were used as a measure of speaking rate: longer sentence durations indicated slower speaking rates. Pisoni and Geers (2000) found that CI children’s speaking rate on the McGarr sentences was strongly correlated with measures of working memory as well as speech intelligibility. We also examined the relations between nonword repetition performance and speech intelligibility, and nonword repetition performance and speaking rate (as indexed by average sentence duration). We found strong correlations between the children’s segmental accuracy scores and speech intelligibility (r=+0.82, p<0.001). The children who produced more intelligible speech on the McGarr task also tended to reproduce more consonants correctly in their nonword repetitions. We also observed strong negative correlations between the children’s segmental accuracy scores and their speaking rates for the three-syllable sentences (r=−0.63, p<0.001), for the five-syllable sentences (r=−0.81, p<0.001), and for the seven-syllable sentences (r=−0.84, p<0.001). These negative correlations suggest that the children who spoke more slowly in the McGarr task tended to perform more poorly on the nonword repetition task.

Discussion

Studies of the speech and language skills of hearing-impaired children who use cochlear implants consistently report a wide range of individual variability on clinical outcome measures of speech and language (Kirk, 2000). Although previous studies have found that about 35–65% of the individual differences in pediatric CI users’ performance can be explained by demographic variables such as duration of deafness, length of device use, and age at implantation (Miyamoto, Osberger, Todd, Robbins, Stroer, Zimmerman-Philips and Carney, 1994; Dowell, Blamey and Clark, 1995; Blamey, Sarant, Paatsch, Barry, Bow, Wales, Wright, Psarros, Rattigan and Tooher, 2001; Sarant, Blamey, Dowell, Clark and Gibson, 2001), a substantial portion of the variation among children has yet to be explained (Pisoni, 2000). We have been interested in the factors that underlie these individual differences (Pisoni and Cleary, in press). If we can identify some of the factors that are responsible for the variation in performance, we may be able to recommend specific changes that will help the poorer performing children achieve optimal levels of speech and language performance with their cochlear implants.

In trying to understand the variability in outcome measures obtained with the pediatric CI users, we examined a large body of research on individual differences in the language development of young normal-hearing children (e.g. Gathercole and Adams, 1993; Gathercole and Baddeley, 1993). A number of pieces of evidence suggest that individual differences in phonological coding and verbal working memory contribute to variability in skills such as vocabulary acquisition and language among normally-developing children (Gathercole and Adams, 1993; Gathercole and Baddeley, 1993). The task most widely used over the last decade to study phonological processing skills and verbal working memory is the nonword repetition task, the task employed in the present study.

Although performance on the nonword repetition task reflects individual differences in the component processes of initial sensory encoding, maintenance in phonological working memory, and speech production, the present findings demonstrate that it is useful to include this nonword repetition measure among other outcome measures in the study of children with cochlear implants. Measures of nonword repetition are potentially important because unlike other routine clinical outcome measures, imitation skills reflect a child’s ability to rapidly transform sensory input into what he/she perceives to be an ‘equivalent’ articulatory-motor output. This processing skill, we would argue, is something separable from perception and production, because it reflects a series of rapidly executed phonological processing operations that involve ‘decomposition’ and translation of a sensory-perceptual input into a phonological representation and then ‘reassembly’ of a phonological representation into an articulatory programme used in speech production (see for discussion, Pisoni and Cleary, in press).

The ability of pediatric CI users to utilize their knowledge of the phonological patterns of the ambient language in order to reproduce spoken nonword stimulus patterns has not, to our knowledge, been previously explored in any great detail. However, because all spoken words that children with cochlear implants learn to recognize must have been, at one point, nonwords to these children, we believe that it may be useful to understand how individual children in this clinical population process novel auditory patterns.

Use of a nonword repetition task with hearing-impaired children does, however, raise a number of additional complicated issues regarding how to interpret performance on this task given that only 5% of imitations were completely correct. The present research project was undertaken with the conviction that if a detailed characterization of the accuracy patterns could be accomplished, we would then be able to investigate the relationship between different component processes of performance. We therefore carried out a linguistic analysis of the responses based on the phonological features of the target phonemes. We attempted to account for observed patterns of performance through comparisons with previous results from this population on other tasks that involve primarily perception or primarily spontaneous production. Relations between perception and production and nonword repetition performance were also examined by looking at intercorrelations between nonword repetition performance and several independently obtained measures of speech perception and articulation.

Our ability to conduct these analyses was, rather obviously, predicated on the assumption that most children sampled from in this clinical population would be able to do the nonword repetition task well enough to obtain a measurable score. Fortunately, we did find that even when nonword stimuli were presented to pediatric CI users in an auditory-only mode, 24 of the original 88 participants provided a response to all 20 of the stimuli, and almost all of the other children were able to provide some attempt at a response on at least 75% of all trials. The children were clearly not performing at floor on this task.

Detailed examination of the children’s consonant feature production revealed several ‘null results’ with regard to the manner and voicing features of target segments. First, we found that the children did not perform better in response to target consonants of particular manners of articulation (e.g. no advantage was observed for stops over fricatives). Second, we also found no evidence that the voicing feature was produced correctly more often for voiced or voiceless target consonants. These results were not surprising given earlier findings. Neither Dawson et al. (1995) nor Sehgal et al. (1998) found large differences between children’s ability to produce consonants of different manners or voicing.

However, with regard to place of articulation, we found that coronal consonants were imitated correctly by the children more often than labial and dorsal consonants. This finding conflicts with results of previous studies by Dawson et al. (1995) and Sehgal et al. (1998), as well as Tobey, Geers and Brenner (1994). These researchers reported that labial consonants were produced correctly more often than consonants with other places of articulation. The tasks employed in Dawson et al. and Sehgal et al. were, however, open-set word recognition tasks in which the children were asked to repeat real words that were presented to them. Thus, the stimuli and responses in these two studies were familiar English words, while the stimuli and responses in the present study were novel nonwords.

The children in our study had not been exposed to the nonword stimuli before and therefore had not had the opportunity to benefit from the salient visual cues provided by the lips when a target labial consonant is produced. It is possible that the children in Dawson et al. (1995) and Sehgal et al. (1998) produced labial consonants correctly more often than other consonants simply because they had had previous opportunities to learn the real words that served as stimuli and were able to benefit from the visual cues provided by the salient lip closure of labial consonants. In addition, the stimuli in Dawson et al. and Sehgal et al. were presented to the children live-voice by an examiner. In our study, the children heard only audio recordings of the nonword stimuli presented over a loudspeaker. A live-voice auditory-visual presentation format was also used in the Tobey et al. (1994) study. Thus, the children in these previous studies may have been able to benefit from the presence of visual cues, especially the lip closure of labial consonants (see Lachs, Pisoni and Kirk, 2001).

In addition to the wide range of variability observed across individual children, we also found variability across the nonword targets. The children’s nonword repetition performance was significantly affected by the syllable length of the target. Imitations of the two-syllable target nonwords received significantly better scores than imitations of the five-syllable target nonwords. The children’s imitations of two- and three-syllable target nonwords also tended to be better than their imitations of four-syllable target nonwords, but these differences did not reach significance. These findings are consistent with our earlier results on the suprasegmental aspects of the same 24 children’s nonword repetitions (Carter et al., 2002). In that study, we found that children produced suprasegmental features of their imitations correctly in response to shorter target nonwords more often than longer target nonwords. Our results also replicate the earlier findings reported by Gathercole (1995), in which normal-hearing children produced correct imitations of shorter nonwords more often than longer nonwords. Longer nonwords appear to place a greater load on phonological working memory and the verbal rehearsal processes of the phonological loop that maintains information in immediate memory for brief periods of time.

Variability among the children in nonword repetition performance was related in a systematic manner to their performance on other tasks designed to measure the phonological processes similar to those used in carrying out the nonword repetition task: spoken word recognition and speech perception, language comprehension, phonological working memory, and speech production. Overall, better nonword repetition performance was associated with higher spoken word recognition scores, higher language comprehension scores, longer forward digit spans, higher speech intelligibility scores and faster speaking rates. The strong relations among the children’s scores reflect the close correspondence between the children’s speech perception, working memory, speech production, and language skills. The strong correlation between the children’s nonword repetition performance and their forward digit spans, a measure of phonological working memory capacity, is not surprising given that both measures were developed to measure similar processing skills (Gathercole and Baddeley, 1996). The strong intercorrelations between these different tasks has not, however, been previously reported for this clinical population.

The correlations between nonword repetition and speaking rate measured independently from sentence durations provide some additional insights into the source of the individual differences. The results reflect factors related to the speed and efficiency of phonological processing, specifically the verbal rehearsal process. Our finding that children with faster speaking rates also tended to have higher nonword repetition scores is consistent with the view that speaking rate reflects the speed with which phonological information can be subvocally rehearsed in short-term working memory (see Landauer, 1962; Baddeley, 1986; Pisoni and Cleary, in press; Burkholder and Pisoni, in press). The present findings indicate that individual differences in verbal rehearsal rate as indexed by sentence duration are associated with nonword repetition performance.

The correlations between the children’s nonword repetition performance and all of the speech and language outcome and process measures suggests that the nonword repetition task could serve as a composite diagnostic measure of the children’s ability to access and integrate these component skills in performing this repetition task. The strong correlations between nonword repetition performance and scores on the other speech and language measures indicate that the children who performed well on separate measures of the component processes also performed well on a processing task that combined these skills together.

We found that the demographic characteristics of the children did not influence their ability to correctly imitate consonants in nonwords. It is possible that the homogeneity of the children in terms of demographics may be responsible for the weak correlations between the demographics and the consonant accuracy scores. In the present study, 18 children used oral communication while only six used total communication methods. In another study of 76 children who completed the nonword repetition task that included the 24 children discussed in the present paper, we found that perceptual ratings of the nonword repetition responses were strongly correlated with the children’s communication mode scores (Dillon, Burkholder, Cleary and Pisoni, in press). Children who had been exposed to primarily oral methods of communication tended to perform better on the nonword repetition task than the children who primarily used total communication methods.

Taken together, the results of this study demonstrate that the nonword repetition task can provide fundamental new insights about the speech and language skills and underlying phonological processing abilities of pediatric cochlear implant users. With further analytic studies of this type, we hope to better understand the relations between auditory, cognitive, and linguistic processes used in the perception and production of spoken language, and how these develop and change in deaf children over time following cochlear implantation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH NIDCD Research Grant DC00111 and NIH NIDCD Training Grant DC00012 to Indiana University. We would like to thank Dr Ann Geers, Dr Rosalie Uchanski and the research team at the Center for Applied Research on Childhood Deafness, Central Institute for the Deaf, St. Louis, MO 63110 for their invaluable help in this project. We would also like to acknowledge the efforts of Dr Emily Tobey and the investigative team at the University of Texas at Dallas Callier Advanced Hearing Research Center for the measures of speech intelligibility and overall sentence durations. We are also grateful to Rose Burkholder, Cynthia Clopper and Jeffrey Reynolds for their help in the completion of this study.

References

- Avons SE, Wragg CA, Cupples L, Lovegrove WJ. Measures of phonological short-term memory and their relationship to vocabulary development. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1998;19:583–601. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A. Working Memory. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bench J, Kowal A, Bamford J. The BKB (Bamford-Kowal-Bench) sentence lists for partially-hearing children. British Journal of Audiology. 1979;13:108–112. doi: 10.3109/03005367909078884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blamey PJ, Sarant JZ, Paatsch LE, Barry JG, Bow CP, Wales RJ, Wright M, Psarros C, Rattigan K, Tooher R. Relationships among speech perception, production, language, hearing loss, and age in children with impaired hearing. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001;44:264–285. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothroyd A. Vidspac 2.0: A video game for assessing speech pattern contrast perception in children. San Diego, CA: Arthur Boothroyd; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder RA, Pisoni DB. Speech timing measures and working memory in profoundly deaf children after cochlear implantation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2003;85:63–88. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0965(03)00033-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson JL, Cleary M, Pisoni DB. Research on Spoken Language Processing Progress Report No 22. Bloomington, IN: Speech Research Laboratory, Indiana University; 1998. Performance of normal-hearing children on a new working memory span task; pp. 251–273. [Google Scholar]

- Carrow-Woolfolk E. Test for Auditory Comprehension of Language-Revised (TACL-R) Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Carter AK, Dillon CM, Pisoni DB. Imitation of nonwords by hearing-impaired children with cochlear implants: suprasegmental analyses. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics. 2002;16:619–638. doi: 10.1080/02699200021000034958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary M, Dillon CM, Pisoni DB. Imitation of nonwords by deaf children following cochlear implantation. Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology, Supplement-Proceedings of the 8th Symposium on Cochlear Implants in Children. 2002;111:91–96. doi: 10.1177/00034894021110s519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N, Saults JS, Elliot EM, Moreno MV. Deconfounding serial recall. Journal of Memory and Language. 2002;46:153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson PW, Blamey SJ, Dettman SJ, Rowland LC, Barker EJ, Tobey EA, Busby PA, Cowan RC, Clark GM. A clinical report on speech production of cochlear implant users. Ear and Hearing. 1995;16:551–561. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199512000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon CM, Burkholder RA, Cleary M, Pisoni DB. Perceptual ratings of nonword repetitions by deaf children after cochlear implantation: correlations with measures of speech, language and working memory. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research in press. [Google Scholar]

- Dowell RC, Blamey PJ, Clark GM. Potential and limitations of cochlear implants in children. Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology. 1995;166 (Suppl):324–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Lahey M. Nonword repetitions of children with specific language impairment: exploration of some explanations for their inaccuracies. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1998;19:279–309. [Google Scholar]

- Engle RW. Working memory capacity as executive attention. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002;11:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE. Is non-word repetition a test of phonological memory or long-term knowledge? It all depends on the non-words. Memory and Cognition. 1995;23:83–94. doi: 10.3758/bf03210559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Adams A. Phonological working memory in very young children. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Baddeley AD. The role of phonological memory in vocabulary acquisition: a study of young children learning new names. British Journal of Psychology. 1990;81:439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Baddeley AD. Working Memory and Language. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Baddeley AD. The Children’s Test of Non-word Repetition. London: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole SE, Willis CS, Baddeley AD, Emslie H. The Children’s Test of Non-word Repetition: a test of phonological working memory. Memory. 1994;2:103–127. doi: 10.1080/09658219408258940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers A, Brenner C. Background and educational characteristics of prelingually deaf children implanted by 5 years of age. Ear and Hearing. 2003;24:2S–14S. doi: 10.1097/01.AUD.0000051685.19171.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudgins CV, Numbers FC. An investigation of the intelligibility of the speech of the deaf. Genetic Psychology Monographs. 1942;25:289–392. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk KI. Challenges in the clinical investigation of cochlear implant outcomes. In: Niparko JK, Kirk KI, Mellon NK, Robbins AM, Tucci BL, Wilson BS, editors. Cochlear Implants: Principles and Practices. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2000. pp. 225–259. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk KI, Pisoni DB, Osberger MJ. Lexical effects on spoken word recognition by pediatric cochlear implant users. Ear and Hearing. 1995;16:470–481. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199510000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs L, Pisoni DB, Kirk KI. Use of audiovisual information in speech perception by prelingually deaf children with cochlear implants: a first report. Ear and Hearing. 2001;22:236–251. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200106000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landauer TK. Rate of implicit speech. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1962;15:646. doi: 10.2466/pms.1962.15.3.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Li SC, Lewandowsky S. Forward and backward recall: different retrieval processes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1995;21:837–847. [Google Scholar]

- McGarr NS. The intelligibility of deaf speech to experienced and inexperienced listeners. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1983;26:451–458. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2603.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto RT, Osberger MJ, Todd SL, Robbins AM, Stroer BS, Zimmerman-Phillips S, Carney AE. Variables affecting implant performance in children. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1120–1124. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199409000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osberger MJ, Robbins AM, Berry SW, Todd SL, Hesketh LJ, Sedey A. Analysis of the spontaneous speech samples of children with cochlear implants or tactile aids. The American Journal of Otology. 1991;12 (Suppl):151–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papagno C, Valentine T, Baddeley A. Phonological short-term memory and foreign-language vocabulary learning. Journal of Memory and Language. 1991;30:331–347. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB. Cognitive factors and cochlear implants: Some thoughts on perception, learning, and memory in speech perception. Ear and Hearing. 2000;21:70–78. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200002000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB, Cleary M. Learning, memory and cognitive processes in deaf children following cochlear implantation. In: Zeng FG, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research: Auditory Prostheses, SHAR. X. Berlin: Springer; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB, Geers AE. Working memory in deaf children with cochlear implants: correlations between digit-span and measures of spoken language processing. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology Supplement. 2000;185:92–93. doi: 10.1177/0003489400109s1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen VM, Engle RW. Forward and backward serial recall. Intelligence. 1997;25:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ross M, Lerman J. A picture identification test for hearing-impaired children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1979;13:44–53. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1301.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarant JZ, Blamey PJ, Dowell RC, Clark GM, Gibson WPR. Variation in speech perception scores among children with cochlear implants. Ear and Hearing. 2001;22:18–28. doi: 10.1097/00003446-200102000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal ST, Kirk KI, Svirsky MA, Ertmer DJ, Osberger MJ. Imitative consonant feature production by children with multichannel sensory aids. Ear and Hearing. 1998;19:72–84. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199802000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slobin DI, Welsh CA. Elicited imitation as a research tool in developmental psycholinguistics. In: Ferguson CA, Slobin DI, editors. Studies in Child Language Development. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1973. pp. 485–497. [Google Scholar]

- Tobey E, Geers A, Brenner C. Speech production results: speech feature acquisition. The Volta Review. 1994;96:109–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tobey E, Geers A, Douek B, Perrin J, Skellett R, Brenner C, Torretta G. Factors associated with speech intelligibility in children with cochlear implants. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology, Supplement. 2000;185:28–30. doi: 10.1177/0003489400109s1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – III. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]