Abstract

DNA binding as well as ligand binding by nuclear receptors has been studied extensively. Both binding functions are attributed to isolated domains of which the structure is known. The crystal structure of a complete receptor in complex with its ligand and DNA-response element, however, has been solved only for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)-retinoid X receptor α (RXRα) heterodimer. This structure provided the first indication of direct interactions between the DNA-binding domain (DBD) and ligand-binding domain (LBD). In this study, we investigated whether there is a similar interface between the DNA- and ligand-binding domains for the androgen receptor (AR). Despite the structural differences between the AR- and PPARγ-LBD, a combination of in silico modeling and docking pointed out a putative interface between AR-DBD and AR-LBD. The surfaces were subjected to a point mutation analysis, which was inspired by known AR mutations described in androgen insensitivity syndromes and prostate cancer. Surprisingly, AR-LBD mutations D695N, R710A, F754S, and P766A induced a decrease in DNA binding but left ligand binding unaffected, while the DBD-residing mutations K590A, K592A, and E621A lowered the ligand-binding but not the DNA-binding affinity. We therefore propose that these residues are involved in allosteric communications between the AR-DBD and AR-LBD.

INTRODUCTION

Nuclear receptors (NRs) are involved in many physiological processes, diseases, and therapeutic applications. They are transcription factors that contain a DNA-binding domain (DBD) composed of 2 zinc fingers (40) and a ligand-binding domain (LBD) formed by 12 α helices (60). The structures of the separate DNA-binding and ligand-binding domains of many receptors have already revealed a large amount of information. The structure of the LBD has especially led to a more focused search for new agonists and antagonists for many therapeutic indications where NRs are involved. The exact structure of full-size NRs bound to DNA and ligand will help us in understanding the basic mechanism of nuclear receptor signaling but will also provide new targets for therapeutic strategies. The coordinates of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)-retinoid X receptor α (RXRα) cocrystal bound as a heterodimer to the DNA have been reported (11) and revealed a contact between PPARγ and RXRα more intimate than expected. The existence of the previously unknown interface between PPARγ-LBD and RXRα-DBD was corroborated with a mutation analysis. Since this has not yet been confirmed by other techniques like small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) (49), it is debated whether such a communication exists. There is, however, strong evidence for allosteric communications, e.g., between the DBD and LBD, in nuclear receptors. A most remarkable observation was made for the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) when slightly different response elements were tested in gene reporter assays: small changes in the DNA sequence had an important impact on receptor activity (44, 58). Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching experiments with green fluorescent protein-tagged NRs shows that binding of a ligand affects the receptor mobility in the nucleus, indicating an influence of the LBD on DNA binding (24, 43). By means of isothermal titration calorimetry, the thyroid receptor was demonstrated to display DNA-dependent DBD-LBD interactions that were bidirectional. TRE binding by the DBD appears to decrease its affinity for the LBD and thereby facilitates recruitment of SRC-1 to the LBD (47). Moreover, for the vitamin D receptor (VDR)-RXR heterodimer, hydrogen-deuterium-exchange studies provided structural evidence for DNA-dependent allosteric communication between DBD and LBD of one receptor and between the binding partners (62). Also for the androgen receptor (AR), it was demonstrated that some receptor mutations outside the DBD affect the activity of the receptor in a DNA sequence-dependent way (8, 9).

The AR is an NR involved in the early development of the male sexual organs and in the establishment and maintenance of the secondary male characteristics and fertility in puberty and in adult life. The AR is activated by testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and regulates the expression of androgen-responsive genes by binding to a nearby regulatory sequence in the DNA, also known as the androgen-response element (ARE). In addition, the AR is an important survival factor in primary as well as castration-resistant forms of prostate cancer (PrCa) (2).

Despite considerable differences in primary amino acid sequences, the structure of the AR-DBD and AR-LBD closely resembles that of other NRs. The DBD is the most conserved NR domain and consists of two α helices that are coordinated by zinc molecules, thus forming two zinc-finger modules. The first zinc finger is responsible for the recognition of AREs, while the second zinc finger is involved in DNA-dependent dimerization (31, 40, 51).

The LBD is the second most conserved domain and consists of 11 α helices that form a ligand-binding pocket which is delineated by helices 3, 4, 5, 7, 11, and 12 and the β sheet preceding helix 6 (42). The carboxy-terminal helix, named helix 12, functions as an intramolecular switch (52). Binding of an agonist results in the repositioning of helix 12 and creates a hydrophobic groove formed by helices 3, 4, 5, and 12. This site serves as a binding site for LXXLL-containing coactivators as well as for the amino-terminal domain of the AR (30, 38, 56).

Regarding the AR, dimerization occurs primarily at the level of the DBD via the so-called D-box residues in the second zinc finger (51) as well as between the amino-terminal domain (NTD) and the LBD (21, 30). The latter interaction takes place between the conserved 23FQNLF27 motif and the ligand-induced hydrophobic groove at the surface of the LBD (29). The extent to which the N/C interaction is impaired by mutating residues in the AR-LBD seems to correlate with the severity of the corresponding androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) phenotype (26, 36). However, the exact role of the N/C interaction in transcription control still remains obscure since it is largely lost once the receptor binds to the DNA (50, 57).

Dimerization via the LBD has been described for many receptor homodimers, such as GR, progesterone receptor (PR), estrogen receptor, and RXR, as well as for heterodimeric receptor complexes, such as PPAR and RXR (4, 6, 11, 55), but the existence of such an LBD dimerization surface for the AR homodimer remains controversial (45). Furthermore, it is unknown whether the DBD-LBD interactions described for the PPARγ-RXRα heterodimer can occur within or between AR monomers. To investigate this, we have taken advantage of the many AR mutations that have been described to correlate with pathologies. Indeed, AR mutations described in patients suffering from AIS can provide valuable information on the importance of the mutated residues in AR functioning.

In the study described in this report, we investigated the existence of a DBD-LBD interface in the AR homodimer. By means of in silico approaches, potential interaction surfaces between DBD and LBD were predicted and analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs.

The cDNA of the human AR was present in a Flag-tagged pSG5 expression vector. Mutations in the LBD of the AR were introduced by two-step PCR site-directed mutagenesis using two internal primers and two external primers. The resulting mutated human AR-LBD cDNA fragments were recloned as PsyI/AsuII fragments into the pSG5–Flag–wild-type (wt) AR construct. Mutations in the DBD were made by site-directed mutagenesis of the wild-type AR-DBD-encoding cDNA fragment inserted in pGEM-T Easy (Promega) using two primers containing the mutation, enabling amplification of the complete vector. The mutated AR-DBD cDNA was subsequently cloned as a HindIII/PsyI fragment into the pSG5-Flag-wt AR construct. The pCMV–β-gal expression vector was obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The classical ARE-based luciferase reporter plasmid was described before (19).

Cell culture, transfections, and nuclear extracts.

COS-7 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. For assessing the transactivation capacity of the mutant ARs, cells were seeded at a density of 10,000 cells/well in a 96-well plate. In each well, 10 ng expression vector of the receptor, 100 ng of reporter plasmid, and 10 ng of the pCMV–β-gal expression vector were transfected. The next day, the medium in the wells was replaced by medium containing DHT (Sigma-Aldrich) or R1881 (Perkin Elmer). Cells were harvested in passive lysis buffer (Promega), and luciferase activity and β-galactosidase activity were measured as described before (27).

Nuclear extracts of COS-7 cells expressing wild-type or mutant ARs were prepared as described earlier (19).

EMSAs.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed using nuclear extracts of COS-7 cells expressing wild-type AR or a mutant AR. The binding of these receptors to [α-32P]dCTP-labeled ARE sequences was determined as described earlier. TAT-GRE with the sequence 5′-AGAACAtccTGTACA-3′ and SLP-MUT (SLP-HRE2 mutated [position −4, T to A]) with the sequence 5′-AGAACTgccTGTCCA-3′ (where lowercase nucleotides indicate the 3-nucleotide spacer) were used as AREs (19).

Whole-cell competition assay (WCCA).

COS-7 cells were seeded in a 48-well plate at a density of 30,000 cells per well. The next day, the cells were transfected with 375 ng expression vector for either wild-type or a mutant AR and 75 ng of pCMV–β-gal expression vector (per well). After approximately 48 h, the cells were incubated with 3H-labeled mibolerone ([3H]Mib; 72.2 Ci/mmol) to investigate the binding capacity in the transfected cells. Both total binding and aspecific binding were determined, from which the specific binding of 3H-labeled mibolerone to the receptor was derived. A dilution series of [3H]Mib (300, 100, 30, 10, 3, 1, and 0.3 nM [3H]Mib) was made to assess total binding. An excess of DHT (10 μM) was added to the dilution series to determine aspecific binding of the cells. After incubating the cells for 90 min at 37°C, the cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in 100 μl of passive lysis buffer (Promega). To 75 μl cell lysate, 2 ml Lumasafe Plus scintillation cocktail (Perkin Elmer) was added, and the radioactivity (as counts per minute) was detected in a Wallac 1409 liquid scintillation counter from Perkin Elmer. Receptor expression was compared by Western blot analysis, and protein concentrations were used to convert counts per minute into fmol/μg protein. Via nonlinear regression analyses in GraphPad Prism (version 5) software (GraphPad Software), the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) and the maximal ligand-binding capacity (Bmax) were calculated from at least two independent experiments. The Bmax of AR wt was set at 100%, and the Bmax of every other receptor is given relative to the Bmax of AR wt. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5) software.

In silico three-dimensional (3D) alignment and docking analysis.

Using the coordinates from the model of the PPARγ-RXRα heterodimer (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession number 3DZY), the rat AR-DBD (PDB accession number 1R4I) was aligned onto the RXRα-DBD and the human AR-LBD (PDB accession number 1XQ3) was aligned onto the PPARγ-LBD using the CEAlign tool in the PyMOL program (17).

The crystal structures of human AR-LBD (PDB accession number 2AM9) and rat AR-DBD (PDB accession number 1R4I) were used to perform protein-protein docking with the HADDOCK (version 2.0) program (20). Since at the moment of the docking experiments mutagenesis data on the contact between AR-LBD and AR-DBD were still absent, we chose not to define ambiguous interaction restraints since they might bias the docking results. Two patches on the surface of AR-LBD were used as semiflexible segments in two individual docking experiments. During the first docking, residues 720 to 730, 732 to 733, 737, 741 to 746, 767, 830 to 831, and 834 (patch 1) were indicated to be semiflexible, while in the second experiment, residues 681 to 684, 686 to 688, 710 to 712, 748 to 752, 754 to 759, and 762 to 768 (patch 2) formed the semiflexible segments. For AR-DBD, we defined the residues opposite the DNA-binding surface to be semiflexible segments in both experiments. These included residues 569 to 584, 596 to 597, 599 to 600, and 602 to 611 (586 to 601, 613 to 614, 616 to 617, and 619 to 628 in human). In a first step, 1,000 structures were generated using randomization and rigid body energy minimization, followed by semiflexible simulated annealing in torsion-angle space on the best 200 structures and final refinement in an explicit solvent layer (8-Å radius) containing water molecules. The structures were sorted according to a weighted sum (HADDOCK score) of, among other factors, buried surface area, van der Waals force, and electrostatic energy. The solutions were, for both experiments, divided into 13 clusters (16) containing at least 5 complexes with an interface backbone root mean square deviation of 5 Å, from which the best-scoring one was further analyzed. For these structures, the total nonbonded energy and total interface area were calculated using the Brugel package (18).

RESULTS

3D alignment of AR on PPAR-RXR crystal structure.

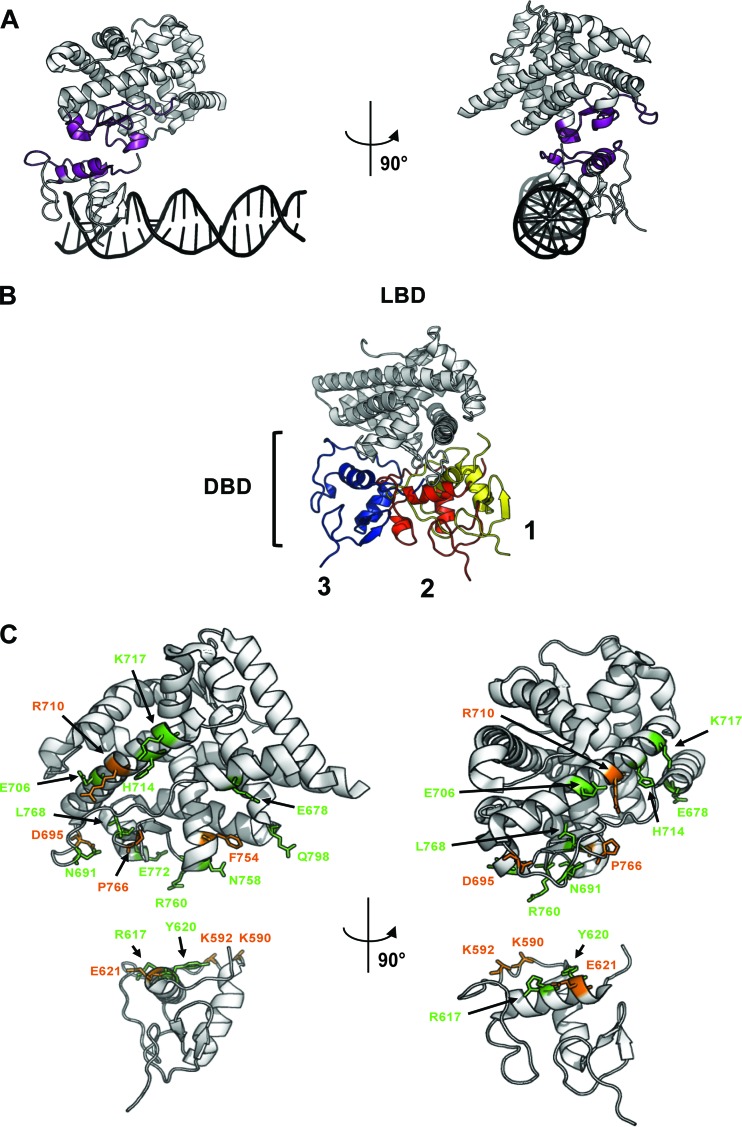

To test the hypothesis of DBD-LBD communications in the AR, we based our first AR DBD-LBD model on the crystal structure of PPARγ-RXRα (PDB accession number 3DZY) (11). Via CEAlign, a plug-in for Pymol (17), the main-chain coordinates of the AR-LBD were fitted onto those of the PPARγ-LBD and the coordinates of the AR-DBD were fitted onto those of the RXRα-DBD (Fig. 1A). The position of the LBD in relation to the DBD in the 3D alignment of the AR has to be interpreted with caution since the PPARγ-RXRα heterodimer was bound to a direct repeat with a 1-nucleotide spacer (DR1), while the AR homodimer binds to response elements with a 3-nucleotide spacer. Spacing influences the position of the DBDs on the DNA helix and perhaps also the positioning of the LBDs toward each other. Second, the structural elements involved in the interaction surface on the PPAR-LBD are not well conserved in the AR. In the PPARγ-RXRα heterodimer, the residues in helix 5 are not situated on the surface due to the presence of helix 2a, an additional β strand, and helix 2b. In the AR, this region corresponds to a linker with little secondary structure, resulting in a gap between the AR-LBD and the AR-DBD in the model. However, in this alignment model, a first potential interaction surface on the DBD is formed by residues 587 to 599, 612 to 614, and 617 to 626, which interact with the regions 682 to 695 and 754 to 774 in the LBD (Fig. 1A). To test the functional relevance of this hypothetical LBD-DBD contact, these regions were subjected to mutational analysis. Target residue selection was based on data in the Androgen Receptor Gene Mutation Database on AR mutations in AIS patients and PrCa biopsy specimens (39).

Fig 1.

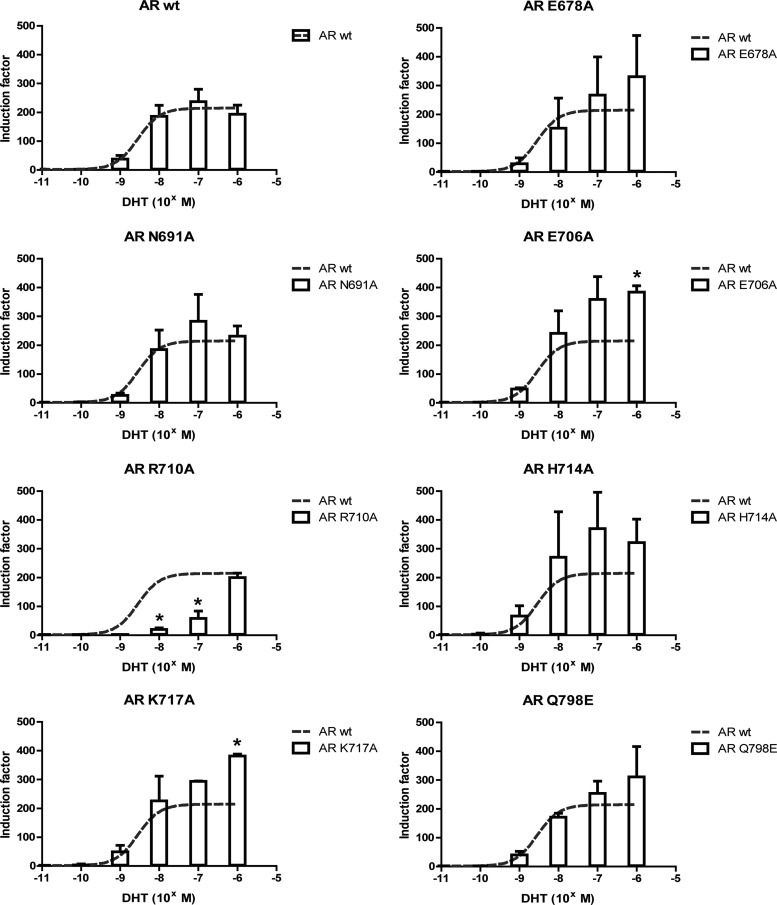

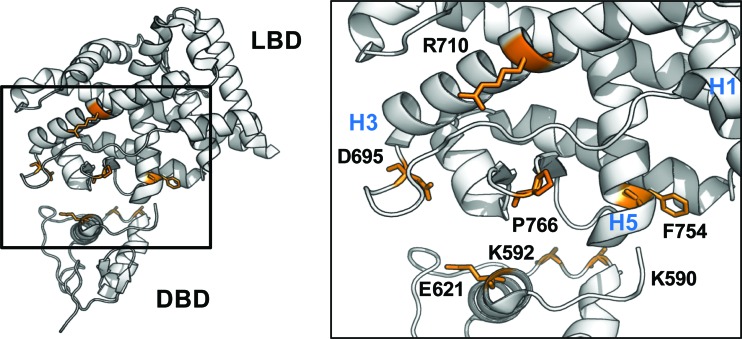

In silico models applied to investigate DBD-LBD communication and position of mutated residues. (A) Front and side views of the 3D alignment of AR-DBD (PDB accession number 1R4I) and AR-LBD (PDB accession number 1XQ3) onto the heterodimeric complex of PPARγ-RXRα (PDB accession number 3DZY). The interaction surfaces on the AR-DBD and AR-LBD are depicted in purple. The DNA helix is shown in black. (B) Docking of AR-DBD (PDB accession number 1R4I) onto AR-LBD (PDB accession number 2AM9). Three potential positions of the AR-DBD (yellow, red, and blue) are given in respect to the AR-LBD (white). Each position corresponds to a cluster and represents an energy-favorable DBD-LBD position. (C) Front and side views of the positions of the residues in LBD and DBD that have been tested for their role in DBD-LBD communication in the AR. They are K590, K592, R617, Y620, and E621 in the DBD and E678, N691, D695, E706, R710, H714, K717, F754, N758, R760, P766, L768, E772, and Q798 in the LBD. Residues that affect the function of the adjacent domain are indicated in orange; other residues are in green.

Effect of alignment-based mutations on transactivation.

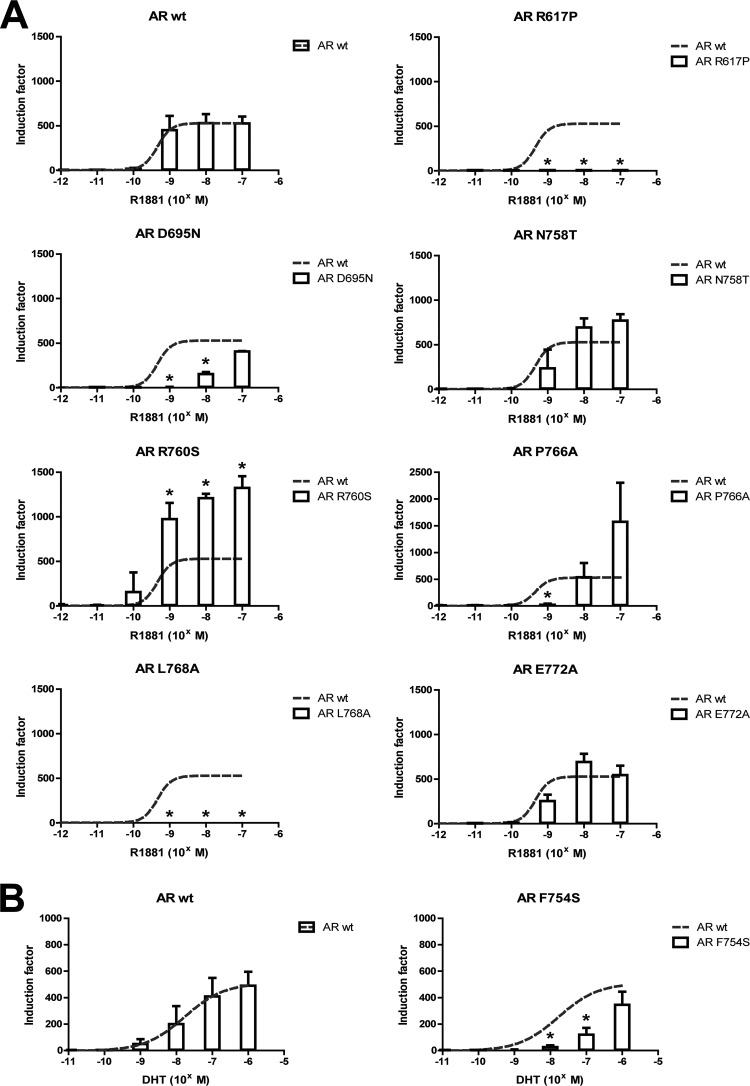

The transactivation capacity of the mutant receptors mentioned in Table 1 were assessed and compared to that of the wild-type AR (Fig. 2). Two mutant ARs (AR R617P and AR L768A) did not show any activity in transfection assays, even at higher agonist levels. Three mutations (D695N, F754S, and P766A) reduced transactivation at physiological ligand concentrations, but at higher levels, their transactivation capacity was comparable to that of wild-type AR. Two other mutations (N758T and E772A) did not significantly affect transactivation at low ligand concentrations, while AR R760S showed a surprising increase in transactivation capacity at R1881 concentrations of 1 nM or higher.

Table 1.

Overview of location in the AR, results obtained on transactivation, DNA binding, and ligand binding, and occurrence in AIS and PrCa for selected mutations

| Domain and position | Mutation | Transactivation | DNA binding | Ligand binding | Phenotype | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DBD | ||||||

| Lever arm | K590A | ↓ | Normal | KD↑,a Bmax↓ | ||

| K592A | ↓ | Normal | KD↑,a Bmax↑ | |||

| 2nd α helix | R617P | Inactive | Inactive | Normal | PAIS, CAIS | 41, 63 |

| Y620A | Normal | Normal | Bmax↓ | |||

| E621A | ↓ | Normal | Bmax↓ | |||

| LBD | ||||||

| Helix 1 | E678A | Normal | ||||

| Helix 2 | N691A | Normal | ||||

| D695N | ↓ | ↓ | Normal | MAIS, PAIS, CAIS | 1, 12, 25, 28, 34, 48 | |

| Helix 3 | E706A | ↑ at high concn | ||||

| R710A | ↓ at low concn | ↓ | Normal | |||

| H714A | Normal | |||||

| K717A | ↑ at high concn | |||||

| End of helix 5 | F754S | ↓ | ↓ | Normal | PAIS | 54 |

| N758T | Normal | ↓ | Normal | PAIS | 61 | |

| R760S | ↑ | PAIS | 37 | |||

| β turn | P766A | ↓ at low concn | ↓ | Normal | CAIS | 5 |

| L768A | Inactive | ↓ | Inactive | |||

| E772A | Normal | PAIS | 53 | |||

| End of helix 7 | Q798E | Normal | MAIS, PAIS, PrCa | 3, 10, 23, 25, 32, 33, 35, 59 |

A 2-fold increase compared to AR wt, which was not significant.

Fig 2.

The transactivation of AR is affected by mutation of residues selected from the 3D alignment. The transactivation capacity of the mutant ARs was investigated by transient transfection in COS-7 cells. The ability of the mutant receptors to initiate transcription of an androgen-regulated luciferase reporter gene was compared to the activity of AR wt. R1881 or DHT was added over a concentration gradient ranging from 1 pM to 10 μM. Activities that are significantly different compared to the activity of AR wt are indicated (*, P < 0.05; Student's t test). The mean and standard deviation of at least 3 independent experiments are given. (A) AR wt, AR R617P, AR D695N, AR N758T, AR R760S, AR P766A, AR L768A, and AR E772A; (B) AR wt and AR F754S.

Docking of AR-DBD onto AR-LBD.

In an in silico docking experiment, the most-energy-favorable position of AR-DBD and AR-LBD in relation to each other was calculated with HADDOCK (version 2.0) (20). For the in silico docking of the AR-DBD onto the AR-LBD, we selected the DBD surface opposite of the DNA-binding surface, and for the LBD we focused on two mutational hot spots. The hot spots on the LBD were named patch 1 and patch 2 and are defined in Materials and Methods. Because the docking experiment resulted in lower-scoring complexes when patch 1 was used as a semiflexible segment than when patch 2 was used, we selected three clusters generated by docking with patch 2. For each of these clusters, the most-energy-favorable structure was chosen as a representative. Each of these DBD-LBD positions provided us with a well-defined hypothetical interface and the contribution of specific residues to the interaction (Fig. 1B; see Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). Residues that contributed the most to the stabilization of the interaction by lowering the nonbonded interaction energy were mutated. When possible, mutations described to occur in AIS or PrCa were introduced. If not indicated otherwise, the residues were changed to alanine.

Effect of docking-based mutations on transactivation.

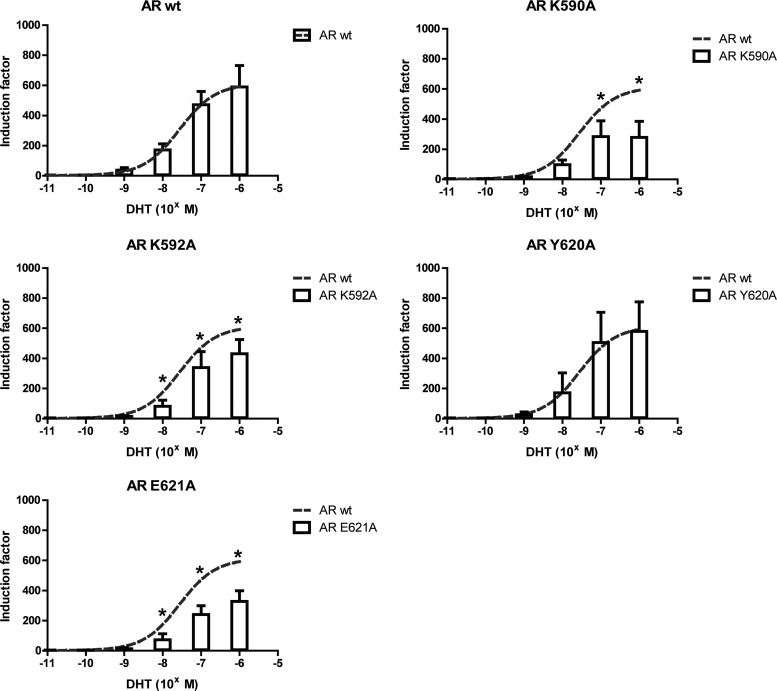

Four DBD mutations (K590A, K592A, Y620A, and E621A) were tested for their effect on the transcriptional activity of the AR. K590A, K592A, and E621A slightly but significantly reduced transactivation of the receptor, while Y620A had no apparent effect (Fig. 3). Of the seven LBD mutations (E678A, N691A, E706A, R710A, H714A, K717A, and Q798E), only AR R710A showed a clear reduction in activity compared to AR wt at low but not at higher ligand concentrations (Fig. 4). No significant difference with AR wt was seen for AR E678A, AR N691A, AR H714A, and AR Q798E. Surprisingly, two mutations (E706A and K717A) increased the potency of the AR significantly at higher ligand concentrations.

Fig 3.

The transactivation of AR is affected by mutation of residues in the DBD selected from the docking. The transactivation capacity of the mutant AR (indicated at the top of each panel) was investigated by transient transfection in COS-7 cells. The ability of the mutant receptors to initiate transcription of an androgen-regulated luciferase reporter gene was compared to the activity of AR wt. DHT was added over a concentration gradient ranging from 0.1 pM to 1 μM. Activities that are significantly different from the activity of AR wt are indicated (*, P < 0.05; Student's t test). The mean and standard deviation of at least 3 independent experiments are given.

Fig 4.

The transactivation of AR is affected by mutation of residues in the LBD selected from the docking. The transactivation capacity of wild-type and mutant ARs was investigated by transient transfection in COS-7 cells. The ability of the mutant receptors to initiate transcription of an androgen-regulated luciferase reporter gene was compared to the activity of AR wt. DHT was added over a concentration gradient ranging from 0.1 pM to 1 μM. Activities that are significantly different from the activity of AR wt are indicated (*, P < 0.05; Student's t test). The mean and standard deviation of at least 3 independent experiments are given.

DNA- and ligand-binding capacities of AR mutants.

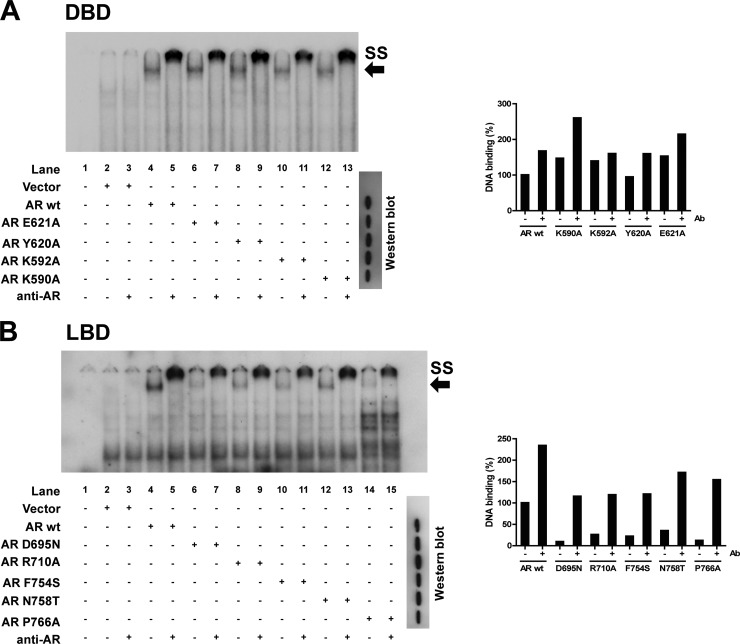

Mutated receptors with reduced transactivation capacity or lower ligand sensitivity were subjected to EMSA and WCCA to assess their ligand- and DNA-binding capacity. DNA binding determined with EMSA was not affected by the DBD mutations K590A, K592A, Y620A, and E621A (Fig. 5A). For several LBD mutants, namely, AR D695N, AR R710A, AR F754S, AR N758T, and AR P766A, the DNA binding was impaired compared to that for AR wt (Fig. 5B). Importantly, the mutations did not affect the expression level of the receptor, as shown by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

DNA-binding ability of mutant ARs. By means of EMSA, the DNA-binding capacities of several DBD mutants (A) and several LBD mutants (B) were investigated. Radioactively labeled TAT-GRE and SLP-MUT AREs were used for the DBD mutants and LBD mutants, respectively. Binding of the receptor to the ARE gives a complex at the position of the arrow. Addition of an AR antibody causes a supershift, indicated by SS. Loading of equal amounts of receptor was confirmed by Western blot analysis. The free probe, which is present at the bottom of the gel, is not included in this picture. The DNA-binding capacity and the expression level of each mutant receptor were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH), resulting in a relative DNA-binding capacity given as a percentage of the binding of AR wt.

In return, the affinity for ligand of the DBD mutants AR K590A and AR K592A was reduced (Table 2). Their KDs for mibolerone were 3.57 nM and 3.83 nM, respectively, which is a 2-fold increase compared to the KD of AR wt (1.69 nM). This increase was, however, not significant. The DBD mutants also display aberrant maximal ligand-binding capacities (Bmaxs) of 74.5%, 158.1%, 46.3%, and 60.8% for AR K590A, AR K592A, AR Y620A, and AR E621A, respectively. These are all significantly different compared to the Bmax of AR wt (105.1%) (Table 2). Clearly, some of the LBD mutations (D695N, R710A, F754S, N758T, and P766A) did not affect the ligand-binding capacity since KD and Bmax were in the normal range (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ligand-binding ability of mutant ARs

| Domain and AR mutant | KD (nM) | SE of KD | Bmax (% fmol/μg of AR wt) | SE of Bmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR wt | 1.69 | 0.63 | 105.1 | 8.3 |

| DBD | ||||

| AR K590A | 3.57 | 1.00 | 74.5a | 5.0 |

| AR K592A | 3.83 | 1.31 | 158.1a | 13.1 |

| AR Y620A | 1.83 | 0.39 | 46.3a | 2.2 |

| AR E621A | 2.33 | 2.06 | 60.8a | 12.0 |

| LBD | ||||

| AR D695N | 2.43 | 0.49 | 96.3 | 4.4 |

| AR R710A | 2.73 | 0.48 | 97.1 | 3.9 |

| AR F754S | 2.11 | 0.61 | 109.9 | 7.0 |

| AR N758T | 2.15 | 0.49 | 89.8 | 4.6 |

| AR P766A | 2.83 | 0.83 | 119.6 | 8.1 |

Significant difference compared to AR wt (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA).

The DBD mutant AR R617P was transcriptionally inactive due to abrogated DNA binding (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), while the LBD mutant AR L768A was inactive due to its inability to bind ligand (data not shown). All data on transactivation or DNA and ligand binding of the mutated ARs and the correlated patient phenotypes (when available) are summarized in Table 1; the positions of the mutated residues in the molecular model of the AR are indicated in Fig. 1C.

DISCUSSION

A lot of experimental data hint toward allosteric interferences between the LBD and DBD of NRs (7–9, 24, 43, 44, 47), but only the report by Chandra et al. in 2008 (11) has provided strong evidence for a physical interaction between the DBD and LBD of the PPARγ-RXRα heterodimer. In this study, we aimed to identify residues at the surface of the AR-DBD and AR-LBD that might be involved in such DBD-LBD communications. Candidate residues were identified with the help of in silico models and information from the Androgen Receptor Gene Mutation Database (39). Both the 3D alignment of AR with the PPARγ-RXRα coordinates and the AR docking provided potential interaction surfaces for the AR. The functional relevance of the predicted interfaces was scrutinized by mutational analysis. The strength of this study of the AR is that some of these mutations have already been described in AIS and/or PrCa, and these findings provide direct indications of the in vivo relevance of the mutated residues.

Superposition of the AR on the PPARγ-RXRα crystal coordinates resulted in the selection of one DBD mutation and seven LBD mutations found in mild AIS (MAIS), partial AIS (PAIS), and/or complete AIS (CAIS) that are present in the thus defined DBD-LBD interface. A further four DBD and seven LBD residues were selected from the surfaces generated by AR docking (summarized in Table 1).

Mutational analysis of DBD and LBD surfaces.

Two mutations (R617P and L768A) affected the primary function of the receptor domain that they are situated in (DBD and LBD, respectively), thus explaining their inactivating effect on the receptor's function in the transactivation assay. A possible implication of these residues in DBD-LBD communications can therefore not be commented on.

Conversely, many of the tested mutations left the receptor unaffected (Y620A, E678A, N691A, H714A, and Q798E) or even increased its ability to transactivate (E706A, K717A, and R760S). For R760S, E772A, and Q798E, the absence of any effect in our assays is in surprising contradiction with the AIS phenotypes of the patients in which they were described (3, 37, 53). In particular, Q798E was expected to have functional implications because mutations of this residue have been found in a number of AIS as well as PrCa cases. However, its mutation did not affect AR activity in our transactivation assays. These data are in accordance with those of Bevan et al., who reported normal ligand-binding capacity for this mutant (3). This still leaves the molecular effects of these AIS and PrCa mutations unexplained.

Evidence for DBD-LBD communications in AR.

Four mutations in the AR-LBD (D695N, R710A, F754S, and P766A) do not affect ligand binding but reduce DNA binding and transactivation. Three mutations in the AR-DBD (K590A, K592A, and E621A) do not affect DNA binding but reduce ligand binding and transactivation of the AR. We propose that these mutations affect direct communications between the DBD and the LBD.

A surface on the LBD affects DNA binding.

The four LBD mutations are located at the surface of the LBD (Fig. 6). This surface consists of residues located in the linker corresponding to helix 2 (D695), in helix 3 (R710), in helix 5 (F754), and in the β turn (P766). The functional importance of these four residues in AR functioning is underlined by their involvement in several cases of AIS (Table 1). Moreover, two of the residues (D695 and P766) are conserved in PR, mineralocorticoid receptor, and GR and because of their surface exposures in the LBD crystal structures might be involved in DBD-LBD communications.

Fig 6.

Proposed position of the DBD relative to the LBD. The positions of DBD and LBD were derived from the 3D alignment of the AR on the PPARγ-RXRα model. The residues that were shown to be involved in DBD-LBD communication are depicted in orange. Helices 1, 3, and 5 are indicated (H1, H3, and H5).

A surface on the DBD affects ligand binding.

Three mutations that affect AR ligand binding are located at the surface of the DBD (K590A, K592A, and E621A) (Fig. 6), again strongly suggesting DBD-LBD communications. Residues K590 and K592 are located in the linker region between the two zinc fingers, which corresponds to the lever arm in the GR. For the GR, the conformation of this lever arm is influenced by the sequence of the DNA response element. Since the activity of the GR depends greatly on the DNA sequence it is binding to, it was suggested that the lever arm transmits this DNA signal allosterically to other domains of the receptor (44). Our results are in agreement with the possibility of a similar allosteric influence of the lever arm on other domains of the AR.

In summary, we identified seven residues that are implicated in interdomain communications between the DBD and LBD of the AR. This opens up new questions.

Are the interactions direct or indirect?

It should be noted here that double hybrid assays between AR-DBD and AR-LBD did not reveal protein-protein interactions (data not shown). However, the expected interface is rather small, and the affinity between the two surfaces does not need to be high, since they are both present in close vicinity either within the same or in two dimerizing proteins. Indeed, whether these interactions are intra- or intermolecular remains to be determined.

SAXS analyses and cryo-electron microscopy structures have demonstrated NR dimer conformations with extended hinge regions and minimal interactions between the DBD and LBD (46, 49). Our results seem to be in favor of direct interactions rather than to match the more elongated common architecture for NRs (49), unless the DBD and LBD surfaces that we identified are interacting with bridging factors.

Obviously, structural analyses, such as a crystal structure of the complete AR homodimer bound to ligand, DNA, and possibly coactivator or N-terminal peptides, would provide a better picture of the exact DBD-LBD interactions. For the AR, any structural data surpassing the isolated DBD and LBD are missing. However, the positions of the residues with trans-domain effects are in accordance with a direct interface, as observed for the PPAR-RXR dimer (11).

Most importantly, it should be clear from the work presented here that the domains in the AR do not act independently but that optimal activation of transcription by the AR requires allosteric communications between different domains.

Can the DBD-LBD interactions be modulated?

It was recently reported that phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) of serine 273 on the PPARγ-LBD interface with the RXRα-DBD controls the transactivation by PPARγ (13). This opens up the possibility that receptor activities may be controlled via modulations of the DBD-LBD interactions. Although for the AR there are no data to indicate such a control, the presence of acetylation and phosphorylation sites in the hinge region that connects the DBD and LBD is intriguing (15). Another question is how the DBD-LBD interactions relate to the N/C interactions within the AR and to the coactivator interactions via LBD or via NTD. Since the LBD interacts with coactivators or with the NTD via a known hydrophobic groove which is situated on the opposite site of the proposed interface with the DBD (7, 14), we propose that the effect of the mutations described here specifically disrupts only the intra- or intermolecular DBD-LBD communications of the AR.

Estebanez-Perpina et al. described an alternative antagonist binding site at the surface of the AR-LBD (22). This surface too does not overlap the DBD-contacting patch, and hence, antagonists binding to this alternative site are not believed to directly affect the DBD-LBD interactions.

Conclusions.

We discovered seven residues in the AR which we propose to be involved in a DBD-LBD interaction: D695, R710, F754, and P766 in the LBD and K590, K592, and E621 in the DBD (Fig. 6). Mutation of these residues affected the transactivation capacity of the full-size receptor without affecting the primary function of the domain that they are situated in but by affecting the function of the adjacent domain. Importantly, since all seven residues are situated at the surface, we conclude that these residues are most likely involved in direct intra- or intermolecular communications between the DBD and LBD of the AR. The functional relevance of these communications is further indicated by the description of several cases of androgen insensitivity that correlate with mutations of these residues.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Bollen and H. De Bruyn for their excellent technical assistance.

C. Helsen was holder of a Belgian l'Oréal-UNESCO fellowship for Young Women in Life Sciences and a fellowship of the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek of Flanders. The work was supported by FWO grants G.0369.02 and G.0858.11.

Published ahead of print 29 May 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Audi L, et al. 2010. Novel (60%) and recurrent (40%) androgen receptor gene mutations in a series of 59 patients with a 46,XY disorder of sex development. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95:1876–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balk SP, Knudsen KE. 2008. AR, the cell cycle, and prostate cancer. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 6:e001 doi:10.1621/nrs.06001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bevan CL, et al. 1996. Functional analysis of six androgen receptor mutations identified in patients with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5:265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bledsoe RK, et al. 2002. Crystal structure of the glucocorticoid receptor ligand binding domain reveals a novel mode of receptor dimerization and coactivator recognition. Cell 110:93–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boehmer AL, et al. 2001. Genotype versus phenotype in families with androgen insensitivity syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 86:4151–4160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bourguet W, Ruff M, Chambon P, Gronemeyer H, Moras D. 1995. Crystal structure of the ligand-binding domain of the human nuclear receptor RXR-alpha. Nature 375:377–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buzon V, Carbo LR, Estruch SB, Fletterick RJ, Estebanez-Perpina E. 2012. A conserved surface on the ligand binding domain of nuclear receptors for allosteric control. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 348:394–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Callewaert L, et al. 2003. Implications of a polyglutamine tract in the function of the human androgen receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 306:46–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Callewaert L, Verrijdt G, Christiaens V, Haelens A, Claessens F. 2003. Dual function of an amino-terminal amphipatic helix in androgen receptor-mediated transactivation through specific and nonspecific response elements. J. Biol. Chem. 278:8212–8218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Castagnaro M, Yandell DW, Dockhorn-Dworniczak B, Wolfe HJ, Poremba C. 1993. Androgen receptor gene mutations and p53 gene analysis in advanced prostate cancer. Verh. Dtsch. Ges. Pathol. 77:119–123 (In German.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chandra V, et al. 2008. Structure of the intact PPAR-gamma-RXR- nuclear receptor complex on DNA. Nature 456:350–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cheikhelard A, et al. 2008. Long-term followup and comparison between genotype and phenotype in 29 cases of complete androgen insensitivity syndrome. J. Urol. 180:1496–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Choi JH, et al. 2011. Antidiabetic actions of a non-agonist PPARgamma ligand blocking Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation. Nature 477:477–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Claessens F, et al. 2008. Diverse roles of androgen receptor (AR) domains in AR-mediated signaling. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 6:e008 doi:10.1621/nrs.06008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clinckemalie L, Vanderschueren D, Boonen S, Claessens F. 2012. The hinge region in androgen receptor control. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 358:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Daura X, et al. 1999. Peptide folding: when simulation meets experiment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 38:236–240. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Delano WL. 2002. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. Delano Scientific, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 18. Delhaise P, et al. 1988. The Brugel package—toward computer-aided-design of macromolecules. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 6:219–219. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Denayer S, Helsen C, Thorrez L, Haelens A, Claessens F. 2010. The rules of DNA recognition by the androgen receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 24:898–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dominguez C, Boelens R, Bonvin AM. 2003. HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:1731–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dubbink HJ, et al. 2004. Distinct recognition modes of FXXLF and LXXLL motifs by the androgen receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 18:2132–2150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Estebanez-Perpina E, et al. 2007. A surface on the androgen receptor that allosterically regulates coactivator binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:16074–16079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Evans BA, et al. 1996. Low incidence of androgen receptor gene mutations in human prostatic tumors using single strand conformation polymorphism analysis. Prostate 28:162–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Farla P, et al. 2004. The androgen receptor ligand-binding domain stabilizes DNA binding in living cells. J. Struct. Biol. 147:50–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferlin A, et al. 2006. Male infertility and androgen receptor gene mutations: clinical features and identification of seven novel mutations. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 65:606–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ghali SA, et al. 2003. The use of androgen receptor amino/carboxyl-terminal interaction assays to investigate androgen receptor gene mutations in subjects with varying degrees of androgen insensitivity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88:2185–2193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haelens A, et al. 2001. Androgen-receptor-specific DNA binding to an element in the first exon of the human secretory component gene. Biochem. J. 353:611–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hannema SE, et al. 2004. Residual activity of mutant androgen receptors explains Wolffian duct development in the complete androgen insensitivity syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89:5815–5822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. He B, Kemppainen JA, Wilson EM. 2000. FXXLF and WXXLF sequences mediate the NH2-terminal interaction with the ligand binding domain of the androgen receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 275:22986–22994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. He B, Minges JT, Lee LW, Wilson EM. 2002. The FXXLF motif mediates androgen receptor-specific interactions with coregulators. J. Biol. Chem. 277:10226–10235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Helsen C, et al. Structural basis for nuclear hormone receptor DNA binding. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 348:411–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hiort O, et al. 2000. Significance of mutations in the androgen receptor gene in males with idiopathic infertility. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85:2810–2815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hiort O, Sinnecker GH, Holterhus PM, Nitsche EM, Kruse K. 1996. The clinical and molecular spectrum of androgen insensitivity syndromes. Am. J. Med. Genet. 63:218–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hiort O, Sinnecker GH, Holterhus PM, Nitsche EM, Kruse K. 1998. Inherited and de novo androgen receptor gene mutations: investigation of single-case families. J. Pediatr. 132:939–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Idkowiak J, et al. 2010. Concomitant mutations in the P450 oxidoreductase and androgen receptor genes presenting with 46,XY disordered sex development and androgenization at adrenarche. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95:3418–3427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jaaskelainen J, et al. 2006. Human androgen receptor gene ligand-binding-domain mutations leading to disrupted interaction between the N- and C-terminal domains. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 36:361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jeske YW, et al. 2007. Androgen receptor genotyping in a large Australasian cohort with androgen insensitivity syndrome; identification of four novel mutations. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 20:893–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kalkhoven E, Valentine JE, Heery DM, Parker MG. 1998. Isoforms of steroid receptor co-activator 1 differ in their ability to potentiate transcription by the oestrogen receptor. EMBO J. 17:232–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. The Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research 2012. Androgen Receptor Gene Mutation Database. The Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. http://androgendb.mcgill.ca/

- 40. Luisi BF, et al. 1991. Crystallographic analysis of the interaction of the glucocorticoid receptor with DNA. Nature 352:497–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marcelli M, et al. 1991. A mutation in the DNA-binding domain of the androgen receptor gene causes complete testicular feminization in a patient with receptor-positive androgen resistance. J. Clin. Invest. 87:1123–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Matias PM, et al. 2000. Structural evidence for ligand specificity in the binding domain of the human androgen receptor. Implications for pathogenic gene mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 275:26164–26171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Meijsing SH, Elbi C, Luecke HF, Hager GL, Yamamoto KR. 2007. The ligand binding domain controls glucocorticoid receptor dynamics independent of ligand release. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:2442–2451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meijsing SH, et al. 2009. DNA binding site sequence directs glucocorticoid receptor structure and activity. Science 324:407–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nemoto T, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Shimazaki S, Ota M. 1994. Dimerization characteristics of the DNA- and steroid-binding domains of the androgen receptor. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 50:225–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Orlov I, Rochel N, Moras D, Klaholz BP. 2012. Structure of the full human RXR/VDR nuclear receptor heterodimer complex with its DR3 target DNA. EMBO J. 31:291–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Putcha BD, Fernandez EJ. 2009. Direct interdomain interactions can mediate allosterism in the thyroid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 284:22517–22524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ris-Stalpers C, et al. 1991. Substitution of aspartic acid-686 by histidine or asparagine in the human androgen receptor leads to a functionally inactive protein with altered hormone-binding characteristics. Mol. Endocrinol. 5:1562–1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rochel N, et al. 2011. Common architecture of nuclear receptor heterodimers on DNA direct repeat elements with different spacings. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18:564–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schaufele F, et al. 2005. The structural basis of androgen receptor activation: intramolecular and intermolecular amino-carboxy interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9802–9807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shaffer PL, Jivan A, Dollins DE, Claessens F, Gewirth DT. 2004. Structural basis of androgen receptor binding to selective androgen response elements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:4758–4763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shiau AK, et al. 1998. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell 95:927–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shkolny DL, et al. 1999. Discordant measures of androgen-binding kinetics in two mutant androgen receptors causing mild or partial androgen insensitivity, respectively. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84:805–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tadokoro R, Bunch T, Schwabe JW, Hughes IA, Murphy JC. 2009. Comparison of the molecular consequences of different mutations at residue 754 and 690 of the androgen receptor (AR) and androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) phenotype. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 71:253–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tanenbaum DM, Wang Y, Williams SP, Sigler PB. 1998. Crystallographic comparison of the estrogen and progesterone receptor's ligand binding domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:5998–6003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. van de Wijngaart DJ, Dubbink HJ, van Royen ME, Trapman J, Jenster G. 2012. Androgen receptor coregulators: recruitment via the coactivator binding groove. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 352:57–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. van Royen ME, et al. 2007. Compartmentalization of androgen receptor protein-protein interactions in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 177:63–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. van Tilborg MA, et al. 2000. Mutations in the glucocorticoid receptor DNA-binding domain mimic an allosteric effect of DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 301:947–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wang Q, et al. 1998. Azoospermia associated with a mutation in the ligand-binding domain of an androgen receptor displaying normal ligand binding, but defective trans-activation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 83:4303–4309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wurtz JM, et al. 1996. A canonical structure for the ligand-binding domain of nuclear receptors. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3:87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yong EL, Tut TG, Ghadessy FJ, Prins G, Ratnam SS. 1998. Partial androgen insensitivity and correlations with the predicted three dimensional structure of the androgen receptor ligand-binding domain. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 137:41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang J, et al. 2011. DNA binding alters coactivator interaction surfaces of the intact VDR-RXR complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18:556–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zoppi S, et al. 1992. Amino acid substitutions in the DNA-binding domain of the human androgen receptor are a frequent cause of receptor-binding positive androgen resistance. Mol. Endocrinol. 6:409–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.