Abstract

The biological role of vitamin D receptors (VDR), which are abundantly expressed in developing zebrafish (Danio rerio) as early as 48 h after fertilization, and before the development of a mineralized skeleton and mature intestine and kidney, is unknown. We probed the role of VDR in developing zebrafish biology by examining changes in expression of RNA by whole transcriptome shotgun sequencing (RNA-seq) in fish treated with picomolar concentrations of the VDR ligand and hormonal form of vitamin D3, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1α,25(OH)2D3)].We observed significant changes in RNAs of transcription factors, leptin, peptide hormones, and RNAs encoding proteins of fatty acid, amino acid, xenobiotic metabolism, receptor-activator of NFκB ligand (RANKL), and calcitonin-like ligand receptor pathways. Early highly restricted, and subsequent massive changes in more than 10% of expressed cellular RNA were observed. At days post fertilization (dpf) 2 [24 h 1α,25(OH)2D3-treatment], only four RNAs were differentially expressed (hormone vs. vehicle). On dpf 4 (72 h treatment), 77 RNAs; on dpf 6 (120 h treatment) 1039 RNAs; and on dpf 7 (144 h treatment), 2407 RNAs were differentially expressed in response to 1α,25(OH)2D3. Fewer RNAs (n = 481) were altered in dpf 7 larvae treated for 24 h with 1α,25(OH)2D3 vs. those treated with hormone for 144 h. At dpf 7, in 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated larvae, pharyngeal cartilage was larger and mineralization was greater. Changes in expression of RNAs for transcription factors, peptide hormones, and RNAs encoding proteins integral to fatty acid, amino acid, leptin, calcitonin-like ligand receptor, RANKL, and xenobiotic metabolism pathways, demonstrate heretofore unrecognized mechanisms by which 1α,25(OH)2D3 functions in vivo in developing eukaryotes.

Vitamin D3 through its active metabolite, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1α,25(OH)2D3], plays a critical role in calcium and phosphorus homeostasis by increasing intestinal calcium and phosphorus transport, thereby maintaining normal serum calcium and phosphorus concentrations and allowing bone mineralization to proceed (1, 2). To function in target tissues, 1α,25(OH)2D3 binds to its receptor, the vitamin D receptor (VDR), and the ligand-bound receptor, either as a heterodimer with the retinoic acid X-receptor, or as a homodimer, activates the expression of various genes, many of which encode proteins that alter trans-epithelial calcium transport (1–8). The VDR is expressed in a variety of tissues including the intestine, kidney, bone, skin, and brain of mammals and fish (9–17). Earlier, we showed that the VDR is expressed in the intestine, kidney, gill-transporting cells, and bone of the adult zebrafish, Danio rerio (17). In addition, the skin, olfactory organ, retina, brain, spinal cord, Sertoli cells of the testis, oocytes, pancreatic acinar cells, hepatocytes, and bile duct epithelial cells express substantial amounts of the VDR. In 48 h post fertilization (hpf) and 96 hpf zebrafish embryos/larvae, the VDR was noted in cartilage, brain, retina, and otic vesicles, suggesting that the VDR and its ligand, 1α,25(OH)2D3, play a role in the biology and development of these organs (17). The role of 1α,25(OH)2D3 in early development, however, has not been defined in vivo.

The effects of 1α,25(OH)2D3 on global gene expression in lymphoblast and macrophage lines have been examined using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and massively parallel sequencing (CHIP-seq) (18–20). In lymphoblastoid cells, after 1α,25(OH)2D3 stimulation, Ramagopalan et al. (18) found 2776 genomic positions occupied by the VDR. Microarray analysis demonstrated significant changes in the expression of 229 genes in response to 1α,25(OH)2D3. Two hundred and twenty six genes were up-regulated, and three genes were down-regulated by 1α,25(OH)2D3. In human monocytic leukemia cells, Heikkinen et al. (19), identified 2340 VDR binding locations by ChIP-seq, of which 1171 and 520 occurred uniquely with and without 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment, respectively. Microarray analysis demonstrated that the expression of 638 genes was altered after 1α,25(OH)2D3-treatment; 408 genes were up-regulated and 230 genes were down-regulated. These studies indicate that 1α,25(OH)2D3 regulates the expression of numerous genes in cultured cells. No information, however, is available on the influence of 1α,25(OH)2D3 on gene expression in whole animals in vivo, and correlations between changes in gene expression profiles and morphological change in vivo have not been performed.

The small size and transparency of zebrafish in early development allow the simultaneous assessment of morphological and gene expression changes in vivo. The effects of various agents such as sterols [e.g. 1α,25(OH)2D3], steroids and peptide hormones can be assessed by adding such substances to the medium in which the zebrafish is maintained (21). In zebrafish, the skeleton develops in a stereotypical pattern in which cartilage formation begins at about 48 h post fertilization (hpf), and is followed by mineralization of the aforesaid structures at about 144 hpf (22, 23). These changes can be readily visualized because of the transparency of the fish and available staining procedures specific for cartilage and bone. Changes in gene expression patterns can be correlated with changes in cartilage development (before ∼120 hpf) and bone (after 120 hpf). Additionally, the brain, eye, and otic structures develop rapidly before 24 hpf and continue to show significant change even after 24 hpf. The effects of 1α,25(OH)2D3 on these structures can be assessed as well.

To determine the influence of 1α,25(OH)2D3 on gene expression patterns and metabolic pathways in vivo, we treated zebrafish embryos/larvae with 1α,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle and assessed RNA expression at various times after addition of 1α,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle with whole transcriptome shotgun sequencing (RNA-seq). We demonstrate that multiple, previously unrecognized transcription factors, peptide hormone and metabolic pathways, are altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 in the developing zebrafish.

Materials and Methods

Treatment of zebrafish with 1α,25(OH)2D3

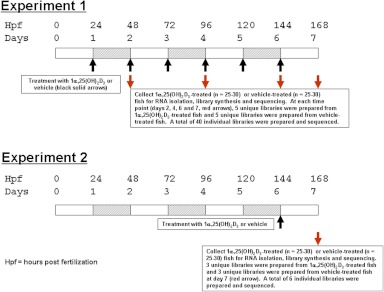

Zebrafish embryos were obtained from mating of Segrest wild-type parents under controlled barrier conditions, in the Mayo Clinic Zebrafish Core Facility, in Instant Ocean media (Spectrum Brands, Madison, WI) (24). Zebrafish embryos (100–120) were placed in 20 ml embryo medium (pH 7.2) containing 1-phenyl-2-thiourea [0.003% (wt/vol)] and were maintained at 28–30 C (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). At 24 hpf (1 d post fertilization, dpf), 10 μl 1α,25(OH)2D3 in ethanol (gift of Dr. Milan Uskokovic, Hoffmann LaRoche, Nutley, NJ), was added to embryos maintained in 20 ml fresh embryo medium with 1-phenyl-2-thiourea. The final concentration of 1α,25(OH)2D3 was 300 pm. Control zebrafish were treated with 10 μl ethanol alone (vehicle controls). The medium containing either 300 pm 1α,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle was changed every 24 h. In experiment 1 (see Fig. 1), at 2, 4, 6, and 7 dpf batches of embryos/larvae were removed and immediately frozen at −80 C for later RNA preparations. Twenty five to 30 embryos/larvae were used for preparation of RNA. Five individual cDNA libraries from 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated or vehicle-treated fish were prepared at each time point (e.g. 2, 4, 6, or 7 d). Forty individual libraries (20 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated and 20 vehicle-treated) were prepared in experiment 1. At the same times, seven to 12 embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.75× Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS). In experiment 2 (see Fig. 1), 6 dpf larvae were treated with 1α,25(OH)2D3 (300 pm) or vehicle for 24 h. RNA was prepared from three sets of larvae. Six individual libraries (three 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated and three vehicle-treated) were prepared in experiment 2.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design. Experiment 1: zebrafish embryos were treated with 1α,25(OH)2D3 (300 pm) or vehicle beginning at 24 hpf. Medium and additives were changed to every 24 h (black arrows). Five batches of 25–30, 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated, and five batches of 25–30 vehicle-treated zebrafish embryos/larvae were collected at 2, 4, 6, and 7 dpf (red arrows) for isolation of RNA, construction of cDNA libraries, and sequencing. Experiment 2: zebrafish larvae were treated with 1α,25(OH)2D3 (300 pm) or vehicle beginning at 144 hpf; 24 h later, three batches of 25–30 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated and three batches of 25–30 vehicle-treated zebrafish were collected (red arrow) for isolation of RNA, construction of cDNA libraries, and sequencing.

Measurement of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1α,25-dihydoxyvitamin D in zebrafish larvae

The concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D2, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D2, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in 7 dpf zebrafish larvae were measured using mass spectroscopy and hexadeuterated standards (25, 26). Nine hundred zebrafish larvae were suspended in 1.5 ml buffer (80 mm Tris, 200 mm NaCl, pH 7.4) and homogenized with a Polytron homogenizer (Brinkmann Instruments, Ontario, Canada) using three 5-sec pulses. The lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min in an Eppendorf 5415C centrifuge (Brinkmann Instruments, Westbury, NY) to obtain a clear supernatant. Protein concentration was measured in the supernatant using the bicinchoninic assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) using the manufacturer's protocol. The homogenization and centrifugation was carried out at 4 C. Ethyl acetate (2 ml) was added to 0.5-ml aliquots of the clarified lysate in a glass test tube at room temperature, and the sample was vortexed for 1 min. The layers were allowed to separate and the upper organic layer was collected. This step was repeated with 1 ml of ethyl acetate. The combined organic layers were dried under a gentle flow of nitrogen. The dried residue was resuspended in 0.5 ml stripped human serum, and deuterated 25-hydroxyvtamin D3, 25-hydroxyvtamin D2, and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D2 were added to the sample. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D2 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D2 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 were measured as described elsewhere (25, 26). Both measurements were performed in triplicate.

Alcian blue and alizarin red staining of embryos/larvae

Zebrafish embryos/larvae were stained with alcian blue 8GX (Sigma-Aldrich no. A3157; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) according to Walker and Kimmel (27). The final staining solution contained 0.003% alcian blue, 130 mm MgCl2, in 70% ethanol. The solution was filtered through a 0.2-μm filter. Fixed zebrafish embryos/larvae were stained with alcian blue solution overnight at room temperature. Embryos/larvae were destained with 20% glycerol-0.25% KOH followed by 50% glycerol-0.25% KOH for several days at room temperature. Embryos/larvae were bleached to remove endogenous pigmentation, with 1.5% H2O2-1% KOH for 50 min at room temperature. Embryos/larvae were finally washed once with water and placed in 20% glycerol-0.25% KOH.

For alizarin red staining, embryos/larvae were fixed for 50 min in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.75× DPBS and were washed once with 1 ml DPBS. A solution of alizarin red S, 0.05% (Sigma-Aldrich; no. A-5533), 10 mm MgCl2, in 70% ethanol was prepared. Embryos/larvae were stained at room temperature overnight. Excess stain was removed by washing with water. Tissues were clarified with 0.25% KOH-20% glycerol overnight, followed by 0.25% KOH-50% glycerol, with several solution changes until background tissue staining was reduced. Endogenous pigments were bleached with 1.5% H2O2-1% KOH as described above for alcian blue staining. The intensity of red staining was determined using the KS 400 Image analysis program (Carl Zeiss, North America, Thornwood, NY).

RNA preparation for RNA-seq and QPCR

RNA was prepared using RNA/protein spin columns (CLONTECH Laboratories, Mountain View, CA). Lysis solution was added to 25–30 frozen embryos/larvae, and embryos/larvae were lysed by passage of tissue successively through 21- and 27-gauge needles. Individual embryo/larvae lysates were applied to RNA spin columns for purification. RNA eluted into nuclease-free water was immediately frozen at −80 C. Before library construction, RNA quality was assessed by capillary electrophoresis against a known size standard in the Mayo Molecular Biology Core facility.

Quantitative PCR (QPCR)

QPCR was carried out using a Roche LightCycler 480 QPCR apparatus in 96-well QPCR plates (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN). An I-Script RT-PCR kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) was used to generate double-stranded DNA from RNA. Reverse transcribed I-script product was used to generate PCR products with each primer pair. Product was quantitated and used to generate standard QPCR curves. QPCR data were subjected to quantitation against 18S RNA or tubulin α1, using software supplied with the instrument. Ten RNA samples (five control and five experimental, 7 dpf) were analyzed in triplicate by QPCR. QPCR primers used were: Danio rerio (in all cases) cytochrome P450, cyp24a1, 5′-oligonucleotide: 5′-gcgtctcgctgagttacaga-3′; 3′-oligonucleotide: 5′-ccaggtctgttgccacaat-3′. IGF 2a, igf2a, 5′-oligonucleotide: 5′-tgaagtcggagcgagatgtt-3′; 3′-oligonucleotide: 5′-ggagtacttcacatttatggtgtcc-3′. IGF-binding protein 1b, igfbp1b, 5′-oligonucleotide: 5-′gcagaagctcatccagcag-3′; 3′-oligonucleotide: 5′-gggcaggtagaaactggtga-3′. Kruppel-like factor 11a, klf11a, 5′-oligonucleotide: 5′-tggtctccctctcatcactgt; 3′-oligonucleotide: 5′-caggccactgaggtactgaga-3′. Leptin receptor, lepr, 5′-oligonucleotide: 5′-ccaaaggaatggacttcagg3′; 3′-oligonucleotide: 5′-tcggagaccagcagcaat-3′. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α a (pparaa), 5′-oligonucleotide: 5′-gcaggaacagcttgtctacctt3′; 3′-oligonucleotide: 5′-gaccacggcaagatttgaa-3′. βactin2, bactin2, 5′-oligonucleotide: 5′-aaggccaacagggaaaagat-3′; 3′-oligonucleotide: 5′-gtggtacgaccagaggcatac-3′. 18s ribosomal RNA, 5′-oligonucleotide: 5′-tcgctagttggcatcgtttatg-3′; 3′-oligonucleotide: 5′-cggaggttcgaagacgatca-3′. Tubulin α1, 5′-oligonucleotide: 5′-ttgtagacctggagcccact-3′; 3′-oligonucleotide: 5′-ttcctttcctgtgatgagctg-3′.

Preparation of libraries

mRNA-seq libraries were prepared using the mRNA v1 sample prep kit following the manufacturer's protocol (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). Poly-A containing mRNA was purified using poly-T oligo attached magnetic beads. The purified mRNA was fragmented using divalent cations at 95 C for 5 min and ethanol precipitated. The RNA fragments were copied into first-strand cDNA using reverse transcriptase and random primers. Second-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using DNA polymerase I and ribonuclease H. The cDNA was purified using Qiaquick PCR columns from QIAGEN (Chatsworth, CA). The ends were repaired and phosphorylated using Klenow, T4 polymerase, and T4 polynucleotide kinase, after which an A base was added to the 3′-ends of double-stranded DNA using Klenow exo- (3′ to 5′ exo minus). Paired end DNA adaptors (Illumina) with a single T base overhang at the 3′-end were ligated and the resulting constructs were separated on a 2% agarose gel. DNA fragments of approximately 250–300 bp were excised from the gel using GeneCatcher tips and purified using Qiagen Gel Extraction Kits. The adapter-modified DNA fragments were enriched by 15 cycles of PCR using primers PE 1.0 and PE 2.0 (Illumina). The concentration and size distribution of the libraries were determined on an Agilent Bioanalyzer DNA 1000 chip (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA).

Libraries were loaded onto paired end-flow cells at concentrations of 6 pm to generate cluster densities of 400,000/mm2 following Illumina's standard protocol using the Illumina cBot and cBot Paired end cluster kit version 2. The flow cells were sequenced as 51 × 2 paired end reads on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 using TruSeq SBS sequencing kit version 1 or version 3 and SCS version 1.1.37.0 or HCS version 1.4.8 data collection software, respectively. Base calling was performed using Illumina's RTA version 1.7.45.0.

mRNA-seq data analysis

Mapping of sequence reads

The generated FASTQ sequence reads from an Illumina HiSEQ instrument were aligned to both the latest available zebrafish genome assembly (zv9) and our in-house exon junction database using Burrows-Wheeler alignment (28). In the exon junction database, unidirectional combinations of exon junction database for the sequencing length of 50 bases were generated using exon boundaries defined by the refFlat file from University of California Santa Clara (UCSC) Table Browser. Burrows-Wheeler alignment is a fast and accurate short reads aligner. A maximum of two mismatches was allowed for first 32 bases in each alignment, and reads that had more than two mismatches or were mapped to multiple genomic locations (alignment score less than 4) were discarded. The aligned sequence tags were counted for each annotated gene/exon using a custom program based on the UCSC genome binning approach (29). A total of 14,267 genes were annotated using RefSeq RNA database, and the raw read counts for genes were generated for further downstream analyses.

Differential gene expression analysis

The raw reads count from each gene were normalized by the total reads of each biological replicate and then standardized to reads per million (gene counts/total counts of each biological replicate * 1,000,000). For differential gene expression analysis between different conditions, we eliminated genes without any reads across all samples. Statistical testing was done using the R package DESeq (30). Because the primary goal of our analysis was to explore the underlying cause of differentially expressed genes between vehicle- and 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated conditions at each time point, an adjusted P value/false discovery rate (to adjust for multiple testing using the Benjamin-Hochberg method) cut-off of 0.01 was used to select significant changed genes.

Pathway analysis for differentially expressed genes

We conducted pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes using DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery v6.7) (31, 32) and DIRAC (Differential Rank Conservation) (33, 34). An adjusted P value less than 0.01 was used to assign biological significance. The goal was to investigate whether the differentially expressed genes at each time point were enriched with genes in canonical pathways and interconnected biological networks involving genes with functional commonalities. DAVID is a web resource consisting of an integrated biological knowledgebase and analytical tools that aims to extract and understand biological themes in large gene lists. It provides the gene functional classification as well as the identification (ID) conversion of the list of gene ID accessions to any other accession of choice. It also provides pathways from other databases such as Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (35–37), Panther (38), BioCarta, and Reactome (39), and provides tissue expression and disease-specific information based on represented genes. The results were further confirmed with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis 8.6 (IPA; Ingenuity Systems, Mountain View, CA). In IPA, the differentially expressed zebrafish gene ID were first mapped to human orthologs based on BLAST results between the two organisms (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/repository/UniGene). With these orthologs and the adjusted P values generated from statistical analysis at each time point, we queried IPA to map and generate putative networks and pathways based on the manually curated knowledge database of pathway interactions extracted from the literature. The gene network was generated using both direct and indirect relationships/connectivity. These networks were ranked by scores that measured the probability that the genes were included in the network by chance alone.

DIRAC analysis

The DIRAC algorithm (33, 34) relies on the ranks of genes within each pathway to estimate perturbation levels. Because genes must be compared within samples as well as across samples, standard read counts or reads per million would introduce bias for physically longer genes. As a result, all read counts were normalized into reads per kilobase exon per million [RPKM (gene counts/kilobase of exon for that gene/total counts of each biological replicate) * 1,000,000] (40). The length of each gene was calculated using the latest Zebrafish genome assembly (zv9). Version 3 of the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis canonical pathways was obtained (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/), which includes 880 pathways from KEGG (35–37), Biocarta, and Reactome (39). Zebrafish genes were mapped to human orthologs using the ZFIN orthology database (http://zfin.org/zf_info/downloads.html#orthology). The DIRAC algorithm calculates the relative ranks of all mapped genes in each pathway for each sample within a treatment condition [e.g. ethanol or 1α,25(OH)2D3]. These relative ranks are used to determine a rank template, or the permutation of genes that best represents all samples within each condition. The difference in rank template for each treatment condition is then calculated, and the significance of this difference is measured using 1000 permutations of the class labels. A P value of 0.01 was used to determine significantly perturbed pathways.

Data sharing

All of the sequence data that were analyzed in this report have been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (Accession #GSE38575).

Results

We performed genome-wide transcriptional profiling in five replicate cDNA libraries of 1α,25(OH)2D3- or vehicle-treated zebrafish, 48, 96, 144, and 168 hpf [Fig. 1, experiment 1; 24, 72, 120, and 144 h continuous treatment with 1α,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle]. RNA samples for cDNA library construction were obtained from 25–30, 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated zebrafish and 25–30 vehicle-treated zebrafish. Five independent, 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated or vehicle-treated libraries were prepared at each time point. Forty independent libraries were subjected to Illumina DNA sequencing. We used 300 pm concentrations of 1α,25(OH)2D3 in the embryo medium because circulating serum 1α,25(OH)2D3 concentrations range between 200 and 600 pm (41, 42). The concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D2, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D2 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in fish larvae were below the limit of detection (defined as the signal-to-noise-ratio, m/z >8) of the method (2 ng/ml and 4 pg/ml for 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, respectively). In a second experiment (Fig. 1, experiment 2; 24 h treatment between dpf 6 and dpf 7), three replicate cDNA libraries from 1α,25(OH)2D3- or vehicle-treated zebrafish were prepared. In experiment 1, the RNA-Seq data obtained from 48, 96, 144, and 168 hpf zebrafish RNA showed approximately 235 million, 223 million, 278 million, and 257 million total reads, respectively (Table 1). Of the total number of reads at each time point, 80.7%, 80.5%, 79.2%, and 79.1% were successfully mapped to known genes. Similar results were obtained for 168 hpf zebrafish larvae (24 h treatment) in experiment 2. On average, 13,351 transcripts with more than 10 reads were mapped and identified at the four times analyzed in experiment 1, representing a substantial fraction of all known protein coding genes (n = 18,744) in the Sanger zebrafish genome assembly Zv9 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/D_rerio/). Supplemental Fig. 1 (published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org), shows correlation plots between biological replicates in the samples from 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated zebrafish on dpf 2.

Table 1.

Overview of RNA-Seq results

| Day 2 |

Day 4 |

Day 6 |

Day 7 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 1α,25(OH)2D3 | Vehicle | 1α,25(OH)2D3 | Vehicle | 1α,25(OH)2D3 | Vehicle | 1α,25(OH)2D3 | |

| Total reads | 2.45E + 08 | 2.35E + 08 | 2.53E + 08 | 2.23E + 08 | 2.81E + 08 | 2.78E + 08 | 2.33E + 08 | 2.57E + 08 |

| Mapped reads | 1.98E + 08 | 1.9E + 08 | 2.04E + 08 | 1.81E + 08 | 2.24E + 08 | 2.21E + 08 | 1.87E + 08 | 2.04E + 08 |

| Percentage of mapped reads | 80.74 | 80.68 | 80.06 | 80.5 | 79.22 | 79.24 | 79.74 | 79.16 |

On dpf 2 (48 hpf), after 24 h 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment, RNA for the cyp24A1 encoding the 24-hydroxlase cytochrome P-450 responsible for degradation of 1α,25(OH)2D3, increased 6.8-fold relative to vehicle treatment (adjusted P value 5.1−47). Significant decreases for the npas4, fosb, and fos RNA for the neuronal PAG containing helix-loop-helix transcription factor and the FBJ osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B transcription factors, were noted in 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated zebrafish when compared with vehicle-treated zebrafish (P < 0.01 for all; 1.9-, 2.5-, and 1.7-fold decreases). We used adjusted P values of <0.01, corrected for multiple hypotheses testing, as a cutoff to provide robust statistical power to assure biological validity of the observed change. Additionally, the analysis of 10 individual libraries [five for 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment and five for vehicle] enhances the statistical and biological validity of our observations. When the data were analyzed using the DAVID (v6.7) (31, 32) program, specific pathways were not shown to be perturbed. Additional analysis with the DIRAC program (33, 34) showed that genes in the classical antibody-mediated complement activation, graft vs. host disease, glucuronidation, pyruvate dehydrogenase, granulocyte, and allograft rejection pathways were perturbed (P = 0.01).

On dpf 4 (96 hpf), after 72 h 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment, cyp24a1 RNA is significantly increased 7.2-fold (P = 8.9−57), (Supplemental Table 1). Significant changes in RNA for transcription factors are noted. The RNA for klf11a and klf11b (Kruppel-like 11) transcription factors increased 2.3- and 1.5-fold; the RNA for bcl6 (B-cell CLL/lymphoma 6) increased 1.6-fold. In contrast, there was a significant 2.3-fold decrease in the RNA for fosb (FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B) and a 2.3-fold decrease for tfcp2l1 transcription factor (CP2-like L1). Ligand-dependent vitamin D receptors, vdra and vdrb (vitamin D receptor) decreased approximately 1.5-fold; the RNA for pparα also decreased 1.8-fold. The RNA for igfbp1a and b (IGF-binding protein 1) were increased 4.1- and 1.9-fold. RNAs for a number of enzymes such as elastase 2 were decreased. The RNA for the slc34a2 (sodium-phosphate transporter IIa) was diminished. Analysis by DAVID analysis showed no specific pathway change. DIRAC analysis, however, demonstrated perturbation in the graft vs. host disease, pentose and glucuronate interconversions, JAK-STAT, hormone ligand binding receptors, glucuronidation, translocation of ZAP-70 to immunological synapse, and nuclear receptors in lipid metabolism and toxicity pathways (P = 0.01).

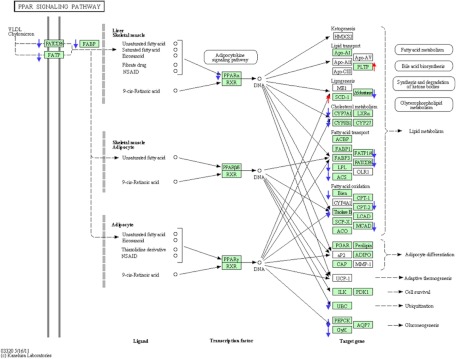

On dpf 6 [120-h 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment], 1039 RNA were either increased or decreased (Supplemental Table 2). RNA for cyp24a1 increased 7.9-fold (P = 8.3−86). RNA for transcription factors klf11a, klf11b, klf3, and klfd were increased 5.1-, 1.86-, 1.67-, and 1.61-fold. Klf2b RNA decreased 1.54-fold. B-cell CLL/lymphoma 6 transcription factor RNA increased 1.8-fold. The forkhead box transcription factors, foxo1 and forkhead box L1-like, increased 2.0-fold. Fos-like antigen 2 and mycn (v-myc myelocytamatosis viral-related oncogene) RNAs were increased approximately 1.6-fold. Ligand-dependent vitamin D receptor RNAs, vdra and vdrb, were decreased, as was the RNA for pparα. Notably, RNAs for several hormones and their binding proteins were altered. The RNA for lepa (leptin) was increased 6.2-fold (P = 8.15−19). Ins (insulin) and gh1 (GH) RNA amounts diminished 3.3- and 2.0-fold (both P < 0.01). The igf2a and igf2b RNA (IGF 2a and 2b) increased significantly by 1.5- and 2.1-fold; RNAs for the igfbp1a, 1b, and 4 increased significantly (2.8-, 7.4-, and 2.8-fold), whereas RNAs for the igf2a, 2b, and 6b diminished 2.2-, 2.0-, and 1.6-fold. RNAs for several G protein-coupled receptors were regulated by 1α,25(OH)2D3, the most notable of which was the RNAs for oxgr (2-oxoglutarate receptor 1) which was altered 25-fold. Numerous transporter and channel RNAs were altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3, the most notable of which was the aqp8 (aquaporin 8) RNA. Analysis by DAVID showed the following pathways to be altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 (Table 2): the PPAR-modulated pathway; fatty acid metabolism; retinol metabolism; glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism; tryptophan metabolism; arginine and proline metabolism; valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation metabolic pathways. Figure 2 shows that the PPAR pathway is enriched in differentially expressed genes at dpf 6 when analyzed by DAVID. RNAs indicated with a red up or blue down arrow were either increased or decreased after 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment. The change in expression of genes in the PPAR pathway assessed by the DAVID program was confirmed by IPA analysis (P = 0.0374). The different P values obtained from DAVID and IPA analysis is due to different databases used by the two programs. Examples of changes noted at d 6 in the other pathways analyzed with DAVID are shown in Supplemental Figs. 2–4. Analysis by DIRAC (Table 3) showed that additional pathways of relevance to cartilage and bone physiology were altered. For example, the receptor-activator of NFκB ligand (RANKL) and calcitonin-like ligand receptor pathways were altered after 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment. The TALL1 (TNF and TNF receptor signaling) pathway and the angiotensin II pathway were also noted to be perturbed after 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment. The RNA-seq data on d 7 were validated by assessing the cyp24a1, igf2a, igfbp1b, klf11a, lepr, pparaa, bactin2, 18sRNA, and tuba1 by an RT-PCR method. 18sRNA or tuba1 was used to normalize the data. In all instances, RNAs that were increased or decreased on RNA-seq analysis were also changed in the same direction on QPCR analysis. For bactin (1.4-fold change by QPCR vs. 0.94 change by RNA-seq), igf2a (1.7-fold change by QPCR vs. 1.7 change by RNA-seq), igfbp1b (4.2-fold change by QPCR vs. 3.6 change by RNA-seq), klf11a (6.7-fold change by QPCR vs. 11.1 change by RNA-seq), lepr (1.5-fold change by QPCR vs. 1.6 change by RNA-seq), and pparaa (0.8-fold change by QPCR vs. 0.4 change by RNA-seq). Increases in cyp24a1 RNA amounts after treatment of zebrafish for 6 d (144 h) with 30 pm 1α,25(OH)2D3 demonstrated a 11.2-fold change cyp24a1 RNA amounts.

Table 2.

Pathways significantly altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment on dpf 6 [120 h of 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment]

| KEGG pathway term | Gene count | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| PPAR signaling pathway | 22 | 3.21E-12 |

| Glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism | 15 | 2.75E-10 |

| Fatty acid metabolism | 14 | 1.56E-08 |

| Tryptophan metabolism | 14 | 1.13E-07 |

| Arginine and proline metabolism | 17 | 1.52E-07 |

| Valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation | 12 | 1.60E-05 |

| Drug metabolism | 8 | 1.84E-04 |

| Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | 8 | 1.84E-04 |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | 9 | 4.06E-04 |

| Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | 7 | 4.09E-04 |

| β-Alanine metabolism | 7 | 5.69E-04 |

| Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | 12 | 7.37E-04 |

| Retinol metabolism | 8 | 7.43E-04 |

| Butanoate metabolism | 8 | 9.42E-04 |

| Histidine metabolism | 7 | 0.00103 |

| Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | 5 | 0.004057 |

| Glutathione metabolism | 8 | 0.00519 |

| Steroid hormone biosynthesis | 7 | 0.007196 |

| Linoleic acid metabolism | 5 | 0.00972 |

| d-Arginine and d-ornithine metabolism | 3 | 0.010055 |

| Drug metabolism | 7 | 0.011572 |

| α−Linolenic acid metabolism | 4 | 0.018004 |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | 7 | 0.025381 |

| Primary bile acid biosynthesis | 4 | 0.030237 |

| Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism | 4 | 0.030237 |

Analysis was performed using the DAVID v6.7 program. CoA, Coenzyme A.

Fig. 2.

PPAR signaling pathway is significantly altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment on dpf 6 [120-h 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment]. RNAs increased after 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment (compared with vehicle) are indicated by red up arrows, and RNAs decreased after 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment are indicated by blue down arrows. RXR, Retinoid X receptor; UCP, uncoupling protein; VLDL, very-low density lipoprotein.

Table 3.

Pathways significantly perturbed by 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment on dpf 6 [120 h of 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment]

| Pathway | Database | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| RNA polymerase III chain elongation | Reactome | 0.001367 |

| Graft vs. host disease | KEGG | 0.002477 |

| Classical antibody-mediated complement activation | Reactome | 0.002477 |

| Calcitonin-like ligand receptors | Reactome | 0.002533 |

| RANKL pathway | Biocarta | 0.002747 |

| Antigen- dependent B cell activation pathway | Biocarta | 0.004460 |

| Apoptotic cleavage of cell adhesion proteins | Reactome | 0.004460 |

| ACE2 pathway | Biocarta | 0.004460 |

| FAS Signaling | SigmaAldrich | 0.006892 |

| α−Linolenic acid metabolism | KEGG | 0.006892 |

| JNK phosphorylation and activation mediated by activated human TAK1 | Reactome | 0.007631 |

Analysis was performed using the DIRAC algorithm.

Differential gene expression in response to 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment on dpf 7 (144 h treatment) is shown in Supplemental Table 3. The RNA molecules increased to the greatest extent in response to 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment on dpf 7 (144 h treatment) are those for lepb (leptin b), lepa (leptin a), hspa8 (heat shock protein), klf11, oxgr1, slc1a4, il1b (IL 1β), hbbϵ (hemoglobin ϵ), cpa2, scd5, and cyp24a1. The RNA molecules most decreased in response to 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment are those for aquaporin 8 (aqp8), Rh family B glycoprotein (rhbg), rhodopsin (rho), catechol-O-methyltransferase domain containing protein 1 (comtd1), Epstein-Barr virus-induced protein 3 (ebi3), and insulin (ins). Pathway analysis using DAVID demonstrates changes in the PPAR signaling pathway. Other pathways altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 include drug metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, and tryptophan metabolism signaling pathways. The complete list of pathways most significantly altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment is presented in Table 4. Examples of changes noted in pathways are shown in Supplemental Figs. 5–8. DIRAC analysis (Table 5) demonstrated changes in the calcitonin-like ligand receptor, leptin, trkA, TALL1, and JNK phosphorylation and activation pathways.

Table 4.

Pathways significantly altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment on dpf 7 [144 h of 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment]

| KEGG pathway term | Gene count | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| PPAR signaling pathway | 22 | 2.61E-05 |

| Tryptophan metabolism | 17 | 2.81E-05 |

| Arginine and proline metabolism | 22 | 3.52E-05 |

| Fatty acid metabolism | 15 | 8.11E-05 |

| Glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism | 14 | 1.12E-04 |

| DNA replication | 16 | 1.22E-04 |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | 15 | 3.47E-04 |

| β-Alanine metabolism | 9 | 0.003056 |

| Valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation | 14 | 0.003622 |

| Primary bile acid biosynthesis | 7 | 0.003691 |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 24 | 0.00391 |

| Butanoate metabolism | 11 | 0.004002 |

| Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism | 12 | 0.006128 |

| Fructose and mannose metabolism | 13 | 0.00835 |

| Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | 8 | 0.009276 |

| Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | 17 | 0.010371 |

| Cell cycle | 30 | 0.010998 |

| Starch and sucrose metabolism | 11 | 0.011499 |

| Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis | 6 | 0.028806 |

| Drug metabolism | 8 | 0.029695 |

| Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | 8 | 0.029695 |

| Retinol metabolism | 9 | 0.031453 |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | 10 | 0.032062 |

| Pyruvate metabolism | 11 | 0.037949 |

| Drug metabolism | 10 | 0.038672 |

| Glycerolipid metabolism | 11 | 0.044725 |

Analysis was performed using the DAVID v6.7 program.

Table 5.

Pathways significantly perturbed by 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment on dpf 7 [144 h of 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment]

| Pathway | Database | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Calcitonin-like ligand receptors | Reactome | 4.98E-4 |

| T cytotoxic pathway | Biocarta | 0.001732 |

| Leptin pathway | Biocarta | 0.002419 |

| RNA polymerase III transcription termination | Reactome | 0.004295 |

| Intrinsic pathway | Reactome | 0.004295 |

| Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis keratin sulfate | KEGG | 0.004295 |

| Primary bile acid biosynthesis | KEGG | 0.007948 |

| TrkA receptor | SigmaAldrich | 0.007948 |

Analysis was performed using the DIRAC algorithm.

To assess whether the changes in RNA amounts on d 7 were dependent on the length of exposure to 1α,25(OH)2D3, we treated 6-d-old zebrafish larvae with 1α,25(OH)2D3 or ethanol for 24 h (n = 3). We compared RNA amounts by RNA-seq in vehicle-treated vs. 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated zebrafish, and RNA in 7 d zebrafish treated with 1α,25(OH)2D3 for 6 d with those present after 1 d of treatment. After 1 d (24 h) exposure to 1α,25(OH)2D3 between d 6 and d 7, 427 RNA either increased or decreased. klf11a and klf11b RNA amounts increased 11.8- and 5.4-fold (Supplemental Table 4). These changes are similar to those observed after 6-d exposure to 1α,25(OH)2D3. Likewise, cyp24a1 RNA increased comparably by 6.3-fold. Pathway analysis using DAVID also demonstrates changes in the PPAR signaling pathway among others. The complete list of pathways most significantly altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment is presented in Table 6. However, as shown in Supplemental Table 5, 1146 RNAs at dpf 7 were increased or decreased in zebrafish exposed to 1α,25(OH)2D3 for 6 d (144 h), that were not changed in 7-d-old zebrafish exposed to 1α,25(OH)2D3 for 1 d (24 h). These included RNAs for hsp70 (heat shock protein 70), hsp70l, arrhα (aryl hydrocarbon receptor α), and lepb, which were increased only after prolonged treatment with 1α,25(OH)2D3. Analysis by DIRAC shows that the leptin, calcitonin-like ligand receptor, T-cytotoxic, and antigen-dependent B-cell activation pathways are more profoundly perturbed after prolonged (144 h) 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment than short-term (24 h) treatment (P = 0.0004, 0.0011, 0.0026, and 0.0033, respectively).

Table 6.

Pathways significantly altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment on dpf 7 [24 h of 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment]

| KEGG pathway term | Gene count | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| PPAR signaling pathway | 12 | 7.95E-07 |

| DNA replication | 10 | 1.17E-06 |

| Pyrimidine metabolism | 12 | 7.13E-05 |

| Drug metabolism | 6 | 0.002742 |

| Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | 4 | 0.004794 |

| Cell cycle | 11 | 0.005883 |

| Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | 4 | 0.01559 |

| Base excision repair | 5 | 0.018015 |

| Purine metabolism | 11 | 0.01803 |

| Glutathione metabolism | 5 | 0.02395 |

| Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | 4 | 0.02697 |

| ABC transporters | 4 | 0.04598 |

Analysis was performed using the DAVID v6.7 program. CoA, Coenzyme A.

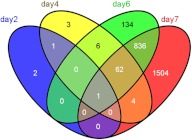

Figure 3 shows the developmental distribution of the genes altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment. Genes are grouped based on their altered expression at single or multiple stages. Differential expression analysis was evaluated between ethanol and 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment on dpf 2, dpf 4, dpf 6, and dpf 7. In total, 2553 mRNA transcripts were differentially expressed in at least one of the four studied developmental stages.

Fig. 3.

Venn diagram showing the developmental distribution of the genes altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment. Genes were grouped based on their altered expression at single or multiple stages. Differential expression analyses were evaluated between ethanol and 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatments on dpf 2, 4, 6, and 7. In total, 2553 mRNA transcripts were differentially expressed in at least one the four studied developmental stages.

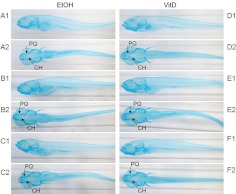

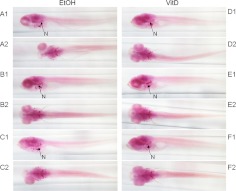

To determine whether treatment with 1α,25(OH)2D3 altered the appearance and size of pharyngeal cartilage, we examined the length of palatoquadrate and ceratohyal cartilages in zebrafish stained with Alcian blue. The size of the palatoquadrate (PQ) cartilage was larger in 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated zebrafish (P = 0.0005) at dpf 7 after 6 d of continuous 1α,25(OH)2D3-treatment (Fig. 4). The ceratohyal (CH) cartilage was increased in length (P = 0.015). Alizarin red staining showed that at this time, calcified skeletal elements were more heavily stained in 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated zebrafish indicating greater calcification. Figure 5 shows more prominent red staining of the notochord (labeled N) and other bones of the developing skull of 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated zebrafish (P = 0.004). Differences in cartilage appearance were not apparent at dpf 4 and dpf 6.

Fig. 4.

Alcian blue-stained, dpf 7 (168 hpf) zebrafish larvae treated with ethanol (vehicle, EtOH) or 1α,25(OH)2D3 (300 pm) continuously for 6 d (144 h). The length of the palatoquadrate (PQ) and ceratohyal (CH) cartilages was assessed in each embryo. The palatoquadrate and ceratohyal cartilages were larger in 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated zebrafish compared with vehicle-treated zebrafish (palatoquadrate P = 0.0005; ceratohyal P = 0.015). A1, B1, and C1 represent ethanol-treated zebrafish, lateral view; A2, B2, and C2 represent ethanol-treated zebrafish, ventral view. D1, E1, and F1 represent 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated, lateral view; D2, E2, and F2 represent 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated, ventral view. VitD, Vitamin D.

Fig. 5.

Alizarin red-stained, dpf 7 (168 hpf) zebrafish larvae treated with ethanol (vehicle, EtOH) or 1α,25(OH)2D3 (300 pm) continuously for 6 d (144 h). The mineralized skeleton appears darker in the 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated zebrafish. n, Notochord. A1, B1, and C1 represent ethanol-treated zebrafish, lateral view; A2, B2, C2 represent ethanol-treated zebrafish, ventral view. D1, E1, and F1 represent 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated, lateral view; D2, E2, and F2 represent 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated, ventral view. VitD, Vitamin D.

Discussion

The VDR is widely and abundantly distributed in rodent and fish embryos/larvae (13–15, 17). We have described the presence of the VDR in mesenchymal tissue of the vertebrae and limb buds (13), kidney (14), and nervous system (dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord) (15) of rat and mouse fetuses as early as 13 d post coitum. Zebrafish express the VDR in substantial amounts at 48 hpf (17). At this time, mineralized bone has not begun to form, although cartilage has just begun to develop. The biological function of the VDR at this stage of development remains unknown. VDR knockout mice do not have overt abnormalities in their morphology and blood chemistry at birth (7, 8, 43) because trans-placental transfer of nutrients, such as calcium, compensate for biological deficits that might occur as a result of VDR deficiency.

To assess the function of the VDR, we used whole transcriptome shotgun sequencing of zebrafish embryo RNAs after treatment of fish with 1α,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle. RNAs and pathways altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 were assessed using bioinformatics tools adapted to assess zebrafish genes and RNA. Several pathways that previously have not been thought to be subject to regulation by 1α,25(OH)2D3 are shown to be dramatically regulated in the zebrafish embryo in vivo. For example, regulation of several RNAs in the PPAR signaling pathway demonstrates that in zebrafish embryos/larvae, 1α,25(OH)2D3 may significantly alter lipid metabolism and the adipocyte differentiation. The early change (at 4 dpf) in RNA for the Kruppel-like 11 transcription factors could play a role in altering fat metabolism in zebrafish because klf11 transcription factors alter chromatin remodeling, brown adipocyte differentiation and uncoupling protein UCP1 and thermogenic gene expression (44, 45). The decrease of RNAs encoding enzymes important in fatty acid oxidation suggests that 1α,25(OH)2D3 decreases fatty acid oxidation. These data are supported by information in the VDR knockout mouse in which energy expenditure is elevated and β-oxidation is increased (46, 47). In VDR knockout mice, leptin concentrations are decreased, whereas in zebrafish treated with 1α,25(OH)2D3 there are dramatic elevations in leptin a and b and leptin receptor RNA. Experiments in cultured human adipocytes (48) have shown that 1α,25(OH)2D3 inhibits uncoupling protein 2 expression. RNAs for enzymes important in bile acid biosynthesis are also affected by 1α,25(OH)2D3.

The regulation of key enzymes involved in the metabolism of various amino acids (e.g. tryptophan, arginine, proline, glycine, serine, and threonine among others) by 1α,25(OH)2D3 is also a previously unrecognized effect of the hormone. As expected, the RNA for the cyp24a1, which encodes the cytochrome P450, cyp24a1, a key part of the 1α,25(OH)2D3-24-hydroxylase that degrades 1α,25(OH)2D3 to 1,24,25-trihydroxyvitamin D3 (49, 50), is consistently increased even at times when the zebrafish embryo is generally unresponsive to 1α,25(OH)2D3. In contrast to the induction of cyp24a1 RNA, the RNAs for a number of other cytochrome P450 involved in xenobiotic metabolism are reduced (cyp1A1, cyp3, cyp3A4, cyp26).

A number of RNAs important in cartilage and bone remodeling are altered by 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment. These include RNAs for IGF and the IGF binding proteins. The effects of 1α,25(OH)2D3 on IGF and its binding proteins are consistent with previous findings regarding the effects of the hormone on these substances (51). The DIRAC algorithm finds several relevant pathways associated with osteoclast development to be perturbed in response to 1α,25(OH)2D3. Both the RANKL pathway and the calcitonin receptor pathway are highly perturbed on dpf 6 in larvae treated with 1α,25(OH)2D3. The RANKL pathway is known to be essential for osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption and to be regulated by 1α,25(OH)2D3 (52). Interestingly, the RANKL pathway is no longer perturbed in dpf 7 larvae, whereas the calcitonin receptor pathway becomes more highly perturbed. Also highly perturbed in dpf 7 is the leptin pathway, which has been linked to bone resorption via the sympathetic nervous system (53, 54).

Changes in RNA expression are associated with changes in cartilage morphology in 1α,25(OH)2D3-treated zebrafish. Cartilage appears to be larger in hormone-treated fish. Additionally, calcification of bone appears to be enhanced. It is possible that changes in IGF and IGF binding proteins induced by 1α,25(OH)2D3 are important in changes observed in cartilage.

In 48 hpf zebrafish, five RNAs are differentially expressed after 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment for a period of 24 h. In contrast, on dpf 7, 24 h of 1α,25(OH)2D3 treatment results in a change in the RNA for 482 genes. Changes in the number and types of RNA present after treatment with 1α,25(OH)2D3 is thus dependent on the stage of zebrafish development. The difference cannot be attributed to a lack of expression of the VDR or its heterodimeric partner, retinoid X receptor-α, both of which are expressed at 48 hpf. Thus, other factors likely play a role in the development of sensitivity to hormone in older zebrafish larvae. Precedents for stage-specific competence to steroid hormones, such as ecdysone, have been noted in Drosophila and Aedes (55–57). The orphan receptor, β FTZ-F1, is responsible for the development of competence to ecdysone in both Drosophila and the mosquito. The factor (or factors) responsible for the development of enhanced RNA response to 1α,25(OH)2D3 in Danio are not known. Transcription factors, such as Kruppel-like factor 11, B-cell CLL/lymphoma 6, forkhead transcription factor, fos and fosB transcription factors, could conceivably play a role because RNA for these factors is consistently increased early after the addition of 1α,25(OH)2D3, and more prolonged exposure results in the increase or decrease in 2407 RNA, representing RNA for approximately 10% of all protein coding genes in Danio. This massive change in gene expression by 1α,25(OH)2D3 has not been documented in developing whole organisms before. Although it is likely that a majority of the change in RNA amounts is due to changes in gene transcription, we cannot be certain that the changes in RNA amounts occur as a result in changes in gene expression. Other mechanisms such as changes in RNA stability may be playing a role as well.

Conclusion

In developing zebrafish embryos/larvae, 1α,25(OH)2D3 dramatically alters RNAs encoding proteins that play a key role in fatty acid, amino acid, and xenobiotic metabolism pathways, and RNAs of transcription factors, leptin, peptide hormones, receptor-activator of NFκB ligand (RANKL), and calcitonin-like ligand receptor pathways. The results demonstrate that 1α,25(OH)2D3 regulates multiple, biologically diverse pathways during development that were not previously recognized as vitamin D targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants (to R.K.) AR-058003 and AR-60869 and a grant from the Marion and Ralph Falk Medical Trust. Additional funding was provided by a National Institutes of Health Howard Temin Pathway to Independence Award in Cancer Research (4R00CA126184), the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg-Institute for Systems Biology consortium, and the Camille-Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar program.

Disclosure Summary: None of the authors have anything to disclose.

NURSA Molecule Pages†:

Nuclear Receptors: VDR;

Ligands: 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3.

Annotations provided by Nuclear Receptor Signaling Atlas (NURSA) Bioinformatics Resource. Molecule Pages can be accessed on the NURSA website at www.nursa.org.

- ChIP

- Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DAVID

- Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery

- DIRAC

- Differential Rank Conservation

- DPBS

- Dulbecco's PBS

- dpf

- days post fertilization

- hpf

- hours post fertilization

- ID

- identification

- IPA

- Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- KEGG

- Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- 1α,25(OH)2D3

- 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- QPCR

- quantitative PCR

- RANKL

- receptor-activator of NFκB ligand

- RNA-seq

- whole transcriptome shotgun sequencing

- VDR

- vitamin D receptor.

References

- 1. DeLuca HF. 2004. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr 80:1689S–1696S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumar R. 1991. Vitamin D and calcium transport. Kidney Int 40:1177–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haussler MR, Haussler CA, Bartik L, Whitfield GK, Hsieh JC, Slater S, Jurutka PW. 2008. Vitamin D receptor: molecular signaling and actions of nutritional ligands in disease prevention. Nutr Rev 66:S98–S112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cai Q, Chandler JS, Wasserman RH, Kumar R, Penniston JT. 1993. Vitamin D and adaptation to dietary calcium and phosphate deficiencies increase intestinal plasma membrane calcium pump gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:1345–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wasserman RH, Smith CA, Brindak ME, De Talamoni N, Fullmer CS, Penniston JT, Kumar R. 1992. Vitamin D and mineral deficiencies increase the plasma membrane calcium pump of chicken intestine. Gastroenterology 102:886–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christakos S, Dhawan P, Porta A, Mady LJ, Seth T. 2011. Vitamin D and intestinal calcium absorption. Mol Cell Endocrinol 347:25–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li YC, Pirro AE, Amling M, Delling G, Baron R, Bronson R, Demay MB. 1997. Targeted ablation of the vitamin D receptor: an animal model of vitamin D-dependent rickets type II with alopecia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:9831–9835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoshizawa T, Handa Y, Uematsu Y, Takeda S, Sekine K, Yoshihara Y, Kawakami T, Arioka K, Sato H, Uchiyama Y, Masushige S, Fukamizu A, Matsumoto T, Kato S. 1997. Mice lacking the vitamin D receptor exhibit impaired bone formation, uterine hypoplasia and growth retardation after weaning. Nat Genet 16:391–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson JA, Grande JP, Roche PC, Campbell RJ, Kumar R. 1995. Immuno-localization of the calcitriol receptor, calbindin-D28k and the plasma membrane calcium pump in the human eye. Curr Eye Res 14:101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johnson JA, Grande JP, Roche PC, Campbell RJ, Kumar R. 1995. Immunolocalization of calcitriol receptor, plasma membrane calcium pump and calbindin-D28k in the cornea and ciliary body of the rat eye. Ophthalmic Res 27:42–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johnson JA, Grande JP, Roche PC, Kumar R. 1994. Immunohistochemical localization of the 1,25(OH)2D3 receptor and calbindin D28k in human and rat pancreas. Am J Physiol 267:E356–E360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson JA, Grande JP, Roche PC, Kumar R. 1996. Immunohistochemical detection and distribution of the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor in rat reproductive tissues. Histochem Cell Biol 105:7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson JA, Grande JP, Roche PC, Kumar R. 1996. Ontogeny of the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor in fetal rat bone. J Bone Miner Res 11:56–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson JA, Grande JP, Roche PC, Sweeney WE, Jr, Avner ED, Kumar R. 1995. 1α, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor ontogenesis in fetal renal development. Am J Physiol 269:F419–F428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johnson JA, Grande JP, Windebank AJ, Kumar R. 1996. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors in developing dorsal root ganglia of fetal rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 92:120–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prüfer K, Veenstra TD, Jirikowski GF, Kumar R. 1999. Distribution of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor immunoreactivity in the rat brain and spinal cord. J Chem Neuroanat 16:135–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Craig TA, Sommer S, Sussman CR, Grande JP, Kumar R. 2008. Expression and regulation of the vitamin D receptor in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. J Bone Miner Res 23:1486–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramagopalan SV, Heger A, Berlanga AJ, Maugeri NJ, Lincoln MR, Burrell A, Handunnetthi L, Handel AE, Disanto G, Orton SM, Watson CT, Morahan JM, Giovannoni G, Ponting CP, Ebers GC, Knight JC. 2010. A ChIP-seq defined genome-wide map of vitamin D receptor binding: associations with disease and evolution. Genome Res 20:1352–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heikkinen S, Väisänen S, Pehkonen P, Seuter S, Benes V, Carlberg C. 2011. Nuclear hormone 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 elicits a genome-wide shift in the locations of VDR chromatin occupancy. Nucleic Acids Res 39:9181–9193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carlberg C, Seuter S, Heikkinen S. 2012. The first genome-wide view of vitamin D receptor locations and their mechanistic implications. Anticancer Res 32:271–282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fleming A, Sato M, Goldsmith P. 2005. High-throughput in vivo screening for bone anabolic compounds with zebrafish. J Biomol Screen 10:823–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. 1995. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn 203:253–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schilling TF, Kimmel CB. 1997. Musculoskeletal patterning in the pharyngeal segments of the zebrafish embryo. Development 124:2945–2960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Westerfield M. 2000. The zebrafish book. A guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Danio rerio). 4th ed Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press [Google Scholar]

- 25. Netzel BC, Cradic KW, Bro ET, Girtman AB, Cyr RC, Singh RJ, Grebe SK. 2011. Increasing liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry throughput by mass tagging: a sample-multiplexed high-throughput assay for 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3. Clin Chem 57:431–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Strathmann FG, Laha TJ, Hoofnagle AN. 2011. Quantification of 1α,25-dihydroxy vitamin D by immunoextraction and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem 57:1279–1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Walker MB, Kimmel CB. 2007. A two-color acid-free cartilage and bone stain for zebrafish larvae. Biotech Histochem 82:23–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. 2002. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res 12:996–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Anders S, Huber W. 2010. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol 11:R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. 2009. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4:44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huang da W, Sherman BT, Zheng X, Yang J, Imamichi T, Stephens R, Lempicki RA. 2009. Extracting biological meaning from large gene lists with DAVID. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ: Curr Protoc Bioinformatics Chapter 13:Unit 13 11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eddy JA, Geman D, Price ND. 2009. Relative expression analysis for identifying perturbed pathways. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2009:5456–5459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eddy JA, Hood L, Price ND, Geman D. 2010. Identifying tightly regulated and variably expressed networks by Differential Rank Conservation (DIRAC). PLoS Comput Biol 6:e1000792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kanehisa M, Araki M, Goto S, Hattori M, Hirakawa M, Itoh M, Katayama T, Kawashima S, Okuda S, Tokimatsu T, Yamanishi Y. 2008. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res 36:D480–D484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kanehisa M, Goto S, Kawashima S, Okuno Y, Hattori M. 2004. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res 32:D277–D280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okuda S, Yamada T, Hamajima M, Itoh M, Katayama T, Bork P, Goto S, Kanehisa M. 2008. KEGG Atlas mapping for global analysis of metabolic pathways. Nucleic Acids Res 36:W423–W426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mi H, Guo N, Kejariwal A, Thomas PD. 2007. PANTHER version 6: protein sequence and function evolution data with expanded representation of biological pathways. Nucleic Acids Res 35:D247–D252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Joshi-Tope G, Gillespie M, Vastrik I, D'Eustachio P, Schmidt E, de Bono B, Jassal B, Gopinath GR, Wu GR, Matthews L, Lewis S, Birney E, Stein L. 2005. Reactome: a knowledgebase of biological pathways. Nucleic Acids Res 33:D428–D432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. 2008. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods 5:621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Avioli LV, Sonn Y, Jo D, Nahn TH, Haussler MR, Chandler JS. 1981. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D in male, nonspawning female, and spawning female trout. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 166:291–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Larsson D, Nemere I, Aksnes L, Sundell K. 2003. Environmental salinity regulates receptor expression, cellular effects, and circulating levels of two antagonizing hormones, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, in rainbow trout. Endocrinology 144:559–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Van Cromphaut SJ, Dewerchin M, Hoenderop JG, Stockmans I, Van Herck E, Kato S, Bindels RJ, Collen D, Carmeliet P, Bouillon R, Carmeliet G. 2001. Duodenal calcium absorption in vitamin D receptor-knockout mice: functional and molecular aspects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:13324–13329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Seo S, Lomberk G, Mathison A, Buttar N, Podratz J, Calvo E, Iovanna J, Brimijoin S, Windebank A, Urrutia R. 2012. Kruppel-Like factor 11 differentially couples to histone acetyltransferase and histone methyltransferase chromatin remodeling pathways to transcriptionally regulate the dopamine D2 receptor in neuronal cells. J Biol Chem 287:12723–12735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yamamoto K, Sakaguchi M, Medina RJ, Niida A, Sakaguchi Y, Miyazaki M, Kataoka K, Huh NH. 2010. Transcriptional regulation of a brown adipocyte-specific gene, UCP1, by KLF11 and KLF15. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 400:175–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Narvaez CJ, Matthews D, Broun E, Chan M, Welsh J. 2009. Lean phenotype and resistance to diet-induced obesity in vitamin D receptor knockout mice correlates with induction of uncoupling protein-1 in white adipose tissue. Endocrinology 150:651–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wong KE, Szeto FL, Zhang W, Ye H, Kong J, Zhang Z, Sun XJ, Li YC. 2009. Involvement of the vitamin D receptor in energy metabolism: regulation of uncoupling proteins. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296:E820–E828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shi H, Norman AW, Okamura WH, Sen A, Zemel MB. 2002. 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits uncoupling protein 2 expression in human adipocytes. FASEB J 16:1808–1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Holick MF, Kleiner-Bossaller A, Schnoes HK, Kasten PM, Boyle IT, DeLuca HF. 1973. 1,24,25-Trihydroxyvitamin D3. A metabolite of vitamin D3 effective on intestine. J Biol Chem 248:6691–6696 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kumar R, Schnoes HK, DeLuca HF. 1978. Rat intestinal 25- hydroxyvitamin D3- and 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase. J Biol Chem 253:3804–3809 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Scharla SH, Strong DD, Mohan S, Baylink DJ, Linkhart TA. 1991. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 differentially regulates the production of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and IGF-binding protein-4 in mouse osteoblasts. Endocrinology 129:3139–3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Suda T, Nakamura I, Jimi E, Takahashi N. 1997. Regulation of osteoclast function. J Bone Miner Res 12:869–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ducy P, Amling M, Takeda S, Priemel M, Schilling AF, Beil FT, Shen J, Vinson C, Rueger JM, Karsenty G. 2000. Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: a central control of bone mass. Cell 100:197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Takeda S, Elefteriou F, Karsenty G. 2003. Common endocrine control of body weight, reproduction, and bone mass. Annu Rev Nutr 23:403–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Woodard CT, Baehrecke EH, Thummel CS. 1994. A molecular mechanism for the stage specificity of the Drosophila prepupal genetic response to ecdysone. Cell 79:607–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Thummel CS. 1996. Flies on steroids–Drosophila metamorphosis and the mechanisms of steroid hormone action. Trends Genet 12:306–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li C, Kapitskaya MZ, Zhu J, Miura K, Segraves W, Raikhel AS. 2000. Conserved molecular mechanism for the stage specificity of the mosquito vitellogenic response to ecdysone. Dev Biol 224:96–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.