Abstract

Epidemiological and interventional studies of humans have revealed a close association between periodontal diseases and preterm delivery of low-birth-weight infants. Porphyromonas gingivalis, a periodontal pathogen, can translocate to gestational tissues following oral-hematogenous spread. We previously reported that P. gingivalis invades extravillous trophoblast cells (HTR-8) derived from the human placenta and inhibits proliferation through induction of arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. The purpose of the present study was to identify signaling pathways mediating cellular impairment caused by P. gingivalis. Following P. gingivalis infection, the expression of Fas was induced and p53 accumulated, responses consistent with response to DNA damage. Ataxia telangiectasia- and Rad3-related kinase (ATR), an essential regulator of DNA damage checkpoints, was shown to be activated together with its downstream signaling molecule Chk2, while the p53 degradation-related protein MDM2 was not induced. The inhibition of ATR prevented both G1 arrest and apoptosis caused by P. gingivalis in HTR-8 cells. In addition, small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of p53 abrogated both G1 arrest and apoptosis. The regulation of apoptosis was associated with Ets1 activation. HTR-8 cells infected with P. gingivalis exhibited activation of Ets1, and knockdown of Ets1 with siRNA diminished both G1 arrest and apoptosis. These results suggest that P. gingivalis activates cellular DNA damage signaling pathways that lead to G1 arrest and apoptosis in trophoblasts.

INTRODUCTION

Preterm birth is defined as delivery before 37 weeks of gestation (15) and generally results in low-birth-weight infants. There are various risk factors for preterm delivery of low-birth-weight infants (PTLBW), many of which involve increased systemic inflammation (5, 16). Bacterial infection is one of the major causes of PTLBW, either ascending from the urogenital tract or occurring transplacentally following bacteremia. Up to 80% of preterm deliveries at less than 30 weeks of gestation have possible infection, and these infections usually precede the development of pregnancy complications. The pathogenesis can result directly from bacterial invasion of fetoplacental tissue, causing tissue damage and expulsion of the infected fetus. Alternatively, adverse outcomes can result from infection-induced disruption of normal immune and inflammatory status (5, 15, 43).

Various epidemiological studies have shown a link between periodontal diseases and PTLBW (59). Porphyromonas gingivalis, a major periodontal pathogen, was detected in the amniotic fluid of pregnant women with a diagnosis of threatened premature labor (30) as well as in placentas of those with preeclampsia (4). In addition, P. gingivalis antigens were detected in placental tissues, including syncytiotrophoblasts, chorionic trophoblasts, decidual cells, and amniotic epithelial cells, as well as vascular cells, which were obtained from women with chorioamnionitis at fewer than 37 weeks of gestation (25). In rodent and rabbit animal models, P. gingivalis was also found to invade both maternal and fetal tissues and result in chorioamnionitis and placentitis. Moreover, P. gingivalis was found to achieve transplacental passage in animal models (6, 10, 32). In vitro studies showed that P. gingivalis invaded placental trophoblasts and induced G1 arrest and apoptosis through pathways involving extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and signaling through cyclins and retinoblastoma protein (21). In addition, invasion by P. gingivalis induced MEK-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways and modulated cytokine expression by trophoblast cell lines (44).

Cell cycle arrest and apoptosis are known to be triggered by DNA damage (45), following which DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and single-strand breaks (SSBs) induce the activation of ataxia telangiectasia- and Rad3-related proteins (ATR), as well as ataxia telangiectasia-mutated kinases (ATM) (12, 45). ATM and ATR share many biochemical and functional similarities, including sequence homology, phosphorylation sites, and downstream targets (12, 45). The overlap between the target sets includes substrates that promote cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, and apoptosis via p53. Moreover, most substrates, such as checkpoint kinases (Chk1 and Chk2) and p53, are phosphorylated by both kinases (12, 45). However, ATR is essential for the viability of replicating human and mouse cells, whereas ATM is not. ATM functions distinctively in response to rare occurrences of DSBs (12). Viral infection can affect the activation of ATR and/or ATM. ATR activated by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (46) and ATM by herpes simplex virus and human cytomegalovirus (33, 52). Both kinases have been reported to be activated in cells infected with Epstein-Barr virus, human polyomavirus JC virus, and minute virus of canines (11, 33, 34, 40). DNA damage-dependent signaling is reported less frequently following bacterial infection. However, Helicobacter pylori can induce DSBs in epithelial and mesenchymal cells, and the resulting DNA discontinuities trigger a damage-signaling and repair response involving the ATM-dependent recruitment of repair factors, such as p53-binding protein (53BP1) and mediator of DNA damage checkpoint protein 1 (MDC1), and histone H2A variant X (H2AX) phosphorylation (56).

The mechanisms by which P. gingivalis induces G1 arrest and apoptosis in trophoblasts are not fully understood. In this study, we report that invasive P. gingivalis activates ERK1/2-Ets1 and the cellular DNA damage signaling pathways that act through an ATR/Chk2/p53-dependent pathway to cause G1 arrest and apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial and cell cultures.

The bacterial strains used were P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 and related mutants, including a long fimbria-null (fimA) mutant (KDP150) (53) and Rgp- and Kgp-null (rgpA rgpB kgp-deficient) triple mutant (KDP136) (51). Bacterial cells were grown in Trypticase soy broth supplemented with yeast extract (1 mg/ml), menadione (1 μg/ml), and hemin (5 μg/ml), as described previously (21). KDP136 was fimbriated as described previously (24). Briefly, the supernatant from fimbria-null KDP150 culture was filtrated through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter (Asahi Glass Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and membrane vesicle-depleted supernatants (VDS) containing soluble gingipains were obtained by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 50 min. The gingipain-null mutant (KDP136) was inoculated into fresh culture medium containing 30% VDS. The HTR-8/SVneo trophoblast cell line was provided by Charles Graham (Kingston, Ontario, Canada). HTR-8 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Bacterial adhesion and invasion.

HTR-8 cells were infected with bacteria at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 or 200 for 2 h and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For total adhesion and invasion levels, cells were lysed with sterile distilled water for 15 min, and dilutions of the lysate plated and cultured anaerobically for CFU on blood agar supplemented with hemin and menadione. For invasion assay, extracellular bacteria were killed with metronidazole (200 μg/ml) and gentamicin (300 μg/ml) for 1 h (27). Cells were lysed, and the CFU of invasive organisms were enumerated. Invasion was calculated from CFU recovered intracellularly as a percentage of total bacteria inoculated.

Western immunoblotting.

HTR-8 cells were solubilized in cell lysis and extraction reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) containing a protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and gingipain-specific inhibitors (KYT-1 and KYT-36; Peptide Institute, Osaka, Japan). Immunoblotting was performed as previously described (21). Blots were probed at 4°C overnight with the following primary antibodies: anti-Fas, 1:1,000; anti-p53, 1:1,000; anti-phospho-ATR (Ser428), 1:1,000; anti-ATR, 1:1,000; anti-phospho-ATM (Ser1981), 1:1,000; anti-phospho-Chk1, 1:1,000; anti-phospho-Chk2, 1:1,000; anti-phospho-p53 (Ser15), 1:1,000; anti-phospho-p53 (Ser20), 1:1,000; anti-phospho-MDM2 (Ser166), 1:1,000; anti-phospho-ERK1/2, 1:1,000; anti-ERK1/2, 1:1,000; anti-p16, 1:1,000; anti-p21, 1:1,000 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); anti-ATM, 1:1,000 (Signalway Antibody, Pearland, TX); anti-Chk1, 1:1,000; anti-Chk-2, 1:1,000 (EnoGene, New York, NY); anti-Ets1, 1:500; anti-Ets2, 1:500 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); and anti-MDM2, 1:1,000 (NOVUS Biologicals, Littleton, CO). Proteins and phosphorylated proteins were detected using the Pierce ECL substrate (Thermo Scientific). Blots were stripped and probed with anti-β-actin antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) as a loading control. Densitometric analysis of bands was performed using ImageJ software.

RNA interference.

The following stealth small interfering RNA (siRNA) duplexes were purchased from Sigma Genosys: human Ets1, 5′-GGAGAUGGCUGGGAAUUCAAACUUU-3′ (22) and 5′-GCUGACCUCAAUAAGGACA-3′ (54); human p53, 5′-GCAUGAACCGGAGGCCCAUTT-3′ (50) and 5′-CUACUUCCUGAAAACAACGTT-3′ (49); and control siRNA, 5′-CAUGUCAUGUGUCACAUCUCTT-3′. The siRNAs were introduced into HTR-8 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 24 h of transfection, the medium was replaced, and cells were incubated for a further 24 h prior to challenge with P. gingivalis.

Flow cytometry. (i) Cell cycle analysis.

Infected or control HTR-8 cells were trypsinized, washed with cold PBS, and then fixed in 70% ethanol at −20°C overnight. Ethanol-fixed cells were washed with PBS and incubated in 1 ml of 0.1 mg/ml RNase A solution at 37°C for 30 min. The cells were stained with 50 mg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell cycle analysis of 30,000 cells per sample was carried out with excitation at 488 nm in a flow cytometer (FACScan; Becton, Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Data were analyzed with Cell-Quest software (BD Biosciences) and ModFit LT 3.0 (Verity Software, La Jolla, CA).

(ii) Apoptosis.

For annexin V staining, cells were harvested and stained with an annexin V-FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate) apoptosis detection kit (BioVision, Palo Alto, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and flow-cytometric analysis was performed. Chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. ATM/ATR inhibitor (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany), 2.5 μg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), was preincubated with HTR-8 cells for 2 h prior to addition of bacteria.

Caspase 3 activity.

Caspase 3 activity was measured using a caspase 3/CPP32 colorimetric assay kit (BioVision, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions on a microplate reader at 405 nm (Bio-Rad model 680).

RESULTS

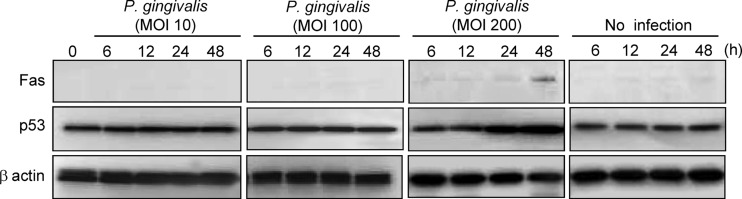

P. gingivalis infection induces a cellular DNA damage response.

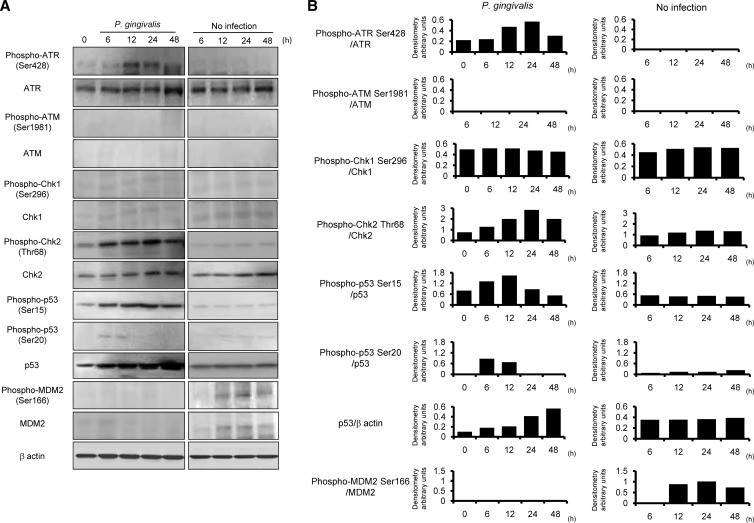

Fas (CD95) is a death domain containing a receptor that activates the extrinsic apoptotic pathway (7). p53 is involved in mediating key cellular processes, such as DNA repair, cell cycle arrest, senescence, and apoptosis (58). We first examined the effect of P. gingivalis on expression of Fas and p53 by HTR-8/SVneo trophoblasts (referred to here as HTR-8 cells). Following P. gingivalis infection at an MOI of 200, Fas expression was induced at 48 h, and the accumulation of p53 also reached its peak at 48 h (Fig. 1), while P. gingivalis triggered no induction of Fas expression at MOIs of 10 and 100. Indeed, G1 cell arrest and apoptosis were not observed following P. gingivalis infection at MOIs of 10 and 100, a result which has also been observed at an MOI of 200 (21). p53 accumulates in response to DNA damage, and the resulting increase of p53 function induces either cell growth arrest or apoptosis (5, 31). Therefore, we next examined the activation status of DNA damage response proteins up to 48 h after infection in HTR-8 cells (Fig. 2). ATR and ATM, which activate downstream signaling molecules such as Chk1, Chk2, and p53, are essential regulators of DNA damage checkpoints in mammalian cells (45). Levels of the Ser428-phosphorylated form of ATR and the total amount of ATR were increased by P. gingivalis from 12 to 48 h after infection (Fig. 2). On the other hand, phosphorylation of ATM (Ser1981) and expression of total ATM were not observed. In the presence of DSBs, activated ATR is known to phosphorylate on Chk2, and Ser15 and Ser20 phosphorylate on p53 (20, 23, 41). Furthermore, ATR can also activate Chk1, which indirectly phosphorylates p53 at Ser20 (63). P. gingivalis was found to induce Thr68 phosphorylation of Chk2 (Thr68) and p53 (Ser15), whereas Chk1 (Ser296) and p53 (Ser20) did not show an increase in phosphorylation levels. MDM2 possesses the E3 ubiquitin ligase and binds to the p53 N-terminal transcriptional activation domain, leading to degradation of p53 via the 26S proteasome (36). Neither total nor phosphorylated MDM2 was increased in P. gingivalis-infected cells. These results indicate that p53 accumulated in response to damage by P. gingivalis via the ATR-Chk2 pathway and by the lack of induction of MDM2.

Fig 1.

Fas and p53 expression is upregulated in HTR-8 cells infected with P. gingivalis. HTR-8 cells were infected with P. gingivalis at MOIs of 10, 100, and 200 for the indicated times. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with Fas and total p53 antibodies. β-Actin was included as a loading control. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Fig 2.

Activation of DNA damage-responsive proteins in HTR-8 cells infected with P. gingivalis. (A) HTR-8 cells were infected with P. gingivalis at an MOI of 200 for the indicated times. Lysates of infected and noninfected cells were immunoblotted with antibodies to DNA damage-responsive proteins. (B) Densitometric analysis of blots showing the phosphorylation and total proteins, expressed in arbitrary units. β-Actin was included as a loading control. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

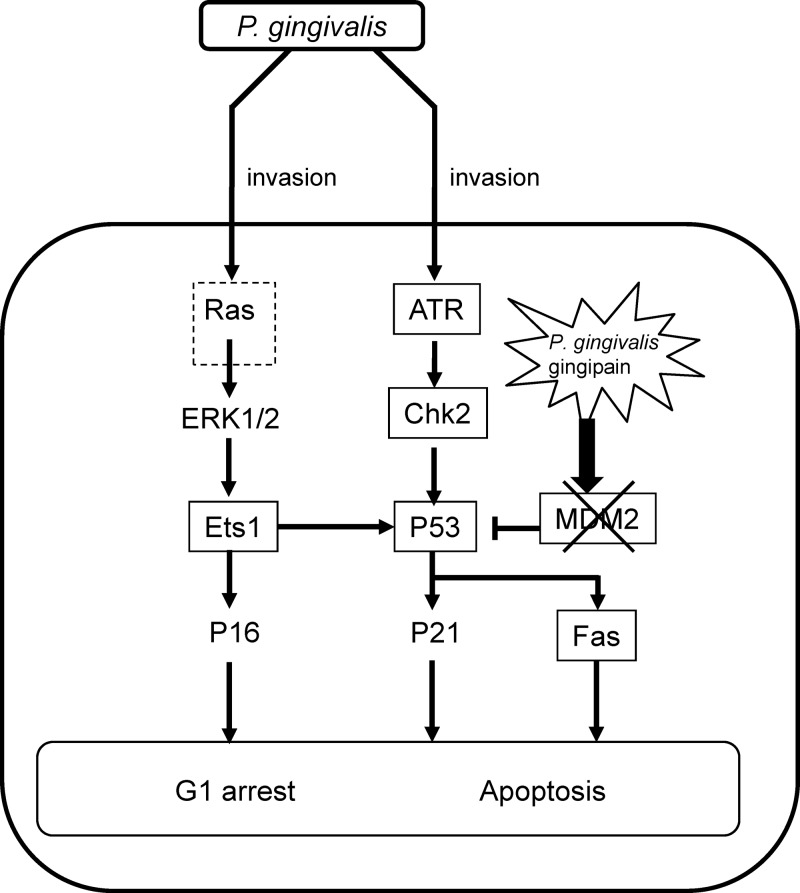

ATR is associated with P. gingivalis-mediated G1 arrest and apoptosis.

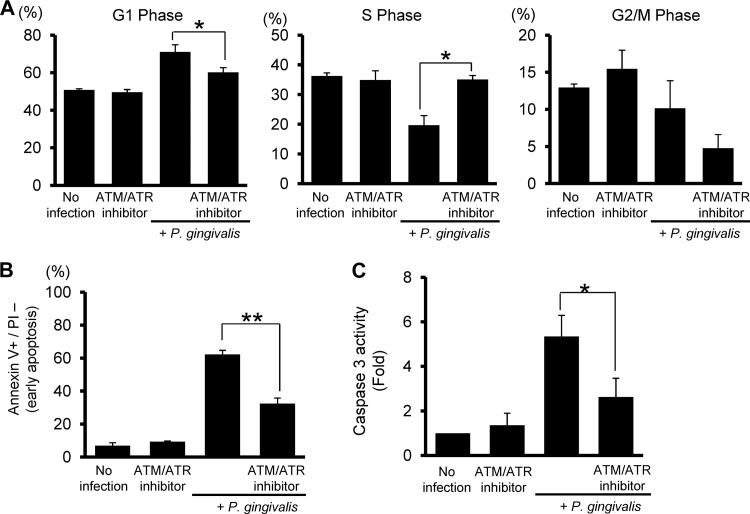

DNA damage response is a signal transduction pathway that coordinates cell cycle transitions and apoptosis (12). Therefore, we investigated whether ATR functions in the cell cycle transition and apoptosis responses of HTR-8 cells to P. gingivalis. Pretreatment with the ATM/ATR inhibitor prevented G1 arrest by P. gingivalis in HTR-8 cells (Fig. 3A). In addition, ATR inhibition abrogated the induction of apoptosis (Fig. 3B) and caspase 3 activity (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that G1 arrest and apoptosis by P. gingivalis in HTR-8 cells are regulated by the ATR-Chk2 pathway.

Fig 3.

Effects of an ATM and ATR inhibitor on G1 arrest and apoptosis. HTR-8 cells were infected with P. gingivalis at an MOI of 200 for 48 h. An inhibitor was added for 2 h prior to infection. (A) DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry, and cell cycle profiles were obtained with ModFit software. Results are means ± standard deviations (SD) of cell cycle distribution from three independent experiments with flow cytometry parameters set to exclude cell debris and aggregates. *, P < 0.05 compared with infected cells without inhibitor (t test). (B) Cells were stained with annexin V and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. Mean percentage ± SD of apoptotic (annexin V+/PI−) cells. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3). *, P < 0.01 compared with infected cells without inhibitor. (C) Cells were treated with inhibitor were infected with P. gingivalis for 48 h as described for panel B, and caspase 3 activity was measured. Fold changes were calculated relative to infected cells without inhibitor (t test). * and **, P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 (Student's t test) compared with P. gingivalis-infected cells with inhibitor.

Activation of p53 by P. gingivalis controls G1 arrest and apoptosis.

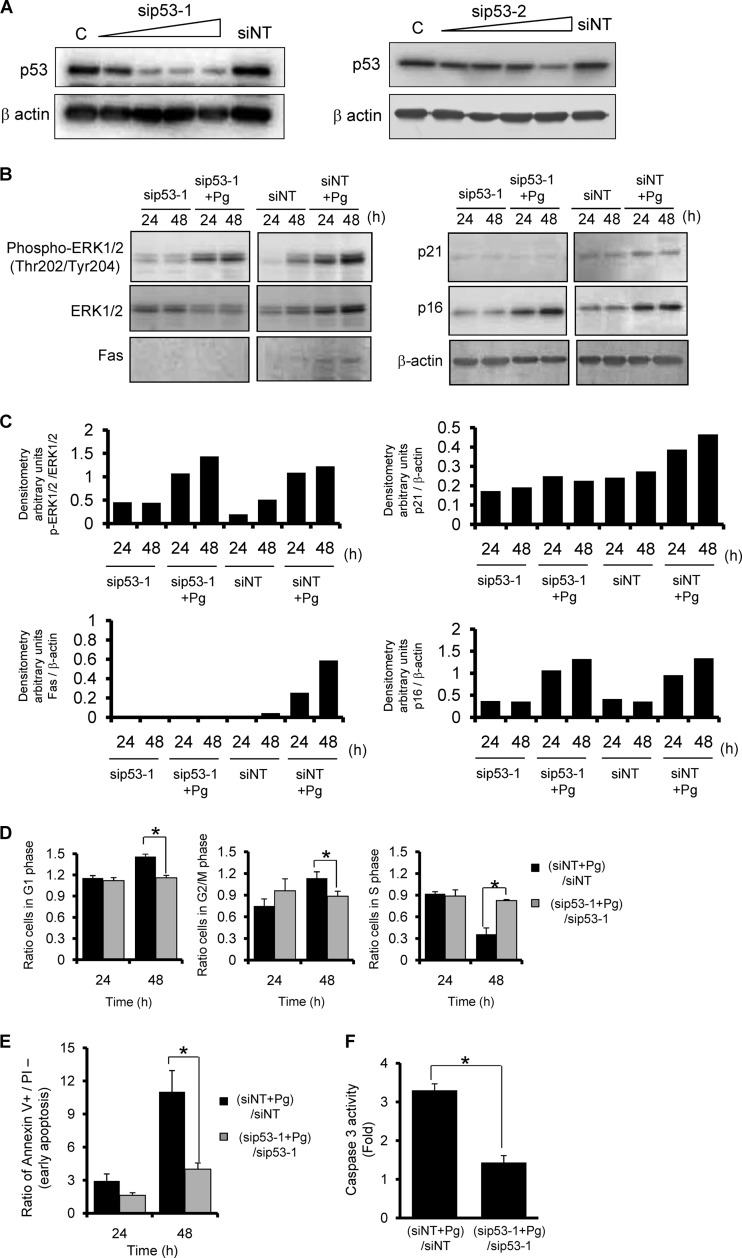

To evaluate the effects of p53 activation on cell cycle arrest and apoptosis caused by P. gingivalis, we silenced p53 expression using two siRNA duplexes. Expression of p53 was significantly reduced in the knockdown cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). At 48 h after transfection, p53 knockdown HTR-8 cells were infected with P. gingivalis and then assayed immediately (time zero) and at 24 and 48 h after bacterial infection. In cells transfected with the nontarget siRNA, P. gingivalis infection enhanced the expressions of all signaling molecules tested at 24 and 48 h. Conversely, no induction of p21 or Fas was observed in the p53 knockdown cells (Fig. 4B and C). p53 activation reportedly increases Fas expression at the cell surface by transport from the Golgi complex (7). Thus, Fas induction by P. gingivalis can be considered due to the p53-dependent response to DNA damage. In addition, G1 arrest that is dependent on p53 requires p21 activation (61). Following infection with P. gingivalis, the induction of p21 was suppressed by p53 knockdown (Fig. 4B and C). Moreover, G1 arrest was negligible, and the cell cycle accurately progressed to S phase in the p53 knockdown cells infected with the pathogen (Fig. 4D). Additionally, p53 knockdown abrogated the induction of apoptosis (Fig. 4E) and caspase 3 activity (Fig. 4F). To avoid elicitation of off-targeting, a second siRNA specific to another sequence was provided in the same target mRNA. Figure S1 in the supplemental material shows that cells with alternative p53 siRNA silencing also showed significantly reduced arrest in G1 phase and progressed into S phase, as well as showing resistance to the apoptotic effect of P. gingivalis. These results suggest that P. gingivalis diverts p53 signaling events, which causes cell cycle disturbance and ultimately apoptosis.

Fig 4.

siRNA knockdown of p53 suppresses P. gingivalis-mediated G1 arrest and apoptosis. HTR-8 cells were transfected with siRNA for p53 (sip53-1 and -2) or with a nontarget control (siNT). (A) Cells were lysed and immunoblotted with anti-p53 or β-actin antibodies at 48 h after transfection. (B) siRNA knockdown cells were infected with P. gingivalis at an MOI of 200 for 24 or 48 h. Expression profiles of signaling molecules were examined by immunoblotting. β-Actin was included as a loading control. (C) Densitometric analysis of blots showing the phosphorylation and total proteins, expressed in arbitrary units. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) siRNA knockdown cells were infected with P. gingivalis as described for panel B, and then cell cycle distribution was determined using flow cytometry. The ratio of cells in each cell cycle phase is expressed relative to that of noninfected controls. (E) siRNA knockdown cells were infected as described for panel B, followed by staining with annexin V and propidium iodide (PI), and analyzed by flow cytometry. Fold change was calculated as described for panel C. (F) siRNA knockdown cells were infected with P. gingivalis for 48 h as described for panel D, and then caspase 3 activity was measured. The fold change was calculated as described for panel D. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). *, P < 0.01 (Student's t test) compared with the ratio of P. gingivalis-infected NT-siRNA control to NT-siRNA control.

Activation of Ets1 by P. gingivalis controls G1 arrest and apoptosis.

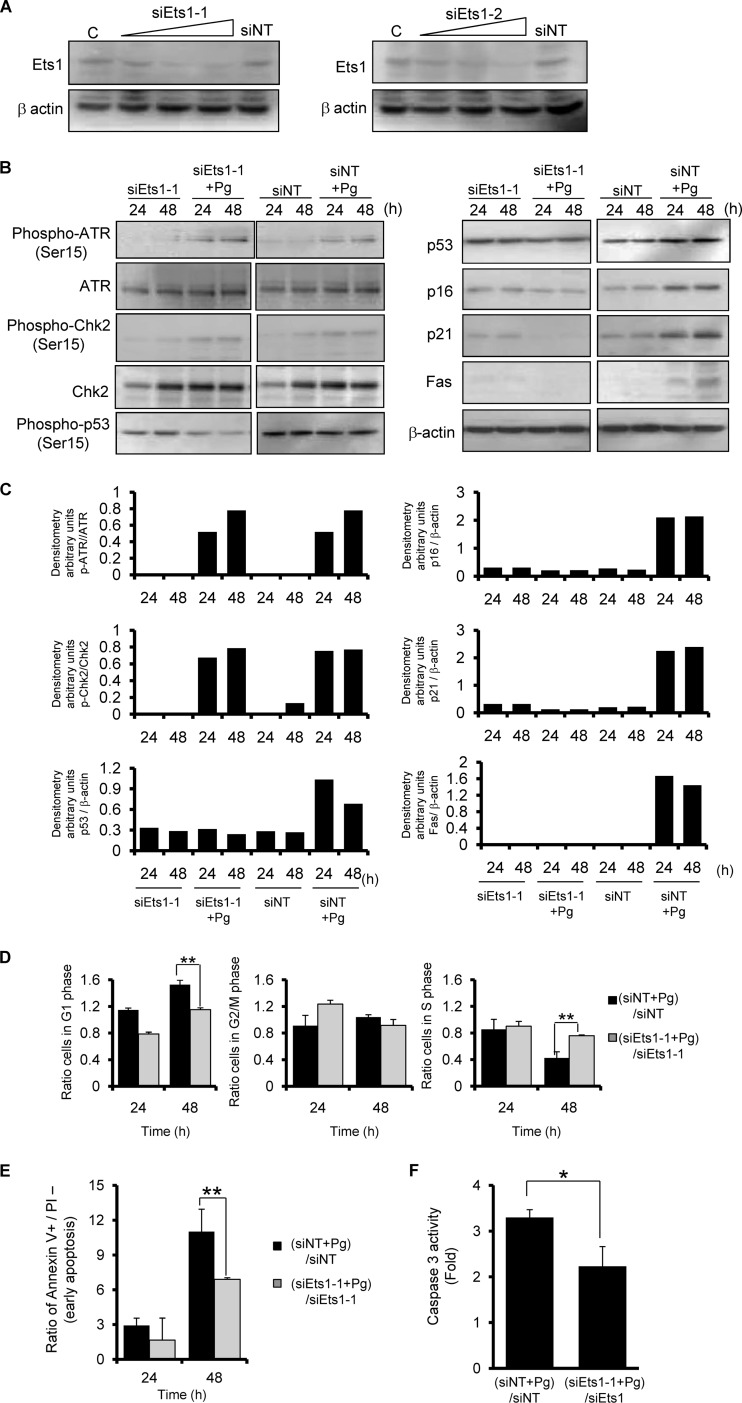

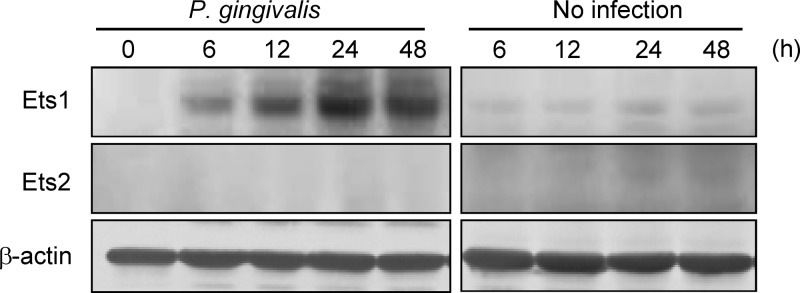

P. gingivalis was previously shown to elevate the levels of p16 in HTR-8 cells (21), and p53 knockdown did not suppress p16 induction by the organisms (Fig. 4B). Upregulation of p16 is mediated by Ets1 and Ets2 proteins through the proximal Ets-binding site in the p16 promoter (19). Thus, we next examined the effect of P. gingivalis on Ets1 and Ets2 levels. Infection of HTR-8 cells with P. gingivalis resulted in a significant increase in Ets1 levels compared to noninfected cells, whereas little expression of Ets2 was observed in infected or control cells (Fig. 5). Ets1 also induces the expression of apoptotic genes, and p16 mediates cell cycle arrest at G1 (19, 39). In addition, p21 is controlled by the expression of p16 in hepatoma cells (19). To evaluate the role of Ets1 activation in P. gingivalis-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, we silenced Ets1 expression by using two sets of siRNA duplexes (Fig. 6A). Both siRNA constructs reduced expression of Ets1 at the transcriptional level. Immunoblotting showed that the levels of p53, p16, p21, and Fas were decreased in Ets1 knockdown cells following P. gingivalis infection. In contrast, the phosphorylation of ATR and Chk2 was not affected by Ets1 knockdown (Fig. 6B and C). Moreover, knockdown of Ets1 significantly suppressed G1 cycle arrest (Fig. 6D) and diminished the ability of P. gingivalis to induce apoptosis and increased the activity of caspase 3 at 48 h (Fig. 6E and F). The use of other Ets1 siRNA sequences resulted in the same effects on cell cycle and apoptosis (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Fig 5.

Ets1 expression is upregulated in HTR-8 cells infected with P. gingivalis. HTR-8 cells were infected with P. gingivalis at an MOI of 200 for the indicated times. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-Ets1 or Ets2 antibodies. β-Actin was included as a loading control. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Fig 6.

siRNA knockdown of Ets1 suppresses P. gingivalis-mediated G1 arrest and apoptosis. HTR-8 cells were transfected with siRNA for Ets1 (sipEts1-1 and -2) or with a nontarget control (siNT). (A) Immunoblot with anti-Ets1 or β-actin antibodies at 48 h after transfection and with β-actin as a loading control. (B) siRNA knockdown cells were infected with P. gingivalis at an MOI of 200 for 24 and 48 h. Expression profiles of signaling molecules were examined by immunoblotting. β-Actin was included as a loading control. (C) Densitometric analysis of blots of phosphorylated and total proteins, expressed in arbitrary units. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) siRNA knockdown cells were infected with P. gingivalis as described for panel B, and the cell cycle distribution was determined using flow cytometry. (E) siRNA knockdown cells were infected as described for panel B, followed by staining with annexin V and propidium iodide (PI), and analyzed using flow cytometry. (F) siRNA knockdown cells were infected with P. gingivalis for 48 h as described for panel B, and caspase 3 activity was measured. Fold changes were calculated as described for panel D. Error bars indicate standard deviations (n = 3). * and **, P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 (Student's t test) compared with the ratio of P. gingivalis-infected NT-siRNA control to NT-siRNA control.

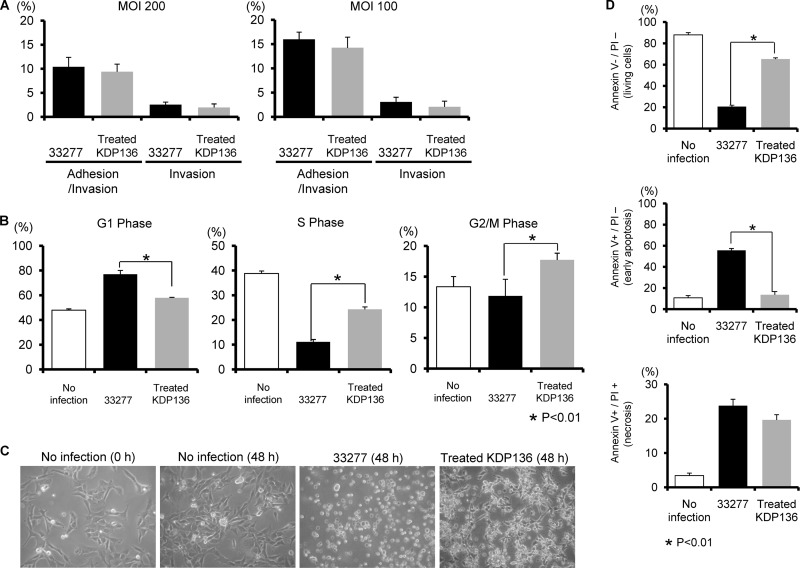

Gingipains trigger a signal transduction cascade.

P. gingivalis expresses several virulence factors, including fimbriae as well as gingipain enzymes comprised of arginine-X [Arg-gingipain A and B (RgpA and RgpB)]- and lysine-X [Lys-gingipain (Kgp)]-specific cysteine proteinases (18). We sought to investigate the role of these virulence factors in the initiation of signal transduction. Rgp processes precursor fimbria proteins (38), and thus, Rgp-null mutants lack mature FimA fimbriae on their surfaces. As the fimbriae are required for adherence to HTR-8 cells (data not shown), we utilized bacterial culture supernatants containing soluble Rgp to express mature fimbriae on the surface of Rgp-null mutants as previously described (24). The Kgp- and Rgp-null mutant (KDP136) was treated with exogenous gingipains as described in Materials and Methods, and the treated KDP136 mutant was shown to possess mature fimbriae (see Fig. S3A in the supplemental material). Gingipain activities of treated KDP136 were confirmed to be negligible (see Fig. S3B). Furthermore, the adhesion and invasion abilities did not differ significantly between the wild type and treated KDP136 (Fig. 7A). Conversely, treated KDP136 failed to cause a progressive increase in G1-phase cells or a corresponding decrease in S- and G2/M-phase cells (Fig. 7B). The wild-type strain caused rounding and detachment of some cells. In contrast, treated KDP136 did not induce these changes, though slightly deformed cell shapes were observed (Fig. 7C). We also examined the involvement of gingipains in apoptosis. Early apoptosis was reduced in response to treated KDP136, whereas necrotic responses were similar between the parental and treated KDP136 strains (Fig. 7D). In addition, treated KDP136 significantly decreased the levels of caspase 3 induction compared to the parental strain (Fig. 7E). Finally, we examined the effect of gingipain on the expression and phosphorylation status of ATR, ATM, Chk1, Chk2, p53, and MDM2 and on levels of Ets1, Fas, p16, and p21 in HTR-8 cells. Notably, the amount and phosphorylation of MDM2, which are suppressed by the wild-type strain (Fig. 2), were increased in response to treated KDP136 (Fig. 7F). For the other molecules tested, the effects of treated KDP136 were similar to those of the wild type. It is possible that the activation of ATR-p53 and ERK-Ets1 pathways may be directly affected by loss of gingipain activity. To clarify the effect of gingipains on those pathways, expression of Ets1, p16, Chk2, and p21 mRNAs was determined using real-time PCR (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Wild-type and treated KDP136 elevated levels of Chk2 and p16 mRNA to the same degree, although the increase in Ets1 and p21 mRNA expression following wild-type infection was higher than that following infection with treated KDP136. These results suggest that P. gingivalis gingipains may specifically degrade MDM2 protein and modulate the activity of multiple signaling pathways, resulting in both cell cycle arrest and cell death in HTR-8 cells.

Fig 7.

HTR-8 cells infected with a P. gingivalis fimbriated gingipain-null mutant strain do not show G1 arrest and apoptosis. (A) Antibiotic protection invasion assay with P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 (wild type) and fimbriated KDP136 (fimbriated gingipain-null mutant strain). HTR-8 cells were infected with P. gingivalis strains at an MOI of 100 or 200 for 2 h. Numbers of adherent and/or intracellular bacteria were determined by viable counting of the cell lysates and are expressed as percentage of input bacterial cell number. Data are means ± SD of three independent experiments and were analyzed with a t test. (B) Cell cycle distribution was determined using flow cytometry. The fold change in numbers of cells in each phase of the cell cycle was calculated in comparison with noninfected cells. Data are means ± SD of three independent experiments and analyzed with a t test. (C) Light microscopy showing morphology of HTR-8 cells infected with P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 and fimbriated KDP136 at an MOI of 200 for 48 h. (D) Cells were stained with annexin V and PI and analyzed using flow cytometry. The fold change was calculated as described for panel B. The mean percentage ± SD of apoptotic (annexin V+/PI−) cells from three independent experiments was determined and analyzed with a t test. (E) Fold change in caspase 3 activity. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments analyzed with a t test. (F) Cells were infected with P. gingivalis fimbriated KDP136 at an MOI of 200 for the indicated times. Lysates of infected and noninfected cells were subjected to immunoblotting to analyze expression profiles of DNA damage-responsive proteins, MDM2 phosphorylated at Ser166, MDM2, Ets1, Fas, p16, and p21. β-Actin was included as a loading control. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

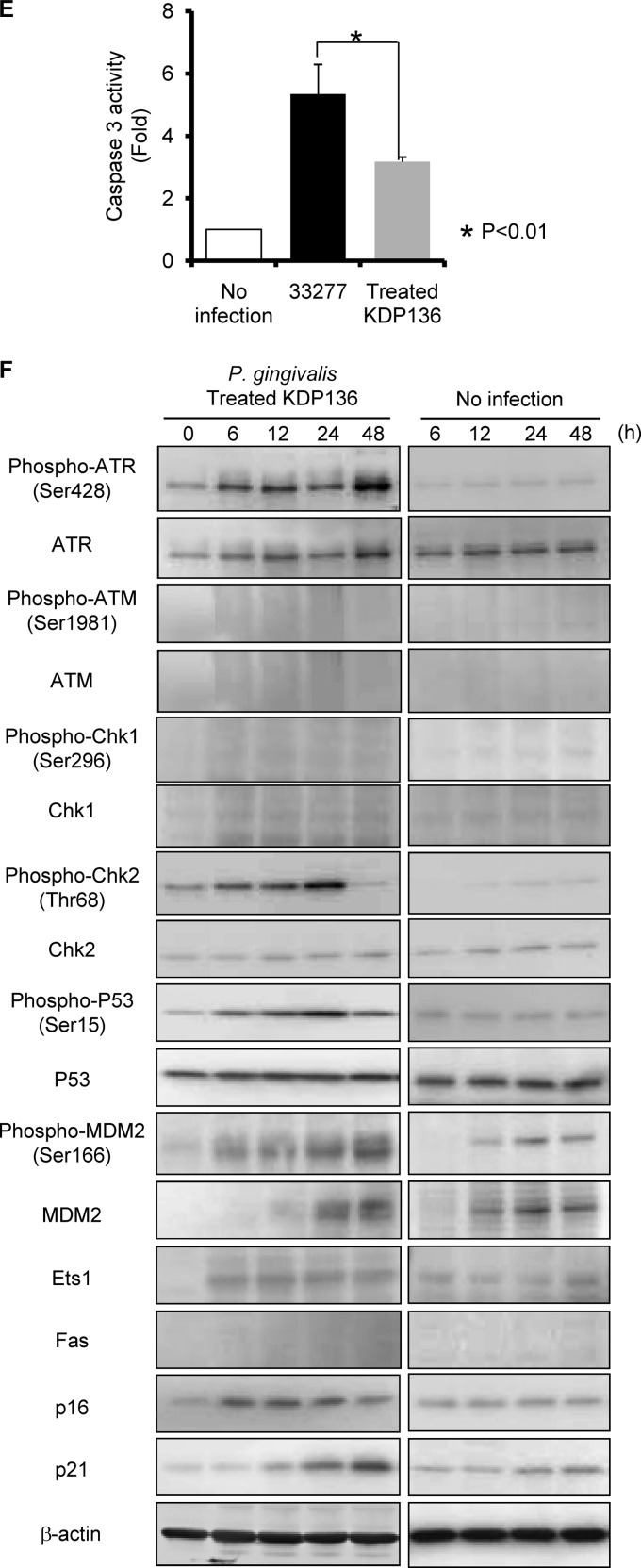

Placental growth occurs in the first trimester and involves coordinated events in the trophoblasts and mesenchyme. Progenitor cytotrophoblasts differentiate into villous intermediate cells, and these cells are programmed to fuse with the syncytium or into extravillous migratory cells that transform the maternal vascular supply. The villous trophoblast bilayer is the primary barrier between maternal and fetal tissues. The syncytium is a structural component of maternal-facing layer and a barrier to pathogens and the maternal cells (2). Extravillous trophoblast (EVT) invasion is an essential step in placental formation and is important for fetal growth and well-being (26). HTR-8 cells were established from first-trimester EVTs (17), while HTR-8/SVneo cells are the immortalized derivative of HTR-8 cells and exhibit a normal EVT phenotype and genotype (17, 29). P. gingivalis can invade trophoblasts in vitro and cause apoptosis and cell cycle arrest at G1 (21). In addition, P. gingivalis has been detected in the amniotic fluid and placenta in preterm labor, as a result of hematogenous spread (4, 30). A role for P. gingivalis in pregnancy complications is also supported by animal models, indicating bacterial invasion of both maternal and fetal tissues (6, 10, 32). Trophoblasts differentially regulate the expression of over 2,000 genes following P. gingivalis infection (44), which may impact many signaling pathways, including those involved in control of cell cycle and apoptosis. Thus, we examined the effect of P. gingivalis infection on the signaling pathways which regulate cell cycle and apoptosis. P. gingivalis infection was shown to alter expression profiles of DNA damage response proteins, which was accompanied by G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. This is the first comprehensive examination of the signaling pathways of DNA damage response induced by P. gingivalis infection. The involvement of p53, Ets1, and ATR in cellular responses was also shown by siRNA knockdown and chemical inhibition. Furthermore, gingipain proteolytic activity was found to play an essential role in the induction of G1 arrest and apoptosis, due to the lack of induction of MDM2. Based on these findings, we propose that P. gingivalis initiates the signaling cascade shown in Fig. 8.

Fig 8.

Proposed schematic model for cell cycle regulation and induction of apoptosis in HTR-8 cells infected with P. gingivalis. P. gingivalis invasion leads to activation of ATR. Upon activation, ATR phosphorylates Chk2, resulting in progressive Chk2 activation. Chk2 then phosphorylates and activates p53, inducing p21 and the gene expressing proapoptotic Fas. Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 causes Ets1 activation, which in turn activates p16 and p53.

The Ras-dependent ERK1/2 MAPK pathway plays a central role in control of cell proliferation, and sustained activation of ERK1/2 is necessary for G1-to-S-phase progression and positive regulation of the cell cycle. However, excessive activation of ERK1/2 can instead lead to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis (21, 48). Downstream of Ras are the effector kinases Raf/MEK/ERK1/2 (13), while Ets1 and p16 are the downstream mediators of ERK1/2 (19, 61). Moreover, p16 has an antiproliferative function through the G1 phase of the cell cycle in response to Ets1 and ERK signaling activity cycles (19, 61). Hence, activation of this pathway is consistent with our finding of the G1 arrest and apoptosis mediated by P. gingivalis. Chk2 was phosphorylated at threonine 68 when cells were damaged by ionizing radiation (IR), UV irradiation, hydroxyurea (HU) (37), arsenic trioxide (23), and cisplatin (41), and activation was shown to be mediated by ATM (20, 37) and ATR (23, 37, 41). In addition, Chk2 phosphorylation parallels p53 phosphorylation on Ser15 (37). In the present study, DNA damage response induced by P. gingivalis infection led to ATR but not ATM activation (Fig. 2 and 7F). Moreover, Chk2 was phosphorylated at threonine 68 (Fig. 2 and 7F). Interestingly, ATR-Chk2 pathways were activated by P. gingivalis invasion with and without gingipain proteases. Accordingly, ATR likely phosphorylates and activates Chk2 during P. gingivalis invasion damage, which in turn leads to p53 phosphorylation at Ser15. Previous studies have noted that p53 phosphorylation at Ser15 is crucial for p53-dependent p21 expression (60) and does not require the presence of ATM kinase (5).

Several pathogens, such as Salmonella enterica (42), Streptococcus pyogenes (57), and Helicobacter pylori (55), have been reported to induce apoptosis mediated by Fas. H. pylori can also induce apoptosis through activation of p53 (8). However, the interaction between p53 and Fas expression in bacterial infection has yet to be characterized. The finding that DNA damage response in HTR-8 cells induced by P. gingivalis increased p53 accumulation and Fas activation suggests that both proteins are targets of P. gingivalis in an MOI-dependent manner (Fig. 1). Those findings also suggest that G1 arrest or apoptosis related to p53 and Fas expression may be MOI dependent in HTR-8 cells infected with P. gingivalis in vivo. While the levels of P. gingivalis in placental tissue are unknown, an immunohistochemical study suggested that they can be quite high in cases of preterm delivery (25). Knockdown of p53 with siRNA inhibited Fas expression, G1 arrest, and apoptosis (Fig. 4), suggesting that DNA damage response can induce transcriptional upregulation of FAS through p53-dependent mechanisms, as demonstrated with other cell types (14). These findings suggest that Fas induction is controlled by p53 after P. gingivalis infection. The p53 protein plays a central role in cellular responses to a variety of stress signals. Normally, p53 levels are kept low through activity of the negative regulator MDM2. However, those levels rapidly increase after stimulation by several stressors, which results in disruption of MDM2-p53 interaction (36, 58). Ser166 phosphorylation of MDM2 has been shown to increase its ubiquitin ligase activity and increase p53 degradation (35). Notably, a significant decrease in levels of phosphorylated and total MDM2 was observed in P. gingivalis-infected cells, and this decrease was dependent on the presence of gingipains. Together, these results suggest that P. gingivalis gingipain proteases degrade MDM2, thus contributing to p53 accumulation and apoptosis. This is the first report of such an MDM2-specific degradation response to pathogen infection.

Although neither caspase 3 activity nor Fas induction occurred in response to treated KDP136, necrotic changes were observed in response to both the wild-type and treated KDP136 strains. Recent evidence suggests that necrosis can also be programmed, though in a manner distinguishable from apoptosis (47). In addition, that report noted that under conditions where caspases are inhibited or signaling through Fas is otherwise prevented, apoptotic stimuli can induce necrosis. Our results suggest that caspase activity and/or Fas induction via the ATR/Chk2/p53 pathway require gingipains, while induction of p21 by P. gingivalis occurs in a gingipain-independent manner. The negative regulation of apoptosis by p21 has been attributed to interaction with procaspase 3, resulting in inhibition of its activity (1). Thus, necrosis may be induced following infection with treated KDP136. When all the data are considered, gingipains are strongly implicated as an important factor in apoptosis induction.

P. gingivalis impacts the cell cycle as well as apoptosis through the upregulation of p16 and p21 and phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (21). p53 can either cause cell cycle arrest by transactivation of p21 or induce cells to undergo apoptosis (28). In addition, Ets1 controls the regulation of p16 (19, 39). However, the interaction between p53 and Ets1 in regard to the cell cycle has yet to be investigated. We found that the levels of p16 and p21 were diminished by knockdown of p53 and Ets1, respectively, while p16 amounts were decreased in Ets1-silenced cells following P. gingivalis infection. Additionally, p21 was diminished by the silencing of p53 and/or Ets1. HTR-8 cells infected with P. gingivalis also exhibited a sustained activation of Ets1, and knockdown of Ets1 abrogated both G1 arrest and apoptosis. Moreover, the levels of p16, p21, p53, and Fas were decreased when Ets1 amounts were reduced (Fig. 4 and 6). This impact of P. gingivalis suggests that p16 and p21 may be under the control of ERK1/2-Ets1 and p53 pathways. This is consistent with reports showing that the p53 gene is transcriptionally regulated by Ets1 (3), and a deficiency of Ets1 decreases p53 expression level and reduces apoptosis induced by p53 in response to UV exposure (62). Collectively, these results indicate that P. gingivalis diverts the ERK1/2-Ets1 and p53 signaling pathways, resulting in both cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.

In conclusion, P. gingivalis infection of HTR-8 cells causes cytopathic effects that are likely mediated by DNA damage response and MAPK activation. We propose that the activation of DNA damage response and ERK1/2 results from P. gingivalis invasion of trophoblasts, and that the ensuing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest are potentially synergistic mechanisms that contribute to PTLBW associated with this periodontal pathogen.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the members of the Amano and Lamont labs for their helpful discussions. We also thank Mayumi Yoshimori for the technical assistance.

This research was supported by a grants-in-aid for Scientific Research (22659378 to A.A. and 23792102 to H.I.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and by NIDCR grant DE11111 to R.J.L.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 June 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abbas T, Dutta A. 2009. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 9:400–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aplin DJ. 2010. Developmental cell biology of human villous trophoblast: current research problems. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 54:323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baillat D, Bègue A, Stéhelin D, Aumercier A. 2002. ETS-1 transcription factor binds cooperatively to the palindromic head to head ETS-binding sites of the stromelysin-1 promoter by counteracting autoinhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 277:29386–29398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barak S, Oettinger-Barak O, Machtei EE, Sprecher H, Ohel G. 2007. Evidence of periopathogenic microorganisms in placentas of women with preeclampsia. J. Periodontol. 78:670–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Behrman RE, Butler AS. (ed). 2007. Preterm birth: causes, consequences, and prevention. National Academies Press, Washington, DC: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bélanger M, et al. 2008. Colonization of maternal and fetal tissues by Porphyromonas gingivalis is strain-dependent in a rodent animal model. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 199:e1–e7 doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.11.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bennett M, et al. 1998. Cell surface trafficking of Fas: a rapid mechanism of p53-mediated apoptosis. Science 282:290–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhattacharyya A, et al. 2009. Acetylation of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease-1 regulates Helicobacter pylori-mediated gastric epithelial cell apoptosis. Gastroenterology 136:2258–2269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reference deleted.

- 10. Boggess KA, Madianos PN, Preisser JS, Moise KJ, Jr, Offenbacher S. 2005. Chronic maternal and fetal Porphyromonas gingivalis exposure during pregnancy in rabbits. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 192:554–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choudhuri T, Verma SC, Lan K, Murakami M, Robertson ES. 2007. The ATM/ATR signaling effector Chk2 is targeted by Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 3C to release the G2/M cell cycle block. J. Virol. 81:6718–6730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cimprich KA, Cortez D. 2008. ATR: an essential regulator of genome integrity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:616–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dittmer J. 2003. The biology of the Ets1 proto-oncogene. Mol. Cancer 2:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. El-Deiry WS. 2001. Insights into cancer therapeutic design based on p53 and TRAIL receptor signaling. Cell Death Differ. 8:1066–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Lams JD, Romero R. 2008. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 371:75–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goldenberg RL, Goepfert AR, Ramsey PS. 2005. Biochemical markers for the prediction of preterm birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 192:36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graham CH, et al. 1993. Establishment and characterization of first trimester human trophoblast cells with extended lifespan. Exp. Cell Res. 206:204–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guo Y, Nquyen KA, Potempa J. 2010. Dichotomy of gingipains action as virulence factors: from cleaving substrates with the precision of a surgeon's knife to a meat chopper-like brutal degradation of proteins. Periodontol. 2000 54:15–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Han J, Tsukada Y, Hara E, Kitamura N, Tanaka T. 2005. Hepatocyte growth factor induces redistribution of p21CIP1 and p27KIP1 through ERK-dependent p16INK4a up-regulation, leading to cell cycle arrest at G1 in HepG2 hepatoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 280:31548–31556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harper JW, Elledge SJ. 2007. The DNA damage response: ten years after. Mol. Cell 28:739–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Inaba H, et al. 2009. Porphyromonas gingivalis invades human trophoblasts and inhibits proliferation by inducing G1 arrest and apoptosis. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1517–1532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ito H, et al. 2004. Prostaglandin E2 enhances pancreatic cancer invasiveness through an Ets-1-dependent induction of matrix metalloproteinase-2. Cancer Res. 64:7439–7446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Joe Y, et al. 2006. ATR, PML, and CHK2 play a role in arsenic trioxide-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 281:28764–28771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kato T, et al. 2007. Maturation of fimbria precursor protein by exogenous gingipains in Porphyromonas gingivalis gingipain-null mutant. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 273:96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Katz J, Chegini N, Shiverick KT, Lamont RJ. 2009. Localization of P. gingivalis in preterm delivery placenta. J. Dent. Res. 88:575–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kaufmann P, Black S, Huppertz B. 2003. Endovascular trophoblast invasion: implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and preeclampsia. Biol. Reprod. 69:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lamont RJ, et al. 1995. Porphyromonas gingivalis invasion of gingival epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 63:3878–3885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lavin MF, Gueven N. 2006. The complexity of p53 stabilization and activation. Cell Death Differ. 13:941–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee BP, Rushlow WJ, Chakraborty C, Lala PK. 2001. Differential gene expression in premalignant human trophoblast: role of IGFBP-5. Int. J. Cancer 94:674–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leon R, et al. 2007. Detection of Porphyromonas gingivalis in the amniotic fluid in pregnant women with a diagnosis of threatened premature labor. J. Periodontol. 78:1249–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li Y, et al. 2011. SIRT2 down-regulation in HeLa can induce p53 accumulation via p38 MAPK activation-dependent p300 decrease, eventually leading to apoptosis. Genes Cells 6:34–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lin D, et al. 2003. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection in pregnant mice is associated with placental dissemination, an increase in the placental Th1/Th2 cytokine ratio, and fetal growth restriction. Infect. Immun. 71:5163–5168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Luo MH, Rosenke K, Czornak K, Fortunato EA. 2007. Human cytomegalovirus disrupts both ataxia telangiectasia mutated protein (ATM)- and ATM-Rad3-related kinase-mediated DNA damage responses during lytic infection. J. Virol. 81:1934–1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Luo Y, Chen AY, Qiu J. 2011. Bocavirus infection induces a DNA damage response that facilitates viral DNA replication and mediates cell death. J. Virol. 85:133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Malmlöf M, Roudier E, Högberg J, Stenius U. 2007. MEK-ERK-mediated phosphorylation of Mdm2 at Ser-166 in hepatocytes. Mdm2 is activated in response to inhibited Akt signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 282:2288–2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Manfredi JJ. 2010. The Mdm2-p53 relationship evolves: Mdm2 swings both ways as an oncogene and a tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 24:1580–1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Matsuoka S, et al. 2000. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated phosphorylates Chk2 in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:10389–10394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nakayama K, Yoshimura F, Kadowaki T, Yamamoto K. 1996. Involvement of arginine-specific cysteine proteinase (Arg-gingipain) in fimbriation of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 178:2818–2824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ohtani N, Yamakoshi K, Takahashi A, Hara E. 2004. The p16INK4a-RB pathway: molecular link between cellular senescence and tumor suppression. J. Med. Invest. 51:146–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Orba Y, et al. 2010. Large T antigen promotes JC virus replication in G2-arrested cells by inducing ATM- and ATR-mediated G2 checkpoint signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 285:1544–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pabla N, Huang S, Mi QS, Daniel R, Dong Z. 2008. ATR-Chk2 signaling in p53 activation and DNA damage response during cisplatin-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 283:6572–6583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Paolillo R, Carratelli CR, Rizzo A. 2011. Effect of resveratrol and quercetin in experimental infection by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Int. Immunopharmacol. 11:149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. 2005. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 366:1809–1820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Riewe SD, et al. 2010. Human trophoblast responses to Porphyromonas gingivalis infection. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 25:252–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Roos WP, Kaina B. 2006. DNA damage-induced cell death by apoptosis. Trends Mol. Med. 12:440–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roshal M, Kim B, Zhu Y, Nghiem P, Planelles V. 2003. Activation of the ATR-mediated DNA damage response by the HIV-1 viral protein R. J. Biol. Chem. 278:25879–25886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rudel T, Kepp O, Kozjak-Pavlovic V. 2010. Interactions between bacterial pathogens and mitochondrial cell death pathways. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:693–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sarfaraz S, Afaq F, Adhami VM, Malik A, Mukhtar H. 2006. Cannabinoid receptor agonist-induced apoptosis of human prostate cancer cells LNCaP proceeds through sustained activation of ERK1/2 leading to G1 cell cycle arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 281:39480–39491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Scacheri PC, et al. 2004. Short interfering RNAs can induce unexpected and divergent changes in the levels of untargeted proteins in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:1892–1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Scian MJ, et al. 2004. Modulation of gene expression by tumor-derived p53 mutants. Cancer Res. 64:7447–7454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shi Y, et al. 1999. Genetic analyses of proteolysis, hemoglobin binding, and hemagglutination of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Construction of mutants with a combination of rgpA, rgpB, kgp, and hagA. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17955–17960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shirata N, et al. 2005. Activation of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated DNA damage checkpoint signal transduction elicited by herpes simplex virus infection. J. Biol. Chem. 280:30336–30341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shoji M, et al. 2004. The major structural components of two cell surface filaments of Porphyromonas gingivalis are matured through lipoprotein precursors. Mol. Microbiol. 52:1513–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Song KS, Lee TJ, Kim K, Chung KC, Yoon JH. 2008. cAMP-responding element-binding protein and c-Ets1 interact in the regulation of ATP-dependent MUC5AC gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 283:26869–26878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stoicov C, et al. 2005. Major histocompatibility complex class II inhibits Fas antigen-mediated gastric mucosal cell apoptosis through actin-dependent inhibition of receptor aggregation. Infect. Immun. 73:6311–6321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Toller IM, et al. 2011. Carcinogenic bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori triggers DNA double-strand breaks and a DNA damage response in its host cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:14944–14949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tsai WH, et al. 2008. Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B-induced apoptosis in A549 cells is mediated through αvβ3 integrin and Fas. Infect. Immun. 76:1349–1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vazquez A, Bond EE, Levine JA, Bond LG. 2008. The genetics of the p53 pathway, apoptosis and cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7:979–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vettore MV, et al. 2008. The relationship between periodontitis and preterm low birthweight. J. Dent. Res. 87:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wang H, et al. 2008. An ATM- and Rad3-related (ATR) signaling pathway and a phosphorylation-acetylation cascade are involved in activation of p53/p21Waf1/Cip1 in response to 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine treatment. J. Biol. Chem. 283:2564–2574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Xia M, Knezevic D, Vassilev LT. 2011. p21 does not protect cancer cells from apoptosis induced by nongenotoxic p53 activation. Oncogene 30:346–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Xu D, et al. 2002. Ets1 is required for p53 transcriptional activity in UV-induced apoptosis in embryonic stem cells. EMBO J. 21:4081–4093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhao H, Piwnica-Worms H. 2001. ATR-mediated checkpoint pathways regulate phosphorylation and activation of human Chk1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4129–4139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.