Abstract

The interleukin-1 family of cytokines are essential for the control of pathogenic microbes but are also responsible for devastating autoimmune pathologies. Consequently, tight regulation of inflammatory processes is essential for maintaining homeostasis. In mammals, interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) is primarily regulated at two levels, transcription and processing. The main pathway for processing IL-1β is the inflammasome, a multiprotein complex that forms in the cytosol and which results in the activation of inflammatory caspase (caspase 1) and the subsequent cleavage and secretion of active IL-1β. Although zebrafish encode orthologs of IL-1β and inflammatory caspases, the processing of IL-1β by activated caspase(s) has never been examined. Here, we demonstrate that in response to infection with the fish-specific bacterial pathogen Francisella noatunensis, primary leukocytes from adult zebrafish display caspase-1-like activity that results in IL-1β processing. Addition of caspase 1 or pancaspase inhibitors considerably abrogates IL-1β processing. As in mammals, this processing event is concurrent with the secretion of cleaved IL-1β into the culture medium. Furthermore, two putative zebrafish inflammatory caspase orthologs, caspase A and caspase B, are both able to cleave IL-1β, but with different specificities. These results represent the first demonstration of processing and secretion of zebrafish IL-1β in response to a pathogen, contributing to our understanding of the evolutionary processes governing the regulation of inflammation.

INTRODUCTION

The interleukin-1 cytokine family includes 11 members, of which mammalian interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1α), interleukin-18 (IL-18), and the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) have been extensively characterized (2). IL-1β is the quintessential proinflammatory cytokine, present during infection and immune challenge as well as implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous autoinflammatory diseases (9). Maintaining homeostasis requires coordinated regulation of the amount of circulating active IL-1β. Accordingly, in mammals, IL-1β activity is regulated at various levels, including synthesis, processing, and secretion, and by various mechanisms of inhibition of IL-1β-mediated signaling (10). IL-1β is synthesized as an inactive 31-kDa precursor (pro-IL-1β) which requires processing to produce the secreted, bioactive 17-kDa mature peptide. Processing occurs primarily through the actions of the cysteine protease, caspase 1 (also called the interleukin-converting enzyme [ICE]) (52), though several additional proteases can cleave IL-1β into active forms (7, 12, 18, 21, 40, 51). Prior to its ability to process IL-1β, caspase 1 itself must be activated in a multiprotein complex known as the inflammasome. The inflammasome, which generally includes one or more pathogen recognition receptors, the adaptor protein ASC, and caspase 1, assembles in response to danger or pathogen-associated signals (6, 33). Therefore, at least two signals are required for the generation of active IL-1β: transcriptional upregulation following pathogen detection or cytokine signaling and activation of the inflammasome and caspase 1 by a second recognition of danger, pathogen-associated, or cytokine signals in the cytosol (56).

The mechanism of regulating IL-1β activity via caspase 1 activation is essential in mammals, but the evolutionary history of this process remains unclear. Fish have orthologs of IL-1β cytokines that function in ways analogous to those in mammalian species. In fish leukocytes, IL-1β is transcriptionally upregulated during infection and proinflammatory stimulus, and recombinant IL-1β stimulates an acute-phase response (5, 16, 17, 23, 32, 58). However, with a few exceptions, all nonmammalian IL-1β proteins described thus far, including in zebrafish, lack the canonical caspase 1 cleavage site (58). In addition, fish encode orthologs of inflammatory caspases (caspase 1 and caspase 5) that possess highly conserved catalytic domains, and functional studies have demonstrated that these caspase orthologs cleave caspase-1- and caspase-5-specific substrates and are inhibited by caspase-1-specific inhibitors (29, 35). Although the accumulation of truncated forms of IL-1β of various lengths has been demonstrated following immune stimulus in carp (36), trout (15), and gilthead sea bream (20, 29), the direct processing of nonmammalian IL-1β by a caspase 1 ortholog has not been addressed.

Zebrafish is an increasingly popular model organism for studying host-pathogen interactions and immunity (1, 37, 38, 47, 53, 54, 55). To further develop the potential of zebrafish as a model for inflammatory processes and infectious disease, it is necessary to know whether IL-1β activity is regulated at the level of proteolytic processing and, if so, whether a caspase 1 ortholog is responsible. Therefore, the goal of this study was to determine if processing of zebrafish IL-1β occurs during Francisella infection as found in mammals (11, 31) and to determine whether zebrafish inflammatory caspases are involved in this process. By using specific antisera against zebrafish IL-1β, we found that processing takes place in primary leukocyte cultures in response to Francisella infection. Through the use of an in vitro processing system, we demonstrate that two distinct zebrafish inflammatory caspase orthologs are capable of cleaving zebrafish IL-1β, though with subtly different specificities. Processing of IL-1β is absolutely required for secretion both ex vivo and in vitro. Thus, this work demonstrates the conservation of multiple regulatory mechanisms to control IL-1β-induced inflammation and implies conservation of the inflammasome platform across vertebrate phylogeny.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Zebrafish care and maintenance.

The EKW strain of zebrafish was maintained as described in reference 57. The protocols for experimental use of zebrafish for this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Washington and the USGS Western Fisheries Research Center (Seattle, WA).

Production and purification of zebrafish recombinant IL-1β.

Soluble, glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged zebrafish IL-1β was produced as an antigen for the production of rabbit polyclonal antisera. PCR was performed on zebrafish cDNAs obtained in protocols described in reference 57 using primer set drIL-1β 1 (Table 1). The PCR product was gel purified, cloned into the BamHI/XhoI sites of pGEX-4T-1 (GE Healthcare), and confirmed by sequencing.

Table 1.

PCR primers and probes

| Primer namea | Gene and accession no. | Nucleotide sequence (5′–3′) | Application(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| drIL-1β_1_F | IL-1β | ATTAGGATCCACCATGGCATGCGGGCAATATGAAG | Cloning, pGEX vector |

| drIL-1β_1_R | NM_212844.1 | ATTACTCGAGCTGATGCGCACTTTATCCTGCAGCTC | |

| drIL1β_Q_FL | IL-1β | ATTAGATATCAATGGCATGCGGGCAATATGA | Cloning, pQE-Tri vector |

| drIL1β_Q_clev104 | NM_212844.1 | ATTAGATATCAATGTCAGTGCCGTCTTACACTAA | |

| drIL1β_Q_R | ATTAGCGGCCGCGATGCGCACTTTATCCTGCAGCTCGA | ||

| dr-E-IL-1β_F | IL-1β | ATTAGGATCCACCATGGCATGCGGGCAATATGAAG | Cloning, pcDNA3.1 |

| dr-E-IL-1β_R | NM_212844.1 | ATTACTCGAGCTGATGCGCACTTTATCCTGCAGCTC | |

| drC-A_F | Caspase A | ATTAGAATTCGCCACCATGGCCAAATCTATCAAGGACCAT | Cloning pFLAG |

| drC-A_R | NM_131505 | ATTATCTAGATCAGAGTCCGGGGAACAGGTAGAACAACT | |

| drIL1β-D88A-F | IL-1β | GAAAAAGAGGTGCTGGCCATGCTCATGGCGAAC | Mutagenesis |

| drIL1β-D88A-R | NM_212844.1 | GTTCGCCATGAGCATGGCCAGCACCTCTTTTTC | |

| drIL1β-D104A-F | GAAGTGAACGTGGTGGCCTCAGTGCCGTCTTACAC | ||

| drIL1β-D104A-R | GTGTAAGACGGCACTGAGGCCACCACGTTCACTTC | ||

| drIL1β-D122A-F | GCAATGCACGATTTGCGCTCAGTATAAGAAGTCTC | ||

| drIL1β-D122A-R | GAGACTTCTTATACTGAGCGCAAATCGTGCATTGC | ||

| drC-B_F | Caspase B | CACCAAGCTTATGGAGGATATTACCMAGYTGMT | Cloning pFLAG |

| drC-B_R | NM_001145592 | ATTAGTCGACCAGTCCAGGAAACAGGTAGAA |

“dr” stands for “Danio rerio.”

BL21 cells (Invitrogen) were transformed with pGEX-drIL-1β, and a single colony was cultured in 10 ml of LB-ampicillin (100-μg/ml) broth at 37°C overnight. This culture was subcultured into 500 ml of LB-ampicillin, grown at 37°C to an A600 of 0.4 to 0.6, and induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG; MP Biomedicals) for 2.5 h at 30°C. Bacteria were pelleted (5,000 × g for 20 min, 4°C) and frozen at −80°C. Pellets were then resuspended in a 1:20 volume of glutathione bead binding/wash buffer (B/W buffer; 125 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0), which included 1× HALT protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and lysed by sonication. The insoluble portion of the bacterial lysate was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. GST-tagged IL-1β was purified from the soluble fraction using glutathione magnetic beads (Thermo) according to the manufacturer's directions and dialyzed (1-kDa cutoff; minidialysis kit; GE Healthcare) 3 times against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4 (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 1.46 mM KH2PO4). Protein concentrations were determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo), and the size and purity of protein preparations were confirmed by SDS-PAGE.

Affinity purification of drIL-1β polyclonal antisera.

Serum from rabbits immunized with purified GST-tagged zebrafish (Danio rerio) IL-1β was obtained from Cocalico Biologicals, Inc. Serum was diluted 1:2 in PBS buffer and passed 3 times over an immobilized GST-agarose column (Thermo) to remove antibodies to GST. For affinity purification of drIL-1β antibodies, recombinant His-streptomycin (Strep)-tagged drIL-1β was covalently bound to AminoLink Plus coupling resin (Thermo) according to the Pierce Direct IP kit protocol. Anti-GST-depleted serum was incubated on these columns for 2 h at 4°C with rotation and washed 3 times with cold PBS plus 0.5% NP-40, and antibodies were eluted with IgG elution buffer (Thermo) and immediately neutralized with 1 M Tris, pH 8.0. Eluted antibodies were dialyzed 2 times against sterile PBS, pH 7.4; concentrations were assessed by BCA protein assay (Thermo); and purity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE coupled with Coomassie brilliant blue staining. Purified antibodies were aliquoted and stored at −20°C.

For prebleed IgG fractions used for preclearing, total rabbit IgG was purified from prebleed sera. Serum was diluted 1:2 in PBS and passed over a Gammabind protein G column (Amersham). IgG was eluted, dialyzed, and stored as described above.

Ex vivo infection and stimulation of zebrafish leukocyte cultures.

For ex vivo stimulation assays, adult zebrafish were euthanized in sodium bicarbonate-buffered MS222 (300 ng/ml; Sigma). Spleen and head kidney were dissected into L15 medium plus 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for each fish individually. Single-cell suspensions were obtained by pipetting and then plated individually in a final volume of 200 μl in 48-well plates. In experiments with caspase inhibitors, cells were incubated with 185 μΜ Ac-Y-VAD-fmk (maximum recommended concentration) or 20 μM Z-VAD pancaspase inhibitor (maximum recommended concentration) (both from Enzo Lifesciences) for 1 h prior to infection with bacteria.

For Francisella infections of primary zebrafish cells, Francisella noatunensis (39, 43), originally isolated from hybrid striped bass (57), was used. Bacteria were initially cultured at 26°C on CHAH plates consisting of cysteine heart agar (Difco) supplemented with 1% hemoglobin (Oxoid). For infections, F. noatunensis colonies from 4-day-old CHAH plates were scraped into sterile TSBCD broth (Trypticase soy broth [30 g/liter; Sigma], 0.1% cysteine, 0.2% dextrose), vortexed, and grown overnight at 26°C with shaking (200 rpm). Bacteria were pelleted and diluted in sterile PBS to specific OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) concentrations corresponding to approximate CFU/ml as previously determined (49). Heat killing of bacterial samples was conducted at 56°C for 1 h. Bacterial cells diluted to the appropriate concentrations in PBS were used to infect zebrafish spleen and kidney single-cell suspensions for 8 h at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50. The final concentrations of infectious bacteria were determined and the viability of heat-killed cultures was assessed by plating and enumerating serial dilutions used for infections on CHAH plates.

Caspase activity assays.

After infection with F. noatunensis, supernatants from zebrafish cell cultures were collected and centrifuged to pellet nonadherent cells. Adherent cells were lysed with 100 μl of caspase 1 activity assay cell lysis buffer (GenScript). The suspension cell pellet was washed once with ice-cold PBS, and then the lysate from the adherent cell pellet fraction was added to the washed cell pellet and placed on ice for 10 min. Caspase 1 activity from equivalent volumes of supernatant or lysed cell pellet fractions was determined with the caspase 1 activity assay from GenScript according to the manufacturer's instructions. The slope of the linear phase of the reaction curve was calculated. Values reported are the mean rates from four independent experiments. Significance was calculated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's posttest.

Immunoprecipitation and detection of endogenous IL-β.

For detection of IL-1β from primary zebrafish cells, spleen and kidney suspensions were prepared and infected as described above. Supernatant was collected and centrifuged to pellet nonadherent cells. Adherent cells were lysed with 120 μl of 1% NP-40 lysis buffer (Boston Bioproducts) with 1× HALT protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo). The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail was added. The suspension cell pellet was washed once with ice-cold PBS, and then the lysate from the adherent cell fraction was added to the washed suspension cell pellet and placed on ice for 10 min. Lysates were passed through a 21-gauge needle and placed on ice for an additional 10 min. Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min prior to BCA assay (Thermo) to determine total protein concentration. For immunoprecipitation of IL-1β from equivalent volumes of cell-free supernatant or equivalent total protein concentrations from cell pellet lysates, samples were first precleared for 1 h with 20 μl protein A/G agarose (50% slurry; Thermo) conjugated to 5 μg of rabbit prebleed IgG. Samples were then incubated with 2.5 μg of the anti-zebrafish IL-1β polyclonal antibodies preconjugated to protein A/G at 4°C overnight with rotation. After washing and boiling of samples in 2× protein loading buffer plus dithiothreitol (DTT) (Fermentas), immunoprecipitated proteins were electrophoresed on 4 to 20% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Thermo). Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Hybond-P; Amersham) and blocked with 5% blocking agent (Bio-Rad). Blots were incubated with the polyclonal antibody (PAb) against IL-1β (1 μg/ml) and then with Cleanblot immunoprecipitation (IP) detection reagent-horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Thermo). Blots were prepared with the Pierce Plus enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting substrate (Thermo) and exposed to Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare).

Zebrafish caspase A, caspase B, and IL-1β expression plasmids and IL-1β mutagenesis.

For expression in mammalian cells, zebrafish caspase A, caspase B, and IL-1β were cloned from cDNA obtained in protocols described in reference 57 using primers drC-A, drC-B, and dr-E-IL-1β, respectively (Table 1). The PCR products were cloned into pFLAG-CMV-2 (Sigma) for caspase A and caspase B and into pcDNA3.1-V5-His (Invitrogen) for drIL-1β. The amino acid substitutions of D88A, D104A, and D122A were introduced into pcDNA3.1-Zf-IL-1β-V5-His using primers (Table 1; drIL1β-D88A, -D104A, and -D122A) in conjunction with Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) per the QuikChange mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene). Double and triple mutants were constructed by GenScript. All clones were verified by sequencing.

Transfection, expression, immunoprecipitation, and immunodetection from HEK293 cells.

HEK293 cells (ATCC) were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (HyClone) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco) and 100 μg/ml kanamycin (Sigma) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were plated at 2.25 × 105 cells/ml in 10-mm plates containing 8 ml of complete medium 24 h prior to transfection. Cells were transiently transfected using jetPRIME (Polyplus Transfection) with 2.4 μg of pFLAG-Caspase A, pFLAG-Caspase B, or pFLAG vector and 2.8 μg of pcDNA3.1-ZF-IL-1β-myc-his or pcDNA-vector DNA; the total amount of plasmid DNA was adjusted with vector alone to always be the same across experiments. Cell pellet fractions were lysed 20 h posttransfection with 400 μl 1% NP-40 lysis buffer (Boston Bioproducts) with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo) at 4°C for 10 min. Debris was dislodged with a cell scraper, and the lysate was removed to microcentrifuge tubes for an additional 20 min on ice prior to clarification by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm. Total protein content of cell lysates was determined by BCA assay (Thermo). For immunoprecipitation of secreted IL-1β, culture supernatant was collected and centrifuged to remove cells. Cell-free supernatant was concentrated in Amicon-Ultra 4 centrifugal filter units with a 3-kDa cutoff (Millipore) to 2 ml to which 1× HALT protease inhibitor cocktail was added (Thermo). Concentrated supernatants were precleared with 20 μl of washed protein A/G (Thermo) for 1 h at 4°C and then incubated with 15 μl of protein A/G conjugated with 2.4 μg of anti-V5 antibody (Invitrogen) at 4°C overnight. Equal volumes of immunoprecipitated proteins or equivalent total protein from cell pellet fractions were electrophoresed on a 4 to 20% gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Thermo). Following transfer, proteins were detected by Western blotting using anti-V5 monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen) and anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody M2 (Sigma) followed by the Cleanblot IP detection reagent-HRP (Thermo). Loading of equivalent total protein from HEK293 cells was verified by blotting with an anti-β-actin antibody (THE beta-actin antibody-HRP; GenScript). Blots were prepared with the Pierce ECL Plus Western blotting substrate (Thermo) and exposed to Hyperfilm ECL (GE Healthcare).

RESULTS

Francisella noatunensis stimulates caspase-1-like specific activity in zebrafish cells.

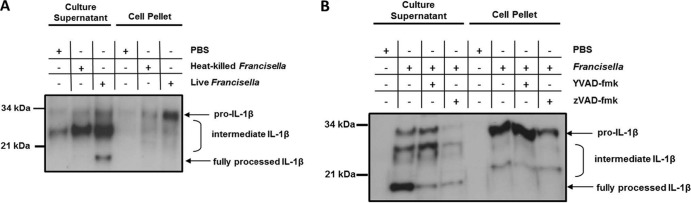

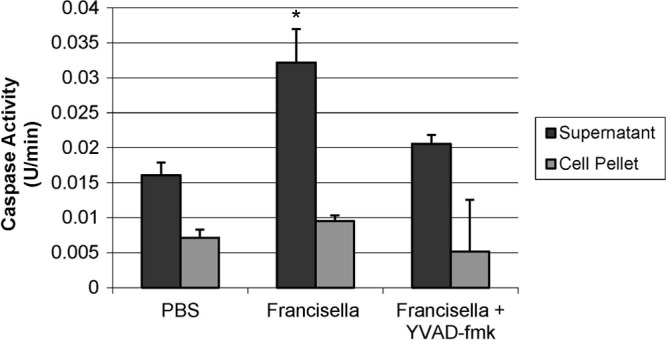

Francisella has been shown to induce significant caspase 1 activity in mammalian cells via activation of the inflammasome (26, 31). In order to determine whether this response is conserved in fish, zebrafish primary spleen and kidney single cell suspensions were infected with F. noatunensis and caspase 1 substrate activity was assessed with a fluorogenic caspase 1 substrate (Fig. 1). The zebrafish spleen and kidney are major sources of phagocytes (54, 59), the primary cell type infected by Francisella in mammals and fish (11, 49). Since in mammals the active form of caspase 1 is secreted from cells (22), culture supernatants and cell pellet fractions were assayed separately. The culture supernatants from cells infected with F. noatunensis contained significant caspase-1-like activity compared to cells incubated with PBS. This activity was partially abrogated by preincubation of the cells with the caspase-1-specific inhibitor YVAD-CMK. In contrast, the cell pellet did not have significant caspase-1-like activity in comparison to the PBS-stimulated cells. These results demonstrate that zebrafish leukocytes activate and secrete a protease with caspase-1-like substrate specificity during infection with F. noatunenis.

Fig 1.

Francisella infection stimulates caspase-1-like activity in zebrafish leukocyte cultures. Zebrafish spleen and kidney cells were preincubated for 1 h with Ac-YVAD-CMK at 100 μg/ml or vehicle control and then stimulated with PBS or infected with Francisella at an MOI of 50 for 8 h. Cell-free supernatants or cell pellet lysates were assayed for caspase-1-specific activity using the fluorogenic caspase 1 substrate YVAD-AFC. Bars represent the mean rates of fluorogenic activity of 4 separate experiments ± standard errors. *, P < 0.05 compared to PBS control cells.

Francisella noatunensis causes processing and secretion of zebrafish IL-1β.

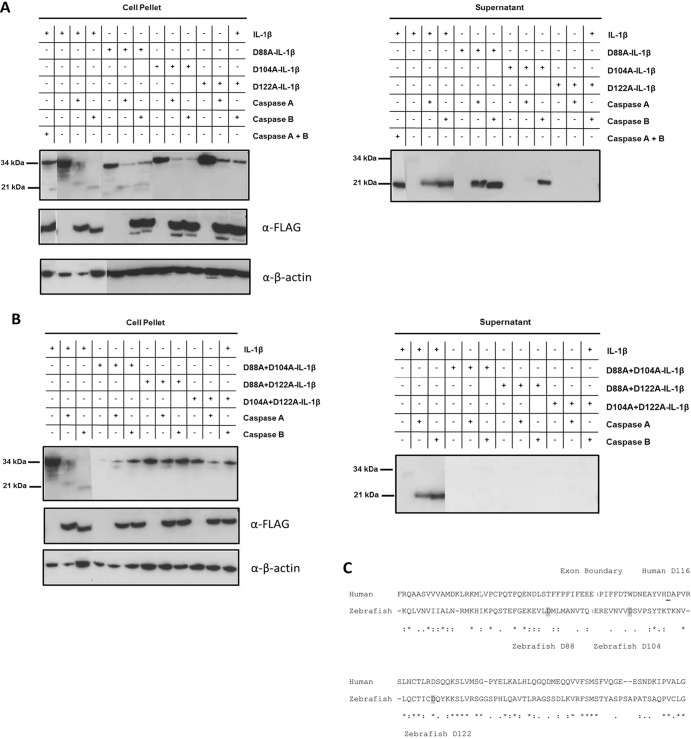

To investigate whether Francisella infection in zebrafish results in IL-1β processing and secretion as in mammals (6), we generated affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies against zebrafish IL-1β. We found that full-length (pro-IL-1β) and processed forms of zebrafish IL-1β were detected in primary leukocytes infected with F. noatunensis but not in mock-infected cells or cells challenged with heat-killed bacteria (Fig. 2A). In the cell-free culture supernatant, the full-length pro-IL-1β of ∼30.5 kDa, along with a partially processed form of approximately 28 kDa and a prominent, fully processed form of approximately 18 kDa, was detected from Francisella-infected cells. The full-length form of IL-1β detected in the supernatant fraction likely represents protein released from apoptotic/dead cells rather than secreted cytokine. The cell pellet lysate, in contrast, did not contain the fully processed 18-kDa IL-1β. Caspase inhibitors were preincubated with the primary cells to determine the contribution of caspase activity to IL-1β processing. Notably, the caspase-1-specific inhibitor YVAD-CMK and the pancaspase inhibitor ZVAD-FMK decreased the amount of fully processed IL-1β secreted into the culture supernatant (Fig. 2B) but did not completely abolish processing, indicating either incomplete inhibition or processing by a protease which is not inhibited by caspase-specific inhibitors. The broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor zVAD may inhibit caspase-mediated cell death during ex vivo culture, thereby limiting proinflammatory stimulus and slightly decreasing the production of full-length IL-1β in these cultures. Processing of IL-1β to the 18-kDa form occurs concurrently or following secretion from the cell, as the 18-kDa form was not detected in the cell pellet lysates. In the cell pellet, Francisella infection increased pro-IL-1β protein levels, which were not notably decreased by caspase inhibition. Therefore, similar to the case in mammals, production of zebrafish pro-IL-1β is independent of caspase activity. Interestingly, the supernatant and cell pellet fractions each contained intermediate forms of IL-1β, suggesting intermediate steps in the processing of IL-1β. Since these forms are present in samples incubated with caspase inhibitors, these could represent forms of IL-1β processed by noncaspase proteases present either in the supernatant or in the cell cytoplasm.

Fig 2.

Francisella stimulates IL-1β synthesis, processing, and secretion in primary zebrafish leukocytes. IL-1β was immunoprecipitated from equal volumes of pooled cell-free culture supernatant or from cell lysates with equivalent total protein (BCA assay) using polyclonal IL-1β antisera and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using the same antisera. (A) Zebrafish spleen and kidney cells from 10 fish per condition were separately stimulated with PBS, F. noatunensis, or heat-killed F. noatunensis at an MOI of approximately 60 for 8 h. (B) Cells were preincubated for 1 h with Ac-YVAD-CMK at 185 μM, ZVAD-fmk at 20 μM, or vehicle control and then stimulated with PBS or F. noatunensis at an MOI of approximately 50 for 8 h. Western blots are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Zebrafish caspase 1 orthologs can process IL-1β.

Previously, two zebrafish caspases (caspases A and B) with homology to human inflammatory caspases 1 and 5 were identified in the zebrafish by Masumoto et al. (35). The catalytic domain of caspase A shares the highest identity with human caspase 1, while caspase B is most similar to human caspase 5 (54 and 57% amino acid similarity, respectively). Interestingly, both caspase A and caspase B have N-terminal pyrin (PYD) domains, a finding which contrasts with the N-terminal CARD domains of mammalian inflammatory caspases. Overexpression of caspase A and caspase B induces HEK293 cell death and leads to cleavage of caspase-1- and caspase-5-specific substrates, respectively, and caspase A, but not caspase B, interacts with the inflammasome adaptor protein ASC (35). Since these two caspases appear to be functional orthologs to inflammatory caspases 1 and 5, we tested their ability to process IL-1β. Both caspase A and caspase B were able to process and cause secretion of zebrafish IL-1β when expressed in HEK293 cells (Fig. 3A). Full-length protein was found in the cell pellet lysates, while processed protein was detectable primarily in the supernatant fraction, again indicating that processing and secretion of cytokine are concurrent. Caspase A processes IL-1β to approximately 24 kDa, which corresponds to roughly 20 kDa without the contribution of the V5-His epitope tag. Caspase B processed IL-1β to approximately 22 kDa, corresponding to 18 kDa without the epitope tag. When caspase A and caspase B are cotransfected, IL-1β is processed to the smallest, 18-kDa size, which is similar in size to the 18-kDa form observed in primary zebrafish cells (Fig. 2). Thus, these two zebrafish caspases can process IL-1β to sizes which correspond to those observed in primary spleen and kidney cells infected with F. noatunensis.

Fig 3.

Zebrafish caspases A and B can process IL-1β. HEK293 cells were transfected with a pcDNA3.1-V5-IL-1β construct alone or with pFLAG-CMV-caspase A or pFLAG-CMV-caspase B. (A) Wild-type V5-tagged IL-1β or constructs containing single point mutations of D to A at the indicated amino acid positions were compared. (B) Constructs with double mutations at the indicated amino acids were compared. At 20 h posttransfection, cell-free supernatant was collected, cells were lysed, and V5-IL-1β was immunoprecipitated from supernatant using an anti-V5 antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins from equivalent volumes of supernatants or equal total protein contents from lysates of cell pellets were detected by Western blotting with anti-V5 antibody. FLAG-caspase expression in cell lysates was verified with an anti-FLAG antibody, and equivalent protein loading was verified by blotting against β-actin. Composite blots are representative of 3 experiments. (C) Amino acid alignment of human (amino acids 60 to 177) and zebrafish (amino acids 58 to 174) IL-1β flanking the human IL-1β ICE site. The first exon boundary is indicated with a vertical line. The caspase 1 cleavage site of human IL-1β at D116 is underlined. The putative caspase cleavage sites in zebrafish IL-1β at amino acids D88, D104, and D122 are in gray.

Caspases cleave substrates at aspartic acid residues, and so to address the potential cleavage site(s) for caspase A and caspase B, aspartic acid (D) residues at amino acids 88, 104, and 122 in zebrafish IL-1β were mutated to alanine. All three aspartic acid residues are in relative proximity to where human IL-1β is cleaved by caspase 1 (Fig. 3C). Cleavage at these positions would result in processed forms of zebrafish IL-1β with approximate sizes corresponding to those observed in Fig. 2. Mutation of D88 does not prevent processing or secretion of IL-1β into the culture supernatant by either caspase A or caspase B (Fig. 3A), indicating that D88 is not a final caspase cleavage site. However, mutation of D104 prevents caspase A from processing IL-1β and causes caspase B to process IL-1β at an alternative site, possibly residue 88 (Fig. 3A). To confirm this finding, we tested a double mutant of IL-β with D-A mutations at positions 88 and 104. This prevented both caspase A and caspase B from processing IL-1β, indicating that caspase B can process IL-1β at both aspartic acid residue 88 and residue 104. When D122 is mutated to alanine, neither caspase A nor caspase B can process or cause secretion of IL-1β (Fig. 3), indicating that D122 is an important site in IL-1β for caspase-mediated processing. Double mutants of IL-1β at positions 122 and 88 and positions 122 and 104 as well as a triple mutant at all three positions (data not shown) confirm this finding. Based on these results, caspase A cleaves IL-1β at residues D104 and D122. Though caspase B requires D104 for normal processing at D122, caspase B can cleave IL-1β at D88, when D104 is mutated to an alanine. These results indicate that the caspase recognition and cleavage sites differ between caspase A and caspase B and that processing is dependent on more than one aspartic acid residue in the region of the cleavage site.

DISCUSSION

This study establishes that zebrafish IL-1β is processed during the course of F. noatunensis infection and that IL-1β is a substrate for two zebrafish inflammatory caspases, caspase A and caspase B. In mammals, the importance of regulating IL-1β activity is evidenced by the large number of inflammatory diseases that arise when this regulation fails, most of which are treatable by blocking the action of IL-1β with a receptor antagonist (9). Many of these disorders are linked to aberrant control of caspase-1-mediated IL-1β processing and secretion. Though human IL-1β was originally identified as an endogenous pyrogen, extensive research has revealed a wide range of inflammatory effects mediated by IL-1 cytokines, including the acute-phase response; activation of macrophages and subsequent secretion of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-6; activation of T, B, and NK cells; and, more recently, the induction of a Th17 bias for adaptive immunity (9, 42). Ectothermic vertebrates such as fish are not thought to be susceptible to fever, although they do mount an acute-phase response (19, 27). Thus, it was unclear whether the IL-1β regulatory mechanisms that exist in mammals might also be important in fish. IL-1β has been cloned from fish, amphibian, and bird species (reviewed in reference 23), and the vast majority of all nonmammalian sequences examined thus far lack the conserved caspase 1 cleavage site. Caspases cleave preferentially following aspartic acid residues, and the caspase 1 specificity is further determined by the amino acids directly surrounding the scissile bond (8). In mammals, caspase 1 cuts at a conserved aspartic acid residue (D) typically between residues 113 and 117, and the subsequent mature peptide (∼17 kDa) typically starts with an alanine (60). In alignments of IL-1β sequences across vertebrates, there is no obvious D residue immediately in this region for nonmammalian sequences and protease prediction tools do not predict caspase-1-mediated cleavage in this region. Despite this, earlier studies provide indirect evidence that nonmammalian IL-1β is processed by potential caspase orthologs owing to the bioactivity of artificially truncated recombinant IL-1β (13, 15) or through reports demonstrating processed forms of IL-1β in fish cell cultures (36, 46). However, the direct involvement of caspase-mediated processing of IL-1β has never been examined in fish. Therefore, we set out to determine whether IL-1β is processed during a proinflammatory pathogenic challenge in zebrafish and whether zebrafish inflammatory caspases are implicated in the processing of IL-1β.

Activated caspase 1 is typically secreted from cells through inflammasome sensing of “danger” or infection (33), so it was not surprising to find caspase-1-specific activity residing in the supernatant of zebrafish leukocyte cultures infected with F. noatunensis, rather than in the cell pellet fraction. Addition of the caspase-1-specific inhibitor YVAD-CMK inhibited a large part, but not all, of the caspase-1-like activity in the supernatant, implying incomplete inhibition. Although the concentration of inhibitor was very high (185 μM), it is possible that the inhibitor was not able to penetrate all the caspase-1-expressing cells in the dense mixed-cell cultures or that the amount of caspase 1 expressed during the 8-h infection period exceeded the capacity of the inhibitor. In any case, it is clear that F. noatunensis infection stimulates caspase-1-like-specific activity in zebrafish cell cultures derived from hematopoietic tissues.

We have previously shown that during in vivo infection with F. noatunensis in adult zebrafish, IL-1β is transcriptionally upregulated in the spleen and kidney (57). Here, we now show that IL-1β is upregulated at the protein level during ex vivo Francisella infection, with either live or heat-killed bacteria. As expected, IL-1β was essentially undetectable in naïve zebrafish cells, while infection with Francisella caused the accumulation of full-length IL-1β in the cell pellet, as well a partially processed form of approximately 24 kDa (Fig. 2A). The fully processed (18-kDa) form of zebrafish IL-1β was detected only in the culture supernatant of cells challenged with live bacteria. These findings are in agreement with a model where either live or heat-killed Francisella can stimulate cell surface or endosomal Toll-like receptors (TLRs), resulting in upregulation of IL-1β on the protein level. However, caspase activation and processing of the cytokine to a fully mature form require a second stimulatory signal provided only by bacteria able to escape to the cytosol of the cell (31). The addition of caspase-1-specific or pancaspase inhibitors did not substantially alter the amount of full-length or intermediate forms of IL-1β in the cell pellet, implying that a caspase is not responsible for cleavage of IL-1β into these forms (Fig. 2B). A similar pattern of cleavage, with a caspase-independent form of IL-1β (∼20 kDa), accumulates in the cell pellet of bone marrow-derived murine macrophages upon activation of the P2X7 receptor (45). Inhibition of caspase activity limited the amount of secreted IL-1β, consistent with concurrent caspase processing and secretion. The small amount of processed IL-1β detected in the supernatant from cells incubated with caspase inhibitors likely results from incomplete inhibition of caspase activity in mixed-cell populations, as seen in Fig. 1. The supernatant also contains an ∼28-kDa form of IL-1β that does not seem susceptible to caspase inhibition. Numerous proteases, including neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3, cathepsins G and D, granzyme A, and matrix metalloproteinases, can all cleave IL-1β to biologically active forms, although the exact cleavage sites differ (5, 18, 40, 51). Many of these proteases are associated with neutrophil granules and are present extracellularly during inflammation; therefore, these proteases could be responsible for cleaving full-length IL-1β released from dead cells into the 28-kDa form of IL-1β that we observe in the supernatant. In the cell pellet, the 22-kDa form of IL-1β could also result from intracellular processing by one of these alternative proteases, possibly a protease released by lysosomal rupture following Francisella egress to the cytosol.

The two zebrafish caspase 1 orthologs, caspase A and caspase B, as well as zebrafish ASC, were originally identified by Masumoto et al. in a search for homologs to the pyrin domain of human ASC (35). A key finding was that overexpression of caspase A or caspase B caused cell death, consistent with the known role of activated caspase 1 in a proinflammatory form of cell death called pyroptosis (4). In addition, caspase A, but not caspase B, associated with ASC (35). Caspase A and caspase B have catalytic domains that are homologous to those of inflammatory caspases, the major difference being that the two zebrafish caspase 1 homologs have N-terminal pyrin domains rather than the related CARD domains of mammalian inflammatory caspases. Inflammasomes are composed of pattern recognition receptors (NLRs and AIM), ASC, and caspase 1 through interaction of PYD and CARD domains (6). Although the putative zebrafish inflammatory caspases possess a PYD domain, they would still be expected to associate either directly or indirectly (via ASC) with zebrafish NLRs as zebrafish possess NLRs with CARD and PYD domains (14, 25, 50). Aside from the detection of Francisella by NLRs, AIM2 can recognize Francisella nucleic acid, resulting in the activation of the AIM2 inflammasome (6) in mammals. In silico searches for AIM2 in zebrafish did not reveal any apparent homologues containing either pyrin or IFI200 domains (J. D. Hansen, unpublished observation). Zebrafish, however, do encode another potential inflammatory caspase that is very similar (69% amino acid identity) to caspase B, called caspase B-like (NP_001139064). We attempted to clone caspase B-like from immune-stimulated cDNA but were unsuccessful, implying that “caspase B-like” is expressed at very low levels or not at all in spleen or kidney. Considering that caspase A and caspase B are the likely functional orthologs to mammalian inflammatory caspases, we coexpressed these caspases with IL-1β in HEK293 cells and found that caspase A and caspase B were able to process IL-1β to sizes consistent with those observed from primary leukocyte cultures. As expected, caspase activity is concurrent with secretion, as the majority of fully processed IL-1β was found in the culture supernatant. We were surprised to find that caspase B processed IL-1β as well as caspase A because its closest mammalian ortholog (human caspase 5, an inflammatory caspase) does not appear to process IL-1β (30). Substrates for caspase 5 other than caspase 5 itself and caspase 1 are not known (34), though caspase 5 strongly potentiates caspase-1-mediated IL-1β processing and is present in some inflammasome complexes (33). Since caspase 5 is upregulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation in human macrophages, it may play a role as an upstream activator of caspase 1, as is the case for the related murine inflammatory caspase 11 (34).

We show that the two inflammatory caspases, A and B, though both able to cleave zebrafish IL-1β, do so at different sites. Caspases contain a cysteine residue in their active site, which is responsible for substrate cleavage at specific tetrapeptide sites designated P4-P1, where P1 corresponds to the conserved aspartic acid residue itself. Since caspases cleave the scissile bond between D and the adjacent amino acid (P1′), we mutated likely aspartic acid residues in zebrafish IL-1β to test for caspase cleavage and thereby indirectly determine the cleavage sites for each of the two caspases. We found that caspase A, which appeared to process IL-1β at two distinct sites, requires both D104 and D122 for processing activity (Fig. 3A). Caspase B processes IL-1β at D122, though this processing requires D104 as well. When D104 is absent, caspase B processes IL-1β at the alternative D88 site. Thus, both caspase A and B require two recognition sites for normal processing: D122 plus D104 for caspase A and D122 plus D104 or D88 for caspase B. This was confirmed in double mutant constructs lacking both D104 and D88, D88 and D122, and D104 and D122, where, as expected, no processing occurs. These results demonstrate that caspases A and B have different and complex recognition and cleavage specificities. In silico prediction (www.casbase.org/casvm/server/index.html) of caspase-1-mediated cleavage does not readily predict caspase cleavage sites (P4-P1 motifs) in the IL-1β region susceptible to processing, thereby potentially expanding the definition of inflammatory caspase substrate sequences. Whether caspases A and B are differentially regulated by tissue- or cell-specific expression or transcriptional upregulation or whether they work synergistically or in concert with other proteases remains to be determined.

In summary, this study establishes that in response to infection with the bacterial pathogen F. noatunensis, zebrafish leukocytes express caspase-1-specific activity and IL-1β is processed from a 30-kDa form to ∼22- and 18-kDa forms. Processing of IL-1β occurs in parallel with secretion, indicating that the bioactivity of zebrafish IL-1β is regulated at the level of processing and secretion. In addition, two putative inflammatory caspases, zebrafish caspases A and B, were both able to process IL-1β, thus implying their participation in the processing of IL-1β. Taken together, this work implies that the basic facets of the inflammasome platform of immune activation are conserved across vertebrate phylogeny, thereby further positioning zebrafish as a potent model system for addressing the regulation of inflammation in vertebrate health and disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was supported under a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to L.N.V. and by U.S. Geological Survey base funding.

The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the U.S. Department of Interior or the U.S. Geological Survey of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 June 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Allen JP, Neely MN. 2010. Trolling for the ideal model host: zebrafish take the bait. Future Microbiol. 5:563–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barksby HE, Lea SR, Preshaw PM, Taylor JJ. 2007. The expanding family of interleukin-1 cytokines and their role in destructive inflammatory disorders. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 149:217–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reference deleted.

- 4. Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. 2009. Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:99–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bird S, et al. 2002. Evolution of interleukin-1beta. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 13:483–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Broz P, Monack DM. 2011. Molecular mechanisms of inflammasome activation during microbial infections. Immunol. Rev. 243:174–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coeshott C, et al. 1999. Converting enzyme-independent release of tumor necrosis factor alpha and IL-1beta from a stimulated human monocytic cell line in the presence of activated neutrophils or purified proteinase 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:6261–6266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Demon D, et al. 2009. Caspase substrates: easily caught in deep waters? Trends Biotechnol. 27:680–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dinarello CA. 2011. A clinical perspective of IL-1beta as the gatekeeper of inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 41:1203–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dinarello CA. 1997. Interleukin-1. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 8:253–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gavrilin MA, et al. 2006. Internalization and phagosome escape required for Francisella to induce human monocyte IL-1beta processing and release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:141–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guma M, et al. 2009. Caspase 1-independent activation of interleukin-1beta in neutrophil-predominant inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 60:3642–3650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gyorfy Z, Ohnemus A, Kaspers B, Duda E, Staeheli P. 2003. Truncated chicken interleukin-1beta with increased biologic activity. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 23:223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hansen JD, Vojtech LN, Laing KJ. 2011. Sensing disease and danger: a survey of vertebrate PRRs and their origins. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 35:886–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hong S, Zou J, Collet B, Bols NC, Secombes CJ. 2004. Analysis and characterisation of IL-1beta processing in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 16:453–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huising MO, Kruiswijk CP, Flik G. 2006. Phylogeny and evolution of class-I helical cytokines. J. Endocrinol. 189:1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huising MO, Stet RJ, Savelkoul HF, Verburg-van Kemenade BM. 2004. The molecular evolution of the interleukin-1 family of cytokines; IL-18 in teleost fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 28:395–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Irmler M, et al. 1995. Granzyme A is an interleukin 1 beta-converting enzyme. J. Exp. Med. 181:1917–1922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jensen LE, et al. 1997. Acute phase proteins in salmonids: evolutionary analyses and acute phase response. J. Immunol. 158:384–392 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jiang S, Zhang D, Li J, Liu Z. 2008. Molecular characterization, recombinant expression and bioactivity analysis of the interleukin-1 beta from the yellowfin sea bream, Acanthopagrus latus (Houttuyn). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 24:323–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joosten LA, et al. 2009. Inflammatory arthritis in caspase 1 gene-deficient mice: contribution of proteinase 3 to caspase 1-independent production of bioactive interleukin-1beta. Arthritis Rheum. 60:3651–3662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keller M, Ruegg A, Werner S, Beer HD. 2008. Active caspase-1 is a regulator of unconventional protein secretion. Cell 132:818–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koussounadis AI, Ritchie DW, Kemp GJ, Secombes CJ. 2004. Analysis of fish IL-1beta and derived peptide sequences indicates conserved structures with species-specific IL-1 receptor binding: implications for pharmacological design. Curr. Pharm. Des. 10:3857–3871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reference deleted.

- 25. Laing KJ, Purcell MK, Winton JR, Hansen JD. 2008. A genomic view of the NOD-like receptor family in teleost fish: identification of a novel NLR subfamily in zebrafish. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:42 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li H, Nookala S, Bina XR, Bina JE, Re F. 2006. Innate immune response to Francisella tularensis is mediated by TLR2 and caspase-1 activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 80:766–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin B, et al. 2007. Acute phase response in zebrafish upon Aeromonas salmonicida and Staphylococcus aureus infection: striking similarities and obvious differences with mammals. Mol. Immunol. 44:295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reference deleted.

- 29. Lopez-Castejon G, et al. 2008. Molecular and functional characterization of gilthead seabream Sparus aurata caspase-1: the first identification of an inflammatory caspase in fish. Mol. Immunol. 45:49–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Margolin N, et al. 1997. Substrate and inhibitor specificity of interleukin-1 beta-converting enzyme and related caspases. J. Biol. Chem. 272:7223–7228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Dixit VM, Monack DM. 2005. Innate immunity against Francisella tularensis is dependent on the ASC/caspase-1 axis. J. Exp. Med. 202:1043–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martin SA, Zou J, Houlihan DF, Secombes CJ. 2007. Directional responses following recombinant cytokine stimulation of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) RTS-11 macrophage cells as revealed by transcriptome profiling. BMC Genomics 8:150 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. 2002. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol. Cell 10:417–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Martinon F, Tschopp J. 2007. Inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes: master switches of inflammation. Cell Death Differ. 14:10–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Masumoto J, et al. 2003. Caspy, a zebrafish caspase, activated by ASC oligomerization is required for pharyngeal arch development. J. Biol. Chem. 278:4268–4276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mathew JA, et al. 2002. Characterisation of a monoclonal antibody to carp IL-1beta and the development of a sensitive capture ELISA. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 13:85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meeker ND, Trede NS. 2008. Immunology and zebrafish: spawning new models of human disease. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 32:745–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meijer AH, Spaink HP. 2011. Host-pathogen interactions made transparent with the zebrafish model. Curr. Drug Targets 12:1000–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mikalsen J, Colquhoun DJ. 25 September 2009. Francisella asiatica sp. nov. isolated from farmed tilapia (Oreochromis sp.) and elevation of Francisella philomiragia subsp. noatunensis to species rank as Francisella noatunensis comb. nov., sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.002139-0. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mizutani H, Schechter N, Lazarus G, Black RA, Kupper TS. 1991. Rapid and specific conversion of precursor interleukin 1 beta (IL-1 beta) to an active IL-1 species by human mast cell chymase. J. Exp. Med. 174:821–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reference deleted.

- 42. Netea MG, et al. 2010. IL-1beta processing in host defense: beyond the inflammasomes. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000661 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ottem KF, Nylund A, Karlsbakk E, Friis-Moller A, Kamaishi T. 2009. Elevation of Francisella philomiragia subsp. noatunensis Mikalsen et al. (2007) to Francisella noatunensis comb. nov. [syn. Francisella piscicida Ottem et al. 2008 syn. nov.] and characterization of Francisella noatunensis subsp. orientalis subsp. nov., two important fish pathogens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106:1231–1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Reference deleted.

- 45. Pelegrin P, Barroso-Gutierrez C, Surprenant A. 2008. P2X7 receptor differentially couples to distinct release pathways for IL-1beta in mouse macrophage. J. Immunol. 180:7147–7157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pelegrin P, Chaves-Pozo E, Mulero V, Meseguer J. 2004. Production and mechanism of secretion of interleukin-1beta from the marine fish gilthead seabream. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 28:229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Phelps HA, Neely MN. 2005. Evolution of the zebrafish model: from development to immunity and infectious disease. Zebrafish 2:87–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reference deleted.

- 49. Soto E, Fernandez D, Thune R, Hawke JP. 2010. Interaction of Francisella asiatica with tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) innate immunity. Infect. Immun. 78:2070–2078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stein C, Caccamo M, Laird G, Leptin M. 2007. Conservation and divergence of gene families encoding components of innate immune response systems in zebrafish. Genome Biol. 8:R251 doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Takenouchi T, et al. 2011. The activation of P2X7 receptor induces cathepsin D-dependent production of a 20-kDa form of IL-1beta under acidic extracellular pH in LPS-primed microglial cells. J. Neurochem. 117:712–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thornberry NA, et al. 1992. A novel heterodimeric cysteine protease is required for interleukin-1 beta processing in monocytes. Nature 356:768–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Traver D, et al. 2003. The zebrafish as a model organism to study development of the immune system. Adv. Immunol. 81:253–330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Trede NS, Langenau DM, Traver D, Look AT, Zon LI. 2004. The use of zebrafish to understand immunity. Immunity 20:367–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. van der Sar AM, Appelmelk BJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Bitter W. 2004. A star with stripes: zebrafish as an infection model. Trends Microbiol. 12:451–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. van de Veerdonk FL, Netea MG, Dinarello CA, Joosten LA. 2011. Inflammasome activation and IL-1beta and IL-18 processing during infection. Trends Immunol. 32:110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vojtech LN, Sanders GE, Conway C, Ostland V, Hansen JD. 2009. Host immune response and acute disease in a zebrafish model of Francisella pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 77:914–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Whyte SK. 2007. The innate immune response of finfish—a review of current knowledge. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 23:1127–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wittamer V, Bertrand JY, Gutschow PW, Traver D. 2011. Characterization of the mononuclear phagocyte system in zebrafish. Blood 117:7126–7135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zou J, Grabowski PS, Cunningham C, Secombes CJ. 1999. Molecular cloning of interleukin 1beta from rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss reveals no evidence of an ice cut site. Cytokine 11:552–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]