Abstract

Pathogenic species of the spotted fever group Rickettsia are subjected to repeated exposures to the host complement system through cyclic infections of mammalian and tick hosts. The serum complement machinery is a formidable obstacle for bacteria to overcome if they endeavor to endure this endozoonotic cycle. We have previously demonstrated that that the etiologic agent of Mediterranean spotted fever, Rickettsia conorii, is susceptible to complement-mediated killing only in the presence of specific monoclonal antibodies. We have also shown that in the absence of particular neutralizing antibody, R. conorii is resistant to the effects of serum complement. We therefore hypothesized that the interactions between fluid-phase complement regulators and conserved rickettsial outer membrane-associated proteins are critical to mediate serum resistance. We demonstrate here that R. conorii specifically interacts with the soluble host complement inhibitor, factor H. Depletion of factor H from normal human serum renders R. conorii more susceptible to C3 and membrane attack complex deposition and to complement-mediated killing. We identified the autotransporter protein rickettsial OmpB (rOmpB) as a factor H ligand and further demonstrate that the rOmpB β-peptide is sufficient to mediate resistance to the bactericidal properties of human serum. Taken together, these data reveal an additional function for the highly conserved rickettsial surface cell antigen, rOmpB, and suggest that the ability to evade complement-mediated clearance from the hematogenous circulation is a novel virulence attribute for this class of pathogens.

INTRODUCTION

Gram-negative alphaproteobacteria of the genus Rickettsia are small (0.3 to 0.5 μm by 0.8 to 1.0 μm), obligate intracellular organisms. Spotted fever group (SFG) rickettsiae, including Rickettsia conorii (Mediterranean spotted fever [MSF]), are pathogenic organisms transmitted to humans through tick salivary contents during the blood meal. Commensurate mortality rates have been reported to be as high as 32% in Portugal in 1997 (17). Once established in the host, SFG rickettsiae primarily infect the endothelial lining of the vasculature. Damage to target endothelial cells, especially in the lungs and brain, can result in the most severe manifestations of disease (77). Misdiagnosis of SFG Rickettsia infection is associated with severe disease outcomes, including acute renal failure, pulmonary edema, interstitial pneumonia, neurological pathology, and other multiorgan manifestations (63).

A major component of the rickettsial outer membrane (OM), rOmpB, has previously been demonstrated to mediate adherence to and invasion of host cells (13, 26, 75). rOmpB belongs to a family of Gram-negative proteins called autotransporters, which have a modular structure including a N-terminal secretion signal, central passenger domain, and C-terminal β-peptide (βp) (36). rOmpB is initially translated as a 168-kDa polypeptide and is cleaved at the OM to yield a 120-kDa surface-exposed passenger domain that remains loosely associated with the OM and a 32-kDa integral OM βp (27). The βp assumes a 12-stranded β-sheet-rich barrel confirmation that spans the bacterial OM, whereby the unfolded passenger domain is translocated from the periplasm to the extracellular milieu through the barrel pore (22). Despite a shared tertiary barrel shape, β-peptides contain various numbers of membrane-spanning strands and have been demonstrated to perform various functions, including porins, transporters, enzymes, and receptors (83).

Although Rickettsia species are exposed to blood during transmission both to and from the tick vector or potentially during dissemination, little attention has been paid to the potential antimicrobial effects of serum complement. Host complement is a key component of the innate immune system that includes both antimicrobial and proinflammatory properties (78, 79, 85). Complement consists of approximately 30 proteins, which together complete a cascade-like process starting from recognition of immunogens and results in direct microbial killing, inflammation, and enhancement of the adaptive immune reaction. Although complement can be initiated through various mechanisms, all molecular pathways converge at C3 deposition on a target surface and its subsequent conversion to an unstable protease called C3 convertase. This protease initiates the cascade for deposition of antimicrobial pore-like structure deemed the terminal complement complex (C5b-9 [TCC]) (35, 46, 48, 52, 59, 73). The direct microbial killing mechanism is quite robust in the absence of microbial countermeasures (42, 43, 52). In addition, the latter steps in complement activation produce major anaphlatoxins and result in opsonophagocytosis of the pathogen (1, 21, 23, 84).

We have previously demonstrated that R. conorii is resistant to serum complement in the absence of specific neutralizing antibodies (14). Antibody recognition of its cognate ligand on a bacterial surface and subsequent bacterial killing is likely attributable to the classical complement pathway, although other methods for complement activation cannot be completely eliminated. Interestingly, R. conorii incubated in nonimmune serum is not sensitive to the spontaneous complement activation associated with the alternative pathway. This bacterial phenotype resembles the natural host state where complement is intrinsically inhibited. Due to the strong pathology associated with aberrant complement activation, mammals encode for various fluid-phase and cell-associated regulators of complement (11, 42, 50, 85).

Factor H (fH) is a single peptide of ∼155 kDa that consists of 20 repetitive units of 60 amino acids that is described from structural examination as “beads on a string” (5, 19, 41, 54, 56, 58). Factor H and the transcriptional splice variant, FHL-1, have three major functions: (i) accelerate the decay of the alternative pathway (AP) complement 3 (C3) convertase (C3bBb), (ii) compete with factor Bb for access to C3b, and (iii) serve as a cofactor for factor I-mediated proteolytic inactivation of C3 (30, 55, 80, 82, 86). The normal host ligands of factor H include C-reactive protein (CRP), DNA, annexin II, and polyanionic polysaccharides (44, 57). While these ligands serve to protect the host from aberrant complement deposition, bacteria have frequently corrupted these host ligands for their own advantage. Streptococcus pyogenes (9, 34, 37, 39), S. pneumoniae (20, 53), Salmonella enterica (32), Yersinia spp. (6–8, 15), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (62, 67), N. meningitidis (45, 61, 66), Haemophilus influenzae (28), Borrelia burgdorferi (3, 31, 40), Treponema denticola (49), Echinococcus granulosus (18), and the human immunodeficiency virus (70–72) all bind the soluble AP inhibitors, factor H, or FHL-1. These bacteria therefore have an active mechanism for preventing AP activation and subsequent deleterious effects of complement.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

R. conorii Malish7 ompB fragments were amplified by PCR from a chromosomal preparation. The region encoding the rOmpB β-peptide was amplified using primers 5′-GGATCCACCTGAAGCTGGAGCAATACCG-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGGAAGTTTACACGGACTTTTAG-3′, BamHI and XhoI digested (restriction sites underlined), and subsequently inserted into similarly digested pEt22b to construct pYC6. The pYC6-encoded protein contains the translational fusion of the N-terminal Escherichia coli PelB signal sequence, the R. conorii rOmpB β-peptide, and the C-terminal His6 tag under the control of an IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible promoter. pMC014, which encodes for the R. conorii Sca2 β-peptide, was constructed similarly to pYC6 as described above using the pET22b vector and the primers 5′-AAGGATCCGGAAACTAGTATAACAGAGGGGTATGG-3′ and 5′-AACTCGAGCAAATTGACTTTTAGTTTAATAAGCCCT-3′.

Bacterial growth.

R. conorii Malish7 were propagated from Vero cells and purified as described previously (4, 13, 14). Briefly, infected Vero cell monolayers were lysed by needle and purified over a 20% sucrose cushion. Bacteria were stored at −80°C in 218 mM sucrose, 3.8 mM KH2PO4, and 4.9 mM l-glutamate (pH 7.2). The yielded bacteria were pure and free of host contamination as visualized by microscopy. E. coli BL21(DE3)(pYC6, pMC014, or pET22b) was grown overnight in Luria-Bertani medium (LB) plus 50 μg of carbenicillin/ml at 37°C from a single colony. The bacteria were diluted 1:10 in fresh medium, grown to optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5, and induced with 0.1 mM IPTG for 3 h at 37°C where appropriate.

Bacterial fractionation.

Approximately 107 PFU of R. conorii or 1.0 ml of a culture of E. coli BL21(DE3) at an OD600 of ∼1.0 harboring the appropriate plasmid was washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the total detergent soluble lysates were generated by incubating the bacteria in 200 μl of BPER II bacterial protein extraction reagent (Thermo Scientific/Pierce, Rockford, IL) containing 1× complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's directions. OM protein fractions were generated essentially as described previously (74). Briefly, 5.0-ml portions of induced and noninduced E. coli harboring pET22b or pYC6 (OD600 of ∼1.0) were harvested, resuspended in 1.0 ml of 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) containing 1× protease inhibitor cocktail, and then disrupted by sonication. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation, and soluble lysates were incubated at room temperature for 5 min with Sarkosyl (0.5% final concentration). The samples were then centrifuged at 100,000 × g to isolate the OMs, and the OM fractions were solubilized in 2× SDS-PAGE buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and then immunoblotted with rabbit anti-His6 antibody (Covance) and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). His6-reactive species were revealed by chemiluminescence and exposure to film.

Detection of factor H interaction with R. conorii.

Paraformaldehyde-fixed R. conorii was incubated in PBS or in a 50% normal human serum (NHS; human type AB; Lonza, Hopkinton, MA)-PBS mixture for 2 h at room temperature with shaking. Each sample was washed twice by centrifugation and suspension in PBS. In order to elute interacting proteins from the bacteria, the mixture was resuspended in a 1 M NaCl-PBS mixture, followed by incubation for 20 min. The remaining bacteria were removed by centrifugation. The final cell-free elution was subjected to SDS-PAGE for immunoblot determination of the presence of fH using goat anti-human fH (Complement Technology Inc., Tyler, TX) and donkey anti-goat-HRP (Sigma). For flow cytometric analysis, paraformaldehyde-fixed R. conorii were incubated in PBS, 10% NHS, or 50 μg of purified fH/ml for 1 h at 37°C with shaking. Each sample was washed twice by centrifugation and resuspended in PBS. fH deposition was detected with goat anti-fH (Complement Tech) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated rabbit anti-goat antibody (Molecular Probes). Then, 5 μg of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole)/ml was added to distinguish the bacteria from background events. The samples were analyzed with an LSR-II cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; 488-nm excitation, 530/30-nm emission) and DAPI (325-nm excitation, 450/50-nm emission) fluorescence settings. Analysis of fH deposition was predicated upon DAPI positivity. All samples were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Serum sensitivity assay.

R. conorii from Vero cell purified stocks were resuspended in PBS and aliquoted to a final mixture of 100% PBS, 50% NHS-PBS, or 50% fH-depleted human serum (fHDplHS; Comptech)-PBS. Each of these mixtures was incubated for 1 h at 37°C with rotation, followed by centrifugation and recovery in ice-cold brain heart infusion medium. These final suspensions were titered as described previously (14) to determine the viable R. conorii remaining. All values are expressed as percentage of bacteria present after incubation with serum samples as a function of those incubated only in PBS. E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pET22b or pYC6 was grown as described above and induced with 0.1 mM IPTG (+IPTG) or left uninduced (−IPTG). Bacteria were diluted and washed in PBS and then approximately 5 × 106 CFU were resuspended in 200 μl of PBS or 30% NHS-PBS, followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C with rotation. After incubation, the samples were serially diluted in PBS and then plated on LB agar plates to determine the recovered CFU. The data are presented as the number of bacteria recovered in PBS and 30% NHS-PBS after the 1-h incubation period and plotted on a logarithmic scale. Independent triplicate samples were processed for each experimental condition, and the experiment was repeated a minimum of three times.

Complement component deposition on R. conorii.

R. conorii from Vero cell purified stocks was resuspended in PBS and aliquoted into a final mixture of PBS, 50% NHS-PBS, or 50% fHDplHS-PBS. Each of these mixtures was incubated for 1 h at 37°C with rotation, followed by centrifugation, washing in PBS, and suspension in 4% paraformaldehyde. Samples were split for flow cytometric analysis of C3 or C5b-9 deposition. C3 was detected with FITC-conjugated goat (Fab′) anti-human C3 (Protos Immunoresearch, Burlingame, CA). C5b-9 was detected with mouse anti-polyC9 (membrane attack complex [MAC]; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody. Flow cytometric analysis was performed as described above.

fH immunoprecipitation.

Whole-cell soluble protein lysates were incubated with 1.25 μg of purified human fH (Comptech) overnight at 4°C, and complexes were captured using goat anti-human fH sera (1:100 dilution) and protein G-Sepharose. Immunoprecipitates were separated on SDS-PAGE and either stained with Coomassie blue or transferred to nitrocellulose and immunoblotted with goat anti-human fH antibody (1:5,000) plus HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (1:5,000) or with rabbit anti-His6 antibody (1:1,000) plus HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000). Reactive species were revealed by Super Signal West Pico chemiluminescent substrates and exposure to film. Protein bands of interest were excised from the gel and analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Protein modeling.

β-Peptide alignments from Rickettsia spp. were performed using the CLUSTAL W function in MacVector software (MacVector, Cary, NC) using the input accession sequences AAD39533 (R. conorii), NP_221064 (R. prowazekii), YP_067640 (R. typhi), YP_001495174 (R. rickettsii), and AFC75259 (R. parkeri). The rOmpB β peptide consisting of amino acids 1335 to 1655 of the full-length peptide sequence was processed by the Phyre protein structural prediction server (38, 76). Secondary structure predictions were estimated using the Phyre output. The Phyre algorithm yielded multiple rOmpB βp models based on crystal structures of autotransporter EstA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Protein Data Bank [PDB] no., 3KVN), the precleavage structure of the autotransporter EspP from Escherichia coli O157:H7 (PDB, 3SLJ), the translocator domain of autotransporter NalP from Neisseria meningitidis (PDB, 1UYN), and the beta domain of the Bordetella pertussis autotransporter BrkA (PDB, 3QQ2). The final model was based on the EstA structure and was modeled with 100% confidence and 96% coverage. Likely membrane localization and surface exposure was determined by modeling the hydrophobic interfaces of the transmembrane β-strands based on Jmol analysis (Jmol is an open-source Java viewer for chemical structures in three dimensions [http://www.jmol.org/]).

RESULTS

R. conorii binds complement factor H.

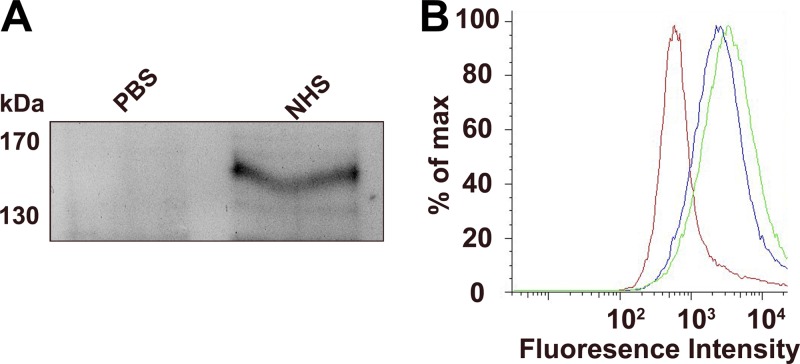

Having previously shown that R. conorii is resistant to complement-mediated killing in NHS (14), we sought to identify the bacterial mechanism of resistance. We hypothesized that rickettsiae would bind one of the soluble complement regulatory proteins found in serum. Of the most abundant complement regulating proteins found in serum, factor H (fH) has previously been shown to interact with various bacterial ligands (reviewed in reference 24). To determine whether this interaction occurs in R. conorii, we incubated bacteria with NHS and queried for the association of complement fH. As shown in Fig. 1A, we detected a salt-sensitive interaction between fH and R. conorii when incubated in NHS but not in PBS by immunoblot. To further confirm this interaction, we incubated R. conorii with PBS, 10% NHS, or 50 μg of purified fH/ml and subsequently queried for the presence of fH on the surface of the bacteria by flow cytometry. The fluorescence associated with fH binding to the surface of the bacteria significantly increases when incubated with either NHS or purified human fH (Fig. 1B). Taken together, these experiments confirm that R. conorii interacts with fH.

Fig 1.

R. conorii interacts with complement factor H. (A) R. conorii was incubated with PBS or 50% NHS. After washing, interacting serum proteins were eluted from the bacteria with 1 M NaCl. The cell-free elutions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and anti-fH immunoblotting. A 155-kDa fH-reactive species is present after NHS incubation with R. conorii. Sizes are indicated in kilodaltons (kDa). (B) R. conorii were incubated with PBS, 10% NHS, or 10 μg of purified factor H/ml. After washing, the fH deposition on the bacteria was detected by flow cytometric analysis of fluorescent anti-fH deposition. All events shown were contingent upon the presence of DNA (as demonstrated by DAPI staining), which represented rickettsiae. Red, PBS; green, 10% NHS; blue, 50 μg of fH/ml.

fH binding protects R. conorii from complement-mediated killing.

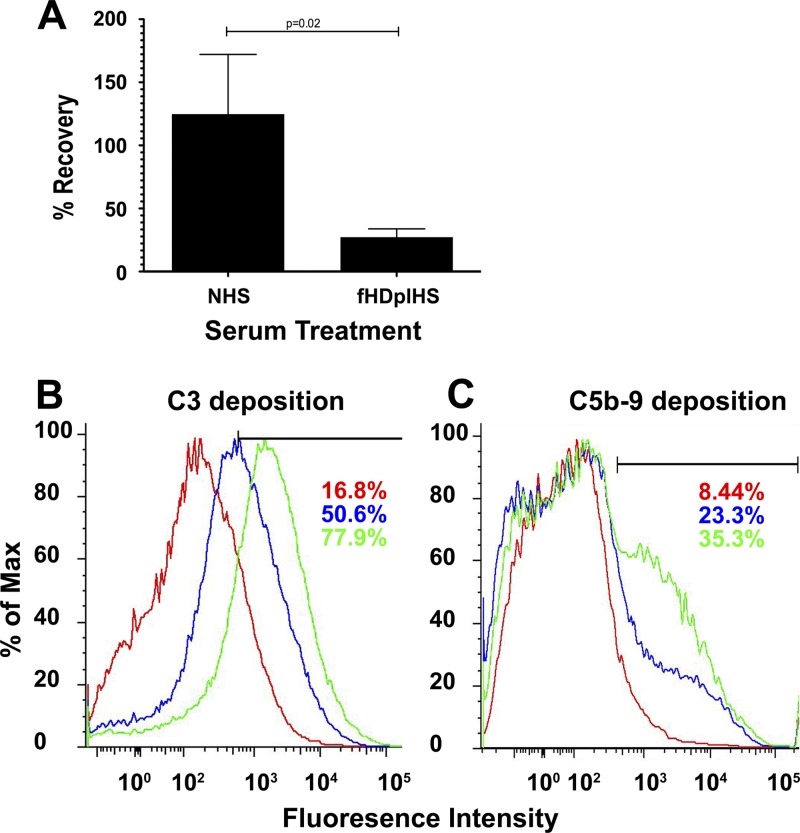

To determine whether fH association can be a mechanism of resistance to alternative pathway (AP) complement, we incubated R. conorii with PBS, NHS, or factor H-depleted human serum (fHDplHS) and determined the titer of the surviving R. conorii. Depletion of factor H from NHS results in bacterial killing, since only 27% of the rickettsiae survive incubation in fHDplHS compared to incubation in NHS (Fig. 2A). These results demonstrate that association of R. conorii with human fH promotes inhibition of AP and contributes to R. conorii survival in serum.

Fig 2.

Association with factor H promotes R. conorii resistance to complement-mediated killing. (A) R. conorii was incubated in 50% NHS or factor H-depleted human serum (fHDplHS), followed by quantitation of viable bacteria remaining. Values are expressed as the percentage of bacteria recovered compared to the bacteria incubated in PBS. The data represent three reactions for each condition and a minimum of three repetitions. P values are derived from unpaired Student t test. (B and C) Bacteria incubated with PBS (red), NHS (blue), or fHDplHS (green) were analyzed by flow cytometry for deposition of C3 (B) or the bactericidal MAC (C5b-9) (C) using fluorescently conjugated antibodies. Incubation of the bacteria in fHDplHS (green) results in more deposition of C3 and C5b-9 than NHS (blue) or PBS (red). Complement deposition is also demonstrated by an increase in the percentage of bacteria that have a fluorescence signal higher than the PBS-treated control. A total of 100,000 bacteria were analyzed for each histogram. The bars in panels B and C demarcate the data used for the area-under-the-curve statistical analysis. Sizes are indicated in panels A and C in kilodaltons (kDa).

Factor H binding prevents C3 and MAC deposition.

In mammals, fH inhibits AP-complement by disrupting the C3 convertase and by serving as a cofactor for factor I-mediated proteolysis (55, 82). As such, the fH activity can be queried by examining the latter steps of complement activation, including C3 and membrane attack complex (MAC; C5b-9) deposition on the bacteria. In order to confirm that normal fH-mediated functions are occurring at the rickettsial surface, we queried for complement activation in the presence of serum. R. conorii was incubated with PBS, NHS, or fHDplHS, followed by washing and fixation. As shown in Fig. 2B, cytometric analysis of the fluorescence demonstrated that C3 deposition on the rickettsial surface was significantly increased in fHDplHS compared to NHS or in the absence of any complement (PBS). The mean fluorescence values were as follows: PBS, 1,103; NHS, 1,936; and fHDplHS, 3,776, with a correlative increase in the percentage of bacteria exhibiting a fluorescence reading larger than the upper limit of the PBS control. Multicomponent analysis of 10,000 bins representing NHS and fHDplHS histograms indicates T(X) value of 795, whereby a value T(X) > 4 implies that the two distributions are different, with a P < 0.01. Similarly in Fig. 2C, the deposition of the MAC (C5b-9) occurred slightly more often in the bacteria exposed to fHDplHS compared to rickettsiae incubated in NHS. The mean fluorescence values were as follows: PBS, 1,250; NHS, 2,330; and fHDplHS, 2,709, with a correlative increase in the percentage of bacteria that demonstrate fluorescence values larger than the upper limit of the PBS control. In addition, the T(X) value for the comparison of NHS and fHDplHS is 125. Of note, only a portion of the bacteria treated with fHDplHS demonstrate an increase in MAC deposition. This is to be expected considering depletion of factor H does not result in complete bacterial killing (Fig. 2A). Taken together, these data indicate that R. conorii interact with human fH to prevent complement activation and subsequent deposition of the antibacterial MAC.

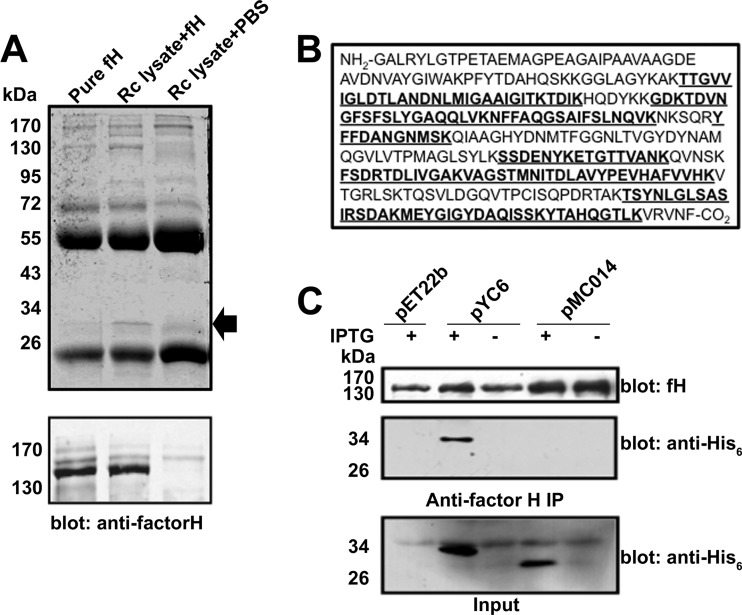

The rOmpB β-peptide interacts with factor H.

To determine which rickettsial protein(s) interact with fH, we incubated whole-cell R. conorii detergent soluble lysate with purified fH, immunoprecipitated fH and any interacting proteins using anti-fH antibody, separated the immune complexes by SDS-PAGE, and stained the gel using Coomassie blue. As shown in Fig. 3A (upper panel), we identified a single prominent protein with an apparent molecular mass of 32 kDa in immunoprecipitates containing R. conorii lysate and purified fH, but not in other control samples. Identical samples were immunoblotted with anti-fH antisera to determine the efficacy and specificity of the immunoprecipitation reaction (lower panel). We excised the factor H coimmunoprecipitating band and performed tandem mass spectrometry protein sequencing. As shown in Fig. 3B, the protein sequence analysis yielded peptides (indicated in boldface) corresponding to the R. conorii rOmpB C-terminal β peptide domain with a 43.3% amino acid coverage (139/321 amino acids). To confirm that rOmpB βp was truly interacting with factor H, we created a plasmid, pYC6, which encodes for the rOmpB βp with a C-terminal His6 tag. To control for putative nonspecific interactions with other rickettsial OM proteins, we also constructed a plasmid, pMC014, which encodes for the Sca2 βp. E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring the empty vector pEt22b, pYC6, or pMC014, were induced to make protein with the addition of IPTG. Whole-cell protein lysates from these bacteria were incubated with fH, and subsequently fH immunoprecipitation was performed. As shown in Fig. 3C (middle panel), an anti-His6 reactive band of the appropriate molecular mass coimmunoprecipitated when the rOmpB βp was produced (pYC6 + IPTG) but not when the Sca2 βp was made (pMC014 + IPTG). The efficacy of the anti-fH immunoprecipitation reaction and the expression of each indicated recombinant protein was verified by immunoblot analysis (upper panel and lower panels, respectively, in Fig. 3C). These results demonstrate that the R. conorii rOmpB βp is sufficient to interact with factor H.

Fig 3.

rOmpB β-peptide binds factor H. (A) The indicated proteins were incubated, immunoprecipitated with goat anti-human fH antibody, separated on SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie blue (upper panel). The arrow indicates the band that only coimmunoprecipitated when both fH and rickettsial lysate were present and was excised for analysis by mass spectrometry. The efficacy of the fH immunoprecipitation was verified by Western blotting (lower panel). (B) Protein sequencing of the excised band yielded peptide sequences (indicated in boldface) corresponding to the β-peptide (βp) of the autotransporter protein rOmpB. Amino acid sequence coverage of the rOmpB βp was 43.3%. No peptides were recovered from the remaining portion of rOmpB. Sizes are indicated in kilodaltons (kDa). (C) E. coli BL21 harboring the empty vector pEt22b, plasmid encoding for the rOmpB βp (pYC6), or control plasmid encoding for the Sca2 βp (pMC014) was induced with IPTG. Total detergent soluble lysates from these bacteria were incubated with purified fH and subsequently subjected to anti-fH immunoprecipitation. fH immunoprecipitated equally from the indicated samples (upper panel). A His6-reactive species only coimmunoprecipitated with fH upon expression of the rOmpB βp (middle panel). Total protein lysates from the indicated samples were analyzed by Western immunoblotting to confirm recombinant protein expression (bottom panel, input).

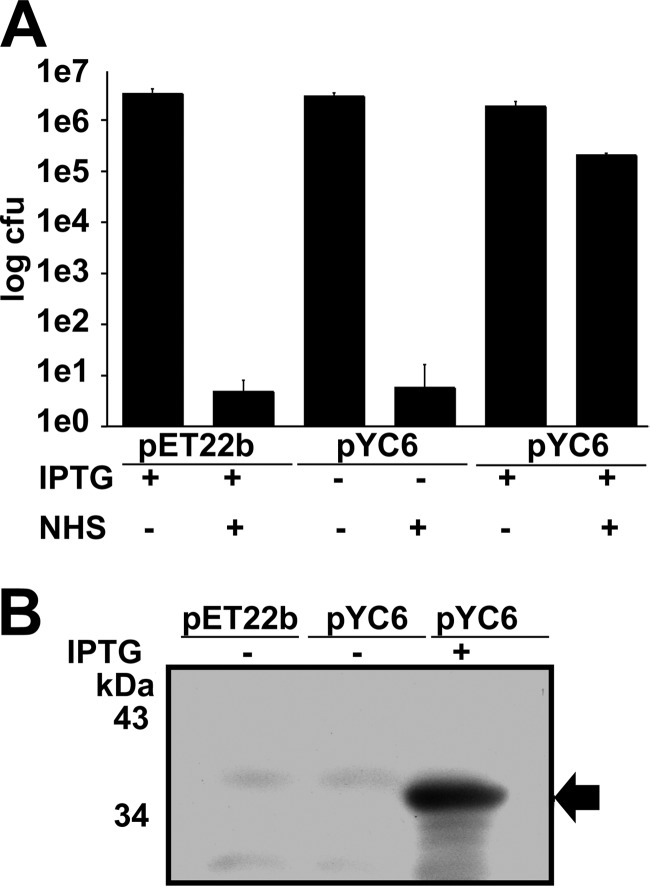

rOmpB βp mediates serum resistance.

We had shown that rOmpB can interact with fH; however, we still needed to determine whether the expression of rOmpB βp is sufficient to mediate serum resistance. Serum-sensitive E. coli strain BL21(DE3) was transformed with pYC6 or the empty parent vector, pEt22b. Bacteria were left uninduced (−IPTG) or induced (+IPTG), suspended in PBS or in PBS containing 30% NHS, and assayed for survival after 1 h of incubation. As shown in Fig. 4A, E. coli BL21(DE3) containing pEt22b and uninduced (pYC6, −IPTG) were sensitive to NHS, experiencing ∼6-log10 killing (1:1,000,000 survival). In contrast, expression of the rOmpB βp (pYC6, +IPTG) yields strong resistance to complement-mediated killing. We further confirmed the expression of the rOmpB βp at the OM of induced E. coli using anti-His6 antibody immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these data confirm that expression of the rOmpB βp is sufficient to mediate serum resistance in a manner that correlates with factor H binding.

Fig 4.

Expression rOmpB βp is sufficient to mediate survival in human serum. (A) E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring empty vector (pEt22b) or pYC6 (rOmpB βp) was incubated in PBS or NHS and analyzed for serum survival. Uninduced bacteria (−IPTG) do not survive in NHS. (B) Western immunoblot analysis with anti-His6 antibody reveals that expression of rOmpB βp (arrow) at the OM correlates with the ability to survive in NHS.

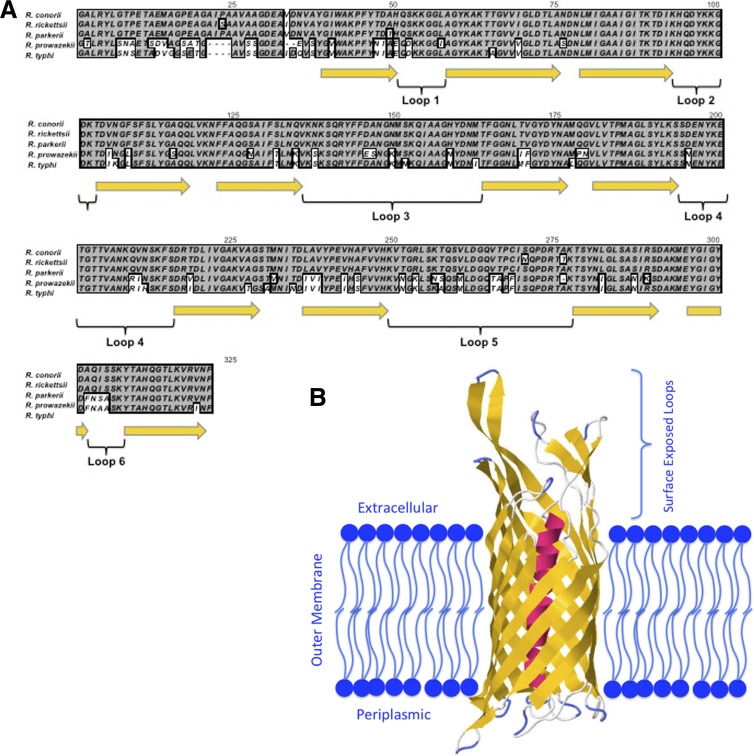

Analysis of rOmpB βp conservation and structure.

rOmpB βp is found in all pathogenic Rickettsia spp. sequenced to date (10). The βp amino acid sequence is remarkably well conserved, with an excess of 95% identity within the spotted fever group and >78% identity in the typhus group compared to the R. conorii sequence (Fig. 5A). Generally, conservation is seen throughout the amino acid sequence, with an exception being localized to the α-helix that protrudes through the center of the β-barrel. Based on Phyre modeling, we were able to predict the localization of the 12 transmembrane β-sheets (yellow) and exposed peptide loops of rOmpB βp (loops 1 to 6). The three-dimensional models generated are based on the reported β-barrel crystal structures from other Gram-negative bacteria, and all rOmpB βp models were extremely similar. In Fig. 5B, we model rOmpB βp based on EstA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This prediction had the highest confidence (100%) for the prediction of the rOmpB βp structure in the OM. Indeed, the hallmark membrane-spanning β-sheets form the barrel-like structure with lipophilic surfaces exposed to the bacterial OM. The six surface exposed cellular loops are highly polar and appear to protrude away from the outer leaflet of the OM.

Fig 5.

Analysis of rOmpB βp conservation and structure. (A) Alignment of rOmpB βp from diverse pathogenic Rickettsia spp. Indicated below the protein sequences are the predicted transmembrane β-sheets (yellow arrows) and six surface-exposed peptide loops (bracketed). (B) The model of rOmpB βp in the bacterial OM clearly demonstrates the β-barrel structure with 12 transmembrane β-sheets (yellow), a central α-helix that is the precleavage link to the passenger domain (red), and an approximation of the membrane localization (blue). The six extracellular loops protrude away from the OM and are readily exposed to the extracellular environment.

DISCUSSION

We have described here the first mechanism of serum resistance in the highly pathogenic bacterium, Rickettsia conorii. We have demonstrated that R. conorii interacts with human factor H (fH) and that this fH-R. conorii interaction is beneficial to the bacterium (Fig. 1 and 2). Thus, R. conorii recruitment of fH is advantageous to the bacterium and can be defined as an essential characteristic for survival in serum. Moreover, we have used fH coimmunoprecipitation to confirm that the rOmpB β-peptide (βp), but not a β-peptide from a related Sca protein (Sca2 βp), serves as a rickettsial protein that interacts with fH (Fig. 3). In addition, expression of rOmpB βp at the E. coli OM endows that bacterium with serum resistance (Fig. 4). Taken together, these data represent the first description as to how R. conorii possess inherent resistance to the antibacterial affects of serum complement.

The βp is the portion of the rOmpB autotransporter that remains imbedded within the rickettsial OM. Autotransporter β-peptides belong to a family of β-barrel membrane proteins with limited conservation in both the number of membrane spanning sheets and makeup of adjoining loops but share a highly conserved tertiary barrel-like membrane-spanning structure (reviewed in reference 22). rOmpB βp contains 12 transmembrane strands with six potentially exposed extracellular loops. Classically, a function associated with the βp is translocation of the associated autotransporter passenger domain across the OM, where it is subsequently liberated from the βp by an unknown mechanism (25, 27).

As stated above, rOmpB is processed in vivo from its native form to two independent polypeptides: the passenger domain and βp. The passenger domain remains loosely associated with the OM and is thought not to be covalently linked to the integral OM βp (25). We must therefore conclude that serum resistance is mediated in the areas proximal to the bacterial OM and not in the passenger domain-containing layer distal to the OM (12, 68). This is to be expected considering the propensity for complement deposition near a membrane and the fact that the MAC forms in conjunction with a targeted membrane (78).

A previous report aimed at identifying rickettsial/host interactions has identified the rOmpB βp as a protein that associates with an unknown ligand from endothelial cell extracts, suggesting that the βp may function as an adhesin (64). We describe here a additional function for the rOmpB βp, namely, the interaction with factor H and the promotion of serum resistance. These two binding functions can be completely complementary because many factor H-binding proteins in Gram-negative bacteria were previously identified as adhesins (16, 29, 60). However, in some species, factor H binding does not correlate with adherence (47). As such, future analysis will need to be performed to clarify the relationship between these functions of rOmpB βp.

Of the factor H-binding proteins from Gram-negative bacteria—Salmonella enterica Rck and Yersinia enterocolitica Ail—share a tertiary β-barrel structure similar to the predicted structure of rOmpB βp (7, 8, 16). These two other proteins have 8-stranded β-barrels compared to the 12 strands of rOmpB βp. A common structure of these three fH-binding proteins is the surface-exposed loops, which contain the fH attachment domains of both Rck and Ail (8, 16, 51). Using the Phyre protein modeling server (38), we were able to build an approximation of the orientation and location of the rOmpB βp in the rickettsial OM (Fig. 5). The central β-barrel consists of 12 β-strands that form a lipophilic outer surface with a central hydrophilic core containing the alpha-helical link to the passenger domain (passenger domain not shown). The extracellular loops are largely polar and appear to protrude some distance away from the outer leaflet of the OM. The model demonstrates that extracellular loops 3, 4, and 5 (from the N terminus) extend to a maximum of ∼35 Å from the bacterial surface. Due to the polarity and surface exposure of these peptide loops, we hypothesize that these are the peptides of rOmpB βp that interact with fH, as has been demonstrated in other Gram-negative pathogens.

It is of particular interest that the depletion of factor H from NHS resulted in an increase of only ∼73% killing of R. conorii (Fig. 2A). Similarly, fH depletion only increased complement component deposition on a subset of bacteria (Fig. 2B and C). When combined with the fact that nonpathogenic E. coli experience about six times the rate of killing under similar serum conditions (Fig. 4A), these results suggest that R. conorii must possess other attributes responsible for serum resistance. Various methods of acquired serum resistance have been demonstrated in invasive pathogens, including the acquisition of other soluble complement regulators, direct C3 inhibition, and the expression of complement-specific bacterial proteases (reviewed in reference 11). It is conceivable that Rickettsia spp. possess one or more of these serum resistance factors that function synergistically to promote resistance to complement-mediated killing. The identification of these factors is an ongoing task in this laboratory.

Factor H is a large protein that at the macromolecular level resembles “beads on a string” (5, 19, 41, 54, 56, 58). The 20 SCRs (short consensus repeats) of fH have been analyzed for association with its various natural substrates, including C3b, heparin, C-reactive protein, zinc, and sialic acid, as well as association with many proteins of bacterial origin (reviewed in references 11 and 65). Many bacterial fH-binding proteins associate with SCR5 to SCR7 or SCR19 to SCR20 of the polypeptide. Bacterial association with these sites promotes association with the cell surface while permitting the complement regulatory functions associated with C3b and factor I binding through SCR1 to SCR4. Whether R. conorii acquisition of fH functions in a similar manner is an area ongoing investigation.

The rOmpB βp is found in all pathogenic Rickettsia spp. sequenced do date, and these species infect an extremely wide range of mammalian hosts and blood-feeding arthropods (10, 81). The βp is impressively well conserved in rickettsiae that are separated by significant phylogeny and territory. It is conceivable that the strong positive selective pressure to maintain the integrity of rOmpB βp in all sequenced rickettsial species to date is in part due to the ability of this protein to promote resistance to serum killing in zoonotic and human hosts. Interestingly, among the spotted fever group, host diversity is quite extraordinary. It will therefore be intriguing to query the species specificity of fH binding (69). Since amino acid sequences and glycosylation patterns of fH differ from animal to animal (2, 33, 41), rOmpB βp may only bind fH from a certain segment of mammals. Although many variables have been associated with rickettsial host diversity (e.g., host availability, presence of arthropod vector, and immune state of the host), fH binding and subsequent complement resistance may influence host range of these severely pathogenic bacteria.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated here the first interaction between R. conorii and a soluble serum regulator of complement. This interaction with complement factor H yields strong resistance to serum, and the absence of this host effector results in a significant loss of bacterial viability in serum. These molecular interactions give us insight into the ability of R. conorii and potentially other rickettsial species to successfully infect humans while exposed to the complement system through tick-bite inoculation and dissemination throughout the infected individual. Selective inhibition of the rOmpB βp-factor H interaction could make R. conorii more sensitive to the antibacterial effects of serum and may have a positive effect on patient outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marissa Cardwell, Robert Hillman, Yvonne Chan, and Jess Leber for their assistance in experimental design and analysis and V. Thammavongosa and O. Schneewind for reagents.

This study is supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI-72606) to J.J.M. We acknowledge membership within the Region V Great Lakes Regional Center of Excellence in Biodefense and the Emerging Infectious Diseases Consortium (U54-AI-057153).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 May 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahearn JM, Fearon DT. 1989. Structure and function of the complement receptors, CR1 (CD35) and CR2 (CD21). Adv. Immunol. 46:183–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alexander JJ, Hack BK, Cunningham PN, Quigg RJ. 2001. A protein with characteristics of factor H is present on rodent platelets and functions as the immune adherence receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 276:32129–32135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alitalo A, et al. 2001. Complement evasion by Borrelia burgdorferi: serum-resistant strains promote C3b inactivation. Infect. Immun. 69:3685–3691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ammerman NC, Beier-Sexton M, Azad AF. 2008. Laboratory maintenance of Rickettsia rickettsii. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. Chapter 3:Unit 3A5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aslam M, Perkins SJ. 2001. Folded-back solution structure of monomeric factor H of human complement by synchrotron X-ray and neutron scattering, analytical ultracentrifugation, and constrained molecular modeling. J. Mol. Biol. 309:1117–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bartra SS, et al. 2008. Resistance of Yersinia pestis to complement-dependent killing is mediated by the Ail outer membrane protein. Infect. Immun. 76:612–622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Biedzka-Sarek M, Jarva H, Hyytiainen H, Meri S, Skurnik M. 2008. Characterization of complement factor H binding to Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:3. Infect. Immun. 76:4100–4109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Biedzka-Sarek M, et al. 2008. Functional mapping of YadA- and Ail-mediated binding of human factor H to Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:3. Infect. Immun. 76:5016–5027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blackmore TK, Fischetti VA, Sadlon TA, Ward HM, Gordon DL. 1998. M protein of the group A streptococcus binds to the seventh short consensus repeat of human complement factor H. Infect. Immun. 66:1427–1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blanc G, et al. 2005. Molecular evolution of rickettsia surface antigens: evidence of positive selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22:2073–2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blom AM, Hallstrom T, Riesbeck K. 2009. Complement evasion strategies of pathogens: acquisition of inhibitors and beyond. Mol. Immunol. 46:2808–2817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carl M, Dobson ME, Ching WM, Dasch GA. 1990. Characterization of the gene encoding the protective paracrystalline-surface-layer protein of Rickettsia prowazekii: presence of a truncated identical homolog in Rickettsia typhi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:8237–8241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chan YG, Cardwell MM, Hermanas TM, Uchiyama T, Martinez JJ. 2009. Rickettsial outer-membrane protein B (rOmpB) mediates bacterial invasion through Ku70 in an actin, c-Cbl, clathrin, and caveolin 2-dependent manner. Cell Microbiol. 11:629–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan YG, Riley SP, Chen E, Martinez JJ. 2011. Molecular basis of immunity to rickettsial infection conferred through outer membrane protein B. Infect. Immun. 79:2303–2313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. China B, Sory MP, N′Guyen BT, De Bruyere M, Cornelis GR. 1993. Role of the YadA protein in prevention of opsonization of Yersinia enterocolitica by C3b molecules. Infect. Immun. 61:3129–3136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cirillo DM, et al. 1996. Identification of a domain in Rck, a product of the Salmonella typhimurium virulence plasmid, required for both serum resistance and cell invasion. Infect. Immun. 64:2019–2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Sousa R, Nobrega SD, Bacellar F, Torgal J. 2003. Mediterranean spotted fever in Portugal: risk factors for fatal outcome in 105 hospitalized patients. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 990:285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diaz A, Ferreira A, Sim RB. 1997. Complement evasion by Echinococcus granulosus: sequestration of host factor H in the hydatid cyst wall. J. Immunol. 158:3779–3786 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. DiScipio RG. 1992. Ultrastructures and interactions of complement factors H and I. J. Immunol. 149:2592–2599 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duthy TG, et al. 2002. The human complement regulator factor H binds pneumococcal surface protein PspC via short consensus repeats 13 to 15. Infect. Immun. 70:5604–5611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ember JA, Hugli TE. 1997. Complement factors and their receptors. Immunopharmacology 38:3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fairman JW, Noinaj N, Buchanan SK. The structural biology of beta-barrel membrane proteins: a summary of recent reports. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21:523– 531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fallman M, Andersson R, Andersson T. 1993. Signaling properties of CR3 (CD11b/CD18) and CR1 (CD35) in relation to phagocytosis of complement-opsonized particles. J. Immunol. 151:330–338 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferreira VP, Pangburn MK, Cortes C. Complement control protein factor H: the good, the bad, and the inadequate. Mol. Immunol. 47:2187–2197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gilmore RD, Jr, Cieplak W, Jr, Policastro PF, Hackstadt T. 1991. The 120-kilodalton outer membrane protein (rOmpB) of Rickettsia rickettsii is encoded by an unusually long open reading frame: evidence for protein processing from a large precursor. Mol. Microbiol. 5:2361–2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gilmore RD, Jr, Joste N, McDonald GA. 1989. Cloning, expression and sequence analysis of the gene encoding the 120-kDa surface-exposed protein of Rickettsia rickettsii. Mol. Microbiol. 3:1579–1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hackstadt T, Messer R, Cieplak W, Peacock MG. 1992. Evidence for proteolytic cleavage of the 120-kilodalton outer membrane protein of rickettsiae: identification of an avirulent mutant deficient in processing. Infect. Immun. 60:159–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hallstrom T, et al. 2008. Haemophilus influenzae interacts with the human complement inhibitor factor H. J. Immunol. 181:537–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hammerschmidt S, et al. 2007. The host immune regulator factor H interacts via two contact sites with the PspC protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae and mediates adhesion to host epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 178:5848–5858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harrison RA, Lachmann PJ. 1980. The physiological breakdown of the third component of human complement. Mol. Immunol. 17:9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hellwage J, et al. 2001. The complement regulator factor H binds to the surface protein OspE of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8427–8435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ho DK, Jarva H, Meri S. 2010. Human complement factor H binds to outer membrane protein Rck of Salmonella. J. Immunol. 185:1763–1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Horstmann RD, Muller-Eberhard HJ. 1985. Isolation of rabbit C3, factor B, and factor H and comparison of their properties with those of the human analog. J. Immunol. 134:1094–1100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Horstmann RD, Sievertsen HJ, Knobloch J, Fischetti VA. 1988. Antiphagocytic activity of streptococcal M protein: selective binding of complement control protein factor H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:1657–1661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hu VW, Esser AF, Podack ER, Wisnieski BJ. 1981. The membrane attack mechanism of complement: photolabeling reveals insertion of terminal proteins into target membrane. J. Immunol. 127:380–386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jacob-Dubuisson F, Fernandez R, Coutte L. 2004. Protein secretion through autotransporter and two-partner pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694:235–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Johnsson E, et al. 1998. Role of the hypervariable region in streptococcal M proteins: binding of a human complement inhibitor. J. Immunol. 161:4894–4901 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. 2009. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat. Protoc. 4:363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kotarsky H, et al. 1998. Identification of a domain in human factor H and factor H-like protein-1 required for the interaction with streptococcal M proteins. J. Immunol. 160:3349–3354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kraiczy P, Skerka C, Kirschfink M, Brade V, Zipfel PF. 2001. Immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi by acquisition of human complement regulators FHL-1/reconectin and factor H. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:1674–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kristensen T, Tack BF. 1986. Murine protein H is comprised of 20 repeating units, 61 amino acids in length. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83:3963–3967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Laarman A, Milder F, van Strijp J, Rooijakkers S. Complement inhibition by gram-positive pathogens: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. J. Mol. Med. (Berlin) 88:115–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lambris JD, Ricklin D, Geisbrecht BV. 2008. Complement evasion by human pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:132–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Leffler J, et al. 2010. Annexin II, DNA, and histones serve as factor H ligands on the surface of apoptotic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285:3766–3776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Madico G, et al. 2007. Factor H binding and function in sialylated pathogenic neisseriae is influenced by gonococcal, but not meningococcal, porin. J. Immunol. 178:4489–4497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Martin DE, Chiu FJ, Gigli I, Muller-Eberhard HJ. 1987. Killing of human melanoma cells by the membrane attack complex of human complement as a function of its molecular composition. J. Clin. Invest. 80:226–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maruvada R, Blom AM, Prasadarao NV. 2008. Effects of complement regulators bound to Escherichia coli K1 and group B streptococcus on the interaction with host cells. Immunology 124:265–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mayer MM. 1981. Membrane damage by complement. Johns Hopkins Med. J. 148:243–258 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McDowell JV, Huang B, Fenno JC, Marconi RT. 2009. Analysis of a unique interaction between the complement regulatory protein factor H and the periodontal pathogen Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 77:1417–1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Meri S, Jarva H. 1998. Complement regulation. Vox Sang 74(Suppl 2):291–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Miller VL, Beer KB, Heusipp G, Young BM, Wachtel MR. 2001. Identification of regions of Ail required for the invasion and serum resistance phenotypes. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1053–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Muller-Eberhard HJ. 1986. The membrane attack complex of complement. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 4:503–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Neeleman C, et al. 1999. Resistance to both complement activation and phagocytosis in type 3 pneumococci is mediated by the binding of complement regulatory protein factor H. Infect. Immun. 67:4517–4524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nilsson UR, Mueller-Eberhard HJ. 1965. Isolation of beta If-globulin from human serum and its characterization as the fifth component of complement. J. Exp. Med. 122:277–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pangburn MK, Schreiber RD, Muller-Eberhard HJ. 1977. Human complement C3b inactivator: isolation, characterization, and demonstration of an absolute requirement for the serum protein β1H for cleavage of C3b and C4b in solution. J. Exp. Med. 146:257–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Perkins SJ, Haris PI, Sim RB, Chapman D. 1988. A study of the structure of human complement component factor H by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and secondary structure averaging methods. Biochemistry 27:4004–4012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Perkins SJ, et al. 2010. Multiple interactions of complement factor H with its ligands in solution: a progress report. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 703:25–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Perkins SJ, Nealis AS, Sim RB. 1991. Oligomeric domain structure of human complement factor H by X-ray and neutron solution scattering. Biochemistry 30:2847–2857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Podack ER, Tschopp J. 1982. Polymerization of the ninth component of complement (C9): formation of poly(C9) with a tubular ultrastructure resembling the membrane attack complex of complement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79:574–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Quin LR, et al. 2007. Factor H binding to PspC of Streptococcus pneumoniae increases adherence to human cell lines in vitro and enhances invasion of mouse lungs in vivo. Infect. Immun. 75:4082–4087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ram S, et al. 1999. The contrasting mechanisms of serum resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and group B Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Immunol. 36:915–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ram S, et al. 1998. Binding of complement factor H to loop 5 of porin protein 1A: a molecular mechanism of serum resistance of nonsialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Exp. Med. 188:671–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Raoult D, Roux V. 1997. Rickettsioses as paradigms of new or emerging infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:694–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Renesto P, et al. 2006. Identification of two putative rickettsial adhesins by proteomic analysis. Res. Microbiol. 157:605–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rodriguez de Cordoba S, Esparza-Gordillo J, Goicoechea de Jorge E, Lopez-Trascasa M, Sanchez-Corral P. 2004. The human complement factor H: functional roles, genetic variations and disease associations. Mol. Immunol. 41:355–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schneider MC, et al. 2006. Functional significance of factor H binding to Neisseria meningitidis. J. Immunol. 176:7566–7575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shaughnessy J, et al. 2011. Molecular characterization of the interaction between sialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae and factor H. J. Biol. Chem. 286:22235–22242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Silverman DJ, Wisseman CL., Jr 1978. Comparative ultrastructural study on the cell envelopes of Rickettsia prowazekii, Rickettsia rickettsii, and Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Infect. Immun. 21:1020–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Stevenson B, El-Hage N, Hines MA, Miller JC, Babb K. 2002. Differential binding of host complement inhibitor factor H by Borrelia burgdorferi Erp surface proteins: a possible mechanism underlying the expansive host range of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect. Immun. 70:491–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Stoiber H, Clivio A, Dierich MP. 1997. Role of complement in HIV infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15:649–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Stoiber H, Pinter C, Siccardi AG, Clivio A, Dierich MP. 1996. Efficient destruction of human immunodeficiency virus in human serum by inhibiting the protective action of complement factor H and decay accelerating factor (DAF, CD55). J. Exp. Med. 183:307–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Stoiber H, Schneider R, Janatova J, Dierich MP. 1995. Human complement proteins C3b, C4b, factor H and properdin react with specific sites in gp120 and gp41, the envelope proteins of HIV-1. Immunobiology. 193:98–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tegla CA, et al. 2011. Membrane attack by complement: the assembly and biology of terminal complement complexes. Immunol. Res. 51:45–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Thanassi DG, et al. 1998. The PapC usher forms an oligomeric channel: implications for pilus biogenesis across the outer membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:3146–3151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Uchiyama T, Kawano H, Kusuhara Y. 2006. The major outer membrane protein rOmpB of spotted fever group rickettsiae functions in the rickettsial adherence to and invasion of Vero cells. Microbes Infect. 8:801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. van den Berg B. 2010. Crystal structure of a full-length autotransporter. J. Mol. Biol. 396:627–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Walker DH, Gear JH. 1985. Correlation of the distribution of Rickettsia conorii, microscopic lesions, and clinical features in South African tick bite fever. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 34:361–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Walport MJ. 2001. Complement: first of two parts. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:1058–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Walport MJ. 2001. Complement: second of two parts. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:1140–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Weiler JM, Daha MR, Austen KF, Fearon DT. 1976. Control of the amplification convertase of complement by the plasma protein beta1H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 73:3268–3272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Weinert LA, Tinsley MC, Temperley M, Jiggins FM. 2007. Are we underestimating the diversity and incidence of insect bacterial symbionts? A case study in ladybird beetles. Biol. Lett. 3:678–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Whaley K, Schur PH, Ruddy S. 1976. C3b inactivator in the rheumatic diseases: measurement by radial immunodiffusion and by inhibition of formation of properdin pathway C3 convertase. J. Clin. Invest. 57:1554–1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wimley WC. 2003. The versatile beta-barrel membrane protein. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13:404–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Xia Y, et al. 1999. The beta-glucan-binding lectin site of mouse CR3 (CD11b/CD18) and its function in generating a primed state of the receptor that mediates cytotoxic activation in response to iC3b-opsonized target cells. J. Immunol. 162:2281–2290 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Zipfel PF, Skerka C. 2009. Complement regulators and inhibitory proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9:729–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zipfel PF, et al. 2002. Factor H family proteins: on complement, microbes, and human diseases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30:971–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]