Abstract

Vision in natural situations is different from the paradigms generally used to study vision in the laboratory. In natural vision, stimuli usually appear in a receptive field as the result of saccadic eye movements rather than suddenly flashing into view. The stimuli themselves are rich with meaningful and recognizable objects rather than simple abstract patterns. In this study we examined the sensitivity of neurons in macaque area V1 to saccades and to complex background contexts. Using a variety of visual conditions, we find that natural visual response patterns are unique. Compared with standard laboratory situations, in more natural vision V1 responses have longer latency, slower time course, delayed orientation selectivity, higher peak selectivity, and lower amplitude. Furthermore, the influences of saccades and background type (complex picture vs. uniform gray) interact to give a distinctive, and presumably more natural, response pattern. While in most of the experiments natural images were used as background, we find that similar synthetic unnatural background stimuli produce nearly identical responses (i.e., complexity matters more than “naturalness”). These findings have important implications for our understanding of vision in more natural situations. They suggest that with the saccades used to explore complex images, visual context (“surround effects”) would have a far greater effect on perception than in standard experiments with stimuli flashed on a uniform background. Perceptual thresholds for contrast and orientation should also be significantly different in more natural situations.

Keywords: primary visual cortex, natural vision, orientation selectivity, temporal aspects of visual processing, visual context and saccades

our visual system faces the daunting challenge of recognizing objects quickly and precisely as we explore complex natural scenes, yet most of what is known about the primate visual system is derived from experiments that greatly reduce the complexity of visual input and behavior (e.g., showing spots or bars on uniform backgrounds rather than complex scenes; enforced fixation rather than exploration by saccades). The differences between these experimental simplifications and the complexity of natural scenes and behavior raise the question: Does “naturalness” matter?

A number of labs have addressed this issue by independently exploring two questions: Does a natural stimulus produce different responses than a similar unnatural stimulus? And does a stimulus swept into view by a saccade give a different response than a flashed stimulus? For example, Gawne and Martin (2002) and Wurtz (1969) reported that the responses of primary visual cortex (V1) neurons are the same when a stimulus is flashed on the receptive field (RF) and when the stimulus enters the RF via saccade. However, recordings made from freely viewing animals suggest that there is something different about V1 responses when eye movements are allowed (Gallant et al. 1998; Livingstone et al. 1996). Furthermore, experiments in the LGN (Reppas et al. 2002) and in extrastriate visual cortex and parietal cortex (Duhamel et al. 1992; Kusunoki et al. 2000; Nakamura and Colby 2002; Tolias et al. 2001) show that eye movements can alter basic RF properties. Concerning natural images, several studies suggest that the statistics of natural images influence cortical responses (David et al. 2004; Kayser et al. 2003, 2004; Vinje and Gallant 2000), although characterization of what is “natural” is a complex issue.

The present study is motivated by previous research in our lab that suggests that scene complexity and eye movements affect V1 neuron responses, and that their effects interact nonlinearly (Huang and Paradiso 2005; MacEvoy et al. 2008). As a first approach to study the effects of saccades on complex backgrounds, Huang et al. (2005) introduced changes in background luminance or texture simultaneously with a bar flashed on the RF (meant to mimic in a fixation paradigm the changes in luminance and texture around a cell's RF that occur with a saccade). This stimulation paradigm significantly delayed orientation selectivity and contrast sensitivity. We ask in the present study whether the timing of feature selectivity is also altered in more natural visual situations. MacEvoy et al. (2008) manipulated both stimulus presentation mode and complexity and found an interaction between the two factors; this may account for why some studies find significant effects of saccades on cortical responses and other studies do not.

The approach we take here is to contrast the influence of stimulus complexity and saccades separately and together to improve our understanding of cortical coding in more natural visual situations. Motivated by sometimes conflicting previous work in the field, we set out to address a number of key questions: First, how do complex images and saccadic eye movements combine to sculpt V1 responses? Second, is feature selectivity delayed in natural vision as Huang et al. (2005) suggest? Third, can we reconcile our findings of different flash and saccade responses with previous reports of similar responses? Fourth, are the effects of saccades a result of image translation on the retina or of a corollary discharge signal associated with the eye movement? Finally, if saccades modulate V1 responses more on a natural background than on a uniform gray background, is this response difference particular to the background being a natural scene, or do similar unnatural backgrounds produce the same modulation?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All procedures used in these experiments conformed to National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Brown University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Further details on animal procedures are available in Huang and Paradiso (2005) and MacEvoy et al. (2008).

Animals and recordings.

Three monkeys (8.5–11 kg) were used. In an aseptic procedure, each animal was implanted with a titanium headpost. Two animals were implanted with a 19-mm-diameter cylinder over V1 for recording with conventional microelectrodes. We used epoxy-coated tungsten or glass-coated platinum/iridium electrodes (FHC, Bowdoinham, ME) or glass-coated tungsten electrodes (Alpha Omega Engineering). The other animal received a “Utah” array consisting of a 10 × 10 grid of 1-mm-long electrodes (Blackrock Microsystems). Potentials from conventional electrodes were amplified and recorded with a Power1401 converter and Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design). Electrode-array potentials were amplified and recorded with a Cerebus system (Blackrock Microsystems).

Animals were accustomed to sit comfortably in a primate chair (Crist Instruments, Hagerstown, MD) with their heads fixed and trained to saccade to and fixate a small red spot presented on a computer display for juice reward. Eye position was monitored by a 1-kHz infrared pupil-tracking system (EyeLink 1000, SR Research).

During an experiment, the animal sat with its head fixed facing a computer monitor in a diffusely lit room. Extracellular recordings were made of single-unit and multiunit activity from area V1 in one hemisphere of each animal. Neural activity was collected and included in our data set if it responded to a stimulus bar regardless of its preference for stimulus size, contrast, orientation, or movement. We recorded from 120 V1 units or multiunit sites from the three monkeys. Recordings were categorized as single unit or multiunit based on 1) compactness and separability of the spike shapes examined off-line in a PCA space and 2) compatibility or incompatibility of the recording interspike interval histograms (ISIHs) with the refractory period of cortical neurons. ISIHs of most of our recordings could be classified as follows: 1) ISIHs that increased monotonically or remained constant with decreasing ISI were considered to come from multiunit recordings, and 2) histograms that peaked somewhere between 2 and ∼15 ms and had sparsely occupied or empty bins for shorter intervals were categorized as single units. Not all the neurons recorded were used in this study; Data analysis, below, describes how experiments were screened, off-line, for recording stability and accuracy of the subjects' behavior. Our study includes results obtained from 74 units or multiunit sites recorded from 72 experiments. Of those 74 recordings, we classified 35 as single units, 29 as multiunits, and 10 as unclassified. As differences between single-unit and multiunit responses were not evident, we grouped them together in the analysis. For brevity, we use the terms “neuron” and “cell” to refer to single units and multiunits. The units/multiunits included in our study come from our three monkeys as follows: 46 from monkey P (single electrodes), 23 from monkey S (electrode array), and 5 from monkey Z (single electrodes). Their RF eccentricities ranged from 2.1° to 7.6° of visual field, with mean ± SD = 4.5 ± 1.2°.

Experimental procedures, conditions, and stimuli.

Experiments started by hand-mapping the RF of an identified neuron. With the monkey fixating the center of the screen, we defined the RF of a neuron by the location, size, width, orientation, and color (black or white) of a bar that produced the maximal response. The main procedure (described below) was then run with a stimulus with those optimal parameters. Each experiment lasted 2–4 h and collected data on 20–40 trials of each condition; different conditions and bar orientations were randomly interleaved. Visual stimuli were generated with the Psychophysics Toolbox (Brainard 1997; Pelli 1997) in MATLAB (The MathWorks). The visual display was an Iyama CRT (Master Pro514, model HM204DTA) running at 150 frames/s, with 1,024 × 768 pixel resolution, positioned 64 cm from the eyes of the subject and subtending 34° × 25° of visual angle.

A set of six stimulus conditions was used to assess the contribution of saccades and background type to the response (Fig. 1; the yellow circle represents the RF; it was not on the screen during the experiments). The Michelson contrast of the bar stimulus in the RF was set to 48% above or below the gray background, whichever gave the greater response. As an efficient way to estimate the orientation sensitivity of responses, recordings were made with the bar stimulus at the optimal orientation and at 60° counterclockwise from optimal. Orientation selectivity was not based on a comparison of responses to optimal and orthogonal stimuli because the orthogonal bars often gave no response.

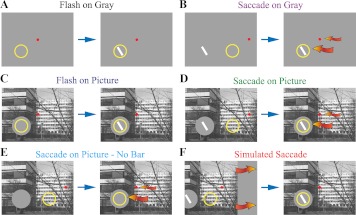

Fig. 1.

Visual stimulation and behavioral paradigms. Monkeys were trained to fixate and follow a small red spot on a computer display while a bar of light probed V1 neuron responses. Each frame in the figure depicts the image shown on the screen, the fixation spot, and the position of the receptive field (RF) on the screen (yellow circle; not displayed in the actual experiment). Each panel represents the 2 main epochs within a trial: before (left) and after (right) the stimulus onset or a saccade. A: Flash-on-Gray condition: monkey fixates a red spot in the center of the display (left), and a bar of light is then flashed in the RF (right). B: Saccade-on-Gray: monkey fixates a spot at a peripheral location while the bar is already present (left); the peripheral fixation spot disappears and a new one appears at screen center (right); the monkey makes a saccade to the screen center (small red arrow), bringing the RF onto the bar of light (large red arrow). C: Flash-on-Picture: a natural scene [taken from the van Hateren database (van Hateren and van der Schaaf 1998)] fills the screen, except for a circular buffer patch that encircles the RF; the animal fixates centrally; the stimulus bar is flashed on the buffer. D: Saccade-on-Picture: a natural scene fills the screen except for a circular buffer patch that will encircle the RF after the saccade; the bar is present in the buffer; the animal fixates peripherally (left); the peripheral fixation spot disappears and a new one appears at screen center (right); the monkey makes a saccade to screen center (small red arrow), bringing the RF onto the bar of light (large red arrow). The sizes of the buffer and the bar have been exaggerated for illustration purposes. In practice, the size of the bar was comparable to a small tree branch in the figure. The buffer radius was ∼1.3 times the length of the bar. E: Saccade-on-Picture-NoBar: control condition to test the response produced by the saccade itself; similar to D, but a bar of light was never presented in the buffer. F: Simulated-Saccade: monkey fixates the center of the display during the entire trial; the scene, buffer, and bar move, duplicating the retinal translation that occurs during a real saccade. All figures in this report use the color code established in the panel titles of this figure.

In the Flash-on-Gray condition (Fig. 1A), a trial began with a uniform gray visual display and a red fixation spot 5° to the left or right of center (not illustrated in Fig. 1). If the monkey acquired this peripheral fixation spot and maintained fixation for 300 ms, the red spot was extinguished and a new fixation spot turned on at the center of the screen (Fig. 1A, left). If the monkey moved its gaze to the central fixation spot within 300 ms, the stimulus bar was flashed in the RF (Fig. 1A, right) and remained on the screen for 0.3 s. If the monkey fixated the central fixation for a total of 0.5 s, a liquid reward was given.

The Flash-on-Pic condition (Fig. 1C) followed the same sequence of events as the Flash-on-Gray condition except that the background was a complex picture taken from the van Hateren database (van Hateren and van der Schaaf 1998). The mean luminance of the picture was matched to the luminance of the gray background in the Flash-on-Gray condition (16 cd/m2) as well as the mean luminance of the walls adjacent to the visual display in the testing room. To ensure that stimulation of the RF was identical in the Gray and Picture backgrounds, the stimulus bar was shown on a circular gray patch that we call a buffer. The buffer had the same luminance as the picture and gray backgrounds and a radius 1.25–1.3 times the length of the bar stimulus (Fig. 1C; for clarity, the sizes of the bar and the buffer are exaggerated in the figure).

The flash conditions were complemented by two saccade conditions. The important difference was that in the saccade conditions the RF bar stimulus was present before the animal made a 5° saccade to the center of the display. Thus the saccade brought the stimulus bar into the RF rather than a flash. In the Sac-on-Gray condition (Fig. 1B), the screen showed the homogeneous gray background, a peripheral fixation spot, and the stimulus bar (Fig. 1B, left). If the monkey acquired the peripheral fixation spot and maintained fixation for 300 ms, the red spot was extinguished and the central fixation spot was turned on (Fig. 1B, right). The bar remained present all this time. When the monkey moved its gaze to the central fixation spot (small red arrow), the RF moved onto the bar (large red arrow). If the animal fixated the central spot for 0.5 s, a liquid reward was given. The Sac-on-Pic condition (Fig. 1D) was identical to the Sac-on-Gray condition except that the background was a complex picture. As in the Flash-on-Pic condition, a buffer surrounded the bar stimulus and filled the RF.

In addition to the four primary conditions described above, several controls were run to address finer points. To determine the extent to which neural activity is influenced by visual stimulation during saccades, we included two no-bar control conditions; they were identical to the Sac-on-Gray and Sac-on-Pic conditions except that the RF bar was never shown on the screen. These conditions are referred to as “Sac-on-Gray-NoBar” (not illustrated) and “Sac-on-Pic-NoBar” (Fig. 1E).

To study the influence of visual input and internal signals during saccades, we included a “simulated saccade” condition (“Sim-Sac”; Fig. 1F). The goal was to duplicate, in a fixating animal, the pattern of image movement across the retina that resulted from an actual saccade. To do this, we sampled the eye position during saccades at intervals equivalent to the refresh rate of the video monitor (150 frames/s). The average samples across many saccades were used to create 5-frame movies that moved the scene with the time course of real saccades. In this condition, a trial began with a fixation spot at the center of the screen and the picture, buffer, and bar shown displaced 5° to the left or to the right (Fig. 1F, left). If the fixation point was acquired and held for 300 ms, the display contents (except for the fixation point) were shifted leftward or rightward by the 5-frame movie (red arrows), ending with the same position used in Flash-on-Pic and Sac-on-Pic trials (Fig. 1F, right).

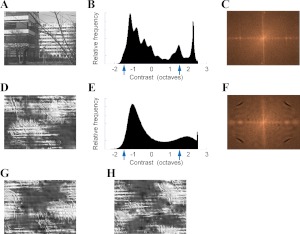

To test whether natural images have a unique effect on V1 activity, we compared responses in all Picture conditions shown in Fig. 1 when the background was either a natural or an “unnatural” scene. The unnatural background scenes were derived from van Hateren database (van Hateren and van der Schaaf 1998) images with the Portilla and Simoncelli texture-synthesis algorithm (Portilla and Simoncelli 2000). Examples of unnatural images synthesized from the natural image in Fig. 2A are shown in Fig. 2, D, G, and H. The synthesized unnatural images had approximately the same contrast distribution, spatial-frequency power spectrum, and anisotropies as the original image.

Fig. 2.

Background images used to assess the importance of naturalness in response modulation. A: natural image scene taken from the van Hateren database (van Hateren and van der Schaaf 1998). B: luminance histogram of image in A; arrows show the contrasts of the stimulus bars used to probe the response of the RF, either 50% above or below the mean luminance level of the image. C: normalized power spectrum of the original image; brighter indicates greater energy. Horizontal axis corresponds to horizontal spatial frequencies increasing from the center to the left and right borders. Vertical axis corresponds to vertical frequencies. Center corresponds to zero spatial frequency. D: synthetic “unnatural” image derived from the image in A with the texture-synthesis algorithm of Portilla and Simoncelli (2000). E: luminance histogram of the synthetic image in D. F: power spectrum of the synthetic image in D. G and H: 2 other “unnatural” images synthesized from A, with different initial seeds. The luminance histograms of the images in G and H are identical to E; their power spectra is identical to F.

Data analysis.

Recordings were screened off-line for spike stability and eye-fixation accuracy. Experiments were discarded if spike waveforms were not stable enough to obtain at least 20 trials of each stimulus condition. Individual trials were discarded if a corrective saccade was needed to foveate the postsaccade fixation point or if eye position was not stable within a 0.15°-radius window for all the conditions. The results reported here were obtained from 74 units or multiunit sites, recorded from 72 experiments.

We calculated peristimulus spike histograms of the response (PSTHs), using 5-ms-width bins. To compute average PSTHs from all the cells in our sample, we first normalized the PSTHs from all stimulus conditions in an experiment to the response peak elicited by the optimal-orientation bar in the Flash-on-Gray condition. Orientation selectivity was calculated as

| (1) |

where tj is the time of the jth 5-ms bin, relative to stimulus onset (in the Flash conditions) or to the end of a saccade (in the Saccade conditions); V0(tj) is the spike rate in the jth bin in response to an optimally oriented bar; and V60(tj) is the spike rate in response to a bar tilted 60° counterclockwise from the optimal orientation. We used a 60° instead of a 90° shift because, in preliminary experiments, many V1 neurons did not respond at all to orthogonal orientations.

Quantifying response timing and amplitude.

To quantify the response time course, we defined three epochs in each neuron's response (see exemplary PSTH in Fig. 3): prepeak (red bar), peak (green bar), and late phase (blue bar). Peak activity was measured by counting the spikes in the peak epoch (green), early and/or prepeak activity were measured in a 16-ms window preceding the Flash-on-Gray response peak time (red), and late activity was measured in the interval t = 100–200 ms (blue).

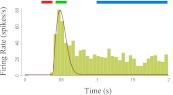

Fig. 3.

Temporal quantification of the neural response. The peristimulus time histogram (PSTH; vertical bars) shows a typical response of a V1 neuron to a bar flashed in its RF for 300 ms. The horizontal bars above the PSTH represent the time epochs used for quantitative analysis: prepeak (red), peak (green), and late (blue). The prepeak epoch (red) was defined for each neuron as a 16-ms window beginning at the minimum response latency across conditions. The peak epoch (green) was determined independently for each neuron and each condition by using an automatic procedure to estimate the peak time, its width, and the latency of the response (see materials and methods). The late epoch was defined as a fixed interval (t = 100–200 ms; blue bar) based on the end of the initial response transient of the grand average of all cells in our sample.

The peak time, width, and latency of the response were determined with an automated procedure that fitted a function to the spikes occurring after a flash or saccade brought the bar stimulus into the RF. Various strategies have been used previously to estimate response latency, but there is no accepted standard (Friedman and Priebe 1998). Because of our interest in following the temporal response dynamics in detail, we sought a single approach to measure the latency and the peak time of the response's initial transient. We did so by fitting a simple model to the initial response and using the parameters of the fitted model as indicators of the latency c and time to peak b of the initial-response transient (fitted curve in Fig. 3). The function used in the fit was the Rayleigh probability density function (Papoulis and Pillai 2002), in the following model:

| (2) |

where p0 represents the basal spike rate; R(t − c, b) is the Rayleigh probability density function; b determines the shape of the Rayleigh function and specifies the difference between the beginning and the maximum of the function (in our case, the time to peak); c represents the response latency; and t is the time relative to the stimulus onset time (in the Flash conditions) or to the end of a saccade (in the Saccade conditions). To avoid artifacts and losses of resolution introduced by the width and position of bins in a spike histogram, the model was fit directly to the spike times with the maximum-likelihood estimator (MLE; Eliason 1993). Only the initial peak of the response was fitted (in the Fig. 3 example, the domain was limited to 0 ≤ t ≤ 65 ms). Initial solutions were set by visually inspecting the PSTHs. Although our method can theoretically find latency and peak response times with no time-binning, its resolution is limited by the sampling rate of the signal acquisition system (0.06 ms of CED/Spike2 and 0.03 ms of Cerebus).

Our approach can be considered an extension of Friedman and Priebe (1998), with the following differences: 1) our method also estimates the peak time of the initial transient; 2) their method estimates the latency as the transition between two stationary stochastic processes (basal vs. response), but our model assumes that only the basal activity is stationary and that the response is continuously changing; and 3) their method takes PSTHs as inputs, which involve arbitrary binning, while ours operates on the raw spike times without binning.

Although we show PSTHs to illustrate our results, all quantitative analyses were done with the fitted-model numerical values of latency and amplitude measured from nonbinned spike times. All the statistics were performed on these bin-free numerical values. Data analysis was performed with Spike2, MATLAB, and Stata (StataCorp).

Defining stimulus onset time in saccade conditions.

Strictly speaking, it is impossible to equate stimulus onset time in flash and saccade conditions. In the flash condition the stimulus appears instantaneously within a static RF. In the saccade condition the stimulus enters the RF gradually before stopping. Furthermore, the movement of the stimulus on the retina is a function not only of the movement of the eye ball but also of the lens within the eye, which lags and then overshoots the movement of the ocular globe (Deubel and Bridgeman 1995a, 1995b). Therefore, following Deubel and Bridgeman (1995a) we defined the end of a saccade as the peak of the first overshoot in the eye-position trace provided by our optical eye tracker, and we corrected this time by the 3-ms delay resulting from the eye-tracker standard filter setting.

RESULTS

Effects of visual context and saccades on response timing and amplitude.

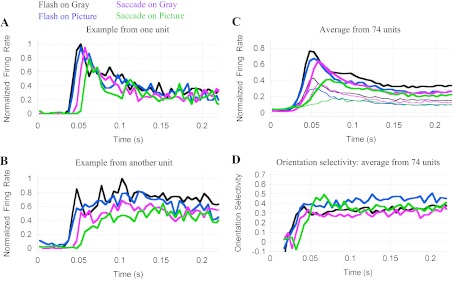

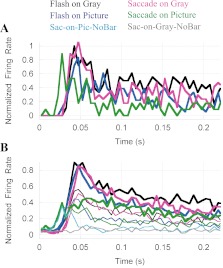

Across the four primary experimental conditions, V1 neurons show a diversity of latencies, magnitudes, and time courses (see examples in Fig. 4, A and B). In most cells, responses were of progressively lower amplitude and longer latency when moving from the Flash-on-Gray (black) to the Flash-on-Pic (blue), Sac-on-Gray (magenta), and Sac-on-Pic (green) conditions. In some cells, these changes were quite pronounced (Fig. 4B). Average responses across all neurons in our sample are shown in Fig. 4C, and mean values of different response parameters are given in Table 1. The thin traces in Fig. 4C show the responses to bar stimuli tilted 60° counterclockwise from optimal.

Fig. 4.

Dependence of V1 responses on the mode of stimulus presentation and the type of background image. A: response of 1 neuron to an optimally oriented bar in 4 different conditions: Flash-on Gray (black), Flash-on-Pic (blue), Sac-on-Gray (magenta), and Sac-on-Pic (green). In Flash conditions, t = 0 indicates stimulus onset; in Saccade conditions, t = 0 is the end of the saccade that brought the stimulus into the RF. Note the similarity of the Flash-on-Gray and Flash-on-Pic responses (black and blue) and the larger latency of the Sac-on-Gray (magenta) and especially the Sac-on-Pic (green) response. Responses were normalized to the peak response in the Flash-on-Gray condition (black). B: a neuron showing greater response amplitude reduction in the saccade conditions (magenta and green) compared with the cell in A. C: average responses from 74 V1 recording sites. Thick lines indicate responses to optimally oriented bar stimuli, and thin lines show responses to bars tilted 60° counterclockwise from optimal. Response latencies in Flash-on-Gray (black) and Flash-on-Picture (blue) conditions are similar; Sac-on-Gray (magenta) and Sac-on-Pic (green) conditions have progressively longer latencies. Response amplitude also decreases across conditions. Before averaging, all the responses from a particular cell were normalized to the Flash-on-Gray peak. The grand Flash-on-Gray average (black) is <1.0 because different cells have different latencies and time courses. The quantitative analysis summarized in Table 1 shows a mean peak value = 1 for the Flash-on-Gray condition because it used the peak values measured independently for each cell and each condition with the procedure described in Fig. 3 and materials and methods. The Sac-on-Pic response (green) exhibits a small, early increase of activity around 25 ms, found to come from a subset of neurons that fired to the movement of the background scene during saccades (see results and Fig. 5). D: mean orientation selectivity of the cells in our sample. For each condition, orientation selectivity rises following the average responses, peaks, and then exhibits a plateau for the rest of the response. The latency of the selectivity in different conditions follows the latencies of the average responses per condition. Three epochs of the orientation selectivity time course are of notice: the different latencies in each condition, the initial peak of the Sac-on-Pic response (green trace, around t = 60 ms; larger than the other 3), and the plateau corresponding to the late Flash-on-Picture response (blue trace, t > 100 ms; larger than the other conditions). These differences are discussed in results.

Table 1.

Latency, peak magnitude, and orientation selectivity of responses to different contexts and modes in which stimulus enters RF of V1 neurons

| Response Peak |

Late Response |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition (color used in figures) | Response Latency, ms | Peak Time, ms | Normalized amplitude | Orientation selectivity | Amplitude | Orientation selectivity |

| Flash-on-Gray (black) | 35 ± 8 | 50 ± 8 | 1 | 0.35 ± 0.3 | 0.43 ± 0.2 | 0.40 ± 0.3 |

| Flash-on-Picture (blue) | 36 ± 8 | 52 ± 9 | 0.92 ± 0.2 | 0.43 ± 0.3 | 0.35 ± 0.2 | 0.51 ± 0.3 |

| Sac-on-Gray (magenta) | 42 ± 10 | 57 ± 10 | 0.85 ± 0.2 | 0.33 ± 0.3 | 0.33 ± 0.2 | 0.35 ± 0.3 |

| Sac-on-Picture (green) | 46 ± 13 | 64 ± 13 | 0.59 ± 0.2 | 0.47 ± 0.3 | 0.30 ± 0.2 | 0.42 ± 0.3 |

| Sim-Sac on Picture (red) | 44 ± 12 | 65 ± 14 | 0.70 ± 0.2 | 0.57 ± 0.3 | 0.37 ± 0.2 | 0.55 ± 0.3 |

Values are means ± SD. All amplitudes, including those of the late response phase, are expressed relative to the Flash-on-Gray peak amplitude. Values in first 4 rows were obtained from our entire sample of 74 recording sites. Values in last row come from a subset of that sample, with 42 recording sites. RF, receptive field.

As shown in Fig. 4C (thick traces) and Table 1, response latencies to a stimulus flashed on a homogeneous gray (black trace) or a complex background (blue) are similar and significantly shorter than latencies in saccade conditions (magenta, green) [2-way ANOVA, P < 0.00005; P(flash vs. saccade) < 0.00005]. Saccades not only delay the beginning of the response to an object but also reduce the speed of the response [rise time depends on the condition: 2-way ANOVA, P = 0.002; P(background) = 0.01]. Overall, the response is most delayed and sluggish after a saccade on a complex background (green trace in Fig. 4C), and this translates into a response peak that is delayed relative to all the other conditions. It is important to note that the delay in the saccade condition responses is not simply the time it takes the bar stimulus to sweep across the RF; from the time the bar first enters the RF to the time the eyes reach the final fixation point there are only a few milliseconds, whereas the response latency and peak are delayed 7–14 ms. Even more interesting, the response is much more delayed when the background is complex rather than homogeneous, even though the eye dynamics are comparable.

The peak response amplitude is affected by both saccades [P(Flash vs. Saccade) = 0.001] and background type [P(Gray vs. Picture) < 0.00005]. As summarized in Table 1, compared with the Flash-on-Gray condition, the peak response is 92% in the Flash-on-Pic condition, 85% in the Sac-on-Gray condition, and 59% in the Sac-on-Pic condition. A reduced response with a complex background compared with a uniform background is expected from known modulatory effects of the extraclassical RF (Albright and Stoner 2002; Allman et al. 1985). More surprising is the reduced response that results when a saccade brings the stimulus into the RF with either type of background. Overall, the most natural condition, Sac-on-Pic (green), produced the smallest response (59% of the Flash-on-Gray condition). The reduced response in the most natural condition is significantly smaller than a simple combination of the reductions produced independently by the background and saccade factors (0.92 × 0.85 = 0.78 > 0.59). Evidently there is a nonlinear response depression from the combined factors of presentation and background types in the Sac-on-Pic condition. Consistent with the free viewing study by Gallant et al. (1998), surround suppression is not sufficient to explain the reduced response we observed with saccades on natural images.

Comparing the flash conditions with the saccade conditions makes an important point about the effectiveness of surround modulation in the two situations. In Fig. 4 the traces for the two flash conditions (black and blue) are much more similar than the traces for the two saccade conditions (magenta and green). When the stimulus is flashed in the RF, the peak response with a complex picture background (blue) is 8% less than with a gray background (black). On the other hand, when the stimulus comes into the RF with a saccade, the picture background response (green) is 26% lower than on a gray background (magenta). Thus, in the more natural conditions with saccades, the influence of visual context is much greater than in the flash conditions commonly used in experiments. The implication is that the many studies conducted with fixation paradigms may significantly underestimate the influence of visual context in natural vision.

Early activity in saccade-on-picture condition.

We found that a few cells in our sample (7 cells = 10% of the recorded units) showed an increase of activity in the Sac-on-Pic condition that preceded the responses to the other conditions (example in Fig. 5A; 7-cell average in Fig. 5B). This early activity is manifested as a small bump, around t = 27 ms, in the average Sac-on-Pic response (Fig. 4C, green trace) that disappears from the average if the 7 early-response units are removed (not shown). The origin of the Sac-on-Pic early response component could be 1) an internal, nonvisual, signal present in V1 during a saccade (i.e., corollary discharge), 2) an anticipatory response to the stimulus that would enter the RF at the end of the saccade (i.e., RF remapping), or 3) a response of the neuron to the background image sweeping across the RF during the saccade. To discriminate between these alternatives, we used Sac-on-Gray-NoBar and Sac-on-Pic-NoBar control conditions in some experiments (Fig. 1). Responses in the Sac-on-Gray-NoBar condition (gray trace in Fig. 5B) did not show any early activity, suggesting that the early response is not simply a manifestation of a corollary discharge. The green bold and thin traces in Fig. 5B show responses in the Sac-on-Pic condition to the optimal and 60° counterclockwise bars in the RF, respectively. These two responses peak at 27 ms and appear identical until ∼40 ms, where they diverge. This indicates that the early response is insensitive to the orientation of the bar that will enter the RF at the end of the saccade. This observation does not favor the hypothesis of an anticipatory response (remapping); neither does the fact that we never saw an early peak during saccades on the gray background (magenta).

Fig. 5.

A subpopulation of neurons had an unusual early response in the Sac-on-Pic condition (green). A: single cell example showing an early response in the Sac-on-Pic condition. B: average response of 7 cells that showed an early component in the Sac-on Pic condition. Color code as in Figs. 1 and 4; thick lines show optimal-orientation responses, thin lines show responses to bars tilted 60° counterclockwise from optimal. The thin gray trace is the response in the Sac-on-Gray-NoBar condition, and the thin cyan trace is the response in the Sac-on-Pic-NoBar condition. The Sac-on-Pic responses (green, thick and thin traces) show an early increase of activity between 10 and 30 ms. The early response in the Sac-on-Pic-NoBar condition (cyan) is nearly identical in that period, suggesting that the early activity is due to visual stimulation during the saccade rather than afterward.

The Sac-on-Pic-NoBar condition (cyan trace) produced little response at times when the presence of the bar at the end of a saccade would make the cells respond (t > 40 ms). However, the early component (t ≈ 27 ms) was indistinguishable from the Sac-on-Pic condition (green). This suggests that the early component is a response to the relative movement of the background scene during saccades.

Effects of visual context and saccades on orientation selectivity.

In addition to the effects on response amplitude and timing, saccades and background type also influence the latency, time course, and magnitude of orientation selectivity (Fig. 4D). As expected from the delayed response, orientation selectivity is slowest to develop in the Sac-on-Pic condition (green). More surprising is the greater peak selectivity in the most natural condition (0.47 compared with 0.35 in the Flash-on-Gray condition, at t ≈ 65 ms). Closer inspection of Fig. 4C (thick green line for optimally oriented stimulus, thin line for stimulus 60° from optimal) shows that the responses to the preferred and nonpreferred orientation stimuli are not simply scaled versions of each other. Rather, the response to the nonpreferred stimulus (thin green line) rises more slowly and peaks later than the preferred-orientation response (thick green line). By comparison, in the other three conditions the preferred and nonpreferred responses are more similar with a change in overall gain (thick and thin black, blue and magenta). At this point we do not know why the time course of the Sac-on-Pic response changes so much with orientation. Perhaps the combined effects of saccades and background push the response below a linear operating region in the already weaker Sac-on-Pic response. For unknown reasons, of the four conditions tested the Flash-on-Pic response showed the largest steady-state selectivity (Fig. 4D, blue trace, t > 100 ms; 2-way ANOVA, P = 0.004).

Factors responsible for the unique response in the most natural condition.

We considered three factors that might be involved in the altered responses in the most natural condition. One factor that we have largely ruled out is adaptation. In the Sac-on-Pic condition, the RF is stimulated on the penultimate fixation, something that does not occur in the flash conditions. If adaptation during one fixation reduces the response on the next, we would expect to see a negative correlation between activity on a fixation and activity on the previous fixation. However, instead of a negative correlation, we found a small positive correlation between the response on each fixation and the response on the previous fixation (R2 < 0.11, P = 0.004). Furthermore, no correlation was found between the fixation response and activity just prior to the response (possibly resulting from visual stimulation during saccades). Therefore adaptation across saccades does not appear to be a major factor.

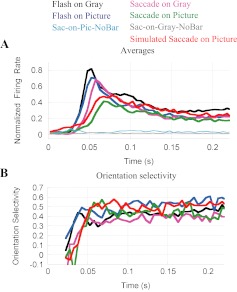

The neural signals responsible for reduced responses in more natural conditions might come from visual stimulation of the entire visual field during saccades or from a corollary discharge associated with the eye movement. We found that both of these factors are important. To test the role played by global image motion during the saccade, we added simulated saccade controls in which natural images were moved across the retina by computer animation with the dynamics of actual saccades (condition described in Fig. 1F, results in Fig. 6). The Sim-Sac responses (red lines in Fig. 6A) were, on average, similar to the Sac-on-Pic response (green lines). In both cases the responses are slower and their peak amplitude lower than the other three conditions.

Fig. 6.

Responses in simulated saccade conditions are similar to responses with real saccades. A: average response of 42 cells to an optimally oriented bar of light in the 4 principal conditions (color code as in Figs. 1 and 4). The response in the simulated-saccade condition (red trace) is largely similar to the response with a real saccade on a complex scene (green). However, with real saccades the response amplitude is lower. B: orientation selectivity in the Simulated-Saccade condition (red) follows a pattern similar to the Sac-on-Picture condition (green).

The movement of the background image during a saccade accounts for much, but not all, of the effects observed with saccades on a complex background. The response latency in simulated saccades falls short of the actual-saccade response (P = 0.0001, paired t-test) and is similar to the Sac-on-Gray condition (magenta; see Table 1). In the Sim-Sac condition (red) the response is ∼60% of the Flash-on-Gray (black) response, but actual saccades reduce this amplitude a further 10% (Table 1). The early response (which we attributed to visual input during a saccade) is also present in the simulated saccade activity (t ≈ 20 ms and on), but this early activity is smaller in the actual-saccade condition (P < 0.00005, Wilcoxon paired test). Orientation selectivity develops in similar ways in actual and simulated saccades (Fig. 6B, green and red traces, respectively) and attains similar values (peak: P = 0.99, late phase: P = 0.06; Wilcoxon paired tests).

The suppression of early activity observed in the real-saccade condition is consistent with the idea of a corollary discharge gating of input information to or in V1 during a saccade. However, unexpectedly, our data suggest that this corollary discharge, or some other signal related to actual saccades, may extend beyond the time window of the saccadic visual input into the response itself, reducing the response.

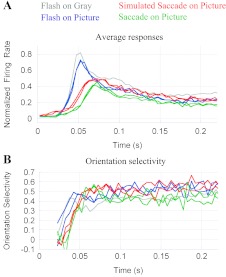

“Naturalness” is not critical for the effects of a complex background.

The discussion to this point has addressed the importance of saccadic eye movements and complex stimulus surrounds in natural visual responses. Not clear from these findings is whether the effects of the complex backgrounds were a consequence of them being natural images or instead simply images with complex arrangements of light and contours. To investigate this point we compared responses based on natural image surrounds with responses involving unnatural scenes synthesized with the Portilla and Simoncelli texture algorithm (see materials and methods). Figure 7A shows responses in the Flash-on-Pic (blue), Sac-on-Pic (green), and Sim-Sac (red) conditions. There are two traces of each color that represent the responses when the background was either the natural scene (shown in Fig. 2A) or an unnatural version of that scene (Fig. 2D). For each condition, the responses superpose so well that it is difficult to see any difference. The orientation selectivity traces are noisier (Fig. 7B), but responses in each condition are similar regardless of the particular scene shown in the background. Similar results were observed when responses with three different natural scene backgrounds were compared (results not shown). Therefore, neither the “naturalness” of the scene nor its particular elements are critical for the contextual effects seen in V1 responses as long as the statistics of the scene remain globally similar.

Fig. 7.

Effects of background scene “naturalness.” A: average responses in the Flash-on-Gray (gray), Flash-on-Pic (blue), Sac-on-Pic (green), and Simulated-Saccade conditions (red). Traces of the same color show responses in the same condition with natural and “unnatural” background images. Multiple unnatural images, such as those in Fig. 2, gave responses indistinguishable from responses to the natural images they were derived from. B: orientation selectivity of the cells shown in A. No systematic changes were observed as a function of the “naturalness” of the background scene.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here show that in more natural situations V1 responses are different from responses in more reduced paradigms in the following ways: lower amplitude, longer latency, slower time course, delayed orientation selectivity, and higher peak orientation selectivity. In a previous study (MacEvoy et al. 2008), we examined the first of these properties (amplitude); more on that below. The aspects of natural vision that we have studied are the complexity of the background beyond the RF (complex picture vs. uniform gray) and saccades that bring stimuli into RFs rather than flashing the stimuli to a fixating animal. The results suggest that the many studies using flashed stimuli in reduced contexts overestimate the speed and especially the amplitude of V1 responses when extrapolating their measurements to natural vision. Response speed and amplitude are important because, in natural conditions, the typical duration of fixations in humans is short [300 ms (Otero-Millan et al. 2008)] and because the processing time of the primate visual system is very fast, on the order of 100 ms or less (Crouzet et al. 2010; Fabre-Thorpe et al. 1998; Keysers et al. 2001; Stanford et al. 2010; Thorpe et al. 1996). This means that the actual spikes taken into account to perform a computation are few, plausibly coming from the initial response in each fixation, and that they must be processed in a brief time window. This makes relevant the delay, response reduction, and early orientation selectivity differences found in the present study. Whether or not they are advantageous, natural-vision response delays may represent the additional processing necessary to cope with the enormous demands of analyzing images in nonconstrained natural settings.

Although there are previous studies that explored the effects of saccades or background type, most of the results presented here are novel. We confirmed the well-established point that stimulus contrast outside the RF suppresses the response to an RF stimulus (Albright and Stoner 2002; Allman et al. 1985). More unexpected, however, is the large response reduction that results from a saccade, even when the stimulus within and outside the RF is the same as in a fixation/flash condition. This result is particularly surprising because several well-conducted studies reported that V1 responses were unaffected by eye movements (Gawne and Martin 2002; Wurtz 1969). Experimental details probably account for the differences found in our study. For example, Wurtz (1969) recorded V1 responses when stimuli moved rapidly across RFs because of either image motion or a saccade. Thus the results apply to V1 responses to visual input during saccades rather than during fixations, as in our study. Moreover, the Wurtz experiments were conducted with a blank background most similar to our Flash-on-Gray and Sac-on-Gray conditions; they did not include a Sac-on-Pic condition, the most natural condition in our study, and the one that produced the most unique visual responses. Gawne and Martin (2002) reported that most neurons gave similar responses to checkered patterns in flash and saccade conditions, but a minority showed amplitude or latency differences in their responses. Again, the background used in the study by Gawne and Martin was always gray; in this situation we find the saccade effects are smaller than with a complex background. Overall our findings are not at odds with previous studies that used saccades to bring stimuli into RFs; rather, they extend the studies to the more natural situation in which saccades are made across complex backgrounds.

In addition to saccades, the other aspect of natural vision we have examined is the “naturalness” of visual context—controlled bar stimuli were presented on photographs of outdoor scenes. Natural scenes have unique statistical properties, and there is evidence that cortical processing may be adapted to them (Olshausen and Field 1996). Kayser et al. (2003) found that natural image responses in cat area 17 are qualitatively different than responses to gratings and to a number of other less natural stimuli. David et al. (2004) found that, in general, V1 responses are better predicted by responses to natural images than to more reduced stimuli. A critical distinction between our work and these earlier contributions is that we considered natural images only as background stimuli, not as the stimulus driving the RF. In our case, we wanted to ensure that across conditions the RF was stimulated in as identical a manner as possible. Thus it was impractical to have the complex features of natural images entering the RFs. We find that responses to bar stimuli in the RF are strongly modulated by the surround but that modulation by natural image backgrounds is indistinguishable from modulation by similar unnatural image backgrounds (i.e., unnatural images synthesized with the Portilla and Simoncelli texture algorithm). In our hands, background stimulus complexity mattered, but naturalness did not.

The effects of saccades and background type on the amplitude of V1 responses were studied previously by MacEvoy et al. (2008). In that study we found that V1 responses were much less different and that responses in natural conditions were slightly larger than in reduced conditions. We attribute the differences between that study and the present one to the more refined experimental and analysis techniques used in the present work. In the MacEvoy et al. study, there was uncertainty in the start times of saccades because a 60-Hz eye tracker was used compared with the 1-kHz tracker used in the present study. Also, firing rates were analyzed in long epochs (500 ms). The present experiments used faster eye tracking (and consequent better estimates of saccade and fixation onsets) and shorter analysis windows, and they provide a more accurate measure of V1 responses just after the start of new fixations.

The fact that one of our stimulus conditions included both saccades and complex-image backgrounds appears to be very important. There have been numerous studies of saccades and natural images separately, but few combined these two factors. Our results suggest that natural vision responses are unique because saccade and background factors occur in combination and interact nonlinearly. This effect was most clear in the response amplitude. A complex background gives a lower response than a gray background, and a saccade gives a lower response than flashing a stimulus. However, the combined effect of a stimulus introduced by a saccade on a complex background is much greater (much more reduced response amplitude) than would be predicted from the separate effects. This point is probably related to the report by Gallant et al. (1998) that surround suppression is stronger in free viewing. Our stimulus paradigms were not as natural as free viewing, but they did allow a level of control making it possible to directly compare flash and saccade conditions.

As to the source of the response changes we see in the more natural conditions, we can only speculate. The reduced response after a saccade on a complex background could be a result of adaptation. It has been reported that, after exposure to natural images, the human contrast sensitivity function shows a selective loss in low spatial frequencies (Bex et al. 2009; Webster and Miyahara 1997). Further experiments will be required to assess the role, in our results, of adaptation to natural or natural-like complex images. In any case, note that the normal-day environment of a sighted primate is visually complex. Our results, together with those by Bex et al. and Webster and Miyahara, suggest that in visual experiments gray backgrounds between trials and isolated stimuli are actually elevating visual sensitivity at low spatial frequencies. This calls into question the generality of the standard contrast sensitivity function determined in most experiments.

Another contribution to the response changes we see in the more natural conditions might come from the inhibitory circuitry of the LGN and V1. It has been shown in cats that electric stimulation of the optic tract produces fast and transient excitatory synaptic potentials in pyramidal neurons, quickly followed by a strong and long GABA-mediated hyperpolarization (Douglas and Martin 1991). Also in the cat, similar excitation/inhibition patterns can be produced by electrical stimulation of neighboring regions of V1 (Chung and Ferster 1998; Hirsch and Gilbert 1991). The response reduction, and the striking resemblance between our responses in real and simulated saccades on complex backgrounds, suggest that feed-forward and lateral inhibition may be involved in the suppression of the response. When a saccade on a complex background occurs, the visual image redistributes abruptly on the retina. This would translate into a massive change in neural activity in the optic nerve, LGN, and V1. We hypothesize that the firing of many newly activated axons will activate feed-forward inhibitory interneurons in the LGN and V1, and that this transient of inhibition might account for much of the suppression that we observed after saccades on complex scenes.

Many of the other properties we studied, such as the timing of V1 responses and feature selectivity, have not been previously examined in more natural paradigms, although there are studies (e.g., Guo et al. 2007) showing that responses to bar stimuli are influenced by previous stimuli appearing beyond the RF. Combined with the decreased response amplitude noted already, our results show that V1 responses in more natural situations exhibit a spectrum of differences from responses in more reduced paradigms. Our working hypothesis is that the response differences in natural situations result from altered activation of the cortical network. By using simulated saccades we found that motion of the scene during saccades was responsible for much of the response difference in flash and saccade conditions. The effect of simulated saccades also distinguishes the response reduction we observed from saccadic suppression mediated solely by corollary discharge. Corollary discharge signals seem to play a role, nevertheless, as real saccades decrease response amplitude somewhat more than simulated saccades.

Our results make predictions about how visual perception in more natural paradigms should differ from perception in simplified situations. For example, when saccades are made across complex backgrounds response amplitude is significantly lower than with flashed stimuli presented during fixation. In an experiment such as contrast detection, it may take more contrast to reach perceptual threshold with a saccade across a picture than with a flashed stimulus presented in isolation. Our findings also make predictions about the effects on perception of visual context. Context is hugely important in virtually every aspect of visual perception; there are strong interactions between the lightness, color, orientation, and motion at different locations in the visual field. For this reason it seems highly significant that we found that surround interactions are much stronger in natural visual paradigms than in reduced situations. Virtually everything that is known about visual context and the influence of surround stimuli is based on fixation experiments with flashed stimuli. Our results suggest that surround interactions would be significantly stronger, and more characteristic of natural vision, if experiments were conducted with stimulus presentation via saccades. Finally, the data presented here suggest that a careful perceptual study would reveal that the sensitivity to stimulus orientation, and perhaps other attributes, is highest when new stimuli are viewed at the end of saccades. Moreover, perceptual sensitivity should follow a time course that is unique to more natural vision.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Eye Institute Grant EY-09050.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: O.R. and M.A.P. conception and design of research; O.R. performed experiments; O.R. analyzed data; O.R. and M.A.P. interpreted results of experiments; O.R. prepared figures; O.R. and M.A.P. drafted manuscript; O.R. and M.A.P. edited and revised manuscript; O.R. and M.A.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Aaron Gregoire for his skilled assistance with animal training and care, Dr. Moses Goddard for advice in surgical procedures, and Drs. Stuart Geman and Hernando Ombao for advice with statistical analyses.

REFERENCES

- Albright TD, Stoner GR. Contextual influences on visual processing. Annu Rev Neurosci 25: 339–379, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman J, Miezin F, McGuinness E. Stimulus specific responses from beyond the classical receptive field: neurophysiological mechanisms for local-global comparisons in visual neurons. Annu Rev Neurosci 8: 407–430, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bex PJ, Solomon SG, Dakin SC. Contrast sensitivity in natural scenes depends on edge as well as spatial frequency structure. J Vis 9: 1.1–1.19, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spat Vis 10: 433–436, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Ferster D. Strength and orientation tuning of the thalamic input to simple cells revealed by electrically evoked cortical suppression. Neuron 20: 1177–1189, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouzet SM, Kirchner H, Thorpe SJ. Fast saccades toward faces: face detection in just 100 ms. J Vis 10: 1–17, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David SV, Vinje WE, Gallant JL. Natural stimulus statistics alter the receptive field structure of v1 neurons. J Neurosci 24: 6991–7006, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deubel H, Bridgeman B. Fourth Purkinje image signals reveal eye-lens deviations and retinal image distortions during saccades. Vision Res 35: 529–538, 1995a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deubel H, Bridgeman B. Perceptual consequences of ocular lens overshoot during saccadic eye movements. Vision Res 35: 2897–2902, 1995b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas RJ, Martin KA. A functional microcircuit for cat visual cortex. J Physiol 440: 735–769, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhamel JR, Colby CL, Goldberg ME. The updating of the representation of visual space in parietal cortex by intended eye movements. Science 255: 90–92, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason SR. Maximum Likelihood Estimation: Logic and Practice. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1993, p. 87 [Google Scholar]

- Fabre-Thorpe M, Richard G, Thorpe SJ. Rapid categorization of natural images by rhesus monkeys. Neuroreport 9: 303–308, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS, Priebe CE. Estimating stimulus response latency. J Neurosci Methods 83: 185–194, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant JL, Connor CE, Van Essen DC. Neural activity in areas V1, V2 and V4 during free viewing of natural scenes compared to controlled viewing [corrected and republished article originally printed in Neuroreport 9: 85–90, 1998]. Neuroreport 9: 2153–2158, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawne TJ, Martin JM. Responses of primate visual cortical neurons to stimuli presented by flash, saccade, blink, and external darkening. J Neurophysiol 88: 2178–2186, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K, Robertson RG, Pulgarin M, Nevado A, Panzeri S, Thiele A, Young MP. Spatio-temporal prediction and inference by V1 neurons. Eur J Neurosci 26: 1045–1054, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JA, Gilbert CD. Synaptic physiology of horizontal connections in the cat's visual cortex. J Neurosci 11: 1800–1809, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Blau S, Paradiso MA. Background changes delay the perceptual availability of form information. J Neurophysiol 94: 4331–4343, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Paradiso MA. Background changes delay information represented in macaque V1 neurons. J Neurophysiol 94: 4314–4330, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser C, Kording KP, Konig P. Processing of complex stimuli and natural scenes in the visual cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol 14: 468–473, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser C, Salazar RF, Konig P. Responses to natural scenes in cat V1. J Neurophysiol 90: 1910–1920, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keysers C, Xiao DK, Foldiak P, Perrett DI. The speed of sight. J Cogn Neurosci 13: 90–101, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusunoki M, Gottlieb J, Goldberg ME. The lateral intraparietal area as a salience map: the representation of abrupt onset, stimulus motion, and task relevance. Vision Res 40: 1459–1468, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone MS, Freeman DC, Hubel DH. Visual responses in V1 of freely viewing monkeys. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 61: 27–37, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacEvoy SP, Hanks TD, Paradiso MA. Macaque V1 activity during natural vision: effects of natural scenes and saccades. J Neurophysiol 99: 460–472, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Colby CL. Updating of the visual representation in monkey striate and extrastriate cortex during saccades. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 4026–4031, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshausen BA, Field DJ. Natural image statistics and efficient coding. Network 7: 333–339, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otero-Millan J, Troncoso XG, Macknik SL, Serrano-Pedraza I, Martinez-Conde S. Saccades and microsaccades during visual fixation, exploration, and search: foundations for a common saccadic generator. J Vis 8: 21.1–21.18, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papoulis A, Pillai SU. Probability, Random Variables, and Stochastic Processes. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: transforming numbers into movies. Spat Vis 10: 437–442, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portilla J, Simoncelli EP. A parametric texture model based on joint statistics of complex wavelet coefficients. Int J Comput Vis 40: 49–71, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Reppas JB, Usrey WM, Reid RC. Saccadic eye movements modulate visual responses in the lateral geniculate nucleus. Neuron 35: 961–974, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford TR, Shankar S, Massoglia DP, Costello MG, Salinas E. Perceptual decision making in less than 30 milliseconds. Nat Neurosci 13: 379–385, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe S, Fize D, Marlot C. Speed of processing in the human visual system. Nature 381: 520–522, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolias AS, Moore T, Smirnakis SM, Tehovnik EJ, Siapas AG, Schiller PH. Eye movements modulate visual receptive fields of V4 neurons. Neuron 29: 757–767, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hateren JH, van der Schaaf A. Independent component filters of natural images compared with simple cells in primary visual cortex. Proc Biol Sci 265: 359–366, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinje WE, Gallant JL. Sparse coding and decorrelation in primary visual cortex during natural vision. Science 287: 1273–1276, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MA, Miyahara E. Contrast adaptation and the spatial structure of natural images. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis 14: 2355–2366, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtz RH. Comparison of effects of eye movements and stimulus movements on striate cortex neurones of the monkey. J Neurophysiol 32: 987–994, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]