Abstract

What are pregnant couples' concerns regarding their sexual relationship after their baby's arrival? A study in regard to this question was conducted with five prenatal groups (n = 82). Its results are presented in this article. The sexual concerns are categorized as being about physical matters, psychological issues, adaptation issues, and anticipatory planning. A review of the literature then develops the theoretical interpretation of each of the sexual concerns and offers suggestions for childbirth educators to address some of these issues.

Keywords: pregnancy, postpartum, sexuality, sex education

Pregnant couples participating in the author's perinatal education classes have mentioned many concerns regarding their sexual relationship once their baby is born. Their concerns are mainly based on information from couples within their social networks who have become parents. Couples have expressed major fears stemming from permanent changes within this aspect of their relationship. Their fears have also been fueled by the fact that some couples do not appear to weather the storm often associated with the baby's arrival, leading potentially to separation and divorce. The pregnant couples have asked how to keep the love and passion alive after their baby's arrival, how to adjust their lovemaking, and how to find the time and energy to pursue their sexual activities.

To learn more about these postnatal sexual concerns and to be able to address them, the author of this article conducted a qualitative study with five prenatal groups. In this article, the results of the study are presented and each sexual concern is explained from the expectant parents' viewpoint. A theoretical interpretation from the literature is provided to discuss the expectant parents' viewpoint. Also, an adjustment of the sexual repertoire is offered in relation to the sexual concern. Finally, recommendations are proposed for the handling and integration of these sexual concerns within traditional perinatal education classes.

Method and Sample

A qualitative study with five prenatal groups was conducted from January to December 1998. Eighty-two expectant parents (41 couples) were asked their concerns regarding their sexual relationship in the postpartum period. Data were gathered from the five workshops in which men and women were subdivided into two groups. The content of the workshops was advertised as either intimacy and pregnancy or intimacy and the postpartum. Each subgroup listed their concerns on large sheets of paper that were later taped to the walls of the room. These sheets of paper were retained for data analysis. A small questionnaire gathering basic sociodemographic and pregnancy data was also distributed to each couple. Permission to participate in the study was obtained by the couple's willingness to answer the questionnaire. All expectant parents consented to participate in the study.

The sociodemographic and pregnancy data for the five prenatal groups (n = 82) are presented in Table 1. The average age for the men was 29.18 years; for the women, 27.49 years. Most of the couples were married and employed, and most were born in the province of Québec. All of the couples were expecting their first child. However, for three women, this was not their first pregnancy: two of them had each experienced one previous miscarriage, while another woman had had two previous miscarriages. The average gestational age was 25.16 weeks with a range from 16 to 32 weeks.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Pregnancy Data for the Five Prenatal Groups

| A. Sociodemographic Data |

| 1. Prenatal Groups |

| Group 1 – 22 participants (11 couples) |

| Group 2 – 8 participants (4 couples) |

| Group 3 – 14 participants (7 couples) |

| Group 4 – 24 participants (12 couples) |

| Group 5 – 14 participants (7 couples) |

| Total – 82 participants (41 couples) |

| 2. Age |

| Men – Range from 21 to 37 years |

| Mean – 29.18 years |

| Women – Range from 19 to 43 years |

| Mean – 27.49 years |

| 3. Marital Status |

| Married – 31 couples (75.6%) |

| Cohabitating – 10 couples (24.4%) |

| 4. Employment Situation |

| Men Working – 40 (97.6%) |

| Men Unemployed – 1 (2.4%) |

| Women Working – 34 (82.9%) |

| Women Unemployed – 2 (4.9%) |

| On Health Leave – 5 (12.2%) |

| 5. Born in Québec |

| Men Yes – 40 (97.6%) |

| Men No – 1 (2.4%) |

| Women Yes – 41 (100%) |

| Women No – 0 (0%) |

| B. Pregnancy Data |

| 6. First Baby |

| Men Yes – 41 (100%) |

| Women Yes – 41 (100%) |

| 7. Miscarriages |

| One Previous Miscarriage – 2 |

| Two Previous Miscarriages – 1 |

| 8. Gestation Period |

| Range – from 16 to 32 weeks |

| Mean – 25.16 weeks |

Study Results

The postnatal sexual concerns of each workshop subgroup are presented in Table 2. Using qualitative methods, the sexual concerns were then grouped into four major themes: (a) physical matters, (b) psychological concerns, (c) adaptation, and (d) anticipatory planning.

Table 2.

Study Results: Pregnant Couples' Postnatal Sexual Concerns

| Group 1 | |

| Men | |

| • having time for each partner and the couple | |

| • communication | |

| • making love is easier after 2 months | |

| • each couple is different | |

| • difficult birth will influence the situation | |

| • changes that will occur once baby is there | |

| Women | |

| • fear of pain in the vagina | |

| • to be touched with tenderness | |

| • the male partner who does not want to make love, who could be traumatized from the birth, his fear of hurting the woman | |

| • adaptation: to have time, to give oneself time, to let go, to be able to separate oneself from the baby | |

| • contraception | |

| • reactivating the passion, fun and games, sex, love, how to do these things, romance | |

| • communication | |

| Group 2 | |

| Men | |

| • sexual desire and the woman's libido | |

| • avoiding another pregnancy (contraception) | |

| • sexual intercourse the first time | |

| • distance in the couple after the baby's arrival | |

| Women | |

| • to be desired | |

| • vaginal pain during sexual intercourse | |

| • fatigue and its impact on sexual desire | |

| • greatest worry: that all of her attention is focused on the baby, thus potentially excluding the male partner | |

| • his perception of her and her body after the birth | |

| Group 3 | |

| Men | |

| • the timing: when to resume sexual intercourse | |

| • postpartum depression | |

| • too much attention on the baby and none for him | |

| • will the woman feel beautiful and desirable? | |

| • intimacy and baby: balancing these two aspects | |

| • lovemaking: that it becomes too planned and not spontaneous enough | |

| Women | |

| • time to adapt to everything: having time for baby, one's body to recover from the birth, time for mothering, not to feel rushed to have sex | |

| • communication | |

| • fear of forgetting oneself | |

| • fear of pain during sexual intercourse | |

| Group 4 | |

| Men | |

| • pain | |

| • loss of sensation | |

| • how to please partner | |

| • her libido | |

| • fatigue | |

| • finding time to make love | |

| • depression | |

| • breastfeeding | |

| • the child's presence/handicapped child | |

| • birth complications | |

| Women | |

| • fear of pain | |

| • change in partner's perception regarding her body | |

| • lowered sexual desire | |

| • contraception | |

| Group 5 | |

| Men | |

| • timing | |

| • pain upon intercourse | |

| • reluctance/hesitation | |

| • libido (man and woman) | |

| • different? sensual? same? | |

| Women | |

| • time required for healing | |

| • does the male partner see her as the mother of his child or as his woman? | |

| • to find the time to make love | |

| • the women do not want the men to change their behavior as lovers | |

| • life will change, but not too much |

Physical Matters.

Both the men and the women posed questions regarding the following topics: resumption of sexual intercourse, potential vaginal pain that could be encountered during first-time sexual intercourse, the impact of a difficult birth on sexual intercourse, the influence of fatigue on the return of the sexual relationship, and the use of contraception to prevent another pregnancy. This last aspect was more important for those couples who had experienced an unplanned pregnancy.

Psychological Issues.

The men were concerned about postpartum depression, lovemaking becoming too organized, how to avoid distance in the relationship, and the woman's sexual libido after the birth of the baby. Some men wondered if their female partner would still feel beautiful and desirable. The women expressed similar concerns: Would their male partner still desire them? How would their male partner perceive their bodies after the baby's birth? What if their malepartner would no longer want to make love because he was traumatized by the birth experience and perhaps was afraid of hurting his partner?

Adaptation Issues.

These concerns included creating time for recovery from the birth and striking a balance among individual, couple, family, and work needs. The women expressed worries such as learning to separate themselves from the baby, finding time for themselves, and giving so much attention to the baby that the father might feel excluded. The men who feared that the new mother would not have time for them also shared the last concern. Some women stated this worry in another way: Would their male partner primarily perceive them as the mother of his child or as his woman?

Anticipatory Planning.

Some pregnant couples had already started to foresee the issues and propose particular solutions. These men and women mentioned the value of communication, the uniqueness of each couple, and the importance of not feeling rushed to reinitiate sex. Some couples also were planning to reignite the passion through specific fun and games and had discussed the place of romance in the reactivation process.

Review of Literature

In general, the literature not only supports the universality of these couples' concerns but also contains specific techniques for addressing their problems.

Background Support—Paradigm of Love.

Luscher (1996) defines true love as “a garden where feelings of understanding, unity, attention, helpfulness, respect, and responsibility must be sown before they are reaped” (p. 86). He goes on to say that love transforms itself when a couple experiences a major life event such as the arrival of a new family member. New parents must become aware of the change in their love. This can be achieved only through dialogue. The romantic encounter permits the creation of an ambiance that favors the development of close feelings, the sharing of intimate thoughts, and the enhancement of the couple's bond.

…love transforms itself when a couple experiences a major life event such as the arrival of a new family member. New parents must become aware of the change in their love.

Luscher (1996) states that complete love is the basis for a life filled with happiness. He posits that there are two parts to true and complete love. The first part involves erotic unity or physical, emotional, and spiritual unity. Through sexual union, the partners experience a readiness to understand and connect with each other on an emotional and spiritual level. The second part focuses on respect for the partner by honoring both the individuality and independence of the other. “When you truly love your partner's individuality, then you can also respect the fact that your partner will change” (Luscher, 1996, p. 88).

Physical Concerns.

The resumption of sexual intercourse depends on the absence of lochia, which usually occurs for 2 to 4 weeks after vaginal and cesarean births (Polomeno, 1995). Some vaginal spotting may take place during breastfeeding and persist until 6 weeks postpartum (Polomeno, 1999b). Many women and men fear the resumption of sexual intercourse due to the pain associated with entry of the penis into the vagina. This fear may be alleviated by using perineal massage both to test the area and to soften the tissue that may have been cut and/or torn (Polomeno, 1995). Once the area is ready, sexual intercourse may be resumed with less pain and fear.

Other factors such as a difficult birth, fatigue, and a demanding baby have the potential to delay the resumption of sexual intercourse. However, some couples have a great urge and need to resume lovemaking as soon as possible. Some make love upon returning home from the hospital, which involves the approach of “sex without intercourse” (Bing & Colman, 1977; Hooper, 1992; Kitzinger, 1981). Such couples have explained they needed to reconnect sexually after experiencing the joy of the birth of their child.

For those couples who had experienced an unplanned pregnancy, contraception becomes an important subject (Polomeno, 1995). The choice of a contraceptive method will depend on the couple's values and beliefs, especially cultural and religious, and the man's involvement in the decision-making process. For the breastfeeding women, contraception is also a major issue (Polomeno, 1999b).

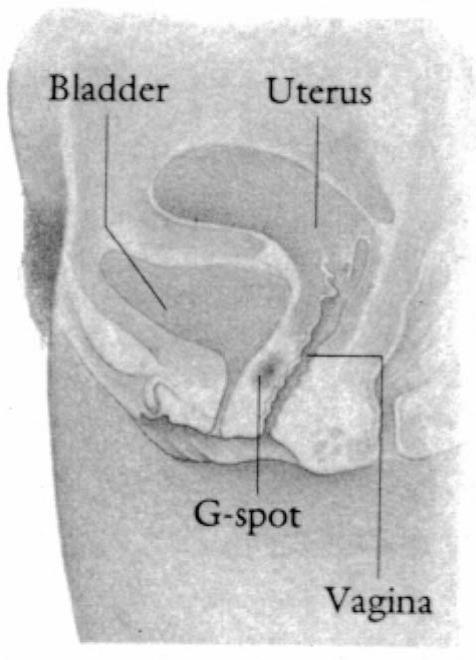

For some women, birthing appears to deviate and/or modify the source of orgasmic pleasure. Bing and Colman (1977) and Kitzinger (1981) mention that a new mother is able to experience orgasm; however, achieving orgasm may require more time, and the sensation may be less intense and of shorter duration in the initial phase of postnatal sexual resumption. Polomeno (1995, 1999b) proposes a 4-step process in the reawakening of a woman's libido after the birth of her baby. (A summary of this process is featured on page 36 in the Volume 8, Number 1 issue of The Journal of Perinatal Education.) Ganem (1992) stipulates that a woman's orgasm is present; however, it is in transition just as the couple's sexual relationship is in transition in the postpartum. Certain women have discovered orgasm and even their G-spot for the first time during pregnancy and are most eager to continue after the baby's birth. According to reports from women in the author's perinatal education classes, birthing does have an impact on the G-spot; but with time and patience, stimulation and orgasm from this sensitive area does come back. See Table 3 for an explanation about the G-spot and female ejaculation.

Table 3.

The G-spot and Female Ejaculation

| The G-spot refers to an area in the pelvis described by Dr. Grafenberg in the 1940s (thus the “G” in the word G-spot is for Dr. Grafenberg). Dr. Grafenberg was a German obstetrician and gynecologist who collaborated with a prominent American obstetrician and gynecologist, Dr. Dickinson. They described a zone of erogenous sensitivity located along the suburethral surface of the anterior vaginal wall. What is remarkable about this particular area of erotic sensitivity is that women can expulse a fluid following orgasm and this has been called female ejaculation (Reeder, Martin, & Koniak-Griffin, 1997; Boston Woman's Health Book Collective, 1992). Much controversy exists over the G-spot and female ejaculation, but scientific research is emerging to confirm both aspects (Alzate & Hoch, 1986; Darling, Davidson, & Conway-Welch, 1990; Zaviacic & Whipple, 1993). |

| All women have this erogenous zone. Some women will never discover it, some are barely aware of it, and others are really G-spot women. Orgasm originating from the G-spot is different from clitorial orgasm: It is deeper and longer-lasting. Grafenberg wrote the following: “If there is an opportunity to observe the orgasm of such women, one can see that large quantities of a clear, transparent fluid are expelled not from the vulva, but out of the urethra in gushes . . . In cases observed by us, the fluid was examined and it had no urinary character . . . [S]ecretions of the intraurethral gland correlated with the erotogenic zone along the urethra in the anterior vaginal wall” (Grafenberg, 1950, p. 147). |

| How does one locate one's G-spot? |

| The G-spot is on the front wall of the vagina, halfway between the cervix and the back of the pubic bone, near the bladder. In certain women, this area is fairly large, about 1.5 cm. to 2 cm. in length. It feels like a series of ripples or muscular ridges. In the unstimulated female, the G-spot is soft, small, and the size of a bean. When it is stimulated, it can enlargen to the size of a ping pong ball. A woman can squat or lie on her back, introduce her index and middle fingers into the vagina, curve these fingers and she will feel the area. Putting pressure on this area is erotic and can lead to orgasm. The partner can continue through manual stimulation or with the penis during intercourse (Hooper, 1992). See illustration above. |

Psychological Sexual Concerns.

The psychological sexual concerns expressed by the pregnant couples centered on the following: (a) hormonal changes that could affect a new mother, such as potential baby blues/postpartum depression; (b) the mother's sexual libido; (c) the father's reaction to seeing his partner giving birth and the possibility that he might be traumatized by the experience; and (d) the consequences of this trauma, which could create distance in the couple's relationship and reduce spontaneity in postpartum lovemaking.

Sometimes, partner massage can lead to lovemaking, especially if the nature of partner massage changes and becomes erotic. Gray (1995) cites Bloomfield who says that regular sex is vital for maintaining higher estrogen levels in women, enhancing bone density and cardiovascular health, and having a feeling of joy with life. For men, regular sex increases testosterone levels, which will give them greater confidence, vitality, strength, and energy. Sex in all of its forms—including regular and erotic partner massage—is vital to a couple's relationship.

For men, regular sex increases testosterone levels, which will give them greater confidence, vitality, strength, and energy.

…regular sex is vital for maintaining higher estrogen levels in women, enhancing bone density and cardiovascular health, and having a feeling of joy with life.

Henry (1996) states that, as a form of touch, massage has been practiced for centuries to reduce stress and promote an overall sense of well-being. Henry also suggests that massage can become a loving, nurturing, and intimate act that is physically comforting and emotionally calming. “Partner massage can bring a couple closer together and alleviate some of those feelings [of anxiety and insecurity about sexual attractiveness] … [P]artner massage allows [fathers] to be involved” (p. 79). Yorke (1988) states that “ … it is now increasingly being seen as a means of communication between people who use it as a way of showing love and care, thus enriching interpersonal relationships” (p. 9).

Yorke (1988, pp. 14-15) presents the following reasons for employing sensual and erotic massage: (a) it encourages couples to create time and space in which to be alone together; (b) it costs nothing but time; (c) it is not goal centered; (d) it is a fulfilling substitute for intercourse, especially during menstruation and pregnancy and after the birth of baby; (e) it is a valuable addition to intercourse; (f) it makes sex better; (g) it is the best way to improve communication; and (h) it is pleasantly relaxing.

Adaptation Concerns.

As has been well documented in the literature, most couples will experience a period of disequilibrium, reorganization, and adjustment with the baby's arrival. Perinatal educators must sensitize couples to the transition to parenthood and all it entails, including the impact on sexual expression. This involves explaining the transition, along with its various stages, and offering ways to cope with the associated changes (Polomeno, 1999a, 1999b, 1999c). Cowan (1991) urges anticipatory guidance and learning for two reasons: (a) The fewer the new skills demanded by the transition, the fewer the obstacles in the environment, and (b) the longer one has to prepare, the easier the transition.

Perinatal educators must sensitize couples to the transition to parenthood and all it entails, including the impact on sexual expression.

Bing and Colman (1977) reveal that the period immediately following the birth is both exciting and complicated. It is a time when feelings are very intense: “ … [the couple's] relationship to each other and even to themselves will never be the same … ” (p. 133). Bing and Colman continue, “Men and women undergo profound personal, interpersonal and social changes during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Lovers must add the roles of partner and parent to the way they interact with each other … they may have to work hard to stay in touch with these changes in themselves and in their partner” (p. 159).

Hooper (1992) proposes a way to discuss any anxieties that can arise in a relationship, even those in the sexual domain. The Hooper technique of self-questioning can be shared with pregnant couples in theperinatal education setting. In this way, they are encouraged to master it in a supported psychological environment. The perinatal educator's role in relation to the Hooper technique is to help the couple extend their coping skills to deal with fears and anxieties, especially with sensitive topics involving sexual adaptation.

The partner must ask himself/herself the following questions:

Do I usually confess my anxieties to my partner? If the answer is “No,” ask yourself these next questions:

What do I fear about revealing these anxieties?

Am I anxious about worrying my partner and adding to my own burden of worry?

Do I think my partner will be critical and unsupportive?

Do I fear that my partner will see me as less of a person if I confess my weaknesses?

Do I fear that my confessions will unbalance the relationship in some way that is disastrous?

Are my fears based on the reality of my partner's likely reactions or on my own past experience in my youth?

—Hooper (1992, p. 95)

Hooper continues: “Thinking through your answers to these questions will show you what is holding you back from discussing your anxieties with your partner. The act of expressing a real fear, of hearing it accepted by your partner and finding that he or she is supportive of you, is enriching—just as releasing anxiety can be cathartic in social aspects of life … ” (p. 95).

Once the couple has shared fears and anxieties, they are encouraged to try the Map Test (Hooper, 1992), which is designed to be an enjoyable way for partners to discover and rediscover each other's bodies and their erogenous zones. The major erogenous zones of the human body are the following: (a) head, including the scalp and ears, (b) neck, (c) face, including lips, nose, and eyelids, (d) shoulders, (e) breasts and nipples, (f) arms, including inside the elbows, (g) hands, (h) fingers, (i) toes, and (j) genitals. Each area is stroked no more than 2 inches in diameter. After each stroke, the one being touched should rate the eroticism on a numerical scale from minus-3 (lack of eroticism) to plus-3 (full eroticism). Each partner retains the information on the erogenous zones that evoked the other's greatest response. Then, the couple integrates that information into their pleasuring activity during future sexual encounters with each other. According to Hooper, the Map Test should be repeated every 3 to 6 months since stimulation from the erogenous zones may change.

Anticipatory Planning.

Communication appeared to be the key element in the approach anticipated by the pregnant couples as they developed a plan to deal with their sexual concerns during the postnatal adjustment. Both the men and the women in all five prenatal groups mentioned the need for good communication.

The following techniques are described by various authors as ways to help couples increase their connectedness:

Heart Talks (Bloomfield & Vettese, 1989)—A couple can enjoy the risk of self-disclosure, discover hidden parts of themselves, and develop new emotional connections. Each partner sits in front of the other. One person starts by talking for 5 minutes without interruption. The other one listens without argument or blame and can encourage the speaker's self-disclosure by saying, “Tell me more.” Once the 5 minutes are up, the other person has a chance to talk. At the end, the couple hugs and says, “I love you!”

Scoring Points (Gray, 1998c)—Men and women differ in how they keep score regarding gifts of love, since this could be a potential area of conflict and disappointment in their relationship. For a woman, each gift of love—from taking out the garbage to planning a trip—has the same value. However, a man thinks he scores small points for small acts and big points for big gifts.

Sexual Conversation (Gray, 1995)—Couples can be encouraged to pursue dialogue on their sexual needs. They can answer the following questions: “What do you like about having sex with me?” “How did you feel when I did that?” “Would you like more sex?” “Would you like more/less time in foreplay sometimes?” “Is there something specific you would like me to do in the next month during sex?” “Is there a new way you would like me to touch you? If yes, would you show me?” “Is there anything I used to do that you would like me to do more of?”

Romance—Romance is important in keeping love, passion, and sex alive in a couple's relationship. It is a special type of intimacy that permits parents to be romantic lovers. “Intimacy is a quality that grows through a sharing of feelings; it heightens all aspects of the relationship and is the main ingredient responsible for turning sex into an ecstatic experience as opposed to a pleasurable but uninspiring one” (Hooper, 1992, p. 64). Brophy (1998) considers romance to be one of seven secrets for a lifetime of love. Romance must be continuously recreated (Gray, 1998a). Gray also writes that romance should not be taken for granted: “The real problem today in relationships is that we expect romance will happen all by itself. When romance begins to fade, we assume something is wrong. What we should be doing instead is recognizing that the requirements for romance are being overlooked” (p. 20). According to Raskin (1998), romance requires work, creativity, and planning, especially when one is a parent. Raskin indicates that keeping romance alive, as suggested by both parents and professionals, requires only one strategy: Set aside regular time with one's spouse. This involves grabbing romance whenever the parents possibly can, such as holding hands while pushing the baby's stroller. “Even mundane events like sitting down together for dinner can become an opportunity for romance” (p. 25). The rituals involved in romance tell a man that he is appreciated by his woman, and that a woman is cared for by her man (Gray, 1995). According to Gray (1995), romance is important for the following reasons: (a) it allows a woman to relax and enjoy feeling being taken care of; (b) a man's romantic behavior says repeatedly that he acknowledges his woman and, by anticipating her needs, he signals that he understands and respects her; and (c) when a woman appreciates a man's efforts and what he provides for her, a man will feel more loved and romantically inclined. Gray continues by stating that “lasting romance requires talking at the right time and in a way that doesn't offend, hurt, or sour your partner” (p. 190).“All these romantic rituals are simple but powerful. They assist us in reconnecting with those very special feelings of attraction and passion that we can only feel when we are emotionally connected” (Gray, 1995, p. 205). Romantic rituals become more important once a baby arrives since they will help the new mother to separate herself from the baby and return to her feminine side. Consequently, she will give time and attention to her mate and potentially resume her role of life partner and lover (Gray, 1998a).

Sex Without Intercourse (Bing & Colman, 1977; Hooper, 1992; Kitzinger, 1981)—The new father may experience some sexual anxiety (Kitzinger, 1981) after the baby's arrival. He may wonder if he can still sexually please his female partner. He may also worry about how he will react to her changed body, including her breasts if she is breastfeeding (Polomeno, 1999b). Being afraid of what they will find, some women are unable to explore their external genitalia after having given birth (Kitzinger, 1981). Some couples experience a period of great passion in the early postpartum due to the joy and excitement of their child's birth. This may be followed by a period of abstention, permitting time for the new mother to recover physically from the birth and a chance for the couple to integrate the baby into their lives (Bing & Colman, 1977). These couples continue lovemaking, but it's sex without intercourse (Kitzinger, 1981). The man may put his penis between the woman's thighs and oscillate with passion. Though a woman may have had an episiotomy and still have lochia, she may continue to receive clitoral stimulation and pleasure.

The Art of the Quickie (Gray, 1995, 1998b)—Sometimes a man would like to skip all of the foreplay and just experience sexual intercourse for the sheer pleasure of it. This is commonly known as the quickie. The partners should integrate the quickie into their repertoire along with other types of sexual encounters. Well-communicated, guilt-free quickies are great to experience for both partners. Dr. Judith Steinhart is quoted by Greiner (1995): “One of the most useful phrases that I've found in sex counseling is ‘No honey, I don't feel like X but I'd be happy to Y' ” (p. 119).

Expanding A Couple's Repertoire—In The Ultimate Sex Book: A Therapist's Guide to Sexual Fulfillment, Hooper (1992) describes many specific techniques for couples who wish to expand their repertoire of sexual activity. These include sexual fantasies, which start with suggestion and anticipation and then build up to excitement. Hooper also describes tantric lovemaking, which is based on a philosophy that the sexual experience can be expanded and, thereby, enhance a person's being. Tantra is the science of ecstasy and of delayed and prolonged lovemaking. Kama sutra was developed for the royal family of India and is noteworthy for its various sexual positions. Couples can read about it or learn through videocassettes. A woman may experience deeper orgasms through this type of lovemaking.

Implications for Childbirth Educators

The results of this study indicate that pregnant couples have many concerns regarding their sexual adjustment once their baby has arrived. Many perinatal educators feel uncomfortable discussing sexuality in their classes, and others have not given the subject sufficient time. Studies are just starting to emerge on sexual practices during pregnancy and the year postpartum (Hyde, DeLamater, Plant & Byrd, 1996). Their emergence coincides with new wave sexuality for the next century, in which there will be more open discussion about erotic matters and women will insist on sexual equality, even during pregnancy, birthing, and the postpartum.

“Sexuality is a basic component in the lives of all individuals and should not be ignored during the childbearing period” (Alteneder & Hartzell, 1997, p. 658). Perinatal educators may find useful Alteneder and Hartzell's PLISSIT model, a framework for developing interventions regarding sexuality changes during pregnancy and the postpartum period. The PLISSIT model was originally developed by Jack Annon in 1976 to direct health care providers in their interventions with clients facing sexuality issues. The letters represent permission (P), limited information (LI), specific suggestions (SS), and intensive therapy (IT). Perinatal educators with appropriate advanced-practice knowledge and professional competence can apply the first three levels of the model.

At the permission level, the topic of sexuality is introduced, and questions and assessment of behaviors are pursued. At the limited information level, facts about physiologic pregnancy and postpartum processes, as well as life and relationship issues, are discussed. At the level of specific suggestions, strategies are provided to change or add behaviors regarding sexual concerns and problems. At the last level, intensive therapy and referrals to trained sex therapists will likely be required (Alteneder & Hartzell, 1997). Some perinatal educators are trained sex therapists, so they would be able to intervene at the fourth level.

At the specific suggestion or third level, a childbirth educator could, for example, introduce the following information on perineal massage techniques, with accompanying handouts. This information comes from Dumolin (1995), a Montréal physiotherapist specializing in perineal re-education. She describes two types of perineal massage. In the first, the longitudinal perineal massage is conducted after a bath or a shower 4 to 6 weeks after the birth. Vitamin E cream is applied to the area between the vagina and the anus. Two fingers, placed on one side of the episiotomy scar, are slowly rotated in small circles up and down the scar. They are then transferred to the other side where the same technique is continued. This is done once a day for 2 to 3 minutes. The massage should be continued for 2 weeks or until the tissue has softened.

The second perineal massage is similar except that one finger is placed inside the vagina and the other on the outside (usually using the thumb and the index). The scar is grasped between the two fingers and slowly pinched and rolled between them. The pinching and rolling movements should be done in a circular fashion. Dumolin (1995) also encourages women to begin squatting 3 weeks after the birth of the baby. The squatting exercise should accompany the perineal massage. Initially, squatting is performed with the knees held close to each other. With time, however, the squatting position is deepened while the knees are held apart. This exercise should be performed for 5 minutes twice a day over a period of 2 weeks.

Childbirth educators who are ready to address the topic of postnatal sexual concerns in more detail can do so in their childbirth classes by offering separate intimacy workshops such as the ones described in the study above. An alternative would be to find a professional colleague who will conduct the workshops and refer couples from your classes. In any event, the sexual adjustments that will be necessary after experiencing pregnancy and birth are important to sustaining families. Thus, a plan to address these issues is important to the overall goals of childbirth education.

The G-spot The G-spot is said to be a localized area of especially high sensitivity situated on the front wall of the vagina. Illustration taken from The Ultimate Sex Book, copyright Dorling Kindersley.

References

- Alteneder R, Hartzell D. Addressing couples' sexuality concerns during the childbearing period: Use of the PLISSIT model. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 1997;26(6):651–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1997.tb02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzate H, Hoch Z. The “G-spot” and “female ejaculation”: A current appraisal. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 1986;12(3):211–220. doi: 10.1080/00926238608415407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annon J. S. 1976. The behavioral treatment of sexual problems. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Bing E, Colman L. 1977. Making love during pregnancy. New York: Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield H, Vettese S. 1989. Lifemates. New York: New American Library. [Google Scholar]

- Boston Women's Health Book Collective. 1992. The new our bodies, ourselves. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy B. Seven secrets for a lifetime of love. Men are from Mars & women are from Venus: Preview Issue. 1998 Feb.-Mar.: 40-43. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan P. Individual and family life transitions: A proposal for a new definition. 1991. In P. A. Cowan and M. Hetherington (Eds.), Family transitions (pp. 3-30). Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Darling C. A, Davidson J. K, Conway-Welch C. Female ejaculation: Perceived origins, the Grafenberg spot/area, and sexual responsiveness. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1990;19(1):29–47. doi: 10.1007/BF01541824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumolin C. 1995. Programme d'exercices post-natales: Accouchement naturel. Montréal: Hôpital Ste.-Justine. [Google Scholar]

- Ganem M. 1992. La sexualité du couple pendant la grossesse. Paris: Editions Filipacchi. [Google Scholar]

- Grafenberg E. The role of urethra in female orgasm. International Journal of Sexology. 1950;3:147.. [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. 365 days of love. 1998a. Men are from Mars & women are from Venus: Preview Issue Feb.-Mar.: 19-21.

- Gray J. The art of the quickie. 1998b. Men are from Mars & women are from Venus: Preview Issue Feb.-Mar.: 28-31.

- Gray J. Scoring points. 1998c. Men are from Mars & women are from Venus: Preview Issue Feb.-Mar.: 44-47.

- Gray J. 1995. Mars and Venus in the bedroom: A guide to lasting romance and passion. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner G. Sex and the pregnant woman. Fit Pregnancy. 1995:118–119. Winter, 69-70, [Google Scholar]

- Henry J. The pure pleasures of partner massage. Fit Pregnancy. 1996;Summer:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper A. 1992. The ultimate sex book: A therapist's guide to sexual fulfillment. New York: Dorling Kindersley, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde J, DeLamater J, Plant E, Byrd J. Sexuality during pregnancy and the year postpartum. The Journal of Sex Research. 1996;33(2):143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger S. Emotional aspects of episiotomy and postnatal sexual adjustment. 1981. In S. Kitzinger (Ed.), Episiotomy: Physical and emotional aspects (pp. 45-52). London: National Childbirth Trust.

- Luscher M. 1996. The colors of love. New York: St. Martin's Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polomeno V. (1999a). Personal reflections: Are perinatal educators preparing couples for the transition to parenthood? Journal of Perinatal Education (submitted for publication). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Polomeno V. Sex and breastfeeding: An educational perspective. Journal of Perinatal Education. 1999b;8(1):30–41. doi: 10.1624/105812499X86962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polomeno V. Family health promotion from the couple's perspective. 1999c. Part I. International Journalof Childbirth Education,14(1), 8-12.

- Polomeno V. Sexual intercourse after the birth of a baby. International Journal of Childbirth Education. 1995;10(4):):35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin B. Parents' guide to romance. 1998. Men are from Mars & women are from Venus: Preview Issue Feb.-Mar.: 22-26.

- Reeder S. J, Martin L. L, Koniak-Griffin D. 1997. Maternity nursing: Family, newborn, and women's health care. Philadelphia: Lippincott. [Google Scholar]

- Yorke A. 1988. The art of erotic massage. London: Javelin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Zaviacic M, Whipple B. Update of the female prostate and the phenomenon of female ejaculation. The Journal of Sex Research. 1993;29.:149.. [Google Scholar]